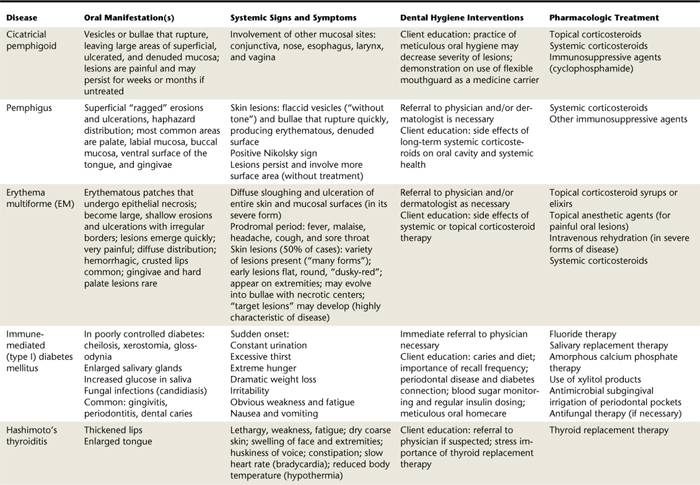

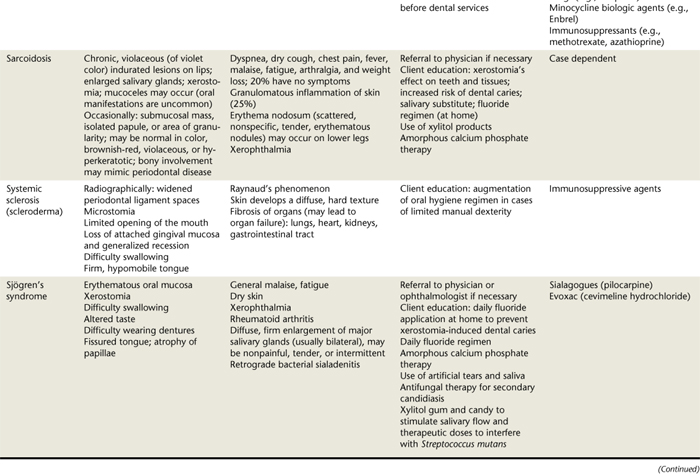

CHAPTER 47 Persons with Autoimmune Diseases

The immune system under normal circumstances differentiates the body’s own cells and tissues from foreign substances. In autoimmune diseases, this recognition breaks down and certain body cells are no longer tolerated; the immune system treats them as antigens. Genetic factors may predispose to autoimmune disease, and viral infection also may be involved.1 This chapter describes select autoimmune diseases (Table 47-1), manifestations of each, and dental hygiene interventions necessary to manage clients successfully.

PEMPHIGUS

Pemphigus represents four related autoimmune diseases: pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus erythematosus, and pemphigus foliaceus. Of the four diseases, only the first two affect the oral mucosa with any degree of frequency, pemphigus vegetans being the rarer of the two.1

Pemphigus vulgaris is a severe, progressive autoimmune disease that affects the skin and mucous membranes. It is characterized by bullae, circumscribed, elevated, fluid-filled lesions (blisters). These blisters form from the breakdown of cellular adhesion between epithelial cells. The blisters rupture soon after they form into painful ulcers that range in size from small to very large. Although the most common of the pemphigus disorders, pemphigus vulgaris is not seen very often. Annually, only one to five cases per million population are diagnosed. If the condition is untreated, the result is often death. If treated with systemic corticosteroids and/or other immunosuppressive drugs, the mortality rate is about 8% to 10% in 5 years. These deaths are usually the result of complications from long-term systemic corticosteroid use.1 Average age at diagnosis is 50 years; childhood cases are rare. No gender predilection has been observed; however, the condition is more common in persons of Jewish ancestry.

Clinical Features

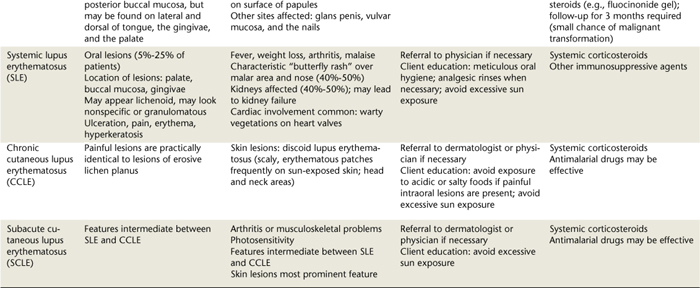

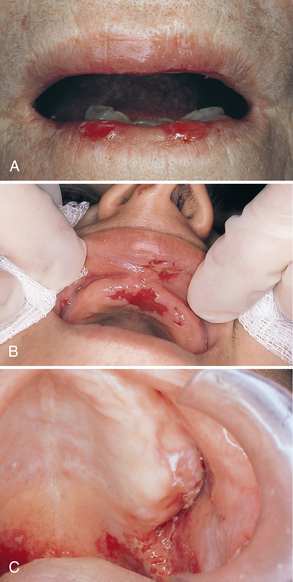

Oral lesions are often the first sign of the disease, and they are the most difficult to resolve with therapy. Intraorally, superficial “ragged” erosions and ulcerations are distributed haphazardly on the oral mucosa. The disease may affect any oral mucosal location but is most commonly found on the palate, labial and buccal mucosa, ventral surface of the tongue, and gingivae (Figure 47-1). Almost half of affected individuals have oral mucosal lesions before the onset of cutaneous lesions, sometimes by as much as a year or more. Eventually, however, nearly all affected persons have intraoral involvement.1

Figure 47-1 A-C, Examples of oral lesions in pemphigus vulgaris.

