Screening for Gastrointestinal Disease

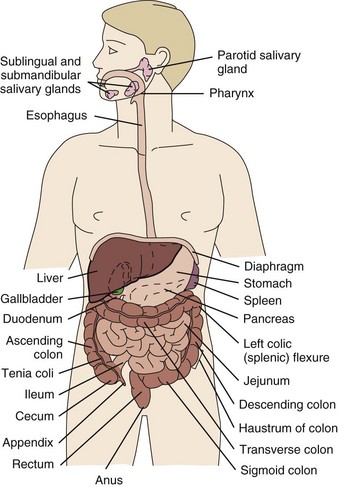

A great deal of new understanding of the enteric system and its relationship to other systems has been discovered over the last decade. For example, it is now known that the lining of the digestive tract from the esophagus through the large intestine (Fig. 8-1) is lined with cells that contain neuropeptides and their receptors. These substances, produced by nerve cells, are a key to the mind-body connection that contributes to the physical manifestation of emotions.1,2

Fig. 8-1 Organs of the digestive system; see also Fig. 9-1. (From Hall JE: Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2010, WB Saunders.)

In addition to the classic hormonal and neural negative feedback loops, there are direct actions of gut hormones on the dorsal vagal complex. The person experiencing a “gut reaction” or “gut feeling” may indeed be experiencing the direct effects of gut peptides on brain function.3

The association between the enteric system, the immune system, and the brain (now a part of the research referred to as psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) has been clearly established and forms an integral part of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms associated with immune disorders such as fibromyalgia, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and others.

Researchers estimate that more than two thirds of all immune activity occurs in the gut. There are more T cells in the intestinal epithelium than in all other body tissues combined. The gamma delta T cells form the forefront of the immune defense mechanism. They act as an early warning system in the cells lining the intestines, which are heavily exposed to microorganisms and toxins.4,5 In some people, the wall of the gut seems to have been breached, either because the network of intestinal cells develops increased permeability (a syndrome referred to as “leaky gut”) or perhaps because bacteria and yeast overwhelm it and migrate into the bloodstream.

Allowing undigested food or bacteria into the bloodstream sets in motion a chain of events as the immune system reacts. The body responds as if to an illness and expresses it in a number of ways such as a rash, diarrhea, GI upset, joint pain, migraines, and headache. The exact cause for these microscopic breaches remains unknown, but food allergies, too much aspirin or ibuprofen, certain antibiotics, excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, or parasitic infections may be implicated.

All of these associations and new findings support the need for the therapist to assess carefully the possibility of GI symptoms present but unreported. This is especially important when considering the fact that GI tract problems can sometimes imitate musculoskeletal dysfunction.

GI disorders can refer pain to the sternal region, shoulder and neck, scapular region, mid-back, lower back, hip, pelvis, and sacrum. This pain can mimic primary musculoskeletal or neuromuscular dysfunction, causing confusion for the physical therapist or for the physician assessing the client’s chief complaint.

Although these neuromusculoskeletal symptoms can occur alone and far from the actual site of the disorder, the client usually has other systemic signs and symptoms associated with GI disorders that should give the therapist who does a thorough investigation grounds for suspicion.

A careful interview to screen for systemic illness should include a few important questions concerning the client’s history, prescribed medications, and the presence of any associated signs or symptoms that would immediately alert the therapist about the need for medical follow-up. The most common intraabdominal diseases that refer pain to the musculoskeletal system are those that involve ulceration or infection of the mucosal lining. Drug-induced GI symptoms can also occur with delayed reactions as much as 6 or 8 weeks after exposure to the medication. The most common occurrences are antibiotic colitis; nausea, vomiting, and anorexia from digitalis toxicity; and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced ulcers.

Signs and Symptoms of Gastrointestinal Disorders

Any disruption of the digestive system can create symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, pain, diarrhea, and constipation. The bowel is susceptible to altered patterns of normal motility caused by food, alcohol, caffeine, drugs, physical and emotional stress, and lifestyle (e.g., lack of regular exercise, tobacco use). GI effects of chemotherapy include nausea and vomiting, anorexia, taste alteration, weight loss, oral mucositis, diarrhea, and constipation.

Symptoms, including pain, can be related to various GI organ disturbances and differ in character, depending on the affected organ. The most clinically meaningful GI symptoms reported in a physical therapy practice include

• GI bleeding (emesis, melena, red blood)

• Epigastric pain with radiation to the back

• Early satiety with weight loss

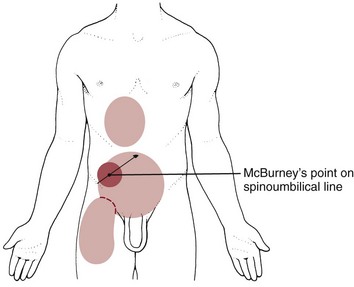

• Tenderness over McBurney’s point (see Appendicitis this chapter)

Abdominal Pain

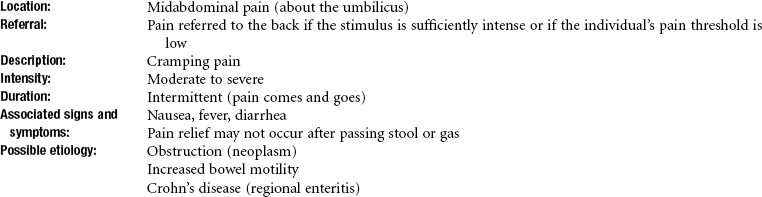

As we enter into this next discussion on primary and referred abdominal pain patterns, be aware that each pain pattern has listed with it both the sympathetic nerve distribution to the viscera (i.e., autonomic nervous system innervation of the structure) and the anatomic location of radiating or referred pain from the viscera or GI segment involved in the primary pain patterns.

Whenever possible, labels are used to differentiate between sympathetic nerve innervations of the viscera and anatomic locations of the pain. For example, the small intestine (viscera) is innervated by T9 to T11 but refers (somatic) pain to the L3 to L4 (anatomic) lumbar spine.

Primary Gastrointestinal Visceral Pain Patterns

Visceral pain (internal organs) occurs in the midline because the digestive organs arise embryologically in the midline and receive sensory afferents from both sides of the spinal cord. The site of pain generally corresponds to dermatomes from which the visceral organs receive their innervation (see Fig. 3-3). Pain is not well localized because innervation of the viscera is multisegmental over up to eight segments of the spinal cord with fewer nerve endings than other sensitive organs.

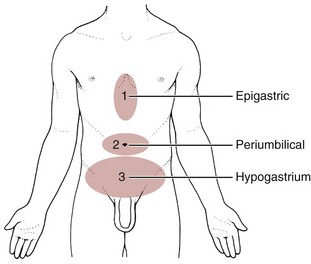

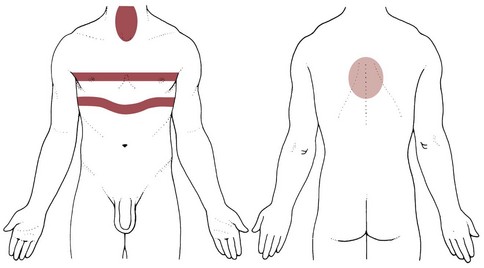

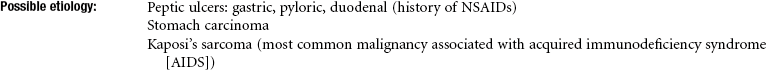

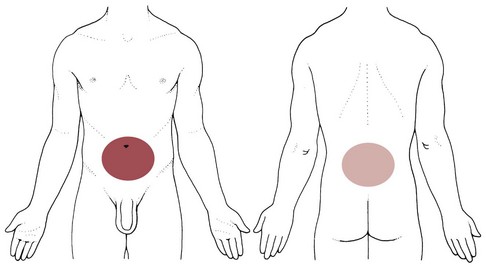

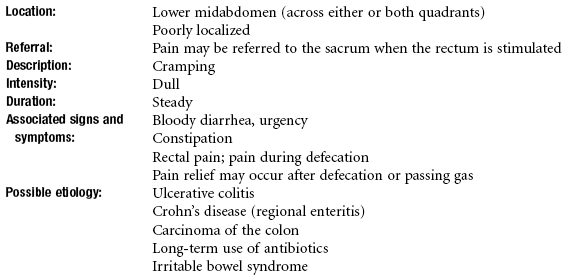

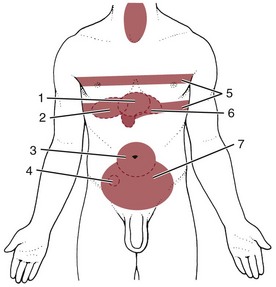

The most common primary pain patterns associated with organs of the GI tract are depicted in Fig. 8-2. Reasons for abdominal pain fall into three broad categories: inflammation, organ distention (tension pain), and necrosis (ischemic pain). The underlying cause can be life-threatening, requiring a quick assessment and fast referral.

Fig. 8-2 Visceral pain. 1, The epigastric region from the heart, esophagus, stomach, duodenum, gallbladder, liver, or pancreas and corresponding to T3 to T5 sympathetic nerve distribution; 2, the periumbilical region from the pancreas, small intestine, appendix, or proximal colon (T9 to T11 sympathetic nerve distribution; the umbilicus is level with the disk located between the L3 and L4 vertebral bodies in the adult who is not overweight); and 3, the lower midabdominal or hypogastrium region from the large intestine, colon, bladder, or uterus (T10 to L2 sympathetic nerve distribution).

Pain in the epigastric region occurs anywhere from the midsternum to the xiphoid process from the heart, esophagus, stomach, duodenum, gallbladder, liver, and other mediastinal organs corresponding to the T3 to T5 sympathetic nerve distribution. The client may report the pain radiates around the ribs or straight through the chest to the thoracic spine at the T3 to T6 or T7 anatomic levels.

