Pain Types and Viscerogenic Pain Patterns

Pain is often the primary symptom in many physical therapy practices. Pain assessment is a key feature in the physical therapy interview. Pain is now recognized as the “fifth vital sign,”1 along with blood pressure, temperature, pulse, and respiration.

Recognizing pain patterns that are characteristic of systemic disease is a necessary step in the screening process. Understanding how and when diseased organs can refer pain to the neuromusculoskeletal (NMS) system helps the therapist identify suspicious pain patterns.

This chapter includes a detailed overview of pain patterns that can be used as a foundation for all the organ systems presented. Information will include a discussion of pain types in general and viscerogenic pain patterns specifically. Additional resources for understanding the mechanisms of pain are available.2

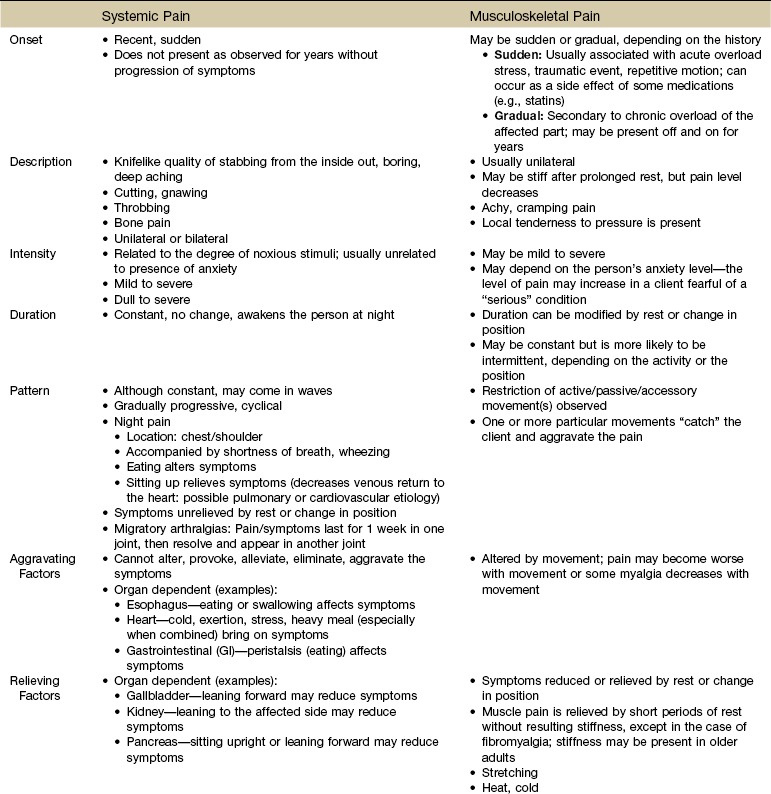

Each section discusses specific pain patterns characteristic of disease entities that can mimic pain from musculoskeletal or neuromuscular disorders. In the clinical decision-making process the therapist will evaluate information regarding the location, referral pattern, description, frequency, intensity, and duration of systemic pain in combination with knowledge of associated symptoms and relieving and aggravating factors.

This information is then compared with presenting features of primary musculoskeletal disorders that have similar patterns of presentation. Pain patterns of the chest, back, shoulder, scapula, pelvis, hip, groin, and sacroiliac (SI) joint are the most common sites of referred pain from a systemic disease process. These patterns are discussed in greater detail later in this text (see Chapters 14 to 18).

A large component in the screening process is being able to recognize the client demonstrating a significant emotional overlay. Pain patterns from cancer can be very similar to what we have traditionally identified as psychogenic or emotional sources of pain. It is important to know how to differentiate between these two sources of painful symptoms. To help identify psychogenic sources of pain, discussions of conversion symptoms, symptom magnification, and illness behavior are also included in this chapter.

Mechanisms of Referred Visceral Pain

The neurology of visceral pain is not well understood at this time. Proposed models are based on what is known about the somatic (nonvisceral) sensory system. Scientists have not found actual nerve fibers and specific nociceptors in organs. Peripheral mechanisms are suspected.3 We do know the afferent supply to internal organs is in close proximity to blood vessels along a path similar to the sympathetic nervous system.4,5

Research is ongoing to identify the sites and mechanisms of visceral nociception. During inflammation, increased nociceptive input from an inflamed organ can sensitize neurons that receive convergent input from an unaffected organ, but the site of visceral cross-sensitivity is unknown.6

Viscerosensory fibers ascend the anterolateral system to the thalamus with fibers projecting to several regions of the brain. These regions encode the site of origin of visceral pain, although they do it poorly because of low receptor density, large overlapping receptive fields, and extensive convergence in the ascending pathway. Thus the cortex cannot distinguish where the pain messages originate from.7,8

Studies show there may be multiple mechanisms operating at different sites to produce the sensation we refer to as “pain.” The same symptom can be produced by different mechanisms and a single mechanism may cause different symptoms.9

In the case of referred pain patterns of viscera, there are three separate phenomena to consider from a traditional Western medicine approach. These are:

Embryologic Development

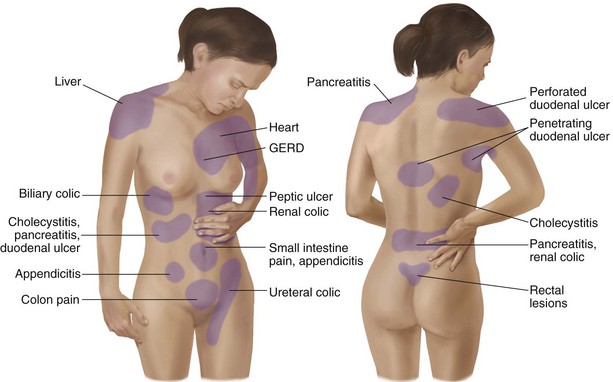

Each system has a bit of its own uniqueness in how pain is referred. For example, the viscera in the abdomen comprise a large percentage of all the organs we have to consider. When a person gives a history of abdominal pain, the location of the pain may not be directly over the involved organ (Fig. 3-1).

Fig. 3-1 Common sites of referred pain from the abdominal viscera. When a client gives a history of referred pain from the viscera, the pain’s location may not be directly over the impaired organ. Visceral embryologic development is the mechanism of the referred pain pattern. Pain is referred to the site where the organ was located in fetal development. (From Jarvis C: Physical examination and health assessment, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2008, WB Saunders.)

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and other neuroimaging methods have shown activation of the inferolateral postcentral gyrus by visceral pain so the brain has a role in visceral pain patterns.10,11 However, it is likely that embryologic development has the primary role in referred pain patterns for the viscera.

Pain is referred to a site where the organ was located in fetal development. Although the organ migrates during fetal development, its nerves persist in referring sensations from the former location.

Organs, such as the kidneys, liver, and intestines, begin forming by 3 weeks when the fetus is still less than the size of a raisin. By day 19, the notochord forming the spinal column has closed and by day 21, the heart begins to beat.

Embryologically, the chest is part of the gut. In other words, they are formed from the same tissue in utero. This explains symptoms of intrathoracic organ pathology frequently being referred to the abdomen as a viscero-viscero reflex. For example, it is not unusual for disorders of thoracic viscera, such as pneumonia or pleuritis, to refer pain that is perceived in the abdomen instead of the chest.4

Although the heart muscle starts out embryologically as a cranial structure, the pericardium around the heart is formed from gut tissue. This explains why myocardial infarction or pericarditis can also refer pain to the abdomen.4

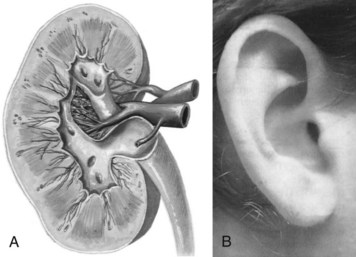

Another example of how embryologic development impacts the viscera and the soma, consider the ear and the kidney. These two structures have the same shape since they come from the same embryologic tissue (otorenal axis of the mesenchyme) and are formed at the same time (Fig. 3-2).

Fig. 3-2 The ear and the kidney have the same shape since they are formed at the same time and from the same embryologic tissue (otorenal axis of the mesenchyme). This is just one example of how fetal development influences form and function. When a child is born with a deformed or missing ear, the medical staff looks for a similarly deformed or missing kidney on the same side. (From Anderson KN: Mosby’s medical, nursing & allied health dictionary, ed 5, St. Louis, 1988, Mosby; A-39; and from Seidel HM, Ball JW, Dains JE, et al: Mosby’s physical examination handbook, St. Louis, 2003, Mosby.)

When a child is born with any anomaly of the ear(s) or even a missing ear, the medical staff knows to look for possible similar changes or absence of the kidney on the same side.

A thorough understanding of fetal embryology is not really necessary in order to recognize red flag signs and symptoms of visceral origin. Knowing that it is one of several mechanisms by which the visceral referred pain patterns occur is a helpful start.

However, the more you know about embryologic development of the viscera, the faster you will recognize somatic pain patterns caused by visceral dysfunction. Likewise, the more you know about anatomy, the origins of anatomy, its innervations, and the underlying neurophysiology, the better able you will be to identify the potential structures involved.

This will lead you more quickly to specific screening questions to ask. The manual therapist will especially benefit from a keen understanding of embryologic tissue derivations. An appreciation of embryology will help the therapist localize the problem vertically.

