CHAPTER 54 The Older Adult

Dental hygienists face many challenges when they provide care for older adults because of the many biologic, psychologic, and social variations within this population. Older adults are certainly a heterogeneous group owing to their lifetime of unique experiences. Life at any given moment is the result of physiologic capabilities, environmental variables, psychosocial factors, and a sense of one’s own skills and alternatives. Therefore the human needs of each older adult must be assessed individually, without prior assumptions based on preconceived stereotypes or myths. The healthcare needs of older adults represent the entire continuum of healthy to severely ill individuals. Dental hygienists are challenged to provide care that often involves complex and multiple medical, social, and psychologic needs and the coordination of multiple levels of healthcare.

DEMOGRAPHIC ASPECTS OF AGING

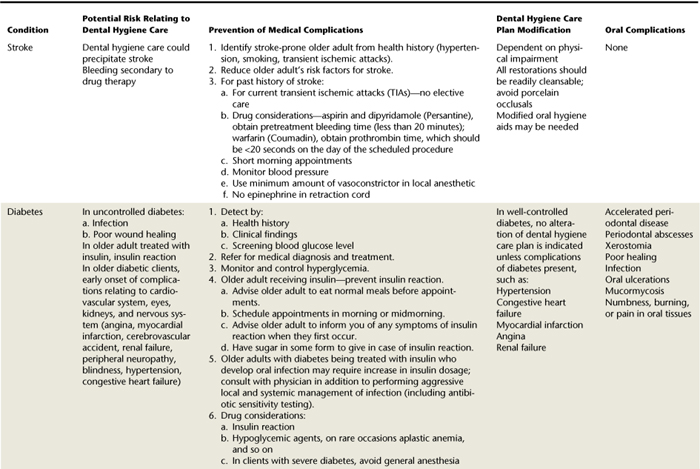

Between 1950 and 2005, the group of individuals 65 years old and older increased at a rate faster than the total population.1 The population of adults 65 years old and older grew on an average of 2% each year, as compared with the total population average annual growth rate of 1.2%. The population of those 75 years of age and older has grown the fastest, increasing at a rate of 2.8% each year, from 4 to 18 million from 1950 to 2005. This substantial rise in the proportion of older adults in the population is projected to continue to increase to 80 million individuals by 20501 (Figure 54-1).

Figure 54-1 Number of older Americans.

(Redrawn from Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics: Older Americans 2008: key indicators of well-being. Available at: http://agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2008_Documents/slides/Population-OA_2008.ppt. Accessed August 7, 2008.)

This significant demographic increase is caused primarily by increases in life expectancy rather than an increase in the overall life span. Life span is the maximal length of life potentially possible in a species—the age beyond which no one can expect to live. For humans, this number is approximately 110 to 120 years. Life expectancy is the average number of years lived by any group of individuals born in the same period and is computed at birth or a specific time point. Individuals born in 1900 had a life expectancy of 47.3 years, which increased to 70 years for those born in 1960. For those born in 2004, life expectancy is 80.4 years for women and 75.2 years for men.1 Life expectancy at ages 65 and 75 have also increased. In 2004 those individuals who survived to 65 could expect to live an average of 18.7 more years, and those individuals who survived to 75 could expect to live an average of at least 11.9 more years.1

The increase in life expectancy is accounted for by the facts that more people are surviving young life (infant and childhood mortality have declined), fertility rates have decreased, and medical care and technology has improved. In addition, the number of people who reach age 65 years in a given year depends heavily on the number of births 65 years earlier. By 2029, all of the “baby boomers” will be 65 years and over, so there will be a “boom” of older adults increasing at a rate greater than the total population at that time. For example, between 2005 and 2030, the population age 65 and over will increase from 6% to 10%. As the baby boomers age, the population age 75 and older will also rise from 6% to 9% in 2030 and will continue to grow to 12% by 2040.1

Other demographic changes in older adult population that affect healthcare include the following:

The older adult population is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. By 2030, projections include 72% non-Hispanic white, 11% Hispanic, 10% black, and 5% Asian.1

The older adult population is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. By 2030, projections include 72% non-Hispanic white, 11% Hispanic, 10% black, and 5% Asian.1 Elderly women outnumber men and are more likely to be widowed at each age group. In 2000, women accounted for 58% of the population age 65 and older and 70% of the population age 85 and older. Women age 65 and older were three times as likely as men of the same age to be widowed—44% as compared with 14% of the men. At age 85 and older the differences increase, because 78% of women at this age group were widows as compared with 42% of men.1

Elderly women outnumber men and are more likely to be widowed at each age group. In 2000, women accounted for 58% of the population age 65 and older and 70% of the population age 85 and older. Women age 65 and older were three times as likely as men of the same age to be widowed—44% as compared with 14% of the men. At age 85 and older the differences increase, because 78% of women at this age group were widows as compared with 42% of men.1 The older adult population is concentrated in key states. In 2000, nine states had more than 1 million people age 65 and older: California, Florida, New York, Texas, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, and New Jersey. In 2005 Florida (19%) had the largest proportion of residents aged 65-plus years in the total population, and Alaska was the state with the fastest growing older adult population.1 As the older population grows both in number and age, demands for housing, healthcare, and protective services will increase, particularly in these heavily proportioned states.

The older adult population is concentrated in key states. In 2000, nine states had more than 1 million people age 65 and older: California, Florida, New York, Texas, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, and New Jersey. In 2005 Florida (19%) had the largest proportion of residents aged 65-plus years in the total population, and Alaska was the state with the fastest growing older adult population.1 As the older population grows both in number and age, demands for housing, healthcare, and protective services will increase, particularly in these heavily proportioned states.These demographic changes in the numbers, composition, and proportion of older adults within the population have a major impact on our society, on healthcare, and on policy implications for federal, state, and local governments.1 The increase in population over 75, in particular, will affect planning for the needs of the aged population, not only for extended care, but for chronic debilitating conditions as well. Already the increasing number of frail elderly has created changes for nursing home residents. For example, nursing home facilities must ensure that all residents be provided with emergency oral care, be furnished with a referral list of dentists, and have dental care—preventive and therapeutic—as promulgated by the State Medicaid Act.

HEALTHCARE FOR OLDER ADULTS

The terms geriatrics and gerontology are often used synonymously in discussions of healthcare for older adults, although there is a difference in their implications. Geriatrics is the branch of medicine concerned with the illnesses of old age and their treatment. Gerontology is the scientific study of the factors affecting the normal aging process and the effects of aging. These terms are not interchangeable. A gerontologist is an individual who investigates numerous factors that affect the aging person and the aging process. Gerontologists have divided study of the older population into several categories based on age: young-old (65 to 74 years), middle-old (75 to 84 years), and old-old (85-plus years). Some sociologists have classified those between the ages of 55 and 64 years as the “new-old” and those older than 95 years as the “very old.” Whatever terms are used, two important facts exist: (1) characterizations of age should be based on functional ability, not chronologic age, and (2) the majority of older adults perform at a relative level of independent function. Chronologic age refers to age as measured by calendar time since birth, whereas functional age is based on performance capacities. Although a calendar may signify a particular age, functional ability should be the standard that differentiates a person’s capability to maintain activity.2

WHY AND HOW PEOPLE AGE

No single theory can explain why and how people age. Rather, an intermingling of social, psychologic, biologic, environmental, physiologic, and lifestyle factors contributes to the aging process, either in accelerating or in retarding its progress, and produces a different course for each individual.2,3 Aging is a progressive yet fluid process, with each factor affecting the others. Understanding the theories of aging—those that have validity and those that contribute to stereotypes—enables the dental hygienist to facilitate human need fulfillment in the older adult through the dental hygiene process of care.

