CHAPTER 37 Behavioral Management of Dental Fear and Anxiety

One of the primary reasons that many individuals avoid seeking oral healthcare is fear and anxiety. Dental fear is defined as an unpleasant mental, emotional, or physiologic sensation derived from a specific dental-related stimulus. Dental anxiety, on the other hand, is nonspecific unease, apprehension, or negative thoughts about what may happen during an oral healthcare appointment. The source of the unease is often unknown to the individual.

Clinically significant fear is termed phobia. Specific phobia is a persistent fear in which an object or situation is avoided or endured with intense anxiety or interferes with normal routines. Examples of specific phobias in the oral healthcare setting are the sight of the syringe needle and the sound of the dental drill. Dental fear and anxiety may be distinguished from dental phobia by the degree of avoidance. Individuals who are dentally fearful or anxious can cope with the intensity of the feelings they experience and obtain oral healthcare, whereas dental-phobic individuals usually are not able to cope to the degree required to attend appointments. It is estimated that 11% to 20% of adults in the United States avoid regular dental care because of their intense fears. In addition, almost half of the U.S. population reports significant subclinical dental fear, and approximately two thirds experience some degree of apprehension when considering upcoming dental treatment.1 Surveys done in Britain, China, Sweden, Norway, and Australia corroborate these figures as a transcultural phenomenon (see Chapter 5). It is important for the dental hygienist to understand the physiologic, psychologic, and behavioral effects of dental fear and anxiety and to use behavioral techniques for managing fearful and anxious clients.

EFFECTS OF FEAR ON THE BODY

Physiologic Effects

The effects of fear on body physiology evoke the stress response. Stress is a physical and emotional response to a particular situation. Often referred to as the “fight-or-flight” reaction, the stress response occurs automatically when one feels threatened. The threat can be any situation that is perceived—even falsely—as dangerous, so one’s perception is a key issue. When a client perceives a threat, the stress response is initiated in the hypothalamus of the brain. Hypothalamic neurons stimulate the release of a flood of chemicals, including adrenaline (from the adrenal medulla and the sympathetic free nerve endings) and cortisol (from the adrenal cortex), into the bloodstream. These chemicals focus individuals’ concentration, speed their reaction time, and increase their strength and agility. At the same time, heart rate and blood pressure increase as more blood is pumped through the body to enable them to do what is required to adapt and survive. This reaction of the body is called the stress response.2 If the production of these chemicals continues for some time in response to emotional stress (anxiety and fear), various medical complications follow (Box 37-1).2 It is important to note that not all stress is bad. Stress can be positive when it results in energy directed toward growth, action, and positive change. When one has too much stress, however, that lasts too long or is linked with negative experiences, stress can be harmful to one’s health. Prolonged exposure to high-stress situations will eventually cause fatigue and disease as the body tries to maintain the elevated actions of the stress response.2 Studies indicate that clients who are fearful of dental treatment experience elevated blood pressure, heart rate, and salivary cortisol levels immediately before dental checkups and treatment.3

Behavioral Effects

How a person acts during a significant fearful episode is his or her behavioral effect.2 Examples of behavioral effects of fear are impulsiveness, accident proneness, nervous laughter, emotional outbursts, excessive drinking or smoking, and changes in eating habits. For children, behavioral effects are acting out, crying, screaming, and holding on to the parent or guardian. Box 37-2 lists the effects of high stress on one’s behavior.2

Psychologic Effects

Stressful periods cause individuals to feel irritable, guilty, angry, and/or anxious. These effects may also lead to lowered self-esteem, depression, and a feeling of loneliness (Box 37-3).2 Symptoms of stress can also be seen when a person is overly sensitive to constructive criticism. In fearful dental hygiene clients, behavioral and psychologic signs of high stress may add synergistically to physiologic symptoms, and patients may manifest extreme dental fear.3

When individuals are fearful of oral healthcare, regardless of the reason, their pain perception is altered. Although pain perception is not completely understood, researchers are in general agreement that the pain threshold, the point at which an uncomfortable stimulus is perceived as painful, and pain tolerance, the amount of pain that is the most an individual can bear, decrease when an individual is fearful of the treatment. Anxiety not only lowers one’s pain threshold but also may lead to the perception that a normally nonpainful stimulus is painful. If the state of tension is reduced, then the client’s pain threshold is elevated and treatment is tolerated more readily.3

ETIOLOGY OF DENTAL FEAR AND ANXIETY

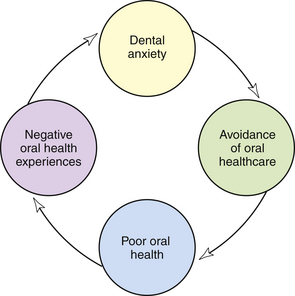

Surveys have shown that 50% to 85% of dental-anxious individuals reported dental fear onset during their childhood or adolescence, and the remainder became fearful of dental care during adulthood.4 Negative dental experiences lead to dental fear regardless of age of onset. Childhood fear onset has been shown to occur in families with a history of dental anxiety. Individuals who became fearful as children are more likely to fear specific dental objects, procedures, and smells.4 Dental fear and anxiety are barriers to good oral health (Figure 37-1). Regardless of the age of onset, dental fear can be learned through a variety of personal and nonpersonal experiences and can be associated with personality traits.5 Box 37-4 lists some common origins of dental fear.6

Figure 37-1 Theoretic model relating dental anxiety, oral healthcare, and oral health.