Multisegmental Innervation

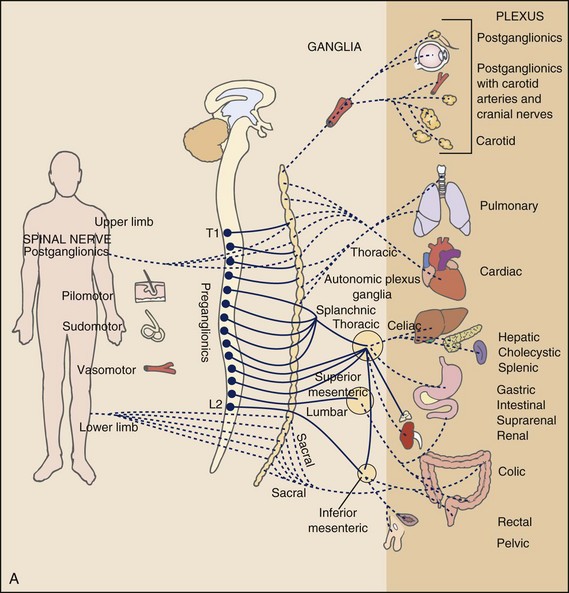

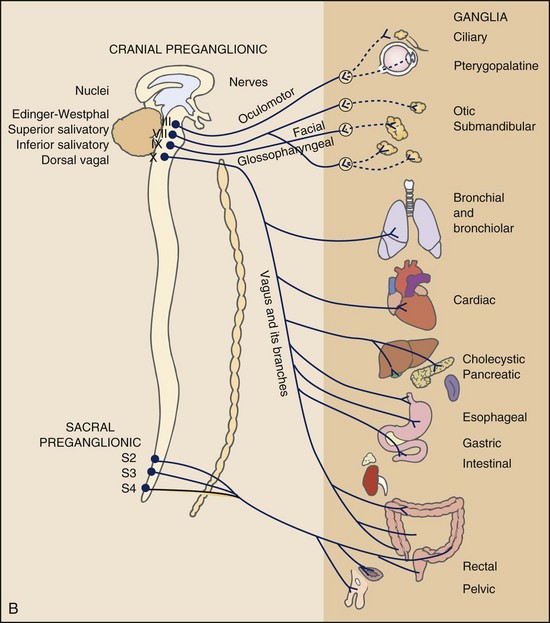

Multisegmental innervation is the second mechanism used to explain pain patterns of a viscerogenic source (Fig. 3-3). The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is part of the peripheral nervous system. As shown in this diagram, the viscera have multisegmental innervations. The multiple levels of innervation of the heart, bronchi, stomach, kidneys, intestines, and bladder are demonstrated clearly.

Fig. 3-3 Sympathetic (A) and parasympathetic (B) divisions of the autonomic nervous system. The visceral afferent fibers mediating pain travel with the sympathetic nerves, except for those from the pelvic organs, which follow the parasympathetics of the pelvic nerve. Major visceral organs have multisegmental innervations overlapping innervations of somatic structures. Visceral pain can be referred to the corresponding somatic area because sensory fibers for the viscera and somatic structures enter the spinal cord at the same levels converging on the same neurons. (From Levy MN, Koeppen BM: Berne and Levy principles of physiology, ed 4, St. Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

There is new evidence to support referred visceral pain to somatic tissues based on overlapping or same segmental projections of spinal afferent neurons to the spinal dorsal horn. This concept is referred to as visceral-organ cross-sensitization. The mechanism is likely to be sensitization of viscera-somatic convergent neurons.12

For the first time ever, scientists showed that individuals diagnosed with multiple visceral problems obtained relief from pain in all organ systems with overlapping segmental projections when only one visceral area was treated. In other words, nontreated visceral disease significantly decreased when one viscera of the overlapping segments was addressed. For groups of people with no overlapping segments, spontaneous relief of referred pain was not obtained until and unless all involved visceral systems were treated.12

Pain of a visceral origin can be referred to the corresponding somatic areas. The example of cardiac pain is a good one. Cardiac pain is not felt in the heart, but is referred to areas supplied by the corresponding spinal nerves.

Instead of actual physical heart pain, cardiac pain can occur in any structure innervated by C3 to T4 such as the jaw, neck, upper trapezius, shoulder, and arm. Pain of cardiac and diaphragmatic origin is often experienced in the shoulder, in particular, because the C5 spinal segment supplies the heart, respiratory diaphragm, and shoulder.

Direct Pressure and Shared Pathways

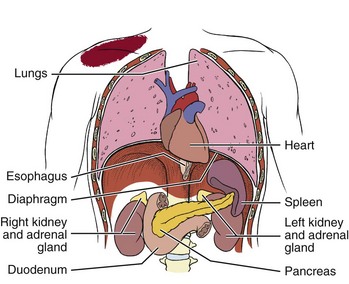

A third and final mechanism by which the viscera refer pain to the soma is the concept of direct pressure and shared pathways (Fig. 3-4). As shown in this illustration, many of the viscera are near the respiratory diaphragm. Any pathologic process that can inflame, infect, or obstruct the organs can bring them in contact with the respiratory diaphragm.

Fig. 3-4 Direct pressure from any inflamed, infected, or obstructed organ in contact with the respiratory diaphragm can refer pain to the ipsilateral shoulder. Note the location of each of the viscera. The spleen is tucked up under the diaphragm on the left side so any impairment of the spleen can cause left shoulder pain. The tail of the pancreas can come in contact with the diaphragm on the left side potentially causing referred pain to the left shoulder. The head of the pancreas can impinge the right side of the diaphragm causing referred pain to the right side. The gallbladder (not shown) is located up under the liver on the right side with corresponding right referred shoulder pain possible. Other organs that can come in contact with the diaphragm in this way include the heart and the kidneys.

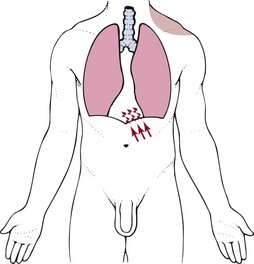

Anything that impinges the central diaphragm can refer pain to the shoulder and anything that impinges the peripheral diaphragm can refer pain to the ipsilateral costal margins and/or lumbar region (Fig. 3-5).

Fig. 3-5 Irritation of the peritoneal (outside) or pleural (inside) surface of the central area of the respiratory diaphragm can refer sharp pain to the upper trapezius muscle, neck, and supraclavicular fossa. The pain pattern is ipsilateral to the area of irritation. Irritation of the peripheral portion of the diaphragm can refer sharp pain to the costal margins and lumbar region (not shown).

This mechanism of referred pain through shared pathways occurs as a result of ganglions from each neural system gathering and sharing information through the cord to the plexuses. The visceral organs are innervated through the ANS. The ganglions bring in information from around the body. The nerve plexuses decide how to respond to this information (what to do) and give the body finely-tuned, local control over responses.

Plexuses originate in the neck, thorax, diaphragm, and abdomen, terminating in the pelvis. The brachial plexus supplies the upper neck and shoulder while the phrenic nerve innervates the respiratory diaphragm. More distally, the celiac plexus supplies the stomach and intestines. The neurologic supply of the plexuses is from parasympathetic fibers from the vagus and pelvic splanchnic nerves.4

The plexuses work independently of each other but not independently of the ganglia. The ganglia collect information derived from both the parasympathetic and the sympathetic fibers. The ganglia deliver this information to the plexuses; it is the plexuses that provide fine, local control in each of the organ systems.4

For example, the lower portion of the heart is in contact with the center of the diaphragm. The spleen on the left side of the body is tucked up under the dome of the diaphragm. The kidneys (on either side) and the pancreas in the center are in easy reach of some portion of the diaphragm.

The body of the pancreas is in the center of the human body. The tail rests on the left side of the body. If an infection, inflammation, or tumor or other obstruction distends the pancreas, it can put pressure on the central part of the diaphragm.

Since the phrenic nerve (C3-5) innervates the central zone of the diaphragm, as well as part of the pericardium, the gallbladder, and the pancreas, the client with impairment of these viscera can present with signs and symptoms in any of the somatic areas supplied by C3-5 (e.g., shoulder).

In other words, the person can experience symptoms in the areas innervated by the same nerve pathways. So a problem affecting the pancreas can look like a heart problem, a gallbladder problem, or a mid-back/scapular or shoulder problem.

Most often, clients with pancreatic disease present with the primary pain pattern associated with the pancreas (i.e., left epigastric pain or pain just below the xiphoid process). The somatic presentation of referred pancreatic pain to the shoulder or back is uncommon, but it is the unexpected, referred pain patterns that we see in a physical or occupational therapy practice.

Another example of this same phenomenon occurs with peritonitis or gallbladder inflammation. These conditions can irritate the phrenic endings in the central part of the diaphragmatic peritoneum. The client can experience referred shoulder pain due to the root origin shared in common by the phrenic and supraclavicular nerves.

Not only is it true that any structure that touches the diaphragm can refer pain to the shoulder, but even structures adjacent to or in contact with the diaphragm in utero can do the same. Keep in mind there has to be some impairment of that structure (e.g., obstruction, distention, inflammation) for this to occur (Case Example 3-1).

