CHAPTER 42 Cardiovascular Disease

Discuss cardiovascular disease in terms of risk and protective factors and links to periodontal disease.

Discuss cardiovascular disease in terms of risk and protective factors and links to periodontal disease.CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

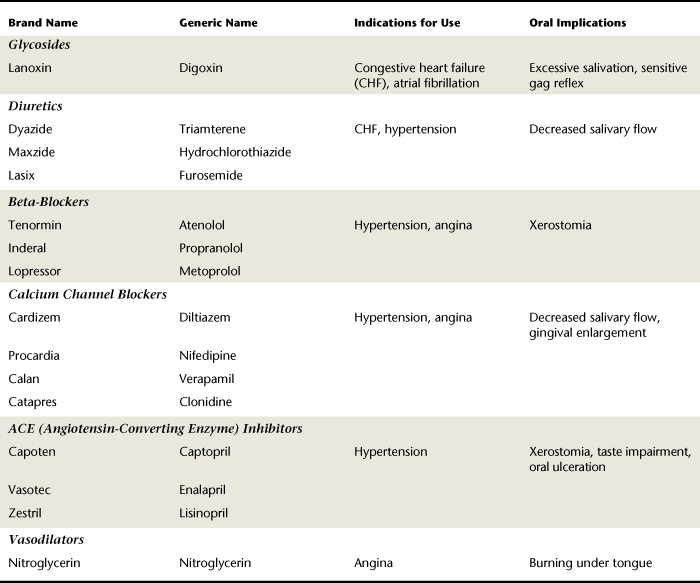

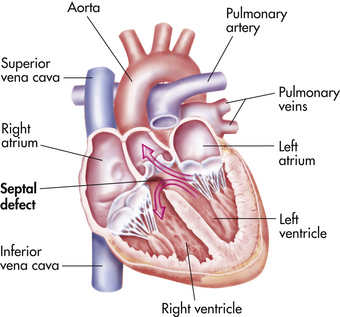

Normal cardiovascular structure and physiology establish the baseline for discussion of cardiac pathology (Figure 42-1).

Figure 42-1 Diagram of the heart.

(From Thibodeau GA, Patton KT: Anatomy and physiology, ed 6, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), an alteration of the heart and/or blood vessels that impairs function, is the leading cause of death, responsible for 30% of all deaths or 17.5 million people worldwide.1 Prevention through management of CVD risk factors remains key. Risk factors associated with poor cardiovascular health are listed in Table 42-1.

TABLE 42-1 Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease

| Factors | Examples |

|---|---|

| Nonmodifiable Risk Factors | |

| Personal Factors | |

| Genetic predisposition or family history | Family members have cardiovascular disease; congenital abnormality |

| Age | Pathologic changes within coronary arteries severe enough to cause symptoms appear predominantly in persons >40 years of age |

| Race | Blacks and Hispanics are more likely to have cardiovascular disease than whites or Pacific Islanders |

| Gender | Men are four times as likely to have coronary heart disease as women up to age 40 years |

| Disease Patterns | |

| History of anorexia nervosa or bulimia | Women <40 years old are at increased risk of developing coronary heart disease if they have (had) an eating disorder |

| Past use of fen-phen (fenfluramine and phentermine) | May damage heart valves if used longer than 2 months |

| Modifiable Risk Factors | |

| Personality traits (type A personality) | Hard-driving, competitive individuals who worry excessively about deadlines and consistently overwork |

| Professional stresses | Occupations that impose tremendous responsibility |

| Oral contraceptive use | Women <40 years of age who take oral contraceptives |

| Tobacco use | Smoking increases risk of coronary heart disease |

| Sedentary occupation and lifestyle | Lack of exercise promotes mental depression and obesity |

| Diet high in calories, cholesterol, fat, and sodium | Overeating and consuming fatty foods promote obesity, lipid abnormalities, diabetes, metabolic syndrome; high-sodium diet promotes hypertension |

| Hypertension | Individuals with sustained blood pressure of 160/95 mm Hg or higher double their risk of myocardial infarction |

| Obesity | Weight 30% or more above that considered standard for an individual of a certain height and build |

| Lipid abnormalities | Serum cholesterol >200 mg/100 mL or a fasting triglyceride of >250 mg/100 mL; abnormal level of C-reactive protein |

| Diabetes mellitus | Fasting blood sugar of >120 mg/dL, or a routine blood sugar level of ≥180 mg/dL increases risk |

| Periodontal disease | Periodontal disease increases chronic systemic inflammation, possibly increasing risk of fatal cardiovascular disease |

Research suggests that chronic infections, such as periodontitis, are associated with increased risk for CVD.2 Although the exact link is unclear, there is evidence to propose that periodontal infection is associated with elevated plasma levels of atherogenic lipoprotein.3 It is also believed that the chronic systemic inflammatory and immune response in persons with periodontitis may increase CVD risk.4-6 Changing risk-related behaviors assists in decreasing the risk and prevalence of heart disease in the population (see Table 42-1).

Rheumatic Heart Disease

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is the cardiac manifestation of rheumatic fever. Persons with a history of rheumatic fever often have valvular heart damage that is detrimentally affected by bacteremia (the assault of microorganisms in the bloodstream), often occurring during dental hygiene care. Persons with a history of RHD are not at high risk for infective endocarditis (IE), and prophylactic antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene care is not required.

Etiology

Rheumatic fever is an acute or chronic systemic inflammatory process characterized by attacks of fever, polyarthritis, and carditis. The latter may eventually result in permanent valvular heart damage.

Risk Factors

Persons who have had a beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngeal infection (strep throat) may develop rheumatic fever within 2 to 3 weeks after initial infection. People with a history of rheumatic fever are predisposed to RHD because of the involvement of the heart muscles, resulting in cardiac valve damage.

Disease Process

The most destructive effect of rheumatic fever is carditis, an inflammation of the cardiac muscle that is found in most individuals exhibiting signs and symptoms of rheumatic fever. Carditis may affect the endocardium, myocardium, pericardium, or heart valves. Valvular damage is responsible for the familiar organic (nonfunctional) heart murmur associated with rheumatic fever and RHD. The heart murmur is an irregularity of the auditory heartbeat caused by a turbulent flow of blood through a valve that has failed to close. Valves most commonly affected are the mitral valve and the aortic valve. Damaged valves are susceptible to infection that may lead to IE. Severe rheumatic carditis may cause difficulty in breathing, elevation of diastolic blood pressure, and increasing signs of heart failure.

Prevention

RHD prevention requires early diagnosis and treatment of streptococcal pharyngeal infections that may lead to rheumatic fever. Clients need to be informed of the importance of early medical diagnosis and treatment for prevention of this disease.

Dental Hygiene Care

According to the American Heart Association’s Guidelines for the Prevention of Infective Endocarditis, prophylactic antibiotic premedication is not required for clients with RHD.7 To protect clients from health risks, the care plan must include meticulous oral biofilm control. Good oral health maintenance by the client reduces the possibility of developing a self-inflicted bacteremia during toothbrushing or interdental cleaning.

Infective Endocarditis

Infective or bacterial endocarditis is an infection of the endocardium, heart valves, or cardiac prosthesis resulting from microbial invasion.

Etiology

IE, caused by the formation of a bacteremia (the presence of microorganisms in the bloodstream), is characterized in most cases by vegetative growths of Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus viridans, and, the most prevalent, alpha-hemolytic streptococci on heart valves or endocardial lining. Although staphylococci and streptococci are found in the majority of cases, yeast, fungi, and viruses also have been identified, hence the term infective rather than bacterial. If untreated, endocarditis is usually fatal; with proper antibiotic treatment, recovery is possible.

Risk Factors

During invasive dental or dental hygiene therapy (defined as procedures that involve manipulation of oral soft tissues, manipulation of the periapical area of teeth, or oral mucosa perforation), a transient bacteremia is produced. Tissue trauma from instrumentation coupled with periodontal disease status determines the severity of infection. In addition, a client may induce bacteremia via mastication and daily oral hygiene care. Risk factors for IE include clients with a previous history of endocarditis, artificial heart valves, or serious congenital heart conditions and heart transplant patients who develop a problem with a heart valve.7 Table 10-4 in Chapter 10 delineates risk categories associated with IE. Box 10-4 in Chapter 10 summarizes indications for antibiotic prophylaxis.

Disease Process

There are two types of IE, as follows:

Acute bacterial endocarditis (ABE) is a severe infection with a rapid course of action usually caused by pathogenic microorganisms, such as S. aureus and S. epidermidis, that are capable of producing widespread disease.

