Comparison of Systemic Versus Musculoskeletal Pain Patterns

Table 3-2 provides a comparison of the clinical signs and symptoms of systemic pain versus musculoskeletal pain using the typical categories described earlier. The therapist must be very familiar with the information contained within this table. Even with these guidelines to follow, the therapist’s job is a challenging one.

In the orthopedic setting, physical therapists are very aware that pain can be referred above and below a joint. So, for example, when examining a shoulder problem, the therapist always considers the neck and elbow as potential NMS sources of shoulder pain and dysfunction.

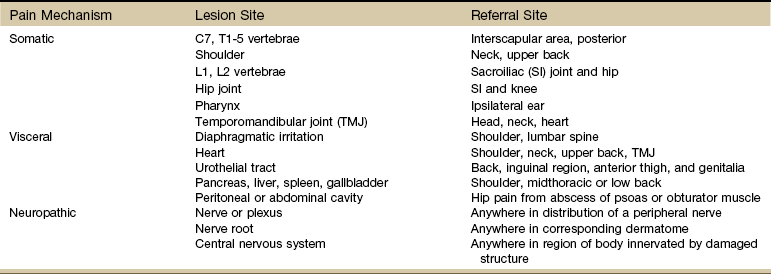

Table 3-8 reflects what is known about referred pain patterns for the musculoskeletal system. Sites for referred pain from a visceral pain mechanism are listed. Lower cervical and upper thoracic impairment can refer pain to the interscapular and posterior shoulder areas.

Likewise, shoulder impairment can refer pain to the neck and upper back, while any condition affecting the upper lumbar spine can refer pain and symptoms to the SI joint and hip. When examining the hip region, the therapist always considers the possibility of an underlying SI or knee joint impairment and so on.

If the client presents with the typical or primary referred pain pattern, he or she will likely end up in a physician’s office. A secondary or referred pain pattern can be very deceiving. The therapist may not be able to identify the underlying pathology (in fact, it is not required), but it is imperative to recognize when the clinical presentation does not fit the expected pattern for NMS impairment.

A few additional comments about systemic versus musculoskeletal pain patterns are important. First, it is unlikely that the client with back, hip, SI, or shoulder pain that has been present for the last 5 to 10 years is demonstrating a viscerogenic cause of symptoms. In such a case, systemic origins are suspected only if there is a sudden or recent change in the clinical presentation and/or the client develops constitutional symptoms or signs and symptoms commonly associated with an organ system.

Secondly, note the word descriptors used with pain of a systemic nature: knifelike, boring, deep, throbbing. Pay attention any time someone uses these particular words to describe the symptoms.

Third, observe the client’s reaction to the information you provide. Often, someone with a NMS problem gains immediate and intense pain relief just from the examination provided and evaluation offered. The reason? A reduction in the anxiety level.

Many people have a need for high control. Pain throws us in a state of fear and anxiety and a perceived loss of control. Knowing what the problem is and having a plan of action can reduce the amplification of symptoms for someone with soft tissue involvement when there is an underlying psychologic component such as anxiety.

On the other hand, someone with cancer pain, viscerogenic origin of symptoms, or systemic illness of some kind will not obtain relief from or reduction of pain with reassurance. Signs and symptoms of anxiety are presented later in this chapter.

Fourth, aggravating and relieving factors associated with NMS impairment often have to do with change in position or a change (increased or decreased) in activity levels. There is usually some way the therapist can alter, provoke, alleviate, eliminate, or aggravate symptoms of a NMS origin.

Pain with activity is immediate when there is involvement of the NMS system. There may be a delayed increase in symptoms after the initiation of activity with a systemic (vascular) cause.

For the orthopedic or manual therapist, be aware that an upslip of the innominate that does not reduce may be a viscero-somatic reflex. It could be a visceral ligamentous problem. If the problem can be corrected with muscle energy techniques or other manual therapy intervention, but by the end of the treatment session or by the next day, the correction is gone and the upslip is back, then look for a possible visceral source as the cause.4

If you can reduce the upslip, but it does not hold during the treatment session, then look for the source of the problem at a lower level. It can even be a crossover pattern from the pelvis on the other side.4

Aggravating and relieving factors associated with systemic pain are organ dependent and based on visceral function. For example, chest pain, neck pain, or upper back pain from a problem with the esophagus will likely get worse when the client is swallowing or eating.

Back, shoulder, pelvic, or sacral pain that is made better or worse by eating, passing gas, or having a bowel movement is a red flag. Painful symptoms that start 3 to 5 minutes after initiating an activity and go away when the client stops the activity suggest pain of a vascular nature. This is especially true when the client uses the word “throbbing,” which is a descriptor of a vascular origin.

Clients presenting with vascular-induced musculoskeletal complaints are not likely to come to the therapist with a report of cardiac-related chest pain. Rather, the therapist must be alert for the man over age 50 or postmenopausal woman with a significant family history of heart disease, who is borderline hypertensive. New onset or reproduction of back, neck, temporomandibular joint (TMJ), shoulder, or arm pain brought on by exertion with arms raised overhead or by starting a new exercise program is a red flag.

Leaning forward or assuming a hands and knees position sometimes lessens gallbladder pain. This position moves the distended or inflamed gallbladder out away from its position under the liver. Leaning or side bending toward the painful side sometimes ameliorates kidney pain. Again, for some people, this may move the kidney enough to take the pressure off during early onset of an infectious or inflammatory process.

Finally, notice the long list of potential signs and symptoms associated with systemic conditions (see Table 3-2). At the same time, note the lack of associated signs and symptoms listed on the musculoskeletal side of the table. Except for the possibility of some ANS responses with the stimulation of trigger points, there are no comparable constitutional or systemic signs and symptoms associated with the NMS system.

Characteristics of Viscerogenic Pain

There are some characteristics of viscerogenic pain that can occur regardless of which organ system is involved. Any of these by itself is cause for suspicion and careful listening and watching. They often occur together in clusters of two or three. Watch for any of the following components of the pain pattern.

Gradual, Progressive, and Cyclical Pain Patterns

Gradual, progressive, and cyclical pain patterns are characteristic of viscerogenic disease. The one time this pain pattern occurs in an orthopedic situation is with the client who has low back pain of a discogenic origin. The client is given the appropriate intervention and begins to do his/her exercise program. The symptoms improve, and the client completes a full weekend of gardening, 18 holes of golf, or other excessive activity.

The activity aggravates the condition, and the symptoms return worse than before. The client returns to the clinic, gets firm reminders by the therapist regarding guidelines for physical activity, and is sent out once again with the appropriate exercise program. The “cooperate—get better—then overdo” cycle may recur until the client completes the rehabilitation process and obtains relief from symptoms and return of function.

This pattern can mimic the gradual, progressive, and cyclical pain pattern normally associated with underlying organic pathology. The difference between a NMS pattern of pain and symptoms and a visceral pattern is the NMS problem gradually improves over time, whereas the systemic condition gets worse.

Of course, beware of the client with discogenic back and leg pain who suddenly returns to the clinic completely symptom free. There is always the risk of disc herniation and sequestration when the nucleus detaches and becomes a loose body that may enter the spinal canal. In the case of a “miraculous cure” from disc herniation, be sure to ask about the onset of any new symptoms, especially changes in bowel and bladder function.

Constant Pain

Pain that is constant and intense should raise a red flag. There is a logical and important first question to ask anyone who says the pain is “constant.” Can you think what this question might be?

It is surprising how often the client will answer “No” to this question. While it is true that pain of a NMS origin can be constant, it is also true there is usually some way to modulate it up or down. The client often has one or two positions that make it better (or worse).

Constant, intense pain in a client with a previous personal history of cancer and/or in the presence of other associated signs and symptoms raises a red flag. You may want to use the McGill Home Recording Card to assess the presence of true constant pain (see Fig. 3-7).

It is not necessary to have the client complete an entire week’s pain log to assess constant pain. A 24- to 48-hour time period is sufficient. Use the recording scale on the right indicating pain intensity and medications taken (prescription and OTC).

Under item number 3, include sexual activity. The particulars are not necessary, just some indication that the client was sexually active. The client defines “sexually active” for him or herself, whether this is just touching and holding or complete coitus. This is another useful indicator of pain levels and functional activity.

Remember to offer clients a clear explanation for any questions asked concerning sexual activity, sexual function, or sexual history. There is no way to know when someone will be offended or claim sexual harassment. It is in your own interest to behave in the most professional manner possible.

