CHAPTER 49 Respiratory Diseases

Respiratory diseases are common among the general population and can compromise dental and dental hygiene care. To properly manage this group of clients, it is important for the dental hygienist to understand respiratory diseases, medications used in their treatment, their link with periodontal health and oral hygiene, and their implications for dental hygiene care.

The most frequently encountered respiratory diseases are asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), including emphysema and chronic bronchitis. In addition, tuberculosis, a disease that has affected mankind for centuries, continues to be a worldwide problem. The emergence of multi–drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis poses yet another infection control and treatment challenge to healthcare providers.1

RESPIRATORY DISEASES

Asthma

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory respiratory disease characterized by an increased responsiveness of the bronchial airways to various stimuli. Management of the asthma client is dependent on assessment of the individual’s severity level, degree of control and responsiveness to treatment. Asthma severity is classified as intermittent or persistent (mild, moderate, or severe) based on current impairment of quality of life and risk for future exacerbations and/or lung damage. These classifications are determined by clinical tests as well as the occurrence of airflow obstruction symptoms in relation to environmental factors, exercise, and nighttime sleep disturbances.2

Etiology

Various substances or environmental factors can precipitate an asthmatic attack, including specific antigens such as pollen, ragweed, molds, foods, cockroaches, and house dust mites. Chemical irritants such as tobacco smoke, scents, and house sprays may trigger an asthmatic attack. Exposure by dental personnel to methacrylates found in dental restorative and sealant materials also has been cited as a possible link with occupational asthma.3 Other nonallergic stimulators—respiratory infections, environmental pollutants and irritants, exercise, cold air, and emotional stress—also can cause an attack. Generalized narrowing of bronchi and bronchioles caused by mucosal inflammation, increased secretions, and smooth muscle contraction produce asthmatic symptoms.4,5

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical manifestations of asthma include periodic wheezing, dyspnea (difficulty in breathing), coughing, and chest tightness. These and other signs and symptoms are listed in Box 49-1. The onset of an asthmatic attack usually begins with mild wheezing and coughing, progressing to increased difficulty in breathing. As the attack develops, the individual may experience a sense of pressure or tightness in the chest and a feeling of suffocation. A severe asthmatic attack that does not respond to treatment with an adequate dose of commonly used bronchodilators is referred to as status asthmaticus. This condition may produce bronchospasms for hours or days without remission and often requires hospitalization.

Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

To prevent an acute asthmatic attack and to address the unique needs of the asthmatic client, the dental hygienist should do the following:

Assess the frequency, conditions and time of onset, and type—intermittent or persistent (mild, moderate, or severe)—of asthmatic attacks experienced; their management, including the type of medication used and precipitating factors; and whether an attack has warranted emergency treatment.4

Assess the frequency, conditions and time of onset, and type—intermittent or persistent (mild, moderate, or severe)—of asthmatic attacks experienced; their management, including the type of medication used and precipitating factors; and whether an attack has warranted emergency treatment.4 Seek a medical consultation in cases of persistent moderate to severe asthma or when reported symptoms suggest poorly controlled asthma. Document if the client is taking systemic corticosteroids, such as prednisone, for chronic asthma. The physician may want to increase the regular dose of prednisone to prevent an adrenal crisis during a particularly stressful dental appointment.4

Seek a medical consultation in cases of persistent moderate to severe asthma or when reported symptoms suggest poorly controlled asthma. Document if the client is taking systemic corticosteroids, such as prednisone, for chronic asthma. The physician may want to increase the regular dose of prednisone to prevent an adrenal crisis during a particularly stressful dental appointment.4 Note the precipitating factors reported by the client, and avoid these factors during professional care.

Note the precipitating factors reported by the client, and avoid these factors during professional care. Instruct clients to bring the medical inhalers prescribed by the physician to every appointment, for use in case of an acute attack or prophylactically when chronic moderate to severe disease is present.

