Supplemental Injection Techniques

In this chapter, a number of injections are described that are used in specialized clinical situations. Some may be used as the sole technique for pain control for certain types of dental treatment. For example, the periodontal ligament (PDL) injection and intraosseous (IO) and intraseptal techniques provide effective pulpal anesthesia for a single tooth without the need for other injections. On the other hand, use of the intrapulpal injection is almost always reserved for situations in which other injection techniques have failed or are contraindicated for use. The PDL, IO, and intraseptal techniques also are frequently used to supplement failed or only partially successful traditional injection techniques.

Since the previous edition of this textbook was published (2004), considerable interest has arisen in the effectiveness of mandibular infiltration in the adult mandible with the local anesthetic articaine HCl. The ability to provide pulpal anesthesia in circumscribed areas of the mandible without the need for nerve blocks (e.g., inferior alveolar nerve block [IANB], Gow-Gates) is valuable when these nerve blocks fail to provide the depth of anesthesia required for painless dentistry.

Intraosseous Anesthesia

IO anesthesia involves the deposition of local anesthetic solution into the cancellous bone that supports the teeth. Although not new (IO anesthesia dates back to the early 1900s), a resurgence of interest in this technique in dentistry has occurred over the past 15 years.1-5 Three techniques are discussed here, two of which—the PDL injection and the intraseptal injection—are modifications of traditional IO anesthesia.

Periodontal Ligament Injection

Because of the thickness of the cortical plate of bone in most patients and in most areas of the mandible, it is not possible to achieve profound pulpal anesthesia on a solitary tooth in the adult mandible with the techniques described in Chapter 14. An exception to this is the mandibular incisor region, where Certosimo demonstrated a 97% success rate for pulpal anesthesia with infiltration of 0.9 mL of articaine HCl (with epinephrine 1 : 100,000) on BOTH the buccal and lingual aspects of the teeth.6 Some success is achievable in the posterior teeth as well.7,8 Mandibular infiltration is reviewed later in this chapter.

An old technique has been repopularized. The PDL injection (also known as the intraligamentary injection [ILI]) was originally described as the peridental injection in local anesthesia textbooks dating from 1912 to 1923.9,10

The peridental injection was not well received in those early years because it was claimed that the risk of producing blood-borne infection and septicemia was too great to warrant its use in patients. The technique never became popular but was used clinically by many doctors, although it was not referred to as the peridental technique. In clinical situations in which an inferior alveolar nerve block failed to provide adequate pulpal anesthesia to the first molar (usually its mesial root), the doctor inserted a needle along the long axis of the mesial root as far apically as possible and deposited a small volume of local anesthetic solution under pressure. This invariably provided effective pain control.

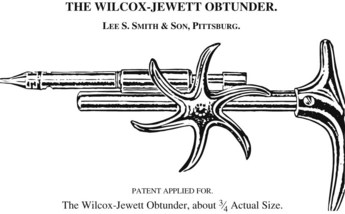

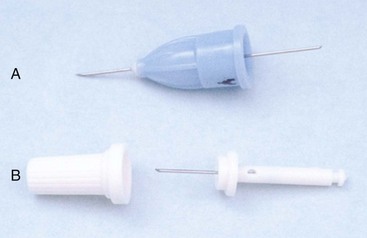

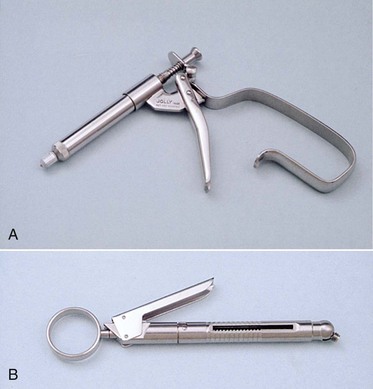

It was not until the early 1980s that the intraligamentary or PDL injection regained popularity. Credit for increased interest in this approach must go to the manufacturers of syringe devices designed to make the injection easier to administer. The original devices—the Peripress (Universal Dental, Boyerstown, Pa) and the Ligmaject (IMA Associates, Largo, Fla) (Fig. 15-1)—provide a mechanical advantage that allows the administrator to deposit the anesthetic more easily (and sometimes too easily). They appear similar to the Wilcox-Jewett Obtunder (Fig. 15-2), which was widely advertised to the dental profession in a 1905 catalog, Dental Furniture, Instruments, and Materials, perhaps reconfirming the adage that there is “nothing new under the sun.”11

Figure 15-1 A, Original pressure syringe designed for a periodontal ligament or intraligamentary injection. B, Second-generation syringe for a periodontal ligament injection.

Why has the PDL (née peridental) injection enjoyed a renewal of popularity? Perhaps it is because the primary thrust of advertising for the new syringes focused on being able to “avoid the mandibular block” injection with the PDL or intraligamentary technique, a concept to which the dental profession is receptive, given the fact that virtually all dentists have experienced periods when they have been unable to achieve adequate anesthesia with the inferior alveolar nerve block (a “mandibular slump”).

The PDL injection also may be used successfully in the maxillary arch; however, with the ready availability of other highly effective and atraumatic techniques, such as the supraperiosteal (infiltration) injection, and drugs such as articaine HCl to provide single-tooth pulpal anesthesia, there has been little compelling reason for use of the PDL in the upper jaw (although there is absolutely no other reason not to recommend it in this area). Possibly the greatest potential benefit of the PDL injection lies in the fact that it provides pulpal and soft tissue anesthesia in a localized area (one tooth) of the mandible without producing extensive soft tissue (e.g., tongue and lower lip) anesthesia as well. Virtually all dental patients prefer this technique to any of the “mandibular nerve blocks.” In a clinical trial, Malamed reported that 74% of patients preferred the PDL injection primarily because of its lack of lingual and labial soft tissue anesthesia.12 It is interesting that those who preferred the inferior alveolar nerve block did so for an important reason: With the IANB, once the lip and tongue became numb, patients were able to relax, knowing that the remainder of their dental treatment would not hurt. Without lingual and labial soft tissue anesthesia in the PDL technique, patients were unable to fully relax because they were never certain that they had been adequately anesthetized.

Primary indications for the PDL injection include (1) the need for anesthesia of but one or two mandibular teeth in a quadrant, (2) treatment of isolated teeth in both mandibular quadrants (to avoid bilateral inferior alveolar nerve block), (3) treatment of children (because residual soft tissue anesthesia increases the risk of self-inflicted soft tissue injury), (4) treatment in which nerve block anesthesia is contraindicated (e.g., in hemophiliacs), and (5) its use as a possible aid in the diagnosis (e.g., localization) of mandibular pain.

Contraindications to the PDL injection include infection or severe inflammation at the injection site and the presence of primary teeth. Brannstrom and associates reported the development of enamel hypoplasia or hypomineralization or both in 15 permanent teeth after administration of the periodontal ligament injection.13 Fortunately, there is rarely a need for the PDL injection in the primary dentition; other techniques, such as infiltration and nerve blocks, are effective and easy to administer.

Several concerns have been expressed about this technique, most of which were addressed in a status report on the PDL injection in the Journal of the American Dental Association in 1983.14 Two of these concerns involve (1) the effect of injection and deposition of the local anesthetic under pressure into the confined space of the PDL, and (2) the effect of the drug or vasoconstrictor on pulpal tissues. Walton and Garnick concluded that the PDL injection (administered with a conventional syringe) causes slight damage to tissues in the region of needle penetration only.15 Apical areas appeared normal; the epithelial and connective tissue attachment to enamel and cementum was not disturbed by the needle puncture; slight resorption of nonvital bone occurred in the crestal regions, forming a wedge-shaped defect; soft tissue damage was minimal; the disruption of tissue that did occur showed repair in 25 days, with absence of inflammation and with the formation of new bone in the regions of resorption; and injection of the solution was not in itself damaging. Damage produced by needle penetration alone (no drug administered) appeared similar to that seen when a drug had been deposited with the injection. The authors concluded that the PDL injection is safe to the periodontium.15 In addition, no evidence to date suggests that inclusion of a vasoconstrictor in the local anesthetic solution has any detrimental effect on pulpal microcirculation after the PDL injection.

It appears that the mechanism whereby local anesthetic solution reaches the periapical tissues with the PDL injection consists of diffusion apically and into the marrow spaces surrounding the teeth. The solution is not forced apically through the periodontal tissues, a procedure that might lead (as Nelson reported) to avulsion of a tooth (premolar) because of the increased hydrostatic pressure exerted in a confined space.16 Therefore the PDL injection appears to produce anesthesia in much the same way as IO and intraseptal injections—by diffusion of anesthetic solution apically through marrow spaces in the intraseptal bone (Fig. 15-3).17,18

Figure 15-3 Periodontal ligament injection is intraosseous. Note the dispersion of ink into surrounding bone.

