Framing the Problem

Where do you begin now that you are ready to participate in the research process? An important initial challenge in the conduct of research is the selection of a topic and, within that area, a specific problem that is meaningful to study, appropriate for scientific inquiry, and purposeful. By “meaningful”

we suggest that the identified research problem should lead to an inquiry that allows the development of new knowledge or verification of existing knowledge that is useful to the individual, his or her profession or social group, or both. By “appropriate” we mean that the selection of a problem can be submitted to a systematic research process and that the research will yield knowledge to help solve the identified problem. Not all problems relevant to health and human service providers can be addressed through systematic inquiry. By “purposeful,” we suggest that health and human service research be designed with purposes that serve investigators, consumers, professionals, funders, policy makers, and others concerned with the delivery of health and human services.

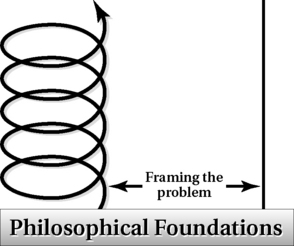

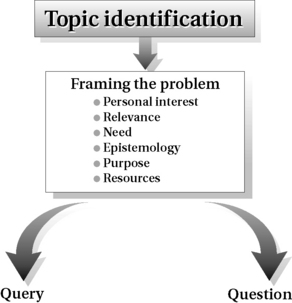

Most beginning researchers are able to identify a topic of interest to them. However, many find that identifying a specific research problem within a topic of interest is a more difficult task. This difficulty is caused in part by the novice investigator's unfamiliarity with problem formulation and its relationship to the research process. It is important to recognize that the way in which a research problem is framed influences and shapes all subsequent thinking and action processes. More specifically, as depicted in Figure 4-1, the way the research problem is framed will lead to the development of a specific research question in the experimental-type tradition of research, or to a line of query in the naturalistic tradition, or to a question and query that integrate both research traditions. Thus, problem identification is not simply a matter of isolating a specific problem statement; one must also have a clear understanding of the relationships among topic, problem formulation, research question/query, and action processes to frame a meaningful, appropriate, and purposeful problem statement.

Problem formulation is also influenced by the personal characteristics of the researcher, including personal interest, perceived need, and preferred epistemology (Box 4-1).

This chapter examines the thinking processes involved in identifying a topic, framing a research problem, and linking design selection to the purpose of the study.

Identifying a topic

The first consideration in beginning a research project is to identify a topic from which to pursue a specific investigation. A research topic is a broad issue or area that is important to a health and human service professional. One topic may yield many different problems and strategies for investigation.

It is usually easy to identify a topic that is of personal interest or one that is relevant to and important for professional practice.

Where do topics and specific problem areas come from? There are five basic sources helpful to professionals in selecting a topic and researchable problem (Box 4-2).

Professional Experience

The professional arena is perhaps the most immediate and important source from which research problems evolve. The ideas, unanswered questions, or “professional challenges” (similar to those posed in Chapter 1) that routinely arise often yield significant areas of inquiry. A reflective practitioner can pose many queries in the course of service delivery that may warrant the research process. Many of the themes or persistent issues that emerge in case review, supervision, or faculty, student, and staff conferences may provide investigators with researchable topics and specific questions/queries. Themes that cut across diverse individuals, such as family involvement or consumer perceptions of their experiences in health and human services, provide topics that may ultimately stimulate the framing of specific research problems.

Societal Trends

Social concerns and trends reflected in the policies, legislation, and funding priorities of federal, state, and local agencies, foundations, and corporations provide another critical area from which potential inquiries for health and human service investigation emerge. For example, the government reports Healthy People 2010 and 2020, U.S. Public Health Service documents, establish health-related objectives and priorities for the United States. Similarly, the reports on health care and practice generated by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) also identify priority research areas. For example, its 2001 publication, “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,” outlines the fundamental changes needed in the U.S. health care system, which are still relevant today. Similarly, its recent book, Retooling for America, provides important data about current health care and raises the many difficult problem areas that must be addressed through research, education, and change in health policy. You may also want to look at the publications of the World Health Organization (WHO) or Rehabilitation International to identify international priorities. These types of documents provide an important source for identifying research problems and specific questions and queries with high public health importance.

