Physical Assessment as a Screening Tool

In the medical model, clients are often assessed from head to toe. The doctor, physician assistant, nurse, or nurse practitioner starts with inspection, followed by percussion and palpation, and finally by auscultation.

In a screening assessment, the therapist may not need to perform a complete head-to-toe physical assessment. If the initial observations, client history, screening questions, and screening tests are negative, move on to the next step. A thorough examination may not be necessary.

In most situations, it is advised to assess one system above and below the area of complaint based on evidence supporting a regional-interdependence model of musculoskeletal impairments (i.e., symptoms present may be caused by musculoskeletal impairments proximal or distal to the site of presenting symptoms distinct from the phenomenon of referred pain).1

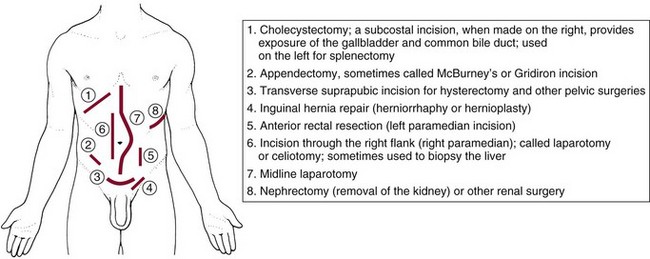

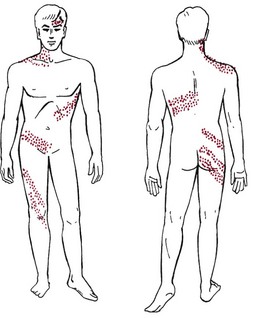

When screening for systemic origins of clinical signs and symptoms, the therapist first scans the area(s) that directly relate to the client’s history and clinical presentation. For example, a shoulder problem can be caused by a problem in the stomach, heart, liver/biliary, lungs, spleen, kidneys, and ovaries (ectopic pregnancy). Only the physical assessment tests related to these areas would be assessed. These often can be narrowed down by the client’s history, gender, age, presence of risk factors, and associated signs and symptoms linked to a specific system.

More specifically, consider the postmenopausal woman with a primary family history of heart disease who presents with shoulder pain that occurs 3 to 4 minutes after starting an activity and is accompanied by unexplained perspiration. This individual should be assessed for cardiac involvement. Or think about the 45-year-old mother of five children who presents with scapular pain that is worse after she eats. A cardiac assessment may not be as important as a scan for signs and symptoms associated with the gallbladder or biliary system.

Documentation of physical findings is important. From a legal standpoint, if you did not document it, you did not assess it. Look for changes from the expected norm, as well as changes for the client’s baseline measurements. Use simple and clear documentation that can be understood and used by others. As much as possible, record both normal and abnormal findings for each client.2 Keep in mind that the client’s cultural and educational background, beliefs, values, and previous experiences can influence his or her response to questions.

Finally, screening and ongoing physical assessment is often a part of an exercise evaluation, especially for the client with one or more serious health concerns. Listening to the heart and lung sounds before initiating an exercise program may bring to light any contraindications to exercise. A compromised cardiopulmonary system may make it impossible and even dangerous for the client to sustain prescribed exercise levels.

The use of quick and easy screening tools such as the Physical Therapist Community Screening Form for Aging Adults can help therapists identify limitations to optimal heath, wellness, and fitness in any of seven areas (e.g., posture, flexibility, strength, balance, cardiovascular fitness) for adults aged 65 and older. With the 2007 House of Delegates position statement recommending that all individuals visit a physical therapist at least once a year to promote optimal health and wellness, evidence-based tests of this type will become increasingly available.3

General Survey

Physical assessment begins the moment you meet the client as you observe body size and type, facial expressions, evaluate self-care, and note anything unusual in appearance or presentation. Keep in mind (as discussed in Chapter 2) that cultural factors may dictate how the client presents himself (e.g., avoiding eye contact when answering questions, hiding or exaggerating signs of pain).

A few pieces of equipment in a small kit within easy reach can make the screening exam faster and easier (Box 4-1). Using the same pattern in screening each time will help the therapist avoid missing important screening clues.

As the therapist makes a general survey of each client, it is also possible to evaluate posture, movement patterns and gait, balance, and coordination. For more involved clients the first impression may be based on level of consciousness, respiratory and vascular function, or nutritional status.

In an acute care or trauma setting the therapist may be using vital signs and the ABCDE (airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure) method of quick assessment. A common strategy for history taking in the trauma unit is the mnemonic AMPLE: Allergies, Medications, Past medical history, Last meal, and Events of injury.

In any setting, knowing the client’s personal health history will also help guide and direct which components of the physical examination to include. We are not just screening for medical disease masquerading as neuromusculoskeletal (NMS) problems. Many physical illnesses, diseases, and medical conditions directly impact the NMS system and must be taken into account. For example inspection of the integument, limb inspection, and screening of the peripheral vascular system is important for someone at risk for lymphedema.

Neurologic function, balance, reflexes, and peripheral circulation become important when screening a client with diabetes mellitus. Peripheral neuropathy is common in this population group, often making walking more difficult and increasing risk of other problems developing.

Therapists in all settings, especially primary care therapists, can use a screening physical assessment to provide education toward primary prevention, as well as intervention and management of current dysfunctions and disabilities.

Mental Status

Level of consciousness, orientation, and ability to communicate are all part of the assessment of a client’s mental status. Orientation refers to the client’s ability to answer correctly questions about time, place, and person. A healthy individual with normal mental status will be alert, speak coherently, and be aware of the date, day, and time of day.

The therapist must be aware of any factor that can affect a client’s current mental status. Shock, head injury, stroke, hospitalization, surgery (use of anesthesia), medications, age, and the use of substances and/or alcohol (see discussion, Chapter 2) can cause impaired consciousness.

Other factors affecting mental status may include malnutrition, exposure to chemicals, and hypothermia or hyperthermia. Depression and anxiety (see discussion, Chapter 3) also can affect a client’s functioning, mood, memory, ability to concentrate, judgment, and thought processes. Educational and socioeconomic background along with communication skills (e.g., English as a second language, aphasia) can affect mental status and function.

In a hospital, transition unit, or extended care facility, mental status is often evaluated and documented by the social worker or nursing service. It is always a good idea to review the client’s chart or electronic record regarding this information before beginning a physical therapy evaluation.

Risk Factors for Delirium

It is not uncommon for older adults to experience a change in mental status or go through a stage of confusion about 24 hours after hospitalization for a serious illness or trauma, including surgery under a general anesthetic. Physicians may refer to this as iatrogenic delirium, anesthesia-induced dementia, or postoperative delirium. It is usually temporary but can last several hours to several weeks.

The cause of deterioration in mental ability is unknown. In some cases, delirium/dementia appears to be triggered by the shock to the body from anesthesia and surgery.4 It may be a passing phase with complete recovery by the client, although this can take weeks to months. The likelihood of delirium associated with hospitalization is much higher with hip fractures and hip and knee joint replacements,5,6 possibly attributed to older age, slower metabolism, and polypharmacy (more than four prescribed drugs at admission).7

The therapist should pay attention to risk factors (Box 4-2) and watch out for any of the signs or symptoms of delirium. Physical exam should include vital signs with oxygen concentration measured, neurologic screening exam, and surveillance for signs of infection. A medical diagnosis is needed to make the distinction between postoperative delirium, baseline dementia, depression, and withdrawal from drugs and alcohol.5

Several scales are used to assess level of consciousness, performance, and disability. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is a bedside rating scale physical therapists can use to assess hospitalized or institutionalized individuals for delirium. This tool has been adapted for use with patients who are ventilated and in an intensive care unit (CAM-ICU).8

There are two parts to the assessment instrument: part one screens for overall cognitive impairment. Part two includes four features that have the greatest ability to distinguish delirium or reversible confusion from other types of cognitive impairment. The tool identifies the presence of delirium but does not assess the severity of the condition.9

As a screening tool, the CAM has been validated for use by physicians and nurses in palliative care and intensive care settings (sensitivity of 94% to 100% and specificity of 90% to 95%). Values for positive predictive accuracy were 91% to 94%, and values for negative predictive accuracy were 100% and 90% for the two populations assessed (general medicine, outpatient geriatric center).9

The Glasgow Outcome Scale10,11 describes patients/clients on a 5-point scale from good recovery (1) to death (5). Vegetative state, severe disability, and moderate disability are included in the continuum. This and other scales and clinical assessment tools are not part of the screening assessment but are available online for use by health care professionals.12

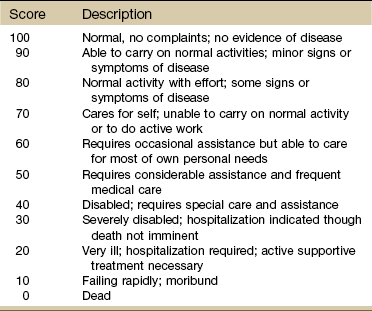

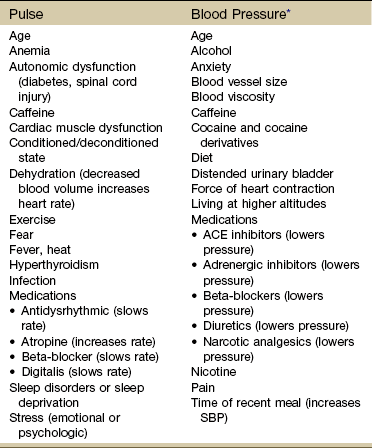

The Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) in Table 4-1 is used widely to quantify functional status in a wide variety of individuals, but especially among those with cancer. It can be used to compare effectiveness of intervention and to assess individual prognosis. The lower the Karnofsky score, the worse the prognosis for survival.