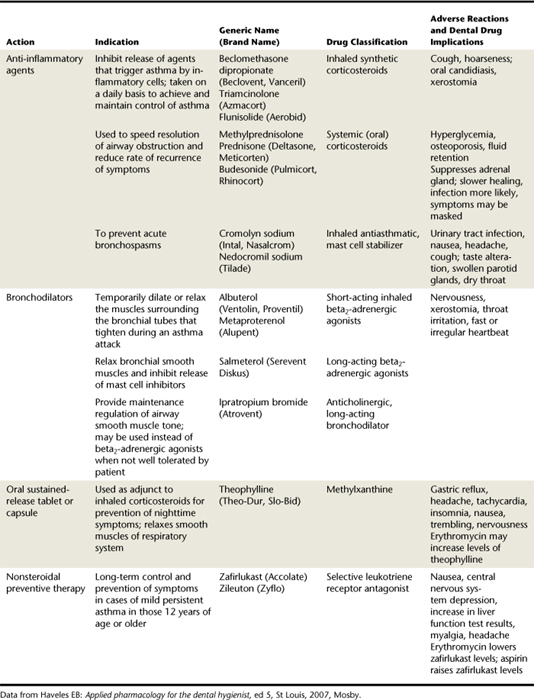

Instruct clients to bring the medical inhalers prescribed by the physician to every appointment, for use in case of an acute attack or prophylactically when chronic moderate to severe disease is present. Note that some medications used by asthmatics cause xerostomia (dry mouth) and unpleasant taste sensation after inhalation use. Consequently the asthmatic client may be more prone to dental caries and gingivitis. Children in particular may increase their sucrose intake to combat the unpleasant taste from the inhalant. Table 49-1 describes drugs commonly used in the treatment of asthma.

Note that some medications used by asthmatics cause xerostomia (dry mouth) and unpleasant taste sensation after inhalation use. Consequently the asthmatic client may be more prone to dental caries and gingivitis. Children in particular may increase their sucrose intake to combat the unpleasant taste from the inhalant. Table 49-1 describes drugs commonly used in the treatment of asthma. Instruct the client to avoid drugs listed in Table 49-2, such as aspirin-containing medications, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, barbiturates, and narcotics, because they can precipitate an attack.

Instruct the client to avoid drugs listed in Table 49-2, such as aspirin-containing medications, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, barbiturates, and narcotics, because they can precipitate an attack. Use a local anesthetic agent without epinephrine or levonordefrin because some asthmatics are sensitive to the sulfite preservatives present in these anesthetic solutions.4

Use a local anesthetic agent without epinephrine or levonordefrin because some asthmatics are sensitive to the sulfite preservatives present in these anesthetic solutions.4 Make the oral care environment as stress-free as possible because anxiety can induce an asthmatic attack in many people, particularly children (see Chapter 37).

Make the oral care environment as stress-free as possible because anxiety can induce an asthmatic attack in many people, particularly children (see Chapter 37). Use nitrous oxide–oxygen analgesia and/or small doses of diazepam, as prescribed by the dentist, to reduce stress if indicated4 (see Chapter 40).

Use nitrous oxide–oxygen analgesia and/or small doses of diazepam, as prescribed by the dentist, to reduce stress if indicated4 (see Chapter 40). Convey a calm, caring, and compassionate attitude to relax the client and to reduce stress-induced asthmatic attacks.

Convey a calm, caring, and compassionate attitude to relax the client and to reduce stress-induced asthmatic attacks. Evaluate children carefully for malocclusion; many asthmatic children are mouth breathers, and a correlation has been observed between higher palatal vaults, greater overjets, posterior crossbite incidence, and mouth breathing in children.6

Evaluate children carefully for malocclusion; many asthmatic children are mouth breathers, and a correlation has been observed between higher palatal vaults, greater overjets, posterior crossbite incidence, and mouth breathing in children.6 Observe any asthmatic symptoms during and after dental procedures, because decreased lung function can be triggered by anxiety, supine positioning, tooth enamel dust, and aerosols commonly created by dental procedures.