Another social arena from which research problems emerge is the set of specific requests for research generated by federal, state, and local governments. Government agencies have numerous established funding streams that provide monetary support to researchers who identify meaningful and appropriate research problems within topic areas relevant to the delivery of health and human services.

To publicize research priorities set by the federal government, the Federal Register, a daily publication of the U.S. government (appearing in both hard-copy and online formats), lists funding opportunities and policy developments of each branch of the federal government. Most libraries receive the hard-copy publication, and the online version can be accessed through the World Wide Web (Internet). The Federal Register is an invaluable resource to help identify problem areas and funding sources. Numerous other sources list research grant opportunities, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for Grants and Contracts, the Federal Grants and Contracts Weekly, and the Chronicle of Higher Education—just to name a few in the United States. If you are interested in learning about the international and global research issues and questions that are important to grant funders, you can consult the Internet and search your area of interest. Many government sources (e.g., Fulbright Commission; Fogarty Center) and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have specific focal areas concerning international investigations.

Professional Trends

Other resources for identifying important research topics are the online or hard-copy newsletters and publications of each health and human service profession. Investigators frequently read these resources to determine the broad topic areas and problems of current interest to a given profession. Also, professional associations establish specific short-term and long-term research goals and priorities for their professions.

More recently, professional associations have been interested in advancing evidence-based practice, so they have sponsored research endeavors to identify the barriers to using this approach and mechanisms for advancing its integration into daily practice. Examining the goals and policy statements of professional associations provides a good source from which to establish a research direction.

Research Studies

The research world itself also provides a significant avenue from which to identify research topics and problem areas. Health and human service professionals encounter research ideas by interacting with peers, attending professional meetings that report research findings, participating in research projects, and reviewing published research reports. Reading scholarship in print and online professional journals provides an overview of the important studies conducted in an area of interest. Most published research studies identify additional research problems and unresolved issues generated by the research findings as part of the discussion section of the paper. Journals in all formats (e.g., online; bound copies) publish current research findings that are useful and relevant to the helping professions; these include the Journal of Dental Hygiene, Journal of the American Medical Association, Research in Social Work Practice, American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, Nursing Research, Medical Care, Physical Therapy, Qualitative Research in Health Care, The Social Service Review, American Journal of Public Health, Psychological Review, and Social Work Research to identify just a few of the most important journals to review and identify current research knowledge in areas relevant to health and human service professionals.

Routinely reading journals related to your profession and areas of interest will also provide you with specific ideas as to what concerns and issues your professional peers believe are important to investigate, as well as the studies that need to be replicated or repeated to confirm the findings. There are many other journals published by the helping professions and related disciplines that may assist in identifying a topic. Substantive topic journals that cross disciplines, such as Archives of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Psychiatric Services, Journal of Gerontology, Childhood and Adolescence, Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, The Gerontologist, and Journal of Rehabilitation, are just a few of the outstanding journals that provide specific ideas for research studies that need to be conducted in topics relevant to health and human service professionals. New journals are always being developed to capture emerging specific research topics.

Finally, reading articles that provide a comprehensive overview or meta-analysis of a focused body of research is helpful. Such articles usually summarize the state of knowledge to date and identify future research needs.

Existing Theory

Theories also provide an important source for generating topics and identifying research problems. As we discuss in Chapter 6, a theory posits a number of propositions and relationships between and among concepts. To be considered a theory, each specified relationship within the theory must be submitted to systematic investigation for verification or falsification. Inquiry related to theory development is intended to substantiate the theory and advance or modify its development by refuting some or all of its principles.