Postinjection complications are also of concern with the PDL injection. Reported complications have included mild to severe postoperative discomfort, swelling and discoloration of soft tissues at the injection site, and prolonged ischemia of the interdental papilla, followed by sloughing and exposure of crestal bone.19,20 Some of these complications result directly from poor operator technique, lack of familiarity with the pressure syringe, and injection of excessive volumes of local anesthetic into the PDL. The most frequently voiced postinjection complications are mild discomfort and sensitivity to biting and percussion for 2 or 3 days. The most common causes of postinjection discomfort are (1) too rapid injection (producing edema and slight extrusion of the tooth, thus sensitivity on biting), and (2) injection of excessive volumes of local anesthetic into the site.

Before the PDL technique is described, it must be mentioned that although “special” PDL syringes can be used effectively and safely, usually there is no need for them. A conventional local anesthetic syringe is equally effective in providing PDL anesthesia. Use of a conventional syringe requires that the administrator apply significant force to deposit the local anesthetic into the periodontal tissues. Virtually all doctors and most hygienists are able to produce PDL anesthesia successfully without a special PDL syringe. Only when a doctor or a hygienist is unable to achieve adequate PDL anesthesia with a conventional syringe is use of a PDL syringe recommended.

Arguments against using the conventional syringe for PDL injections (and my rebuttals) include the following:

1. It is too difficult to administer the solution with a conventional syringe.

Comment: Slow administration of the local anesthetic makes the PDL injection atraumatic. Improper use (fast injection) of the PDL syringe produces both immediate and postinjection pain.

2. The extreme pressure applied to the glass may shatter the cartridge. PDL syringes provide a metal or plastic covering for the glass cartridge, thereby protecting the patient from shards of glass should the cartridge shatter during injection.

Comment: Although I have read and heard of cartridges shattering during PDL injection, I have yet to experience this personally. However, the risk can be minimized in several ways: Because only small volumes of solution are injected (0.2 mL per root), a full, 1.8 mL cartridge is not necessary. Eliminate all but about 0.6 mL of solution before starting the PDL injection. This minimizes the area of glass being subjected to increased pressures, decreasing the risk of breakage. In addition, glass cartridges have a thin Mylar plastic label that covers most or all of the glass. If a cartridge breaks, the glass will not shatter but will be contained by the plastic covering.

3. Many manufacturers of PDL syringes recommend use of 30-gauge short or ultrashort needles in this technique.

Comment: In my early experience with the PDL technique, I used the 30-gauge needle only to find that whenever pressure was applied to it (as when pushing it apically into the PDL), the 30-gauge needle bent easily. It was too fragile to withstand pressure without bending. PDL injection failure rates were excessive. A 30-gauge ultrashort needle was manufactured specifically for use with this injection technique (10 mm length). Although somewhat more effective than the 30-gauge short, there was no need to use a “special” needle for this injection. I have had great clinical success, with no increase in patient discomfort, using the more readily available 27-gauge short needle.

In summary, the PDL injection is an important component of the armamentarium of local anesthetic techniques for providing mandibular and, to a lesser degree, maxillary pain control.

4. The PDL injection administered with a conventional or PDL syringe is painful.

Comment: Use of a computer-controlled local anesthetic delivery (C-CLAD) device for administration of painless PDL injections has been strongly advocated.21 Many dentists have related to me that their PDL injections, although effective in providing anesthesia, are painful to the patient during administration. Although this has not been my experience, there are enough reports to convince me that many doctors believe this to be so. Use of C-CLAD systems (e.g., STA-Single Tooth Anesthesia System, Milestone Scientific, Inc., Livingston, NJ) does enable the PDL injection to be delivered painlessly (e.g., 0 to 1 on a visual analog scale [VAS]). The PDL technique utilizing a C-CLAD device is described in detail in the section immediately following this.

Areas Anesthetized

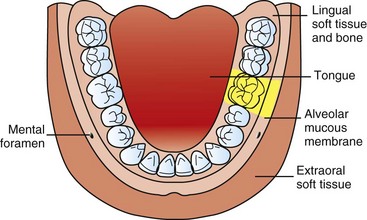

Bone, soft tissue, and apical and pulpal tissues in the area of injection (Fig. 15-4).

Indications

1. Pulpal anesthesia of one or two teeth in a quadrant

2. Treatment of isolated teeth in two mandibular quadrants (to avoid bilateral IANB)

3. Patients for whom residual soft tissue anesthesia is undesirable

4. Situations in which regional block anesthesia is contraindicated

5. As a possible aid in the diagnosis of pulpal discomfort

6. As an adjunctive technique after nerve block anesthesia if partial anesthesia is present

Contraindications

1. Infection or inflammation at the site of injection

2. Primary teeth when the permanent tooth bud is present13

a. Enamel hypoplasia has been reported to occur in a developing permanent tooth when a PDL injection was administered to the primary tooth above it.

b. There appears to be little reason for use of the PDL technique in primary teeth because infiltration anesthesia and the incisive nerve block are effective in primary dentition.

3. Patient who requires a “numb” sensation for psychological comfort

Advantages

1. There is no anesthesia of the lip, tongue, and other soft tissues, thus facilitating treatment in multiple quadrants during a single appointment.

2. Minimum dose of local anesthetic necessary to achieve anesthesia (0.2 mL per root)

3. An alternative to partially successful regional nerve block anesthesia

4. Rapid onset of profound pulpal and soft tissue anesthesia (30 seconds)

5. Less traumatic than conventional block injections

6. Well suited for procedures in children, extractions, and periodontal and endodontic single-tooth and multiple-quadrant procedures

Disadvantages

1. Proper needle placement is difficult to achieve in some areas (e.g., distal of the second or third molar).

2. Leakage of local anesthetic solution into the patient’s mouth produces an unpleasant taste.

3. Excessive pressure or overly rapid injection may break the glass cartridge.

4. A special syringe may be necessary.

5. Excessive pressure can produce focal tissue damage.

6. Postinjection discomfort may persist for several days.

7. The potential for extrusion of a tooth exists if excessive pressure or volumes are used.

Technique

1. A 27-gauge short needle is recommended.

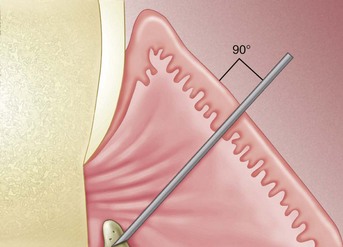

2. Area of insertion: Long axis of the tooth to be treated on its mesial or distal root (one-rooted tooth) or on the mesial and distal roots (of multirooted tooth) interproximally (Fig. 15-5)

3. Target area: depth of the gingival sulcus

5. Orientation of the bevel: Although not significant to the success of the technique, it is recommended that the bevel of the needle face toward the root to permit easy advancement of the needle in an apical direction.

a. Assume the correct position. (This varies significantly with PDL injections on different teeth.) Sit comfortably, have adequate visibility of the injection site, and maintain control over the needle. It may be necessary to bend the needle to achieve the proper angle, especially on the distal aspects of second and third molars.*

b. Position the patient supine or semisupine, with the head turned to maximize access and visibility.

c. Stabilize the syringe and direct it along the long axis of the root to be anesthetized.

(1) The bevel faces the root of the tooth.

(2) If interproximal contacts are tight, the syringe should be directed from the lingual or buccal surface of the tooth but maintained as close to the long axis as possible.

(3) Stabilize the syringe and your hand against the patient’s teeth, lips, or face.

d. With the bevel of the needle on the root, advance the needle apically until resistance is met.

e. Deposit 0.2 mL of local anesthetic solution in a minimum of 20 seconds.

(1) When using a conventional syringe, note that the thickness of the rubber stopper in the local anesthetic cartridge is equal to 0.2 mL of solution. This may be used as a gauge for the volume of local anesthetic to be administered.

(2) With a PDL syringe, each squeeze of the “trigger” provides a volume of 0.2 mL.

f. There are two important indicators of success of the injection:

(1) Significant resistance to the deposition of local anesthetic solution

(a) This is especially noticeable when the conventional syringe is used; resistance is similar to that felt with the nasopalatine injection and is thought to be the reason for reports of PDL injections being painful.

(b) The local anesthetic should not flow back into the patient’s mouth. If this happens, repeat the injection at the same site but from a different angle. Two tenths of a milliliter of solution must be deposited and must remain within the tissues for the PDL to be effective.

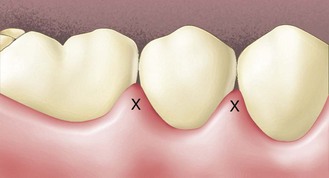

(2) Ischemia of the soft tissues adjacent to the injection site. (This is noted with all local anesthetic solutions but is more prominent with vasoconstrictor-containing local anesthetics.)

g. If the tooth has only one root, remove the syringe from the tissue and cap the needle. Dental treatment usually may start within 30 seconds.

h. If the tooth is multirooted, remove the needle and repeat the procedure on the other root(s).