Pain in the periumbilical region (T9 to T11 nerve distribution) occurs with impairment of the small intestine (see Fig. 8-15), pancreas, and appendix. Primary pain in the periumbilical region usually sends the client to a physician. However, pain around the umbilicus may be accompanied by low back pain. In the healthy adult who is not obese and does not have a protruding abdomen, the umbilicus is level with the disk located anatomically between the L3 and L4 vertebral bodies.

The physical therapist is more likely to see a client with anterior abdominal and low back pain at the same level but with alternating presentation. In other words, first the client experiences periumbilical pain with or without associated GI signs and symptoms, then the painful episode resolves. Later, the client develops low back pain with or without GI symptoms but does not realize there is a link between these painful episodes. It is at this point the client presents in a physical therapy practice.

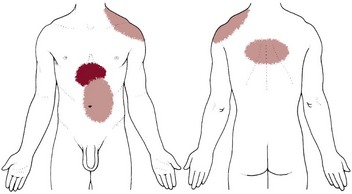

Pain in the lower abdominal region (hypogastrium) from the large intestine and/or colon may be mistaken for bladder or uterine pain (and vice versa) by its suprapubic location. Referred pain at the same anatomic level posteriorly corresponds to the sacrum (see Fig. 8-16). The large intestine and colon are innervated by T10 to L2, depending on the location (e.g., ascending, transverse, descending colon).

The abdominal viscera are ordinarily insensitive to many stimuli, such as cutting, tearing, or crushing, that when applied to the skin evokes severe pain. Visceral pain fibers are sensitive only to stretching or tension in the wall of the gut from neoplasm, distention, or forceful muscular contractions secondary to bowel obstruction or spasm.

Tension pain can occur as a result of bowel obstruction; constipation; and pus, fluid, or blood accumulation from infection or other causes. The rate that tension develops must be rapid enough to produce pain; gradual distention, such as with malignant obstruction, may be painless unless ulceration occurs. Rapid, peristalsis forces of the bowel trying to eliminate irritating substances can cause tension pain described as “colicky” pain. Individuals with tension pain have trouble finding a comfortable position. They will constantly shift positions to try and find a comfortable position.

Visceral organs of the GI tract (particularly hollow organs such as the intestines) respond to stretching and distention as pain, more so than typical tissue injury caused by cutting or crushing. Because of similar innervation, it is often difficult to distinguish pain associated with the heart from pain caused by an esophageal disorder.

One difference between visceral organ pain and pain from the parietal peritoneum is that the parietal peritoneum is innervated by nerves that travel with the somatic nerves, providing a more precise location of pain. This is noted with acute appendicitis, when early, vague pain (from inflammation of the appendix) is replaced by more localized pain at McBurney’s point once the inflammation involves the parietal peritoneum.

Inflammatory pain arising from the visceral or parietal peritoneum (e.g., acute appendicitis) is described as steady, deep, and boring. It can be poorly localized as when the visceral peritoneum is involved or more localized with parietal peritoneum involvement. Individuals with inflammatory pain seek a quiet position (often with the knees bent or in a curled up/fetal position) without movement.

Ischemia (deficiency of blood) may produce visceral pain by increasing the concentration of tissue metabolites in the region of the sensory nerve. Pain associated with ischemia is steady pain, whether this ischemia is secondary to vascular disease or due to obstruction causing strangulation of bowel tissue. The pain is sudden in onset and extremely intense. It progresses in severity and is not relieved by analgesics.

Additionally, although the viscera experience pain, the visceral peritoneum (membrane enveloping organs) is not sensitive to cutting. Except in the presence of widespread inflammation or ischemia, it is possible to have extensive disease without pain until the disease progresses enough to involve the parietal peritoneum.

Visceral pain is usually described as deep aching, boring, gnawing, vague burning, or deep grinding as opposed to the sharp, pricking, and knifelike qualities of cutaneous pain. When referred to the somatic regions of the low back, hip, or shoulder, the sensation is vague and poorly localized because visceral afferents provide input over multiple segments of the spinal cord. As mentioned, afferents from different abdominal locations converge on the same dorsal nerve roots, which may be shared with the more precisely developed somatic sensory pathways.

Referred Gastrointestinal Pain Patterns

Sometimes visceral pain from a digestive organ is felt in a location remote from the usual anterior midline presentation. The referred pain site still lies within the dermatomes of the dorsal nerve roots serving the painful viscera. Referred pain is often more intense and localized than typical visceral pain. Afferent nerve impulses transmit pain from the esophagus to the spinal cord by sympathetic nerves from T5 to T10. Integration of the autonomic and somatic systems occurs through the vagus and the phrenic nerves. There can be referred pain from the esophagus to the mid-back and referred pain from the mid-back to the esophagus. For example, esophageal dysfunction can present as anterior neck pain or mid-thoracic spine pain and disk disease of the mid-thoracic spine can masquerade as esophageal pain.

Client history and the presence or absence of associated signs and symptoms will help guide the therapist. For example, a client with mid-back pain from esophageal dysfunction will not likely report numbness and tingling in the upper extremities or bowel and bladder changes such as you might see with disk disease. Likewise, disk involvement with referred pain to the esophagus will not cause melena or symptoms associated with meals.

Visceral afferent nerves from the liver, respiratory diaphragm, and pericardium are derived from C3 to C5 sympathetics and reach the central nervous system (CNS) via the phrenic nerve (see Fig. 3-3). The visceral pain associated with these structures is referred to the corresponding somatic area (i.e., the shoulder).

Afferent nerves from the gallbladder, stomach, pancreas, and small intestine travel through the celiac plexus (network of ganglia and nerves supplying the abdominal viscera) and the greater splanchnic nerves and enter the spinal cord from T6 to T9. Referred visceral pain from these visceral structures may be perceived in the mid-back and scapular regions.

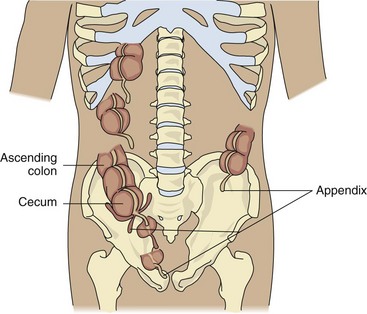

Afferent stimuli from the colon, appendix, and pelvic viscera enter the 10th and 11th thoracic segments through the mesenteric plexus and lesser splanchnic nerves. Finally, the sigmoid colon, rectum, ureters, and testes are innervated by fibers that reach T11 to L1 segments through the lower splanchnic nerve and through the pelvic splanchnic nerves from S2 to S4. Referred pain may be perceived in the pelvis, flank, low back, or sacrum (Case Example 8-1).

Hyperesthesia (excessive sensibility to sensory stimuli) of skin and hyperalgesia (excessive sensibility to painful stimuli) of muscle may develop in the referred pain distribution. As mentioned in Chapter 3, in the early stage of visceral disease, sympathetic reflexes arising from afferent impulses of the internal viscera can be expressed first as sensory, motor, and/or trophic changes in the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and/or muscles. The client may present with itching, dysesthesia, skin temperature changes, perspiration, or dry skin.

The viscera do not perceive pain, but the sensory side is trying to get the message out that something is wrong by creating sympathetic sudomotor changes. When the afferent visceral pain stimuli are intense enough, discharges at synapses within the spinal cord cause this reflex phenomenon, usually transmitted by peripheral nerves of the same spinal segment(s). Thus the sudomotor changes occur as an automatic reflex along the distribution of the somatic nerve.

Remember from our discussion of viscerogenic pain patterns in Chapter 3 that any structure touching the respiratory diaphragm can refer pain to the shoulder, usually to the ipsilateral shoulder, depending on where the direct pressure occurs. Anyone with upper back or shoulder pain and symptoms should be asked a few general screening questions about the presence of GI symptoms.

Referred pain to the musculoskeletal system can occur alone, without accompanying visceral pain, but usually visceral pain (or other symptoms) precedes the development of referred pain. The therapist will find that the client does not connect the two sets of symptoms or fails to report abdominal pain and GI symptoms when experiencing a painful shoulder or low back, thinking these are two separate problems. For a more complete discussion of the mechanisms behind viscerogenic referred pain patterns, see Chapter 3.

Most of what has been presented here has dealt with the sensory side of the clinical presentation. There can be motor effects of GI dysfunction, too. For example, contraction, guarding, and splinting of the rectus abdominis and muscles above the umbilicus can occur with dysfunction of the stomach, gallbladder, liver, pylorus, or respiratory diaphragm. Impairment of the ileum, jejunum, appendix, cecum, colon, and rectum are more likely to result in muscle spasm of the rectus abdominis below the umbilicus.6

At the same time, impairment of these GI structures can cause muscle dysfunction in the back (thoracic and lumbar spine) with loss of motion of the involved spinal segments. The clinical picture is one that is easily confused with primary pathology of the spinal segment.6 Once again, the history and associated signs and symptoms help the therapist sort through the clinical presentation to reach a differential diagnosis. A thorough screening process is essential in such cases.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) is the sensation of food catching or sticking in the esophagus. This sensation may occur (initially) just with coarse, dry foods and may eventually progress to include anything swallowed, even thin liquids and saliva. Dysphagia may be caused by achalasia, a process by which the circular and longitudinal muscular fibers of the lower esophageal sphincter fail to relax, producing an esophageal obstruction.

Other possible GI causes of dysphagia include peptic esophagitis (inflammation of the esophagus) with stricture (narrowing), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and neoplasm (Case Example 8-2). Dysphagia may be a symptom of many other disorders unrelated to GI disease (e.g., stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease). Certain types of drugs, including antidepressants, antihypertensives, and asthma drugs, can make swallowing difficult.

The presence of dysphagia requires prompt attention by the physician. Medical intervention is based on a subsequent endoscopic examination.