Other Sources

Although we caution you to carefully evaluate the increasing number of “knowledge” sources, there are many opportunities beyond professional and research sources from which to develop topics. For example, reliable blogs, webinars, and listservs contain ideas and exchanges that can spark inquiry and lead to relevant contemporary topics. Collaboration in practice, in formal study, and in professional discussions may also yield topical areas to pursue.

Framing a Research Problem

So now you have some idea as to where and how to identify a topic. Foremost, the topic area must be of keen interest to you because you will be spending a lot of time and energy reading and thinking about it. However, you still face the dilemma of identifying a particular problem within a broad topic area. An endless number of problems or specific issues can emerge from any one topic. Thus, the challenge to the researcher is to identify just one particular area of concern or specific research problem. A specific research problem provides some boundary to the area to be studied. It identifies the specific phenomenon to be explored, the reason it needs to be examined, and the reason it is a problem or issue. The way in which you frame and state the problem is critical to the entire research endeavor and influences all subsequent thinking and action processes; that is, the way a problem is framed determines the way it will be answered and the way the knowledge generated can be used. Therefore, this first research step should be thought through very carefully.

The questions we pose in Box 4-3 are designed to help guide your thinking as you move from selecting a broad topic area to framing a concrete research problem. By answering these reflective questions, you will begin to narrow your focus and hone in on a researchable problem.

Interest, Relevance, and Need

It is important to be certain that the topic you develop is interesting to you. Research, regardless of the framework and type of methodology used, takes time and can consume your thoughts. Additionally, you should be convinced of the relevance and need for the inquiry. If the problem is not challenging, exciting, relevant, and needed, the process can quickly become tedious and lack meaning to you. Researchers must be passionate about their area of work; otherwise, the effort may seem pointless.

Research Purpose

As discussed in Chapter 3, all research is purposeful. We suggest that there are three levels of purpose that each research project addresses. The first level of purpose is professional. Much of the research in health and human services is initiated to determine empirically the need for an intervention program, to inform professional practice, or to examine the extent to which an intervention is efficacious in achieving its outcome.

The second level of research purpose is personal. Researchers often have personal reasons for conducting research, or they choose topics that resonate personally or professionally. Practitioners, administrators, and other health and human service professionals may conduct research for such personal reasons as adding new challenges to their jobs, career advancement, commitment to funding new projects, or a desire for academic collaboration and growth. Furthermore, a topic of interest may reflect a deep personal concern. For example, some researchers who focus on specific diseases choose the disease on the basis of their own family history or encounter with the condition.

The third level of purpose for conducting research is theoretical and methodological, reflecting issues that emerge from the literature (see Chapter 5). For example, in the experimental-type tradition, the researcher may be interested in testing a particular theory related to human behavior or in describing, explaining, or predicting phenomena, as demonstrated in the following examples of purpose statements:

Descriptive. Little is known about depression knowledge and beliefs of diverse older adults. The present study is a descriptive examination of depression knowledge of older adults from three groups: African Americans, Latinos, and Koreans.

Explanatory. Although long-term care has been extensively studied, minimal attention has been directed to the role of formal long-term care in facilitating employment of women with cognitive disabilities. This study examines the relationship between formal long-term care support and employment experiences of women with cognitive disabilities, compared with those who do not receive formal long-term care.

Explanatory. This study, using a relatively large national sample, examines the specific coping strategies that individuals with physical functional difficulties use to manage daily care and how strategies are related to well-being.

Predictive. This study examines changes in family functioning from preinjury to 3 years after pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) and identifies those factors that best predict quality of life 3-years postinjury.

Meta-analysis. The purpose of this study is to understand the overall effect of supportive programs for family caregivers.

In naturalistic designs, the purpose is primarily to understand meanings, experiences, and phenomena as they evolve in the natural setting. The following are examples of purpose statements for different naturalistic designs:

Ethnography. The purpose of this study on deafness is to gain an understanding of families' beliefs about deafness, attitudes toward school and health care professionals, expectations for their children, and communication styles with the deaf child.

Ethnography. The purpose of this study is to gain an understanding of the meaning of providing day-to-day care to a family relative with a chronic illness with the hope that greater understanding of the experience of caregiving will assist health professionals in working together with caregivers.