There should be no hint of sexual innuendo or humor injected into any of your conversations with clients at any time. The line of sexual impropriety lies where the complainant draws it and includes appearances of misbehavior. This perception differs broadly from client to client.4

Finally, the number of hours slept is helpful information. Someone who reports sleepless nights may not actually be awake, but rather, may be experiencing a sleep disturbance. Cancer pain wakes the client up from a sound sleep. An actual record of being awake and up for hours at night or awakened repeatedly is significant (Case Example 3-6). See the discussion on Night Pain earlier in this chapter.

Physical Therapy Intervention “Fails”

If a client does not get better with physical therapy intervention, do not immediately doubt yourself. The lack of progression in treatment could very well be a red flag symptom. If the client reports improvement in the early intervention phase but later takes a turn for the worse, it may be a red flag. Take the time to step back, reevaluate the client and your intervention, and screen if you have not already done so (or screen again if you have).

If painful, tender, or sore points (e.g., TrPs, Jones’ points, acupuncture/acupressure points/Shiatsu) are eliminated with intervention then return quickly (by the end of the individual session), suspect visceral pathology. If a tender point comes back later (several days or weeks), you may not be holding it long enough.4

Bone Pain and Aspirin

There is one odd clinical situation you should be familiar with, not because you are likely to see it, but because the physicians may use this scenario to test your screening knowledge. Before the advent of nonaspirin pain relievers, a major red flag was always the disproportionate relief of bone pain from cancer with a simple aspirin.

The client who reported such a phenomenon was suspected of having osteoid osteoma and a medical workup would be ordered. The mechanism behind this is explained by the fact that salicylates in the aspirin inhibit the pain-inducing prostaglandins produced by the bone tumor.

When conversing with a physician, it is not necessary for the therapist to identify the specific underlying pathology as a bone tumor. Such a conclusion is outside the scope of a physical therapist’s practice.

However, recognizing a sign of something that does not fit the expected mechanical or NMS pattern is within the scope of our practice and that is what the therapist can emphasize when communicating with medical doctors. Understanding this concept and being able to explain it in medical terms can enhance communication with the physician.

Pain Does Not Fit the Expected Pattern

In a primary care practice or under direct access, the therapist may see a client reporting back, hip, or SI pain of systemic or visceral origin early on in its development. In these cases, during early screening, the client often presents with full and pain-free ROM. Only after pain has been present long enough to cause splinting and guarding, does the client exhibit biomechanical changes (Box 3-9).

Screening for Emotional and Psychologic Overlay

Pain, emotions, and pain behavior are all integral parts of the pain experience. There is no disease, illness, or state of pain without an accompanying psychologic component.4 This does not mean the client’s pain is not real or does not exist on a physical level. In fact, clients with behavioral changes may also have significant underlying injury.116 Physical pain and emotional changes are two sides of the same coin.117

Pain is not just a physical sensation that passes up to consciousness and then produces secondary emotional effects. Rather, the neurophysiology of pain and emotions are closely linked throughout the higher levels of the CNS. Sensory and emotional changes occur simultaneously and influence each other.90

The sensory discriminative component of pain is primarily physiologic in nature and occurs as a result of nociceptive stimulation in the presence of organic pathology. The motivational-affective dimension of pain is psychologic in nature subject to the underlying principles of emotional behavior.99

The therapist’s practice often includes clients with personality disorders, malingering, or other psychophysiologic disorder. Psychophysiologic disorders (also known as psychosomatic disorders) are any conditions in which the physical symptoms may be caused or made worse by psychologic factors.

Recognizing somatic signs of any psychophysiologic disorder is part of the screening process. Behavioral, psychologic, or medical treatment may be indicated. Psychophysiologic disorders are generally characterized by subjective complaints that exceed objective findings, symptom development in the presence of psychosocial stresses, and physical symptoms involving one or more organ systems. It is the last variable that can confuse the therapist when trying to screen for medical disease.

It is impossible to discuss the broad range of psychophysiologic disorders that comprise a large portion of the physical therapy caseload in a screening text of this kind. The therapist is strongly encouraged to become familiar with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR)51 to understand the psychologic factors affecting the successful outcome of rehabilitation.

However, recognizing clusters of signs and symptoms characteristic of the psychologic component of illness is very important in the screening process. Likewise, the therapist will want to become familiar with nonorganic signs indicative of psychologic factors.118-120

Three key psychologic components have important significance in the pain response of many people:

Anxiety, Depression, and Panic Disorder

Psychologic factors, such as emotional stress and conflicts leading to anxiety, depression, and panic disorder, play an important role in the client’s experience of physical symptoms. In the past, physical symptoms caused or exacerbated by psychologic variables were labeled psychosomatic.

Today the interconnections between the mind, the immune system, the hormonal system, the nervous system, and the physical body have led us to view psychosomatic disorders as psychophysiologic disorders.

There is considerable overlap, shared symptoms, and interaction between these emotions. They are all part of the normal human response to pain and stress90 and occur often in clients with serious or chronic health conditions. Intervention is not always needed. However, strong emotions experienced over a long period of time can become harmful if excessive.

Depression and anxiety often present with somatic symptoms that may resolve with effective treatment of these disorders. Diagnosis of these conditions is made by a medical doctor or trained mental health professional. The therapist can describe the symptoms and relay that information to the appropriate agency or individual when making a referral.

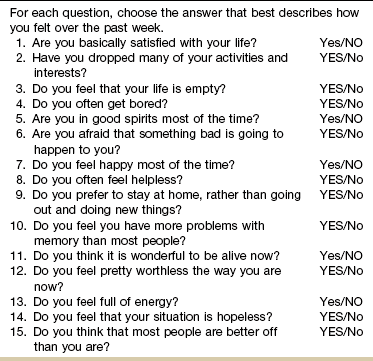

Anxiety

Anyone who feels excessive anxiety may have a generalized anxiety disorder with excessive and unrealistic worry about day-to-day issues that can last months and even longer.

Anxiety amplifies physical symptoms. It is like the amplifier (“amp”) on a sound system. It does not change the sound; it just increases the power to make it louder. The tendency to amplify a broad range of bodily sensations may be an important factor in experiencing, reporting, and functioning with an acute and relatively mild medical illness.121

Keep in mind the known effect of anxiety on the intensity of pain of a musculoskeletal versus systemic origin. Defining the problem, offering reassurance, and outlining a plan of action with expected outcomes can reduce painful symptoms amplified by anxiety. It does not ameliorate pain of a systemic nature.122

Musculoskeletal complaints, such as sore muscles, back pain, headache, or fatigue, can result from anxiety-caused tension or heightened sensitivity to pain. Anxiety increases muscle tension, thereby reducing blood flow and oxygen to the tissues, resulting in a buildup of cellular metabolites.

Somatic symptoms are diagnostic for several anxiety disorders, including panic disorder, agoraphobia (fear of open places, especially fear of being alone or of being in public places) and other phobias (irrational fears), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalized anxiety disorders.

Anxious persons have a reduced ability to tolerate painful stimulation, noticing it more or interpreting it as more significant than do nonanxious persons. This leads to further complaining about pain and to more disability and pain behavior such as limping, grimacing, or medication seeking.

To complicate matters more, persons with an organic illness sometimes develop anxiety known as adjustment disorder with anxious mood. Additionally, the advent of a known organic condition, such as a pulmonary embolus or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), can cause an agoraphobia-like syndrome in older persons, especially if the client views the condition as unpredictable, variable, and disabling.

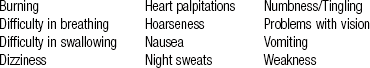

According to C. Everett Koop, the former U.S. Surgeon General, 80% to 90% of all people seen in a family practice clinic are suffering from illnesses caused by anxiety and stress. Emotional problems amplify physical symptoms such as ulcerative colitis, peptic ulcers, or allergies. Although allergies may be inherited, anxiety amplifies or exaggerates the symptoms. Symptoms may appear as physical, behavioral, cognitive, or psychologic (Table 3-9).

TABLE 3-9

*Chest pain associated with anxiety accounts for more than half of all emergency department admissions for chest pain. The pain is substernal, a dull ache that does not radiate, and is not aggravated by respiratory movements but is associated with hyperventilation and claustrophobia. See Chapter 17 for further discussion of chest pain triggered by anxiety.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) quickly assesses the presence and severity of client anxiety in adolescents and adults ages 17 and older. It was designed to reduce the overlap between depression and anxiety scales by measuring anxiety symptoms shared minimally with those of depression.

