CHAPTER 4 Communication and Behavioral Change Theories

BACKGROUND

Effective communication with the client is essential for providing optimal dental hygiene care. For example, during the assessment phase of the dental hygiene process the hygienist needs to communicate effectively with the client to obtain and validate information concerning medical, dental, and personal and social histories and oral health status and behaviors. Communication skills also influence client adherence to preventive and therapeutic recommendations. When rapport, confidence, and trust are present, a client is more likely to share confidential information and to follow specific oral healthcare recommendations. If dental hygienists possess technical skills and knowledge but are unable to communicate effectively with clients, they may fail to reach important goals related to client oral health, comfort, and long-term behavioral change.

BASIC ELEMENTS OF THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

Sender, Message, and Receiver

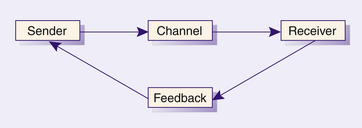

Interpersonal communication is the process by which a person sends a message to another person with the intention of evoking a response. Basic communication elements1 are shown in Figure 4-1. The sender is the person who constructs a message to initiate the interpersonal communication. The message construction process is known as encoding. The message itself contains information the sender wishes to transmit. It must be in a format of symbols that are understandable to the other person. It should be clearly organized and well expressed and may be composed of both verbal and nonverbal content. The message is sent via a channel that involves visual, auditory, and tactile senses. For example, facial expression uses a visual channel, spoken words use an auditory channel, and touch uses a tactile channel. The receiver is the person who accepts the message and deciphers its meaning, a process known as decoding. The receiver must share a common language with the sender to decode the message accurately. Communication is most effective when the receiver and the sender accurately perceive the meaning of each other’s messages.

Feedback

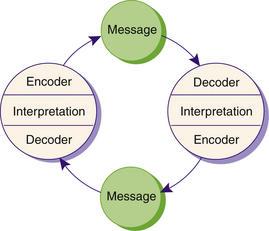

Communication does not generally stop with one encoded and decoded message. The receiver is prompted to respond and provides a feedback message. The receiver then becomes the sender and the cycle repeats itself. The feedback communication model illustrates how each person has an encoding and a decoding role in the communication process (Figure 4-2). In a social situation, both persons assume equal responsibilities to seek openness and clarification. In the dental hygienist–client relationship, however, the dental hygienist assumes primary responsibility. Dental hygienists need to seek verbal and nonverbal feedback to make sure good communication has occurred. Message transmission is influenced by the sender’s and receiver’s physical and developmental status, perceptions, values, emotions, knowledge, sociocultural background, roles, and environment.

FACTORS THAT AFFECT INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION

Many contextual factors influence interpersonal communication (Box 4-1) and can affect interpretation of the message as discussed in the following sections.1

BOX 4-1 Contextual Factors Influencing Communication

Adapted from Potter PA, Perry AG: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 7, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.

Environmental Factors

The physical surroundings in which communication takes place influence the communication process. For example, people are more likely to communicate effectively in an environment that is comfortable. Factors such as lighting, heating, ventilation, and acoustics may affect the communication process. In the oral healthcare setting, confidentiality may be important if clients are revealing sensitive information about their health. A bustling environment may pose annoying distractions that could block communication.

Internal and Relationship Factors

A person’s perceptions, knowledge, values, emotions, and level of need fulfillment influence the way messages are sent and received.1

Perceptions

Perceptions can vary greatly from person to person. One individual’s analysis of a situation may differ entirely from another’s, even though all basic elements are the same. As an example, it is possible for a dental hygienist to take a very aggressive approach to oral health education. The hygienist may communicate strong demands for client response and loud, clear warnings about the progression of disease if recommendations are not followed. Some clients may perceive the dental hygienist as an authority figure they can respect and respond to very favorably. Others, however, may be offended, perceive the dental hygienist as “pushy” and judgmental, and have a generally adverse reaction to the hygienist’s attempts to influence their behavior or health.

Perceptions are formed based on past experience and are difficult to change. If clients had previous contact with a dental hygienist who communicated respect and warmth, they would be more likely to respond well to the hygienist’s attempt to resolve a health issue that has become more pressing. When a hygienist takes an aggressive stance with a new client, however, the risk of blocked communication from the client’s negative perception of the dental hygienist is great.

Values

Values are personal beliefs that may have moral and ethical implications. Whatever we consider important in our lives influences the way we communicate our ideas and feelings. Each individual has a unique set of values that has been shaped by personal experiences. The hygienist can influence the communication process by exercising tolerance for and understanding of the wide differences of opinion that exist.

Not all clients value oral health. Individuals have reasons, both known and unknown, for holding their respective values. A person from an impoverished background may have to prioritize values to survive. Oral health and education may not be highly valued when food, shelter, and clothing are not readily available. On high school campuses, a sugar-free diet may not be valued when candy and soft-drink machines beckon. Water fluoridation may not be valued by people who have been deluged with information from antifluoridationists.

Values can be changed, but experts suggest that they are slow to form and to change. For value change to occur in the oral healthcare environment,1 oral healthcare professionals must do the following:

Be aware of their own values and how they affect the choices they make in planning and implementing oral health behavioral change programs

Be aware of their own values and how they affect the choices they make in planning and implementing oral health behavioral change programsSometimes client values related to oral health and disease can be changed by education. The methods used to produce change and the degree of success are dependent on how wide the gap is between the desired value and the client’s current value.

Emotions

Do not underestimate the influence of emotions in everyday communication. Emotions are strong feelings people have about other people, places, and things in their environment. Fear, wonder, love, sorrow, and shame are examples of strong human emotions that touch all individuals at some time in their lives.

Hygienists who are empathetic may become emotionally involved in their clients’ lives. Dental hygiene clients may have serious general health problems that are causing them grief and suffering. The hygienist needs to be compassionate but must act professionally throughout the process of care.

In contrast, emotions that are rooted in the hygienist’s own personal life should not interfere with client care. For example, Scenario 4-1 is an interesting hypothetic situation.1

A young hygienist had an argument with her husband before coming to work. Her husband is just out of law school and establishing his practice. The hygienist’s income is needed for the family’s survival. Her husband has proposed that they begin having children. The hygienist knows that she and her husband would have difficulty rearing a family now, particularly because she would soon have to take a leave from work.

The hygienist goes to work angered by her husband’s lack of understanding. The first client she sees is a 24-year-old mother of three who is divorced and living on welfare. The hygienist cannot allow herself to transfer her anger at her husband to the client’s situation. This transfer would prevent her from understanding this client as an individual. If the hygienist is to communicate effectively with the client, she must be aware of her emotions.

Knowledge

Communication can be hindered when knowledge levels differ between the participants. Dental hygiene clients may be highly educated but have an expertise area outside the realm of oral health. A highly technical vocabulary is inappropriate with a client unless terms are carefully explained. Most clients have no need to distinguish between the mesials and distals of their teeth. This terminology, however, is essential in professional communication and is commonplace for members of the oral healthcare team. If the dental hygienist uses language the client cannot understand, or “talks down” to the client, the hygienist loses that client’s attention and cooperation and lessens the chances that goals will be achieved. The effective dental hygienist monitors client feedback to guide the appropriate level of language usage.

FORMS OF COMMUNICATION

Interpersonal communication is never static, but rather is a dynamic, ongoing process. Messages may be verbal or nonverbal. In nonprofessional communication people rarely analyze the meaning of every gesture or word. In the professional role, however, the dental hygienist must use critical thinking to focus on each aspect of communication to ensure that interactions are purposeful and effective.

