Prewriting and Handwriting Skills

1 Describe the role of the occupational therapist in the evaluation and intervention of children with handwriting difficulties.

2 Identify the factors contributing to handwriting readiness for young children.

3 Examine four aspects of functional written communication: the writing tasks in the classroom, legibility, speed, and ergonomic factors.

4 Discuss the performance skills, client factors, performance patterns, and context that influence the student’s participation in the writing process.

5 Describe how handwriting fits into the educational writing process.

6 Develop remedial and compensatory strategies to improve a student’s performance of written communication, focusing on the actual occupation and the occupational context.

7 Examine the relationship of various pediatric occupational therapy models of practice and handwriting intervention programs.

8 Appreciate the need for gaining more evidence about the effects of occupational therapy intervention on children’s handwriting.

Occupational therapy practitioners view the occupations of children to be activities of daily living, education, work, play, and social participation. In the area of education, school-aged children’s occupations encompass academic skills such as literacy (including reading and writing), calculation, and problem-solving, as well as nonacademic or functional tasks. Functional tasks may include navigating around classroom furniture and classmates, sharing school supplies with a peer, placing a notebook into a locker, constructing a papier-mâché planet, cutting with scissors, and writing words on paper—all of which support a student’s academic performance in the classroom. These academic skills and functional tasks are expected to evolve and strengthen throughout a student’s school years.73

Handwriting is a critical skill for elementary-aged students to acquire. Writing is a tool for communication; it provides a means to project thoughts, feelings, and ideas.27 Writing is required when children and adolescents compose stories, complete written examinations, copy numbers for calculations, and write messages to friends and family members. Although computers allow students to type letters and reports, society continues to rely on handwriting to complete forms, write personal notes and messages, and maintain records. Handwriting is more than a motor skill; it requires connecting the letter name with a letterform and recalling a clear visual picture of the letterform from memory, as well as being able to execute the motor pattern required to produce the form.37 Writing is a complex process requiring the synthesis and integration of memory retrieval, organization, problem solving, language and reading ability, ideation, and graphomotor function.27 The functional skill of handwriting supports the academic task of writing and allows students to convey written information legibly and efficiently while accomplishing written school assignments in a timely manner.20,45

Handwriting consumes much of a student’s school day. McHale and Cermak examined the amount of time allocated to fine motor activities and the type of fine motor activities that school-aged children were expected to perform in the classroom.80 In their study of six classes consisting of two classrooms each from grades two, four, and six in middle-income public schools, they found that 31% to 60% of the children’s school day consisted of fine motor activities. Most of these fine motor activities (85%) were paper-and-pencil tasks, indicating that students may possibly spend up to one quarter to one half of their classroom time engaged in paper-and-pencil tasks.

When children are having difficulty with handwriting, problems with written assignments follow. Students with neurologic impairments, learning problems, attention deficits, and developmental disabilities often expend enormous time and effort learning to write legibly.6,17 Consequences of handwriting difficulties at school may include the following: (1) teachers may assign lower marks for the writing quality of papers and tests with poorer legibility but not poorer content,26,28,48,100 (2) students’ slow handwriting speed may limit compositional fluency and quality,46,64,111 (3) students may take longer to finish assignments than their peers,44 (4) students may have problems with taking notes in class and reading them later,44 (5) students may fail to learn other higher-order writing processes such as planning and grammar, and (6) writing avoidance may develop, contributing later to arrested writing development.19

Berninger et al. explain that it is critical for children to learn to write automatically to accomplish the extensive written composition required of them in later elementary grades.21 Handwriting instruction is important to ensure that children learn the “building blocks of written discourse automatically so that they can focus on other important aspects of writing, such as choosing and spelling words, constructing sentences, and organizing the discourse of composing written texts” (p. 4).21

Teachers often request that occupational therapists evaluate a student’s handwriting when it interferes with performance of written assignments. In fact, poor handwriting is one of the most common reasons for referring school-aged children to occupational therapy.25,85,92 Of school occupational therapy referrals, 80% to 85% are for fine motor and handwriting concerns that affect educational performance.

The role of the occupational therapist is to view the student’s performance, in this case handwriting, by focusing on the interaction of the student, the school environment, and the demands of school occupations.3,95 During the evaluation and intervention processes, the practitioner stays focused on (1) the occupation of handwriting, determining which domains of handwriting (e.g., near-point copying or dictation) and which components (e.g., spacing or letter formation) are problematic for the student; (2) the school context (e.g., the curriculum or physical classroom arrangement related to the child’s performance; (3) the student’s personal context (e.g., cultural, temporal, spiritual, and physical aspects); and (4) student experiences that are interfering with handwriting production.

THE WRITING PROCESS

The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001(NCLB) increased the emphasis on literacy and the contributions of school professionals to developing literacy skills in children. Literacy begins with the basic ability to read and write (functional literacy), which is required in everyday life, and proceeds to advanced literacy, which includes reflecting on knowledge of significant ideas, events, and values of a society.57

Preliteracy Writing Development of Young Children

Handwriting is a complex skill that develops over years of practice. Many children begin to draw and scribble on paper shortly after they are able to grasp a writing tool. As young children mature, they write intentionally meaningful messages, first with pictures and then with scribbles, letter-like forms, and strings of letters.79 The development of a child’s writing process in the early elementary grades includes not only mastering the mechanical and perceptual processes of graphics but also the acquisition of language and the learning of spelling and phonology.104 Typically, children’s writing and reading skills develop in parallel processes with one another.79 Consequently, if a young child is unable to recognize letterforms and understand that these letterforms represent written language, occupational therapists and educators cannot expect the child to write.

As children develop, their scribbling and pictures evolve into the handwriting (i.e., language symbols) specific to their culture. Tan-Lin examined the sequential stages of letter acquisition of 110 children between the ages of 3 and 5 years.103 Children were observed copying numbers, letters, a few words, and a sentence on three separate occasions over a period of 4 months. She found that the children progressed through the following sequential stages of prewriting and handwriting: (1) controlled scribbles; (2) discrete lines, dots, or symbols; (3) straight-line or circular uppercase letters; (4) uppercase letters; and (5) lowercase letters, numerals, and words. Table 19-1 details the development of prewriting and handwriting in children in the United States. Age levels of handwriting progression listed are only approximations, because variation in skill development is to be expected among young children.

TABLE 19-1

Development of Prewriting and Handwriting in Young Children

| Performance Task | Age Level |

| Scribbles on paper | 10–12 mo |

| Imitates horizontal, vertical, and circular marks on paper | 2 yr |

| Copies a vertical line, horizontal line, and circle | 3 yr |

| Copies a cross, right oblique line, square, left diagonal line, left oblique cross, some letters and numerals, and may be able to write own name | 4–5 yr |

| Copies a triangle, prints own name, copies most lowercase and uppercase letters | 5–6 yr |

Bayley, N. (2005). Bayley scales on infant development (rev. ed.). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; Beery, K. E., & Beery, N. (2005). The Development Test of Visual-Motor Integration. Cleveland: Modern Curriculum Press; Tan-Lin, A. S. (1981). An investigation into the developmental course of preschool/kindergarten aged children’s handwriting behavior. Dissertation Abstracts International, 42, 4287A; Weil, M., & Amundson, S. J. (1994). Relationship between visual motor and handwriting skills of children in kindergarten. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48, 982–988.

Writing Development of School-Aged Children

Most children learn to write letters in kindergarten, but do not develop fluency until the third or fourth grade, and they do not demonstrate adult speed in writing until the ninth grade.46 Handwriting requires the integration of both lower-level perceptual–motor processes and higher-level cognitive processes.50 Correlational studies have found that handwriting skill is strongly linked to eye–hand coordination4,24,109 and is moderately associated with dexterity.29 A number of correlational studies found that visual-motor integration is the strongest predictor of handwriting legibility.110,115 The perceptual-motor processes of handwriting includes visual perception (e.g. when copying from a model), auditory processing (e.g., when words are dictated), and visual motor integration (e.g. when combining the components to write). The cognitive processes involved include executive planning and use of working memory. Handwriting also requires specific language processes,111 including the ability to hear a word and identify what letters form that word (i.e., turning spoken language into written language).