Signs and Symptoms

1. Subjective: There are no signs that absolutely assure adequate anesthesia; the anesthetized area is quite circumscribed. When the following two signs are present, there is an excellent chance that profound anesthesia is present:

a. Ischemia of soft tissues at the injection site

b. Significant resistance to injection of solution (with a traditional syringe)

2. Objective: Use of electrical pulp testing (EPT) with no response from the tooth with maximal EPT output (80/80)

Precautions

1. Keep the needle against the tooth to prevent overinsertion into soft tissues on the lingual aspect.

2. Do not inject too rapidly (minimum 20 seconds for 0.2 mL).

3. Do not inject too much solution (0.2 mL per root retained within tissues).

4. Do not inject directly into infected or highly inflamed tissues.

Failures of Anesthesia

1. Infected or inflamed tissues. The pH and vascularity changes at the apex and periodontal tissues minimize the effectiveness of the local anesthetic.

2. Solution not retained. In this case, remove the needle and reenter at a different site(s) until 0.2 mL of local anesthetic is deposited and retained in the tissues.

Complications

1. Pain during insertion of the needle

2. Pain during injection of solution

Duration of Expected Anesthesia

The duration of pulpal anesthesia obtained with a successful PDL injection is quite variable and is not related to the drug administered. Administration of lidocaine with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine, for example, provides pulpal anesthesia ranging in duration from 5 to 55 minutes. The PDL injection may be repeated if necessary to permit completion of the dental procedure. It appears that the volume of anesthetic solution used with the PDL is too small to provide the usually expected duration of anesthesia of the drug. The question of anesthetic volume is discussed further in the following description of PDL injections given using a C-CLAD device.

STA-Intraligamentary (PDL) Injection

The technique used to perform the PDL injection, as described previously, has remained relatively unchanged since it was first introduced in the early 1900s.22 A variety of mechanical syringes have been developed throughout the years to enable high pressures to be generated during the administration of anesthetic solution into these tissues.23 These mechanical syringes produce considerably high pressures, thereby creating a pressure gradient to promote diffusion of anesthetic solution from the coronal region of the crestal bone to the apex of the tooth. The anesthetic solution diffuses through the cortical and medullary bone to eventually surround or envelope the neurovascular bundle at the apex of a tooth.24,25 This localized “bathing” of the nerve entering into the apex of a tooth provides anesthesia of a single tooth without the often undesirable collateral anesthesia of the lip and tongue. Additionally, this localized administration has a rapid onset because of the localized nature of the injection technique. With the production of high pressures, only a small volume (typically 0.2 to 0.4 mL) can be injected and absorbed.18 Last, patients routinely report moderate to severe discomfort when injections are performed using high-pressure syringe techniques.26,27

With the introduction of the STA-Single Tooth Anesthesia System C-CLAD device, a change in the basic concepts related to performing the PDL injection occurred as a result of the mechanical and technological differences between a hand-driven mechanical syringe versus a computer-regulated electromechanical instrument.28 The difference between the STA System versus a hand-driven syringe is that in the former, a precisely regulated flow rate and controlled low-pressure injection are used to perform the intraligamentary injection.29 These fundamental changes in fluid dynamics have led to the following clinically relevant changes: a consistent and measurable reduction in patient pain perception,30,31 a histologically demonstrated reduction in tissue damage, and the ability to administer larger volumes of anesthetic safely and effectively when the PDL injection is performed.32 The ability to administer a larger volume of anesthetic solution results in an increased duration of effective dental local anesthesia.33 In addition, the STA System incorporates a new technology that allows the PDL injection to be performed as a “guided” injection by providing real-time feedback during positioning of the needle in the intended target area, thereby improving the efficacy and predictability of PDL injection.34,35

The STA System precisely regulates and measures fluid pressure at the needle tip while a subcutaneous injection is performed, providing the clinician with continuous real-time audible and visual feedback during the injection.32

Clinical studies in medicine and dentistry have demonstrated that using real-time exit-pressure sensing allows identification of a specific tissue type related to objective measurement of tissue density (i.e., tissue compliance) while a subcutaneous injection is performed.30,36-38 One study led researchers to the use of this technology to more accurately identify tissue type and to perform the epidural nerve block technique commonly used for obstetric and surgical procedures of the lower extremities.38 Hochman and coworkers published the results of a clinical study in which more than 200 dental injections were given using dynamic pressure-sensing technology to differentiate specific tissues of the oral cavity: periodontal ligament, attached gingiva, and unattached gingival mucosal tissues.30 Investigators concluded that specific tissue types require a specific pressure range with a given flow rate to be used to perform a safe and effective dental injection.

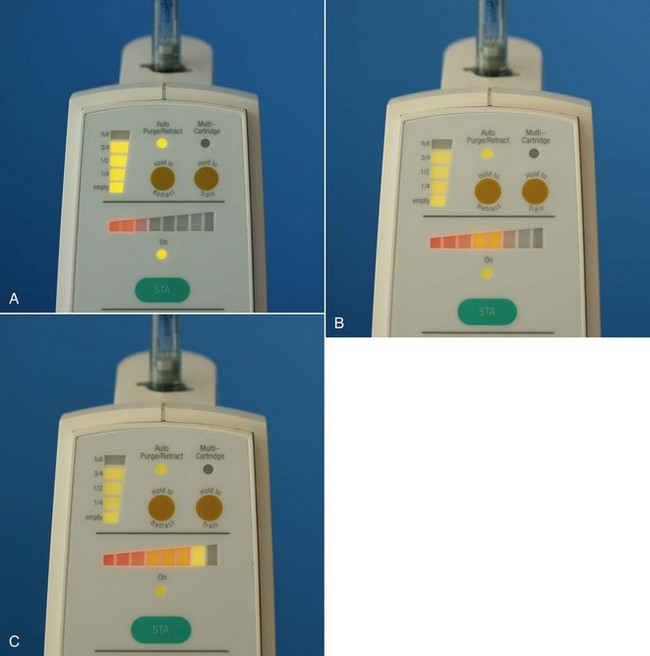

The STA instrument provides continuous audible and visual feedback to the clinician as the dental needle is introduced into the tissues during the injection. This system has a visual pressure-sensing scale on the front of the unit that is composed of a series of light-emitting diode (LED) lights (orange, yellow, and green) (Fig. 15-6, A-C). Orange lights indicate minimal pressure at the needle tip, yellow indicates mild to moderate pressure, and green indicates moderate tissue pressure indicative of the PDL space. PDL tissue may be identified at pressures of the yellow LED at high range as well.39

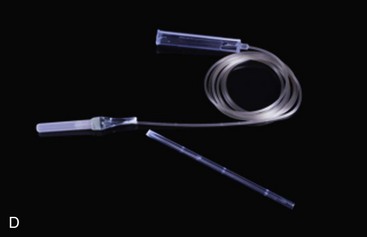

Figure 15-6 Dynamic Pressure Sensing (DPS) on the STA Single Tooth Anesthesia C-CLAD device provides both visual and audible feedback regarding placement of the needle tip during the periodontal ligament (PDL) injection. Horizontal color bars indicate pressure at the tip of the needle. A, Red—pressure is too low. B, Orange and dark yellow—increasing pressure but not yet adequate. C, Light yellow—correct pressure for PDL injection. At this point (C) the STA unit will also provide an audible clue “PDL. PDL, PDL” that the needle tip is properly situated. STA Wand handpiece is lightweight (less than 10 grams) and can easily be shortened to aid in administration of some injections (D), such as the AMSA or other palatal techniques.

Through auditory feedback, the clinician becomes aware of how to maintain correct needle-to-intraligamentary position throughout the injection. Auditory feedback consists of a series of sounds with a pressure-sensing scale composed of ascending tones to guide the clinician. When the clinician hears the ascending sequence, this indicates that the pressure is rising. When the periodontal ligament is identified, the letters “P-D-L” are spoken, indicating that correct needle position has been achieved. Maintaining a consistent level of moderate pressure throughout the injection process is necessary for success. Audible and visual feedback provides this important information. When the STA-PDL injection is performed, it is not uncommon for the clinician to reposition the needle to find the optimal position within periodontal ligament tissues, allowing a high degree of predictability and accuracy when this injection is performed. This transforms the “blind” syringe approach, described above, into an objective method of locating and maintaining correct needle position when performing the PDL injection.

Ferrari and coworkers published data on 60 patients in whom they compared the STA System versus two standard PDL hand-driven manual syringes: a high-pressure mechanical syringe (Ligmaject) and a conventional dental syringe.32 Electrical pulp testing was performed on all tested teeth at regular intervals to determine success or failure of these different instruments and the techniques used. In addition to EPT results, subjective pain responses of the patient were recorded after treatment. Ferrari reported a success rate of 100% for the STA System. In addition, a rapid onset of anesthesia was observed. In this study, the PDL injection was performed as the primary injection for restorative dental care in mandibular teeth. Investigators reported subjective pain responses of “minimal or no pain” in all patients receiving the PDL injection performed with the STA device. In contrast, injections performed with the other two systems (high-pressure mechanical syringe and conventional syringe) were found to result in higher pain scores throughout testing and required repeated attempts to achieve a successful outcome. Researchers concluded the STA System device resulted in a more predictable, more reliable, and more comfortable anesthesia technique than the high-pressure mechanical syringe and/or the conventional dental syringe.

