8 Touch and massage

Introduction

In certain countries the word ‘massage’ cannot be used by aromatherapists unless a massage certificate recognized by that country is held. In France and America a different name – ‘therapeutic touch’ – is often used which allows those not sanctioned by the government to carry out massage under a different name. The intention of the therapist is the same: to relieve tension and enable a beneficial result to take place.

Most aromatherapy schools teach their own specialized massage (or therapeutic touch); nevertheless, patients and clients can still benefit greatly from touch from an inexperienced or non-qualified person. Some massage movements are illustrated in this chapter for the benefit of those already qualified in aromatherapy and/or massage, and to encourage other nurses with a desire to use the simpler methods described. For the lay person or the busy nurse, knowledge of a few of the simpler techniques is an extremely valuable asset which can bring benefit to those needing care.

Touch and massage

Massage begins with touch, which all of us need; it conveys a feeling of warmth, relaxation and security – all beneficial to good health. There are many empirical examples of massage therapy effects, including reduction of pain during childbirth and lower back pain (Field 2000 p. 45), even without essential oils. The addition of essential oils with analgesic properties enhances the relief obtained by massage alone.

Massaging babies and infants can reduce pain associated with teething, constipation and colic, as well as inducing sleep (Auckett 1981). Studies carried out on preterm infants showed without doubt that massage was beneficial to their growth and development (Field et al. 1987). The babies were massaged for 15 minutes three times a day for 10 days in an incubator. Compared with the control group, 47% of the treated infants gained more weight and were hospitalized for 6 days less.

Patient benefits

Whether the causes of ill-health are biomechanical, psychosocial, biochemical or a combination of these, massage seems to be able to exert a beneficial influence (Chaitow 2000). Touch itself is a basic human behavioural need (Sanderson, Harrison & Price 1991) and ‘may be the only therapy which is instinctive; we hold and caress those we wish to comfort; when we hurt ourselves, our first reaction is to touch and rub the painful part’ (Vickers 1996).

As research and scientific developments in the efficacy of drugs forged ahead, close patient contact diminished and by the 1960s massage had more or less lost its therapeutic status in medical care. However, in the late 1980s and 1990s there was renewed interest by nurses in the value of touch, and now many hospitals and hospices are using massage to benefit their patients; during this time massage has been enhanced by the addition of essential oils, transforming the treatment into aromatherapy (Buckle 1997) (see Box 8.1). The benefits are further enhanced by the choice of essential oils used (Wilkinson 1995) – increased energy levels, reduced side effects from drugs, symptoms not treated by the hospital relieved and emotional problems eased. The effects can last longer than those of massage alone, owing to the therapeutic action of the essential oil components (see Chs 10–15).

Box 8.1 The Experiences and Meaning of Touch among Parents of Children with Autism attending a Touch Therapy Programme

Barlow and Cullen (2002) instigated a touch therapy programme aiming to enhance parents’ perceptions of closeness with their children and provide them with an alternative to verbal communication to promote the latter. Parents of children with autism were taught simple massage techniques over 8 weeks. Having practised massage with their children, parents reported that the children tolerated the massage and not only were routine tasks such as dressing tolerated more easily, but the children appeared generally more relaxed. Parents reported feeling closer to their children and that touch therapy had opened a communication channel between them.

Patients can benefit from a massage (simple or involved) given by any of the following:

• a physical therapist – without essential oils

• a physical therapist using essential oils ready blended by an aromatherapist

• a nurse with no professional massage experience, but with a sound knowledge of essential oils

• a nurse using essential oils under the direction of an aromatherapist

• a nurse using touch and gentle non-manipulative massage movements, without essential oils (see Introducing massage, below).

The most important thing to remember is that nothing can replace hands-on, when the giver (whether or not a qualified masseur/se) is caring and works within his/her capabilities, combining gentle touch with a loving attitude. With the right approach, beginning with a small non-intrusive movement, both the giver and the receiver can come to enjoy the care they are sharing, making it easier for the receiver to open up and become more relaxed in body and happier in mind (Worrell 1997). Authors agree that it is not necessary to spend an hour on a massage for it to be effective – people also benefit from a short period of dedicated time.

Physiological benefits

Massage increases the circulation of both blood and lymph, helping in the elimination of toxins from the body; it slows down the pulse rate, lowers blood pressure, releases muscle tension, tones underworked or weak muscles and relieves cramp.

Psychological benefits

Although these are perhaps not so easy to evaluate, they are significant and play their part in the holistic healing effect: relaxing an apprehensive mind, uplifting depression and despair, relieving panic or anger and, importantly, giving a person the feeling that someone cares enough to spend time giving the specialized contact brought by touch and massage.

Massage and aromatherapy – therapies in their own right

Professional massage

Several colleges run short courses that are not sufficiently comprehensive to confer a recognized massage qualification. To meet professional standards and be competent to give a full, professional massage,

Client assessment

Kay, a 42-year-old woman working in a family business, was referred for treatment by her GP, with severe anxiety and stress. Over the past 3 weeks, owing to business problems, she had become increasingly withdrawn and anxious. She was experiencing panic attacks (which left her clammy and freezing) in crowded places and also at night, which was disturbing her sleep pattern, thus she found it hard to wake up in the morning. She had extreme tension in her neck and shoulders, suffering headaches as a consequence. Her breathing tended to be shallow and rapid, and she had lost more than a stone in weight over the 3 weeks, partly due to lack of appetite.

Intervention

Because of the amount of anxiety she was experiencing she was taken through some breathing exercises before a full body massage, which was carried out using:

• 3 drops Chamamaelum nobile [Roman chamomile] – antispasmodic, calming, sedative

• 1 drop Rosa damascena [rose otto] – neurotonic

• 3 drops Origanum majorana [sweet marjoram] – analgesic, calming, neurotonic, respiratory tonic

Kay opted for treatment twice a week and after the first treatment said she felt much calmer and more relaxed. She was standing upright rather than being bent over with the shoulder tension, and said that her head felt much clearer.

She was given a blend of the following neat essential oils to use at home in the bath, and as an inhalant if required:

1 mL Valeriana officinalis [valerian] – sedative, tranquillizing

1 mL Chamaemelum nobile – properties as above

2 mL Lavandula angustifolia [lavender] – analgesic, balancing, calming and sedative, tonic

2 mL Origanum majorana – properties as above

3 mL Cananga odorata [ylang ylang] – balancing, calming, sedative

On her next visit Kay reported that she found inhaling the oils when particularly anxious had relieved the hyperventilation and helped her to relax; she had also started to incorporate breathing exercises into her routine.

After six treatments over 3 weeks, Kay felt sufficiently confident to go shopping without anxiety. She had also been able to resolve some of the problems at work. She was beginning to put weight back on and her appetite had returned to normal.

She therefore decided to reduce her treatments to once a week, and after 3 more weeks she felt able to resume some of her work duties, when she reduced her treatments to once a month. She had not ceased taking her medication during her aromatherapy treatment time, but 6 months after first commencing aromatherapy, her doctor felt he could reduce her medication over the next 3 months.

At this time, she found she was able to carry out her normal work schedule and once again enjoy social activities. … She now goes for aromatherapy treatments when she feels the need.

the therapist must know anatomy and physiology, understand the relationship between the structure and function of the tissues being treated, and be knowledgeable in pathology, as well as being skilled in the proper manipulation of tissues (Beard & Wood 1964 p.1).

Massage and aromatherapy

It would prevent misunderstanding of the word aromatherapy if the qualification in massage were totally separate from that of essential oil knowledge. As Vickers (1996 p. 15) so rightly says, ‘massage and aromatherapy should be judged on their own merits’. This ‘combined’ situation arose because aromatherapy was originally aimed at and studied by beauty therapists only, and massage is part of their training.

Aromatherapy schools in the 1970s taught their own specialized massage to beauty therapists; many placed too much emphasis on the massage and barely any on the essential oils. This situation has been regulated to a certain degree by the Aromatherapy Council (AC), which stipulates the number of hours to be spent on massage, anatomy and physiology and on essential oil knowledge in order for an aromatherapy course to be accredited by them (see Ch. 17).

Because the aromatherapy and massage are linked, neither is taken to its full potential: the massage training of aromatherapists is not as thorough as that of a physical therapist and the essential oil training is not as deep as that of an aromatologist (therapist qualified in aromatic medicine) and member of the Institute of Aromatic Medicine (see Ch. 9).

Beneficial effects of massage

Massage is widely recognized as providing the following benefits; it:

• induces deep relaxation, relieving both mental and physical fatigue

• releases chronic neck and shoulder tension and backache

• improves circulation to the muscles, reducing inflammation and pain

• relieves neuralgic, arthritic and rheumatic conditions

• helps sprains, fractures; breaks and dislocations heal more readily

• promotes correct posture and helps improve mobility

• improves, directly or indirectly, the function of every internal organ

• improves digestion, assimilation and elimination

• increases the ability of the kidneys to function efficiently

• flushes the lymphatic system by the mechanical elimination of harmful substances (especially toxins due to bacteria) and waste matter

• helps to disperse many types of headache (or migraine) originating from the gallbladder, liver, stomach and large intestine, and also those of emotional origin (including premenstrual syndrome or PMS)

• stimulates both body and mind without negative side effects

• helps to release suppressed feelings, which can be shared in a safe, confidential setting

• is a form of passive exercise, partially compensating for lack of active exercise.