Observe any asthmatic symptoms during and after dental procedures, because decreased lung function can be triggered by anxiety, supine positioning, tooth enamel dust, and aerosols commonly created by dental procedures. Set goals with the client to achieve meticulous homecare to combat negative effects of medication and mouth breathing on oral health.

Set goals with the client to achieve meticulous homecare to combat negative effects of medication and mouth breathing on oral health.TABLE 49-2 Contraindicated Drugs for the Individual with Asthma

| Drugs | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Aspirin-containing medications | Ingestion of aspirin is associated with precipitating attacks in some clients |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | Ingestion of NSAIDs may precipitate asthma attack in some individuals |

| Barbiturates and narcotics | Association of these drugs with precipitation of asthma attacks |

| Erythromycin and ciprofloxacin in clients taking theophylline | May result in toxic blood level of theophylline |

TABLE 49-3 Techniques to Be Avoided in Individuals with Certain Respiratory Diseases

| Disease | Techniques Contraindicated or Used with Precautions | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Asthma | ||

| COPD: chronic bronchitis and emphysema | ||

| Tuberculosis |

COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Procedure 49-1 MANAGEMENT OF AN ACUTE ASTHMATIC EPISODE

Adapted from Malamed SF: Medical emergencies in the dental office, ed 6, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a general term used to describe a spectrum of pulmonary disorders characterized by chronic irreversible obstruction of airflow to and from the lungs.7 COPD is considered to be preventable and treatable. However, because many individuals often experience other significant nonpulmonary conditions (weight loss, skeletal muscle wasting, cardiovascular disease, anemia, osteoporosis, and depression) associated with COPD, the severity of the disease may be affected.8

Historically the two most common diseases classified as COPD have been chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Emphysema more recently has become a pathologic term to describe the overinflation and irreversible destruction of structures in the lungs known as alveoli or air sacs. This overinflation is caused by a breakdown of the walls of the alveoli, resulting in decreased respiratory function and often dyspnea.8 Emphysema describes just one of the structural irregularities characterized by COPD. More prevalent among older men, emphysema is rapidly increasing among women primarily because of tobacco use.9 Although chronic bronchitis and emphysema can be described individually, they often coexist and represent the irreversible progression of the disease. Because of the progressive nature of COPD, quality of life is greatly compromised in severe cases.8

Bronchitis is an inflammation of the lining of the bronchial tubes. These tubes or bronchi connecting the trachea with the lungs become inflamed and/or infected. As a result, less air is able to flow to and from the lungs, and heavy mucus or phlegm is expectorated.9 Chronic bronchitis is associated with the presence of a mucus-producing cough with expectoration for at least 3 months of the year for more than 2 consecutive years, without other underlying disease to explain the cough.7 Smokers may dismiss symptoms of chronic bronchitis as a “smoker’s cough” and avoid medical care. Consequently the individual may be in danger of developing serious respiratory problems or heart failure. Chronic bronchitis is consistently more prevalent in females than in males and can affect people of all ages but is usually higher in those over 45 years old.9 With spirometry (common pulmonary test used to measure lung function), COPD can be classified into four levels: stage I, mild; stage IIA, moderate; stage IIB, moderate; and stage III, severe.

Etiology

Cigarette smoking has been identified as the major risk factor in COPD. Air pollutants and industrial dust and fumes may contribute to COPD.7,8 In some parts of the world air pollutants may be a primary risk factor for COPD.8 Underlying respiratory disease, severe respiratory infection in early childhood, underdeveloped lungs (during gestation and childhood), and genetic tendencies can all be risk factors for COPD.8

