Screening for Hematologic Disease

The blood consists of two major components: plasma, a pale yellow or gray-yellow fluid; and formed elements, erythrocytes (red blood cells [RBCs]), leukocytes (white blood cells [WBCs]), and platelets (thrombocytes). Blood is the circulating tissue of the body; the fluid and its formed elements circulate through the heart, arteries, capillaries, and veins.

The erythrocytes carry oxygen to tissues and remove carbon dioxide from them. Leukocytes act in inflammatory and immune responses. The plasma carries antibodies and nutrients to tissues and removes wastes from tissues. Platelets, together with coagulation factors in plasma, control the clotting of blood.

Primary hematologic diseases are uncommon, but hematologic manifestations secondary to other diseases are common. Cancers of the blood are discussed in Chapter 13.

In the physical therapist’s practice, symptoms of blood disorders are most common in relation to the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for inflammatory conditions, neurologic complications associated with pernicious anemia, and complications of chemotherapy or radiation.

Hematologic considerations in the orthopedic population fall into two main categories: bleeding and clotting. People with known abnormalities of hemostasis (either hypocoagulation or hypercoagulation problems) will require close observation.1

All surgical patients, neurologically compromised, or immobilized individuals must also be observed carefully for any signs or symptoms of venous thromboembolism.

Signs and Symptoms of Hematologic Disorders

There are many signs and symptoms that can be associated with hematologic disorders. Some of the most important indicators of dysfunction in this system include problems associated with exertion (often minimal exertion) such as dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, severe weakness, and fatigue. Neurologic symptoms, such as headache, drowsiness, dizziness, syncope, or polyneuropathy, can also indicate a variety of possible problems in this system.2,3

Significant skin and fingernail bed changes that can occur with hematologic problems might include pallor of the face, hands, nail beds, and lips; cyanosis or clubbing of the fingernail beds; and wounds or easy bruising or bleeding in skin, gums, or mucous membranes, often with no reported trauma to the area. The presence of blood in the stool or emesis or severe pain and swelling in joints and muscles should also alert the physical therapist to the possibility of a hematologic-based systemic disorder and can sometimes be a critical indicator of bleeding disorders that can be life threatening.2,3

Many hematologic-induced signs and symptoms seen in the physical therapy practice occur as a result of medications. For example, chronic or long-term use of steroids and NSAIDs can lead to gastritis and peptic ulcer with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and subsequent iron deficiency anemia.4 Leukopenia, a common problem occurring during chemotherapy, or as a symptom of certain types of cancer, can produce symptoms of infections such as fever, chills, tissue inflammation; severe mouth, throat and esophageal pain; and mucous membrane ulcerations.5

Thrombocytopenia (decreased platelets) associated with easy bruising and spontaneous bleeding is a result of the pharmacologic treatment of common conditions seen in a physical therapy practice such as rheumatoid arthritis and cancer. More about this condition will be included later in this chapter.

Classification of Blood Disorders

Erythrocytes (red blood cells) consist mainly of hemoglobin and a supporting framework. Erythrocytes transport oxygen and carbon dioxide; they are important in maintaining normal acid-base balance. There are many more erythrocytes than leukocytes (600 to 1). The total number is determined by gender (women have fewer erythrocytes than men), altitude (less oxygen in the air requires more erythrocytes to carry sufficient amounts of oxygen to the tissues), and physical activity (sedentary people have fewer erythrocytes, athletes have more).

Disorders of erythrocytes are classified as follows (not all of these conditions are discussed in this text):

• Anemia (too few erythrocytes)

• Polycythemia (too many erythrocytes)

• Poikilocytosis (abnormally shaped erythrocytes)

• Anisocytosis (abnormal variations in size of erythrocytes)

Anemia

Anemia is a reduction in the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood as a result of an abnormality in the quantity or quality of erythrocytes. Anemia is not a disease but is a symptom of any number of different blood disorders. Excessive blood loss, increased destruction of erythrocytes, and decreased production of erythrocytes are the most common causes of anemia.6

In the physical therapy practice, anemia-related disorders usually occur in one of four broad categories:

1. Iron deficiency associated with chronic GI blood loss secondary to NSAID use

2. Chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, kidney disease, liver disease) or inflammatory diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus)

3. Neurologic conditions (pernicious anemia)

4. Infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and neoplastic disease or cancer (bone marrow failure).

Anemia with neoplasia may be a common complication of chemotherapy or develop as a consequence of bone marrow metastasis.7 Anemia can also occur as a symptom of leukemia. Adults with pernicious anemia have significantly higher risks for hip fracture even with vitamin B12 therapy. The hypothesized underlying factor is a lack of gastric acid (achlorhydria).8

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Deficiency in the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood may result in disturbances in the function of many organs and tissues leading to various symptoms that differ from one person to another. Slowly developing anemia in young, otherwise healthy individuals is well tolerated, and there may be no symptoms until hemoglobin concentration and hematocrit fall below one half of normal (see values inside book cover).