These combined benefits not only result in increased body awareness, but also produce better overall health. Studies carried out in hospitals and private practice have shown that massage with essential oils greatly enhances and prolongs the health-giving effects.

Simple massage skills

The most easily acquired massage skills are:

• Stroking, which comes under the heading of effleurage movements (perhaps the most important for hospital use), for which the whole of both hands from fingertips to wrist should be used. Stroking is simply an extension of touch and, as well as being one of the simplest, is one of the most important movements in massage.

• Frictions, which come under the heading of petrissage (a deeper and more energetic series of movements than effleurage), and in which either the thumb or one or more fingers are employed. ‘Rubbing it better’ is a simple friction movement. The Hippocratic writings (from the Hippocratic collection 460–357 BC) remarks that ‘the physician must be experienced in many things, but assuredly also in rubbing, for rubbing can bind a joint that is too loose and loosen a joint that is too hard’.

Client assessment

After suffering a major depressive episode where she had brief reactive psychosis, Miss L was hospitalized for 1 week.

Shortly after her return from hospital she stopped taking her medication. She was advised against this, as it is possible for a relapse to occur, but she was adamant as she said it was making her feel worse. She also suffered from lower back pain through sitting for long periods at her knitting machine – an improved posture for knitting was suggested, although Miss L had not felt able to do any since leaving hospital. She used to do aerobics, but again, not since leaving hospital. She was not sleeping well and had PMS before her periods.

Intervention

It was felt important to tackle her emotional problems as well as the physical, and six weekly massage treatments were undertaken, using the following essential oils:

Outcome

She experienced great relief after the first massage and that night had a good night’s sleep, feeling relaxed for several days afterwards.

After the second one her back felt much better – she was able to move more freely, although her sleeping pattern was not back to normal. It was therefore decided to give Miss L the same essential oils to use at home, in two blends:

1.5 mL of each oil in a 10 mL bottle, 6–8 drops of which was to be put into a bath at least 2–3 times a week

3 drops of each oil in 50 mL in oil of Vitis vinifera [grapeseed], to massage into her shoulders and neck every night before retiring

By the fourth treatment, Miss L had recommenced her aerobic classes, as her back felt so much better all the time. She was also sleeping as well as before her illness.

Because of this, a month was left before each of the remaining two treatments, the improvements remaining stable.

Everyone has an innate ability to perform these two movements correctly and safely without the need for long training; both are taught thoroughly on aromatherapy courses.

Three further techniques, requiring greater skill and best learned on an accredited massage course, are:

• Kneading (a form of petrissage), involving use of the palm, the palmar surface of the fingers, the thumb, or thumb and fingers working together, is a squeezing and ‘pulling’ movement, often used on the shoulders and the thighs.

• Percussion, where the outside of the hands and fingers continually make and break contact with the body in a definite rhythm, is not normally used in aromatherapy.

• Lymph drainage is only briefly covered in an aromatherapy training programme. It is fully covered on a Vodder technique course.

Effleurage

Effleurage is the basis of all good massage. It can be used on its own, at the beginning and ending of a massage and also in between other types of movement. It consists of two types of stroking, using the whole hand or hands, which should mould themselves to the shape of the part of the body being massaged. The strokes are either deep (i.e. with pressure) or superficial (without pressure). Sometimes only part of the hand is used – perhaps only two fingers on a small area or on a baby.

Deep stroking with both hands is accomplished by moving up the part of the body being massaged with pressure towards the heart; its purpose is to assist the venous and lymphatic circulation by physical effect on the tissues.

Superficial stroking is effected without pressure and in any direction (the pressure is so light that the circulation is not directly affected). The perfection of this technique can require skill and long practice. In simple massage, superficial effleurage is mostly used as the return movement of deep effleurage, moving away from the heart back to the starting position.

Effleurage is used mainly to relax the recipient both mentally and physically and to improve the vascular and lymphatic circulation. Many different types of strokes come under this heading, but all should follow the basic principles above.

Frictions

Frictions are another form of compression massage, or kneading. They may be performed with the whole or the proximal part of the palm of the hand or with the thumb and fingers to carry out circular movements over a restricted area. There are two types of frictions:

1. Fixed frictions move the superficial tissues over the underlying structures, i.e. the part of the hand used is ‘stuck’ firmly to the client’s skin, which is moved over the tissues beneath by making circles.

2. Gliding frictions move over a small area of the skin surface and may also progress along a specific path.

Frictions are primarily used to break down fibrous knots, loosen adherent skin, loosen scar tissue, relieve tension nodules in the muscles and increase the circulation in a specific area.

Other factors

Learning the different movements is only part of massage training. Equally important is the way in which these movements are performed. Essential factors to consider are contact, the direction of movement, the amount of pressure, the rate and rhythm of the movements, the medium used, the position of both patient and therapist, and the duration and frequency of the treatment (Beard & Wood 1964 pp. 37–40). Further factors include the need for full contact with the patient and complete relaxation of the masseur’s own hands and arms because hard, tense hands transfer tension (and possibly pain) to the recipient. The mind should be cleared of any intruding, disruptive thoughts: the wellbeing of the client and how he/she can benefit must be uppermost.

The following principles need to be absorbed at the same time as the actual movements are learned.

Contact

No part of the human body is flat; nevertheless, when using effleurage (stroking movements) there should be full hand contact with every part of any large area to be massaged (Price 1999). Nothing breaks the relaxing effect of massage more than the repeated lifting off and replacing of hands. Fully relaxed hands and fingers maintain this contact by following the body’s contours closely, draping themselves over the body like silk. The hands should remain in contact with the body for both outward and return journeys of all movements made in sequence: lifting off disrupts the flow of the massage as a whole (Price 2000 p. 203).

Pressure

In effleurage on a large area pressure should always be concentrated on the palm of the hand (Price 2000 p. 201). The fingers should be kept completely relaxed because pressure from fingers is not relaxing – finger pressure should be used in friction movements only. Normally, palm pressure should be applied only when moving towards the heart, with none on the return journey. One of the aims of massage is to stimulate the circulation (the return of venous blood is not easily accomplished by the heart – pressure towards the heart increases the rate of circulation. The lymphatic flow is also increased, ridding the body more quickly of any harmful substances.

Pressure in frictions using the thumb or finger pads needs to be firm, but care must be taken to use the whole finger pad and not to dig in with the tip.

Speed

This depends to a certain extent on the effects to be achieved. Generally speaking, massage is given to relax the recipient, and a rate of approximately 15 strokes a minute for a long stroke (e.g. hand to shoulder) is considered correct (Mennell 1945) or 18 cm (7 inches) per second (Beard & Wood 1964 p. 38). Anything faster than this is used only if the massage is intended to be stimulating.

Rhythm

Uneven or jerky movements are not conducive to relaxation and care should be taken to maintain a smooth, unbroken rhythm (Price 2000 p. 203). While massaging, relaxing music with a gentle rhythm can be of great help in sustaining continuous, fluent and flowing effleurage movements. Frictions also should be performed rhythmically (Beard & Wood 1964 pp. 10–11).

Continuity

Most massage is carried out to relax both mind and body, so the movements themselves (and the changeover from one movement to another) should be smooth and unnoticeable to the recipient. The whole area receiving massage should be covered without a break in continuity, contact or rhythm (except when carrying out percussion).

Duration

The duration of a massage session depends on how much of the body is to be massaged, the age of the individual, the size of the body and the enjoyment level of the recipient. Massage sequences suggested in this book last between 5 and 15 minutes depending on the area to be massaged. Ten minutes of massage normally provides sufficient relaxation to induce a good night’s sleep.

Frequency

The frequency of massage treatment depends to a great extent on the pathological condition of the patient, as does the type of massage given. ‘It is generally believed that massage is most effective daily, although some investigators have suggested that it is more beneficial when administered more frequently and for a shorter duration’ (Beard & Wood 1964 p. 39).

Contraindications to massage

Contraindications to massage depend very much on the type of condition suffered. The lists below should be consulted to determine whether massage of any kind is appropriate or not.

Illness

Whole-body massage is not taught in this book and is contraindicated in the situations described below, but specific area massage (e.g. shoulders, hands and arms, feet and lower legs, face and scalp) is acceptable in most instances.

• Infection. The advice of the microbiologist or the infection control nurse should be sought.

• Pyrexia. If the client feels well enough an appropriate specific area could be massaged gently, using oils to give a cooling effect (e.g. include 0.5–1% peppermint in the blend).

• Severe heart conditions. Permission from the doctor or specialist must be obtained for whole-body massage.

• Medication. If the patients is on strong (and/or many types of) medication, specific-area massage only should be used.

• Cancer. There is some controversy regarding massage, and aromatherapists report that consultants can give conflicting advice. Some say that it is not advisable to encourage movement of the lymph as this may promote migration of the cancer to another area of the body; others say that moving the lymph and thereby encouraging the elimination of toxins (possibly some of the cancer cells also) could be beneficial (see Ch. 15). It is the opinion of Horrigan (1991) that, although surface massage will not cure cancer by natural means, it will not:

Localized damage

In the following situations the site of any trauma should be avoided, although other areas can be massaged:

• Inoculations. The site of an inoculation given within the previous 24 hours should not be massaged.

