CHAPTER 53 Women's Health and the Health of Their Children

Gender bias, preference given to members of one gender over another, has been evident in the history of medicine and healthcare. Research on drugs and diseases has been performed primarily on middle-aged white men, even though sex, age, and race and ethnicity profoundly influence life span, drug efficacy, and risk of disease. For example, little is known about why women live longer than men, are more likely to develop autoimmune diseases, metabolize drugs differently, and manifest brain tissue variation that may influence mood, healing, and disease susceptibility. Scientists have long known of the anatomic differences between the sexes, but only within the past decade have they begun to uncover significant biologic and physiologic differences.1 Sex-based biology is the study of biologic and physiologic differences between men and women. Sex differences are apparent in the composition of bone matter, the experience of pain, the metabolism of certain drugs, and the rate of neurotransmitter synthesis in the brain.

Some women lack the education and self-esteem necessary to advocate for their own healthcare. Limited access to healthcare results in suffering and premature loss of life, especially among women of color and the poor. In the United States, more than 80% of heads of one-parent households are women responsible for securing healthcare for themselves and their children. Even with these constraints, women access the healthcare system more than twice as often as men.

LINKS BETWEEN ORAL AND SYSTEMIC HEALTH (SEE CHAPTER 18)

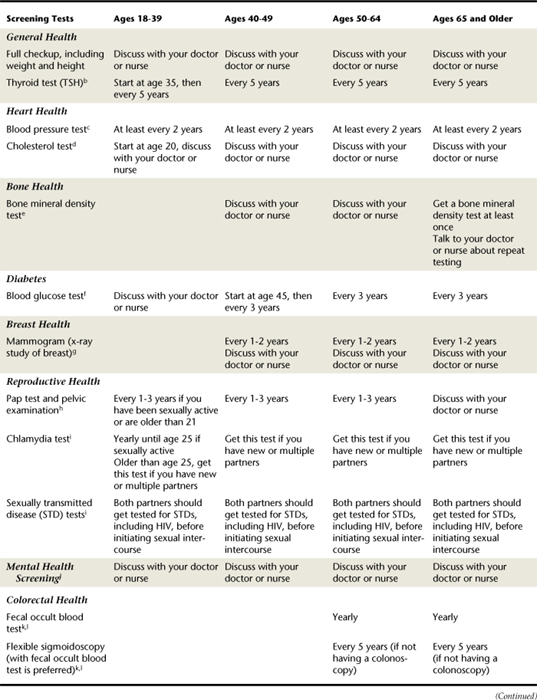

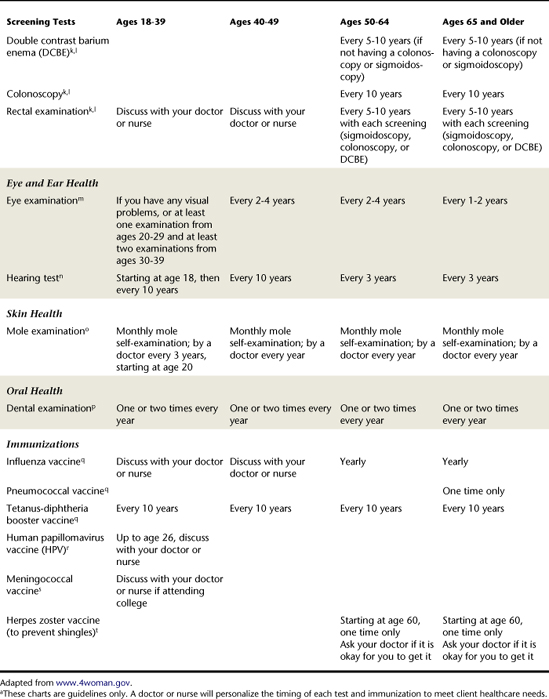

Research evidence links periodontal disease with cardiovascular disease (CVD), valvular heart disease, preterm low-birthweight (PLBW) babies , and bacterial pneumonia. Moreover, several conditions are risk factors or risk indicators for periodontal disease: type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, stress, depression, financial difficulties, social isolation, and other distress-related, psychosocial factors. Table 53-1 provides a guide for counseling women on comprehensive healthcare; nutrition information for women's health is discussed in Chapter 33.

WOMEN AND HEART DISEASE

Although young women rarely get heart disease, it is the number one killer of women older than 60. Under age 60, one in three men develop heart disease versus one in 10 women. A woman's risk rises at menopause but does not equal a man's until about 10 years later. It is surprising to note that heart disease is more severe among women over 60 than among men of the same age; women are twice as likely as men to die within 60 days of having a heart attack and are less likely to survive coronary bypass surgery. It appears that high levels of triglycerides may elevate a woman's risk of heart disease, but there is no evidence that triglycerides have the same effect in men. In 2007, preliminary data from two Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trials showed an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with postmenopausal hormone therapy.2 Postmenopausal hormone treatments can double the risk of developing VTE, and in recent years hormone prescriptions have declined, partly as a result of this finding.

Women may not exhibit the typical signs of a heart attack. In a woman a heart attack may be signaled by indigestion, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, breathlessness, back pain, or deep throbbing in the left or right bicep or forearm, rather than the chest pain typically observed in men experiencing a cardiac arrest (see Chapter 42).3,4

SIGNIFICANT LIFE EVENTS

Women need health information on the following:

Women may need tobacco cessation and nutritional counseling; blood pressure and cholesterol level screening; promotion of exercise for at least 10 minutes three times daily or 30 minutes three times a week; weight control; and stress reduction. Other significant women's health issues include eating disorders, autoimmune diseases, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and estrogen replacement therapy (ERT), incontinence, and domestic violence.

Puberty and Menses5,6

Puberty and menses are marked by the development of secondary sex characteristics throughout the body and increased estrogen level. The bacteria associated with increased estrogen levels (Prevotella species and Tannerella forsythensis, formerly Bacteroides forsythus) have been implicated in periodontal disease. Irregular ovulations usually occur for the first 1 to 2 years before the start of menstruation. Endogenous sex steroid hormone gingival disease, which includes puberty-associated gingivitis and menstrual cycle gingivitis, may occur as estrogen and progesterone levels rise. These gingival diseases are classified as plaque-induced gingival diseases modified by systemic factors (see Chapter 17, Box 17-4). The body reacts to bacterial challenges differently, depending on the integrity of the immune system. The host response appears to be altered in the presence of increased sex steroid hormones, suggesting an effect of these hormones on the immune system.