However, rapid onset may result in symptoms of dyspnea, weakness and fatigue, and palpitations, reflecting the lack of oxygen transport to the lungs and muscles. Many people can have moderate-to-severe anemia without these symptoms. Although there is no difference in normal blood volume associated with severe anemia, there is a redistribution of blood so that organs most sensitive to oxygen deprivation (e.g., brain, heart, muscles) receive more blood than, for example, the hands and kidneys.

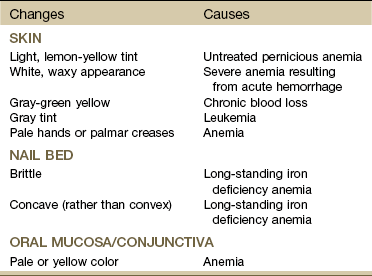

Changes in the hands and fingernail beds (Table 5-1) may be observed during the inspection/observation portion of the physical therapy evaluation (see Table 4-8 and Boxes 4-13 and 4-15). The physical therapist should look for pale palms with normal-colored creases (severe anemia causes pale creases as well). Observation of the hands should be done at the level of the client’s heart. In addition, the anemic client’s hands should be warm; if they are cold, the paleness is due to vasoconstriction.

Pallor in dark-skinned people may be observed by the absence of the underlying red tones that normally give brown or black skin its luster. The brown-skinned individual demonstrates pallor with a more yellowish-brown color, and the black-skinned person will appear ashen or gray.

Systolic blood pressure may not be affected, but diastolic pressure may be lower than normal, with an associated increase in the resting pulse rate. Resting cardiac output is usually normal in people with anemia, but cardiac output increases with exercise more than it does in people without anemia.9 As the anemia becomes more severe, resting cardiac output increases and exercise tolerance progressively decreases until dyspnea, tachycardia, and palpitations occur at rest.

Diminished exercise tolerance is expected in the client with anemia. Exercise testing and prescribed exercise(s) in clients with anemia must be instituted with extreme caution and should proceed very gradually to tolerance and/or perceived exertion levels.10,11 In addition, exercise for any anemic client should be first approved by his or her physician (Case Example 5-1).

Polycythemia

Polycythemia (also known as erythrocytosis) is characterized by increases in both the number of red blood cells and the concentration of hemoglobin. People with polycythemia have increased whole blood viscosity and increased blood volume.

The increased erythrocyte production results in this thickening of the blood and an increased tendency toward clotting. The viscosity of the blood limits its ability to flow easily, diminishing the supply of blood to the brain and to other vital tissues. Increased platelets in combination with the increased blood viscosity may contribute to the formation of intravascular thrombi.

There are two distinct forms of polycythemia: primary polycythemia (also known as polycythemia vera) and secondary polycythemia. Primary polycythemia is a relatively uncommon neoplastic disease of the bone marrow of unknown etiology. Secondary polycythemia is a physiologic condition resulting from a decreased oxygen supply to the tissues. It is associated with high altitudes, heavy tobacco smoking, radiation exposure, and chronic heart and lung disorders, especially congenital heart defects.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: The symptoms of this disease are often insidious in onset with vague complaints. The most common first symptoms are shortness of breath and fatigue. The affected individual may be diagnosed only secondary to a sudden complication (e.g., stroke or thrombosis). Increased skin coloration and elevated blood pressure may develop as a result of the increased concentration of erythrocytes and increased blood viscosity.

Gout is sometimes a complication of primary polycythemia, and a typical attack of acute gout may be the first symptom of polycythemia. Gout is a metabolic disease marked by increased serum urate levels (hyperuricemia), which cause painfully arthritic joints. Uric acid level is an end product of purine metabolism. Purine metabolism is altered by excessive cellular proliferation and breakdown associated with increased red cells, granulocytes, and platelets. Hyperuricemia is uncommon in secondary polycythemia because the cellular proliferation is not as extensive as in primary polycythemia.

