Chapter 125Lameness in Draft Horses

The draft horse today enjoys a position in the world far different from when it was considered primarily a work animal. Draft horses supplied power for farming, transportation of commodities, lumbering, road building, and all such tasks until the 1930s, when the gasoline engine essentially replaced the horse. Isolated areas still continued to use the draft horse for farming and some lumbering activities until the early 1940s. After this period, draft horses were used primarily for specialty areas such as movie production, theme parks, parades, and frontier celebrations. But in some communities, religion and family tradition mandated the continual use of draft horses as a power source for farming. During the 1950s and 1960s, draft horses decreased in numbers in the United States, and subsequently the genetic pool was decreased. Draft horses started gaining popularity in the late 1970s and early 1980s and have once again become a popular member of the horse industry.

Draft horses today are different from those of the early 1900s. They perform different functions and are owned for a different purpose. Owning a draft horse is far more likely to be simply a hobby than an economic part of the family income. Many horses are used strictly for show purposes in classes such as halter, fine harness, and equitation, or for parades and advertising. Draft horses are used for trail riding, pleasure riding, fox hunting (often crossbred with Thoroughbreds), and other pleasure uses. In some mountain areas where selective lumbering of individual trees is undertaken, draft horses are still used today. With a resurgence of interest in mules, draft horse mares often are used in the breeding programs. Draft horses frequently are crossed with Thoroughbreds to change the genetic pool for the breeding of large hunter, jumper, and Three Day Event horses. Pulling contests are popular in certain areas and represent an additional use of the modern-day draft horse.

Modern-Day Draft Horses

The most important physical change of the modern-day draft horse is its size. In many modern breeding operations, size is the main criterion used for selection. When draft horses were used predominantly as working horses, the average weight was 680 to 775 kg (1500 to 1700 lb) and the average height was 1.6 to 1.7 m (15.5 to 17 hands). This size was optimal for the multipurpose activities these horses performed on most farms and ranches. They pulled the plow, mowed and racked hay, helped round up cattle, and often took the family to church on Sunday. Draft horses today are more frequently in the range of 820 to 1000 kg (1800 to 2200 lb) and measure 1.8 to 2 m (17.5 to 19.5 hands) in height. As a result of selection based on size as the dominant characteristic, conformation and quality have suffered in some respects. Distribution of lameness also has changed. Foot size and quality have not increased proportionately with body size and weight. Osteoarthritis (OA) is common in draft horses and likely is related to body size rather than the use of the horse. Hybrid vigor, once thought to be advantageous, has decreased by using the practice of line breeding for selected traits. The large size of a draft horse sometimes misleads one to think the horse can withstand greater stress and disease than can light horses, but I have not found this to be true. Draft horses may not recover as well as light horses with the same injury or disease. Because draft horses have a tendency to be stoic, recognizing a severe problem early in the disease process may be difficult. This tendency may cause a costly delay in diagnosis and management. The physical size of draft horses today has hindered veterinary care and treatment. Veterinarians tend to be unsure of drug dosage and appropriate treatment schedules because of the large body size. Many hobby horse owners do not have facilities adequate to handle a 1000-kg horse and may not be knowledgeable in draft horse care. Draft horses are not always well trained or easy to handle, and owners are sometimes unable to lend assistance when needed. These facts have curtailed the interest of many practicing veterinarians who have difficulty rationalizing being stepped on by a 1000-kg draft horse as fun. In addition, finding high-quality foot care for a draft horse is sometimes difficult, because most farriers are experienced with light horses. Farriers feel similar to veterinarians: “Why hold up a 1000-kg horse twice as long as needed to hold up a 500-kg horse?” In addition, farriers who shoe draft horses have to stock nails, shoes, and bar stock often on special order or low-volume items, a fact that dramatically increases overhead expenses. Thankfully, some veterinarians and farriers are willing to treat and specialize in draft horse care.

The following discussion related to draft horse lameness reflects my personal clinical experiences and not necessarily what may be in the equine literature. Lameness distribution may vary from my observations depending on the use, location, individual draft breed studied, or other factors associated with different populations of horses.

Lameness Examination

Diagnosis and management of lameness in a draft horse may seem more intimidating simply because of the large size of the horse and the infrequency with which requests are made for examination compared with light horses. In reality, draft horses experience the same problems as do light horses, although the distribution is different, and the principles of diagnosis and management are the same. The lameness examination is the same as in light horses, and any deficiency of hands-on experience can be overcome by a systematic and thorough examination. Palpation of peripheral nerves (palmar and plantar digital nerves, in particular) can be difficult because of thick skin and hair, and veterinarians are sometimes reluctant to attempt perineural or intraarticular blocks. The anatomy is the same, but the ability to palpate the nerves is diminished by these factors and also by subcutaneous thickening that some draft horses develop in the lower part of the limb.

Draft horse lameness diagnosis and management lagged behind those of light horses for many years. First, as long as the horse could still accomplish farm work, less concern was shown for a horse that limped slightly. Possibly the person behind the plow or cultivator also limped and accepted it as part of doing the job. Second, economic considerations were a major factor in the farming operation. This does not reflect necessarily a lack of care, but it was simply an accepted part of working in that day and time. But today, draft horses are afforded the same concerns and care given to the light horse, and only modification of most treatment protocols needs to be made.

Detailed description of the lameness examination can be found in earlier chapters. Special attention should be paid to several critical points, however. Draft horses are more stoic than light horses, and as a result lameness may be advanced when first recognized. For example, draft horses with OA of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) or distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints may have severe radiological changes, but the owner may report that the horse only recently showed signs of lameness. Granted, many owners are inexperienced, but even the experienced owner may not recognize a problem until it is well advanced. This can be explained partially by the fact that a draft horse often is used at a gait (walk) that makes lameness less obvious, and the horse frequently is hitched with one to seven additional horses, and an individual horse’s problems are less discernible in a group.

When possible, observing the horse at a walk and trot on soft and hard surfaces is useful. Hoof tester examination, in my experience, is less reliable in draft horses than in light horses. Small hoof testers are of questionable value. Even with long-handled hoof testers, it is difficult to apply enough pressure to produce a positive response. Foot lameness should be suspected if a horse shows grade 1 of 5 lameness on soft footing but grade 3 of 5 lameness on a hard surface. The examination always should include backing the horse at least two or three times and observing the horse at the walk and trot in a circle and in tight turns. Sometimes conditions such as shivers, stringhalt, or intermittent upward fixation of the patella are seen only during these maneuvers.

Lower limb flexion tests are less rewarding in draft horses than in light horses. It is difficult to apply sufficient pressure during the flexion test to accentuate pain in this region. A draft horse may be less willing to trot after a flexion test, making it difficult to determine a true positive response. Most light horses will trot after flexion, even when the reaction is highly positive, but a draft horse will not trot off as readily without strong urging. In addition, draft horses often are not accustomed to being trotted in hand routinely. Hindlimb upper limb flexion tests in a draft horse are a more reliable indicator of hindlimb lameness than in a light horse.

I prefer to perform diagnostic analgesia with the horse in a standing position, rather than having an assistant elevate the limb. This is especially true when attempting palmar digital nerve blocks or palmar nerve blocks at the base of the PSBs. Palpating anatomical landmarks in this area when a draft horse is bearing weight is easier than when the limb is elevated. To maintain the limb in an elevated position or to restrain the limb in this position can be difficult. Adequate restraint usually can be achieved by the application of a nose twitch.