The BAI consists of 21 items, each scored on a 4-point scale between 0 and 3, for a total score ranging from 0 to 63. Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety. The BAI is reported to have good reliability for clients with various psychiatric diagnoses.123,124

Both physiologic and cognitive components of anxiety are addressed in the 21 items describing subjective, somatic, or panic-related symptoms. The BAI differentiates between anxious and nonanxious groups in a variety of clinical settings and is appropriate for all adult mental health populations.

Depression

Once defined as a deep and unrelenting sadness lasting 2 weeks or more, depression is no longer viewed in such simplistic terms. As an understanding of this condition has evolved, scientists have come to speak of the depressive illnesses. This term gives a better idea of the breadth of the disorder, encompassing several conditions, including depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, and seasonal affective disorder (SAD).

Although these conditions can differ from individual to individual, each includes some of the symptoms listed. Often the classic signs of depression are not as easy to recognize in people older than 65, and many people attribute such symptoms simply to “getting older” and ignore them.

Anyone can be affected by depression at any time. There are, in fact, many underlying physical and medical causes of depression (Box 3-10), including medications used for Parkinson’s disease, arthritis, cancer, hypertension, and heart disease (Box 3-11). The therapist should be familiar with these.

For example, anxiety and depressive disorders occur at a higher rate in clients with COPD, obesity, diabetes, asthma, arthritis, cancer, and cardiovascular disease.125,126 Other risk factors for depression include lifestyle choices such as tobacco use, physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyle, and binge drinking.127 There is also a link between depression and heart risks in women. Depressed but otherwise healthy postmenopausal women face a 50% higher risk of dying from heart disease than women who are not depressed.128

People with chronic pain have three times the average risk of developing depression or anxiety, and clients who are depressed have three times the average risk of developing chronic pain.129

Almost 500 million people are suffering from mental disorders today. One in four families has at least one member with a mental disorder at any point in time, and these numbers are on the increase. Depressive disorders are the fourth leading cause of disease and disability. Public health prognosticators predict that by 2020, clinical depression will be the leading cause of medical disability on earth. Adolescents are increasingly affected by depression.130

The reasons for the increased incidence are speculative at best. Rapid cultural change around the world, worldwide poverty, and the aging of the world’s population (the incidence of depression and dementia increases with age) have been put forth by researchers as possibilities.131-133

Others suggest better treatment of the symptoms has resulted in fewer suicides.134 Researchers think that genes may play a role in a person’s risk of developing depression.135-137 In earlier times, adults who had this genetic link may have committed suicide before bearing children and passing the gene on. Today, with better treatment and greater longevity, people with major depressive disorders may unwittingly pass the disease on to their children.138

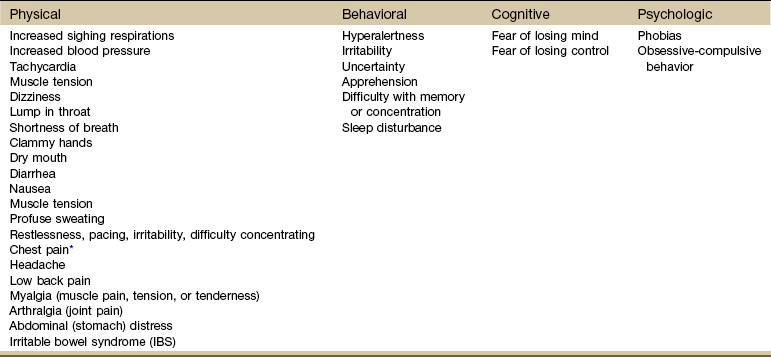

New insights on depression have led scientists to see clinical depression as a biologic disease possibly originating in the brain with multiple visceral involvements (Table 3-10). One error in medical treatment has been to recognize and treat the client’s esophagitis, palpitations, irritable bowel, heart disease, asthma, or chronic low back pain without seeing the real underlying impairment of the CNS (CNS dysregulation: depression) leading to these dysfunctions.134,139,140

TABLE 3-10

Systemic Effects of Depression

Data from Smith NL: The effects of depression and anxiety on medical illness, Sandy, Utah, 2002, Stress Medicine Clinic, School of Medicine, University of Utah.

A medical diagnosis is necessary because several known physical causes of depression are reversible if treated (e.g., thyroid disorders, vitamin B12 deficiency, medications [especially sedatives], some hypertensives, and H2 blockers for stomach problems). About half of clients with panic disorder will have an episode of clinical depression during their lives.

Depression is not a normal part of the aging process, but it is a normal response to pain or disability and may influence the client’s ability to cope. Whereas anxiety is more apparent in acute pain episodes, depression occurs more often in clients with chronic pain.

The therapist may want to screen for psychosocial factors, such as depression, that influence physical rehabilitation outcomes, especially when a client demonstrates acute pain that persists for more than 6 to 8 weeks. Screening is also important because depression is an indicator of poor prognosis.141

In the primary care setting, the physical therapist has a key role in identifying comorbidities that may have an impact on physical therapy intervention. Depression has been clearly identified as a factor that delays recovery for clients with low back pain. The longer depression is undetected, the greater the likelihood of prolonged physical therapy intervention and increased disability.141,142

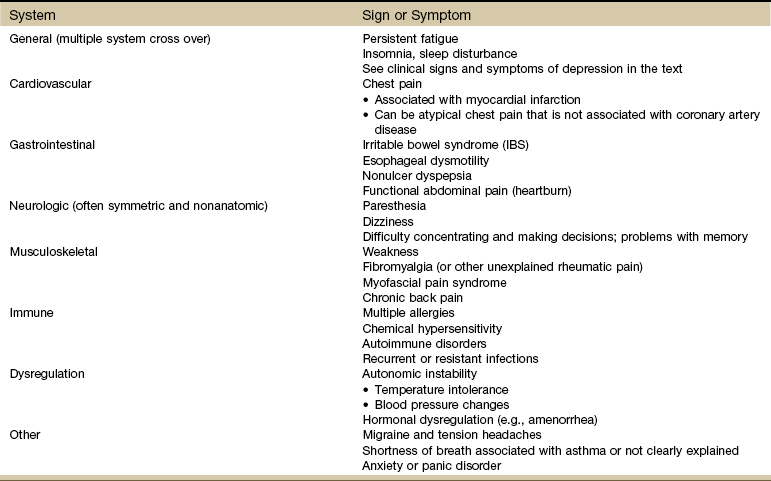

Tests such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) second edition (BDI-II),143-145 the Zung Depression Scale,146 or the Geriatric Depression Scale (short form) (Table 3-11) can be administered by a physical therapist to obtain baseline information that may be useful in determining the need for a medical referral. These tests do not require interpretation that is out of the scope of physical therapist practice.

TABLE 3-11

Geriatric Depression Scale (Short Form)

note: The scale is scored as follows: 1 point for each response in capital letters. A score of 0 to 5 is normal; a score above 5 suggests depression and warrants a follow-up interview; a score above 10 almost always indicates depression.

Used with permission from Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA: Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version, Clin Gerontol 5:165–173, 1986.

The short form of the BDI, the most widely used instrument for measuring depression, takes five minutes to complete, and is also used to monitor therapeutic progress. The BDI consists of questions that are noninvasive and straightforward in presentation.

The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report instrument intended to assess the existence and severity of symptoms of depression in adults and adolescents 13 years of age and older as listed in the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-IV-TR.51

When presented with the BDI-II, a client is asked to consider each statement as it relates to the way they have felt for the past 2 weeks, to more accurately correspond to the DSM-IV criteria. The authors warn against the use of this instrument as a sole diagnostic measure because depressive symptoms may be part of other primary diagnostic disorders (see Box 3-10).

In the acute care setting, the therapist may see results of the BDI-II for Medical Patients in the medical record. This seven-item self-report measure of depression in adolescents and adults reflects the cognitive and affective symptoms of depression, while excluding somatic and performance symptoms that might be attributable to other conditions. It is a quick and effective way to assess depression in populations with biological, medical, alcohol, and/or substance abuse problems.

The Beck Scales for anxiety, depression, or suicide can help identify clients from ages 13 to 80 with depressive, anxious, or suicidal tendencies even in populations with overlapping physical and/or medical problems.

The Beck Scales have been developed and validated to assist health care professionals in making focused and reliable client evaluations. Test results can be the first step in recognizing and appropriately treating an affective disorder. These are copyrighted materials and can be obtained directly from The Psychological Corporation now under the new name of Harcourt Assessment.147

If the resultant scores for any of these assessment tools suggest clinical depression, psychologic referral is not always necessary. Intervention outcome can be monitored closely, and if progress is not made, the therapist may want to review this outcome with the client and discuss the need to communicate this information to the physician. Depression can be treated effectively with a combination of therapies, including exercise, proper nutrition, antidepressants, and psychotherapy.

