Chapter Twenty One Qualitative data analysis

Introduction

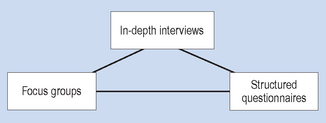

Qualitative data are collected through techniques such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, participant observation and narratives spoken and written by the participants and researchers involved in the study. Qualitative data analysis refers to the processes by which researchers organize the information collected and analyse the meanings of what was said and done by the participants. In qualitative data analysis we bring our values, experiences and social understanding into analysing and constructing the meaning of what our respondents were telling us about their lives. At the same time, qualitative data analysis is prin-cipled; there are various explicit and shared strategies for summarizing and making sense of the data and checking the accuracy of our interpretation.

The aims of this chapter are to:

Understanding meaning in everyday life

Understanding people involves discovering the contents of people’s minds – their beliefs, desires, intentions. There is nothing remarkable or supernatural being implied by this, simply that we infer mental contents by listening to and observing what people say and do, taking into account the social settings in which these actions occur.

For instance, one person says to another: ‘Would you like to come in for a coffee?’ What are the intentions of the speaker? Does he or she simply want to prepare the dark beverage and consume it in silence? Or should we look for ‘hidden’ or ‘latent’ meanings in order to understand the speaker’s true intentions? Consider these two everyday scenarios (Polgar & Swerissen 2000):

The above dialogue shows the nuances in the everyday use of language. Just as we sometimes misunderstand meanings and intentions in everyday life, we can also misinterpret the data produced by qualitative data collection. To avoid error we need to cross-check the accuracy of our interpretation.

Coding qualitative data

Qualitative data analysis frequently involves analysis of verbatim transcripts of dialogues and narratives. A common point of departure for analysing the transcript data is to develop a coding system. A coding system is to organize the data into specific classes or categories. There are two fundamental approaches to coding: predetermined and emerging with thematic analysis.

Predetermined coding

Predetermined coding uses predetermined categories to organize and analyse the transcripts.

For example, you might be conducting a survey to determine how clients experienced a rehabilitation programme at your workplace. Say that you conducted 20 in-depth interviews and produced a 100-page transcript representing what people said in these interviews. Considering your research aims, you might code the statements into three categories:

At the simplest level, analysing the first two categories would enable us to understand the reasons why the clients found the rehabilitation programmes to be satisfactory or unsatisfactory. This information could be useful for improving the programme. In most studies the coding system would be a good deal more elaborate.

Coding and thematic analysis

An alternative approach to using predetermined codes is to develop a coding system that identifies common themes as they emerge from the text. Different qualitative researchers advocate different approaches to coding but it typically involves the following steps. The researchers first study their materials, in this case transcripts, and develop a close familiarity with the material. During this process, all the concepts, themes and ideas are noted to form major categories. Often, the researcher will then attach a label and/or number to each category and record their positions in the transcript. Coding is an iterative process (we retrace our steps), with the researcher coding and recoding as the scheme develops. The researchers, having developed the codes and coded the trans-cripts, then attempt to interpret their meanings in the context in which they appeared. The reporting of this process typically involves ‘thick’ or detailed description of the categories and their context, with liberal use of examples from the original transcripts.

Content analysis

Content analysis allows the quantification of units of meaning occurring in a text or a number of texts. Content analysis can be seen as a blending of quantitative and qualitative methods. The recognition and coding of meaning are qualitative, while the counting of the meaningful ‘chunks’ is quantitative. The ‘meaningful chunks’ can be words, sentences or paragraphs, that is, the units of language that were coded by the researchers from the narratives and dialogues.

For example, in an unpublished study one of the authors was interested in how leading newspapers were representing the use of stem cells in medical research. The following research questions were asked:

In relation to question 1, the data were collected by identifying relevant newspaper articles published on the topic and measuring the length of the columns. They were quantified by counting the number of articles published per month across the selected time interval. The data rele-vant to question 2 were obtained by identifying statements supportive or critical of using stem cells or simply ‘neutral’ descriptions of the nature and possible uses of stem cells. The column lengths for each of the three categories were measured and the percentages devoted to each were graphed across the months. Therefore, the content analysis provided evidence for the level of interest and changing attitudes of the media towards the use of stem cells. This evidence was relevant to understanding the cultural context in which government policy for using stem cells was being formulated.