Verbal Communication

Using the spoken word to convey a message is verbal communication. The most important aspects of verbal communication are vocabulary, intonation, clarity, and brevity.1

Vocabulary

For communication to be successful, sender and receiver must be able to translate each other’s words. Dental jargon sounds like a foreign language to most clients and is to be used only with other oral healthcare professionals. Technical terms need to be simplified to an appropriate level to enable clients to know what the dental hygienist is saying. If clients do not understand, they often will tune out and a total breakdown of communication will result. By using simple, common language devoid of all superfluous terminology, the hygienist will be easily understood and is more likely to send accurate, straightforward, meaningful information. When dental hygienists provide care to clients who speak a different language, an interpreter usually is needed.

Intonation

Intonation is the modulation of the voice. The whisper of confidentiality, the rising crescendo of anger, and the dull tones of despair are examples of how tone of voice dramatically affect’s a message’s meaning.2 The dental hygienist needs to be aware of voice tone to avoid sending unintended messages. Moreover, clients’ voice tone often provides valuable information about their emotional state.

Clarity

Communication is enhanced when messages sent are simple, brief, and direct. Speaking slowly, enunciating clearly, providing examples to make explanations easier to understand, and repeating the most important part of the message all help to achieve clarity. Using short sentences and familiar words to express ideas simply enhances clarity. For example, asking “Where is your pain?” is better than saying “Please point out to me the location of your discomfort.”1

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication is the use of body language rather than words to transmit a message. Effective nonverbal communication complements and strengthens the message conveyed by verbal communication so that the receiver is less likely to misinterpret the message.

Nonverbal communication includes body movement such as facial expression, eye behavior, gestures, posture and gait, and touch. Because body language is hard to control, it often reveals true feelings. It takes practice, concentration, and sensitivity to others for the dental hygienist to become an astute observer of body language. For example, there probably is something wrong with a client who says she is “fine” but is wringing her hands. Dental hygienists also should be aware of their own body language to avoid sending mixed messages to clients. Saying “It’s good to see you” while wearing a frown does not establish trust and may cause anxiety. To facilitate communication, various aspects of body language are discussed in the following sections.

Facial Expression

The face is the most expressive part of the body. Facial expression often reveals thoughts and feelings and conveys emotions such as anger, fear, sadness, surprise, happiness, and disgust. Clients closely watch the dental hygienist’s facial expression. A dental hygienist may frown when concentrating, and a client may interpret the facial expression as anger or disgust. Although it is hard to control facial expressions, the dental hygienist needs to avoid showing shock or disgust in the client’s presence.

Eye Behavior

Eye behavior can be discussed separately from facial features and body movements, but obviously the messages being sent depend on all behaviors collectively. Generally, in Western culture we are told to make eye contact with people as we speak to them. Eye contact is often made before the first spoken word. Thus it is the first message sent when two people meet. The eye can convey trust, interest, or attention. Eye contact is avoided when we feel uncomfortable and maintained steadily when we are taking an offensive as opposed to a defensive approach to someone.

Along with the forehead and eyebrow muscles, the eyes are extremely expressive. Raising an eyebrow can imply a question. Raising both eyebrows may indicate shock or surprise. Narrowed eyes may suggest skepticism, whereas widely open eyes show amazement.

A dental hygienist works in close proximity to a client’s eyes and should always monitor them for nonverbal messages that convey pain or discomfort. In addition, the dental hygienist’s eyes are likely to be watched by the client for signs of approval, disapproval, kindness, or displeasure. A face mask hides most of the hygienist’s face; therefore eyes become an even more important source of expression and communication.

Gestures

Gesture usually refers to movement of the arms, hands, head, or possibly the whole body. These movements may reveal much about a person’s feelings. For example, a client’s hands clenching the arm of the dental chair is a cue that the client is experiencing pain or stress.

Posture and Gait

Posture and body movement may be considered another category of gesture. The way a person moves can tell us whether that person is comfortable or uncomfortable, bold or timid. A shift in posture can be an indication of a changing emotional state. Movement toward someone suggests trust and liking. Movement away sends a negative message. The speed at which people move can mean something definite. A slow movement suggests uncertainty; a rapid movement can indicate eagerness, playfulness, or possibly impatience. Posture is affected by a person’s size and overall physical appearance. An erect posture and a sharp, snappy step can do much to draw respect to a person of any size.

Touch

Touching is one of the most sensitive means of communication and is most closely related to the human need for freedom from stress. Touch can be reassuring in some contexts. A hand gently placed on a shoulder may mean more to a client than any verbal expression of support. It is important to note, however, that people have different attitudes toward being touched. Some are not accustomed to it and may cringe or pull away as the hygienist attempts to comfort them. Touch needs to be used discriminately to avoid misinterpretation.

The nature of the dental hygiene process of care requires touching clients. The way in which the hygienist touches the client can communicate feelings about the client and the practice of dental hygiene. Rough, jerking movements may send a message of careless indifference, resulting in uncooperative behavior from a client. Accidental touching, such as bumping a person’s nose or hitting his or her front teeth with the mouth mirror, also can carry a negative message such as carelessness or haste. A professional, careful approach to touching is appreciated and respected by clients.

PROFESSIONAL DENTAL HYGIENE RELATIONSHIPS

The dental hygienist applies knowledge, understanding of human needs, communication, and a commitment to ethical behavior to create professional relationships with clients. Having a philosophy based on caring and respect for others helps the dental hygienist to establish helping relationships with clients.

The CARE principle is used as a simple mnemonic or memory-assisting technique to identify aspects of care important to effective dental hygienist–client helping relationships (Box 4-2).

Comfort

Comfort (C in the mnemonic) refers to the hygienist’s ability to deal with embarrassing or emotionally painful topics related to a client’s health; to be aware of the client’s physical and emotional response during dental hygiene care; and to provide verbal support to a client who fears oral healthcare procedures. Aspects of dental hygiene practice related to client comfort and communication include effectively addressing a client’s loss of teeth and need to wear a prosthetic appliance, a client’s inability to seek oral healthcare because of financial difficulties, a client’s fear of injections, and clients’ discomfort from having their personal space “invaded” during care.

Personal space is invisible and travels with a person. Territoriality refers to the need to maintain and defend one’s right to this personal space. During interpersonal communication individuals maintain varying distances between each other depending on their culture, their relationship, and the circumstance. Touching the head and neck area is usually reserved for intimate relationships such as between lovers or a parent and a child. When personal space is violated, people often become defensive and communication becomes ineffective. Because dental hygienists work within the client’s intimate zone of personal space, it is important to convey professional confidence, gentleness, and respect when doing so. Examples of these actions are listed in Box 4-3. To meet the client’s human need for freedom from stress, the hygienist strives to keep the client’s comfort a top priority.

Acceptance

Acceptance refers to the dental hygienist’s ability to accept clients as the people they are without allowing any judgment of the clients’ attitudes or feelings to interfere with communication. For example, a client may appear unwilling to assume responsibility for his or her health and may be critical or untrusting. The client’s poor oral health may seem to be self-imposed and related to an unhealthy lifestyle. But the client’s appearance and attitudes may have deep cultural roots that are unfamiliar to the hygienist. The dental hygienist must develop an attitude of acceptance toward individuals whose values and sociocultural backgrounds seem unusual or foreign.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness in a healthcare provider is the ability to reply to messages at the very moment they are sent. It requires sensitive alertness to cues that something more needs to be said. When a client arrives for a dental hygiene appointment and mentions oral discomfort, the comment should be pursued immediately. Scaling and root planing might have been scheduled, but other problems may be an immediate priority and supersede the planned care.