• Recent fractures and recent scar tissue. The healing of scar tissue can be hastened by the gentle application of essential oils in a carrier oil or lotion, or spraying them in a water carrier on to the site if touch cannot be tolerated.

• Bruises, broken skin, boils and cuts. If small, these can be covered with thin transparent tape before proceeding with the massage.

Normal physiology

In the following situations whole-body massage is contraindicated, although specific-area massage is allowed:

• Hunger. If 6 hours or more have passed since any food intake, or if the patient feels hungry, fainting may occur with whole-body massage.

• Digestion. Immediately following a heavy meal, the digestive system is working full time and whole-body massage could cause either nausea or fainting.

• Alcohol. After recent alcohol intake, full body massage and certain essential oils can intensify the effects of alcohol, possibly causing dizziness, or a floating feeling. Specific-area massage does not have this effect and the amount of any essential oil used (in the recommended dilution) would be too small to contraindicate their use.

• Perspiring. Immediately after exertion, sport, a long hot bath or sauna, the body is excreting sweat and heat and absorbs essential oils with difficulty. It is advisable to wait 20–30 minutes before whole-body massage, although a 10–15-minute wait is adequate for specific-area massage.

• Menstruation. During the first 2 days of menstruation bleeding could be increased by whole-body massage. However, specific-area massage can help to relieve congestion and soothe any pain or discomfort.

Varicose veins and oedema

These two conditions are often believed to be unsuitable for massage. In fact, both can be alleviated by essential oils used in light effleurage. Special care is needed in the execution of the massage, and only gentle, almost superficial, upward effleurage strokes should be used.

• Varices. The area above the damaged valve should be cleared first with deep, firm, upward effleurage strokes, before commencing the light upward strokes on the affected area itself.

• Oedema. This condition must be treated by a precise technique. When present in an ankle the massage should begin with the upper leg, because it is important to clear this area first before attempting to relieve the oedema. Treatment of the lower leg should then be carried out, returning to the upper leg at intervals during the massage and to finish. The affected part must be elevated while giving the massage (Beard & Wood 1964 pp. 38, 60, 104).

Massage sequences

A technique for introducing massage and essential oils to a client or patient is given first, followed by some simple massage techniques, easily carried out after attending an introductory course on the subject.

Introducing massage

For some, close contact with patients can be ‘a daunting commitment. Staff may need training to deal with the emotions massage may bring up’ (quoted in Tattam 1992). In order not to take patients’ anxieties on board, the therapist (or nurse) should endeavour to be empathetic, rather than sympathetic. Not everyone enjoys the thought of touching others (or being touched), but this can be overcome if a strong desire to help the patient and the pleasure of seeing a positive reaction makes it worth the effort.

The easiest part of the body to start with is the hand, as few people have a hang-up about shaking hands. The ‘handshake technique’ is also an excellent way of introducing the aroma of essential oils. Before going to see your patient, put a very small amount of carrier oil on your hand, add one or two drops of an essential oil – or one drop each of two (that you think the client may like) – and rub your hands gently together briefly, just to distribute the oils evenly.

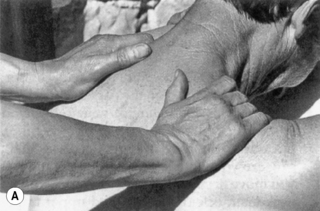

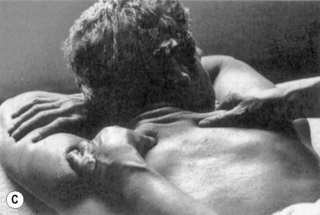

1. Take your patient’s right hand in yours as if to give a firm handshake (palm to palm – see Fig. 8.1A) and place your left hand over the top of the patient’s hand, relaxing your fingers to ‘cradle’ his or her hand in a sandwich (Fig. 8.1B). While you are holding his or her hand, ask the usual questions, such as ‘Did you have a good night?’ or ‘How is your back this morning?’ Your patient is bound to notice the aroma and comment on it. As you explain, you can say that essential oils are used for massage too; if the patient reacts well to the aroma – and shows interest – you can begin moving your left hand over the patient’s hand in a stroking movement – even continuing over and around the wrist if the patient appears to like it. Ask if he/she would like the other hand to have a turn, and if so repeat the ‘handshake’, then follow steps 2 and 3 below.

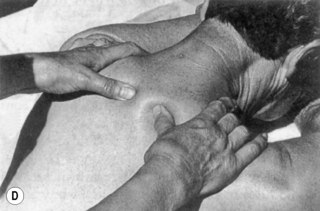

2. Still holding the hand, gently raise the patient’s forearm slightly, leaving the upper arm resting on the bed. Keeping your fingers in complete contact with the arm, begin to move your left hand firmly up the outer side of the lower arm (Fig. 8.1C); turn at the elbow, moving your palm underneath the arm and return gently to the wrist down the inner side of the arm (Fig. 8.1D). Turn your hand, bringing it back to the starting point.

3. Repeat the movement a few times, then suggest to your patient that you do the other hand to keep the body in balance.

Once you are confident and the patient is happy about being touched, the following sequences can then be carried out, allowing the essential oils to enter the bloodstream and give the desired benefits.

Hand and arm massage

1. Start with movements 1, 2 and 3 above, repeating three or four times. Where possible, take this stroke right up to and around the deltoid muscle and ‘cradle’ the whole shoulder, returning via the inner side of the arm, to finish at the wrist.

2. Still holding the patient’s hand as in Fig. 8.1A, make large friction circles with the left thumb from wrist to elbow on the upper side of the arm, returning with a single superficial stroke as in step 1. Repeat three or four times.

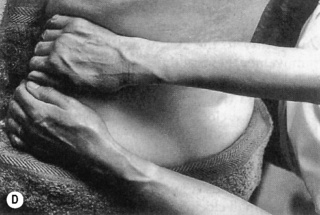

3. Turn the arm over, now holding the patient’s hand in your left hand: placing the fingers of the right hand on the lateral side of the forearm, make friction circles with the right thumb between the radius and ulna as far as the elbow, returning gently via the lateral side of the forearm to the wrist, with fingers underneath (Fig. 8.2A). Repeat three or four times.

4. Leaving the fingers of both hands at the back of the wrist, push the thumbs firmly back and forth several times over the inside of the wrist in a zig-zag movement, (Fig. 8.2B).

5. Slide the fingers down until they cover the back of the hand and stroke up the palmar muscles firmly, using the whole length of each thumb alternately, from finger level to wrist, several times (Fig. 8.2C).

6. Turn the hand over and repeat wrist zig-zags as in step 4, on the dorsal side of the arm.

7. Move your fingers down until they cover the patient’s palm and stroke firmly between the metacarpals along their full length, right thumb between patient’s thumb and first finger (returning via the radial side of the hand) and left thumb between third and fourth fingers (returning via the ulnar border of the hand). Repeat these strokes, this time with your right thumb between the patient’s first and second fingers, and the left between the fourth and fifth fingers (Fig. 8.2D)

8. With your right hand still supporting the patient’s palm make friction circles with your left thumb up the little finger; at the base, turn your own palm uppermost and, using your first finger and thumb, slide down the sides of the finger to the tip (Fig. 8.2E,F). Move to the ring finger and repeat the frictions and return movement. Repeat on the other two fingers, using your right thumb to massage the patient’s thumb.

9. Push the fingers of your left hand through your patient’s fingers (Fig. 8.2G) and, holding the patient’s forearm with your right hand, rotate the wrist slowly and firmly anticlockwise, then clockwise.

10. Smoothly change to the handshake hold and repeat step 1 several times.

To treat the patient’s left hand, reverse the directions for ‘right’ and ‘left’ in the above text.

Foot and lower leg massage

When massaging the feet, it is very important to hold – and touch – the foot firmly. Many people have a dread of someone touching their feet, and in the majority of cases this can be attributed to having had their feet held so lightly that it felt ticklish or insecure – and thus unpleasant.

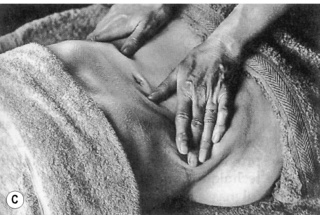

1. Place your hands across the top of the right foot at toe level (Fig. 8.3A) and move them firmly up the lower leg to the knee. Separate them on each side of the leg, returning gently to the ankle (Fig. 8.3B); turn the hands as you reach the toes, ready to repeat the movement three or four times.

2. When you have mastered this, incorporate the following ‘sandwich’ into the last part of the movement. As you approach the foot on the return journey, let the fingers of your right hand slide across the instep onto the sole of the foot, meanwhile turning the fingers of the left hand across the top of the foot towards the wrist of your right hand (Fig. 8.3C,D), squeezing both hands together as they move towards the toes. Lift off your right hand only, replacing it in front of (or behind) the left hand, ready to repeat the whole of movement 1 (with the sandwich) several times.