(From Ronis D: Updating a measure of dental anxiety: reliability, validity, and norms, J Dent Hyg 68:228, 1994.)

BOX 37-4 Common Origins of Dental Fear

Personal Experience

When a child is brought to the dental office for a first appointment, fear of the unknown is an overriding concern. Specific objects and instruments, procedures, smells, and the oral healthcare providers are new and foreign. When the oral healthcare procedures are accomplished, simple physiologic pain may occur, and the child may show behavioral and psychologic signs of fear. Such an experience is an example of learning by direct conditioning, in which a stimulus (pain) produces a response (fear). At a future appointment the child may remember only the fear experienced, rather than attributing the fear to the procedure’s pain.6

In addition, fear of specific stimuli may become generalized from one healthcare setting to all healthcare settings. Both children and adults may have had negative medical experiences that then caused them to fear the dental setting. For example, a hospitalization or emergency room visit may lead an individual to associate injury, pain, and fear with white walls and uniforms. When the fearful child or adult enters the oral healthcare environment (a neutral setting in which the individual has had no previous experience) and finds white walls and a staff dressed in white, the fear learned from the hospital experience comes to the forefront and is generalized to the professional oral healthcare visit. Such a phenomenon is termed stimulus generalization.

The entire realm of oral local anesthesia provokes fear in many individuals—both children and adults. Initially, a procedure that elicits a degree of true pain may become a phobia for some individuals. For example, inadequate anesthesia with previous dental care that caused pain or discomfort may be associated with all professional oral healthcare in the individual’s mind. Also, an incident of adverse reactions to local anesthetics (e.g., pallor, dizziness, nausea, sweating, and fainting) may lead to adverse psychologic reactions when the client is confronted with the thought of future appointments. In addition, rough, uncomfortable injections performed during childhood immunizations may be remembered and generalized to the dental injection.

Moreover, dental fear and anxiety appear to sensitize clients to interactions with the oral healthcare provider. Such vulnerability heightens any negative perception, leading to the client’s perception of powerlessness and the attitude that the oral healthcare provider’s comments or behaviors “made things worse.” Examples of practitioner behaviors that increase dental anxiety include the following:

A person with extreme dental anxiety also may suffer from social phobia. Social phobia is persistent fear in one or more social situations in which fear of embarrassment or humiliation is avoided. Those individuals who are socially phobic may feel the following6:

The resulting feelings of powerlessness and embarrassment in dental situations lead to phobic avoidance of professional oral healthcare.5,6 Prevention of phobic avoidance highlights the importance of social acceptance in the oral care environment.

Nonpersonal Experience

Learning to be fearful of dental treatment may occur before the individual experiences the first dental appointment. Such learning is termed vicarious learning because it is based on fear felt by sharing in the experience of another. Vicarious learning takes place when role models, peers, and society influence individuals before their firsthand experience. Observing others and listening to embellished experiences can negatively sensitize individuals to dental appointments. Parents who experience dental anxiety often pass along such feelings to their children.

Personality Traits and Somatic Well-Being

Dental fear and anxiety are correlated with several individual personality traits, such as hostility, neuroticism, and psychologic and somatic lack of well-being. Somatic complaints are often reflected in the client’s health history. Somatoform disorders are recurrent and multiple chronic somatic complaints, where no physical disorder can be found with medical examination. These complaints can be unreasonable body image problems or mind-body reactions that result in psychogenic-like pains, tachycardia, fainting, hypochondriasis, or gagging.3 In the absence of psychogenic pains and hypochondria, which are unlikely to be offered by the client during health history assessment, conditions such as stomach ulcers, gastric reflux, and ulcerative colitis, in addition to elevated heart rate and blood pressure, may be cited. Such signs may indicate a nervous nature underlying the anxiety of the dental procedures. Cues such as these may give the oral healthcare practitioner insight into the client’s anxiety level.

ASSESSMENT

Few if any questions on the health history are directed at the client’s feelings toward the upcoming oral healthcare to be provided. The typical health history questionnaire, however, may have a question that asks, “Have you had any serious trouble associated with any previous dental treatment?” and/or “Do you feel very nervous about having dental treatment?”3 Moreover, the Dental Hygiene’s Human Needs Conceptual Model of Dental Hygiene Care includes assessing the human need for freedom from fear and stress through interview dialogue and direct observation and then setting related goals to modify care as needed (see Chapter 2). Recognition of fear and anxiety is extremely important because heightened anxiety and fear of oral healthcare are stresses that can lead to the exacerbation of medical problems such as angina, seizures, asthma, hyperventilation, or vasodepressor syncope.3 It is recommended that the dental hygienist carefully assess the health history, vital signs, and human need for freedom from fear and stress with every client, with the ultimate goal being to determine the following3:

The client’s ability to tolerate psychologically the stresses involved in the planned oral healthcare

The client’s ability to tolerate psychologically the stresses involved in the planned oral healthcare Care modifications indicated to enable the client to better tolerate the stresses involved in the planned oral healthcare

Care modifications indicated to enable the client to better tolerate the stresses involved in the planned oral healthcare Whether the additional use of local anesthetic and/or nitrous oxide–oxygen psychosedation is indicated (see Chapters 39 and 40)

Whether the additional use of local anesthetic and/or nitrous oxide–oxygen psychosedation is indicated (see Chapters 39 and 40)Many adults (e.g., men younger than 35 years of age) are reluctant to express their fears about proposed treatment for fear of being labeled a “baby.” The outcome of “taking it like a man” or “grinning and bearing it” may result in an episode of syncope. Often these same individuals may volunteer this information in writing if questions are included in the health history or another type of questionnaire.3 Therefore a comprehensive approach to assessment of fear and anxiety includes verbal interview, written questionnaires, vital signs, and careful observation to recognize the presence of unusual degrees of fear and anxiety.