Empathy

Empathy is said to result when we place ourselves in another’s “shoes.” Empathy means perceiving clients as they see themselves, sensing their hurt or pleasure as they sense it, accepting their feelings, and communicating this understanding of their reality.1

In expressing empathy the dental hygienist communicates understanding the importance of the feelings behind a client’s statements. Empathy statements are neutral and nonjudgmental. They can be used to establish trust in difficult situations. For example, the dental hygienist might say to an angry client who has lost mobility after a stroke, “It must be very frustrating to know what you want and not be able to do it.” This perception of clients’ viewpoints helps the dental hygienist to better understand them, their reaction to dental hygiene care, and their capabilities for taking responsibility for their own health.

THERAPEUTIC COMMUNICATION TECHNIQUES

Dental hygiene practice is based on helping relationships. In such relationships the dental hygienist assumes the role of professional helper. The dental hygienist uses therapeutic communication to promote a psychologic climate that facilitates positive change and growth.

Therapeutic communication is a process of sending and receiving messages between a client and a healthcare provider that assists the client to make decisions and reach goals related to comfort and health. No single communication technique works with all clients. One individual may be encouraged to express feelings when the dental hygienist is silent, whereas another may need coaxing with active questioning. Practice and experience, based on a strong theoretic foundation, are required for choosing communication techniques to use in different situations. See Box 4-4 for some techniques that can be applied by the dental hygienist.1

Silence

Silence can be used effectively in communication because it provides an opportunity for the message senders and receivers to gather and reorganize their thoughts and feelings. During silent moments, nonverbal messages such as loss of eye contact or a wrinkled brow can be sent. Remaining silent may be uncomfortable, but adhering patiently to silence demonstrates the hygienist’s willingness to listen and encourages clients to share their thoughts. Skill and timing are required to use silence effectively. The tendency for some is to want to break the silence too soon. Poor timing can prematurely interrupt clients’ efforts in choosing words and frustrate their attempts to communicate.

The nature of dental hygiene care often precludes talking by the client. A common complaint, usually shared good-naturedly among clients, is that their dental hygienist asks them questions when the hygienist’s hands are in their mouths! This typical scenario is unfair to the client. Common courtesy dictates that immediately on asking a question the hygienist removes hands, instruments, and saliva ejectors from the client’s mouth to allow the client an opportunity to respond through speaking, not just grunting.

Listening Attentively

Caring involves an interpersonal interaction that is much more than two persons talking back and forth. In a caring relationship, the dental hygienist establishes trust, opens lines of communication, and listens to what the client has to say. Listening attentively is key because it conveys to clients that they have the hygienist’s full attention and interest. Listening to the meaning of what a client says helps create a mutual relationship.

The dental hygienist indicates interest by appearing natural and relaxed and facing the client with good eye contact (Figure 4-3). Whatever the services being rendered, the client should remain the center of attention, with the hygienist’s ears available to evaluate and respond. Interpersonal attending skills shown in Table 4-1 facilitate active listening and communication.

TABLE 4-1 Checklist of Interpersonal Attending

| Skill Area | Criterion |

|---|---|

| Eye contact | Listener consistently focuses on the face and eyes of the speaker |

| Body orientation | Listener orients shoulders and legs toward the speaker |

| Posture | Listener maintains slight forward lean, arms maintained in a relaxed position |

| Silence | Listener avoids interrupting the speaker and uses periods of silence to facilitate communication |

| Following cues | Listener uses verbal and nonverbal cues to facilitate communication and indicate interest and attention |

| Distance | Listener maintains distance of 3-4 feet from speaker |

| Distractions | Listener avoids distracting behaviors such as pencil tapping, looking at a clock, and extraneous movements |

Adapted from Geboy MJ: Communications and behavior management in dentistry, Baltimore, 1985, Williams and Wilkins.

Conveying Acceptance

Conveying acceptance requires a tolerant, nonjudgmental attitude toward clients. An open, accepting approach is needed to foster a helping relationship between hygienist and client. Care is taken to avoid nonverbal behavior that may be offensive or that may prevent free-flowing communication. Gestures such as frowning, rolling eyes upward, or shaking the head may communicate disagreement or disapproval to the client. The dental hygienist shows willingness to listen to the client’s viewpoint and provide feedback that indicates understanding and acceptance of the person.

Humor

Humor can help decrease client anxiety and embarrassment. Humor is a communication technique that needs to be used comfortably and naturally with clients of all ages and stages of development (Figure 4-4). The therapeutic advantages of humor and laughter have been documented. Laughter decreases serum control levels, increases immune activity, and stimulates endorphin release from the hypothalamus. In so doing, it relieves stress-related tension and pain. Cousins described the role of humor in his recovery from two life-threatening illnesses.3 His experience suggests that laughter and positive emotions are vital to the success of any medical treatment as well as to life in general.

Figure 4-4 Sharing a joke or laughing with clients can assist in reducing stress and support a therapeutic relationship.

Healthcare personnel and facilities can be perceived as frightening by clients of all ages. Humor as a technique of communication can put people at ease. Even a simple smile can help establish a warm social bond. In her book Communication in Health Care, Collins states, “humor has childlike qualities of playfulness. If one can be playful, one still has vestiges of youth and vigor.”4 The unexpected, the incongruous, the pun, and the exaggeration or understatement are examples of humor that can be effective with both younger and older clients.

Asking Questions

One of the most critical and valuable tools in the dental hygienists’ arsenal of communication skills is the art of questioning. Although there are many types of questions, there are only two basic forms: closed-ended questions, which are directive, and open-ended questions, which are nondirective.

Closed-Ended Questions

Closed-ended questions require narrow answers to specific queries. The answer to these questions is usually “yes” or “no” or some other brief answer. An example is, “Do you want to bleach your teeth?”

Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions are generally used to elicit a wide range of responses on a broad topic. Open-ended questions usually have the following characteristics:

Open-ended questions are usually more effective than questions that require a simple “yes” or “no” answer. Open-ended questioning allows clients to elaborate and show their genuine feelings by bringing up whatever they think is important (Box 4-5). Skillful questioning by the dental hygienist promotes communication.

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing means restating or summarizing what the client has just said. Through paraphrasing the client receives a signal that his or her message has been received and understood and is prompted to continue a communication effort by providing further information. The client may say, “I don’t understand how I could have periodontal disease. My teeth and gums feel fine. I have absolutely no pain.” The hygienist could paraphrase the statement by saying, “You’re not convinced that you have periodontal disease or any gum problems because you have no discomfort?” The client may respond, “Right, I just can’t believe anything is wrong with my mouth.” By actively listening and paraphrasing, the dental hygienist’s response allows further analysis of the problem and opens the conversation for communication and problem solving.

The dental hygienist actively listens and analyzes messages received, however, so that the paraphrase is an accurate account not only of what the client actually says, but also of what the client feels. For example, if a client sends verbal or nonverbal messages of anger or frustration about being told to floss more, the dental hygienist could say, “It sounds like this situation has really upset you and that you are frustrated with me for not recognizing your efforts.” This response encourages clients to communicate further about health problems. Passive listening or silence on the part of the dental hygienist, with no attempt to decode the message, could result in an uncomfortable impasse in the communication process.