Ten Most Common Lameness Problems

Over several years I evaluated 745 draft horses admitted with a chief complaint of lameness. The following list shows the top 10 lameness conditions that I observed in order of decreasing frequency (33 horses had other problems):

| 1. Foot lameness (abscess, hoof cracks, laminitis, and sidebone) | 260 |

| 2. Tarsal lameness (osteoarthritis, bog spavin, and osteochondrosis) | 207 |

| 3. Splints | 84 |

| 4. Tendonitis and suspensory desmitis | 45 |

| 5. Osteoarthritis of the distal interphalangeal or proximal interphalangeal joints | 44 |

| 6. Fetlock lameness (sesamoiditis, osteoarthritis, and osteochondrosis) | 23 |

| 7. Thoroughpin | 18 |

| 8. Carpal lameness (traumatic or infectious carpitis) | 13 |

| 9. Stifle lameness (traumatic, upper fixation of the patella; osteochondrosis) | 10 |

| 10. Myopathy | 8 |

Lameness Common to the Forelimb and Hindlimb

Foot

The foot is the most common source of pain causing lameness in draft horses. A thorough and complete examination of the foot is paramount to diagnosis and management of lameness. Hoof quality and conformation have suffered in modern-day breeding selection, and as a result we tend to have large horses that are supported on feet that lack hoof size and quality. I suggest that breeders of draft horses give strong consideration to hoof conformation when making critical selections for breeding programs.

Subsolar Abscess

The most common cause of foot lameness in a draft horse is a subsolar abscess, a problem most frequently encountered in a forelimb. The high incidence of subsolar abscess formation in draft horses can be related to several factors. First, obtaining consistent farrier care may be difficult in many locations, and foot care may be neglected. Second, draft horses often have poor hoof quality and easily develop hoof cracks or severely chipped and broken hoof walls. Clydesdales have particularly poor hoof quality. Many draft horses have dropped soles, predisposing them to bruising and subsolar abscess formation.

A pair of large, good-quality hoof testers provides the simplest method of determining the location of the abscess. Tapping the hoof wall or sole with a hammer (or the hoof testers) can help locate the abscessed area. In horses that recently have been shod or reset, each nail should be examined. An abscess associated with a nail usually develops 5 to 11 days after shoeing. Hoof cracks causing instability of the hoof capsule can cause lameness even though the area of abscessation may have resolved. If a foreign body is lodged in the hoof (nail, glass, or other penetrating object), a fistulogram (contrast radiograph) should be performed. A subsolar abscess can become a life-threatening problem if osteitis of the distal phalanx develops or penetration of the DIP joint, deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT), or navicular bursa occurs. Proper diagnosis is mandatory; otherwise, the long-term prognosis becomes worse.

Once the abscess is located, the sole should be pared with caution, especially if the horse has a dropped sole or has a concomitant full-thickness hoof wall crack. Overzealous sole paring may result in extensive mechanical damage to laminae and loss of hoof wall strength. Adequate drainage is paramount, but removing a large amount of sole is not necessary, even when substantial undermining has occurred. In draft horses, it is important to err toward a conservative approach, at least initially. Thorough flushing of the foot with povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine diacetate solution should be done at least once a day for 3 days or until the drainage has stopped. The foot can be soaked in a saturated solution of magnesium sulfate for 3 to 5 days to reduce inflammation and to aid in drainage. Finding a soak boot large enough for draft horse feet at a reasonable cost is difficult, and I have found an easy solution by using a 1 m length of truck tire inner tubing. The tubing is slipped half its length over the foot, and then up the leg, with the remaining half doubled back up the leg and secured in place by a wrap of choice (Figure 125-1). The tube then can be filled with the soak solution. Draft horses with an uncomplicated subsolar abscess do not need to be treated with systemic antibiotics. However, if cellulitis of the coronary band and pastern region is present, the administration of antibiotics is indicated. Trimethoprim-sulfadiazine (15 mg/kg orally [PO] bid) or ceftiofur sodium (1 mg/kg intravenously [IV] bid or intramuscularly [IM]) is my usual choice. Judicious use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is indicated, but these drugs should not be used for extended periods of time or at levels that may mask a more serious problem. Phenylbutazone, 4 g PO or 2 g IV, on the first day is sufficient. Thereafter, 3 g and then 1 g are given orally on the second and third days, respectively. A tetanus booster should be administered if the horse’s vaccination status is not current or is unknown.

If the horse’s condition is not improved in 3 days, the horse should be reexamined. Radiography and positive contrast fistulography should be performed. A fistulogram is performed using contrast material administered through a Foley catheter. The foot should be held off the ground when contrast medium is infused and should be held up for 2 minutes thereafter. The foot is then placed in a weight-bearing position, and radiographs are obtained immediately. During weight bearing, a fistulous tract often is closed by soft tissue compression. If deeper structures are involved (DIP joint, DDFT, distal phalanx, or navicular bursa), an extensive treatment program is initiated, including bacterial cultures, surgical drainage or curettage, lavage of the affected area, and the administration of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. The initial antibiotic treatment usually includes 20,000 IU of potassium penicillin per kilogram four times a day and 6.6 mg of gentamicin per kilogram once a day. Bacterial culture and susceptibility testing results may require changing the antibiotic regimen.

Hoof Wall Cracks

Forelimb hoof wall cracks were found in 67% of the 260 draft horses examined for lameness of the foot, although not all were the primary cause of the horse’s current problem. Full-thickness hoof wall cracks need to be stabilized when they cause lameness. The crack should be cleaned carefully and curetted, and normal hoof wall should be present on each side of the defect. The technique of dovetailing may provide additional support if hoof repair material is used. Dovetailing is accomplished most easily using a 1-cm ( -inch) round burr on an electric drill and undermining the hoof wall at about a 45-degree angle, leaving a shelf of hoof wall down to the white line on each side of the defect for the full length of the crack. This provides additional surface area for a stronger repair and reduces the likelihood that the repair material will come out. Care must be exercised to avoid damage to the sensitive laminae or to create bleeding during this procedure because these may predispose to abscess formation beneath the repair material. If the horse is initially unshod, a shoe with clips may be sufficient to provide support and to immobilize the defect. Radiator hose clamps and 1-cm long, No. 8 metal screws can be used to stabilize the crack. Because infection is often a problem, the radiator clamp method can be used initially, when filling the defect with repair material is contraindicated. Antibiotic-impregnated repair material has been used, but my success with this material in draft horses has been limited, and my preferred method is a shoe and the radiator clamp and screw combination. It is important to have at least two screws through each piece of clamp and on each side of the defect to add stability. The top clamp should be placed at the proximal limit of the crack. I generally space the clamps 1.9 cm (

-inch) round burr on an electric drill and undermining the hoof wall at about a 45-degree angle, leaving a shelf of hoof wall down to the white line on each side of the defect for the full length of the crack. This provides additional surface area for a stronger repair and reduces the likelihood that the repair material will come out. Care must be exercised to avoid damage to the sensitive laminae or to create bleeding during this procedure because these may predispose to abscess formation beneath the repair material. If the horse is initially unshod, a shoe with clips may be sufficient to provide support and to immobilize the defect. Radiator hose clamps and 1-cm long, No. 8 metal screws can be used to stabilize the crack. Because infection is often a problem, the radiator clamp method can be used initially, when filling the defect with repair material is contraindicated. Antibiotic-impregnated repair material has been used, but my success with this material in draft horses has been limited, and my preferred method is a shoe and the radiator clamp and screw combination. It is important to have at least two screws through each piece of clamp and on each side of the defect to add stability. The top clamp should be placed at the proximal limit of the crack. I generally space the clamps 1.9 cm ( inch) apart, and the number of clamps needed depends on the length, depth, and amount of instability in the crack and on the size of radiator clamp used. The clamps are removed as the defect grows and are replaced if broken. The clamps must be tightened carefully, because lameness from laminar pain will be worse if the clamps are too tight. This problem is corrected by adjusting the clamp with a screwdriver.

inch) apart, and the number of clamps needed depends on the length, depth, and amount of instability in the crack and on the size of radiator clamp used. The clamps are removed as the defect grows and are replaced if broken. The clamps must be tightened carefully, because lameness from laminar pain will be worse if the clamps are too tight. This problem is corrected by adjusting the clamp with a screwdriver.