Symptoms of Depression: About one-third of the clinically depressed clients treated do not feel sad or blue. Instead, they report somatic symptoms such as fatigue, joint pain, headaches, or chronic back pain (or any chronic, recurrent pain present in multiple places).

Eighty per cent to 90% of the most common GI disorders (e.g., esophageal motility disorder, nonulcer dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome) are associated with depressive or anxiety disorders.140-148

Some scientists think the problem is overresponse of the enteric system to stimuli. The gut senses stimuli too early, receives too much of a signal, and responds with too much of a reaction. Serotonin levels are low and substance P levels are too high when, in fact, these two neurotransmitters are supposed to work together to modulate the GI response.149,150

Other researchers propose that one of the mechanisms underlying chronic disorders associated with depression such as irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia is an increased activation of brain regions concerned with the processing and modulation of visceral and somatic afferent information, particularly in the subregions of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC).151

Another red flag for depression is any condition associated with smooth muscle spasm such as asthma, irritable or overactive bladder, Raynaud’s disease, and hypertension. Neurologic symptoms with no apparent cause such as paresthesias, dizziness, and weakness may actually be symptoms of depression. This is particularly true if the neurologic symptoms are symmetric or not anatomic.134

Drugs, Depression, Dementia, or Delirium?: The older adult often presents with such a mixed clinical presentation, it is difficult to know what is a primary musculoskeletal problem and what could be caused by drugs or depression (Case Example 3-7). Family members confuse signs and symptoms of depression with dementia and often ask the therapist for a differentiation.

Any altered mental status can be the first sign of delirium or dementia. Delirium is a neuropsychiatric syndrome often seen in the acute care setting and characterized by inattention, disorientation, psychomotor agitation, and an altered level of consciousness.152

Depression and dementia share some common traits, but there are differences. A medical diagnosis is needed to make the differentiation. The therapist may be able to provide observational clues by noting any of the following153:

• Mental function: declines more rapidly with depression

• Disorientation: present only in dementia

• Difficulty concentrating: depression

• Difficulty with short-term memory: dementia

• Writing, speaking, and motor impairments: dementia

• Memory loss: people with depression notice and comment, people with dementia are indifferent to the changes

Risk factors for delirium include older age, prior cognitive impairment, presence of infection, severe illness or multiple comorbidities, dehydration, psychotropic medications, alcohol abuse, vision or hearing impairment, fractures, low albumin, recent metastasis, and recent radiation therapy (see further discussion in Chapter 4; see also Box 4-2).154 Screening for delirium is discussed further in Chapter 4.

Panic Disorder

Persons with panic disorder have episodes of sudden, unprovoked feelings of terror or impending doom with associated physical symptoms such as racing or pounding heartbeat, breathlessness, nausea, sweating, and dizziness. During an attack, people may fear that they are gravely ill, going to die, or going crazy.

The fear of another attack can itself become debilitating so that these individuals avoid situations and places that they believe will trigger the episodes, thus affecting their work, their relationships, and their ability to take care of everyday tasks.

Initial panic attacks may occur when people are under considerable stress, for example, an overload of work or from loss of a family member or close friend. The attacks may follow surgery, a serious accident, illness, or childbirth. Excessive consumption of caffeine or use of cocaine, other stimulant drugs, or medicines containing caffeine or stimulants used in treating asthma can also trigger panic attacks.155

The symptoms of a panic attack can mimic those of other medical conditions, such as respiratory or heart problems. Anxiety or panic is a leading cause of chest pain mimicking a heart attack. Residual sore muscles are a consistent finding after the panic attack and can also occur in individuals with social phobias. People suffering from these attacks may be afraid or embarrassed to report their symptoms to the physician.

The alert therapist may recognize the need for a medical referral. A combination of antidepressants known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) combined with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been proven effective in controlling symptoms.

Panic disorder is characterized by periods of sudden, unprovoked, intense anxiety with associated physical symptoms lasting a few minutes up to a few hours. Dizziness, paresthesias, headaches, and palpitations are common.

Pain perception involves a sensory component (pain sensation) and an emotional reaction referred to as the sensory-discriminative and motivational-affective dimensions, respectively.156

Psychoneuroimmunology

When it comes to pain assessment, sources of pain, mechanisms of pain, and links between the mind and body, it is impossible to leave out a discussion of a new area of research and study called psychoneuroimmunology (PNI). PNI is the study of the interactions among behavior, neural, endocrine, enteric (digestive), and immune system function.

PNI explains the influence of the nervous system on the immune and inflammatory responses and how the immune system communicates with the neuroendocrine systems. The immune system can activate sensory nerves and the CNS by releasing proinflammatory cytokines, creating an exaggerated pain response.157

Further, there is a unique integration of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the neuroendocrine-enteric axis. This is accomplished on a biologic basis, a discovery first made in the late 1990s. Physiologically adaptive processes occur as a result of these biochemically based mind-body connections and likely impact the perception of pain and memory of pain.

Researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) made a groundbreaking discovery when the biologic basis for emotions (neuropeptides and their receptors) was identified. This new understanding of the interconnections between the mind and body goes far beyond our former understanding of the psychosomatic response in illness, disease, or injury.158

Neuropeptides are chemical messengers that move through the bloodstream to every cell in the body. These information molecules take messages throughout the body to every cell and organ system. For example, the digestive (enteric) system and the neurologic system communicate with the immune system via these neuropeptides. These three systems can exchange information and influence one another’s actions.

More than 30 different classes of neuropeptides have been identified. Every one of these messengers is found in the enteric nervous system of the gut. The constant presence of these neurotransmitters and neuromodulators in the bowel suggests that emotional expression of active coping generates a balance in the neuropeptide-receptor network and physiologic healing beginning in the GI system.

The identification of biologic carriers of emotions has also led to an understanding of a concept well known to physical therapists but previously unnamed: cellular memories.159-162 Many health care professionals have seen the emotional and psychological response of a hands-on approach. Concepts labeled as craniosacral, unwinding, myofascial release, and soft tissue mobilization are based (in part) with this in mind.

These new discoveries help substantiate the idea that cells containing memories are shuttled through the body and brain via chemical messengers. The biologic basis of emotions and memories helps explain how soft tissues respond to emotions; indeed, the soft tissue structures may even contain emotions by way of neuropeptides.

Perhaps this can explain why two people can experience a car accident and whiplash (flexion-extension) or other injury. One recovers without any problems, while the other develops chronic pain that is resistant to any intervention. The focus of research on behavioral approaches combined with our hands-on intervention may bring a better understanding of what works and why.

Other researchers investigating neuropathic pain see a link between memory and pain. Studies looking at the physical similarities between the way a memory is formed and the way pain becomes persistent and chronic support such a link.163

Researchers suggest when somatic pain persists beyond the expected time of healing the pain no longer originates in the tissue that was damaged. Pain begins in the CNS instead. The experience changes the nervous system. The memory of pain recurs again and again in the CNS.163

The nervous system transmits pain signals efficiently, and small pain signals may be amplified until the sensation of pain is out of proportion to what is expected for the injury. Pain amplification occurs in the spinal cord. Spinal cord cells called glia become activated, releasing a variety of chemical substances that cause pain messages to become amplified.164

Other researchers have reported the discovery of a protein that allows nerve cells to communicate and thereby enhance perceptions of chronic pain. The results reinforce the notion that the basic process that leads to memory formation may be the same as the process that causes chronic pain.165

Along these same lines, other researchers have shown a communication network between the immune system and the brain. Pain phenomena are actually modulated by immune function. Proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF, IL-1, IL-6) released by activated immune cells signal the brain by both blood-borne and neural routes, leading to alterations in neural activity.166

The cytokines in the brain interfere with cognitive function and memory; the cytokines within the spinal cord exaggerate fatigue and pain. By signaling the CNS, these proinflammatory cytokines create exaggerated pain, as well as an entire constellation of physiologic, hormonal, and behavioral changes referred to as the sickness response.167,168

In essence immune processes work well when directed against pathogens or cancer cells. When directed against peripheral nerves, dorsal nerve ganglia, or the dorsal roots in the spinal cord, the immune system attacks the nerves, resulting in extreme pain.

Such exaggerated pain states occur with infection, inflammation, or trauma of the skin, peripheral nerves, and CNS. The neuroimmune link may help explain the exaggerated pain state associated with conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia.