Pediatric Use

Brannstrom and associates reported on the use of a high-pressure PDL injection to anesthetize 16 monkey primary teeth.13 Hypoplasia or hypomineralization defects developed on 15 of the permanent teeth, but none in controls. The PDL injection, when delivered by a hand-driven mechanical syringe, produces uncontrolled high pressures and is associated with damage to the periodontal tissues.40 Other reports have also recommended avoidance of the PDL injection on primary teeth when a traditional syringe or PDL syringe is used.13

In 2010, Ashekenzi and coworkers published the first long-term, clinical controlled study using a low-pressure PDL injection with the STA System with dynamic pressure-sensing (DPS) technology.31 The study population consisted of 78 children (ages, 4.1 to 12.8 years) who received STA intraligamentary injections in 166 primary molar teeth. Teeth receiving conventional dental anesthesia or that were not anesthetized by local anesthesia served as controls. After reviewing data collected between 1999 and 2007, Ashekenzi concluded that performing the PDL injection using a low-pressure C-CLAD injection instrument, specifically the STA System with DPS, did not produce damage to the underlying developing permanent tooth bud and was deemed safe and effective. The same authors, in another study, demonstrated that children exhibited minimal disruptive pain-related behavior and minimal levels of dental-related stress during and immediately after STA intraligamentary anesthesia.41 These findings represent a new perspective on dental local anesthesia and the treatment of primary teeth of the pediatric patient.

The PDL injection performed with the STA System device represents a single-tooth injection technique that provides a level of safety, comfort, and predictability previously unattainable. The system provides the clinician with multiple benefits that cannot be achieved with use of the manually driven conventional syringe, the pistol-grip high-pressure syringe, or previous C-CLAD instruments.

Indications

1. Pulpal anesthesia of one or two teeth in a quadrant

2. Treatment of isolated teeth in two mandibular quadrants (to avoid bilateral IANB)

3. Patients for whom residual soft tissue anesthesia is undesirable

4. Pediatric dental patient in treatment of the primary dentition

a. A recent study conclusively reported that using the STA System does not present the previous risk of enamel hypoplasia that was reported with a manually driven syringe, and that using the STA System instrument does not adversely affect the developing permanent tooth when PDL injection is performed.

5. Situations in which regional block anesthesia is contraindicated

6. As a possible aid in diagnosis of pulpal discomfort

7. As an adjunctive technique after nerve block anesthesia if partial anesthesia is present

Advantages

1. The STA System device with dynamic pressure-sensing technology provides an objective means by which to identify the correct target location to perform a PDL injection, improving the predictability of this injection when compared with previous techniques and instruments.

2. The STA System device uses a controlled low-pressure fluid dynamic that has been shown to reduce the risk of tissue injury and to minimize subjective pain responses.

3. The STA System device, through use of a controlled low-pressure fluid dynamic, allows a greater volume of anesthetic solution (0.45 mL to 0.90 mL) to be safely administered, thereby increasing the effective working time of this PDL injection (30 to 45 minutes).

4. The STA System device with dynamic pressure-sensing technology can detect local anesthetic solution leakage into the patient’s mouth, avoiding an unpleasant taste.

5. The STA System device with dynamic pressure-sensing technology can detect excessive pressure and can safeguard patient and operator from glass cartridge breakage.

Technique

1. A STA-Wand bonded handpiece with a 30-gauge  inch needle

inch needle

2. Set the STA instrument to the STA mode.

a. The needle should be placed at a 45-degree angle to the long axis of the tooth.

b. When a PDL injection is performed on a single-rooted tooth, only a single site is necessary.

c. When a PDL injection is performed on a multirooted tooth, it is recommended that two sites be used: one on the distal root and a second on the mesial root.

d. Start with the distal aspect of the tooth.

e. The injection can be performed anywhere from the lingual line angle to the interproximal contact for each root.

4. To improve accessibility in difficult areas, shorten the STA handpiece by breaking off a section of the handle. This will allow easier access (Fig. 15-6, D).

5. Place the needle very slowly into the gingival sulcus as if it was a periodontal probe, while simultaneously initiating the ControlFlo (0.005 mL/sec) flow rate. Advance the needle slowly into the sulcus, moving it gently down into the sulcus until you encounter resistance.

6. The ControlFlo rate can be initiated by pressing on the foot control; after three audible beeps, you will hear the unit announce “Cruise.” Once you hear the word “Cruise,” you may remove your foot. The STA system will continue the flow of anesthetic solution.

7. Once you feel you are at the base of the sulcus, you need to minimize movement for 10 to 15 seconds as the dynamic pressure-sensing technology analyzes the location of the needle tip.

8. As the STA system DPS senses pressure building, you will see a sequential illumination of LED lights on the front of the unit. The visual pressure sensing scale consists of a series of orange, yellow, and green LED lights. If after 20 to 30 seconds, pressure does not build, you will need to relocate the needle. The STA System also provides audible pressure feedback, with a series of three ascending tones indicating that the system is detecting pressure at the needle tip.

9. After 20 to 30 seconds with the needle tip in the correct location, the STA System will announce “P-D-L, P- D-L.” This will be followed by a series of two longer “beeps,” indicating that proper pressure is being maintained, and that you have identified the correct needle tip position for the PDL injection.

10. It is important to note that a successful PDL may occur when the LED lights are in green or high yellow zones. It is necessary to maintain the LED light indicators throughout the injection process to achieve success. Note that you will not hear the audible spoken word “PDL” in the yellow zone.

11. Deposit 0.45 mL to 0.90 mL of local anesthetic per root.

Signs and Symptoms

Subjective: There are no signs that absolutely assure adequate anesthesia; the anesthetized area is quite circumscribed. When the following sign is present, there is an excellent chance that profound anesthesia is present:

Subjective: Ischemia of soft tissues at the injection site

Subjective: Maintenance of high yellow and green LED zones on the front of the STA drive unit throughout the injection process

2. Objective: Use of electrical pulp testing (EPT) with no response from the tooth with maximal EPT output (80/80)

Safety Feature

The STA System instrument DPS technology precisely regulates and monitors fluid exit-pressures within the tissues, thereby preventing buildup of excessive pressure and ensuring a safe and effective controlled flow rate of local anesthetic solution.

Precautions

1. Maintain direct vision of the needle as it enters the sulcus of the tooth.

2. Keep the needle at a 45-degree angle to the long axis of the tooth to ensure that the needle is inserted into the entrance to the PDL space at the level of the crest of bone.

3. Do not inject directly into infected or highly inflamed tissues.

Failures of Anesthesia

1. Infected or inflamed tissues. The pH and vascularity changes at the apex of, and periodontal tissues surrounding, infected teeth minimize the effectiveness of the local anesthetic.

2. Inability to generate STA System in the high yellow or green LED zone. In this case, remove and reenter at a different site(s) until the STA System can generate and maintain the proper DPS outcome.

Complications

1. Pain during insertion of the needle

Cause: The needle is inserted into the sulcus too rapidly. To correct: Enter and move the needle very slowly into the sulcus while simultaneously initiating the ControlFlo of local anesthetic solution.

2. Inability to maintain high yellow or green LED zone on the STA System

Cause #1: Have not located the entrance to the intraligamentary tissue (PDL space). To correct: Relocate the needle.

Cause #2: Have not allowed adequate time (10 to 15 seconds) for back-pressure and analysis of DPS technology to occur. To correct: Position needle and allow 10 to 15 seconds for the ascending tones and sequential illumination of the LED lights.

3. Over-pressure announcement by the STA System:

Cause #1: Excessive hand pressure on the STA-Wand handpiece can jam the needle into the bone, resulting in obstruction of flow of the anesthetic solution at the needle tip. To correct: Restart the STA System and use gentler forward hand pressure when placing the needle into the sulcus.

Cause #2: Clogged needle tip from plaque or dental calculus. To correct: Stop, remove needle, and restart, verifying that local anesthetic solution is flowing from the tip of the needle before reentry into PDL tissues.

4. Postinjection pain or tissue necrosis

Cause #1: Excessive volume of anesthetic solution was used. To correct: Limit the volume of anesthetic solution.

Cause #2: Too many tissue penetrations with needle and/or excessive forward hand force placed on the needle, causing mechanical trauma to the tissues. To correct: Limit the number of needle entries to a given site, and use a moderate amount of forward hand pressure on the STA-Wand handpiece.

Suggested Drug/Volume

1. 2% Lidocaine HCl 1 : 100,000 epinephrine

a. Drug volume no greater than 0.9 mL ( cartridge) is suggested for a single-rooted tooth.

cartridge) is suggested for a single-rooted tooth.

b. Drug volume no greater than 1.8 mL (full cartridge) is suggested for a multirooted tooth.

a. Drug volume no greater than 0.45 mL ( cartridge) is suggested for a single-rooted tooth.

cartridge) is suggested for a single-rooted tooth.

b. Drug volume no greater than 0.9 mL ( cartridge) is suggested for a multirooted tooth.

cartridge) is suggested for a multirooted tooth.

