CHAPTER 16 Dental Caries Management by Risk Assessment

Explain the process of demineralization and remineralization that occurs in the oral environment and saliva's beneficial actions.

Explain the process of demineralization and remineralization that occurs in the oral environment and saliva's beneficial actions. Explain the key disease indicators and risk factors that determine whether the client is at low, moderate, high, or extreme risk.

Explain the key disease indicators and risk factors that determine whether the client is at low, moderate, high, or extreme risk. Explain, based on level of dental caries risk, when the following are indicated:

Explain, based on level of dental caries risk, when the following are indicated:

Risk assessment is an estimation of the likelihood that an event will occur in the future.1 For more than two decades, medical science has recommended that physicians identify and treat patients based on their risk status, rather than treating all patients as if they were the same.2 Although individual contributing factors to dental caries risk have been identified for over two decades, only recently have combinations been put together in validated procedures for application to everyday clinical practice.3 Caries risk assessment is the first step in Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA), an evidence-based disease management protocol. With the CAMBRA methodology the clinician first assesses an individual's caries disease indicators, risk factors, and protective factors and then determines the level of caries risk that the sum of these factors indicates (low, moderate, high, or extreme). Based on the level of caries risk, an evidence-based care plan is developed that includes specific behavioral, chemical, and minimally invasive preventive and therapeutic procedures to manage the individual's dental caries disease.4,5

Many of the CAMBRA procedures fall within the purview of the dental hygienist. Dental hygienists need to be knowledgeable and prepared to assess caries risk, to implement noninvasive or minimally invasive procedures according to state or province practice acts, and to provide leadership in promoting synergistic relationships with other staff members to create an environment of excellent client care. Every member of the dental team is essential to establishing a CAMBRA prevention-focused practice and to achieving successful client outcomes.6 This chapter will review the dental caries disease process and the background, rationale, and step-by-step procedures for the CAMBRA approach to caries management by risk assessment. It also will provide an overview of topical fluoride use and other chemical interventions to manage the disease of dental caries based on level of caries risk.

DENTAL CARIES: A CONTINUING HEALTH ISSUE

Dental caries is a transmissible bacterial infection that is preventable and in some cases even reversible. Dental decay, however, remains the single most common disease of childhood that is not self-limiting or amenable to a course of antibiotics.7 Dental caries also is the most common dental disease affecting both children and adults in the United States and Canada, and it remains a significant worldwide disease.8

REVIEW OF DENTAL CARIES PROCESS

Demineralization

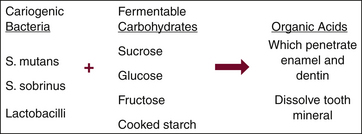

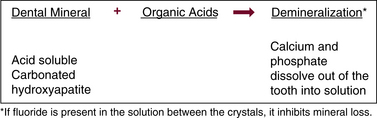

Dental caries is caused by mutans streptococci (a group that includes the Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus species) and lactobacilli that live in the plaque biofilm that attach to teeth. These bacteria metabolize dietary fermentable carbohydrates (sugars and cooked starch) to produce acids. These acids cause a substantial change in the plaque biofilm pH. At rest the pH of plaque biofilm is typically neutral. When fermentable carbohydrates are ingested, the plaque biofilm pH drops rapidly to create an acidic environment. The acids diffuse into the tooth to dissolve the calcium and phosphate minerals (carbonated hydroxyapatite). This process is called demineralization9-11 (Figures 16-1 and 16-2).

Remineralization

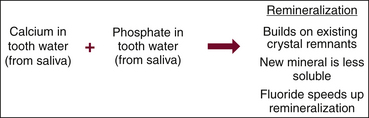

After the ingestion of fermentable carbohydrates stops, the pH gradually returns to neutral in 30 to 60 minutes provided there is adequate saliva. A variety of factors mediate the return to a neutral pH. Saliva plays a key role in that it neutralizes acids and provides minerals and proteins that protect the teeth (Box 16-1). Once calcium and phosphate are lost from the tooth structure and the pH in the adjacent environment returns to neutral, the area experiences remineralization. Minerals in the saliva and minerals dissolved out of the tooth are available to redeposit onto existing crystal remnants inside the tooth. This deposition of minerals into demineralized areas of tooth structure is called remineralization, which repairs the initial carious lesion (Figure 16-3). This ongoing process of destruction and repair occurs with each carbohydrate challenge.

BOX 16-1 Saliva's Beneficial Actions

From Eakle SW, Featherstone JDB: Caries risk instruction [course handout], San Francisco, 2002, University of California School of Dentistry.

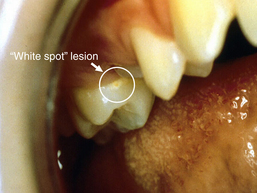

Whether an initial carious lesion progresses and develops into a frank carious lesion (a hole or cavitation) depends on a variety of factors. To prevent the lesion from progressing, there must be enough deposition of salivary minerals to repair and strengthen the area and provide support for the enamel surface and subsurface. Minerals in the saliva initially enable the host to repair demineralized areas. If, however, the flow of saliva is low, the level of acid-producing bacteria is high, and the frequency of eating and/or drinking of fermentable carbohydrates is high, then the tooth mineral lost by acid attacks is too great for repair by natural salivary remineralization. This situation leads to the start of dental caries evidenced clinically as a white spot lesion (Figure 16-4). It should be noted, however, that fluoride plays a very important role in the remineralization repair process and the overall prevention of carious lesions. Fluoride works primarily via topical surface mechanisms to inhibit demineralization, enhance remineralization, and inhibit plaque biofilm bacteria.11

The White Spot Lesion

Demineralization results in the greatest loss of calcium and phosphate minerals in the subsurface zone of the enamel and the formation of a white spot lesion. The enamel surface of the white spot typically remains intact, but the demineralized area appears white owing to the loss of mineral in the subsurface zone of the enamel (see Figure 16-4). By comparison, the enamel surrounding the white spot appears sound and translucent.11 Thus, a white spot lesion is a demineralized area of enamel that usually has an intact surface remaining over the body of the demineralized early carious lesion. It is partially reversible with appropriate topical fluoride intervention. The white spot lesion is a signal to intervene to avoid the development of a frank carious lesion. It is not a signal to do surgery (e.g., place a restoration).11 The demineralization process for cementum and dentin is similar to that for enamel, except that the process does not typically result in an intact surface remaining over the body of the carious lesion.8

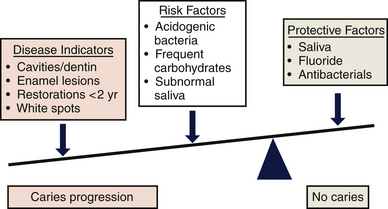

The Caries Balance

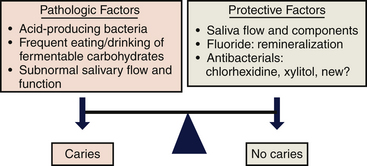

Dental caries involves an interaction among pathologic factors and protective factors. Pathologic factors include acidogenic (acid-producing) bacteria (mutans streptococci and lactobacilli), frequent eating and/or drinking of fermentable carbohydrates, and subnormal salivary flow and function. Protective factors include calcium, phosphate, proteins, and fluoride in the saliva; normal salivary flow; and antibacterial agents if needed (Figure 16-5).4 The goal of caries management is to restore and maintain a balance, known as the caries balance, between protective factors and pathologic factors to remineralize early carious lesions and/or prevent future caries.