With this new understanding that all peripheral nerves and neurons are affected by immune and glial activation, intervention to modify pain will likely change in the near future.157,169

Screening for Systemic Versus Psychogenic Symptoms

Screening for emotional or psychologic overlay has a place in our examination and evaluation process. Recognizing that this emotion-induced somatic pain response has a scientific basis may help us find better ways to alter or eliminate it.

The key in screening for systemic versus psychogenic basis of symptoms is to identify the client with a significant emotional or psychologic component influencing the pain experience. Whether to refer the client for further psychologic evaluation and treatment or just modify the physical therapy plan of care is left up to the therapist’s clinical judgment.

In all cases of pain, watch for the client who reports any of the following red flag symptoms:

• Symptoms are out of proportion to the injury.

• Symptoms persist beyond the expected time for physiologic healing.

These symptoms reflect both the possibility of an emotional or psychologic overlay, as well as the possibility of a more serious underlying systemic disorder (including cancer). In this next section, we will look at ways to screen for emotional content, keeping in mind what has already been said about anxiety, depression, and panic disorder.

Screening Tools for Emotional Overlay

Screening tools for emotional overlay can be used quickly and easily to help screen for emotional overlay in painful symptoms (Box 3-12). The client may or may not be aware that he or she is in fact exaggerating pain responses, catastrophizing the pain experience, or otherwise experiencing pain associated with emotional or psychologic overlay.

This discussion does not endorse physical therapists’ practicing as psychologists, which is outside the scope of our expertise and experience. It merely recognizes that in treating the whole client not only the physical but also the psychologic, emotional, and spiritual needs of that person will be represented in his or her magnitude of symptoms, length of recovery time, response to pain, and responsibility for recovery.

Pain Catastrophizing Scale

Pain catastrophizing refers to a negative view of the pain experience or expecting the worst to happen. Catastrophizing boosts anxiety and worry. These emotions stimulate neural systems that produce increased sensitivity to pain so that pain is exaggerated or blown out of proportion. It can occur in a person who already has pain or in individuals who have not even had any pain yet—that person is just anticipating it might happen.

Pain catastrophizing is increasingly being recognized as an important factor in the experience of pain. There is evidence to suggest that pain catastrophizing is related to various levels of pain, physical disability, and psychological disability in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain.170,171 Without intervention, these pain-related fears can lead to chronic pain and disability over time.172

Identifying pain catastrophizing can help in the screening process to make appropriate referral for behavioral therapy and coordinate rehabilitative efforts. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)173 can be used to assist in the screening process. It is significantly predictive of perceived disability and more strongly predictive of function than pain intensity.172 The PCS is a 13-item self-report scale with items in three different categories (rumination, magnification, and helplessness) that are rated on a scale from 0 to 4. It has shown strong evidence of validity but remains under investigation.171,174

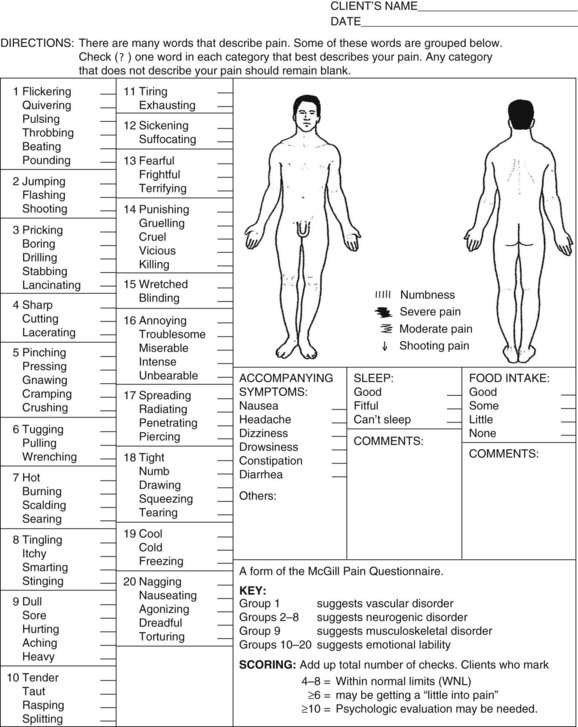

McGill Pain Questionnaire

The McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) from McGill University in Canada is a well-known and commonly used tool in assessing chronic pain. The MPQ is designed to measure the subjective pain experience in a quantitative form. It is considered a good baseline for assessing pain and has both high reliability and validity in younger adults. To our knowledge, it has not been tested specifically with older adults.

The MPQ consists primarily of two major classes of word descriptors, sensory and affective (emotional), and can be used to specify the subjective pain experience. It also contains an intensity scale and other items to determine the properties of pain experience.

There is a shorter version, which some clinicians find more practical for routine use.40,175 It can be used for both assessment and ongoing monitoring for any condition. However, for screening purposes outlined here, the format of the original MPQ may work best (Fig. 3-11).

Fig. 3-11 McGill-Melzack Pain Questionnaire. The key and scoring information can be used to screen for emotional overlay or to identify a specific somatic or visceral source of pain. Instructions are provided in the text. (From Melzack R: The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods, Pain 1:277–299, 1975.)

The original form of the MPQ with all its affective word descriptors to help clients describe their pain gives results that help the therapist identify the source of the pain: vascular (visceral), neurogenic (somatic), musculoskeletal (somatic), or emotional (psychosomatic) (see Table 3-1).

When administering this portion of the questionnaire, the therapist reads the list of words in each box. The client is to choose the one word that best describes his or her pain. If no word in the box matches, the box is left blank. The words in each box are listed in order of ascending (rank order) intensity.

For example, in the first box, the words begin with “flickering” and “quivering” and gradually progress to “beating” and “pounding.” Beating and pounding are considered much more intense than flickering and quivering. Word descriptors included in Group 1 reflect characteristics of pain of a vascular disorder. Knowing this information can be very helpful as the therapist continues the examination and evaluation of the client.

Groups 2 through 8 are words used to describe pain of a neurogenic origin. Group 9 reflects the musculoskeletal system and groups 10 through 20 are all the words a client might use to describe pain in emotional terms (e.g., torturing, killing, vicious, agonizing).

After completing the questionnaire with the client, add up the total number of checks. According to the key, choosing up to eight words to describe the pain is within normal limits. Selecting more than 10 is a red flag for emotional or psychologic overlay, especially when the word selections come from groups 10 through 20.

Illness Behavior Syndrome and Symptom Magnification

Pain in the absence of an identified source of disease or pathologic condition may elicit a behavioral response from the client that is now labeled illness behavior syndrome. Illness behavior is what people say and do to show they are ill or perceive themselves as sick or in pain. It does not mean there is nothing wrong with the person. Illness behavior expresses and communicates the severity of pain and physical impairment.90

This syndrome has been identified most often in people with chronic pain. Its expression depends on what and how the client thinks about his or her symptoms/illness. Components of this syndrome include:

• Dramatization of complaints, leading to overtreatment and overmedication

• Progressive dysfunction, leading to decreased physical activity and often compounding preexisting musculoskeletal or circulatory dysfunction

• Progressive dependency on others, including health care professionals, leading to overuse of the health care system

• Income disability, in which the person’s illness behavior is perpetuated by financial gain88

Symptom magnification syndrome (SMS) is another term used to describe the phenomenon of illness behavior; conscious symptom magnification is referred to as malingering, whereas unconscious symptom magnification is labeled illness behavior. Conscious malingering may be described as exaggeration or faking symptoms for external gain. Some experts differentiate symptom amplification from malingering or factitious disorder (i.e., fakery or self-induced symptoms that enable the sick role).176

The term symptom magnification was first coined by Leonard N. Matheson, PhD,* in 1977 to describe clients whose symptoms have reinforced their behavior, that is, the symptoms have become the predominant force in the client’s function rather than the physiologic phenomenon of the injury determining the outcome.

By definition, SMS is a self-destructive, socially reinforced behavioral response pattern consisting of reports or displays of symptoms that function to control the life of the sufferer.177-179 The amplified symptoms rather than the physiologic phenomenon of the injury determine the outcome/function.

The affected person acts as if the future cannot be controlled because of the presence of symptoms. All present limitations are blamed on the symptoms: “My (back) pain won’t let me … .” The client may exaggerate limitations beyond those that seem reasonable in relation to the injury, apply minimal effort on maximal performance tasks, and overreact to physical loading during objective examination.

