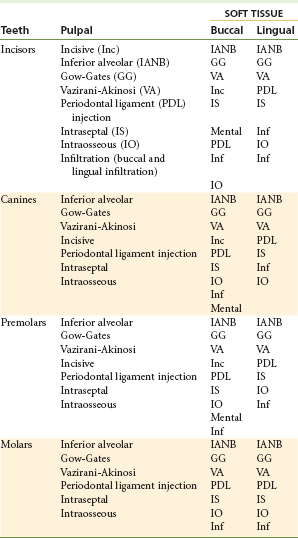

Techniques of Mandibular Anesthesia

Providing effective pain control is one of the most important aspects of dental care. Indeed, patients rate a dentist “who does not hurt” and one who can “give painless injections” as meeting the second and first most important criteria used in evaluating dentists.1 Unfortunately, the ability to obtain consistently profound anesthesia for dental procedures in the mandible has proved extremely elusive. This is even more of a problem when infected teeth are involved, primarily mandibular molars. Anesthesia of maxillary teeth on the other hand, although on occasion difficult to achieve, is rarely an insurmountable problem. Reasons for this include the fact that the cortical plate of bone overlying maxillary teeth is normally quite thin, thus allowing the local anesthetic drug to diffuse when administered by supraperiosteal injection (infiltration). Additionally, relatively simple nerve blocks, such as the posterior superior alveolar (PSA), middle superior alveolar (MSA), anterior superior alveolar (ASA, infraorbital), and anterior middle superior alveolar (AMSA),2 are available as alternatives to infiltration.

It is commonly stated that the significantly higher failure rate for mandibular anesthesia is related to the thickness of the cortical plate of bone in the adult mandible. Indeed it is generally acknowledged that mandibular infiltration is successful in cases where the patient has a full primary dentition.3,4 Once a mixed dentition develops, it is a general rule of teaching that the mandibular cortical plate of bone has thickened to the degree that infiltration might not be effective, leading to the recommendation that “mandibular block” techniques should now be employed.5

A second difficulty with the traditional Halsted approach to the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) (i.e., “mandibular block,” or IANB) is the absence of consistent landmarks. Multiple authors have described numerous approaches to this oftentimes elusive nerve.6-8 Indeed, reported failure rates for the IANB are commonly high, ranging from 31% and 41% in mandibular second and first molars to 42%, 38%, and 46% in second and first premolars and canines, respectively,9 and 81% in lateral incisors.10

Not only is the inferior alveolar nerve elusive, studies using ultrasound11 and radiography12,13 to accurately locate the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle or the mandibular foramen revealed that accurate needle location did not guarantee successful pain control.14 The central core theory best explains this problem.15,16 Nerves on the outside of the nerve bundle supply the molar teeth, while nerves on the inside (core fibers) supply incisor teeth. Therefore the local anesthetic solution deposited near the IAN may diffuse and block the outermost fibers but not those located more centrally, leading to incomplete mandibular anesthesia.

This difficulty in achieving mandibular anesthesia has over the years led to the development of alternative techniques to the traditional (Halsted approach) inferior alveolar nerve block. These have included the Gow-Gates mandibular nerve block,17 the Akinosi-Vazirani closed-mouth mandibular nerve block,18 the periodontal ligament (PDL, intraligamentary) injection,19 intraosseous anesthesia,20 and, most recently, buffered local anesthetics.21 Although all maintain some advantages over the traditional Halsted approach, none is without its own faults and contraindications.

Six nerve blocks are described in this chapter. Two of these—involving the mental and buccal nerves—provide regional anesthesia to soft tissues only and have exceedingly high success rates. In both instances, the nerve anesthetized lies directly beneath the soft tissues, not encased in bone. The four remaining blocks—inferior alveolar, incisive, Gow-Gates mandibular, and Vazirani-Akinosi (closed-mouth) mandibular—provide regional anesthesia to the pulps of some or all of the mandibular teeth in a quadrant. Three other injections of importance in mandibular anesthesia—periodontal ligament, intraosseous, and intraseptal—are described in Chapter 15. Although these supplemental techniques can be used successfully in the maxilla or the mandible, their greatest utility lies in the mandible, because in the mandible, they can provide pulpal anesthesia of a single tooth without providing the accompanying lingual and facial soft tissue anesthesia that occurs with other mandibular nerve block techniques.

The success rate of the inferior alveolar nerve block is considerably lower than that of most other nerve blocks. Because of anatomic considerations in the mandible (primarily the density of bone), the administrator must accurately deposit local anesthetic solution to within 1 mm of the target nerve. The inferior alveolar nerve block has a significantly lower success rate because of two factors—anatomic variation in the height of the mandibular foramen on the lingual aspect of the ramus, and the greater depth of soft tissue penetration necessary—that lead to greater inaccuracy. Fortunately, the incisive nerve block can provide pulpal anesthesia to the teeth anterior to the mental foramen (e.g., incisors, canines, first premolars, and [in most instances] second premolars). The incisive nerve block is a valuable alternative to the inferior alveolar nerve block when treatment is limited to these teeth. To achieve anesthesia of the mandibular molars, however, the inferior alveolar nerve must be anesthetized, and this frequently entails (with all its attendant disadvantages) a lower incidence of successful anesthesia.

The third injection technique that provides pulpal anesthesia to mandibular teeth, the Gow-Gates mandibular nerve block, is a true mandibular block injection, providing regional anesthesia to virtually all sensory branches of V3. In actual fact, the Gow-Gates may be thought of as a (very) high inferior alveolar nerve block. When used, two benefits are seen: (1) the problems associated with anatomic variations in the height of the mandibular foramen are obviated, and (2) anesthesia of the other sensory branches of V3 (e.g., the lingual, buccal, and mylohyoid nerves) is usually attained along with that of the inferior alveolar nerve. With proper adherence to protocol (and experience using this technique), a success rate in excess of 95% can be achieved.

Another V3 nerve block, the closed-mouth mandibular nerve block, is included in this discussion, primarily because it allows the doctor to achieve clinically adequate anesthesia in an extremely difficult situation—one in which a patient has limited mandibular opening as a result of infection, trauma, or postinjection trismus. It is also known as the Vazirani-Akinosi technique (after the two doctors who developed it independent of each other). Some practitioners use it routinely for anesthesia in the mandibular arch. The closed-mouth technique is described mainly because with experience it can provide a success rate of better than 80% in situations (extreme trismus) in which the inferior alveolar and Gow-Gates nerve blocks have little or no likelihood of success.

In ideal circumstances, the individual who is to administer the local anesthetic should be familiar with each of these techniques. The greater the number of techniques at one’s disposal with which to attain mandibular anesthesia, the less likely it is that a patient will be dismissed from an office as a result of inadequate pain control. More realistically, however, the administrator should become proficient with at least one of these procedures and should have a working knowledge of the others to be able to use them with a good expectation of success should the appropriate situation arise.

Recent work with mandibular infiltration in adult patients with the local anesthetic drug articaine HCl has demonstrated significant rates of success in mandibular anterior teeth in lieu of block injection.22-24 When articaine HCl is administered by buccal infiltration in the adult mandible following IANB, success rates are even greater.25,26 The concept of mandibular infiltration in adult patients will be discussed in depth in Chapter 20.

Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block

The inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB), commonly (but inaccurately) referred to as the mandibular nerve block, is the second most frequently used (after infiltration) and possibly the most important injection technique in dentistry. Unfortunately, it also proves to be the most frustrating, with the highest percentage of clinical failures even when properly administered.6-10

It is an especially useful technique for quadrant dentistry. A supplemental block (buccal nerve) is needed only when soft tissue anesthesia in the buccal posterior region is necessary. On rare occasions, a supraperiosteal injection (infiltration) may be needed in the lower incisor region to correct partial anesthesia caused by the overlap of sensory fibers from the contralateral side. A periodontal ligament (PDL) injection might be necessary when isolated portions of mandibular teeth (usually the mesial root of a first mandibular molar) remain sensitive after an otherwise successful inferior alveolar nerve block. Intraosseous anesthesia (IO) is a supplemental technique employed, usually on molars, when the IANB has proven ineffective, primarily when the tooth is pulpally involved.

Administration of bilateral IANBs is rarely indicated in dental treatments other than bilateral mandibular surgeries. They produce considerable discomfort, primarily from the lingual soft tissue anesthesia, which usually persists for several hours after injection (the duration is dependent on the particular local anesthetic used). The patient feels unable to swallow and, because of the absence of all sensation, is more likely to self-injure the anesthetized soft tissues. Additional residual soft tissue anesthesia affects the patient’s ability to speak and to swallow. When possible, it is preferable to treat the entire right or left side of a patient’s oral cavity (maxillary and mandibular) at one appointment rather than administer a bilateral IANB. Patients are much more capable of handling the posttreatment discomfort (e.g., feeling of anesthesia) associated with bilateral maxillary than with bilateral mandibular anesthesia.

One situation in which bilateral mandibular anesthesia is frequently used involves the patient who presents with six, eight, or ten lower anterior teeth (e.g., canine to canine; premolar to premolar) requiring restorative or soft tissue procedures. Two excellent alternatives to bilateral IANBs are bilateral incisive nerve blocks (where lingual soft tissue anesthesia is not necessary) and unilateral inferior alveolar blocks on the side that has the greater number of teeth requiring restoration or that requires the greater degree of lingual intervention, combined with an incisive nerve block on the opposite side. It must be remembered that the incisive nerve block does not provide lingual soft tissue anesthesia; thus lingual infiltration may be necessary. Infiltration of articaine HCl in the mandibular incisor region on both the buccal and lingual aspects of the tooth has been associated with considerable success in providing pulpal anesthesia.22

In the following description of the inferior alveolar nerve block, the injection site is noted to be slightly higher than that usually depicted.