3. On the last journey hold the foot firmly in the sandwich for a moment or two, before progressing to the next movement.

4. Turn your hands so that your fingers are underneath the foot and with your thumbs carry out gentle frictions on the metatarsals – as in the hand massage (Fig. 8.3E). The frictions need to be gentle because this area of the foot is often tender, owing to poor lymphatic circulation or bronchial conditions (which the movement can help if done regularly).

5. Bring your fingers back to the anterior surface of the foot and move them towards the ankle bone (Fig. 8.3F). Make firm circles round both sides of the ankle bone with the first and second fingers (Fig. 8.3G), relaxing the pressure as you come to the front of the foot. Repeat these circles several times. This movement covers the foot reflex point for the groin lymph and is ideal for relieving lymphatic congestion in the groin and increasing circulation in the legs generally.

6. Turn your hands into the position for movement 1 and repeat this movement (together with the sandwich, as in movement 2) several times, finishing by continuing the squeezing movement slowly until you are no longer in contact with the foot. For the left foot, reverse directions for ‘right’ and ‘left’ in the text. Should you wish to increase leg circulation further, ask the patient to bend her knee, placing the foot flat on the bed. Sit on the toes (place a towel over them to protect your clothes from the oil if necessary) and continue as follows:

7. Carry out movement 1 several times, but only from ankle to knee.

8. Slide one hand to the back of the leg and move it with pressure up the gastrocnemius muscle, following with the other hand, then the first hand again, etc. – about 10 alternate strokes in all (Fig. 8.3H).

Shoulder massage

As a general rule, tensions and anxieties manifest themselves first of all as tension nodules in the trapezius muscle. This is not always apparent as continual pain, but can be felt immediately when someone presses firmly on the precise area of the taut muscular fibres (nodules).

The best time to give a shoulder massage (unless needed at any time to dissipate a headache) is just before retiring; this not only hastens sleep itself, but ensures a more relaxed body during slumber, which in turn puts the body into a healing mode.

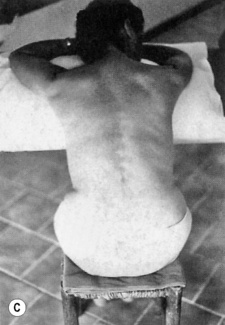

If a special back and shoulder massage stool is not available, the best position for the patient is to sit straddled on a chair with a low back. There should be a pillow over the chair back, on which the arms and head can rest. This position is not always possible, and depends on the age and health of the patient. If it is impractical, the patient may sit normally on a stool or low-backed chair. Then proceed as follows:

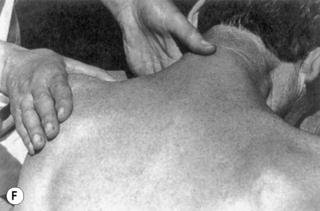

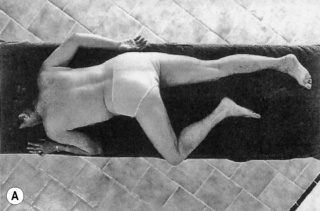

1. Your feet should be about 45 cm apart, so that the knees can bend easily for carrying out movements effectively, without strain. Shake your hands to ensure that they are completely relaxed, before placing them gently, one over each shoulder (Fig. 8.4A).

2. Take your relaxed hands (you should be able to see a space between each finger) across the clavicles, cradling each deltoid muscle and across the latissimus dorsi to the base of each scapula – when your wrists will be pointing towards the spine; turn your hands until the fingers almost face one another (Fig. 8.4B). Move firmly with pressure up the back – one hand on either side of the spinal column – until you reach the clavicles again, with your fingers ‘draping’ over the shoulders as at the start. Repeat this three or four times.

3. Keeping your fingers on each clavicle, make friction movements with your thumbs across the upper trapezius from the neck to the point of the shoulder (Fig. 8.4C). Repeat this several times.

4. Keeping the fingers in the same position, stretch the thumbs down the spine as far as they will go without undue effort. Place them in the spinal channels and make friction circles up the channels as far as possible without exertion (Fig. 8.4D). Repeat this several times, circling several times on any one spot where you feel tension, before continuing.

5. Move round to the left side of the chair (keeping the left hand in contact with the patient), so that the patient’s shoulder is directly facing the centre of your body. Feet should still be about 45 cm apart, as before. Open your hands as shown in Fig. 8.4E and, as you place the ‘V’ of the left hand on the point of the shoulder, bend your right knee (swinging the body to the right) and stroke up the deltoid to the hair line – your fingers will be in front of the shoulder and your thumb behind. As you reach the hair line, swing your body over to the left, bending your left knee, and stroke up the same area with your right hand as your left hand slides off the back of the neck (Fig. 8.4F). This time your thumb is in front of the shoulder and your fingers behind. Continue this alternate effleurage for a moment or two.

6. With your thumb, feel for painful tension nodules in the deltoid muscle. Firmly make friction circles over the knotty tissue with your thumb cushion (Fig. 8.4G). If the thumb tires too quickly, use the full length of both thumbs in single alternate strokes.

7. Repeat the shoulder effleurage described in movement 5.

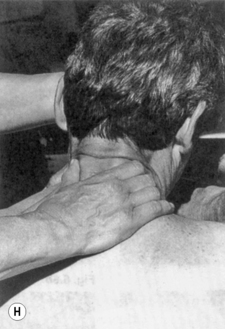

8. Leaving your right hand on the shoulder, place your left hand on the patient’s forehead and, keeping the fingers of your right hand separated from your thumb (as in movement 5), place the ‘V’ so formed at the base of the neck (Fig. 8.4H). Move firmly up the muscles of the neck, squeezing your thumb and fingers together as you move towards the hair line. Without lifting your hand from the patient, relax down to the base of the neck and repeat several times.

9. Keeping your hands on the patient, walk round to the back of the chair and repeat movement 2.

10. Keeping the left hand in contact, walk round to the right-hand side of the chair and repeat movements 4, 5, 6 and 7 on the other shoulder.

11. Without lifting your hands, walk round to the back of the chair and repeat movement 2, finishing at the base of the scapula with wrists together, and gradually and gently bring your fingertips to the centre and lift off.

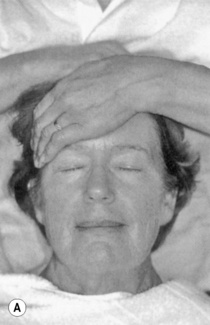

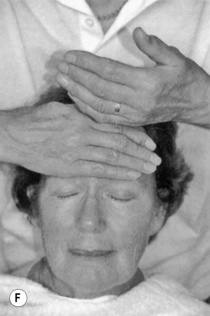

Forehead massage

Standing behind the patient’s head, lay your hand across the forehead with the fingertips of the left hand on the right temple and the length of the hand lying along the forehead (as in Fig. 8.5A). Move the hand slowly and gently across to the left temple (Fig. 8.5B), keeping contact as long as possible until the fingertips are almost on the hair. Before lifting off the hand, place fingertips of the right hand on the left temple, laying the length of the hand across the forehead and moving across to the right temple (Fig. 8.5C). Keeping the continuity and rhythm, repeat the two strokes with alternate hands for a few minutes. This stroke can also be done in an upward direction, but good contact must be maintained (Figs 8.5D–F).

Case study 8.3 Arthritic pain and mobility

Client assessment

Mrs M, 75 years of age and in general good health, was positive and outgoing. She was very active and did not look or act her age. The pain from her neck and shoulder caused her some problems, as she found it difficult to get comfortable in bed and in the morning she was very stiff.

Intervention

A back massage was suggested, followed by a neck and shoulder massage. She attended the clinic on a weekly or fortnightly basis. The following oils were used for the massage:

• 2 drops Eucalyptus citriodora [lemon scented gum] – analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antirheumatic

• 2 drops Piper nigrum [black pepper] – warming, analgesic

• 2 drops Zingiber cassumunar rhiz. [plai] – anti-inflammatory

Home treatment: 10 drops of each of the essential oils above were blended into 100 mL of white lotion, which she applied at bedtime and if the pain bothered her during the day.

Outcome

Over a period of 2 weeks there was a great improvement in the mobility of her neck; there was also much less pain. She noticed that if it she did not have her massages regularly her neck and shoulders began to stiffen and her mobility reduced.

After six treatments she left a longer interval between treatments – a month to 6 weeks – but continued to use the home treatment prescribed.

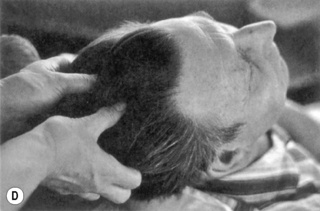

Scalp massage

If you have been giving a forehead massage, scalp massage follows naturally. No further oil is needed because your hands will still be lubricated from stroking the forehead. When executed gently and firmly, massage of the scalp is exceedingly relaxing. If the patient wishes to receive a scalp massage only, gently place under the nose a small amount of the diluted oil you would have selected had you been massaging part of the body. Then proceed as follows:

1. Place the hands on the scalp as shown in Figure 8.6A and, without moving the fingers through the hair, move the scalp firmly and slowly over the bone beneath.