(A, From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders. B, Courtesy Dr. Fariba Younai. C, Courtesy Dr. Sidney Eisig.)

Extraorally, skin lesions appear as flaccid vesicles (“without tone”) and bullae (blisters) that rupture quickly (usually within hours to a few days), leaving an erythematous, denuded surface. A characteristic feature of this disease is the induction of a bulla on otherwise normal-appearing skin if firm lateral pressure is exerted. This is known as a positive Nikolsky sign. Without proper treatment and control, both oral and skin lesions tend to persist and progressively involve more surface area.

Treatment and Prognosis

Medical diagnosis should be made as early as possible because control is generally easier to achieve at that time. Treatment consists primarily of systemic corticosteroids (usually prednisone), often in combination with other immunosuppressive drugs, such as azathioprine, a steroid-sparing agent, and methotrexate, an antimetabolism drug.2 Side effects with long-term use of systemic corticosteroids are significant and include diabetes mellitus, adrenal suppression, weight gain, osteoporosis, peptic ulcers, severe mood swings, and increased susceptibility to infections. Pemphigus rarely undergoes complete resolution, although remissions and exacerbations are common.

CICATRICIAL PEMPHIGOID

Cicatricial pemphigoid (also called benign mucous membrane pemphigoid and mucous membrane pemphigoid) is a benign chronic blistering autoimmune disease that affects the oral mucosa, conjunctiva of the eye, genital mucosa, and skin. It is characterized by healing of lesions with scarring. In this disease, tissue-bound autoantibodies are directed against one or more components of the basement membrane.”1 Lesions occur as a result of separation of the epithelium from the underlying connective tissue. The precise incidence of the disease is not known, but most authors believe that it is at least twice as common as pemphigus vulgaris.1 The term pemphigoid is used in naming this disease because clinically it appears similar to pemphigus. Prognosis and microscopic features of pemphigoid, however, are very different from those of pemphigus. Cicatricial is derived from the word cicatrix, meaning “scar.”

Clinical Features

Cicatricial pemphigoid usually affects older adults; the average age of onset is 60 years. Females are more frequently affected than males (ratio of 2:1). Oral lesions are most common, but other sites may be involved, including conjunctival, nasal, esophageal, laryngeal, and vaginal mucosa, as well as the skin.

Oral lesions begin as either vesicles or bullae that may occasionally be evident clinically. Eventually the oral blisters rupture, leaving large areas of superficial, ulcerated, and denuded mucosa. The most common site for lesions is the gingiva (Figure 47-2). The lesions are usually painful and persist for weeks to months if left untreated. They are often seen diffusely throughout the mouth but may be limited to certain areas, namely the gingiva. Gingival involvement is usually termed desquamative gingivitis. This clinical reaction pattern may also be seen in other conditions, such as erosive lichen planus or, much less frequently, pemphigus vulgaris.1

The most significant complication of cicatricial pemphigoid is ocular involvement. This occurs in approximately 25% of persons with oral involvement. One eye may be affected before the other. The earliest ocular change is subconjunctival fibrosis. As the disease progresses, the conjunctiva becomes inflamed and eroded. Scarring (during the healing process) occurs between the lining of the globe of the eye and the lining of the inner surface of the eyelid; adhesions result. Without treatment the inflammatory changes become more severe. Eyelids may turn inward from severe scarring. Eyelashes may then rub against the cornea and globe of the eye. Scarring may close the openings of the lacrimal glands, resulting in loss of tears and extremely dry eyes. The cornea then produces keratin as a protective mechanism, but this is detrimental because keratin is an opaque material, and blindness soon results. In end-stage ocular involvement, adhesions may occur between the upper and lower eyelids.1

Other mucosal sites may be involved. In female patients, vaginal mucosal lesions may be considerably painful. Although fairly uncommon, laryngeal lesions may be serious because of the possibility of airway obstruction by the bullae that form. Patients who experience “a sudden change in vocalization or who have difficulty breathing” should receive an examination with laryngoscopy.1

Treatment and Prognosis

If only oral lesions exist, the disease may be controlled with application of one of the more potent topical corticosteroids to the lesions several times each day. Once the condition is controlled, the applications may cease; however, lesions are certain to return. Sometimes alternate-day application minimizes disease activity.1

Clients with only gingival lesions should practice good oral hygiene measures to help decrease severity of the lesions and reduce the amount of topical medication required. Sometimes a flexible mouthguard (used as a medication carrier) may aid in treating gingival lesions.