Acute bacterial endocarditis (ABE) is a severe infection with a rapid course of action usually caused by pathogenic microorganisms, such as S. aureus and S. epidermidis, that are capable of producing widespread disease. Subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) is a slow-moving infection with nonspecific clinical features. Affected persons usually exhibit a continuous low-grade fever, marked weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and joint pain. Dental and dental hygiene procedures that manipulate soft tissue may be responsible for the development of SBE. As endocarditis progresses, the circulating microorganisms attach to the damaged heart valves or other susceptible areas and proliferate in colonies. This invasion results in cardiac failure from continued valvular damage and embolization (vessel obstruction) owing to fragmentation of the colonized microorganisms (Box 42-1).

Subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) is a slow-moving infection with nonspecific clinical features. Affected persons usually exhibit a continuous low-grade fever, marked weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and joint pain. Dental and dental hygiene procedures that manipulate soft tissue may be responsible for the development of SBE. As endocarditis progresses, the circulating microorganisms attach to the damaged heart valves or other susceptible areas and proliferate in colonies. This invasion results in cardiac failure from continued valvular damage and embolization (vessel obstruction) owing to fragmentation of the colonized microorganisms (Box 42-1).BOX 42-1 Sample Dental Hygiene Care Plan: Client Needs Prophylactic Antibiotic Premedication

Dental Hygiene Diagnosis

Dental Hygiene Interventions

Appointment 1

Prevention

Clients with conditions that increase their susceptibility to IE, such as previous IE, unrepaired cyanotic congenital heart disease (CHD), completely repaired congenital heart defect with prosthetic material or device within the first 6 months after the procedure, repaired CHD with residual defects at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device (which inhibits endothelialization), cardiac valvulopathy in cardiovascular transplantation recipients, and prosthetic cardiac valves, all require preventive antibiotic therapy before procedures that produce bacteremias (see Chapter 10Box 10-4Box 10-5Table 10-4Table 10-5Table 10-6Table 10-7).7

Dental Hygiene Care

To prevent IE, do the following:

Ensure that preventive antibiotic is administered 1 hour before procedures that produce bacteremias so optimal blood levels are established (see Chapter 10Table 10-5Table 10-6Table 10-7).

Ensure that preventive antibiotic is administered 1 hour before procedures that produce bacteremias so optimal blood levels are established (see Chapter 10Table 10-5Table 10-6Table 10-7).Appointment Guidelines (see Chapter 10, Table 10-6)

When a client is taking the prescribed prophylactic antibiotic regimen, appointment scheduling is affected. It is not in the client’s best interest to prolong treatment procedures. If therapeutic scaling and root planing are necessary, appointments should be scheduled in longer periods and as close together as possible. The interval between antibiotic coverage should be 9 to 14 days. If a client has type II periodontal disease, a care plan may divide invasive procedures (therapeutic scaling and root planing) into an organized sequence that allows for 9- to 14-day periods between prophylactic antibiotic premedication. The client’s human need for protection from health risks is met by dividing the invasive treatment appointments into two separate intervals with a lag time between the appointments. See Box 42-1.

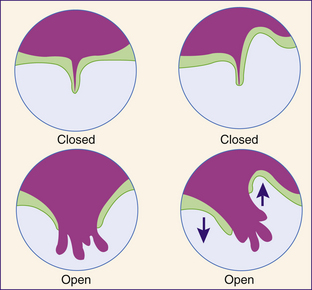

Valvular Heart Defects

Valvular heart defects (VHDs) result in cardiovascular damage from malfunctioning heart valves such as the mitral valve, the aortic valve, or the tricuspid valve (see Figure 42-1). Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is one of the most frequently occurring VHDs. When the left ventricle pumps blood to the aorta, the mitral valve flops backward (prolapses) into the left atrium, resulting in MVP. Other names for MVP are “floppy mitral valve syndrome” and the “click murmur syndrome,” referring to the sound the valve makes when it flops backward (Figure 42-2).

Figure 42-2 Diagram of a normal and a prolapsed mitral valve.

(Courtesy Mid-Island Hospital, Bethpage, New York.)

Etiology

VHDs are commonly associated with rheumatic fever but may also be caused by congenital abnormalities or may develop after IE.

Disease Process

Valvular malfunction can occur by stenosis, an incomplete opening of the valve, or regurgitation, a backflow of blood through the valve because of incomplete closure. When malfunction occurs, the left ventricle hypertrophies to compensate for the increased amount of blood. This, in turn, causes the left atrium to hypertrophy, leading to pulmonary congestion and right ventricular failure. If the condition is left untreated, the person ultimately develops congestive heart failure (CHF).

An echocardiogram enables the physician to diagnose a VHD. Ultrasound (use of sound waves) evaluates the heart size, as well as chamber and valve function, during an echocardiogram.

Medical Treatment

Corrective surgery is done for most VHDs. If the valve cannot be repaired, in most cases prosthetic valves are available to replace defective valves. For clients with MVP, surgical treatment (not always necessary) is aimed at alleviating symptoms such as palpitations, chest pain, nervousness, shortness of breath, and dizziness. Medications are given to control chest pain, slow the heart rate, reduce palpitations, and/or lower anxiety.

Dental Hygiene Care

To protect the client from health risks, frequent continued care appointments and meticulous daily oral biofilm control are necessary. Good oral health maintenance reduces the possibility of developing a bacteremia from toothbrushing or interdental cleaning. In cases where defective valves are replaced with prosthetic valves, prophylactic antibiotic premedication is required before dental hygiene care (see Chapter 10Box 10-4Box 10-5Table 10-4Table 10-5Table 10-6).

Appointment Guidelines

VHDs require care plan modifications if the client has an underlying cardiovascular condition or is on anticoagulant drug therapy. The frequently prescribed anticoagulants—heparin, warfarin (Coumadin), and indanedione derivatives—affect the dental hygiene care plan if scaling or root planing procedures are indicated or if the gingiva bleed spontaneously.

Consultation with the client’s physician is recommended to validate the client’s current health and medication status.

When the client is taking anticoagulant medication, the client’s physician is consulted to determine if a dose reduction should be made or if it is safer to maintain the prescribed dosage.

Optimal prothrombin time for dental hygiene therapy in persons taking anticoagulants should be <20 seconds on the day of the scheduled procedure.8

Optimal prothrombin time for dental hygiene therapy in persons taking anticoagulants should be <20 seconds on the day of the scheduled procedure.8For laboratory consistency, the International Normalization Ratio (INR) is used to document bleeding time. When the INR value is used, normal range is <1.5 and routine care can be performed when the INR is 2 to 3.8 When treating a client on anticoagulant medication, do the following:

Hypertensive Cardiovascular Disease

Hypertensive cardiovascular disease (HCD) or hypertension is a persistent elevation of the systolic and diastolic blood pressures at or above 140 mm Hg and 90 mm Hg, respectively (see Chapter 11). Half of the 60 million hypertensive people in the United States are undiagnosed. Many individuals with diagnosed hypertension are not treated or are inadequately treated, leaving the client’s condition uncontrolled and the client at risk for other serious diseases.

Etiology

Hypertension is not considered a disease but rather a physical finding or symptom. A sustained, elevated blood pressure affects the heart and leads to HCD, resulting in heart failure, myocardial infarction (MI), cerebrovascular accident (stroke), and kidney failure.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for hypertension include family history, race, stress, obesity, a high dietary intake of saturated fats or sodium, use of tobacco or oral contraceptives, fast-paced lifestyle, and age (over age 40). Hypertension is three times more common in obese persons than in normal-weight persons. There is a higher incidence of hypertension among African Americans than American whites.

Disease Process

The two major types of hypertension are as follows:

Primary hypertension (essential idiopathic hypertension), with cause unknown, is the most common type, characterized by a gradual onset or an abrupt onset of short duration.

Primary hypertension (essential idiopathic hypertension), with cause unknown, is the most common type, characterized by a gradual onset or an abrupt onset of short duration. Secondary hypertension is the result of an existing disease of the cardiovascular system, renal system, adrenal glands, or neurologic system. Because hypertension usually follows a chronic course, the client may be asymptomatic. Early clinical signs and symptoms are occipital headaches, vision changes, ringing ears, dizziness, and weakness of the hands and feet. As the condition persists, advanced signs and symptoms can include hemorrhages, enlargement of the left ventricle, CHF, angina pectoris, and renal failure.

Secondary hypertension is the result of an existing disease of the cardiovascular system, renal system, adrenal glands, or neurologic system. Because hypertension usually follows a chronic course, the client may be asymptomatic. Early clinical signs and symptoms are occipital headaches, vision changes, ringing ears, dizziness, and weakness of the hands and feet. As the condition persists, advanced signs and symptoms can include hemorrhages, enlargement of the left ventricle, CHF, angina pectoris, and renal failure.The dental hygienist refers clients for medical diagnosis if a hypertensive disorder is suspected.

