Chapter 71Injuries of the Accessory Ligament of the Deep Digital Flexor Tendon

Anatomy

In the forelimbs the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon (ALDDFT) is a substantial structure, similar in size to the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT). The ALDDFT continues the common palmar ligament of the carpus, originating principally from the palmar aspect of the third carpal bone.1 Proximally the ALDDFT is broad and rectangular in cross-section; farther distally it becomes narrower and thicker and blends with the DDFT in the middle one third of the metacarpal region. Fibrous bundles run from the lateral border of the ALDDFT to the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) in the proximal half of the metacarpal region, and these predispose the horse to develop adhesions between the ALDDFT and the SDFT in horses with severe superficial digital flexor tendonitis or severe desmitis of the ALDDFT. The ALDDFT forms the dorsal wall of the carpal canal, within which is the carpal synovial sheath, which is interspersed between the DDFT and its accessory ligament.

In the hindlimbs the size of the ALDDFT varies extremely, but it is generally smaller than in the forelimb and rarely more than half the thickness of the DDFT. The ligament is usually symmetrical in the left and right hindlimbs of an individual horse. A recent postmortem study showed that the ALDDFT was absent in 6% of 165 hindlimbs and was occasionally a bifid structure.2

A forelimb ALDDFT has a low modulus of elasticity and a moderate strength to rupture, whereas the DDFT has a high modulus of elasticity and a strength to rupture that is more than three times that of the forelimb ALDDFT. In the forelimb the ALDDFT is loaded during the late stance phase, during extension of the digital joints,1 or when landing over a fence.3 The ALDDFT prevents overstretching of the DDFT by passively carrying the load during maximal extension of the distal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints. The ALDDFT also functions to facilitate carpal extension when the limb is loaded.1 During flexion of the limb the ALDDFT is relaxed completely, and active muscle contraction results in the DDFT sliding proximally within the carpal sheath. The role of the ALDDFT in the hindlimb is less clear.

Desmitis of the ALDDFT usually occurs in forelimbs4-9 but occasionally is recognized as a cause of hindlimb lameness.4,10-13 In forelimbs desmitis may occur alone4,7 as an acute injury or may develop secondarily to previous severe tendonitis of the SDFT. In the latter case the SDFT is enlarged substantially and wraps around the medial and lateral margins of the DDFT. Adhesions develop between adjacent structures. In horses with chronic, severe desmitis of the ALDDFT, additional injury may occur to the adjacent DDFT.7,8 A flexural deformity of the metacarpophalangeal or metatarsophalangeal joint may develop after severe injury to the ALDDFT.4,9 Occasionally a flexural deformity of the metatarsophalangeal joint develops in one or both hindlimbs without a history of lameness, but ultrasonography reveals chronic architectural changes in the ALDDFT.11-13 The flexural deformity may be relieved by desmotomy of the ALDDFT, provided that contracture of periarticular soft tissues has not already occurred.

Pathogenesis

Degenerative aging changes take place in the ALDDFT of forelimbs, and these may be a substantial predisposing factor in the development of desmitis. The amount of fibrillar collagen and number of large collagen fibers in the ALDDFT decrease with increasing age.14 In a study of mechanical properties of the ALDDFT in relationship to age, failure forces of the ALDDFT of older horses were significantly lower than those of the ALDDFT in younger horses.15 Fibrillar ruptures developed in the ALDDFT of old horses at forces and strains that were approximately half those of the forces inducing total failure in young horses. It has been suggested that fibrillar rupture occurs at relatively low strains in older horses and that repetitive microtrauma may lead to clinical desmitis.14,15

The incidence of desmitis of the ALDDFT is rather different from that of other tendonous and ligamentous injuries. Injuries occur more often in horses older than 8 years of age.4-6 The incidence in Thoroughbreds is comparatively low (rare in the Standardbred), and therefore this is an unusual injury in event horses or racehorses, except in older steeplechasers. Desmitis is a relatively common injury in ponies (see Chapter 126) and crossbred horses, including pleasure horses.4,5 The incidence in Warmblood horses is also high.6 Desmitis occurs in older show jumpers (see Chapter 115), especially Grand Prix–level horses,12 in older dressage horses,12 and also sometimes in young, extravagantly moving dressage horses (see Chapter 116). Desmitis is generally a unilateral forelimb injury (Figure 71-1), although occasionally it occurs bilaterally, and is a rare cause of hindlimb lameness.