Signs and Symptoms of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

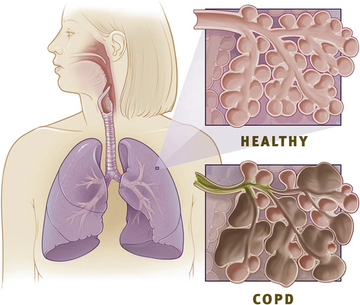

Chronic bronchitis symptoms appear gradually but intensify in individuals who smoke or when atmospheric concentrations of sulfur dioxide and other air pollutants increase. A cough producing large amounts of sputum may linger for several weeks after a winter cold seems to be cured. With time, upper respiratory infections become more serious, and coughing and expectoration of phlegm continue for longer periods after each episode.9 Dyspnea (difficulty breathing) initially is mild and is brought on only by exercise or exertion. Eventually, breathing difficulty becomes more frequent and is brought on with less effort. At this point other symptoms of respiratory failure will be evident.4 As the disease progresses and becomes more obstructive, there may be evidence of prolonged expiration and wheezing. Acute attacks of breathing distress with rapid, labored breathing, intensive coughing, and bluish skin can occur; hence the term blue bloater has been used to describe an individual with these signs.6 As seen in Figure 49-1, COPD damages the airways and sacs in the lungs by reducing the elasticity, thereby making breathing more difficult.

Figure 49-1 Comparing healthy lungs and lungs with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The elasticity of airways and sacs in healthy lungs allows air to move quickly in and out of lungs. The airways and sacs in lungs with COPD lack the elasticity to allow lungs to retain their original shape. These airways lack support and become enlarged and lined with mucus, thereby making breathing more difficult.

(From NHLBI Health Information Center, www.LearnAboutCOPD.org.)

Emphysema can be localized or generalized. Individuals with localized emphysema may have no symptoms. At the early stage, symptoms of chronic bronchitis with cough and expectoration will predominate. As with chronic bronchitis, dyspnea occurs only with exertion but gradually over time intensifies in severity and frequency. Some individuals may experience rapid progression of dyspnea and disability, and others will experience a slower progression. Chronic coughing with expectoration, wheezing, recurrent respiratory infection, and fatigue may also be present. In later stages, severe dyspnea, cyanosis, and other signs of respiratory failure may be evident.4 As with chronic bronchitis, individuals may experience periods of exacerbation of symptoms usually related to infections or other complications.

Physical findings may be normal in cases of mild or localized emphysema. However, in more advanced cases there is usually weight loss and a “barrel-chest” appearance.6,7 The client may appear short of breath and use accessory respiratory muscles. Many may find it easier to breathe in a sitting position, bent over and resting their elbows on their thighs. Usually, the expiration phase of respiration is prolonged and the client may be breathing against pursed lips. With some individuals, wheezing may be heard on expiration. In advanced stages of emphysema, cyanosis may be evident along with other signs of respiratory failure such as a change in mental state, headache, weakness, and muscle tremor or twitching.4

Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

The management of COPD includes the following components8

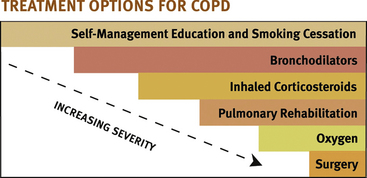

As shown in Figure 49-2, treatment options begin with self-management, education, and avoidance of risk factors, especially smoking. Relieving symptoms and improving overall health through exercise, nutritional counseling, and treatment of complications as part of pulmonary rehabilitation can greatly improve the quality of life for these individuals.8,10

Figure 49-2 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive disease but with early diagnosis may progress slowly. Providers must monitor COPD clients carefully, ensuring the treatment is appropriate for the level of disease.

(From NHLBI Health Information Center, www.LearnAboutCOPD.org.)