DENTAL CARIES RISK ASSESSMENT FOR CLIENTS AGE 6 THROUGH ADULT

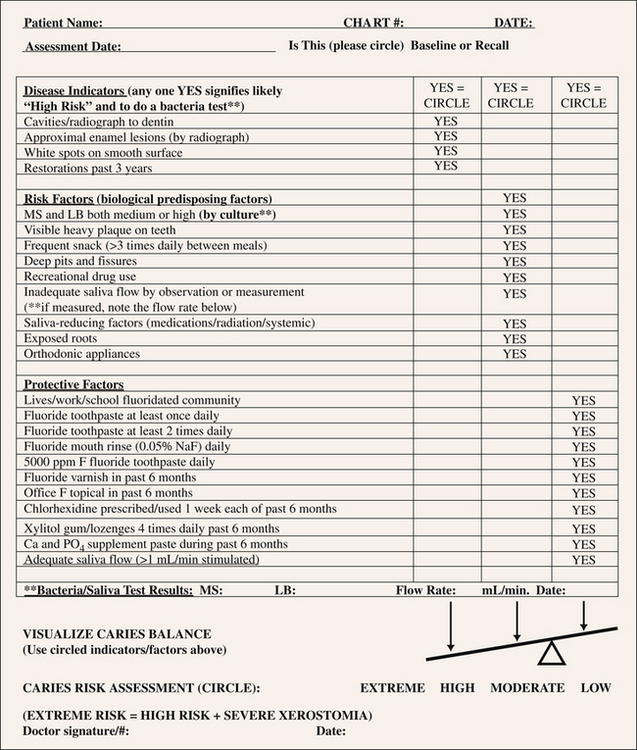

Caries risk assessment is the first step in CAMBRA. A group of experts from across the United States convened at a consensus conference in 2002 produced a caries risk assessment procedure and form for 6-year-olds through adults that was subsequently validated in a large cohort study.12,13 Figure 16-6 presents the refined and updated version of that caries risk assessment form for clients 6 years of age or older, which is composed of a hierarchy of disease indicators, risk factors, and protective factors (illustrated in Figure 16-7) that are based on the best scientific evidence available at this time.4 Use of this caries risk assessment form will be discussed later in the chapter.

Figure 16-6 Caries risk assessment form—children age 6 through adults.

(Redrawn from Featherstone JDB, Domejean-Orliaquet S, Jenson L Caries assessment in practice for age 6 through adult, J Calif Dent Assoc 35:704, 2007.)

(Redrawn from Featherstone JDB, Domejean-Orliaquet S, Jenson L Caries assessment in practice for age 6 through adult, J Calif Dent Assoc 35:705, 2007.)

The goal of caries risk assessment for clients 6 years old or older is to assign a client to a caries risk level for development of future caries as the first step in managing the disease process. This assessment occurs in two phases. First, the clinician assesses an individual's caries disease indicators, risk factors, and protective factors. Second, the clinician then determines the level of caries risk (low, moderate, high, or extreme) based on the presence of caries disease indicators and the balance between pathologic and protective factors.4,5

Caries Disease Indicators

Caries disease indicators are four clinical observations from the clinical examination that indicate past caries history and activity.4 The four caries disease indicators are listed in Box 16-2. Clinicians indicate the presence of each of these caries disease indicators by circling a positive response (i.e., “yes”) on the caries risk assessment form (see Figure 16-6).

Presence of any one of these four indicators automatically places the client at high caries risk unless therapeutic interventions are already in place and disease progress has been arrested. The presence of any one of these caries disease indicators in the presence of inadequate salivary flow automatically indicates extreme cares risk.3

Caries Risk Factors

Caries risk factors are biologic factors that contribute to the level of risk for developing new carious lesions in the future or having the existing lesions progress. Risk factors are things clinicians can do something about. There are nine risk factors recently identified in studies of caries risk assessment, and these are listed on the caries risk assessment form in Figure 16-6.4

These nine pathologic risk factors are as follows:

These risk factors also help us to understand why the person may have an ongoing caries problem. If there are no clinical signs of caries disease indicators, the caries risk status (low, moderate, high, or extreme) is determined by the balance between the pathologic factors and protective factors described in the following section (see Figure 16-7).

Caries Protective Factors

Caries protective factors are biologic or therapeutic factors that can collectively offset the challenge presented by the caries risk factors. The more severe the risk factors, the more protective factors are needed to keep the patient in balance or to reverse the caries process.

Currently the following 11 protective factors are included on the caries risk assessment form in Figure 16-64:

Use of the Caries Risk Assessment Form

Procedure 16-1 describes how to use the caries risk assessment form. Box 16-3 summarizes the criteria for high caries risk, and Box 16-4 lists the criteria for extreme caries risk, both for ages 6 years and older. Box 16-5 provides information on clients in this same age group who are considered to be at moderate caries risk.

Procedure 16-1 USE OF THE CARIES RISK ASSESSMENT FORM

STEP 1

Based on data obtained from the health histories and clinical examination, circle the Yes categories in the three columns on the form presented in Figure 16-6.

STEP 2

Make notations regarding the number of carious lesions present, the oral hygiene status, the brand of fluorides used, the type of snacks eaten, and the names of medications or drugs causing dry mouth.

STEP 3

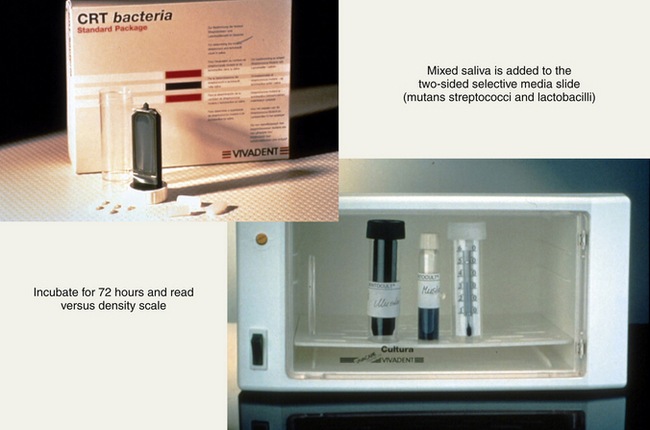

If the answer is Yes to any one of the four disease indicators in the first column, then take a bacterial culture using the Caries Risk Test (see Procedure 16-2) (Vivadent, Amherst, New York) or an equivalent test.