If topical corticosteroids are unsuccessful, systemic corticosteroids plus other immunosuppressive agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide) are used if the individual has no medical contraindications. Aggressive treatment of this nature is a necessity when ocular involvement is severe. Surgical correction of ocular lesions must take place when the disease is under control. Occasionally an alternative therapy, dapsone, is used, which may produce fewer serious side effects. Dapsone is a sulfa drug derivative, so it is contraindicated for use in those with allergy to sulfa drugs.1

ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME

Erythema multiforme (EM) is a blistering, ulcerative disease that affects the skin and mucous membranes. The condition is of uncertain cause, but some evidence supports that it is a hypersensitivity reaction.1

Clinical Features

With EM there is acute onset, but the disease may manifest with a wide spectrum of clinical features. At the mild end of the spectrum, ulcerations develop that primarily affect the oral mucosa. In the severe form of EM, diffuse sloughing and ulceration of the entire skin and mucosal surfaces may be seen. The severe form is known as toxic epidermal necrolysis or Lyell’s disease. Patients are usually first diagnosed in their 20s and 30s; men are affected more often than women.

EM has a prodromal period, with individuals experiencing fever, malaise, headache, cough, and sore throat 1 week before onset of characteristic clinical symptoms. The disease is self-limiting, usually lasting 2 to 6 weeks; however, 20% of those affected experience recurrent episodes, usually in the spring and autumn.

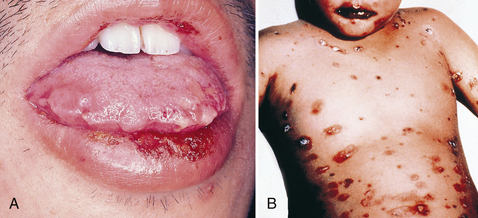

Erythematous skin lesions occur in 50% of cases. A variety of appearances of these lesions may be present (multiforme means “many forms”). Early lesions are flat, round, and dusky-red and appear on the extremities. The lesions may become slightly elevated and may evolve into bullae with necrotic centers. Occasionally, concentric circular erythematous lesions resembling a target or bull’s eye (target lesions) develop that are highly characteristic of the disease (Figure 47-3).

Figure 47-3 Target lesions of erythema multiforme.

(Courtesy Dr. Donald M. Cohen and Dr. Indraneel Bhattacharyya.)

Intraorally, erythematous patches undergo epithelial necrosis and become large, shallow erosions and ulcerations with irregular borders. The lesions emerge quickly and are very uncomfortable. There is a diffuse distribution, but the most common areas affected are the lips, labial mucosa, buccal mucosa, tongue, floor of the mouth, and soft palate. Hemorrhagic, crusted lips are also common (Figure 47-4, A). The gingivae and hard palate are seldom affected.1

Figure 47-4 Oral lesions of erythema multiforme. A, Crusted lip lesions with edema, ulceration, and erythema. B, Stevens-Johnson syndrome of erythema multiforme.

(From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

A severe form of EM, known as erythema multiforme major or Stevens-Johnson syndrome, is usually triggered by a drug reaction rather than an infection (see Figure 47-4, B). Ocular, genital, oral, and skin lesions are present. There are approximately five cases per million persons every year.

The most severe form of EM, toxic epidermal necrolysis, is almost always triggered by drug exposure. The disease causes diffuse sloughing of a significant portion of the skin and mucosal surfaces, similar to a bad scalding. Although fairly rare, this form tends to occur in older people and is more common in females. If a patient survives, the cutaneous lesions resolve in 2 to 4 weeks, but oral lesions may take longer to heal. Half of patients affected have significant ocular damage. There is approximately one case per million people annually.

Treatment and Prognosis

EM can be managed with systemic corticosteroids. Minor forms of the disease may be managed effectively with topical corticosteroid syrups or elixirs. Topical anesthetic agents are effective in decreasing oral discomfort. With more severe forms of the disease, intravenous rehydration may be necessary. EM is not life-threatening except in its most severe forms. Mortality rates with toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are 34% and 2% to 10%, respectively.1

HASHIMOTO’S THYROIDITIS

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, a form of hypothyroidism characterized by decreased levels of thyroid hormone, is caused in adults by autoimmune destruction of the thyroid gland or by iatrogenic factors (induced by the treatment itself), such as radioactive iodine therapy or surgery for the treatment of hyperthyroidism.1

Thyroid hormone is necessary for normal cellular metabolism. Therefore many clinical signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism can be related to the decreased metabolic rate in these patients. The most common signs and symptoms include those listed in Table 47-1.

