Chapter 28 Trauma to the Sole and Wall

Problems Associated with Horseshoe Nails

Nail Bind

History and Clinical Signs

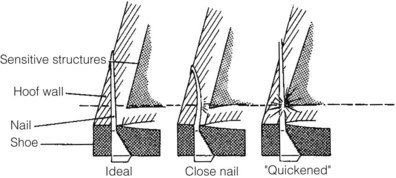

A close nail or nail bind refers to placement of a horseshoe nail not necessarily in the sensitive structures of the hoof, but close enough that the nail exerts sufficient pressure on these structures to cause discomfort. A horseshoe nail is designed to be driven obliquely through the hoof wall. When the nail is driven, the tip is placed at the inner edge of the white line with the bevel of the nail tip facing inward. When driven, the bevel contacts the hard hoof wall and curves outward and exits 1 to 2 cm above the level of the shoe. The tip of the nail is removed and the remainder is bent over to form a clinch to hold the shoe firmly to the hoof. Correct nail placement is important because if the nail is placed too shallow (superficial), the hoof wall will weaken and possibly split; if is it placed in too far, the sensitive structures of the hoof may be entered (pricked) (Figure 28-1). Overzealous clinching of the nails causes inward bending of the nail that can result in pressure on sensitive tissues, which may result in immediate or delayed pain and lameness. Slight displacement of a shoe also can result in nail pressure on sensitive tissues.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of nail bind is difficult and often determined by eliminating other causes of foot pain. Lameness varies from subtle to severe. Sometimes a horse exhibits a change or lack in performance. The problem may not arise until several days after shoeing. Sometimes a horse is sound when trotted in a straight line, but it shows lameness when pulled in a tight circle or when it makes a turn. It is important to realize that nail bind is not always associated with poor farriery. A good nail can become a problem nail days or weeks after shoeing if the shoe shifts, causing abnormal nail pressure, or if the horse had a poor-quality hoof wall and hoof wall loss occurs. This is a common problem in Thoroughbred (TB) racehorses and usually involves the medial heel nail (the medial quarter and heel wall usually is the thinnest aspect of the hoof wall). Hoof tester evaluation using both pressure and percussion on the outer hoof wall capsule may cause a painful response over the offending nail. Heat and increased digital pulse amplitudes may not be present, depending on the duration of the close nail. Often diagnosis is determined by pulling single nails one by one from the shoe and evaluating the horse for lameness after each nail is removed. Paradoxically, lameness is sometimes transiently accentuated after removal of the offending nail.

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of nail bind is removal of the offending nail; usually lameness resolves within a few days. The empty nail hole may be flushed with a disinfectant solution, such as dilute povidone-iodine solution, dimethyl sulfoxide, or an antiseptic solution such as thimerosal (Merthiolate, Eli Lilly, Chicago, United States). No additional treatment is usually needed. Prognosis is good once the nail has been removed, provided infection does not ensue.

Nail Prick

History and Clinical Signs

Nail prick or quicking refers to penetration of the sensitive hoof structures, usually the sensitive laminae, by a driven horseshoe nail (see Figure 28-1). The horse usually reacts as the farrier drives or clinches the nail by jerking the foot from the farrier.1 Sometimes blood appears on the nail or leaks from the nail hole. Nail pricks occur for many reasons and are not always caused by a misdirected nail. Poorly made shoes, misdirected nails, selection of a nail that is too large, poorly placed nail holes, and faulty nails can result in a nail prick. Horses with poor hoof quality, thin hoof walls, or flaring hoof walls can be very difficult to nail and thus are at greatest risk. Fractious horses and young horses that have not been previously shod may lean on the farrier or repeatedly pull the foot from the farrier, making driving a nail difficult. A rushed farrier predisposes to nail pricking, but it can also happen to the best of farriers. Damage from an improperly driven nail can vary from minimal to serious infection.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a misdirected nail warrants great diplomacy from the veterinarian, because many owners become unjustifiably upset with the farrier. Some horses repeatedly stomp the affected foot or paw the ground immediately after shoeing. Others point the affected limb after shoeing. Lameness may not be apparent immediately but may occur days after shoeing when the nail hole becomes infected and the trapped pus begins to exert pressure. The horse usually becomes acutely lame, and the lameness worsens over time unless it is treated. An infection may migrate up the lamellae (white line) and create an abscess or soft spot at the hairline of the coronary band. The abscess is directly aligned with the hoof wall tubules leading to the infected nail hole, which is an important diagnostic aid. Hoof tester examination, using both pressure and percussion over each nail, is essential to locate the offending nail. Increased digital pulse amplitudes and heat may be present.

Treatment

Pricks from nails can be potentially serious and require immediate treatment. If the nail prick is discovered by the farrier at the time of shoeing, the nail is removed. The nail should be examined for moisture or blood. The nail hole can be irrigated with dimethyl sulfoxide, povidone-iodine solution, or hydrogen peroxide. The nail hole is packed with iodine-soaked cotton and left open. Often the nail is redirected and no further treatment is needed. Tetanus prophylaxis is essential for an unvaccinated horse.

If the offending nail cannot be localized or the nail hole is infected, the shoe is removed. Hoof testers then are used to localize the painful nail hole. Many times the pressure from the hoof testers causes black, malodorous liquid exudate to exit from the hole. This may not be obvious immediately, but if the foot is replaced to the ground and the horse walks a few steps, exudate may become obvious. The basis of treatment is to establish drainage. The infected nail hole often requires enlargement with a loop hoof knife or curette. Ideally a cone-shaped hole is made, with the larger opening at the bottom of the hoof. The hole is irrigated or the entire foot is soaked in an Epsom salt and povidone-iodine foot bath for 20 to 30 minutes twice daily until the infection is resolved. It is important to protect the foot from the environment (mud, dirt) by keeping the foot bandaged between foot soaks. Alternatively, a poultice can be applied to the foot for several days. Additional medications usually are not necessary unless infection is widespread. Antiinflammatory medication may be beneficial to decrease pain. Once the infection has cleared, the shoe is replaced. The affected nail hole can be packed with iodine-soaked cotton, and the horse reshod with a plastic pad covering the sole. Alternately, a hole can be drilled into the shoe over the affected nail hole and the shoe can be replaced, leaving access to the infected area for daily irrigation and povidone-iodine packing.