Physiologic Assessment

Physiologic changes attributed to fear may be easily assessed through accurate performance and recording of vital signs (see Chapter 11). Activation of the stress response through the autonomic nervous system causes blood pressure, heart rate, and respirations to increase in response to the release of adrenaline (i.e., epinephrine). Additional effects of adrenaline are dilation of pupils and decrease in salivary flow. Diaphoresis (sweating) of the palms and forehead also may be an indication of anxiety.3 Therefore shaking hands with the client may lead to an assessment of anxiety when the client’s palms are cold and sweaty, especially when the environment is not overly cool or hot.

A thorough health history review also may identify other physiologic signs of a nervous disposition, such as somatoform disorders. When the dental hygienist has identified elevated vital sign readings and/or a history of digestive and cardiovascular signs for which no physiologic explanation is appropriate, dental anxiety may be suspected. Additional tools for determining the potential existence and degree of dental fear or anxiety are psychologic assessment surveys described in the following sections.

Psychologic Assessment

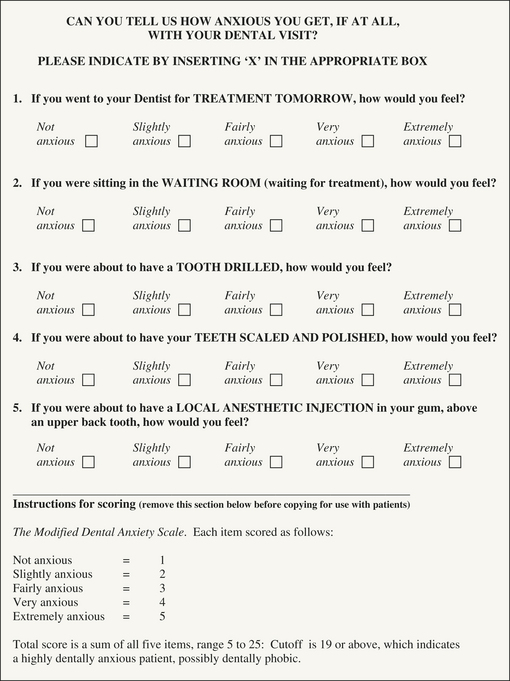

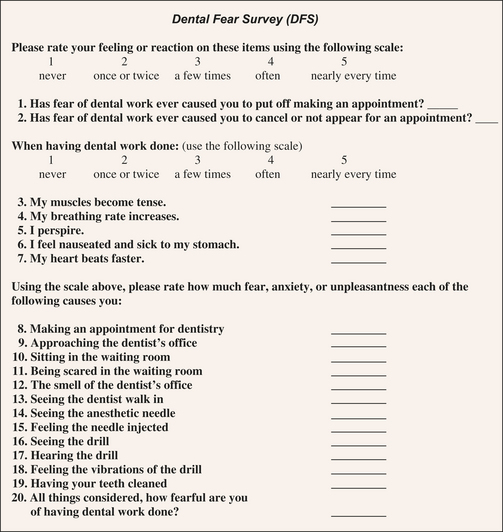

Psychologic assessment of dental anxiety and fear is accomplished mainly through surveys or questionnaires completed by the client. A rating scale applied to the responses provides an indication of degree of fear and, in some instances, specific feared objects or situations. Two widely used scales to assess dental anxiety and fear are the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) (Figure 37-2) and the Dental Fear Survey (DFS) (Figure 37-3).

Figure 37-2 The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale.

(From Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ: The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: validation and United Kingdom norms, Community Dent Health 12:143, 1995.)

Figure 37-3 The Dental Fear Survey.

(Modified from Kleinknecht RA, Klepac RK, Alexander LD: Origins and characteristics of fear of dentistry, J Am Dent Assoc 86:842, 1973.)

Modified Dental Anxiety Scale

The MDAS consists of five questions dealing with feelings and physiologic reactions in different oral healthcare situations, with the total score ranging from 5 to 25.1,7 A total score of 13 to 18 suggests a dentally anxious person, and 19 or higher suggests a highly dentally anxious client. This easy-to-use scale provides limited information on narrow or specific areas of fear reactions (see Figure 37-2). Data confirm the high reliability and validity of the MDAS.