Social Theories of Aging

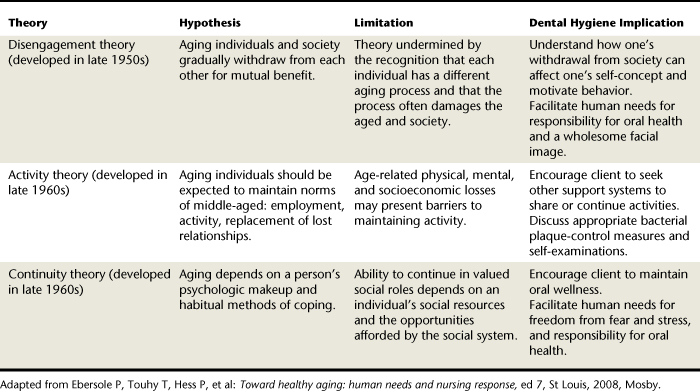

Social science researchers looking at aging use an interdisciplinary perspective to focus on social, psychologic, and environmental factors that affect the lives of older persons.2 Dental hygienists, when planning care, must be aware of and consider the dynamic processes that influence each older client. Table 54-1 provides a summary of the three major theories that explain social aspects of aging: disengagement, continuity, and activity theories.2 Implications for dental hygiene are included within this table to show the application of each of the theories to actions taken during dental hygiene care.

Physiologic Aspects of Aging

Senescence is the term that describes the normal physiologic process of growing old.2 The fact that everyone, given time, eventually experiences physical changes in all of the body systems makes aging universal. Physical changes that occur are normal for all people, but they take place at various rates and depend on accompanying circumstances (e.g., environmental, psychosocial, lifestyle, and biologic factors) in an individual’s life. Typically, normal age changes have been studied in collaboration with pathologic or disease conditions, leading to the misconception that age changes indicate illness or disease. Research continues to uncover evidence that many changes thought to be directly related to the aging process are actually a result of disease or lifestyle influences. For example, a decrease in salivary production was previously thought to be a normal aging feature; however, within the last decade, research has shown that no decrease in salivary production occurs in healthy older adults. Diminished salivary flow is, instead, a byproduct of medications or disease.

Biologic Theories of Aging

Most theorists agree that a unifying theory does not yet exist that explains the mechanics and causes underlying the biologic phenomenon of aging.2 A search for a universal factor or factors is complicated by the fact that signs of aging do not appear in all individuals at the same chronologic age. Biologic theories can be divided into stochastic and nonstochastic theories. Stochastic theories view aging as random events that accumulate over time. Nonstochastic theories explain that aging is a predetermined sequence through the life span. Each hypothesis provides a clue to the aging process, yet many unanswered questions remain. Table 54-2 provides a summary of both stochastic and nonstochastic biologic theories of aging.2 Knowledge of the various biologic theories of aging is necessary for the dental hygienist in understanding physical and mental changes that may affect the older client and the interrelationships of these changes with overall health.

TABLE 54-2 Biologic Theories of Aging

| Dynamics | Retardants | |

|---|---|---|

| Stochastic (Random) Theories | ||

| Error theory | Accumulation of errors in protein synthesis over time impairs cell function | None |

| Free radical theory | Oxidation creates free electrons that attach and alter cell function | Improve environmental monitoring; increase intake of vitamins A, C, and E; decrease intake of radical stimulating foods |

| Cross-link theory | Fibers become more rigid owing to increase in number of cross-links | None |

| Nonstochastic Theories | ||

| Programmed | Biologic clock triggers cell behavior | Hypothermia and diet can delay cell division |

| Neuroendocrine | Efficiency of signals that regulate interplay among organs and tissues is decreased | Hormone treatment |

| Immunologic | Alteration of B and T cells causes loss of capacity | Replacement or rejuvenation of immune system |

Adapted from Ebersole P, Touhy, T, Hess P, et al: Toward healthy aging: human needs and nursing response, ed 7, St Louis, 2008, Mosby.

HEALTH STATUS AND ASSESSMENT

Health assessment of older persons must always include a functional appraisal in addition to a review of health, dental, and personal histories.2 The items generally included within a functional assessment are divided into activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). ADLs are those abilities that are fundamental to independent living, such as bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring from bed or chair, feeding, and continence. More-complex daily activities, such as using the telephone, preparing meals, and managing money, are examples of IADLs. In 2004 25.5% of individuals aged 65 to 74 reported needing help with at least one ADL or IADL, and 43.9% of individuals older than 75 reported needing assistance.1 Knowledge of a client’s functional abilities helps the dental hygienist customize dental hygiene care, especially in recommending appropriate and realistic preventive homecare routines. In addition, knowledge of functional abilities allows the dental team to identify resources and supports necessary to ensure that the most appropriate level of dental care is provided for the client.

Functional assessment becomes important because the pattern of illness and disease has changed over the past century.2 Acute conditions were predominant during the early 1900s, whereas chronic conditions present more-prevalent health problems for older adults today. About 80% of seniors have at least one chronic health condition, and 50% have at least two. Five of the six leading causes of death in older adults are chronic diseases. The leading chronic conditions in older adults are arthritis, hypertension and heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and respiratory disorders.1

Although the majority of older adults have one or more chronic conditions, most older adults view their health positively. Approximately 72% of older adults living in the community describe their general health as excellent, very good, or good.1 Little difference exists in perception of health between men and women; however, positive health evaluations decline with age.1

HEALTH PROMOTION AND AGING

The increase in numbers and proportion of older adults within the population has coincided with a shifting of priorities to a wellness perspective in health for both consumers and professionals.2 For the past two decades, efforts to increase the overall health of the nation have been addressed through the Healthy People 2010 initiatives.3 The health status indicators and focus areas in the Healthy People 2010 report provide a concrete baseline from which to plan programs, set priorities, and evaluate progress in meeting health objectives and increasing health status.

On the positive side, research indicates that older adults, on average, take better care of their health than does the general population. Individuals of 65-plus years are less likely than younger adults to drink alcohol, be overweight, smoke, or report that stress has adversely affected their health.3 The lower rates of drinking alcohol and smoking can be attributed to the tendency toward discontinuing these habits in older age, whether done spontaneously or in response to a medical condition or advice, and to the higher mortality rates of those who were drinkers or smokers at younger ages.4

Older adults, however, are less likely to engage in regular physical exercise. Inactivity poses serious health hazards to both young and old. Lack of exercise can lead to coronary artery disease, hypertension, obesity, tension, chronic fatigue, premature aging, poor musculature, osteoporosis, and inadequate flexibility. Many older adults, and younger adults also, believe that aged individuals are too old to begin or participate in a fitness program; however, research indicates that even those with chronic conditions can benefit from an appropriately designed fitness program.3

The dental hygienist as an educator and health promoter can provide appropriate wellness information and reinforce positive lifestyle habits of older clients, thus facilitating the human need for responsibility for oral health, prevention of health risks, and a wholesome facial image.

ORAL CONDITIONS IN THE AGED

As with other physiologic alterations in the body, the distinction between age-related oral changes and those that are disease-induced is not always clear or conclusive.4,5 Disease, consequences of disease, and use of medications often manifest oral changes and pathology independent of the aging process. In the last century, perhaps the most significant change in older adults’ oral status is the decline in edentulousness (total tooth loss). National data show that although 55% of the 65- to 74-year-olds were edentulous in 1957 and 1958, the proportion had decreased to approximately 40% in 1985 and 1986 and to 30% in 1997.3 Changes in treatment philosophies (restore rather than extract), improved treatment modalities, and advances in prevention have played a significant role in reducing tooth loss among older adults, especially the young-old, although significant disparities exist among the current group of older adults, with higher rates of edentulousness seen in low-income individuals (48%).3 It is expected that the rate of edentulousness will probably continue to decline for future cohorts of older adults. Within the focus area of oral health, the Healthy People 2010 document has identified the target goal of reducing the rate of edentulous older adults to 20% of the population.

Dental Changes

Age-Related Changes

With age, teeth undergo several changes, including alterations in the enamel, cementum, dentin, and pulp. Enamel becomes darker in color because of lifetime consumption of stain-producing foods and drink and the formation of secondary dentin. The enamel surface develops numerous cracks (acquired lamellae) and obtains a translucent appearance. The enamel surface has calcium and phosphate constantly demineralized and remineralized during the caries process. During demineralization, the surface appears clinically dull, with slight exploration revealing a chalky surface. Arrested dental caries in older adults often appear as a brownish-black discoloration because of lifelong uptake of stain in enamel lamellae.5

Cementum undergoes compositional changes, including an increased fluoride and magnesium content, as individuals age. Abrasion of the crowns of teeth is compensated for by deposition of cementum at the apical end and bifurcated areas of the roots. This secondary cementum is normally deposited slowly and continuously throughout life.5

Two independent changes are found within the dentin: secondary dentin formation, and obturation of dentinal tubules (dentin sclerosis). As a result, the vitality of the dentin is greatly decreased, and aged dentin may become entirely insensitive and impermeable.5

The pulp undergoes the same changes that occur in similar tissues elsewhere in the body: pulpal blood supply decreases, the number of cells decreases, and the number of fibers increases in aged adults. Because pulp calcifications increase with advancing age, the size of the pulp chamber is reduced. Pulp calcifications appear to form in both erupted and unerupted teeth.