Prognosis

Prognosis after nail prick usually is good, provided that minimal damage occurs to vital structures of the foot. Establishing drainage for infection is important to avoid potential complications, such as infectious osteitis of the distal phalanx or infection of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint.

Solar Bruising

History and Etiology

A bruise is a contusion or impact injury that causes focal or generalized damage with subsequent hemorrhage of the solar corium. Sole bruising occurs commonly in all types and breeds of horses, especially in racing TBs and Standardbreds (STBs).2 The degree and severity of lameness vary from acute, severe lameness to chronic mild or intermittent pain, depending on location and degree of damage. It is important to determine the cause of the bruise, because this dictates proper treatment and prevention. The general cause is abnormal focal weight bearing on the solar surface of the foot. The location of the bruise is helpful in determining the cause of the injury. The most common location is the junction between the bars and the walls at the heel, termed a corn.3 Corns occur most frequently on the medial side of the front feet. Heel bruising may be the result of improper shoeing or trimming. Some farriers bend the medial branch of the shoe toward the frog to prevent the horse from stepping on and pulling the shoe. This shoe position causes direct pressure to the sole at the heel angle, instead of the heel wall, resulting in continued concussion and bruising. A shoe that is too small or does not extend far enough back under the heel can lead to heel bruising.4 The ends of the shoe should extend to the widest aspect of the frog for proper heel protection. Horses with long-toe–low-heel hoof conformation are susceptible to heel bruising. Toe bruising can be caused by excessive impact or weight bearing on the toe region secondary to another cause such as heel pain. An improperly positioned horseshoe that rests on the sole instead of the hoof wall also causes toe bruising. Horses with long toes and those shod with toe grabs concentrate impact at the toe region.4 Sole bruising occurs often in horses with flat feet because the sole repeatedly strikes the ground surface. A flat foot can be congenital, can be created by trimming the hoof wall too short, or can be caused by excessive wall breakage at the quarters. Thin-soled horses or excessive trimming of the sole reduce the sole protection and predispose to sole bruising. Loose shoes can shift position, and improperly balanced feet cause excessive impact forces to specific regions of the foot and cause bruising.4 Riding on hard and rocky ground can result in stone bruises. A shod foot that has overgrown to the point where the shoe is riding on the sole is at risk of bruising.4

Clinical Signs

The degree of lameness from sole bruising can change daily, and lameness varies among horses. Removal of the shoe usually increases the degree of lameness. The bruising can be acute or chronic depending on the cause. Digital pulse amplitudes are increased after exercise, and careful hoof tester evaluation often reveals a focal painful response. Discoloration is common, but if the bruise is chronic or deep or if the horse’s sole is pigmented, it may be difficult to identify. Bruising often affects several feet. In most horses, lameness will improve after perineural analgesia of the palmar digital nerves. Radiological changes are rare but may include a serum pocket (fluid line) between the distal phalanx and external sole abscess. Such lesions are easier to detect with digital or computed radiography than with conventional radiography. Persistent, chronic bruising may lead to osteolytic lesions or solar margin fractures of the distal phalanx.

Treatment

Initial treatment with phenylbutazone (2.2 mg/kg bid) and soaking the feet in Epsom salts help decrease inflammation. Corrective or proper shoeing is imperative to shift the weight-bearing forces away from the damaged area of the foot. Sole paint consisting of a combination of equal parts of phenol, iodine, and formalin can be applied to toughen the solar surface. Hoof balance problems and shoeing causes, such as heel calks, toe grabs, or tucked heels, should be eliminated. One of many different shoeing techniques then is used to decrease impact and protect the bruised area. One method is use of a rim pad that is cut out over the bruised area so that the affected heel or quarter is “floated” and thus receives minimal weight-bearing forces. Another method is application of a bar shoe with a deeply concaved solar (inner) surface to stabilize the foot and alleviate any sole pressure from the shoe itself. A wide-web shoe may provide relief by covering and providing protection over a larger surface. It is important that this shoe be properly positioned on the hoof wall so that it does not increase sole pressure. Application of full pads packed with silicone or oakum may provide temporary relief by distributing weight-bearing forces over a wider area but often leads to a weakened and softer sole, causing recurrent problems.5

Thrush

Thrush is a bacterial infection characterized by an accumulation of black, malodorous, necrotic material, usually originating within the central or collateral sulci of the frog of the hoof. This degenerative condition may spread to involve deeper structures of the foot, such as the digital cushion, hoof wall, and heel bulb region, causing inflammation and breakdown of these structures.6 Many keratolytic organisms may be present, but Fusobacterium necrophorum is often isolated. Thrush is most often caused by poor environmental conditions; horses standing in soiled stalls, deep mud, swampy land, or wet pastures are at risk, especially if the feet are not cleaned daily.7 Poor hoof conformation also predisposes to thrush. Saddlebreds, Tennessee Walkers and other gaited horses, and some Warmblood breeds have long feet with naturally deep frog sulci and are at risk of thrush.7 Horses with a sheared heel or acquired frog deformity also are predisposed. Horses shod with full pads may develop thrush secondary to moisture and dirt collection under the pad. Other well-kept, clean horses can develop thrush for no apparent reason. Horses with severe thrush need to be differentiated from those with canker (see Chapter 125 and page 319). Lameness in horses with mild thrush is often blamed on the presence of thrush, but a careful lameness examination will reveal a primary source of pain elsewhere, coexistent with mild thrush.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

Lameness often is not apparent, but if present, the severity can vary. With severe thrush lameness can be obvious, but in most horses thrush is an additional finding and the primary source of pain is elsewhere. Diagnosis is based on the presence of black, malodorous discharge located most commonly within the frog sulci. The central frog sulcus often is malformed and very deep. A painful response may occur when the affected sulci are cleaned, because the degenerative process may extend to sensitive structures of the foot. If structural damage has occurred, the bulbs of the heel may move independently of each other, causing pain on manipulation.