Dental Fear Survey

The DFS assesses a broad range of dental fear components across three different dimensions: avoidance and anticipatory anxiety, autonomic or physiologic arousal, and fear of specific objects or situations (e.g., fear of seeing and feeling an injection needle and fear of the drill). Twenty items are rated on a high (5) to low (1) scale of intensity of reactions, giving a score range of 20 to 100. Severely dentally fearful individuals have been shown to have scores of 75 and above. The DFS has been used in epidemiology research to measure the prevalence of dental fear and in clinical trials to measure effects of dental fear on treatment (see Figure 37-3). Moreover, it has been shown that DFS scores predict anxiety exhibited during dental treatment and that DFS items relate to previous dental experiences, client age, and treatment invasiveness.1

Behavioral Assessment

Because young children are not able to complete the MDAS or DFS described previously, close observation of their behavior provides information on their degree of fear. Children are more behavioral in their display of dental fear and anxiety, and in most instances, the dental hygienist is readily able to discern their degree of fear. Clinging or uncooperative behavior and crying are actions that depict fear. For young children who may not be talking, determining what object or situation is inciting a fearful response is often a challenge.

Adults, although usually more in control of their bodies than children, display fearful behaviors in several ways. As a result of activation of the autonomic nervous system, muscular activity may be increased. Increased startle reflex, nervous tics, fidgeting, hand clenching, gripping the armrests of the chair, and breath holding are all behaviors that indicate stress. The client, once seated, should be listened to and watched carefully. Malamed notes that apprehensive clients “remain alert and on guard at all times. They sit at the edge of the chair, eyes roaming around the room, taking in everything. They exhibit an unnaturally stiff posture, their arms and legs tense.”3

MANAGEMENT OF FEAR AND ANXIETY

Once fear and anxiety are recognized, the client must be confronted with a straightforward approach.3 For example, the dental hygienist might say, “Mrs. Jones, I see from your health history that you have had several unpleasant experiences in a dental office. Tell me about them.” Or, if the anxiety is determined based on visual cues, the dental hygienist might say, “Mrs. Jones, you seem somewhat nervous today. Is something bothering you?”

Often clients will immediately drop their defenses once they know the dental hygienist is aware of their fears. They might say, “I didn’t think you could tell” or “I thought I could deal with this, but I am really nervous about my appointment today.” The hygienist then seeks to identify with the client the specific aspects of care that concern the client the most, and together they take steps to minimize the development of adverse situations related to them.3 The mere act of discussing fears openly not only leads to possible specific solutions but also eases some of the anxiety associated with the fear. Although there are a number of ways fear and anxiety can be managed, only four are discussed here: practice characteristics, positive communication and rapport, treatment sequencing, and behavioral mind-body techniques to help clients learn skills to cope with their fear and anxiety.3

Practice Characteristics

Reception and Treatment Area

A primary consideration in managing clients’ fear and anxiety is assisting them in feeling as comfortable as possible in the dental environment. Individuals who feel their fears regarding dental procedures are acknowledged and understood experience lower levels of anxiety because of the empathetic attitude of the caregiver. Positive staff attitudes as well as a relaxed office environment help to allay fears. Once clients arrive, their presence should be acknowledged, and they should be informed if there has been a delay in scheduling rather than be kept waiting for no apparent reason.3 Valuing the individual’s time by minimizing waiting and occupying clients by helping them complete forms decreases anticipatory anxiety (Box 37-5).

BOX 37-5 Dental Office Factors to Reduce Fear and Anxiety

Reception Area

In the treatment areas, instruments should be kept out of client sight, such as under a clean client-care napkin, until the dental hygienist is ready to use them. For individuals who are fearful of the sound of the handpiece, ultrasonic scalers, or air abrasive polishers, using portable headsets and compact disk or audiotape players with self-selected music can help to diminish anxiety. Studies have shown that eugenol smells elicit emotional responses from dentally fearful individuals. Therefore medicinal smells and chemical odors should be managed using optimum ventilation, exhaust fans, and masking to the extent possible. A pleasant room freshener, aromatic candle, or other similar scenting device creates a more comforting, less sterile atmosphere. Attention to detail when planning the reception and treatment areas combined with a friendly, empathetic staff engenders an environment of support.

Positive Communication and Rapport

Positive and frequent communication during dental hygiene care is of vital importance in alleviating anxiety. The client should be escorted to the treatment area and seated in the dental chair. Immediately the dental hygienist should adjust the chair and headrest as desired by the client to aid the client’s comfort level and offer a facial tissue. In addition, it is important for the dental hygienist to spend a moment or two talking with the client while maintaining eye contact before starting the process of care.3 Asking how the client is feeling and genuinely listening to the response convey the message that what the individual relates is important. Relating to the client’s feelings displays empathy and concern. Such a climate fosters trust and openness and begins the client’s process of relearning the dental experience. When clients are able to express their fears to the hygienist before treatment begins, these fears become more manageable during treatment.3

Planned dental hygiene care should be explained fully in sensory terms: how treatment will sound, feel, and look. Information about the procedure, including showing the instruments to be used and describing in clear terms how they will be used and any discomfort that may be experienced, often is enough to alleviate fear. In addition, a simple statement such as “If for any reason you would like me to stop, simply raise your hand and I will stop immediately” expresses concern and empathy. Fearful clients may test this system several times to reassure themselves that the hygienist is telling the truth; but once convinced, they will relax and allow treatment to continue.3

Positive communication, in which words are chosen carefully, helps not only to describe exactly what the procedure entails but also helps to reduce client anxiety. For example, using the word “discomfort” rather than “pain” and phrasing actions in positive terms such as “I am going to numb you up now so that you will be more comfortable” rather than “I am going to give you a shot now” help to alleviate anxiety. An example of describing what to expect in sensory terms after scaling and root planing is the following: “It is possible that you may feel a swelling or sponginess in your gums tonight and tomorrow, as if your teeth were floating in your tissues. When you bite, they may feel like they float up and down in their sockets. You may also feel as if your gums are itchy. These feelings are perfectly normal. On the other hand, you may not experience any after-effects from our scaling; most people don’t, especially when they use saltwater rinses to decrease the swelling in their tissues.” Such phrasing informs the client and helps to alleviate anxiety.