Clarifying

At times the message sent by the client may be vague. When clarification is needed, the discussion should be temporarily stopped until confusing or conflicting statements have been understood. For example, consider Scenario 4-2, in which a client has come to the oral care environment for oral prophylaxis. In responding this way the hygienist is trying to get clarification. The client’s rush of words seems to be related to her own problems, but the hygienist cannot be sure until the client states it clearly (see the discussion of subcategories of open-ended questions that enhance communication). In addition, the hygienist should be aware that statements made to the client may need clarification. To fulfill their human need for conceptualization and problem solving, clients need to understand why they are asked to comply with a specific home care regimen. In Scenario 4-3, the dental hygienist has completed therapeutic scaling and root planing on the mandibular left quadrant, which has been anesthetized. The more specific the hygienist can be, the clearer the message to the client.

| Client: | My mother had pyorrhea and lost all her teeth at a young age. I’m sure it’s hereditary. I can only hope to stall it off. |

| Hygienist: | Mrs. Thompson, are you having some problem with your teeth or gums now? |

| Hygienist: | Mr. Johnson, after you leave, try not to chew on your left side for awhile. |

| Client: | Do you mean today or for several days? |

| Hygienist: | Oh no, I just mean for a few hours. |

| Client: | What might happen if I do chew on that side? Will it hurt my teeth or gums? |

| Hygienist: | Oh no, I was referring to your anesthesia. I’m afraid you might bite your cheeks or tongue if you chew on that side, because everything is numb. The numbness should be completely gone by about 5:00 pm. |

Focusing

Sometimes when clients discuss health-related issues the messages become redundant or rambling. Important information may not surface because the client is off on a tangent. Dental hygienists ask questions to clarify when they are unsure of what the client is talking about. In focusing, however, the hygienist knows what the client is talking about but is having trouble keeping the client on the subject so that data gathering and assessment can be completed. In such cases the dental hygienist encourages verbalization but steers the discussion back on track as a technique to improve communication. Rather than asking a question, a gentle command may be in order, such as “Please point to the tooth that seems to be causing your discomfort,” or “Show me exactly what you do when you floss your back teeth” (Table 4-2).

TABLE 4-2 Subcategories of Open-Ended Questions That Enhance Communication

| Type | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Clarifying questions | To seek verification of the content and/or feeling of the client’s message | |

| Developmental questions | To draw out a broad response on a narrow topic | |

| Directive questions | To change the conversation from one topic to another | What was the other issue you wanted to discuss with me? |

| Third-party questions | To probe indirectly by relating to a client how others feel about a situation and then asking the client to give an opinion or reaction | A lot of people feel our fees are reasonable. What’s your opinion? |

| Testing questions | To assess a client’s level of agreement or disagreement about a specific issue | How does that strike you? Do you think you could live with that? |

Stating Observations

Clients may be unaware of the nonverbal messages they are sending. When a client is asked, “How are you, Mrs. Jones?” as a friendly greeting, she may respond, “Oh, just fine.” Her appearance, gait, and mannerisms may indicate something different. She may look slightly unkempt, walk with a slow shuffle, and display generally unenthusiastic gestures and facial expressions. When nonverbal cues conflict with the verbal message, stating a simple straightforward observation may open the lines of communication. The hygienist may say, “You appear very tired, Mrs. Jones.” This is likely to cause the person to volunteer more information about how she feels without need for further questioning, focusing, or clarifying.

To promote positive communication, however, the dental hygienist uses respectful language. The client may feel sensitive about how observations are worded. Saying you look “tired” is different from saying you look “haggard,” which could embarrass or anger a person. Other observations that can soften a client’s response are stating that teeth are “crowded” rather than “crooked,” that a troublesome tongue is “muscular” not “fat,” and that gingiva is “pigmented” not “discolored.”

Offering Information

Providing clients with detailed information facilitates communication. Although providing information may not be enough to motivate people to change health behaviors, clients have a right to receive information based on the hygienist’s expertise so that they can make health-related decisions based on that information. In any setting, a dental hygienist has a professional obligation to provide health information to all clients, not just to individuals who request information.

Summarizing

Summarizing points discussed at a regularly scheduled appointment focuses attention on the major points of the communicative interaction. For example, the dental hygienist may conclude the appointment with, “Today we discussed the purpose of therapeutic scaling and root planing and the periodontal disease process, and we practiced flossing technique. Remember, you decided to floss daily and to try to slip the floss carefully down below the gum line.” If the client is coming in for multiple appointments to receive quadrant or sextant scaling and root planing, the discussion from the previous appointment is summarized before new information is given. Documentation in the client’s chart at each appointment reflects topics discussed at the appointment as related to the client’s goals.

The summary serves as a review of the key aspects of the information presented so that the client can ask for clarification. Adding new information in the summary may confuse the client; however, a comment about what will be discussed at the next appointment is appropriate. Such a statement might be, “At your next appointment, we will talk about use of the Perio-Aid and continue discussion of the periodontal disease process.”

FACTORS THAT INHIBIT COMMUNICATION

The dental hygienist may unintentionally impede communication. Nontherapeutic communication is a process of sending and receiving messages that does not help clients make decisions or reach goals related to their comfort and health (Box 4-6). These nontherapeutic communication techniques should be avoided by the dental hygienist because they inhibit communication.1

Giving an Opinion

A helping relationship fosters the clients’ ability to make their own decisions about health. A hygienist may be tempted to offer an opinion, which may weaken the clients’ autonomy and jeopardize their need for responsibility for oral health. Clients may volunteer personal information about themselves and may ask for the hygienist’s opinion. It is best in such a situation to acknowledge the individual’s feelings but to avoid the transfer of decision making from client to hygienist. Scenario 4-4 is a hypothetic situation presenting two possible responses by the dental hygienist in an interaction with a client. The latter response by the dental hygienist recognizes feelings without expressing an opinion that could make the client feel worse by confirming a doubt she has about her daughter, as in the first response.

| Hygienist: | Mrs. Smith, you look troubled today. |

| Client: | Well, actually, I’m feeling quite down in the dumps. Yesterday was my birthday and I didn’t hear a word from my daughter. I’m sure you wouldn’t do such a thing to your mother! |

| Hygienist: (Response #1) | Heavens, no! How terribly inconsiderate of her. |

| The hygienist might have answered differently: | |

| Hygienist: (Response #2) | You seem to feel really disappointed. I’m sorry you’re so distressed. |

Offering False Reassurance

Hygienists may at times offer reassurance when it is not well grounded. It is natural to want to alleviate the client’s anxiety and fear, but reassurance may promise something that cannot occur. For example, the dental hygienist should not promise clients that they will experience no discomfort during an anticipated dental treatment. Although the dental hygienist may feel confident that the oral surgeon or periodontist is competent and kind, discomfort may be unavoidable. In addition, when clients are distraught about having periodontal disease it is best not to say, “There’s nothing to worry about. You’ll be fine.” Indeed, depending on the amount of bone loss present and the client’s disease susceptibility, the periodontist may not be able to control the disease, even with extensive therapy. Scenario 4-5 illustrates how the dental hygienist can listen to and acknowledge a client’s feelings without offering false assurance that the problem is a simple one.

Mrs. Frank, a 75-year-old woman, has been told by the dentist that her remaining teeth are hopeless and must be extracted for a full denture placement. The hygienist enters the room as the dentist leaves.

| Mrs. Frank: | I can’t believe this is happening to me. I don’t deserve it. I’ve tried to take good care of my teeth. I’m so distressed. Oh, I’m sorry, I know you don’t want to hear about my problems. |

| Hygienist: | Mrs. Frank, I am interested in your feelings about this. |

Being Defensive

When clients criticize services or personnel, it is easy for the hygienist to become defensive. A defensive posture may threaten the relationship between dental hygienist and client by communicating to clients that they do not have a right to express their opinions.