Treatment

The predisposing cause should be identified and, if possible, removed. The horse should be moved to a clean, dry environment, and the feet should be cleaned daily. Any necrotic debris and undermined tissue are carefully debrided and cleaned using a hoof knife. Foot bandages may be necessary if the debridement is extensive. Systemic antimicrobial drugs may be necessary if deep or more proximal tissues are affected, but infection is usually managed by topical medication. Several caustic materials have been recommended, including a combination of phenol, tincture of iodine, and 10% formalin, Kopertox solution (Fort Dodge, Fort Dodge, Iowa, United States), or methylene blue. Initially, when the frog is very sensitive, the caustic materials may be too harsh and actually cause more tissue damage. We recommend to begin treatment by trying to dry the sensitive tissue with a mixture of sugar and povidone-iodine solution; make a paste consistency and apply that over the affected area until the tissue is dry and less sensitive. Once the frog begins to harden and keratinize, then the more caustic materials can be used. Others have recommended foot soaks in chlorine bleach (30 mL of bleach in 5 L of water). Corrective trimming and farriery may be necessary. If heel instability is present, a bar shoe may be necessary to stabilize the palmar aspect of the foot. Exercise is important to strengthen the palmar aspect of the foot and will naturally clean the feet.7 The best treatment for thrush involves prevention by educating the client on proper hoof hygiene.

Sheared Heel

History and Clinical Signs

Sheared heel refers to instability between the medial and lateral bulbs of the heel. Mediolateral foot imbalance may be a predisposing cause. It is frequently but not invariably associated with distortion of the hoof capsule. The medial bulb of heel often is displaced proximally, with a steep medial wall and flaring of the lateral wall (see Figure 6-3). However, instability between the bulbs of the heel can also occur in a more normally conformed foot, and distortion of the hoof capsule as previously described is not synonymous with sheared heel. It is also important to recognize that sheared heel can be present without causing lameness, although sheared heel may be a cause of lameness.

Sheared heel may be present in one or several feet and may be associated with mild to moderate lameness. Lameness is usually worst on firm or hard footing. There may be distortion of the coronary band, which usually is higher medially. There may be a deep cleft dissecting between the medial and lateral bulbs of the heel. Sheared heel may predispose to thrush.

Diagnosis

Instability of the bulbs of the heel is detected by grasping each bulb of the heel with the left and right hands and twisting each bulb in opposite directions in a shearing motion. In a normal horse the bulbs of the heel cannot be moved independently. Considerable independent motion can be associated with pain, causing lameness. However, if the lameness is severe, another coexisting cause of lameness should be considered. Lameness associated with sheared heel is removed by perineural analgesia of the palmar digital nerves.

Treatment and Prognosis

Any mediolateral or dorsopalmar foot imbalance should be corrected. The affected foot should be floated by trimming the high heel bulb shorter than the rest of the hoof wall such that it does not bear any weight. This allows the coronary band to drop down into the correct position. The foot with the floated heel bulb should be shod with a bar shoe to provide stability to the heel region. This may need to be continued for many months, and occasionally indefinitely, until some physical attachment between the heel bulbs has become established. If the hoof capsule is distorted in shape as previously described, the medial branch of the shoe should be set slightly wide to encourage the medial wall to grow down to it and prevent it from collapsing axially. Any excess flare on the lateral wall should be removed. The prognosis is generally good.

Hoof Wall Separation (White Line Disease, Seedy Toe)

History and Clinical Signs

The white line, visible at the sole, is created by the junction of the insensitive laminae of the hoof wall and the horn of the sole. White line disease has historically been a term to describe the separation of the hoof wall from its laminar attachments. A crack or opening occurs within the white line, allowing a bacterial or fungal infection to invade the stratum medium, with proximity to the laminae causing cavities to develop between the laminae and outer hoof wall.8 Environmental conditions of either too much moisture (continuous wet pastures) or drought conditions producing excessively dry feet predispose to development of a crack or opening in the white line. Horses with poor-quality hoof walls that split or crack or those with chronic laminitis and a thickened or stretched white line in the toe region may develop white line disease. The term seedy toe has been used differently in North America and Europe. In North America it is most often used to describe thickened or widened white line at the toe in horses with chronic laminitis, whereas in Europe it is used to describe separation at the white line, filled with crumbly material, that is not associated with laminitis. The hoof wall separation usually is a chronic condition beginning weeks or months before veterinary advice is sought, because there usually is no associated lameness. Hard ground may exacerbate any lameness seen.

Diagnosis

The degree of lameness varies, but if severe, white line disease can cause clinical signs of pain. However, the clinician should resist the temptation to incriminate this disease as the primary source of lameness until a thorough lameness examination has been completed. Because lameness is abolished after palmar digital analgesia or a dorsally directed ring block, this disease can easily be confused with many other conditions of the foot. Visual examination of the white line, assisted by a probing instrument, reveals a cavity with separation of outer hoof wall from the laminae. Radiological evaluation determines the full extent of hoof wall separation. Often the cavity is either dry or filled with necrotic debris, which may involve a bacterial or fungal infection. The cavity is usually not painful to probing.

Treatment

If the cavity is small (extends <2 cm proximally), placement of a cotton ball soaked in tincture of iodine in the cavity, with the shoe keeping the cotton in place, may be enough to stop the progression of the problem. However, if the cavity is extensive, then the separated outer hoof wall is removed using hoof nippers, hoof knife, and motorized tools. The aim is to remove cracks or crevices that could harbor bacteria. A Dremel tool burr (Dremel, Racine, Wisconsin, United States) is useful to smooth any cracks in the insensitive laminae that are exposed after hoof wall removal. Large defects in the hoof wall require protection. A heart bar shoe redistributes weight-bearing forces to the frog and palmar region of the foot and away from damaged and weakened areas. The hoof wall defects prevent normal nailing procedures; therefore clips or support bars (Figure 28-2) can help to secure the shoe to the hoof. After hoof wall removal the exposed laminae may still have an active infectious component. The horse should be kept in a clean, dry stall; the exposed laminae are treated topically with iodine or thimerosal (Merthiolate) daily for 10 days or until they are dry. The horse may then be a candidate for prosthetic hoof wall repair using a product such as Equilox (Equilox International, Pine Island, Minnesota, United States). The plastic acrylic is trimmed and shaped to the horse’s natural hoof wall at the next shoeing. The hoof to which the acrylic is applied should be kept dry to avoid losing the acrylic patch. The horse may return to normal activity once the prosthetic patch is in place. It is very important to keep the patch dry, including preventing the horse from going out in the pasture when the morning dew is still present on the grass. The owner should be cautioned that 50% of prosthetic patches may result in infection and abscessation under the patch, which will necessitate removing the patch and topically treating the exposed laminae again. It can be very difficult to sterilize the exposed laminae given the horse’s barn environment.

Poor Hoof Wall Quality

Poor hoof quality plagues many horses. Many factors determine hoof quality, including the environment, farrier management, hoof conformation, owner management, and use of the horse. Drought conditions may result in dry, brittle hooves that are prone to hoof wall splitting, cracking, and bruising. Foot growth slows during hot, drought conditions. Excessive moisture creates a weakened hoof wall that may flatten or collapse under normal weight-bearing forces. The heel may collapse, which leads to corns and heel bruising. In addition, the weak hoof wall will not hold nails, and the hoof wall separates in layers similar to wet plywood. A muddy environment may increase the risk of development of a secondary hoof abscess. Even worse is a fluctuation of wet-dry-wet-dry environments. Four problems that contribute to the wet-dry environment require owner education. The first is the growth of spring grass that gets high. Horses that are on pasture are exposed to the morning dew on the grass (wet), then the dry heat during the days (dry), and this morning wetness and afternoon dryness cause hoof wall separation, nails that loosen, and shoes that will not stay on. The second problem occurs when horses are allowed access to a pond or stream during the hot summer months. The horse’s feet are dry until they wade into the water and then get wet; this causes brittle and cracking hoof walls. Another potential problem is daily washing of the horses after exercise during the hot summer months, or if an owner lets a water trough overflow to create a mud hole for a horse to step into. The wet-dry fluctuation causes poor hoof wall quality. Improper trimming and shoeing methods can cause substantial hoof wall damage. Horseshoe nails that are placed too far outward in the hoof wall, or exit too low in the hoof wall, weaken the hoof wall and cause splitting and cracking. Many TB horses with long-toe–low-heel hoof conformation often have collapsing heels and thin, weak hoof walls that make proper nail placement and farrier management difficult. The most common cause of weak, poor-quality feet is lack of exercise and stall housing.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is somewhat subjective, as poor hoof quality is usually in the eye of the beholder. There are no objective criteria for determining hoof quality. Diagnosis is usually made by visual examination of the foot. Communication with the farrier is imperative for the diagnosis and future treatment plan. Horses with poor hoof wall quality often have palmar foot pain or are prone to sole and heel bruising. They are prone to losing shoes, which can accentuate the problem.

Treatment

If possible, the cause of the poor hoof wall quality should be corrected if identified. In drought conditions, painting the entire hoof and coronary band daily with a lanolin-based hoof dressing is sometimes beneficial. We prefer the product Hoofmaker (www.manentail.com). In an excessively wet environment, confining the horse to a stall and avoiding standing water or wet pastures may improve hoof wall quality. Educating the owner concerning causes of wet-dry fluctuation is very important. If a horse is going to be in wet conditions, instruct the owner to paint the hoof wall with a hoof sealant to seal the moisture out of the feet. We have used a product called “Hoof Shield” (www.monettafarrier.com) with good success. Poor farriery can be addressed, but in many horses poor hoof conformation and poor environment are more difficult to manage. Unbalanced long-toe–low-heel hoof conformation should be corrected as much as possible with proper trimming of the heel back to the widest portion of the frog. The toe of the foot is shortened as much as possible, and a rockered, round, or square-toed shoe is used to further decrease toe length and ease breakover. Egg bar shoes are used if more heel support is needed. Access to the outdoors and being able to move about are helpful but often difficult to achieve.

Hoof quality also is a function of proper diet and exercise. The horse’s nutrition should be evaluated, paying particular attention to protein quantity. Biotin supplements may be beneficial.

Penetrating Injuries of the Sole

Subsolar Abscess

History and Clinical Signs

Subsolar abscess (gravel) is one of the most common causes of acute lameness in all horses. Subsolar abscesses may originate from a penetrating wound in the white line, nail hole, or deep subsolar bruise. A cause may not be identified. Lameness is usually acute and severe (grade 3 to 4 of 5) and may worsen over time until drainage is established. Lameness that develops during work or when a horse is turned out may falsely lead to the suspicion of a traumatic injury. The horse often points and may not bear full weight on the affected limb. Distal limb swelling often accompanies a subsolar abscess that has not drained, leading the owner to suspect tendon injury. Systemic signs of infection (fever, lethargy) may be present if deeper structures are involved. The infected tract may migrate and open at the coronary band. Before breaking open, a soft, painful area can be located by digital palpation of the coronary band.

Diagnosis

Digital pulse amplitudes are usually, but not always, increased, and the hoof capsule may have heat. A focal painful area can usually, but not always, be located with careful hoof tester examination. If the sole is extremely hard, it may be difficult to locate a subsolar abscess. Careful paring of the sole and frog may be helpful in locating the abscess, assuming that the horn is not too hard, but the clinician must be careful not to damage good, healthy tissue while looking for the infection site. Unnecessary, aggressive paring may lead to large painful areas that take months to heal. Foot poultices and hot water foot baths with Epsom salts help to soften the horn and eventually localize the affected area, especially in horses with hard horn. Grey or black, malodorous liquid leaks from the infected tract (see Figure 6-10). Firm digital palpation of the surrounding area can help to determine the extent to which adjacent tissues are underrun. Similar clinical signs can also be seen in weak-footed TB horses, especially in the palmar aspect of the foot, associated with frank subsolar hemorrhage. Radiography sometimes is useful to identify a gas or fluid pocket (see Figure 129-1). In horses with no localizing clinical signs, it may be necessary to use local analgesic techniques to determine the site of pain causing lameness. Severe lameness associated with a subsolar abscess may be only partially improved by apparent desensitization of the foot.