When young children first learn to write their letters, they use their vision to guide their hand movements. Although adults rely more on kinesthetic input when writing,15 children learn the skills by visually analyzing form and space, then linking the image of a letterform to a motor plan. With practice in visually guiding their hand movement, children develop a kinesthetic memory of letterforms. At this point in their learning, writing becomes automatic and minimal cortical processing is required to form letters.7,15 In primary grades, when students are learning handwriting by copying letters, visual–motor coordination and motor dexterity are critical skills.111 In older students, who are required to produce substantial amounts of writing, cognitive processes become more important (e.g., planning and linguistic skills). The association between lower level (perceptual–motor) handwriting skills and higher-level (memory and cognition) skills was documented by Graham, who found that difficulties with handwriting can interfere with the execution of the composing processes.43

Graham et al. found that handwriting fluency is a predictor of compositional fluency and quality.45 Once a student has achieved automatic writing, he or she can focus on other aspects of writing (e.g., spelling, grammar, planning, organizing information for writing tasks) and therefore improve composition quality. Because handwriting requires perceptual–motor processes and cognitive processes, students with illegible handwriting may have deficits in either area.

Handwriting Readiness

Some controversy exists as to when children are ready for formal handwriting instruction. Differing rates of maturity, environmental experiences, and interest levels are all factors that can influence children’s early attempts and success in copying letters. Some children may exhibit handwriting readiness at 4 years of age, whereas others may not be ready until they are 6 years old.68,71 A number of authors4,34,68,118 have stressed the importance of the mastery of handwriting readiness skills before handwriting instruction is initiated. These authors contend that children who are taught handwriting before they are ready may become discouraged and develop poor writing habits that may be difficult to correct later.

Donaghue34 and Lamme68 identified six prerequisite skills of children necessary before handwriting instruction begins. These are (1) small muscle development; (2) eye–hand coordination; (3) the ability to hold utensils or writing tools; (4) the ability to form basic strokes smoothly, such as circles and lines; (5) letter perception, including the ability to recognize forms, notice likenesses and differences, infer the movements necessary for the production of form, and give accurate verbal descriptions of what was seen; and (6) orientation to printed language, which involves right–left discrimination and visual analysis to determine when a group of letters forms a word.

The readiness factors needed for handwriting require the integrity of a number of sensorimotor systems. Letter formation requires the integration of the visual, motor, sensory, and perceptual systems. Performance components associated with handwriting include kinesthesia, motor planning, eye–hand coordination, visual–motor integration, and in-hand manipulation. Kinesthesia provides the ongoing error information and references for subsequent repetitions.71 In addition, it provides information about directionality during letter formation. Good kinesthetic information enhances speed, reduces the need to visually monitor the hand during writing, and influences the amount of pressure applied to the writing implement. Sufficient fine motor coordination is also needed to form letters accurately.4

Benbow described six developmental classifications that underlie skilled use of the hands that contribute to greater adeptness in operating a pencil: (1) upper extremity support, (2) wrist and hand development, (3) visual control, (4) bilateral integration, (5) spatial analysis, and (6) kinesthesia.15 Other authors define readiness for handwriting on the basis of a child’s ability to copy geometric forms. Beery13 and Benbow, Hanft, and Marsh16 suggested that instruction in handwriting be postponed until after the child is able to master the first nine figures in the Developmental Test of Visual–Motor Integration (VMI).13 The nine figures are a vertical line, a horizontal line, a circle, a cross, a right oblique line, a square, a left oblique line, an oblique cross, and a triangle.

A study by Weil and Amundson examined 59 kindergarten children who were developing typically (ages 54 to 64 months) and assessed their abilities to copy letterforms as well as the geometric designs on the VMI.113 The findings indicated that children who were able to copy the first nine forms of the VMI correctly copied significantly more letters than those who were not able to copy the first nine forms, thus providing support for the opinions of Beery13 and Benbow et al.16 Weil and Amundson also found that kindergarten children, on average, correctly copied 78% of the letters presented, despite not having received formal handwriting instruction.113 Based on these results, the authors concluded that most typically developing kindergarten children should be ready for actual handwriting instruction in the latter half of the kindergarten school year.

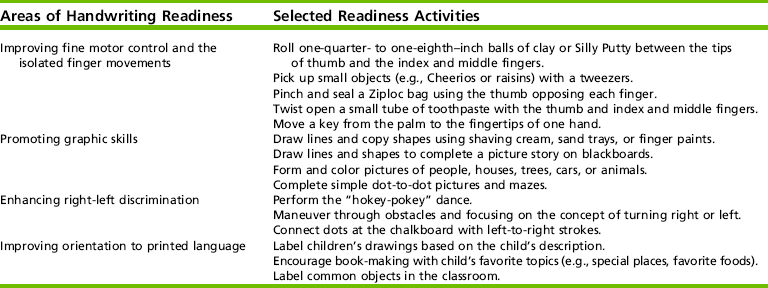

To develop children’s handwriting readiness skills, the occupational therapy practitioner may incorporate activities into therapy sessions or the classroom. Selected activities should be aimed at improving fine motor control and isolated finger movements, promoting prewriting skills, enhancing right–left discrimination, and improving orientation to printed language.12,15,16,68,84,118

Some children with significant cognitive or physical impairments may not acquire many of the prerequisite components needed for writing, and they are most successful in written communication using a computer with word processing and word prediction software programs. Other children, despite lacking the prerequisite components for handwriting, may be able to learn to write their name with practice. The occupational therapy practitioner must determine when it is appropriate for the young child to work on prerequisite handwriting skills, the functional skill of handwriting, or both. Activities commonly used with young children to facilitate certain movements, experiences, and perception for handwriting development are listed in Table 19-2. Movements and tasks to encourage handwriting development should be used in the context of what is meaningful and purposeful to the child.

Pencil Grip Progression

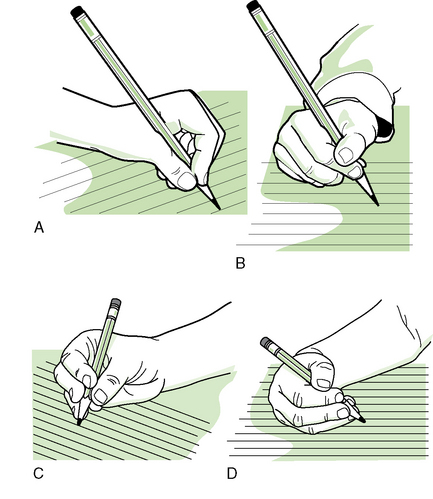

The development of pencil grip in young children follows a predictable course for typically developing children but may vary among cultures.107 Children commonly begin by holding the pencil with a primitive grip—characterized by holding the writing tool with the whole hand or extended fingers, pronating the forearm, and using the shoulder to move the pencil. Later, a transitional pencil grip is seen with the pencil being held with flexed fingers. Initially, the forearm is pronated (thumb side downward); later, the forearm is usually supinated. In the mature pencil grip, the pencil is stabilized by the distal phalanges of the thumb and index, middle, and possibly ring fingers, the wrist is slightly extended yet dynamic, and the supinated forearm rests on the table.38,94,98,107

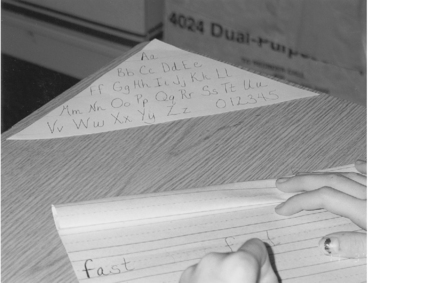

Traditionally, teachers and occupational therapy practitioners have stressed the importance of a dynamic tripod pencil grasp.94,109 In this grip the writing utensil rests against the distal phalanx of the radial side of the middle finger while the pads of the thumb and index finger control it (Figure 19-1).94 Recent studies18,31,67,97,98,107,120 have found that a variety of pencil grasp patterns exist among typical adults and children. Frequently observed mature pencil grips, besides the dynamic tripod grasp, include the lateral tripod, the dynamic quadrupod, and the lateral quadrupod. Schneck and Henderson reported in their study of 320 typically developing children that by the age of 6.5 to 7 years, 95% had adopted a mature pencil grasp, either the dynamic tripod (72.5%) or the lateral tripod (22.5%).98 Outside of the United States, Tseng noted that the lateral tripod grip (42.9%) occurred almost as frequently as the dynamic tripod (44.1%) for typically developing Taiwanese children 5.5 to 6.4 years of age.107

FIGURE 19-1 Mature pencil grips in elementary school children. A, Dynamic tripod; B, lateral tripod; C, dynamic quadrupod; and D, lateral quadrupod.

In older elementary children, the dynamic quadrupod and lateral quadrupod grips have been identified as functional and mature pencil grasps.31,67 Thus, the lateral tripod, the dynamic quadrupod, and the lateral quadrupod grips may all be considered acceptable alternatives to the traditionally preferred dynamic tripod grip (see Figure 19-1).