Drugs Commonly Used in the Treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Although there is no cure for COPD and medications cannot alter disease progression, they can improve airflow, relieve symptoms, and enhance the quality of life.8 Antibiotics are often prescribed during the acute attack of symptoms (exacerbation), particularly if there is a bacterial infection present. Bronchodilators, such as those used by asthmatics, have been commonly used as treatment. These drugs, particularly the beta2 agonists, are fast acting and, in addition to relaxing the bronchial tubes, improve mucous clearance.8

Advanced cases of COPD are often treated with the addition of more medications as the disease state progresses. Treatment is individualized and monitored based on the response to therapy and side effects reported during treatment. A long-acting beta2 agonist along with an anticholinergic may be followed by a methylxanthine as an add-on therapy for clients who have insufficient relief of symptoms. An inhaled glucocorticosteroid or combinations of medications in one inhaler may also be effective. At this stage many individuals are also on long-term oxygen therapy at home. Surgical removal of one lung may be indicated for some individuals.

Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

To meet the specialized needs of the individual with COPD, the dental hygienist should do the following:

Plan short appointments to decrease stress if client does not tolerate sitting in dental chair for long periods of time.

Plan short appointments to decrease stress if client does not tolerate sitting in dental chair for long periods of time. Review the health history for evidence of concurrent heart disease; take appropriate precautions if heart disease is present (see Chapter 42).

Review the health history for evidence of concurrent heart disease; take appropriate precautions if heart disease is present (see Chapter 42). If applicable, advise client to stop smoking and set goals with the client to initiate a smoking cessation program.

If applicable, advise client to stop smoking and set goals with the client to initiate a smoking cessation program. When needed, cautiously use dental materials with a powder component (alginate or powdered gloves), as they may worsen the client’s airway obstruction if inhaled.

When needed, cautiously use dental materials with a powder component (alginate or powdered gloves), as they may worsen the client’s airway obstruction if inhaled. Suggest low-dose oral diazepam or other benzodiazepine, as prescribed by the dentist, if needed to reduce stress.

Suggest low-dose oral diazepam or other benzodiazepine, as prescribed by the dentist, if needed to reduce stress. Be aware that clients taking systemic corticosteroids may need supplementation to avoid adrenal crisis, particularly for major dental procedures.

Be aware that clients taking systemic corticosteroids may need supplementation to avoid adrenal crisis, particularly for major dental procedures. Instruct the client to consult physician regarding herbal and drug interactions and use of alcohol if client is taking theophylline.8

Instruct the client to consult physician regarding herbal and drug interactions and use of alcohol if client is taking theophylline.8Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), an airborne communicable disease, primarily affects the lungs but also can attack other organs and tissues.9 TB is one of the oldest diseases known to strike humans and still remains one of the most widespread ailments in the world.1 Although epidemiologic data show a decline in disease incidence among Americans, the worldwide rate continues to increase. The increase in global TB cases has been attributed to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic. The suppressed immune system of HIV clients makes these individuals susceptible to opportunistic diseases such as TB, pneumonia, and other fungal, bacterial, and viral lung infections.1,5

Etiology

TB is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Close contact with persons having TB increases the incidence of disease transmission to others. The following groups are at greatest risk for contracting TB:

Signs and Symptoms

The diagnosis of TB is made via an evaluation of several assessments, including a Mantoux tuberculin skin screening, commonly called a PPD test (purified protein derivative), chest radiograph, sputum culture, and review of clinical symptoms. TB is usually a chronic infection with various clinical manifestations, depending on the stage and duration of the disease.11 Persons with primary pulmonary infection often have no clinical evidence of the disease. They test positive on a tuberculin skin test but do not have active TB and are not infectious. When symptoms are present, they are usually mild and include a low-grade fever, listlessness, loss of appetite, and occasional cough. The most common obvious symptom of active TB is a chronic cough. Other signs of disease progression include fever, night sweats, weight loss, central pulmonary necrosis (death of lung tissue), and cavitation (hollow spaces in the lungs).7