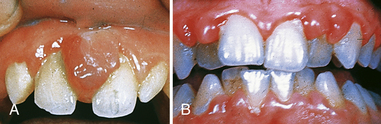

Swollen, erythematous gingival tissues may be present, as well as herpes labialis and aphthous ulcers, prolonged hemorrhage after oral surgery, and swollen salivary glands. Minor increases in tooth mobility may be seen, along with an increase in gingival exudate. These transient changes are attributed to peak levels of estrogen and progesterone (Figure 53-1).

Although sex steroid hormone effects may be transient, irreversible oral damage could result if proper self-care is lacking. Dental hygiene preventive strategies during puberty and menses include stressing optimal oral hygiene via increased frequency and duration of toothbrushing with an extrasoft toothbrush or a power toothbrush and meticulous interdental cleaning (see Chapters 21 and 22). Therapeutic modalities include topical corticosteroids; frequent periodontal debridement, scaling, and root planing; antimicrobial mouth rinses; and fluoride rinses and gels. Painful oral manifestations of puberty and menses, although disconcerting and uncomfortable, can be managed with topical viscous lidocaine, Orahesive, or Zilactin-B, and systemic analgesics such as aspirin or ibuprofen.

Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives are widely used by women of childbearing age (Box 53-1). Risks associated with oral contraceptives include gingival inflammation, exaggerated gingival inflammatory response to local irritants, increase in bacterial pathogens, and spotty melanotic pigmentation of the skin and gingiva. Periodontal pathogens (Prevotella species and Tannerella) increase, fed by estrogen and progesterone from oral contraceptives circulating in the blood. Oral contraceptives induce folate deficiency, which inhibits oral tissue repair and decreases blood clotting, especially in women over 35 who smoke. Other side effects may include the following:

BOX 53-1 Examples of Some Oral Contraceptives

From Medline Plus, last revised 07/08/2007.

In light of these side effects, women may consider using other methods of birth control for a specific time period if surgery is necessary.

Childbearing Years and Pregnancy

All women of childbearing age should be informed of the critical importance of preventive care so that they may attain optimal oral health before pregnancy and maintain that level of oral health throughout their lives (Box 53-2). A prenatal oral disease prevention program may include increased frequency of periodontal debridement; effective brushing and interdental cleaning (see Chapters 21 and 22), at-home fluoride therapy (see Chapter 31), twice daily antimicrobial rinses (see Chapter 29), use of xylitol-containing products, nutritional counseling (see Chapter 33), tobacco cessation, and infant oral care to prevent early childhood caries (ECC) (see Chapters 16 and 31). ECC is prevented by inhibiting Streptococcus mutans infection of the infant's oral flora in conjunction with avoiding prolonged exposure of the primary teeth to fluids containing sugar. (See section on infant and child care later in this chapter.)

BOX 53-2 Advice to Female Clients of Childbearing Age

During the first trimester of pregnancy (period of organogenesis, when vital organs form), the fetus is most susceptible to environmental risk factors. Ideally no drug or illegal substances should be used during pregnancy, especially during the first trimester, when the fetus is at greatest risk. However, there are situations in which drugs are necessary and appropriate to maintain the health of the mother. In those situations drugs classified as category A or B by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are preferred (Table 53-2). Drugs taken during pregnancy and lactation should be used at the lowest effective dose and shortest duration to minimize harmful effects on the fetus or infant. When pregnant women are treated, if any doubt about any drug, procedure, or client condition is present, the obstetrician of record is consulted.

TABLE 53-2 U.S. Food and Drug Administration Categories of Drugs and Their Implication for Use during Pregnancy

In the last half of the third trimester, the uterus is very sensitive to external stimuli, and the hazard of premature delivery exists. In a semireclined or supine position, the enlarged uterus compresses the inferior vena cava. This interferes with venous return, causing postural hypotension, decreased cardiac output, and, if prolonged, eventual loss of consciousness. Placing the pregnant woman on her left side while she receives dental hygiene care removes pressure on the vena cava and allows blood to return from the lower extremities and pelvic area.

Nitrous Oxide–Oxygen Analgesia Use during Pregnancy7-9

An anxiolytic agent is a drug used to reduce anxiety. Use of the anxiolytic nitrous oxide–oxygen (N2O-O2) analgesia in pregnancy has not been assigned a rating by the FDA, but studies demonstrate increased congenital anomalies, altered immune responses, spontaneous abortion, and increased birth defects with prolonged exposure during pregnancy, making the use of N2O-O2 a potential occupational hazard for members of the dental team. Scavenging systems, when properly installed and maintained, are effective in reducing ambient N2O concentration in the oral care environment, a significant improvement for pregnant members of the dental team. Exposure should be no longer than 50 ppm N2O in the air for longer than 8 hours per week.

Few anxiolytics are safe during pregnancy; however, a single exposure to N2O-O2 analgesia for no more than 30 minutes is considered to be safe.7,8 An obstetrician should be consulted before this analgesic is administered to a pregnant client (see Chapter 40).

Drug Intake during Lactation

Little conclusive evidence exists about drug dosage during lactation and its effects on the nursing infant because so few studies are done on pregnant or lactating women. The amount of drug excreted in breast milk is usually 1% to 2% of the maternal dose. Therefore it is unlikely that most drugs taken by the lactating mother have any pharmacologic significance for the infant. It is prudent for the mother to take the drug just after breast-feeding and then avoid nursing for the required number of hours based on the drug's half life. To prevent the passage of drugs from mother to infant, lactating mothers should avoid epinephrine, aspirin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin (Cipro), metronidazole (Flagyl), gentamicin, vancomycin, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and diazepam (Valium). Epinephrine is contraindicated in lactating women because it is excreted in breast milk. If a local anesthetic with epinephrine must be used, the woman should wait 9 hours before breast-feeding her baby. Because of its rapid diffusion from the body, N2O-O2 analgesia is considered safe for lactating women and hence their nursing infants.

Alcohol Intake during Pregnancy

All clients, especially those who are pregnant, should be asked about drug, alcohol, and tobacco habits and educated about cessation options (see Chapters 34 and 51). Pregnant women should be cautioned about alcohol use because their babies could be born with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), characterized by damage to the offspring's central nervous system that affects motor skills, skin and muscle innervation, and behavior aspects of the personality. The risk of FAS in babies of women who drink heavily (five or more drinks a day) is 35%. The risk to women who drink moderately (three to four drinks per day) is 10%. The risk for women who drink less than that is unknown; however, it is known that some damage, not full FAS, can occur with light drinking or a single binge (five or more drinks at one sitting). Characteristics of persons with FAS include short palpebral fissures, a flat midface, an indistinct philtrum, and a thin upper lip. Other less-frequent characteristics may include epicanthal fold, a low nasal bridge, a short nose, ear anomalies, and microdontia (Figure 53-2).