Blockage of the capillaries supplying the digits of either the hands or the feet may cause a peripheral vascular neuropathy with decreased sensation, burning, numbness, or tingling. This small blood vessel occlusion can also contribute to the development of cyanosis and clubbing. If the underlying disorder is not recognized and treated, the person may develop gangrene and have subsequent loss of tissue.

Watch for increase in blood pressure and elevated hematocrit levels.

Sickle Cell Anemia

Sickle cell disease is a generic term for a group of inherited, autosomal recessive disorders characterized by the presence of an abnormal form of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying constituent of erythrocytes. A genetic mutation resulting in a single amino acid substitution in hemoglobin causes the hemoglobin to aggregate into long chains, altering the shape of the cell. This sickled or curved shape causes the cell to lose its ability to deform and squeeze through tiny blood vessels, thereby depriving tissue of an adequate blood supply.3

The two features of sickle cell disorders, chronic hemolytic anemia and vasoocclusion, occur as a result of obstruction of blood flow to the tissues and early destruction of the abnormal cells. Anemia associated with this condition is merely a symptom of the disease and not the disease itself, despite the term sickle cell anemia.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: A series of “crises,” or acute manifestations of symptoms, characterize sickle cell disease. Some people with this disease have only a few symptoms, whereas others are affected severely and have a short lifespan. Recurrent episodes of vasoocclusion and inflammation result in progressive damage to most organs, including the brain, kidneys, lungs, bones, and cardiovascular system, which becomes apparent with increasing age. Cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) and cognitive impairment are a frequent and severe manifestation.16

Stress from viral or bacterial infection, hypoxia, dehydration, emotional disturbance, extreme temperatures, fever, strenuous physical exertion, or fatigue may precipitate a crisis. Pain caused by the blockage of sickled RBCs forming sickle cell clots is the most common symptom; it may be in any organ, bone, or joint of the body. Painful episodes of ischemic tissue damage may last 5 or 6 days and manifest in many different ways, depending on the location of the blood clot (Case Example 5-2).

Leukocyte Disorders

The blood contains three major groups of leukocytes, including:

Lymphocytes produce antibodies and react with antigens, thus initiating the immune response to fight infection. Monocytes are the largest circulating blood cells and represent an immature cell until they leave the blood and travel to the tissues where they form macrophages in response to foreign substances such as bacteria. Granulocytes contain lysing agents capable of digesting various foreign materials and defend the body against infectious agents by phagocytosing bacteria and other infectious substances.17

Disorders of leukocytes are recognized as the body’s reaction to disease processes and noxious agents. The therapist will encounter many clients who demonstrate alterations in the blood leukocyte (WBC) concentration as a result of acute infections or chronic systemic conditions. The leukocyte count also may be elevated (leukocytosis) in women who are pregnant; in clients with bacterial infections, appendicitis, leukemia, uremia, or ulcers; in newborns with hemolytic disease; and normally at birth. The leukocyte count may drop below normal values (leukopenia) in clients with viral diseases (e.g., measles), infectious hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, cirrhosis of the liver, and lupus erythematosus and also after treatment with radiation or chemotherapy.

Leukocytosis

Leukocytosis characterizes many infectious diseases and is recognized by a count of more than 10,000 leukocytes/mm3. It can be associated with an increase in circulating neutrophils (neutrophilia), which are recruited in large numbers early in the course of most bacterial infections.

Leukocytosis is a common finding and is helpful in aiding the body’s response to any of the following:

Leukopenia

Leukopenia, or reduction of the number of leukocytes in the blood below 5000/mL, can be caused by a variety of factors. Unlike leukocytosis, leukopenia is never beneficial.

Leukopenia can occur in many forms of bone marrow failure such as that following antineoplastic chemotherapy or radiation therapy, in overwhelming infections, in dietary deficiencies, and in autoimmune diseases.2

It is important for the physical therapist to be aware of the client’s most recent WBC count prior to and during the course of physical therapy. If the client is immunosuppressed, infection is a major problem. Constitutional symptoms, such as fever, chills, or sweats, warrant immediate medical referral.