Finally, clients are often mistrustful or hostile because of past bad experiences. Emotionally they may be ill-prepared for a dental hygienist who may be brusque, too busy to listen, or uncaring with regard to their comfort. Even though the dental hygiene care may be technically excellent, the dental hygienist may have unknowingly created fearful, avoidant behavior in the person he or she is trying to help. Therefore condescending remarks or appearing to be too busy for client interaction are to be avoided.

Using the CARE approach to client-centered interaction (comfort, acceptance, responsiveness, and empathy) (see Chapter 4) can prevent or help manage clients’ anxiety and assist them with having a positive experience. In addition, for many fearful clients it is the perceived loss of control they experience in the dental chair that intimidates them the most. In managing the fearful client, it is critical that the dental hygienist offer respectful care that gives clients some control by doing the following:

Allowing clients to feel and act afraid without feeling embarrassed and to talk about their apprehension

Allowing clients to feel and act afraid without feeling embarrassed and to talk about their apprehension Educating clients regarding care to be provided so that they are able to determine their own course of treatment

Educating clients regarding care to be provided so that they are able to determine their own course of treatment Informing clients before initiating procedures to avoid surprising the client with something unexpected

Informing clients before initiating procedures to avoid surprising the client with something unexpectedRespectful care also includes inquiring about client comfort level and, if pain is felt, stopping to alleviate discomfort. In addition, a gentle touch always is appreciated. An anxious client often responds positively to such a show of respect and empathy so that other behavioral management techniques are unnecessary (Box 37-6).3

Treatment Sequencing

Depending on the level of anxiety, beginning treatment with a less-involved procedure may be the optimum sequence to help an anxious, fearful individual feel more successful and in control of his or her dental hygiene experience. As the appointments transition into more difficult procedures, not only the client’s trust and confidence in the dental hygienist’s abilities and manner increase, but also the level of confidence in the client’s own capacity to endure the treatment increases, perhaps transforming a perceived nightmare into a bearable situation.

SPECIFIC BEHAVIORAL MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES

As the degree of fear and anxiety becomes more overt, specific behavioral management techniques may be necessary to augment positive communication and assist the individual in coping with the procedure. Such techniques include behavioral modeling, distraction, and relaxation therapy. These techniques are safe, are free from adverse effects when judiciously used, and give the individual a sense of control.

Behavioral Modeling

The strategy of behavioral modeling, frequently used to modify children’s behavior, can produce significant and stable changes.8 With modeling the child watches another individual undergo a procedure, either live or in video format, and then is encouraged to behave as that person did. An example of behavioral modeling may occur when an older sibling is undergoing dental hygiene care while his or her younger sibling watches. Care must be exercised in choosing individuals to be watched because they must exhibit the desired behaviors.

Distraction

Some individuals are not interested in a full disclosure of the treatment to be accomplished but prefer instead to be distracted by some pleasurable image or interesting activity. Distraction involves engaging the client’s mind actively at something other than attending to the dental treatment.5 Distraction works well for activities of a short duration, such as exposing radiographs, timing topical fluoride treatments, and waiting for alginate impressions to set. Effective distractions include picking out as many items of a particular set as possible on a mounted poster, mentally reciting one’s multiplication tables, or holding one foot in a position while doing another action with the other foot. Imagination is the only limitation to suitable distractions.

Allowing the fearful client to listen to self-selected music using a headset or to watch an absorbing program on a television monitor mounted in viewing range of the dental chair is a type of distraction technique. Such fear and anxiety management methods, however, are unpredictable and may not work consistently for the same client. In addition, a barrier against effective communication may be created because the individual may not be attending to professional actions and conversation.5

Relaxation Therapy

Relaxation therapy includes a variety of techniques used to elicit the relaxation response—a protective mechanism against stress that decreases heart rate, lowers metabolism, decreases respiratory rate, and decreases muscle tension.2,5 A relaxed body promotes a clear and relaxed mind. The human body cannot be physically relaxed and mentally anxious at the same time. The brain will not process these feelings simultaneously. Before instructing the individual in any type of relaxation therapy, however, the client should be prepared with a full explanation and the option to decline the therapy (Procedure 37-1).

Procedure 37-1 PREPARING THE CLIENT FOR RELAXATION THERAPY

The dental hygienist should not begin relaxation therapy without thoroughly explaining the process to the client and obtaining informed consent.