Odynophagia

Odynophagia, or pain during swallowing, can be caused by esophagitis or esophageal spasm. Esophagitis may occur secondary to GERD, the herpes simplex virus, or fungus caused by the prolonged use of strong antibiotics. Pain after eating may occur with esophagitis or may be associated with coronary ischemia.

To differentiate esophagitis from coronary ischemia: upright positioning relieves esophagitis pain, whereas cardiac pain is relieved by nitroglycerin or by supine positioning. Both conditions require medical attention.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Occult (hidden) GI bleeding can appear as mid-thoracic back pain with radiation to the right upper quadrant. Bleeding may not be obvious; serial Hemoccult tests and laboratory tests (checking for anemia and iron deficiency) are needed. A medical doctor should evaluate any type of bleeding. Ask about the presence of other signs such as blood in the vomit or stools (Box 8-1). Coffee ground emesis (vomit) may indicate a perforated peptic or duodenal ulcer.

Bloody diarrhea may accompany other signs of ulcerative colitis. Diarrhea and ulcerative colitis are discussed in greater depth separately in this chapter. Bright red blood usually represents pathology close to the rectum or anus and may be an indication of rectal fissures (e.g., history of anal intercourse) or hemorrhoids but can also occur as a result of colorectal cancer.

Melena, or black, tarry stool, occurs as a result of large quantities of blood in the stool. When asked about changes in bowel function, clients may describe black, tarry stools that have an unusual, noxious odor. The odor is caused by the presence of blood, and the black color arises as the digestive acids in the bowel oxidize red blood cells (e.g., bleeding esophageal varices, stomach or duodenal ulceration). Melena is very sticky and does not clean well.

It may be necessary to ask about bowel smears on the undergarments or difficulty getting wiped clean after a bowel movement. The following series may guide the therapist in this area:

Esophageal varices are dilated blood vessels, usually secondary to alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver. Blood that would normally be pumped back to the heart must bypass the damaged liver. The blood then “backs up” through the esophagus. Ruptured esophageal varices are an emergent, life-threatening condition. Vascular abnormalities of the stomach causing bleeding may include ulcers.

The client should be asked about the presence of any blood in the stool to determine whether it is melenic (from the upper GI tract; ask about a history of NSAID use) or bright red (from the distal colon or rectum). Bleeding from internal or external hemorrhoids (enlarged veins inside or outside the rectum), rectal fissures, or colorectal carcinoma can cause bright red blood in the stools. Rectal bleeding from anal lesions or fissures can occur in the homosexual population who are sexually active. Women engaging in anal intercourse can also be affected. A brief sexual history may be indicated in some cases.

Reddish or mahogany-colored stools can occur from eating certain foods, such as beets, or significant amounts of red food coloring but can also represent bleeding in the lower GI/colon. Medications that contain bismuth (e.g., Kaopectate, Pepto-Bismol, Bismatrol, Pink Bismuth) can cause darkened or black stools and the client’s tongue may also appear black.

Clients who have received pelvic radiation for gynecologic, rectal, or prostate cancers have an increased risk for radiation proctitis, which can cause subsequent (delayed) rectal bleeding episodes. Be sure and ask about a past history of cancer and radiation treatment.

Epigastric Pain with Radiation

Epigastric pain perceived as intense or sharp pain behind the breastbone with radiation to the back may occur secondary to long-standing ulcers. For example, the client may be aware of an ulcer but does not relate the back pain to the ulcer. Close questioning related to GI symptoms can provide the therapist with knowledge of underlying systemic disease processes.

Anyone with epigastric pain accompanied by a burning sensation that begins at the xiphoid process and radiates up toward the neck and throat may be experiencing heartburn. Other common symptoms may include a bitter or sour taste in the back of the throat, abdominal bloating, gas, and general abdominal discomfort. Heartburn is often associated with GERD. It can be confused with angina or heart attack when accompanied by chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath (SOB). A physician must evaluate and diagnose the cause of epigastric pain or heartburn.

A screening interview and evaluation is especially helpful when clients have neglected medical treatment for so long that epigastric back pain may in turn have created biomechanical changes in muscular contractions and spinal movement. These changes eventually create pain of a biomechanical nature.7 The client then presents with enough true musculoskeletal findings such that a diagnosis of back dysfunction can be supported. However, the symptoms may be associated with a systemic problem. A good medical history can be a valuable tool in revealing the actual cause of the back pain.

Symptoms Affected by Food

Clients may or may not be able to relate pain to meals. Pain associated with gastric ulcers (located more proximally in the GI tract) may begin within 30 to 90 minutes after eating, whereas pain associated with duodenal or pyloric ulcers (located distally beyond the stomach) may occur 2 to 4 hours after meals (i.e., between meals). Alternatively stated, food is not likely to relieve the pain of a gastric ulcer, but it may relieve the symptoms of a duodenal ulcer.

The client with a duodenal ulcer or cancer-related pain may report pain during the night between midnight and 3:00 am. Ulcer pain may be differentiated from the nocturnal pain associated with cancer by its intensity (7 or higher on a scale from 0 to 10) and duration (constant). More specifically, the gnawing pain of an ulcer may be relieved by eating, but the intense, boring pain associated with cancer is not relieved by any measures.

Ask the client with nighttime shoulder, neck, or back pain to eat something and assess the effect of food on these symptoms. Anyone whose musculoskeletal pain is altered (increased or decreased) or eliminated by food should be screened more thoroughly and referred for further medical evaluation when appropriate. Anyone with a previous history of cancer and nighttime pain must also be evaluated more closely. This is true even if eating has no effect on the client’s symptoms.

Early Satiety

Early satiety occurs when the client feels hungry, takes one or two bites of food, and feels full. The sensation of being full is out of proportion with the time of the previous meal and the initial degree of hunger experienced. This can be a symptom of obstruction, stomach cancer, gastroparesis (slowing down of stomach emptying), peptic ulcer disease, and other tumors. Vertebral compression fractures can occur from a variety of disorders including osteoporosis and can result in severe spinal deformity. This deformity, along with severe back pain, can cause early satiety resulting in malnutrition.8

Constipation

Constipation is defined clinically as being a condition of prolonged retention of fecal content in the GI tract resulting from decreased motility of the colon or difficulty in expelling stool.

The Rome III Diagnostic criteria for functional constipation defines this condition as hard, lumpy stools; stools that are difficult to expel; infrequent stools (less than three per week); or a feeling of incomplete evacuation after defecation and general discomfort.9,10 Constipated clients with tender psoas trigger points (TrPs) may report anterior hip, groin, or thigh pain when the fecal bolus presses against the TrPs.11

Intractable constipation is called obstipation and can result in a fecal impaction that must be removed. Back pain may be the overriding symptom of obstipation, especially in older adults who do not have regular bowel movements or who cannot remember the last bowel movement was several weeks ago (Case Example 8-3).

Keep in mind the individual who has low back pain with constipation could also be manifesting symptoms of pelvic floor muscle overactivity or spasm. In such cases, pelvic floor assessment should be a part of the screening exam. Consultation with a physical therapist skilled in this area should be considered if the primary care therapist is unable to perform this examination.

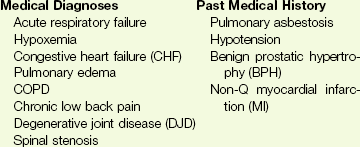

Changes in bowel habit may be a response to many other factors such as diet (decreased fluid and bulk intake), smoking, side effects of medication (especially constipation associated with opioids), acute or chronic diseases of the digestive system, extraabdominal diseases, personality, mood (depression), emotional stress, inactivity, prolonged bed rest, and lack of exercise (Table 8-1). Commonly implicated medications include narcotics, aluminum- or calcium-containing antacids (e.g., Alu-Tab, Basaljel, Tums, Rolaids), anticholinergics, tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, calcium channel blockers, and iron salts.

Diets that are high in refined sugars and low in fiber discourage bowel activity. Transit time of the alimentary bolus from the mouth to the anus is influenced mainly by dietary fiber and is decreased with increased fiber intake. Additionally, motility can be decreased by emotional stress that has been correlated with personality. Constipation associated with severe depression can be improved by exercise.

People with low back pain may develop constipation as a result of muscle guarding and splinting that causes reduced bowel motility. Pressure on sacral nerves from stored fecal content may cause an aching discomfort in the sacrum, buttocks, or thighs (Case Example 8-4).

Because there are many specific organic causes of constipation, it is a symptom that may require further medical evaluation. It is considered a red flag symptom when clients with unexplained constipation have sudden and unaccountable changes in bowel habits or blood in the stools.

Diarrhea

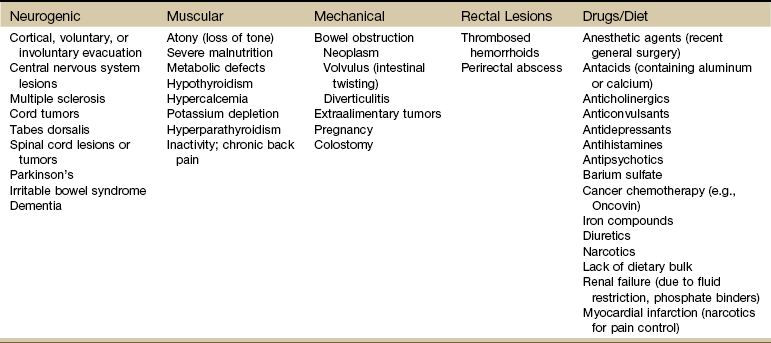

Diarrhea, by definition, is an abnormal increase in stool frequency and liquidity. This may be accompanied by urgency, perianal discomfort, and fecal incontinence. The causes of diarrhea vary widely from one person to another, but food, alcohol, use of laxatives and other drugs, medication side effects, and travel may contribute to the development of diarrhea (Table 8-2).