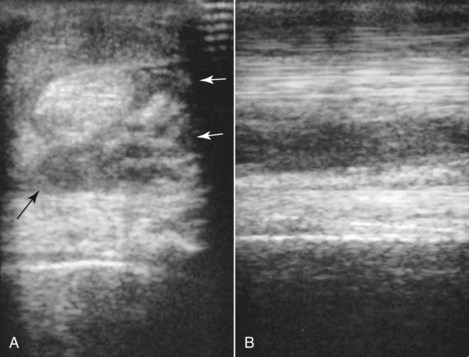

Fig. 71-1 A, Transverse ultrasonographic image of the palmar metacarpal soft tissue structures, 11 cm distal to the accessory carpal bone, of an 8-year-old Grand Prix show jumper. Medial is to the left. The accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon (ALDDFT) is considerably enlarged (arrows) and diffusely hypoechogenic, with focal anechoic areas dorsomedially. B, Longitudinal ultrasonographic image of the palmar metacarpal sort tissues in zone 2A of the same horse as in A. Proximal is to the left. There is a diffuse reduction in echogenicity of the ALDDFT and poor fiber pattern.

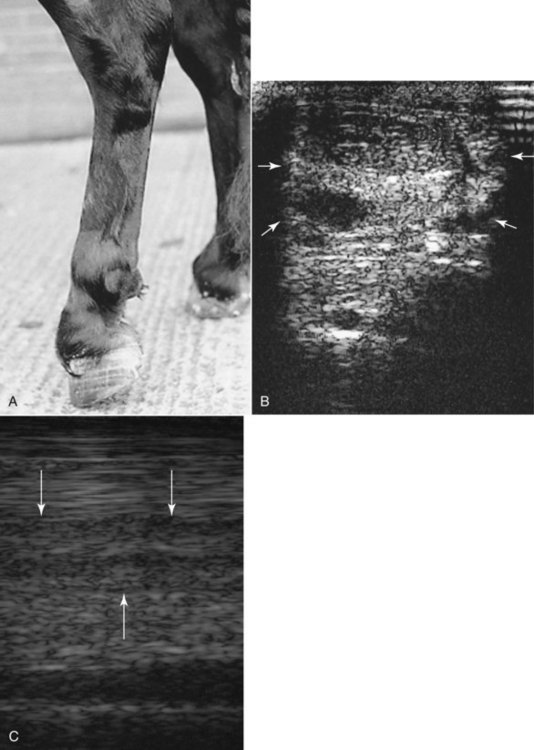

In hindlimbs, desmopathy of the ALDDFT has been seen most frequently in cob-type breeds11-13 and Quarter Horses or Quarter Horse crosses,16 even in some horses or ponies of a comparatively young age, and does not appear to have been induced traumatically in all horses. In some of these horses the condition has been bilateral, developing simultaneously or sequentially in each hindlimb. Desmopathy frequently has been associated with a tendency to stand with the fetlock of the affected limb partially flexed (Figure 71-2), resulting in the development of a flexural deformity. The condition also has been recognized together with swelling on the plantar aspect of the pastern, associated with concurrent desmitis of the straight or oblique sesamoidean ligaments.11

Fig. 71-2 A, A 6-year-old Fell pony with a flexural deformity of the left hind fetlock associated with chronic desmopathy of the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon (ALDDFT). The pony was unable to place the heel of the left hind foot on the ground. Even when the pony was heavily sedated, extending the left hind fetlock was not possible. Firm enlargement on the plantar aspect of the pastern associated with desmitis of the straight distal sesamoidean ligament was also apparent. Similar abnormalities had developed in the right hindlimb approximately 12 months previously. B, Transverse ultrasonographic image of the plantar metatarsal soft tissues approximately 10 cm distal to the tarsometatarsal joint. Medial is to the left. The ALDDFT is enlarged considerably (arrows), and there is a large anechogenic lesion centrally. C, Longitudinal ultrasonographic image in zone 2A. Proximal is to the left. There is marked loss of fiber pattern in the ALDDFT (arrows).

History and Clinical Signs

There is usually an acute-onset moderate-to-severe lameness during exercise.4-6 A show jumper may pull up lame after jumping a large fence or after a water jump.12 Swelling develops rapidly in the proximal one third of the metacarpal region, dorsal to the SDFT. Determining by palpation whether the DDFT or accessory ligament is enlarged can be difficult, but injuries of the DDFT in this area are unusual. Some horses develop desmitis secondary to previous superficial digital flexor tendonitis, and in these horses separating the margins of the SDFT from the ALDDFT often is difficult.