STEP 4

Make an overall judgment as to whether the client is at low, moderate, high, or extreme risk depending on the balance between the disease indicators or risk factors and the protective factors using the caries balance concept. (Clients who have a current caries lesion or had one in the recent past are at high risk for future caries. Clients who are at high risk and have severe salivary gland hypofunction or special needs are at extreme risk and require very intensive therapy. If the client is not at high or low risk, then he or she by default is at moderate risk.)

BOX 16-3 Criteria for High Caries Risk: Ages 6 Years and Older to Adult

BOX 16-4 Criteria for Extreme Caries Risk: Ages 6 Years and Older to Adult

Same as high caries risk but with saliva-reducing factors, including the following:

BOX 16-5 Moderate Caries Risk: Ages 6 Years and Older to Adult

If you cannot decide whether a client is at high caries risk or low caries risk, then the client should be considered to be at moderate caries risk.

Salivary Flow Rate Test

If visually inadequate salivary flow is noticed, or if the client reports having a dry mouth, then a salivary flow rate test should be conducted (Procedure 16-2; see Figure 16-9). Saliva neutralizes acids and provides minerals and proteins that protect the teeth from dental caries. Therefore it is essential for controlling dental caries.

Procedure 16-2 TESTING SALIVARY FLOW RATE AND LEVEL OF CARIES BACTERIAL CHALLENGE

EQUIPMENT

STEP 1

STEP 2

∗ Tests have shown that 72 hours' incubation produces more reliable results than the 48 hours recommended by the manufacturer.

The reason for any low salivary flow rate needs to be determined to plan for caries management. The client should be informed of the results and their implications for dental caries.

Caries Bacteria Testing

If any one of the four disease indicators in the first column of the caries risk assessment form (see Figure 16-6) is present, then a bacterial culture should be taken.4,5 Currently there are several chairside tests available for caries bacteria testing. Procedure 16-2 describes use of an example bacterial test, the Caries Risk Test (Vivadent, Amherst, New York). This test allows a bacterial culture to be made from collected saliva and is sensitive enough to provide a level of low, medium, or high cariogenic bacterial challenge. The level of bacterial challenge is recorded in the client's record as low, medium, or high. The client is informed of the results and their implications for caries risk and caries management.

Results of this bacterial test also can be used to motivate client compliance with recommended antibacterial 4,5

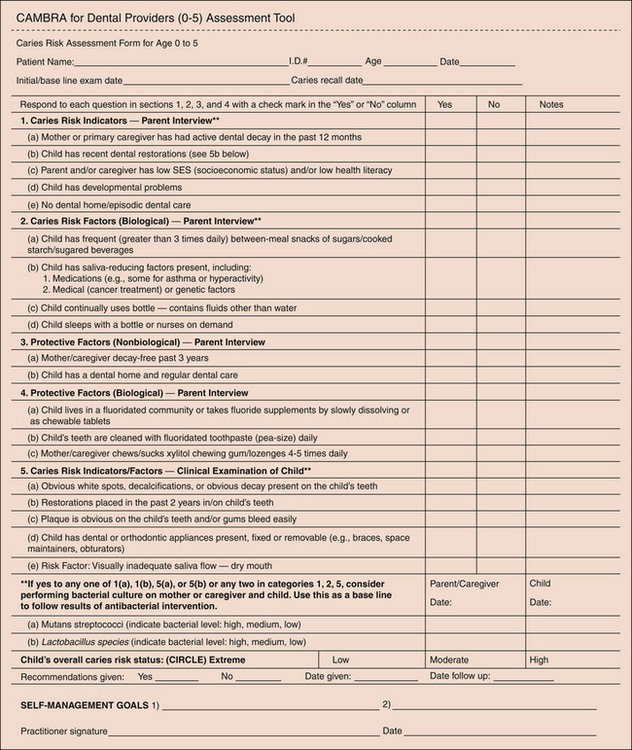

DENTAL CARIES RISK ASSESSMENT FOR CHILDREN 0 TO 5 YEARS OF AGE1

Early childhood caries (ECC) is an infectious disease that affects children from birth to 2 years of age and rapidly destroys newly erupted teeth. Initially ECC appears as bands of demineralized areas usually first seen on the primary maxillary incisors. These areas of demineralization quickly become yellow or brown cavitated areas7 (Figure 16-8, and see Chapter 53).

The cause of ECC is complex. The primary cause of demineralization in infants and toddlers primarily involves cariogenic bacteria and a diet high in fermentable carbohydrates. Mothers, caregivers, siblings, and other children transmit mutans streptococci to infants and young children. In addition, frequent or prolonged feedings with bottled milk, formula, human breast milk, fruit juice, or sugared drinks are highly cariogenic. Box 16-6 lists high caries risk factors for ages 0 to 5 years, and Box 16-7 lists protective factors for the same age group.

The American Dental Association (ADA), the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, and the American Association of Public Health Dentistry recommend all children have their first preventive dental visit by 12 months of age.14-16 Figure 16-10 presents the CAMBRA assessment form for 0- to 5-year-old infants and toddlers. The protocol for a comprehensive CAMBRA 0-to-5-years oral care visit includes the following components:

Sharing of bacterial results with parent or caregiver as the basis for treatment recommendations and to enhance motivation

Sharing of bacterial results with parent or caregiver as the basis for treatment recommendations and to enhance motivation

Figure 16-10 Caries risk assessment form for ages 0 to 5.

(Redrawn from Ramos-Gomez FJ, Crall J, Gansky SA Caries risk assessment appropriate for the age 1 visit (infants and toddlers), J Calif Dent Assoc 35:687, 2007.)

Parent Interview

A parent interview is conducted before the child is examined to identify caries risk factors, disease indictors, and protective factors already in place. If the mother and/or caregiver has active decay, this automatically places the child at high risk owing to the high likelihood of bacterial transmission from parent or caregiver to child.1

Examination of the Child

The examination of the child completes the risk factor–disease indicator list. If the child has obvious decalcification (white spots) or cavities, this places the child at high risk for future caries.1

Assignment of Caries Risk Level

Once the risk factor list has been checked, the provider summarizes the risk factors and assigns a caries risk level (low, moderate, or high) based on the balance between pathologic and protective factors. Active decay in the parent or caregiver or in the child automatically places the child at high risk, signaling the need for antibacterial intervention and fluoride treatment for both the parent or caregiver and the child.1

Individualized Treatment Based on Skill Level

Strategies need to be employed to modify the maternal or caregiver transmission of cariogenic bacteria to infants through the potential use of chlorhexidine rinse, fluoride varnish, and xylitol-based products.1

Bacterial Culture

If assessments reveal the presence of high caries risk factors and disease indicators, then bacterial cultures of saliva collected from the parent or caregiver and child are indicated.1 If parents or caregivers have high cariogenic bacterial counts, they should be advised to seek appropriate dental care to reduce their caries risk and control their caries by eliminating the infection source and reducing the early infant inoculation.1

Individualized Homecare Recommendations

Once risk level is determined, the provider develops an individualized treatment plan, customizes homecare recommendations, engages the parent or caregiver in the process by conducting a motivational interview,17 involves the parent or caregiver in setting self-management goals, educates the parent or caregiver about age-specific interventions for prevention (anticipatory guidance), and determines the interval for periodic reevaluation.