In Scenario 4-6 the dental hygienist’s response ignores the client’s real feelings and hurts future rapport and communication with him. Instead, it would have been better for the hygienist to use the therapeutic communication techniques of active listening to verify what the client has to say and to learn why he is upset or angry. Active listening does not mean that the dental hygienist agrees with what is being said, but rather conveys interest in what the client is saying. This latter approach is illustrated in the Scenario 4-7.

Mr. Tucker has been a regular client in the dental practice for many years. At the last appointment the dental hygienist noted a 2-mm circumscribed white lesion in the retromolar area. Mr. Tucker was a former smoker, and the dentist referred him to an oral surgeon for consultation and possible biopsy of the lesion. The following describes the hygienist-client interaction when Mr. Tucker returns for his periodontal maintenance appointment.

| Client: | I hope I don’t have to see Dr. Herman today. |

| Hygienist: | What’s wrong, Mr. Tucker? Dr. Herman usually sees you after your periodontal maintenance care. |

| Client: | He sent me to the oral surgeon and it was a complete waste of my time. |

| Hygienist: | Of course it wasn’t. Dr. Herman is an excellent dentist. |

| Client: | You may think so, but he didn’t send you for a biopsy for no reason. |

| Hygienist: | Mr. Tucker, that lesion looked very unusual. I’m sure Dr. Herman made a good decision in sending you. |

| Client: | I hope I don’t have to see Dr. Herman today. |

| Hygienist: | You sound upset. Can you tell me something about it? |

| Client: | I just don’t think he should have sent me to that oral surgeon. |

| Hygienist: | You think the visit there was unnecessary? |

| Client: | Yes. I didn’t mind the biopsy, the results were negative, but first I got lost trying to find the place, then I couldn’t find a parking place, then they made me wait for 2 hours, and finally they charged me a fortune for the procedure. Actually, I didn’t mind the cost as much as the inconvenience. |

Some care in listening led to discovery of the source of the client’s anger, which was the inconvenience of a particular oral surgeon’s location, parking, and office procedures. By avoiding defensiveness and applying active listening and paraphrasing, the hygienist allowed Mr. Tucker to vent his anger. Therefore communication was facilitated, not blocked.

Showing Approval or Disapproval

Showing either approval or disapproval in certain situations can be detrimental to the communication process. Excessive praise may imply to the client that the hygienist thinks the behavior being praised is the only acceptable one. Often, clients may reveal information about themselves because they are seeking a way to express their feelings; they are not necessarily looking for approval or disapproval from the dental hygienist. In Scenario 4-8 the hygienist’s response cannot be interpreted as neutral.

| Client: | I’ve been walking to my dental appointments for years. My daughter offered to drive me today and I accepted. She feels the walk has become too much for me. |

| Hygienist: | I’m so glad you didn’t walk over. You definitely made the right decision. Your daughter should drive you to your appointments from now on. |

The discussion in Scenario 4-8 is likely to stop with the dental hygienist’s statements. The client probably sees the hygienist’s viewpoint as supportive of her daughter’s. Perhaps the woman is better off having her daughter drive her. It is also possible that she is capable of walking, likes the exercise, and enjoys the independence of getting to her own appointments. The dental hygienist’s strong statements of approval may inhibit further communication.

In addition, behaviors that communicate disapproval cause clients to feel rejected, and their desire to interact further with the dental hygienist may be weakened. Disapproving statements may be issued by a dental hygienist who is not thinking carefully about how the client may react. Scenario 4-9 exemplifies a dental hygienist’s response that communicates hasty disapproval.

| Client: | I’ve been working so hard at flossing! I only missed 2 or 3 days last week. |

| Hygienist: | Two or 3 days without flossing! You’ll have to do better than that. Your inflammation will not improve at that rate. |

Instead of this response the dental hygienist might have said, “You’re making progress. Tell me more about your activities on those 3 days when you weren’t able to floss. Perhaps together we could find a better way of integrating flossing into your lifestyle.”

Asking Why

When people are puzzled by another’s behavior, the natural reaction is to ask “Why?” When dental hygienists discover that clients have not been following recommendations, they may feel a natural inclination to ask why this has occurred. Clients may interpret such a question as an accusation. They may feel resentment, leading to withdrawal and a lack of motivation to communicate further with the dental hygienist.

Efforts to search for reasons why the client has not practiced the oral healthcare behaviors as recommended can be facilitated by simply rephrasing a probing “why” question. For example, rather than saying, “Why haven’t you used the oral irrigator?” the hygienist might say, “You haven’t used the oral irrigator. Is something wrong?” For anxious clients, rather than asking, “Why are you upset?” the hygienist might say, “You seem upset. Would you like to talk about it?

Changing the Subject Inappropriately

Changing the subject abruptly shows a lack of empathy and could be interpreted as rude. In addition, it prevents the client from discussing an issue that may have important implications for care. Scenario 4-10 is a sample client–dental hygienist interaction.

| Hygienist: | Hello, Mrs. Johnson. How are you today? |

| Client: | Not too well. My gums are really sore. |

| Hygienist: | Well, let’s get you going. We have a lot to do today. |

The dental hygienist’s response shows insensitivity and an unwillingness to discuss Mrs. Johnson’s complaint. It is possible that the client has a periodontal or periapical abscess or some other serious problem. The dental hygienist is remiss in ignoring the client’s attempt to communicate a problem. Communication has been stalled, and the client’s oral health jeopardized. The client should be given an opportunity to elaborate on the message she is trying to send.

Motivational Interviewing5

In the communication process a dental hygienist is constantly striving to influence the client’s motivation to perform oral health behaviors. Motivation can be defined as the impulse that leads an individual to action. Many theories of motivation have been formulated and can be appropriately applied to client motivation in the healthcare environment. The motivational interview is a form of patient-centered communication to help clients get “unstuck from the ambivalence that prevents a specific behavioral change” (see Chapter 34).

COMMUNICATION ACROSS THE LIFE SPAN

Dental hygienists assume the role of educator when clients have learning needs. The communication and the teaching and learning processes are applied across the life span but need to be tailored to each client’s age level. Andragogy is the art and science of helping the older person learn, whereas pedagogy is the art and science of teaching children. Pedagogy assumes that the learners are young, dependent recipients of knowledge and that subject matter has been arbitrarily decided on by a teacher who is preparing them for their future. The teacher is the authority in this model, and little regard is given to how learners feel about the material or to their contribution to the process. Andragogy, on the other hand, assumes that the initiative to learn comes from the learner, who is viewed as entering the learning process with a background of prior knowledge and experience. The teacher is a facilitator who learns along with the student, who in turn benefits from the teacher’s contribution. The adult learner has a diverse history of experiences and is, in general, independent and self-directed. Pedagogy assumes that the child learner is moving toward becoming a fully matured human being, whereas andragogy assumes that the learner has arrived at this point.6 The purpose of this section is to address considerations for communication with clients throughout the life span. Table 4-3 summarizes the key developmental characteristics at different age levels over the life span and those communication techniques appropriate at each level.7

TABLE 4-3 Techniques for Communicating with Clients through the Life Span

| Level | Developmental Characteristics | Communication Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Preschoolers | Beginning use of symbols and language; egocentric, focused on self; concrete in thinking and language | |

| School-age children | Less egocentric; shift to abstract thought emerges, but much thought still concrete | Demonstrate equipment, allow child to question, give simple explanations of procedures |

| Adolescents | Concrete thinking evolves to more complex abstraction; can formulate alternative hypotheses in problem solving; may revert to childish manner at times; usually enjoy adult attention | |

| Adults | Broad individual differences in values, experiences, and attitudes; self-directed and independent in comparison with children; have assumed certain family and social roles; periods of stability and change | Appropriately applied therapeutic communication techniques: maintaining silence, listening attentively, conveying acceptance, asking related questions, paraphrasing, clarifying, focusing, stating observations, offering information, summarizing, reflective responding |

| Older adults | May have sensory loss of hearing, vision; may have high level of anxiety; may be willing to comply with recommendations, but forgetful |

Adapted from Potter PA, Perry AG: Fundamentals of nursing: concepts, process, and practice, ed 3, St Louis, 1993, Mosby.