Acute diarrhea, especially when associated with fever, cramps, and blood or pus in the stool, can accompany invasive enteric infection. Chronic diarrhea associated with weight loss is more likely to indicate neoplastic or inflammatory bowel disease. Extraintestinal manifestations such as arthritis or skin or eye lesions are often present in inflammatory bowel disease. Any of these combinations of symptoms must be reported to the physician.

Drug-induced diarrhea is associated most commonly with antibiotics. Diarrhea may occur as a direct result of antibiotic use and the GI symptom resolves when the drug is discontinued. Symptoms may also develop 6 to 8 weeks after first ingestion of an antibiotic. A more serious, less frequent antibiotic-induced colitis with severe diarrhea is caused by Clostridium difficile.

This anaerobic bacterium colonizes the colon of 5% of healthy adults and over 20% of hospitalized patients. Clients receiving enteral (tube) feedings are at higher risk for acquisition of C. difficile and associated severe diarrhea. C. difficile is the major cause of diarrhea in patients hospitalized for more than 3 days. It is spread in an oral-fecal manner and is readily transmitted from patient to patient by hospital personnel. Fastidious handwashing, use of gloves, and extremely careful cleaning of bathroom, bed linen, and associated items are helpful in decreasing transmission.12

Athletes using creatine supplements to enhance power and strength in performance may experience minor GI symptoms. Muscle cramps, diarrhea, loss of appetite, weight gain, and dizziness occur in about 8% of the individuals taking these supplements. Therapists working with athletes should keep this in mind when hearing reports of GI distress. Many sports players do not even know how much creatine they are taking or are taking more than the recommended dose. Players as young as 13 years old have reported using creatine supplements.12a,13 The use of creatine for individuals under the age of 18 is not recommended; safety and efficacy of creatine has not been established in adolescents.14

For the client describing chronic diarrhea, it may be necessary to probe further about the use of laxatives as a possible contributor to this condition. Laxative abuse contributes to the production of diarrhea and begins a vicious cycle as chronic laxative users experience excessive secretion of aldosterone and resultant edema when they attempt to stop using laxatives. This edema and increased weight forces the person to continue to rely on laxatives. The abuse of laxatives is common in the eating disorder populations (e.g., anorexia, bulimia); affected persons may ingest up to 100 laxatives at a time.

Questions about laxative use can be asked tactfully during the Core Interview (see Chapter 2) when asking about medications, including over-the-counter (OTC) drugs such as laxatives. Encourage the client to discuss bowel management without drugs at the next appointment with the physician.

Fecal Incontinence

Fecal incontinence may be described as an inability to control evacuation of stool and is associated with a sense of urgency, diarrhea, and abdominal cramping. Causes include partial obstruction of the rectum (cancer), colitis, and radiation therapy, especially in the case of women treated for cervical or uterine cancer. The radiation may cause trauma to the rectum that results in incontinence and diarrhea. Anal distortion secondary to traumatic childbirth, hemorrhoids, and hemorrhoidal surgery may also cause fecal incontinence.

Arthralgia

The relationship between “gut” inflammation and joint inflammation is well known but not fully understood. Many inflammatory GI conditions have an arthritic component affecting the joints. For example, inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) is often accompanied by rheumatic manifestations; peripheral joint arthritis and spondylitis with sacroiliitis are the most common of these manifestations.15,16 Sacroiliac (SI) disease without inflammation has been documented as a primary cause of lower abdominal or inguinal pain.17

There may be a genetic component between inflammatory bowel disease and ankylosing spondylitis.18 The relationship between intestinal problems and joint involvement may also be explained by some type of “interface” between the bowel and the articular surface of joints.19,20 It is hypothesized that an antigen crosses the gut mucosa and enters the joint, which sets up an immunologic response. Arthralgia with synovitis and immune-mediated joint disease may occur as a result of this immunologic response.19 It is likely that an impaired antibacterial host defense and an uncontrolled proinflammatory response of the innate immune system are at fault.21

Joint arthralgia associated with GI infection is usually asymmetric, migratory, and oligoarticular (affecting only one or two joints). This type of joint involvement is termed reactive arthritis when triggered by microbial infection such as C. difficile from the GI (and sometimes genitourinary or respiratory) tract. Other accompanying symptoms may include fever, malaise, skin rash or other skin lesions, nail bed changes (nails separate from the nail beds and become thin and discolored), iritis, or conjunctivitis.

The bowel and joint symptoms may or may not occur at the same time. Usually, this type of arthralgia is preceded 1 to 3 weeks by diarrhea, urethritis, regional enteritis (Crohn’s disease), or other bacterial infection. The knees, ankles, shoulders, wrists, elbows, and small joints of the hands and feet (listed in order of decreasing frequency) are the peripheral joints affected most often.22

A large knee effusion is a common presentation, but some clients have joint pain with minimal or no signs of inflammation. Muscle atrophy occurs when a chronic condition is present; in which case, there will be a history of previous GI and joint involvement. Stiffness, pain, tenderness, and reduced range of motion may be present, but with proper medical intervention, there is no permanent deformity.

Spondylitis with sacroiliitis may present as low back pain and morning stiffness that improves with activity and restriction of chest and spinal movement. Radiographic findings are consistent with those of classic ankylosing spondylitis with bilateral SI joint involvement and bony erosion and sclerosis of the symphysis pubis, ischial tuberosities, and iliac crests. Ultimately, “bamboo spine” (see Fig. 12-4) will result.

Inflammation involving the sites of bony insertion of tendons and ligaments termed enthesitis is a classic sign of reactive arthritis. Tendon sheaths and bursae may also become inflamed. Ligaments along the spine and SI joints and around the ankle and midfoot may also show evidence of inflammation.

Heel pain is a frequent complaint, with swelling and tenderness located either posteriorly at the Achilles tendon insertion site, or inferiorly where the plantar fascia attaches to the calcaneus. Plantar fasciitis is common. Enthesopathy can also occur around the knee, ischial tuberosities, greater femoral trochanter, and costovertebral and manubriosternal joints.23

For a more complete discussion of joint pain and how to evaluate joint pain, see Chapter 3. A list of screening questions for joint pain is also reproduced in the Appendix as a quick reference in clinical practice.

Shoulder Pain

Pain in the left shoulder (Kehr’s sign: pain with pressure placed on the upper abdomen; Danforth sign: shoulder pain with inspiration) can occur as a result of free air following laparoscopic surgery or blood in the abdominal cavity, usually from a ruptured spleen or retroperitoneal bleeding causing distention. Retroperitoneum refers to a position external or posterior to the peritoneum, the serous membrane lining the abdominopelvic walls. Retroperitoneal organs refer to viscera that lie against the posterior body wall and are covered by peritoneum on the anterior surface only (e.g., thoracic portion of the esophagus, pancreas, duodenal cap, ascending and descending colon, rectum).

The screening interview may help the client recall any precipitating trauma or injury such as a sharp blow during an athletic event, a fall, or perhaps even a minor automobile accident causing pressure from the steering wheel. The client may not connect these seemingly unrelated events with the present shoulder pain.

Perforated duodenal or gastric ulcers can leak gastric juices on the posterior wall of the stomach that irritate the diaphragm referring pain to the shoulder; although the stomach is on the left side of the body, the referral pattern is usually to the right shoulder.

A ruptured ectopic pregnancy with retroperitoneal bleeding into the abdominal cavity can also present as low abdominal and/or shoulder pain. Usually there is a history of sexual activity and missed menses in a woman of reproductive age.

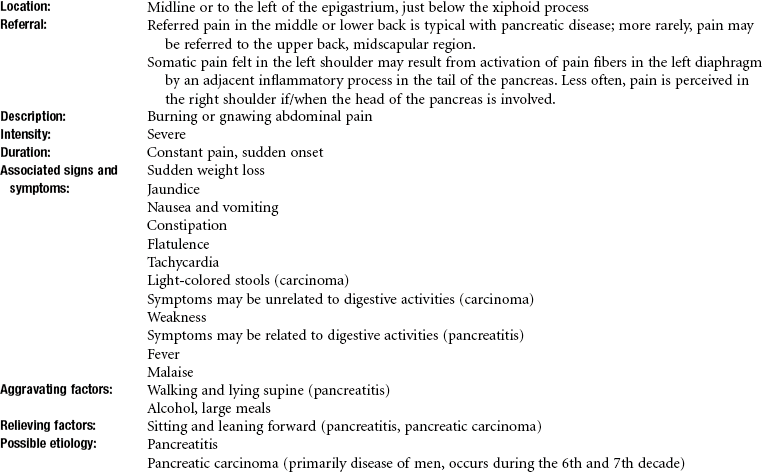

Pancreatic cancer can refer pain to the shoulder and is often missed as the cause. Fluid in the pleural space as a result of pancreatitis can present as shoulder pain. When the head of the pancreas is involved, the client could have right shoulder pain, but more often it manifests as mid-back or mid-thoracic pain sometimes lateralized from the spine on either side. When the tail of the pancreas is diseased, pain can be referred to the left shoulder (see Fig. 3-4). Pain may also occur in the right shoulder when blood is present in the abdominal cavity due to liver trauma (Case Example 8-5). Accumulation of blood in this area from a slow bleed of the spleen, liver, or stomach can produce bilateral shoulder pain.

Obturator or Psoas Abscess

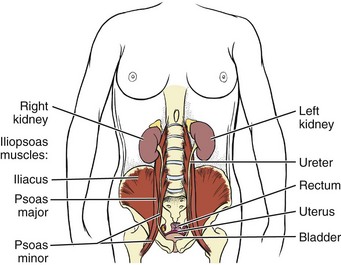

Abscess of the obturator or psoas muscle is a possible cause of lower abdominal pain, usually the consequence of spread of inflammation or infection from an adjacent structure. Since these muscles lie behind abdominal structures with no protective barrier, any infectious or inflammatory process affecting the abdominal or pelvic cavity can cause an obturator or psoas abscess (Figs. 8-3 and 8-4).