Assessment of Pain and Symptoms

The interviewing techniques and specific questions for pain assessment are outlined in this section. The information gathered during the interview and examination provides a description of the client that is clear, accurate, and comprehensive. The therapist should keep in mind cultural rules and differences in pain perception, intensity, and responses to pain found among various ethnic groups.13

Measuring pain and assessing pain are two separate issues. A measurement assigns a number or value to give dimension to pain intensity.14 A comprehensive pain assessment includes a detailed health history, physical exam, medication history (including nonprescription drug use and complementary and alternative therapies), assessment of functional status, and consideration of psychosocial-spiritual factors.15

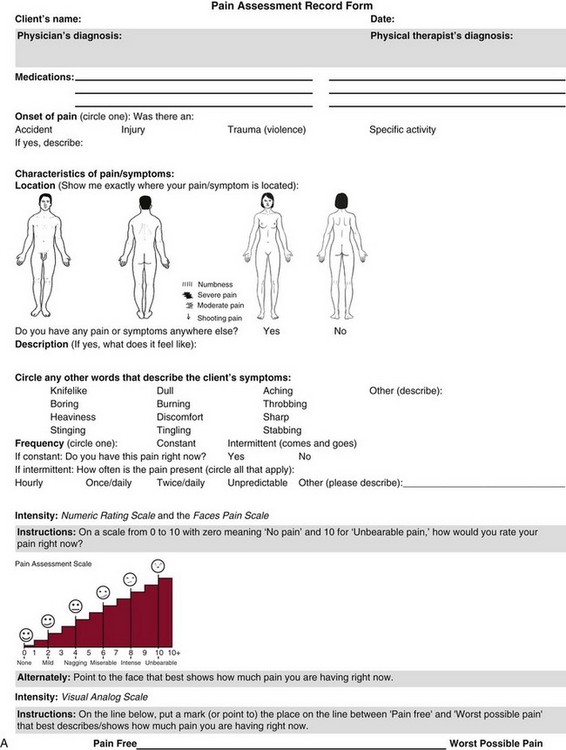

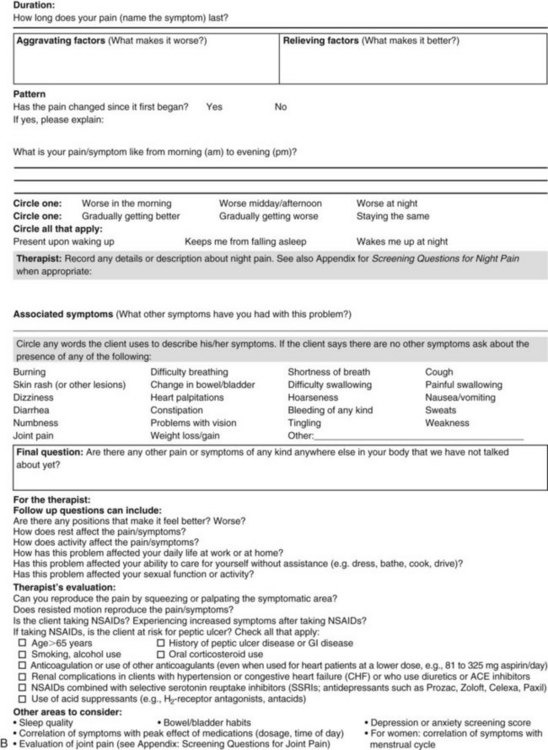

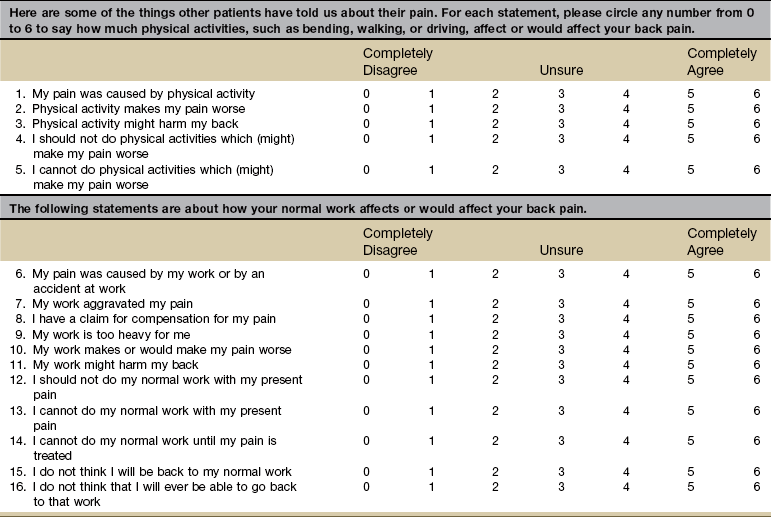

The portion of the core interview regarding a client’s perception of pain is a critical factor in the evaluation of signs and symptoms. Questions about pain must be understood by the client and should be presented in a nonjudgmental manner. A record form may be helpful to standardize pain assessment with each client (Fig. 3-6).

Fig. 3-6 Pain Assessment Record Form. Use this form to complete the pain history and obtain a description of the pain pattern. The form is printed in the Appendix for your use. This form may be copied and used without permission. (From Carlsson AM: Assessment of chronic pain. I. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale, Pain 16(1):87–101, 1983. Used with permission.)

To elicit a complete description of symptoms from the client, the physical therapist may wish to use a term other than pain. For example, referring to the client’s symptoms or using descriptors such as hurt or sore may be more helpful with some individuals. Burning, tightness, heaviness, discomfort, and aching are just a few examples of other possible word choices. The use of alternative words to describe a client’s symptoms may also aid in refocusing attention away from pain and toward improvement of functional abilities.

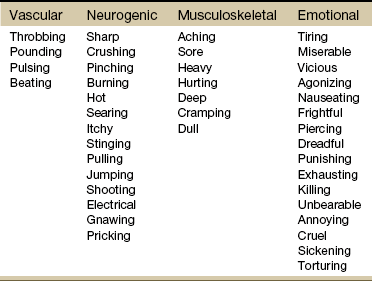

If the client has completed the McGill Pain Questionnaire (see discussion of McGill Pain Questionnaire in this chapter),16 the physical therapist may choose the most appropriate alternative word selected by the client from the list to refer to the symptoms (Table 3-1).

TABLE 3-1

From Melzack R: The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods, Pain 1:277, 1975.

Pain Assessment in the Older Adult

Pain is an accepted part of the aging process, but we must be careful to take the reports of pain from older persons as serious and very real and not discount the symptoms as part of aging. Well over half of the older adults in the United States report chronic joint symptoms.17 We are likely to see pain more often as a key feature among older adults as our population continues to age.

The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) reports the use of over-the-counter (OTC) analgesic medications for pain, aching, and discomfort is common in older adults along with routine use of prescription drugs. Many older adults have taken these medications for 6 months or more.18

Older adults may avoid giving an accurate assessment of their pain. Some may expect pain with aging or fear that talking about pain will lead to expensive tests or medications with unwanted side effects. Fear of losing one’s independence may lead others to underreport pain symptoms.19

Sensory and cognitive impairment in older, frail adults makes communication and pain assessment more difficult.18 The client may still be able to report pain levels reliably using the visual analogue scales in the early stages of dementia. Improving an older adult’s ability to report pain may be as simple as making sure the client has his or her glasses and hearing aid.

The Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS) (Box 3-1) may be the most sensitive and reliable among older adults, including those with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment.20 But these and other pain scales rely on the client’s ability to understand the scale and communicate a response. As dementia progresses, these abilities are lost as well.

A client with Alzheimer’s-type dementia loses short-term memory and cannot always identify the source of recent painful stimuli.21,22 The Alzheimer’s Discomfort Rating Scale may be more helpful for older adults who are unable to communicate their pain.23 The therapist records the frequency, intensity, and duration of the client’s discomfort based on the presence of noisy breathing, facial expressions, and overall body language.

Another tool under investigation is the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. The PAINAD scale is a simple, valid, and reliable instrument for measurement of pain in noncommunicative clients developed by the same author as the Alzheimer’s Discomfort Rating Scale.24 A disadvantage of this pain scale is that the pain is inferred by the examiner or caregiver rather than self-reported directly by the individual experiencing the pain.25

Facial grimacing; nonverbal vocalization such as moans, sighs, or gasps; and verbal comments (e.g., ouch, stop) are the most frequent behaviors among cognitively impaired older adults during painful movement (Box 3-2). Bracing, holding onto furniture, or clutching the painful area are other behavioral indicators of pain. Alternately, the client may resist care by others or stay very still to guard against pain caused by movement.26

Untreated pain in an older adult with advanced dementia can lead to secondary problems such as sleep disturbances, weight loss, dehydration, and depression. Pain may be manifested as agitation and increased confusion.21

Older adults are more likely than younger adults to have what is referred to as atypical acute pain. For example, silent acute myocardial infarction (MI) occurs more often in the older adult than in the middle-aged to early senior adult. Likewise, the older adult is more likely to experience appendicitis without any abdominal or pelvic pain.27

Pain Assessment in the Young Child

Many infants and children are unable to report pain. Even so the therapist should not underestimate or prematurely conclude that a young client is unable to answer any questions about pain. Even some clients (both children and adults) with substantial cognitive impairment may be able to use pain-rating scales when explained carefully.28

The Faces Pain Scale (FACES or FPS) for children (see Fig. 3-6) was first presented in the 1980s.29 It has since been revised (FPS-R)30 and presented concurrently by other researchers with similar assessment measures.31

Most of the pilot work for the FPS was done informally with children from preschool through young school age. Researchers have used the FPS scale with adults, especially the elderly, and have had successful results. Advantages of the cartoon-type FPS scale are that it avoids gender, age, and racial biases.32

Research shows that use of the word “hurt” rather than pain is understood by children as young as 3 years old.33,34 Use of a word such as “owie” or “ouchie” by a child to describe pain is an acceptable substitute.32 Assessing pain intensity with the FPS scale is fast and easy. The child looks at the faces, the therapist or parent uses the simple words to describe the expression, and the corresponding number is used to record the score.

A review of multiple other measures of self-report is also available,14 as well as a review of pain measures used in children by age, including neonates.35

When using a rating scale is not possible, the therapist may have to rely on the parent or caregiver’s report and/or other measures of pain in children with cognitive or communication impairments and physical disabilities. Look for telltale behavior such as lack of cooperation, withdrawal, acting out, distractibility, or seeking comfort. Altered sleep patterns, vocalizations, and eating patterns provide additional clues.

In very young children and infants, the Child Facial Coding System (CFCS) and the Neonatal Facial Coding System (NFCS) can be used as behavioral measures of pain intensity.36,37

Facial actions and movements, such as brow bulge, eye squeeze, mouth position, and chin quiver, are coded and scored as pain responses. This tool has been revised and tested as valid and reliable for use postoperatively in children ages 0 to 18 months following major abdominal or thoracic surgery.38

Vital signs should be documented but not relied upon as the sole determinant of pain (or absence of pain) in infants or young children. The pediatric therapist may want to investigate other pain measures available for neonates and infants.39,40

Characteristics of Pain

It is very important to identify how the client’s description of pain as a symptom relates to sources and types of pain discussed in this chapter. Many characteristics of pain can be elicited from the client during the Core Interview to help define the source or type of pain in question. These characteristics include:

Other additional components are related to factors that aggravate the pain, factors that relieve the pain, and other symptoms that may occur in association with the pain. Specific questions are included in this section for each descriptive component. Keep in mind that an increase in frequency, intensity, or duration of symptoms over time can indicate systemic disease.