Treatment

Treatment of TB is dependent on whether an individual has active TB or only latent TB infection. Those persons who test positively for TB but do not have the disease may be treated with a preventive therapy. This treatment usually involves a daily dose of isoniazid (also called INH) or rifampin for 4 to 9 months.11 Treatment for individuals with active TB may include a short hospital stay along with the concurrent administration of several drugs prescribed for 6 to 9 months.11 Multi–drug-resistant TB is a dangerous form of TB often resulting from low patient compliance. A treatment referred to as “directly observed therapy,” which involves observing patients as they take each dose of medication, has been successful in some cases to remedy this problem. It is imperative for patients on a TB drug therapy regimen to be vigilant about taking medication as it has been prescribed even if symptoms have subsided.11

Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

When considering treatment options for the individual with TB, the major concern is the risk of disease transmission.1 TB may be transmitted from clients to dental professionals; conversely, if the clinician is infected, clients and other staff members may contract the disease. To prevent disease transmission and meet the needs of the client with TB, the dental hygienist does the following:

Uses universal infection control precautions, keeping in mind that many clients with infectious diseases such as TB may not be identified during assessments12

Uses universal infection control precautions, keeping in mind that many clients with infectious diseases such as TB may not be identified during assessments12 Recognizes signs and symptoms of TB when assessing the client’s health history, informs the dentist, and refers for medical care

Recognizes signs and symptoms of TB when assessing the client’s health history, informs the dentist, and refers for medical care Questions a client who reports a history of TB, or a positive result from a skin test for TB, concerning dates and results of chest radiographs, sputum cultures, and physical examinations by his or her physician

Questions a client who reports a history of TB, or a positive result from a skin test for TB, concerning dates and results of chest radiographs, sputum cultures, and physical examinations by his or her physician Consults with a physician to determine if it is safe to treat the client outside of a hospital setting; a client with active tuberculosis should be treated in a hospital setting under strict infection control conditions12

Consults with a physician to determine if it is safe to treat the client outside of a hospital setting; a client with active tuberculosis should be treated in a hospital setting under strict infection control conditions12 Instructs client with suspected or confirmed TB to observe strict respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette protocols; clients should be kept in the dental setting no longer than is absolutely necessary12

Instructs client with suspected or confirmed TB to observe strict respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette protocols; clients should be kept in the dental setting no longer than is absolutely necessary12CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Explain that rinsing the mouth with water after using an inhaler will decrease the risk of oral candidiasis and dental caries.

Explain that rinsing the mouth with water after using an inhaler will decrease the risk of oral candidiasis and dental caries. Explain that the use of a spacer attached to a metered dose inhaler may prevent candidiasis in asthmatics.

Explain that the use of a spacer attached to a metered dose inhaler may prevent candidiasis in asthmatics. Explain that if the client experiences xerostomia and/or an unpleasant taste after inhalant therapy, the use of xylitol-containing chewing gum will increase salivary flow, minimizing the risks of dental caries and gingivitis.

Explain that if the client experiences xerostomia and/or an unpleasant taste after inhalant therapy, the use of xylitol-containing chewing gum will increase salivary flow, minimizing the risks of dental caries and gingivitis.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Acute asthma attacks may occur before, during, and after dental procedures. Dental hygienists must be knowledgeable in the management of such an attack. Avoidance of precipitating factors is the best risk-management strategy.

Acute asthma attacks may occur before, during, and after dental procedures. Dental hygienists must be knowledgeable in the management of such an attack. Avoidance of precipitating factors is the best risk-management strategy.KEY CONCEPTS

Asthma is a respiratory disease characterized by an increased responsiveness of the airways to various stimuli, which causes periodic wheezing, dyspnea, coughing, and chest tightness.

Asthma is a respiratory disease characterized by an increased responsiveness of the airways to various stimuli, which causes periodic wheezing, dyspnea, coughing, and chest tightness. An asthma attack may be triggered by allergens, anxiety, cold air, or exercise, or no apparent irritant may be involved.