STEPS

Deep Breathing

One of the easiest relaxation therapies to learn and teach is deep breathing. This technique involves breathing slowly and deeply. In so doing, the practitioner floods the body with oxygen and other chemicals that work on the central nervous system to improve comfort. Stress typically causes rapid shallow breathing, which sustains other aspects of the stress response, such as a rapid heart rate. Fearful individuals may not be aware that they are holding their breath or breathing in a shallow manner. When the breath is held unnecessarily or when inhalations are shallow and tense, the muscles of the back and abdomen begin to tense, narrowing alimentary and respiratory passages. Such tensions can by themselves produce a state of anxiety. If clients can get control of their breathing, the spiraling effects of acute stress will automatically decrease.2 Deep breathing promotes increased oxygen to the brain and muscles and a sense of calm. See Procedure 37-2 for how to instruct clients in this relaxation therapy to help clients gain control of their breathing.

Procedure 37-2 TEACHING DEEP BREATHING TO A FEARFUL CLIENT

STEPS

Guided Imagery

Guided imagery is a simple mental technique in which the dental hygienist, guided by the client’s suggestions, verbally constructs a scenario for the client to visit mentally.9 During the appointment the dental hygienist helps the client form mental images to take a visual journey to a peaceful, calming place or situation. As part of the process, the hygienist creates mental detail using as many senses as possible, including smells, sights, sounds, and textures. For example, if the visual journey is to the ocean, the hygienist guides the client to feel the warmth of the sun, the sound of crashing waves, the feel of the grains of sand, and the smell of salt water. In guided imagery, individuals “think in mental pictures,” creating for themselves a sense of calmness and security in a setting of their choice. Many clients are enthusiastic about “leaving” the treatment room for a mental vacation, guided by a person they trust. When asked if they could go anywhere and do anything, fearful clients often clearly and unambiguously reveal their imaginary locations and activities. The suggestion that the individual concentrate on the mental scene with closed eyes helps block visual fear-inducing stimuli. The dental hygienist converses throughout treatment, building details into the scenario to keep the client’s attention in the scene and not on the dental hygiene care (Procedure 37-3).

STEPS

For purposes of this exercise, we will assume that the client verbalized enjoying lying in the sand at the beach.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

Progressive muscle relaxation focuses on slowly tensing muscles for at least 5 seconds, relaxing each muscle group for 30 seconds, and then repeating the procedure for four or five cycles before moving to the next muscle group.2 The dental care provider guides clients to start by tensing and relaxing the muscles in their toes and progressively working their way up to alternate tensing and relaxing of skeletal, forehead, eye, and vocalizing muscles to induce physical and mental relaxation. This technique helps the client focus on the difference between muscle tension and relaxation. Progressive muscle relaxation is based on the theory that if a muscle is relaxed, it cannot be tense at the same time. This strategy may work with individuals who require a more active method of relaxing.2 Although tensing and relaxing muscles involves covert muscular movement, such actions do not typically interfere with treatment and may be carried out in conjunction with dental hygiene care (Procedure 37-4).

Procedure 37-4 GUIDING THE CLIENT INTO PROGRESSIVE MUSCLE RELAXATION

Adapted from Potter PA, Perry AG: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 7, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.

STEPS

Progressive Relaxation

Progressive relaxation focuses on consciously trying to relax each muscle in the body, starting with the toes and moving all the way up to the head with the aim of reducing tension. Unlike the progressive muscle relaxation technique, progressive relaxation focuses only on muscle relaxation and does not involve alternating tensing and relaxing muscles. Progressive relaxation is usually preceded by deep breathing and guides the client into deeper relaxation, focusing progressively on different muscle groups.9 Suggestions by the dental hygienist to begin with the feet and to progress toward the head draw attention from the head and dental procedures (Procedure 37-5).

Procedure 37-5 GUIDING THE CLIENT INTO PROGRESSIVE RELAXATION

STEPS

For dental hygienists beginning to use the progressive relaxation technique, audiotaping the script ahead of time and listening to it to relax themselves is an excellent way to learn and hone the technique. Practicing will lead to comfort and ease of application. After customizing one’s phrasing, voice tone, and modulation to enhance confidence, the dental hygienist should try the technique on a friend or colleague. Before implementing progressive relaxation into a dental hygiene care plan, the dental hygienist must thoroughly explain the process to the client and obtain informed consent.

Awaking from Relaxation

After completion of dental hygiene care, awakening from any relaxation must always be performed to ensure that the client is fully alert before dismissal. The wakening procedure follows every relaxation therapy session (Procedure 37-6).

Procedure 37-6 AWAKENING THE CLIENT AFTER RELAXATION THERAPY

OTHER BEHAVIORAL SUGGESTIONS FOR CONTROLLING DENTAL ANXIETY

Preappointment Client Behaviors

Having fearful clients avoid caffeine for at least 6 hours before their oral healthcare visit can help them become less anxious. Also, eating high-protein foods, such as cheese, 1 hour before also helps with calming anxiety. Sugary foods can increase agitation, and carbohydrates do not have the same calming effect that protein-rich foods do.8

Support Groups

Most communities have support groups for people who suffer from anxiety or phobias. Support and self-help groups do more than provide emotional support. They are also a useful source of practical tips and coping skills. Information about local support groups can be accessed by calling mental health professionals in the area or by using the Internet to contact the American Self-Help Clearinghouse.9

Therapy

People who neglect their oral health because they are phobic may want to see a mental health professional. Psychologists and psychiatrists often use a technique called systematic desensitization (discussed later), in which clients are exposed gradually to things they are afraid of, in a controlled and careful manner. This technique is an effective treatment for many types of phobias, including dental phobia.9

Cognitive-Behavioral Psychotherapy

In cognitive-behavioral therapy, the therapist helps individuals develop thinking and behavioral strategies for overcoming dental phobia. In addition, clients are encouraged and helped to understand where their fears come from and to make peace with difficult events in the past.