The discussion of content analysis provides a good opportunity for raising the issue of computer-assisted data analysis. As the texts are often transcribed using personal computers the text is available in electronic form. This means that the text can be fed into a software package to assist with its analysis. For example, say that the data representing the contents of a hundred newspaper articles were transcribed into a software package. We could now introduce our codes and identify the segments of the whole text which use the relevant words/phrases/sentences. The segments can then be retrieved, examined or modified (cut and paste) on screen. Also, various frequency counts can be readily performed using software tools.

A detailed discussion for selecting and using computer packages is beyond the scope of the present book. Interested readers might find Liamputtong Rice & Ezzy (1999, pp 202–210) a useful introduction to selecting and using currently available software packages for expediting and improving qualitative data analysis in general (not only for content analysis). Liamputtong Rice & Ezzy have discussed the ambivalent attitude among qualitative researchers to computer-assisted data analysis. A key objection has been the distancing of the researcher from the creativity and surprising insights afforded by the more hands-on approaches. Another objection is that meanings of words and sentences sometimes do not follow dictionary definitions but rather have to be understood in the general context. The true meaning of certain subtle and ambiguous communications can be missed in crude and electronically conducted data analyses.

Content analysis is a technique that combines elements of both qualitative and quantitative approaches. We interpret the meaning of the text for developing our coding strategy for organizing or ‘chunking’ the text and then we use statistics to describe the quantities of text devoted to a specific point of view. Content analysis can be used to test hypotheses, for example hypotheses addressing media perspectives on embryonic stem cell research.

Thematic analysis, verstehen and grounded theory

Counting and hypothesis testing is not the essence of the qualitative approach. What we are trying to do is to see things from the perspectives of our informants and to explain their actions from their points of view. The German word verstehen is often used in phenomenological research to express the notion of ‘putting ourselves in someone else’s shoes’ or attaining a strong empathy with their situation. Empathy with other people might seem quite simple, just something we do as human beings. It is worthwhile remembering, however, that sometimes we misunderstand how people feel or think, even when they are our close friends or family. In the same way, we might misunderstand the points of view of persons who are very different to us in age, gender, education, language and culture. Yet, it is essential to understand the points of views of the people to whom we offer health services. So how does ‘verstehen’ arise through qualitative health research?

First, as we described earlier, our data collection must use a technique (in-depth interviews, written materials, focus groups, etc.) which enables our respondents to express their point of view. Second, we can adopt a theoretical framework for explaining our understanding of the respondents’ experiences. The key point, in the context of grounded theory, is that our explan-ations or theories must emerge inductively from the information provided by our informants. The theory is constructed gradually as more evidence is provided by additional informants. Third, the data are often analysed by coding and thematic analysis as we outlined earlier in this chapter.

A theme is a grouping of ideas or meanings which emerge consistently in the text. The themes emerging from the data illuminate the experiences of the informants and enable us to understand their points of view (verstehen). Let us consider an example of thematic analysis.

In a study titled ‘The plight of rural parents caring for adult children with HIV’, Fred McGinn (1996) studied the experiences of parents caring for their adult children with acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome/human immuno-deficiency virus (AIDS/HIV). In-depth interviews were conducted with eight mothers and two fathers from rural families involved in this task. The interview transcripts were analysed using a thematic analysis/grounded theory approach (Miles & Huberman 1984).

McGinn extracted three major themes:

‘He would fall over, so I would sit him in the wheelchair. And then from within a week in November he went from not being able to sit in the wheelchair to not getting out of bed. And he went from eating little bits of food along with taking a liquid nutrition to just liquid nutrition … and then he got to where he wouldn’t swallow the liquid nutrition and he subsisted on just water and juices and Pepsi … and then in the end he even refused them: he wouldn’t take anything … He just wasted away.’

‘That Sunday, I never will forget. I asked him, ‘Do you want anybody to know?’ And I don’t remember if he said no, but his head … he almost shook it off. No way did he want anybody to know what the real problem was. But I want you to know that that was a terrible, stressful time. People who came, who normally would be support for me … weren’t. It was a real traumatic experience.’