Areas Anesthetized

Disadvantages

1. Wide area of anesthesia (not indicated for localized procedures)

2. Rate of inadequate anesthesia (31% to 81%)

3. Intraoral landmarks not consistently reliable

4. Positive aspiration (10% to 15%, highest of all intraoral injection techniques)

5. Lingual and lower lip anesthesia, discomfiting to many patients and possibly dangerous (self-inflicted soft tissue trauma) for certain individuals

6. Partial anesthesia possible where a bifid inferior alveolar nerve and bifid mandibular canals are present; cross-innervation in lower anterior region

Alternatives

1. Mental nerve block, for buccal soft tissue anesthesia anterior to the first molar

2. Incisive nerve block, for pulpal and buccal soft tissue anesthesia of teeth anterior to the mental foramen (usually second premolar to central incisor)

3. Supraperiosteal injection, for pulpal anesthesia of the central and lateral incisors, and sometimes the premolars and molars (discussed fully in Chapter 20)

4. Gow-Gates mandibular nerve block

5. Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular nerve block

6. PDL injection for pulpal anesthesia of any mandibular tooth

7. IO injection for pulpal and soft tissue anesthesia of any mandibular tooth, but especially molars

8. Intraseptal injection for pulpal and soft tissue anesthesia of any mandibular tooth

Technique

1. A long dental needle is recommended for the adult patient. A 25-gauge long needle is preferred; a 27-gauge long is acceptable.

2. Area of insertion: Mucous membrane on the medial (lingual) side of the mandibular ramus, at the intersection of two lines—one horizontal, representing the height of needle insertion, the other vertical, representing the anteroposterior plane of injection

3. Target area: Inferior alveolar nerve as it passes downward toward the mandibular foramen but before it enters into the foramen

4. Landmarks (Figs. 14-2 and 14-3)

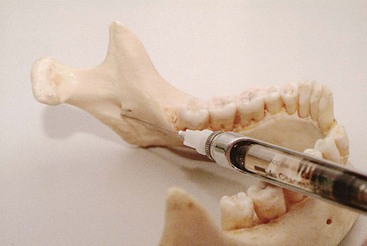

Figure 14-2 Osseous landmarks for inferior alveolar nerve block. 1, Lingula; 2, distal border of ramus; 3, coronoid notch; 4, coronoid process; 5, sigmoid (mandibular) notch; 6, neck of condyle; 7, head of condyle.

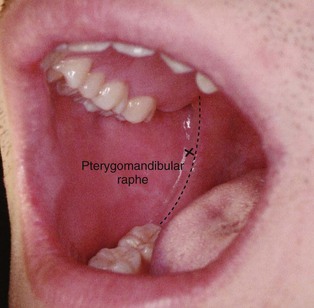

Figure 14-3 The posterior border of the mandibular ramus can be approximated intraorally by using the pterygomandibular raphe as it turns superiorly toward the maxilla.

a. Coronoid notch (greatest concavity on the anterior border of the ramus)

5. Orientation of the needle bevel: Less critical than with other nerve blocks, because the needle approaches the inferior alveolar nerve at roughly a right angle

a. Assume the correct position.

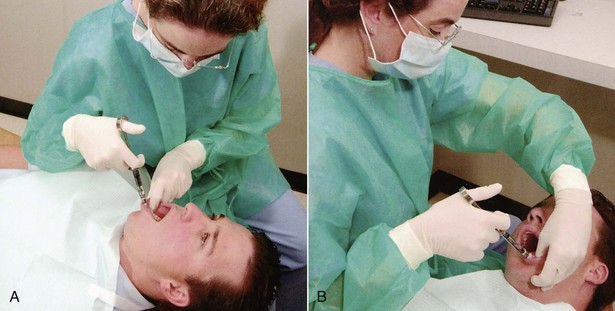

(1) For a right IANB, a right-handed administrator should sit at the 8 o’clock position facing the patient (Fig. 14-4, A).

Figure 14-4 Position of the administrator for a (A) right and (B) left inferior alveolar nerve block.

(2) For a left IANB, a right-handed administrator should sit at the 10 o’clock position facing in the same direction as the patient (Fig. 14-4, B).

b. Position the patient supine (recommended) or semisupine (if necessary). The mouth should be opened wide to allow greater visibility of, and access to, the injection site.

c. Locate the needle penetration (injection) site.

Three parameters must be considered during administration of IANB: (1) the height of the injection, (2) the anteroposterior placement of the needle (which helps to locate a precise needle entry point), and (3) the depth of penetration (which determines the location of the inferior alveolar nerve).

(1) Height of injection: Place the index finger or the thumb of your left hand in the coronoid notch.

(a) An imaginary line extends posteriorly from the fingertip in the coronoid notch to the deepest part of the pterygomandibular raphe (as it turns vertically upward toward the maxilla), determining the height of injection. This imaginary line should be parallel to the occlusal plane of the mandibular molar teeth. In most patients, this line lies 6 to 10 mm above the occlusal plane.

(b) The finger on the coronoid notch is used to pull the tissues laterally, stretching them over the injection site, making them taut, and enabling needle insertion to be less traumatic, while providing better visibility.

(c) The needle insertion point lies three fourths of the anteroposterior distance from the coronoid notch back to the deepest part of the pterygomandibular raphe (Fig. 14-5). Note: The line should begin at the midpoint of the notch and terminate at the deepest (most posterior) portion of the pterygomandibular raphe as the raphe bends vertically upward toward the palate.

Figure 14-5 Note the placement of the syringe barrel at the corner of the mouth, usually corresponding to the premolars. The needle tip gently touches the most distal end of the pterygomandibular raphe.

(d) The posterior border of the mandibular ramus can be approximated intraorally by using the pterygomandibular raphe as it bends vertically upward toward the maxilla* (see Fig. 14-3).

(e) An alternative method of approximating the length of the ramus is to place your thumb on the coronoid notch and your index finger extraorally on the posterior border of the ramus and estimate the distance between these points. However, many practitioners (including this author) have difficulty envisioning the width of the ramus in this manner.

(f) Prepare tissue at the injection site:

Place the barrel of the syringe in the corner of the mouth on the contralateral side (Figs. 14-5 and 14-6).

(2) Anteroposterior site of injection: Needle penetration occurs at the intersection of two points.

(a) Point 1 falls along the horizontal line from the coronoid notch to the deepest part of the pterygomandibular raphe as it ascends vertically toward the palate as just described.

(b) Point 2 is on a vertical line through point 1 about three fourths of the distance from the anterior border of the ramus. This determines the anteroposterior site of the injection.

(3) Penetration depth: In the third parameter of the IANB, bone should be contacted. Slowly advance the needle until you can feel it meet bony resistance.

(a) For most patients, it is not necessary to inject any local anesthetic solution as soft tissue is penetrated.

(b) For anxious or sensitive patients, it may be advisable to deposit small volumes as the needle is advanced. Buffered LA solution decreases the patient’s sensitivity during needle advancement.

(c) The average depth of penetration to bony contact will be 20 to 25 mm, approximately two thirds to three fourths the length of a long dental needle (Fig. 14-7).

Figure 14-7 Inferior alveolar nerve block. The depth of penetration is 20 to 25 mm (two thirds to three fourths the length of a long needle).

(d) The needle tip should now be located slightly superior to the mandibular foramen (where the inferior alveolar nerve enters [disappears] into bone). The foramen can neither be seen nor palpated clinically.

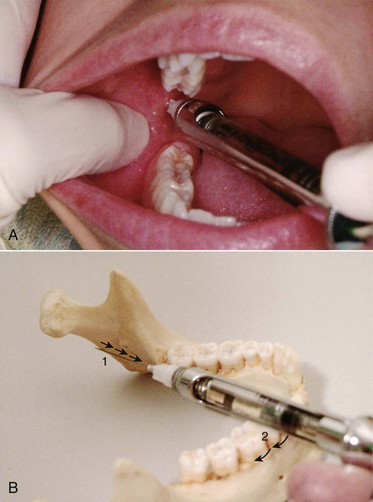

(e) If bone is contacted too soon (less than half the length of a long dental needle), the needle tip is usually located too far anteriorly (laterally) on the ramus (Fig. 14-8). To correct:

Figure 14-8 A, The needle is located too far anteriorly (laterally) on the ramus. B, To correct: Withdraw it slightly from the tissues (1) and bring the syringe barrel anteriorly toward the lateral incisor or canine (2); reinsert to proper depth.

(i) Withdraw the needle slightly but do not remove it from the tissue.

(ii) Bring the syringe barrel more toward the front of the mouth, over the canine or lateral incisor on the contralateral side.

(iii) Redirect the needle until a more appropriate depth of insertion is obtained. The needle tip is now located more posteriorly in the mandibular sulcus.

(f) If bone is not contacted, the needle tip usually is located too far posterior (medial) (Fig. 14-9). To correct:

d. Insert the needle. When bone is contacted, withdraw approximately 1 mm to prevent subperiosteal injection.

e. Aspirate in two planes. If negative, slowly deposit 1.5 mL of anesthetic over a minimum of 60 seconds. (Because of the high incidence of positive aspiration and the natural tendency to deposit solution too rapidly, the sequence of slow injection, reaspiration, slow injection, reaspiration is strongly recommended.)

f. Slowly withdraw the syringe, and when approximately half its length remains within tissues, reaspirate. If negative, deposit a portion of the remaining solution (0.2 mL) to anesthetize the lingual nerve.