Fig. 8-3 The iliopsoas muscle is not separated from the abdominal or pelvic cavity. As this illustration shows, most of the viscera in the abdominal and pelvic cavities can come in contact with the iliopsoas muscle. Any infectious or inflammatory process present in either of these cavities can seed itself to the psoas muscle by direct extension.

Fig. 8-4 Right psoas abscess in a 17-year-old girl (arrow). (From Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases, Philadelphia, 2009, Churchill Livingstone.)

Psoas abscesses most commonly result from direct extension of intraabdominal infections such as diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and appendicitis (see also the discussion on McBurney’s point later in this chapter).24 Kidney infection or abscess can also cause psoas abscess. Staphylococcus aureus (staph infection) is the most common cause of psoas abscess secondary to vertebral osteomyelitis.

Peritonitis as a result of any infectious or inflammatory process can result in psoas abscess. Besides the diseases and conditions mentioned here, peritonitis can occur as a surgical complication. Look for a history of abdominal surgery of any kind, especially the anterior approach to spinal surgery for disk removal, spinal fusion, and insertion of a cage or artificial disk implant.25 In adult women, hematogenous psoas abscesses have been observed as a complication of spontaneous vaginal delivery.26,27

Regardless of the etiology, the abscess is usually confined to the psoas fascia but can spread to the hip, upper thigh, or buttock. The iliacus muscle in the iliac fossa joins with the lower portion of the psoas muscle. Osteomyelitis of the ilium or septic arthritis of the SI joint can penetrate the muscle sheath of either muscle, producing an abscess of either the iliacus or psoas portion of the muscle.28

In addition, abscesses of the pelvis, retroperitoneal area, and abdomen can spread bacteria or fungi to local vertebral areas, causing spinal infections such as pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. From the lumbar spine, abscess formation may track along the psoas muscle and into the buttock (piriformis fossa), the perianal region, the groin, and even the popliteal fossa.29

Clinical manifestations of a psoas or iliacus abscess include fever; night sweats; lower abdominal, pelvic, or back pain; or pain referred to the hip, medial thigh or groin (femoral triangle area), or knee. The right side is affected most often when associated with appendicitis. Both sides can be involved with generalized peritonitis but usually that person has a clear systemic presentation and seeks medical evaluation. It is the unusual cases that a therapist will see, making it necessary to know both the typical pain patterns associated with systemic disease, as well as the atypical presentations.

Antalgic gait may develop with a psoas abscess secondary to a reflex spasm pulling the leg into internal rotation and causing a functional hip flexion contracture. The affected individual may have pain with hip extension. Often a tender mass can be palpated in the groin. The therapist must assess for TrPs of the iliopsoas muscle. A psoas minor syndrome can be mistaken for appendicitis so be sure and assess for TrPs.11

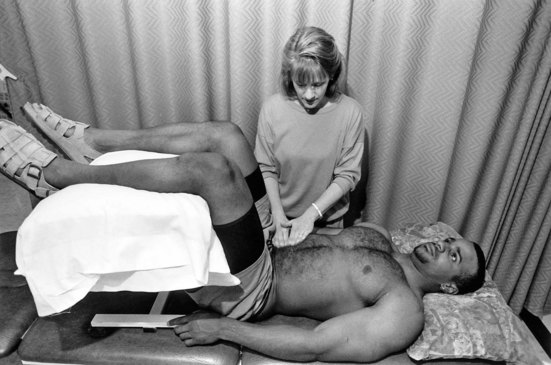

Four tests can be performed to assess the possibility of systemic origin of painful hip or thigh symptoms (Box 8-2). Gently pick up the client’s leg on the involved side and tap the heel. A painful expression and report of right lower quadrant pain may accompany peritoneal inflammation. If the client is willing and able, have him or her hop on one leg. The person with an inflamed peritoneum will clutch that side and be unable to complete the movement. The iliopsoas muscle test (Fig. 8-5) is performed when acute abdominal pain is a possible cause of hip or thigh pain. When an abscess forms on the iliopsoas muscle from an inflamed or perforated appendix or inflamed peritoneum, the iliopsoas muscle test causes pain felt in the right lower abdominal quadrant. (Pain and tenderness in the lower left side of the abdomen and pelvis may be caused by bowel perforation associated with diverticulitis, constipation, or obstipation [impaction] of the sigmoid, or appendicitis when the appendix is located on the left side of the midline.)

Fig. 8-5 Iliopsoas muscle test. In the supine position, have the client actively perform a straight leg raise; apply resistance to the distal thigh as the client tries to hold the leg up. Alternately, ask the client to turn onto his or her side. Extend the person’s uppermost leg at the hip. Increased abdominal, flank, or pelvic pain on either maneuver constitutes a positive sign, suggesting irritation of the psoas muscle by an inflamed appendix or peritoneum. Only a handful of studies have been done to validate the accuracy of this test for appendicitis/peritonitis. One systematic review reported sensitivity value at 0.16 and specificity as 0.95 with a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 2.38 (reported range: 1.21-4.67) and negative likelihood range (LR−) of 0.90 (range: 0.83-0.98).57 (From Jarvis C: Physical examination and health assessment, Philadelphia, 2000, WB Saunders.)

Alternately, the client lies on the pain-free side, and the therapist gently hyperextends the involved leg to stretch the psoas major muscle. Additionally, palpate the iliopsoas muscle by placing the client in a supine position with hips and knees flexed and fully supported in a 90-degree position (Fig. 8-6). Palpate one third of the distance between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the umbilicus. The client is asked to flex the hip gently to assist in isolating the iliopsoas muscle. Muscular tightness in the iliopsoas may result in radiating pain to the low back region during palpation, whereas inflammation or abscess will bring on painful symptoms in the right (or left depending on the underlying pathology) lower abdominal quadrant.

Fig. 8-6 Palpating the iliopsoas muscle. Place the client in a supine position with the hips and knees both flexed and supported at a 90-degree angle. Slowly press fingers into abdomen approximately one third the distance from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) toward the umbilicus. It may be necessary to ask the client to initiate slight hip flexion to help isolate the muscle and avoid palpating the bowel. Reproducing or causing lower quadrant, pelvic, or abdominal pain is considered a positive sign for iliopsoas abscess. Palpation may produce back pain or local muscular pain from shortened or contracted muscle. (From Goodman CC, Fuller KS: Pathology: special implications for the physical therapist, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2009, WB Saunders.)

The obturator muscle test (Fig. 8-7) is also performed when the appendix could be the cause of referred pain to the hip. A perforated appendix or inflamed peritoneum can irritate the obturator muscle, producing right lower quadrant abdominal pain during the obturator test.

Fig. 8-7 Obturator muscle test. In the supine position, perform active assisted motion, flexing at the hip and 90 degrees at the knee. Hold the ankle and rotate the leg internally to stretch the obturator muscle. A negative or normal response is no pain. A positive test for muscle affected by peritoneal infection or inflammation from a perforated appendix reproduces right lower quadrant abdominal or pelvic pain with irritation of the muscle. Although the obturator test has not been studied independently of the psoas test, this sign is assumed to have a sensitivity and specificity similar to the psoas sign. Further research is needed to verify this as a valid and reliable evidence-based test for appendicitis/peritonitis. (From Jarvis C: Physical examination and health assessment, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2007, WB Saunders.)

Although uncommon, psoas abscess still can be confused with a hernia. The therapist may perform evaluative tests to screen for a psoas abscess, but the physician must differentiate between an abscess and a hernia. Psoas abscess is often softer than a femoral hernia and has ill-defined borders, in contrast to the more sharply defined margins of the hernia. The major differentiating feature is the fact that a psoas abscess lies lateral to the femoral artery, whereas the femoral hernia is located medial to the femoral artery.30

Neuropathy

Numbness and weakness of the lower extremities have been reported as a result of vitamin B12 deficiency in the aging adult population or from thiamine deficiency after gastric bypass. Such events are infrequent but expected to increase as the number of gastric bypasses increases.31 Symmetric paresthesias and ataxia associated with loss of vibration and position sense in the lower extremities may occur with vitamin B12 deficiency.

Other symptoms can include irritability, memory loss, and dementia. Thiamine deficiency after gastric bypass may present as early as 2 months or as late as 10 years after the procedure.32,33 Besides neuropathy, presentation may include confusion, nystagmus, seizures, unsteady gait and ataxia, hearing loss, and lower limb hypotonia.32 Symptoms may resolve with medical treatment.

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

GERD is an array of problems related to the backward movement of stomach acids and other stomach contents, such as pepsin and bile, into the esophagus, a phenomenon called acid reflux. Normally, some gastric contents move or reflux from the stomach into the esophagus, but in GERD, the process becomes pathologic, producing symptoms that point to tissue injury in the esophagus and sometimes the respiratory tract.34,35 In adults, GERD is usually caused by intermittent relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms can include heartburn, chest pain, dysphagia, and a sense of a lump in the throat. Symptoms are sometimes mistaken for a heart attack. Less frequent symptoms can include wheezing, hoarseness, coughing, earache, sore throat, and difficulty swallowing. Sleep disturbance from nighttime coughing and heartburn can lead to fatigue and decreased daytime functioning. Complications of GERD may range from discomfort to severe strictures of the esophagus, esophagitis, aspiration pneumonia, and asthma.

Other serious consequences can be related to weight loss, GI blood loss, and Barrett’s esophagus, a precancerous condition. The relationship between GERD and asthma is poorly understood but is thought to be a consequence of aspiration of gastric acid contents into the lung, causing bronchospasm. Most adults with asthma also have GERD.35,36

GERD can occur in infants, but most “outgrow” it. Watch for frequent, forceful spitting up or vomiting, accompanied by irritability. Other alarm symptoms include respiratory distress, apnea, dysphagia, or failure to thrive. Watch for change in color, change in muscle tone, or choking and gagging.