The most practical performance scale for use in any rehabilitation setting for most clients is the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status Scale (Table 4-2). Researchers and health care professionals use these scales and criteria to assess how an individual’s disease is progressing, to assess how the disease affects the daily living abilities of the client, and to determine appropriate treatment and prognosis.

TABLE 4-2

| Grade | Level of Activity |

| 0 | Fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction (Karnofsky 90%-100%) |

| 1 | Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature (e.g., light house work, office work) (Karnofsky 70%-80%) |

| 2 | Ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities. Up and about more than 50% of waking hours (Karnofsky 50%-60%) |

| 3 | Capable of only limited self-care, confined to bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours (Karnofsky 30%-40%) |

| 4 | Completely disabled. Cannot carry on any self-care. Totally confined to bed or chair (Karnofsky 10%-20%) |

| 5 | Dead (Karnofsky 0%) |

The Karnofsky Performance Scale allows individuals to be classified according to functional impairment. The lower the score, the worse the prognosis for survival for most serious illnesses.

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

From Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al: Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Am J Clin Oncol 5:649-655, 1982. Available at www.ecog.org/general/perf_stat.html.

Any observed change in level of consciousness, orientation, judgment, communication or speech pattern, or memory should be documented regardless of which scale is used. The therapist may be the first to notice increased lethargy, slowed motor responses, or disorientation or confusion.

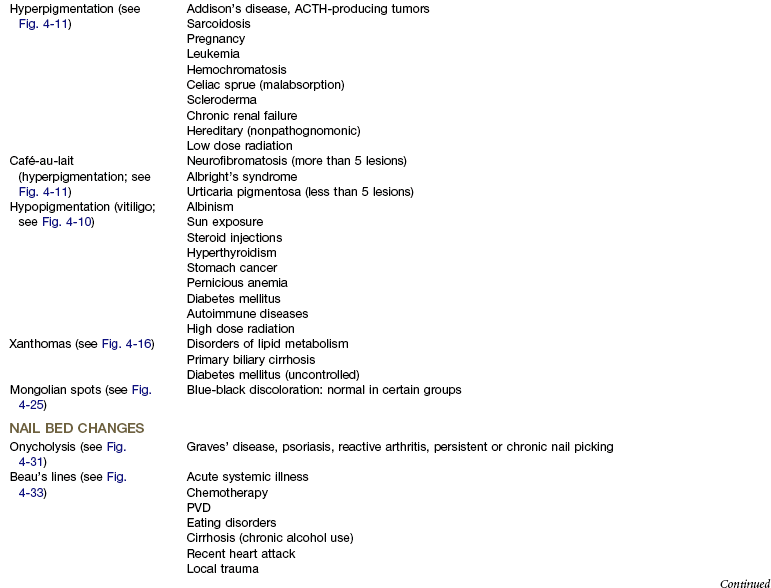

Confusion is not a normal change with aging and must be reported and documented. Confusion is often associated with various systemic conditions (Table 4-3). Increased confusion in a client with any form of dementia can be a symptom of infection (e.g., pneumonia, urinary tract infection), electrolyte imbalance, or delirium. Likewise, a sudden change in muscle tone (usually increased tone) in the client with a neurologic disorder (adult or child) can signal an infectious process.

TABLE 4-3

Systemic Conditions Associated with Confusional States

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CHF, congestive heart failure; TIA, transient ischemic attack; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Modified from Dains JE, Baumann LC, Scheibel P: Advanced health assessment & clinical diagnosis in primary care, ed 2, St. Louis, 2003, Mosby; p 425.

Nutritional Status

Nutrition is an important part of growth and development and recovery from infection, illness, wounds, and surgery. Clients can exhibit signs of malnutrition or overnutrition (obesity).

Be aware in the health history of any risk factors for nutritional deficiencies (Box 4-3). Remember that some medications can cause appetite changes and that psychosocial factors such as depression, eating disorders, drug or alcohol addictions, and economic variables can affect nutritional status.

It may be necessary to determine the client’s ideal body weight by calculating the body mass index (BMI).13,14 Several websites are available to help anyone make this calculation. There is a separate website for children and teens sponsored by the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.15

Whenever nutritional deficiencies are suspected, notify the physician and/or request a referral to a registered dietitian.

Body and Breath Odors

Odors may provide some significant clues to overall health status. For example, a fruity (sweet) breath odor (detectable by some but not all health care professionals) may be a symptom of diabetic ketoacidosis. Bad breath (halitosis) can be a symptom of dental decay, lung abscess, throat or sinus infection, or gastrointestinal (GI) disturbances from food intolerances, Helicobacter pylori bacteria, or bowel obstruction. Keep in mind that ethnic foods and alcohol can affect breath and body odor.

Clients who are incontinent (bowel or bladder) may smell of urine, ammonia, or feces. It is important to ask the client about any unusual odors. It may be best to offer an introductory explanation with some follow-up questions:

Vital Signs

The need for therapists to assess vital signs, especially pulse and blood pressure is increasing.16 Without the benefit of laboratory values, physical assessment becomes much more important. Vital signs, observations, and reported associated signs and symptoms are among the best screening tools available to the therapist.

Vital sign assessment is an important tool because high blood pressure is a serious concern in the United States. Many people are unaware they have high blood pressure. Often primary orthopedic clients have secondary cardiovascular disease.17

Physical therapists practicing in a primary care setting will especially need to know when and how to assess vital signs. The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice18 recommends that heart rate (pulse) and blood pressure measurements be included in the examination of new clients. Exercise professionals are strongly encouraged to measure blood pressure during each visit.19

Taking a client’s vital signs remains the single easiest, most economic, and fastest way to screen for many systemic illnesses. All the vital signs are important (Box 4-4); temperature and blood pressure have the greatest utility as early screening tools for systemic illness or disease, while pulse, blood pressure, and oxygen (O2) saturation level offer valuable information about the cardiovascular/pulmonary systems.

As an aside comment: using vital signs is an easy, yet effective way to document outcomes. In today’s evidence-based practice, the therapist can use something as simple as pulse or blood pressure to document changes that occur with intervention.

For example, if ambulating with a client morning and afternoon results in no change in ease of ambulation, speed, or distance, consider taking blood pressure, pulse, and O2 saturation levels before and after each session. Improvement in O2 saturation levels or faster return to normal of heart rate after exercise are just two examples of how vital signs can become an important part of outcomes documentation.

Assessment of baseline vital signs should be a part of the initial data collected so that correlations and comparisons with future values are available when necessary. The therapist compares measurements taken against normal values and also compares future measurements to the baseline units to identify significant changes (normalizing values or moving toward abnormal findings) for each client.

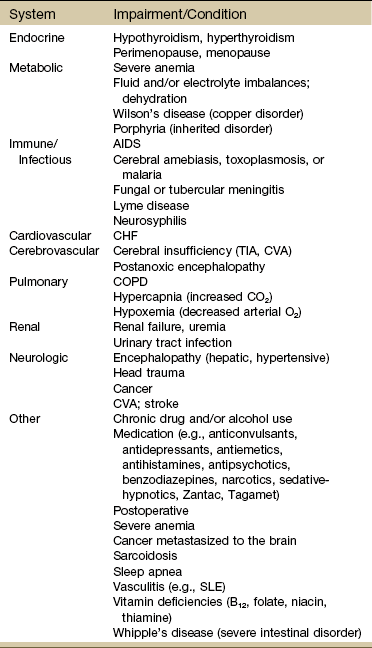

Normal ranges of values for the vital signs are provided for the therapist’s convenience. However, these ranges can be exceeded by a client and still represent normal for that person. Keep in mind that many factors can affect vital signs, especially pulse and blood pressure (Table 4-4). Substances such as alcohol, caffeine, nicotine, and cocaine/cocaine derivatives as well as pain and stress/anxiety can cause fluctuations in blood pressure. Adults who monitor their own blood pressure may report wide fluctuations without making the association between these and other factors listed. It is the unusual vital sign in combination with other signs and symptoms, medications, and medical status that gives clinical meaning to the pulse rate, blood pressure, and temperature.

TABLE 4-4

Factors Affecting Pulse and Blood Pressure

SBP, Systolic blood pressure; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme.

*Conditions, such as chronic kidney disease, renovascular disorders, primary aldosteronism, and coarctation of the aorta, are identifiable causes of elevated blood pressure. Chronic overtraining in athletes, use of steroids and/or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and large increases in muscle mass can also contribute to hypertension.38 Treatment for hypertension, dehydration, heart failure, heart attack, arrhythmias, anaphylaxis, shock (from severe infection, stroke, anaphylaxis, major trauma), and advanced diabetes can cause low blood pressure.

From Goodman CC, Fuller K: Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2009, WB Saunders.

Pulse Rate

The pulse reveals important information about the client’s heart rate and heart rhythm. A resting pulse rate (normal range: 60 to 100 beats per minute [bpm]) taken at the carotid artery or radial artery (preferred sites) pulse point should be available for comparison with the pulse rate taken during treatment or after exercise. A pulse rate above 100 bpm indicates tachycardia; below 60 bpm indicates bradycardia.

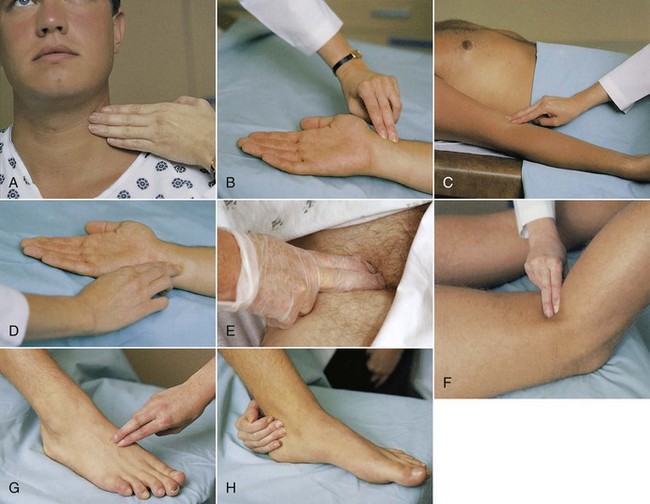

Do not rely on pulse oximeter devices for pulse rate because these units often take a sample pulse rate that reflects a mean average and may not reveal dysrhythmias (e.g., a regular irregular pulse rate associated with atrial fibrillation). It is recommended that the pulse always be checked in two places in older adults and in anyone with diabetes (Fig. 4-1). Pulse strength (amplitude) can be graded as

Fig. 4-1 Pulse points. The easiest and most commonly palpated pulses are the (A) carotid pulse and (B) radial pulse. Other pulse points include brachial pulse (C), ulnar pulse (D), femoral pulse (E), popliteal pulse (knee slightly flexed) (F), dorsalis pedis (G), and posterior tibial (H). The anterior tibial pulse becomes the dorsalis pedis and is palpable where the artery lies close to the skin on the dorsum of the foot. Peripheral pulses are more difficult to palpate in older adults and anyone with peripheral vascular disease. (From Potter PA: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 7, St. Louis, 2009, Mosby.)

| 0 | Absent, not palpable |

| 1+ | Pulse diminished, barely palpable |

| 2+ | Easily palpable, normal |

| 3+ | Full pulse, increased strength |

| 4+ | Bounding, too strong to obliterate |

Keep in mind that taking the pulse measures the peripheral arterial wave propagation generated by the heart’s contraction—it is not the same as measuring the true heart rate (and should not be recorded as heart rate when measured by palpation). A true measure of heart rate requires auscultation or electrocardiographic recording of the electrical impulses of the heart. The distinction between pulse rate and heart rate becomes a matter of concern in documentation liability and even greater importance for individuals with dysrhythmias. In such cases, the output of blood by some beats may be insufficient to produce a detectable pulse wave that would be discernible with an electrocardiogram.20

Pulse amplitude (weak or bounding quality of the pulse) gives an indication of the circulating blood volume and the strength of left ventricle ejection. Normally, the pulse increases slightly with inspiration and decreases with expiration. This slight change is not considered significant.

Pulse amplitude that fades with inspiration instead of strengthening and strengthens with expiration instead of fading is paradoxic and should be reported to the physician. Paradoxic pulse occurs most commonly in clients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) but is also observed in clients with constrictive pericarditis.21

Constriction or compression around the heart from pericardial effusion, tension pneumothorax, pericarditis with fluid, or pericardial tamponade may be associated with paradoxical pulse. When the person breathes in, the increased mechanical pressure of inspiration added to the physiologic compression from the underlying disease prevents the heart from contracting fully and results in a reduced pulse. When the person breathes out, the pressure from chest expansion is reduced and the pulse increases.

A pulse increase with activity of more than 20 bpm lasting for more than 3 minutes after rest or changing position should also be reported. Other pulse abnormalities are listed in Box 4-5.

The resting pulse may be higher than normal with fever, anemia, infections, some medications, hyperthyroidism, anxiety, or pain. A low pulse rate (below 60 bpm) is not uncommon among trained athletes. Medications, such as beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers, can also prevent the normal rise in pulse rate that usually occurs during exercise. In such cases the therapist must monitor rates of perceived exertion (RPE) instead of pulse rate.

When taking the resting pulse or pulse during exercise, some clinicians measure the pulse for 15 seconds and multiply by 4 to get the rate per minute. For a quick assessment, measure for 6 seconds and add a zero. A 6-second pulse count can result in an error of 10 bpm if a 1-beat error is made in counting. For screening purposes, it is always best to palpate the pulse for a full minute. Longer pulse counts give greater accuracy and provide more time for detection of some dysrhythmias (Box 4-6).19

Pulse assessment following vascular injuries (especially dislocation of the knee) should not be relied upon as the only diagnostic testing procedure as occult arterial injuries can be present even when pulses are normal. A meta-analysis of 284 dislocated knees concluded that abnormal pulse examinations have a sensitivity of .79 and specificity of .91 for detection of arterial injuries.22,23 On the other hand, there are reports of normal pulse examinations at the time of the initial knee injury in people who later developed ischemia leading to amputation.24,25

Respirations

Try to assess the client’s breathing without drawing attention to what is being done. This measure can be taken right after counting the pulse while still holding the client’s wrist.

Count respirations for 1 minute unless respirations are unlabored and regular, in which case the count can be taken for 30 seconds and multiplied by 2. The rise and fall of the chest equals 1 cycle.

The normal rate is between 12 and 20 breaths per minute. Observe rate, excursion, effort, and pattern. Note any use of accessory muscles and whether breathing is silent or noisy. Watch for puffed cheeks, pursed lips, nasal flaring, or asymmetric chest expansion. Changes in the rate, depth, effort, or pattern of a client’s respirations can be early signs of neurologic, pulmonary, or cardiovascular impairment.

Pulse Oximetry

O2 saturation on hemoglobin (SaO2) and pulse rate can be measured simultaneously using pulse oximetry. This is a noninvasive, photoelectric device with a sensor that can be attached to a well-perfused finger, the bridge of the nose, toe, forehead, or ear lobe. Digital readings are less accurate with clients who are anemic, undergoing chemotherapy, or who use fingernail polish or nail acrylics. In such cases, attach the sensor to one of the other accessible body parts.

The sensor probe emits red and infrared light, which is transmitted to the capillaries. When in contact with the skin, the probe measures transmitted light passing through the vascular bed and detects the relative amount of color absorbed by the arterial blood. The SaO2 level is calculated from this information.

The normal SaO2 range at rest and during exercise is 95% to 100%. Referral for medical evaluation is advised when resting saturation levels fall below 90%. The exception to the normal range listed here is for clients with a history of tobacco use and/or COPD. Some individuals with COPD tend to retain carbon dioxide and can become apneic if the oxygen levels are too high. For this reason, SaO2 levels are normally kept lower for this population.

The drive to breathe in a healthy person results from an increase in the arterial carbon dioxide level (PaCO2). In the normal adult, increased CO2 levels stimulate chemoreceptors in the brainstem to increase the respiratory rate. With some chronic lung disorders these central chemoreceptors may become desensitized to PaCO2 changes resulting in a dependence on the peripheral chemoreceptors to detect a fall in arterial oxygen levels (PaO2) to stimulate the respiratory drive.

Too much oxygen delivered as a treatment can depress the respiratory drive in those individuals with COPD who have a dampening of the CO2 drive. Monitoring respiratory rate, level of oxygen administered by nasal canula, and SaO2 levels is very important in this client population.

Some pulmonologists agree that supplemental oxygen levels can be increased during activity without compromising the individual because they will “blow it (carbon dioxide) off” anyway. To our knowledge, there is no evidence yet to support this clinical practice.

Any condition that restricts blood flow (including cold hands) can result in inaccurate SaO2 readings. Relaxation and physiologic quieting techniques can be used to help restore more normal temperatures in the distal extremities. A handheld device such as the PhysioQ26 can be used by the client to improve peripheral circulation. Do not apply a pulse oximetry sensor to an extremity with an automatic blood pressure cuff.27

SaO2 levels can be affected also by positioning because positioning can impact a person’s ability to breathe. Upright sitting in individuals with low muscle tone or kyphosis can cause forward flexion of the thoracic spine compromising oxygen intake. Tilting the person back slightly can open the trunk, ease ventilation, and improve SaO2 levels.28 Using SaO2 levels may be a good way to document outcomes of positioning programs for clients with impaired ventilation.

Other factors affecting pulse oximeter readings can include nail polish and nail coverings, irregular heart rhythms, hyperemia (increased blood flow to the area), motion artifact, pressure on the sensor, electrical interference, and venous congestion.20

In addition to SaO2 levels, assess other vital signs, skin and nail bed color and tissue perfusion, mental status, breath sounds, and respiratory pattern for all clients using pulse oximetry. If the client cannot talk easily whether at rest or while exercising, SaO2 levels are likely to be inadequate.

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the measurement of pressure in an artery at the peak of systole (contraction of the left ventricle) and during diastole (when the heart is at rest after closure of the aortic valve, which prevents blood from flowing back to the heart chambers). The measurement (in mm Hg) is listed as:

BP depends on many factors; the normal range differs slightly with age and varies greatly among individuals (see Table 4-4). Normal systolic BP (SBP) ranges from 100 to 120 mm Hg, and diastolic BP (DBP) ranges from 60 to 80 mm Hg. Highly trained athletes may have much lower values. Target ranges for BP are listed in Table 4-5 and Box 4-7.