2. Place the hands as shown in Figure 8.6B and, once again, firmly and slowly move the scalp over the bone beneath.

3. Move the hands to another position and repeat.

4. Repeat movements 1, 2 and 3 several times.

5. Place the hands as shown in Figure 8.6C and bring the thumbs and fingers (stroking the scalp all the way) to meet each other at the centre of the scalp (Fig. 8.6D), then gently draw the fingers and thumbs through the hair to the ends.

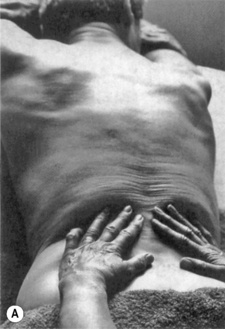

Simple back massage

In a hospital situation this should be kept reasonably brief unless it can be carried out on a massage bed of the right height, to ensure the correct posture of the therapist, thereby preventing backache. The feet should be approximately 45 cm apart, the rear foot facing in towards the bed, the front foot pointing towards the patient’s head. Stand level with the patient’s hip, enabling you to reach the shoulders without strain. To follow the directions given here, it is necessary to stand on the patient’s right-hand side.

1. Check that your hands are relaxed and use the whole hand, starting with hands on either side of the patient’s spine at the level of the sacrum, fingers pointing towards the opposite shoulder (Fig. 8.7A). Effleurage up the back (covering as much as possible with relaxed hands), pushing upwards with both hands and then round the deltoid (Fig. 8.7B). Return with a superficial stroke right down the sides of the body before bringing the hands back to the starting point. Turn the hands and repeat the movement several times.

2. Repeat the same movement several times around the deltoid muscle only, finishing with the fingers over the shoulders.

3. Lift up your palms only, leaving your fingers lying over the top of the shoulder and, using the thumbs, make friction circles on the deltoid across the shoulders (Fig. 8.7C).

4. Place thumbs into the hollow channels on either side of the spine at the base of the neck, making small circles there with pressure on the upward half of each circle. The return journey of the circle should progress downwards so that the next circular movement will finish a little lower down the back. Extend the return of each circle until the thumbs are at waist line. Repeat movement 1 several times, then turn to face the patient, with your feet 45 cm apart and the centre of your body opposite the patient’s waistline.

5. Place both your hands on the gluteus maximus muscle farthest from you (Fig. 8.7D). Move your left hand straight across towards you with pressure on the initial lift (Fig. 8.7E). As your left hand returns to the left side of the body, move your right hand towards you to the right side of the body (Fig. 8.7F,G). As your right hand returns to the left side of the body, your left hand moves towards you again – to the right side. At every move, each hand is directed slightly higher up the body. Continue this two-way movement almost to the armpits, sliding both hands in a superficial movement down the lateral sides of the back, ready to repeat the whole movement several times.

6. Return to the position required for movement 1 and repeat that movement several times.

7. Using the whole of the length of the thumb and thenar muscle (Fig. 8.7H) push up firmly from the sacrum past the waist level, turning the thumb as the thenar muscle reaches the waist. Take your thumb over to the fingers, then turn your hands towards the sides of the body until your fingertips touch the bed. Do not take your fingers around the body – when the fingertips make contact with the bed allow them to bend as the thenar muscle comes to meet them, making a fist on the bed.

Abdominal massage

Abdominal massage has been well documented since the beginning of the 20th century as a natural method of relieving constipation (Hertz 1909). It is also used on people hospitalized for various reasons, such as the elderly, those with cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s disease and those who are HIV positive etc. (Emly 1993). Movements that follow the peristaltic action of the colon are particularly important.

Stand at the side of the bed and place one hand on top of the other at the top of the patient’s diaphragmatic arch (Fig. 8.8A). Check hands are relaxed and think ‘palm’ when directing the movement.

1. Bring the hands gently down the centre of the body until you can see the patient’s navel at the tips of your fingers (Fig. 8.8B). Turn your fingers outwards (Fig. 8.8C) and take them just under the waist. Lift both hands, keeping full contact and bringing them towards each other downwards (keeping palms down) to the pelvic bone. With your fingers in the original overlapped position, gently slide up the centre of the body to the sternum. Repeat the whole movement several times.

2. With overlapped hands at the right side of the body (Fig. 8.8D), move them slowly and gently in a clockwise circle up the ascending colon, across the transverse colon and down the descending colon several times, finishing where you began.

3. Keeping your hands reinforced and fingers relaxed, make small clockwise circles, in one big circle, with your palms, following the colon as in movement 2 (Fig. 8.8E).

4. Place both hands on the far side of the abdomen (Fig. 8.8F) and perform movement 5 from the back massage above, but gently, with less pressure.

5. Repeat movement 3. For severe constipation, the fingers of the underneath hand may be made into a fist in order to give a slower, more determined stimulus to the colon.

Pregnancy and labour massage

During pregnancy normal massage is encouraged up to the fifth month. As the pregnancy develops, the mother-to-be cannot lie comfortably on her tummy and the following special techniques show how the massage sequences above can be adapted at this stage.

Back massage is possible if the mother-to-be can adopt any of the following positions, whichever she finds most comfortable:

• Semi-prone, often referred to as Sims’ position; on the left (or right) side and chest, the opposite knee and thigh drawn up so that it can rest on the bed, the trailing arm along the back (Fig. 8.9A).

• Sitting on the bed with legs in a squatting position, resting the top half of the body on the backrest plus pillows (Fig. 8.9B).

• Sitting straddled on a chair as suggested for shoulder massage, above.

• Sitting on a stool facing the side of the bed, resting arms and head on a pillow on the bed (Fig. 8.9C).

Leg massage can take place with the patient in a sitting position on the bed, supported by a backrest and pillows.

Abdominal massage should be very gentle and is excellent for calming the baby and relaxing the mother. Raise the upper half of the body with pillows. Movement 1 has been found to be very effective during a contraction (Fern 1992).

Baby massage

For ease, the baby will be referred to as ‘him’ throughout the instructions.

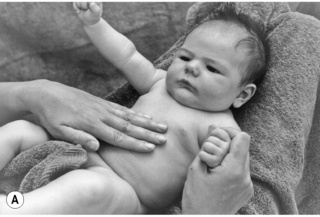

New parents have no difficulty touching, stroking and cuddling their babies and it is a very small step from there to massage. However, as a baby’s skin is delicate and rather ‘loose’, massage has to be gentle. Contact is particularly important for babies, so an excellent way to introduce massage is to sit on the sofa, supporting your back on cushions or pillows (Price & Price 2004). Place a warm soft towel over your abdomen and lay the baby there on his back – head away from you, drawing your knees up towards you to support him. The following movements can also be done on a baby mattress, covered with a warm towel and placed on a table (this is the best way for massaging the baby’s back).

Put a little of the selected blend of oils onto warm hands, gently rubbing them together to distribute and warm the oil blend. Then carry out the following movements.

Tummy

Holding one of the baby’s hands to make him feel secure and prevent him from ‘thrashing’ around (Price & Price 2004), place the fingers of the other hand gently on his tummy and, using as much of the finger lengths as possible, make gentle but firm clockwise circles around his navel (Fig. 8.10A). Repeat several times.

Scalp and forehead

1. Place the fingers of both hands firmly on the baby’s scalp, so that it can be moved gently over the bone beneath (Fig. 8.10B). Move the fingers to a different position and repeat.

2. With fingertips on the baby’s scalp, move the whole length of the thumbs alternately up his forehead several times. Repeat movement 1.

Feet and legs

1. Gently holding the baby’s right thigh with your right hand, place the left hand fingers on top of his foot, and with as much of the length of the thumbs as possible over the sole of his foot, move in slow circles over the middle area (Fig. 8.10C).

2. Hold the baby’s foot with the right hand and move the left thumb in circles from ankle to knee, returning lightly (Fig. 8.10D). Repeat several times.

3. Gently but firmly take the curved lengths of the left fingers from the baby’s ankle to his thigh, covering as much of the outside of his leg as possible in the one stroke, returning lightly underneath (Fig. 8.10E). Repeat several times.

5. Repeat movements 1–4 on the other foot and leg, reversing the handhold used.

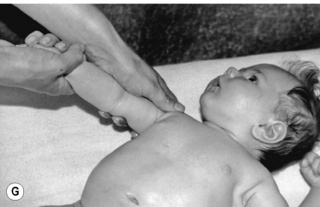

Hands and arms

1. Placing the fingers of both hands on the back of the baby’s hand, place your right thumb over his fingers and make circles on his palm with your left thumb (Fig. 8.10F).

2. Holding his hand with your right hand, take your left hand gently but firmly up his arm to the shoulder and around it, returning very lightly on the back of his arm (Fig. 8.10G). Repeat several times.

Repeat both movements on the other hand and arm, reversing the handhold used.

Back

The back is easier to do on a baby mattress (see above).

1. With fingers and thumbs making a triangle (Fig. 8.10H), move the whole finger length up baby’s back, using as much of the hands as possible to ‘cuddle’ round his shoulders, before returning very gently down the sides of his body. Repeat 4–5 times.