Children may experience GERD in the same way adults do with abdominal or epigastric pain. Nighttime coughing, vomiting, and/or nausea are also possible. Neurologically impaired children and adults are at increased risk for reflux with aspiration. Fluid enters the upper airways from the esophagus, causing chronic respiratory problems, including recurrent pneumonia.

GERD should be treated in order to prevent a chronic condition from occurring with more serious consequences. Symptoms may be mild at first, but have a cumulative effect with increasing symptoms after the age of 40. Chronic GERD is a major risk factor for adenocarcinoma, an increasingly common cancer in white males in the United States.

Medical referral is advised for anyone who reports signs and symptoms of GERD. Some clients may need surgical treatment, now available with less invasive endoscopic techniques, but most can be treated with some simple changes in eating patterns, positioning, and medications. Drug treatment includes antacids, H2-receptor blockers, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Antacids, such as Mylanta, Maalox, Tums, and Rolaids, are available OTC and do not reduce the acid, but merely neutralize it. H2-receptor blockers, such as Tagamet (cimetidine), Zantac (ranitidine), and Pepcid (famotidine), reduce the amount of stomach acid produced by the stomach and are available over the counter.

PPIs, such as Prilosec (omeprazole), Prevacid (lansoprazole), or Nexium (esomeprazole), are the most potent acid-suppressing agents available. These drugs actually inhibit acid formation rather than just neutralize it. The first PPI is now available OTC; others are expected to become available as well. Caution is needed when using PPIs to self-treat without medical supervision. They can mask symptoms of serious GI disorders such as esophageal or stomach cancer. Diagnosis at an early, treatable stage may be delayed with serious implications.

Therapists must listen for client reports of headache, constipation or diarrhea, abdominal pain, or dizziness in anyone taking these medications. The client should be advised to notify his or her medical doctor with a report of these side effects.

Peptic Ulcer

Peptic ulcer is a loss of tissue lining the lower esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. Gastric and duodenal ulcers are considered together in this section. Acute lesions that do not extend through the mucosa are called erosions. Chronic ulcers involve the muscular coat, destroying musculature, and replacing it with permanent scar tissue at the site of healing.

Originally, all ulcers in the upper GI tract were believed to be caused by the aggressive action of hydrochloric acid and pepsin on the mucosa. They thus became known as “peptic ulcers,” which is actually a misnomer.

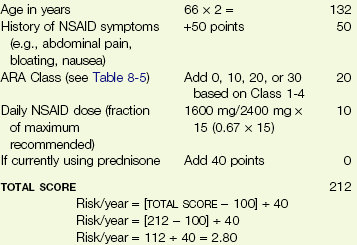

It is now known that many of the gastric and duodenal ulcers are caused by infection with Helicobacter pylori, a corkscrew-shaped bacterium that bores through the layer of mucus that protects the stomach cavity from stomach acid. Ten percent of ulcers are induced by chronic use of NSAIDs, such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen, commonly taken by people with arthritis (Table 8-3).37

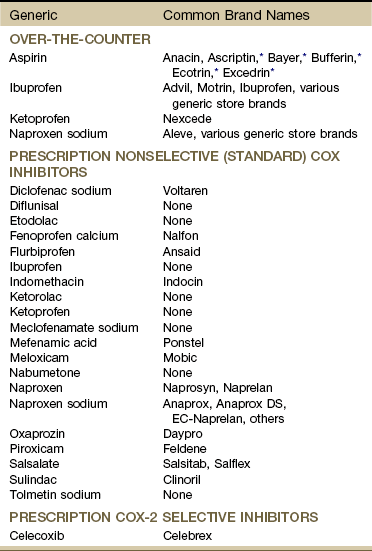

TABLE 8-3

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs, Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; COX, cyclooxygenase.

Information in this table was reviewed and updated by the University of Montana College of Health Professional Biomedical Sciences Drug Information Services (Nicole Marcellus, PharmD candidate), 2010.

*These all have additives to minimize gastrointestinal (GI) side effects but are known as aspirin products. Many nonselective (standard) NSAIDs are available over-the-counter (OTC) at a lower dosage (e.g., 200 mg) and by prescription at a higher dosage (e.g., 500 mg). See discussion of peak effect for NSAIDs and time to impact underlying tissue impairment in Chapter 2.

Data from Drug Facts and Comparisons eAnswers (online), 2010, available from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc (accessed June 23, 2010); Micromedex Healthcare Series (Internet database), Greenwood Village, Colorado, Thomson Reuters (Healthcare) Inc, updated periodically; and Drugs@FDA: FDA-approved drug products website, available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/ (accessed June 23, 2010).

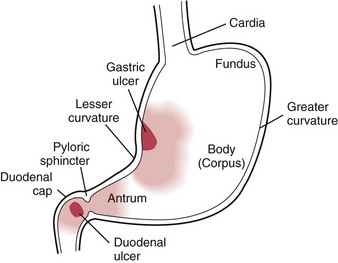

H. pylori ulcers are primarily located in the lining of the duodenum (upper portion of the small intestine that connects to the stomach) (Fig. 8-8). NSAID-induced ulcers occur primarily in the lining of the stomach, most frequently on the posterior wall, which can account for shoulder (usually right shoulder; depends on the extent of retroperitoneal bleeding) or back pain as an associated symptom.

Fig. 8-8 Most common sites for peptic ulcers. Gastric ulcers are found along the distribution on the eighth thoracic nerve with a corresponding pain pattern as described in Fig. 8-13. Pain patterns associated with duodenal ulcers correspond to the tenth thoracic nerve. (Adapted from Ignatavicius DD, Bayne MV: Medical-surgical nursing, Philadelphia, 1991, WB Saunders.)

Ulcers can be dangerous if left untreated, eroding into the stomach arteries and causing life-threatening bleeding or perforating the stomach and spreading infection. H. pylori–induced ulcers can recur after treatment. The recurrence rate is higher in clients with gastric ulcers and in people who smoke, consume alcohol, and use NSAIDs.38 A past medical history of peptic ulcers in anyone with new onset of back or shoulder pain is a red flag requiring further screening and possible medical referral.

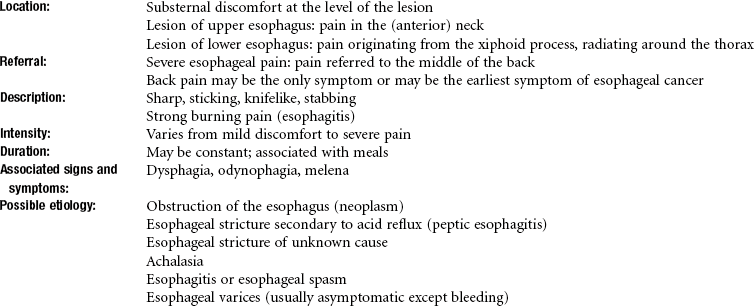

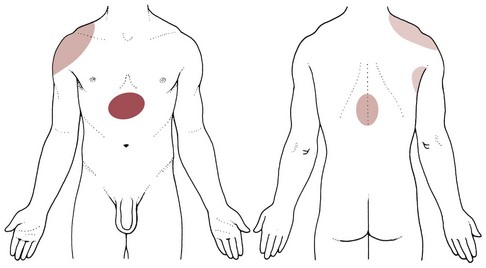

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

The cardinal symptom of peptic ulcer is epigastric pain that may be described as “heartburn” or as burning, gnawing, cramping, or aching located over a small area near the midline in the epigastrium near the xiphoid. Gastric ulcers are found along the distribution of the eighth thoracic nerve which causes pain in the upper epigastrium about one to two inches to the right of a spot halfway between the xiphoid and the umbilicus (see Fig. 8-14). Duodenal pain tends to present more in the right epigastrium, specifically a localized spot one to two inches above and to the right of the umbilicus because of its innervation by the tenth thoracic nerve.

The pain comes in waves that last several minutes (rather than hours) and may radiate below the costal margins into the back or to the right shoulder. The daily pattern of pain is related to the secretion of acid and the presence of food in the stomach to act as a buffer.

Pain associated with duodenal ulcers is prominent when the stomach is empty such as between meals and in the early morning. The pain may last from minutes to hours and may be relieved by antacids. Gastric ulcers are more likely to cause pain associated with the presence of food. Symptoms often appear for 3 or 4 days or weeks and then subside, reappearing weeks or months later.

Other symptoms of uncomplicated peptic ulcer include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, sometimes weight loss, and occasionally back pain. In duodenal ulcers, steady pain near the midline of the back (see Fig. 8-14) between T6 and T10 with radiation to the right upper quadrant may indicate perforation of the posterior duodenal wall.

Back pain may be the first and only symptom. Complications of hemorrhage, perforation, and obstruction may lead to additional symptoms that the client does not relate to the back pain. Bleeding may occur when the ulcer erodes through a blood vessel. It may present as vomited bright red blood or coffee-ground vomitus and by dark tarry stools (melena). The bleeding may vary from massive hemorrhage to occult (hidden) bleeding that occurs over a long period of time.

Symptoms associated with H. pylori include halitosis (bad breath) and a form of facial acne called rosacea. Rosacea is characterized by a rosy appearance of the cheeks, nose, and chin. Facial flushing, red lines, and bumps over the nose may accompany rosacea.

Gastrointestinal Complications of Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs (see Table 8-3) have become increasingly popular by virtue of their analgesic, antiinflammatory, antipyretic, and antithrombotic (platelet-inhibitory) actions. More than 70 million prescriptions are written each year in the United States. If you add OTC use, then 30 billion doses of NSAIDs are consumed annually in the United States.39

Most commonly taken NSAIDs really have few toxic effects. On the other hand, NSAIDs can have deleterious effects on the entire GI tract from the esophagus to the colon, although the most obvious clinical effect is on the gastroduodenal mucosa. GI impairment can be seen as subclinical erosions of the mucosa or more seriously, as ulceration with life-threatening bleeding and perforation.