Preschool and Younger School-Age Children

Communicating with children requires an understanding of the influence of growth and development on language, thought processes, and motor skills. Children begin development with simple, concrete language and thinking and move toward the more complex and abstract. Communication techniques and teaching methods also can increase in complexity as the child grows older.

Nonverbal communication is more important with preschoolers than it is with the school-age child whose communication is better developed. The preschooler learns through play and enjoys a gamelike atmosphere. Hence, dentists often call the dental engine their “whistle” or the “buzzy bee,” and hygienists often refer to their polishing cup as the “whirly bird” and the saliva ejector as “Mr. Thirsty.” Imaginary names help lighten the healthcare experience for small children. Oral health professionals are advised to use simple, short sentences, familiar words, and concrete explanations.

The Guidance-Cooperation Model

Five principles for communicating with young children are suggested in the Guidance-Cooperation Model.8 Because the model is neither permissive nor coercive, it is ideally suited for the preschool or young school-age child. Under this model, health professionals are placed in a parental role whereby the child is expected to respect and cooperate with them. The principles inherent to the Guidance-Cooperative Model follow.

Tell the Child the Ground Rules before and during Treatment

Let the child know exactly what is expected of him or her. A comment such as, “You must do exactly as I ask and please keep your hands in your lap like my other helpers,” will prepare the child to meet expectations. Structuring time so the child also knows what to expect may be useful. For fluoride treatments, a timer should be set and made visible so the child knows how long it will be before the trays will come out of his or her mouth.

Praise All Cooperative Behavior

When children respond to a directive such as “Open wide,” praise them with, “That’s good! Thank you!” When children sit quietly, remember to praise them for cooperation. It is a mistake to ignore behavior until it is a problem.

Keep Your Cool

Ignore negative behavior such as whining if it is not interfering with the healthcare. Showing anger will only make matters worse. Showing displeasure and using a calm voice for statements such as “I get upset (or unhappy, etc.) when you…,” is likely to get the point across more successfully.

Use Voice Control

A sudden change in volume can gain attention from a child who is being uncooperative. Modulate voice tone and volume as soon as the child begins to respond.

Allow the Child to Play a Role

Let the child make some structured choices. For example, ask, “Would you like strawberry or grape flavored fluoride today?” Most younger children enjoy the role of “helper” and are happy to hold mirrors, papers, and pencils and to receive praise for their good work.

Avoid Attempting to Talk a Child into Cooperation

Do not give lengthy rationales for the necessity of procedures. Rather, acknowledge the child’s feelings by making statements such as, “I understand that you don’t like the fluoride treatment; however, we must do it to make your teeth stronger. I understand that you would rather be outside playing, but we need to polish your teeth now.” Then firmly request the child’s attention and cooperation and proceed with the service.

Both the preschool and school-age child are eager to learn and explore but may have fears about the oral healthcare environment, personnel, and treatment. Studies have shown that dental fears begin in childhood, and making early oral care a positive experience is necessary if the dental hygienist is interested in the client’s long-term attitude toward oral health.4 Rapport must be established as a foundation for cooperation and trust. The best teaching approaches for younger children follow behavioral rather than cognitive theory. Positive reinforcement used as immediate feedback, short instructional segments with simplified language and content that is concrete rather than abstract, close monitoring of progress, and encouragement for independence in the practice of oral hygiene skills are all indicated.

Older School-Age Children and Adolescents

Adolescence is not a single stage of development. The rate at which children progress through adolescence and the psychologic states that accompany the changes can vary considerably from one child to another.4 In early adolescence (about 13 to 15 years old), children may rather suddenly demonstrate an ambivalence toward parents and other adults, manifested by questioning of adult values and authority. By late adolescence (18 years and older) much of the ambivalence is gone and values that characterize the adult years have fully emerged. Friendship patterns in early and middle adolescence are usually intense as the child begins to explore companionship outside the family and become established as an independent person (Figure 4-5).

Some common complaints from the adolescent’s point of view can sensitize health professionals for positive interactions with this group of young people. First, a frequently voiced complaint of adolescents is that adults do not listen to them. They seem to feel that adults are in too much of a hurry, appear to be looking for certain answers, or listen only to what they want to hear. A second complaint is that too often a conversation turns into unsolicited advice or a mini-lecture. A young person, asked to describe specific experiences in dentistry, related the following8:

My dentist bugged me a lot. He would become angry if I felt pain. He pushed my hair around and lectured constantly about young people and their hair.

Other less-common complaints from adolescents are that they are patronized, that they do not understand questions being asked, and finally that adults lack humor.

Dental hygienists should consider carefully these complaints and practice behaviors that enhance communication with adolescents. Being attentive and allowing the adolescent time to talk enhances rapport and communication. Some rapport-building questions at the beginning of the appointment may relate to family, school, personal interests, or career intentions. It is useful to have some knowledge of the contemporary interests of adolescents, which may include trends in music, sports, and fashion. They want a sense of being understood and do not want to be judged or lectured.

Adolescents have a strong human need for responsibility. An astute dental hygienist can use these unfulfilled needs to motivate the adolescent client to adopt oral self-care behaviors. This educational approach, based on human needs theory, can enhance adolescents’ sense of personal responsibility toward the care of their mouths. In order that adolescents do not feel singled out, a dental hygienist might say, “We encourage all of our adult clients to floss daily. This is because we know it works. We’ve seen the results.” Teenagers do not feel patronized or confused if questions and advice are offered in a sincere, straightforward manner.

Adults

Havinghurst delineated three developmental stages for adults and listed common adult concerns at each stage.7 Although communication techniques may not differ greatly for the adult stages, knowledge of general differences in characteristics among age groups can enlighten the hygienist about typical concerns of clients at different periods of adulthood. An awareness of how priorities in life change for adults as they develop can help the hygienist identify learning needs and “teachable moments” for different clients. The Havinghurst adult stages are summarized in Box 4-7 according to early adulthood, middle age, and late maturity. The dental hygienist should be aware, without asking personal questions, that young adults may be trying to institute oral self-care behaviors while adjusting to major life stresses such as bringing up young children, managing a home, or starting a demanding career. Adults in the middle years may be more settled in careers and have less responsibility for child care but may be heavily involved in social responsibilities, adjusting to their personal physical changes, or the demands of caring for aging parents. Older adults may be adjusting to decreasing physical strength, a chronic health problem, retirement, or death of a spouse. The elderly population is a highly diversified group (Figure 4-6). The wide variations in health and psychologic states dictate the necessity of careful assessment of each individual (see Chapter 54).

BOX 4-7 Havinghurst’s Description of the Adult Developmental Stages

Adapted from Darkenwald GG, Merriam SB: Adult education: foundations of practice, New York, 1982, Harper and Row.

Communication approaches appropriate for adults are the therapeutic communication techniques discussed previously in this chapter. In using the techniques, it is important for the dental hygienist to be familiar with the adult developmental stages and aware of what demands may be preventing adults of the different stages from easily making oral healthcare behavioral changes. Modern adult learning theory has been supported by some basic assumptions (Box 4-8). Keeping these assumptions in mind facilitates communication with adults who become “learners” as dental hygienists become “teachers” in the healthcare setting. These assumptions can enhance communication and the dental hygiene educator’s approach to teaching adults.