Clinical signs include swelling, heat, pain on palpation, and lameness. The horse may stand with slight elevation of the heel and flexion of the metacarpophalangeal joint. Some degree of swelling often persists, even after long-term convalescence. In horses with reinjury, new swelling may be only slight, and careful palpation is required to identify a focus of pain. Occasionally there are no localizing clinical signs, but lameness is improved by palmar and palmar metacarpal (subcarpal) nerve blocks or abolished by median and ulnar nerve blocks. Lesions of the ALDDFT that were not detectable ultrasonographically have been identified with magnetic resonance imaging.17,18 However, great care must be taken in interpretation because in normal horses the ALDDFT may have higher signal intensity than the DDFT or the SDFT in some image sequences.19,20 There also may be bands of lower and higher signal intensity reflecting histological variation in infrastructure. Focal lesions have also been identified ultrasonographically at the origin of the ALDDFT on the palmar aspect of the third carpal bone.18

Some horses with desmitis in a hindlimb have acute-onset lameness associated with localized swelling. In sports horses injury may be localized to the proximal metatarsal region, resulting in subtle edematous swelling in the proximomedial aspect, whereas in general-purpose riding horses injury is usually further distal in the metatarsal region, with more obvious enlargement of the ALDDFT. However, some horses do not have an acute-onset lameness but have an insidious onset of stiffness and a tendency to stand with the fetlock semiflexed, progressing to inability to load the heel of the affected limb. This may be unilateral or bilateral.11 Teenage cob-types and British native pony breeds appear particularly at risk. Careful palpation may reveal enlargement of the ALDDFT, but the thick skin of these types of horse may prohibit accurate palpation.

Ultrasonography

Diagnosis is usually confirmed by ultrasonography (see Figures 71-1 to 71-3). The transducer should be focused initially at the depth of the ALDDFT, which should be examined in transverse and longitudinal planes. Comparative images of the contralateral limb also should be obtained. If the transducer has a built-in standoff, this may create artifacts at the level of the ALDDFT. Some lesions are localized to the lateral or, less commonly, the medial margin of the ALDDFT, and these lesions may be missed unless the limb is evaluated from the lateral and medial aspects respectively, preferably using a standoff pad.

Fig. 71-3 A, Transverse ultrasonographic image of the left hindlimb of a 12-year-old Thoroughbred–cross event horse with acute-onset right hindlimb lameness. Medial is to the left. The image was acquired from the plantaro-medial aspect of the limb at 5 cm distal to the tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint. The accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon (ALDDFT) is narrow from dorsal to plantar (arrow), well separated from the suspensory ligament (SL), and more echogenic than either the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) or the SL. B, Transverse ultrasonographic image of the right hindlimb obtained 5 cm distal to the TMT joint. Medial is to the left. Clinically there was palpable edematous swelling in the proximal metatarsal region, medially more than laterally, between the SL and the DDFT. The ALDDFT is enlarged (arrows) with diffuse decrease in echogenicity involving almost the entire ligament, with an anechogenic area medially. There is no longer space between the ALDDFT and the SL.

The ALDDFT is normally the most echogenic of the palmar metacarpal (plantar metatarsal) soft tissue structures, and its borders are well defined. In some ponies the ALDDFT is less echogenic than the DDFT and suspensory ligament.

With forelimb injury, the ALDDFT invariably is enlarged and tends to expand around the borders of the DDFT, especially laterally. With severe injuries, it may be necessary to move the transducer medially and laterally to evaluate properly the margins of the ligament. Often definition of the borders of the ligament is lost, with a diffuse reduction in echogenicity of the ligament, sometimes with anechogenic areas. Occasionally a large proportion of the ligament is anechogenic. Central core lesions are comparatively rare, although acentric lesions restricted to the lateral border may occur, with the majority of the ligament appearing relatively normal. The dorsal border of the DDFT should be inspected carefully for evidence of concurrent injury, especially in horses with recurrent injury. In horses in which injury has been sustained secondary to previous superficial digital flexor tendonitis or in which desmitis of the ALDDFT is recurrent, the SDFT also should be evaluated for evidence of simultaneous recurrent injury or recent injury. The transducer should be focused on the SDFT, using a standoff. Adhesions between the ALDDFT and adjacent structures may be best identified in longitudinal images obtained with the limb not bearing weight. With passive flexion and extension of the fetlock it should be possible to see independent movement of the SDFT, DDFT, and ALDDFT, provided that no clinically significant adhesion formation has occurred. Concurrent injury of the suspensory ligament is seen rarely in association with desmitis of the ALDDFT. Occasionally, periligamentar echogenic tissue develops because of tearing of surrounding fascia.