Radiographic Exposure during Pregnancy

The developing fetus is especially susceptible to the effects of radiation. However, safety features in use such as high-speed film, filtration, long cone rectangular collimation, and lead aprons significantly decrease radiation exposure. Diagnostic radiographs are not harmful to the pregnant woman or the fetus when she is properly protected by a lead shield with a thyroid collar and when current standards for radiation safety are maintained. It has been proven that when a lead apron is used, an exposed full-mouth series of dental radiographs results in no detectable radiation exposure to the embryo or fetus. Digital radiography may decrease risk even further, as this system uses less radiation than traditional film.

According to The Guidelines for Prescribing Dental Radiographs, radiograph exposure recommendations do not need to be altered because of pregnancy.10 Pregnant dental personnel must use the usual necessary precautions when taking radiographs, that is, wear a lead apron, stand more than 6 feet from the tube head, stand at 90 to 130 degrees to the beam (preferably behind a protective wall), and monitor exposure by wearing a radiation exposure badge (dosimeter).

Oral Manifestations during Pregnancy

Erosion of the lingual, occlusal, incisal, or facial surfaces of the teeth occurs when the enamel is decalcified and softened by gastric acids (see Chapter 52Figure 52-2Figure 52-3Figure 52-4Figure 52-5Figure 52-6). Perimylolysis, acid erosion of teeth, is rare in pregnancy but may occur if a woman vomits repeatedly from severe morning sickness. Subsequent mechanical abrasion may occur when the tongue or toothbrush moves against the teeth. Clients at risk for tooth erosion should be advised to rinse with water immediately after vomiting and before brushing teeth. An acid-neutralizing preparation of one quart of water mixed with one teaspoon of baking soda is recommended for mouth rinsing after vomiting. At-home daily-use fluoride rinses or gels, xylitol-containing gums or mints, amorphous calcium phosphate–containing products, or other remineralizing products may also be recommended to prevent demineralization of tooth structure.

Pregnancy-associated gingivitis, a sex steroid hormone gingival disease most common in the second trimester of pregnancy, is characterized by an exaggerated host response to oral biofilm. The gingiva may appear fiery red and edematous at the marginal gingiva and interdental papillae, with loss of tissue resiliency. Tissues may be smooth and shiny, bleed easily, and display increased probing depths. These gingival changes occur earlier and more frequently in the anterior than in the posterior areas (see Figure 53-1 and Chapter 17, Box 17-3). Pregnancy-associated gingivitis usually reaches maximum severity during the eighth month and is less severe after childbirth. However, the tissue may not return to a state of health.

As the most prevalent oral manifestation of pregnancy, pregnancy-associated gingivitis is due to poor oral hygiene, high plasma hormone levels, and an increase in bacteria associated with periodontal disease. The inflammatory response is exacerbated by hormonal and vascular changes and the presence of increased anaerobic bacteria that proliferate in the high-progesterone environment during pregnancy. The marked increase in Tannerella during pregnancy seems to be associated with increased serum levels of the circulating sex steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen and progesterone serve as bacterial nutrients and increase gingivitis during pregnancy. Both hormones have been shown to substitute for naphthoquinone, an essential growth factor for Tannerella and Prevotella intermedia. Because bacteria can metabolize progesterone as a nutrient, pregnancy favors the colonization of anaerobic bacteria in the gingival sulcus.

When plasma levels of estrogen and progesterone increase, progesterone and estrogen accumulate in gingival tissues. Human gingiva has receptors for progesterone and estrogen. Progesterone causes a dilation of the gingival capillaries, increasing their permeability and thus increasing gingival exudate, edema, and accumulation of inflammatory cells. It is important to note that estrogens are primarily responsible for vascular changes in other target tissues such as the uterus, yet increased vascular permeability and exudate in the gingiva are essentially the result of progesterone. Tooth mobility is sometimes present in pregnant women and may be related to disturbances in the attachment apparatus. One theory contends that mobility may be related to mineral changes in the lamina dura and not due to alteration of the alveolar bone. Tooth mobility usually reverses or declines after the birth of the baby.

Pregnancy granulomas (pyogenic granulomas) are single, tumorlike, soft-tissue growths, typically on the interdental papilla, most often on the labial aspect of the maxillary anterior gingiva; however, bone destruction is rare (Figure 53-3). These granulomas are pedunculated (attached via a stem), with intense red to deep-purple color, depending on the vascularity of the lesion and the degree of blood stagnation. Usually no larger than 2 cm, the granulomas are painless and may bleed readily if disturbed. Occurring in less than 10% of all pregnancies, usually abating after delivery, the lesions are often related to poor oral hygiene and the general effects of progesterone and estrogen on the host immune system. These progesterone-influenced effects inhibit collagenase, the enzyme that breaks down collagen, resulting in the accumulation of collagen within the connective tissue. Typically, granulomas are excised after delivery; however, situations may dictate immediate removal when the granuloma is painful to the client or when it disturbs tooth alignment, is cosmetically unacceptable, or bleeds easily. If excision is necessary, the second trimester is optimal because of low risk to the fetus during this time. If excised during pregnancy, the granuloma may recur; therefore clients should be advised that an additional surgical procedure may be needed postpartum.

Sex Steroid Hormones and the Inflammatory Process

Prostaglandins, mediators (facilitators) of the inflammatory process, have been shown to increase significantly in the presence of high concentrations of estrogens and progesterones, such as during pregnancy. In addition to stimulating bacterial growth, sex steroid hormones stimulate key factors in the inflammatory response.

Depressed immune function occurs during pregnancy. The maternal immune mechanism is weakened to protect the fetus from rejection; the host resistance of the mother to certain diseases, including inflammatory periodontal disease, is also altered. Progesterone and estrogen have been shown to affect the immune system. Neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis and antibody and T-cell responses are depressed in the presence of high levels of sex hormones during a normal pregnancy. Pregnancy also inhibits the migration of inflammatory cells and fibroblasts to the site of injury or insult.

Progesterone functions as an immunosuppressant in the gingival tissues of pregnant women, resulting clinically in an exaggerated appearance of inflammation. As a result, this immunosuppression prevents the rapid, acute inflammatory reaction against oral biofilm and allows for increased chronic inflammation to occur.