Prevention

Blood pressure measurement identifies individuals with hypertensive heart disease (see Chapter 11). Early identification of hypertensive clients minimizes the occurrence of medical emergencies, helps meet the client’s human need for protection from health risks, and may be life-saving for undiagnosed individuals.

Medical Treatment

Treatment of hypertension aims at lifestyle changes to reduce risk factors, antihypertensive drug therapy, and/or correction of the underlying medical condition in the case of secondary hypertension. The goal is to reduce and maintain the diastolic pressure level at 90 mm Hg or lower. Some clients need only to watch their dietary consumption of sodium and saturated fats; others must reduce daily stress level and alter their lifestyle (see Table 42-1). When a client needs drug therapy, periodic monitoring is essential. Some drugs may stabilize the condition temporarily and then an elevation can occur, indicating that an alternative drug is needed.

Drugs used for hypertension vary in their method of action as follows:

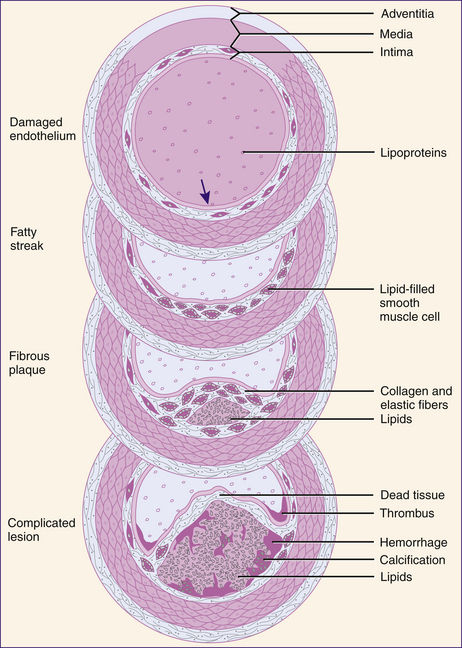

Clients receiving hypertensive drug therapy may experience fatigue, gastrointestinal disturbances, nausea, diarrhea, cramps, xerostomia, orthostatic hypotension with dizziness, and/or depression (Table 42-2).

Dental Hygiene Care

If the individual’s hypertension is uncontrolled, treatment is postponed until the disorder is regulated. If the client is being treated with antihypertensive agents and if clinical blood pressure evaluations are within normal limits, care can continue; however, stress and anxiety reduction strategies and local anesthetic drug modification will reduce the risk for medical emergencies. Drug considerations for use of local anesthetics in clients with hypertensive heart disease are based on the careful use of vasopressors (such as epinephrine), which constrict blood vessels, concentrate the anesthetic in the desired area, and prevent its dissipation. A vasopressor side effect is elevation in blood pressure. In normal persons a slight elevation in blood pressure is harmless; however, with vasopressors, hypertensive individuals have increased risk of cerebrovascular accident, MI, and CHF. Therefore anesthetic agents with vasopressors are relative contraindications in persons with a history of hypertension (see Chapter 39). The risk versus the benefit of using a low concentration of epinephrine to local anesthetic agent is considered, and the physician of record should be consulted.

Appointment Guidelines (see Chapter 10, Table 10-6)

Care plan considerations for individuals with controlled hypertension focus on stress reduction strategies (see Chapter 37) and local anesthetic drug modification to reduce potential for medical emergencies (as discussed in previous section). Box 42-2 displays cases based on initial blood pressure measurement and family history information. Each situation demonstrates appropriate dental hygiene care modifications to meet a specific human need.

BOX 42-2 Clients with Various Hypertensive Conditions and Appropriate Dental Hygiene Actions

Client with No History of Hypertension, Elevated Blood Pressure

During assessment, client reports no history or symptoms of hypertension; however, a blood pressure reading of 160/100 mm Hg was obtained. One dental hygiene diagnosis may be an unmet need for protection from health risks caused by a potential for heart attack or stroke as evidenced by an elevated blood pressure of 160/100 mm Hg. The dental hygienist should repeat blood pressure measurements during the assessment phase, approximately 5 to 10 minutes apart. If after repeated measurements the diastolic pressure is still >100 mm Hg, the appointment should be limited to assessment and planning; no treatment is implemented. The client must be referred to the physician of record for medical consultation and diagnosis. If the client is diagnosed as nonhypertensive by the physician, it can be inferred that dental care anxiety causes the elevated blood pressure. Blood pressure must be monitored at each appointment thereafter and strategies implemented to minimize stress.

Client under Treatment for Hypertension

During assessment, client indicates that he is hypertensive and under a physician’s care. At each visit the hygienist obtains information on the client’s medications and verifies that the prescribed medication has been taken. Client may have an unmet need for freedom from fear and stress; therefore the care plan may include the administration of nitrous oxide–oxygen analgesia to reduce client anxiety. At each visit the client’s blood pressure is monitored, periodically remeasured, and recorded.

Client Noncompliant with Hypertension Treatment

Client indicates that she is hypertensive and has discontinued her recommended medication because it is too expensive. Rather, she takes the medication irregularly based on her symptoms. This client has uncontrolled hypertension and a need for protection from health risks. Dental hygiene care is stopped after assessment and should not resume until her hypertension is stabilized. Client is referred to her physician for further medical evaluation and treatment. Although dental hygiene care is postponed, remaining appointment time can facilitate the client’s need for protection from health risks via educational strategies directed toward the importance of controlling hypertension, information about the oral inflammation and systemic inflammation link, and possible lethal effects if hypertension is uncontrolled. Throughout the appointment the client’s blood pressure is monitored and recorded periodically.

Client with Hypertension and Acute Symptoms

During assessment, client demonstrates hypertension with diastolic readings >110 mm Hg and symptoms (e.g., headache, dizziness, restlessness, decreased level of consciousness, blurred vision, palpitations) indicative of hypertensive cardiovascular disease (HCD). To meet the client’s need for protection from health risks, client is referred to his physician for immediate medical consultation and evaluation. Dental hygiene care is delayed until the HCD is controlled. Because hypertension can be related to anxiety and stress, the dental hygienist must determine if client needs stress management and, if affirmative, can reduce apprehension associated with therapy (e.g., encourage client to express fears and concerns, involve client in goal setting and care planning, explain procedures completely, obtain informed consent, demonstrate humanistic behaviors, and discuss apprehensions directly).

Coronary Heart Disease

Coronary heart disease (coronary artery disease or ischemic heart disease) results from insufficient blood flow from the coronary arteries into the heart or myocardium. Disorders associated with this condition are arteriosclerotic heart disease, angina pectoris, coronary insufficiency, and MI.

Etiology

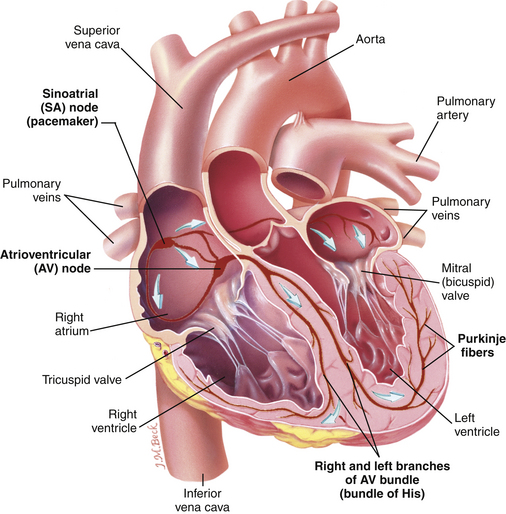

The major cause of coronary heart disease is atherosclerosis, a narrowing of the lumen of the coronary arteries, thereby reducing blood flow volume. Narrowing of the lumen occurs by deposition of fibro-fatty substances containing lipids and cholesterol. Deposits thicken with time and eventually occlude the vessel (Figure 42-3). Atherosclerosis usually develops in high-flow, high-pressure arteries and has been linked to many risk factors. Other causes of coronary heart disease are congenital abnormalities of the arteries and changes in the arteries due to infection, autoimmune disorders, and coronary embolism (blood clot).

Risk Factors

Coronary heart disease is influenced by age, gender, race, diet, lifestyle, and environment. Individuals who are obese, anorectic, bulimic or physically inactive or who smoke increase their coronary heart disease risk (see Table 42-1).

Age. Being older than 40 is associated with coronary heart disease. Pathologic changes in the arteries are noticeable with age, usually producing disease symptoms.