Attrition is common along the incisal and occlusal surfaces as a result of a lifetime of wear, habits, and dietary factors. Occlusal attrition often smoothes the occlusal area, which reduces microbial accumulation in the fissure. These fissures may appear slightly sticky on probing, but they may not need restoring. Therefore vigorous exploring must be avoided in order not to mechanically damage the porous part of the fissure enamel. The attrition present in older individuals is often so severe that dentin is exposed on the incisal and occlusal surfaces.

Many of today’s older adults may have used a stiff toothbrush and abrasive toothpaste in the past. Consequently, tooth abrasion, especially in the cervical area and on root surfaces, may be evident. Abrasion, although common among older adults, is the result of a physiochemical process rather than a result of aging. Although modern dentifrices are not sufficiently abrasive to severely damage intact enamel, they can cause remarkable wear of cementum and dentin if the toothbrush is used in a horizontal rather than vertical direction.5,6 Dental hygienists can assist individuals in maintaining a biologically sound dentition and freedom from pain through appropriate oral hygiene educational instructions.

Pathology-Induced Changes

Both coronal and root caries are active in the older adult population. Dental caries were once considered primarily a childhood phenomenon, but research suggests that older adults are more likely to develop new coronal and root caries at a greater rate than the younger population.4-7 For example, although 30% of adults aged 18 to 64 had at least one area of untreated decay, 37% of dentate older adults aged 65 to 74 had at least one area of root decay, and 49% of adults 75 years of age or older had at least one area of root decay.3

Root caries are most prevalent among older populations because of both local oral factors and factors related to aging. Local factors include exposed root surfaces and tooth longevity, and factors related to aging include changes in salivary quantity and composition and inability to complete thorough oral hygiene because of disabilities and chronic conditions. The presence of root caries often indicates disruptions in multiple systems rather than just local factors and requires a multidisciplinary perspective by oral healthcare providers.6,7 Predictors of caries include the presence of elevated amounts of caries-related bacteria (i.e., Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli), presence of plaque biofilm, presence of restored coronal and root decay, xerostomia, and gingival recession.7 Root caries can develop rapidly in the absence of inadequate oral hygiene and in the presence of xerostomia, suboptimal periodontal health, and ingestion of fermentable carbohydrates.

Caries control and prevention activities must address three interrelated factors: (1) use of topical fluoride, amorphous calcium phosphate, antibacterial agents, and/or salivary replacement therapy, (2) mechanical removal and chemical control of plaque biofilm, and (3) reduction of refined carbohydrates.6,7 Oral hygiene activities are often compromised in older adults because of sensory and neuromuscular changes as a result of aging and/or disease. Use of adaptive devices, such as power toothbrushes and modifications in toothbrush handle size, width, and grip, will provide assistance for older adults in thorough plaque removal. Poor dietary practices involving the overconsumption of soft, retentive refined carbohydrates and frequent snacking are often common among older adults and are complicated by salivary changes that promote dental decay.6,7

Aggressive caries prevention and management must include risk assessment, and frequent and liberal use of topical fluoride products for both home use and professional application. In addition to the use of a fluoridated toothpaste, many older adults find 0.05% sodium fluoride rinses easy to use and helpful in caries reduction. Many older adults have difficulty swallowing, however, and prefer the use of the 1.1% sodium or 0.4% stannous fluoride gel, which can be applied directly to the root surfaces and adapted into the proximal surfaces with a toothbrush or small interproximal brush.6,7 Professionally applied sodium fluoride in either the 2.0% gel or 5.0% varnish has been shown to be an effective caries-preventive agent for both coronal and root caries7 (see Chapter 16).

Periodontal Changes

Age-Related Changes

There is an increase in alveolar bone porosity and a decrease in cortical width with aging, but this increased porosity has been found to be unrelated to the presence of teeth and does not lead to crestal resorption. Research shows that crestal bone loss with aging is minimal in healthy persons.4 Osteoporosis primarily effects decreases in bone mass and increases in porosity.8 Also, a reduction in metabolism and reduced healing capacities can influence the quality of bone. Alveolar bone quality can significantly affect the older adult’s ability to wear oral prosthetics and achieve proper mastication.

Gingival epithelium reportedly shows no significant morphologic changes with age, although there is evidence of a thinning of the epithelium, diminished keratinization, and increased cellular density. A reduction in cellular elements and an increase in fibrous intercellular substance have been noted in gingival connective tissue. A reduced number of nerves in the gingiva and increased evidence of nerve degeneration with increasing age have been found, along with arteriosclerotic changes in gingival vessels. An increase in gingival width seen with aging has been attributed to growth of the alveolar process, along with eruptive movements of the teeth and supporting tissue.4,5

Alteration in periodontal ligament cellular function, increases in calcification, and arteriosclerosis are seen with advancing age. Numerous morphologic, biochemical, and metabolic changes can be observed in the periodontium with aging, but the overall significance of these factors as they affect susceptibility and periodontal disease progression is unclear. It appears, however, that in the absence of disease the clinical changes in the periodontal structures attributable to aging alone are therapeutically insignificant.

Pathology-Induced Changes

Advanced stages of periodontal disease are more commonly seen in people 45 years of age or older; age is often erroneously thought to cause the disease. Research indicates that the effect of age on the progression of periodontitis is negligible when good oral hygiene is maintained and risk factors are decreased. Nevertheless, studies confirm an association between increased age and increased recession, loss of attachment, and higher prevalence of gingival inflammation.3-5

The level of periodontal health in middle age can be used as a predictor of periodontal disease in later life.5 Data suggest that the prevalence and severity of periodontal diseases will likely decrease within a few decades as the present younger age groups, with better oral hygiene and less periodontal disease, move into their sixties and seventies. National studies document this decline because the National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHANES III) found that only 15% of the population has advanced periodontal disease. Among persons age 65 or older, however, 41% had at least one site with significant periodontal destruction.3

Dental hygienists should provide aggressive treatment to prevent and control periodontal diseases in older adults. More-frequent dental hygiene care visits provide the opportunity to instruct the older adult in proper oral hygiene, especially in the use of powered toothbrushes, and also in the use of chemotherapeutic agents to control gingivitis, such as triclosan dentifrice and/or essential oil mouth rinse. Prescription of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate may also be indicated for older clients who need an additional level of microbial control.5,6

Oral Mucosal Changes

Age-Related Changes

In the absence of disease the oral mucosal status of older adults is comparable to that of younger adults, suggesting that aging alone does not lead to changes in the oral mucosa.5

Pathology-Induced Changes

Some mucosal alterations are a result of systemic factors (e.g., xerostomia) and are not related to aging. Systemic disease and medication use cause some older adults to have changes in their oral mucosa, including atrophy of epithelium and connective tissues with a decrease in vascularity. Clinically the oral mucosa appears dry, smooth, and thin. Fungal infections (candidiasis) may result from use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as amoxicillin, and xerostomia-causing medications.8-10

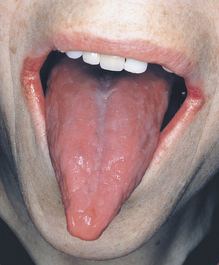

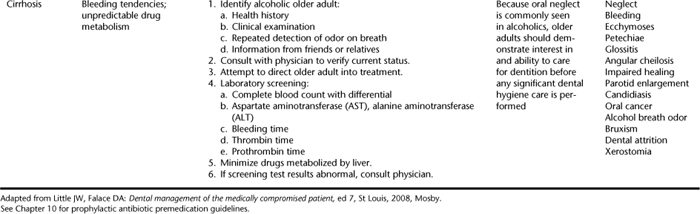

Lips may appear dry and drawn as a result of dehydration and loss of elasticity within the tissues. Angular cheilitis, commonly evidenced among the aged, clinically appears as fissuring at the angles of the mouth, with cracks, erythema, and ulcerations. Moistness from drooling, deficiency of vitamin B2 (riboflavin), and infection with Candida albicans are the causative factors associated with this condition8-10 (Figure 54-2).