Nadir, or the lowest point the WBC count reaches, usually occurs 7 to 14 days after chemotherapy or radiation therapy. At this time, the client is extremely susceptible to opportunistic infections and severe complications. The importance of good handwashing and hygiene practices cannot be overemphasized when treating any of these clients.7

Leukemia

Leukemia is a disease arising from the bone marrow and involves the uncontrolled growth of immature or dysfunctional WBCs; a complete discussion of this cancer is found in Chapter 13.

Platelet Disorders

Platelets (thrombocytes) function primarily in hemostasis (stopping bleeding) and in maintaining capillary integrity (see normal values listed inside book cover). They function in the coagulation (blood clotting) mechanism by forming hemostatic plugs in small ruptured blood vessels or by adhering to any injured lining of larger blood vessels.

A number of substances derived from the platelets that function in blood coagulation have been labeled “platelet factors.” Platelets survive approximately 8 to 10 days in circulation and are then removed by the reticuloendothelial cells. Thrombocytosis refers to a condition in which the number of platelets is abnormally high, whereas thrombocytopenia refers to a condition in which the number of platelets is abnormally low.

Platelets are affected most often by anticoagulant drugs, including aspirin, heparin, warfarin (Coumadin), and other newer antithrombotic drugs now appearing on the market (e.g., Arixtra). Platelet levels can also be affected by diet (presence of lecithin preventing coagulation or vitamin K from promoting coagulation), by exercise that boosts the production of chemical activators that destroy unwanted clots, and by liver disease that affects the supply of vitamin K. Platelets are also easily suppressed by radiation and chemotherapy.2,3

Thrombocytosis

Thrombocytosis is an increase in platelet count that is usually temporary. It may be primary caused by unregulated production of platelets or secondary (reactive thrombocytosis) as a compensatory mechanism (exaggerated physiologic response) after severe hemorrhage, surgery, and splenectomy; in iron deficiency and polycythemia vera; and as a manifestation of an occult (hidden) neoplasm (e.g., lung cancer).18,19

It is associated with a tendency to clot because blood viscosity is increased by the very high platelet count, resulting in intravascular clumping (or thrombosis) of the sludged platelets. Peripheral blood vessels, particularly in the fingers and toes, are affected.

Thrombocytosis remains asymptomatic until the platelet count exceeds 1 million/mm3. Other symptoms may include splenomegaly and easy bruising.

Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia, a decrease in the number of platelets (less than 150,000/mm3) in circulating blood, can result from decreased or defective platelet production or from accelerated platelet destruction.

There are many causes of thrombocytopenia (Box 5-1). In a physical therapy practice the most common causes seen are bone marrow failure from radiation treatment, leukemia, or metastatic cancer; cytotoxic agents used in chemotherapy; and drug-induced platelet reduction, especially among adults with rheumatoid arthritis treated with gold or inflammatory conditions treated with aspirin or other NSAIDs.

Primary bleeding sites include bone marrow or spleen; secondary bleeding occurs from small blood vessels in the skin, mucosa (e.g., nose, uterus, GI tract, urinary tract, and respiratory tract), and brain (intracranial hemorrhage).

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Severe thrombocytopenia results in the appearance of multiple petechiae (small, purple, pinpoint hemorrhages into the skin), most often observed on the lower legs. GI bleeding and bleeding into the central nervous system (CNS) associated with severe thrombocytopenia may be life-threatening manifestations of thrombocytopenic bleeding.

The physical therapist must be alert for obvious skin, joint, or mucous membrane symptoms of thrombocytopenia, which include severe bruising, external hematomas, joint swelling, and the presence of multiple petechiae observed on the skin or gums. These symptoms usually indicate a platelet count well below 100,000/mm3. Strenuous exercise or any exercise that involves straining or bearing down could precipitate a hemorrhage, particularly of the eyes or brain. Blood pressure cuffs must be used with caution and any mechanical compression, visceral manipulation, or soft tissue mobilization is contraindicated without a physician’s approval.

People with undiagnosed thrombocytopenia need immediate physician referral. Exercise guidelines for thrombocytopenia can be found in Table 39-7 in Goodman’s Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist, second edition.

Coagulation Disorders

Hemophilia is a hereditary blood-clotting disorder caused by an abnormality of functional plasma-clotting proteins known as factors VIII and IX. In most cases, the person with hemophilia has normal amounts of the deficient factor circulating, but it is in a functionally inadequate state. Persons with hemophilia bleed longer than those with normal levels of functioning factors VIII or IX, but the bleeding is not any faster than would occur in a normal person with the same injury.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Bleeding into the joint spaces (hemarthrosis) is one of the most common clinical manifestations of hemophilia. It may result from an identifiable trauma or stress or may be spontaneous, most often affecting the knee, elbow, ankle, hip, and shoulder (in order of most common appearance).