Treatment

Treatment is aimed at establishing adequate drainage. If the tract is open at the sole surface, it should be enlarged just enough for good irrigation and drainage. This may require sedation or perineural analgesia of the foot. If pink tissue or blood is encountered, debridement should be discontinued. Large holes should not be used, to avoid solar corium protrusion, which can be a painful sequela to overzealous hoof paring. If drainage occurs at the level of the coronary band and solar surface, through-and-through lavage is beneficial. Debridement at the coronary band level should be minimal to prevent iatrogenic DIP joint contamination. Once drainage is established, the foot is protected from the environment and recontamination with a foot bandage or poultice. Continued foot soaks in warm water povidone-iodine and Epsom salt foot baths should be continued until infection and inflammation are eliminated. The shoe is replaced when the affected area is dry and cornified. A small cotton ball soaked in tincture of iodine is often placed in the defect before reapplication of the shoe to prevent recontamination of the site. Large areas may require a plastic pad under the shoe for solar protection. Antimicrobial drugs and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are rarely needed, unless infection is severe or deeper structures have been penetrated. Many practitioners consider antibiotics contraindicated because administration may prolong clinical signs. However, if swelling and infection of the coronary band and subcutaneous tissues of the pastern region occur, antimicrobial therapy is indicated. Because lameness can be severe in horses with this type of disseminated infection, involvement of the DIP joint is often suspected but usually not present. Tetanus prophylaxis is mandatory.

Deep Penetrating Injuries to the Sole

History and Clinical Signs

A horse’s environment is filled with sharp objects that can penetrate the sole, causing severe damage to structures deep within the hoof capsule. All puncture wounds should be considered potentially serious, but those in the solar white line or palmar frog area require special attention because of the potential for navicular bursa, digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS), deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT), DIP joint, or distal phalanx involvement.

The clinical signs vary with anatomical structure involved and chronicity of the injury. Lameness may be mild at the time of injury but moderate to severe once inflammation and infection occur. Penetrating wounds of the navicular bursa or DDFT result in severe lameness and a reluctance to bear weight on the heel.

Diagnosis

If a foreign body is found in the bottom of the foot, the owner should usually be instructed to leave the object in the foot, unless there is danger of further penetration. Radiography is performed immediately to determine depth of penetration and orientation, and orthogonal images are mandatory. In many horses, little superficial evidence of penetrating injury is present. Digital pulse amplitudes are increased, and the foot is usually warm to touch. Hoof testers are useful to determine a focal point of pain, but often the entire surface of the foot is reactive. If necessary, the horse should be sedated and the foot desensitized to facilitate further examination. Light paring of the sole and frog areas with a hoof knife may reveal a black spot indicating the penetration site. Often, however, the entry is not discovered, because the elastic nature of the hoof structures causes the site of penetration to collapse. If an entry wound is discovered, the foot is scrubbed thoroughly before insertion of a sterile, flexible probe. Care must be used so that inadvertent force and horse movement do not cause the probe to penetrate previously unaffected structures. A less invasive and preferred method is to place a sterile teat cannula into the hole and inject sterile radiodense material to determine the affected structures (Figure 28-3). It is important to obtain a true lateromedial radiographic image to determine the dorsal spread of the contrast media.

Fig. 28-3 Oblique radiographic image of a foot; radiodense contrast material has been injected into a hole through the sole, the result of a penetrating injury. The contrast media extends proximally. A lateromedial image is also required to define better which structures may be involved.

If infection of the navicular bursa (see later), DIP joint, or DFTS is suspected, paracentesis, synovial fluid cytological studies, and culture and antimicrobial susceptibility tests should be performed. Comprehensive radiographic examination should be performed to assess the distal phalanx and the navicular bone. Initial radiographs may appear normal, but radiolucent defects or new bone formation may become apparent within 10 to 14 days. Magnetic resonance imaging can be extremely useful to identify the extent of soft tissue injury in the face of a known penetrating injury9 and to provide evidence of a previous penetrating injury in horses with lameness with no known history of such injury. The identification of a hemosiderin tract leading to an area of damaged tissues is pathognomonic.10,11

Treatment

If penetration of deep hoof structures is suspected, broad-spectrum systemic antimicrobial drugs, NSAIDs, and tetanus prophylaxis should be administered. During the initial 3 to 4 days, distal limb regional limb perfusion with an antibiotic (1 g amikacin or 2 g cefotaxime diluted in 30 mL saline) is also recommended, to achieve high local tissue concentrations of antibiotics. Systemic antibiotic therapy usually should be continued for 2 weeks after resolution of clinical signs of infection. Establishment of drainage, copious lavage with sterile ionic fluid, and debridement of all necrotic tissue are indicated. Management of infection of the navicular bursa is discussed later (page 316).

If the DDFT is involved (infectious tendonitis), debridement and removal of frayed and infected tendon fibers may be performed in a standing, sedated horse using a tourniquet and perineural analgesia, or with the horse under general anesthesia depending on horse temperament and owner financial constraints (see later). After debridement, use of a 4- to 8-degree wedge shoe decreases forces on the DDFT and provides some pain relief. The wedge shoe angle is gradually decreased over several months as the DDF tendon begins to heal and strengthen. The bottom of the foot requires protection with a bandage or hospital plate until the surgical site granulates in and cornifies.