2. 4% Articaine HCl 1 : 200,000 epinephrine

a. Drug volume no greater than 0.45 mL ( cartridge) is suggested for a single-rooted tooth.

cartridge) is suggested for a single-rooted tooth.

b. Drug volume no greater than 0.9 mL ( cartridge) is suggested for a multirooted tooth.

cartridge) is suggested for a multirooted tooth.

a. Drug volume no greater than 0.4 mL is suggested for a single-rooted tooth.

b. Drug volume no greater than 0.8 mL is suggested for a multirooted tooth.

Duration of Expected Anesthesia

The expected pulpal anesthesia duration is directly correlated with the volume of local anesthetic solution administered. The recommended dosages provide pulpal anesthesia ranging from 30 to 45 minutes. The PDL injection may be repeated if necessary to permit completion of the dental procedure.

Advantages and disadvantages of the Wand/STA System are presented in Box 15-1.

Intraseptal Injection

The intraseptal injection is similar in technique and design to the PDL injection. It is included for discussion because it is useful in providing osseous and soft tissue anesthesia and hemostasis for periodontal curettage and surgical flap procedures. In addition, it may be effective when the condition of periodontal tissues in the gingival sulcus precludes use of the PDL injection (e.g., infection, acute inflammation). Saadoun and Malamed have shown that the path of diffusion of the anesthetic solution is through medullary bone, as in the PDL injection.42

Nerves Anesthetized

Terminal nerve endings at the site of injection and in adjacent soft and hard tissues.

Indication

When both pain control and hemostasis are desired for soft tissue and osseous periodontal treatment.

Advantages

1. Lack of lip and tongue anesthesia (appreciated by most patients)

2. Minimum volumes of local anesthetic necessary

3. Minimized bleeding during the surgical procedure

5. Immediate (<30 second) onset of action

6. Few postoperative complications

7. Useful on periodontally involved teeth (avoids infected pockets)

Technique

1. A 27-gauge short needle is recommended.

2. Area of insertion: Center of the interdental papilla adjacent to the tooth to be treated (Fig. 15-8)

4. Landmarks: Papillary triangle, about 2 mm below the tip, equidistant from adjacent teeth

5. Orientation of the bevel: Not significant, although Saadoun and Malamed recommend toward the apex42

a. Assume the correct position, which varies significantly from tooth to tooth. The administrator should be comfortable, have adequate visibility of the injection site, and maintain control over the needle.

b. Position the patient supine or semisupine with the head turned to maximize access and visibility.

c. Prepare tissue at the site of penetration.

d. Stabilize the syringe and orient the needle correctly (Fig. 15-9).

(1) Frontal plane: 45 degrees to the long axis of the tooth

e. Slowly inject a few drops of local anesthetic as the needle enters soft tissue, and advance the needle until contact with bone is made.

f. While applying pressure to the syringe, push the needle slightly deeper (1 to 2 mm) into the interdental septum.

g. Deposit 0.2 to 0.4 mL of local anesthetic in not less than 20 seconds.

h. Two important items indicate success of the intraseptal injection:

(1) Significant resistance to the deposition of solution

(a) This is especially noticeable when a conventional syringe is used. Resistance is similar to that felt with nasopalatine and PDL injections.

(b) Anesthetic solution should not come back into the patient’s mouth. If this occurs, repeat the injection with the needle slightly deeper.

(2) Ischemia of soft tissues adjacent to the injection site (although noted with all local anesthetic solutions, this is more prominent with local anesthetics containing a vasoconstrictor)

i. Repeat the injection as needed during the surgical procedure.

Complication

Postinjection pain is unlikely to develop because the injection site is within the area of surgical treatment. Saadoun and Malamed demonstrated that postsurgical periodontal discomfort after the use of intraseptal anesthesia is no greater than after a regional nerve block.42

Duration of Expected Anesthesia

The duration of osseous and soft tissue anesthesia is variable after an intraseptal injection. Using an epinephrine concentration of 1 : 50,000, Saadoun and Malamed found pain control and hemostasis adequate for completion of the planned procedure without reinjection in most patients.42 However, some patients require a second intraseptal injection.

Intraosseous Injection

Deposition of local anesthetic solution into the interproximal bone between two teeth has been practiced in dentistry since the start of the twentieth century.23 Originally, IO anesthesia necessitated the use of a half-round bur to provide entry into interseptal bone that had been surgically exposed. Once the hole had been made, a needle would be inserted into this hole and local anesthetic deposited.

The PDL and intraseptal injections previously described are variations of IO anesthesia. With the PDL injection, local anesthetic enters interproximal bone through the periodontal tissues surrounding a tooth, whereas in intraseptal anesthesia, the needle is embedded into the interproximal bone without the use of a burr.

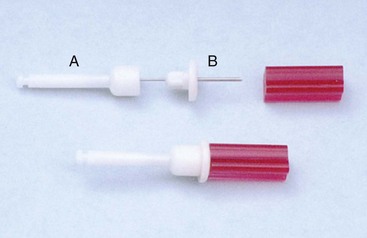

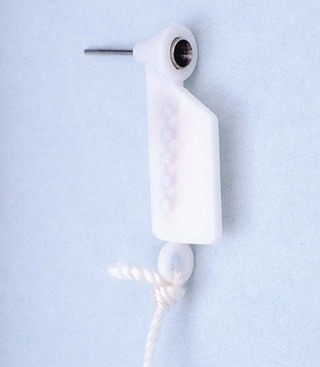

In recent years, the IO technique has been modified with the introduction of several devices* that simplify the procedure. The Stabident System was introduced, followed later by the X-Tip, and most recently by the IntraFlow. The Stabident System consists of two parts: a perforator—a burr that perforates the cortical plate of bone with a conventional slow-speed contra-angle handpiece—and an 8-mm long, 27-gauge needle that is inserted into this predrilled hole for anesthetic administration (Fig. 15-10).

Experience with the IO technique has shown that perforation of the interproximal bone is almost always entirely atraumatic. However, some persons initially had difficulty placing the needle of the local anesthetic syringe back into the previously drilled hole in the interproximal bone. Introduction of the X-Tip eliminated this problem. The X-Tip is composed of a drill and a guide sleeve (Fig. 15-11). The drill leads the guide sleeve through the cortical plate of bone, after which it is separated and withdrawn. The guide sleeve remains in the bone and easily accepts a 27-gauge short needle, which is recommended by the manufacturer for injection of local anesthetic into the cancellous bone. The Alternative Stabident System introduced shortly thereafter eliminated the problem of locating the “hole” by inserting a conical-shaped “guide sleeve” into the hole. The 27-gauge short needle could then be easily placed into the hole (Fig. 15-12).

Figure 15-12 Alternative Stabident System. Guide sleeve remains in hole in bone, permitting easy access for needle.

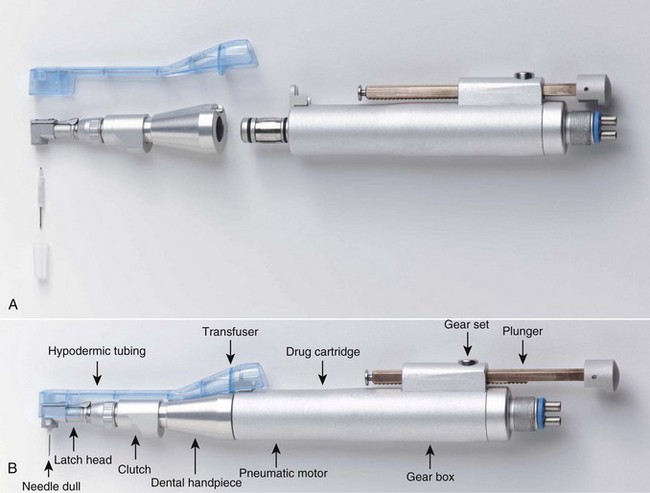

The IntraFlow HTP Anesthesia Delivery System, which was recently introduced, combines the two steps previously described into one (Fig. 15-13).3 The IntraFlow handpiece is attached to a standard four-hole air hose on a treatment room delivery unit and is controlled by a foot rheostat. The IntraFlow is a specially modified slow-speed handpiece that consists of four main parts:

Figure 15-13 Intraosseous anesthesia—IntraFlow HTP Anesthesia Delivery System. Components: A, Disassembled. B, Assembled.

1. A needle or drill that makes the perforation through the bone and delivers the local anesthetic

2. A transfuser that acts as a conduit from the local anesthetic cartridge to the needle or drill

3. A latch tip or clutch that drives and governs the rotation of the needle or drill

4. A motor or infusion drive that powers the rotation of the needle or drill and, while holding the local anesthetic cartridge in place, powers the infusion plunger. A 24-gauge dual-beveled needle is provided.

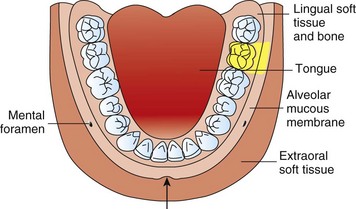

The IO injection technique can provide anesthesia of a single tooth or multiple teeth in a quadrant. To a significant degree, the area of anesthesia is dependent on both the site of injection and the volume of local anesthetic deposited. It is recommended that 0.45 to 0.6 mL of anesthetic be administered when treatment is to be confined to not more than one or two teeth. Greater volumes (up to 1.8 mL) may be administered when treatment of multiple teeth in one quadrant is contemplated. The IO injection may be used when six or eight mandibular anterior teeth (e.g., first premolar to first premolar bilaterally) are managed. Bilateral IO injections are necessary, the perforation being made between the canine and the first premolar on both sides. This provides pulpal anesthesia of eight teeth. It should be remembered, however, that the incisive nerve block provides pulpal anesthesia of these same teeth without the need for perforation of bone.