2. Place your hands around the sides of the baby’s body, with one thumb on each buttock. Making large circles with the flat of the thumbs and move slowly and progressively up his back, with slight pressure on the upward half of each circle. On reaching the shoulders (Fig. 8.10I), take the thumbs right round them, returning very gently down the sides of his body. Repeat 3–4 times.

Swiss reflex treatment

This technique was devised by Shirley Price in 1987 while in Switzerland (hence the name), and although it is based on reflex points it differs from reflexology, which is ‘an ancient Eastern technique which makes use of somewhat mysterious connecting pathways or energy flow lines in the body’ (Price 2000 p. 43). These culminate in various areas of the body, occurring in the feet, hands, ears and tongue, where reflexes representing every part of the body can be found. Foot reflex points can be used as a diagnostic aid; furthermore, massaging the relevant points with essential oils can treat the body via the energy flow lines. As with any therapy, an accredited training is necessary to understand the position, significance and connection between the bodily systems and reflex points.

Prior to treatment, the therapist must either be aware of the patient’s problem areas or test each reflex for a reaction.

In a Swiss reflex treatment (SRT), reflexes specific to the patient’s health are massaged, together with a precise dialogue between therapist and client. A bland cream base is used, to which are added essential oils selected by the same method as for an aromatherapy massage. The ratio of essential oil to cream is a minimum of 30 drops to 30 mL, as such a tiny amount is used. The treatment is much simpler to learn than the techniques involved in reflexology, although knowledge of the location of the representative reflexes is of primary importance before treatment can be carried out successfully. As with all practical subjects, attending a practical course is the best way to learn. However, the basic principles are described below.

SRT involves special client participation, including daily self-treatment (or treatment by partner or carer) at home. Without daily treatment, the results are approximately the same as in reflexology or normal massage; however, with daily SRT, positive results are gained much more quickly. Therapists trained in this method by the author before her business passed into other hands – and present students of the Penny Price Academy of Aromatherapy (see Useful addresses, p. 528) – have had some extraordinarily positive results (see Case Studies 8.4, 8.5).

Method of treatment

Having determined which reflexes are in need of treatment, always begin with the solar plexus reflex area (Fig. 8.11A) and finish on the kidney–bladder area (Fig. 8.11B).

1. Apply a very small amount of cream all over the dorsum and sole of the right foot.

Client assessment

Mrs U, 58, had just recovered from a second attempt at a hip replacement, the healing of which was helped considerably by aromatherapy. Now, she was to undergo an operation to fuse her cervical vertebrae on account of the severe arthritic pain there. She was very anxious about this, as due to the death of her husband she needed to be able to continue driving. She wore a surgical collar, which she hated.

Intervention

Mrs U was given a Swiss reflex treatment using the following essential oils, added to a 30 mL jar of bland, non-greasy Swiss reflex cream base:

She was then shown how to massage the same areas herself at home every day, and given the jar of reflex cream.

At the second visit 2 weeks later no improvement had been made, and it was discovered that the client had been massaging the wrong reflex! This experience indicates the importance of giving the client a marked chart, illustrating exactly not only the sequence of the treatment but also the reflex points to be massaged (on this occasion it had been forgotten!).

Two weeks later, Mrs U was experiencing somewhat less pain and a slight improvement in neck mobility. The improvement continued over the next 2 weeks and at the fourth appointment she arrived smiling – wearing a collar homemade from firm foam sponge wrapped in a pretty scarf.

Outcome

Six weeks later, with only self-treatment and a visit every 2 weeks to confirm all was progressing well, she arrived without even the silk-wrapped foam collar. She had had her appointment with the consultant prior to the operation and he was so amazed at the change in her mobility and the lack of pain that he told her the operation would not now be necessary. He asked her what she had been doing, but unfortunately Mrs U was too embarrassed to say she had been rubbing her big toe!

Case study 8.5 Mining accident

Client assessment

Frank had been in a mining accident 19 years previously. A roof beam had fallen on his shoulder, which was damaged, causing a rib to be broken which had pierced his lung. Apart from being unable to move his arm away from his side, he was having breathing difficulties and when walking could only move his feet 15–17 cm at a time.

He had been under a consultant for the whole 19 years and was becoming progressively worse, rather than better. His wife had heard Shirley Price speaking on the radio about aromatherapy and decided to try this treatment for Frank.

Intervention

When they arrived, it was obvious that an aromatherapy body massage would not be possible – the answer had to be Swiss reflex treatment.

This was given to him twice a week for the first week, once a week for 2 further weeks, once a fortnight for the next month, then once a month and eventually once every 2 or 3 months. The oils selected for Frank, in 30 mL of the bland reflex cream base, were:

Frank’s wife was taught how to do the daily treatment and they returned in 4 days to check she was doing it correctly – which she was.

After 6 weeks it was obvious she had never missed a day, as Frank could raise his right arm about 10 cm; after another 2 months this had not only increased to 30 cm, but his shoulders and head were halfway to being erect and his feet were able to take steps of around 26–30 cm.

2. Carry out foot movements 1 (but up to the ankle only) and 2 several times to warm the foot, then wrap in a towel.

3. Repeat these two movements on the left foot and wrap in a towel.

4. Place the palm of the left hand over the toes of the right foot and begin by massaging the solar plexus reflex area in a circular motion with the whole of the length of your right thumb (Fig. 8.11A) – as firmly as the individual patient will tolerante (if the patient is highly stressed, even gentle stroking will seem painful). The pressure should be just such that the patient feels slight discomfort (‘pain’). Maintain this same pressure – and circling – until the client is able to tell you that the ‘pain’ is no longer evident. If the discomfort is still present after 1 minute, the original pressure was probably too strong and the movement should be repeated with just enough pressure to take the patient to his/her lowest pain threshold.

5. Using the same method as in movement 4, massage any reflex area of which the representative organ is presenting a problem to the patient, e.g. lung area for bronchial problems, digestive system area for constipation (concentrating on the large intestine reflex areas, in a clockwise direction), spinal areas for rheumatism or arthritis (in three small sections if the whole spine is affected). Change your hand positions when necessary.

6. Placing your right hand across your body over the patient’s toes, massage with the side length of the thumb in a firm circle, from kidney to ureter to bladder (Fig. 8.11B), relaxing the pressure on the return half of the circle.

7. Repeat movements 2 and 3 and rewrap in the towel.

8. Repeat movements 2–7 on the left foot, reversing ‘right’ and ‘left’ in the text.

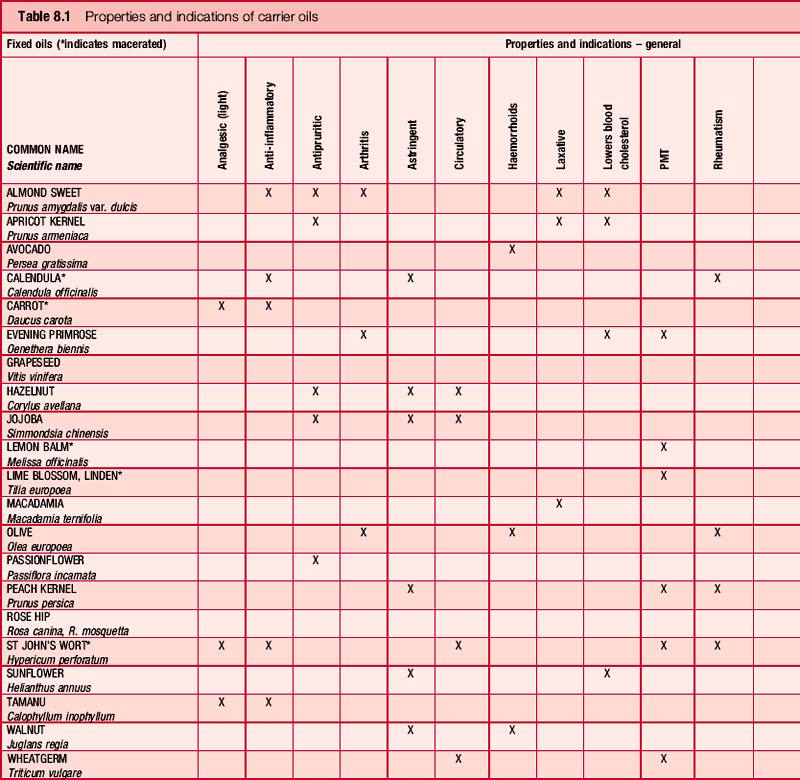

Carrier oils

Vegetable carrier oils constitute the bulk of the material used in an aromatherapy massage. Their function is to ‘carry’ or act as a vehicle for administering the essential oils to the body, and also as lubricants, to make massage movements possible. This section briefly discusses the nature of carrier oils, and details the properties and applications of those more frequently used in aromatherapy.

Fixed oils

Carrier oils are also known as fixed oils, because they do not evaporate, in contrast to the volatile plant essential oils, which do. Fixed carrier oils constitute a different chemical family from essential oils, which is why their properties are so different. Because of their lubricating quality and non-volatile nature they leave a permanent oily mark on paper; essential oils do not leave an oily mark, although any colour present will leave a stain. All essential oils dissolve easily and completely in fixed oils in all proportions.