Laminitis

Laminitis in draft horses is a serious lameness condition, and prognosis for complete resolution often is guarded to unfavorable. Regardless of the cause (e.g., grain overload, colitis, metritis, retained placenta, toxemia), once the pathophysiological process of laminitis is in motion, the end results are similar. The solution to the primary cause often is solved more easily than the secondary problem of laminitis. This is especially true in mares with retained placenta, in which the retained placenta and metritis are solved easily, but secondary complications may be devastating. Many of these mares develop severe laminitis with distal displacement (sinking) of the distal phalanx.

I would like to contrast my observations of draft horses with laminitis to similar conditions in light horses. Laminitis carries a more guarded or unfavorable prognosis in draft horses for many reasons. Our ability to manage secondary problems is less satisfactory in draft horses. Size, when we consider a 1000-kg as opposed to a 400- to 500-kg horse, is the most important factor. Slings are seldom big enough, and hoists or hoist support systems may not be available to lift a draft horse safely. Locating a farrier who will work on a chronically lame draft horse and forge therapeutic shoes on a consistent basis is often difficult. Management of draft horses with myositis, decubital ulcers, infections, pneumonia, and other secondary complications is more difficult and costly. The owner must be informed clearly of cost, and a dedicated team (owner, farrier, and veterinarian) must be assembled to manage these complications. I generally tell clients that at least 1 year will pass before the horse’s level of function can be assessed reasonably.

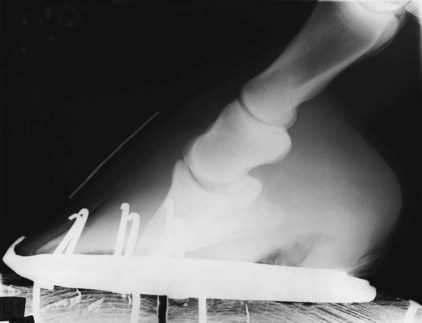

Classification of laminitis is confusing, and I make little attempt to classify laminitis based on chronicity or by using the Obel grading system (see Chapter 34). Regardless of classification used, prognosis for return to function is poor if lameness is severe and persists for longer than 10 days with intensive treatment. In my experience, two major differences exist between draft horses and light horses. First, draft horses develop laminitis more frequently and severely in the hindlimbs. Second, draft horses are more likely to develop distal displacement (sinking) of the distal phalanx once laminitis occurs (Figure 125-2). This latter difference may be related to hoof quality or hoof care in general and the important role that body weight plays in causing distal displacement. In addition, shoeing methods that flair the hoof wall simply to give the impression of a large foot weaken laminar support. Distal displacement can occur in horses with traumatic laminitis without a traditional laminitic episode. Traumatic laminitis and sinking can occur unilaterally, only to then occur weeks to months later in the opposite foot. Traumatic laminitis caused by incorrect shoeing can be reduced greatly or eliminated when proper shoeing is provided on a regular basis.

Fig. 125-2 Lateromedial radiographic image of the front foot of a draft horse mare that had developed laminitis in all four limbs within 24 hours of foaling and retention of the placenta. The radiographic image was obtained 10 days after foaling. The proximal end of the radiodense marker on the dorsal hoof wall is at the level of the coronary band. Both extensive sinking and rotation of the distal phalanx have occurred. Note also the broad radiolucent line in the dorsal hoof wall, the result of laminar necrosis. The mare was managed until the foal was weaned, but humane destruction was ultimately necessary.

Diagnosis of laminitis is not difficult except in draft horses with traumatic laminitis that is slowly progressive, without an acute episode typically seen with laminitis in a light horse. These horses often have a dropped sole (including the frog in many horses), with the entire sole at a level below the hoof wall. Increased digital pulse amplitudes may be missed easily in a draft horse, but hoof tester sensitivity and abnormal stance are important clinical signs. Initial and follow-up radiographs should always be obtained.

Management of draft horses with laminitis is similar to that of light horses, but some precautions need to be taken. Pain amelioration is important but often difficult to achieve. Clydesdales, for instance, are susceptible to gastric and colonic ulcers when treated with phenylbutazone. The Belgian horses that I have treated with phenylbutazone seem less susceptible to ulcers than do Clydesdales. In Clydesdales I seldom if ever administer more than 4 g phenylbutazone PO daily or 3 g IV daily, unless no other alternative is available. The dose should be lowered as quickly as possible, and the high dose should be maintained for a maximum of 5 to 7 days. Although this dose is low based on milligrams per kilogram, Clydesdales have many gastrointestinal complications with higher doses. Flunixin meglumine, meclofenamic acid, and other NSAIDs can be used, but phenylbutazone is the most frequently used and cost-effective drug. Butorphanol tartrate (0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg) can be used with phenylbutazone to lower the necessary dose of NSAIDs. Butorphanol tartrate alone is not a satisfactory analgesic for draft horses with laminitis, but it is useful with NSAIDs, and can be administered three or four times each day.

To provide frog support initially, I use pieces of rubber stall matting, 1.9 cm ( inch) thick. The matting is cut to fit the foot and frog and then secured with fiberglass cast material. To increase thickness, two rubber pads can be glued together. To raise the heel in draft horses with acute laminitis, a hand grinder can be used to make a wedge pad from the rubber mat. I believe raising the heel helps to reduce pain and rotation of the distal phalanx. The heel should be elevated 10 to 14 degrees. The single most important factor in draft horses with laminitis is to avoid excessive paring of the sole. Paring the sole away to make it look like a normal sole is putting the curse of death on draft horses with laminitis. This practice removes natural protection from rotation or sinking, and the sole supports the foot better than anything we can apply externally.

inch) thick. The matting is cut to fit the foot and frog and then secured with fiberglass cast material. To increase thickness, two rubber pads can be glued together. To raise the heel in draft horses with acute laminitis, a hand grinder can be used to make a wedge pad from the rubber mat. I believe raising the heel helps to reduce pain and rotation of the distal phalanx. The heel should be elevated 10 to 14 degrees. The single most important factor in draft horses with laminitis is to avoid excessive paring of the sole. Paring the sole away to make it look like a normal sole is putting the curse of death on draft horses with laminitis. This practice removes natural protection from rotation or sinking, and the sole supports the foot better than anything we can apply externally.

Radical hoof wall resection should be avoided. I recall two horses that were referred after complete dorsal hoof wall resection. In both horses the remaining hoof wall lacked strength, and although one horse was shod and the other was unshod, the distal phalanx rotated and sank through the remaining hoof wall in both horses, which were euthanized. If hoof wall resection is indicated, a shoe with side or quarter clips is applied before the procedure is performed. The entire hoof wall should not be removed at one time, but resection should be staged over 2 to 3 weeks. If the hoof wall spreads and crowding of the side clips occurs or if further rotation or sinking of the distal phalanx is observed, any further resection is delayed. The coronary band should be assessed each day for signs of sinking (depression at the top of the coronary band). Radiography is helpful but does not replace careful physical examination. Horses with subsolar abscesses are treated by drilling small holes (3 to 5 mm) through the hoof rather than by resection of large portions of hoof wall and sole (see Figure 129-1). Two or more holes may need to be placed in the hoof wall or sole to provide adequate drainage and to flush the site. Drilling small holes does not reduce hoof wall strength compared with paring or removing large portions using conventional methods.