BOX 4-8 Assumptions Related to Adult Learners

BEHAVIORAL CHANGE THEORIES9

Dental hygienists spend much of their work time in one-on-one activities such as counseling or client education. This section presents behavioral change theories and their applications at the individual (intrapersonal) and interpersonal levels. Contemporary behavioral change theories can be broadly categorized as “cognitive-behavioral.” Three key concepts cut across these theories:

Intrapersonal Theories

In addition to exploring behavior, individual-level theories focus on intrapersonal factors (those existing or occurring within the individual self or mind). Intrapersonal factors include knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, motivation, self-concept, developmental history, past experience, and skills. Individual-level theories are as follows.

The Health Belief Model (HBM) addresses the individual’s perceptions of the threat posed by a health problem (susceptibility, severity), the benefits of avoiding the threat, and factors influencing the decision to act (barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy).

The Health Belief Model (HBM) addresses the individual’s perceptions of the threat posed by a health problem (susceptibility, severity), the benefits of avoiding the threat, and factors influencing the decision to act (barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy). The Stages of Change (Transtheoretical) Model describes individuals’ motivation and readiness to change a behavior.

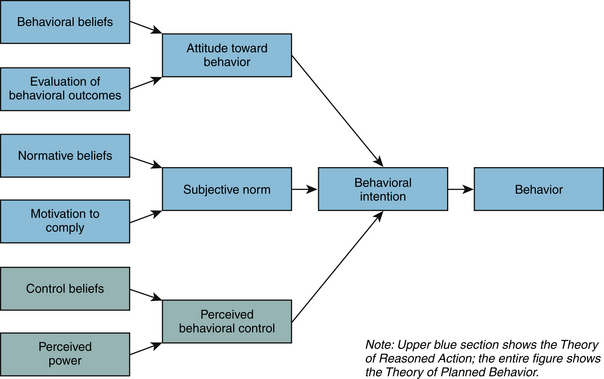

The Stages of Change (Transtheoretical) Model describes individuals’ motivation and readiness to change a behavior. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) examines the relations between an individual’s beliefs, attitudes, intentions, behavior, and perceived control over that behavior.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) examines the relations between an individual’s beliefs, attitudes, intentions, behavior, and perceived control over that behavior.Health Belief Model

The HBM was one of the first theories of health behavior and remains one of the most widely recognized in the field. It was developed in the 1950s by a group of U.S. Public Health Service social psychologists who wanted to explain why so few people were participating in programs to prevent and detect disease. For example, the Public Health Service was sending mobile x-ray units out to neighborhoods to offer free chest x-ray examinations (screening for tuberculosis). Despite the fact that this service was offered without charge in a variety of convenient locations, the program was of limited success. The question was, “Why?” To find an answer, social psychologists examined what was encouraging or discouraging people from participating in the programs. They theorized that people’s beliefs about whether or not they were susceptible to disease, and their perceptions of the benefits of trying to avoid it, influenced their readiness to act.

In ensuing years, researchers expanded on this theory, eventually concluding that six main constructs influence people’s decisions about whether to take action to engage in preventive behavior. They argued that people are ready to act in the following circumstances:

If they believe taking action would reduce their susceptibility to the condition or its severity (perceived benefits)

If they believe taking action would reduce their susceptibility to the condition or its severity (perceived benefits) If they are exposed to factors that prompt action (e.g., a reminder from one’s dental hygienist to rinse with 0.05% sodium fluoride twice a day to prevent demineralization of tooth surfaces), called cue(s) to action

If they are exposed to factors that prompt action (e.g., a reminder from one’s dental hygienist to rinse with 0.05% sodium fluoride twice a day to prevent demineralization of tooth surfaces), called cue(s) to actionTogether these six components of the HBM provide a useful framework for designing both short-term and long-term behavioral change strategies (Table 4-4). When applying the HBM to planning health programs, practitioners should ground their efforts in an understanding of how susceptible the target population feels to the health problem, whether these people believe it is serious, and whether they believe action can reduce the threat at an acceptable cost. Attempting to effect changes in these factors is rarely as simple as it may appear.

TABLE 4-4 The Health Belief Model Used in Designing Behavioral Change Strategies

| Concept | Definition | Potential Change Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived susceptibility | Beliefs about the chances of getting a condition | |

| Perceived severity | Beliefs about the seriousness of a condition and its consequences | Specify the consequences of a condition and recommended action |

| Perceived benefits | Beliefs about the effectiveness of taking action to reduce risk or seriousness | Explain how, where, and when to take action and what the potential positive results will be |

| Perceived barriers | Beliefs about the material and psychologic costs of taking action | Offer reassurance, incentives, and assistance; correct misinformation |

| Cues to action | Factors that activate readiness to change | Provide “how-to” information, promote awareness, and employ reminder systems |

| Self-efficacy | Confidence in one’s ability to take action |

Stages of Change (Transtheoretical) Theory

The Stages of Change Theory evolved out of studies comparing the experiences of smokers who quit on their own with those of smokers who received professional treatment. The model’s basic premise is that behavioral change is a process, not an event. As persons attempt to change a behavior, they move through five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance (Table 4-5). Definitions of the stages vary slightly, depending on the behavior at issue. People at different points along this continuum have different informational needs and benefit from interventions designed for their stage.

TABLE 4-5 Use of the Stages of Change Model in Designing Behavioral Change Strategies

| Stage | Definition | Potential Change Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Precontemplation | Has no intention of taking action within the next 6 months | Increase awareness of need for change; personalize information about risks and benefits |

| Contemplation | Intends to take action in the next 6 months | Motivate; encourage making specific plans |

| Preparation | Intends to take action within the next 30 days and has taken some behavioral steps in this direction | Assist with developing and implementing concrete plans; help set gradual goals |

| Action | Has changed behavior for less than 6 months | Assist with feedback, problem solving, social support, and reinforcement |

| Maintenance | Has changed behavior for more than 6 months | Assist with coping, reminders, finding alternatives, avoiding slips or relapses (as applicable) |

Whether individuals use self-management methods or take part in professional programs, they go through the same stages of change. Nonetheless, the manner in which they pass through these stages may vary depending on the type of behavioral change. For example, a person who is trying to give up smoking may experience the stages differently than someone who is seeking to improve dietary habits by eating more fruits and vegetables.

The Stages of Change Theory has been applied to a variety of individual behaviors, as well as to organizational change. The model is circular, not linear. In other words, people do not systematically progress from one stage to the next, ultimately “graduating” from the behavioral change process. Instead, they may enter the change process at any stage, relapse to an earlier stage, and begin the process once more. They may cycle through this process repeatedly, and the process can start or stop at any point.

Theory of Planned Behavior

The TPB and the associated Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) explore the relationship between behavior and beliefs, attitudes, and intentions. Both the TPB and the TRA assume behavioral intention is the most important determinant of behavior. According to these models, behavioral intention is influenced by a person’s attitude toward performing a behavior and by beliefs about whether individuals who are important to the person approve or disapprove of the behavior (subjective norm). The TPB and TRA assume all other factors (e.g., culture, the environment) operate through the model’s constructs and do not independently explain the likelihood that a person will behave a certain way.

The TPB differs from the TRA in that it includes one additional construct, perceived behavioral control; this construct has to do with people’s beliefs that they can control a particular behavior. This construct accounts for situations in which people’s behavior, or behavioral intention, is influenced by factors beyond their control. It was believed that people might try harder to perform a behavior if they feel they have a high degree of control over it (Figure 4-7). Clients’ perceptions about controllability may have an important influence on behavior.