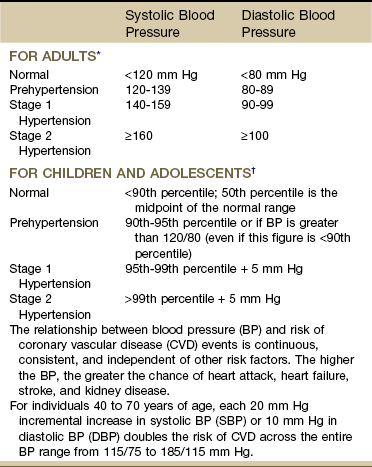

TABLE 4-5

Classification of Blood Pressure

*From The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, NIH Publication No. 03-5233, May 2003. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) www.nhlbi.nih.gov/.

†From National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI): Fourth Report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents, Pediatrics 114(2):555-576, August 2004.

Assessing Blood Pressure: BP should be taken in the same arm and in the same position (supine or sitting) each time it is measured. The baseline BP values can be recorded on the Family/Personal History form (see Fig. 2-2).

Cuff size is important and requires the bladder width-to-length be at least 1 : 2. The cuff bladder should encircle at least 80% of the arm. BP measurements are overestimated with a cuff that is too small; if a cuff is too small, go to the next size up. Keep in mind that if the cuff is too large, falsely lower BPs may be recorded.29

Do not apply the blood pressure cuff above an intravenous (IV) line where fluids are infusing or an arteriovenous (AV) shunt, on the same side where breast or axillary surgery has been performed, or when the arm or hand have been traumatized or diseased. Until research data supports a change, it is recommended that clients who have undergone axillary node dissection (ALND) avoid having BP measurements taken on the affected side.

Although it is often recommended that anyone who has had bilateral axillary node dissection should have BP measurements taken in the leg, this is not standard clinical practice across the United States.30 Leg pressures can be difficult to assess and inaccurate.

Some oncology staff advise taking BP in the arm with the least amount of nodal dissection. Technique in measuring BP is a key factor in all clients, especially those with ALND (Box 4-8).

A common mistake is to pump the BP cuff up until the systolic measurement is 200 mm Hg and then take too long to lower the pressure or to repeat the measurement a second time without waiting. Repeating the BP without a 1-minute wait time may damage the blood vessel and set up an inflammatory response.31 This poor technique is to be avoided, especially in clients at risk for lymphedema or who already have lymphedema.

Take the BP twice at least a minute apart in both arms. If both measurements are within 5 mm Hg of each other, record this as the resting (baseline) measurement. If not, wait 1 minute and take the BP a third time. Monitor the BP in the arm with the highest measurements.21 Record measurements exactly; do not round numbers up or down as this can result in inaccuracies.32

For clients who have had a mastectomy without ALND (i.e., prophylactic mastectomy), BP can be measured in either arm. These recommendations are to be followed for life.33

Until automated BP devices are improved enough to ensure valid and reliable measurements, the BP response to exercise in all clients should be taken manually with a BP cuff (sphygmomanometer) and a stethoscope.33

It is advised to invest in the purchase of a well-made, reliable stethoscope. Older models with tubing long enough to put the earpieces in your ears and still place the bell in a lab coat pocket should be replaced. Tubing should be no more than 50 to 60 cm (12 to 15 inches) and 4 mm in diameter. Longer and wider tubing can distort transmitted sounds.34

For the student or clinician learning to take vital signs, it may be easier to hear the BP (tapping, Korotkoff) sounds in adults using the left arm because of the closer proximity to the left ventricle. Arm position does make a difference in BP readings. BP measurements are up to 10% higher when the elbow is at a right angle to the body with the elbow flexed at heart level. The preferred position is seated with the arms parallel and extended in a forward direction (if supine, then parallel to the body).35

It is more accurate to evaluate consecutive BP readings over time rather than using an isolated measurement for reporting BP abnormalities. BP also should be correlated with any related diet or medication.

Before reporting abnormal BP readings, measure both sides for comparison, re-measure both sides, and have another health professional check the readings. Correlate BP measurements with other vital signs, and screen for associated signs and symptoms such as pallor, fatigue, perspiration, and/or palpitations. A persistent rise or fall in BP requires medical attention and possible intervention.

Pulse Pressure: The difference between the systolic and diastolic pressure readings (SBP − DBP) is called pulse pressure normally around 40 mm Hg. Pulse pressure is an index of vascular aging (i.e., loss of arterial compliance and indication of how stiff the arteries are). A widened resting pulse pressure often results from stiffening of the aorta secondary to atherosclerosis. Resting pulse pressure consistently greater than 60 to 80 mm Hg is a yellow (caution) flag and is a risk factor for new onset of atrial fibrillation.36

Widening of the pulse pressure is linked to a significantly higher risk of stroke and heart failure after the sixth decade. Some BP medications increase resting pulse pressure width by lowering diastolic pressure more than systolic while others (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors) can lower pulse pressure.37

Narrowing of the resting pulse pressure (usually by a drop in SBP as the DBP rises) can suggest congestive heart failure (CHF) or a significant blood loss such as occurs in hypovolemic shock. A high pulse pressure accompanied by bradycardia is a sign of increased intracranial pressure and requires immediate medical evaluation.

In a normal, healthy adult, the pulse pressure generally increases in direct proportion to the intensity of exercise as the SBP increases and DBP stays about the same.38 A difference of more than 80 to 100 mm Hg taken during or right after exercise should be evaluated carefully. In a healthy adult, pulse pressure will return to normal within 3 to 10 minutes following moderate exercise.

The key is to watch for pulse pressures that are not accommodating during exercise. Expect to see the systolic rise slightly while diastolic stays the same. If diastolic drops while systolic rises or if the pulse width exceeds 100 mm Hg, further assessment and evaluation is needed. Depending on all other parameters (e.g., general health of the client, past medical history, medications, concomitant associated signs and symptoms), the therapist may monitor pulse pressures over a few sessions and look for a pattern (or lack of pattern) to report if/when generating a medical consult.39

Variations in Blood Pressure: There can be some normal variation in SBP from side to side (right extremity compared to left extremity). This is usually no more than 5 to 10 mm Hg DBP or SBP (arms) and 10 to 40 mm Hg SBP (legs). A difference of 10 mm Hg or more in either systolic or diastolic measurements from one extremity to the other may be an indication of vascular problems (look for associated symptoms; in the upper extremity test for thoracic outlet syndrome).

Normally the SBP in the legs is 10% to 20% higher than the brachial artery pressure in the arms. BP readings that are lower in the legs as compared with the arms are considered abnormal and should prompt a medical referral for assessment of peripheral vascular disease.33

With a change in position (supine to sitting), the normal fluctuation of BP and heart rate increases slightly (about 5 mm Hg for systolic and diastolic pressures and 5 to 10 bpm in heart rate).

Systolic pressure increases with age and with exertion in a linear progression. If systolic pressure does not rise as workload increases, or if this pressure falls, it may be an indication that the functional reserve capacity of the heart has been exceeded.

The deconditioned, menopausal woman with coronary heart disease (CHD) requires careful monitoring, especially in the presence of a personal or family history of heart disease and myocardial infarct (personal or family) or sudden death in a family member.

On the other hand, women of reproductive age taking birth control pills may be at increased risk for hypertension, heart attack, or stroke. The risk of a cardiovascular event is very low with today’s low-dose oral contraceptives. However, smoking, hypertension, obesity, undiagnosed cardiac anomalies, and diabetes are factors that increase a woman’s risk for cardiovascular events. Any woman using oral contraceptives who presents with consistently elevated BP values must be advised to see her physician for close monitoring and follow-up.40,41

The left ventricle becomes less elastic and more noncompliant as we age. The same amount of blood still fills the ventricle, but the pumping mechanism is less effective. The body compensates to maintain homeostasis by increasing the blood pressure. BP values greater than 120 mm Hg (systolic) and more than 80 mm Hg (diastolic) are treated with lifestyle modifications first then medication.

Blood Pressure Changes with Exercise: As mentioned, the SBP increases with increasing levels of activity and exercise in a linear fashion. In a healthy adult under conditions of minimal to moderate exercise, look for normal change (increase) in SBP of 20 mm Hg or more.

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) suggests the normal SBP response to incremental exercise is a progressive rise, typically 10 mm + 2 mm Hg for each metabolic equivalent (MET) where 1 MET = 3.5 mL O2/kg/min. Expect to see a 40 to 50 mm change in SBP with intense exercise (again, this is in the healthy adult). These values are less likely with individuals taking BP medications, anyone with a significant history of heart disease, and well-conditioned athletes.

Diastolic should be the same side to side with less than 10 mm Hg difference observed. DBP generally remains the same or decreases slightly during progressive exercise.38

In an exercise-testing situation, the ACSM recommends stopping the test if the SBP exceeds 260 mm Hg.38 In a clinical setting without the benefit of cardiac monitoring, exercise or activity should be reduced or stopped if the systolic pressure exceeds 200 mm Hg.

This is a general guideline that can be changed according to the client’s age, general health, use of cardiac medications, and other risk factors. DBP increases during upper extremity exercise or isometric exercise involving any muscle group. Activity or exercise should be monitored closely, decreased, or halted if the diastolic pressure exceeds 100 mm Hg.

This is a general (conservative) guideline when exercising a client without the benefit of cardiac testing (e.g., electrocardiogram [ECG]). This stop-point is based on the ACSM guideline to stop exercise testing at 115 mm Hg DBP. Other sources suggest activity should be decreased or stopped if the DBP exceeds 130 mm Hg.42

Other warning signs to moderate or stop exercising include the onset of angina, dyspnea, and heart palpitations. Monitor the client for other signs and symptoms such as fever, dizziness, nausea/vomiting, pallor, extreme diaphoresis, muscular cramping or weakness, and incoordination. Always honor the client’s desire to slow down or stop.

Hypertension (See Further Discussion on Hypertension in Chapter 6): In recent years, an unexpected increase in illness and death caused by hypertension has prompted the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to issue new guidelines for more effective BP control. More than one in four Americans has high blood pressure, increasing their risk for heart and kidney disease and stroke.43

In adults hypertension is a systolic pressure above 140 mm Hg or a diastolic pressure above 90 mm Hg. Consistent BP measurements between 120 and 139 (systolic) and between 80 and 89 diastolic is classified as pre-hypertensive. The overall goal of treating clients with hypertension is to prevent morbidity and mortality associated with high blood pressure. The specific objective is to achieve and maintain arterial blood pressure below 120/80 mm Hg, if possible (Box 4-9).34

The older adult taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is at risk for increased BP because these drugs are potent renal vasoconstrictors. Monitor BP carefully in these clients and look for sacral and lower extremity edema. Document and report these findings to the physician. Use the risk factor analysis for NSAIDs presented in Chapter 2 (see Box 2-13 and Table 2-6).

Always beware of masked hypertension (normal in the clinic but periodically high at home) and white-coat hypertension, a clinical condition in which the client has elevated BP levels when measured in a clinic setting by a health care professional. In such cases, BP measurements are consistently normal outside of a clinical setting.

Masked hypertension may affect up to 10% of adults; white-coat hypertension occurs in 15 to 20% of adults with stage I hypertension.44 These types of hypertension are more common in older adults. Antihypertensive treatment for white coat hypertension may reduce office BP but may not affect ambulatory BP. The number of adults who develop sustained high BPs is much higher among those who have masked or white-coat hypertension.44

At-home BP measurements can help identify adults with masked hypertension, white-coat hypertension, ambulatory hypertension, and individuals who do not experience the usual nocturnal drop in BP (decrease of 15 mm Hg), which is a risk factor for cardiovascular events.45 Excessive morning BP surge is a predictor of stroke in older adults with known hypertension and is also a red-flag sign.46 Medical referral is indicated in any of these situations.

Hypertension in African Americans: Nearly 40% of African Americans suffer from heart disease and 13% have diabetes. Hypertension contributes to these conditions or makes them worse. African Americans are significantly more likely to die of high BP than the general public because current treatment strategies have been unsuccessful.47,48

Guidelines for treating high blood pressure in African Americans have been issued by the International Society on Hypertension in Blacks (ISHIB).49 The ISHIB recommends a blood pressure target of less than 130/80 mm Hg for African Americans with BP screening for all African-American adults and early prevention for anyone in the pre-hypertensive range. Aggressive treatment for hypertension is advised using drug combinations.48

The therapist can incorporate blood pressure screening into any evaluation for clients with ethnic risk factors. Any client of any ethnic background with risk factors for hypertension should also be screened (see Table 6-6).

Hypertension in Hispanics: The Hispanic population in the United States is expected to be reported by the 2010 census as the largest minority group in the nation. Research on hypertension among Hispanics has shown that their incidence of high BP is greater than that of whites and Asians and less than that of blacks. More Hispanics than whites have undiagnosed hypertension and are generally less knowledgeable in heart disease prevention. Factors that contribute to elevated BP in Hispanics include high rates of obesity and diabetes, as well as a genetic predisposition and low socioeconomic status.50 With equal access to medical care and medication, Hispanic men and women have as good or greater chance as non-Hispanics of controlling their high BP.51

Hypertension in Children and Adolescents52: Up to 3% of children under age 18 also have hypertension. New guidelines for children have been published by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (see Table 4-5). Tables with BP levels for boys and girls by age and height percentile are available.52

The updated BP tables for children and adolescents are based on recently revised child height percentiles. Any child with readings above the 95th percentile for gender, age, and height on three separate occasions is considered to have hypertension. The 50th percentile has been added to the tables to provide the clinician with the BP level at the midpoint of the normal range.

Under the new guidelines, children whose readings fall between the 90th and 95th percentile are now considered to have pre-hypertension. Earlier guidelines called this category “high normal.”

The long-term health risks for hypertensive children and adolescents can be substantial; therefore it is important that elevated BP is recognized early and measures taken to reduce risks and optimize health outcomes.52

Children ages 3 to 18 seen in any medical setting should have the BP measured at least once during each health care episode. The preferred method is auscultation with a BP cuff and stethoscope. Correct measurement requires a cuff that is appropriate to the size of the child’s upper arm.

The right arm is preferred with children for comparison with standard tables and in the possible event there is a coarctation of the aorta (see Fig. 6-6), which can lead to a false low reading in the left arm.53

Preparation of the child can affect the BP level as much as technique. The child should be seated with feet and back supported. The right arm should be supported parallel to the floor with the cubital fossa at heart level.54,55 Children can be affected by white-coat hypertension as much as adults. Follow the same guidelines for adults as presented in Box 4-8.

Hypotension: Hypotension is a systolic pressure below 90 mm Hg or a diastolic pressure below 60 mm Hg. A BP level that is borderline low for one person may be normal for another. When the BP is too low, there is inadequate blood flow to the heart, brain, and other vital organs.

The most important factor in hypotension is how the BP changes from the normal condition. Most normal BPs are in the range of 90/60 mm Hg to 120/80 mm Hg, but a significant change, even as little as 20 mm Hg, can cause problems for some people.

Lower standing SBP (less than 140 mm Hg) even within the normotensive range is an independent predictor of loss of balance and falls in adults over age 65.56 DBP does not appear to be related to falls. Older adult women with lower standing SBP and a history of falls are at greatest risk. The therapist has an important role in educating clients with these risk factors in preventing falls and related accidents. See discussion in Chapter 2 related to taking a history of falls.

In older adults a decrease in BP may be an early warning sign of Alzheimer’s disease. DBP below 70 or declines in systolic pressure equal to or greater than 15 mm Hg over a period of 3 years raises the risk of dementia in adults 75 or older. For each 10-point drop in pressure, the risk of dementia increases by 20%.57,58

It is unclear if the steady drop in BP during the 3 years before a dementia diagnosis is a cause or effect of dementia as reduced blood flow to the brain accelerates the development of dementia. Perhaps brain cell degeneration characteristic of dementia damages parts of the brain that regulate BP.57

Postural Orthostatic Hypotension: A common cause of low BP is orthostatic hypotension (OH), defined as a sudden drop in BP when changing positions, usually moving from supine to an upright position.

Physiologic responses of the sympathetic nervous system decline with aging putting them at greater risk for OH. Older adults are prone to falls from a combination of OH and antihypertensive medications. Volume depletion and autonomic dysfunction are the most common causes of OH (see Table 2-5).

Postural OH is more accurately defined as a decrease in SBP of at least 20 mm Hg or decrease in diastolic pressure of at least 10 mm Hg and a 10% to 20% increase in pulse rate. Changes must be noted in both the BP and the pulse rate with change in position (supine to sitting, sitting to standing) (Box 4-10 and Case Example 4-1).45

The client should lie supine 2 to 3 minutes prior to BP and pulse check. At least a 1-minute wait is recommended after each subsequent position change before taking the BP and pulse. Standing postural orthostatic hypotension is measured after 3 to 5 minutes of quiet standing. Food ingestion, time of day, age, and hydration can impact this form of hypotension, as can a history of Parkinsonism, diabetes, or multiple myeloma.43

Throughout the procedure assess the client for signs and symptoms of hypotension, including dizziness, lightheadedness, pallor, diaphoresis, or syncope (or arrhythmias if using a cardiac monitor). Assist the client to a seated or supine position if any of these symptoms develop and report the results. Do not test the client in the standing position if signs and symptoms of hypotension occur while sitting.

Gravitational effects on the circulatory system can cause a 10 mm Hg drop in SBP when a person changes position from supine to sitting to standing. This drop usually occurs without symptoms as the body quickly compensates to ensure there is no reduction in cardiac output.

In clients on prolonged bed rest or on antihypertensive drug therapy, there may be either no reflexive increase in heart rate or a sluggish vasomotor response. These clients may experience larger drops in BP and often experience lightheadedness.

Other clients at risk for postural OH include those who have just donated blood, anyone with autonomic nervous system disease or dysfunction, and postoperative patients. Other risk factors for OH in aging adults include hypovolemia associated with dehydration and the overuse of diuretics, anticholinergic medications, antiemetics, and various over-the-counter (OTC) cough/cold preparations.

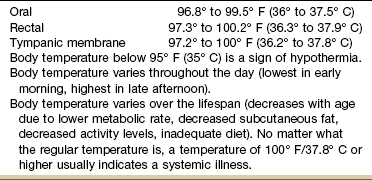

Core Body Temperature

Normal body temperature is not a specific number but a range of values that depends on factors such as the time of day, age, medical status, medication use, activity level, or presence of infection. Oral body temperature ranges from 36° to 37.5° C (96.8° to 99.5° F), with an average of 37° C (98.6° F) (Table 4-6). Hypothermic core temperature is defined as less than 35° C (95° F). Hyperthermia is defined as a temperature greater than 38° C (100.4° F).

Older adults (over age 65) are less likely to have a fever even in the presence of severe infection, so the predictive value of taking the body temperature is less. Due to age-related changes in the thermoregulatory system, they are also more likely to develop hypothermia than young adults. There is a tendency among the aging population to develop an increase in temperature on hospital admission or in response to any change in homeostasis. However, some persons with infectious disease remain afebrile, especially the immunocompromised and those with chronic renal disease, alcoholics, and older adults. A low-grade fever can be an early sign of life-threatening infections (most commonly pneumonia, urinary tract infection). Unexplained fever in adolescents may be a manifestation of drug abuse or endocarditis.

Postoperative fever is common and may be from an infectious or noninfectious cause. Medical evaluation is needed to make this determination. In the home health setting, wound infection, abscess formation, or peritonitis may appear as a hectic fever pattern 3 to 4 days postoperatively with increases and declines of body temperature but no return to baseline (normal). Such a situation would warrant telephone consultation with the physician’s office nurse.

Any client who has back, shoulder, hip, sacroiliac, or groin pain of unknown cause must have a temperature reading taken. Temperature should also be assessed for any client who has constitutional symptoms (see Box 1-3), especially “sweats” (gradual increase followed by a sudden drop in body temperature), pain, or symptoms of unknown etiologic basis and for clients who have not been medically screened by a physician. Ask about the presence of other signs and symptoms of infection.

When measuring body temperature, the therapist should ask if the person’s normal temperature differs from 37° C (98.6° F). A persistent elevation of temperature over time is a red-flag sign; a single measurement may not be sufficient to cause concern. Any measurement outside of normal for that individual should be rechecked.

It is also important to ask whether the client has taken aspirin (or other NSAIDs) or acetaminophen (Tylenol) to reduce the fever, which might mask an underlying problem. Clients taking dopamine blockers, such as Thorazine, Mellaril, or the less commonly used Navane for schizophrenia, have a lowered “normal” temperature (around 96° F/35.6° C). Anyone who is chronically immunosuppressed (such as an organ transplant recipient, a person being treated with chemotherapy, and any older adult) may have an infection without elevation of temperature.

When using a tympanic membrane (ear) thermometer, perform a gentle ear tug to straighten the ear canal. In a child, pull the ear straight back; in an adult, pull it slightly upward and backward. While holding the ear in this position, use a small rotation movement to insert the probe gently and slowly.59

The probe must penetrate at least one-third of the external ear canal to prevent air temperature from affecting the reading. Aim the probe toward the tympanic membrane where it will indirectly measure core body temperature by taking infrared temperature readings of the tympanic membrane (eardrum).59

Temperatures can vary from side to side, so record which ear was used and try to use the same ear each time the temperature is recorded. For the client with hearing aid(s), take the temperature in the ear without an aid. Or, if hearing aids are present in both ears, remove one hearing aid and wait 20 minutes before measuring that side. The presence of excessive earwax will prevent an accurate reading.

There are some additional concerns reported in the literature about the accuracy of tympanic thermometers with evidence of significant variability possibly related to the condition of the censor, presence of ear wax, placement in the ear canal, operator error, and maintenance of the equipment.60-62 Such concerns may be more important in critical care ICUs compared with outpatient screening, but no studies comparing these two populations have been published.

Newer handheld digital forehead thermometers are noninvasive and are quick and easy to use. The forehead plastic temperature strip (forehead thermometer, fever strip) and the pacifier thermometer for children are not the most reliable methods to take a temperature.

The therapist should use discretionary caution with any client who has a fever. Exercise with a fever stresses the cardiopulmonary system, which may be further complicated by dehydration. Severe dehydration can occur from vomiting, diarrhea, medications (e.g., diuretics), or heat exhaustion.

Clients at greatest risk of dehydration include postoperative patients, aging adults, and athletes. Severe fluid volume deficit can cause vascular collapse and shock. Clients at risk of shock include burn or trauma patients, clients in anaphylactic shock or diabetic ketoacidosis, and individuals experiencing severe blood loss.

Walking Speed: The Sixth Vital Sign

Walking speed is used by some as a general indicator of function63 and as such, a reflection of many variables such as health status, motor control, muscle strength, and endurance to name only a few. It is a reliable, valid, and sensitive measure of functional ability with additional predictive value in assessing future health status, functional decline, potential for hospitalization, and even mortality.64

The test is conducted using a timed 10-meter walk test on a 20-meter long straight path. Complete descriptions of the test and expected results are available.63-66 As a screening tool, walking speed may not indicate the presence of systemic pathology, but as specialists in human movement and function, the therapist can use it as a practical and predictive “vital sign” of general health that can be used to monitor change (improvement or decline) in health and function.

Techniques of Physical Examination

There are four simple techniques used in the medical physical examination: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. Percussion and some auscultation techniques require advanced clinical skill and are beyond the scope of a screening examination.

Throughout any screening examination the therapist also assesses function of the integument, musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, and cardiopulmonary systems. Assessment techniques are relatively simple; it is using the finding that is more difficult. The saying, “What one knows, one sees” underscores the idea that knowledge of physical assessment techniques and experience in performing these are extremely important and come from practice.

Inspection

Good lighting and good exposure are essential. Always compare one side to the other. Assess for abnormalities in all of the following:

| Texture | Tenderness |

| Size | Shape, contour, symmetry |

| Position, alignment | Mobility or movement |

| Color | Location |

The therapist should try to follow the same pattern every time to decrease the chances of missing an assessment parameter and to increase accuracy and thoroughness.

Palpation

Palpation is used to discriminate between textures, dimensions, consistencies, and temperature. It is used to define things that are inspected and to reveal things that cannot be inspected. Textures are best detected using the fingertips, whereas dimension or contours are detected using several fingers, the entire hand, or both hands, depending on the area being examined.

Inspection and palpation are often performed at the same time; be sure and look at the client and not at your hands. Muscle tension interferes with palpation so the client must be positioned and draped appropriately in a room with adequate lighting and temperature.

Assess skin temperature with both hands at the same time. The back of the therapist’s hands sense temperature best because of the thin layer of skin. Use the palm or heel of the hand to assess for vibration. The finger pads are best to assess texture, size, shape, position, pulsation, consistency, and turgor. Heavy or continued pressure dulls the examiner’s palpatory skill and sensation.

Light palpation is used first, looking for areas of tenderness followed by deep palpation to examine organs or look for masses and elicit deep pain. Light palpation (skin is depressed up to  to

to  inch) is also used to assess texture, temperature, moisture, pulsations, vibrations, and superficial lesions. Deep palpation is used for assessing abdominal structures. During deep palpation, enough pressure is used to depress the skin up to 1 inch; applying too much pressure decreases sensation.

inch) is also used to assess texture, temperature, moisture, pulsations, vibrations, and superficial lesions. Deep palpation is used for assessing abdominal structures. During deep palpation, enough pressure is used to depress the skin up to 1 inch; applying too much pressure decreases sensation.

Tender or painful areas are assessed last while carefully observing the client’s face for signs of discomfort.

Percussion

Percussion (tapping) is used to determine the size, shape, and density of tissue using sound created by vibration. Percussion can also detect the presence of fluid or air in a body cavity such as the abdominal cavity. Most percussive techniques are beyond the scope of a screening examination and are not discussed in detail.

Percussion can be done directly over the client’s skin using the fingertip of the examiner’s index finger. Indirect percussion is performed by placing the middle finger of the examiner’s nondominant hand firmly against the client’s skin then striking above or below the interphalangeal joint with the pad of the middle finger of the dominant hand. The palm and fingers stay off the skin during indirect percussion. Blunt percussion using the ulnar surface of the hand or fist to strike the body surface (directly or indirectly) detects pain from infection or inflammation (see Fig. 4-54).

The examiner must be careful not to dampen the sound by dull percussing (sharp percussion is needed), holding a finger too loosely on the body surface, or resting the hand on the body surface. Percussive sounds lie on a continuum from tympany to flat based on density of tissue.

Auscultation

Some sounds of the body can be heard with the unaided ear; others must be heard by auscultation using a stethoscope. The bell side of the stethoscope is used to listen to low-pitched sounds such as heart murmurs and BP (although the diaphragm can also be used for BP).

Pressing too hard on the skin can obliterate sounds. The diaphragm side of the stethoscope is used to listen to high-pitched sounds such as normal heart sounds, bowel sounds, and friction rubs. Avoid holding either side of the stethoscope with the thumb to avoid hearing your own pulse.

Auscultation usually follows inspection, palpation, and percussion (when percussion is performed). The one exception is during examination of the abdomen, which should be assessed in this order: inspection, auscultation, percussion, then palpation as percussion and palpation can affect findings on auscultation.

Besides measuring BP, auscultation can be used to listen for breath sounds, heart sounds, bowel sounds, and abnormal sounds in the blood vessels called bruits. Bruits are abnormal blowing or swishing sounds heard on auscultation as blood travels through narrowed or obstructed arteries such as the aorta or renal, iliac, or femoral arteries. Bruits with both systolic and diastolic components suggest the turbulent blood flow of partial arterial occlusion possible with aneurysm or vessel constriction. All large arteries in the neck, abdomen, and limbs can be examined for bruits.

A medical assessment (e.g., physician, nurse, physician assistant) may routinely include auscultation of the temporal and carotid arteries and jugular vein in the head and neck, as well as vascular sounds in the abdomen (e.g., aorta, iliac, femoral, and renal arteries). The therapist is more likely to assess for bruits when the client’s history (e.g., age over 65, history of coronary artery disease), clinical presentation (e.g., neck, back, abdominal, or flank pain), and associated signs and symptoms (e.g., syncopal episodes, signs and symptoms of peripheral vascular disease) warrant additional physical assessment.

The results from inspection, percussion (when appropriate), and palpation should always be correlated with the client’s history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and any associated signs and symptoms before making the decision regarding medical referral.

Integumentary Screening Examination

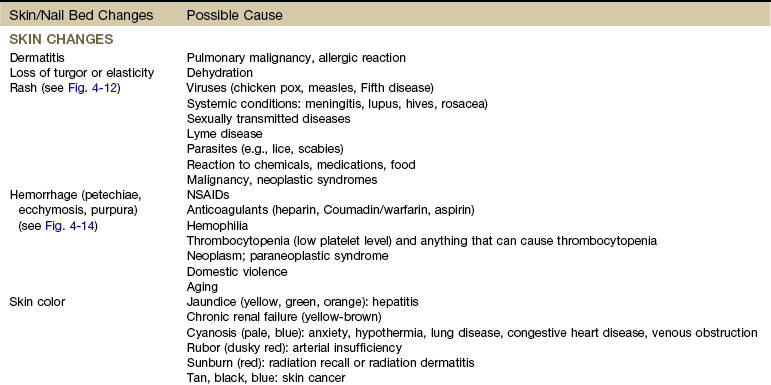

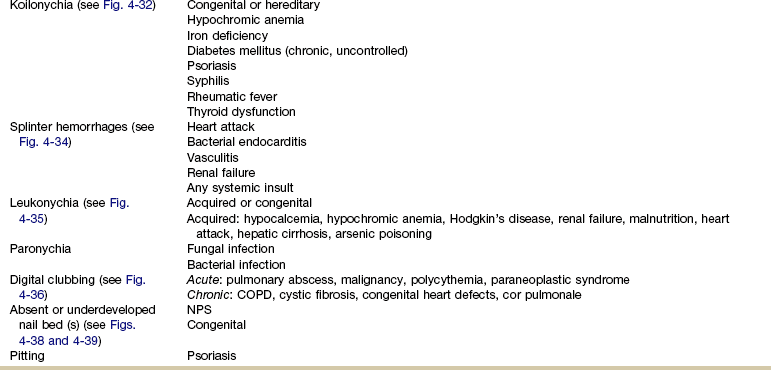

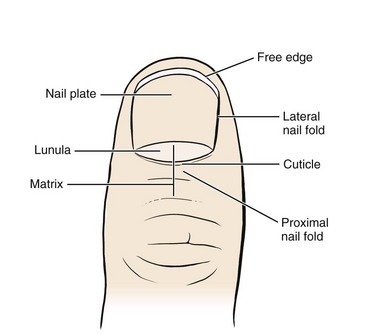

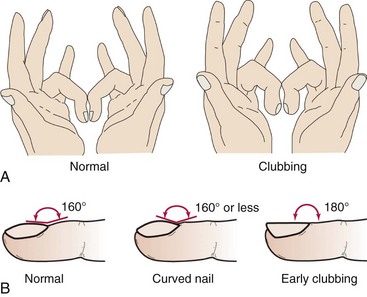

When screening for systemic disease, the therapist must increase attention to what is observable on the outside, primarily the skin and nail beds. Changes in the skin and nail beds may be the first sign of inflammatory, infectious, and immunologic disorders and can occur with involvement of a variety of organs.

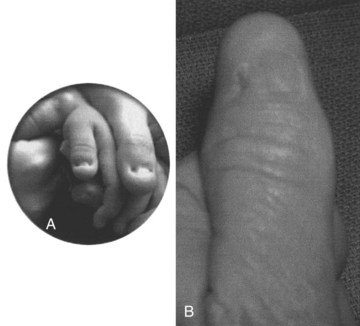

For example, dermatitis can occur 6 to 8 weeks before primary signs and symptoms of pulmonary malignancy develop. Clubbing of the fingers can occur quickly in various acute illnesses and conditions. Skin, hair, and nail bed changes are common with endocrine disorders. Renal disease, rheumatic disorders, and autoimmune diseases are all accompanied by skin and nail bed changes in many physical therapy clients.

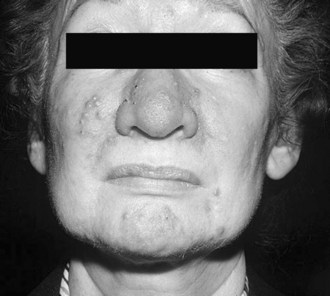

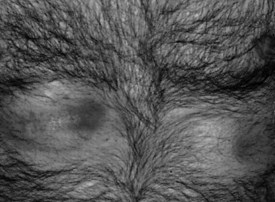

When assessing skin conditions of any kind, even benign lesions such as psoriasis (Fig. 4-2) or eczema, the therapist always should use standard precautions because any disruption of the skin increases the risk of infection. Chronic skin conditions of this type may have new, more effective treatment available. In such cases, the therapist may be able to guide the uninformed client to obtain updated medical treatment.

Fig. 4-2 Psoriasis. A common chronic skin disorder characterized by red patches covered by thick, dry silvery scales that are the result of excessive buildup of epithelial cells. Lesions often come and go and can be anywhere on the body but are most common on extensor surfaces, bony prominences, scalp, ears, and genitals. Arthritis of the small joints of the hands often accompanies the skin disease (psoriatic arthritis). (From Lookingbill DP, Marks JG: Principles of dermatology, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2000, WB Saunders.)

Consider all findings in relation to the client’s age, ethnicity, occupation, and general health. The presence of skin lesions may point to a problem with the integumentary system or may be an integumentary response to a systemic problem.

For example, pruritus is the most common manifestation of dermatologic disease but is also a symptom of underlying systemic disease in up to 50% of individuals with generalized itching.67 In both situations, skin rash is a common accompanying sign. The most common visceral system causing pruritus is the hepatic system. Look for other associated signs and symptoms of liver or gallbladder impairment such as liver flap (asterixis), carpal tunnel syndrome, liver palms (palmar erythema), and spider angiomas (see Fig. 9-3).

At the same time, be aware that pruritus, or itch, is very common among aging adults. The natural attrition of glands that moisturize the skin combined with the effects of sun exposure, medications, excessive bathing, and harsh soaps can result in dry, irritable skin.68

Some clients may describe formication, also referred to as a tactile hallucination, the sensation of ants crawling on the skin, sometimes described as an itching, prickling, or crawling feeling. The most common cause is menopause, but chronic drug or alcohol use can also cause formication. Some schizophrenics also experience formication. As one of the many side effects of crystal methamphetamine addiction, formication is also referred to as speed bumps, meth sores, and crank bugs.

The therapist may see scratch marks or even broken skin where the sufferer has scratched violently. Open, red (often bleeding) sores appear most commonly on the face and arms but can be anywhere on the body. These lesions can become inflamed, swollen, and pus-filled in the presence of a Staphylococcus infection. Left untreated, pathogens can enter the bloodstream, causing dangerous sepsis or deeper abscess. There is no cure, but medical evaluation is needed; topical treatment and cryotherapy can help, and antibiotic treatment is needed when there is infection.

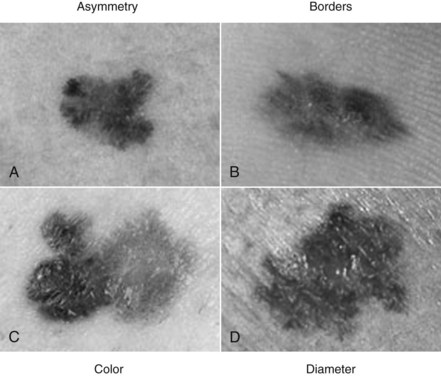

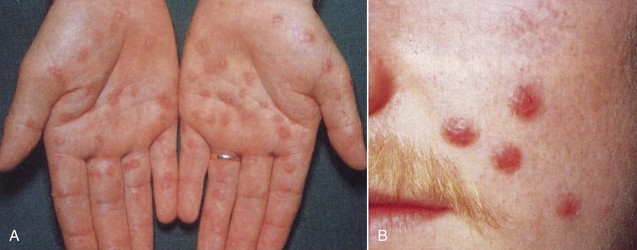

New onset of skin lesions, especially in children, should be medically evaluated (Fig. 4-3). Many conditions in adults and children can be treated effectively; some, but not all, can be cured.

