Skin cancer – Malignant melanoma

Malignant melanoma is a malignant tumour of melanocytes, usually arising in the epidermis. It is the most lethal of the main skin tumours and has increased in incidence over the last three decades. The important pathogenic role of excessive ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure has been the subject of public education campaigns. Genetics may be important, and up to 5% of patients have a family history of malignant melanoma.

Clinical presentation

Four main clinicopathological variants are recognized. These are described below.

Superficial spreading malignant melanoma

This type accounts for 50% of all British cases, shows a female preponderance and is commonest on the lower leg. The tumour is macular and shows variable pigmentation, often with regression (Fig. 1).

Lentigo malignant melanoma

Malignant melanoma developing in a longstanding lentigo maligna (Fig. 2) constitutes 15% of UK cases. A lentigo maligna arises in sun-damaged skin, often on the face of an elderly person who has spent many years in an outdoor occupation.

Acral lentiginous malignant melanoma

The acral lentiginous type makes up 1 in 10 of British cases, but is the commonest form in dark-skinned races. The tumour affects the palms, soles (Fig. 3) and nail beds, is often diagnosed late and has poor survival figures.

Nodular malignant melanoma

The nodular variant is seen in 25% of British patients; it shows a male preponderance and is commonest on the trunk. The pigmented nodule (Fig. 4) may grow rapidly and ulcerate.

Epidemiology

Malignant melanoma has an incidence in the UK of 15–20 per 100 000 population per year. The incidence has been rising at 7% each year and has trebled in the last two decades. In the UK, women are affected twice as frequently as men. Superficial spreading and nodular melanomas tend to occur in those in the 20–60-year age group, whereas lentigo malignant melanomas mostly affect those over 60 years old. In males, the commonest site is the back; in females, it is the lower leg (about half occur here).

Staging

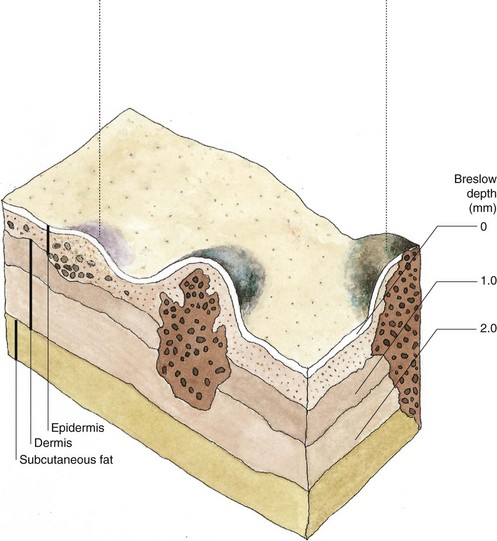

Malignant melanomas usually progress through two phases: horizontal growth in the epidermis then vertical invasion of the dermis (Fig. 5).

Local invasion by the tumour is assessed using the Breslow method, which is the measurement in millimetres of the distance between the granular cell layer to the deepest identifiable melanoma cell. Metastasis is uncommon in tumours restricted to the epidermis.

Aetiopathogenesis

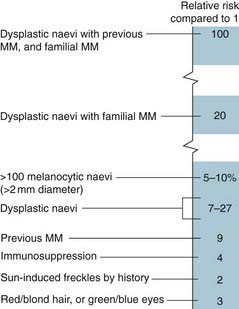

The main risk factor that increases risk of melanoma is exposure to UV radiation. Some people are more at risk of melanoma than others (Fig. 6). Histological evidence of a pre-existing melanocytic naevus is found in 30% of malignant melanomas but, with the exception of dysplastic or congenital naevi (Fig. 7), the risk of change in a common melanocytic naevus is small.

The major risk factors and their relative risk for the development of malignant melanoma (MM) are shown.

Int J Dermatol. 2010; 49: 362–376.

Fig. 7 Dysplastic naevus syndrome.

This condition, which may be familial, is characterized by large numbers of atypical and ‘dysplastic’ naevi, which are often over 7 mm in diameter with an irregular edge and variable pigmentation. Affected individuals have a greatly increased risk of developing malignant melanoma. They should avoid the sun and be closely observed. Changing or suspicious pigmented lesions should be excised for histological examination.

Diagnosis

Any of the following changes in a naevus or pigmented lesion may suggest malignant melanoma:

Prognosis

The prognosis relates to the tumour depth. The approximate 5-year survival rates are:

Examples of thin and thick tumours are given in Figures 8 and 9.

Management

The primary treatment is narrow surgical excision followed by re-excision of the scar dependent upon Breslow thickness. In situ tumours require a 0.5-cm re-excision, those up to 1 mm thick require a 1-cm margin, those of 1–2 mm thickness need a 2-cm margin and thicker tumours require a 2–3-cm clearance. A skin graft may be necessary to close the defect. Regular follow-up is needed to detect any recurrence, of which there are three main types:

1. local (Fig. 10)

2. lymphatic – either in the regional lymph nodes or in transit in the lymphatics draining from the tumour to the nodes

Fig. 10 Hypomelanotic recurrent malignant melanoma.

Pink papules of recurrent tumour are evident at the edge of a previously excised and grafted site.

Routine sentinel node biopsy (p. 115) or elective lymph node dissection is not recommended as a standard procedure at present. Radiotherapy is of limited use. Interferon-alpha may increase survival in patients with tumours more than 1.5 mm thick. For metastatic disease, chemotherapy with dacarbazine is the current standard but has limited effectiveness and significant toxicity. New therapies including ipilimumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the negative T cell regulator molecule, CTLA-4, has been shown to improve survival in advanced melanoma, and BRAF kinase inhibitors in BRAF mutated melanomas have shown promise.

Prevention and public education

Early malignant melanoma is a curable disease, but thick lesions have a poor prognosis. Public health education should encourage early visits to the doctor for changing pigmented lesions and should discourage excessive sun exposure, especially in fair-skinned individuals or those with numerous melanocytic naevi. The best advice is:

Malignant melanoma

The UK incidence is 15–20 per 100 000 per year.

The UK incidence is 15–20 per 100 000 per year.

The female to male ratio is 2 : 1.

The female to male ratio is 2 : 1.

The incidence has risen by 7% per year and doubled in the past two decades.

The incidence has risen by 7% per year and doubled in the past two decades.

The incidence is proportional to the geographical latitude, suggesting an effect of ultraviolet radiation.

The incidence is proportional to the geographical latitude, suggesting an effect of ultraviolet radiation.

The prognosis is related to tumour thickness. Early lesions are curable by surgical excision.

The prognosis is related to tumour thickness. Early lesions are curable by surgical excision.