Treatment for hypothyroidism usually consists of thyroid replacement therapy, most commonly with levothyroxine, and the prognosis is generally good for adults. If recognized early in children, the prognosis is also good; if not identified early, permanent damage to the central nervous system may occur, resulting in intellectual and developmental disability (formerly known as mental retardation). Fortunately, in children thyroid replacement therapy often results in a dramatic resolution of the condition.1

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by a nonsuppurative inflammatory destruction of the joints, is of unknown cause in most cases. It affects 3% of the U.S. population, and 200,000 new cases are diagnosed yearly. The disease begins as an attack against the synovial membrane (synovitis). Subsequently, enzymes such as collagenases and other proteases destroy the cartilage and underlying bone. Attempted remodeling by the exposed bone results in a characteristic deformation of the joint.2

Clinical Features

RA affects women three times more frequently than men; however, men are diagnosed at a somewhat younger age than women (25 to 35 versus 35 to 45 years). Onset and course of the disease are extremely variable, regardless of gender. For many people, no more than one or two joints are involved and significant pain or limitation of joint motion may never develop. In others, the disease rapidly progresses to debilitating polyarthralgia (pain in several joints).2

Signs and symptoms tend to become more severe over time. Symptoms are listed in Table 47-1. Bilateral involvement of the small joints of the hands and feet is almost always present, but it is not unusual for knees and elbows to be affected. The hip joint is least affected by RA. Approximately 25% of patients also have firm, partially movable, nontender rheumatoid nodules beneath the skin near the affected joint. The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) eventually becomes involved in 75% of cases, although this is usually clinically insignificant. Radiographically, involved TMJs demonstrate a flattened condylar head with irregular surface features, an irregular temporal fossa surface, and anterior displacement of the condyle.1

Treatment and Prognosis

There is no cure for RA. Current treatment strives to only suppress the disease process as much as possible. With early and mild cases of RA, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are prescribed, with occasional corticosteroid injections into the joint as needed. Injections are used sparingly because they have been associated with additional degenerative changes and fibrous ankylosis. Second-line medications include systemic corticosteroids, immunosuppressant drugs such as methotrexate, and biologic agents such as etanercept (Enbrel). Corticosteroids impede the body’s ability to make substances that cause inflammation, such as prostaglandins. Methotrexate blocks the division of cells that are responsible for some of the pain, inflammation, and damage caused by RA. Biologic agents such as etanercept interfere with the development or action of cytokines, substances that lead to inflammation and joint degeneration. The drugs are intended to go beyond symptom relief to actually stop joint damage and inflammation. Iron supplementation may also be necessary because some patients may have mild anemia, discovered during blood work to detect levels of rheumatoid factor (RF), which is used in diagnosis.1,2 Extended use of corticosteroids may warrant antibiotic prophylaxis before dental hygiene care.

SARCOIDOSIS

Sarcoidosis, a multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown cause, is more commonly recognized in the developed world. In North America, blacks are affected 10 times more frequently than whites. Females are affected slightly more frequently than males, with age at onset between 20 and 40 years. The disorder manifests acutely over a period of days to weeks, and the symptoms are variable.

Approximately 20% of individuals have no symptoms, and the disease is discovered on routine chest radiographs. When present, common clinical symptoms include dyspnea, dry cough, chest pain, fever, malaise, fatigue, arthralgia, and weight loss. Pulmonary symptoms are most common.1,3

Although any organ may be affected, the most common sites are the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, eyes, and salivary glands. Lymphoid tissue is almost always involved. Twenty-five percent of persons experience granulomatous inflammation of the skin, which can best be described as chronic, violaceous (of violet color), indurated lesions often on the nose, ears, lips, and face (Figure 47-5). Bilateral, elevated, indurated, purplish plaques also are seen commonly on the limbs, back, and buttocks. Frequently, scattered, nonspecific, tender, erythematous nodules occur on the lower legs. In 25% of cases, ocular involvement affects the lacrimal glands, causing dry eyes.1,3

Figure 47-5 Indurated lip lesions characteristic of sarcoidosis.

(Courtesy Dr. Donald M. Cohen and Dr. Indraneel Bhattacharyya.)

Salivary glands may be affected, resulting in clinical enlargement and xerostomia. Any major or minor salivary gland may be involved, and sometimes it is necessary to remove intraoral mucoceles that occur. It is important to note that salivary gland enlargement, xerostomia, and dry eyes can combine to mimic Sjögren’s syndrome. If salivary gland and lymph node involvement are excluded, clinically evident oral manifestations in sarcoidosis are uncommon.

Any oral mucosal site may manifest lesions such as a submucosal mass, an isolated papule, or an area of granularity. These may be normal in color, brownish-red, violaceous, or hyperkeratotic. Bony involvement is rare, but when present may mimic periodontal disease.1

SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS (SCLERODERMA)

Systemic sclerosis or scleroderma (also referred to as hide-bound disease) is a relatively rare condition that probably has an immune-mediated component. For unknown reasons, dense collagen is deposited in the body tissues in extraordinary amounts. The most dramatic effects are seen in the skin; however, the disease is often serious because most organs of the body can be affected.1

Clinical and Radiographic Features

Scleroderma affects approximately 19 persons per million population each year, affecting women three times more frequently than men. Most patients are adults. Cutaneous (relating to the skin) changes are the first symptoms to manifest, often bringing the condition to the person’s attention.