Box 16-8 lists parent or caregiver caries prevention recommendations for children 0 to 5 years of age. Further information to assist in expansion of related knowledge and skills may be found on the First Smiles website, www.first5oralhealth.org, as part of a statewide oral health initiative regarding oral health of children 0 to 5 years old, funded by First 5 California and managed by the California Dental Association Foundation and the Dental Health Foundation.

CARIES MANAGEMENT (SEE CHAPTER 31)

Based on the level of caries risk determined, an evidence-based care plan is developed that includes specific behavioral, chemical, and minimally invasive preventive and therapeutic procedures to manage the individual's dental caries disease. Caries management is aimed at restoring and maintaining a balance between protective factors and pathologic factors (see Figures 16-59 and 16-7).4 Caries management involves the following:

Remineralizing early noncavitated carious lesions by enhancing salivary flow, using fluorides, and possibly using calcium and phosphate paste products, especially if the client is at extreme caries risk (e.g., low salivary flow)

Remineralizing early noncavitated carious lesions by enhancing salivary flow, using fluorides, and possibly using calcium and phosphate paste products, especially if the client is at extreme caries risk (e.g., low salivary flow) Surgically removing carious lesions that are beyond hope of remineralization and restoring the teeth with minimally invasive techniques and materials5

Surgically removing carious lesions that are beyond hope of remineralization and restoring the teeth with minimally invasive techniques and materials5Decreasing pathologic factors involves strategies such as client education, oral hygiene instruction, reduction of the intake of fermentable carbohydrates, and addition of the use of chlorhexidine rinse and/or xylitol gum.5 Box 16-9 summarizes guiding principles for caries management for high-risk individuals. Box 16-10 summarizes evidence-based therapeutic recommendations for individuals at high caries risk.

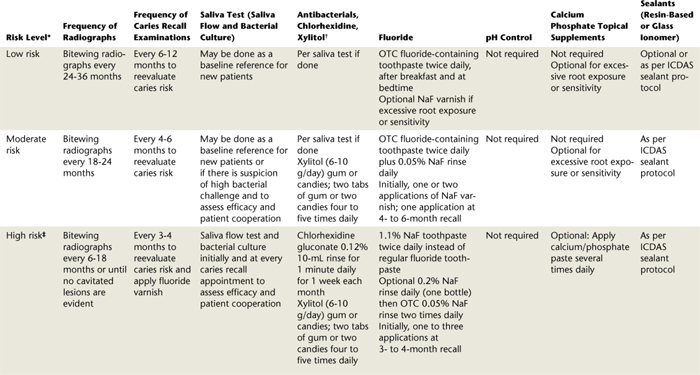

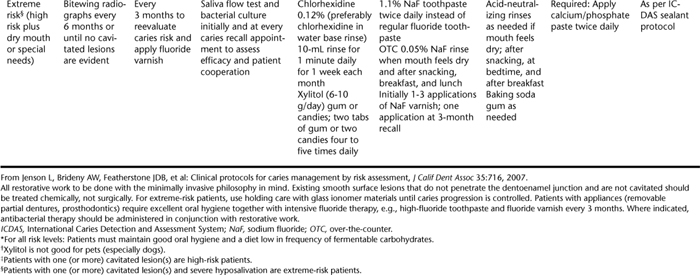

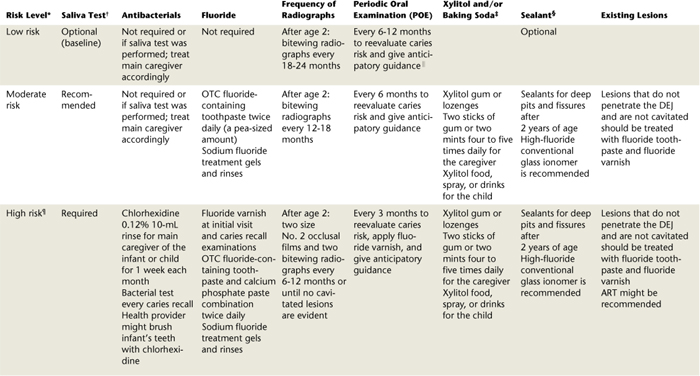

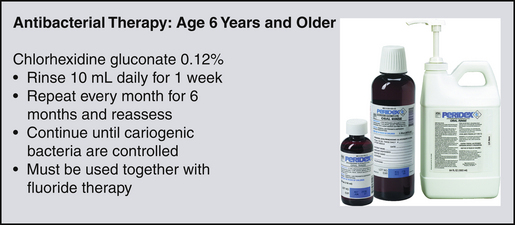

After determining the caries risk of an individual, the clinician provides the client with educational material about the caries process (see www.cdafoundation.org for a patient information sheet on tooth decay) and makes recommendations based on the caries risk status of the individual as determined by the balance or imbalance between the pathologic factors and the protective factors.4 Tables 16-1 and 16-2 provide clinical guidelines for caries management by risk assessment for clients age 6 years and older5 and 0 to 5 years,1 respectively. The client's compliance with recommendations is assessed 3 to 6 months after the initial visit. If bacterial levels were moderate or high at the initial visit, bacterial assessment is repeated to see if they have been reduced. Recommendations should be modified or reinforced based on bacterial results and patient compliance.4,5 Chemical therapy is employed to adjust the imbalance between the pathologic factors and the protective factors in order to reverse or halt the progression of dental caries toward cavitation. Such chemical therapies are discussed later. The evidence base for products used to treat and prevent dental caries should be evaluated and considered before such products are used in practice.

FLUORIDE THERAPIES

Fluoride is a naturally occurring element that is present in many minerals, water supplies, and foods. Fluoride that is delivered to the tooth surface and the plaque biofilm can have a dramatic caries preventive and reparative effect if delivered at the right concentrations.