(1) In most patients, this deliberate injection for lingual nerve anesthesia is not necessary, because local anesthetic from the IANB anesthetizes the lingual nerve.

g. Withdraw the syringe slowly and make the needle safe.

h. After approximately 20 seconds, return the patient to the upright or semiupright position.

i. Wait 3 to 5 minutes before testing for pulpal anesthesia.

Signs and Symptoms

1. Subjective: Tingling or numbness of the lower lip indicates anesthesia of the mental nerve, a terminal branch of the inferior alveolar nerve. This is a good indication that the inferior alveolar nerve is anesthetized, although it is not a reliable indicator of the depth of anesthesia.

2. Subjective: Tingling or numbness of the tongue indicates anesthesia of the lingual nerve, a branch of the posterior division of V3. It usually accompanies IANB but may be present without anesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve.

3. Objective: Using an electrical pulp tester (EPT) and eliciting no response to maximal output (80/80) on two consecutive tests at least 2 minutes apart serves as a “guarantee” of successful pulpal anesthesia in nonpulpitic teeth.24,27,28

Precautions

Failures of Anesthesia

The most common causes of absent or incomplete IANB follow:

1. Deposition of anesthetic too low (below the mandibular foramen). To correct: Reinject at a higher site (approximately 5 to 10 mm above the previous site).

2. Deposition of the anesthetic too far anteriorly (laterally) on the ramus. This is diagnosed by lack of anesthesia except at the injection site and by the minimum depth of needle penetration before contact with bone (e.g., the [long] needle is usually less than halfway into tissue). To correct: Redirect the needle tip posteriorly.

3. Accessory innervation to the mandibular teeth

a. The primary symptom is isolated areas of incomplete pulpal anesthesia encountered in the mandibular molars (most commonly the mesial portion of the mandibular first molar).

b. Although it has been postulated that several nerves provide the mandibular teeth with accessory sensory innervation (e.g., the cervical accessory and mylohyoid nerves), current thinking supports the mylohyoid nerve as the prime candidate.29-31 The Gow-Gates mandibular nerve block, which routinely blocks the mylohyoid nerve, is not associated with problems of accessory innervation (unlike the IANB, which normally does not block the mylohyoid nerve).

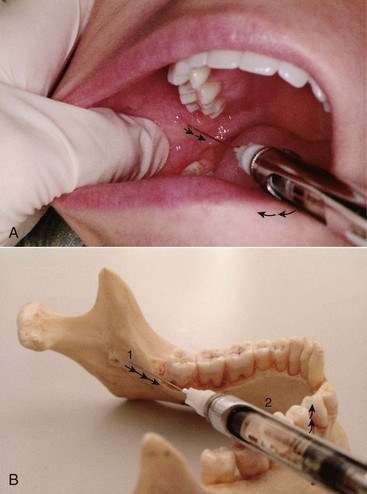

(a) Use a 25-gauge (or 27-gauge) long needle.

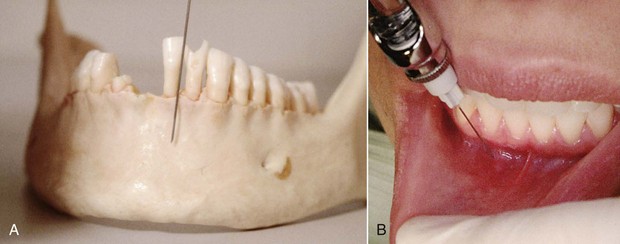

(b) Retract the tongue toward the midline with a mirror handle or tongue depressor to provide access and visibility to the lingual border of the body of the mandible (Fig. 14-10).

Figure 14-10 A, Retract the tongue to gain access to, and increase the visibility of, the lingual border of the mandible. B, Direct the needle tip below the apical region of the tooth immediately posterior to the tooth in question.

(c) Place the syringe in the corner of mouth on the opposite side and direct the needle tip to the apical region of the tooth immediately posterior to the tooth in question (e.g., the apex of the second molar if the first molar is the problem).

(d) Penetrate the soft tissues and advance the needle until bone (e.g., the lingual border of the body of the mandible) is contacted. Topical anesthesia is unnecessary if lingual anesthesia is already present. The depth of penetration to bone is 3 to 5 mm.

(e) Aspirate in two planes. If negative, slowly deposit approximately 0.6 mL (one third cartridge) of anesthetic (in about 20 seconds).

(2) Technique #2. In any situation in which partial anesthesia of a tooth occurs, the PDL or IO injection may be administered; both techniques have a high expectation of success. (See Chapter 15 for discussion of PDL and IO techniques.)

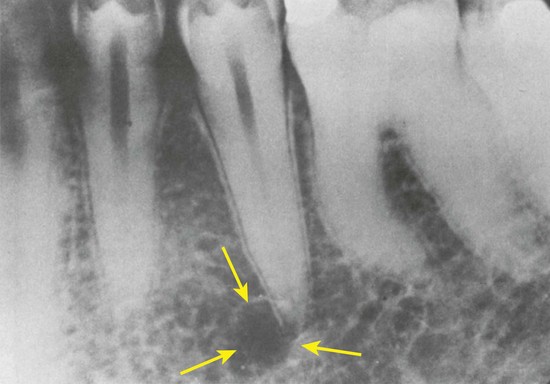

d. Whenever a bifid inferior alveolar nerve is detected on the radiograph, incomplete anesthesia of the mandible may develop after IANB. In many such cases, a second mandibular foramen, located more inferiorly, exists. To correct: Deposit a volume of solution inferior to the normal anatomic landmark.

4. Incomplete anesthesia of the central or lateral incisors

a. This may comprise isolated areas of incomplete pulpal anesthesia.

b. Often this is due to overlapping fibers of the contralateral inferior alveolar nerve, although it may also arise (rarely) from innervation from the mylohyoid nerve.

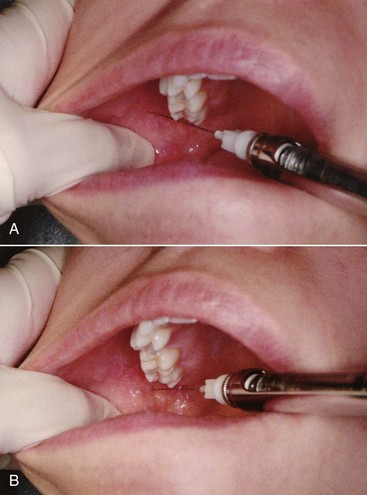

(a) Infiltrate 0.9 mL supraperiosteally into the mucobuccal fold below the apex of the tooth in question, followed immediately by injection of 0.9 mL onto the lingual aspect of the same tooth (Fig. 14-11). This generally is highly effective in the central and lateral incisor teeth because of the many small nutrient canals in the cortical bone near the region of the incisive fossa. The local anesthetic articaine HCl appears to have the greatest success.22,32

Figure 14-11 With supraperiosteal injection, the needle tip is directed toward the apical region of the tooth in question. A, On a skull. B, In the mouth.

(b) A 27-gauge short needle is recommended.

(c) Direct the needle tip toward the apical region of the tooth in question. Topical anesthesia is not necessary if mental nerve anesthesia is present.

(e) If negative, slowly deposit 0.9 mL of local anesthetic solution in approximately 30 seconds.

(f) Administer 0.9 mL on the lingual aspect of the same tooth

(g) Wait about 5 minutes before starting the dental procedure.

(2) As an alternative, the PDL injection may be used. The PDL has great success in the mandibular anterior region.

Complications

a. Swelling of tissues on the medial side of the mandibular ramus after the deposition of anesthetic

b. Management: Pressure and cold (e.g., ice) to the area for a minimum of 3 to 5 minutes

a. Muscle soreness or limited movement

(1) A slight degree of soreness when opening the mandible is extremely common after IANB (after anesthesia has dissipated).

(2) More severe soreness associated with limited mandibular opening is rare.

b. Causes and management of limited mandibular opening after injection are discussed in Chapter 17.

3. Transient facial paralysis (facial nerve anesthesia)

a. Produced by the deposition of local anesthetic into the body of the parotid gland, blocking the VII cranial nerve (facial n.), a motor nerve to the muscles of facial expression. Signs and symptoms include an inability to close the lower eyelid and drooping of the upper lip on the affected side.

b. Management of transient facial nerve paralysis is discussed in Chapter 17.

Buccal Nerve Block

The buccal nerve is a branch of the anterior division of V3 and consequently is not anesthetized during IANB. Nor is anesthesia of the buccal nerve necessary for most restorative dental procedures. The buccal nerve provides sensory innervation to the buccal soft tissues adjacent to the mandibular molars only. The sole indication for administration of a buccal nerve block therefore is when manipulation of these tissues is contemplated (e.g., with scaling or curettage, the placement of a rubber dam clamp on soft tissues, the removal of subgingival caries, subgingival tooth preparation, placement of gingival retraction cord, or the placement of matrix bands).

It is common for the buccal nerve block to be routinely administered after IANB, even when buccal soft tissue anesthesia in the molar region is not required. There is absolutely no indication for this injection in such a situation.

The buccal nerve block, commonly referred to as the long buccal nerve block, has a success rate approaching 100%. The reason for this is that the buccal nerve is readily accessible to the local anesthetic as it lies immediately beneath the mucous membrane, not buried within bone.