Sidebone

Mineralization of the cartilages of the foot (sidebone) is a common radiological finding in draft horses, particularly in the forelimbs, but is an infrequent cause of lameness. Of 113 draft horses with sidebones, 80 had the condition bilaterally in the forelimbs, and 28 horses had it bilaterally in the hindlimbs. Five horses had unilateral involvement. Draft horses with angular limb deformities are more likely to develop sidebone than are horses with normal bone structure. Sidebone is more common in draft horses with poor hoof quality than in horses with normal hooves. Trauma to the heel and quarters and reduced palmar support are contributing factors. If sidebone is the cause of lameness, lameness grade is usually mild (1 to 2 of 5). Lameness is most common in horses 4 to 7 years of age. Sidebone fractures, occurring in older horses, can cause acute lameness. Lameness is usually most apparent when the horse is working on pavement or other hard surfaces. On soft surfaces the hoof can tip or angle, whereas on hard surfaces the bony column cannot move. Lameness is most obvious when horses are working in circles or tight turns.

Lameness associated with sidebone can be difficult to confirm. Palmar or plantar digital nerve blocks usually greatly improve clinical signs, and palmar nerve blocks at the base of the PSBs abolish lameness. Both nerve blocks provide analgesia to numerous other structures that are more frequent causes of lameness, however. Physical examination is more helpful than is diagnostic analgesia. Tapping on the upper one fourth of the hoof wall (while avoiding hitting the coronary band) with hoof testers or a hammer may elicit pain. A lateral or medial wedge test often causes lameness (see Chapter 8). Thermography is valuable in some horses, showing increased temperature in the area of the sidebone. Radiography is of limited value, because the mere presence of mineralization is not conclusive evidence for lameness diagnosis. Nuclear scintigraphy and magnetic resonance imaging have the potential to help to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

Treatment includes rest and hoof care. The hoof should be trimmed level. Hoof strike should be evaluated dynamically (how it strikes the ground during movement) rather than by just viewing the hoof in a static position. Vertical and parallel grooving may allow the hoof wall to expand and may reduce pressure, but I have not found grooving highly rewarding. The horse should have stall rest or small paddock confinement for 4 to 8 weeks and NSAID therapy. The foot must be balanced properly before the horse resumes a normal exercise program. Fractures associated with large sidebones may be accompanied by OA of the DIP joint. Rarely the PIP joint is involved. Surgical management of draft horses with sidebone fractures often is unrewarding, and I do not recommend it unless conservative management efforts have failed. Conservative management includes an extended period of stall rest (8 to 12 weeks) and then small, level paddock exercise for 6 to 8 months. Healing as shown on radiographs may require extensive time, and even then the fracture still may be evident, surrounded by proliferative exostosis. Unilateral palmar digital neurectomy also can be performed. This will provide relief in most horses unless there is concurrent OA of the DIP or PIP joints.

Quittor

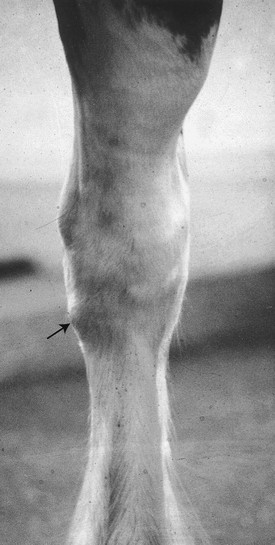

Quittor is defined as a chronic infectious condition associated with one of the cartilages of the foot. A mixed bacterial infection causing chronic or recurrent drainage at or near the coronary band is most common (Figure 125-3). Trauma is the most common cause of the condition referred to as necrosis of the cartilage. Wire cuts and wounds incurred from large calks on the shoes when horses are working in harness or being transported are common histories. Quittor is considerably less common today than it once was.

Surgical management is the only option, because scar tissue and limited circulation preclude successful conservative management with local or systemic antibiotics. Excision of necrotic cartilage and scar tissue is best. Samples should be submitted for aerobic and anaerobic bacterial culture and susceptibility testing. Standing surgery can be performed, but I prefer to use general anesthesia, which reduces the chance of the DIP joint being penetrated, improves the ability to provide hemostasis, and provides maximal restraint during surgery. A tourniquet at the level of the fetlock joint provides excellent surgical hemostasis, and as a precaution I always administer prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics before surgery. The DIP joint occasionally is opened, and although penetration does not necessarily indicate surgical failure, an open joint alters the postoperative management protocol. If necrotic material (cartilage or scar tissue) extends distal to the coronary band, adequate distal drainage and flushing require drilling a hole in the hoof wall.1

Osteitis of the Distal Phalanx

Many draft horses have flat soles and bear substantial weight on the sole and thus are prone to sole bruising and osteitis of the distal phalanx. The condition is most prevalent in the forelimbs and often is associated with improper shoeing or lack of proper hoof care. Draft horses with osteitis of the distal phalanx may assume a stance similar to that seen with traumatic laminitis. Hoof tester examination may be helpful to differentiate these conditions. A laminitic horse is most sensitive immediately dorsal to the apex of the frog in line with the dorsal third of the toe. With osteitis of the distal phalanx, hoof tester pain response usually is less severe and more likely involves the sole in general. Soles may be pink or red, showing indications of bruising, and lameness is worse on hard surfaces or gravel. Mildly affected horses warm out of the lameness, but in horses with severe pain, lameness increases as exercise continues. Radiographs can be difficult to interpret, and a definitive diagnosis is best reached using nuclear scintigraphy, observing increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the distal phalanx. Management includes the judicious administration of NSAIDs and corrective shoeing. The sole should be protected and minimally pared. Pads frequently are used initially but may be counterproductive in the long run, because the sole has a tendency to become soft and lose thickness. Pads are needed for the first few shoe changes but then should be removed, and the sole should be hardened. To harden the sole, a common mixture referred to as sole paint (composed of equal parts of 7% iodine, buffered formalin, and liquid phenol) is applied. This solution is applied to the sole once each day for 3 to 5 days or until the sole becomes hard. Overzealous application can cause the sole to become too hard. Paddock rest for 45 to 60 days is given. If shorter rest periods are given, recurrence is common. Hard, frozen, or rough surfaces should be avoided.

Canker

Canker is not common but is a difficult problem to solve. Canker is proliferative pododermatitis of the frog that may extend to undermine the sole and heel bulbs. The condition can occur in one or all feet and has no predilection for forelimbs or hindlimbs. Often horses are thought to have nonresponsive thrush, but later when the problem persists, canker is diagnosed (Figure 125-4). Canker is seen more commonly in draft horses than in light horses, a fact that may reflect differences in hoof care and environment or simply may represent a breed predisposition. Two clinical signs that differentiate canker from thrush are a foul odor (necrotic) and the presence of granulation-like tissue that bleeds easily when manipulated (Figure 125-5). Lameness is highly variable depending on the severity and number of feet involved. Once the superficial layer of tissue is removed, bleeding is often profuse. Creamy exudate is typical initially, especially if the owner has initiated treatment with caustic preparations.