An asthma attack may be triggered by allergens, anxiety, cold air, or exercise, or no apparent irritant may be involved. Two major diseases categorized as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

Two major diseases categorized as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are emphysema and chronic bronchitis. COPD is most often caused by cigarette smoking, but chronic exposure to occupational and environmental pollutants is also a risk factor contributing to COPD.

COPD is most often caused by cigarette smoking, but chronic exposure to occupational and environmental pollutants is also a risk factor contributing to COPD. The major risk associated with treating clients with active tuberculosis is disease transmission; clients with active tuberculosis should be treated in a hospital setting only for emergency dental care.

The major risk associated with treating clients with active tuberculosis is disease transmission; clients with active tuberculosis should be treated in a hospital setting only for emergency dental care. Patient compliance problems during lengthy drug therapy for tuberculosis have contributed to the problem of multi–drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis.

Patient compliance problems during lengthy drug therapy for tuberculosis have contributed to the problem of multi–drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis. There is a link between periodontal disease and systemic illnesses such as lower respiratory tract infections.

There is a link between periodontal disease and systemic illnesses such as lower respiratory tract infections.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Profile: A 5’10", 18-year-old white man, weighing 175 lb, arriving for dental hygiene care.

Chief Complaint: “My gums bleed, particularly around my upper front teeth, and I have a dry mouth most of the time, which is very uncomfortable.”

Health History: Client’s vital signs are as follows: blood pressure of 112/64 mm Hg, pulse rate of 70 bpm, and respiration rate of 14 rpm. Client reports history of asthma for past 10 years, exacerbated by exposure to cats, pollens, and dust. Currently sees physician for acne and a chiropractor for lower back pain. Currently takes doxycycline 100 mg daily for acne and Alupent 650 mcg aerosol inhaler (one puff as needed for asthma attack).

Social History: Client is single and lives with parents. He appears very quiet and reserved.

Dental History: Suspected carious lesions on occlusal surfaces of teeth 2, 3, 15, and 31.

Gingival evaluation reveals slight gingival enlargement and rolled margins throughout with moderately enlarged, erythematous gingiva and bulbous papillae in the maxillary anterior facial region. Pocket depths 3 mm or less throughout, except in maxillary anterior and posterior molar regions, where some 4- to 5-mm pockets were noted.

Oral Health Behavior Assessment: Client brushes twice daily but does not floss. Moderate plaque biofilm throughout on the gingival third of teeth and interproximal surfaces.

Refer to the Procedures Manual where rationales are provided for the steps outlined in the procedure presented in this chapter.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in tuberculosis incidence—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:281.

2. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel: Expert Panel report 3 (EPR3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm. Accessed February 14, 2008.

3. Jaakkola M.S., Leino T., Tammilehto L., et al. Respiratory effects of exposure to methacrylates among dental assistants. Allergy. 2007;62:648.

4. Malamed S.F. Medical emergencies in the dental office, ed 6. St Louis: Mosby; 2007.

5. American Lung Association: Lung disease data. Available at: www.lungusa.org/site/apps/s/content.asp?c=dvLUK9O0E&;b=34706&ct=67659. Accessed February 14, 2008.

6. Hupp W.S. Dental management of patients with obstructive pulmonary diseases. Dent Clin North Am. 2006;50:513.

7. Des Jardins T.R. Clinical manifestations and assessment of respiratory disease. St Louis: Mosby; 2006.

8. Global Initiative on Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Available at: www.goldcopd.com. Accessed October 30, 2007.

9. American Lung Association: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) fact sheet: June 2008. Available at: http://www.lungusa.org/site/apps/nlnet/content3.aspx?c=dvLUK9O0E&b=4294229&ct=3052283. Accessed December 23, 2008.

10. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute: Diseases and conditions index. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/Copd/Copd_WhatIs.html. Accessed November 12, 2007.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: TB facts for health care workers. Available at: www.cdc.gov/tb/pubs/TBfacts_HealthWorkers/tbfacts_update.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2008.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5417a1.htm. Accessed February 14, 2008.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..