Indication

When buccal soft tissue anesthesia is necessary for dental procedures in the mandibular molar region.

Technique

1. A 25- or 27-gauge long needle is recommended. This is most often used because the buccal nerve block is usually administered immediately after an IANB. A long needle is recommended because of the posterior deposition site, not the depth of tissue insertion (which is minimal).

2. Area of insertion: Mucous membrane distal and buccal to the most distal molar tooth in the arch

3. Target area: Buccal nerve as it passes over the anterior border of the ramus

4. Landmarks: Mandibular molars, mucobuccal fold

5. Orientation of the bevel: Toward bone during the injection

a. Assume the correct position.

(1) For a right buccal nerve block, a right-handed operator should sit at the 8 o’clock position directly facing the patient (Fig. 14-13, A).

(2) For a left buccal nerve block, a right-handed operator should sit at 10 o’clock facing in the same direction as the patient (Fig. 14-13, B).

b. Position the patient supine (recommended) or semisupine.

c. Prepare the tissues for penetration distal and buccal to the most posterior molar. *

d. With your left index finger (if right-handed), pull the buccal soft tissues in the area of injection laterally so that visibility will be improved. Taut tissues permit an atraumatic needle penetration.

e. Direct the syringe toward the injection site with the bevel facing down toward bone and the syringe aligned parallel to the occlusal plane on the side of injection but buccal to the teeth (Fig. 14-14, A).

Figure 14-14 Syringe alignment. A, Parallel to the occlusal plane on the side of injection but buccal to it. B, Distal and buccal to the last molar.

f. Penetrate mucous membrane at the injection site, distal and buccal to the last molar (Fig. 14-14, B).

g. Advance the needle slowly until mucoperiosteum is gently contacted.

(1) To prevent pain when the needle contacts mucoperiosteum, deposit a few drops of local anesthetic just before contact.

(2) The depth of penetration is seldom more than 2 to 4 mm, and usually only 1 or 2 mm.

i. If negative, slowly deposit 0.3 mL (approximately one eighth of a cartridge) over 10 seconds.

(1) If tissue at the injection site balloons (becomes swollen during injection), stop depositing solution.

(2) If solution runs out the injection site (back into the patient’s mouth) during deposition:

(b) Advance the needle tip deeper into the tissue.*

j. Withdraw the syringe slowly and immediately make the needle safe.

k. Wait approximately 3 to 5 minutes before commencing the planned dental procedure.

Precautions

1. Pain on insertion from contacting unanesthetized periosteum. This can be prevented by depositing a few drops of local anesthetic before touching the periosteum.

2. Local anesthetic solution not being retained at the injection site. This generally means that needle penetration is not deep enough, the bevel of the needle is only partially in the tissues, and solution is escaping during the injection.

Mandibular Nerve Block: The Gow-Gates Technique

Successful anesthesia of the mandibular teeth and soft tissues is more difficult to achieve than anesthesia of maxillary structures. Primary factors for this failure rate are the greater anatomic variation in the mandible and the need for deeper soft tissue penetration. In 1973, George Albert Edwards Gow-Gates (1910-2001),33 a general practitioner of dentistry in Australia, described a new approach to mandibular anesthesia. He had used this technique in his practice for approximately 30 years, with an astonishingly high success rate (approximately 99% in his experienced hands).

The Gow-Gates technique is a true mandibular nerve block because it provides sensory anesthesia to virtually the entire distribution of V3. The inferior alveolar, lingual, mylohyoid, mental, incisive, auriculotemporal, and buccal nerves all are blocked in the Gow-Gates injection.

Significant advantages of the Gow-Gates technique over IANB include its higher success rate, its lower incidence of positive aspiration (approximately 2% vs. 10% to 15% with the IANB),33,34 and the absence of problems with accessory sensory innervation to the mandibular teeth.

The only apparent disadvantage is a relatively minor one: An administrator experienced with the IANB may feel uncomfortable while learning the Gow-Gates mandibular nerve block (GGMNB). Indeed, the incidence of unsuccessful anesthesia with GGMNB may be as high as (if not higher than) that for the IANB until the administrator gains clinical experience with it. Following this “learning curve,” success rates greater than 95% are common. A new student of local anesthesia usually does not encounter as much difficulty with the GGMNB as the more experienced administrator. This is a result of the strong bias of the experienced administrator to deposit the anesthetic drug “lower” (e.g., in the “usual” place). Two approaches are suggested for becoming accustomed to the GGMNB. The first is to begin to use the technique on all patients requiring mandibular anesthesia. Allow at least 1 to 2 weeks to gain clinical experience. The second approach is to continue using the conventional IANB, but to use the GGMNB technique whenever clinically inadequate anesthesia occurs. Reanesthetize the patient using the GGMNB. Although experience is accumulated more slowly with this latter approach, its effectiveness is more dramatic because patients who were previously difficult to anesthetize now may be more easily managed.

Areas Anesthetized

1. Mandibular teeth to the midline

2. Buccal mucoperiosteum and mucous membranes on the side of injection

3. Anterior two thirds of the tongue and floor of the oral cavity

4. Lingual soft tissues and periosteum

5. Body of the mandible, inferior portion of the ramus

6. Skin over the zygoma, posterior portion of the cheek, and temporal regions

Advantages

1. Requires only one injection; a buccal nerve block is usually unnecessary (accessory innervation has been blocked)

2. High success rate (>95%), with experience

4. Few postinjection complications (e.g., trismus)

5. Provides successful anesthesia where a bifid inferior alveolar nerve and bifid mandibular canals are present

Disadvantages

1. Lingual and lower lip anesthesia is uncomfortable for many patients and is possibly dangerous for certain individuals.

2. The time to onset of anesthesia is somewhat longer (5 minutes) than with an IANB (3 to 5 minutes), primarily because of the size of the nerve trunk being anesthetized and the distance of the nerve trunk from the deposition site (approximately 5 to 10 mm).

3. There is a learning curve with the Gow-Gates technique. Clinical experience is necessary to truly learn the technique and to fully take advantage of its greater success rate. This learning curve may prove frustrating for some persons.

Alternatives

1. IANB and buccal nerve block

2. Vazirani-Akinosi closed-mouth mandibular block

3. Incisive nerve block: Pulpal and buccal soft tissue anterior to the mental foramen

4. Mental nerve block: Buccal soft tissue anterior to the first molar

5. Buccal nerve block: Buccal soft tissue from the third to the mental foramen region

6. Supraperiosteal injection: For pulpal anesthesia of the central and lateral incisors, and in some instances the canine

7. Intraosseous technique (see Chapter 15 for discussion)

8. PDL injection technique (see Chapter 15 for discussion)

Technique

1. 25- or 27-gauge long needle recommended

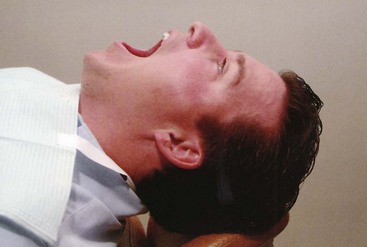

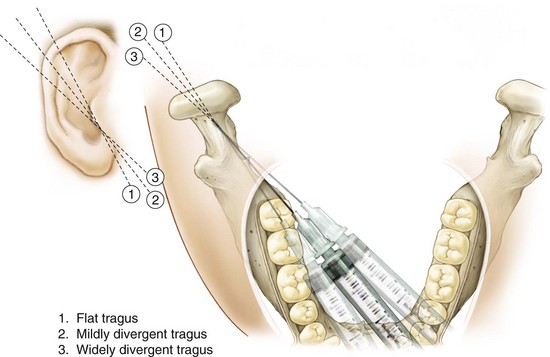

2. Area of insertion: Mucous membrane on the mesial of the mandibular ramus, on a line from the intertragic notch to the corner of the mouth, just distal to the maxillary second molar

3. Target area: Lateral side of the condylar neck, just below the insertion of the lateral pterygoid muscle (Fig. 14-16)

(1) Lower border of the tragus (intertragic notch). The correct landmark is the center of the external auditory meatus, which is concealed by the tragus; therefore its lower border is adopted as a visual aid (Fig. 14-17).

(1) Height of injection established by placement of the needle tip just below the mesiolingual (mesiopalatal) cusp of the maxillary second molar (Fig. 14-18, A)

Figure 14-18 Intraoral landmarks for a Gow-Gates mandibular block. The tip of the needle is placed just below the mesiolingual cusp of the maxillary second molar (A) and is moved to a point just distal to the molar (B), maintaining the height established in the preceding step. This is the insertion point for the Gow-Gates mandibular nerve block.

(2) Penetration of soft tissues just distal to the maxillary second molar at the height established in the preceding step (Fig. 14-18, B)

5. Orientation of the bevel: Not critical

a. Assume the correct position.

(1) For a right GGMNB, a right-handed administrator should sit in the 8 o’clock position facing the patient.

(2) For a left GGMNB, a right-handed administrator should sit in the 10 o’clock position facing the same direction as the patient.

(3) These are the same positions used for a right and a left IANB (see Fig. 14-4).

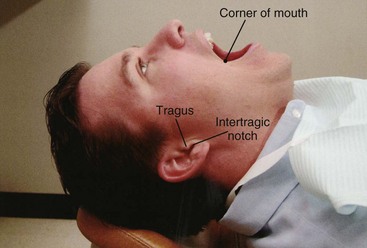

b. Position the patient (Fig. 14-19).

(1) Supine is recommended, although semisupine also may be used.

(2) Ask the patient to extend his or her neck and to open wide for the duration of the technique. The condyle then assumes a more frontal position and is closer to the mandibular nerve trunk.

c. Locate the extraoral landmarks:

d. Place your left index finger or thumb on the coronoid notch; determination of the coronoid notch is not essential to the success of Gow-Gates, but in the author’s experience, palpation of this familiar intraoral landmark provides a sense of security, enables the soft tissues to be retracted, and aids in determination of the site of needle penetration.

e. Visualize the intraoral landmarks.

(1) Mesiolingual (mesiopalatal) cusp of the maxillary second molar

(2) Needle penetration site is just distal to the maxillary second molar at the height of the tip of its mesiolingual cusp.

f. Prepare tissues at the site of penetration.

g. Direct the syringe (held in your right hand) toward the site of injection from the corner of the mouth on the opposite side (as in IANB).

h. Insert the needle gently into tissues at the injection site just distal to the maxillary second molar at the height of its mesiolingual (mesiopalatal) cusp.

i. Align the needle with the plane extending from the corner of the mouth on the opposite side to the intertragic notch on the side of injection. It should be parallel with the angle between the ear and the face (Fig. 14-20).

Figure 14-20 The barrel of the syringe and the needle are held parallel to a line connecting the corner of the mouth and the intertragic notch.

j. Direct the syringe toward the target area on the tragus.

(1) The syringe barrel lies in the corner of the mouth over the premolars, but its position may vary from molars to incisors, depending on the divergence of the ramus as assessed by the angle of the ear to the side of the face (Fig. 14-21).

(2) The height of insertion above the mandibular occlusal plane is considerably greater (10 to 25 mm, depending on the patient’s size) than that of the IANB.

(3) When a maxillary third molar is present in a normal occlusion, the site of needle penetration is just distal to that tooth.

k. Slowly advance the needle until bone is contacted.

(1) Bone contacted is the neck of the condyle.

(2) The average depth of soft tissue penetration to bone is 25 mm, although some variation is observed. For a given patient, the depth of soft tissue penetration with the GGMNB approximates that with the IANB.

(3) If bone is not contacted, withdraw the needle slightly and redirect. (Experience with the Gow-Gates technique has demonstrated that medial deflection of the needle is the most common cause of failure to contact bone.) Move the barrel of the syringe somewhat more distally, thereby angulating the needle tip anteriorly, and readvance the needle until bony contact is made.

(a) A second cause of failure to contact bone is partial closure of the patient’s mouth (see step 6, b[2]). Once the patient closes even slightly, two negatives occur: (1) The thickness of soft tissue increases, and (2) the condyle moves in a distal direction. Both of these make it more difficult to locate the condylar neck with the needle.

(4) If bone is not contacted, do not deposit any local anesthetic.

n. If positive, withdraw the needle slightly, angle it superiorly, reinsert, reaspirate, and, if now negative, deposit the solution. Positive aspiration usually occurs in the internal maxillary artery, which is located inferior to the target area. The positive aspiration rate with the GGMNB technique is approximately 2%.33,34

o. If negative, slowly deposit 1.8 mL of solution over 60 to 90 seconds. Gow-Gates originally recommended that 3 mL of anesthetic be deposited.33 However, experience with the GGMNB shows that 1.8 mL is usually adequate to provide clinically acceptable anesthesia in virtually all cases. When partial anesthesia develops after administration of 1.8 mL, a second injection of approximately 1.2 mL is recommended.

p. Withdraw the syringe and make the needle safe.

q. Request that the patient keep his or her mouth open for 1 to 2 minutes after the injection to permit diffusion of the anesthetic solution.

r. After completion of the injection, return the patient to the upright or semiupright position.

s. Wait at least 3 to 5 minutes before commencing the dental procedure. Onset of anesthesia with the GGMNB may be somewhat slower, requiring 5 minutes or longer for the following reasons:

Signs and Symptoms

1. Subjective: Tingling or numbness of the lower lip indicates anesthesia of the mental nerve, a terminal branch of the inferior alveolar nerve. It is also a good indication that the inferior alveolar nerve may be anesthetized.

2. Subjective: Tingling or numbness of the tongue indicates anesthesia of the lingual nerve, a branch of the posterior division of the mandibular nerve. It is always present in a successful Gow-Gates mandibular block.

3. Objective: Using an electrical pulp tester (EPT) and eliciting no response to maximal output (80/80) on two consecutive tests at least 2 minutes apart serves as a “guarantee” of successful pulpal anesthesia in nonpulpitic teeth.24,27,28

Precautions

Do not deposit local anesthetic if bone is not contacted; the needle tip usually is distal and medial to the desired site:

Failures of Anesthesia

Rare with the Gow-Gates mandibular block once the administrator becomes familiar with the technique:

1. Too little volume. The greater diameter of the mandibular nerve may require a larger volume of anesthetic solution. Deposit up to 1.2 mL in a second injection if the depth of anesthesia is inadequate after the initial 1.8 mL.

2. Anatomic difficulties. Do not deposit anesthetic unless bone is contacted.

Complications

1. Hematoma (<2% incidence of positive aspiration)

3. Temporary paralysis of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. In a case of cranial nerve paralysis after a right Gow-Gates mandibular block, diplopia, right-sided blepharoptosis, and complete paralysis of the right eye persisted for 20 minutes after the injection. This has occurred after the accidental rapid intravenous administration of local anesthetic.35 The recommendations of Dr. Gow-Gates include placing the needle on the lateral side of the anterior surface of the condyle, aspirating carefully, and depositing slowly.33,34 If bone is not contacted, anesthetic solution should not be administered.

Vazirani-Akinosi Closed-Mouth Mandibular Block

The introduction of the Gow-Gates mandibular nerve block in 1973 spurred interest in alternative methods of achieving anesthesia in the lower jaw. In 1977, Dr. Joseph Akinosi reported on a closed-mouth approach to mandibular anesthesia.36 Although this technique can be used whenever mandibular anesthesia is desired, its primary indication remains those situations where limited mandibular opening precludes the use of other mandibular injection techniques. Such situations include the presence of spasm of the muscles of mastication (trismus) on one side of the mandible after numerous attempts at IANB, as might occur with a “hot” mandibular molar. In this instance, multiple injections have been necessary to provide anesthesia adequate to extirpate the pulpal tissues of the involved mandibular molar. When the anesthetic effect resolves hours later, the muscles into which the anesthetic solution was deposited become tender, producing some discomfort on opening the jaw. During a period of sleep, when the muscles are not in use, the muscles go into spasm (the same way one’s leg muscles might go into spasm after strenuous exercise, making it difficult to stand or walk the next morning), leaving the patient with significantly reduced occlusal opening in the morning.

The management of trismus is reviewed in Chapter 17.

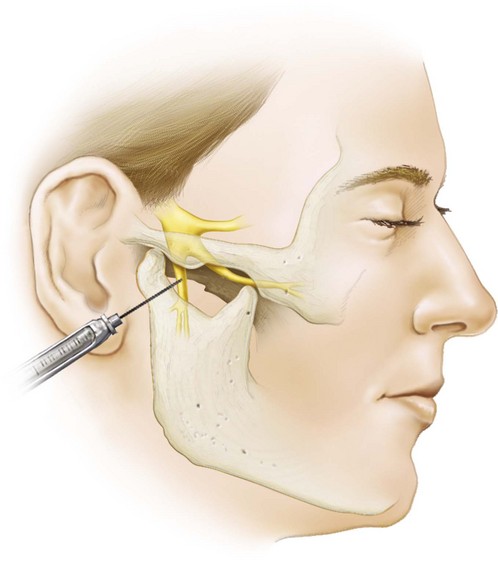

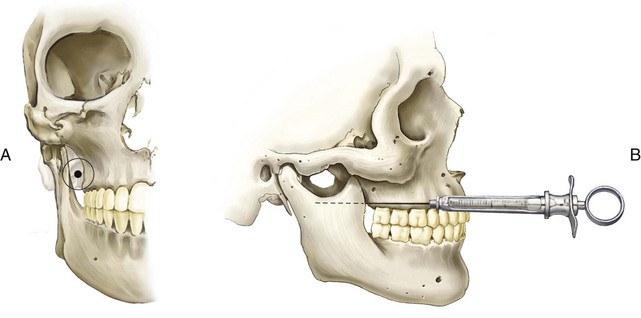

If it is necessary to continue dental care in the patient with significant trismus, the options for providing mandibular anesthesia are extremely limited. Inferior alveolar and Gow-Gates mandibular nerve blocks cannot be attempted when significant trismus is present. Extraoral mandibular nerve blocks can be attempted and, indeed, possess a significantly high success rate in experienced hands. Extraoral mandibular blocks can be administered through the sigmoid notch or inferiorly from the chin (Fig. 14-22).37,38 Because the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve provides motor innervation to the muscles of mastication, a third division (V3) block will relieve trismus that is produced secondary to muscle spasm (trismus may also result from other causes). Although dentists are permitted to administer extraoral nerve blocks, few in clinical practice actually do so. The Vazirani-Akinosi technique is an intraoral approach to providing both anesthesia and motor blockade in cases of severe unilateral trismus.

Figure 14-22 Extraoral mandibular block using lateral approach through the sigmoid notch. (Redrawn from Bennett CR: Monheim’s local anesthesia and pain control in dental practice, ed 6, St Louis, 1978, Mosby.)