It is important for physical therapists to recognize that we often contribute to SMS by focusing on the relief of symptoms, especially pain, as the goal of therapy. Reducing pain is an acceptable goal for some types of clients, but for those who experience pain after the injuries have healed, the focus should be restoration, or at least improvement, of function.

In these situations, instead of asking whether the client’s symptoms are “better, the same, or worse,” it may be more appropriate to inquire about functional outcomes, for example, what can the client accomplish at home that she or he was unable to attempt at the beginning of treatment, last week, or even yesterday.

Conscious or unconscious? Can a physical therapist determine when a client is consciously or unconsciously symptom magnifying? Is it within the scope of the physical therapist’s practice to use the label “malingerer” without a psychologist or psychiatrist’s diagnosis of such first?

Physical exam techniques available include McBride’s, Mankopf’s, Waddell’s, Hoover’s, Abductor, Arm Drop, and Midline Split. The evidence supporting strength of recommendation (SOR) for these tests to detect malingering is ranked as B (systematic review of low-quality studies) or C (expert opinion, small case studies). For a review of these tests and a summary of the evidence for each one, see Greer et al, 2005.180 The American Psychiatric Association and the American Medical Association agree confirmation of malingering is extremely difficult and depends on direct observation. It is safest to assume a person is not malingering unless direct evidence is available.51,181

Keep in mind the goal is to screen for a psychologic or emotional component to the client’s clinical presentation. The key to achieving this goal is to use objective test measures whenever possible. In this way, the therapist obtains the guidance needed for referral versus modification of the physical therapy intervention.

Compiling a list of nonorganic or behavioral signs and identifying how the client is reacting to pain may be all that is needed. Signs of illness behavior may point the therapist in the direction of more careful “management” of the psychosocial and behavioral aspects of the client’s illness.116

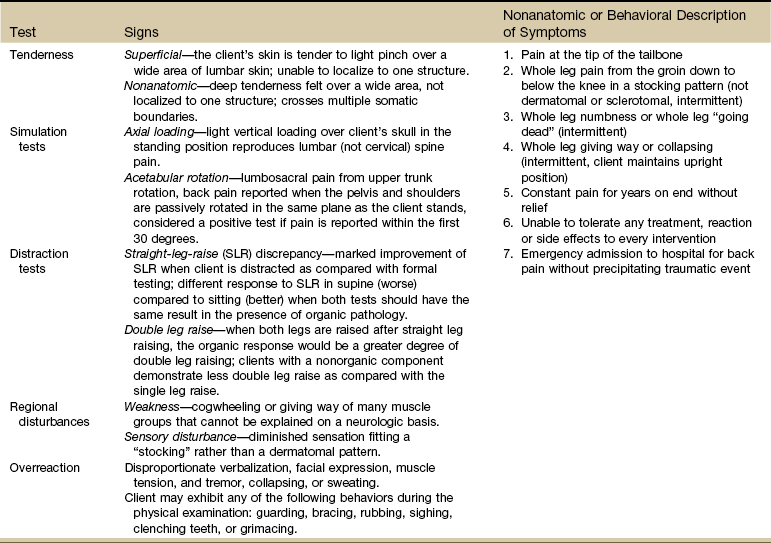

Waddell’s Nonorganic Signs

Waddell et al182 identified five nonorganic signs and seven nonanatomic or behavioral descriptions of symptoms (Table 3-12) to help differentiate between physical and behavioral causes of back pain. Each of the nonorganic signs is determined by using one or two of the tests listed. These tests are used to assess a client’s pain behavior and detect abnormal illness behavior. The literature supports that these signs may be present in 10% of clients with acute low back pain, but are found most often in people with chronic low back pain.

TABLE 3-12

Waddell’s Nonorganic Signs and Behavioral Symptoms

Adapted from Karas R, McIntosh G, Hall H, et al: The relationship between nonorganic signs and centralization of symptoms in the prediction of return to work for patients with low back pain, Phys Ther 77(4):354–360, 1997.

A score of three or more positive signs places the client in the category of nonmovement dysfunction. This person is said to have a clinical pattern of nonmechanical, pain-focused behavior. This type of score is predictive of poor outcome and associated with delayed return-to-work or not working.

One or two positive signs is a low Waddell’s score and does not classify the client with a nonmovement dysfunction. The value of these nonorganic signs as predictors for return-to-work for clients with low back pain has been investigated.183 Less than two is a good prognosticator of return-to-work. The results of how this study might affect practice are available.184

A positive finding for nonorganic signs does not suggest an absence of pain but rather a behavioral response to pain (see discussion of symptom magnification syndrome). It does not confirm malingering or illness behavior. Neither do these signs imply the nonexistence of physical pathology.

Waddell and associates117,182 have given us a tool that can help us identify early in the rehabilitation process those who need more than just mechanical or physical treatment intervention. Other evaluation tools are available (e.g., Oswestry Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire). A psychologic evaluation and possibly behavioral therapy or psychologic counseling may be needed as an adjunct to physical therapy.185

Conversion Symptoms

Whereas SMS is a behavioral, learned, inappropriate behavior, conversion is a psychodynamic phenomenon and quite rare in the chronically disabled population.

Conversion is a physical expression of an unconscious psychologic conflict such as an event (e.g., loss of a loved one) or a problem in the person’s work or personal life. The conversion may provide a solution to the conflict or a way to express “forbidden” feelings. It may be a means of enacting the sick role to avoid responsibilities, or it may be a reflection of behaviors learned in childhood.16

Diagnosis of a conversion syndrome is difficult and often requires the diagnostic and evaluative input of the physical therapist. Presentation always includes a motor and/or sensory component that cannot be explained by a known medical or neuromusculoskeletal condition.

The clinical presentation is often mistaken for an organic disorder such as multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, myasthenia gravis, or idiopathic dystonias. At presentation, when a client has an unusual limp or bizarre gait pattern that cannot be explained by functional anatomy, family members may be interviewed to assess changes in the client’s gait and whether this alteration in movement pattern is present consistently.

The physical therapist can look for a change in the wear pattern of the client’s shoes to decide if this alteration in gait has been long-standing. During manual muscle testing, true weakness results in smooth “giving way” of a muscle group; in hysterical weakness the muscle “breaks” in a series of jerks.

Often the results of muscle testing are not consistent with functional abilities observed. For example, the person cannot raise the arm overhead during testing but has no difficulty dressing, or the lower extremity appears flaccid during recumbency but the person can walk on the heels and toes when standing.

The physical therapist should carefully evaluate and document all sensory and motor changes. Conversion symptoms are less likely to follow any dermatome, myotome, or sclerotome patterns.

Screening Questions for Psychogenic Source of Symptoms

Besides observing for signs and symptoms of psychophysiologic disorders, the therapist can ask a few screening questions (Box 3-13). The client may be aware of the symptoms but does not know that these problems can be caused by depression, anxiety, or panic disorder.

Medical treatment for physiopsychologic disorders can and should be augmented with exercise. Physical activity and exercise has a known benefit in the management of mild-to-moderate psychologic disorders, especially depression and anxiety. Aerobic exercise or strength training have both been shown effective in moderating the symptoms of these conditions.186-189

Patience is a vital tool for therapists when working with clients who are having difficulty adjusting to the stress of illness and disability or the client who has a psychologic disorder. The therapist must develop personal coping mechanisms when working with clients who have chronic illnesses or psychologic disturbances.

Recognizing clients whose symptoms are the direct result of organic dysfunction helps us in coping with clients who are hostile, ungrateful, noncompliant, negative, or adversarial. Whenever possible, involve a psychiatrist, psychologist, or counselor as part of the management team. This approach will benefit the client as well as the health care staff.

Physician Referral

Guidelines for Immediate Physician Referral

• Immediate medical attention is required for anyone with risk factors for and clinical signs and symptoms of rhabdomyolysis (see Table 3-5).

• Clients reporting a disproportionate relief of bone pain with a simple aspirin may have bone cancer. This red flag requires immediate medical referral in the presence of a personal history of cancer of any kind.

• Joint pain with no known cause and a recent history of infection of any kind. Ask about recent (last 6 weeks) skin lesions or rashes of any kind anywhere on the body, urinary tract infection, or respiratory infection. Take the client’s temperature and ask about recent episodes of fever, sweats, or other constitutional symptoms. Palpate for residual lymphadenopathy. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to limit joint destruction and preserve function.78

Guidelines for Physician Referral Required

• Proximal muscle weakness accompanied by change in one or more deep tendon reflexes in the presence of a previous history of cancer.

• The physician should be notified of anyone with joint pain of unknown cause who presents with recent or current skin rash or recent history of infection (hepatitis, mononucleosis, urinary tract infection, upper respiratory infection, STI, streptococcus).