Figure 54-2 Angular cheilitis.

(From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

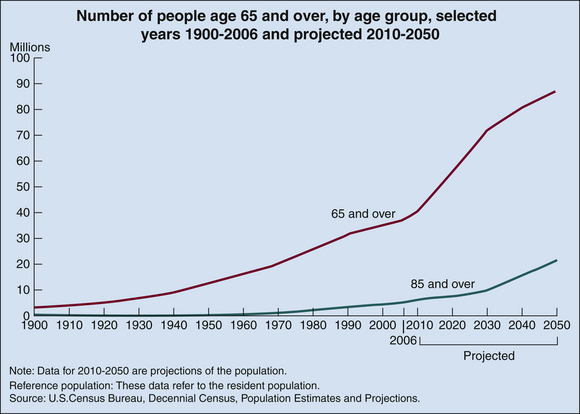

Ill-fitting dentures or poor denture hygiene also can result in mucosal irritation and infection, including denture stomatitis or candidiasis and denture-induced fibrous hyperplasia. Denture “sore mouth” reflects a commonly seen condition also known as chronic atrophic candidiasis, present in as many as 65% of older individuals who wear dentures. Chronic atrophic candidiasis is associated with poor prosthesis fit, which leads to chronic trauma, and retention of the denture during sleeping hours, which promotes bacterial and fungal growth. The signs of denture-induced fibrous hyperplasia include single or multiple elongated folds near the border of an ill-fitting denture8,10 (Figure 54-3; see Chapter 55).

Figure 54-3 Denture-induced fibrous hyperplasia. A, With denture. B, Without denture.

(From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

The human need for skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck necessitates that the dental hygienist provide palliative treatment and refer the individual to the dentist for further evaluation.

Oral cancer continues to be a particular problem for older adults because the average age of diagnosis is 60 years. Oral cancer is more common in men than in women and represents about 2.5% of the total cancers diagnosed each year.8-10 All older adults should receive a thorough soft-tissue oral examination at each visit so that the dental hygienist can carefully evaluate any early mucosal changes that may indicate precancerous or cancerous lesions and provide early referrals for prompt evaluation and treatment.

Tongue Changes

Age-Related Changes

Changes in the tongue may include a decrease in the number and sensitivity of papillae. Combined with a decline in the sense of smell, some foods have less appeal, and nutritional needs may not be met. Sublingual varicosities are customary findings among the aged; however, they are not problematic. Clinically they appear as deep red or bluish-black dilated vessels on either side of the midline on the ventral surface of the tongue.

Pathology-Induced Changes

Because of nutritional factors, older adults frequently have anemia as a result of iron deficiencies. Atrophic glossitis is a symptom of this condition, and the tongue appears smooth, shiny, and denuded. Often, individuals complain of a burning sensation. In addition, the tongue often increases in size in edentulous mouths or as a result of disease (e.g., pernicious anemia)8-10 (Figure 54-4). The dental hygienist can assist the individual by recommending an oral lubricant to reduce discomfort and by providing dietary counseling.

Salivary Gland Changes

Research has shown that reductions in salivary flow are not a result of the normal aging process. Rather, decreases in salivary flow are usually attributed to systemic disease, radiation therapy, tumors, or medications that cause temporary or permanent xerostomia.8-10 Signs and symptoms of salivary reduction should be carefully evaluated to determine the cause. In the absence of medications, possible underlying diseases and salivary gland tumors should be investigated.

Sjögren’s Syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disorder of the salivary glands occurring most frequently in postmenopausal women. Approximately 60% of people with this disorder are older than 50 years. Clinically the oral mucosa is extremely dry and saliva is ropy. Initially the tongue shows marked atrophy of the papillae, and later the surface becomes smooth and lobulated8-10 (see Chapter 47, Figure 47-10). To meet the need for mucous membrane integrity, persons with Sjögren’s syndrome should be instructed to use saliva substitutes and products for dry mouth. For dentate individuals, fluoride therapies (rinses or daily gels) may be recommended to help meet the need for a sound dentition.8

Drug-Induced Oral Changes

Approximately one third of all prescription and over-the-counter drugs are used by older adults, even though these individuals account for only 13% of the population. Polypharmacy is the term to describe the common practice of prescribing multiple drugs to clients to manage their many medical conditions.8,9 On average, most older adults take more than three therapeutic agents, and the institutionalized elderly use five to seven drugs at the same time. Older clients are more likely to experience adverse reactions because of physiologic changes in the heart, liver, and kidney and also because of the increased exposure and potential for interaction of both prescription and over-the-counter medications. Medications most frequently used by older adults include analgesics, diuretics, oral hypoglycemics, antihypertensives, antidepressants, and sedatives. Multiple medical problems, along with multiple drug use, can lead to a high rate of adverse drug reactions. Many drugs produce oral changes in the mouth because of side effects or as a consequence of the actions of the drug.8,9 Dental hygienists play an especially important role in identifying medication usage and potential side effects (see Chapter 12).

Xerostomia

Xerostomia is a common side effect of many prescription and over-the-counter medications, such as antihypertensives, antipsychotics, antidepressives, muscle relaxants, antihistamines, and laxatives. Saliva plays an important role in proper function of the oral cavity because it lubricates the oral mucosa, assisting speech and swallowing, facilitates the retention of oral appliances, and provides a source of minerals for enamel remineralization8,9 Diminished salivary flow can alter taste, contribute to plaque formation and dental caries, and cause the oral mucosa to appear dry and inflamed. For edentulous persons, denture retention, comfort, and ability to chew and speak may become difficult when less saliva is present.

Management of xerostomia should include palliative care through the use of saliva substitutes, oral lubricants, mouth rinses, and frequent water intake. Attempts to stimulate salivary flow can include the use of xylitol- containing oral care products, candies, or gum, and medications such as the cholinergic agents pilocarpine and bethanechol. Also, consultation with the physician and clinical pharmacist may reveal a substitute medication that may reduce saliva in a less-severe way for the client.

Clients with xerostomia should return for frequent recall and assessment of caries status. Aggressive caries-prevention efforts should be recommended because the presence of xerostomia places the client in an extreme risk category for caries (see Chapters 16 and 55). All of the following caries-prevention efforts are essential for the older adult in order to control root and coronal caries associated with xerostomia6,7:

Drug-Induced Gingival Enlargement

Persons taking anticonvulsants such as phenytoin may exhibit gingival hyperplasia as a side effect.8,9 Adequate plaque control, particularly if started before the administration of phenytoin, may reduce the magnitude of gingival enlargement. Also, clients with prescribed cardiovascular drugs (nifedipine) and immunosuppressants (cyclosporine) may exhibit gingival enlargement.8,9

DENTAL HYGIENE PROCESS OF CARE WITH OLDER ADULTS

Assessment and Dental Hygiene Diagnoses

Dental hygienists begin their assessment of overall physical factors by observing the older adult in the reception area.5,8,9 It is important to observe gait and balance because some elderly persons may require assistance to the treatment area. An arm should be extended for clients who appear unsteady or who have severe visual impairments. The dental chair should be positioned at the level of the knees or higher if the person has difficulty bending the knees. Also, the arm of the chair should be placed back as far as possible. If the client uses a wheelchair, transfer to the dental chair is necessary. The client should be asked if assistance is needed or which method of wheelchair transfer is preferred (see Chapter 41).