In early editions of this textbook, the technique described in the following section was termed the Akinosi closed-mouth mandibular block. However, a very similar technique was described in 1960 by Vazirani.39 The name Vazirani-Akinosi closed-mouth mandibular block was adopted for the fourth edition, giving recognition to both of the doctors who devised and publicized this closed-mouth approach to mandibular anesthesia.

In 1992, Wolfe described a modification of the original Vazirani-Akinosi technique.40 The technique described was identical to the original technique, except that the author recommended bending the needle at a 45-degree angle to enable it to remain in close proximity to the medial (lingual) side of the mandibular ramus as the needle is advanced through the tissues. Because the potential for needle breakage is increased when it is bent, bending any needle that is to be inserted into tissues to any significant depth cannot be recommended. The Vazirani-Akinosi closed-mouth mandibular block can be administered successfully without bending the needle.

Areas Anesthetized

Advantages

Alternatives

No intraoral nerve blocks are available. If a patient is unable to open his or her mouth because of trauma, infection, or postinjection trismus, no other suitable intraoral techniques are available. The extraoral mandibular nerve block may be used when the doctor is well versed in the procedure.

Technique

1. A 25-gauge long needle is recommended (although a 27-gauge long may be preferred in patients whose ramus flares laterally more than usual).

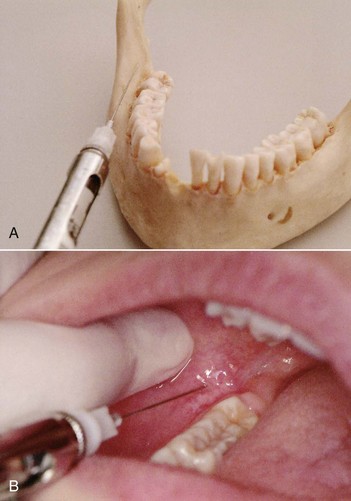

2. Area of insertion: Soft tissue overlying the medial (lingual) border of the mandibular ramus directly adjacent to the maxillary tuberosity at the height of the mucogingival junction adjacent to the maxillary third molar (Fig. 14-24)

Figure 14-24 A, Area of needle insertion for a Vazirani-Akinosi block. B, Hold the syringe and needle at the height of the mucogingival junction above the maxillary third molar. (Redrawn from Gustainis JF, Peterson LJ: An alternative method of mandibular nerve block, J Am Dent Assoc 103:33–36, 1981.)

3. Target area: Soft tissue on the medial (lingual) border of the ramus in the region of the inferior alveolar, lingual, and mylohyoid nerves as they run inferiorly from the foramen ovale toward the mandibular foramen (the height of injection with the Vazirani-Akinosi being below that of the GGMNB but above that of the IANB)

5. Orientation of the bevel (bevel orientation in the closed-mouth mandibular block is very important): The bevel must be oriented away from the bone of the mandibular ramus (e.g., bevel faces toward the midline).

a. Assume the correct position. For a right or a left Vazirani-Akinosi, a right-handed administrator should sit in the 8 o’clock position facing the patient.

b. Position the patient supine (recommended) or semisupine.

c. Place your left index finger or thumb on the coronoid notch, reflecting the tissues on the medial aspect of the ramus laterally. Reflecting the soft tissues aids in visualization of the injection site and decreases trauma during needle insertion.

e. Prepare the tissues at the site of penetration:

f. Ask the patient to occlude gently with the cheeks and muscles of mastication relaxed.

g. Reflect the soft tissues on the medial border of the ramus laterally.

h. The barrel of the syringe is held parallel to the maxillary occlusal plane, with the needle at the level of the mucogingival junction of the maxillary third (or second) molar (Fig. 14-24).

i. Direct the needle posteriorly and slightly laterally, so it advances at a tangent to the posterior maxillary alveolar process and parallel to the maxillary occlusal plane.

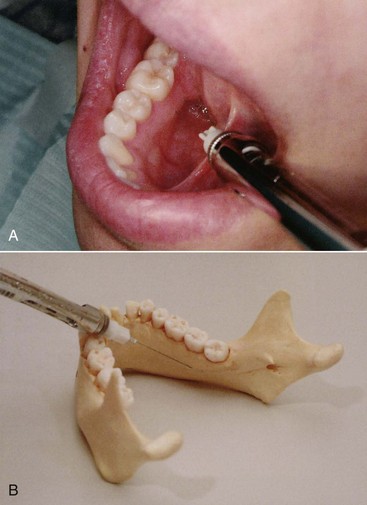

j. Orient the bevel away from the mandibular ramus; thus as the needle advances through tissues, needle deflection occurs toward the ramus and the needle remains in close proximity to the inferior alveolar nerve (Fig. 14-25).

Figure 14-25 Vazirani-Akinosi closed-mouth mandibular nerve block. Barrel of syringe is held parallel to maxillary occlusal plane with the needle at the level of the mucogingival junction of the second or third maxillary molar.

k. Advance the needle 25 mm into tissue (for an average-sized adult). This distance is measured from the maxillary tuberosity. The tip of the needle should lie in the midportion of the pterygomandibular space, close to the branches of V3 (Fig. 14-26).

Figure 14-26 Advance the needle posteriorly into tissues on the medial side of the mandibular ramus.

m. If negative, deposit 1.5 to 1.8 mL of anesthetic solution in approximately 60 seconds.

n. Withdraw the syringe slowly and immediately make the needle safe.

o. After the injection, return the patient to an upright or semiupright position.

p. Motor nerve paralysis develops as quickly as or more quickly than sensory anesthesia. The patient with trismus begins to notice increased ability to open the jaws shortly after the deposition of anesthetic.

q. Anesthesia of the lip and tongue is noted to start in about in 1 to  minutes; the dental procedure usually can start within 5 minutes.

minutes; the dental procedure usually can start within 5 minutes.

r. When motor paralysis is present but sensory anesthesia is inadequate to permit the dental procedure to begin, readminister the Vazirani-Akinosi block, or, because the patient can now open his or her jaws, perform a standard inferior alveolar, Gow-Gates, or incisive nerve block, or a PDL or intraosseous injection.

Signs and Symptoms

1. Subjective: Tingling or numbness of the lower lip indicates anesthesia of the mental nerve, a terminal branch of the inferior alveolar nerve, which is a good sign that the inferior alveolar nerve has been anesthetized.

2. Subjective: Tingling or numbness of the tongue indicates anesthesia of the lingual nerve, a branch of the posterior division of the mandibular nerve.

3. Objective: Using an electrical pulp tester (EPT) and eliciting no response to maximal output (80/80) on two consecutive tests at least 2 minutes apart serves as a “guarantee” of successful pulpal anesthesia in nonpulpitic teeth.24,27,28

Precaution

Do not overinsert the needle (>25 mm). Decrease the depth of penetration in smaller patients; the depth of insertion will vary with the anteroposterior size of the patient’s ramus.

Failures of Anesthesia

1. Almost always because of failure to appreciate the flaring nature of the ramus. If the needle is directed medially, it rests medial to the sphenomandibular ligament in the pterygomandibular space, and the injection fails. This occurs more commonly when a right-handed administrator uses the left-side Vazirani-Akinosi injection (or a left-handed administrator uses the right-side Vazirani-Akinosi injection). It may be prevented by directing the needle tip parallel to the lateral flare of the ramus and by using a 27-gauge needle in place of a 25-gauge.

2. Needle insertion point too low. To correct: Insert the needle at or slightly above the level of the mucogingival junction of the last maxillary molar. The needle also must remain parallel to the occlusal plane as it advances through the soft tissues.

3. Underinsertion or overinsertion of the needle. Because no bone is contacted in the Vazirani-Akinosi technique, the depth of soft tissue penetration is somewhat arbitrary. Akinosi recommended a penetration depth of 25 mm in the average-sized adult, measuring from the maxillary tuberosity. In smaller or larger patients, this depth of penetration should be altered.

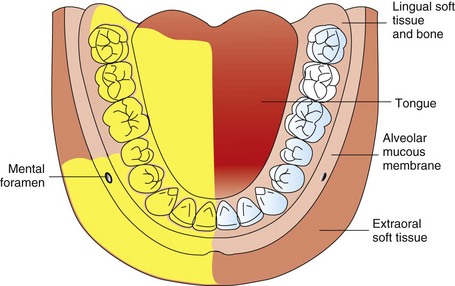

Mental Nerve Block

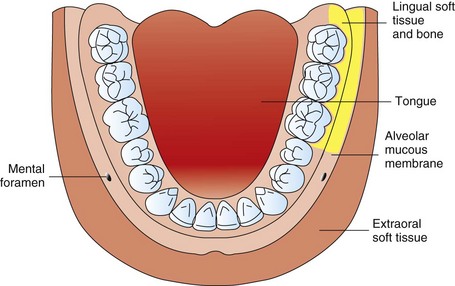

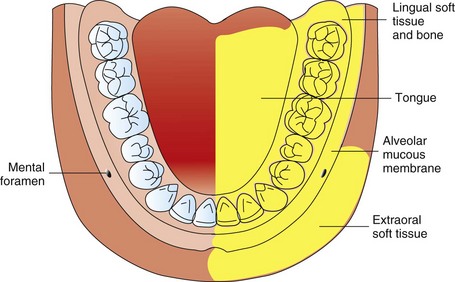

The mental nerve is a terminal branch of the inferior alveolar nerve. Exiting the mental foramen at or near the apices of the mandibular premolars, it provides sensory innervation to the buccal soft tissues lying anterior to the foramen and the soft tissues of the lower lip and chin on the side of injection.