Infertility Treatment

Infertility treatment may also affect the oral cavity. Ovulation induction is the most common method of infertility treatment in which the ovaries are stimulated to produce multiple follicles. One study assessed the effects of three ovulation induction drug protocols: clomiphene citrate (CC) alone, CC combined with follicle-stimulating hormone, and CC combined with human menopausal gonadotropin on the gingival tissues of women who were undergoing infertility treatment.11 The researchers concluded that ovulation induction exacerbates gingival inflammation, gingival bleeding, and gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) volume and that the duration of the use of these drugs is strongly associated with severity of gingival inflammation. Educating clients undergoing ovulation induction about these findings protects the creation of new life and helps to maintain optimal oral and systemic health.

Preterm, Low-Birthweight Infants and Periodontal Status (see Chapter 18)

Research evidence indicates that periodontal infection is a possible risk factor for preterm, low-birthweight (PLBW) babies. Women with periodontal disease are more likely to have PLBW babies than women without the disease. Twenty-five percent of PLBW cases occur without any known risk factors. Studies demonstrate an association between infection and PLBW babies, specifically genitourinary infections. Infections cause a faster-than-normal increase in the levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α, molecules that induce labor. PGE2 is similar in chemical structure to Pitocin (oxytocin), a drug used to induce labor. Other risk factors for PLBW babies include maternal age, cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and drug abuse; multifetal pregnancies; medical problems of the mother such as hypertension; diabetes mellitus; infections; heart, kidney, or lung problems; and an abnormal placenta, uterus, or cervix. With proper precautions, dental care is safe and effective during pregnancy.

Menopause

Menopause begins 10 years before the cessation of the menses (menstruation) and continues for about 10 years after. Perimenopause consists of the years immediately preceding menopause; postmenopause consists of the years after menopause. Most investigators believe that the physical changes accompanying menopause are primarily a result of decreased estrogen production by the ovaries and possibly an increased secretion of gonadotropins, the hormones of the anterior pituitary gland that stimulate the gonads. After menopause, estradiol, the most potent naturally occurring estrogen, ceases to be the major circulating estrogen and is replaced by estrone, which is less potent and demonstrates no cyclic changes. Menopause is accompanied by a number of changes attributed to a variety of geriatric, hormonal, and psychosomatic factors. Estrogens promote maturation and keratinization of vaginal mucosa. In menopause there is a decrease in keratinization and atrophy of the vaginal mucosa associated with a decline in estrogen level.

Oral Manifestations of Menopause12

Thinning of the oral epithelial lining and decreased keratinization, oral discomfort such as burning sensations of the tongue (glossodynia), altered taste perception (salty, peppery, sour), xerostomia, and alveolar bone loss associated with osteoporosis are some of the oral changes observed in menopause.13 Most menopausal women with oral discomfort are relieved by systemic or topical estrogen. Oral mucosae, like vaginal mucosae, are stratified squamous epithelium, and similar desquamative patterns are observed. Human gingiva has specific protein receptors for estrogen; therefore estrogens may stimulate the proliferation of gingival fibroblasts and maturation of connective tissue, mainly through their influence on collagen production. Studies have been unable to demonstrate a correlation between ovarian hormone levels and changes in the oral mucosa during menopause.

Oral healthcare providers may have clients whose chief complaint is burning and painful sensations in the oral cavity. Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is also known as glossodynia, stomatodynia, glossopyrosis, stomatopyrosis, or oral dysesthesia. BMS is not the temporary discomfort that many people experience after eating irritating or acidic foods. BMS is characterized by a burning sensation in the oral cavity even though the oral mucosae appear clinically normal. About 1 million people in the United States are affected by these sensations, and they are increasingly problematic in the aging population. Eighty percent of women with BMS are postmenopausal. The most prevalent site with burning sensations is the anterior tongue. The pain is chronic (at least 6 months), continuous, and progressive throughout the day, with no apparent cause. Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain, facial pain, oral sores, and burning mouth are associated with this syndrome.

Nutritional deficiencies, such as deficiencies of iron, zinc, folate (vitamin B9), thiamin (vitamin B1), riboflavin (vitamin B2), pyridoxine (vitamin B6) and cobalamin (vitamin B12), may affect oral tissues and cause BMS. These nutritional deficiencies can also lead to vitamin deficiency anemia. BMS could also be due to allergies or reactions to foods, food flavorings, other food additives, fragrances, dyes, or other substances.

Middle-aged women are particularly affected by the condition and are diagnosed with symptoms seven times more frequently than males. Various local, systemic, and psychologic factors may be associated with BMS, but its cause is not fully understood. Identification of symptoms, rather than objective clinical or laboratory findings, is often used to assess this condition. Therefore treatment addressing these factors has had limited success.

Treatment for BMS is usually directed at correction of detected organic causes or involves the use of tricyclic antidepressants, such as chlorpromazine. Interventions may include instruction in proper oral hygiene, saliva-stimulating agents such as pilocarpine HCl , over-the-counter (OTC) xylitol-containing gum or mints, or OTC saliva substitutes depending on the severity of the salivary dysfunction. Antifungal therapy is necessary if candidiasis is diagnosed. In severely distressed persons, local or systemic corticosteroids may be indicated. Lifestyle changes such as refraining from tobacco and alcohol use, dietary modifications, and avoiding toothpastes containing sodium lauryl sulfate should be initiated. Future treatment might include agents combining antibacterial and anti-inflammatory actions that show promising effects in clients with oral mucosal diseases secondary to salivary hypofunction.

Hormone Replacement Therapy13-17

Hormone replacement therapy is the daily taking of the female hormone estrogen or progesterone to control the negative effects of menopause. Controversy surrounds the risks and benefits of HRT, and individual characteristics and preferences may influence decisions to use this therapy. Estrogen replacement therapy is estrogen alone, used by women who have had the uterus removed. Estrogen's effects on bone health and mental well-being are recognized.

A WHI study examined a large group of women on combination HRT (estrogen 0.625 mg/day plus progestin 2.5 mg/day) compared with a matched group of women on placebo. However, at about the same time that the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS I and II) reported no increased risk of CVD-related events for women on HRT, the HRT component of the WHI was halted because of the increased incidence of CVD (22%) and breast cancer (26%) in women treated with combination HRT compared with placebo.16 The risk of stroke was also significantly higher in the HRT group, accounting for a 41% increase.

The WHI trials found no benefit in the use of HRT as a means of primary or secondary prevention of future CVD events.17 Results of HERS II and the halting of the HRT component of the WHI all point to the same conclusion: HRT is not beneficial in preventing heart disease or stroke and should not be used in postmenopausal women for the sole purpose of heart disease prevention. Moreover, this conclusion is officially endorsed by the American Heart Association. Increased risks linked with HRT relate to 5 or more years of use. Risks associated with HRT follow18-22:

Screening mammograms are less accurate in women who use HRT than in nonusers, increasing the risks of both false-negative and false-positive results.