Location of Pain

Questions related to the location of pain focus the client’s description as precisely as possible. An opening statement might be as follows:

If the client points to a small, localized area and the pain does not spread, the cause is likely to be a superficial lesion and is probably not severe. If the client points to a small, localized area but the pain does spread, this is more likely to be a diffuse, segmental, referred pain that may originate in the viscera or deep somatic structure.

The character and location of pain can change and the client may have several pains at once, so repeated pain assessment may be needed.

Description of Pain

To assist the physical therapist in obtaining a clear description of pain sensation, pose the question:

When a client describes the pain as knifelike, boring, colicky, coming in waves, or a deep aching feeling, this description should be a signal to the physical therapist to consider the possibility of a systemic origin of symptoms. Dull, somatic pain of an aching nature can be differentiated from the aching pain of a muscular lesion by squeezing or by pressing the muscle overlying the area of pain. Resisting motion of the limb may also reproduce aching of muscular origin that has no connection to deep somatic aching.

Intensity of Pain

The level or intensity of the pain is an extremely important but difficult component to assess in the overall pain profile. Psychologic factors may play a role in the different ratings of pain intensity measured between African Americans and Caucasians. African Americans tend to rate pain as more unpleasant and more intense than whites, possibly indicating a stronger link between emotions and pain behavior for African Americans compared with Caucasians.41

The same difference is observed between women and men.42,43 Likewise, pain intensity is reported as less when the affected individual has some means of social or emotional support.44

Assist the client with this evaluation by providing a rating scale. You may use one or more of these scales, depending on the clinical presentation of each client (see Fig. 3-6). Show the pain scale to your client. Ask the client to choose a number and/or a face that best describes his or her current pain level. You can use this scale to quantify symptoms other than pain such as stiffness, pressure, soreness, discomfort, cramping, aching, numbness, tingling, and so on. Always use the same scale for each follow-up assessment.

The Visual Analog Scale (VAS)45,46 allows the client to choose a point along a 10-cm (100 mm) horizontal line (see Fig. 3-6). The left end represents “No pain” and the right end represents “Pain as bad as it could possibly be” or “Worst Possible Pain.” This same scale can be presented in a vertical orientation for the client who must remain supine and cannot sit up for the assessment. “No pain” is placed at the bottom, and “Worst pain” is put at the top.

The VAS scale is easily combined with the numeric rating scale with possible values ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain). It can be used to assess current pain, worst pain in the preceding 24 hours, least pain in the past 24 hours, or any combination the clinician finds useful.

The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS; see Fig. 3-6) allows the client to rate the pain intensity on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imaginable). This is probably the most commonly used pain rating scale in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. It is a simple and valid method of measuring pain.

Although the scale was tested and standardized using 0 to 10, the plus is used for clients who indicate the pain is “off the scale” or “higher than a 10.” Some health care professionals prefer to describe 10 as “worst pain experienced with this condition” to avoid needing a higher number than 10.

This scale is especially helpful for children or cognitively impaired clients. In general, even adults without cognitive impairments may prefer to use this scale.

An alternative method provides a scale of 1 to 5 with word descriptions for each number16 and asks:

This scale for measuring the intensity of pain can be used to establish a baseline measure of pain for future reference. A client who describes the pain as “excruciating” (or a 5 on the scale) during the initial interview may question the value of therapy when several weeks later there is no subjective report of improvement.

A quick check of intensity by using this scale often reveals a decrease in the number assigned to pain levels. This can be compared with the initial rating, thus providing the client with assurance and encouragement in the rehabilitation process. A quick assessment using this method can be made by asking:

The description of intensity is highly subjective. What might be described as “mild” for one person could be “horrible” for another person. Careful assessment of the person’s nonverbal behavior (e.g., ease of movement, facial grimacing, guarding movements) and correlation of the person’s personality with his or her perception of the pain may help to clarify the description of the intensity of the pain. Pain of an intense, unrelenting (constant) nature is often associated with systemic disease.

The 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey discussed in Chapter 2 includes an assessment of bodily pain along with a general measure of health-related quality of life. Nurses often use the PQRST mnemonic to help identify underlying pathology or pain (Box 3-3).

Frequency and Duration of Pain

The frequency of occurrence is related closely to the pattern of the pain, and the client should be asked how often the symptoms occur and whether the pain is constant or intermittent. Duration of pain is a part of this description.

Further responses may reveal that the pain is perceived as being constant but in fact is not actually present consistently and/or can be reduced with rest or change in position, which are characteristics more common with pain of musculoskeletal origin. Symptoms that truly do not change throughout the course of the day warrant further attention.

Pattern of Pain

After listening to the client describe all the characteristics of his or her pain or symptoms, the therapist may recognize a vascular, neurogenic, musculoskeletal (including spondylogenic), emotional, or visceral pattern (see Table 3-1).

The following sequence of questions may be helpful in further assessing the pattern of pain, especially how the symptoms may change with time.

The pattern of pain associated with systemic disease is often a progressive pattern with a cyclical onset (i.e., the client describes symptoms as being alternately worse, better, and worse over a period of months). When there is back pain, this pattern differs from the sudden sequestration of a discogenic lesion that appears with a pattern of increasingly worse symptoms followed by a sudden cessation of all symptoms. Such involvement of the disk occurs without the cyclical return of symptoms weeks or months later, which is more typical of a systemic disorder.

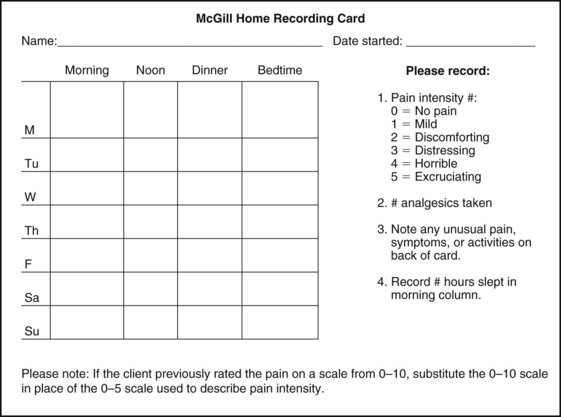

If the client appears to be unsure of the pattern of symptoms or has “avoided paying any attention” to this component of pain description, it may be useful to keep a record at home assisting the client to take note of the symptoms for 24 hours. A chart such as the McGill Home Recording Card16 (Fig. 3-7) may help the client outline the existing pattern of the pain and can be used later in the episode of care to assist the therapist in detecting any change in symptoms or function.

Fig. 3-7 McGill Home Recording Card. When assessing constant pain, have the client complete this form for 24 to 48 hours. Pay attention to the client who describes a loss of sleep but who is not awake enough to record missed or interrupted sleep. This may help the physician in differentiating between a sleep disorder and sleep disturbance. You may want to ask the client to record sexual activity as a measure of function and pain levels. It is not necessary to record details, just when the client perceived him or herself as being sexually active. (From Melzack R: The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods, Pain 1:298, 1975.)

There is also a Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire that has been validated for use to assess treatment response. It is designed to measure all kinds of pain—both neuropathic and nonneuropathic—using a numeric rating scale to assess 22 pain descriptors from zero (none) to 10 (worst possible).47

Medications can alter the pain pattern or characteristics of painful symptoms. Find out how well the client’s current medications reduce, control, or relieve pain. Ask how often medications are needed for breakthrough pain.

When using any of the pain rating scales, record the use of any medications that can alter or reduce pain or symptoms such as antiinflammatories or analgesics. At the same time remember to look for side effects or adverse reactions to any drugs or drug combinations.

Watch for clients taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) who experience an increase in shoulder, neck, or back pain several hours after taking the medication. Normally, one would expect symptom relief from NSAIDs so any increase in symptoms is a red flag for possible peptic ulcer.

A client frequently will comment that the pain or symptoms have not changed despite 2 or 3 weeks of physical therapy intervention. This information can be discouraging to both client and therapist; however, when the symptoms are reviewed, a decrease in pain, increase in function, reduced need for medications, or other significant improvement in the pattern of symptoms may be seen.

The improvement is usually gradual and is best documented through the use of a baseline of pain activity established at an early stage in the episode of care by using a record such as the Home Recording Card (or other pain rating scale).

However, if no improvement in symptoms or function can be demonstrated, the therapist must again consider a systemic origin of symptoms. Repeating screening questions for medical disease is encouraged throughout the episode of care even if such questions were included in the intake interview.

Because of the progressive nature of systemic involvement, the client may not have noticed any constitutional symptoms at the start of the physical therapy intervention that may now be present. Constitutional symptoms (see Box 1-3) affect the whole body and are characteristic of systemic disease or illness.

Aggravating and Relieving Factors

A series of questions addressing aggravating and relieving factors must be included such as:

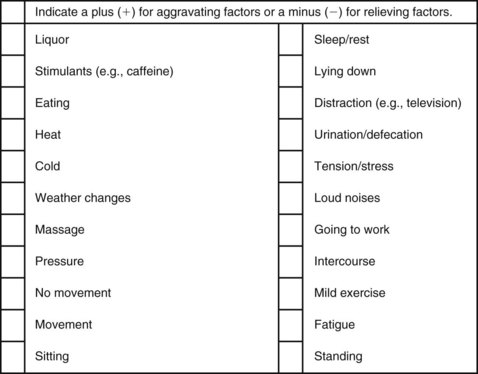

The McGill Pain Questionnaire also provides a chart (Fig. 3-8) that may be useful in determining the presence of relieving or aggravating factors.

Fig. 3-8 Factors aggravating and relieving pain. (From Melzack R: The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods, Pain 1:277, 1975.)

Systemic pain tends to be relieved minimally, relieved only temporarily, or unrelieved by change in position or by rest. However, musculoskeletal pain is often relieved both by a change of position and by rest.

Associated Symptoms

These symptoms may occur alone or in conjunction with the pain of systemic disease. The client may or may not associate these additional symptoms with the chief complaint. The physical therapist may ask:

Whenever the client says “yes” to such associated symptoms, check for the presence of these symptoms bilaterally. Additionally, bilateral weakness, either proximally or distally, should serve as a red flag possibly indicative of more than a musculoskeletal lesion.

Blurred vision, double vision, scotomas (black spots before the eyes), or temporary blindness may indicate early symptoms of multiple sclerosis or may possibly be warning signs of an impending cerebrovascular accident. The presence of any associated symptoms, such as those mentioned here, would require contact with the physician to confirm the physician’s knowledge of these symptoms.

In summary, careful, sensitive, and thorough questioning regarding the multifaceted experience of pain can elicit essential information necessary when making a decision regarding treatment or referral. The use of pain assessment tools such as Fig. 3-6 and Table 3-2 may facilitate clear and accurate descriptions of this critical symptom.

Sources of Pain

Between the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the science of clinical pain assessment and management made a significant paradigm shift from an empiric approach to one that is based on identifying and understanding the actual mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of pain.

The implications of this are immense as we move from classifying pain on the basis of disease, duration, and body part or anatomy to a mechanism-based classification. In this approach the major goal of assessment is to identify the pathophysiologic mechanism of the pain and use this information to plan appropriate intervention.9,48

Physical therapists frequently see clients whose primary complaint is pain, which often leads to a loss of function. However, focusing on sources of pain does not always help us to identify the causes of tissue irritation.

The most effective physical therapy diagnosis will define the syndrome and address the causes of pain rather than just identifying the sources of pain.49 Usually, a careful assessment of pain behavior is invaluable in determining the nature and extent of the underlying pathology.

The clinical evaluation of pain usually involves identification of the primary disease/etiological factor(s) considered responsible for producing or initiating the pain. The client is placed within a broad pain category usually labeled as nociceptive, inflammatory, or neuropathic pain (see Table 3-4). Pain and sensory disturbances associated with central changes (sensitization) may be present with chronic pain.9,50 It can be difficult in clinical practice to specify which of these, alone or in combination, may be present.19

We further classify the pain by identifying the anatomic distribution, quality, and intensity of the pain. Such an approach allows for physical therapy interventions for each identified mechanism involved.

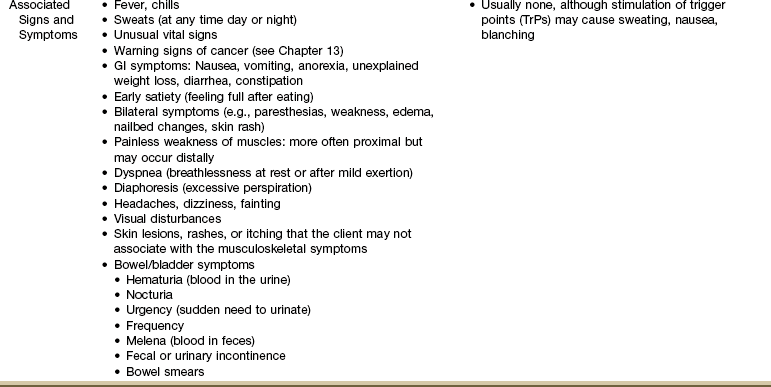

From a screening perspective, we look at the possible sources of pain and types of pain. When listening to the client’s description of pain, consider these possible sources of pain (Table 3-3):

Cutaneous Sources of Pain

Cutaneous pain (related to the skin) includes superficial somatic structures located in the skin and subcutaneous tissue. The pain is well localized as the client can point directly to the area that “hurts.” Pain from a cutaneous source can usually be localized with one finger. Skin pain or tenderness can be associated with referred pain from the viscera or referred from deep somatic structures.

Impairment of any organ can result in sudomotor changes that present as trophic changes such as itching, dysesthesia, skin temperature changes, or dry skin. The difficulty is that biomechanical dysfunction can also result in these same changes, which is why a careful evaluation of soft tissue structures along with a screening exam for systemic disease is required.

Cutaneous pain perception varies from person to person and is not always a reliable indicator of pathologic etiology. These differences in pain perception may be associated with different pain mechanisms. For example, differences in cutaneous pain perception exist based on gender and ethnicity. There may be differences in opioid activity and baroreceptor-regulated pain systems between the sexes to account for these variations.42

Somatic Sources of Pain

Somatic pain can be superficial or deep. Somatic pain is labeled according to its source as deep somatic, somatovisceral, somatoemotional (also referred to as psychosomatic), or viscerosomatic.

Most of what the therapist treats is part of the somatic system whether we call that the neuromuscular system, the musculoskeletal system, or the NMS system. When psychologic disorders present as somatic dysfunction, we refer to these conditions as psychophysiologic disorders.

Psychophysiologic disorders, including somatoform disorders, are discussed in detail elsewhere.51-53

Superficial somatic structures involve the skin, superficial fasciae, tendon sheaths, and periosteum. Deep somatic pain comes from pathologic conditions of the periosteum and cancellous (spongy) bone, nerves, muscles, tendons, ligaments, and blood vessels. Deep somatic structures also include deep fasciae and joint capsules. Somatic referred pain does not involve stimulation of nerve roots. It is produced by stimulation of nerve endings within the superficial and deep somatic structures just mentioned.

Somatic referred pain is usually reported as dull, aching, or gnawing or described as an expanding pressure too diffuse to localize. There are no neurologic signs associated with somatic referred pain since this type of pain is considered nociceptive and is not caused by compression of spinal nerves or nerve root. It is possible to have combinations of pain and neurologic findings when more than one pathway is disturbed.54-56

Deep somatic pain is poorly localized and may be referred to the body surface, becoming cutaneous pain. It can be associated with an autonomic phenomenon, such as sweating, pallor, or changes in pulse and blood pressure, and is commonly accompanied by a subjective feeling of nausea and faintness.

Pain associated with deep somatic lesions follows patterns that relate to the embryologic development of the musculoskeletal system. This explains why such pain may not be perceived directly over the involved organ (see Fig. 3-1).

Parietal pain (related to the wall of the chest or abdominal cavity) is also considered deep somatic. The visceral pleura (the membrane enveloping the organs) is insensitive to pain, but the parietal pleura is well supplied with pain nerve endings. For this reason, it is possible for a client to have extensive visceral disease (e.g., heart, lungs) without pain until the disease progresses enough to involve the parietal pleura.

When we talk about the “psycho-somatic” response, we refer to the mind-body connection.

Somatoemotional or psychosomatic sources of pain occur when emotional or psychologic distress produces physical symptoms either for a relatively brief period or with recurrent and multiple physical manifestations spanning many months or years. The person affected by the latter may be referred to as a somatizer, and the condition is called a somatization disorder.

Two different approaches to somatization have been proposed. One method treats somatization as a phenomenon that is secondary to psychologic distress. This is called presenting somatization. The second defines somatization as a primary event characterized by the presence of medically unexplained symptoms. This model is called functional somatization.57

Alternately, there are viscerosomatic sources of pain when visceral structures affect the somatic musculature, such as the reflex spasm and rigidity of the abdominal muscles in response to the inflammation of acute appendicitis or the pectoral trigger point associated with an acute myocardial infarction. These visible and palpable changes in the tension of skin and subcutaneous and other connective tissues that are segmentally related to visceral pathologic processes are referred to as connective tissue zones or reflex zones.58

Somatovisceral pain occurs when a myalgic condition causes functional disturbance of the underlying viscera, such as the trigger points (TrPs) of the abdominal muscles, causing diarrhea, vomiting, or excessive burping (Case Example 3-2).

Visceral Sources of Pain

Visceral sources of pain include the internal organs and the heart muscle. This source of pain includes all body organs located in the trunk or abdomen, such as those of the respiratory, digestive, urogenital, and endocrine systems, as well as the spleen, the heart, and the great vessels.

Visceral pain is not well localized for two reasons:

1. Innervation of the viscera is multisegmental.

2. There are few nerve receptors in these structures (see Fig. 3-3).

The pain tends to be poorly localized and diffuse.

Visceral pain is well known for its ability to produce referred pain (i.e., pain perceived in an area other than the site of the stimuli). Referred pain occurs because visceral fibers synapse at the level of the spinal cord close to fibers supplying specific somatic structures. In other words, visceral pain corresponds to dermatomes from which the organ receives its innervations, which may be the same innervations for somatic structures.

For example, the heart is innervated by the C3-T4 spinal nerves. Pain of a cardiac source can affect any part of the soma (body) also innervated by these levels. This is one reason why someone having a heart attack can experience jaw, neck, shoulder, mid-back, arm, or chest pain and accounts for the many and varied clinical pictures of MI (see Fig. 6-9).

More specifically, the pericardium (sac around the entire heart) is adjacent to the diaphragm. Pain of cardiac and diaphragmatic origin is often experienced in the shoulder because the C5-6 spinal segment (innervation for the shoulder) also supplies the heart and the diaphragm.

Other examples of organ innervations and their corresponding sensory overlap are as follows4:

• Sensory fibers to the heart and lungs enter the spinal cord from T1-4 (this may extend to T6).

• Sensory fibers to the gallbladder, bile ducts, and stomach enter the spinal cord at the level of the T7-8 dorsal roots (i.e., the greater splanchnic nerve).

• The peritoneal covering of the gallbladder and/or the central zone of the diaphragm are innervated by the phrenic nerve originating from the C3-5 (phrenic nerve) levels of the spinal cord.

• The phrenic nerve (C3-5) also innervates portions of the pericardium.

• Sensory fibers to the duodenum enter the cord at the T9-10 levels.

• Sensory fibers to the appendix enter the cord at the T10 level (i.e., the lesser splanchnic nerve).

• Sensory fibers to the renal/ureter system enter the cord at the L1-2 level (i.e., the splanchnic nerve).

As mentioned earlier, diseases of internal organs can be accompanied by cutaneous hypersensitivity to touch, pressure, and temperature. This viscerocutaneous reflex occurs during the acute phase of the disease and disappears with its recovery.

The skin areas affected are innervated by the same cord segments as for the involved viscera; they are referred to as Head’s zones.58 Anytime a client presents with somatic symptoms also innervated by any of these levels, we must consider the possibility of a visceral origin.

Keep in mind that when it comes to visceral pain, the viscera have few nerve endings. The visceral pleura are insensitive to pain. It is not until the organ capsule (deep somatic structure) is stretched (e.g., by a tumor or inflammation) that pain is perceived and possibly localized. This is why changes can occur within the organs without painful symptoms to warn the person. It is not until the organ is inflamed or distended enough from infection or obstruction to impinge nearby structures or the lining of the chest or abdominal cavity that pain is felt.

The neurology of visceral pain is not well understood. There is not a known central processing system unique to visceral pain. Primary afferent fibers innervating the viscera consist entirely of Aδ and C fibers. Nociceptors of the organs are polymodal, responding to heat, chemical stimuli, and mechanical stimuli (e.g., compression, distention).5,59 It is known that the afferent supply to internal organs follows a path similar to that of the sympathetic nervous system, often in close proximity to blood vessels.4 The origins of embryology explain far more of the visceral pain patterns than anything else (see discussion in this chapter).

In the early stage of visceral disease, sympathetic reflexes arising from afferent impulses of the internal viscera may be expressed first as sensory, motor, and/or trophic changes in the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and/or muscles. As mentioned earlier, this can present as itching, dysesthesia, skin temperature changes, or dry skin. The viscera do not perceive pain, but the sensory side is trying to get the message out that something is wrong by creating sympathetic sudomotor changes.

It appears that there is not one specific group of spinal neurons that respond only to visceral inputs. Since messages from the soma and viscera come into the cord at the same level (and sometimes visceral afferents converge over several segments of the spinal cord), the nervous system has trouble deciding: Is it somatic or visceral? It sends efferent information back out to the plexus for change or reaction, but the input results in an unclear impulse at the cord level.

The body may get skin or somatic responses such as muscle pain or aching periosteum or it may tell a viscus innervated at the same level to do something it can do (e.g., the stomach increases its acid content). This also explains how sympathetic signals from the liver to the spinal cord can result in itching or other sudomotor responses in the area embryologically related to the liver.4

This somatization of visceral pain is why we must know the visceral pain patterns and the spinal versus visceral innervations. We examine one (somatic) while screening for the other (viscera).

Because the somatic and visceral afferent messages enter at the same level, it is possible to get somatic-somatic reflex responses (e.g., a bruise on the leg causes knee pain), somato-visceral reflex responses (e.g., a biomechanical dysfunction of the tenth rib can cause gallbladder changes), or viscero-somatic reflex responses (e.g., gallbladder impairment can result in a sore 10th rib; pelvic floor dysfunction can lead to incontinence; heart attack causes arm or jaw pain). These are actually all referred pain patterns originating in the soma or the viscera.

A more in-depth discussion of the visceral-somatic response is available.60 A visceral-somatic response can occur when biochemical changes associated with visceral disease affect somatic structures innervated by the same spinal nerves.

Prior to her death, Dr. Janet Travell60 was researching how often people with anginal pain are really experiencing residual pectoralis major TrPs caused by previous episodes of angina or MI. This is another example of the viscero-somatic response mentioned.

A viscero-viscero reflex (also referred to as cross-organ sensitization) occurs when pain or dysfunction in one organ causes symptoms in another organ.3 For example, the client presents with chest pain and has an extensive cardiac workup with normal findings. The client may be told “it’s not in your heart, so don’t worry about it.”

The problem may really be the gallbladder. Because the gallbladder originates from the same tissue embryologically as the heart, gallbladder impairment can cause cardiac changes in addition to shoulder pain from its contact with the diaphragm. This presentation is then confused with cardiac pathology.4

On the other hand, the doctor may do a gallbladder workup and find nothing. The chest pain could be coming from arthritic changes in the cervical spine. This occurs because the cervical spine and heart share common sensory pathways from C3 to the spinal cord.

Information from the cardiac plexus and brachial plexus enter the cord at the same level. The nervous system is not able to identify who sent the message, just what level it came from. It responds as best it can, based on the information present, sometimes resulting in the wrong symptoms for the problem at hand.

Pain and symptoms of a visceral source are usually accompanied by an ANS response such as a change in vital signs, unexplained perspiration (diaphoresis), and/or skin pallor. Signs and symptoms associated with the involved organ system may also be present. We call these associated signs and symptoms. They are red flags in the screening process.

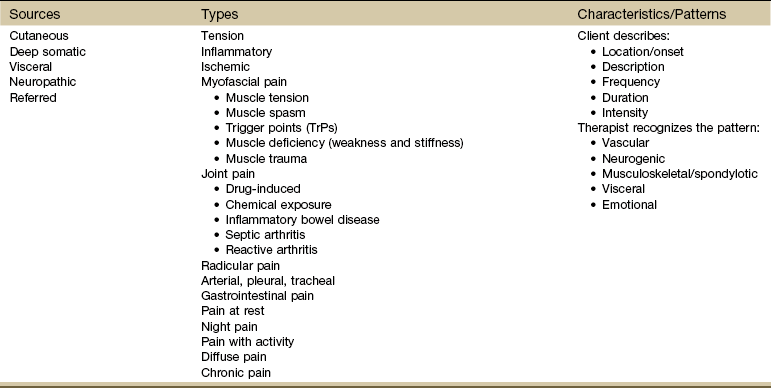

Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic or neurogenic pain results from damage to or pathophysiologic changes of the peripheral or central nervous system (CNS).61 Neuropathic pain can occur as a result of injury or destruction to the peripheral nerves, pathways in the spinal cord, or neurons located in the brain. Neuropathic pain can be acute or chronic depending on the timeframe.

This type of pain is not elicited by the stimulation of nociceptors or kinesthetic pathways as a result of tissue damage but rather by malfunction of the nervous system itself.58 Disruptions in the transmission of afferent and efferent impulses in the periphery, spinal cord, and brain can give rise to alterations in sensory modalities (e.g., touch, pressure, temperature), and sometimes motor dysfunction.

It can be drug-induced, metabolic-based, or brought on by trauma to the sensory neurons or pathways in either the peripheral nervous system or CNS. It appears to be idiosyncratic: not all individuals with the same lesion will have pain.62 Some examples are listed in Table 3-4.

It is usually described as sharp, shooting, burning, tingling, or producing an electric shock sensation. The pain is steady or evoked by some stimulus that is not normally considered noxious (e.g., light touch, cold). Some affected individuals report aching pain. There is no muscle spasm in neurogenic pain.58 Acute nerve root irritation tends to be severe, described as burning, shooting, and constant. Chronic nerve root pain is more often described as annoying or nagging.

Neuropathic pain is not alleviated by opiates or narcotics, although local anesthesia can provide temporary relief. Medications used to treat neuropathic pain include antidepressants, anticonvulsants, antispasmodics, adrenergics, and anesthetics. Many clients have a combination of neuropathic and somatic pain, making it more difficult to identify the underlying pathology.

Referred Pain

By definition, referred pain is felt in an area far from the site of the lesion but supplied by the same or adjacent neural segments. Referred pain occurs by way of shared central pathways for afferent neurons and can originate from any somatic or visceral source (primary cutaneous pain is not usually referred to other parts of the body).

Referred pain can occur alone or with accompanying deep somatic or visceral pain. When caused by an underlying visceral or systemic disease, visceral pain usually precedes the development of referred musculoskeletal pain. However, the client may not remember or mention this previous pain pattern … and the therapist has not asked about the presence of any other symptoms.

Referred pain is usually well localized (i.e., the person can point directly to the area that hurts), but it does not have sharply defined borders. It can spread or radiate from its point of origin. Local tenderness is present in the tissue of the referred pain area, but there is no objective sensory deficit. Referred pain is often accompanied by muscle hypertonus over the referred area of pain.

Visceral disorders can refer pain to somatic tissue (see Table 3-8). On the other hand, as mentioned in the last topic on visceral sources of pain, some somatic impairments can refer pain to visceral locations or mimic known visceral pain patterns. Finding the original source of referred pain can be quite a challenge (Case Example 3-3).

Always ask one or both of these two questions in your pain interview as part of the screening process:

Differentiating Sources of Pain4

How do we differentiate somatic sources of pain from visceral sources? It can be very difficult to make this distinction. That is one reason why clients end up in physical therapy even though there is a viscerogenic source of the pain and/or symptomatic presentation.

The superficial and deep somatic structures are innervated unilaterally via the spinal nerves, whereas the viscera are innervated bilaterally through the ANS via visceral afferents. The quality of superficial somatic pain tends to be sharp and more localized. It is mediated by large myelinated fibers, which have a low threshold for stimulation and a fast conduction time. This is designed to protect the structures by signaling a problem right away.

Deep somatic pain is more likely to be a dull or deep aching that responds to rest or a non–weight-bearing position. Deep somatic pain is often poorly localized (transmission via small unmyelinated fibers) and can be referred from some other site.

Pain of a deep somatic nature increases after movement. Sometimes the client can find a comfortable spot, but after moving the extremity or joint, cannot find that comfortable spot again. This is in contrast to visceral pain, which usually is not reproduced with movement, but rather, tends to hurt all the time or with all movements.4

Pain from a visceral source can also be dull and aching, but usually does not feel better after rest or recumbency. Keep in mind pathologic processes occurring within somatic structures (e.g., metastasis, primary tumor, infection) may produce localized pain that can be mechanically irritated. This is why movement in general (rather than specific motions) can make it worse. Back pain from metastasis to the spine can become quite severe before any radiologic changes are seen.4

Visceral diseases of the abdomen and pelvis are more likely to refer pain to the back, whereas intrathoracic disease refers pain to the shoulder(s). Visceral pain rarely occurs without associated signs and symptoms, although the client may not recognize the correlation. Careful questioning will usually elicit a systemic pattern of symptoms.

Back or shoulder range of motion (ROM) is usually full and painless in the presence of visceral pain, especially in the early stages of disease. When the painful stimulus increases or persists over time, pain-modifying behaviors, such as muscle splinting and guarding, can result in subsequent changes in biomechanical patterns and pain-related disability63 and may make it more difficult to recognize the systemic origin of musculoskeletal dysfunction.

Types of Pain

Although there are five sources of most physiologic pain (from a medical screening perspective), many types of pain exist within these categories (see Table 3-3).

When orienting to pain from these main sources, it may be helpful to consider some specific types of pain patterns. Not all pain types can be discussed here, but some of the most commonly encountered are included.

Tension Pain

Organ distention, such as occurs with bowel obstruction, constipation, or the passing of a kidney stone, can cause tension pain. Tension pain can also be caused by blood pooling from trauma and pus or fluid accumulation from infection or other underlying causes. In the bowel, tension pain may be described as “colicky” with waves of pain and tension occurring intermittently as peristaltic contractile force moves irritating substances through the gastrointestinal (GI) system. Tension pain makes it difficult to find a comfortable position.

Inflammatory Pain

Inflammation of the viscera or parietal peritoneum (e.g., acute appendicitis) may cause pain that is described as deep or boring. If the visceral peritoneum is involved, then the pain is usually poorly localized. If the parietal peritoneum is the primary area affected, the pain pattern may become more localized (i.e., the affected individual can point to it with one or two fingers). Pain arising from inflammation causes people to seek positions of quiet with little movement.

Ischemic Pain

Ischemia denotes a loss of blood supply. Any area without adequate perfusion will quickly die. Ischemic pain of the viscera is sudden, intense, constant, and progressive in severity or intensity. It is not typically relieved by analgesics, and no position is comfortable. The person usually avoids movement or change in positions.

Myofascial Pain

Myalgia, or muscle pain, can be a symptom of an underlying systemic disorder. Cancer, renal failure, hepatic disease, and endocrine disorders are only a few possible systemic sources of muscle involvement.

For example, muscle weakness, atrophy, myalgia, and fatigue that persist despite rest may be early manifestations of thyroid or parathyroid disease, acromegaly, diabetes, Cushing’s syndrome, or osteomalacia.

Myalgia can be present in anxiety and depressive disorders. Muscle weakness and myalgia can occur as a side effect of drugs. Prolonged use of systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs has known adverse effects on the musculoskeletal system, including degenerative myopathy with muscle wasting and tendon rupture.

Infective endocarditis caused by acute bacterial infection can present with myalgias and no other manifestation of endocarditis. The early onset of joint pain and myalgia as the first sign of endocarditis is more likely if the person is older and has had a previously diagnosed heart murmur. Joint pain (arthralgia) often accompanies myalgia, and the client is diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis.

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PR), which literally means “pain in many muscles,” is a disorder marked by diffuse pain and stiffness that primarily affects muscles of the shoulder and pelvic girdles.

With PR, symptoms are vague and difficult to diagnose resulting in delay in medical treatment. The person may wake up one morning with muscle pain and stiffness for no apparent reason or the symptoms may come on gradually over several days or weeks. Adults over age 50 are affected most often (white women have the highest incidence); most cases occur after age 70.64

Temporal arteritis occurs in 25% of all cases of PR. Watch for headache, visual changes (blurred or double vision), intermittent jaw pain (claudication), and cranial nerve involvement. The temporal artery may be prominent and painful to touch, and the temporal pulse absent.

From a screening point of view, there are many types of muscle-related pain such as tension, spasm, weakness, trauma, inflammation, infection, neurologic impairment, and trigger points (see Table 3-3).65 The clinical presentation most common with systemic disease is presented here.

Muscle Tension

Muscle tension, or sustained muscle tone, occurs when prolonged muscular contraction or co-contraction results in local ischemia, increased cellular metabolites, and subsequent pain. Ischemia as a factor in muscle pain remains controversial. Interruption of blood flow in a resting extremity does not cause pain unless the muscle contracts during the ischemic condition.66

Muscle tension also can occur with physical stress and fatigue. Muscle tension and the subsequent ischemia may occur as a result of faulty ergonomics, prolonged work positions (e.g., as with computer or telephone operators), or repetitive motion.

Take for example the person sitting at a keyboard for hours each day. Constant typing with muscle co-contraction does not allow for the normal contract-relax sequence. Muscle ischemia results in greater release of substance P, a pain neurotransmitter (neuropeptide).

Increased substance P levels increase pain sensitivity. Increased pain perception results in more muscle spasm as a splinting or protective guarding mechanism, and thus the pain-spasm cycle is perpetuated. This is a somatic-somatic response.

Muscle tension from a visceral-somatic response can occur when pain from a visceral source results in increased muscle tension and even muscle spasm. For example, the pain from any inflammatory or infectious process affecting the abdomen (e.g., appendicitis, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease) can cause increased tension in the abdominal muscles.

Given enough time and combined with overuse and repetitive use or infectious or inflammatory disease, muscle tension can turn into muscle spasm. When opposing muscles such as the flexors and extensors contract together for long periods of time (called co-contraction), muscle tension and then muscle spasm can occur.

Muscle Spasm

Muscle spasm is a sudden involuntary contraction of a muscle or group of muscles, usually occurring as a result of overuse or injury of the adjoining NMS or musculotendinous attachments. A person with a painful musculoskeletal problem may also have a varying degree of reflex muscle spasm to protect the joint(s) involved (a somatic-somatic response). A client with painful visceral disease can have muscle spasm of the overlying musculature (a viscero-somatic response).

Spasm pain cannot be attributed to transient increased muscle tension because the intramuscular pressure is insufficiently elevated. Pain with muscle spasm may occur from prolonged contraction under an ischemic situation. An increase in the partial pressure of oxygen has been documented inside the muscle in spasm under these circumstances.67

Muscle Trauma

Muscle trauma can occur with acute trauma, burns, crush injuries, or unaccustomed intensity or duration of muscle contraction, especially eccentric contractions. Muscle pain occurs as broken fibers leak potassium into the interstitial fluid. Blood extravasation results from damaged blood vessels, setting off a cascade of chemical reactions within the muscle.66

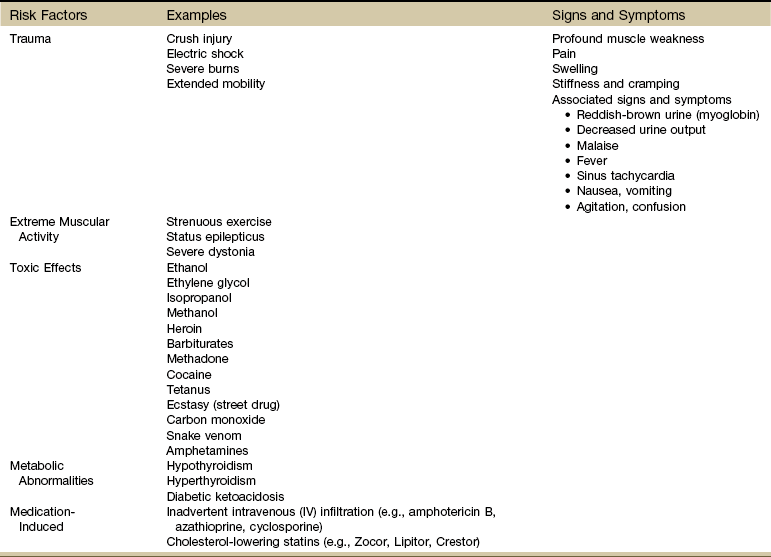

When disintegration of muscle tissue occurs with release of their contents (e.g., oxygen-transporting pigment myoglobin) into the bloodstream, a potentially fatal muscle toxicity called rhabdomyolysis can occur. Risk factors and clinical signs and symptoms are listed in Table 3-5. Immediate medical attention is required (Case Example 3-4).

Muscle Deficiency

Muscle deficiency (weakness and stiffness) is a common problem as we age and even among younger adults who are deconditioned. Connective tissue changes may occur as small amounts of fibrinogen (produced in the liver and normally converted to fibrin to serve as a clotting factor) leak from the vasculature into the intracellular spaces, adhering to cellular structures.

The resulting microfibrinous adhesions among the cells of muscle and fascia cause increased muscular stiffness. Activity and movement normally break these adhesions; however, with the aging process, production of fewer and less efficient macrophages combined with immobility for any reason result in reduced lysis of these adhesions.68

Other possible causes of aggravated stiffness include increased collagen fibers from reduced collagen turnover, increased cross-links of aged collagen fibers, changes in the mechanical properties of connective tissues, and structural and functional changes in the collagen protein. Tendons and ligaments also have less water content, resulting in increased stiffness.69

When muscular stiffness occurs as a result of aging, increased physical activity and movement can reduce associated muscular pain. As part of the diagnostic evaluation, consider a general conditioning program for the older adult reporting generalized muscle pain. Even 10 minutes a day on a stationary bike, on a treadmill, or in an aquatics program can bring dramatic and fast relief of painful symptoms when caused by muscle deficiency.

Proximal muscle weakness accompanied by change in one or more deep tendon reflexes is a red flag sign of cancer or neurologic impairment. In the presence of a past medical history of cancer, further screening is advised with possible medical referral required, depending on the outcome of the examination/evaluation.

Trigger Points

TrPs, sometimes referred to as myofascial TrPs (MTrPs), are hyperirritable spots within a taut band of skeletal muscle or in the fascia. Taut bands are ropelike indurations palpated in the muscle fiber. These areas are very tender to palpation and are referred to as local tenderness.70 There is often a history of immobility (e.g., cast immobilization after fracture or injury), prolonged or vigorous activity such as bending or lifting, or forceful abdominal breathing such as occurs with marathon running.

TrPs are reproduced with palpation or resisted motions. When pressing on the TrP, you may elicit a “jump sign.” Some people say the jump sign is a local twitch response of muscle fibers to trigger point stimulation, but this is an erroneous use of the term.60

The jump sign is a general pain response as the client physically withdraws from the pressure on the point and may even cry out or wince in pain. The local twitch response is the visible contraction of tense muscle fibers in response to stimulation.

When TrPs are compressed, local tenderness with possible referred pain results. In other words, pain that arises from the trigger point is felt at a distance, often remote from its source.

The referred pain pattern is characteristic and specific for every muscle. Knowing the TrP locations and their referred pain patterns is helpful. By knowing the pain patterns, you can go to the site of origin and confirm (or rule out) the presence of the TrP. The distribution of referred TrP pain rarely coincides entirely with the distribution of a peripheral nerve or dermatomal segment.60

TrPs can be categorized as active, latent, key, or satellite. Active TrPs refer pain locally or to another location and can cause pain at rest. Latent TrPs do not cause spontaneous pain but generate referred pain when the affected muscle(s) are put under pressure, palpated, or strained. Key TrPs have a pain-referral pattern along nerve pathways, and satellite TrPs are set off by key trigger points.

In the screening process, TrPs must be eliminated to rule out systemic pathology as a cause of muscle pain. Beware when your client fails to respond to TrP therapy. Consider this situation a yellow flag. It is not necessarily a red flag suggesting the need for screening for systemic or other causes of muscle pain. Muscle recovery from TrPs is not always so simple.

Muscles with active TrPs fatigue faster and recover more slowly. They show more abnormal neural circuit dysfunction. The pain and spasm of TrPs may not be relieved until the aberrant circuits are corrected.71

Any compromise of muscle energy metabolism, such as occurs with endocrine or cancer-related disorders, can aggravate and perpetuate TrPs making successful intervention a more challenging and lengthy process.

Remember, too, that visceral disease can create tender points. For those who understand the Jones’ Strain/Counterstrain concept, some of the Jones’ points might happen to fall in the same area as viscerogenic tender point, but the two are not the same points. A careful evaluation is required to differentiate between Jones’ points and viscerogenic tender points.

Travell’s TrPs can also produce visceral symptoms without actual organ impairment or disease. This is an example of a somato-visceral response. For example, the client may have an abdominal muscle TrP, but the history is one of upset stomach or chest (cardiac) pain. It is possible to have both tender points and TrPs when the underlying cause is visceral disease.

Pain and dysfunction of myofascial tissues is the subject of several texts to which the reader is referred for more information.60,72,73

Joint Pain

Noninflammatory joint pain (no redness, no warmth, no swelling) of unknown etiology can be caused by a wide range of pathologic conditions (Box 3-4). Fibromyalgia, leukemia, sexually transmitted infections, artificial sweeteners,74-76 Crohn’s disease (also known as regional enteritis), postmenopausal status or low estrogen levels, and infectious arthritis are all possible causes of joint pain.

Joint pain in the presence of fatigue may be a red flag for anxiety, depression, or cancer. The client history and screening interview may help the therapist find the true cause of joint pain. Look for risk factors for any of the listed conditions and review the client’s recent activities.

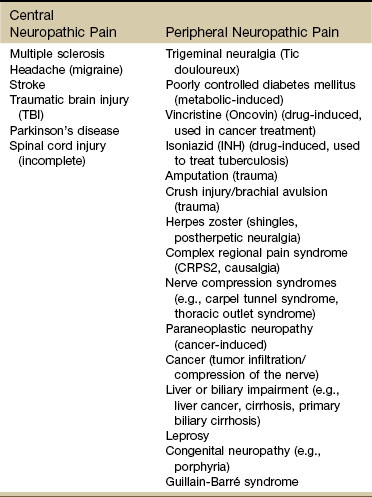

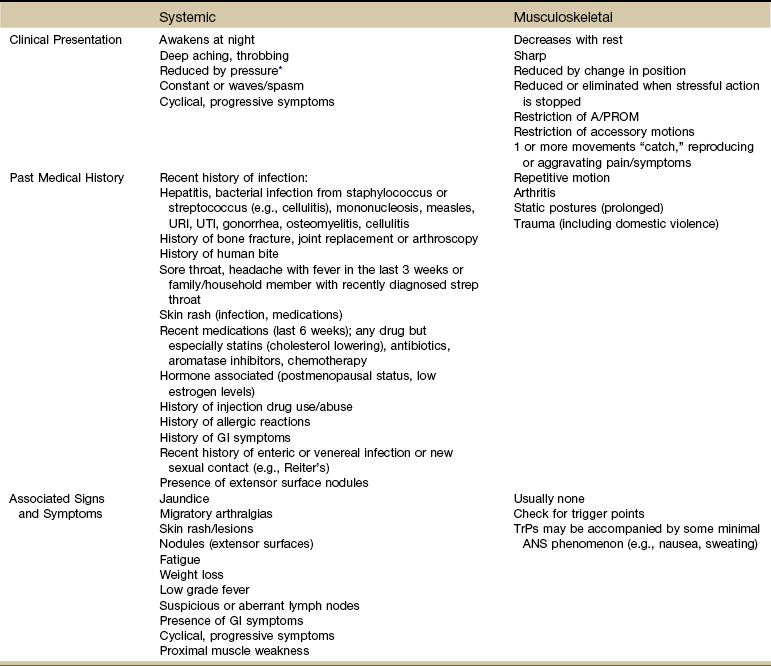

When comparing joint pain associated with systemic versus musculoskeletal causes, one of the major differences is in the area of associated signs and symptoms (Table 3-6). Joint pain of a systemic or visceral origin usually has additional signs or symptoms present. The client may not realize there is a connection, or the condition may not have progressed enough for associated signs and symptoms to develop.

TABLE 3-6

Joint Pain: Systemic or Musculoskeletal?

A/PROM, Active/passive range of motion; URI, upper respiratory infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; GI, gastrointestinal; TrPs, trigger points; ANS, autonomic nervous system.

*This is actually a cutaneous or somatic response because the pressure provides a counterirritant; it does not really affect the viscera directly.

The therapist also evaluates joint pain over a 24-hour period. Joint pain from a systemic cause is more likely to be constant and present with all movements. Rest may help at first but over time even this relieving factor will not alter the symptoms. This is in comparison to the client with osteoarthritis (OA), who often feels better after rest (though stiffness may remain). Morning joint pain associated with OA is less than joint pain at the end of the day after using the joint(s) all day.

On the other hand, muscle pain may be worse in the morning and gradually improves as the client stretches and moves about during the day. The Pain Assessment Record Form (see Fig. 3-6) includes an assessment of these differences across a 24-hour span as part of the “Pattern.”

The therapist can use the specific screening questions for joint pain to assess any joint pain of unknown cause or with an unusual presentation or history. Joint pain and symptoms that do not fit the expected pattern for injury, overuse, or aging can be screened using a few important questions (Box 3-5).

Drug-Induced

Joint pain as an allergic response, sometimes referred to as “serum sickness” can occur up to 6 weeks after taking a prescription drug (especially antibiotics). Joint pain is also a potential side effect of statins (e.g., Lipitor, Zocor). These are cholesterol-lowering agents.

Musculoskeletal symptoms (e.g., morning stiffness, bone pain, arthralgia, arthritis) are a well-known side effect of chemotherapy and aromatase inhibitors used in the treatment of breast cancer. Low estrogen concentrations and postmenopausal status are linked with these symptoms. Risk factors for developing joint symptoms may include previous hormone replacement therapy, hormone-receptor positivity, previous chemotherapy, obesity, and treatment with anastrozole (Arimidex—aromatase inhibitor).77

Noninflammatory joint pain is typical of a delayed allergic reaction. The client may report fever, skin rash, and fatigue that go away when the drug is stopped.

Chemical Exposure

Likewise, delayed reactions can occur as a result of occupational or environmental chemical exposure. A work and/or military history may be required for anyone presenting with joint or muscle pain or symptoms of unknown cause. These clients can be mislabeled with a diagnosis of autoimmune disease or fibromyalgia. The alert therapist may recognize and report clues to help the client obtain a more accurate diagnosis.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and regional enteritis (Crohn’s disease [CD]) are accompanied by an arthritic component and skin rash in about 25% of all people affected by this inflammatory bowel condition.

The person may have a known diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) but may not know that new onset of joint symptoms can be part of this condition. The client interview should have brought out the personal history of either UC or CD. See the discussion of IBD in Chapter 8.

Peripheral joint disease associated with IBD involves the large joints, most often a single hip or knee. Joint symptoms often occur simultaneously with UC but less often at the same time as CD. Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is also possible with either form of IBD.

As with typical AS, symptoms affect the low back, sacrum, or SI joint first. The most common symptoms are intermittent low back pain with decreased low back motion. The course of AS associated with IBD is the same as without the bowel component.

Joint problems usually respond to medical treatment of the underlying bowel disease but in some cases require separate management. Interventions for the musculoskeletal involvement follow the usual protocols for each area affected.

Arthritis

Joint pain (either inflammatory or noninflammatory) can be associated with a wide range of systemic causes, including bacterial or viral infection, trauma, and sexually transmitted diseases. There is usually a positive history or other associated signs and symptoms to help the therapist identify the need for medical referral.

Infectious Arthritis: Joint pain can be a local response to an infection. This is called infectious, septic, or bacterial arthritis. Invading microorganisms cause inflammation of the synovial membrane with release of cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor [TNF], interleukin-1 [IL-1]) and proteases. The end result can be cartilage destruction even after eradicating the offending organism.78

Bacteria can find its way to the joint via the bloodstream (most common) by:

• Direct inoculation (e.g., surgery, arthroscopy, intraarticular corticosteroid injection, central line placement, total joint replacement)

• Penetrating wound (e.g., human bite or fracture)

• Direct extension (e.g., osteomyelitis, cellulitis, diverticulitis, abscess)