Primary Mechanisms of Fluoride Action

Fluoride works primarily and most effectively via topical (surface) mechanisms (whether delivered in the drinking water, foods, beverages, or products) to inhibit demineralization, enhance remineralization, and inhibit plaque bacteria.8,11

Inhibition of Demineralization

Fluoride present on the tooth surface and in plaque fluid inhibits acid demineralization by reducing the solubility of the tooth mineral.8,11

Enhancement of Remineralization

Fluoride accelerates the remineralization process by adsorbing to mineral crystals within the tooth and attracting calcium ions. In addition, fluoride ions incorporate into the remineralizing tooth structure, resulting in the development of fluorapatite-like crystals. These crystals are less soluble than the original enamel mineral and make remineralized lesions less susceptible to future demineralization. Fluoride levels in the mouth from fluoridated water are sufficient to enhance remineralization. Fluoridated water has primarily a topical effect.

Topical Fluoride

Beyond the fluoride in drinking water and some beverages, topical fluorides are taken into the oral cavity in the following three primary forms:

Typically the topical fluoride agents available as self-applied fluoride agents for at-home use are lower in fluoride concentration than those that are applied professionally. In general, the following guidelines apply:

High-concentration products are referred to as high-potency and are typically applied less frequently.

High-concentration products are referred to as high-potency and are typically applied less frequently.Self-Applied Dentifrices

Other than the fluoride consumed in drinking water, dentifrices are the most widely used fluoride preparations. ADA-approved fluoride dentifrices for caries prevention provide sufficiently large concentrations of fluoride to facilitate enamel remineralization (Figure 16-11).8,11 The majority of commercial dentifrices available in the United States contain around 1000 parts per million (ppm) fluoride. Some manufacturers produce higher-strength dentifrices that contain up to 1500 ppm fluoride. Most over-the-counter dentifrices marketed in the United States contain one of the following:

Figure 16-11 Sample sodium fluoride dentifrices that have the American Dental Association Seal of Acceptance for dental caries prevention.

(Courtesy Dr. Mark Dillenges.)

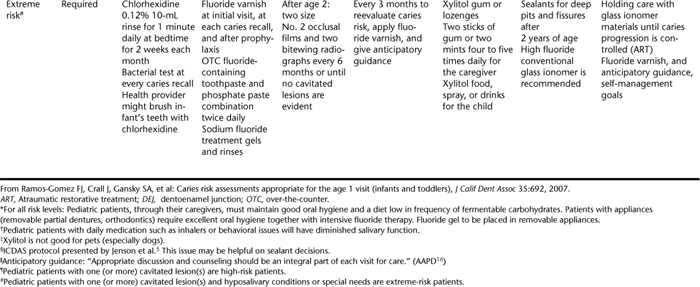

Brushing twice daily with a fluoride-containing dentifrice is one of the most effective ways to control dental decay. Numerous clinical trials report around 30% reduction in caries incidence with fluoride dentifrice containing 1000 to 2800 ppm fluoride.8 Curnow and colleagues18 reported 56% reduction with supervised brushing twice daily compared with unsupervised brushing. High–fluoride concentration fluoride products such as 5000 ppm fluoride toothpaste are more effective than 1100 ppm fluoride in high–caries-risk individuals and are proven effective for root caries prevention.8,19 Such high fluoride concentration dentifrices require a prescription from a dentist and are usually available in the dental office. Figure 16-12 shows examples of high-concentration prescription fluoride products for high–caries-risk individuals. Baysan and colleagues19 reported that 5000 ppm fluoride toothpaste gave statistically significant extra reduction in root caries compared with 1100 ppm fluoride toothpaste. Caries progression, however, still occurred in many subjects even with high concentration fluoride use. Thus, a very high bacterial challenge in high–caries-risk individuals overcomes the therapeutic effect of fluoride and requires use of additional chemical agents to promote protective factors. (For more information on fluoride dentifrices, see Chapter 23).

Because carbohydrate and bacterial challenges create daily opportunities for demineralization, the frequent use of additional low-potency fluoride products for the daily management of the caries disease process is recommended.9 Various other delivery vehicles for fluoride products are available for those individuals whose caries activity or caries risk warrants the use of additional fluoride agents to augment use of an approved fluoride dentifrice.2,4,5 These systems are discussed later.

Self-Applied Daily Fluoride Mouth Rinses

Low-potency fluoride rinses are available as over-the-counter products. For example, 0.05% NaF rinses have a fluoride concentration of approximately 230 ppm. These products are used as an adjunct to brushing with a fluoride dentifrice. Over-the-counter fluoride rinses (0.05% NaF or 0.4% stannous fluoride; Figure 16-13) are very effective when used once or twice daily for 1 minute, along with a fluoride-containing dentifrice.9,11 Individuals are educated to use the metered dose of the rinse from the bottle, to vigorously swish the rinse in the mouth, and then to thoroughly expectorate. Because there is a risk for young children to swallow fluoride rinses, this product is not recommended for children under 6 years of age. For the same reason, fluoride rinses should be stored out of the reach of young children.1

Figure 16-13 Sample of over-the-counter 0.05% NaF rinses with the ADA Seal of Acceptance.

(Courtesy Dr. Mark Dillenges.)

Self-applied fluoride gels also may be used in addition to a fluoride-containing dentifrice to manage dental caries. Like the rinses, the majority of the gels are of low- to mid-range potency and as such are administered with higher frequency. The scientific literature indicates that both low-potency fluoride rinses and gels reduce caries by 30% to 35%.8,9

Fluoride gels are marketed as stannous fluoride (SnF2) products at 1000 ppm, neutral (NaF), and acidulated phosphate fluoride (APF) products at 5000 ppm. These products are designed for daily use and are typically brushed on the teeth after toothbrushing with a conventional fluoride dentifrice.11 In cases in which increased duration of contact with the teeth is desired, the 5000 ppm products are used in custom trays (Figure 16-14). Because there is a risk for young children to swallow fluoride gels, these products are not recommended for children under 6 years of age. Although there are very few studies documenting their efficacy, the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs approved SnF2 gels. In addition, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved SnF2 gels for sale over the counter because they contain the same fluoride concentration as conventional dentifrices. Stannous gels do not contain abrasives and should not be substituted for dentifrices that achieve pellicle and stain removal.11

Figure 16-14 Single arch trays.

(Courtesy Dental Hygienist News, funded by an educational grant from Procter & Gamble, Cincinnati, Ohio, and published by Harfst Associates, Inc, Troy, Michigan.)