Fig. 125-4 Draft horse foot showing the typical appearance of thrush complicated by canker beneath the superficial layer of the frog.

Fig. 125-5 Chronic canker with proliferative granulation tissue. Infected granulation tissue has undermined the sole and heel.

Successful treatment of canker requires patience on the part of the owner and the veterinarian because recurrence is common. The application of a hospital plate shoe is critical, because this shoe allows for long-term treatment and protects the sole. It is important to note that pressure on the sole appears beneficial to healing, similar to that seen with granulation tissue at any site. Hospital plate shoes reduce the cost associated with daily care and management of a bandage. The shoe allows the horse to be exercised. The hospital plate shoe is made and fitted to the foot, and then the foot is blocked. A tourniquet is placed at the level of the fetlock joint, because bleeding during debridement is often profuse. Complete debridement of all abnormal proliferative tissue is often not possible and in fact may be counterproductive, because aggressive debridement may expose uninvolved deep tissue. Dry gauze sponges are packed to apply pressure on the frog and sole when the plate is replaced. Metronidazole appears to be the best topical agent, but I have used tetracycline and sulfapyridine powder successfully. The dressing should be changed daily for the first 10 to 14 days and then as needed. Debridement often needs to be repeated several times. Long-term treatment is necessary, and the owner needs to be prepared to provide it. Caustic compounds are not effective and in fact may worsen the condition. In the final stages of healing, when cornification of the frog is complete, caustic agents may be applied. Sole paint is applied to the sole for 8 to 10 days before the hospital plate shoe is removed. Horses are administered trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (15 mg/kg) for 3 weeks starting the day before initial debridement. Penicillin (20,000 IU/kg IM) is also effective, but oral antimicrobial agents are administered more easily.

Osteoarthritis of the Proximal and Distal Interphalangeal Joints, Ringbone

OA of the PIP or DIP joint was diagnosed in 26 draft horses in my series.

Ringbone has been described classically as being periarticular or articular in nature. The prognosis for draft horses with articular ringbone is worse than for those with the periarticular form. Pulling horses (heavy loads) are affected most commonly, especially in the hindlimbs. OA of the PIP and DIP joints appears to occur with similar frequency, because in 26 horses, 11 had PIP, 10 had DIP, and 5 had PIP and DIP joint involvement. Horses with OA of the PIP joint remained serviceably sound for 2.6 years, whereas horses with OA of the DIP joint or of both joints were serviceably sound for only 11 months. Early diagnosis appears to be an important criterion for an improved prognosis, and reducing workload, instituting corrective shoeing, and providing medical management can make a substantial difference in delaying the progression of OA.

Draft horses with short, upright pasterns are predisposed to OA of the PIP and DIP joints, and other factors such as angular limb deformities, toed-in or toed-out conformation, hoof imbalance, and trauma may play a substantial role. Horses required to work on pavement are predisposed to OA of the PIP and DIP joints. Proliferative periarticular changes often result from lacerations or wire cuts. Horses with moderate-to-severe lameness have obvious enlargement of the pastern or coronary band area and heat. The degree of lameness varies from grade 1 to 5, and it worsens with lower limb flexion or after rotation of the digit. Rotation causes a substantial positive response if collateral ligaments are involved in horses with the periarticular form. In horses with OA of the DIP joint, palmar digital nerve blocks generally result in substantial improvement in lameness score. Thorough examination of the foot must be done to eliminate other potential causes of lameness. If the diagnosis is unclear after radiological examination, intraarticular analgesia should be performed. In horses with OA of the PIP joint, palmar digital nerve blocks may provide some improvement in lameness score, but palmar nerve blocks at the level of the PSBs are needed to improve lameness substantially. Intraarticular analgesia can also be used.

Management depends on when the diagnosis is first made. Draft horses with OA and mild lameness should be given rest in a small level paddock for 4 months. I do not use stall rest unless horses are very active, because I have had greater success allowing the horse to walk in a confined area. Hoof imbalance should be corrected, and the horse should be shod with flat shoes without calks, toe grabs, or borium. I recommend oral glucosamine or chondroitin sulfate supplementation or intramuscular injection of a polysulfated glycosaminoglycan (PSGAG). I also inject the joints with a corticosteroid and hyaluronan. Initial and follow-up radiographic examinations are recommended. If the horse is sound and radiological changes do not progress, the horse is put back into a light exercise program, whereas if radiological changes worsen, additional rest and injections are given. Many horses with OA perform for extended periods of time without recurrence of lameness. Horses with severe OA of the PIP or DIP joints have an unfavorable prognosis for athletic use. Medical management is of little benefit, and although spontaneous fusion of the PIP joint may occur, giving an accurate time estimate of when this may occur is difficult. Spontaneous fusion of the DIP joint seldom occurs. Surgical arthrodesis of the PIP joint can be performed by using bone plates or the three-screw technique with 5.5-mm bone screws (see Chapter 35). A half-limb cast is placed for at least 4 to 6 weeks after surgery. In draft horses the surgical procedure is more difficult than in light horses because the joints are large, removing articular cartilage is difficult, and horses may have difficulty with recovery from general anesthesia. Draft horses in general do not recover well from extended periods (>2 hours) of general anesthesia. The surgical procedure can be long, in particular if there is substantial periarticular new bone formation and fibrosis. Implants can break because of the large size of a draft horse. Because of this, I have used an alternative technique of drilling across the joint with a 4.5- or 5.5-mm drill bit and then applying a half-limb cast without using implants. In horses with substantial periarticular bone proliferation or fibrosis, this technique is my method of choice. Intraoperative radiographs are mandatory to ensure proper placement of the drill bit within the joint. I drill at three to five sites in a fan-shaped pattern from each side of the joint to destroy as much articular cartilage as possible. Breaking a drill bit in the joint is possible, and if this happens, removing the bit generally is not worth the extra time required. The palmar digital artery, vein, and nerve must be avoided during this procedure. A half-limb cast encompassing the foot is applied and maintained for 12 to 16 weeks. Advantages of this technique over those involving implants are that this technique is faster, requires shorter anesthesia periods, and requires no major skin incisions, and implant failure is not a concern. Pain control must be used to maintain reasonable comfort to avoid contralateral laminitis, which is always a concern.

Metacarpophalangeal (Fetlock) Joint Lameness

Problems associated with the fetlock joint are less frequent in draft horses than in other breeds, and most result from direct trauma. Fetlock joint problems plague horses that perform at speed, and therefore draft horses seldom have lameness in this region. Sesamoiditis does occur in draft horses and usually results from suspensory desmitis and insertional injury at the level of the PSB. Sesamoiditis is more common in the hindlimbs than in the forelimbs. An unusual problem of the fetlock joint in young draft horses is osteochondritis dissecans (OCD).

Splints

Exostoses of the second and fourth metacarpal or metatarsal bones (splints) most commonly affect the second metacarpal bone, as in light horses. In 84 draft horses diagnosed with splints, 71 horses had forelimb involvement. Lameness associated with true splint (tearing of the interosseous ligament) is not common in draft horses. Lameness caused by splints is most prominent in the first 2 to 3 weeks after the condition is first recognized and usually resolves with 6 to 8 weeks of rest. Because draft horses do not perform at speed or change direction quickly, splints do not cause long-term lameness. Splints can result from interference injury from the contralateral limb, a problem that usually is corrected by proper shoeing and trimming. Local infiltration of local anesthetic solution in the region of the splint may be performed if the diagnosis is in question. Although a splint may be painful during palpation, missing a problem in the more distal aspect of a limb is easy; therefore diagnostic analgesia should be performed distal to the splint before local infiltration. Radiographs should be obtained to check for a fracture.