Screening mammograms are less accurate in women who use HRT than in nonusers, increasing the risks of both false-negative and false-positive results. Progestin added to HRT substantially increases breast cancer risk relative to the use of estrogen alone.

Progestin added to HRT substantially increases breast cancer risk relative to the use of estrogen alone. Women with hypothyroidism being treated with thyroxine may need an increased dose if they begin taking estrogen therapy.

Women with hypothyroidism being treated with thyroxine may need an increased dose if they begin taking estrogen therapy. Women with uterus and taking estrogen alone, without the addition of progesterone, are at increased risk for endometrial (uterine) cancer.

Women with uterus and taking estrogen alone, without the addition of progesterone, are at increased risk for endometrial (uterine) cancer.Benefits associated with HRT follow:

The HRT pill and patch have positive, similar effects on the tightness or constriction of blood vessels, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)—the “bad” cholesterol.

The HRT pill and patch have positive, similar effects on the tightness or constriction of blood vessels, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)—the “bad” cholesterol. Estrogen supplemented with calcium and vitamin D has a positive, dose-related effect on bone mineral density.

Estrogen supplemented with calcium and vitamin D has a positive, dose-related effect on bone mineral density.Estrogen's role in vascular biology and clinical medicine continues to evolve.

Oral Effects of HRT

Menopausal or postmenopausal women may experience changes in their mouths that may include the following:

Periodontal disease (estrogen supplementation in women within 5 years of menopause may slow progression of periodontal disease)

Periodontal disease (estrogen supplementation in women within 5 years of menopause may slow progression of periodontal disease) Gingivostomatitis (may affect small percentage of women; gingivae appear dry or shiny, bleed easily, and range from abnormally pale to deep red; HRT relieves these signs)

Gingivostomatitis (may affect small percentage of women; gingivae appear dry or shiny, bleed easily, and range from abnormally pale to deep red; HRT relieves these signs)HRT is associated with reduced gingival inflammation and a reduced frequency of clinical attachment loss in osteopenic and osteoporotic women in early menopause. HRT may help protect teeth and does not place women at increased risk of developing TMJ disorders.

Osteoporosis23

Bone loss is associated with periodontal disease, menopause, and osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a loss of bone mass affecting 25 million Americans; more than 1.3 million fractures that occur each year in men and women are attributed to osteoporosis. With osteoporosis, more bone is being resorbed than formed. Age is the strongest correlate to bone loss, and menopause is the second strongest correlate. Osteoporosis is more prevalent among white and Asian women and those with early menopause, fair complexions, or small frames. Often osteoporosis is not detected until a fracture occurs. By this time, significant loss of bone mass has placed the client at risk for future fractures, despite the fact that the original fracture will heal.

Fast and painless tests can diagnose osteoporosis in its early stages: dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA or DXA), quantitative computed tomography (QCT), and radiographic absorptiometry (RA). The common x-ray film cannot be used to diagnose osteoporosis early because bone loss must reach at least a 30% level before it is detected radiographically.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation's Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis represents a major breakthrough in the way healthcare providers evaluate and treat people with low bone mass, osteoporosis, or fracture risks.23 These guidelines go beyond Caucasian postmenopausal women to include African American, Asian, Latina, and other postmenopausal women and address men age 50 and older for the first time. The Guide applies the algorithm on absolute fracture risk called FRAX. Also referred to as a 10-year fracture-risk model and 10-year fracture probability, FRAX estimates the likelihood of a person to break a bone because of low bone mass or osteoporosis over a period of 10 years.

Management of Osteoporosis

Treatment for osteoporosis includes decreasing risk factors and maximizing protective factors, that is, via a calcium- and vitamin D–rich diet plus supplementation (see Chapter 33, Boxes 33-9 and 33-10), weight-bearing exercises, HRT, and drug therapy such as raloxifene (Evista), calcitonin, and sodium fluoride. Evista, a monaminobiphosphonate, inhibits bone breakdown and has been approved by the FDA for prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcitonin, FDA approved in injectable and nasal forms, slows bone breakdown and reduces pain of fractures. Sodium fluoride has been used to stimulate bone formation in the vertebrae, treat osteoporotic spine fractures, and prevent fractures at that site.

ERT can decrease the rate of bone resorption, but it cannot replace lost bone. Estrogens affect bone indirectly by interacting with the hormones that control calcium metabolism. HRT has been shown to be beneficial for bone density and architecture. It retards bone loss in postmenopausal women, making bone fractures less likely. All risks and benefits must be evaluated before a woman starts any HRT.

New Risks with Osteoporosis Treatment

Bisphosphonates are a class of drugs used primarily to increase bone mass and reduce the risk for fracture in persons with osteoporosis. Bisphosphonates are also used to slow bone turnover in patients with Paget's disease of the bone and to treat bone metastases and lower elevated levels of blood calcium in patients with cancer. Seven FDA-approved bisphosphonates are aminobisphosphonates (nitrogen-containing): alendronate (Fosamax, Fosamax Plus D), etidronate (Didronel), ibandronate (Boniva), pamidronate (Aredia), risedronate (Actonel, Actonel with Calcium), tiludronate (Skelid), and zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa). An FDA Alert issued on January 7, 2007 (www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/bisphosphonates/default.htm) highlighted the possibility of severe and sometimes incapacitating bone, joint, and/or muscle (musculoskeletal) pain in persons taking bisphosphonates. Significant concern exists in dentistry about the risk of bisphosphonates in the development of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ). Although severe musculoskeletal pain is mentioned in the prescribing information for all bisphosphonates, the association between bisphosphonates and severe musculoskeletal pain may be overlooked by healthcare professionals, delaying diagnosis, prolonging pain and/or impairment, and necessitating the use of analgesics. Bisphosphonate-related ONJ includes numbness, tooth mobility, soft-tissue swelling, and sequestra of bones and lesions of exposed bone in the mylohyoid ridge that do not heal. Evidence on the risk of ONJ is very compelling for clients on intravenous bisphosphonate therapy. The long half-life of bisphosphonate in bones justifies the need for long-term studies on its safety. Some physicians recommend using raloxifine hydrochloride (Evista), because these have not been associated with ONJ and have been approved to prevent and treat osteoporosis. For individuals receiving oral bisphosphonates, care should include the following:

Eliminating disease (caries, gingival and periodontal disease) in order to reduce the need for future extractions or dental implants

Eliminating disease (caries, gingival and periodontal disease) in order to reduce the need for future extractions or dental implantsPractitioners should keep in mind that ONJ can develop in “at-risk” client after routine dental care.