For most dental procedures, there is very little indication for use of the mental nerve block. Indeed, of the techniques described in this section, the mental nerve block is the least frequently employed. It is used primarily for buccal soft tissue procedures, such as suturing of lacerations or biopsies. Its success rate approaches 100% because of the ease of accessibility to the nerve.

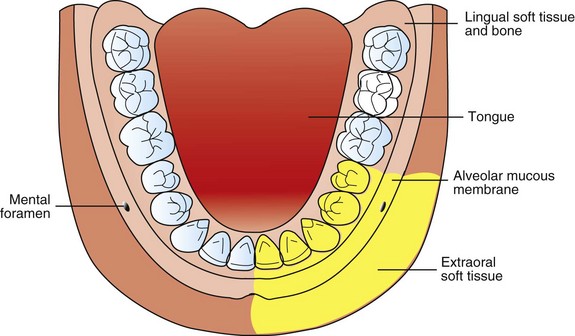

Areas Anesthetized

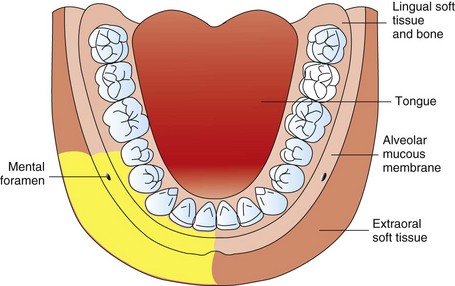

Buccal mucous membranes anterior to the mental foramen (around the second premolar) to the midline and skin of the lower lip (Fig. 14-27) and chin.

Indication

When buccal soft tissue anesthesia is necessary for procedures in the mandible anterior to the mental foramen, such as the following:

Technique

1. A 25- or 27-gauge short needle is recommended.

2. Area of insertion: Mucobuccal fold at or just anterior to the mental foramen

3. Target area: Mental nerve as it exits the mental foramen (usually located between the apices of the first and second premolars)

4. Landmarks: Mandibular premolars and mucobuccal fold

5. Orientation of the bevel: Toward bone during the injection

a. Assume the correct position.

(1) For a right or left mental nerve block. a right-handed administrator should sit comfortably in front of the patient so that the syringe may be placed into the mouth below the patient’s line of sight (Fig. 14-28).

(1) Supine is recommended, but semisupine is acceptable.

(2) Have the patient partially close. This permits greater access to the injection site.

(1) Place your index finger in the mucobuccal fold and press against the body of the mandible in the first molar area.

(2) Move your finger slowly anteriorly until the bone beneath your finger feels irregular and somewhat concave (Fig. 14-29).

Figure 14-29 Locate the mental foramen by moving the fleshy pad of your finger anteriorly until the bone beneath becomes irregular and somewhat concave.

(a) The bone posterior and anterior to the mental foramen is smooth; however, the bone immediately around the foramen is rougher to the touch.

(b) The mental foramen usually is found around the apex of the second premolar. However, it may be found anterior or posterior to this site.

(c) The patient may comment that finger pressure in this area produces soreness as the mental nerve is compressed against bone.

(3) If radiographs are available, the mental foramen may be located easily (Fig. 14-30).

d. Prepare tissue at the site of penetration.

e. With your left index finger, pull the lower lip and buccal soft tissues laterally.

f. Orient the syringe with the bevel directed toward bone.

g. Penetrate the mucous membrane at the injection site, at the canine or first premolar, directing the syringe toward the mental foramen (Fig. 14-31).

h. Advance the needle slowly until the foramen is reached. The depth of penetration is 5 to 6 mm. For the mental nerve block to be successful, there is no need to enter the mental foramen or to contact bone.

j. If negative, slowly deposit 0.6 mL (approximately one third cartridge) over 20 seconds. If tissue at the injection site balloons (swells as the anesthetic is injected), stop the deposition and remove the syringe.

k. Withdraw the syringe and immediately make the needle safe.

Precautions

Striking the periosteum produces discomfort. To prevent: Avoid contact with the periosteum or deposit a small amount of solution before contacting the periosteum.

Complications

2. Hematoma (bluish discoloration and tissue swelling at the injection site). Blood may exit the needle puncture point into the buccal fold. To treat: Apply pressure with gauze directly to the area of bleeding for at least 2 minutes (see Fig. 17-2).

3. Paresthesia of lip and/or chin. Contact of the needle with the mental nerve as it exits the mental foramen may lead to the sensation of an “electric shock” or to varying degrees of paresthesia (rare)

Incisive Nerve Block

The incisive nerve is a terminal branch of the inferior alveolar nerve. Originating as a direct continuation of the inferior alveolar nerve at the mental foramen, the incisive nerve travels anteriorly in the incisive canal, providing sensory innervation to those teeth located anterior to the mental foramen. The nerve is always anesthetized when an inferior alveolar or mandibular nerve block is successful; therefore the incisive nerve block is not necessary when these blocks are administered.

The premolars, canine, and lateral and central incisors, including their buccal soft tissues and bone, are anesthetized when the incisive nerve block is administered.* An important indication for the incisive nerve block is when the contemplated procedure involves both the right and left sides of the mandible. It is this author’s belief that bilateral inferior alveolar or mandibular nerve blocks are seldom needed (except in the case of bilateral surgical procedures in the mandible) because of the degree of discomfort and the inconvenience experienced by the patient both during and after the procedure. Where dental treatment involves bilateral procedures on mandibular premolars and anterior teeth, bilateral incisive nerve blocks can be administered. Pulpal, buccal soft tissue, and bone anesthesia is readily obtained. Lingual soft tissues are not anesthetized with this block. If lingual soft tissues in very isolated areas require anesthesia, local infiltration can be readily accomplished by advancing a 27-gauge short needle through the interdental papillae on both mesial and distal aspects of the tooth being treated. Because the buccal soft tissues are already anesthetized (incisive nerve block), the penetration is atraumatic. Local anesthetic solution should be deposited as the needle is advanced through the tissue toward the lingual (Fig. 14-32). This technique provides lingual soft tissue anesthesia adequate for deep curettage, root planing, and subgingival preparations. Where there is a significant requirement for lingual soft tissue anesthesia, an inferior alveolar or mandibular nerve block should be administered on that side, with the incisive nerve block administered on the contralateral side. In this manner, the patient does not have to endure bilateral anesthesia of the tongue, which is a very disconcerting experience for many patients.

Figure 14-32 To obtain lingual anesthesia, after the incisive nerve block, insert the needle interproximally from buccal, and deposit anesthetic as the needle is advanced toward lingual.

Another method of obtaining lingual anesthesia after the incisive nerve block is to administer a partial lingual nerve block (Fig. 14-33). Using a 25-gauge long needle, deposit 0.3 to 0.6 mL of local anesthetic under the lingual mucosa just distal to the last tooth to be treated. This provides lingual soft tissue anesthesia adequate for any dental procedure in this area. The danger in this procedure is that the lingual nerve may be contacted by the needle provoking a sensation of an “electric shock” or varying degrees of paresthesia.

Figure 14-33 Retract the tongue to gain access to, and increase the visibility of, the lingual border of the mandible.

It is not necessary for the needle to enter into the mental foramen for an incisive nerve block to be successful. The first edition of this book and other textbooks of local anesthesia for dentistry recommended insertion of the needle into the foramen.38,41,42 At least two disadvantages are associated with the needle entering into the mental foramen: (1) The administration of an incisive nerve block becomes technically more difficult, and (2) the risk of traumatizing the mental or incisive nerves and their associated blood vessels is increased. As described in the following sections, for the incisive nerve block to be successful, the anesthetic should be deposited just outside the mental foramen and, under pressure, directed into the foramen. Indeed, the incisive nerve block may be considered the mandibular equivalent of the anterior superior alveolar nerve block, with the mental nerve block the equivalent of the infraorbital nerve block. Both of the disadvantages just mentioned are minimized by not entering into the mental foramen.

Indications

Disadvantages

1. Does not provide lingual anesthesia. The lingual tissues must be injected as described earlier if anesthesia is desired.

2. Partial anesthesia may develop at the midline because of nerve fiber overlap with the opposite side (extremely rare). Local infiltration of 0.9 mL of local anesthetic on both the buccal and lingual of the mandibular central incisors may be necessary for complete pulpal anesthesia to be obtained.

Technique

1. A 27-gauge short needle is recommended.

2. Area of insertion: Mucobuccal fold at or just anterior to the mental foramen

3. Target area: Mental foramen, through which the mental nerve exits and inside of which the incisive nerve is located

4. Landmarks: Mandibular premolars and mucobuccal fold

5. Orientation of the bevel: Toward bone during the injection

a. Assume the correct position.

(1) For a right or left incisive nerve block and a right-handed administrator, sit comfortably in front of the patient so that the syringe may be placed into the mouth below the patient’s line of sight (see Fig. 14-28).

(1) Supine is recommended, but semisupine is acceptable.

(2) Request that the patient partially close; this allows for easier access to the injection site.

(1) Place your thumb or index finger in the mucobuccal fold against the body of the mandible in the first molar area.

(2) Move it slowly anteriorly until you feel the bone become irregular and somewhat concave.

(a) The bone posterior and anterior to the mental foramen feels smooth; however, the bone immediately around the foramen feels rougher to the touch.

(b) The mental foramen is usually found at the apex of the second premolar. However, it may be found anterior or posterior to this site.

(c) The patient may comment that finger pressure in this area produces soreness as the mental nerve is compressed against bone.