Chemically speaking, carrier oils are classed as lipids, which are a diverse family of compounds found naturally in plants and animals. Oils and fats have similar structures, but at room temperature (15°C) fats are solid and oils are liquid. For the detailed chemistry of carrier oils, see Carrier Oilsfor Aromatherapy and Massage (Price & Price 2008).

Vegetable oils contain a high level of unsaturated fatty acid units (>80%), which is why they are important for our health. The double bonds are less strong than single bonds and introduce an element of weakness into a compound. Once opened up they can absorb other molecules for transportation elsewhere in the body, and can also facilitate the natural digestive breakdown of the triacylglycerols. Oils with a high degree of unsaturation are less stable than those that are highly saturated, owing to the weakness of the double bonds; thus they are open to attack by oxygen and moisture, which can lead to breakdown and rancidity.

Cold-pressed oils

Carrier oils used in aromatherapy should, wherever possible, be cold pressed, although this term is a slight misnomer as the extraction process generates a certain amount of heat – and cooling is normally required. Temperatures are usually maintained below 60°C, and in this way changes to the natural characteristics of the oil are kept to a minimum.

Vegetable oils may be refined to meet the particular requirements of large-scale users such as the pharmaceutical industry, cooking oil manufacturers, food processors and cosmetics companies. Processing here frequently involves the use of high temperatures and chemicals, when many of the natural properties of the oil are lost, its character is altered and its use in aromatherapy is not desirable. This is the type of oil usually found on supermarket shelves.

Mineral oils are high molecular weight hydrocarbons, with very different properties from those of vegetable oils. They are oily and greasy, with a tendency to clog the pores, and are less able to be absorbed by the skin: because of this unsuitability they are not normally used in aromatherapy.

Types of carrier oil

There are three broad categories:

• Basic oils. These can be used with or without essential oils for body massage and are generally pale in colour, not too viscous, and have very little smell. They include sweet almond, apricot kernel, peach kernel (see page 193), grapeseed and sunflower.

• Special oils. These tend to be more viscous, heavier and more expensive. They include avocado, sesame, rose hip and wheatgerm. The extra-rich oils such as avocado and wheatgerm are seldom, if ever, used on their own: it is more normal to use them as 10–25% of a carrier oil blend.

• Macerated oils. As these have certain additional properties to the oils above, because of the way they are produced, they can be used on their own, although it is preferable to add one or two drops of appropriate essential oils to increase the effect on health conditions. Chopped plant material is added to a selected fixed oil (mostly sunflower or olive), agitated gently for some time, then left for some weeks before filtering. All the plant’s oil-soluble compounds (including any essential oil compounds that may be present) are transferred to the carrier oil, giving them extra therapeutic effects.

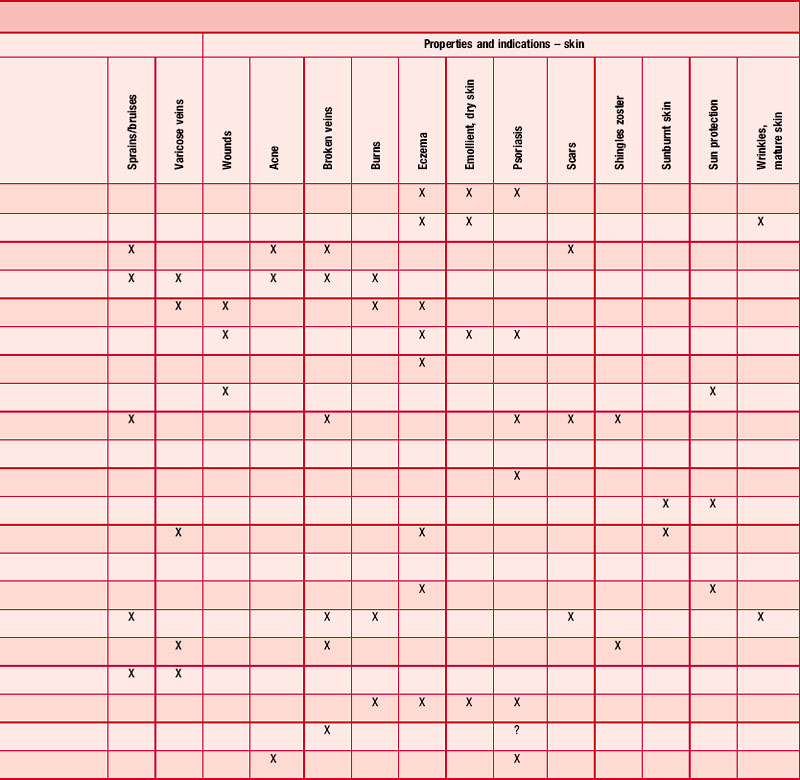

There are more than 20 suitable carrier oils available (Price & Price 2008) – a small selection is detailed below. Table 8.1 gives a more complete list, including particular properties and indications for each.

Basic oils

Almond sweet (Prunus amygdalis var. dulcis)

Sweet almond oil is one of the most-used carrier oils; pale yellow in colour, it is slightly viscous and very oily. Apricot kernel (P. armeniaca) and peach kernel (P. persica) oils are very similar – it can be very difficult to discriminate between them. Their advantage over some other base oils is that they have less tendency to become rancid. The unrefined oil has a delicate, sweet smell and a flavour with a hint of marzipan. Sweet almond oil is used in laxative preparations and is said to be effective in reducing blood cholesterol levels (Leung & Foster 1996). It is an excellent emollient and nourishes dry skin; it also helps to soothe inflammation (Stier 1990). Almond oil is beneficial in relieving the itching caused by eczema, psoriasis, dermatitis and all cases of dry scaly skin, and is absorbed slowly through the intact skin (Expert Panel 1983 p. 97). It is said to be non-irritant, non-sensitizing and safe for cosmetic use (Leung & Foster 1996), but a few people are allergic to cosmetics containing almond oil, suffering a stuffy nose and skin rash (Winter 1999 p. 88).

Grapeseed (Vitis vinifera)

Grape seeds cannot be cold pressed and the oil is produced commercially by hot extraction. If it can be ‘rescued’ before it is refined, it is suitable for aromatherapy as refining includes chemical processing. The oil is tasteless, almost odourless, and as it is very fine it is also used to lubricate watches. It is a gentle emollient and leaves the skin with a smooth satin finish without feeling greasy.

Sunflower (Helianthus annuus)

Much of the sunflower oil available commercially has been obtained by solvent extraction, so care must be taken to ensure that only cold-pressed oil, which is also available, is used in aromatherapy. Sunflower oil has slight diuretic properties; it is said to aid cholesterol metabolism and may be used to counteract arteriosclerosis (Stier 1990). It is expectorant and, as it contains inulin, it may be useful in the treatment of asthma. The oil is beneficial for skin complaints and bruises, and is effective on leg ulcers. It has been reported as being efficacious in the treatment of multiple sclerosis (Anon 1990, Millar et al. 1973, Swank & Dugan 1990).

Special oils

Avocado oil (Persea gratissima, Persea americana) Lauraceae

True cold-pressed avocado oil (from the dried fruits) is a deep green colour and is comparatively rare. It keeps well but should not be chilled, as some useful parts of the oil would precipitate – it solidifies at 0°C. Occasionally it has a slightly cloudy appearance, occasionally with sediment, which can indicate that it has not been subjected to extensive refining. Refined avocado oil, used by the cosmetics industry, is bleached, leaving it pale yellow to colourless; it is widely available but should not be used therapeutically for obvious reasons.

Avocado oil is a good, penetrating emollient, useful for massage, where 10–25% is used in a base carrier oil. It is valuable in muscle preparations, has skin healing (Leung & Foster 1996 p. 54), moisturizing, and anti-wrinkle properties, and is recommended for dry skins. It has been used in Raynaud’s disease (Stier 1990 p. 54). As far as is known, avocado oil is non-irritant and non-sensitizing (Winter 1999 p. 73). The ingested pressed oil is said to be helpful in constipation, liver and gallbladder problems and urinary infections (Price & Price 2008 p. 57 p. 40).

Evening primrose oil (Oenothera biennis, O. glazioviana, O. nagraceae)

Evening primrose oil, pressed from the seeds, includes 10% γ-linolenic acid (GLA), which is comparatively rare. This highly unsaturated oil is more reactive and less stable than most other oils. It oxidizes on exposure to air and light and is sensitive also to heat and humidity, therefore it should be stored in a cool, dark place. It is thought to be beneficial in the treatment of atopic eczema (Kerscher & Korting 1992, Lovell 1981), although this is contested by Berth-Jones and Graham-Brown (1993). It is known to be useful in the treatment of dry, scaly skin (Price & Price 2008 p. 100) and to benefit sufferers of psoriasis (Ferrando 1986). The oil improves dandruff conditions and accelerates wound healing (Price & Price 2008 p. 100); for cosmetic use it is incorporated in anti-wrinkle preparations. Borage oil is sometimes added to increase the level of GLA. When ingested, evening primrose oil is said to control arthritis (Lovell 1981) and Horrobin (1983) claims it is helpful to PMS, though Collins et al. (1993) repudiate this claim.