The FDA is investigating reports of increased rates of atrial fibrillation that is life-threatening or results in hospitalization or disability. Researchers in two different studies of older women with osteoporosis treated with the bisphosphonate Reclast or Fosamax have raised questions about the association of atrial fibrillation with bisphosphonate use.24,25 In both studies the following occurred:

More women who received one of the bisphosphonates (Reclast, 1.3%; Fosamax, 1.5%) reportedly developed serious atrial fibrillation as compared with women who received placebo (Reclast study, 0.5%; Fosamax study, 1.0%).

More women who received one of the bisphosphonates (Reclast, 1.3%; Fosamax, 1.5%) reportedly developed serious atrial fibrillation as compared with women who received placebo (Reclast study, 0.5%; Fosamax study, 1.0%). The rates of all atrial fibrillation (serious plus nonserious) were not significantly different between groups treated with bisphosphonates versus placebo.

The rates of all atrial fibrillation (serious plus nonserious) were not significantly different between groups treated with bisphosphonates versus placebo.The FDA has reviewed some safety data and requested additional data to further evaluate the risk of atrial fibrillation in patients who take bisphosphonates.

Osteoporosis and Periodontal Bone Loss

Loss of teeth and residual ridge resorption are problems associated with oral bone loss. Several studies have linked oral bone loss with systemic bone loss; therefore osteoporosis may affect periodontal bone loss. For example, generalized bone loss from systemic osteoporosis might render jaws susceptible to accelerated alveolar bone resorption. Although osteoporosis is not a causative factor in periodontitis, it may affect the severity of the disease in pre-existing periodontitis and is probably important in the creation of a susceptible host.

HRT and ERT protect against osteoporosis.24 The Nurses' Health Study examined risk of tooth loss in relation to hormone use in 42,171 postmenopausal women and found that the risk of tooth loss was lower in women taking HRT or ERT. The risk of tooth loss was lower among postmenopausal hormone users, with the most substantial decrease occurring among current users; risk of tooth loss did not appear to change with duration of current or past estrogen use.26 In addition, greater loss of periodontal attachment is found in women with osteoporotic fractures than in normal women. As healthcare professionals, dental hygienists are alert to any rapid changes in alveolar bone, periodontal attachment level, and/or tooth mobility in postmenopausal women and make appropriate referrals for a medical diagnosis.

Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw27

As mentioned, bisphosphonates are a class of agents used to treat osteoporosis, Paget's disease, and malignant bone metastases. The efficacy of these agents in treating and preventing the significant skeletal complications associated with these conditions has had a major positive impact for patients and is responsible for the widespread use of the agents in medicine.26 Despite this benefit, ONJ has emerged as a significant complication in a subset of patients receiving these drugs. ONJ looks very much like osteoradionecrosis (ORN); however, involvement of the mandible is extremely rare in ORN but is more common in ONJ. Based on a growing number of case reports and institutional reviews, bisphosphonate therapy may cause exposed and necrotic bone that is isolated to the jaw. This complication usually arises after simple dentoalveolar surgery and significantly affects quality of life for most patients. This complication appears to be related to the long half-life of bisphosphonates, the profound inhibition of osteoclast function (prolonged reduction in bone turnover and bone remodeling), and reduced bone quality and strength.27 Conversely, a recent study states that intravenous bisphosphonate therapy strongly increases the risk of adverse jaw outcomes but that oral bisphosphonates tend to decrease the risk.28 Intravenous bisphosphonate is usually used to treat bone cancer or severe cases of osteoarthritis. The clinical implications seem to suggest a low incidence of ONJ, which should be assessed in the context of the clinical benefit of zoledronic acid therapy in reducing hip, vertebral, and nonvertebral fractures in an at-risk population. There is no evidence to suggest that healthy patients with osteoporosis who are receiving bisphosphonate require any special treatment beyond routine dental care or to support altering standard treatment practices, but the clinician must be aware of potential complications. A complete dental assessment (including dentures to ensure proper fit) and elimination of dental disease should be performed before initiation of bisphosphonate therapy; the dentist, dental hygienist, and physician should work collaboratively to ensure that benefits and risks are considered for each client.

Dental Implants and Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is not a likely risk factor for failure of osseointegrated dental implants. In fact, the placement of dental implants could aid in maintaining the height and density of alveolar bone. The act of chewing leads to more pressure on the alveolar bone, causing bone remodeling that minimizes or counteracts physiologic age-related bone loss. Osteoporotic bone does not heal differently than bone with more density (see Chapter 57).

INFANT AND CHILD CARE

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry recommends that a child's first dental examination occur when the first tooth appears or no later than the first birthday. To ensure that a child does not experience dental caries or gingivitis, effective oral hygiene routines should be established in infancy and continued throughout life. When a woman is pregnant, she is receptive to advice on the care of her unborn child. New mothers are also receptive in most cases and should be informed of the potential vertical transmission of oral microorganisms from themselves to their infants. The information in Box 53-3 can be shared with pregnant clients, parents, and caregivers of small children.

BOX 53-3 Strategies to Decrease Incidence of Early Childhood Caries

Early Childhood Caries

ECC is a preventable dental condition that can destroy the teeth of an infant or young child, can cause pain and disfigurement, and, if left to progress, is expensive to treat. ECC is caused by prolonged and repeated exposure of a tooth to fermentable carbohydrates, such as those contained in infant formula, milk, and fruit juice, which ferment in contact with S. mutans. The maxillary anterior teeth are the most susceptible to damage, but other teeth also may be affected. Long-term effects of ECC include a higher incidence of orthodontic problems and possible psychologic and social problems that affect children who suffer embarrassment over their appearance (see Box 53-3 and Chapter 14Figure 14-28Box 14-1Box 14-2).

Herpetic Infections

An infection prevalent in infants and young children is primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (herpes simplex virus [HSV]–1). Some of the symptoms of HSV-1 in infants include fever, crying, oral pain, and an unwillingness to eat or drink. Gingivae appear intensely red and painful, with blisters on the tongue and lips. Children can be infected with this herpesvirus by sharing toys, washcloths, towels, or toothbrushes with others who may be infected (home or daycare setting).

Parents with herpetic lip sores can infect their babies by mouth kissing. If a child is in daycare, toys, rattles, and sleeping mats should be wiped and cleaned at least twice a day with a diluted bleach solution to prevent transfer of pathogenic microorganisms.

For other women's healthcare issues, see Chapters 47 and 52 on autoimmune diseases and eating disorders, respectively.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Reassure client that information will be kept confidential, but that it is important to identify products used, including over-the-counter and prescription medications, vitamins, herbs, supplements, and alcohol, to ensure proper care.