In horses with chronic desmitis, when substantial enlargement of the ALDDFT occurs, with or without enlargement of the SDFT, the cross-sectional area of the DDFT often is reduced significantly.12

In acute hindlimb injuries in the proximal metatarsal region the ALDDFT should be evaluated from the plantaromedial aspect of the limb (see Figure 71-3). In horses that initially had an enlarged ALDDFT and inability to load the heel of the affected limb, the ALDDFT usually is enlarged, with poorly demarcated borders, and is diffusely hypoechogenic. Examination can be challenging in cob-types with very thick skin and a dense hair coat, especially if there are areas of dermal fibrosis. It is often necessary to use a transducer with lower frequency (e.g., 8 MHz) and to turn up the gain controls. It is important to be aware of the normal architecture of the ALDDFT because frequently the entire cross-sectional area of the ALDDFT may be diffusely hypoechoic, and if the appearance is bilaterally symmetrical such lesions may be overlooked. Other structures in the metacarpal or metatarsal regions and pastern should be examined, because lesions have been identified simultaneously in the SDFT16 and the distal sesamoidean ligaments.12

Treatment

In horses with acute, first-time primary injuries of the ALDDFT, conservative treatment is usually satisfactory, but the prognosis is more guarded for horses with longer-term injuries when horses have continued to exercise. The horse should be restricted to box rest and controlled walking exercise for a minimum of 3 months and then should be reevaluated ultrasonographically. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs should be given if the horse will not load the limb normally at rest to avoid development of a secondary flexural deformity of the metacarpophalangeal joint. Any foot imbalance should be corrected.

Improvement in echogenicity generally is seen more quickly than in comparable injuries of the SDFT. Box rest and controlled walking exercise should continue until the ligament is of similar echogenicity to the DDFT in transverse and longitudinal images. Progress should be monitored monthly after the first reevaluation 3 months after injury.

Horses that are allowed uncontrolled turnout in the initial 3-month period tend to have persistent clinical signs, and lesions persist ultrasonographically. Treatment with β-aminopropionitrile fumarate could be considered, especially in horses that have sustained a recurrent injury; however, no published reports of its efficacy in treating this condition are available, although successful results have been achieved, and a licensed product is no longer available.12 There are also anecdotal reports of successful treatment with fresh bone marrow, platelet-rich plasma, or mesenchymal stem cell therapy. I have treated six horses with chronic forelimb injuries of the ALDDFT with mesenchymal stem cells and the results to date have been extremely promising.

Differences in the reported success of conservative treatment of horses with forelimb injuries of the ALDDFT have been substantial.4-6 A number of factors, including the chronicity of the injury when therapy was first instituted and the type of horse, probably account for this disparity in success. I4 reported complete functional recovery in 76% of 27 horses and ponies, whereas McDiarmid5 reported only 43% success, and Van den Belt, Becker, and Dik6 reported only 18%. Most of the horses in the series of Van den Belt, Becker, and Dik were large Warmbloods, whereas my series4 included a large number of ponies. In my experience early recognition and aggressive treatment are key factors to a successful outcome. In a series of 13 horses with acute hindlimb injury in the mid-metatarsal region, 73% returned to full athletic function.11 These were mostly pleasure riding horses. Proximal hindlimb lesions in sports horses have not been well documented; in my experience four of seven horses have returned to their former athletic function.

In horses with chronic, recurrent desmitis, in horses with evidence of adhesions between the ALDDFT and the SDFT, or in those that tend to stand with the fetlock flexed, surgical treatment by desmotomy of the ALDDFT may be indicated.4,7 The treated ligament heals by scar tissue that is inferior in strength to normal ligament, but the ligament will be longer, and this may reduce the strain on it21 and thus reduce the risks of reinjury. Experimental removal of a full-thickness piece of the ALDDFT of 1 cm length resulted in long-term repair by scar tissue, in which orientation of the collagen was random. The healed ligaments were 1 cm longer than control ligaments and enlarged in cross-sectional area. The functional characteristics, force, and elongation at failure reached 80% of control values.22

The number of published long-term follow-up results for treatment of horses with chronic desmitis of the ALDDFT by desmotomy is limited. In my experience desmotomy has been successful in horses with chronic desmitis of the ALDDFT alone, but in those with concurrent superficial digital flexor tendonitis, or a flexural deformity of the metacarpophalangeal joint that cannot be corrected passively, the results have been disappointing. Horses with concurrent superficial digital flexor tendonitis have been relieved of evidence of resting pain, but restoring these horses to full athletic function has not been possible.

Horses with insidious onset of desmopathy of the ALDDFT of one or both hindlimbs have a poor prognosis with conservative treatment.11 Treatment by desmotomy or desmectomy also resulted in persistent lameness in the majority, with preexisting contracture of the fetlock being an extremely poor prognostic indicator.

The prognosis depends on the chronicity of the injury and evidence of any concurrent injury to the DDFT or SDFT. Horses with acute injuries have a better prognosis than those with chronic injuries. Horses with recurrent injuries have a more guarded prognosis, especially if lesions are identified in the DDFT. Horses with lesions of the ALDDFT that have developed secondary to superficial digital flexor tendonitis have the most guarded prognosis, especially if any evidence of flexural deformity exists.