Impairments in both vision and hearing commonly seen in older adults may necessitate providing assistance in completing any written forms in the office.5,8 A health history form in large print allows visually impaired clients to complete the form themselves. At times it may be more effective and efficient to interview older clients. The person should be addressed in a low pitch with the face mask removed. Shouting is unnecessary and ineffective. Background noises such as music should be eliminated if possible. Individuals with hearing aids should be requested to keep them on while the client history is reviewed or oral hygiene methods are discussed; however, the volume should be reduced when a rotary handpiece is used. Older adults accompanied by others should be addressed directly, not the family member or caregiver. By speaking directly to the elderly client, dental hygienists create a respectful, independent environment.5,8

The health history should include the client’s personal, medical, and dental background. Personal history, for example, may show that clients are widowed (may live alone, may have reduced income), which could affect their ability to receive dental care. The health history should include previous and past medical conditions. Both prescription and over-the-counter medications currently being used must be reviewed for oral implications. Dental hygienists should have readily available a current source for information on medications, such as a reference program, book, or credible website to investigate medications that are unfamiliar or not prescribed as the common drug of choice. Some individuals with more than one disease may experience adverse effects from multiple drug use. The practitioner must consult with the client’s physician if there is doubt regarding treatment. Vital signs, including respiration, pulse, blood pressure, and temperature (if indicated), should be evaluated and recorded. In addition to completing a thorough health history, the practitioner should be patient and listen to information that the client shares.

The extraoral examination can reveal abnormalities in the skin of the face and neck, lymph nodes, salivary glands, and underlying muscles.8 The mandible is examined for movement, and the temporomandibular joint should be palpated for crepitation, tenderness, or limitations in movement. A client with arthritis may not be able to open his or her mouth fully.

Lips are evaluated for signs of angular cheilitis, muscle inelasticity, and presence of lesions. A complete dental charting and periodontal assessment are part of every dental history to provide documentation for reevaluation. The quantity and quality of saliva is assessed to ascertain if saliva substitutes should be recommended (see Chapter 16).

Radiographs and other diagnostic aids such as study models are used as indicated and appropriate. Referral for biopsy may be indicated for suspicious lesions.

Oral hygiene status including plaque biofilm distribution, calculus, and stains is assessed. Assessment of the client’s ability to perform oral hygiene practices is essential. The older person’s homecare practices should generally be modified rather than attempts made to completely change long-term habits. Physical changes such as arthritis and impaired vision may affect the client’s ability to carry out oral hygiene recommendations.

If the client’s vision and dexterity permit, he or she is instructed to perform self-assessments of plaque-control methods and oral soft-tissue examination. Periodic evaluation of bacterial plaque-control measures can be accomplished by using disclosing solution or gingival and plaque indices. Individuals are advised to conduct an oral self-examination monthly to look for lesions that are painless and do not heal within 2 weeks.

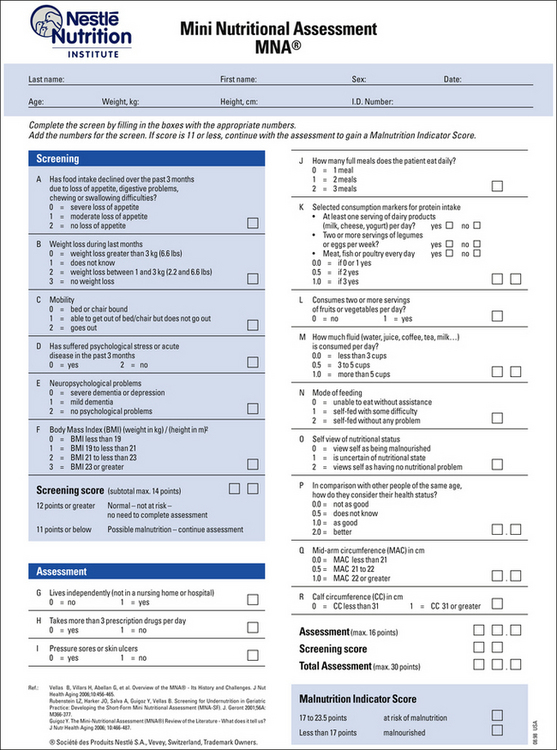

The older client’s nutritional status should be evaluated because of the many physiologic and psychosocial complexities that have been documented regarding dietary patterns for the elderly11 (see Chapter 33). Dental hygienists can use the brief nutritional screening questionnaire “Mini Nutritional Assessment” (Figure 54-5) as part of the health history information; this questionnaire alerts oral healthcare providers to any deficiencies in food intake and related patterns that affect oral health and nutrition. For example, older adults may avoid eating nutritious foods because of decreased oral function or because they are unable or unwilling to cook a full meal because they live alone or cannot shop at the usual location. Merely asking an older adult to describe his or her typical diet often sheds light on multiple issues that affect nutrition and health.11

Figure 54-5 Mini Nutritional Assessment questionnaire.

(Copyright 2006 Nestle USA, Inc, Glendale, California.)

Dental hygienists plan and implement care based on the dental hygiene diagnosis, type and severity of chronic conditions, cognitive abilities and attitudes of the older adult, level of self-care, expectations, and financial ability. Table 54-3 is a presentation of dental hygiene diagnoses related to the older adult. Short morning appointments are recommended because many older adults have a lower stress tolerance and tire more easily than younger people. A written note of date and time of each appointment should be provided to help remind the client and assist caregivers when necessary.

TABLE 54-3 Sample Dental Hygiene Diagnoses Related to the Older Adult

| Deficit in the Following Human Need | Due to | As Evidenced by |

|---|---|---|

| Wholesome facial image | Ill-fitting dentures | Client’s self-report of dissatisfaction with appearance of face and dentures |

| Freedom from fear and stress | Previous negative dental experiences | Client’s report of fear of dentist |

| Freedom from head and neck pain | Chronic atrophic candidiasis | Client’s report of mouth soreness |

| Protection from health risks | Type 2 diabetes | Client’s report of type 2 diabetes |

| Responsibility for oral health | Inadequate care of mouth and dentures | |

| Conceptualization and problem solving | Lack of proper denture and mouth care | Inability to describe appropriate care for mouth and dentures |