Age. Being older than 40 is associated with coronary heart disease. Pathologic changes in the arteries are noticeable with age, usually producing disease symptoms. Gender. Men are four times more likely to suffer from coronary heart disease than women up to age 40; after age 40, prevalence of coronary heart disease among women and men is the same. Women younger than 40 years old are at an increased risk for developing coronary heart disease if they are taking oral contraceptives or have a history of anorexia nervosa or bulimia.

Gender. Men are four times more likely to suffer from coronary heart disease than women up to age 40; after age 40, prevalence of coronary heart disease among women and men is the same. Women younger than 40 years old are at an increased risk for developing coronary heart disease if they are taking oral contraceptives or have a history of anorexia nervosa or bulimia. Race. White men and nonwhite women are at a higher risk for coronary heart disease than nonwhite men and white women. Researchers are trying to determine the genetic factors involved; however, a familial connection is suspected.

Race. White men and nonwhite women are at a higher risk for coronary heart disease than nonwhite men and white women. Researchers are trying to determine the genetic factors involved; however, a familial connection is suspected. Diet. Populations in which a low-cholesterol, low-fat diet is consumed have little coronary heart disease; populations in which the diet consists of foods rich in cholesterol and saturated fat have a very high rate of coronary heart disease.

Diet. Populations in which a low-cholesterol, low-fat diet is consumed have little coronary heart disease; populations in which the diet consists of foods rich in cholesterol and saturated fat have a very high rate of coronary heart disease. Environment. Coronary heart disease is seven times more prevalent in North America than in South America, and urban populations are at a higher risk than rural dwellers. Stressful life situations increase an individual’s chance of developing coronary heart disease at an early age.

Environment. Coronary heart disease is seven times more prevalent in North America than in South America, and urban populations are at a higher risk than rural dwellers. Stressful life situations increase an individual’s chance of developing coronary heart disease at an early age.Disease Process

Basic manifestations of coronary heart disease are angina pectoris, MI, and sudden death.

Angina Pectoris

Angina pectoris is the direct result of inadequate oxygen flow to the myocardium, manifested clinically as a burning, squeezing, or crushing tightness in the chest that radiates to the left arm, neck, and shoulder blade. The person typically clenches a fist over the chest or rubs the left arm when describing the pain. When sudden attacks of angina pectoris follow physical exertion, emotional excitement, or exposure to cold, and the symptoms are relieved by administration of nitroglycerin, they are classified as stable angina. Conversely, unstable angina may occur at rest or during sleep, and pain is of longer duration and not relieved readily with nitroglycerin.

Medical treatment for angina pectoris has two goals: reduce myocardial oxygen demand and increase oxygen supply. Therapy consists primarily of physical rest to decrease oxygen demand and the administration of nitrates, such as nitroglycerin, to provide more oxygen. Nitroglycerin (glyceryl trinitrate) is a vasodilator that increases blood flow (oxygen supply) by expanding the arteries. Administration can be sublingual for immediate absorption, or by nitroglycerin pads and patches for time-released medication absorbed by the skin and into the bloodstream; an overdose can cause headache. Obstructive lesions that do not respond to drug therapy may necessitate surgery.

Myocardial Infarction

MI, the second manifestation of coronary heart disease, is a reduction of blood flow through one of the coronary arteries, resulting in an infarct. An infarct is an area of tissue that undergoes necrosis because of the elimination of blood flow. An MI is also known as a heart attack, coronary occlusion, and coronary thrombosis.

Symptoms associated with MI are similar to those experienced with angina pectoris; however, the pain usually persists for 12 or more hours and begins as a feeling of indigestion. Other manifestations include a feeling of fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and shortness of breath.

Medical treatment includes combination therapy to reduce cardiac workloads and increase cardiac output. Cardiac workload reduction therapies include bed rest, morphine for pain reduction and sedation, and oxygen if necessary. To increase cardiac output, therapy for the control and reduction of cardiac dysrhythmias is recommended (e.g., antiarrhythmic drugs, possibly a cardiac pacemaker). Nitroglycerin can relieve chest pain and increase cardiac output by intensifying the blood flow and redistributing blood to the affected myocardial tissue. Anticoagulants may be used to thin the blood in an effort to increase blood flow and reduce the possibility of another MI.

Sudden Death

Sudden death, the last manifestation of coronary heart disease, occurs during the first 24 to 48 hours after the onset of symptoms. Most sudden cardiovascular deaths are caused by ventricular fibrillation. For example, ventricular fibrillation results in ventricular standstill (cardiac arrest) if insufficient blood is pumped into the coronary arteries to supply the myocardium with oxygen. Biologic death results when oxygen delivery to the brain is inadequate for 4 to 6 minutes. Therefore the use of an automated external defibrillator (AED) (also known as precordial shock) is followed by cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to maintain enough blood oxygen to sustain life. Transportation to the hospital for emergency medical care is necessary.

Prevention

Lifestyle behaviors associated with the prevention of coronary heart disease are as follows:

Healthy diet (e.g., reduction in saturated fat and cholesterol; increases in whole grains, fruits, and vegetables)

Healthy diet (e.g., reduction in saturated fat and cholesterol; increases in whole grains, fruits, and vegetables)Factors associated with coronary heart disease must be taken into consideration when providing nutritional counseling to improve a client’s oral health. In facilitating the client’s human need for protection from health risks, the dental hygienist recognizes the importance of dietary choices related to coronary heart disease and incorporates that knowledge into the nutritional education session (see Chapter 33).

Given that periodontal disease is a risk factor for coronary heart disease, clients will need this information to make sound decisions about their oral health. Therefore client education should emphasize the link between oral disease and systemic disease. By stressing the importance of oral disease prevention, the dental hygienist promotes active self-care by the client—for example, teaching self-care behaviors to maintain oral wellness, encouraging active participation in formulating goals for care, and facilitating choices and client decision making.

Dental Hygiene Care

Clients with coronary heart disease are susceptible to angina pectoris and MI.

Angina Pectoris

The client with angina pectoris should be treated in a stress-free environment to meet the client’s need for protection from health risks and freedom from stress. Considerations associated with angina pectoris include identification of the client’s condition and frequency of angina attacks. Health history interview questions to ascertain the stability of the client’s angina are as follows:

If the client reports that his or her angina has worsened and that the painful episodes occur more frequently and not only during exertion, then the client’s condition is classified as unstable angina. These clients should be referred to their physician of record, and dental hygiene care postponed.

For clients with stable angina, appointments should be short and preferably scheduled for the morning. The atmosphere should be friendly and conducive to relaxation. If the client becomes fatigued or develops significant changes in pulse rate or rhythm, termination of the appointment is suggested.

Before care for a client with a history of angina pectoris is initiated, the client’s supply of nitroglycerin should be placed within reach of the dental hygienist. Potency of nitroglycerin is lost after 6 months outside of a sealed container; consequently, fresh supplies should be available in the oral care environment. If an emergency develops, dental hygiene treatment is stopped; the client is placed in an upright position, reassured, and given nitroglycerin sublingually. Emergency medical services (EMS) should be activated if the client continues to experience pain after administration of nitroglycerin. Vital signs must be monitored and recorded on the client’s record.

Myocardial Infarction

Clients who have a history of MI with no complications do not require care plan modifications. However, if the MI has occurred within the past 6 months, dental hygiene therapy should be postponed until the individual is 6 months or more postinfarction with no complications. The client’s medical status should be confirmed with the cardiologist of record during assessment.

Drugs used to treat MI are anticoagulants, digitalis, and antihypertensive agents. These drugs necessitate care plan alterations. Anticoagulant drugs increase bleeding time and may have to be stopped several days before care that involves tissue manipulation. Some cardiologists believe that it is more dangerous to take the individual off the anticoagulant than it is to keep the individual on the drug and provide care; therefore confirmation from the client’s cardiologist is recommended.

Digitalis, a glycoside, is a drug that increases the contractility of the heart. Improvement in force makes the heart more efficient as a pump, increasing its volume in relation to cardiac output. The most commonly prescribed digitalis drug is digoxin (Lanoxin).

Oral health professionals may detect early signs of digitalis toxicity in clients (i.e., anorexia, nausea, vomiting, neurologic abnormalities, and facial pain).9 If digitalis toxicity is not detected early, cardiac irregularities can develop (e.g., arrhythmias can progress to ventricular fibrillation and sudden death).

Antihypertensive agents used to control MIs are similar to those used to control hypertension. These agents do not influence the care plan unless the underlying condition is uncontrolled.

Clients with coronary heart disease may experience fear, depression, and disturbances in body image, associated with a change in lifestyle (e.g., dietary restrictions, exercise, and maintaining low stress). The client’s psychologic condition also may influence oral health.

Emergency situations associated with MI should be managed by an emergency medical team. Oral health professionals are responsible for monitoring vital signs, administering nitroglycerin, and performing AED and CPR if the client experiences cardiac arrest. Certification in Basic Life Support (BLS) should be maintained by all oral health professionals (see Chapter 8).

Cardiac Dysrhythmias and Arrhythmias

Cardiac dysrhythmias and arrhythmias, terms used interchangeably, are dysfunctions of heart rate and rhythm that manifest themselves as heart palpations. Dysrhythmias may develop in both normal and diseased hearts. In healthy hearts, arrhythmia may be associated with physical and emotional stresses (e.g., exercise, emotional shock) and usually subsides in direct response to stimulus reduction. Diseased hearts develop dysrhythmias directly associated with the CVD present, most commonly RHD, arteriosclerotic heart disease, or coronary artery disease. In some cases a cardiac dysrhythmia may develop in response to drug toxicities and electrolyte imbalances.

Etiology

Dysfunction of heart rate and rhythm arises from disturbances in nerve impulse formation or nerve impulse conduction and is categorized according to the part of the heart in which it originates. Common dysrhythmias include bradycardia, tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), ventricular fibrillation, and heart block.

Cardiac dysrhythmias are medically diagnosed using an electrocardiogram (ECG) and/or a Holter monitoring system. The ECG, a graphic tracing of the heart’s electrical activity, determines heart rate, rhythm, and size. Each dysrhythmia is associated with a specific graphic pattern indicating a definitive medical diagnosis.

Disease Process

Bradycardia

Bradycardia is defined as slowness of the heartbeat as evidenced by a decline in the pulse rate to less than 60 beats per minute (BPM). This normally occurs during sleeping; however, severe bradycardia can lead to fainting and convulsions. If a client has an episode of bradycardia following a normal pulse rate of 80 BPM, emergency medical treatment is necessary. This individual may be encountering the initial symptoms of an acute MI. Emergency medical treatment would include discontinuance of the dental hygiene appointment, oxygen administration, and activation of EMS.

Tachycardia

Increased heartbeat, termed tachycardia, is associated with an abnormally high heart rate, usually greater than 100 BPM. Tachycardia can increase risk of developing angina pectoris, acute heart failure, pulmonary edema, and MI if not controlled. These conditions are directly related to the amount of work the heart is doing and decreased cardiac output. Treatment consists of antiarrhythmic drug therapy to control tachycardia and reduce potential of recurrence.

Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation, a condition of rapid, uneven contractions in the upper chambers of the heart (atrium), is the result of inconsistent impulses through the atrioventricular (AV) node transmitted to the ventricles at irregular intervals. The lower chambers (ventricles) cannot contract in response to the impulses, the contractions become irregular, with a decreased amount of blood pumped through the body.

During assessment the pulse rate may appear consistent with periods of irregular beats. Medical treatment targets the causative factors, not the condition itself. CHF, mitral valve stenosis, and hyperthyroidism may be linked to atrial fibrillation.

Premature Ventricular Contractions

PVCs are easily identified as pauses in an otherwise normal heart rhythm. The pause develops from an abnormal focus of the ventricle, allowing the ventricle to be at a refractory (resting) period when the impulse for contraction arrives. The feeling of the heart skipping a beat is PVC; these increase with age and are associated with fatigue, emotional stress, and excessive use of coffee, alcohol, or tobacco.

Recognition of PVCs has significance in the client with CVD. If five or more PVCs are detected during a 60-second pulse examination, medical consultation is strongly recommended. Individuals who are distressed and have five or more detectable PVCs per minute may be undergoing an acute MI or ventricular fibrillation. To protect the client from health risks, do the following:

Ventricular Fibrillation

Ventricular fibrillation, one of the most lethal dysrhythmias, is characterized as an advanced stage of ventricular tachycardia with rapid impulse formation and irregular impulse transmission. The heart rate is rapid and disordered and contains no rhythm. Immediate medical treatment for ventricular fibrillation is the use of an AED (precordial shock) to halt the dysrhythmia, followed by CPR. Electric current at the time of shock depolarizes the entire myocardium, allowing the cardiac impulses to gain control of the heart rate and rhythm. This should reestablish cardiac regulation. The person then is placed on drug therapy to maintain regulation of cardiac rate and rhythm. Without immediate medical attention (advanced cardiac life support), blood pressure will fall to zero, resulting in unconsciousness; death may occur within 4 minutes.

Heart Block

Heart block is a dysrhythmia caused by the blocking of impulses from the atria to the ventricles at the AV node; it is an interference with the electrical impulses controlling the heart muscle. Each of the three forms of heart block is dangerous; however, third-degree heart block presents the greatest danger of cardiac arrest. The three forms are as follows:

First-degree heart block—usually associated with coronary artery disease or digitalis drug therapy. The individual usually is asymptomatic with a normal heart rate and rhythm.

First-degree heart block—usually associated with coronary artery disease or digitalis drug therapy. The individual usually is asymptomatic with a normal heart rate and rhythm.Medical Treatment

The cardiac pacemaker, an intracardiac device, is an electronic stimulator used to send electrical currents to the myocardium to control or maintain heart rate. Two types of pacemakers that control one or both of the heart chambers are as follows:

Temporary pacemaker—used in emergency situations to correct ventricular standstill or arrhythmias that are not responding to other forms of treatment.

Temporary pacemaker—used in emergency situations to correct ventricular standstill or arrhythmias that are not responding to other forms of treatment. Permanent pacemaker—inserted into the body; electrodes are transvenously placed in the endocardium and function for 5 to 10 years before battery replacement is necessary. Two general systems of cardiac pacing for the permanent pacemaker are as follows:

Permanent pacemaker—inserted into the body; electrodes are transvenously placed in the endocardium and function for 5 to 10 years before battery replacement is necessary. Two general systems of cardiac pacing for the permanent pacemaker are as follows:

Pacemakers vary in their sensitivity to electrical interference that may alter or cease their function. Newer models, bipolar and shielded to protect against interference, do not require any special consideration during dental hygiene care. The older unipolar pacemaker models are less protected from electrical interference and can be negatively affected by mechanized dental instruments and equipment. When in doubt, consult the client’s cardiologist.

Dental Hygiene Care

During assessment, the dental hygienist determines the type of pacemaker a client has and whether it is shielded from electrical interference. Dental devices that apply an electrical current directly to the client (e.g., ultrasonic scaling systems, electrodesensitizing equipment, pulp testers, power toothbrushes, and electrosurgery equipment) are likely to cause interference in unshielded pacemakers. Use of such equipment even in the proximity of the client with an unshielded pacemaker is contraindicated. Instead, nonelectrical alternatives to avoid functional interference are used (e.g., hand-activated instruments, tooth desensitization with a nonelectronic technique, and pulp testing performed by tooth percussion). Additional protection of the pacemaker can be accomplished by placing a lead apron on the client as a barrier to interrupt electrical interference generated by dental equipment such as the air-abrasive system, low- or high-speed handpiece, and computerized periodontal probe. Care should be taken in an open clinical setting where electrical dental equipment may be used for an adjacent client.

Prophylactic antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene care is required during the first 6 months after pacemaker implantation to prevent IE.

Care plan development for the individual with a cardiac pacemaker also can be affected by the drugs used to treat the underlying medical condition—anticoagulants and antihypertensive agents. Monitoring and assessment of drug therapy provide information necessary to modify treatment.

If the cardiac pacemaker fails or malfunctions during the dental hygiene appointment, the client may experience difficulty breathing; dizziness; a change in the pulse rate; swelling of the legs, ankles, arms, and wrists; and/or chest pain. When this situation arises, do the following:

Appointment Guidelines

Individuals wearing cardiac pacemakers may be susceptible to IE, and the unshielded pacemaker can be affected by electrical interference in the oral healthcare setting.

If necessary, recommend prophylactic antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene care to reduce risk of IE (see Chapter 10).

If necessary, recommend prophylactic antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene care to reduce risk of IE (see Chapter 10).Congestive Heart Failure

Congestive heart failure is a syndrome characterized by myocardial dysfunction that leads to diminished cardiac output or abnormal circulatory congestion. The weakened heart develops compensatory mechanisms to continue to function (i.e., tachycardia, ventricular dilation, and enlargement of the heart muscle).

CHF can occur as two independent failures (left-sided and right-sided heart failure); however, because the heart functions as a closed unit, both pumps need to be functioning properly or the heart’s efficiency is diminished.

Etiology

Causative factors associated with CHF are arteriosclerotic heart disease, hypertensive CVD, valvular heart disease, pericarditis, circulatory overload, and coronary heart disease. These factors contribute to the gradual failure of the heart by reducing the inflow of blood to the heart, increasing the inflow to the lungs, obstructing the outflow of blood from the heart, or damaging the heart muscle itself.

Disease Process

Clients who have left-sided heart failure have difficulty receiving oxygenated blood from the lungs, resulting in increased fluid and blood in the lungs, causing dyspnea on exertion, shortness of breath on lying supine, cough, and expectoration. These clients tend to require extra pillows to sleep and cannot be placed in a supine position.

Right-sided heart failure is associated with the blood return from the body, resulting in systemic venous congestion and peripheral edema. Clients with right-sided heart failure have feet and ankle edema and often complain of cold hands and feet.

Medical Treatment

CHF treatment is directly related to the removal of the cause. Usually the corrective therapy associated with the underlying disease eliminates the presence of CHF. Some patients require additional methods of rehabilitation, such as dietary control, reduced physical activity, and drug therapy (e.g., diuretics to reduce salt and water retention and digitalis to strengthen myocardial contractility).

Dental Hygiene Care

Individuals with CHF who are closely monitored by a physician do not require a change in conventional dental hygiene care; however, factors associated with the cause of CHF should be considered in the care plan. Alterations are based on the causative factors (e.g., hypertension, valvular heart disease, CHD, and MI) in association with the individual’s current medical status.

Clients taking digitalis are prone to nausea and vomiting during dental procedures. Therefore procedures that may promote gagging should be performed with extra care. In addition, the dental hygienist should be aware of any underlying heart conditions that are responsible for CHF. These conditions must be evaluated and appropriate precautions taken.

Alterations in the care plan for a client with left-sided CHF are related to the human needs for protection from health risks and for freedom from fear and stress. Client positioning needs to be upright to support breathing. Actions should be taken to minimize distress, and instructions should reinforce the need for a reduced-sodium diet to alleviate fluid retention.

If an emergency arises, medical assistance should be obtained. The client is usually conscious with difficulty breathing. Treat as follows:

Congenital Heart Disease

Congenital heart disease is an abnormality of the heart’s structure and function caused by abnormal or disordered heart development before birth. Commonly observed congenital heart malformations are ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, and patent ductus arteriosus.

Etiology

The cause of CHD is generally unknown; however, genetic and environmental factors have been attributed to poor intrauterine development. Genetic conditions, related to heredity, are apparent in some situations. Environmental factors are based on the health of the mother—for example, rubella (German measles) and drug addiction have produced delayed fetal development and growth retardation associated with the cardiovascular structure.

Disease Process and Medical Treatment

CHD is the result of various heart defects that dictate the disease process:

Ventricular Septal Defect

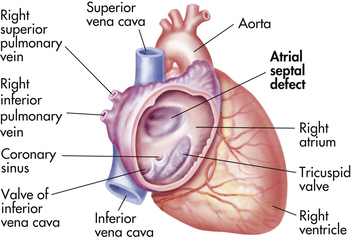

A ventricular septal defect—a shunt (opening) in the septum between the ventricles—allows oxygenated blood from the left ventricle to flow into the right ventricle (Figure 42-4). Small defects that close spontaneously or are correctable by surgery have a good prognosis. Larger defects that are left untreated or are irreparable usually result in death from secondary cardiovascular complications. The ventricular septal defect can be detected by a characteristic heart murmur audible at birth.

Figure 42-4 Ventricular septal defect.

(From Bleck E, Nagel D: Physically handicapped children: a medical atlas for teachers, ed 2, Needham Heights, Mass, 1982, Allyn and Bacon.)

Clinical manifestations vary with size of defect, infant age, and the effect of the deviated blood passage on the cardiovascular structure. Large ventricular septal defects cause hypertrophy of the ventricles, resulting in CHF.

Atrial Septal Defect

The atrial septal defect—a shunt (opening) between the left and right atria—is responsible for approximately 10% of congenital heart defects. The blood volume overload eventually causes the right atrium to enlarge and the right ventricle to dilate (Figure 42-5).

Figure 42-5 Atrial septal defect.

(From Bleck E, Nagel D: Physically handicapped children: a medical atlas for teachers, ed 2, Needham Heights, Mass, 1982, Allyn and Bacon.)

Usually the client is asymptomatic and the defect goes undetected; however, in adults, clinical symptoms become more pronounced. The client is easily fatigued and short of breath after mild exertion. Treatment includes cardiovascular repair surgery, observance of developing atrial arrhythmias, and monitoring of vital signs.

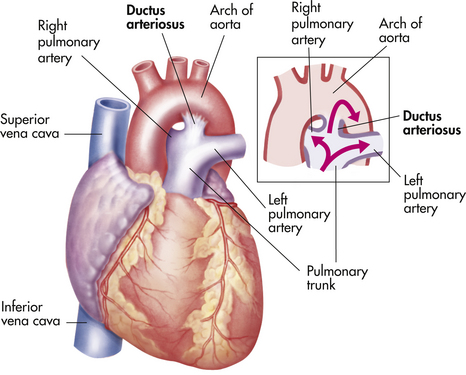

Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Patent ductus arteriosus is the most common congenital heart defect found in adults. During development the fetal heart contains a blood vessel called the ductus arteriosus. This vessel connects the pulmonary artery to the descending aorta. Normally after birth the vessel closes. If the vessel fails to close, a congenital heart defect forms. Failure to close is associated with premature births and therefore failure of the vessel’s contracture necessary for closure. Patent ductus arteriosus has been linked to rubella syndrome.

Shunting of blood in a patent ductus arteriosus defect is from the aorta to the pulmonary artery (Figure 42-6). This type of blood flow results in the recirculation of oxygenated blood through the lungs. Thus the left atrium and ventricle have an increased workload from increased pulmonary blood return, which can result in CHF. If the condition is left untreated, severe obstructive pulmonary vascular disease may develop.

Figure 42-6 Patent ductus arteriosus defect.

(From Bleck E, Nagel D: Physically handicapped children: a medical atlas for teachers, ed 2, Needham Heights, Mass, 1982, Allyn and Bacon.)

Clinical manifestations include respiratory distress, susceptibility to respiratory tract infections, and slow motor development. Treatment consists of surgical correction and elimination of symptoms associated with secondary complications.

Tetralogy of Fallot

Tetralogy of Fallot is a rare and complex congenital heart defect generally associated with cyanosis. The defect is composed of four congenital abnormalities: ventricular septal defect, pulmonary stenosis, right ventricular hypertrophy, and malposition of the aorta. The blood shunts right to left through the ventricular septal defect, permitting unoxygenated blood to mix with oxygenated blood, resulting in cyanosis. Treatment includes measures to relieve cyanosis and palliative and corrective surgery.

Dental Hygiene Care

The individual with CHD does not require extensive alterations in care. However, the American Heart Association recommends antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene procedures to prevent IE in persons with repaired CHD with residual defects, with unrepaired cyanotic CHD including palliative shunts, and during the first 6 months after surgery to correct congenital defects. Secondary concerns focus on the management of cardiovascular complications, such as CHF and cardiac dysrhythmias, resulting from the congenital defect.

Dental hygiene care includes physician consultation to confirm drug usage and current medical status, prophylactic antibiotic medication to prevent IE, and assessment of symptoms secondary to the disease that may require treatment alteration. If the individual develops CHF, then care plan considerations should follow those outlined.

CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Open-heart surgery is necessary for complex procedures that need direct visualization of the heart while being performed (e.g., heart transplants, heart valve replacements, and coronary bypass surgery). Open-heart surgery is always performed with the use of a heart-lung machine that completely controls cardiopulmonary function, enabling surgeons to operate for long periods without interfering with the individual’s metabolic needs. Closed-heart surgery is usually associated with cardiac catheterization.

Types of Cardiovascular Surgery

Angioplasty

The most common type of closed-heart surgery, angioplasty involves the use of a catheter (a long, slender tube) with a tiny balloon at the end that is inserted into the coronary artery. Specifically, the balloon is inserted into places where the artery narrows, is inflated to flatten fatty deposits, and is deflated to allow the increased blood flow to compress and redistribute the atherosclerotic lesion. This procedure is used in individuals who have a small atherosclerotic lesion constricting blood flow. If the lesion cannot be corrected by the angioplasty procedure, bypass surgery may be necessary.

Coronary Bypass Surgery

Coronary bypass surgery, a common procedure to replace blocked arteries, is performed by removing part of the leg vein or chest artery and then grafting it onto the coronary artery, thereby creating a new passageway for the blood. This type of surgery can be done for more than one artery at a time and is named accordingly (double-bypass, triple-bypass). The benefits of coronary bypass surgery include relief from angina, increased tolerance to exercise, improved quality of life, and extended life span. A person who has had bypass surgery has no contraindications to dental hygiene therapy.

Valvular Defect Repair

Valvular defect repair or replacement is performed frequently. Persons with artificial cardiac valves are at high risk for infections and IE and must be premedicated with an antibiotic before dental hygiene care (see Box 42-1 and Chapter 10Box 10-4Box 10-5Table 10-4Table 10-5Table 10-6).

Heart Transplantation

Heart transplantation is a viable option for individuals with end-stage heart disease in which no other therapeutic intervention is considered effective. Although many hospitals perform cardiac transplantation, the dilemma is finding donors.

Future goals and implications of heart transplantation include the development of a safe, reliable, permanent, totally implantable artificial heart device that allows a recipient to carry out normal activities. The development of such a device may increase availability of this life-saving procedure for eligible recipients who at this time await donors.

Dental Hygiene Care

Client Who Has Had Closed-Heart Surgery

No contraindications are associated with dental or dental hygiene treatment unless the individual is taking anticoagulant medication. As in all cardiac-associated situations, consultation with the client’s cardiologist is recommended.

Client after Open-Heart Surgery

No dental hygiene procedures relate uniquely to the individual who has had cardiovascular surgery. When in doubt, the cardiologist is consulted; however, prosthetic valvular heart replacements and those cardiac surgeries that make the client susceptible to infection require prophylactic antibiotic premedication (see Chapter 10Table 10-5Table 10-6).

Complications from dental hygiene care observed in clients who have had cardiovascular surgery are associated with the drug therapy used rather than the surgery itself. Most postsurgical clients are placed on medication to increase healing, suppress immune response, reduce infection, and/or decrease clot formation. Careful evaluation of drug contraindications and reactions is necessary.

Client Who Has Had a Heart Transplant

A major concern of the heart transplant patient is infection and transplant rejection. Before care, consultation with the client’s cardiologist is highly recommended to determine if additional premedication is indicated. Most transplant patients are on long-term preventive antibiotic therapy to control systemic bacteremias. They are also placed on immunosuppressant medications such as cyclosporine (Sandimmune) to reduce the possibility of rejection.

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS OF CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICATIONS (SEE CHAPTER 12 AND TABLE 42-2)

Some medications used in CVD therapy have a profound effect on the oral cavity. These medications typically include those that treat hypertension, heart transplant stabilization, and CHD. Persons taking cardiovascular medications should seek regular dental hygiene care and maintain excellent oral biofilm control to balance their increased vulnerability to dental and periodontal diseases.

Most medications for the treatment of hypertension cause xerostomia, increasing the individual’s risk for dental caries and periodontal disease. Individuals with exposed root surfaces are at risk for root surface caries and dentinal hypersensitivity. Self-administered fluoride therapy, ACP therapy, and use of saliva substitutes and xylitol products should be part of the individual’s daily self-care regimen to meet the client’s needs (see Chapter 31). Some calcium channel blockers alter taste perception, cause drug-influenced gingival enlargement, and create salivary gland pain. Immunosuppressants used for the stabilization of heart transplants increase the individual’s risk for developing periodontal disease or may exaggerate a pre-existing condition, leading to an unmet need in skin and mucous membrane integrity.

Another dental hygiene diagnosis to consider is a need for protection from health risks because immunosuppressants increase risk for developing opportunistic infections such as candidiasis, herpes simplex, herpes zoster, necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, and drug-influenced gingival enlargement. In addition to regular professional dental hygiene care, these individuals should use an antimicrobial mouth rinse for 30 seconds twice daily as part of their self-care regimen to reduce oral disease risk.

Persons with a history of heart attack or cerebrovascular accident are placed on blood thinners (anticoagulants) to increase blood flow. The side effects are prolonged bleeding and spontaneous oral bleeding in the presence of infection. These individuals must maintain a healthy periodontium to reduce the risk of periodontal disease.

PREVENTING AND MANAGING CARDIAC EMERGENCIES

The individual with a CVD or cardiovascular symptom or defect is considered high risk—one whose life may be threatened by daily activities. These clients have a need for protection from health risks because of their increased potential for an emergency. The most common physical pain encountered is chest pain accompanied by difficulty breathing. If the client complains of physical pain that cannot be alleviated, EMS should be activated or 911 called.

For individuals with angina pectoris, hypertension, previous MI, and CHF, the risk for life-threatening medical emergencies rises as a result of an increase in fear and stress.

Assessing past responses in oral healthcare situations and monitoring the client’s reactions to dental hygiene procedures are important. Muscular tenseness, perspiration, and verbal cues indicate a potential emergency, and the client’s need for protection from health risks must be met.

Individuals with CVD may not take responsibility for their oral health. Understandably, these individuals fail to relate their life-threatening medical condition with oral disease; however, by increasing a client’s awareness that periodontal disease and the systemic condition are linked, the dental hygienist might change the client’s value system and oral health behavior and improve systemic health. Accurate assessment of the client’s personal beliefs, behaviors, and values can identify motivators (needs) that may lead to the client’s commitment to therapeutic goals and priorities. Table 42-3 illustrates sample dental hygiene diagnoses for a client with coronary heart disease.

TABLE 42-3 Sample Dental Hygiene Diagnoses—Client with Coronary Heart Disease

| Dental Hygiene Diagnosis | Related to | As Evidenced by |

|---|---|---|

| Responsibility for oral health | Low value ascribed to oral health | Lack of interest in performing daily oral self-care |

| Potential for health risks: potential for infection | History of infective endocarditis | Condition indicated on health history questionnaire |

| Biologically sound and functional dentition | Drug therapy (diuretics) taken by client | |

| Biologically sound and functional dentition (nutrition) | Dietary restrictions of cholesterol, saturated fat, and sodium | Obesity, high LDL cholesterol blood values |

Planning prevents emergencies and ensures that client needs are the focus of therapeutic interventions. When a care plan is developed, attention is given to drug therapies to ensure that no contraindications are present and that side effects are identified (see Table 42-2). Tables 42-4 and 42-5 can be used when developing care plans for clients with a CVD.

TABLE 42-4 Quick Reference—Signs, Symptoms, and Treatment of Individuals with Cardiovascular Disease

| Disease | Signs and Symptoms | Medical and Surgical Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Rheumatic heart disease | Carditis, polyarthritis, chorea, erythema marginatum, subcutaneous nodules, fever | Bedrest and medications associated with manifestations |

| Infective endocarditis | Initial high fever, cardiac decompensation, heart murmur | Antibiotic therapy |

| Valvular heart defects | ||

| Mitral valve prolapse | Palpitations, chest pain, nervousness, shortness of breath, dizziness | Treatment is not always necessary; aimed at alleviating symptoms |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias and arrhythmias | Antiarrhythmic drug therapy or cardiac pacemaker | |

| Hypertension | Headache, fatigue, diminished exercise tolerance, shortness of breath | Antihypertension drug therapy; dietary control of sodium |

| Coronary (ischemic) heart disease | Angina pectoris, discomfort in jaw, neck, throat, interscapular area, and left arm | Bedrest; administration of nitroglycerin |

| Congestive heart failure | Fatigue, weakness, dyspnea, cough, anorexia | Treatment directed at the underlying cause |

| Congenital heart disease | Dependent on type of defect | Surgery to correct defect |

TABLE 42-5 Quick Reference—Dental Hygiene Care Implications for Individuals with Cardiovascular Disease

| Disease | Implications for Dental Hygiene Care | Dental Hygiene Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Rheumatic heart disease | Special attention to oral self-care practices; self-inflicted bacteremias may occur when oral disease is present. | Careful manipulation of soft tissues during instrumentation; ADA-accepted antibacterial mouth rinse to reduce transient bacteremia. |

| Infective endocarditis | Careful manipulation of soft tissue; antibacterial mouth rinse to reduce transient bacteremia. | |

| Valvular heart defects | If anticoagulant medication is being used and scaling procedures are planned, dosage of anticoagulant medication should be discussed with client’s cardiologist. | |

| Mitral valve prolapse | Special attention to oral self-care practices because self-inflicted bacteremias may occur when oral disease is present. | Careful manipulation of soft tissues during instrumentation to reduce transient bacteremia. |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias and arrhythmias | Electrical interference can cause unshielded pacemaker to malfunction. | Use of electrical dental equipment is contraindicated. |

| Hypertension | Stress and anxiety about treatment may increase blood pressure. | Use stress reduction strategies; if blood pressure is uncontrolled, dental hygiene care is contraindicated. |

| Coronary (ischemic) heart disease | Stress and anxiety about treatment may precipitate angina. | |

| Congestive heart failure | None if person is under appropriate medical care. | Keep client in upright position to decrease lung fluid. |

Implementation of care takes into consideration the possibility of a medical emergency (see Chapter 8). The most life-threatening emergency situation is cardiac arrest. In an emergency, do the following:

Other medical emergencies associated with CVD are attacks of angina pectoris and MI. Box 42-3 lists actions to be taken.