Reassure client that information will be kept confidential, but that it is important to identify products used, including over-the-counter and prescription medications, vitamins, herbs, supplements, and alcohol, to ensure proper care. Maintenance of oral health by thorough daily toothbrushing, interdental cleaning, tongue cleaning, and use of an antimicrobial mouth rinse translates to a healthier mouth and body.

Maintenance of oral health by thorough daily toothbrushing, interdental cleaning, tongue cleaning, and use of an antimicrobial mouth rinse translates to a healthier mouth and body. Inform clients about warning signs of heart disease: shortness of breath, nausea, major fatigue, chest pain, mandibular pain, back pain, fainting spells, or gaslike discomfort.

Inform clients about warning signs of heart disease: shortness of breath, nausea, major fatigue, chest pain, mandibular pain, back pain, fainting spells, or gaslike discomfort.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Respect client confidentiality regarding issues such as oral contraceptives, reproductive health, and domestic abuse.

Respect client confidentiality regarding issues such as oral contraceptives, reproductive health, and domestic abuse. Advise clients that systemic antibiotic use can render oral contraceptives ineffective and that an alternative contraceptive method should be considered when antibiotics are taken.

Advise clients that systemic antibiotic use can render oral contraceptives ineffective and that an alternative contraceptive method should be considered when antibiotics are taken. Report suspected abuse to the proper authorities: child protective services within a Department of Social Services, Department of Human Resources, or Division of Family and Children Services. In some states, police departments also may receive reports of child abuse or neglect. Call Childhelp, 800-4-A-Child (800-422-4453), or the local Child Protection Agency. A listing of state toll-free child abuse reporting numbers can be found at http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/reslist/rl_dsp.cfm?rs_id=5&rate_chno=11-11172.

Report suspected abuse to the proper authorities: child protective services within a Department of Social Services, Department of Human Resources, or Division of Family and Children Services. In some states, police departments also may receive reports of child abuse or neglect. Call Childhelp, 800-4-A-Child (800-422-4453), or the local Child Protection Agency. A listing of state toll-free child abuse reporting numbers can be found at http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/reslist/rl_dsp.cfm?rs_id=5&rate_chno=11-11172. Take a complete health history, and ask specific questions about drugs, herbs, vitamins, fluoride, and other supplements. The safety of most natural or herbal remedies is unknown because they are not controlled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Take a complete health history, and ask specific questions about drugs, herbs, vitamins, fluoride, and other supplements. The safety of most natural or herbal remedies is unknown because they are not controlled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).KEY CONCEPTS

Women may have different risks for and symptoms of heart disease. Heart disease is more severe among women over 60 than among men of the same age, and women are twice as likely as men to die within 60 days of suffering a heart attack.

Women may have different risks for and symptoms of heart disease. Heart disease is more severe among women over 60 than among men of the same age, and women are twice as likely as men to die within 60 days of suffering a heart attack. Women are the fastest growing population of those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Women are the fastest growing population of those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Cancer, menopause, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, autoimmune diseases, and domestic abuse are important issues in women's heath and have systemic and oral implications.

Cancer, menopause, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, autoimmune diseases, and domestic abuse are important issues in women's heath and have systemic and oral implications. Diagnostic radiographs are not harmful to the pregnant woman or fetus when properly protected by a lead shield with a thyroid collar and when current standards of radiation safety are maintained.

Diagnostic radiographs are not harmful to the pregnant woman or fetus when properly protected by a lead shield with a thyroid collar and when current standards of radiation safety are maintained. Female dental personnel and the unexposed partners of male dental personnel have cause for concern about regular nitrous oxide–oxygen (N2O-O2) analgesia during pregnancy. Difficulty conceiving and birth defects have been documented to occur with its regular use.

Female dental personnel and the unexposed partners of male dental personnel have cause for concern about regular nitrous oxide–oxygen (N2O-O2) analgesia during pregnancy. Difficulty conceiving and birth defects have been documented to occur with its regular use. N2O-O2 analgesia is safe for use by lactating women; its use is limited to one 30-minute exposure for pregnant women and pregnant oral healthcare professionals because of risk of birth defects and spontaneous abortion.

N2O-O2 analgesia is safe for use by lactating women; its use is limited to one 30-minute exposure for pregnant women and pregnant oral healthcare professionals because of risk of birth defects and spontaneous abortion. Pregnancy-associated gingivitis is the most prevalent oral manifestation of pregnancy. It is often due to poor oral hygiene, local irritants, sex steroid hormones that serve as bacterial nutrients, and increases in Tannerella species and Prevotella intermedia.

Pregnancy-associated gingivitis is the most prevalent oral manifestation of pregnancy. It is often due to poor oral hygiene, local irritants, sex steroid hormones that serve as bacterial nutrients, and increases in Tannerella species and Prevotella intermedia. As estrogen levels increase, so does the prevalence of Tannerella species, P. intermedia, and gingivitis. Bacteria associated with increased estrogen levels have been implicated in periodontal disease.

As estrogen levels increase, so does the prevalence of Tannerella species, P. intermedia, and gingivitis. Bacteria associated with increased estrogen levels have been implicated in periodontal disease. Sex steroid hormones (estrogen and progesterone) appear to stimulate key factors in the inflammatory response.

Sex steroid hormones (estrogen and progesterone) appear to stimulate key factors in the inflammatory response. Women with periodontal disease are more likely to have preterm, low-birthweight babies than women without the disease, and the relationship appears to be dose-related.

Women with periodontal disease are more likely to have preterm, low-birthweight babies than women without the disease, and the relationship appears to be dose-related. Early childhood caries (ECC) is a preventable dental disease that can destroy the teeth of an infant or young child, can cause pain and disfigurement, and, if left to progress, is expensive to treat.

Early childhood caries (ECC) is a preventable dental disease that can destroy the teeth of an infant or young child, can cause pain and disfigurement, and, if left to progress, is expensive to treat. A prenatal oral prevention program for pregnant women could include increased frequency of periodontal debridement, effective brushing and interdental cleaning, use of xylitol-containing gum and mints, at-home fluoride rinses or gels, antimicrobial rinses, nutritional counseling, infant oral care, and prevention of ECC in preparation for the baby's arrival. Evidence supports the use of 0.12% chlorhexidine mouth rinse and xylitol-containing gum (1.55 g therapeutic dose) during the last 3 months of pregnancy and for 6 months after birth to decrease risk of Streptococcus mutans transmission from mother to infant.