The incidence of NSAID-related ulcer complications remains high despite the availability of newer gastroprotective NSAIDs such as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib, rofecoxib).40 COX inhibitors, a group of enzymes that facilitate the production of prostaglandins, exist in two forms: COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 promotes proper GI function and blood clotting. COX-2 has a role in preventing or reducing the inflammatory response.41

Standard NSAIDs nonselectively inhibit the actions of both types of COX inhibitors so the client gets the antiinflammatory effect but at the expense of the GI system. COX-2 inhibitors suppress COX-2, providing some benefit in reducing ulcer formation and GI bleeding, although they do not completely reduce the risk and have been shown to increase the incidence of myocardial events. If the newer agents are combined with even low-dose aspirin, the safety of the COX-2 agent is partially negated.42,43 Low-dose aspirin is defined as 325 mg taken every other day or one “baby aspirin” containing 81 mg used for cardioprotection by people with or at risk for heart disease.

Infection with H. pylori bacteria increases the risk of ulcer disease threefold or more in people taking standard NSAIDs or low-dose aspirin.44 COX-2 inhibitors are widely promoted as easier on the stomach than older NSAIDs, but not all clients are taking this newer generation of NSAIDs. For those who are taking COX-2 agents, preliminary studies show clients with a history of bleeding ulcer are at increased risk of recurrence so these clients must be monitored closely as well.40 With a 6-month period of treatment with NSAIDs, dyspepsia (digestive discomfort potentially leading to ulceration) occurs in 15% to 30% (some reports put this figure closer to 50%) of adults using NSAIDs,45,46 but we must remember that physical and occupational therapists are seeing a majority of these people.

People with NSAID-induced GI impairment can be asymptomatic until the condition is advanced. GI effects of NSAIDs are responsible for approximately 40% of hospital admissions among clients with arthritis. NSAID-induced GI bleeding is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among the aging adult population.47

For those who are symptomatic, the most common side effects of NSAIDs are stomach upset and pain, possibly leading to ulceration. GI complications of NSAID use include ulcerations, hemorrhage, perforation, stricture formation, and exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease. Each NSAID has its own pharmacodynamic characteristics, and clients’ responses to each drug may vary greatly.

Other possible adverse side effects of NSAIDs may include suppression of cartilage repair and synthesis, fluid retention and kidney damage, liver damage, skin reactions (e.g., itching, rashes, acne), and impairment of the nervous system such as headache, depression, confusion or memory loss, mood changes, and ringing in the ears.39

Many people diagnosed with painful musculoskeletal conditions, especially arthritis, rely on NSAIDs to relieve pain and improve function. Anyone with a current history of NSAID use presenting with back or shoulder pain, especially when accompanied by any of the associated signs and symptoms listed for peptic ulcer, must be evaluated by a physician. The therapist should remain alert for the client taking multiple NSAIDs and simultaneously combining prescription and OTC NSAIDs or other drugs.

These drugs are potent renal vasoconstrictors, so look for increased blood pressure and ankle/foot edema. Take vital signs and visually inspect clients at risk for NSAID-induced impairments. Ask about muscle weakness, unusual fatigue, restless legs syndrome, polyuria, nocturia, or pruritus (signs of renal failure). In the aging adult, NSAID use may be associated with confusion and memory loss or increased confusion in the client with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. Teach clients to recognize signs and symptoms of adverse effects from NSAIDs and report any associated signs and symptoms to the physician. Changing the dosage or switching to a different NSAID at the first sign of side effects can help clients avoid serious complications that can occur with prolonged use of an inappropriate dose or poorly tolerated NSAID.

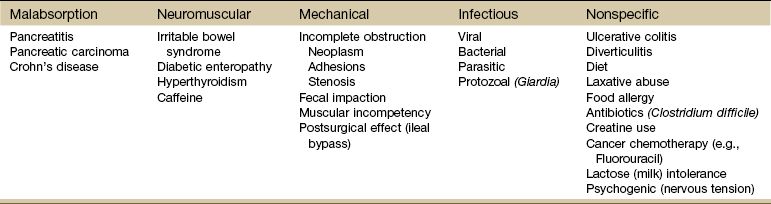

Risk factor assessment is especially important in the primary care setting. Any identified risk factors should serve as red flags in any setting. The most predictive risk factors of serious GI events include age, disability, NSAID use, previous GI hospitalization, prior GI symptoms with NSAIDs, and use of prednisone (Box 8-3 and Case Example 8-6). See Chapter 2 for information on screening for the use of NSAIDs.

Is Your Client At Risk for NSAID-Induced Gastropathy?: Therapists also can estimate the risk of GI complications in clients with rheumatoid arthritis. The tool in Table 8-4 can be used with clients who are taking NSAIDs of any kind for rheumatoid arthritis. This tool may prove valuable in assessing other patient populations as well.48 This calculation can be used in one of several ways. First, clinical research is needed to substantiate the number of clients in a physical therapy practice who are at risk for serious NSAID-related gastropathy.

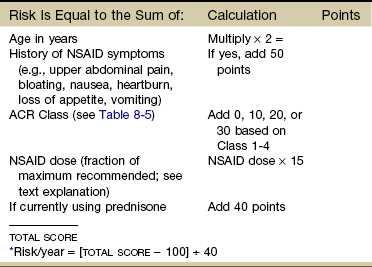

TABLE 8-4

Calculating Your Client’s Risk of NSAID-Induced Gastropathy

NSAID, Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; ACR, College of Rheumatology.

*Higher total scores yield a greater predictive risk. The risk ranges from 0.0 (low risk) to 5.0 (high risk).

From Fries JF, et al: Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-associated gastropathy: incidence and risk factor models, Am J Med 91(3):213-222, 1991.

Second, charting a client’s risk can help in the early identification of problems. Because prednisone use and NSAID dose are modifiable risk factors, early identification and referral to the physician can minimize the detrimental effects of NSAID-induced gastropathy. Clients with one or more risk factors for NSAID-associated GI ulcer should be prescribed preventive strategies, such as acid-suppressive drugs and/or COX-2 inhibitors, rather than standard NSAIDs.49,50

Third, from a fiscal point of view, every GI complication prevented lowers the cost of medical care in this country. Clients over 50 with comorbidities, such as heart disease, renal disease, a history of ulcers, or taking prednisone or warfarin, must be watched carefully.

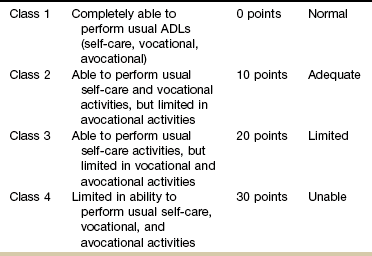

The scoring system in Table 8-4 was designed to allow clinicians to estimate the risk of GI problems in clients with rheumatoid arthritis who are also taking NSAIDs.51 The formula is based on age, history of NSAID symptoms, NSAID dose, and the American College of Rheumatology’s (ACR) Functional Classes (Table 8-5).

TABLE 8-5

ACR Criteria for Classification of Functional Status in Rheumatoid Arthritis

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ADLs, activities of daily living.

NSAID dose used in this formulation is the fraction of the manufacturer’s highest recommended dose. The manufacturer’s highest recommended dose on the package insert is given a value of 1.00. The dose of each client is then normalized to this dose.

For example, the value 1.03 indicates the client is taking 103% of the manufacturer’s highest recommended dose. Most often, clients are taking the highest dose recommended. They receive a 1.0. Anyone taking less will have a fraction percentage less than 1.0. Anyone taking more than the highest dose recommended will have a fraction percentage greater than 1.0. See formulation in Case Example 8-7.

To determine the risk (%) of hospitalization or death caused by GI complications over the next 12 months, subtract 100 from the total score obtained in Table 8-4 and divide the result by 40. Higher total scores yield a greater predictive risk. The risk ranges from 0.0 (low risk) to 5.0 (high risk) (see Case Example 8-7).

Note that although further studies validating this tool have not been published, additional efforts to predict the risk of GI bleeding due to NSAID use have shown a significant increase in the GI event rate associated with age, sex, prior GI bleeds, use of GI medications, and prednisone use. The use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) was not linked with gastropathy.52

Diverticular Disease

The terms diverticulosis and diverticulitis are used interchangeably although they have distinct meanings. Diverticulosis is a benign condition in which the mucosa (lining) of the colon balloons out through weakened areas in the wall. Up to 60% of people over age 65 have these saclike protrusions. Someone with diverticulosis is typically asymptomatic; the diverticula are diagnosed when screening for colon cancer or other problems.53

Diverticulitis describes the infection and inflammation that accompany a microperforation of one of the diverticula. Diverticulosis is very common, whereas complications resulting in diverticulitis occur in only 10% to 25% of people with diverticulosis. The most common cause of major lower intestinal tract bleeding is diverticulosis. A significant number of cases of diverticular bleeding are associated with the use of NSAIDs in combination with diverticulosis.54

There is some controversy regarding whether diverticulosis is symptomatic, but perforation and subsequent infection causes symptoms of left lower abdominal or pelvic pain and tenderness in diverticulitis. For the therapist performing the iliopsoas and obturator tests, abdominal pain in the left lower quadrant may be caused by diverticular disease and should be reported to the physician. The diagnosis of diverticulitis is confirmed by accompanying fever, bloody stools, elevated white blood cell count, and imaging studies.