BOX 42-3 Basic Steps in a Cardiac Emergency Situation

Make certain client is comfortable; loosen restricting garments, elevate head slightly, provide reassurance.

Angina Pectoris

Myocardial Infarction

∗ Note: An overdose of nitroglycerin can cause headache.

Oral care professionals evaluate the current health status of the client in light of the established client goals. By reviewing assessment data, dental hygiene diagnoses, care plan, and interventions used, one can determine where less-than-desirable outcomes occurred and modify care as necessary. Table 42-6 illustrates an evaluation of dental hygiene interventions for the care plan in Box 42-1.

TABLE 42-6 Sample Evaluation of Dental Hygiene Interventions

| Client Goals | Evaluation Measures | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Complete invasive dental hygiene therapy (scaling and root debridement) so that antibiotic coverage occurs with a 9- to 14-day interval between coverage | Appointments scheduled 9-14 days apart | |

| By 9/09, reduce gingival bleeding by 90% | Document clinical outcomes using bleeding on probing | Minimal to no gingival bleeding on probing |

| By 12/09, reduce periodontal probing depths | Document clinical outcomes using periodontal probing depths and clinical attachment levels |

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Explain that prophylactic antibiotic premedication must be taken 1 hour before the scheduled appointment to achieve optimal blood levels and reduce possibility of infective endocarditis (IE) in persons with the highest categories of risk for IE (see Chapter 10, Table 10-5).

Explain that prophylactic antibiotic premedication must be taken 1 hour before the scheduled appointment to achieve optimal blood levels and reduce possibility of infective endocarditis (IE) in persons with the highest categories of risk for IE (see Chapter 10, Table 10-5). Explain that oral health maintenance reduces self-induced and professionally induced transient bacteremias (prevention of IE).

Explain that oral health maintenance reduces self-induced and professionally induced transient bacteremias (prevention of IE). Explain that reducing gingival inflammation and oral biofilm is important when taking anticoagulant medication.

Explain that reducing gingival inflammation and oral biofilm is important when taking anticoagulant medication. Explain that periodontal disease increases one’s risk for coronary heart disease because it contributes to the development of blood clots and atheromas in blood vessels—that is, formation of blood clots and atheromas is enhanced by the presence of specific periodontal pathogens in chronic inflammation.

Explain that periodontal disease increases one’s risk for coronary heart disease because it contributes to the development of blood clots and atheromas in blood vessels—that is, formation of blood clots and atheromas is enhanced by the presence of specific periodontal pathogens in chronic inflammation.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

The client with cardiovascular disease (CVD) poses a malpractice risk if treatment procedures fail to follow the standard of care. Legal issues as a result of a medical emergency include the following10:

The client with cardiovascular disease (CVD) poses a malpractice risk if treatment procedures fail to follow the standard of care. Legal issues as a result of a medical emergency include the following10: The original “incident” may subject the practitioner to liability for causing additional harm (even death) resulting from (1) later negligent care and treatment addressed of the original injury, (2) later care and treatment (not negligent), or (3) later care and treatment when an inherent risk (e.g., infection) is the aftermath.

The original “incident” may subject the practitioner to liability for causing additional harm (even death) resulting from (1) later negligent care and treatment addressed of the original injury, (2) later care and treatment (not negligent), or (3) later care and treatment when an inherent risk (e.g., infection) is the aftermath. If a client with CVD develops chest pain and begins to feel nauseous and sweat profusely, the provider should (1) stop dental hygiene care; (2) alert the dentist; and (3) together with the dentist manage the immediate emergency situation, which may include use of the automated external defibrillator and Basic Life Support.

If a client with CVD develops chest pain and begins to feel nauseous and sweat profusely, the provider should (1) stop dental hygiene care; (2) alert the dentist; and (3) together with the dentist manage the immediate emergency situation, which may include use of the automated external defibrillator and Basic Life Support. If dental hygiene care is continued and the client experiences a myocardial infarction, liability charges may be brought against the practitioner.

If dental hygiene care is continued and the client experiences a myocardial infarction, liability charges may be brought against the practitioner. If dental care is performed on a client who was not appropriately assessed and his or her status is not documented on an acceptable health history form, the practitioner could be held responsible for any damage resulting from care.

If dental care is performed on a client who was not appropriately assessed and his or her status is not documented on an acceptable health history form, the practitioner could be held responsible for any damage resulting from care.KEY CONCEPTS

Review health history, dental history, cultural history, pharmacologic history, and risk factors for systemic and oral disease as a standard of care; consult with client’s physician or cardiologist as required.

Review health history, dental history, cultural history, pharmacologic history, and risk factors for systemic and oral disease as a standard of care; consult with client’s physician or cardiologist as required. Periodontal disease may increase one’s risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) (e.g., the inflammatory process increases risk for thrombosis development).

Periodontal disease may increase one’s risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) (e.g., the inflammatory process increases risk for thrombosis development). The practitioner must follow the Prevention of Infective Endocarditis guidelines from the American Heart Association and strive to maintain the oral health of clients with cardiovascular disease.

The practitioner must follow the Prevention of Infective Endocarditis guidelines from the American Heart Association and strive to maintain the oral health of clients with cardiovascular disease. Unstable angina pectoris indicates that a client has increasing chest pain at rest and during sleep. Clients with unstable angina are at risk for a possible medical emergency and should not be treated.

Unstable angina pectoris indicates that a client has increasing chest pain at rest and during sleep. Clients with unstable angina are at risk for a possible medical emergency and should not be treated. The drug of choice for a client experiencing angina is nitroglycerin, usually administered sublingually. Too much nitroglycerin can cause headache.

The drug of choice for a client experiencing angina is nitroglycerin, usually administered sublingually. Too much nitroglycerin can cause headache. Dental hygiene care should be postponed if a client has had a myocardial infarction within 6 months of the scheduled appointment.

Dental hygiene care should be postponed if a client has had a myocardial infarction within 6 months of the scheduled appointment. Cardiac dysrhythmias and arrhythmias are dysfunctions of the heart rate and rhythm and may be detected when assessing the client’s pulse rate.

Cardiac dysrhythmias and arrhythmias are dysfunctions of the heart rate and rhythm and may be detected when assessing the client’s pulse rate. Unshielded cardiac pacemakers may be susceptible to interference generated by some dental equipment (e.g., ultrasonic scalers, pulp testers, electrodesensitizing equipment, air-abrasion systems, computerized periodontal probes, low- or high-speed handpieces).

Unshielded cardiac pacemakers may be susceptible to interference generated by some dental equipment (e.g., ultrasonic scalers, pulp testers, electrodesensitizing equipment, air-abrasion systems, computerized periodontal probes, low- or high-speed handpieces). Clients with a history of CVD can be given local anesthetic agents that contain epinephrine at the minimally safe dose.

Clients with a history of CVD can be given local anesthetic agents that contain epinephrine at the minimally safe dose. Anticoagulant medications increase bleeding time. Clients taking such medications need a medical consultation and prothrombin time values within the range of normal before dental hygiene care is performed.

Anticoagulant medications increase bleeding time. Clients taking such medications need a medical consultation and prothrombin time values within the range of normal before dental hygiene care is performed.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Case 1: Client with History of MI on Anticoagulant Therapy

During assessment, the client reports that he had an MI 2 years ago and is taking Coumadin twice daily. The client has type II periodontal disease.

Case 2: Documentation of Health History—Client with Coronary Heart Disease

Medical Profile: Mrs. J, age 56, was last examined by her physician in September. On completion of the health history, you note that Mrs. J has responded “yes” to some questions concerning coronary heart disease, experiences chest pain, and carries nitroglycerin. Although the nitroglycerin usually helps, she sometimes needs to take two doses.

1. World Health Organization (WHO): World health statistics: annual report, Washington, DC, 2006, WHO.

2. Mattila K.J., Pussinen P.J., Paju S. Dental infections and cardiovascular diseases: a review. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2085.

3. Rufail M.L., Schenkein H.A., Koertge T.E., et al. Atherogenic lipoprotein parameters in patients with aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2007;42:495.