One of the first signs of the disease is often Raynaud’s phenomenon, a vasoconstrictive condition often triggered by emotional distress or exposure to cold. Resorption of the terminal phalanges and flexion contractures results in clawlike fingers (Figure 47-6). Vasoconstriction and abnormal collagen deposition sometimes lead to ulcerations on the fingertips. As a result of these phenomena, the skin develops a diffuse, hard texture (sclero meaning “hard”; derma meaning “skin”). The surface of the skin is also usually smooth. Facially, smooth, taut skin results in a masklike appearance. Sometimes the alae of the nose become “pinched-in.”1

Involvement of other organs may be insidious, but the results are more serious. Organ fibrosis may include the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract, leading to organ failure. Pulmonary fibrosis is a primary cause of death for affected individuals.1

The oral cavity is affected to varying degrees. Microstomia (smallness of the oral aperture, or opening) often develops as a result of collagen deposition in perioral tissues. In 70% of persons affected, a tight, pursestring appearance of the lips causes a limitation in mouth opening. Intraorally, loss of attached gingival mucosa and generalized recession may occur. Difficulty in swallowing from deposition of collagen in the mucosa of the lingual and esophageal areas is further hindered by a firm, hypomobile tongue and an inelastic esophagus.1

Radiographically, generalized widening of the periodontal ligament space may be subtly apparent or dramatic (Figure 47-7). In 20% of patients there are varying degrees of resorption of the posterior ramus of the mandible, the coronoid process, and the condyle.1

A mild form of this condition known as localized scleroderma usually affects only a small patch of skin. The lesions often look like scars, hence the name coup de sabre, or “strike of the sword” (Figure 47-8). This is primarily a cosmetic condition and is rarely life-threatening.

Treatment and Prognosis

The management of scleroderma is difficult. d-Penicillamine or other systemic medications may be prescribed in an effort to inhibit collagen production. Unfortunately, corticosteroids have proven to be of little benefit.

Other treatments are aimed at controlling symptoms. Esophageal dilation is often performed to correct the dysphagia. Nifedipine (Procardia) helps increase peripheral blood flow and decrease symptoms of Raynaud’s phenomenon1; it can also cause drug-influenced gingival enlargement.

Affected persons who wear removable prostheses may develop problems because of the microstomia and inelasticity of the mouth. Patients may also have problems performing adequate oral hygiene owing to decreased ability to handle a toothbrush because of sclerosis of the fingers and hands. In some cases resorption of the mandible may become so severe that a fracture results.1

Although the overall prognosis is poor, it is better for patients with limited cutaneous involvement than for those with systemic involvement. Approximately 80% of patients survive 2 years after diagnosis, but the survival rate drops with time. Fifty percent survive 8 years; the survival rate drops to 30% at 12 years.1

SJÖGREN’S SYNDROME

Sjögren’s syndrome, a chronic, systemic autoimmune disorder that principally involves the salivary and lacrimal glands, results in xerostomia and xerophthalmia (dry eyes). In primary Sjögren’s syndrome, a patient presents with xerostomia and xerophthalmia, but no other autoimmune disorder is present; in secondary Sjögren’s syndrome a patient presents with the aforementioned symptoms in addition to another associated autoimmune disease.

Although the cause of Sjögren’s syndrome is unknown, there is evidence of a genetic influence. Relatives of affected individuals have an increased frequency of other autoimmune diseases. Furthermore, there is speculative evidence that viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus, play a role in disease onset.1

Clinical Features

Although Sjögren’s syndrome is not a rare condition, the exact prevalence is unknown. It has been estimated to occur in 0.5% of the U.S. population. Eighty percent to 90% of cases occur in middle-aged women, and the condition rarely occurs in children.

The most common associated disorder is RA. Fifteen percent of patients with RA have Sjögren’s syndrome. Secondary Sjögren’s syndrome may also develop in 30% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.1,4

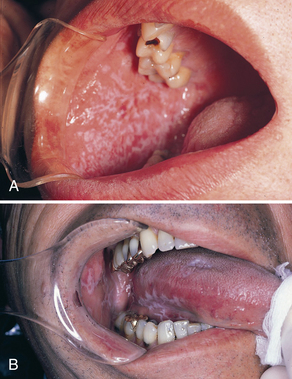

Patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and its associated xerostomia may complain of difficulty swallowing, altered taste, or difficulty wearing dentures. Fissured tongue and atrophy of papillae are common (Figure 47-9). Along with xerostomia, the oral mucosa may be red and tender, usually because of secondary candidiasis. Denture sores and angular cheilitis are also common. Furthermore, lack of salivary cleansing action places individuals at extreme caries risk, especially for cervical caries1 (see Chapter 16).

Figure 47-9 Sjögren’s syndrome. This individual had severe xerostomia. The filiform papillae are lacking.