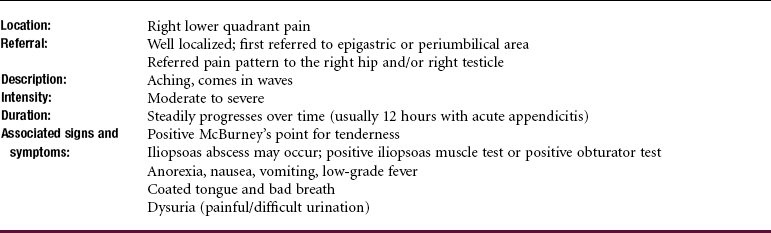

Appendicitis

Appendicitis is an inflammation of the vermiform appendix that occurs most commonly in adolescents and young adults. It is a serious disease usually requiring surgery. When the appendix becomes obstructed, inflamed, and infected, rupture may occur, leading to peritonitis.

Diseases that can be mistaken for appendicitis include Crohn’s disease (regional enteritis), perforated duodenal ulcer, gallbladder attacks, and kidney infection on the right side, and for women, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, twisted ovarian cyst, or a hemorrhaging ovarian follicle at the middle of the menstrual cycle. Right lower lobe pneumonia sometimes is associated with prominent right lower quadrant pain.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

The classic symptoms of appendicitis are pain preceding nausea and vomiting and low-grade fever in adults. Children tend to have higher fevers. Other symptoms may include coated tongue and bad breath.

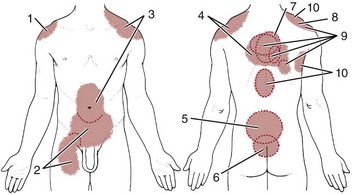

The pain usually begins in the umbilical region and eventually localizes in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen over the site of the appendix. In retrocecal appendicitis, the pain may be referred to the thigh or right testicle (see Fig. 8-10). Groin and/or testicular pain may be the only symptoms of appendicitis, especially in young, healthy, male athletes. The pain comes in waves, becomes steady, and is aggravated by movement, causing the client to bend over and tense the abdominal muscles or to lie down and draw the legs up to relieve abdominal muscle tension (Case Example 8-8).

Generalized peritonitis, whether caused by appendicitis or some other abdominal or pelvic inflammatory condition, can result in a “boardlike” abdomen due to the spasm of the rectus abdominis muscles. Lean muscle mass deteriorates with aging, especially evident in the abdominal muscles of the aging population. The very old person may not present with this classic sign of generalized peritonitis because of the lack of toned abdominal muscles.

For this reason, the nursing home, skilled care facility, or home health therapist must evaluate the aging client who presents with hip or thigh pain for possible systemic origin (assess for signs of peritonitis and/or appendicitis as appropriate; see also McBurney’s point, and specific tests for iliopsoas or obturator abscess).

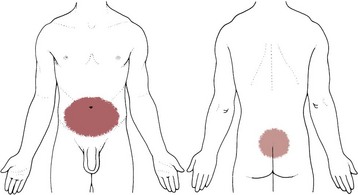

McBurney’s Point

Parietal pain caused by inflammation of the peritoneum in acute appendicitis or peritonitis (from appendicitis or other inflammatory/infectious causes) may be located at McBurney’s point (Fig. 8-9). The vermiform appendix receives its sympathetic supply from the 11th thoracic segment. In some people, a branch of the 11th thoracic nerve pierces the rectus abdominis muscle and innervates the skin over McBurney’s point. This may explain the hyperalgesia seen at this point in appendicitis.6

Fig. 8-9 The vermiform appendix and colon can refer pain to the area of sensory distribution for the eleventh thoracic nerve (T11). Primary (dark red) and referred (light red) pain patterns associated with the vermiform appendix are shown here with McBurney’s point halfway between the ASIS and the umbilicus, usually on the right side. Gentle palpation of McBurney’s point produces pain or exquisite tenderness. Pinch-an-inch test should also be assessed (see Fig. 8-11).

McBurney’s point is located by palpation with the client in a fully supine position. Isolate the ASIS and the umbilicus, then palpate for tenderness halfway between these two surface anatomic points. This method differs from palpation of the iliopsoas muscle because the position used to locate the iliopsoas muscle is the client in a supine position, with hips and knees flexed in a 90-degree position, whereas McBurney’s point is palpated with the client in the fully supine position.

The palpation point for the iliopsoas muscle is one-third the distance between the ASIS and the umbilicus, whereas McBurney’s point is halfway between these two points. Be aware that the location of the vermiform appendix can vary from individual to individual making the predictive value of this test less accurate (Fig. 8-10). Since the appendix develops during the descent of the colon, its final position can be posterior to the cecum or colon. These positions of the appendix are called retrocecal or retrocolic, respectively. In about 50% of cases, the appendix is retrocecal or retrocolic.56 Atypical locations of the appendix can lead to unusual clinical findings with poorly localized abdominal or pelvic pain, unusual symptoms of urinary and defecation urgency (due to irritation of the ureter and rectum), painful urination, and diarrhea.57

Fig. 8-10 Variations in the location of the vermiform appendix. Negative tests for appendicitis using McBurney’s point may occur when the appendix is located somewhere other than at the end of the cecum. In 50% of cases the appendix is retrocecal (behind the cecum) or retrocolic (behind the colon). See Fig. 8-11 for an alternate test.

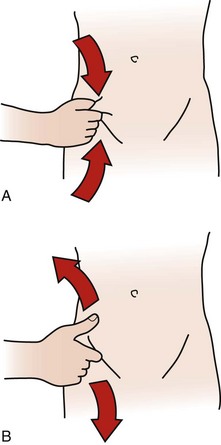

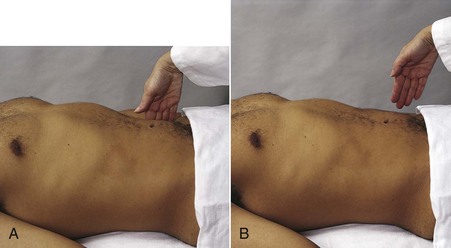

Both McBurney’s point and the iliopsoas muscle are palpated for reproduction of symptoms to rule out appendicitis or iliopsoas abscess associated with appendicitis or peritonitis. Alternately, instead of palpating for McBurney’s point (these tests can be very painful when positive), perform a pinch-an-inch test (Fig. 8-11). This test is a new technique for detecting peritonitis/appendicitis that is more comfortable and statistically equivalent to the traditional rebound tenderness technique.58,59 Like a rebound tenderness test, a positive pinch-an-inch test is a classic sign of peritonitis and represents aggravation by stretching or moving the parietal layer of the peritoneum. A positive pinch-an-inch test, or alternately, rebound tenderness, may occur with any disease or condition affecting the peritoneum (including appendicitis when it has progressed to include peritonitis). If the pinch-an-inch test is negative, then proceed with the rebound tenderness test (Fig. 8-12) and/or palpation of McBurney’s point.

Fig. 8-11 Pinch-an-inch test. A, To avoid the discomfort of the classic rebound tenderness (Blumberg’s) test, the pinch-an-inch test is recommended to assess for appendicitis or generalized peritonitis. To perform the test, a fold of abdominal skin over McBurney’s point is gently grasped and elevated away from the peritoneum. B, The skin is then allowed to recoil back against the peritoneum quickly. If the individual has increased pain when the skin fold strikes the peritoneum (upon release of the skin), the test is positive for possible peritonitis. If the person being tested reacts to the pinch in an excessive fashion, he or she may have a very low pain threshold, a factor that should be taken into consideration when assessing the results.58,59

Fig. 8-12 Rebound tenderness or Blumberg’s sign. A, To assess for appendicitis or generalized peritonitis, press your fingers gently but deeply over the right lower quadrant for 15-30 seconds. B, The palpating hand is then quickly removed. Pain induced or increased by quick withdrawal results from rapid movement of inflamed peritoneum and is called rebound tenderness. When rebound tenderness is present, the client will have pain or increased pain on the side of the inflammation when the palpatory pressure is released. Ask the client if it hurts as you are palpating or during the release. Since abdominal pain is increased uncomfortably with this test, save it for last when assessing abdominal pain during the physical examination. (From Jarvis C: Physical examination and health assessment, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2007, WB Saunders.)

Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis is an inflammation of the pancreas that may result in autodigestion of the pancreas by its own enzymes. Pancreatitis can be acute or chronic, but the therapist is most likely to see individuals with referred pain patterns associated with acute pancreatitis. The pancreas is both an exocrine gland and an endocrine gland. Its function in digestion is primarily an exocrine activity. This chapter focuses on digestive disorders associated with the pancreas. See Chapter 11 for pancreatic disorders associated with endocrine function.

Acute pancreatitis can arise from a variety of etiologic (risk) factors, but in most instances, the specific cause is unknown. Chronic alcoholism or toxicity from some other agent, such as glucocorticoids, thiazide diuretics, or acetaminophen, can bring on an acute attack of pancreatitis. Chronic pancreatitis is caused by long-standing alcohol abuse in more than 90% of adult cases. In these cases, chronic pancreatitis is characterized by the progressive destruction of the pancreas with accompanying irregular fibrosis and chronic inflammation.60

A mechanical obstruction of the biliary tract may be present, usually because of gallstones in the bile ducts. Viral infections (e.g., mumps, herpesviruses, hepatitis) also may cause an acute inflammation of the pancreas.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

The clinical course of most clients with acute pancreatitis follows a self-limited pattern. Symptoms can vary from mild, nonspecific abdominal pain to profound shock with coma and possible death. Abdominal pain begins abruptly in the midepigastrium, increases in intensity for several hours, and can last from days to more than a week.

The pain has a penetrating quality and radiates to the back. Pain is made worse by walking and lying supine and is relieved by sitting and leaning forward. The client may have a bluish discoloration of the periumbilical area (Cullen sign) as a physical manifestation of acute pancreatitis. This occurs in cases of severe hemorrhagic pancreatitis. Turner’s sign is a reddish-brown discoloration of the flanks, also present in hemorrhagic pancreatitis.