Phenomenology. The purpose of the study is to develop a structural definition of health as it is experienced in everyday life of individuals with cancer.

Grounded theory. This study explicates the multidimensional relationships that develop between physicians and patients with chronic illness in order to develop a theory of the processes that affect self-care.

Grounded theory. The purpose of the study is to identify processes used by family members to manage the unpredictability elicited by the need for and receipt of a heart transplant, and hence a theory of this transitional period.

Heuristic inquiry. The purpose of this study is to examine and understand the meaning of chronic illness in families, from the perspective of all family members.

Participatory action research. The purpose of this inquiry is to assess service needs, as investigated and defined by service recipients.

Meta-analysis. The purpose of this inquiry is to seek universal themes and comparisons in the meaning of the home environment in supporting individuals with functional challenges in six countries.

Critical theory. This study gives voice to women who are homeless as the basis for understanding their needs and promoting socially just responses to this set of informants.

Integrated designs can have multiple purposes that reflect both research traditions or only one tradition. Consider the following examples in which the purpose in each combines both traditions:

The purpose of this integrated study is to reveal the ways in which elder rural women define health and wellness and then test the accuracy of these definitions in a large cohort of the population.

The purpose of this mixed method study is to reveal the meanings of depression among minority populations and how depression knowledge shapes treatment choices.

Epistemology (Theory of Knowledge)

In addition to problem formulation and study purpose, your theory of knowledge and preferred way of knowing, or epistemology, will also influence either (1) the development of discrete questions that objectify concepts (experimental-type tradition) or a query to explore multiple and interacting factors in the context in which they emerge (naturalistic tradition) or (2) the development of a query that integrates both approaches. The age-old ontological and epistemological dilemmas, respectively, of “what is knowledge?” and “how do we know?” (discussed in Chapter 3) are active and forceful determinants in how a researcher frames a problem. The researcher's preferred way of knowing is either clearly articulated or implied in each problem statement. Reexamine the purpose statements listed in this chapter to determine the investigator's preferred way of knowing that is implicitly assumed.

Resources

Resources represent the concrete limitations of the research world. The accessibility of place, group, or individuals and the extent to which time, money, and other resources are necessary and available to the researcher to implement the inquiry are examples of some of the practical constraints of conducting research. These real-life constraints actively shape the development of the research problem an investigator pursues and the scope of the project that can be implemented.

Summary

The many considerations in framing an inquiry include examining the diverse sources and methods through which investigators identify topics for inquiry. Six questions guide the refinement of a topic into a research problem. These questions organize thinking processes along personal, professional, social, ontological, and practical lines. For example, considering your interest in a research topic is a personal thinking process, whereas assessing existing resources available for conducting a project is a practical thinking process. With regard to the purposive aspects of conducting research, investigators organize their research to meet personal, professional, and methodological goals.

Your preferred way of knowing (epistemology) also plays a key role in framing an inquiry. How a researcher frames a problem has significant implications for the selection of design from the experimental-type tradition, the naturalistic tradition, or an integration of the two, as will be seen in subsequent chapters.

Equipped with an understanding of why and how investigators frame research problems, you are ready to begin the thinking process of examining and critically using literature as a basis for knowledge development.

Examples of topics may include but are not exclusive of posthospital experience, health disparities, health promotion in diverse communities, pain control, community independence, adaptation to functional limitations, drug abuse, hospital management practices, gender differences related to retirement, symptom presentation, health experiences, psychosocial aspects of illness, disablement, or wellness, creativity as a source of coping and wellness, or impact of specific interventions.

Examples of topics may include but are not exclusive of posthospital experience, health disparities, health promotion in diverse communities, pain control, community independence, adaptation to functional limitations, drug abuse, hospital management practices, gender differences related to retirement, symptom presentation, health experiences, psychosocial aspects of illness, disablement, or wellness, creativity as a source of coping and wellness, or impact of specific interventions.