HANDWRITING EVALUATION

When a child with poor handwriting has been referred to occupational therapy, the methods to gather evaluation information must be carefully selected and sequenced. An individual evaluation is needed because each child with handwriting dysfunction varies from every other child with handwriting problems. A comprehensive evaluation of a child’s handwriting includes: (1) the occupational profile; and (2) the analysis of occupational performance.

Initially, the student’s performance in the context of classroom standards should be the focus (before moving toward standardized testing). Assembling data and information from various sources gives the occupational therapist an integrated picture of the child’s written communication. It also allows the therapist to examine the child’s ability to perform other functional school tasks, such as handling school supplies and tools, managing outdoor clothing and fasteners, and organizing school materials. Although poor handwriting is a common referring concern in the classroom, poor performance of other school tasks may have gone unnoticed and should also receive attention from the occupational therapist and educational team.

Occupational Profile

The Occupational Profile describes the student’s occupational therapy history, experiences, patterns of daily living, interests, values, and needs. It is designed to gain an understanding of the client’s perspective and background.82 The information for the occupational profile can be gathered by interviewing the child, parent(s), teacher, and other team members. Interviewing the child’s parents, educator, and other team members also serves as a mechanism for building rapport.

Interviews

Interviewing the child helps the therapist to understand what is important and meaningful to the child. This information helps the therapist gain an understanding of the child’s perspective and background. Because teachers observe their students’ daily performance in class, they can share information about the student’s abilities and achievements and how the student responds to instruction. A sampling of questions to facilitate discussion between the teacher and the occupational therapist is listed in Box 19-1. The educator provides a background picture of the student’s capabilities, behavior, and struggles at school.

Cornhill and Case-Smith found that students with poor handwriting, as identified by teacher reports, scored significantly lower on three assessments of sensory motor performance components (eye–hand coordination, visual–motor integration, and in-hand manipulation) than students with good handwriting.29 In addition, the authors found that scores on assessments of these performance skills could be used to predict scores in the handwriting performance. Teachers report that they evaluate students’ handwriting by comparing it with that of classroom peers (37%) or comparing it with student handwriting in a book (35%).52

Parents are also a valuable resource for occupational therapists; they provide a different perspective on the child and the child’s handwriting abilities. Not only can parents relate the child’s developmental, medical, and familial background to the educational team, but they can share invaluable information about the child’s interests, social competence, and attitudes toward learning and school.

Parents are considered educational team members, and they provide important perspectives that give the occupational therapist a comprehensive view of the child at home and at school. To facilitate discussion about the child and his or her writing, parents might be asked questions such as the following: (1) Do parents expect the child to complete school assignments or written work at home? (2) What is the child’s response to written homework? (3) How does the child perform his or her written assignments at home and at school? (4) What other writing tasks are expected of the child at home (e.g., corresponding with relatives, recording telephone messages)?

Analysis of Occupational Performance

A comprehensive evaluation of a child’s handwriting includes (1) examining written work samples; (2) further discussing the child’s performance with the teacher, parent, and other team members; (3) reviewing the child’s educational and clinical records; (4) directly observing the child when he or she is writing in the natural setting (i.e., school, home); (5) evaluating the child’s actual performance of handwriting; and (6) assessing any performance skills suspected to be interfering with handwriting.

Work Samples

As part of the evaluation process, the occupational therapist accesses the child’s handwritten class work or homework. Written work samples may include spelling lessons, mathematical problems, or a story. Ideally, these samples should represent a typical handwriting performance of the child. When reviewing the child’s written product, a comparison of the writing samples of the child’s peers is also warranted to clarify the classroom standards and teacher expectations. Informal evaluation of the work samples for alignment, size, letter formation, legibility, and slant may indicate the need for further evaluation.

File Review

Relevant information regarding past academic performance, special testing, or receipt of special services can be found in the referred child’s educational cumulative file. Medical or clinical reports related to the child’s education may also be located in the child’s regular or special education files. The child’s parents may share academic records and reports with clinic- and hospital-based occupational therapists. This documentation may trigger further conversations among the child’s parents and team members.

Direct Observation

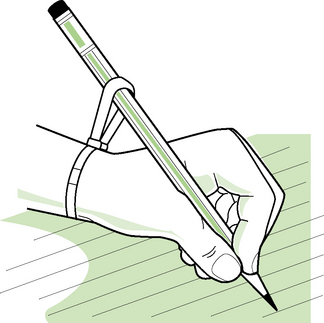

Observing the student during a writing activity in the classroom is an essential step in the evaluation process (Figure 19-2). Skilled observation by the examiner usually occurs in the child’s classroom and focuses on task performance, attention to task, problem solving, and behavior of the child.55 Practitioners also note the student’s organizational abilities, movement through the classroom, interactions with the teacher and peers, transitions between activities, and overall performance of other school tasks. School contextual features (e.g., the classroom arrangement, lighting, noise level, instructional media), as well as the actual instruction from school personnel, should all be considered in relationship to the student’s performance. In addition to a structured protocol for direct observation, the occupational therapist may ask the following:

1. Which writing tasks (for example, copying sentences from the chalkboard or composing a story) are most problematic for the child?

2. What behaviors are manifested when the child is required to write? For example, does the child chew on the eraser of the pencil or blow the pencil across the desktop to avoid writing?

3. Can the child engage independently in the task of writing, or does she or he need physical and verbal cues from the teacher or educational assistant?

4. Is the child easily distracted by visual and auditory stimuli during writing, such as a delivery truck driving by the school window?

5. Where does the child sit in the classroom?

6. What curriculum is being followed?

7. Where is the teacher located when he or she gives assignment directions?

8. How does the observed difficulty interfere with the child’s learning?

MEASURING HANDWRITING PERFORMANCE

In evaluating the actual task of children’s handwriting, the following areas need to be examined: (1) domains of handwriting, (2) legibility components, (3) writing speed, and (4) ergonomic factors. Whether the student writes in manuscript (print), cursive (joined script), or both, these four aspects will help the educational team and parents uncover problematic areas of handwriting and establish a baseline of handwriting function. With accurate and relevant handwriting assessment data, the occupational therapist, the child’s parents, and the educational or clinical team will also be able to target specific goals and objectives for the development of written communication.

Domains of Handwriting

Evaluating the various domains of handwriting allows the occupational therapist to determine which tasks the child may be having difficulty with and address those tasks in the intervention plan. Handwriting tasks demanded of students, and helpful for intervention planning, include the following:

• Writing the alphabet in both uppercase and lowercase letters along with numbers requires the child to remember the motor engram, form each individual letter and numeral, sequence letters and numbers, and use consistent letter cases.

• Copying is the capacity to reproduce numerals, letters, and words from a similar script model, either manuscript to manuscript or cursive to cursive.

• Near-point copying is producing letters or words from a nearby model, commonly on the same page or on the same horizontal writing surface, as when an elementary pupil copies the meaning of a word from a nearby dictionary.

• Copying from a distant vertical display model to the writing surface is termed far-point copying, demonstrated by early elementary students writing the words “Happy Valentine’s Day” on construction paper cards from the teacher’s modeled words on the class chalkboard.

• More advanced than copying, manuscript-to-cursive transition requires a mastery of letterforms in both manuscript and cursive as the child must transcribe manuscript letters and words to cursive letters and words.

• Writing dictated words, names, addresses, and telephone numbers is a skill children will need at school and at home. A higher-level handwriting task combining integration of auditory directions and a motoric response is dictation.

• Composition is the generation of a sentence or paragraph by the child demonstrated by writing a poem, a story, or a note to a friend. The composing process uses the cognitive functions of planning, sentence generation, and revision56; thus, this writing task involves complex integration of linguistic, cognitive, organizational, and sensorimotor skills.

Legibility

Legibility is often assessed in terms of its components—letter formation, alignment, spacing, size, and slant.1,7,47,60,120 However, the bottom line of legibility is readability. Of primary importance is whether what was written by the child can be read by the child, parent, or teacher. In a handwriting evaluation, the components of both legibility and readability need to be assessed.

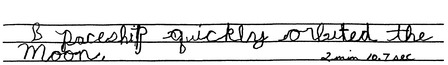

The influence of legibility components on readability is significant.47,61 In letter formation, Alston identified five features affecting legibility: (1) improper letterforms, (2) poor leading in and leading out of letters, (3) inadequate rounding of letters, (4) incomplete closures of letters, and (5) incorrect letter ascenders and descenders.1 Alignment, or baseline orientation, refers to the placement of text on and within the writing guidelines. Spacing includes the dispersion of letters within words and words within sentences70 and text organization on the entire sheet of paper. Another component of legibility, size, refers to the letter relative to the writing guidelines and to the other letters. Finally, the uniformity or consistency of the slant or the angle of the text should be observed. Figure 19-3 illustrates errors of letter formation and size in a child’s cursive writing.