(From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

One third to one half of patients have diffuse, firm enlargement of the major salivary glands during the course of their disease (Figure 47-10). The swelling is usually bilateral, may be nonpainful or slightly tender, and may be intermittent or persistent. Usually, the greater the severity of disease, the greater the likelihood of salivary gland enlargement. Furthermore, reduced salivary flow places persons with Sjögren’s syndrome at an increased risk for retrograde bacterial sialadenitis.1

Figure 47-10 Enlargement of parotid gland in Sjögren’s syndrome.

(Courtesy Dr. Donald M. Cohen and Dr. Indraneel Bhattacharyya.)

The eyes may be affected as well. Patients often complain of a scratchy, gritty sensation or the perceived presence of a foreign body in the eye. Vision may become blurred, and sometimes there is an aching pain. Ocular problems are least severe in the morning on wakening and become more pronounced as the day progresses.1

Other body tissues are affected by the inflammatory process. The skin and the nasal and vaginal mucosae may also become dry. General malaise or fatigue is also fairly common, and depression sometimes occurs. Other possible associated problems include lymphadenopathy, primary biliary cirrhosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, interstitial nephritis, interstitial lung fibrosis, vasculitis, and peripheral neuropathies.

Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment is mostly supportive in nature. Dry eyes are best managed by occasional use of artificial tears. Artificial saliva, oral lubricants, moisturizing mouth rinses, xylitol gum, and xylitol candy are available for xerostomia. Sialagogues, for example pilocarpine, can be helpful to stimulate salivary flow if enough functional salivary tissue still remains. Because of an increased risk of dental caries, daily fluoride applications and brushing with casein phosphopeptide- amorphous calcium and phosphate products (e.g., MI Paste) are indicated in dentulous clients (see Chapter 31). Antifungal therapy may be needed to treat secondary candidiasis. Individuals with Sjögren’s syndrome have up to a 40 times higher rate of lymphomas (predominantly non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphomas) than the normal population. Close follow-up is necessary with the client’s physician of record if symptoms persist or if the condition appears to worsen.1

LICHEN PLANUS

Lichen planus is a “relatively common, chronic dermatologic disease that often affects the oral mucosa.” The name of the disease comes from the words for primitive plants composed of algae and fungi (lichens) and the term planus, which is Latin for “flat.” Although the name suggests a flat, fungal condition, current evidence indicates that it is an immunologically mediated mucocutaneous disorder.1

A variety of medications may induce lesions that are clinically identical to lichen planus (lichenoid drug reactions), but the terms lichenoid mucositis (mucosal involvement) and lichenoid dermatitis (skin involvement) are names for lesions that are drug-related.1

Clinical Features

Most patients with lichen planus are middle-aged adults. Children are rarely affected. Women are affected more often than men, usually by a ratio of 3:2. About 1% of the population experiences cutaneous lichen planus. The prevalence of oral lichen planus is between 0.1% and 2.2%.1

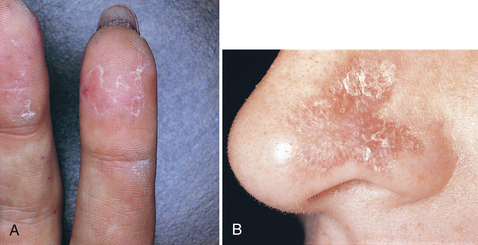

Skin lesions are purple papules (circumscribed solid elevations) (Figure 47-11). They usually affect the flexor surfaces of the extremities. The lesions itch, but scratching them is very painful. The surface of the papules exhibits “a fine, lacelike network of white lines” (Wickham’s striae). Other extraoral sites that may be involved include the glans penis, the vulvar mucosa, and the nails.1

Reticular Oral Lichen Planus

Reticular lichen planus is much more common than the erosive form. The reticular form usually does not cause symptoms and involves the posterior buccal mucosa bilaterally. Other sites may include the lateral and dorsal surfaces of the tongue, the gingivae, and the palate.

Reticular lichen planus gets its name from the characteristic white interlacing lines of the lesions (Figure 47-12). These white lesions sometimes appear as papules. The lesions are not usually static and may come and go over a period of weeks or months. Also, the reticular pattern may not be as evident in some sites as in others (e.g., dorsal tongue lesions may appear as “keratotic plaques with atrophy of the papillae”).1

Erosive Oral Lichen Planus

Erosive lichen planus, even though not as common as the reticular form, is more significant because the lesions—erythematous areas with central ulceration—are usually symptomatic. The edge of the lesions exhibit the fine, white, radiating striae characteristic of the disease (Figure 47-13). When the ulcerations are limited to the gingival mucosa, this is termed desquamative gingivitis (Figure 47-14). When ulcerations are confined to the gingiva, biopsy is indicated to rule out cicatricial pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris because they may appear similarly in gingival areas.1

Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment for reticular lichen planus is usually not needed because there are no symptoms. Occasionally patients may have a concurrent candidiasis infection for which antifungal therapy is prescribed. Erosive lichen planus, however, requires treatment for the open sores in the mouth. Corticosteroids are often prescribed. A topical corticosteroid (e.g., fluocinonide gel) may be applied several times each day to the most severe lesions to induce healing. Follow-up every 3 months is recommended because there is the potential for malignant transformation.

LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Lupus erythematosus is a classic example of an immunologically mediated condition. There are several forms: systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus.1,4

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a serious multisystem disease with a variety of cutaneous and oral manifestations. Although the precise cause is unknown, genetic factors probably play a role. Difficult to diagnose in its early stages, SLE often manifests in a nonspecific, vague fashion, with periods of remission or disease inactivity. Women are affected 8 to 10 times more frequently than men. The average age at diagnosis is 31 years.1,4

Clinical Features

Common systemic symptoms include fever, weight loss, arthritis, and malaise. In 40% to 50% of affected persons there is a characteristic “butterfly rash” (Figure 47-15), which develops over the malar area and the nose (sunlight often makes the rash worse), and the kidneys are affected. Typically, the most significant aspect of the disease is kidney failure. At autopsy, nearly 50% of persons display warty vegetations affecting the heart valves. The significance is debatable; however, some may develop a superimposed subacute bacterial endocarditis.1,4

Figure 47-15 Malar rash seen in systemic lupus erythematosus.

(Courtesy Dr. Donald M. Cohen and Dr. Indraneel Bhattacharyya.)

Oral lesions develop in 5% to 40% of these patients. Lesions usually affect the palate, buccal mucosa, tongue, and gingivae. Sometimes they appear as lichenoid areas or look nonspecific or somewhat granulomatous. Varying degrees of ulceration, pain, erythema, and hyperkeratosis may be present.

Criteria for making an SLE diagnosis have been established by the American Rheumatism Association and include both clinical and laboratory findings (see Table 47-1).1,4

Chronic Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) primarily affects the skin and oral mucosa and has a good prognosis. Patients usually have few or no systemic signs or symptoms. Skin lesions that erupt are known as discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 47-16). They begin as scaly, erythematous patches that are frequently distributed on sun-exposed skin, especially in the head and neck area. The healing process usually results in cutaneous atrophy with scarring and hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation of the resolving lesion.

Figure 47-16 Two examples of skin lesions in lupus erythematosus.

(A, From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders. B, Courtesy Dr. Edward V. Zegarelli.)

Intraorally, the lesions appear practically identical to the lesions of erosive lichen planus; however, the lesions of CCLE rarely occur in the absence of skin lesions. The ulcerative and atrophic oral lesions may be painful, especially when exposed to acidic or salty foods.1,4

Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) has clinical features intermediate between those of SLE and CCLE. Skin lesions are the most prominent feature of this variation. Most affected individuals have photosensitivity, accompanying arthritis, and musculoskeletal problems.1,4

Treatment and Prognosis

For all forms of lupus erythematosus, the client must avoid excessive sunlight exposure because ultraviolet light may precipitate disease activity. With acute episodes of disease, systemic corticosteroids are generally indicated, sometimes supplemented with other immunosuppressive agents. Antimalarial drugs may be effective, usually more so for the CCLE or SCLE types. If oral lesions are present, they typically respond to the systemic therapy.4

Prognosis for the patient with SLE varies. For patients in treatment the 5-year survival rate is approximately 95%. By the 15-year mark, survival rate falls to 75%.1,4 Prognosis depends on which organs are affected and how frequently the disease is reactivated. The most common cause of death is renal failure caused by kidney involvement. For reasons that are poorly understood, the prognosis is worse for men than for women. Furthermore, for patients with CCLE, prognosis is considerably better than that for those with SLE. Transformation to SLE may be seen in approximately 5% of CCLE patients. About 50% of CCLE cases resolve after several years.1

DENTAL HYGIENE PROCESS OF CARE

Assessment

During the assessment phase, it is of utmost importance to obtain a thorough health and dental history from the client. If there are indications that the client is not well or that immediate referral to a physician is needed, the dental hygienist informs the dentist and postpones dental hygiene care until a time approved by the dentist and physician of record. If pain is reported by the client during the assessment phase, the first course of action would be referral to the physician for pain management.

Diagnosis

Human needs assessments will differ depending on the client’s autoimmune disease(s). The dental hygiene diagnosis is highly dependent on the signs observed by the clinician and the symptoms reported by the client at the assessment phase.

Planning

The planning phase may be complicated by medical attention needed by the client at the time of dental hygiene care. Consultation with the client’s physician to establish goals and communication is helpful in determining how to coordinate dental hygiene care with concurrent medical care. An example of a goal might be: “Client will report a decrease in oral discomfort at next appointment.”

Implementation

The implementation phase of the dental hygiene process includes client education, periodontal debridement, tissue evaluation, and referral back to the physician if warranted. Depending on the severity of oral symptoms, clients may need specialized care such as from an oral pathologist or periodontist. Client education must include disease pathophysiology, effects on the oral cavity, palliative treatments for oral discomfort, and preventive oral therapies where appropriate (Box 47-1).