Neutral and APF gels (5000 ppm) are used for individuals with extreme caries risk resulting from the administration of radiation for head and neck cancers, those with systemic medical conditions, and those who routinely use medications that reduce salivary flow. These products are available as gels without abrasives and as gels with abrasives (marketed as prescription dentifrices). Although the 5000 ppm gels lack ADA Council on Scientific Affairs approval, these products have gained widespread use for individuals with special needs. Careful client education is required when these products are recommended for unsupervised home use. The products should be used as directed in a custom tray or brushed on the teeth, swished in the oral cavity for 1 minute, and then expectorated. Clients should be reminded that these products are available by prescription owing to their moderate levels of fluoride, and therefore they should be carefully stored out of the reach of children.11

Professionally Applied Fluoride (In-Office Administration)

Forms of professionally applied topical fluoride supported by evidence of clinical effectiveness for caries prevention include the following20:

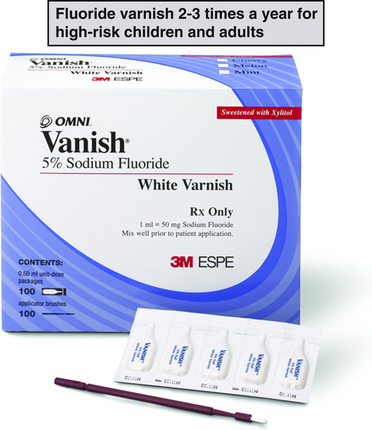

Figure 16-16 Example of fluoride varnish product for high-risk individuals of all ages.

(Courtesy OMNI Preventive Care, St Paul, Minnesota.)

Evidence-based general clinical recommendations are listed in Box 16-10.20

Gels

Commonly used professionally applied fluoride gels include APF, which contains 1.23% or 12,300 ppm fluoride ion, and 2% NaF, which contains 9.90% or 9050 ppm fluoride ion. Professionally applied fluoride gels are typically delivered using a tray technique, are one of the last procedures performed in the dental hygiene appointment sequence, and are administered by licensed dental professionals. These high-potency topical fluoride systems have been approved by the FDA for in-office use and have a caries reduction rate of approximately 30%.20 Of the two products, the 1.23% APF system is the most widely researched and used. The 2.0% neutral NaF is the second most widely used and is recommended when it is inappropriate to use an acidulated product (when a client has a tooth-colored restoration and/or dentinal hypersensitivity). Tray selection21 and the procedure for administering a professional topical fluoride gel using the tray technique are presented in Chapter 31.

Varnishes

Fluoride varnish is a concentrated topical fluoride with a resin or synthetic base that is painted on the teeth to prolong fluoride exposure. It can be used instead of a fluoride gel for risk categories as shown in Table 16-1 (see Figure 16-16). Based on evidence from systematic review of randomized controlled trials, the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs states that two or more applications of fluoride varnish per year are effective in preventing caries in high-risk populations and that fluoride varnish applied every 6 months is effective in preventing caries in the primary and permanent dentition of children and adolescents.20,22-24

Fluoride-containing varnishes typically contain 5% NaF, which is equivalent to 2.26% or 22,600 ppm fluoride ion. Fluoride varnish applications take less time, create less client discomfort, and achieve greater client acceptability than does fluoride gel, especially in preschool-aged children as well as infants and toddlers.1,20 In addition, fluoride varnish contains a smaller quantity of fluoride compared with fluoride gels. Therefore its use reduces the risk of inadvertent ingestion in children younger than 6 years.20 The frequency of application for fluoride varnish should be determined by the client's caries risk. (See Chapter 31 for the procedure for placing fluoride varnish.)

Client Selection

Based on the CAMBRA approach to care, professionally applied fluoride gel application at 3- to 6-month intervals is recommended for individuals with moderate, high, and extreme caries risk (see Table 16-1).

Product Selection

Once it is determined that a client will benefit from a professionally applied topical fluoride treatment, the dental hygienist decides the type of high-potency fluoride that will be used for this procedure. The choice is among neutral NaF gel, APF gel, or fluoride varnish based on clinician and client preference. (There is limited evidence to support effectiveness of the fluoride foam for caries prevention.)

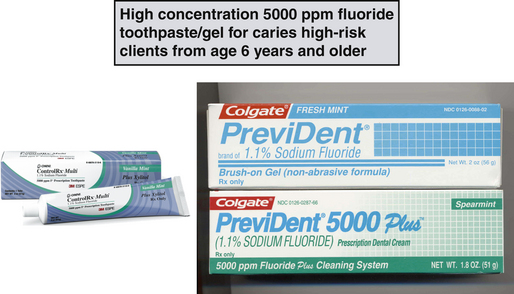

CHLORHEXIDINE AS AN ANTIBACTERIAL FOR DENTAL CARIES

Chlorhexidine gluconate is a broad-spectrum antibacterial agent that works by opening up the cell membranes of the bacteria. It is administered in the United States by prescription. In the United States, only 0.12 % chlorhexidine gluconate is available as an antibacterial mouth rinse in the dental treatment setting for the management of both dental caries and periodontal diseases (Figure 16-17). For high-risk and extreme-risk individuals, use of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate rinse for 1 minute daily for 1 week each month is recommended to reduces mutans streptococci and lactobacilli levels in the plaque biofilm4,5 (see Table 16-1). Chlorhexidine therapy will reduce the bacterial challenge but must be used in conjunction with fluoride remineralization therapy as described in detail previously.

In high–bacterial-challenge individuals, this therapy needs to be continued for approximately 1 year and monitored by bacterial assessment. Problems associated with this compound are that it affects taste, and compliance is often poor.4,5 Staining can also be a problem with some individuals if used for longer than 1 week at a time.

CALCIUM AND PHOSPHATE PRODUCTS

Products are available to deliver additional calcium and phosphate for remineralization (Figure 16-18). Although calcium and phosphate levels present in healthy saliva are sufficient for remineralization, such products could be beneficial to a client with inadequate salivary flow.

OTHER ANTIBACTERIAL THERAPEUTICS

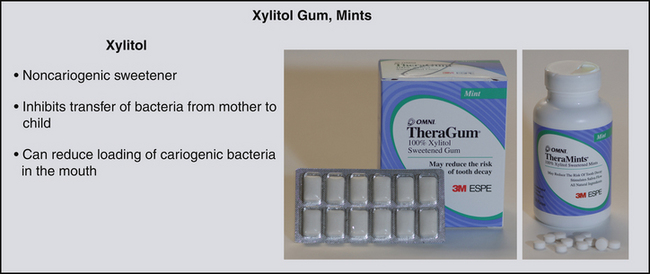

Xylitol

Xylitol is a sweetener that looks and tastes like sucrose. It inhibits attachment and transmission of bacteria and can be delivered through chewing gum or lozenges as an effective anticaries therapeutic measure (Figure 16-19). Xylitol is not fermented by cariogenic bacteria. In addition, use of xylitol chewing gum (or lozenges) serves the following functions:

Inhibits the transfer of bacteria from person to person by altering the way the bacteria stick to surfaces26

Inhibits the transfer of bacteria from person to person by altering the way the bacteria stick to surfaces26Two tabs of gum or two lozenges four to five times daily are recommended for moderate-, high-, and extreme-risk individuals for caries management (see Table 16-1).