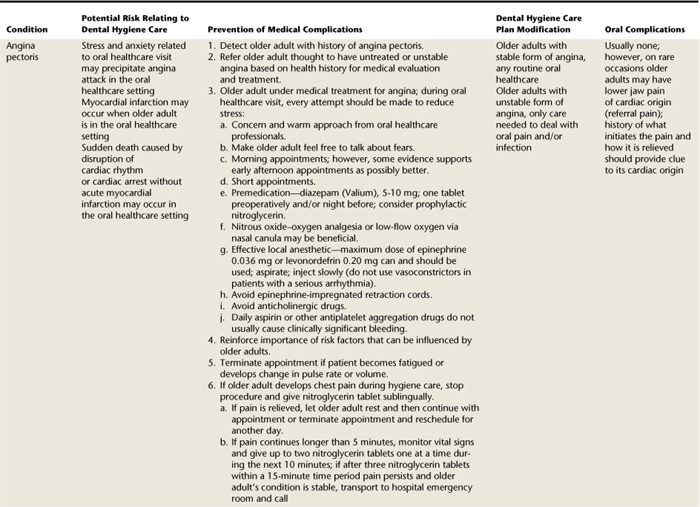

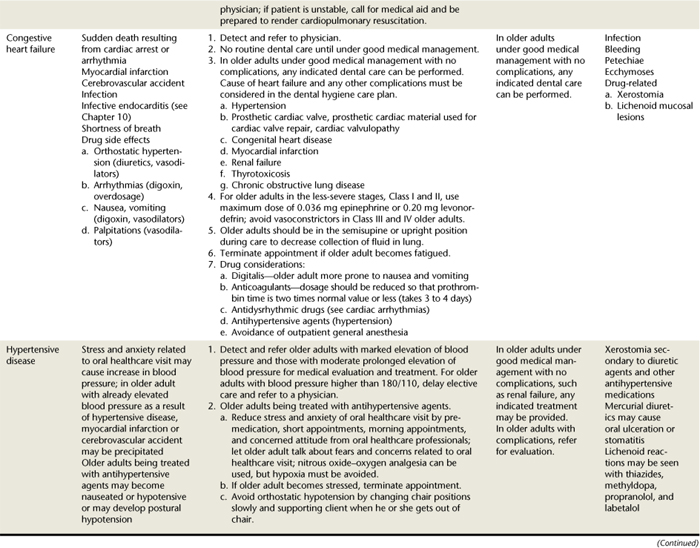

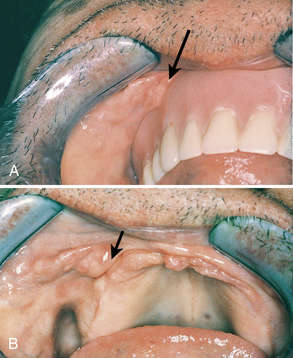

Planning

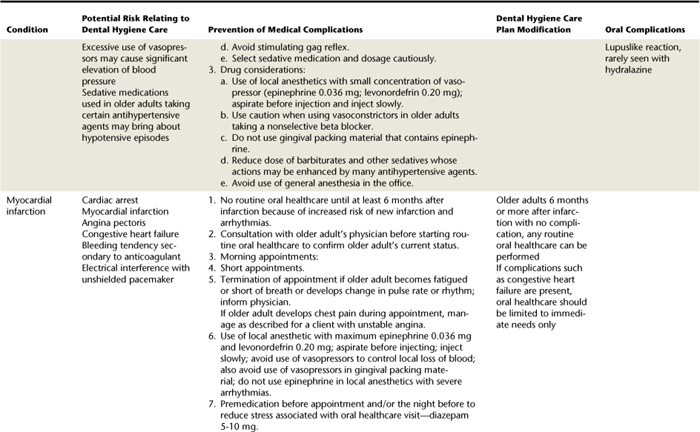

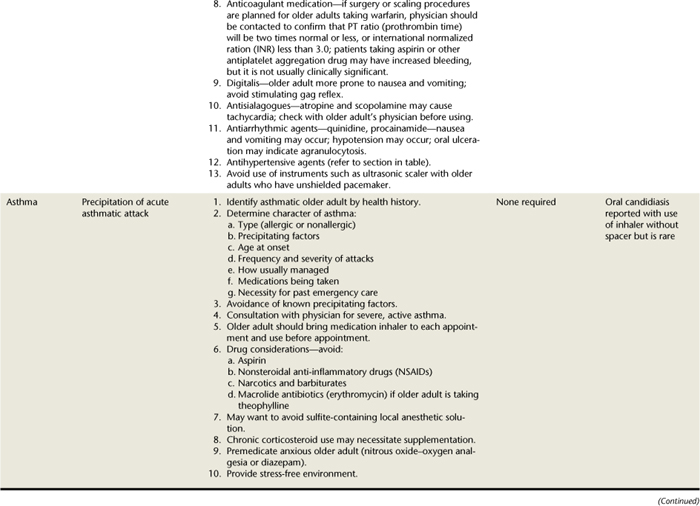

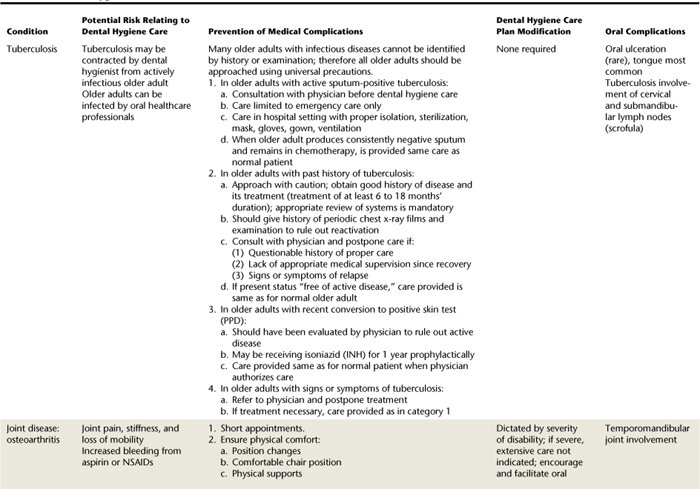

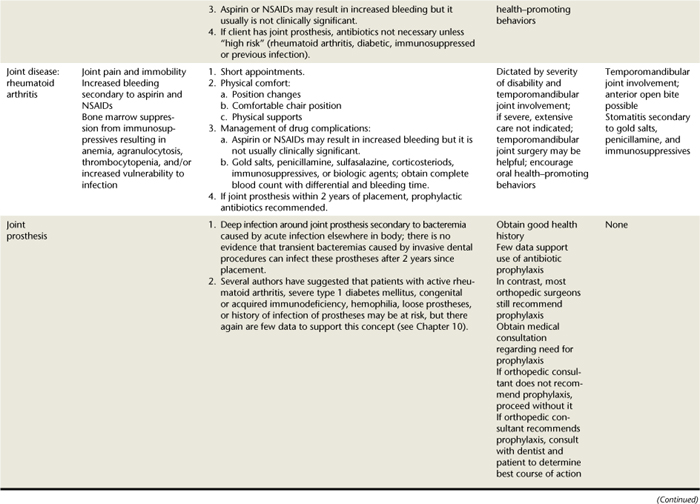

Dental hygiene care planning for older adults is often more complex than for younger persons because the vast majority have at least one chronic condition, and many have complex dental and periodontal conditions.5 Also, normal aging alterations may create a compromised oral situation. Treatment modalities need to be developed based on individual considerations among the client, dental hygienist, dentist, and at times the physician and physical and occupational therapists. Table 54-4 provides a general summary of alterations often required in dental hygiene care of older individuals based on common medical conditions.8-10 This summary table will help dental hygienists consider and adapt care customized for the client’s medical, dental, and psychosocial needs.

Both the individual’s and his or her family’s attitudes toward oral health affects care planning and outcomes. Many older adults view oral problems as an inevitable part of aging. Also, research suggests that older people perceive a lower need for dental care than what is actually required. In addition, cost of care for many is a barrier. Therefore some older adults do not use dental services as frequently as recommended or do so only when dental emergencies occur.3

Implementation

During instrumentation, as little trauma as possible to the gingiva is required because of reduction in healing capabilities. Loss of elasticity of lips and oral mucosa and xerostomia may make retraction of oral tissues uncomfortable. Older adults with a history of periodontal disease need to be seen for more-frequent periodontal maintenance therapy. Depending on the periodontal classification, scaling should be completed by quadrants to allow for short appointment times. Individuals who receive antibiotic premedication need to have as much care as possible at one time; however, the person’s medical condition may make lengthy appointments difficult.

Specific and customized oral hygiene instruction is provided to older adults to ensure that they have the knowledge and skills necessary to thoroughly removal plaque biofilm. Chemotherapeutic products, such as triclosan dentifrice, essential oil mouth rinse, or 0.12% chlorhexidine mouth rinse, should be recommended when necessary to supplement mechanical plaque biofilm removal.6 Recommendations for improving the adequacy of the diet with regard to food choices are provided, with specific directions for limiting refined carbohydrate foods and limiting cariogenic snacking.11

Home use of topical fluoride products has been advocated for all older individuals with teeth. In addition to using a fluoride dentifrice, clients can use a daily nonprescription 0.05% sodium fluoride rinse, especially if they notice decreased quality and quantity of saliva. Many older clients have difficulty rinsing their mouths, however, and a 1.1% sodium fluoride or 0.4% stannous fluoride gel, which is applied by a toothbrush, may be easier to use and may reach susceptible proximal and root surfaces. Clients who have undergone head and neck radiation therapy, who have severe xerostomia, or who have rampant caries can use the tray method to apply the 1.1% sodium fluoride or 0.4% stannous gel in a tray for 5 minutes twice a day. The tray method of application is best completed with an unflavored fluoride product because of the frequency and intensity of the application.6,7

For individuals with xerostomia, calcium and phosphate products (e.g., MI Paste, NovaMin) along with self-applied and professionally applied topical fluoride are recommended to promote remineralization. Saliva substitutes that coat the mucosa and teeth to keep them moist are recommended to reduce enamel solubility and the accumulation of plaque biofilm. Saliva substitutes can be used without limit on the frequency of use and come in liquid, gel, or spray formulations that are distributed through the mouth with the tongue. Several over-the-counter products are available, with many containing fluoride and xylitol.6,7

Exposed root surfaces are susceptible to dental caries, and both professionally applied and home-applied topical fluoride products are recommended to help meet the need for a biologically sound dentition. The role of plaque biofilm and diet in relation to dental caries formation needs to be stressed. A desensitization treatment and dentifrice also may be recommended to help ensure freedom from pain if root surfaces are sensitive.7

At the completion of the appointment, dental hygienists should return the dental chair to an upright position slowly. It is important to allow the client to sit up for a short time before dismissal to avoid any problems with postural hypotension. The dental hygienist should pay close attention to see if the client needs assistance out of the chair. Postoperative instructions are reviewed and a written copy provided as indicated.

