Naturalistic Inquiry Designs

Using the language and thinking processes you learned in Chapter 8, we are now ready to explore naturalistic inquiry in more detail. This chapter highlights 10 specific designs of high relevance to health and human service–related concerns. These designs exemplify the wide variation in the naturalistic tradition, the different ways in which complex social phenomena are tackled, and how researchers working out of different naturalistic traditions organize the “10 essentials” of the research process (see Chapter 2). Although there are other naturalistic inquiry approaches that could be presented, examining these 10 designs will provide the foundational knowledge necessary to understand naturalistic inquiry overall.

First, let us reflect a bit on naturalistic inquiry and what we have learned thus far. Do you remember one of the basic principles of naturalist designs? You may recall our discussions in previous chapters that a fundamental principle of all naturalistic designs is that phenomena occur or are embedded in a context, natural setting, or field. The fundamental thinking process characterizing the research process is induction. As such, research processes are implemented and unfold in the identified context through the course of conducting fieldwork. Fieldwork refers to the basic activity that engages all investigators who work in the naturalistic tradition. In conducting fieldwork, the investigator enters an identified setting to experience and understand it without artificially altering or manipulating conditions. The purpose is to observe, understand, and come to know so that theory may be described, explained, and generated. This principle is essential to all naturalistic designs, but the way in which investigators come to know, describe, and explain phenomena differs among designs. That is, although each design shares the basic language and thinking processes discussed in Chapter 8, each design is also based in its own distinct philosophical tradition. As such, these designs differ in purpose, sequence, and investigator involvement (Box 10-1).

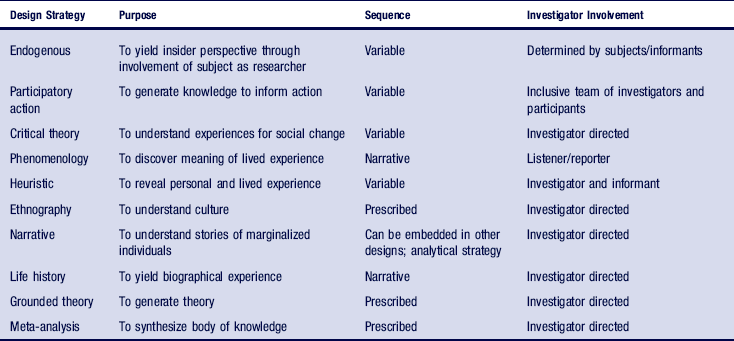

This chapter provides the basic framework of the 10 designs that have great methodological value for naturalistic inquiry in health and human services: endogenous, participatory action, critical theory, phenomenology, heuristic, ethnography, narrative, life history, grounded theory, and meta-analysis. Table 10-1 summarizes how these naturalistic designs compare in purpose, sequence, and investigator involvement. Remember as you read that the sequence by which the 10 essential thinking and action processes are applied is not fixed. Therefore, the essentials cannot be prescribed a priori for each of these 10 naturalistic designs.

Endogenous research

Endogenous research represents the most open-ended approach to research in the naturalistic tradition. This research is “conceptualized, designed, and conducted by researchers who are insiders of the culture, using their own epistemology and their own structure of relevance.”1 The unique feature of this design is the nature of investigator involvement. The investigator relinquishes control of a research plan and its implementation to those who are the target for or “subjects” of the inquiry. The “subjects” are primary investigators or co-investigators who work independently or with the investigator to determine the nature of the study and how it is to be shaped. The “subjects” and investigators make decisions about and participate in the building and testing of information as it emerges. Thus, in this type of research, the subject becomes a full participant in the process.

Endogenous research can be organized in a variety of ways and may include the use of any research strategy and technique in the naturalistic or experimental-type tradition or an integrated design. What makes endogenous research naturalistic is not its investigative structure but rather its paradigmatic framework; that is, the investigator views knowledge as emerging from individuals who know the best way to obtain information. Endogenous design is consistent with the contemporary notion of “emancipatory research,” a relatively new design category.2 It is also consistent with community-based participatory research and participatory action research, described later, which emphasize the importance of involving members in the community of interest in each research step, from query formulation to data collection and analysis.

These approaches as exemplified by endogenous research reject the traditional notion of individuals as research “subjects.” Rather, it views individuals as liberated not only as participants in investigator-facilitated inquiry but also as leaders in the generation and use of knowledge. The endogenous approach is based on a basic proposition developed by the social psychologist Kurt Lewin, as Argyris and Schon explained:

Causal inferences about the behavior of human beings are more likely to be valid and enactable when the human beings in question participate in building and testing them. Hence it aims at creating an environment in which participants give and get valid information, make free and informed choices (including the choice to participate), and generate internal commitment to the results of their inquiry.3

This design gives “knowing power” exclusively to the persons who are the participants of the inquiry. Thus, the endogenous approach is characterized by the absence of any predefined truths or structures. Because endogenous research is conducted by insiders, no external principles guide the selection of thought and action processes in the study itself. Also, because the researcher’s involvement is determined by the individuals who are the “subjects” of the investigation, the researcher may participate as an equal partner, or not at all, or somewhere between these two levels.

So how exactly does an endogenous design approach work? Let us examine a classic example of endogenous research on prison violence.

As you can surmise from this example, the investigator’s concerns in the endogenous research design include how to build and work with a team, how to relinquish control over process and outcome, and how to shape the group process to move the research team along in the study of themselves. These concerns rise from the nature of endogenous research and are distinct from other approaches.

Participatory action research

Participatory action research broadly refers to different types of action research approaches. These varied approaches to action research each reflect a different epistemological assumption and methodological strategy. However, all are “participative, grounded in experience, action-oriented,”4 and are founded in the principle that those who experience a phenomenon are the most qualified to investigate it. Similar to endogenous research, participatory action research involves individuals as first-person, second-person, and third-person4 participants in designing, conducting, and reporting research. By “first-person research,” we mean that individuals who experience the phenomenon of interest systematically reflect on their own lives. “Second-person research” refers to the initiation of an inquiry by a researcher who then branches out to collaborate directly with individuals and communities about a shared problem. In “third-person research” the collaborative nature is still essential, but the direct interaction between researcher and collaborator is not present. Communication takes place through other venues, such as written formats and reports.4 Consistent with others, we believe that the ideal participatory action inquiry includes all three perspectives and approaches.

The purpose of action research is to generate knowledge to inform responsive action. Researchers using a participatory framework usually work with groups or communities experiencing issues and needs related to health and welfare, disparities in health and access to health care, elimination of oppression and discrimination, equal opportunity, and social justice.

The concept of action research was first developed in the 1940s by Lewin, who blended experimental-type approaches to research with programs that addressed critical social problems. Social problems served as the basis for formulating a research purpose, question, and methodology. Therefore, each research step was connected to or involved with the particular organization, social group, or community that was the focus of inquiry and that was affected in some way by the identified problem or issue. More recently, others have expanded this approach to inquiry. The action research design is now used in planning and enacting solutions to community problems and service dilemmas.5

Action research is based on four principles or values (Box 10-2). The principle of democracy means that action research is participatory; that is, all individuals who are stakeholders in a problem or issue and its resolution are included in the research process. Equity ensures that all participants are equally valued in the research process, regardless of previous experience in research. Liberation suggests that action research is a design that is aimed at giving the power of inquiry to participants themselves, decreasing oppression, exclusion, and/or discrimination. Life enhancement positions action research as a systematic strategy that promotes growth, development, and fulfillment of participants of the process and the community they represent.

Participatory action research uses thinking and action processes from the experimental-type or naturalistic tradition or an integration of the two. Similar to endogenous design, there is no prescribed or uniform design strategy. Nevertheless, action research is consistent with naturalistic forms of inquiry in that all research occurs within its natural context. Also, most action research relies on action processes that are characteristically interpretive in nature.6

Let us examine the sequence in which the 10 research essentials are followed in a participatory action research study. Action research is best characterized as cyclical, beginning with the identification of a problem or dilemma that calls for action, moving to a form of systematic inquiry, and culminating in planning and using the findings of the inquiry. Each step is informed or shaped by the participants of the study. The purpose of the following participatory action study was to establish community programs to enhance the transition of adolescents with special health care needs from high school to work or higher education.7

Note that all members of the team were valued and contributed equally to the design, implementation, analysis, and application of the research.

Participatory action research is now used for many purposes, often involving advocacy for underserved groups. The pragmatic foundation combined with its democratic values render action research a useful tool for identifying, empirically supporting, and assessing needed change.

Critical theory

Critical theory is not a research method but a “worldview” that suggests both an epistemology and a purpose for conducting research. The debate continues on whether critical theory is a philosophical, political, or sociological school of thought. In essence, critical theory is a response to post-Enlightenment philosophies and positivism in particular. Critical theorists “deconstruct” the notion that there is a unitary truth that can be known by using one way or method.

We believe critical theory is a movement best understood by philosophers. Because critical theory is inspired by diverse schools of thought, including those informed by Marx, Hegel, Kant, Foucault, Derrida, and Kristeva, it is not a unitary approach. Rather, critical theory represents a complex set of strategies that are united by the commonality of sociopolitical purpose.8

Critical theorists seek to understand human experience as a means to change the world.9 The common purpose of researchers who approach investigation through critical theory is to come to know about social justice and human experience as a means to promote local change through global social change.

Critical theory was born in the Social Institute at the Frankfurt School in the 1920s. As the Nazi party gained power in Germany, critical theorists moved to Columbia University and developed their notions of power and justice, particularly in response to the hegemony of positivism in the United States. With a focus on social change, critical theorists came to view knowledge as power and the production of knowledge as “socially and historically determined.”10 Derived from this view is an epistemology that upheld pluralism, or a coming to know about phenomena in multiple ways. Furthermore, “knowing” is dynamic, changing, and embedded in the sociopolitical context of the times. According to critical theorists, no one objective reality can be uncovered through systematic investigation. Critical theorists and those who build on their work are frequently concerned with language and symbol as the vehicle through which to uncover multiple meanings and to examine power structures and their interactions.11

Critical theory is consistent with fundamental principles that bind naturalistic strategies together in one grand category, such as a view of informant as knower, the dynamic and qualitative nature of knowing, and a complex and pluralistic worldview. Furthermore, critical theorists suggest that research crosses disciplinary boundaries and challenges current knowledge generated by experimental-type methods. Because of the radical view posited by critical theorists, the essential step of literature review in the research process is primarily used as a means to understand the status quo. Thus the action process of literature review may occur before the research, but the theory derived is criticized, deconstructed, and taken apart to its core assumptions. The hallmark of critical theory, however, is its purpose of social change and empowerment of marginalized and oppressed groups. Critical theory relies heavily on interview and observation as methods through which data are collected. Strategies of qualitative data analysis are the primary analytical tools used in critical research agendas (as discussed in Chapter 20).

Phenomenology

The specific focus of phenomenological research is the explication, narrative presentation, and interpretation of the meaning of lived experiences. Phenomenology differs from other forms of naturalistic inquiry in that phenomenologists believe that meaning can be understood only by those who experience it. In many other forms of naturalistic inquiry, the researcher attributes meaning to experience in the analytical phases of the inquiry. In contrast, however, phenomenologists do not impose an interpretive framework on data but look for it to emerge from the information they obtain from their informants. Phenomenological research is further anchored in the principle that the methods by which we share and communicate experience are limited. “The phenomenon we study is ostensibly the presence of the other, but it can only be the way in which the experience of the other is made available to us.”13

The primary data collection strategy used in this design is the telling of a biographical story or narrative with emphasis on eliciting experience as it relates to time, body, and physical and virtual space, as well as to other persons. For example, in eliciting experience, the phenomenologist will ask such questions as, “What is it like to be a patient with breast cancer?” “What was the day like when you learned of your diagnosis?” “What is it like for you to live with breast cancer?” and “What does it mean to you to tell others about your diagnosis?” The elicitation of the ways in which people experience a particular phenomenon differs from other approaches, such as life history. In phenomenology, it is the informant who interjects the primary interpretation and analysis of experience into the interview rather than, as in life history research, the investigator, who imposes an interpretative structure.

How do phenomenologists use literature review? Literature review is framed by the phenomenological principle of the “limits of communication.” Thus, the literature may be used to illustrate the constraints of our understanding of human experience or to corroborate the communication of the other. It may also support the experiences that emerge from informants.

In phenomenological research, involvement by the researcher is limited to eliciting life experiences and hearing and reporting the narrative perspective of the informant. Active interpretive involvement during data collection is not typically part of the investigator’s role.14,15

Heuristic research

Heuristic research is another important design in the naturalistic tradition. According to Moustakas, heuristic research is an “approach which encourages an individual to discover, and methods which enable him to investigate further by himself.”16

The heuristic design strategy involves complete immersion of the investigator into the phenomenon of interest, including the use of self-reflection of the investigator’s personal experiences as primary data. The investigator engages in intensive observation of and listening to individuals who have experienced the phenomenon of interest, recording their individual experiences. The investigator then interprets and reports the meanings of these experiences.

The premise of the heuristic approach is that knowledge emerges from personal experience and is revealed or known to the investigator through his or her own experience of the phenomenon. Thus, investigator involvement in heuristic design is extensive and pervades all areas of inquiry, from the formulation of the query to the collection of data from the investigator as an informant.

Moustakas’s classic work provides an excellent example of heuristic research.

This example illustrates how heuristic research is conducted by an individual for the purpose of discovery and understanding of the meaning of human experience. The research involves total immersion in the experience of humans, including that of the investigator, as a way to understand their perspectives. The experiences of the researcher and the information derived from a literature review are considered primary and critical sources of data. Note the sequence and blurring of the 10 essentials in which the literature review is a source of data and is synthesized with other data sources (see Table 2-1). The term “heuristic” suggests that this form of inquiry serves as a foundation for further inquiry into the human experience that it describes.

Ethnography

Ethnography is a research methodology primarily derived from the discipline of anthropology, although it is informed by many schools of thought.17–22 Ethnography is a term often used to refer to any type of naturalistic inquiry involving field activity. Although different forms of naturalistic inquiry use fieldwork as a basis for data collection, not all fieldwork represents ethnography.23

The intent of ethnography is to understand the underlying patterns of behavior and the meanings of a culture. There are many definitions of culture. For our purposes, we view “culture” as the set of explicit and tacit rules, symbols, and rituals that guide patterns of human behavior within a group. The ethnographer, as an “outsider” to the cultural scene, seeks to obtain an “insider” perspective. Through extended observation, immersion, and participation in the culture, the ethnographer seeks to discover and understand rules of behavior.17 Data are collected by interviewing and observing those willing to inform the researcher about behavioral norms and their meanings, participating in the culture, and examining the meaning of cultural objects and symbols. Insiders who willingly engage with the investigator are called “informants.” Informants are the investigator’s “finger on the pulse of the culture,” without whom the investigator would not be able to achieve full understanding. Although the results of ethnography are specific to the culture being studied, some ethnographers attempt to contribute to a broad theory of universal human experience through this important naturalistic methodology.

Ethnography begins by using a range of techniques to gain access to a context or cultural group. After the investigator enters the field, he or she devotes initial activity to characterizing the context or “social scene”17 by observing the environment in which the culture operates. Equipped with an understanding of the cultural context, the ethnographer uses participant and nonparticipant observation, interview, and examination of materials, texts, or artifacts to obtain data. Through field notes, voice recordings, and video recordings, qualitative data are logged.24 Analysis of the data is ongoing and moves from description to explanation, to revealing meaning, to generation of theory. Impressions and findings are verified with the insiders and reported once the findings are determined to represent the culture accurately. Reflexive analysis, or the analysis of the extent to which the researcher influences the results of the study, is an active component of the research process.23,25 These processes are described in more detail in Chapters 15 and 20.

We classify ethnography as a naturalistic design because of its reliance on qualitative data collection and analysis, the assumption that the researcher is not the knower, and the absence of a priori theory, or a theory imposed before entering the field. In this design, investigator involvement is significant and guides the sequence and conduct of the 10 essential thinking and action processes. It is the investigator who makes the decisions regarding the “who, what, when, and where” of each observation and interview experience. The belief that knowledge can be generated about the “other” without the viewpoint of the investigator influencing the study is a different philosophical approach from heuristic and endogenous designs. Furthermore, ethnography is a design that is capable of moving beyond description to reveal complex relationships, patterns, and theory.8

Since the 1980s, contemporary ethnography has emerged and become increasingly integrated in the conduct of health and human service inquiry. Contemporary ethnographic approaches depart from some of the basic assumptions and design elements of classic ethnography. As described by its proponents, Josselson and Lieblich explained: “Where the older ethnography cast its subjects as mere components of social worlds, new ethnography treats them as active interpreters who construct their realities through talk and interaction, stories, and narrative…. What is ‘new’ about this is the sense that participants are ethnographers in their own right.”26

The new ethnography challenges the basic assumptions held by classic ethnographers, such as investigator objectivity and objective presentation of the social setting.27 The new concern is how best to represent the participants’ own perspectives and their ways of explaining their lives. The focus is on the interpretive practices of people themselves, or how people make sense of their lives as reflected in their own words, stories, and narratives. These concerns are similar to those of the phenomenological and life history approaches. Ethnography is changing in other ways as well. For example, Ulichny25 discussed a critical ethnography in which ethnographical thinking and action processes are applied to social change. The purposes and action processes of contemporary ethnography are becoming much more diverse, in contrast to classic ethnography. Nevertheless, one key element continues to “bound” all forms of ethnography: the examination of cultural and social groups and underlying patterns and ways of experiencing a social context.

Health and human service investigators increasingly turn to ethnography to obtain an insider’s perspective on the meaning of health and social issues as a basis from which to develop meaningful health care and social service interventions or to promote policy and social change. Ethnography has also been used to understand various service environments. One example is the classic ethnography of a nursing home conducted by Savishinsky.28 Several data collection strategies, including interview and participant observation, were used to describe the culture of the nursing home and the meaning of life in that setting. Through analysis and synthesis of the perspectives of residents and staff, Savishinsky was able to identify ways to change that environment to improve the quality of life of the residents.

Narrative inquiry

The many definitions of and approaches to narrative inquiry all have the common element of “storytelling.”29 The storytelling may be autobiographical, biographical, testimonial, or in another form. Thus, narrative is a spoken, written, or visual story30,31 that can be presented in various discursive formats, serves multiple purposes, and can be approached in diverse analytical and interpretive ways.8 Narrative inquiry is frequently used to illuminate the voices and experiences of marginalized or excluded populations and individuals, although this is not its only purpose. Because of the complexity and extensive detail, narrative data provide rich description and reveal meanings embedded not only in the content of the story but also in the words and images (symbols) used to tell the story.32

Remember the primacy of language, communication, text, and image in contemporary naturalistic traditions. Narrative has become one of the most popular postmodern methods because it yields a contextually embedded text or set of images that can be subjected to multiple interpretations and discursive analysis. The view of language as a dynamic, embedded human phenomenon drives the analysis of multiple and reciprocal meanings that can be ascertained through examining the symbolic, tacit, deconstructive, and nonneutral nature of the data.33

Narrative has also been used for clinical purposes, such as therapeutic use of autobiography and biography. The power of story in healing has been highlighted in numerous scholarly works.34–36

The methods to obtain narrative data are diverse. Interviewing and recording (audio or video) are among the information-gathering strategies used most frequently in health and human services to collect narrative data. Photography,37 drawing, painting, creative nonfiction, autobiography, and co-constructed narrative38 are other methods used to tell and present the “story.” Selecting the methods for collecting information are first purposive39 and then practical in nature. In the previous example, interview provided the forum through which to hear the voices of the informants. But what if you were interested in examining the discursive power in the client–provider relationship? You might turn to video and audio recording, because discursive analysis would be focused on the tacit rules of relationships and social activity. In the recordings, you would then look for how these unspoken rules of communication and behavior were illustrated in the interaction between those observed.

In Chapter 20, we discuss the basic analytical action processes used in the naturalistic tradition. These same strategies are used for narrative analysis.40 From a data set, inductive analysis is used to reveal the themes, patterns, and meanings that emerge from storytelling.

It is important to keep in mind that many health and human service professionals and those who influence policy, funding, education, and practice have typically been educated to value knowledge that has been generated from experimental-type inquiry.8 Therefore, investigators who choose narrative strategies for inquiry must be sure to explain adequately its value and purpose and report their narrative in a “clinically convincing” way (Box 10-3).

Although some claim that narrative can generate theory,34 we do not view this as its primary purpose. Narrative strategies typically employ small numbers of informants in the creation of stories that illuminate underlying processes and meanings of experiences.

Life history

Life history, another important design in naturalistic inquiry, uses a narrative strategy. Life history, also called “biography of life narrative,” is an approach that can stand by itself as a legitimate type of research study, or it can be an integral part of other forms of naturalistic inquiry, such as ethnography. The life history approach is a part of the naturalistic tradition because of its focus on examining the social, cultural, and political context of individual lives. Similar to other designs such as phenomenology, the investigator is primarily concerned with eliciting life experiences and with how individuals themselves interpret and attribute meanings to these experiences.

The aim of life history research is to reveal the nature of the “life process traversed over time.”41 The assumption is that individual lives are unique. These unique life processes are important to examine to understand the context in which people live their lives. Researchers who use a life history approach therefore focus on one individual at a time. A study may be composed of just one individual or a few individuals.

There are many diverse purposes for using a life history approach. A life history might be used to explicate the impact of major sociopolitical events on individual lives,42 the processes of developing an identity growing up with a physical impairment, or the unfolding of self-esteem as women age. Depending on the aim of inquiry, life history researchers sequence the essential action processes and use literature in diverse ways. Investigators who attempt to analyze the value of theory in explaining the complexity of a human life may begin with literature review and use it as an organizing framework. Researchers who seek new theoretical understandings, however, may conduct literature review at different junctures in the research thinking and action processes.

Life history research involves a particular methodological approach in which the sequence of life events is elicited and the meaning of those events examined from the perspective of the informant within a particular sociopolitical and historical context.42 In eliciting events, the researcher seeks to uncover and characterize marker events, or “turnings,” defined as specific occurrences that shape and change the direction of individual lives.43 Typically, researchers rely heavily on unstructured interviewing techniques. The research may begin with asking an informant to describe the sequence of life events from childhood to adulthood. On the basis of a time line of events, the investigator may ask questions to elicit the meanings of these events. Participatory and nonparticipatory observation may also be combined with the interview as data collection strategies to examine meanings and understand how life is experienced.

Although life history relies mostly on the person who tells his or her story, the investigator shapes the story in part by the types of questions asked. For example, the researcher may ask more detailed questions about a particular life event than is initially offered by the participant. This probing by the researcher structures, in effect, the telling of the story to fit the interests or concerns of the researcher.

Life history studies can be retrospective or prospective. In health and human service research, it is not surprising, in light of practical constraints, that the majority of life history studies are retrospective in their approach; that is, informants are asked to reconstruct their lives and reflect on the meaning of past events. Prospective life histories would rely on the investigator’s ability to devote significant time to the observation and analysis of meaning as an individual traveled through chronological time.

Grounded theory

Grounded theory is defined as “the systematic discovery of theory from the data of social research.”21 It is a more structured and investigator-directed strategy than the previous naturalistic designs that we have thus far discussed.

Developed by Glaser and Strauss,22 grounded theory represents the integration of a quantitative and qualitative perspective in thinking and action processes. The primary purpose of this design strategy is to evolve or “ground” a theory in the context in which the phenomenon under study occurs. The theory that emerges is intimately linked to each datum of daily life experience that it seeks to explain.

This strategy is similar to other naturalistic designs in its use of an inductive process to derive concepts, constructs, relationships, and principles to understand and explain a phenomenon. However, grounded theory is distinguished from other naturalistic designs by its use of a structured data-gathering and analytical process called the constant comparative method. In this approach, each datum is compared with others to determine similarities and differences. Researchers have developed an elaborate scheme by which to code, analyze, recode, and produce a theory from narratives obtained through a range of data collection strategies.22,44

Let us briefly consider how you might use grounded theory.

The purpose of the constant comparative method is not only to reveal categories but also to explore the diversity of experience within categories, as well as to identify links among categories.

Grounded-theory strategies can also be used to generate and verify theory.22 A query using a grounded-theory approach begins with broad descriptive interests and then, through data collection and analysis, moves to discover and verify relationships and principles.

Naturalistic meta-analysis

Now we turn to another approach, naturalistic meta-analysis, which seeks to aggregate small and disparate data sets from which to derive a global synthesis.46 Meta-analysis is a research approach in which multiple independently conducted studies are synthesized and analyzed as a single data set to answer a research question or query. Naturalistic meta-analysis is the application of naturalistic methods to the analysis of many studies. Interestingly, naturalistic meta-analysis is not restricted to the analysis of naturalistic studies. Rather, this approach to meta-analysis is characterized by the philosophical perspective that underpins naturalistic inquiry and the use of inductive methods of analysis applied to multiple studies, literature, and theory.

There are many purposes of naturalistic meta-analysis.47 Similar to experimental-type meta-analysis (see Chapter 9), some naturalistic meta-analyses seek to identify and summarize a universe of studies on a particular topic. In anthropology, however, meta-ethnography48 has been used interpretively to reveal global themes and patterns.8 The Qual-Quan Evidence Synthesis Group seeks to establish “rigor” standards for naturalistic meta-analysis to contribute to evidence-based practice in health care. This group suggests that meta-analytic approaches are valuable in reviewing diverse perspectives and findings as the basis for deriving single definitions and understandings of complex constructs (e.g., quality, satisfaction).49

The thinking and action processes of naturalistic meta-analysis follow the processes that you would use in any naturalistic study. The difference, however, is that your data set comprises studies already conducted and existing sources of literature, theory, and other data sources. Thus, you are aggregating and conducting a secondary analysis of existing knowledge from the perspective of naturalistic inquiry.

If we apply the elements of naturalistic inquiry to existing sources, we begin to see how meta-analysis might be approached from this perspective. First, we need to specify a query or queries that conceptually “bound” a study and provide guidance for seeking sources for analysis. Remember that after the queries are articulated, they can undergo modification as the data sources are initially reviewed and analyzed. In meta-analysis, the analogous step to gaining access to the field is deciding which sources to access first. In concert with the thinking and action processes of naturalistic inquiry, data collection and analysis are concurrent and ongoing, and the investigator modifies the inquiry in response to the analysis and emerging findings. Final analysis and reporting to audiences occur after saturation occurs with the data set. Let us consider the investigator who is interested in characterizing the experience of AIDS.

Naturalistic meta-analysis can be an extremely valuable methodology for health and human service researchers. This approach provides the tools to reveal consensus on competing theories and research, to arrive at single definitions of complex constructs, and to illuminate important themes and patterns across large bodies of literature.

Summary

The 10 design strategies discussed in this chapter differ in their purpose, the sequencing of the essentials of research, and the nature of the investigator’s involvement. Naturalistic designs are flexible in the degree to which the investigator participates in the formulation of the design, data collection, and interpretive analysis. Moreover, the sequences of the 10 essential thinking and action processes vary, and boundaries between these processes, such as data collection and analysis, which are clearly delineated in experimental-type designs, may be blurred in naturalistic inquiry.

With this introduction to 10 frequently used designs in the naturalistic tradition, you may want to explore each in greater depth by following up with the references to this chapter.

References

1. Maruyama, M. Endogenous research: the prison project. In: Reason P., Rowan J., eds. Human inquiry: a sourcebook of new paradigm research. New York: Wiley & Sons, 1981. [p 270].

2. Barners, C., Mercer, J.T. Doing disability research. Leeds, United Kingdom: Disability Press, 1998.

3. Argyris, C., Schon, D.A. Participatory action research and action science compared: a commentary. In: Whyte W.F., ed. Participatory action research. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 1991. [p 433].

4. Reason P., Bradbury H., eds. Handbook of action research: participative inquiry and practice. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2001. [p xxiv].

5. Whyte W.F., ed. Participatory action research. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 1991.

6. Stringer, E.T. Action research: a handbook for practitioners. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 1996.

7. DePoy, E., Gilmer, D., Martzial, E. Adolescents with disabilities and chronic illness in transition: a community action needs assessment. Disability Stud Q. 2000;20:34–57.

8. Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S. Sage handbook of qualitative research, ed 3. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2003.

9. Rodwell, M. Social work constructivist research. New York: Garland, 1998.

10. Tierney, W. Culture and ideology in higher education. New York: Praeger, 1991.

11. Macey, D. Penguin dictionary of critical theory. Penguin Books, 2002.

12. Nencel, L., Pels, P. Constructing knowledge: authority and critique in social science. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 1991.

13. Darroch, V., Silvers, R.J. Interpretive human studies: an introduction to phenomenological research. Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1982. [p 4].

14. Van Manen, M. Researching lived experience: human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1990.

15. Douglas J., ed. Understanding everyday life. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970.

16. Moustakas, C. Heuristic research. In: Reason P., Rowan J., eds. Human inquiry: a sourcebook of new paradigm research. New York: Wiley & Sons, 1981.

17. Spradley, J.P. Participant observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1980.

18. Sperber, D. On anthropological knowledge. Cambridge, Mass: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

19. Levi-Strauss, C. Structural anthropology. New York: Basic Books, 1960. [(Jacobson C, Schoepf BG, translator)].

20. Agar, M. Speaking of ethnography. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 1986.

21. Geertz, C. The interpretation of cultures: selected essays. New York: Basic Books, 1973.

22. Glaser, B., Strauss, A. The discovery of grounded theory. New York: Aldine, 1967.

23. Bogden, R.C., Biklen, S.N. Qualitative research for education. Boston: Allyn Bacon, 1992.

24. Lofland, J., Lofland, L. Analyzing social settings: a guide to qualitative observation and analysis, ed 2. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth, 1984.

25. Ulichny, P. When critical ethnography and action collide. Qualitative Inquiry. 1997;3:139–168.

26. Josselson, R, Lieblich, A. Interpreting Experience: The Narrative Study of Lives. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1995. [p 46].

27. Agar, M.H. The professional stranger: an informal introduction to ethnography, ed 2. San Diego: Academic Press, 1996.

28. Savishinsky, J.S. The ends of time: life and work in a nursing home. New York: Bergen & Garvey, 1991.

29. Seale, C. Resurrective practice and narrative. In: Andrews M., Sclater S.D., Squire C., Treacher A., et al, eds. Lines of narrative. London: Routledge, 2000.

30. The Centre for Narrative Research, http://www.uel.ac.uk/cnr/index.htm. [Accessed April 1, 2010].

31. Ryan, M.L. On defining narrative media. Image Narrative. 2003;6:57–68.

32. Silverman, D. Doing qualitative research: a practical handbook, ed 2. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2004.

33. Abell, J., Stokoe, E., Billig, M. Narrative and the discursive (re)construction of events. In: Andrews M., Sclater S.D., Squire C., Treacerh A., eds. Lines of narrative. London: Routledge, 2000.

34. Squire, C. Centre for narrative research, school of social sciences. University of East London, 2004. [Available at www.uel.ac.uk/cnr/documents/Newsletter5April2004.doc].

35. Crossley, M. Introducing narrative psychology: self, trauma and the construction of meaning. Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom: Open University Press, 2000.

36. Labov, W., Fanshel, D. Therapeutic discourse: psychotherapy as conversation. New York: Academic Press, 1977.

37. Bell, S. Photo images: Jo Spence’s narratives of living with illness. Health. 2002;6:5–30.

38. Bochner, A.P., Ellis, C. Ethnographically speaking. Lanham, Md: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002.

39. Patterson W., ed. Strategic narrative. New York: Lexington, 2002.

40. Labov, W., Waletsky, J. Narrative analysis. In: Helm J., ed. Essays on the verbal and visual arts. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1967.

41. Rabin, A.I., Rabin, A.I., Zucker, R.A., et al. Studying persons and lives. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1990. [p ix].

42. Mkhonza, S. Life histories as social texts of personal experiences in sociolinguistic studies: a look at the lives of domestic workers in Swaziland. In: Josselson R., Lieblich A., eds. Interpreting experience: the narrative study of lives. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 1995.

43. Frank, G. Life history model of adaptation to disability: the case of a congenital amputee. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19:639–645.

44. Strauss, A., Corbin, J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 1998.

45. Butler, S. Homeless women. Seattle: University of Washington, 1991. [Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation].

46. Basu, A. How to conduct a meta-analysis http://www.pitt.edu/~super1/lecture/lec1171/001.htm.

47. Potts, A., Boler, M., Hicks, D., et al. Qualitative meta-analysis for social justice: the creation of an on-line diversity resources database. Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, 2004:832–836. http://dl.aace.org/14388. [Accessed April 1, 2010].

48. Noblitt, G.W., Hare, R.D. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 1988.

49. Qual-Quan Evidence Synthesis Group, http://www.prw.le.ac.uk/research/qualquan/publications.htm. [Accessed April 1, 2010].

Maruyama entered the prison environment as a collaborator and participant observer rather than as the research consultant, an important characteristic of endogenous research. As a collaborator, Maruyama deferred to the subjects of the investigation to determine the degree of investigator involvement. Two teams, composed of prisoners who had no formal education in research methods, held a series of group meetings and created purposes and plans of action that were important and meaningful to each group. Maruyama described the research in this way: “A team of endogenous researchers was formed in each of the two prisons. The overall objective of the project was to study interpersonal physical violence (fights) in the prison culture, with as little contamination as possible from academic theories and methodologies. The details of the research were left to be developed by the inmate researchers.”

Maruyama entered the prison environment as a collaborator and participant observer rather than as the research consultant, an important characteristic of endogenous research. As a collaborator, Maruyama deferred to the subjects of the investigation to determine the degree of investigator involvement. Two teams, composed of prisoners who had no formal education in research methods, held a series of group meetings and created purposes and plans of action that were important and meaningful to each group. Maruyama described the research in this way: “A team of endogenous researchers was formed in each of the two prisons. The overall objective of the project was to study interpersonal physical violence (fights) in the prison culture, with as little contamination as possible from academic theories and methodologies. The details of the research were left to be developed by the inmate researchers.”