(3) If radiographs are available, the mental foramen may be located easily (see Fig. 14-30).

d. Prepare tissues at the site of penetration.

e. With your left index finger, pull the lower lip and buccal soft tissue laterally (Fig. 14-35).

f. Orient the syringe with the bevel toward bone.

g. Penetrate mucous membrane at the canine or first premolar, directing the needle toward the mental foramen.

h. Advance the needle slowly until the mental foramen is reached. The depth of penetration is 5 to 6 mm. There is no need to enter the mental foramen for the incisive nerve block to be successful.

j. If negative, slowly deposit 0.6 mL (approximately one third of a cartridge) over 20 seconds.

(1) During the injection, maintain gentle finger pressure directly over the injection site to increase the volume of solution entering into the mental foramen. This may be accomplished with intraoral or extraoral pressure.

(2) Tissues at the injection site should balloon, but very slightly.

k. Withdraw the syringe and immediately make the needle safe.

l. Continue to apply pressure at the injection site for 2 minutes.

m. Wait 3 to 5 minutes before commencing the dental procedure.

Signs and Symptoms

Precaution

Usually an atraumatic injection unless the needle contacts periosteum or solution is deposited too rapidly.

Failures of Anesthesia

1. Inadequate volume of anesthetic solution in the mental foramen, with subsequent lack of pulpal anesthesia. To correct: Reinject into the proper region and apply pressure to the injection site.

2. Inadequate duration of pressure after injection. It is necessary to apply firm pressure over the injection site for a minimum of 2 minutes to force the local anesthetic into the mental foramen and provide anesthesia of the second premolar, which may be distal to the foramen. Failure to achieve anesthesia of the second premolar is usually caused by inadequate application of pressure after the injection.

Complications

2. Hematoma (bluish discoloration and tissue swelling at injection site). Blood may exit the needle puncture site into the buccal fold. To treat: Apply pressure with gauze directly to the area for 2 minutes. This is rarely a problem because proper incisive nerve block protocol includes the application of pressure at the injection site for 2 minutes.

3. Paresthesia of lip and/or chin. Contact of the needle with the mental nerve as it exits the mental foramen may lead to the sensation of an “electric shock” or to varying degrees of paresthesia (rare).

Table 14-1 summarizes the various injection techniques applicable for mandibular teeth. Table 14-2 summarizes the recommended volumes for the various injection techniques.

References

1. De St Georges, J. How dentists are judged by patients. Dent Today. 2004;23:96. [98–99].

2. Friedman, MJ, Hochman, MN. The AMSA injection: a new concept for local anesthesia of maxillary teeth using a computer-controlled injection system. Quintessence Int. 1998;29:297–303.

3. Oulis, CJ, Vadiakis, GP, Vasilopoulou, A. The effectiveness of mandibular infiltration compared to mandibular block anesthesia in treating primary molars in children. Pediatr Dent. 1996;18:301–305.

4. Sharaf, AA. Evaluation of mandibular infiltration versus block anesthesia in pediatric dentistry. J Dent Child. 1997;64:276–281.

5. Malamed, SF. Local anesthetic considerations in dental specialties. In Malamed SF, ed.: Handbook of local anesthesia, ed 5, St Louis: CV Mosby, 2004.

6. Bennett, CR. Techniques of regional anesthesia and analgesia. In Bennett CR, ed.: Monheim’s local anesthesia and pain control in dental practice, ed 7, St Louis: CV Mosby, 1984.

7. Evers, H, Haegerstam, G. Anaesthesia of the lower jaw. In: Evers H, Haegerstam G, eds. Introduction to dental local anaesthesia. Fribourg, Switzerland: Mediglobe SA, 1990.

8. Trieger, N, New approaches to local anesthesia. Pain control, ed 2. . CV Mosby: St Louis, 1994.

9. OnPharma Inc. Results of 38 studies on LA success rates, unpublished. Available at www.onpharma.com.

10. Kanaa, MD, Whitworth, JM, Corbett, IP, et al. Articaine buccal infiltration enhances the effectiveness of lidocaine inferior alveolar nerve block. Int Endod J. 2009;42:238–246.

11. Hannan, L, Reader, A, Nist, R, et al. The use of ultrasound for guiding needle placement for inferior alveolar nerve blocks. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:658–665.

12. Berns, JM, Sadove, MS. Mandibular block injection: a method of study using an injected radiopaque material. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;65:736–745.

13. Galbreath, JC. Tracing the course of the mandibular block injection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1970;30:571–582.

14. Reader A, American Association of Endodontists: Taking the pain out of restorative dentistry and endodontics: current thoughts and treatment options to help patients achieve profound anesthesia, Endodontics: Colleagues for Excellence. Winter 2009.

15. DeJong, RH. Local anesthetics. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1994.

16. Strichartz, G. Molecular mechanisms of nerve block by local anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 1976;45:421–444.

17. Gow-Gates, GA. Mandibular conduction anesthesia: a new technique using extraoral landmarks. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;36:321–328.

18. Akinosi, JO. A new approach to the mandibular nerve block. Br J Oral Surg. 1977;15:83–87.

19. Malamed, SF. The periodontal ligament (PDL) injection: an alternative to inferior alveolar nerve block. Oral Surg. 1982;53:117–121.

20. Coggins, R, Reader, A, Nist, R, et al. Anesthetic efficacy of the intraosseous injection in maxillary and mandibular teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1996;81:634–641.

21. Whitcomb, M, Drum, M, Reader, A, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study of the anesthetic efficacy of sodium bicarbonate buffered 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine in inferior alveolar nerve blocks. Anesth Prog. 2010;57:59–66.

22. Meechan, JG, Ledvinka, JI. Pulpal anaesthesia for mandibular central incisor teeth: a comparison of infiltration and intraligamentary injections. Int Endod J. 2002;35:629–634.

23. Kanaa, MD, Whitworth, JM, Corbett, IP, et al. Articaine and lidocaine mandibular buccal infiltration anesthesia: a prospective randomized double-blind cross-over study. J Endod. 2006;32:296–298.

24. Robertson, D, Nusstein, J, Reader, A, et al. The anesthetic efficacy of articaine in buccal infiltration of mandibular posterior teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:1104–1112.

25. Haase, A, Reader, A, Nusstein, J, et al. Comparing anesthetic efficacy of articaine versus lidocaine as a supplemental buccal infiltration of the mandibular first molar after an inferior alveolar nerve block. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1228–1235.

26. Kanaa, MD, Whitworth, JM, Corbett, IP, et al. Articaine buccal infiltration enhances the effectiveness of lidocaine inferior alveolar nerve block. Int Endod J. 2009;42:238–246.

27. Dreven, LJ, Reader, A, Beck, M, et al. An evaluation of the electric pulp tester as a measure of analgesia in human vital teeth. J Endod. 1987;13:233–238.

28. Certosimo, AJ, Archer, RD. A clinical evaluation of the electric pulp tester as an indicator of local anesthesia. Oper Dent. 1996;21:25–30.

29. Wilson, S, Johns, PI, Fuller, PM. The inferior alveolar and mylohyoid nerves: an anatomic study and relationship to local anesthesia of the anterior mandibular teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;108:350–352.

30. Frommer, J, Mele, FA, Monroe, CW. The possible role of the mylohyoid nerve in mandibular posterior tooth sensation. J Am Dent Assoc. 1972;85:113–117.

31. Roda, RS, Blanton, PL. The anatomy of local anesthesia. Quintessence Int. 1994;25:27–38.

32. Meechan, JG. Infiltration anesthesia in the mandible. Dent Clin N Am. 2010;54:621–629.

33. Gow-Gates, GAE. Mandibular conduction anesthesia: a new technique using extraoral landmarks. Oral Surg. 1973;36:321–328.

34. Malamed, SF. The Gow-Gates mandibular block: evaluation after 4275 cases. Oral Surg. 1981;51:463.

35. Fish, LR, McIntire, DN, Johnson, L. Temporary paralysis of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI after a Gow-Gates injection. J Am Dent Assoc. 1989;119:127–130.

36. Akinosi, JO. A new approach to the mandibular nerve block. Br J Oral Surg. 1977;15:83–87.

37. Murphy, TM. Somatic blockade. In: Cousins MJ, Bridenbaugh PO, eds. Neural blockade in clinical anesthesia and management of pain. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1980.

38. Bennett, CR. Monheim’s local anesthesia and pain control in dental practice, ed 6. St Louis: Mosby; 1978.

39. Vazirani, SJ. Closed mouth mandibular nerve block: a new technique. Dent Dig. 1960;66:10–13.

40. Wolfe, SH. The Wolfe nerve block: a modified high mandibular nerve block. Dent Today. 1992;11:34–37.

41. Malamed, SF. Handbook of local anesthesia. St Louis: Mosby; 1980.

42. Jastak, JT, Yagiela, JA, Donaldson, D. Local anesthesia of the oral cavity. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995.

*The pterygomandibular raphe continues posteriorly in a horizontal plane from the retromolar pad before turning vertically toward the palate; only the vertical portion of the pterygomandibular raphe is used as an indicator of the posterior border of the ramus.

*Because the buccal nerve block most often immediately follows an inferior alveolar nerve block, steps (1), (2), and (3) of tissue preparation usually are completed before the inferior alveolar block.

*If an inadequate volume of solution remains in the cartridge, it may be necessary to remove the syringe from the patient’s mouth and reload it with a new cartridge.

*The second premolar may not be anesthetized with this technique if the mental foramen lies beneath the first premolar.