Recurrent hemarthrosis results in hemophiliac arthropathy (joint disease) with progressive loss of motion, muscle atrophy, and flexion contractures. Bleeding episodes must be treated early with factor replacement and joint immobilization during the period of pain. This type of affected joint is particularly susceptible to being injured again, setting up a cycle of vulnerability to trauma and repeated hemorrhages.20

Hemarthroses are not common in the first year of life but increase in frequency as the child begins to walk. The severity of the hemarthrosis may vary (depending on the degree of injury) from mild pain and swelling, which resolves without treatment within 1 to 3 days, to severe pain with an excruciatingly painful, swollen joint that persists for several weeks and resolves slowly with treatment.

Bleeding into the muscles is the second most common site of bleeding in persons with hemophilia. Muscle hemorrhages can be more insidious and massive than joint hemorrhages. They may occur anywhere but are common in the flexor muscle groups, predominantly the iliopsoas, gastrocnemius, and flexor surface of the forearm, and they result in deformities such as hip flexion contractures, equinus position of the foot, or Volkmann’s deformity of the forearm.21 For a more in-depth discussion of hemophilia and the clinical signs and symptoms associated with it, see Table 14-8 in Goodman and Fuller’s Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist, third edition.

When bleeding into the psoas or iliacus muscle puts pressure on the branch of the femoral nerve supplying the skin over the anterior thigh, loss of sensation occurs. Distention of the muscles with blood causes pain that can be felt in the lower abdomen, possibly even mimicking appendicitis when bleeding occurs on the right side. In an attempt to relieve the distention and reduce the pain, a position with hip flexion is preferred.

Two tests are used to distinguish an iliopsoas bleed from a hip bleed3:

1. When the client flexes the trunk, severe pain is produced in the presence of iliopsoas bleeding, whereas only mild pain is found with a hip hemorrhage.

2. When the hip is gently rotated in either direction, severe pain is experienced with a hip hemorrhage but is absent or mild with iliopsoas bleeding.

Over time, the following complications may occur:

• Vascular compression causing localized ischemia and necrosis

• Replacement of muscle fibers by nonelastic fibrotic tissue causing shortened muscles and thus producing joint contractures

• Peripheral nerve lesions from compression of a nerve that travels in the same compartment as the hematoma, most commonly affecting the femoral, ulnar, and median nerves

Physician Referral

Understanding the components of a client’s past medical history that can affect hematopoiesis (production of blood cells) can provide the physical therapist with valuable insight into the client’s present symptoms, which are usually already well known to the attending physician.

For example, the effects of certain drugs, exposure to radiation, or recent cytotoxic cancer chemotherapy can affect bone marrow. Whenever uncertain, the physical therapist is encouraged to contact the physician by telephone for discussion and clarification of the client’s medical symptoms.

A history of excessive menses, a folate-poor diet, alcohol abuse, drug ingestion, family history of anemia, and family roots in geographic areas where RBC enzyme or hemoglobin abnormalities are prevalent represent some important findings. The presence of any one or more of these factors should alert the physical therapist to the need for medical referral when the client is not already under the care of a physician or when new signs or symptoms develop.

In addition, exercise for anemic clients must be instituted with extreme caution and should first be approved by the client’s physician. Clients with undiagnosed thrombocytopenia need immediate medical referral. The physical therapist must be alert for obvious skin or mucous membrane symptoms of thrombocytopenia. The presence of severe bruising, hematomas, and multiple petechiae usually indicates a platelet count well below normal. With clients who have been diagnosed with hemophilia, medical referral should be made when any painful episode develops in the muscle(s) or joint(s). Pain usually occurs before any other evidence of bleeding. Any unexplained symptom may be a signal of bleeding.