FIGURE 19-3 Cursive handwriting sample exemplifies improper letterforms and disproportionate letter size.

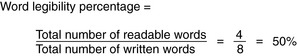

Although a child’s writing sample may still be readable even though a legibility component (e.g., poor sizing) interferes with its appearance, some legibility components have a stronger impact on readability than others. Graham et al. found that the letter formation, spacing, and neatness of 61 fourth-grade students with learning disabilities all significantly correlated with legibility.47 Typically, legibility is determined by counting the number of readable written letters or words and dividing it by the total number of written letters or words in a writing sample. Figure 19-4 provides the formula to determine word legibility percentage. As reflected in the figure, eight words were written in the child’s writing sample; however, only four of them were legible, resulting in 50% word legibility.

Frequently, occupational therapy practitioners and educators want to determine what legibility percentage is appropriate for students at specific grade levels. Likewise, occupational therapists are interested in the “cut-off” legibility percentages for poor and good handwriting. The validity of readability and legibility percentages has been reported in three studies with small samples.

The first study conducted by Talbert-Johnson, Salva, Sweeney, and Cooper asked 15 upper elementary, middle school, and high school students with special needs to copy a short passage in cursive writing.102 Through a sorting process, easy-to-read handwriting samples scored between 95% and 100% letter legibility, with a mean of 99%. Conversely, difficult-to-read handwriting measured at 60% to 90% letter legibility, with a mean of 78%. In the second study, Reisman found that 51 second grade students receiving handwriting intervention in occupational therapy averaged a 76% legibility rate on a pilot version of the Minnesota Handwriting Test.92 In a third example, Graham, Berninger, Weintraub, and Shafer, in their study of 900 children who were developing typically in grades one through nine, found that handwriting legibility showed little improvement in the first four elementary grades.46 Legibility gains were made in the upper elementary grades and maintained through junior high school.

Koziatek and Powell investigated four writing tasks from the Evaluation Tool of Children’s Handwriting-Cursive (ETCH-C) with 101 fourth-grade students.66 They found that the ETCH-C letter and word legibility scores were able to classify and predict children’s handwriting grades on report cards. The 75% word legibility level of the ETCH-C could discriminate between satisfactory (C or better grades) and unsatisfactory cursive handwriting.

Although each of the aforementioned studies examining legibility rates used different measures, implications for occupational therapy practice suggest that the range of 75% to 78% appears to discriminate between satisfactory and unsatisfactory handwriting legibility. This range of legibility percentages, however, is not the benchmark for which children warrant occupational therapy services. A student’s handwriting may be at the 75% legibility level and still be unreadable. With recommended compensatory strategies from the occupational therapy practitioner, this same child might boost his or her handwriting to a readable level. Thus, no ongoing occupational therapy services may be needed. Determining appropriate educational and therapeutic services for children involves an entire team, including the child’s parents, and, of course, should never depend solely on test scores. Thus, the occupational therapist must carefully and comprehensively assess the nature of the child’s poor handwriting and give recommendations based on this process.

Writing Speed

A child’s rate of writing, or the number of letters written per minute, and its legibility are the two cornerstones of functional handwriting.7 Students may take longer to complete written assignments, have difficulty taking notes in class,44 lose their train of ideas for writing,78 and become frustrated when their handwriting speed is slower than that of their peers. Writing speed typically decreases when the amount of written work or complexity of the writing task increases.95,114 Upper elementary and older students need not only an adequate writing speed but also the ability to adjust their speed from a hurried, rough draft to a neat, well-paced final one.114

Differences in methodologies, subjects, and data collection in relevant studies have resulted in a varied baseline of writing speeds for typically developing children.108,120 These studies show that children’s handwriting speeds develop gradually, becoming faster in each succeeding grade.46,53,90,91,120,121 However, the studies’ findings also suggest that the increase in speed may not be linear but marked by various spurts and plateaus. Handwriting speed per grade level has been found to be highly variable when different study designs and writing conditions are used.

Because of the wide range of handwriting speeds, children’s writing rates need to be considered individually within the context of their classroom. Teacher expectations and classroom standards may influence children’s writing speeds. Thus, it is appropriate to compare a student’s writing speed performance with the rates of classroom peers. In general, handwriting speed is problematic when a student is unable to complete written school assignments in a timely manner. When a student’s written expression abilities (e.g., language, spelling) exceed handwriting rate, alternative forms (e.g., keyboarding, word prediction programs) should be considered.

Ergonomic Factors

Writing posture, upper extremity stability and mobility, and pencil grip are ergonomic factors that must be analyzed as the child writes. Sitting posture in the classroom should be observed. Does the child rest his or her head on the forearm or desktop when writing? Is the child falling out of or slumping in his or her chair? Does the child stand beside the desk or kneel in the chair? Are the desktop and the chair at suitable heights?

Stability and mobility of the upper extremities (i.e., the ability to keep the shoulder girdle, elbow, and wrist stable) allow the dexterous hand to manipulate the writing instrument. Does the child write with whole-arm movements? What are the positions of the trunk and writing arm? Does the non-preferred hand stabilize the paper? Does the child apply excessive pressure to the writing tool?

An ergonomic focus for most occupational therapy practitioners is whether a child is holding the pencil properly, or using an atypical pencil grasp. Ziviani reported that different grasp variations are expected.119 Poor writers tend to demonstrate a greater variety of atypical grasp patterns than legible writers. Mature pencil grips for children now include the dynamic tripod, the lateral tripod, the dynamic quadrupod, and the lateral quadrupod.31,67,98,107 Unconventional pencil grips do not necessarily affect the speed or the legibility of the child’s handwriting.31,109

HANDWRITING ASSESSMENTS

Formal or standardized tests are important for assessing the performance of children, as they provide objective measures and quantitative scores, aid in monitoring a child’s progress, help professionals communicate more clearly, and advance the field through research. Numerous standardized handwriting instruments are available commercially. Assessment tools commonly used by occupational therapists in the United States include the Children’s Handwriting Evaluation Scale,91 the Children’s Handwriting Evaluation Scale—Manuscript,90 the Denver Handwriting Analysis,9 the Minnesota Handwriting Test,93 the Evaluation Tool of Children’s Handwriting,7 the Test of Handwriting Skills,42 and The Print Tool.86

Each of these assessment tools possesses various features regarding domains of handwriting tested (e.g., far-point copying, dictation), age or grade of child (e.g., first and second grades), script examined (e.g., cursive), scoring procedures of the writing performance (e.g., legibility of manuscript), and scores obtained (e.g., percentiles). Typically, tests measure handwriting legibility and speed of handwriting. Scoring procedures for legibility use rating techniques ranging from global and subjective to detailed and specific.108 Appendix 19-A provides publication information regarding handwriting assessments available to occupational therapists.

For tool selection, the occupational therapist should keep in mind the characteristics of each assessment as well as the strengths and limitations of the tests regarding normative data, reliability, validity, and other psychometric properties (see Chapter 8). Critiques and lengthier descriptions of handwriting assessments by several authors6,30,92,108 should be reviewed in selecting the most appropriate test. A shortcoming of most handwriting instruments is the low reliability for measuring legibility owing to the subjective nature of judging handwriting legibility.33 The assessment chosen should match the areas of concern regarding the child’s handwriting and should allow for effective intervention planning among the occupational therapist, the child’s parents, and other team members.

Factors Restricting Handwriting Performance

To understand more fully which element may be interfering with a child’s ability to produce text, the occupational therapist must consider a child’s performance skills, client factors, performance patterns, and contextual elements.5 As occupational therapists build their clinical reasoning skills, they are able to observe a child struggling to write or view a child’s distorted, unreadable handwriting and identify factors that might be interfering with the child’s written communication. The example in Case Study 19-1 indicates how various factors may restrict a child’s handwriting performance. This example illustrates the complex interactions that occupational therapists must be able to analyze to determine what factors influence a child’s ability to engage in an occupation such as handwriting.

Like Natasha, children with poor handwriting typically have a web of factors that restrict their handwriting performance. The occupational therapist must unravel each factor from the others to understand its influence as well as its interaction with other performance factors. For example, Natasha’s client factors (i.e., short attention span, impulsiveness) and cultural context (i.e., English as a second language) interact with one another to restrict her handwriting performance. Natasha’s short attention span diminishes not only her ability to learn handwriting but also her ability to learn new concepts, including her second language, English. If she is unable to understand the language symbols, words, and syntax of the English language, she will have difficulty reading English. Furthermore, because reading and writing are parallel learning processes, Natasha’s handwriting will be impeded. Natasha’s handwriting is more likely to improve once effective compensatory and remedial techniques are in place to improve her attention span and her knowledge and use of the English language.