Evaluation

After care has been completed, older clients need to be reevaluated more frequently and more carefully because of the many physiologic changes, chronic conditions, and pathologic changes frequently seen in this age group. Dental hygienists need to be aware that health status can change quickly with an older client, and even small changes may be significant, especially in relation to cardiovascular and cognitive changes. Often a dental hygienist may be the first to notice cognitive declines over a series of appointments or at the recall visit. These qualitative perceptions that “something is not quite right” about the older client need to be discussed with the client, relatives, and/or caregivers, and referrals for further medical evaluation provided.5

Dental hygienists should allow a longer time to assess results of soft-tissue debridement because of both a slower and decreased potential for tissue healing, and provide additional care when necessary. Quantitative evaluation of health status through bleeding and plaque indices and pocket depth recording is essential to document healing and plan new interventions with older clients.

More-frequent maintenance intervals are recommended for older clients to evaluate any changes in functional abilities to complete oral hygiene, any nutritional changes, and the occurrence of new disease. Dental hygienists should not assume that older adults continue to have the same functional abilities, even after a 3-month period. For example, clients with musculoskeletal disorders frequently note varying functional abilities and may need more assistance with oral hygiene at times. In addition, clients may be taking new medications and may alter their nutritional patterns because of the unpleasant taste or increased xerostomia experienced with a different medication. These older adults are at extreme risk for caries and need more-aggressive caries management (see Chapter 16). More-frequent visits for dental hygiene care provide opportunity for assessment and to recommend preventive and therapeutic interventions specific to the client’s needs.5,6

COMMUNITY HEALTH SERVICES

Institutionalized elderly comprise approximately 4.4% of the elderly population. Homebound, semidependent elderly account for another 5% to 6%. The numbers may be small, but these groups of elderly have the greatest oral needs and the most difficulty reaching dental services.1,3,5 Individuals who are functionally dependent are more likely to be edentulous and may not have used dental services for several years. Furthermore, research suggests that more than 80% have dental needs, with nearly 40% requiring immediate attention.3,5 Among dentate individuals, three fourths need scaling and selective polishing and have other problems including root caries and poor oral hygiene.3,5

Several factors can be identified that have created this neglect. First, individuals who are in a long-term care facility (LTCF) or are homebound may not be able to care for themselves. They may have numerous complicated and interrelated problems, and dental care may not be a priority. In addition, dental professionals have not been active in providing services because of their own attitudes toward treating the frail elderly, low financial return, and state practice acts that limit dental hygienists’ ability to work unsupervised in LTCFs or with the homebound.3,5,12

The homebound elderly have additional health problems that complicate their care. Some have malnutrition, withdraw socially, or perceive that their speech is adversely affected. These factors can elicit low self-esteem, leading to depression. Problems of not eating and withdrawal can be exacerbated as a result.3,5,12

For older adults, provision of routine dental services is not included under Medicare (federal) benefits. Medicaid (state) dental benefits and eligibility vary by state; however, preventive dental care for elderly is usually not a priority. Given the high dental needs of homebound or institutionalized elderly, systems to provide care need to be advocated for and established.3,5,12

Traditional Dental Office

When dental hygienists treat frail elderly persons, care is complicated by a variety of factors as follows5,8,12:

Appointment time. Short morning appointments should be scheduled. Most elderly are physically strongest in the morning. Because many cannot sit for long periods, however, 2 hours should be the limit, including transportation time.

Appointment time. Short morning appointments should be scheduled. Most elderly are physically strongest in the morning. Because many cannot sit for long periods, however, 2 hours should be the limit, including transportation time. Accessibility of the dental office. Parking lots, ramps, and doorways must accommodate wheelchairs. Legally, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1993 mandates access to all public facilities.

Accessibility of the dental office. Parking lots, ramps, and doorways must accommodate wheelchairs. Legally, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1993 mandates access to all public facilities. Communication with the LTCF. Most facilities require that services provided and instructions be in writing.

Communication with the LTCF. Most facilities require that services provided and instructions be in writing.On-Site Dental Programs

Providing care in an LTCF or client’s home has several advantages over the traditional dental office, as follows:

There are three options that dental professionals can use when providing care in an LTCF or to homebound clients. Many facilities will have space to build dental operatories, which may be more common in a larger LTCF and provides a more-comfortable permanent arrangement for dental professionals and clients. However, for smaller LTCFs, dedicated permanent space may not be available. Portable dental equipment, including dental chairs, delivery systems, and x-ray equipment, can be readily transported and set up in a conference room or other space so that dental care can be provided as needed for clients. Alternatively, mobile dental vehicles can be deployed when space in the facility cannot be provided. Mobile vehicles are “dental offices on wheels” and can be customized with dental laboratories and other amenities to customize care with older adults. However the care is provided, it is important to educate the family and/or caregivers about appropriate follow-up care to dental treatment and also about daily, routine oral hygiene care for the client.12

Role of the Dental Hygienist

Dental hygienists serve in an important capacity with the institutionalized and homebound elderly in the following activities:

Providing clinical dental hygiene care either at the LTCF or when the client is transported to the dental office

Providing clinical dental hygiene care either at the LTCF or when the client is transported to the dental officeNursing staff and aides are important intermediaries for oral healthcare professionals.12 Staff members should be encouraged to refer elderly individuals to the dental office or consulting dentist if they detect unusual signs, such as swelling or discoloration, or if they hear a verbal complaint. The Brief Oral Health Status Examination (BOHSE) can be used by nursing staff members to systematically evaluate oral health of clients at entrance to the care facility and routinely during care.12 Dental hygienists can develop and implement in-service education programs to ensure that staff members have the knowledge and skill necessary to complete thorough oral assessments and oral hygiene care.

For homebound individuals, establishment of a prevention program using visiting nurses or home healthcare workers is needed when family members are not available. Some states have developed dental programs that use mobile vans, with both professionals and students providing services for homebound elderly. Dental hygienists can collaborate with local agencies, dental and dental hygiene associations, and dental hygiene educational institutions to develop oral screening, referral, and preventive programs for homebound elderly.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Provide nutritional counseling regarding the reduction of refined carbohydrates, limitation of cariogenic snacking, and adequacy of dietary intake.

Provide nutritional counseling regarding the reduction of refined carbohydrates, limitation of cariogenic snacking, and adequacy of dietary intake.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Complete and document a thorough medical, personal, and dental history and oral examination with each client.

Complete and document a thorough medical, personal, and dental history and oral examination with each client. Evaluate the client’s use of medications, and refer client to the physician for consultation when indicated.

Evaluate the client’s use of medications, and refer client to the physician for consultation when indicated. Explain the results of consultation with the older adult, and document conversations and the physician’s recommendations in the client’s chart.

Explain the results of consultation with the older adult, and document conversations and the physician’s recommendations in the client’s chart. Provide and document informed consent with all older clients. When necessary, discuss and document treatment with family and/or caregivers.

Provide and document informed consent with all older clients. When necessary, discuss and document treatment with family and/or caregivers. Provide written instruction that can be easily read by older clients and/or caregivers, and reinforce instructions verbally.

Provide written instruction that can be easily read by older clients and/or caregivers, and reinforce instructions verbally.KEY CONCEPTS

Older adults are a heterogeneous group, and there is tremendous variability in the physical, psychosocial, and environmental issues within this age group. Functional age, rather than chronologic age, is the best measure to use when providing care to older adults.

Older adults are a heterogeneous group, and there is tremendous variability in the physical, psychosocial, and environmental issues within this age group. Functional age, rather than chronologic age, is the best measure to use when providing care to older adults. Current demographic reports and projections indicate a significant rise in both the number and the proportion of older adults in the United States.

Current demographic reports and projections indicate a significant rise in both the number and the proportion of older adults in the United States. The older adult population is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. Elderly women outnumber elderly men. Older adults are concentrated in certain states and are not distributed evenly in the population.