• A team approach to fibromyalgia requires medical evaluation and management as part of the intervention strategy. Therapists should refer clients suspected with fibromyalgia for further medical follow up.

• Diffuse pain that characterizes some diseases of the nervous system and viscera may be difficult to distinguish from the equally diffuse pain so often caused by lesions of the moving parts. The distinction between visceral pain and pain caused by lesions of the vertebral column may be difficult to make and may require a medical diagnosis.

• The therapist may screen for signs and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and panic disorder. These conditions are often present with somatic symptoms that may resolve with effective intervention. The therapist can describe the symptoms and relay that information to the appropriate agency or individual when making a referral. Diagnosis is made by a medical doctor or trained mental health professional.

• Clients with new onset of back, neck, TMJ, shoulder, or arm pain brought on by a new exercise program or by exertion with the arms raised overhead should be screened for signs and symptoms of cardiovascular impairment. This is especially important if the symptoms are described as “throbbing” and start after a brief time of exercise (3 to 5 up to 10 minutes) and diminish or go away quickly with rest. Look for significant risk factors for cardiovascular involvement. Check vital signs. Refer for medical evaluation if indicated.

• Persistent pain on weight bearing or bone pain at night, especially in the older adult with risk factors such as osteoporosis, postural hypotension leading to falls, or previous history of cancer.

Clues to Screening for Viscerogenic Sources of Pain

We know systemic illness and pathologic conditions affecting the viscera can mimic NMS dysfunction. The therapist who knows pain patterns and types of viscerogenic pain can sort through the client’s description of pain and recognize when something does not fit the expected pattern for NMS problems.

We must keep in mind that pain from a disease process or viscerogenic source is often a late symptom rather than a reliable danger signal. For this reason the therapist must remain alert to other signs and symptoms that may be present but unaccounted for.

In this chapter, pain types possible with viscerogenic conditions have been presented along with three mechanisms by which viscera refer pain to the body (soma). Characteristics of systemic pain compared to musculoskeletal pain are presented, including a closer look at joint pain.

Pain with the following features raises a red flag to alert the therapist of the need to take a closer look:

• Pain that persists beyond the expected time for physiologic healing.

• Pain that is out of proportion to the injury.

• Pain that is unrelieved by rest or change in position.

• Pain pattern does not fit the expected clinical presentation for a neuromuscular or musculoskeletal impairment.

• Pain that cannot be altered, aggravated, provoked, reduced, eliminated, or alleviated.

• There are some positions of comfort for various organs (e.g., leaning forward for the gallbladder or side bending for the kidney), but with progression of disease the client will obtain less and less relief of symptoms over time.

• Pain, symptoms, or dysfunction are not improved or altered by physical therapy intervention.

• Pain that is poorly localized.

• Pain accompanied by signs and symptoms associated with a specific viscera (e.g., GI, GU, gynecologic [GYN], cardiac, pulmonary, endocrine).

• Pain that is constant and intense no matter what position is tried and despite rest, eating, or abstaining from food; a previous history of cancer in this client is an even greater red flag necessitating further evaluation.

• Pain (especially intense bone pain) that is disproportionately relieved by aspirin.

• Listen to the client’s choice of words to describe pain. Systemic or viscerogenic pain can be described as deep, sharp, boring, knifelike, stabbing, throbbing, colicky, or intermittent (comes and goes in waves).

• Pain accompanied by full and normal ROM.

• Pain that is made worse 3 to 5 minutes after initiating an activity and relieved by rest (possible symptom of vascular impairment) versus pain that goes away with activity (symptom of musculoskeletal involvement); listen for the word descriptor “throbbing” to describe pain of a vascular nature.

• Pain is a relatively new phenomenon and not a pattern that has been present over several years’ time.

• Constitutional symptoms in the presence of pain.

• Pain that is not consistent with emotional or psychologic overlay.

• When in doubt, conduct a screening exam for emotional overlay. Observe the client for signs and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and/or panic disorder. In the absence of systemic illness or disease and/or in the presence of suspicious psychologic symptoms, psychologic evaluation may be needed.

• Pain in the absence of any positive Waddell’s signs (i.e., Waddell’s test is negative or insignificant).

• Manual therapy to correct an upslip is not successful, and the problem has returned by the end of the session or by the next day; consider a somato-visceral problem or visceral ligamentous problem.

• If painful, tender or sore points (e.g., TrPs, Jones’ points, acupuncture/acupressure points/Shiatsu) are eliminated with intervention then return quickly (by the end of the treatment session), suspect visceral pathology. If a tender point comes back later (several days or weeks), the clinician may not be holding it long enough.4

• Back, neck, TMJ, shoulder, or arm pain brought on by exertion with the arms raised overhead may be suggestive of a cardiac problem. This is especially true in the postmenopausal woman or man over age 50 with a significant family history of heart disease and/or in the presence of hypertension.

• Back, shoulder, pelvic, or sacral pain that is made better or worse by eating, passing gas, or having a bowel movement.

• Night pain (especially bone pain) that awakens the client from a sound sleep several hours after falling asleep; this is even more serious if the client is unable to get back to sleep after changing position, taking pain relievers, or eating or drinking something.

• Joint pain preceded or accompanied by skin lesions (e.g., rash or nodules), following antibiotics or statins, or recent infection of any kind (e.g., GI, pulmonary, GU); check for signs and symptoms associated with any of these systems based on recent client history.

• Clients can have more than one problem or pathology present at one time; it is possible for a client to have both a visceral AND a mechanical problem.4

• Remember Osler’s Rule of Age*: Under age 60, most clients’ symptoms are related to one problem, but over 60, it is rarely just one problem.4

• A careful general history and physical examination is still the most important screening tool; never assume this was done by the referring physician or other staff from the referring agency.4

• Visceral problems are unlikely to cause muscle weakness, reflex changes, or objective sensory deficits (exceptions include endocrine disease and paraneoplastic syndromes associated with cancer). If pain is referred from the viscera to the soma, challenging the somatic structure by stretching, contracting, or palpating will not reproduce the symptoms. For example, if a muscle is not sore when squeezed or contracted, the muscle is not the source of the pain.4

1. What is the best follow-up question for someone who tells you that the pain is constant?

a. Can you use one finger to point to the pain location?

b. Do you have that pain right now?

c. Does the pain wake you up at night after you have fallen asleep?

2. A 52-year-old woman with shoulder pain tells you that she has pain at night that awakens her. After asking a series of follow-up questions, you are able to determine that she had trouble falling asleep because her pain increases when she goes to bed. Once she falls asleep, she wakes up as soon as she rolls onto that side. What is the most likely explanation for this pain behavior?

a. Minimal distractions heighten a person’s awareness of musculoskeletal discomfort.

b. This is a systemic pattern that is associated with a neoplasm.

d. This represents a chronic clinical presentation of a musculoskeletal problem.

3. Referred pain patterns associated with impairment of the spleen can produce musculoskeletal symptoms in:

4. Associated signs and symptoms are a major red flag for pain of a systemic or visceral origin compared to musculoskeletal pain.

5. Words used to describe neurogenic pain often include:

6. Pain (especially intense bone pain) that is disproportionately relieved by aspirin can be a symptom of:

7. Joint pain can be a reactive, delayed, or allergic response to:

8. Bone pain associated with neoplasm is characterized by:

9. Pain of a viscerogenic nature is not relieved by a change in position.

10. Referred pain from the viscera can occur alone but is usually preceded by visceral pain when an organ is involved.

11. A 48-year old man presented with low back pain of unknown cause. He works as a carpenter and says he is very active, has work-related mishaps (accidents and falls), and engages in repetitive motions of all kinds using his arms, back, and legs. The pain is intense when he has it, but it seems to come and go. He is not sure if eating makes the pain better or worse. He has lost his appetite because of the pain. After conducting an examination including a screening exam, the clinical presentation does not match the expected pattern for a musculoskeletal or neuromuscular problem. You refer him to a physician for medical testing. You find out later he had pancreatitis. What is the most likely explanation for this pain pattern?

a. Toxic waste products from the pancreas are released into the intestines causing irritation of the retroperitoneal space.

b. Rupture of the pancreas causes internal bleeding and referred pain called Kehr’s sign.

c. The pancreas and low back structures are formed from the same embryologic tissue in the mesoderm.

d. Obstruction, irritation, or inflammation of the body of the pancreas distends the pancreas, thus applying pressure on the central respiratory diaphragm.