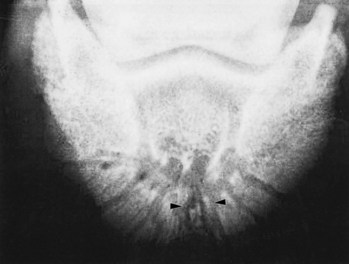

Infectious Osteitis of the Distal Phalanx

Deep penetrating wounds to the sole, especially the solar–white line junction, can result in infectious osteitis of the distal phalanx. Usually a chronic, recurrent draining tract is located at the coronary band or solar surface of the foot, associated with variable lameness. Infection of the distal phalanx also can result from undetected soft tissue infection, from dissection of subsolar abscesses, or as a sequela to laminitis secondary to recurrent abscessation and ischemia at the toe. As the bone infection progresses, blood supply to the area is compromised, and the area of avascular bone separates from the parent bone, forming a sequestrum.12 Radiological abnormalities may not be detectable for weeks after a penetrating injury.12 Radiography reveals a radiolucent area in the margin of the distal phalanx, with or without sequestrum formation (Figure 28-4). Debridement and curettage of all soft and necrotic bone often can be performed in a standing, sedated horse, but general anesthesia may be required. The foot is desensitized using perineural analgesia, cleaned with a hoof knife and steel brush, and prepared for aseptic surgery. Hemostasis is achieved by wrapping a roll of elastic bandage firmly around the fetlock joint to compress and occlude the palmar digital arteries. The infected bone is accessed by removal of sequential layers of the sole using either a motorized Dremel tool or a Galt trephine (Miltex, Bethpage, New York, United States) with a retractable pilot bit.13 The infected bone usually is discolored and soft and should be curetted to healthy bone margins. Culture of the infected bone and microbial sensitivity testing should be performed. A postoperative radiograph should be obtained to ensure complete debridement. After surgery the surgical site is packed with sterile gauze sponges soaked in antiseptic or antimicrobial solutions, and then the foot is bandaged. Disposable diapers and duct tape are inexpensive materials used to make a waterproof foot bandage. The bandage is changed at 1- to 2-day intervals for the initial few weeks. A bar shoe and hospital plate provide solar protection. A plastic pad secured with duct tape also works well. The bolts and metal plate are removed from the hospital plate, and the surgery site can be cleaned and treated; the plate then is bolted back in place. After surgery the horse is confined to a small area until the hole granulates and cornifies, which usually requires 4 to 6 weeks. If granulation tissue becomes excessive at the surgery site, application of 2% tincture of iodine speeds healing. If severe infection is present, the surgery site can be packed lightly with antibiotic-impregnated beads for continued antibiotic release at the infected site. Regional limb perfusion with antibiotics may also be beneficial.

Fig. 28-4 Dorsoproximal-palmarodistal oblique radiographic image of the distal phalanx demonstrating infectious osteitis with a sequestrum (arrowheads).

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on whether the infection is severe and chronic. Horses with acute penetrating wounds that receive immediate and aggressive treatment have a good chance of returning to athletic use. Horses with penetration injuries that have an established infection involving the navicular bursa (see later),14 DFTS, or DIP joint have a poorer prognosis. Prognosis for horses with infectious osteitis of the distal phalanx is good if the cause of infection is not laminitis. In one study, up to 24% of the distal phalanx was removed with successful results.15

Penetrating Wounds to the Navicular Bursa (Bursa Podotrochlearis), Infectious (Septic) Navicular Bursitis, “Streetnail”

Penetration of a nail or other sharp object into the solar surface of the foot is classically referred to as “streetnail,” and the historically important procedure to establish drainage of the navicular bursa is the “streetnail procedure.” The term streetnail and the surgical procedure are largely obsolete, but the clinical significance of penetrating wounds to this region of the foot cannot be overemphasized, particularly those involving the region of the frog. Of 50 horses with puncture wounds to the hoof, only 50% of horses with wounds in the region of the frog became sound after treatment, whereas 95% of horses with puncture wounds outside the frog were sound.16 Furthermore, 35% of horses with puncture wounds to the frog were dead at the time of follow-up.16 Infectious navicular bursitis and sequelae were the most common reason for euthanasia.16 Early recognition and prompt management of horses with puncture wounds to the hoof, and specifically those involving the frog and deeper tissues such as the DDFT, navicular bursa, navicular bone, and DIP joint are equally important. Ninety-three percent of horses that received surgical management within 7 days became sound, compared with only 62% of horses that were treated after 7 days.16 Horses with infectious navicular bursitis that received surgical management within 1 week of injury had a significantly better outcome than those with delayed recognition and management (8 to 60 days after injury).14 Horses with hindlimb infectious navicular bursitis were significantly more likely to have a successful outcome than those with forelimb involvement.14 Of 38 horses with infectious navicular bursitis managed using the conventional open streetnail procedure of debridement and drainage of the navicular bursa, only 12 (31.6%) had a satisfactory outcome, but when results were carefully evaluated, five of these horses were used as broodmares, leaving only seven (18.4%) horses used for riding after injury.14 Similarly, 31.6% (six of 19 horses) of horses with infectious navicular bursitis managed with open drainage and debridement became sound enough for work.16

Because of these disappointing results the conventional surgical procedure of creating a “window” in the frog, digital cushion, and DDFT17 to establish distal drainage of the navicular bursa has largely fallen from favor and cannot be recommended. Currently, endoscopic examination of the navicular bursa and other synovial structures such as the DIP joint and DFTS, if necessary, is the procedure of choice. Endoscopic examination is less invasive, causes fewer complications, and provides superior visual appraisal of the navicular bursa, navicular bone, and DDFT when compared with the conventional open approach. Of 16 horses with contaminated and infected navicular bursae that underwent endoscopic examination and debridement, 12 (75%) became sound, and complications such as ongoing necrosis of the DDFT seen in horses managed with the conventional streetnail procedure did not occur.18 There were fewer complications and shorter hospital stays, and horses appeared to be immediately more comfortable after surgery compared with previous reports; three horses with concurrent infection of the DIP joint were managed successfully.18

Although actual results may vary among horses and surgeons, it appears that success in managing horses with infectious navicular bursitis using minimally invasive techniques is superior to that described in the previously published results and our own experience using the conventional approach to drainage and debridement of the navicular bursa. It is important to note that early recognition and management are critical. It is also important to establish the location and depth of penetration, and a minimum of two orthogonal radiographic images are necessary, if possible with the nail or penetrating object in place. After the puncture site has been cleaned, a sterile radiodense probe can be inserted, but in some horses the depth of penetration cannot be accurately determined using this method, and there is a risk of pushing foreign material deeper into the foot. Positive contrast radiographic studies should be considered, but these may not clearly show the depth of penetration. Magnetic resonance imaging can provide rapid, accurate information about the direction and depth of penetration, the presence of foreign material, and the extent of soft tissue and osseous trauma. Synoviocentesis of the navicular bursa, DIP joint, and DFTS should be performed to determine if a deep-seated contamination or infection is present. With use of general anesthesia and aseptic technique, endoscopic examination of the involved synovial structures should then be performed. The navicular bursa and palmar surface of the navicular bone and DDFT can be evaluated endoscopically and debrided. Debridement can be performed through the original penetrating tract and by creating an additional instrument portal if necessary. Samples for bacterial culture and susceptibility testing (aerobic and anaerobic) should be collected, and the tract and frayed and damaged edges of the DDFT should be debrided. Although liberal debridement can be performed, no attempt is made to make a wide incision of the DDFT. During the procedure, lavage of the navicular bursa is performed. In thick-skinned cob-type horses direct surgical access to the navicular bursa may not be possible and entry may have to be performed via the DFTS. Thorough lavage of the DFTS is mandatory to try to prevent spread of infection. Occasionally in horses with long-standing infections and concomitant osteitis of the navicular bone, or in those in which the navicular bone was directly damaged by the original trauma, the navicular bone is curetted. If necessary the DIP joint can be evaluated, but timing of examination should be preplanned because using a contaminated endoscope after evaluating a penetrated navicular bursa to evaluate a potentially uninvolved DIP joint is contraindicated. The application of a hospital plate, use of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, NSAIDs, and daily regional limb perfusion of an aminoglycoside antibiotic are recommended. Once infection is fully resolved, medication of the navicular bursa with corticosteroids may be beneficial. Although emphasis on early management is important, we have had success in horses with long-standing infectious navicular bursitis, some with radiological evidence of osteitis and fragmentation of the navicular bone, and in horses with initially severe forelimb lameness. However, when owners are spoken to initially, a guarded prognosis for future soundness should always be given, although using this approach to management of horses with penetrating wounds into the navicular bursa and surrounding structures can lead to success. Once infection is resolved, prognosis for return to full athletic function often depends on the degree of concurrent traumatic damage to tendonous and ligamentous structures within the hoof capsule incurred at the time of original injury.