ADVANCED BEHAVIORAL TECHNIQUES

Advanced behavioral techniques include systematic desensitization and hypnosis. Because of the complexity of these techniques, they should be provided only by dental hygienists, dentists, and mental health professionals who are trained in their use. Information regarding systematic desensitization and hypnosis is provided to facilitate accurate education of the fearful client regarding more advanced behavioral management strategies. Dental hygienists and dentists with training in systematic desensitization and hypnosis may be found by calling the local dental society.

Systematic Desensitization

Systematic desensitization is a behavioral technique in which clients are gradually exposed to the things that cause them fear.10 For example, in the oral healthcare setting, clients may be afraid of dental instruments, especially the syringe and the needle. Systematic desensitization employs a hierarchy of fearful stimuli constructed by the subject to gradually address his or her fears in ascending order. The concept of gradual exposure from the least fear-arousing aspects of an object or behavior to the most fear-arousing situation is used to mentally address fears while the client is in a deep state of relaxation. The individual begins the desensitization process by developing a list of fear-invoking stimuli, with the least noxious at bottom, graduating up to the most painful, fearful stimulus. A sample hierarchy to desensitize for fear of the dental drill might begin with making an appointment, going to the dental office, and sitting in the reception area and gradually progress to entering the treatment area, sitting in the chair, seeing the dentist, hearing noises, receiving an injection, and receiving the drilling.

When practicing systematic desensitization, the client is asked to imagine confronting the least noxious stimulus; the body is simultaneously scanned for any sign of tension. Clients are instructed to substitute relaxation for their anxiety response (which can be either experienced or imagined) at each level of the hierarchy. As the client becomes more adept at relaxing while imagining the stimulus, he or she can begin to work up the chart, addressing the increasingly aversive stimuli. The client stays at one level until completely relaxed when confronting the experience, before progressing to the next level.

Hypnosis

Hypnosis is a state of mental relaxation and restricted awareness in which individuals are engrossed in their inner experiences, such as feelings and imagery, are less analytic and logical in their thinking, and have an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestions in an automatic and disassociated manner. Hypnosis serves as a means of providing relaxation and decreased anxiety without the need for drug administration.3,9 The appropriately trained dental professional serves as a guide to clients, leading them to concentrate on internal feelings or pleasant images. As clients become less analytic in their thinking, they more easily accept suggestions for their comfort and well-being. Active therapeutic suggestions may be given that benefit both client and oral care professional by doing the following:

CONCLUSION

An attitude of caring is an integral part of dental hygiene care and is of vital importance in the everyday practice of dental hygiene. In the absence of a caring attitude, clients feel isolated and alienated, increasing their anxiety levels and producing additional management difficulties for providing dental hygiene care. Application of behavioral management techniques for clients with dental fear and anxiety helps to induce client relaxation, reduce anxiety, and possibly decrease a client’s requirement for analgesics and other drugs with their potential side effects.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Explain that it is possible for clients to relearn to receive dental treatment. They will not always be fearful or anxious when approaching dental care.

Explain that it is possible for clients to relearn to receive dental treatment. They will not always be fearful or anxious when approaching dental care. Explain that dental hygienists who attend formal education or training classes are legally qualified within the scope of dental hygiene practice to provide advanced behavioral management techniques.

Explain that dental hygienists who attend formal education or training classes are legally qualified within the scope of dental hygiene practice to provide advanced behavioral management techniques.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Behavioral management techniques taught within formalized educational programs and practiced under supervision are part of a comprehensive dental hygiene care plan.

Behavioral management techniques taught within formalized educational programs and practiced under supervision are part of a comprehensive dental hygiene care plan. Adequate, routine precautions need to be taken for each client, such as maintaining continuous oversight of the client to prevent any claims that the client was unattended in a time of need.

Adequate, routine precautions need to be taken for each client, such as maintaining continuous oversight of the client to prevent any claims that the client was unattended in a time of need. Document in the client record that the client was informed of relaxation therapy options to manage pain and anxiety and gave his or her consent. Entries should include which therapy was performed, the client’s response, and the fact that the client was fully alert when dismissed.

Document in the client record that the client was informed of relaxation therapy options to manage pain and anxiety and gave his or her consent. Entries should include which therapy was performed, the client’s response, and the fact that the client was fully alert when dismissed. An effective care plan for a fearful client includes a behavioral management component to promote a sense of control and to optimize client cooperation and comfort.

An effective care plan for a fearful client includes a behavioral management component to promote a sense of control and to optimize client cooperation and comfort. Dental hygienists wishing to use hypnosis must be instructed through a dental school curriculum on anesthesia and pain management or attend formalized instruction offered through the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis.