Fig. 4-3 Tinea corporis or ringworm of the body presents anywhere on the body in adult or children but more commonly on the chest, abdomen, back of arms, face, and dorsum of the feet. The circular lesions with clear centers can form singly or in clusters and represent a fungal infection that is both contagious and treatable. Tinea pedis (not shown), also known as ringworm of the feet or “athlete’s foot” occurs most often between the toes, but also along the sides of the feet and the soles (easily spread and treatable). (From Hurwitz S: Clinical pediatric dermatology: a textbook of skin disorders of childhood and adolescence, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1993, WB Saunders.)

Skin Assessment

With the possible exception of a dermatologist, the therapist sees more skin than anyone else in the health care system. Clients are more likely to point out skin lesions or ask the therapist about lumps and bumps. It is important to have a working knowledge of benign versus pathologic skin lesions and know when to refer appropriately.

The hands, arms, feet, and legs can be assessed throughout the physical therapy examination for changes in texture, color, temperature, clubbing, circulation including capillary filling, and edema (Box 4-11). Abnormal texture changes include shiny, stiff, coarse, dry, or scaly skin.

Skin mobility and turgor are affected by the fluid status of the client. Dehydration and aging reduce skin turgor (Fig. 4-4), and edema decreases skin mobility. The therapist should be aware of medications that cause skin to become sensitive to sunlight. The most commonly prescribed medications linked with photosensitivity are listed in Box 4-12.

Fig. 4-4 To check skin turgor (elasticity or resiliency), gently pinch the skin between your thumb and forefinger, lifting it up slightly, then release. Skin turgor can be tested on the forehead or sternum, beneath the clavicle (A), and over the extensor surface of the arm (B) or hand. Expect to see the skin lift up easily and return to place quickly. The test is positive for decreased turgor (often caused by dehydration) when the pinched skin remains lifted 5 or more seconds after release and returns to normal very slowly. (A from Seidel HM: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 7, St. Louis, 2011, Mosby. B from Potter P, Perry A: Basic nursing: essentials for practice, ed 6, St. Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

Chronically ill or hospitalized patients should be examined frequently for signs of skin breakdown. Check all pressure points, including the ears, sacrum, scapulae, shoulders, area over the greater trochanters, heels, malleoli, and the back of the head. Document staging of any pressure ulcers (Table 4-7).

TABLE 4-7

Staging of Pressure Ulcers*

| Pressure ulcers have been defined by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) in conjunction with the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) as localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure or pressure in combination with shear. |

| Stage | Description |

| Stage I | Skin changes observable (increased or decreased temperature, tissue consistency), sensation (pain, itching). |

| Stage II | Epidermis and dermis layers are damaged (partial-thickness); ulcer is superficial and presents as an abrasion, blister, or shallow crater. |

| Stage III | Damage through to subcutaneous tissue (full-thickness skin loss); does not extend through fascia; appears as a deep crater; this is a “never event” (i.e., should never happen). |

| Stage IV | Involvement of muscle, bone, tendon, joint capsule or other supporting structures (full-thickness tissue loss); this is also a “never event” (i.e., should never happen). |

*Staging does not indicate the process of wound healing. The NPUAP also provides the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH Tool) as a quick, reliable tool to monitor the change in pressure ulcer status over time. Updated staging system available on-line at: http://www.npuap.org/push3-0.html.

From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Pressure ulcers in adults: prediction and prevention. Clinical practice guideline no. 3. AHCPR publication no. 92-0047, Rockville, Maryland, 1992, DHHS; European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guidelines. Washington, DC, 2009, NPUAP.

The staging system developed by National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) is an anatomic description of tissue destruction or wound depth designed for use only with pressure ulcers or wounds created by pressure. While it is essential to have this information, it is also very important to document other wound characteristics, such as size, drainage, and granulation tissue, to make the wound assessment complete.

Coordinate with nursing staff to remove prostheses, restraints, and dressings to look beneath them. Anyone with an IV line, catheter, or other insertion sites must be examined for signs of infiltration (e.g., pus, erythema), phlebitis, and tape burns.

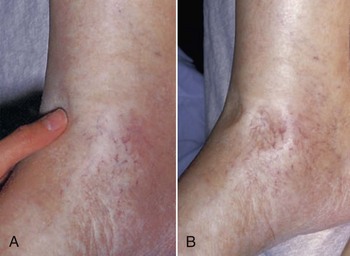

Observe for signs of edema. Edema is an accumulation of fluid in the interstitial spaces. Pitting edema in which pressing a finger into the skin leaves an indentation often indicates a chronic condition (e.g., chronic kidney failure, liver failure, CHF) but can occur acutely as well (e.g., face) (Fig. 4-5). The location of edema helps identify the potential cause. Bilateral edema of the legs may be seen in clients with heart failure or with chronic venous insufficiency.

Fig. 4-5 Pitting edema in a patient with cardiac failure. A depression (“pit”) remains in the edema for some minutes after firm fingertip pressure is applied. (From Forbes CD, Jackson WD. Color atlas and text of clinical medicine, ed 3, London, 2003, Mosby.)

Abdominal and leg edema can be seen in clients with heart disease, cirrhosis of the liver (or other liver impairment), and protein malnutrition. Edema may also be noted in dependent areas, such as the sacrum, when a person is confined to bed. Localized edema in one extremity may be the result of venous obstruction (thrombosis) or lymphatic blockage of the extremity (lymphedema).

Change in Skin Temperature

Skin temperature can be an indication of vascular supply. A handheld, noninvasive, infrared thermometer can be used to measure skin surface temperature. The most common use of this device is for temperature observation and comparison of both feet in individuals with diabetes for the purpose of identifying increased skin temperatures, intended as an early warning of inflammation, impending infection, and possible foot ulceration. Temperature differences of four or more degrees between the right and left foot is a predictive risk factor for foot ulcers; self-monitoring has been shown to reduce the risk of ulceration in high-risk individuals.69-72

Other signs and symptoms of vascular changes of an affected extremity may include paresthesia, muscle fatigue and discomfort, or cyanosis with numbness, pain, and loss of hair from a reduced blood supply (Box 4-13).

Change in Skin Color

Capillary filling of the fingers and toes is an indicator of peripheral circulation. Perform a capillary refill test by pressing down on the nail bed and releasing. Observe first for blanching (whitening) followed by return of color within 3 seconds after release of pressure (normal response).

Skin color changes can occur with a variety of illnesses and systemic conditions. Clients may notice a change in their skin color before anyone else does, so be sure and ask about it. Look for pallor; increased or decreased pigmentation; yellow, green, or red skin color; and cyanosis.

Color changes are often observed first in the fingernails, lips, mucous membranes, conjunctiva of the eye, and palms and soles of dark-skinned people.

Skin changes associated with impairment of the hepatic system include jaundice, pallor, and orange or green skin.

In some situations, jaundice may be the first and only manifestation of disease. It is first noticeable in the sclera of the eye as a yellow hue when bilirubin level reaches 2 to 3 mg/dL. Dark-skinned persons may have a normal yellow color to the outer sclera. Jaundice involves the whole sclera up to the iris.

When the bilirubin level reaches 5 to 6 mg/dL, the skin becomes yellow. Other skin and nail bed changes associated with liver disease include palmar erythema (see Fig. 9-5), spider angiomas (see Figs. 9-3 and 9-4), and nails of Terry (see Fig. 9-6; see further discussion in Chapter 9).

A bluish cast to skin color can occur with cyanosis when oxygen levels are reduced in the arterial blood (central cyanosis) or when blood is oxygenated normally but blood flow is decreased and slow (peripheral cyanosis). Cyanosis is first observed in the hands and feet, lips, and nose as a pale blue change in color. The client may report numbness or tingling in these areas.

Central cyanosis is caused by advanced lung disease, congestive heart disease, and abnormal hemoglobin. Peripheral cyanosis occurs with CHF (decreased blood flow), venous obstruction, anxiety, and cold environment.

Rubor (dusky redness) is a common finding in peripheral vascular disease as a result of arterial insufficiency. When the legs are raised above the level of the heart, pallor of the feet and lower legs develops quickly (usually within 1 minute). When the same client sits up and dangles the feet down, the skin returns to a pink color quickly (usually in about 10 to 15 seconds). A minute later the pallor is replaced by rubor, usually accompanied by pain and diminished pulses. Skin is cool to the touch and trophic changes may be seen (e.g., hair loss over the foot and toes, thick nails, thin skin).

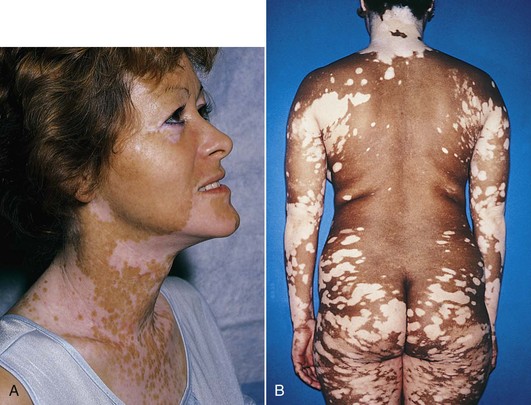

Diffuse hyperpigmentation can occur with Addison’s disease, sarcoidosis, pregnancy, leukemia, hemochromatosis, celiac sprue (malabsorption syndrome), scleroderma, and chronic renal failure.

This presents as patchy tan to brown spots most often but may occur as yellow-brown or yellow to tan with scleroderma and renal failure. Any area of the body can be affected, although pigmentation changes in pregnancy tend to affect just the face (melasma or the mask of pregnancy).

Assessing Dark Skin