Figure 4-7 Theory of Reasoned Action and Theory of Planned Behavior.

(From National Cancer Institute: Theory at a glance: a guide for health promotion practice, ed 2, NIH Publication No. 05-3896, Bethesda, Md, 2005, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health.)

Figure 4-7 shows the TPB’s explanation for how behavioral intention determines behavior and how attitude toward behavior, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control influence behavioral intention. According to the model, attitudes toward behavior are shaped by beliefs about what is entailed in performing the behavior and outcomes of the behavior. Beliefs about social standards and motivation to comply with those norms affect subjective norms. The presence or lack of things that will make it easier or harder to perform the behavior affects perceived behavioral control. Thus a causal chain of beliefs, attitudes, and intentions drives behavior.

Interpersonal Theories

At the interpersonal level, health behavior theories assume individuals exist within, and are influenced by, a social environment. The opinions, thoughts, behavior, advice, and support of the people surrounding an individual influence his or her feelings and behavior, and the individual has a reciprocal effect on those people. The social environment includes family members, co-workers, friends, health professionals, and others. Because it affects behavior, the social environment also affects health. Many theories focus on the interpersonal level, but this chapter highlights Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). SCT is one of the most frequently used and robust health behavior theories. It explores the reciprocal interactions of people and their environments, and the psychosocial determinants of health behavior.

Social Cognitive Theory

SCT describes a dynamic, ongoing process in which personal factors, environmental factors, and human behavior exert influence on one another. According to SCT, three main factors affect the likelihood that a person will change a health behavior: self-efficacy, goals, and outcome expectancies. If individuals have a sense of self-efficacy, they can change behaviors even when faced with obstacles. If they do not feel that they can exercise control over their health behavior, they are not motivated to act or to persist through challenges. As a person adopts new behaviors, this causes changes in both the environment and the person. Behavior is not simply a product of the environment and the person, and environment is not simply a product of the person and behavior.

SCT evolved from research on Social Learning Theory (SLT), which asserts that people learn not only from their own experiences, but by observing the actions of others and the benefits of those actions. The updated SLT added the construct of self-efficacy and was renamed SCT. SCT integrates concepts and processes from cognitive, behaviorist, and emotional models of behavioral change, so it includes many constructs (Table 4-6). It has been used successfully as the underlying theory for behavioral change in areas ranging from dietary change to pain control.

TABLE 4-6 Social Cognitive Theory and Potential Change Strategies

| Concept | Definition | Potential Change Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Reciprocal determinism | The dynamic interaction of the person, behavior, and the environment in which the behavior is performed | Consider multiple ways to promote behavioral change, including making adjustments to the environment or influencing personal attitudes. |

| Behavioral capability | Knowledge and skill to perform a given behavior | Promote mastery learning through skills training. |

| Expectations | Anticipated outcomes of a behavior | Model positive outcomes of healthful behavior. |

| Self-efficacy | Confidence in one’s ability to take action and overcome barriers | Approach behavioral change in small steps to ensure success; be specific about the desired change. |

| Observational learning (modeling) | Behavioral acquisition that occurs by watching the actions and outcomes of others’ behavior | Offer credible role models who perform the targeted behavior. |

| Reinforcements | Responses to a person’s behavior that increase or decrease the likelihood of reoccurrence | Promote self-initiated rewards and incentives. |

Reciprocal determinism describes interactions among behavior, personal factors, and environment, where each influences the others. Behavioral capability states that to perform a behavior a person must know what to do and how to do it. Expectations are the results an individual anticipates from taking action. Bandura considers self-efficacy the most important personal factor in behavioral change, and it is a nearly ubiquitous construct in health behavior theories. Strategies for increasing self-efficacy include setting incremental goals (e.g., brushing for 3 minutes twice a day); behavioral contracting (a formal contract, with specified goals and rewards); and monitoring and reinforcement (feedback from self-monitoring or record keeping).

Observational learning, or modeling, is the process whereby people learn through the experiences of credible others rather than through their own experience. Reinforcements are responses to behavior that affect whether or not one will repeat it. Positive reinforcements (rewards) increase a person’s likelihood of repeating the behavior. Negative reinforcements may make repeated behavior more likely by motivating the person to eliminate a negative stimulus (e.g., when a driver puts the key in the car’s ignition, the beeping alarm reminds him or her to fasten the seatbelt). Reinforcements can be internal or external. Internal rewards are things people do to reward themselves. External rewards (e.g., token incentives) encourage continued participation in multiple-session programs but generally are not effective for sustaining long-term change because they do not bolster a person’s own desire or commitment to change.

Becoming comfortable with behavioral change theory as a practice instrument may take some work, but the results are well worth it. Behavioral change theory is not simply a tool for academics and researchers; it can be applied to the problems dental hygienists face daily. Theory helps practitioners to understand the dynamics underlying real situations and to think about solutions in a new way.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Clients have the right to accept or reject the dental hygiene care plan and still retain the respect of the dental hygienist.

Clients have the right to accept or reject the dental hygiene care plan and still retain the respect of the dental hygienist.KEY CONCEPTS

Communication during the dental hygiene process of care is a dynamic interaction between the dental hygienist and the client that involves both verbal and nonverbal components.

Communication during the dental hygiene process of care is a dynamic interaction between the dental hygienist and the client that involves both verbal and nonverbal components. Factors that may affect the communication process include internal factors of the client and the dental hygienist (e.g., perceptions, values, emotions, and knowledge), the nature of their relationship, the situation prompting communication, and the environment.

Factors that may affect the communication process include internal factors of the client and the dental hygienist (e.g., perceptions, values, emotions, and knowledge), the nature of their relationship, the situation prompting communication, and the environment. Some communication approaches are therapeutic and helpful in assisting clients to make decisions and attain goals related to their comfort and health. Other approaches are nontherapeutic and unsuccessful in helping clients make decisions and attain goals related to their comfort and health.

Some communication approaches are therapeutic and helpful in assisting clients to make decisions and attain goals related to their comfort and health. Other approaches are nontherapeutic and unsuccessful in helping clients make decisions and attain goals related to their comfort and health. Communication techniques used by the dental hygiene clinician must be flexible to relate to the full range of client ages through the life span.

Communication techniques used by the dental hygiene clinician must be flexible to relate to the full range of client ages through the life span.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

In the first session, the “client” should improvise a story of frustration with his or her current oral hygiene regimen by explaining that a heavy workload, family responsibilities, or other interference make it difficult to maintain a good home care regimen. While glancing at a list of the possible responses as a prompt, the “educator” will try to respond with only therapeutic comments. Classroom listeners should try to determine which specific categories of therapeutic communication fit the educator’s comments.

In the first session, the “client” should improvise a story of frustration with his or her current oral hygiene regimen by explaining that a heavy workload, family responsibilities, or other interference make it difficult to maintain a good home care regimen. While glancing at a list of the possible responses as a prompt, the “educator” will try to respond with only therapeutic comments. Classroom listeners should try to determine which specific categories of therapeutic communication fit the educator’s comments.1. Potter P.A., Perry A.G. Fundamentals of nursing, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2009.

2. Heineken J., McCoy N. Establishing a bond with clients of different cultures. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2000;18:45.

3. Cousins N. The healing heart. New York: Avon Books; 1984.

4. Collins M. Communication in health care: understanding and implementing effective human relationships. St Louis: Mosby; 1977.

5. Miller W., Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, ed 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002.

6. Dembo M.H. Teaching for learning: applying educational psychology in the classroom, ed 4. New York: Longmans; 1991.

7. Havinghurst R.J. Developmental tasks and education. New York: McKay; 1952.