Dental hygienists wishing to use hypnosis must be instructed through a dental school curriculum on anesthesia and pain management or attend formalized instruction offered through the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis. Legal aspects of hypnosis can be separated into two divisions: (1) laws that pertain to the practice of dentistry and dental hygiene, and (2) laws that pertain to conduct as a citizen outside of the professional role. As long as dental hygienists use hypnosis within the context of their professional roles, their usual professional liability insurance that includes malpractice will cover them. A rider to the policy including the specific use of hypnosis is generally not needed; however, individual state dental practice acts should be reviewed.

Legal aspects of hypnosis can be separated into two divisions: (1) laws that pertain to the practice of dentistry and dental hygiene, and (2) laws that pertain to conduct as a citizen outside of the professional role. As long as dental hygienists use hypnosis within the context of their professional roles, their usual professional liability insurance that includes malpractice will cover them. A rider to the policy including the specific use of hypnosis is generally not needed; however, individual state dental practice acts should be reviewed.KEY CONCEPTS

There are physiologic, psychologic, and behavioral cues to identifying a client who is fearful or anxious of dental treatment.

There are physiologic, psychologic, and behavioral cues to identifying a client who is fearful or anxious of dental treatment. The cause of dental fear or anxiety may involve either direct personal experience or vicarious experience.

The cause of dental fear or anxiety may involve either direct personal experience or vicarious experience. Behavioral management techniques used to control fear and anxiety include behavioral modeling; distraction; relaxation therapy (deep breathing, guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, progressive relaxation); client-centered communication; client preoperative avoidance of caffeine, sugary foods, and carbohydrates; ingestion of cheese and protein-rich foods; systematic desensitization; and hypnosis.

Behavioral management techniques used to control fear and anxiety include behavioral modeling; distraction; relaxation therapy (deep breathing, guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, progressive relaxation); client-centered communication; client preoperative avoidance of caffeine, sugary foods, and carbohydrates; ingestion of cheese and protein-rich foods; systematic desensitization; and hypnosis.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Profile: Ms. D, age 35, is scheduled for nonsurgical periodontal therapy with the dental hygienist. She is a new patient and has not been seen for dental care in more than 2 years. As you enter the reception room to announce Ms. D’s name, you notice a woman flipping through a magazine and sitting on the edge of her chair. She looks up quickly as you say her name, and she gives you a hesitant smile.

Chief Complaint: “I am in pain from a back left lower tooth.”

Medical History: Ms. D’s vital signs are as follows: pulse, 92 BPM; respirations, 25 RPM; temperature, 99° F; and supine blood pressure, 140/80 mm Hg. She admits to having gastric reflux and prefers to sit back partially rather than supine. She smokes approximately one-half pack of cigarettes per day.

Social History: Ms. D is single and lives alone.

Dental History: As you seat her in your treatment room, she admits that the last time she visited a dental office was more than 2 years ago. Ms. D said the dentist did not numb her tooth enough to take the pain away and began a root canal in a lower left molar. She never went back for the completion of the endodontic therapy, and now the tooth is bothering her. Intraorally, Ms. D’s gingival tissues are erythematous along the margins, and the interdental papillae are bulbous. Her gingival tissues are smooth, with generalized bleeding on probing. You notice the tooth in question, No. 19, has a large opening on the occlusal surface. In addition to the incomplete endodontic treatment, Ms. D has two other carious areas on interproximal surfaces.

Oral Health Behavior Assessment: Her homecare consists of brushing once per day with a soft brush and trying to floss once per week. She realizes she could do more but states that she “doesn’t have time.”

Supplemental Notes: Ms. D grips the armrests of the chair on periodontal probing. After numerous stops and starts, she admits that she is terrified of dental treatment no matter who performs it and has been fearful of dentistry since she was a child.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge Ruth Hull for her past contributions to this chapter.

Refer to the Procedures Manual where rationales are provided for the steps outlined in the procedures presented in this chapter.

1. Heaton L.J., Carlson C.R., Smith T.A., et al. Predicting anxiety during dental treatment using patients’ self-reports. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:188.

2. Mayo Clinic Health Solutions. My stress solution. Rochester, Minn: Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; 2008.

3. Malamed S.F. Sedation: a guide to patient management, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2003.

4. Locker D., Liddell A., Dempster L., Shapiro D. Age of onset of dental anxiety. J Dent Res. 1999;78:790.

5. Frochak M: Why do I fear the dentist? Available at: www.floss.com/fh_men_phobia.html. Accessed July 21, 2008.

6. Web MD: Oral health center. Dental health: easing dental fear in adults. Available at: http://webmd.com/oral-health/easing-dental-fear-adults. Accessed July 21, 2008.

7. Humphris F.M., Freeman R.E., Tutti H., Desouza V. Further evidence for the reliability and validity of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale. Int Dent J. 2000;50:367.

8. Goodman J: Coping with dental anxiety. Available at: www.goodteeth.com/mars.htm. Accessed July 21, 2008.

9. Colgate World of Care: Treatments and coping methods. Available at: www.colgare.com/app/Colgate/US/OC/Information/OralHealthBasics/CheckupsDentProc/T. Accessed July 21, 2008.

10. Cardamone P: Questions and answers on overcoming dental fear. Available at: www.dentalfear.com/cardamone.asp. Accessed July 21, 2008.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..