Because IO injections deposit local anesthetic into a vascular site, it is suggested that the volume of local anesthetic delivered be kept to the recommended minimum to avoid possible overdose.43 In addition, because of the high incidence of palpitations noted when vasopressor-containing local anesthetics are used, a “plain” local anesthetic is recommended in the IO injection. However, discussion with endodontists who use IO frequently indicates that the quality and depth of anesthesia are not as great when plain local anesthetics are used.

Nerves Anesthetized

Terminal nerve endings at the site of injection and in adjacent soft and hard tissues.

Disadvantages

1. Requires a special syringe (e.g., Stabident System, X-Tip, IntraFlow)

2. Bitter taste of the anesthetic drug (if leakage occurs)

3. Occasional (rare) difficulty in placing anesthetic needle into predrilled hole (primarily in mandibular second and third molar regions)

4. High occurrence of palpitations when vasopressor-containing local anesthetic is used

Technique*

1. Selection of site for injection

(1) At a point 2 mm apical to the intersection of lines drawn horizontally along the gingival margins of the teeth and a vertical line through the interdental papilla

(2) The site should be located distal to the tooth to be treated, if possible, although this technique provides anesthesia in most cases when injected anterior to the tooth being treated.

(3) Avoid injecting in the mental foramen area (increased risk of nerve damage).

a. Remove the X-Tip from its sterile vial.

b. Prepare soft tissues at perforation site:

(1) Prepare tissue at the injection site with 2 × 2 inch sterile gauze.

(2) Apply topical anesthetic to the injection site for minimum of 1 minute.

(3) Place bevel of needle against gingiva, injecting a small volume of local anesthetic until blanching occurs.

c. Perforation of the cortical plate

(1) While holding the perforator perpendicular to the cortical plate, gently push the perforator through the attached gingiva until its tip rests against bone (without activating the handpiece).

(2) Activate the handpiece, using a gentle “pecking” motion on the perforator until a sudden loss of resistance is felt. Cortical bone will be perforated within 2 seconds (Fig. 15-15).

(3) Hold the guide sleeve in place as the drill is withdrawn (Fig. 15-16). Withdraw the perforator and dispose of it safely (sharps container).

d. Injection into cancellous bone:

(1) It is easy to insert the needle into the hole when a short needle is used (Fig. 15-17).

(2) Press the tapered needle gently against the guide sleeve to minimize local anesthetic leakage.

e. X-Tip doses: Recommended dosages for the X-Tip are the same for each local anesthetic solution as is recommended for other injections.

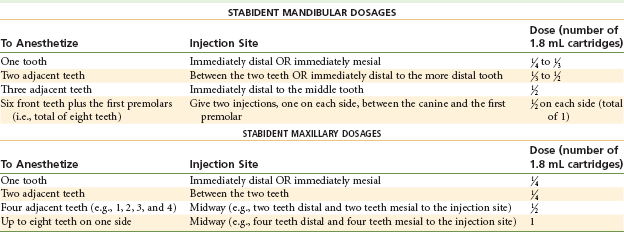

f. Stabident doses (Table 15-1)

g. Recommended technique for the IntraFlow IO syringe system is presented in Box 15-2.

Safety Feature

Intravascular injection is extremely unlikely, although the area injected into is quite vascular. Slow injection of the recommended volume of solution is important to keeping IO anesthesia safe.

Precautions

1. Do not inject into infected tissue.

3. Do not inject too much solution. (See recommended dosages in Table 15-1.)

4. Do not use a vasopressor-containing local anesthetic unless necessary, and then only 1 : 200,000 or 1 : 100,000. Try to avoid use of 1 : 50,000 epinephrine.

Complications

1. Palpitation: This reaction frequently occurs when a vasopressor-containing local anesthetic is used. To minimize its occurrence, use a “plain” local anesthetic, if possible, or the most dilute epinephrine concentration available (e.g., 1 : 200,000).

2. Postinjection pain is unlikely after IO anesthesia. The use of mild analgesics (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) is recommended if discomfort occurs in the postinjection period.

3. Fistula formation at the site of perforation has been reported on occasions. In most instances, this can be prevented by employing a gentle “pecking” motion with the handpiece as the perforator goes through the cortical plate of bone. Application of constant pressure against the bone presumably leads to the buildup of heat with possible bony necrosis and fistula formation.

4. Separation of the perforator or cannula: Rare, but reported. The metal shaft of the burr or cannula separates and remains in bone. Usually easy to remove with a hemostat

5. Perforation of lingual plate of bone (Fig. 15-18). Prevented by proper technique

Duration of Expected Anesthesia

Pulpal anesthesia of between 15 and 30 minutes can be expected. If a vasopressor-containing solution is used, the duration approaches 30 minutes. If a plain solution is used, a 15-minute duration is usual. The depth of anesthesia is greater with a vasopressor-containing local anesthetic.

Intrapulpal Injection

Obtaining profound anesthesia in the pulpally involved tooth was a significant problem before the rediscovery of IO anesthesia. Specifically the problem occurred with mandibular molars, because few alternative anesthetic techniques were available with which the doctor could obtain profound anesthesia. Maxillary teeth usually are anesthetized with a supraperiosteal injection or a nerve block such as the posterior superior alveolar (PSA), anterior superior alveolar (ASA), anterior middle superior alveolar (AMSA), or (rarely) maxillary (second division; V2) nerve block. Mandibular teeth anterior to the molars are anesthetized with the incisive nerve block. Anesthesia of mandibular molars, however, commonly is limited to nerve block anesthesia, which may prove to be ineffective in the presence of infection and inflammation. Methods of obtaining anesthesia for endodontics are described in Chapter 16.

Deposition of local anesthetic directly into the coronal portion of the pulp chamber of a pulpally involved tooth provides effective anesthesia for pulpal extirpation and instrumentation where other techniques have failed. The intrapulpal injection may be used on any tooth when difficulty in providing profound pain control exists, but from a practical view, it is necessary most commonly on mandibular molars.

The intrapulpal injection provides pain control through both the pharmacologic action of the local anesthetic and applied pressure. This technique may be used once the pulp chamber is exposed surgically or pathologically.

Nerves Anesthetized

Terminal nerve endings at the site of injection in the pulp chamber and canals of the involved tooth.

Indication

When pain control is necessary for pulpal extirpation or other endodontic treatment in the absence of adequate anesthesia from other techniques.

Contraindication

None. The intrapulpal injection may be the only local anesthetic technique available in some clinical situations.

Disadvantages

Alternatives

IO. However, when IO fails, intrapulpal injection may be the only viable alternative to provide clinically adequate pain control.

Technique

1. Insert a 25- or 27-gauge short or long needle into the pulp chamber or the root canal as needed (Fig. 15-19).

Figure 15-19 For the intrapulpal injection, a 25-gauge 1 or  inch needle is inserted into the pulp chamber or a specific root canal. Bending the needle may be necessary to gain access. (From Cohen S, Burns RC: Pathways of the pulp, ed 8, St Louis, 2001, Mosby.)

inch needle is inserted into the pulp chamber or a specific root canal. Bending the needle may be necessary to gain access. (From Cohen S, Burns RC: Pathways of the pulp, ed 8, St Louis, 2001, Mosby.)

2. Ideally, wedge the needle firmly into the pulp chamber or root canal.

a. Occasionally, the needle does not fit snugly into the canal. In this situation, the anesthetic can be deposited in the chamber or canal. Anesthesia in this case is produced only by the pharmacologic action of the local; there is no pressure anesthesia.

3. Deposit anesthetic solution under pressure.

a. A small volume of anesthetic (0.2 to 0.3 mL) is necessary for successful intrapulpal anesthesia, if the anesthetic stays within the tooth. In many situations, the anesthetic simply flows back out of the tooth into the aspirator (vacuum) tip.

4. Resistance to injection of the drug should be felt.

5. Bend the needle, if necessary, to gain access to the pulp chamber (Fig. 15-20).

Figure 15-20 The needle may have to be bent to gain access to a canal. (Modified from Cohen S, Burns RC: Pathways of the pulp, ed 8, St Louis, 2001, Mosby.)

a. Although there is a greater risk of breakage with a bent needle, this is not a problem during intrapulpal anesthesia, because the needle is inserted into the tooth itself, not into soft tissues. Retrieval is relatively simple if the needle breaks.

6. When the intrapulpal injection is performed properly, a brief period of sensitivity (ranging from mild to very painful) usually accompanies the injection. Pain relief usually occurs immediately thereafter, permitting instrumentation to proceed atraumatically.