A prenatal oral prevention program for pregnant women could include increased frequency of periodontal debridement, effective brushing and interdental cleaning, use of xylitol-containing gum and mints, at-home fluoride rinses or gels, antimicrobial rinses, nutritional counseling, infant oral care, and prevention of ECC in preparation for the baby's arrival. Evidence supports the use of 0.12% chlorhexidine mouth rinse and xylitol-containing gum (1.55 g therapeutic dose) during the last 3 months of pregnancy and for 6 months after birth to decrease risk of Streptococcus mutans transmission from mother to infant. Osteoporosis is not a causative factor in periodontitis but may affect the severity of the disease in pre-existing periodontitis and is probably important in the creation of a susceptible host. Loss of teeth and residual ridge resorption are associated with oral bone loss.

Osteoporosis is not a causative factor in periodontitis but may affect the severity of the disease in pre-existing periodontitis and is probably important in the creation of a susceptible host. Loss of teeth and residual ridge resorption are associated with oral bone loss. Osteoporosis is not a risk factor for failure of osseointegrated dental implants. Placement of dental implants could aid in maintaining height and density of alveolar bone.

Osteoporosis is not a risk factor for failure of osseointegrated dental implants. Placement of dental implants could aid in maintaining height and density of alveolar bone. Dental hygiene care should include counseling clients about prevention of disease and the oral-systemic link, referring to other healthcare providers for assessment and care, and providing tobacco cessation counseling.

Dental hygiene care should include counseling clients about prevention of disease and the oral-systemic link, referring to other healthcare providers for assessment and care, and providing tobacco cessation counseling.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Scenario 1: Amy, a 16-year-old female client, arrives for her continued-care appointment 2 months late, although she is scheduled every 6 months. After a review of her health, dental, and pharmacologic history, a clinical examination is performed to reveal plaque-induced gingivitis throughout with moderate to heavy bleeding (GI score, 2.0). No periodontal pockets are noted, and her self-care appears adequate. Because of her heavy gingival bleeding, the health history is reviewed again. Amy reiterates that she is not taking any medication, nor has she been diagnosed with any illnesses in the last 8 months.

Scenario 2: Margie Alexander, a 25-year-old female client, arrives for her 6-month periodontal maintenance appointment. Ms. Alexander's health history is noncontributory, other than that she is in her eleventh week of pregnancy. She had a full-mouth series of radiographs 1 year ago, and her chief complaint is pain in tooth 30. Clinical examination reveals 3- to 4-mm probing depths throughout and bleeding on probing in tooth 14-M (4 mm) and 2-D.

Scenario 3: The practicing dental hygienist is pregnant and concerned about her time in the oral care environment. The dental hygienist heard that exposure to radiation, chemicals in the office, N2O-O2, and ultrasonic scaling units may cause birth defects or spontaneous abortion.

Scenario 4: Rose Oliveri, a 50-year-old female client, visited the office after a 1-year hiatus. Her chief complaint is, “My teeth seem to be moving and I don't like it.” Her health history reveals that she is taking hormone replacement therapy (estrogen and progestin), a multivitamin, and numerous herbal supplements. Her oral examination reveals probing depths from 3 to 6 mm, with a GI score of 1.0. Her self-care appears to be adequate, with a PI score of 1.

1. Partnership for Gender-Specific Medicine at Columbia University: About us. Available at: http://cpmcnet.columbia.edu/dept/partnership/aboutus.html. Accessed October 10, 2008.

2. Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators: Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. Available at: http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/reprint/288/3/321. Accessed October 10, 2008.

3. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute: The heart truth. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/hearttruth. Accessed June 2, 2008.

4. Mosca L., Banka C.L., Benjamin E.J. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481.

5. Amar S., Chung K. Influence of hormonal variation on the periodontium in women. Periodontology. 2000;6:79. 1994

6. Sutcliffe P. A longitudinal study of gingivitis and puberty. J Periodont Res. 1972;7:52.

7. Crawford J.S., Lewis M. Nitrous oxide in early pregnancy. Anaesthesia. 1986;41:900.

8. Little J.W., Falace D.A., Miller C.S., Rhodus N.L. Dental management of the medically compromised patient, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

9. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Anesthetic gases: guidelines for workplace exposures. Washington, DC: OSHA Directorate for Technical Support, Office of Science and Technical Assessment; 2000.

10. Eastman Kodak Company Guidelines for prescribing dental radiographs. Available at: www.kodakdental.com/documentation/film/N-80APrescribRadiographs.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2008.

11. Haytaç M.C., Cetin T., Seydaoglu G. The effects of ovulation induction during fertility treatment on gingival inflammation. J Periodontol. 2004;75:805.

12. Rhodus N.L., Myers S., Bowles W., et al. Burning mouth syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Northwest Dent. 2000;79:21.

13. Rossouw J.E., Anderson G.L., Prentice R.L., et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321.

14. Hully S., Grady D., Bush T., et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women: Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605.

15. Grady D., Herrington D., Bittner V., et al. Cardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study Follow-up (HERS II). JAMA. 2002;288:49.

16. Prentice R.L., Chlebowski R.T., Stefanick M.L., et al. Estrogen plus progestin therapy and breast cancer in recently postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2003;289:3243.

17. Wassertheil-Smoller S. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on stroke in postmenopausal women—the Women's Health Initiative: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2673.

18. Nelson H.D., Humphrey L.L., Nygren P., et al. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:872.

19. Humphrey L.L., Chan B.K., Sox H.C. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:273.

20. Nelson H.D., Humphrey L., LeBlanc E., et al. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy for primary prevention of chronic conditions: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2002.

21. Mosca L., Collins P., Herrington D.M., et al. Hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2001;104:499.

22. Hammond C, Wild R, Fiorica R: Straight talk on HRT: benefits and limitations. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewprogram/271. Accessed December 18, 2002.

23. National Osteoporosis Foundation: Disease statistics “fast facts.” Available at: www.nof.org/osteoporosis/stats.html. Accessed June 2, 2008.

24. Black D.M., Delmas P.D., Eastell R. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1809.

25. Lyle K.W., Colón-Emeric C.S., Magaziner J.S., et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799.

26. Grodstein F., Colditz G.A., Stampfer M.J. Post-menopausal hormone use and tooth loss: a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:370.

27. Ruggiero S.L., Drew S.J. Osteonecrosis of the jaws and bisphosphonate therapy. J Dent Res. 2007;86:1013.

28. Grbic J.T., Landesberg R., Lin S.Q. Incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis in the Health Outcomes and Reduced Incidence with Zoledronic Acid Once Yearly Pivotal Fracture Trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:32.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..