References

1. Flaherty, JH. Who’s taking your fifth vital sign? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M397–M399.

2. Sluka, KA. Mechanisms and management of pain for the physical therapist. Seattle: IASP Press; 2009.

3. Brumovsky, PR, Gebhart, GF. Visceral organ cross-sensitization—an integrated perspective. Auton Neurosci. 2010;153(1-2):106–115.

4. Rex, L. Evaluation and treatment of somatovisceral dysfunction of the gastrointestinal system. Edmonds, WA: URSA Foundation; 2004.

5. Christianson, JA. Development, plasticity, and modulation of visceral afferents. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(1):171–178.

6. Chaban, W. Peripheral sensitization of sensory neurons. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(1 Suppl 1):S1–S6.

7. Squire, LR. Fundamental neuroscience, ed 3. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2008.

8. Saladin, KS. Personal communication, Distinguished Professor of Biology. Milledgeville, Georgia: Georgia College and State University; 2004.

9. Woolf, CJ, Decosterd, I. Implications of recent advances in the understanding of pain pathophysiology for the assessment of pain in patients. Pain Suppl. 1999;6:S141–S147.

10. Strigio, I, Differentiation of visceral and cutaneous pain in the human brain. J Neurophysiol 2003;89:3294–3303. Available at http://jn.physiology.org/cgi/content/abstract/89/6/3294.

11. Aziz, Q. Functional neuroimaging of visceral sensation. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;17(6):604–612.

12. Giamberardino, M. Viscero-visceral hyperalgesia: characterization in different clinical models. Pain. 2010;151(2):307–322.

13. Leavitt, RL. Developing cultural competence in a multicultural world. Part II. PT Magazine. 2003;11(1):56–70.

14. O’Rourke, D. The measurement of pain in infants, children, and adolescents: from policy to practice. Phys Ther. 2004;84(6):560–570.

15. Wentz, JD. Assessing pain at the end of life. Nursing2003. 2003;33(8):22.

16. Melzack, R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277.

17. American Geriatrics Society (AGS). Chronic pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1331–1346.

18. American Geriatrics Society Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons (revised guideline). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(Suppl 6):205–224.

19. Argoff, CE, Ferrell, B. Pharmacologic therapy for persistent pain in older adults: the updated American Geriatrics Society Guidelines and their clinical implications. Pain Medicine News. 2010;8(5):1–8.

20. Herr, KA, Spratt, K, Mobily, PR, et al. Pain intensity assessment in older adults: use of experimental pain to compare psychometric properties and usability of selected pain scales with younger adults. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(4):207–219.

21. Lane, P. Assessing pain in patients with advanced dementia. Nursing2004. 2004;34(8):17.

22. D’Arcy, Y. Assessing pain in patients who can’t communicate. Nursing2004. 2004;34(10):27.

23. Hurley, AC. Assessment of discomfort in advanced Alzheimer patients. Res Nurs Health. 1992;15(5):369–377.

24. Warden, V, Hurley, AC, Volicer, L. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4(1):9–15.

25. Herr, K. Tools for assessment of pain in nonverbal older adults with dementia: a state of the science review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(2):170–192.

26. Feldt, K. The checklist of nonverbal pain indicators (CNPI). Pain Manag Nurs. 2000;1(1):13–21.

27. Pasero, C, Reed, BA, McCaffery, M. Pain in the elderly. In: McCaffery M, ed. Pain: clinical manual. ed 2. St. Louis: Mosby; 1999:674–710.

28. Ferrell, BA. Pain in cognitively impaired nursing home patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10(8):591–598.

29. Wong, D, Baker, C. Pain in children: comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs. 1988;14(1):9017.

30. Hicks, CL, von Baeyer, CL, Spafford, PA, et al. The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93:173–183.

31. Bieri, D. The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for the ratio scale properties. Pain. 1990;41(2):139–150.

32. Wong on Web: FACES Pain Rating Scale, Elsevier Health Science Information, 2004.

33. Baker-Lefkowicz A, Keller V, Wong DL, et al: Young children’s pain rating using the FACES Pain Rating Scale with original vs abbreviated word instructions, unpublished, 1996.

34. von Baeyer, CL, Hicks, CL. Support for a common metric for pediatric pain intensity scales. Pain Res Manage. 2000;4(2):157–160.

35. Ramelet, AS, Abu-Saad, HH, Rees, N, et al. The challenges of pain measurement in critically ill young children: a comprehensive review. Aust Crit Care. 2004;17(1):33–45.

36. Grunau, RE, Craig, KD. Pain expression in neonates: facial action and cry. Pain. 1987;28:395–410.

37. Grunau, RE, Oberlander, T, Holsti, L, et al. Bedside application of the Neonatal Facial Coding System in pain assessment of premature neonates. Pain. 1998;76:277–286.

38. Peters, JW, Koot, HM, Grunau, RE, et al. Neonatal Facial Coding System for assessing postoperative pain in infants: item reduction is valid and feasible. Clin J Pain. 2003;19(6):353–363.

39. Stevens, B. Pain in infants. In: McCaffery M, Pasero C, eds. Pain: clinical manual. ed 2. St. Louis: Mosby; 1999:626–673.

40. Turk DC, Melzack R, eds. Handbook of pain assessment, ed 3, New York: Guilford Press, 2010.

41. Riley, JL, 3rd., Wade, JB, Myers, CD, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in the experience of chronic pain. Pain. 2002;100(3):291–298.

42. Sheffield, D, Biles, PL, Orom, H, et al. Race and sex differences in cutaneous pain perception. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(4):517–523.

43. Unruh, AM, Ritchie, J, Merskey, H. Does gender affect appraisal of pain and pain coping strategies? Clin J Pain. 1999;15(1):31–40.

44. Brown, JL, Sheffield, D, Leary, MR, et al. Social support and experimental pain. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(2):276–283.

45. Huskinson, EC. Measurement of pain. Lancet. 1974;2:1127–1131.

46. Carlsson, AM. Assessment of chronic pain: aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analog scale. Pain. 1983;16:87–101.

47. Dworkin, RH. Development and initial validation of an expanded and revised version of the Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2). Pain. 2009;144(1-2):35–42.

48. Turk DC, Melzack R, eds. Handbook of pain assessment, ed 3, New York: Guilford, 2010.

49. Sahrmann, S. Diagnosis and diagnosticians: the future in physical therapy. Combined Sections Meeting, Dallas, February 13–16 www.apta.org, 1997. [Available at].

50. Courtney, CA. Interpreting joint pain: quantitative sensory testing in musculoskeletal management. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(12):818–825.

51. American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: APA; 2000.

52. Goodman, CC, Fuller, K. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2009.

53. Morrison, J. DSM-IV made easy: the clinician’s guide to diagnosis. New York: Guilford; 2002.

54. Bogduk, N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. Pain. 2009;147(1-3):17–19.

55. International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP pain terminology. Available at http://www.iasp-pain.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Pain_Defi..isplay.cfm&ContentID=1728, 2010. [Accessed December 18].

56. Schaible, HG. Joint pain. Exp Brain Res. 2009;196:153–162.

57. De Gucht, V, Fischler, B. Somatization: a critical review of conceptual and methodological issues. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:1–9.

58. Wells, PE, Frampton, V, Bowsher, D. Pain management in physical therapy, ed 2. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1994.

59. Gebhart, GF. Visceral polymodal receptors. Prog Brain Res. 1996;113:101–112.

60. Simons, D, Travell, J, Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual, Vol 1 and 2, ed 2. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1999.

61. McMahon S, Koltzenburg M, eds. Wall and Melzack’s textbook of pain, ed 5, New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

62. Tasker, RR. Spinal cord injury and central pain. In: Aronoff GM, ed. Evaluation and treatment of chronic pain. ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999:131–146.

63. Prkachin, KM. Pain behavior and the development of pain-related disability: the importance of guarding. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(3):270–277.

64. Pachas, WN. Joint pains and associated disorders. In: Aronoff GM, ed. Evaluation and treatment of chronic pain. ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1999:201–215.

65. Kraus, H. Muscle deficiency. In Rachlin ES, ed.: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia, ed 2, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

66. Cailliet, R. Low back pain syndrome, ed 5. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1995.

67. Emre, M, Mathies, H. Muscle spasms and pain. Park Ridge, Illinois: Parthenon; 1988.

68. Sinnott M: Assessing musculoskeletal changes in the geriatric population, American Physical Therapy Association Combined Sections Meeting, February 3–7, 1993.

69. Potter, JF. The older orthopaedic patient. General considerations. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2004;425:44–49.