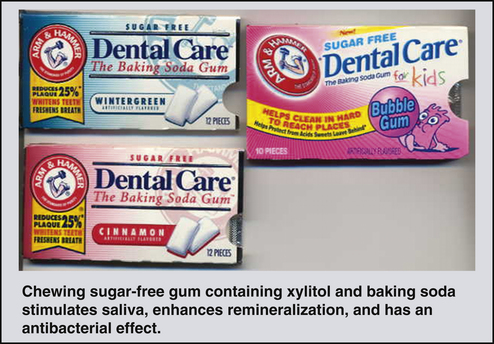

Sodium Bicarbonate

Sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) neutralizes acids produced by acidogenic bacteria and has antibacterial properties. It can be delivered to extreme-risk clients (those at high risk plus dry mouth or special needs) in gum or toothpaste or in a solution for individuals with low salivary flow5 (Figures 16-20 and 16-21; see also Table 16-1).

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Explain the importance of promoting oral flora to favor health; reducing or eliminating risk factors; enhancing salivary function where needed; enhancing the caries repair process by remineralization; and employing a minimally invasive approach when restorative treatment is needed.

Explain the importance of promoting oral flora to favor health; reducing or eliminating risk factors; enhancing salivary function where needed; enhancing the caries repair process by remineralization; and employing a minimally invasive approach when restorative treatment is needed. Explain that dental caries infections can be prevented and controlled with the help of the client and explain preventive and therapeutic choices.

Explain that dental caries infections can be prevented and controlled with the help of the client and explain preventive and therapeutic choices. Inform clients of their current caries risk status and provide an evidence-based care plan based on their level of risk as determined by the balance or imbalance between the pathologic factors and protective factors of each client.

Inform clients of their current caries risk status and provide an evidence-based care plan based on their level of risk as determined by the balance or imbalance between the pathologic factors and protective factors of each client. Explain that caries is an infection that can be transmitted from parent to child or from person to person.

Explain that caries is an infection that can be transmitted from parent to child or from person to person. Emphasize the frequent use of low-dose fluoride-containing products (dentifrices and oral rinses) to repair demineralized areas.

Emphasize the frequent use of low-dose fluoride-containing products (dentifrices and oral rinses) to repair demineralized areas. Teach parents and caregivers that they are critical partners in dental caries management in children under 6 years of age.

Teach parents and caregivers that they are critical partners in dental caries management in children under 6 years of age.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Make recommendations based on the caries risk status of the individual as determined by the balance or imbalance between the pathologic factors and protective factors of each client; and document in the client's chart.

Make recommendations based on the caries risk status of the individual as determined by the balance or imbalance between the pathologic factors and protective factors of each client; and document in the client's chart. Emphasize the safe use of self-applied products, especially with children younger than 6 years of age.

Emphasize the safe use of self-applied products, especially with children younger than 6 years of age. Document recommendations regarding self-applied products in the client record, including information regarding type of product, frequency of use, safe use and storage.

Document recommendations regarding self-applied products in the client record, including information regarding type of product, frequency of use, safe use and storage.KEY CONCEPTS

The team approach is essential for the successful caries management program, and the role of the dental hygienist can be critical in the overall management of the program.

The team approach is essential for the successful caries management program, and the role of the dental hygienist can be critical in the overall management of the program. Caries is defined as an infectious, transmissible disease process where a complex cariogenic biofilm, in the presence of an oral environmental status that is more pathologic than protective, leads to the demineralization and eventual cavitation of dental hard tissues.

Caries is defined as an infectious, transmissible disease process where a complex cariogenic biofilm, in the presence of an oral environmental status that is more pathologic than protective, leads to the demineralization and eventual cavitation of dental hard tissues. Pathologic factors include cariogenic bacteria (Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus, and Lactobacillus species), frequent ingestion of fermentable carbohydrates (sugars and starches), and salivary dysfunction.

Pathologic factors include cariogenic bacteria (Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus, and Lactobacillus species), frequent ingestion of fermentable carbohydrates (sugars and starches), and salivary dysfunction. Protective factors include but are not limited to adequate saliva and its caries-preventive components, fluoride therapy, and antibacterial therapy.

Protective factors include but are not limited to adequate saliva and its caries-preventive components, fluoride therapy, and antibacterial therapy. Saliva plays a key role in that it neutralizes acids and provides minerals and proteins that protect the teeth.

Saliva plays a key role in that it neutralizes acids and provides minerals and proteins that protect the teeth. Risk factors are biologic, behavioral, or socioeconomic contributors to the caries disease process that can be modified as part of the care plan.

Risk factors are biologic, behavioral, or socioeconomic contributors to the caries disease process that can be modified as part of the care plan. Caries management is aimed at restoring and maintaining a balance between protective factors and pathologic factors. The overall aim of the care plan is to reduce the bacterial challenge; reduce or eliminate other risk factors; enhance salivary function where needed; enhance the repair process by remineralization; and employ a minimally invasive approach when restorative treatment is needed.

Caries management is aimed at restoring and maintaining a balance between protective factors and pathologic factors. The overall aim of the care plan is to reduce the bacterial challenge; reduce or eliminate other risk factors; enhance salivary function where needed; enhance the repair process by remineralization; and employ a minimally invasive approach when restorative treatment is needed. High- and extreme-risk individuals require antimicrobial therapy, reduction of identified risk factors, and remineralization therapy. Extreme-risk individuals with severe salivary dysfunction require additional therapy, such as the use of buffering agents and calcium and phosphate supplementation.

High- and extreme-risk individuals require antimicrobial therapy, reduction of identified risk factors, and remineralization therapy. Extreme-risk individuals with severe salivary dysfunction require additional therapy, such as the use of buffering agents and calcium and phosphate supplementation. Moderate-risk individuals require improved remineralization therapy and reduction of other risk factors, which may include antimicrobial therapy.

Moderate-risk individuals require improved remineralization therapy and reduction of other risk factors, which may include antimicrobial therapy. Caries management includes treatment of the bacterial infection that causes dental caries, rather than just treatment of the carious lesion.

Caries management includes treatment of the bacterial infection that causes dental caries, rather than just treatment of the carious lesion. Caries management involves suppressing bacteria that cause the infection; remineralizing early noncavitated carious lesions by enhancing salivary flow and using fluorides; protecting tooth surfaces by using sealants and fluorides; decreasing the frequency of sugar intake, especially between meals; and referring to the dentist for surgical removal of carious lesions that are beyond hope of remineralization and for restoration of teeth with minimally invasive techniques and materials.

Caries management involves suppressing bacteria that cause the infection; remineralizing early noncavitated carious lesions by enhancing salivary flow and using fluorides; protecting tooth surfaces by using sealants and fluorides; decreasing the frequency of sugar intake, especially between meals; and referring to the dentist for surgical removal of carious lesions that are beyond hope of remineralization and for restoration of teeth with minimally invasive techniques and materials. Levels of cariogenic bacteria in the mouth can be assessed by selective media culturing in the dental office. Saliva that is stimulated by chewing can be used to collect bacteria from the teeth and around the mouth.