To manage a draft horse with lameness resulting from a splint, I administer NSAIDs for 5 to 7 days and recommend stall rest. If the condition is acute, I use cold water therapy or ice boots for 20 to 30 minutes twice daily and apply support wraps. The horse should be handwalked for 10 minutes twice daily. In horses with chronic splints, I recommend a sweat (50/50 mixture of glycerin and alcohol) for 7 to 10 days. Paddock exercise can be given for 12 hours each day. A total rest period of 60 to 90 days is usually adequate. I avoid overzealous treatment with topical or internal blisters.

Fractures of the splint bones are rare but usually involve the fourth metatarsal bone (MtIV), and they often occur from kick wounds. These fractures often are comminuted and usually infected, because owners do not seek veterinary attention until 2 to 3 weeks after injury. Severe lameness often is not seen or is short lived, so the owner usually is not concerned until drainage starts. If the tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint is involved and infected, the prognosis for return to original use is unfavorable. Many of these fractures heal if horses are given rest and treated with antibiotics. If the articular surface of the TMT joint is not involved, displacement of fragments is minimal, and if the horse is not an athlete, horses with this injury can be treated conservatively. Standing curettage of a draining tract and removal of sequestra can be accomplished in many horses with use of sedation and local analgesia. A culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing are performed, and the horse is placed on appropriate antibiotics for 3 to 4 weeks; the outcome is often satisfactory. For economic reasons this method also is chosen by some owners for horses intended for athletic use. However, I believe the problem is best treated surgically in those horses that are expected to be athletes. Surgical removal of the distal fractured segment of the MtIV is recommended occasionally, and horses usually have a good prognosis. If greater than 80% of the total length of the MtIV is removed, I use a screw to stabilize the proximal fragment. I do not like placing a screw into an area of known infection if I can avoid doing so. In horses with substantial displacement or a fracture involving the articular surface, internal fixation to realign the fracture is indicated, if the injury is less than 3 weeks old. Fractures older than 3 weeks old can be difficult to realign because callus formation occurs quickly.

Tendonitis and Suspensory Desmitis

Digital flexor tendonitis and suspensory desmitis are not as common in the draft horse as one might expect. Of 45 horses examined for these soft tissue problems, the distribution of these combined soft tissue injuries between the forelimbs and hindlimbs was similar, in contrast to most sports horses. Suspensory desmitis is more common in hindlimbs and often is seen with sesamoiditis. Tendonitis and suspensory desmitis are more common in draft horses that pull heavy loads or weighted sleds. Clinical signs include heat, pain, swelling, and lameness, and diagnosis is usually straightforward. Horses with hindlimb proximal suspensory desmitis may have more subtle clinical signs, and diagnostic analgesia is usually necessary. In horses with early forelimb superficial digital flexor tendonitis, the anastomosing branch of the palmar nerves may be enlarged and sensitive to palpation before the tendon itself shows clinical abnormalities. Ultrasonographic examination should be performed.

Management of draft horses with tendonitis and suspensory desmitis is similar to that in light horses. Ultrasonographic examination, rest, and a staged return to work are important. I am an advocate of percutaneous tendon or suspensory ligament splitting under ultrasonographic guidance in draft horses. The surgery can be accomplished in a standing horse, using local analgesia and sedation, thus avoiding the need for general anesthesia. Prognosis is guarded to favorable in draft horses with forelimb tendonitis and suspensory desmitis. Draft horses with hindlimb injury, however, have a guarded to unfavorable prognosis, especially if horses are used for pulling heavy loads. Broodmares with chronic, severe suspensory desmitis must be given special attention during late pregnancy because of weight gain. These mares should be housed on level surfaces and alone. Situations that require the mare to move quickly to avoid an aggressive pasture mate or cause the mare to slip while going over rough terrain should be avoided. Muddy or slick footing also should be avoided. Stall rest, although advantageous for healing of the suspensory ligament, is avoided, because these broodmares usually develop substantial ventral edema.

Other Forelimb Lameness

Other causes of forelimb lameness are unusual. Upper limb lameness usually is caused by direct trauma and is not the result of athletic use. Carpal, elbow, or shoulder joint lameness is not common. I have examined only 13 draft horses with carpal lameness. Various manifestations of osteochondrosis are seen in the elbow and shoulder joints.

Sweeny, a neuromuscular disorder thought to be associated with injury of the suprascapular nerve, does occur with some frequency in draft horses. Muscle atrophy may not be obvious for weeks to months, depending on the extent of the injury. Sweeny may result from acute direct trauma, but in draft horses insidious trauma from a collar is the most common cause. This is especially true of poorly fitting collars, or old and worn collars in which the padding is no longer adequate. Collars of inadequate size often are used on today’s large-sized draft horses. Some draft horses with Sweeny continue to perform adequately despite muscle atrophy. Diagnosis is made by observing muscle atrophy over the scapula, especially affecting the supraspinatus muscle. Lameness is most likely functional and not related to pain, because horses cannot extend the shoulder joint normally. In some horses, however, the shoulder joint actually may subluxate when the horse is walking or especially turning in a circle. Subluxation results more frequently from external trauma from being kicked or from running into a solid object rather than from collar injury and may involve additional nerve injury.

Management of horses with acute trauma of the shoulder area includes the administration of NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and dimethyl sulfoxide and performance of physical therapy. A water hose with a hard stream of water can be useful for physical therapy. Liniments, massage, handheld muscle stimulators, and heating pads can be useful physical therapeutic modalities as well. The administration of dimethyl sulfoxide (0.3 g/kg sid IV for 3 to 5 days) is recommended in the acute phase. Prognosis is difficult to assess, but if improvement is not seen in the first 6 to 8 weeks after diagnosis, prognosis becomes less favorable. I have not attempted scapular notch resection in draft horses, but knowing the complications associated with the procedure in light horses leads me to hesitate recommending it.

Unusual Signs Consistent with Lameness Caused by Mange Mites

In the United Kingdom a clinically significant incidence of mange occurs in draft breed horses.2 Draft horses often are presented for evaluation of presumed lameness because of a stiff, stilted gait and with abnormal stamping of the limbs to the ground. In these horses careful clinical evaluation reveals areas of dermatitis, but this condition can be confused easily with musculoskeletal pain. I have not seen this to be a problem in draft horses in the United States.

Hindlimb Lameness

Hindlimb lameness occurs frequently in draft horses, and the most common cause is lameness associated with the tarsus (hock joint). Draft horses in general have a predisposition to develop tarsitis, and lameness does not seem to be related to use. The custom of lowering the inside wall of the hoof and attempting to turn the hocks, a shoeing change thought to improve the horse’s pulling ability, may predispose a draft horse to tarsitis. To my knowledge, however, this has never been proved in a controlled study. Draft horse shoes often have a large calk on the heel of the lateral branch of the shoe, increasing torque and shear stress on the entire limb. Heel calks are especially detrimental in horses that work on hard surfaces, because the calk does not sink into the surface, thus putting even greater stress on the limb. This method of shoeing causes a flaring of the lateral hoof wall and predisposes the hooves to separation and breakdown of laminae. Even if this method of shoeing is abandoned, at least 12 to 18 months are required for the foot to return to normal.