Guidelines for Physician Referral

• Consultation with the physician may be necessary when establishing or progressing an exercise program for a client with known anemia

• New episodes of muscle or joint pain in a client with hemophilia; pain usually occurs before any other evidence of bleeding. Any unexplained symptom(s) may be a signal of bleeding; coughing up blood in this population group must be reported to the physician

Clues to Screening for Hematologic Disease

• These clues will help the therapist in the decision-making process:

• Previous history (delayed effects) or current administration of chemotherapy or radiation therapy

• Chronic or long-term use of aspirin or other NSAIDs (drug-induced platelet reduction)

• Spontaneous bleeding of any kind (e.g., nosebleed, vaginal/menstrual bleeding, blood in the urine or stool, bleeding gums, easy bruising, hemarthrosis), especially with a previous history of hemophilia

• Recent major surgery or previous transplantation

• Rapid onset of dyspnea, chest pain, weakness, and fatigue with palpitations associated with recent significant change in altitude

• Observed changes in the hands and fingernail beds (see Table 5-1 and Fig. 4-30)

1. If rapid onset of anemia occurs after major surgery, which of the following symptom patterns might develop?

a. Continuous oozing of blood from the surgical site

2. Chronic GI blood loss sometimes associated with use of NSAIDs can result in which of the following problems?

3. Under what circumstances would you consider asking a client about a recent change in altitude or elevation?

4. Preoperatively, clients cannot take aspirin or antiinflammatory medications because these:

5. Skin color and nail bed changes may be observed in the client with:

a. Thrombocytopenia resulting from chemotherapy

b. Pernicious anemia resulting from Vitamin B12 deficiency

6. In the case of a client with hemarthrosis associated with hemophilia, what physical therapy intervention would be contraindicated?

7. Bleeding under the skin, nosebleeds, bleeding gums, and black stools require medical evaluation as these may be indications of:

8. Describe the two tests used to distinguish an iliopsoas bleed from a joint bleed.

9. What is the significance of nadir?

10. When exercising a client with known anemia, what two measures can be used as guidelines for frequency, intensity, and duration of the program?

References

1. Bushnell, BD. Perioperative medical comorbidities in the orthopaedic patient. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:216–227.

2. Hillman, R. Hematology in clinical practice, ed 5. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011.

3. Hoffman, R. Hematology: basic principles and practice, ed 5. Philadelphia: Churchill-Livingstone; 2008.

4. Wehbi, M. Acute gastritis. eMedicine Specialties—Gastroenterology. Updated Jan. 12, 2011. Available on-line at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/175909-overview. [Accessed January 26, 2011].

5. Abeloff, M. Abeloff’s clinical oncology, ed 4. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

6. Holcomb, S. Anemia: pointing the way to a deeper problem. Nursing 2001. 2001;31(7):36–42.

7. Goodman, CC, Fuller, K. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3. St Louis: WB Saunders; 2009.

8. Merriman, NA. Hip fracture risk in patients with a diagnosis of pernicious anemia. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(4):1330–1337.

9. Sproule, BJ. Cardiopulmonary physiological responses to heavy exercise in patients with anemia. J Clin Invest. 1960;39(2):378–388.

10. Callahan, L, Woods, K, et al. Cardiopulmonary responses to exercise in women with sickle cell anemia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(9):1309–1316.

11. Goodman, C, Helgeson, K. Exercise prescription for medical conditions: handbook for physical therapists. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2011.

12. Lombardi, G, Rizzi, E, et al. Epidemiology of anemia in older patients with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(6):740–741.

13. Mackenzie C: Hip fracture in the elderly, Best practice of medicine, Merck Medicus, Thomson Micromedex, March 2002.

14. Parker, MJ. Iron supplementation for anemia after hip fracture surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:265–269.

15. Saini, KS. Polycythemia vera-associated pruritus and its management. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40(9):828–834.

16. Rees, DC. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376(9757):2018–2031.

17. Abbas, MBBS, Lichtman, AH. Basic immunology updated edition: functions and disorders of the immune system, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2011.

18. Krishnan, K. Thrombocytosis, Secondary. eMedicine Specialities—Hematology. Updated Oct. 4, 2009. Available on-line at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/206811-overview. [Accessed January 26, 2010].

19. Inoue, S. Thrombocytosis. eMedicine Specialties—Pediatrics/Hematology. Updated April 19, 2010. Available on-line at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/959378-overview. [Accessed January 26, 2010].

20. Agaliotis, DP. Hemophilia. eMedicine Specialties—Coagulation, Hemostasis, and Disorders. Updated November 22, 2010 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/210104-overview.

21. Kumar, V. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease: professional edition, ed 8. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2009.

22. Kliegman, RM. Nelson textbook of pediatrics, ed 18. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007.

Key Points to Remember

Key Points to Remember