Levels of cariogenic bacteria in the mouth can be assessed by selective media culturing in the dental office. Saliva that is stimulated by chewing can be used to collect bacteria from the teeth and around the mouth. Chlorhexidine is used as a mouth rinse (10 mL once daily for a 2-week period every 2 to 3 months). In individuals with high bacterial challenge, this therapy will need to be continued for approximately 1 year and monitored by bacterial assessment.

Chlorhexidine is used as a mouth rinse (10 mL once daily for a 2-week period every 2 to 3 months). In individuals with high bacterial challenge, this therapy will need to be continued for approximately 1 year and monitored by bacterial assessment. Demineralization is an issue from the time the primary dentition erupts into the oral cavity until death or the permanent teeth are prematurely lost.

Demineralization is an issue from the time the primary dentition erupts into the oral cavity until death or the permanent teeth are prematurely lost. Various self-applied dentifrices, rinses, and gels are available, and the market continues to expand in this area.

Various self-applied dentifrices, rinses, and gels are available, and the market continues to expand in this area.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Sue works as a dental hygienist in a large group practice that employs a total of three full-time dental hygienists. This general practice is located in a town that has had community water fluoridation for the past 30 years; nearly all of the clients treated in the office reside in the town. Sue is providing a preventive appointment for a 5-year-old client. The client is new to the practice; her mother is waiting for her in the reception area. The client has the following dental history:

The office policy is that professionally applied fluorides (tray technique) are administered to all children (3 to 16 years of age) two times annually. As Sue nears the end of her appointment, she explains to the client that she is going to administer a fluoride treatment; the client has never had this procedure before. Sue asks the client what flavor fluoride she would prefer: tooty-fruity, strawberry, or double chocolate. The client says that she loves chocolate, so she selects the double chocolate flavor.

Sue explains the 4-minute tray application to the client, the use of the saliva ejector, and the need to avoid swallowing fluoride during the treatment. Sue selects a small, hinged fluoride tray and fills it two thirds full with 1.23% APF. Sue then dries the teeth, inserts both trays concurrently, inserts the saliva ejector, and begins timing the treatment for 4 minutes. Sue remains chairside during the treatment and distracts the client by talking about her favorite sport.

As Sue removes the fluoride trays, the client immediately begins talking about how much she liked the taste of the double chocolate fluoride. Sue says that she is glad that the client enjoyed her first fluoride treatment and hopes she will look forward to the next appointment in 6 months.

Sue prepares to dismiss the client and return with her to the reception area to talk with the client's mother. As Sue and the client entered the reception area, the client reports to her mother that her stomach “does not feel good” and that she thinks she might “be sick.”

Refer to the Procedures Manual where rationales are provided for the steps outlined in the procedures presented in this chapter.

1. Ramos-Gomez F.J., Crall J., Gansky S.A., et al. Caries risk assessment appropriate for the age 1 visit (infants and toddlers). J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:687.

2. Young D.A., Featherstone J.D.B., Roth J.R., et al. Caries management by risk assessment: implementation guidelines. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:799.

3. Featherstone J.D.B., Adair S.M., Anderson M.H., et al. Caries management by risk assessment: consensus statement, April 2002. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2003;31:257.

4. Featherstone J.D., Domejean-Orliaguet S., Jenson L., et al. Caries risk assessment in practice for age 6 through adult. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:703.

5. Jenson L., Brideny A.W., Featherstone J.D.B., et al. Clinical protocols for caries management by risk assessment. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:714.

6. Gutkowski S., Gerger D., Creasey J., et al. The role of dental hygienists, assistants, and office staff in CAMBRA. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:786.

7. Horowitz H.S. Decision-making for national programs of community fluoride use. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:321.

8. Stookey G.K. Caries prevention. J Dent Educ. 1998;62:803.

9. Featherstone J.D.B. The science and practice of caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:887.

10. Zero D.T. Dental caries process. Dent Clin North Am. 1999;43:635.

11. Featherstone J.D.B. Prevention and reversal of dental caries: role of low level fluoride. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999;27:31.

12. Featherstone J.D.B., Gansky S.A., Hoover C.I., et al. A randomized clinical trial of caries management by risk assessment. Caries Res. 2005;39:295.

13. Domejean-Orliaguet S., Gansky S.A., Featherstone J.D. Caries risk assessment in an educational environment. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:1346.

14. American Dental Association (ADA). ADA statement on early childhood caries 2004. Chicago: ADA, 2004. Available at: hwww.ada.org/prof/resources/positions/statements/caries.asp.Accessed August 17, 2008.

15. American Association of Public Health Dentistry. First oral health assessment policy. Springfield, Ill: American Association of Public Health Dentistry, 2004 (May 4). Available at: www.aaphd.org/default.asp?page=policy.htm. Accessed August 17, 2008.

16. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD). Policy on the dental home. Chicago: AAPD, 2004 (rev). Available at: www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_DentalHome.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2008.

17. Weinstein P. Provider versus patient-centered approaches to health promotion with parents of young children: what works/does not work and why. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:172.

18. Curnow M.M.T., Pine C.M., Burnside G., et al. A randomized controlled trial of the efficacy of supervised toothbrushing in high–caries-risk children. Caries Res. 2002;36:294.

19. Baysan A., Lynch E., Ellwood R., et al. Reversal of primary root caries using dentifrices containing 5000 and 1100 ppm fluoride. Caries Res. 2001;35:41.

20. American Dental Association (ADA) Council on Scientific Affairs. Professionally applied topical fluoride: evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Dent Educ. 2007;71:393.

21. Lavigne S. Not all trays are created equal: an analysis of fluoride tray fit. Probe Sci J. 2000;34:217.

22. Marinho V.C., Higgins J.P., Logan S., et al. Topical fluoride (toothpastes, mouthrinses, gels or varnishes) for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents [review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2003. CD002782

23. Moberg Sköld U., Petersson L.G., Lith A., et al. Effect of school-based fluoride varnish programmes on approximal caries in adolescents from different caries risk areas. Caries Res. 2005;39:273.

24. Weintraub J.A., Ramos-Gomez F., Jue B., et al. Fluoride varnish efficacy in preventing early childhood caries. J Dent Res. 2006;85:172.

25. Ekstrand J., Fejerskov O., Silverstone L.M. Fluoride in dentistry. Copenhagen: Munsgaard; 1988.

26. Söderling E., Isokangas P., Pienihäkkinen P., et al. Influence of maternal xylitol consumption on acquisition of mutans streptococci by infants. J Dent Res. 2000;79:882.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..