Tarsus

Draft horses with hock lameness show a variety of clinical signs. The perceived problems by the owner also vary considerably. The horse may stop pulling or may rest its butt on the stall wall when in the barn. Breeding stallions may be reluctant to mount a mare, and when mounted, they may be unable to maintain erection. Horses may be reluctant to back up, back up in crooked fashion, and have difficulty going up and down inclines. The horse may take short strides in harness or may have a change in attitude, sometimes biting other horses. Because the prevalence of hock joint lameness is high, carefully considering this region when evaluating a draft horse with hindlimb lameness is always wise.

Diagnosis may be straightforward, based on clinical signs, or may require diagnostic analgesia to pinpoint the problem. Upper limb flexion tests in draft horses appear to be slightly more accurate as an indicator of hock lameness than the same tests are in light horses, but false-negative results do occur. Pulling the medial splint bone with the fingers (Churchill test) with the limb in flexion also may be of value. The horse may show a positive response while standing, or lameness may be exacerbated after this maneuver is performed. When the horse is trotting, careful attention is given to the vertical movement of the wings of the ilium (hip or pelvic hike), but if the problem is bilateral, a pelvic hike may not be obvious. Stride length may be shortened when the horse is viewed from the side, and when evaluated from behind or in front, horses have a tendency to swing the limb toward the midline and then place the limb laterally as it strikes the ground. Horses may scuff the toes because of the low arc of limb flight. Bony exostosis on the dorsal medial aspect of the hock joint may be obvious or absent.

Tarsocrural effusion, or bog spavin, is observed commonly in draft horses. This clinical observation often does not correlate with the source of pain. Even if osteochondrosis is suspected or confirmed, intraarticular analgesia always should be performed (Figure 125-6). Although present, OCD fragments may not be the major source of pain, and surgical removal of these fragments may not resolve lameness. Often in draft horses with OCD there is severe tarsocrural effusion, which may improve but is unlikely to resolve even after arthroscopic removal of the offending fragments (Editors). Arthroscopic removal of OCD fragments is often less rewarding in adult horses. In draft horses younger than 2 years of age, arthroscopic removal of OCD fragments is more likely to resolve lameness, however. The decision to perform surgery is based on the level of performance, cosmetic considerations related to joint distention, location of the lesion, and, most important, whether lameness resolves with tarsocrural analgesia. Horses with OCD lesions located more distally on the trochlear ridges of the talus have a more favorable prognosis than those with lesions located on the proximal aspect. Horses with OCD lesions associated with the cranial aspect of the intermediate ridge of the tibia have a favorable prognosis if lesions are removed early before chronic synovitis or capsulitis occurs. With only a limited number of horses from which to draw experience, lesions seemingly occur more frequently on the lateral trochlear ridge of the talus (tibial tarsal bone) than in any other location in a draft horse. OCD lesions associated with the cranial aspect of the intermediate ridge of the tibia are also quite common in draft horses (Editors).

Fig. 125-6 Dorsomedial-plantarolateral oblique radiographic image of a hock of a yearling draft horse. The radiograph was deliberately underexposed to highlight the extensive osteochondrosis lesion involving the distal half of the lateral trochlear ridge of the talus.

Lameness associated with OA of the centrodistal and TMT joints is common. Intraarticular analgesia is often necessary, although some veterinarians medicate these joints and assess the clinical response to this treatment. I prefer to perform intraarticular analgesia and consider management options once a definitive diagnosis has been made, however. In my opinion, conservative management should be attempted before corticosteroids are used. I block the TMT and the centrodistal joints first with the horse standing squarely on each limb. In draft horses with exostoses on the medial aspect of the tarsus (bone spavin), confidently blocking the centrodistal joint may be difficult. Two-percent mepivacaine hydrochloride (7 to 12 mL) is injected into each joint using a 20- to 22-gauge, 2.5- to 4-cm needle in the standard locations (see Chapter 10). In most draft horses a twitch is adequate for restraint. Radiographs should be obtained, but unfortunately they are unreliable in confirming the diagnosis of OA. In some draft horses with substantial radiological changes, lameness may originate elsewhere, whereas in some horses with minor or equivocal radiological changes, severe lameness from early OA of these joints is diagnosed. Radiological examination helps to select management options and to determine prognosis, however.

Management of a draft horse with OA of the distal hock joints includes physical and medical and surgical options. Correction of any shoeing or trimming problems should be performed before any other treatment. The foot is balanced in a medial-to-lateral direction according to conformation to achieve a level foot strike. My definition of a level foot strike is that the foot lands evenly when contacting the ground during movement. I remove the large calks and trailers that often are placed on the lateral branch of the shoes. If the horse is not going to be worked for a period, I prefer to shoe the horse without any special trim (calks, toe grabs, or inside rims). The dorsal aspect of the shoe is placed at the white line, and the toe is rasped back to the level of the shoe. Squared-toe shoes also can be used. The heels of the shoe should extend far enough behind to support the plantar aspect of the heel completely. In some horses slight heel elevation improves breakover and comfort. If the lateral hoof wall is flared, it must be rasped at each shoeing, and the lateral branch of the shoe gradually must be adjusted to conform properly to a more normal hoof shape. If borium is needed for traction on hard surfaces, it should be placed so that it provides a level surface on the bottom of the shoe. Uneven stress from borium points may cause hoof wall cracks. Usually, using six to 10 spots of borium on the shoe adequately supports the foot and also provides adequate traction.

Medical management may include oral supplementation, intramuscular administration of PSGAGs, and intravenous administration of hyaluronan. NSAIDs are recommended at the time of shoeing changes, but long-term use of NSAIDs is usually not a solution in the management of chronic distal hock joint pain. Chronic administration often results in gastrointestinal ulceration and additional problems such as colic or colitis. Horses with distal hock joint pain can be given 2 to 3 g of phenylbutazone daily. Intraarticular injection with hyaluronan alone has limited value in draft horses with OA of the distal hock joints, and I prefer to use hyaluronan with methylprednisolone acetate. If there are economic restrictions, the corticosteroid is most important and can be injected alone. The dose of these compounds is similar to that used in the light horse and is not based necessarily on body weight. I increase the corticosteroid dose by about 25% using methylprednisolone acetate (100 mg) in each of the centrodistal and the TMT joints. If treating bog spavin, I use methylprednisolone acetate (120 mg) and hyaluronan (40 mg). I seldom if ever use triamcinolone acetonide in draft horses, because of a concern about laminitis induction and the fact that I often am injecting several joints simultaneously.

Cunean tenectomy is used in some horses, especially those that have obvious enlargement on the medial aspect of the hock (Figure 125-7). Cunean tenectomy is accomplished in a standing horse using local analgesia and sedation. Horses often are put back into work once the skin sutures are removed, 12 to 14 days after surgery.