Hoof Wall Cracks

History and Clinical Signs

Hoof wall cracks occur from improper foot balance; coronary band defects; excessive hoof growth; and thin, dry, or wet hoof walls. The horny hoof wall often fails internally before being visible on the external hoof surface.19 Central toe cracks are often associated with rotation of the distal phalanx and clubfeet. Hoof cracks are characterized by location (toe, quarter, heel, or bar), length (complete or incomplete), depth (superficial or deep), site of origin (ground surface or coronary band), and whether hemorrhage or infection is present.19 Hoof cracks are usually obvious on visual examination of the foot, except those originating at the hairline, which may be only 1 to 2 cm long and difficult to see. Lameness may be present, depending on whether the hoof crack involves the sensitive laminae and whether infection is present.

Diagnosis

Hoof wall cracks are diagnosed by visual assessment of the hoof capsule. The depth of the hoof crack, pain, and associated instability surrounding the crack are determined by careful hoof tester examination. Pain associated with a hoof crack is usually determined by digital pressure and hoof tester manipulation over the crack. Purulent material may exude during hoof tester pressure. Radiology is useful to evaluate rotation of the distal phalanx in horses with central toe cracks. Bleeding from a hoof crack after exercise indicates that the sensitive laminae are involved.

Treatment

Treatment varies with hoof crack location, depth, horse use, and presence of exposed sensitive laminae and infection. Superficial hoof cracks do not extend into laminar tissue and therefore are not painful. These may be the result of improper foot balance or basic neglect regarding trimming. Treatment involves balancing the foot and providing stability by application of a full bar shoe. If the horse is shod correctly and restricted from strenuous activity, most hoof cracks will resolve.20

Treatment of horses with deeper hoof cracks varies somewhat with location of the crack. If lameness exists, diagnostic analgesia should be performed to confirm that the hoof crack is the source of pain. Careful observation of the affected foot as the horse walks slowly often shows that the defect is unstable and actually closes and pinches the underlying sensitive laminae as the foot strikes the ground, causing pain. The hoof crack is explored and debrided with a hoof knife or motorized burr (Dremel tool) to remove all necrotic and infected tissue. Any undermined hoof wall is also removed. The area is treated for 24 to 48 hours with an antiseptic such as thimerosal (Merthiolate) or tincture of iodine until the crack is dry and free of infection. The hoof wall must be stabilized so that it can regrow. Previous recommendations have suggested grooving or burring the proximal extent of the crack, but this is rarely successful.19 Many techniques for hoof wall stabilization use a combination of frog support with a heart bar shoe and clips combined with a fiberglass patch,20 drill and lace technique,19 metal plate technique, or a technique using composite hoof wall repair with acrylic materials (see Chapter 27). The heart bar shoe is essential to oppose the forces causing collapse of the crack during weight bearing. The toe must be trimmed short and squared before application of the shoe. The drill and lace technique is used if the deep crack does not extend to the coronary band, and the metal plate technique is used if it does. In the metal plate technique, two drill holes are placed 1 to 2 cm on either side of the trough directly opposite each other. Care is needed to ensure that drilling too deeply does not affect deeper hoof structures. The foot should not be desensitized, to allow the farrier and veterinarian to assess if there is inadvertent iatrogenic penetration of deeper tissues with the screws. One or two plates are cut that are longer than the exposed hoof crack and about 0.6 cm wide. With the foot held in a non–weight-bearing position, the metal plate is drilled and bolted in place to stabilize the crack. The hoof wall adjacent to the toe crack is trimmed shorter than the remaining hoof wall to minimize weight-bearing forces on the damaged area and decrease potential bending forces on the plate. The crack is treated for several days with thimerosal (Merthiolate) or tincture of iodine until the sensitive structures begin to cornify and infection has resolved. The hoof crack can then be filled with an acrylic material (e.g., Equilox, Equilox International, Pine Island, Minnesota, United States). Adhesion of the acrylic to the hoof wall is enhanced by sanding the hoof wall, applying acetone to dry the area, and using a hair dryer at the external hoof surface before acrylic application.

Quarter and heel hoof cracks often are incomplete, and low-heel–long-toe conformation with an underslung heel may predispose horses to develop them.19 After the crack has been debrided and infection eliminated, the foot is balanced and a heart bar shoe applied. Two holes are drilled, using a 0.24-cm drill bit, approximately 1 to 2 cm apart on either side of and parallel to the crack. The holes begin at the ground surface and extend up the hoof wall. A shoelace or synthetic multifiber suture is laced in a far-near-near-far suture pattern to stabilize the crack.19 Another technique is to trim the hoof wall behind the quarter crack shorter than the remaining hoof wall such that it does not touch the shoe while weight bearing, applying a bar shoe and stabilizing the proximal extent of the crack after it has been debrided (Figure 28-5). After the crack is dry and free of sensitive tissue and infection, it is filled with acrylic material. Readers are also referred to Chapter 27.

Coronary Band and Hoof Wall Lacerations

History and Clinical Signs

The hoof wall is thicker and stronger at the toe region and becomes thinner through the quarters and heel, where the younger hoof has a greater moisture content.20 The quarter and heel regions of the foot are susceptible to traumatic injuries. Coronary band and hoof wall lacerations usually occur from the horse catching a segment of hoof on an object as it steps down or kicking or stepping on a sharp object. Hoof avulsion injuries also can occur when the foot is entrapped between fence boards or in a cattle guard. Continued hoof imbalance, improper shoe removal, and repetitive trauma to the coronary band region result in a chronic hoof avulsion or spur—a fibrous bed of scar tissue beneath a displaced segment of hoof wall. Horses that overreach are predisposed to coronary band spurring or heel avulsion injuries. Steeplechase horses and horses racing on grass often slip and lacerate the heel region of a front foot.

Hoof avulsions are described as acute (lacerations) or chronic (repetitive trauma and spur formation) injuries. Avulsions can be complete, with total tissue loss, or incomplete in that a border of hoof remains intact. Hoof wall, coronary band, sole, distal phalanx, laminae, and the DIP joint may be involved in deep lacerations. The degree of lameness varies with duration, depth, and location of the injury. Horses with acute, superficial injuries may show mild lameness, and horses with deeper structure involvement may be non–weight bearing. If degree of lameness does not seem appropriate for severity of the laceration, the integrity of the palmar digital vein, artery, and nerve should be investigated.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is straightforward, but involvement of deeper structures can be difficult to identify. Careful manipulation of the foot causes a painful reaction if deep structures are involved and provides valuable information regarding the integrity of the supporting hoof structures. Instability of the DIP joint may indicate the presence of collateral ligament damage. If manipulation produces a sucking noise, the DIP joint or DFTS may be involved. Before further evaluation the coronary band hair should be clipped, the outer hoof wall rasped, and the sole trimmed to eliminate any superficial contamination. The area should be scrubbed with antiseptic solution, and lavage performed. The wound then is digitally explored by the veterinarian using sterile gloves. Radiography is recommended for all deep lacerations, because fractures of the distal or middle phalanges may be present. Contrast radiographic studies may be necessary to identify openings in synovial structures. Alternately, a site far removed from the wound is clipped and prepared in a sterile manner, and the DFTS and/or DIP joint is distended with sterile saline to determine if it communicates with the laceration. Ultrasonographic examination may help to determine the extent of soft tissue damage. Bear in mind that foreign material such as wood may become trapped axial to the hoof wall, and such material may be inapparent on radiographs. The DIP joint was the most common synovial structure involved in a recent study of 101 heel bulb lacerations.21

Treatment

The equine foot heals primarily by epithelialization and reformation of the corium.22 Decreasing motion at the affected site and hoof stabilization are essential for a successful outcome. Treatment varies with duration, severity, and type of injury. Incomplete, superficial hoof wall lacerations without coronary band involvement are treated by excision of the separated hoof wall and bar shoe application until healing occurs. The goal of shoeing is to eliminate weight-bearing forces at the damaged site and provide hoof stability.

Horses with incomplete, clean, acute hoof avulsions involving the coronary band can be treated by cleaning and debriding the displaced flap of tissue and suturing it back in place. This generally requires general anesthesia. Interrupted vertical mattress sutures with No. 1 or No. 2 monofilament suture are recommended.21,22 Any undermined or contaminated hoof wall is removed. Immobilization is essential and is provided by applying a foot cast. The cast is usually left in place for 2 to 3 weeks. When applying the foot cast, the clinician should ensure that the proximal extent of the cast is located at midpastern level and does not impinge on the fetlock joint during movement. Administration of systemic antimicrobial drugs and NSAIDs may be necessary if contamination of deeper structures is suspected. If deeper structures are involved, cast application should be delayed until infection is eliminated. Open synovial structures can be lavaged daily, and the foot is protected with a sterile foot bandage. Antibiotic-impregnated beads and regional limb perfusion with antibiotics may be necessary with severe contamination.

Horses with compete avulsion injuries that appear stable during movement are treated by daily cleaning and bandaging until healing occurs. Bar shoe application is required if the hoof is unstable and contaminated. A foot cast can be used if infection is not a problem.

Repair of a chronic avulsion injury, or spur, usually requires surgical excision with the horse under general anesthesia. The hoof is rasped and prepared for aseptic surgery. The hoof wall distal to the avulsed segment should be thinned with a rasp to allow placement of the sutures through the hoof wall. The excessive cornified tissue growing from the displaced coronary band is trimmed to a level just distal to the coronary band. The fibrous tissue under the avulsed segment, which lies in the bed of the defect created by the hoof avulsion, is resected. This provides a vascularized area and room for replacement of the avulsed segment back to its original location. The displaced coronary band and hoof wall are replaced and sutured in the correct anatomical position using No. 2 monofilament suture in a simple interrupted or vertical mattress suture pattern. The surgery sites are covered with a light bandage, and the foot is immobilized in a foot cast for 2 weeks.

Prognosis

Treatment is usually prolonged and often takes 3 to 5 months for complete healing, which can be costly to the owner.22 Incomplete superficial avulsion injuries or injuries that can be sutured usually heal by first intention, with a good functional, and sometimes cosmetic, end result. A roughened or thickened hoof wall distal to the defect often occurs at the site of avulsion, but it usually does not create a clinical problem. Prognosis decreases if deeper structures or synovial structures are involved. Complications such as infectious arthritis, fractures, and potential osteoarthritis can occur often with a guarded prognosis. In a retrospective study involving 101 horses sustaining a heel bulb laceration, 90% survived but 18% developed a hoof wall defect.21

Canker

Canker, a proliferative pododermatitis of the frog that may extend to undermine the sole and heel bulbs, is common in draft horses (and is discussed in detail in Chapter 125) but occurs in light horses as well. Differentiating this form of infection from the more common infection, thrush, is important. Canker is characterized by a foul odor (necrotic) and the presence of granulation-like tissue that bleeds easily when manipulated (see Figure 125-5). The principles of management are debriding, using a hospital plate and packing to maintain pressure on the healing solar wound, keeping the area clean, and applying topical antiseptic solutions or antimicrobial agents such as metronidazole (see Chapter 125). Alternatively, 53 of 54 horses with canker and in which long-term follow-up information was available were successfully managed using liberal debridement, topical cryotherapy, and the application of benzoyl peroxide on packing under a hospital plate.23