7. Instrumentation may begin approximately 30 seconds after the injection is given.

Failures of Anesthesia

1. Infected or inflamed tissues. Changes in tissue pH minimize the effectiveness of the anesthetic. However, intrapulpal anesthesia invariably works to provide effective pain control.

2. Solution not retained in tissue. To correct: Try to advance the needle farther into the pulp chamber or root canal, and readminister 0.2 to 0.3 mL of anesthetic drug.

Complication

Discomfort during the injection of anesthetic. The patient may experience a brief period of intense discomfort as the injection of the anesthetic drug is started. Within a second (literally), the tissue is anesthetized and the discomfort ceases. The use of inhalation sedation (nitrous oxide or oxygen) can help to minimize or alter the feeling experienced.

Mandibular Infiltration in Adults

Providing effective pain control is one of the most important aspects of dental care. Indeed, patients rate a dentist “who does not hurt” and one who can “give painless injections” as meeting the second and first most important criteria used in evaluating dentists.44 Unfortunately, the ability to attain consistently profound anesthesia for dental procedures in the mandible of adult patients has proved extremely elusive. This is even more of a problem when infected teeth are involved, primarily mandibular molars. Anesthesia of maxillary teeth on the other hand, although on occasion difficult to achieve, is rarely an insurmountable problem. Reasons for this, as discussed in Chapter 12, include the fact that the cortical plate of bone overlying the maxillary teeth is normally thin, thus allowing the local anesthetic drug to diffuse when administered by supraperiosteal injection (infiltration). Additionally, relatively simple nerve blocks, such as the PSA, MSA, ASA (infraorbital), and AMSA, are available as alternatives to infiltration. Maxillary anesthesia technique was discussed in Chapter 13.

It is commonly stated that the significantly higher failure rate for mandibular anesthesia is related to the thickness of the cortical plate of bone in the adult mandible. Indeed it is generally acknowledged that mandibular infiltration is successful where the patient has a full primary dentition (see discussion of pediatric local anesthesia in Chapter 16).45,46 Once a mixed dentition develops, it is a general rule of teaching that the mandibular cortical plate of bone has thickened to the degree that infiltration might not be effective, leading to the recommendation that “mandibular block” techniques should now be employed.47

A second difficulty with the traditional Halsted approach to the inferior alveolar nerve (e.g., IANB, “mandibular block”) is the absence of consistent landmarks. Multiple authors have described numerous approaches to this oftentimes elusive nerve.48-50 Reported failure rates for the IANB are commonly high, ranging from 31% and 41% in mandibular second and first molars to 42%, 38%, and 46% in second and first premolars and canines, respectively,51 and 81% in lateral incisors.52

Not only is the inferior alveolar nerve elusive, studies using ultrasound53 and radiography54,55 to accurately locate the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle or the mandibular foramen revealed that accurate needle location did not guarantee successful pain control.56 The central core theory best explains this problem.57,58 Nerves on the outside of the nerve bundle supply the molar teeth, while nerves on the inside (core fibers) supply the incisor teeth. Therefore the local anesthetic solution deposited near the IAN may diffuse and block the outermost fibers but not those located more centrally, leading to incomplete mandibular anesthesia.

This difficulty in achieving mandibular anesthesia has led to the development of alternative techniques to the traditional (Halsted approach) inferior alveolar nerve block. These have included the Gow-Gates mandibular nerve block, the Akinosi-Vazirani closed-mouth nerve block, the periodontal ligament (PDL, intraligamentary) injection, intraosseous anesthesia, and, most recently, buffered local anesthetics.59 Although all maintain some advantages over the traditional Halsted approach, none is without its own faults and contraindications.

The ability to provide localized areas of anesthesia by infiltration injection without the need for nerve block injections has a number of benefits. Meechan60 has enumerated them as follows: (1) technically simple, (2) more comfortable for patients, (3) can provide hemostasis when needed, (4) in many cases obviate the presence of collateral innervation, (5) avoid the risk of potential damage to nerve trunks, (6) lesser risk of intravascular injection, (7) safer in patients with clotting disorders, (8) reduce risk of needle-stick injury, and (9) preinjection application of topical anesthetic masks needle penetration discomfort.

Attempts at mandibular infiltration in adult patients have been made in the past. In a 1976 study of 331 subjects receiving IANB with lidocaine HCl 2% with epinephrine 1 : 80,000, 23.7% had unsuccessful anesthesia.61 Supplemental infiltration of 1.0 mL of the same drug on the buccal aspect of the mandible proved successful in 70 of the 79 failures. Of the remaining 9, 7 were successfully anesthetized following additional infiltration of 1.0 mL on the lingual aspect of the mandible.

Yonchak and colleagues investigated infiltration on incisors, reporting 45% success following labial infiltration (lidocaine 2% with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine) and 50% success with lingual infiltrations of the same solution for lateral incisors, and 63% and 47% for central incisors on labial and lingual infiltration.62

Meechan and Ledvinka found similar success rates (50%) on central incisor teeth following labial or lingual infiltration of 1.0 mL of lidocaine 2% with 1 : 80,000 epinephrine.63

In 1990, Haas and coworkers compared mandibular buccal infiltrations for canines with prilocaine HCl versus articaine HCl and found no significant differences.64 Success rates were 50% for prilocaine and 65% for articaine (both 4% with epinephrine 1 : 200,000). A second study noted a 63% success rate on mandibular second molars with articaine and 53% with prilocaine (both 4% with epinephrine 1 : 200,000).65

Since the introduction of articaine HCl 4% with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 into the U.S. dental market in June 2000, numerous anecdotal reports have been received from doctors who claimed that they no longer needed to administer the IANB to work painlessly in the adult mandible. They claimed that mandibular infiltration with articaine HCl was uniformly successful. These claims were initially met with skepticism. In the past 5 years, four well-designed clinical trials have been reported comparing infiltration in the adult mandible of articaine HCl 4% with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 versus lidocaine 2% with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 or 1 : 80,000.7,8,52,66

Following is a summary of these papers.

Kanaa MD, Whitworth JM, Corbett IP, Meechan JG: Articaine and lidocaine mandibular buccal infiltration anesthesia: a prospective randomized double-blind cross-over study, J Endod 32 : 296–298, 20068

Design

Infiltrations were administered to 31 subjects in the buccal fold adjacent to the mandibular first molar. A dose of 1.8 mL was administered at a rate of 0.9 mL per 15 seconds. The order of drug administration was randomized, with the second injection administered at least 1 week after the first. The same investigator administered all injections. Electrical pulp testing (EPT) was used to determine pulpal sensitivity. Baseline readings were obtained, and EPT was repeated once every 2 minutes after injection for 30 minutes. If no response (to maximal EPT stimulation of 80 µA) occurred, the number of episodes of no response at maximal stimulation was recorded. The criterion for successful anesthesia was no volunteer response to maximal stimulation on two or more consecutive episodes of testing. (This had been established as the criterion for success in many previous clinical trials.)

Results

The total number of episodes of no sensation on maximal stimulation in first molars over the period of the trial (32 minutes) was greater for articaine (236 episodes) than for lidocaine (129) (P < .001). Twenty (64.5%) subjects experienced anesthetic success following articaine, whereas 12 (38.7%) did so with lidocaine (P < .08). The design of the trial allowed for a maximal possible duration of anesthesia of 28 minutes. Six subjects receiving articaine achieved 28 minutes of anesthesia compared with two for lidocaine.

Discussion

The difference between articaine and lidocaine was most obvious toward the end of the study period. The percentage of patients showing no response at maximal stimulation was reduced at all reference points after 22 minutes with lidocaine. With articaine, however, the greatest percentage of nonresponders was noted at the end of the trial (32 minutes).

Conclusion

It was noted that 4% articaine with epinephrine was more effective than 2% lidocaine with epinephrine in producing pulpal anesthesia in lower molars following buccal infiltration.

Robertson D, Nusstein J, Reader A, Beck M, McCartney M: The anesthetic efficacy of articaine in buccal infiltration of mandibular posterior teeth, J Am Dent Assoc 138:1104–1112, 2007.7

Design

Sixty blinded subjects randomly received buccal infiltration injections of 1.8 mL of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 and 4% articaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 at two separate appointments at least 1 week apart. Each subject served as his or her own control. Sixty infiltrations were administered on the right side and 60 on the left side. For the second infiltration in each subject, the investigator used the same side randomly chosen for the first infiltration. The teeth chosen for evaluation were the first and second molars and the first and second premolars. The same investigator administered all injections. Before injections were administered, baseline values were determined on the experimental teeth with EPT. A single infiltration was administered buccal to the first mandibular molar, bisecting the approximate location of the mesial and distal roots. The 1.8 mL was deposited over a period of 1 minute. One minute after injection, the first and second molars were pulp tested. At 2 minutes, the premolars were tested. At 3 minutes, the control canine (contralateral side) was tested. This testing cycle was repeated every 3 minutes for 60 minutes. Complete absence of sensation to maximal EPT stimulation on two or more consecutive readings was the criterion for successful anesthesia. Onset of anesthesia was defined as the time at which the first of two consecutive no responses to EPT of 80 occurred.