Stifle Joint

Draft horses have long been thought to have more stifle joint lameness than do light horses, but when reviewing the records of 745 draft horse lameness examinations, only 10 horses had primary lameness of the stifle joint. Perhaps long ago, when draft horses were used daily to pull heavy loads, the frequency of stifle lameness may have been far greater than it is today. Of these 10 horses, three had bilateral idiopathic effusion of the femoropatellar joint. One horse had bilateral subchondral bone cysts of the medial femoral condyles, one had upward fixation of the patella, and five had trauma from kick injuries. Poor conformation and extended stall confinement predispose some draft horses to upward fixation of the patella. Emaciated horses or those with substantial weight loss also are predisposed to the condition. I make every attempt to correct upward fixation of the patella by using conservative management including foot care, improving muscle tone or conditioning, and improving nutritional intake. Raising the heel often alleviates the problem, and block wedges to raise the angle of the hind feet 6 to 10 degrees are needed. Heel elevation is reduced gradually as the problem is rectified. Improved muscle tone and exercise are beneficial, as is avoiding prolonged periods of stall confinement. Backing exercise strengthens the quadriceps muscles and is a useful form of physical therapy. Internal blisters, injected at the origin and insertion of the patellar ligaments, may cause mild fibrosis and thus tighten the joint. This treatment is used less frequently now than in the past because the preparations need to be special ordered. I seldom if ever elect medial patellar desmotomy as my initial treatment. If conservative management is unsuccessful, desmotomy needs to be performed. The procedure should be done in the standing horse and not under general anesthesia and should be done with a sharp, strong-backed bistoury. This procedure should not be attempted in a draft horse with an ordinary scalpel handle and blade, because the risk of the blade breaking during the surgery is real. Medial patellar desmoplasty (splitting) would be a suitable alternative to desmotomy in draft horses (see Chapter 48 [Editors]).

Shivers

Shivers is considered a progressive, degenerative neuromuscular disease predominantly affecting draft horses or other large-breed horses (see Chapter 48). Various causes have been suggested, including immune-mediated disease following viral infection or strangles and exposure to organophosphates. Polysaccharide storage myopathy has been put forth as a possible cause, but like previous proposed causes, this one may go by the wayside. Clinical signs include an involuntary jerking or twitching most frequently affecting the hindlimbs and the tail. A reflex-like maximum degree of flexion can be seen. Clinical signs often are noticed first by the farrier, because manually picking up the hindlimb frequently stimulates the jerking movements. Signs may be most obvious when the horse first starts to walk, or is backed up or is turned sharply. On occasion, twitching of the muzzle, lips, and ears and forelimb involvement occur. The condition may improve with rest but usually returns when the horse is put back into work.

Currently, no effective treatment is available. Shivers has been confused with stringhalt in some horses, and the surgical procedure, lateral digital flexor tenectomy, has been performed erroneously. Muscle biopsy to check for polysaccharide storage myopathy and treatment with high-fat, low-carbohydrate diets may be warranted, but definitive proof that polysaccharide storage myopathy is the cause of shivers may be difficult to substantiate. Horses still can be worked, but often owners elect to use them sparingly.

Lameness of Foals, Weanlings, and Yearlings

Young draft horses require careful monitoring and early attention to lameness conditions. Lameness is often multifactorial and is related to nutrition, genetics, and environment. Early diagnosis and management of lameness appear more critical in draft horse foals than in light horse foals. Often the size and strength of draft horse foals gives the erroneous impression that they can overcome many problems.

Infectious Arthritis

Infectious arthritis is common in draft horse foals and may be related to a high frequency of umbilical problems. Umbilical hernia, umbilical infection, and patent urachus are more common in draft horse foals than in light horses. Careful examination and treatment of the umbilicus at birth is mandatory, and the umbilicus should be monitored closely for a minimum of 3 weeks. Compared with light horse foals, draft horse foals are often slower to stand and nurse after birth, leading to many infectious processes. Owner education is important, not only in assisting slow foals up to nurse but also in careful, daily evaluation of joints. Early and aggressive management of infectious arthritis and umbilical remnant infections should be performed (see Chapters 65 and 128).

Developmental Orthopedic Disease

Draft horses are affected by all of the various manifestations of developmental orthopedic disease (DOD), including flexural deformities, epiphysitis and physitis, osteochondrosis, angular limb deformities, and vertebral malformations (wobbler syndrome). A multifactorial cause is suspected, including nutrition (calcium/phosphorus ratios and trace mineral levels) and hereditary factors (certain bloodlines have a high prevalence). Hereditary factors are complex and include high growth rate, feed deficiency conversion, milk production, and individual horse size.

Physitis and Epiphysitis and Flexural Deformities

Physitis and epiphysitis and flexural deformities are closely related and seldom if ever a single problem. These conditions are seen over a wide age range from 6 weeks to 24 months, but peak occurrence is in foals 4 to 12 months of age. When raising large horses, owners have a tendency to overfeed, resulting in high-energy rations, fast growth, and nutritional stress, all of which include the possibility of DOD. My experience with some 300 draft horse foals suggests a distinct correlation between the frequency of DOD and nutritional management. Foals having the highest frequency of DOD were fed free-choice high-quality alfalfa hay, approximately 0.015 kg of feed per kilogram of body weight per day of a 16% protein grain ration, and two vitamin-mineral supplements. Foals were fed in groups of six to 10 in 5- to 6-acre paddocks. Group feeding allowed the aggressive eater to consume far more than the prescribed amount of grain, and of course hay was fed free choice. None of the foals was thin or malnourished, but numerous foals were obese. Overweight foals, yearlings, and 2-year-olds do not exercise properly, a fact that exacerbates problems associated with excess ration. Under these conditions, two to four foals per group were affected with DOD each year.

To correct this problem, the nutritional program was revamped. The owner accepted the fact that yearling size would be slightly less than previously attained, but that DOD would occur less frequently. Anecdotally, buyers of yearlings from this group had complained in previous years that 2-year-olds had become lame when training had started. The nutrition was changed as follows. The hay ration was given at a 50/50 mixture of alfalfa to timothy. Hay was fed at a rate of 0.015 kg per kilogram of body weight per day, or the amount the foals could consume in about 16 hours. The grain ration was reduced to approximately 0.01 kg per kilogram of body weight per day of a 14% protein ration. Only one vitamin-mineral supplement was given. Foals were grouped according to size, age, and disposition and were monitored closely and checked every 2 weeks by the farm veterinarian. Changes in conformation (becoming upright in the pastern and fetlock) or enlargement (heat and pain) of the growth plates were noted.

Any foal with a change in the pastern or fetlock angle (developing more upright conformation), joint effusion, or physitis was treated immediately. Stall rest was given for 7 to 10 days, the feed intake was reduced, and the foal subsequently was given controlled exercise in a small paddock. Foals were fed only timothy hay, and the grain ration was reduced to 0.002 kg per kilogram of body weight per day. They were placed on phenylbutazone (2.2 mg/kg bid for 3 consecutive days and then every other day for 3 more days). They were maintained in this environment until the problem resolved. Any hoof imbalance or growth abnormality was treated. A 60% decrease in DOD was noted the first year, and now that farm management has become more attentive to noticing early signs of DOD, the frequency of this complex of diseases is now less than 10%.

Osteochondritis Dissecans and Osteochondrosis

In my experience, osteochondrosis is observed more commonly in draft horse foals than in light horse foals. In draft horse foals the tarsocrural and femoropatellar joints are affected most commonly. Any joint can be affected, including the cervical vertebrae. Horses with osteochondrosis show varying degrees of lameness from 1 to 4 of 5 degrees. Lameness is less frequent with osteochondrosis lesions of the tarsocrural joint than with osteochondrosis of the stifle. Loose OCD fragments in the femoropatellar joint should be removed as soon as possible. Arthroscopic surgery does not guarantee success but improves the prognosis for athletic use. In my experience, draft horses have a more guarded prognosis for future soundness with osteochondrosis of the stifle than do light horses. I am unsure if this is related simply to the size of the horse or the amount of pulling many of these draft horses are expected to do, but only about 50% of draft horses are sound after surgery. Early diagnosis and surgical management improve prognosis considerably. In some foals without loose OCD fragments, conservative management has resulted in a favorable outcome. Large OCD defects involving the lateral trochlear ridge of the femur have healed based on radiological examination, but this process may take up to 6 months to occur.