The older adult population is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. Elderly women outnumber elderly men. Older adults are concentrated in certain states and are not distributed evenly in the population. There is not one accepted theory to explain how and why we age. Multiple social and biologic theories of aging have been proposed and complement each other to shed light on the aging process.

There is not one accepted theory to explain how and why we age. Multiple social and biologic theories of aging have been proposed and complement each other to shed light on the aging process. There are normal, physiologic changes in most body systems that occur as individuals age. These normal changes should not be confused with pathologic changes caused by disease; however, distinctions between normal aging and pathologic conditions are sometimes difficult to discern.

There are normal, physiologic changes in most body systems that occur as individuals age. These normal changes should not be confused with pathologic changes caused by disease; however, distinctions between normal aging and pathologic conditions are sometimes difficult to discern. Most older adults have at least one chronic condition, and the most common chronic conditions are arthritis, hypertension and heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and stroke.

Most older adults have at least one chronic condition, and the most common chronic conditions are arthritis, hypertension and heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and stroke. Older adults develop coronal and root caries at a rate higher than the adult population; however, the rate of edentulousness (total tooth loss) is estimated at 30% and is projected to continue to decrease in future years.

Older adults develop coronal and root caries at a rate higher than the adult population; however, the rate of edentulousness (total tooth loss) is estimated at 30% and is projected to continue to decrease in future years. Caries prevention and control strategies for older adults must stress daily removal of plaque biofilm, reduction of refined carbohydrates, and daily use of topical fluorides, salivary substitutes, and calcium and phosphate products, especially when xerostomia is present.

Caries prevention and control strategies for older adults must stress daily removal of plaque biofilm, reduction of refined carbohydrates, and daily use of topical fluorides, salivary substitutes, and calcium and phosphate products, especially when xerostomia is present. A small but significant number of older adults have advanced periodontitis, and there is a higher degree of loss of attachment and prevalence of gingivitis among older adults.

A small but significant number of older adults have advanced periodontitis, and there is a higher degree of loss of attachment and prevalence of gingivitis among older adults. Prevention and control of periodontal diseases should include daily removal of plaque biofilm, use of chemotherapeutic agents, and more-frequent visits for professional debridement and evaluation.

Prevention and control of periodontal diseases should include daily removal of plaque biofilm, use of chemotherapeutic agents, and more-frequent visits for professional debridement and evaluation.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

DENTAL HYGIENE CARE FOR AN OLDER CLIENT

Profile: Mrs. F., age 77, returns for a dental hygiene visit on her regular 6-month maintenance schedule.

Chief Complaint: “I have a removable partial denture to replace my lower back teeth that I don’t wear because it makes my mouth feel dry and taste bad. Also, I have a large freckle on my left cheek that has grown in the past several months.”

Social History: Mrs. F. has been widowed for 3 years and is active with her church and the families of her two daughters who live nearby.

Health History: Mrs. F. has a history of angina for the past 6 years and takes 50 mg atenolol (Tenormin) once a day to prevent angina attacks.

Dental History: Mrs. F. has a history of regular dental visits and has all of her teeth, with the exception of the four mandibular molars. Oral examination reveals a flat, brown, elongated lesion approximately 10 mm long and 6 mm wide on the center of her left cheek. Mrs. F. denies any pain or exudate from this lesion. Dental examination reveals no areas of decay and generally recession with no evidence of periodontal disease.

Oral Health Behavior Assessment: Good oral hygiene. Uses a power toothbrush and floss daily.

Supplemental Notes: During dental hygiene care, Mrs. F. states that she thinks her teeth are too short and ugly and asks you if she is too old to get “caps” on her teeth to improve her appearance.

INSTANT AGING AS A DENTAL CLIENT

This activity asks participants to simulate what it is like to be an older dental client in their office. This exercise provides a good opportunity to learn what older clients may be experiencing and provides insight for participants regarding sensory changes in aging. Students should work in groups of two, alternating the role of client and dental hygienist. Partners are asked to complete tasks while they have simulated several sensory deprivations that older individuals may experience.

Task A: Partner 1 wears glasses with a thin film of oil or lubricant to inhibit clear vision. In addition, partner 1 tapes the fingers of both hands to make fine motor tasks difficult. Partner 1 completes a health history form and/or other office forms for a new client. After the forms are completed (a brief time limit should be imposed), partner 1 walks unassisted back to the treatment room and fills out additional forms in the dental chair.

Task B: Partner 2 wears earplugs or uses cotton or wax ear protectors to limit hearing. In addition, this partner uses an ace bandage or shoulder harness to restrict shoulder movement. Partner 2 walks unassisted to the treatment room and completes a brief written form in the dental chair. Partner 2 demonstrates both brushing and flossing technique and should be asked to describe the technique and answer questions about the performance.

Debriefing Discussion: After the simulated dental appointments are completed, participants discuss their experiences in completing routine dental tasks with some sensory impairments. Although this is only a simulation, partners are encouraged to discuss how this simulation is related to the experiences of their older clients. Partners should complete an “environmental audit” of their dental offices to assess how difficult their office environment is for the older individual to negotiate, based on the environmental considerations discussed in this chapter. Hearing, vision, and motor skill impairments pose significant obstacles even when the environment is optimal for older adults. By adopting the perspective of the client with some sensorimotor deficits, partners may be able to identify difficulties for older clients and make changes to provide care in a more sensitive, appropriate manner.

VISIT A SENIOR COMMUNITY CENTER

Most communities provide a variety of services to older adults who are currently living in the community but who may need some assistance with meals, social activities, healthcare, or housing to function in an independent manner for as long as possible.

In this learning activity, readers should contact the director of a local senior center and request to visit and/or volunteer at the center at least twice. Visits to these senior centers provide an interesting window on the daily life of older adults, especially if participants have little experience with older individuals. The centers generally emphasize a philosophy of wellness and provide a wide range of activities to encourage participation by members, such as arts and craft projects, discussion groups, and scheduled trips to social and cultural events.

Students who visit a senior center should keep a diary regarding the activities the seniors completed on the days on which they visited and should participate actively in the events scheduled for the day. For example, learners may wish to volunteer to share a craft activity with the older adults, lead an exercise or dance class, or call bingo for the session. During the visits, the participants should speak with as many seniors as possible to learn of their daily activities, why they participate in the center activities, and which activities and functions of the center they use most frequently. These informal discussions are generally welcomed by the older adults, who view these sessions as a chance to advise and guide younger individuals about the needs of older adults. In addition, these visits provide participants with the opportunity to understand the wide range of abilities these older individuals possess, even in light of chronic and disabling conditions. By observing and sharing activities, participants can view the active and varied nature of the seniors in their daily activities and gain an understanding of the challenges older adults face each day.

1. National Center for Health Statistics: Health, United States, 2006, with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus06.pdf#027. Accessed August 7, 2008.

2. Ebersole P., Touhy T., Hess P., et al. Toward healthy aging: human needs and nursing response, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Healthy People 2010: healthy people in healthy communities. Available at: www.health.gov/healthypeople. Accessed August 7, 2008.

4. Ship J.A. Improving oral health in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1454.

5. Ettinger R.L. The unique oral health needs of an aging population. Dent Clin North Am. 1997;41:633.

6. Erickson L. Oral health promotion and prevention for older adults. Dent Clin North Am. 1997;41:727.

7. Shay K. Root caries in the older patient: significance, prevention and treatment. Dent Clin North Am. 1997;41:763.

8. Ship J.A., Chavez E.M. Management of systemic diseases and chronic impairments in older adults: oral health considerations. Gen Dent. 2000;48:555.

9. Little J.W., Falace D.A., Miller C., et al. Dental management of the medically compromised patient, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

10. Regezi J.A., Sciubba J.J., Miller C., et al. Oral pathology, ed 5. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008.

11. Palmer C.A. Gerodontic nutrition and dietary counseling for prosthodontic patients. Dent Clin North Am. 2003;47:355.

12. O’Connor L.J. Oral health care. In Capezuti E., Zwicker D., Mezey M., et al, editors: Evidence-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice, ed 3, New York: Springer, 2008.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..