Jojoba oil (Simmondsia chinensis, Buxus chinensis)

Jojoba oil is in fact a wax, not an oil; the seeds produce a liquid wax which does not become rancid, giving it a long shelf-life (it will solidify if stored in a refrigerator). It is very stable (indigestible to bacteria), so preservatives (often the cause of allergies or skin irritations) are not necessary. Jojoba contains the anti-inflammatory agent myristic acid, making it beneficial for arthritis and rheumatism. It is particularly useful in cases of acne, as its molecular structure is similar to that of sebum, and it is used to control the build-up of excessive sebum (Anon 1983). It is also used for nappy rash and chapped skin (Bartram 1996 p. 258), psoriasis, sunburn and eczema. Jojoba oil may cause an allergic reaction (Winter 1999 p. 265), and contact dermatitis has also been reported (Scott & Scott 1982).

Peach kernel oil (Prunus persica)

This oil, usually cold pressed, is chemically and physically similar to almond and apricot kernel oils, albeit more expensive, as it is not produced in large quantities. It is emollient and nourishing, so is beneficial for dry, sensitive and ageing skins. It is reputed to relieve itching and help eczema (Price & Price 2008 p. 151). The oil is often used in the cosmetic industry as a substitute for almond oil (Wren 1975) in facial massage oils and skin care creams. Culpeper (1616–1684) tells us that the oil brings rest and sleep when applied to the forehead, and when ingested it is said to relieve constipation and high blood cholesterol (Price & Price 2008 p. 151).

Rose hip (Rosa mosquetta, R. rubiginosa)

Rose hip oil, taken from the seeds within, is a golden-red colour and contains significant amounts of vitamin C. It also contains small quantities of trans-retinoic acid, which contribute to its therapeutic properties. Studies in Chile have identified that the oil is a tissue regenerator and has an effect on the skin to minimize premature ageing and wrinkles, as well as reducing scar tissue. It is helpful on wounds, burns and eczema.

Wheatgerm (Triticum vulgare)

Wheatgerm is a rich orange-brown colour and very viscous. It is seldom used on its own, being commonly employed as 10–25% of the carrier oil mix. Because of its high content of vitamin E, a natural antioxidant, it is added to less stable oils to increase their useful life. The oil is rich in lipid-soluble vitamins and so is good for revitalizing dry skin. It is also said to be useful on ageing skin, where its natural antioxidants are an effective weapon against free radicals. The oil is beneficial for tired muscles and should be included in the mix for after-sports massage.

Macerated oils

Calendula (Calendula officinalis)

Calendula oil is obtained by macerating chopped plant material in sunflower oil, and the normal orange-yellow colour of the calendula flowers is reflected in the colour of the oil. Although calendula is sometimes referred to as ‘marigold’ it is a very different plant from Tagetes patula and Tagetes minuta [tagetes, French marigold], which are also known as marigold. Calendula extracts have been used to promote healing and reduce inflammation (Fleischner 1985), and it is most effective on broken veins, varicose veins, bruises etc. Calendula is specifically indicated for enlarged or inflamed lymph nodes, sebaceous cysts and acute or chronic skin lesions (Casley-Smith & Casley-Smith 1983).

St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum)

This plant is usually macerated in olive oil, the resulting oil being a deep red colour, owing to the presence of hypericin. An anti-inflammatory oil, hypericum is useful on wounds where there is nerve tissue damage and also for inflamed nerve conditions, hence it is used in cases of neuralgia, sciatica and fibrositis. A 20% hypericum tincture has been used in the treatment of suppurative otitis, and extracts are stated to have been used clinically in Russia to treat infection (Shaparenko et al. 1979). The use of hypericum in the treatment of vitiligo (Newall, Anderson & Phillipson 1996) has also been reported, as has its use as an astringent and diuretic (Martindale 1993). Hypericin, the red pigment, is being studied as a possible antiviral agent in the management of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (Abrams 1990, Anon 1991).

Summary

Touch and massage have profound benefits, not only for the recipient but also for the therapist, and its recent neglect in official healthcare is slowly beginning to be remedied. This chapter has identified the main benefits, as well as the contraindications. It has also provided a basic grounding in simple massage techniques, and suggested some of the more useful massage sequences. Carrier oils comprise the major part of any blend used in an aromatherapy massage and should be selected with care, to augment the effects of essential oils on presenting symptoms.

Abrams D.I. Alternative therapies in HIV infection. AIDS. 1990;4:1179-1187.

Anon. Botanicals in cosmetics. Jojoba: a botanical with a proven functionality. Cosmetics and Toiletries. 1983;98:81-82.

Anon. Lipids and multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1990;336:25-26.

Anon. Treating AIDS with worts. Science. 1991;254:522.

Auckett A.D. Baby massage. New York: Newmarket press; 1981.

Barlow J., Cullen L. Increasing touch between parents and children with disabilities: preliminary results from a new programme. J. Fam. Health Care. 2002;12(1):7-9.

Bartram T. Encyclopedia of herbal medicine. Christchurch: Grace; 1996:258.

Beard G., Wood E.C. Massage – principles and techniques. London: Saunders; 1964.

Berth-Jones J., Graham-Brown R.A.C. Placebo controlled trial of essential fatty acid supplementation in atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 1993;341:1557-1560.

Buckle. Clinical aromatherapy in nursing. London: Arnold; 1997.

Casley-Smith J.R., Casley-Smith J.R. The effect of Unguentum lymphaticum on acute experimental lymphedema and other high-protein edemas. Lymphology. 1983;16:150-156.

Chaitow L. Field T., editor, Touch therapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:vii.

Collins A., Coleman G., Landgren B.M. Essential fatty acids in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Obstet. Gynaecol.. 1993;81:93-98.

Culpeper, undated. Culpeper’s complete herbal. Foulsham, Exeter, p. 262

Emly M. Abdominal massage. Nurs. Times. 1993;89(3):34-36.

Expert Panel. Cosmetic ingredient review: 4: Final report on the safety of sweet almond oil and almond meal. J. Am. Coll. Toxicol.. 1983;2(5):85-99.

Fern E. Directorate of Maternity and Gynaecology. Practice Group (Midwifery, Gynaecology and Neonatal Care) Aromatherapy. 1992. Midwifery Procedure no. 23, Ipswich Hospital

Ferrando J. Clinical trial of topical preparation containing urea, sunflower oil, evening primrose oil, wheatgerm oil and sodium pyruvate in several hyperkeratotic skin conditions. Med. Cutan. Ibero Lat. Am.. 1986;14(2):132-137.

Field T. Touch therapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Field T., Scafidi F., Schanberg S. Massage of preterm newborns to improve growth and development. Paediatr. Nurs.. 1987;13:385-387.

Fleischner A.M. Plant extracts: to accelerate healing and reduce inflammation. Cosmetics and Toiletries. 1985;100:45.

Hertz A.F. Constipation and internal disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1909.

Horrigan C. Complementing cancer care. Int. J. Aromather.. 1991;3(4):15-17.

Horrobin D.F. The role of essential fatty acids and prostaglandins in the premenstrual syndrome. J. Reprod. Med.. 1983;28:465-468.

Kerscher M.J., Korting H.C. Treatment of atopic eeczema with evening primrose oil. Lancet. 1992;1(8214):278.

Leung A.Y., Foster S. Encyclopedia of common natural ingredients. New York: Wiley; 1996.

Lovell C.R. Plants and the skin. London: Blackwell; 1981:255.

Martindale. The extra pharmacopoeia. thirtieth ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 1993:1378.3.

Maxwell-Hudson C. Aromatherapy massage. New York: Dorling Kindersley; 1999:41.

Mennell J.B. Physical treatment, fifth ed. Philadelphia: Blakiston; 1945.

Millar J.H.D., Zilkha K.J., Langman M.J.S., Payling Wright H., Smith A.D., Belin J., et al. Double blind trial of linoleate supplementation of the diet in multiple sclerosis. Br. Med. J.. 1973;1(5856):765-768.

Newall C.A., Anderson L.A., Phillipson J.D. Herbal medicines. London: The Pharmaceutical Press; 1996:251.

Price S. Practical aromatherapy. How to use essential oils to restore health and vitality. fourth ed. London: Thorsons; 1999.

Price S. The aromatherapy workbook, second ed. London: Thorsons; 2000.

Price S., Price P. Aromatherapy for babies and children, second ed. Stratford upon Avon: Riverhead; 2004.

Price L., Price S. Carrier oils for aromatherapy and massage, fourth ed. Stratford upon Avon: Riverhead; 2008.

Sanderson H., Harrison J., Price S. Aromatherapy and massage for people with learning difficulties. Birmingham: Hands On; 1991.

Scott M.J., Scott M.J.Jr. Jojoba oil (Letter). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.. 1982.

Shaparenko B.A., Slivko B.A., Bazarova O.V., Vishnevetskaya E.N., Selesneva G.T., Berezhnala L.P. On the use of medicinal plants for treatment of patients with chronic suppurative otitis. Zh. Ushn. Nos. Gorl. Bolezn.. 1979;39(3):48-51.

Stier B. Secrets des huiles de première pression à froid. Quebec: Self published; 1990.

Swank R.L., Dugan B.B. Effect of low saturated fat diet in early and late cases of multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1990;336:37-39.