Evaluation

Clients with autoimmune disease must be placed on 2- to 3-month maintenance intervals because of their compromised immune system. Furthermore, it is important that after initial therapy is completed, an evaluation appointment be scheduled to assess the client’s host response to dental hygiene care and to reinforce self-care.

At each subsequent appointment, the client’s overall health, as well as oral health, is reassessed. Continued communication between the dental hygienist, dentist, and physician is extremely important when changes are made in planned professional care.

The dental hygienist relates the client’s human needs to the factors that are contributing to the problem(s). The diagnostic statements and goals are used to guide clinical decisions regarding appropriate dental hygiene interventions so that oral health can be achieved. Whether signs and symptoms first documented are still evident at the evaluation appointment will determine if the goals were met, partially met, or not met. Further treatment and referral may be necessary, depending on outcomes.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Explain that daily self-care and 2- to 3-month maintenance care are necessary to control and/or prevent autoimmune disease oral manifestations.

Explain that daily self-care and 2- to 3-month maintenance care are necessary to control and/or prevent autoimmune disease oral manifestations.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

The dental hygienist thoroughly updates the client’s health, dental, and pharmacologic histories and documents any updates or changes in health status at each visit.

The dental hygienist thoroughly updates the client’s health, dental, and pharmacologic histories and documents any updates or changes in health status at each visit.KEY CONCEPTS

The incidence of encountering individuals with autoimmune diseases in the oral care environment will increase as the percentage of aging persons increases.

The incidence of encountering individuals with autoimmune diseases in the oral care environment will increase as the percentage of aging persons increases. The dental hygienist screens for and recognizes typical signs, symptoms, and manifestations of autoimmune diseases.

The dental hygienist screens for and recognizes typical signs, symptoms, and manifestations of autoimmune diseases. Some autoimmune diseases affect the head and neck area only, whereas others can affect almost any organ system of the body.

Some autoimmune diseases affect the head and neck area only, whereas others can affect almost any organ system of the body. Autoimmune diseases compromise clients’ immune systems and put them at risk for periodontal disease.

Autoimmune diseases compromise clients’ immune systems and put them at risk for periodontal disease. Some autoimmune diseases warrant antibiotic prophylaxis before any invasive care is begun. Consultation with the physician is indicated.

Some autoimmune diseases warrant antibiotic prophylaxis before any invasive care is begun. Consultation with the physician is indicated. Scleroderma and rheumatoid arthritis may affect a client’s ability to perform adequate oral self-care measures.

Scleroderma and rheumatoid arthritis may affect a client’s ability to perform adequate oral self-care measures. Chronic xerostomia places an individual at extreme risk for dental caries. Professional and daily self-applied topical fluoride applications, use of calcium and phosphate products and antibacterials (e.g., xylitol mints and gum), and salivary substitutes may help manage xerostomia and caries risk in those with Sjögren’s syndrome and others with chronic dry mouth (see Chapters 16 and 31).

Chronic xerostomia places an individual at extreme risk for dental caries. Professional and daily self-applied topical fluoride applications, use of calcium and phosphate products and antibacterials (e.g., xylitol mints and gum), and salivary substitutes may help manage xerostomia and caries risk in those with Sjögren’s syndrome and others with chronic dry mouth (see Chapters 16 and 31).CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Profile: Mrs. M., age 40, who has not been to a dentist for 3 years, was scheduled for care with the dental hygienist.

Chief Complaint: “I have a very dry mouth. Also I cannot eat spicy foods because they irritate the skin inside my mouth. I haven’t been able to really taste my food for some time.”

Health History: Besides the slight discomfort from her inflamed tissues, she believes her health is satisfactory.

Social History: Married with two children.

Dental History: Intraorally, her probing depths range from 4 to 6 mm, with generalized, moderate-to-severe bleeding on probing. The gingivae and oral mucosa are moderately inflamed and erythematous. The tissues are smooth without stippling, and the tongue is fissured with atrophic papillae. She has Class II periodontitis, with generalized, moderate calculus deposits and heavy cervical bacterial plaque biofilm. Six Class V carious lesions were identified.

Oral Health Behavior Assessment: She brushes her teeth two times per day, but admits that she does not floss.

Supplemental Notes: There is obvious facial swelling bilaterally in the area of the parotid glands; however, she does not report any injury to the head and neck.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge Michelle L. Sensat for her past contributions to this chapter.

1. Ibsen O.A.C., Phelan J.A. Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5. St Louis: Saunders; 2009.

2. Hunder G. Mayo Clinic on arthritis: conquering the pain and leading an active life, ed 2. Rochester, Minn: Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research; 2002.

3. Moller D.R. Etiology of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 1997;18:4.

4. Hughes C.T., Downey M.C., Winkley G.P. Systemic lupus erythematosus: a review for dental professionals. J Dent Hyg. 1998;72:2.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..