Results

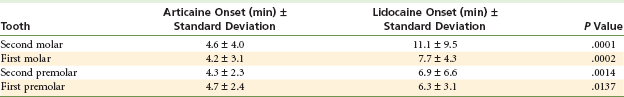

Articaine was significantly better than lidocaine in achieving pulpal anesthesia in each of the four teeth (P < .0001 for all four teeth). Table 15-2 summarizes these findings.

TABLE 15-2

Summary of Articaine vs. Lidocaine Success

| Tooth | Articaine % Success | Lidocaine % Success |

| Second molar | 75 | 45 |

| First molar | 87 | 57 |

| Second premolar | 92 | 67 |

| First premolar | 86 | 61 |

The onset of successful anesthesia was significantly faster for articaine than for lidocaine for all four teeth tested (Table 15-3).

Discussion

The exact mechanism of the increased efficacy of articaine is not known. One theory relates to the 4% concentration of articaine versus the 2% lidocaine solution. However, Potocnik and associates found that 4% and 2% articaine were superior to 2% lidocaine in blocking nerve conduction.67 A second theory is that the thiophene ring of articaine enables it to diffuse more effectively than the benzene ring found in other local anesthetics.

Regarding onset of anesthesia, previous studies with onset of lidocaine following IANB found onset times ranging from 8 to 11 minutes for the first molar and from 8 to 12 minutes for the first premolar.68-73 Articaine provided a more rapid onset of pulpal anesthesia for all tested teeth than was provided by IANB. However, pulpal anesthesia declined steadily over the 60 minute test period. Therefore, if profound pulpal anesthesia is required for 60 minutes, buccal infiltration of 4% articaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 will not provide the duration needed because of declining pulpal anesthesia.

Conclusion

Buccal infiltration of the first mandibular molar with 1.8 mL of 4% articaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 is significantly better than similar infiltration of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 in achieving pulpal anesthesia in mandibular posterior teeth. Clinicians should keep in mind that pulpal anesthesia will likely decline slowly over 60 minutes.

Haase A, Reader A, Nusstein J, Beck M, Drum M: Comparing anesthetic efficacy of articaine versus lidocaine as a supplemental buccal infiltration of the mandibular first molar after an inferior alveolar nerve block, J Am Dent Assoc 139:1228–1235, 2008.66

Design

Seventy-three subjects participated in a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, crossover study comparing the degree of pulpal anesthesia achieved by means of a mandibular buccal infiltration of two anesthetic solutions: 4% articaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000, and 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000, following an IANB with 4% articaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000. The subject served as his/her own control. The side chosen for the first infiltration was used again for the second infiltration. Injections were administered at least 1 week apart. The same investigator administered all injections. An EPT was used to test the first molar for anesthesia in 3 minute cycles for 60 minutes. The IANB was administered over 60 seconds. Fifteen minutes after completion of the IANB, the infiltration was administered buccal to the first mandibular molar, bisecting the approximate location of the mesial and distal roots. The 1.8 mL was deposited over a period of 1 minute. Sixteen minutes after completion of the IANB (1 minute following the infiltration), EPT testing of the first molar was performed. At 3 minutes, the contralateral canine was tested. This cycle was repeated every 3 minutes for 60 minutes. Anesthesia was considered successful when two consecutive EPT readings of 80 were obtained within 10 minutes of the IANB and infiltration injection, and the 80 reading was maintained continuously through the 60th minute.

Results

The articaine formulation was significantly better than the lidocaine formulation with regard to anesthetic success: 88% versus 71% for lidocaine (P < .01), with anesthesia developing within 10 minutes after IANB and buccal infiltration, sustaining the 80 reading on the EPT continuously for the 60 minute testing period.

Discussion

Anesthetic success was significantly better with the 4% articaine formulation than the 2% lidocaine formulation. Both anesthetic formulations demonstrated a gradual increase in pulpal anesthesia. This is likely a result of the effect of the infiltrations’ overcoming failure or the slow onset of anesthesia following IANB. Therefore, for a maximum effect with 4% articaine infiltration, a waiting time is required before onset of pulpal anesthesia is achieved. It may be prudent to wait for signs of lip numbness before administering the infiltration. Without an effective IANB, buccal infiltration of articaine alone has a relatively short duration (see previous two citations). A fairly high percentage of patients receiving the articaine infiltration maintained pulpal anesthesia through the 50th minute. Articaine infiltration demonstrated a decline in the incidence of pulpal anesthesia after the 52nd minute. Because most dental procedures require less than 50 minutes for completion, this injection protocol should prove successful for most dental treatments. The 2% lidocaine demonstrated a decline after the 60th minute.

Conclusion

Buccal infiltration of the first molar with a cartridge of 4% articaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 resulted in a significantly higher success rate (88%) than was attained with buccal infiltration of a cartridge of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 (71%) after an IANB with 4% articaine with epinephrine 1 : 100,000.

Kanaa MD, Whitworth JM, Corbett IP, Meechan JG: Articaine buccal infiltration enhances the effectiveness of lidocaine inferior alveolar nerve block, Int Endod J 42:238–246, 2009.52

Design

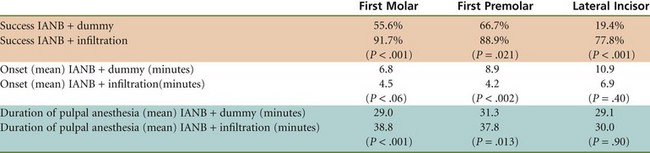

The goal of this study was to compare mandibular tooth anesthesia following lidocaine IANB with and without supplementary articaine buccal infiltration. In this prospective randomized, double-blind, crossover study, 36 subjects received two IANB injections with 2.2 mL lidocaine 2% with epinephrine 1 : 80,000 over two visits. At one visit, an infiltration of 2.2 mL of articaine 4% with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 was administered in the mucobuccal fold opposite the mandibular first molar. At the other visit, a dummy injection was performed. At least 1 week separated the two visits. Pulpal anesthesia of first molar, first premolar, and lateral incisor teeth was assessed with an EPT every 2 minutes for the first 10 minutes, and then at 5 minute intervals for 45 minutes post injection. Successful anesthesia was defined as the absence of sensation on two or more consecutive maximal EPT stimulations. The number of episodes of no response to maximal EPT stimulation was also recorded. Onset of pulpal anesthesia was considered the first episode of no response to maximal stimulation (two consecutive readings), whereas duration of anesthesia was taken as the time from the first of at least two consecutive maximal readings with no response until the onset of more than two responses at less than maximal stimulation or the end of the 45 minute test period, whichever was sooner.

Results

IANB with supplemental articaine infiltration produced greater success than IANB alone in first molars (33 vs. 20 subjects, respectively; P < .001), premolars (32 vs. 24; P = .021), and lateral incisors (28 vs. 7; P < .001). Additionally, IANB with articaine supplemental infiltration produced significantly more episodes of no response than IANB alone for first molars (339 vs. 162 cases, respectively; P < .001), premolars (333 vs. 197; P < .001), and lateral incisors (227 vs. 63; P < .001) (Table 15-4).

Discussion

Onset of pulpal anesthesia: In this study, the anesthetic effect for mandibular first molars peaked 25 minutes post injection with the dummy injection versus 6 minutes following articaine infiltration. For first premolars, peak anesthetic effect occurred at 30 minutes post injection versus 8 minutes following articaine infiltration, and for lateral incisors, peak anesthetic effect occurred at 40 minutes post injection versus 20 minutes following articaine infiltration in the first molar region.

Duration of Pulpal Anesthesia

The maximum duration of anesthesia possible in this trial was 43 minutes. The duration of pulpal anesthesia was significantly longer for first molars and first premolars but not for lateral incisors (see previous chart).

Conclusions

IANB injection supplemented with articaine by buccal infiltration was more successful than IANB alone for pulpal anesthesia in mandibular teeth. Articaine infiltration increased the duration of pulpal anesthesia in premolar and molar teeth when given in combination with a lidocaine IANB and produced a more rapid onset for premolars.

These four clinical trials clearly demonstrate that articaine given by mandibular buccal infiltration in the mucobuccal fold by the first mandibular molar can provide more successful anesthesia of longer duration to mandibular teeth when administered alone or as a supplement to IANB.

One thing to consider is that in each of these trials, buccal infiltration of articaine was administered adjacent to the first mandibular molar. These trials demonstrated the effectiveness of articaine in improving pulpal anesthesia success rates in molars and premolars. However, success rates and duration of anesthesia were not improved as significantly in lateral incisors—teeth at a distance from the site of local anesthetic deposition.

Meechan JG, Ledvinka JI: Pulpal anaesthesia for mandibular central incisor teeth: a comparison of infiltration and intraligamentary injections, Int Endod J 35:629–634, 2002.63

In 2002, Meechan and Ledvinka studied the effect of infiltrating 1.0 mL of 2% lidocaine with 1 : 80,000 epinephrine buccally or lingually to the mandibular central incisor.63

A success rate of 50% was achieved with the buccal or lingual injection site. However, when the injection dose was split (0.5 mL per site) between buccal AND lingual, the success rate increased to a statistically significant 92%.