‘As for the hospital, I couldn’t have asked for a better hospital. There may have been nurses who refused to work with him, I don’t know, but the nurses that did come in were great … They even hugged and kissed him goodbye whenever he got well and left. They didn’t act like they didn’t want to be around him and I appreciated that. I think that’s important.’

These three themes enable us to understand and empathize with the parents of these very sick young people. Also, they were the bases for recommending improvements in rural health care which directly address the needs of AIDS sufferers and their families in non-metropolitan environments.

Also, we must note that McGinn’s paper reported the experiences of people in the mid-1990s, living in rural Canada. With improvements in the treatment and prevention of AIDS and a decrease in the stigma attached to the condition, the experiences of families caring for sufferers have improved. Because of differences and changes in practices and the cultural context, it is always important to note the time at and place in which interpretive research was carried out.

Interpretation and social context

As we have seen, qualitative data analysis is a systematic way of interpreting texts. There are many areas of study (e.g. history, politics, theology) where the interpretation of texts is an essential part of the research process. What these diverse disciplines have in common with qualitative health research is the recognition that the meaning of language and texts must be interpreted in a cultural context.

An example is hermeneutics, which is a method that was originally used to analyse the meaning of religious texts. Consider the meaning of the term ‘god’. When the Romans spoke of Augustus Caesar as a ‘god’, they were referring to him as a hero who was immortal in the history of Rome. The use of the term ‘god’ by a polytheistic is quite different to meanings in the context of contemporary Judaeo–Christian or Muslim traditions. The meaning of the term must be interpreted in the context of the religious tradition (polytheistic, monotheistic) and the position of the speaker (believer, non-believer).

An important issue in reading texts is that they might have implicit (in addition to explicit) meanings. Semiotics is a method of textual interpret-ation which seeks to uncover the hidden, omitted meanings implicit in a text. In order to do this, we must adopt a theoretical framework in terms of which we can ‘deconstruct’ a text. The theor-etical framework reflects our understanding of the culture within which the text was produced. You have probably read the book Animal Farm by George Orwell. There are several levels at which one can read this story; for example:

In order to identify Orwell’s book as a political critique, one needs to understand the historical/cultural context in which the author worked and lived.

To illustrate these points, we will examine a letter to the editor in a Melbourne newspaper by a woman writer who was apparently concerned about the physical and mental health of young men:

Since the weather improved, it seems that young men all over the place are discarding their shirts and going about half-naked. I worry for them. Do they have any idea of what a provocative and inviting image they put across?

To my mind, they would be doing themselves a far greater service if they would just compromise a little and get dressed properly. It might not seem fair, and it might be less comfortable, but at least then there wouldn’t any longer be the danger of urge-driven women raping young men because of the confusing visual signals they so often put across.

(In Polgar & Swerissen 2000).

Let us analyse the text consistent with a procedure outlined in Daly et al (1997). First, let us analyse the explicit content of the letter.

You may have different views about how best to interpret the text. As Daly and her colleagues (1997, p. 183) noted: ‘Let us now make some basic semiotic moves across the data’. Let us interrogate the ‘data’ further using the six points suggested by Daly et al (1997).

In the next part of this chapter we will outline some strategies for ensuring validity and reliability for qualitative research.

The accuracy of qualitative data analysis

How can we be sure that the themes we identified in a text accurately reflect the actual views of the participants? Also, how do we know that similar themes would emerge from the reports of other people who had similar experiences to our sample?

There are a number of qualitative researchers who ensure that the collection and interpretation of their evidence are carried out in a methodologically rigorous fashion. The following represent some of the key methodological criteria for conducting qualitative research (Lincoln & Guba 1985):

As you can see, the methodological concerns in qualitative research are parallel to those of quantitative research (i.e. reliability and validity). However, because of the differences in the way the two types of research are conducted, the terminology for describing the methodological principles is somewhat different.

Summary

There are different approaches to analysing qualitative data depending on the theoretical framework and data collection strategies adopted by the researchers. However, as we saw in this chapter, there are several common aspects to qualitative data analysis:

Self-assessment

Explain the meaning of the following terms: