Setting the Boundaries of a Study

Assume that you have a research problem and an appropriate design that matches your research purpose and question or query. You are now ready to consider how individuals, concepts, or locations will be selected for your study and how particular

phenomena will be defined and identified. Selecting research participants, whether they are human or not, and identifying concepts and phenomena represent one of the first action processes that set or establish the boundaries or limitations of a study.

Setting boundaries is inextricably linked to important ethical considerations, such as how people are selected for study participation, how they are informed of study procedures, how the information they share is managed and treated confidentially, and to whom or what the study results are applied. Because of the significance of the ethical component of boundary setting, we examine this in depth in Chapter 12.

Why set boundaries to a study?

Setting limits or boundaries as to what and who will be in a study is an action that occurs in every type of research design, whether in the experimental-type or the naturalistic tradition. A researcher sets boundaries that limit the scope of the investigation to a specified group of individuals, phenomena, geography, or set of conceptual dimensions. The following example helps show why it is important to set boundaries or limitations.

Studies are also necessarily limited or bounded by identifying particular data collection strategies and concepts that will be considered.

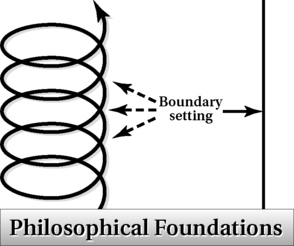

There are numerous ways to limit the scope of a study. As discussed in previous chapters on the thinking processes of research, an investigator actively bounds a study on the basis of five interrelated considerations (Box 11-1).

Your philosophical approach or the particular research tradition you are using to develop your study will set the backdrop from which all action decisions will be made. A deductive, experimental-type study tightly bounds the study to preidentified concepts and a highly specified population. The purpose of the study, the particular research question, and the design will also shape the extent to which concepts, phenomena, and populations are delimited.

For example, an intervention study that tests the effectiveness of a particular home care service in producing a specified outcome must carefully match the intent of the intervention with specific characteristics of the subject group or individuals who will be targeted and recruited for the study. Thus, identifying highly specified criteria as to who is eligible and who is not eligible to participate is a required action process. These criteria are referred to as “inclusion and exclusion criteria,” as discussed later.

On the other hand, a broad inquiry designed to investigate the experiences of persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) may set few restrictions except diagnostic condition as to who can participate in the study and thus cast a wide net for participant enrollment. An investigator might even delimit a study by virtual location such as a listserv or virtual chat room for persons with AIDS.

Finally, your ability to access the population of interest or the phenomenon to be studied is another consideration as to how a study is bounded. Limited resources, such as monetary and time restrictions, will likely yield a study design that is tightly delimited or bounded.

Thus, there are both practical and theoretical considerations in how researchers bound the context of either an experimental-type or a naturalistic form of inquiry. In practical terms, it would be impossible to observe every speech event, personal interaction, image, or activity in a particular natural setting. You must bound the study by making purposeful selections as to what will be observed and who will be interviewed.1,2

In experimental-type designs, boundary setting is a process that must occur before entering the field or beginning the study. Boundaries are set in three ways: (1) specifying the concepts that will be operationally defined, (2) establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria that define the population that will be studied, and (3) developing a sampling plan.

This set of action processes in naturalistic designs differs from those in the experimental-type tradition. Naturalistic boundary setting may occur throughout the research endeavor depending on how the dynamic design unfolds. Initial boundaries are set by the investigator through defining the particular domain of interest and the point of access from which to enter that domain.

Next, within the context of the defined domain, a selection process then occurs as to who should be interviewed and when, what scenes, images, or events to observe, and which materials, texts, or artifacts to review. This selection process occurs or unfolds in the course of performing fieldwork and comprises important boundary-making decisions. Setting boundaries in most forms of naturalistic inquiry can therefore be an ongoing process that moves the researcher from a broad stance to a more narrow focus. The actions of data collection, analysis, and further data collection (see Chapters 17 and 18) can be understood as a process of redefining and refining the boundaries of the phenomenon being studied.

Implications of boundary setting

Bounding a study is a purposeful action process in both research traditions. That is, boundary setting involves making conscious decisions based on a sound rationale that can be documented or articulated to the larger scientific community. The inclusion or exclusion of people, concepts, events, or other phenomena has considerable implications for knowledge development and its translation or use in professional practice. As you make decisions about how to bound your study and then actively set limits, you must reflect on your actions and understand the implications of each boundary-making decision.

One of the most important consequences of researchers' bounding actions is what can ultimately be concluded (or not) about the phenomenon of interest and then applied to whom or what. Within the experimental-type tradition, the ability to generalize from a study sample to the population from which the sample was derived is referred to as external validity.

The same principles hold for defining and operationalizing major constructs.

The consequences of boundary setting are often described in an experimental-type proposal or a research report as “limitations” of the study. As you read research articles in professional journals, take a close look at how authors describe their recruitment process, the inclusion and exclusion criteria that they follow to enroll and engage subjects or other elements (e.g., research reports for meta-analysis, secondary data, etc.) into the study, and how they define and operationalize primary concepts. Also, carefully read how researchers describe the limitations of their study. Finally, look closely at the discussion section of a published article, where the researcher must vigilantly interpret the findings as they relate to specific populations and concepts. Sometimes you will find that researchers overstate their case or stretch their results to include a broader population or set of constructs than was actually studied. They may assert or imply that their findings are not bounded to the studied population or phenomena and draw conclusions for a broader scope than that which was originally included in the study.

The ways in which studies are bounded have particular significance for translating research findings into the professional arena, particularly for evidence-based practice models, as we describe in Chapter 24. For example, in the clinic setting, it is important to know whether a particular technique, intervention modality, or teaching approach is effective in producing a desired outcome for a specific client or patient. If you search the literature to identify the evidence for using a particular intervention, you may find that the published studies involve study participants who may or may not match your clients. You must carefully decide how best to interpret and translate such findings for your particular group. The first step in this translational effort is to recognize the ways in which the studies you have identified are bounded. The second step is to evaluate whether specific characteristics of your group would determine whether the results of the studies are applicable.

Another implication of bounding studies relates to building programs of research. Remember that research involves the incremental construction of knowledge. Each study answers a specified question or query and in turn generates the next steps toward understanding a particular phenomenon. The way in which a study is bounded will have implications for building knowledge and for subsequent research steps.

Specifying the scope of participation: inclusion and exclusion criteria

One of the most important ways a researcher sets limits in a study is determining who or what will be included as well as excluded from participating in the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria developed by an investigator delimit the population (or group) to whom the study results are directly applicable, reflect the underlying purpose of the research endeavor, and reflect the research question.

Experimental-type researchers must establish detailed criteria before recruiting individuals into a study. These criteria are highly specified and are used to identify a population and develop a sampling and recruitment plan. Within the naturalistic tradition, boundaries are fluid and purposive, and who or what is included at the beginning may vary as the study proceeds.

In experimental-type designs, there is a high level of specificity in bounding the study. In contrast, usually only broad inclusion and exclusion guidelines are established before engaging in naturalistic designs. However, the structure and extent to which boundaries are established depend on the particular type of naturalistic design. For example, in a phenomenological study, the researcher may bound a study only by identifying the type of experience that is of interest to the researcher. The only criterion for participating in the study may be that an individual has experienced the phenomenon of interest. Other factors, such as age, gender, or ethnicity, may not be specified or used as criteria to include or exclude individuals from the study. Likewise, in a large-scale ethnography, only the context or natural setting may be initially specified or bounded, whereas the participation of individuals in the natural context may not be restricted, at least initially. In a focused life history, however, individuals who meet specific criteria are selected for study participation, and these criteria are articulated before engaging in fieldwork.

Involving humans in health and social service research and establishing participation criteria have important ethical considerations that must be fully understood and carefully thought out by the researcher. When developing a research study and writing a proposal to carry it out (see Chapter 21), whether of the experimental, naturalistic, or mixed-method type, the researcher must address numerous ethical concerns of involving humans, as examined in Chapter 12.

General guidelines for bounding studies

The extent to which a study is bounded depends on your preferred way of knowing, research purpose, question or query, and practical considerations such as monetary and time constraints. It is important to recognize that there is nothing inherently superior about any one boundary-setting approach. The strengths and limitations of a boundary-setting technique depend on its appropriateness and adequacy in how well it fits the context of the particular research problem.

Appropriateness is defined as the extent to which the method of boundary setting fits the overall purpose of the study, as determined by the research problem, purpose, and the structure of the research design. For example, it would be inappropriate to use a random sampling technique when your purpose is to understand how individuals interpret their experience of illness. In this case, the purposeful selection of individuals who can articulate their feelings may provide greater insight than the inclusion of a sample with predetermined characteristics. Purposeful selection to bound the study facilitates understanding, which is the underlying goal of the study.

Adequacy is defined as the extent to which the boundary setting yields sufficient data to answer the research problem. In experimental-type designs, adequacy is determined by sample size and composition. In naturalistic designs, adequacy is determined by the quality and completeness of the information and the understanding that is obtained in the selected domain. “Saturation” in the field, such as reaching a point in the inquiry in which no new information is obtained, is one important cue that the boundary has been met and the investigator has achieved a complete understanding of the identified context.

Thus, appropriateness and adequacy are two criteria that can be applied to boundary-setting decisions.

Subjects, Respondents, Informants, Participants, Locations, Conceptual Boundaries, Virtual Boundaries

Are individuals who are involved in a study the subjects, respondents, informants, or participants?3 Are you focusing on locations, concepts expressed in text or image, or the virtual world? Subjects, respondents, informants, and participants refer to humans or the individuals who agree to become part of a research study. Each term reflects a different way that an individual participates in a research study and a different type of relationship that is formed between the individual and the investigator. Locations, conceptual boundaries, and virtual boundaries are viable boundaries as well, used to delimit studies in experimental-type, naturalistic, and mixed method approaches.

First, we discuss the distinction among the four terms that describe humans roles in research. In experimental-type research, individuals are usually referred to as subjects, a term that denotes their passive role and the attempt of the investigator to maintain a removed and objective relationship. In survey research, individuals are often referred to as respondents because they are asked to respond to very specific questions. In naturalistic inquiry, individuals are usually referred to as informants, a term that reflects the active role of informing the investigator as to the context and its cultural rules. Participants can refer to those individuals who enter a collaborative relationship with the investigator, who contribute to decision making about the research process, and who inform the investigator about themselves. This term is often used in endogenous and participatory action research.4

Locations, conceptual boundaries, and virtual boundaries all are terms that are used to denote nonhuman delimiters of a study. Similar to descriptors of humans in a study, these terms overlap as well. For example, suppose you are interested in looking at patterns of intolerance in virtual settings. You would use a conceptual set of boundaries to observe intolerance and virtual location boundaries to limit the study to specific on-site locations.

Although there are no specific rules to guide the use of these terms, you should select the one that reflects your preferred way of knowing and the role that individuals play in your study design.

Summary

Boundary setting refers to the action process of determining and enacting selection criteria for study participants, study concepts, or study phenomena. Setting boundaries represents one of the first action processes that occurs in experimental-type research. In naturalistic inquiry, boundary setting occurs throughout the data collection and analytical action phases and is an ongoing process.

One crucial way in which studies are bounded is developing inclusion and exclusion criteria for the involvement of human participants. Each tradition handles this action process through different structures and timing sequences.

Given the ethical considerations of working with human subjects in an inquiry, protection from risk is a critical consideration (see Chapter 12). Ethical decision making is also critical in how the knowledge from the study will be interpreted and used in professional practice.

References

1. Agar, M.H. The professional stranger: an informal introduction to ethnography, ed 2. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, 1996.

2. Rubin, H.J., Rubin, I.S. Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 1995.

3. Subjects, respondents, informants and participants [editorial]. Qual Health Res. 1991;1:403–406.

4. Reason, P., Bradbury, H. Handbook of action research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2001.

Consider a study that uses a survey design to describe the health and social service needs of “parents of children with intellectual impairments.” It would be impossible to interview every person who falls into this category in the United States. As the researcher, you need to make some decisions as to who you should specifically interview and how. One consideration may be to limit the survey to one or more particular geographic locations. Another way to limit the study may be to consider only certain types of conditions that fall under the rubric of intellectual impairment. Limiting the number of parents of children with intellectual impairments who are selected for study participation is an example of setting a boundary by restricting the characteristics of the persons who will be studied.

Consider a study that uses a survey design to describe the health and social service needs of “parents of children with intellectual impairments.” It would be impossible to interview every person who falls into this category in the United States. As the researcher, you need to make some decisions as to who you should specifically interview and how. One consideration may be to limit the survey to one or more particular geographic locations. Another way to limit the study may be to consider only certain types of conditions that fall under the rubric of intellectual impairment. Limiting the number of parents of children with intellectual impairments who are selected for study participation is an example of setting a boundary by restricting the characteristics of the persons who will be studied.