EDUCATOR’S PERSPECTIVE

State standards for written language and literacy, as well as the district curriculum, should be used to guide evaluation and intervention. When educators speak of the writing or composing process, they view it as a goal-directed activity using the cognitive functions of planning, sentence generation, and revision.56 The actual text production occurs in sentence generation; thus, the child who needs to pay considerable attention to the mechanical requirements of writing may interrupt higher order writing processes, such as planning or content generation. Hence, most educators view the mechanical requirements of handwriting as an integral subset of the writing process. Two factors that teachers indicated most frequently as important for handwriting to be acceptable were (1) correct letter formation and (2) directionality and proper spacing.52

Handwriting Instruction Methods and Curricula

During the past decade, an educational debate has focused on teaching handwriting systematically through commercially prepared or teacher-developed programs, or learning it through a “whole-language” approach. The whole-language philosophy purports that both the substance (meaning) of writing and the form (mechanics) of writing are critical for learning to write.44 Thus, when using the whole-language method as children are learning and mastering handwriting, the teacher gives advice and assigns practice on an individual, as-needed basis. For example, if an educator sees a first-grader struggling to form the letter m while writing a story about monsters, he or she may instruct the child regarding the correct letter formation of m and encourage extra practice of the letter during the story composition period. Conversely, in a traditional handwriting instruction approach, students are introduced to letter formations and practice them outside of the context of writing. For children with learning disabilities and mild neurologic impairments, regular practice in forming letters is essential in the early stages of handwriting development, yet handwriting should have a meaningful context. Thus, a combination of systematic handwriting instruction and whole-language methods may be most beneficial to this group of children.44

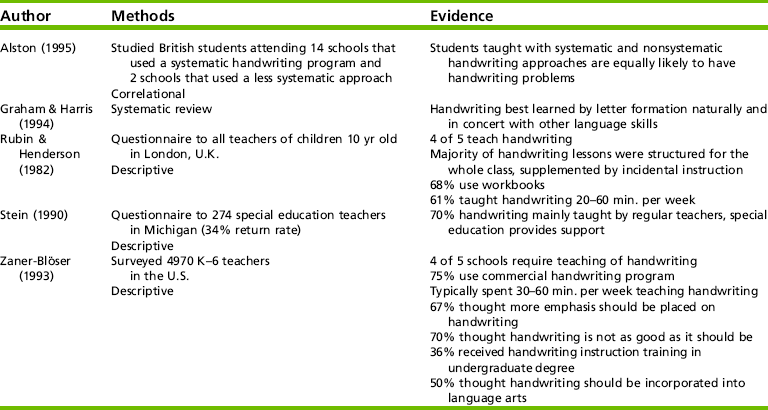

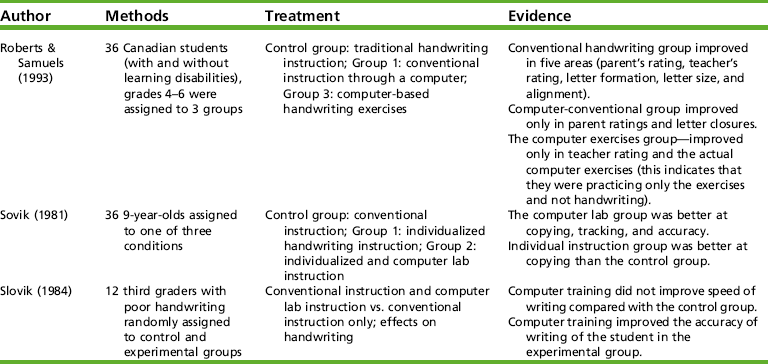

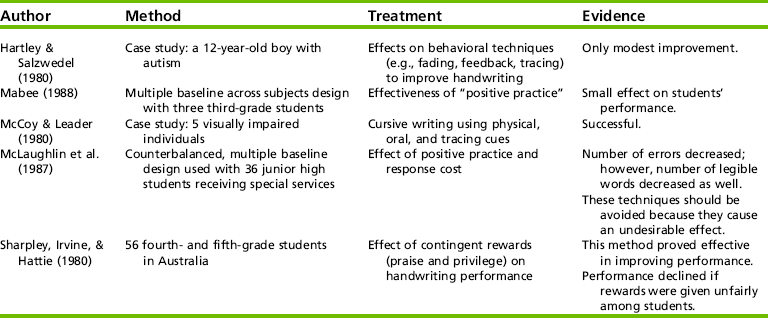

In the United States, traditional handwriting instruction programs vary from school district to school district and occasionally from school to school and grade to grade. It is not uncommon for occupational therapy practitioners to receive a referral for a child with poor handwriting who has never had handwriting instruction! See Table 19-3 for evidence on classroom instruction.

TABLE 19-3

Evidence on Classroom Instruction

Alston, J. (1995). Assessing writing speeds and output: Some current norms and issues. Handwriting Review, 102–106; Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (1994). The effects of whole language on writing: A review. Educational Psychology, 2, 187–192; Rubin, N., & Henderson, S. E. (1982). Two sides of the same coin: Variations in teaching methods and failure to learn to write. Special Education: Forward Trends, 9, 17–24; Stein, R. A. (1990). Teacher-recommended methods and materials for teaching penmanship and spelling to the learning disabled. ERIC Document Reproduction Service (ED 334 735), Michigan; Zaner-Blöser. (1993). The Zaner-Blöser Handwriting Survey: Preliminary tabulations. Zaner-Blöser: Columbus, OH.

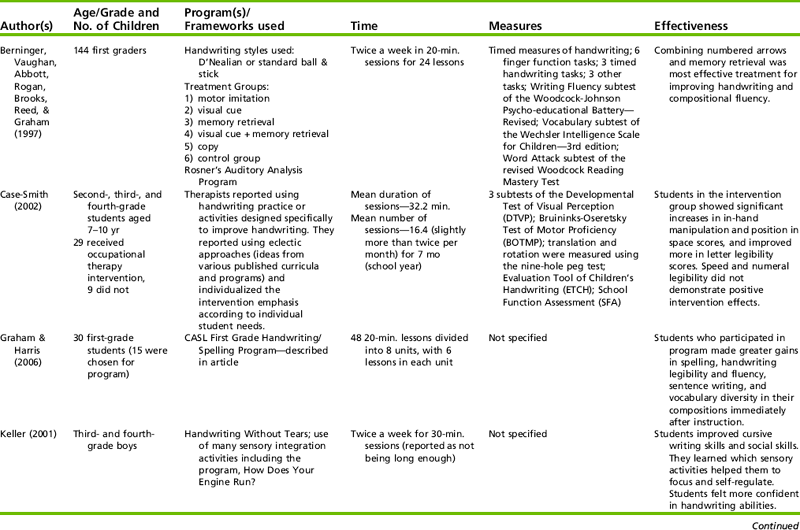

The most common instruction methods include Palmer, Zaner-Blöser, italics, and D’Nealian.4,36,105 See Appendix 19-B for a list of handwriting methods used in schools. Unlike the United States, a few countries, such as the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia,2,4,62,121 have adopted national curricula for handwriting to improve the standards of handwriting assessment and instruction within their school systems (see Appendix 19-C on the Evolve website for handwriting curricula). Early childhood handwriting curricula should include at least six skill areas: (1) small muscle development, (2) eye–hand coordination, (3) holding a writing tool, (4) basic strokes, (5) letter perception, and (6) orientation to printed language. See Table 19-4 for research on handwriting programs.

TABLE 19-4

Berninger, V., Vaughan, K. B., Abbott, R. D., Abbott, S. P., Rogan, L. W., Brooks, A., et al. (1997). Treatment of handwriting problems in beginning writers: Transfer from handwriting to composition. Journal of Education Psychology, 89, 652–666; Case-Smith, J. (2002). Effectiveness of school-based occupational therapy intervention on handwriting. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 56, 17–25; Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2006). Preventing writing difficulties: Providing additional handwriting and spelling instruction to at-risk children in first grade. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 38, 64–66; Keller, M. (2001). Handwriting club: Using sensory integration strategies to improve handwriting. Intervention in School and Clinic, 37, 9–12; Marr, D., & Dimeo, S. B. (2006). Outcomes associated with a summer handwriting course for elementary students. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60, 10–15; McGarrigle, J., & Nelson, A. (2006). Evaluating a school skills programme for Australian Indigenous children: A pilot study. Occupational Therapy International, 13, 1–20; Peterson, C. Q., & Nelson, D. L. (2003). Effect of an occupational intervention on children with economic disadvantages. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57, 152–160; Ratzon, N. Z., Efraim, D., & Bart, O. (2007). A short-term graphomotor program for improving writing readiness skills of first-grade students. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61,399–405.

Manuscript and Cursive Styles

A generally accepted sequence for handwriting instruction is manuscript writing for use in grades one and two, with children transitioning to cursive writing at the end of grade two or the beginning of grade three.12,17,51 The need for manuscript writing may continue throughout life, when students label maps and posters, adolescents complete job or college applications, and adults complete federal income tax forms. By middle school, many students have blended both manuscript and cursive to form their own style of handwriting. To date, no research has decisively indicated the superiority of one script style over the other.

Both manuscript and cursive possess complementary features, and these should be considered when the occupational therapist, child, child’s parent, and educational team are collaboratively deciding which style might best serve the child.

Manuscript is endorsed for the following reasons:

1. Manuscript letterforms are simpler and hence are easier to learn.

2. It closely resembles the print of textbooks and school manuals.

3. It is needed throughout adult life for documents and applications.

4. Beginning manuscript writing is more readable than cursive.

5. Ball and stick strokes of manuscript letter formations may be more developmentally appropriate than cursive letters for young children.

6. Manuscript letters are easier to discriminate visually than cursive ones.11,17,49,51

7. The traditional vertical alphabet is more developmentally appropriate, easier to read, and easier to write for young children, as well as easier for educators to teach, than the slanted alphabet.

Advocates of cursive writing point out the following:

1. Cursive movement patterns allow for faster and more automatic writing.

2. Reversal of individual letters and transpositions of words are more difficult than in manuscript.

3. One continuous, connected line enables child to form words as units.

4. Cursive allows the poor printer a new type of written format, which may be motivating at the child’s present maturity level.10,17,49,51

5. The brain is not developed for the fine visual–motor distinctions necessary for manuscript.63

HANDWRITING INTERVENTION

In school settings, if the referred child’s educational team decides that functional written communication is a priority for the child’s educational program, the occupational therapist may be instrumental in directing and guiding this aspect of the program. Typically, the team uses either a remedial or a compensatory intervention approach, or both, to improve the child’s written communication. Compensatory strategies improve a student’s participation in school with accommodations, adaptations, and modifications for certain tasks, routines, and settings,8,65,101 whereas remedial approaches improve or establish a student’s functional skills in a specific area.

When the team focuses on the occupation of written communication, generally both remedial and compensatory techniques are concurrently used. For example, Hunter, a second-grader, has manuscript handwriting that is unreadable, about 60% of his written letters are not legible, and his writing speed is at the bottom of his class. Although he participates in an intensive multisensory handwriting remediation program, he needs accommodations and strategies that help him achieve functional written communication in the classroom. Consequently, his teacher decided to adjust the time required to complete assignments, allow him to use oral reporting for certain class assignments, or require a lower volume of work to be accomplished than that of his peers. The teacher and the occupational therapist select specific techniques to assist him with legibility, such as spacing between words, sizing letters, and placing text on lines. Readiness activities that are easy to incorporate into the classroom can be embedded in his daily routine.

Initially, the child, the child’s parents, and the educational team need to achieve consensus regarding the type of script (e.g., cursive) and the method of handwriting instruction (e.g., Zaner-Blöser) that seems most advantageous for the child to use. Specific intervention techniques and the type, frequency, and duration of service delivery are selected.

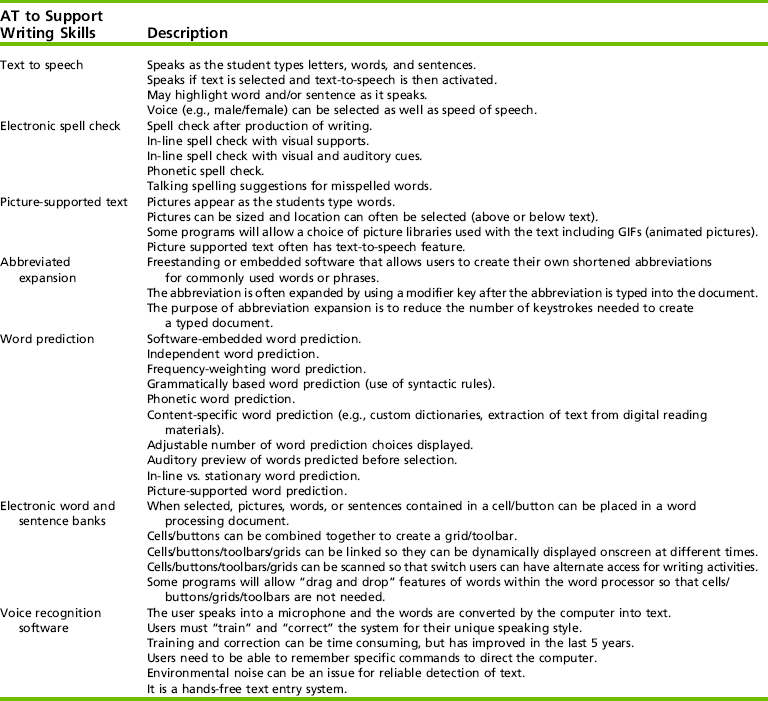

When a child’s handwriting is very illegible and slow, team members may occasionally decide to incorporate assistive technology, such as a computer or portable word processor. Both the student and the team, particularly the occupational therapy practitioner, must work hard to find a technologic system that allows the student proficiency in text generation.101 As in handwriting, computer use requires adequate attention, motor control, sensory processing, visual functioning, and self-regulation from the student. Hence, the computer is not a magical tool but one that allows the child to acquire keyboarding and word processing skills through planning, routine instruction, and practice. Two studies of upper elementary students with learning disabilities indicated that handwriting was a quicker mode of generating text than was keyboarding after several months of practice.74,76 Word processing with word prediction improved the legibility and spelling of written assignments for two of three children with learning disabilities in a single-subject design study.54 In this age of technology, it is important for all students to develop keyboarding skills for computer use in the classroom, workplace, and home. However, survival handwriting skills will continue to be needed throughout student and adult life. Table 19-5 lists the assistive technology features and the potential benefits of word processing for the student who struggles with handwriting. See Table 19-6 for a description of studies using computer-assisted handwriting instruction programs.

TABLE 19-6

Computer-Assisted Handwriting Instruction

Roberts, G. I., & Samuels, M. T. (1993). Handwriting remediation: A comparison of computer-based and traditional approaches. Journal of Educational Research, 87, 118–125; Sovik, N. (1981). An experimental study of individualized learning instruction in copying, tracking, and handwriting based on feedback principles. Motor Perceptual Motor Skills, 53, 195–215; Sovik, N. (1984). The effects of a remedial tracking program on the writing performance of dysgraphic children. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 28, 129–147.

Models of Practice to Guide Collaborative Service Delivery

Models of practice and strategies used by occupational therapists may be unfamiliar to children, educators, parents, and other school personnel. Therefore, the occupational therapist must be able to (1) clearly articulate intervention techniques, activity modifications, and classroom accommodations being used; (2) collaborate with the teacher and others to provide service in the least restrictive environment; (3) implement therapeutic strategies for improving written communication; (4) train others to work with children with handwriting problems; and (5) closely monitor the progress of the child and change aspects of the program to continue improvement.

The overall focus of the educational program is the improvement of student performance in a particular area (e.g., written communication). Occupational therapy models of practice that guide services to improve handwriting include (1) neurodevelopmental, (2) acquisitional, (3) sensorimotor, (4) biomechanical, and (5) psychosocial. Surveys of occupational therapists in the United States117 and Canada40 indicate that the most frequently applied theoretical approaches to children’s handwriting intervention are multisensory (92%, United States) and sensorimotor (90%, Canada). However, occupational therapists most often combine various theoretical approaches for handwriting intervention,40 and this use of multiple approaches is advocated in the pediatric occupational therapy literature.6,24,89

When considering any intervention plan for handwriting, practitioners should consider the far-reaching parameters of each model of practice along with the overlap and the interplay among them. The occupational therapist must be skillful in the use of one or several models of practice concurrently and in teaching others to implement strategies originating from these models of practice. By remaining focused on the child’s occupational outcome related to handwriting and applying various models of practice in the child’s educational program, the occupational therapy practitioner can provide appropriate opportunities for the child to learn and master the skill of written communication.

Neurodevelopmental

The neurodevelopmental theoretical approach is based on neurologic principles and normal development, focusing on an individual’s ability to execute efficient postural responses and movement patterns.60 This model of practice provides an ideal orientation for addressing problems of children who have inadequate neurodevelopmental organization evidenced by poor postural control, automatic reactions, or limb control.34 Decreased, increased, or fluctuating muscle tone, inadequate righting and equilibrium responses, and poor proximal stability may interfere with successful performance in fine motor activities such as handwriting.

Postural and arm preparation activities are an important component of a comprehensive handwriting program for children with mild neuromuscular impairments and sensory processing problems. For these children, preparing their bodies and hands for handwriting becomes the preliminary ingredient of handwriting intervention. Selecting preparatory activities to address each child’s specific deficits and carefully analyzing his or her response to these activities are both critical in the preparatory phase of the handwriting intervention program. Postural and arm activities can prepare children’s bodies to write by (1) modulating muscle tone, (2) promoting proximal joint stability, and (3) improving hand function.

Postural preparation to modulate muscle tone may involve activities to increase, decrease, or balance muscle tone. Traditional activities to increase tone include jumping while sitting on a “hippity-hop” ball and jumping on a mini-trampoline. In the classroom, activities to build tone and strength might include students placing their hands on the sides of their chairs and bouncing in place for a “popcorn ride.” They may hold that position with arms extended for a chair pushup. They may perform heavy work such as an arm pushup in a school chair (Figure 19-5).

For children whose muscle tone or activity level needs to be reduced, conventional slow rocking may be achieved by sitting astride a large bolster and moving from side to side to the rhythm of a child’s poem recited aloud. In the classroom before writing, a child’s postural tone may be decreased by rocking in a rocking chair to the beat of slow, rhythmic instrumental or vocal music from a headset, by snuggling into a beanbag chair, or by participating in a relaxing visual imagery exercise.

Children with poor handwriting frequently exhibit poor proximal stability and strength. To encourage co-contraction through the neck, shoulders, elbows, and wrists, young children may benefit from practicing animal walks, such as the crab walk, the bear walk, the inchworm creep, and the mule kick. Older children may prefer calisthenics, such as doing pushups on the floor or against the wall, performing resistive exercises with elastic tubing or Thera-Band, cooperatively pulling up a partner from a seated position on the floor, or practicing yoga poses that require weight bearing on the upper extremities. Figure 19-6 shows two children engaging in a yoga pose (London Bridge pose) to get ready for writing. Within the school setting, proximal stability also may be improved through everyday routines, such as cleaning blackboards and table tops or pushing and moving classroom furniture or physical education equipment.

Alternative positions during writing activities can enhance proximal stability during writing. The prone position requires weight-bearing on the forearms for writing, which increases proximal joint stability and may enhance disassociation of the hand and digits from the forearm.

When preparing to write, some children may also benefit from developing more coordinated synergies of the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the hand to improve overall hand function. Typically, the hand needs to be stable and strong enough to provide support for fingers to manipulate tools. In-class hand-strengthening activities include carrying heavy cases with thick handles, practicing knot tying with thick rope, and participating in games with magnets.8

Prewriting, handwriting, and manipulative activities on vertical surfaces can assist children in developing more wrist extension stability to facilitate balanced use of the intrinsic musculature of the hand.15 Activities requiring in-hand manipulation or the adjustment of an object after placement within the hand39 may be appropriate for children with deficits in handwriting (see Chapter 10). Translation, moving the writing utensil from the palm to the fingers of the hand, shifting the shaft of the utensil within the hand for proper grasp, and rotating the pencil from the writing to the erasing position are all in-hand manipulation skills needed for writing tool management.

A study by Cornhill and Case-Smith of 48 first-graders demonstrated a moderate to high correlation between handwriting skills and in-hand manipulation, specifically translation and complex rotation.29 Boehme suggested that vertical excursion of the writing line is produced by the flexion and extension movements of the digits, whereas horizontal excursion originates primarily from lateral wrist movements.22 Hence, the balanced interaction of the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the hand appears to be key to the dynamic, efficient, and fluid movements required for handwriting.

Acquisitional

Handwriting may be viewed as a complex motor skill that “can be improved through practice, repetition, feedback, and reinforcement” (p. 70).59 Graham and Miller recommended that handwriting instruction be (1) taught directly; (2) implemented in brief, daily lessons; (3) individualized to the child; (4) planned and changed based on evaluation and performance data; and (5) overlearned and used in a meaningful manner by the child.49 When therapists and educators employ these conditions in a positive, interesting, and dynamic learning environment, children are more likely to become efficient, legible writers.12,49,81 Therapeutic practice was more effective at improving handwriting performance than sensorimotor-based intervention.32

For occupational therapy practitioners, motor learning theories apply to handwriting instruction. Learning a new motor skill has been described as progressing through three phases: cognitive, associative, and autonomous.41 First, in the cognitive phase, the child is attempting to understand the demands of the handwriting task and develop a cognitive strategy for performing the necessary motor movements. Visual control of fine motor movements is thought to be important at this phase. A child learning handwriting in this phase may have developed strategies for writing some of the easier manuscript letters, such as o, l, or t, but may have more difficulty writing complicated letters, such as b, q, or g.

In the associative phase, the child has learned the fundamentals of performing handwriting and continues to adjust and refine the skill. Proprioceptive feedback becomes increasingly important during this phase, whereas reliance on visual cues declines. For example, in the associative phase a child may have mastered the formations of letters but is engaged in improving the handwriting product by learning to space words correctly, to write letters within guidelines, or to maintain consistent letter slant. Children continue to need practice, instructional guidance, and self-monitoring strategies of handwriting performance.

In the autonomous phase, the child can perform handwriting automatically with minimal conscious attention. Variability of performance is slight from day to day and the child is able to detect and adjust for any small errors that may occur.96 Once the child has reached this level of handwriting, his or her attention can be expended on other higher-order elements of writing44 or it can be saved to alleviate fatigue.96

Implications and strategies for handwriting instruction and remediation evolve from reviews of handwriting studies17,49,88 as well as motor learning theory.77 Many handwriting intervention programs are commercially available (see Appendix 19-C on the Evolve website for brief descriptions of and ordering information for these programs and a list of Internet resources). Each should contain a scope and sequence of letter and numeral formations along with successive instructional techniques. To date, no empirical evidence reveals one commercial handwriting program to be more effective than another.

The scope and sequence of the handwriting intervention program should focus on a structured progression of introducing and teaching letter and numeral forms. Frequently, letters with common formational features are introduced as a family, such as the lowercase letters e, i, t, and l. After the child has mastered these letters, she or he can use them immediately to write the words eel, tile, and little. Whether the chosen handwriting intervention method is a commercially available or a teacher- or therapist-prepared method, each child’s program should be individualized to consist of the letters that he or she has not yet mastered. Thus, the focus of the child’s program is to sequentially introduce new letters and use them with mastered letters, excluding letters the child is forming incorrectly or ones not known to the child, because this only reinforces unwelcome perceptual–motor patterns.119 Combining newly acquired letters with already mastered letters allows the child to write in a meaningful context (i.e., the formation of words and sentences). This immediate reinforcement of writing words is more powerful and purposeful for the child than writing strings of letters repeatedly.

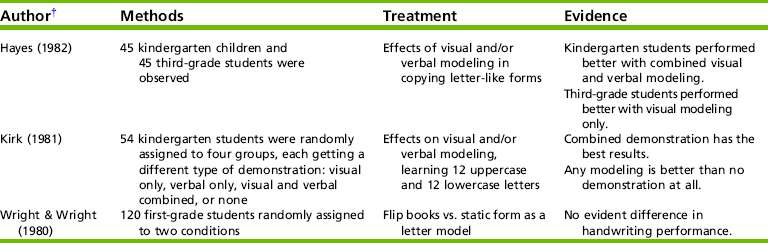

Instructional approaches of handwriting intervention programs vary but tend to comprise a combination of sequential techniques including modeling (Table 19-7), tracing, stimulus fading, copying, composing, and self-monitoring.6,17,81 When acquiring new letterforms, initially the child often needs many visual and auditory cues. However, the service provider fades the cues as soon as the child can successfully form the letter without them. Next, the child proceeds to copying letters and words from a model and then to writing letters and words from memory as they are dictated. Finally, the child advances to generating words and sentences for practice. In each phase, the child should be expected to assume responsibility for correcting his or her own work, also known as self-monitoring.17 Older children can refer to a written checklist addressing spacing, size, alignment, letterforms, and slant during the self-assessment of their writing. However, younger children may need to verbally evaluate letter formation and overall appearance aloud to the service provider.

TABLE 19-7

Evidence on Modeling for Teaching Handwriting*

*The evidence supports teacher modeling of letter formation prior to practice.

†Hayes, D. (1982). Handwriting practice: The effects of perceptual prompts. Journal of Educational Research, 75, 169–172; Kirk, U. (1981). The development and use of rules in the acquisition of perceptual motor skills. Child Development, 52, 299–305; Wright, C. D., & Wright, J. P. (1980). Handwriting: The effectiveness of copying from moving versus still models. Journal of Educational Research, 74, 95–98.

Acquiring handwriting skills and applying them in school means the educational team focuses not only on letter formation but also on the legibility and speed of the student’s handwriting. In addition to correct letterforms, other components of legibility include spacing, size, slant, and alignment. Spacing between letters and words, text placement on lines, and sizing letters often need direct modeling and instruction.

An effective writing surface for assisting students with text placement and size is a color-coded, laminated sheet. When accompanied by verbal cues from the service provider, this sheet provides immediate visual cues to the child learning letterforms. Beneath the solid, red writing baseline, the color brown represents the “soil” or “ground”; the space above the solid baseline and dashed black middle guideline are green for the “grass”; and the space above the dashed guideline to the top solid writing line is blue for the “sky.” For example, the letter h would start at the top of the sky, head downward, and end in the grass. This same pictorial scheme can be applied to lined paper for classroom assignments, allowing students strong cues for learning letter placement and size (Figure 19-7).8 Various strategies for addressing handwriting problems related to legibility components, classroom writing assignments, and speed are listed in Table 19-8.

Sensorimotor

The parameters for this model of practice, when applied by the occupational therapist with children with handwriting problems, include providing multisensory input through selected activities to enhance the integration of sensory systems at the subcortical level.99 When given various meaningful sensory opportunities at a level that permits assimilation, the child’s nervous system can integrate information more efficiently to produce a satisfactory motor output (e.g., legible letters in a timely manner). All sensory systems, including the proprioceptive, tactile, visual, auditory, olfactory, and gustatory, can be tapped within a handwriting intervention program, which is thought to enhance learning. Incorporating a sensory integrative approach into handwriting intervention entails the use of a variety of sensory experiences, media, and instructional materials. In addition, providing novel and interesting materials for children to practice letterforms may keep students motivated, excited, and challenged, thereby enhancing student success and learning. Children with handwriting difficulties who have experienced frustration with commonly used paper-and-pencil drills may respond much more favorably to handwriting instruction using this unique multisensory format. A study by Woodward and Swinth indicated that 90% of school-based occupational therapists used this approach; altogether, 130 different multisensory modalities and activities were documented, with therapists using 5 or more activities per student.117 Chalk and chalkboard were the most frequent format used, being selected by 87.3% of responding therapists.32 A study of the effects of two interventions (sensorimotor and therapeutic practice) for children 6 to 11 years old with handwriting dysfunction found that children who received sensorimotor intervention improved in some sensorimotor components but also demonstrated a decline in handwriting performance.117

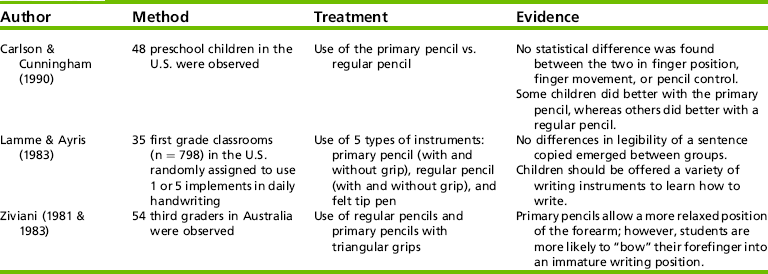

Writing tools, writing surfaces, and positions for writing are all integral parts of a sensorimotor approach. Examples of writing tools to be used are felt-tip pens (regular, overwriter, changeable-color), crayons (scented, glittered, glow-in-the-dark), paintbrushes, grease pencils or china markers, weighted pens, mechanical pencils, wooden dowels, vibratory pens, and chalk. Lamme and Ayris examined the effects of five different types of writing tools on handwriting legibility.69 Results indicated that the type of writing tool did not influence legibility, but the educators involved in the study reported that children’s attitudes toward writing were more positive when children were able to use a felt-tip pen rather than a No. 2 pencil. This suggests that children’s feelings about writing might improve when allowed to use a variety of writing tools. Writing with chalk, grease pencils, or a resistive tool also provides additional proprioceptive input to children, because more pressure for writing is required than with the traditional tools of paper and pencil. Unconventional writing tools can be easily incorporated into classroom assignments.

Writing surfaces may be in a vertical, horizontal, or vertically angled plane. Common vertical surfaces for writing include the chalkboard, painting easels, and poster board and laminated paper attached to the wall. These surfaces (e.g., desktop easels set at a slanted incline) facilitate a more mature grasp of the writing tool because a child’s wrist extension may result in more arching of the hand and an open web space between the thumb and fingers.16 Figure 19-8 shows a girl working on a homework assignment that is taped to a kitchen cupboard. An upright orientation may also decrease directional confusion of early writers when learning letter formations.51 On the vertical plane, “up” means up and “down” means down, as opposed to working at a desktop where “up” means “away from the body” and “down” means “toward the body.” Furthermore, standing in front of a chalkboard with the body in full extension and parallel to the writing surface may promote more internal stability of the trunk, increase neurologic arousal, and provide more proprioceptive input throughout the arm and shoulder and allow the hand to move independently or dissociate from the arm.6

FIGURE 19-8 A girl works on a homework assignment that is taped to a vertical surface (i.e., kitchen cupboard).

Handwriting practice on a horizontal surface can be performed using a variety of materials that provide additional sensory input to the child’s movement of the tool. Writing on plastic freezer bags partially filled with colored hair styling gel or trays filled with sand, dry pudding mix, clay, or a light coating of hand lotion provides unusual and reinforcing sensation. Writing on baking sheets or Styrofoam meat-packaging trays with isolated fingers or wooden dowels provides children additional tactile and proprioceptive input when forming letters, numbers, and words. Writing on textured wallpaper, nylon netting, finely meshed screen, or indoor–outdoor carpet squares also provides proprioceptive input.

Biomechanical

Ergonomic factors such as sitting posture, paper position, pencil grasp, writing instruments, and type of paper influence handwriting quality and speed. In this section, compensatory strategies—including adaptive devices, procedural adaptations, and environmental modifications to improve the interaction and fit between a child’s capabilities and the demands of the handwriting task—are presented. This model emphasizes modifications to the student’s context to improve handwriting and written production.

Sitting Posture: Although standing and lying prone may be encouraged as alternative writing positions, students continue to spend much of the school day seated at a desk. Therefore, the occupational therapist should immediately address the student’s seated position in the classroom. While writing, the student should be seated with the feet planted firmly on the floor, providing support for weight shifting and postural adjustments.16 The table surface should be 2 inches above the flexed elbows when the child is seated in the chair. In this position, the student can experience both symmetry and stability while performing written work. To facilitate appropriate seating for students, the occupational therapy practitioner may recommend adjusting heights of desks and chairs, providing footrests for children, adding seat cushions and inserts, or repositioning a child’s desk to face the chalkboard in the classroom.

Paper Position: Paper should be slanted on the desktop so that it is parallel to the forearm of the writing hand when the child’s forearms are resting on the desk with hands clasped.72 This angle of the paper enables the student to see his or her written work and to avoid smearing his or her writing. Right-handed students may slant the top of their paper approximately 25° to 30° to the left with the paper just right of the body’s midline. Conversely, a slant of 30° to 35° to the right and paper placement to the left of midline are needed for students using a left-handed tripod grasp.4 For the student with a left-handed “hooked” pencil grasp lacking lateral wrist movements, slanting the paper to the left is appropriate.16 The writing instrument should be held below the baseline, and the non-preferred hand should hold the writing paper.4

Pencil Grip: Benbow defined the ideal grasp as a dynamic tripod with an open web space.14 With the web space open (forming a circle), the thumb and index and middle fingers make the longest flexion, extension, and rotary excursions with a pencil during handwriting.16 Variations of grasps exist with some grips, making handwriting more difficult and less functional.109 Educational team members may consider modifying a student’s pencil grasp when the child (1) experiences muscular tension and fatigue, also known as writer’s cramp; (2) demonstrates poor letter formation or writing speed; (3) demonstrates a tightly closed web space that limits controlled precision finger and thumb movements; or (4) holds the pencil with too much pressure or exerts too much pencil point pressure on the paper.16

In attempting to modify a grip pattern, characteristics of the child are an important consideration. The occupational therapy practitioner should encourage a mature grasp in young writers and recognize that modifying a grasp pattern may be more successful with younger children.119 Once grip positions have been established, they are very difficult to change.14 In fact, by the beginning of second grade, changing a child’s grasp pattern may be stressful and not recommended.16 Therefore, the educational team needs to carefully consider a child’s age, cooperation, and motivation along with the child’s acceptance of the new grip pattern or prosthetic device before attempting to reposition the child’s fingers.