Splints Acting on the Wrist

1 Discuss diagnostic indications for wrist immobilization splints.

2 Identify reasons to serial splint with a wrist immobilization splint.

3 Identify major features of wrist immobilization splints.

4 Understand the fabrication process for a volar or dorsal wrist splint.

5 Relate hints for a proper fit to a wrist immobilization splint.

6 Review precautions for wrist immobilization splinting.

7 Use clinical reasoning to evaluate a problematic wrist immobilization splint.

8 Use clinical reasoning to evaluate a fabricated wrist immobilization splint.

9 Apply knowledge about the application of wrist immobilization splints to a case study.

10 Understand the importance of evidenced-based practice with wrist splint provision.

11 Describe the appropriate use of prefabricated wrist splints.

Maintaining the wrist in proper alignment is important because the wrist is key to the health and balance of the entire hand. During functional activities, the wrist is positioned in extension for grasp and prehension. Therefore, the wrist extension immobilization type O splint [American Society of Hand Therapists 1992] or the wrist cock-up splint is the most common splint used in clinical practice. Wrist immobilization splints usually maintain the wrist in either a neutral or a mildly extended position, depending on the protocol for a particular diagnostic condition and the person’s treatment goals. A wrist immobilization splint immobilizes the wrist while allowing full metacarpophalangeal (MCP) flexion and thumb mobility. Thus, the person can continue to perform functional activities with the added support and proper positioning of the wrist the splint provides. Positioning the wrist in a splint in 0 to 30 degrees of wrist extension promotes functional hand patterns for completing functional activities [Palmer et al. 1985, Melvin 1989].

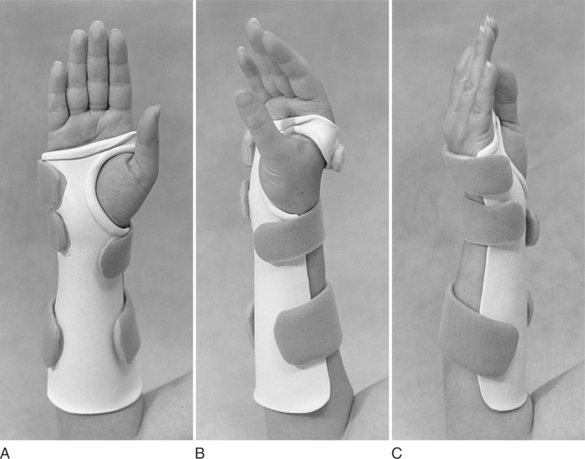

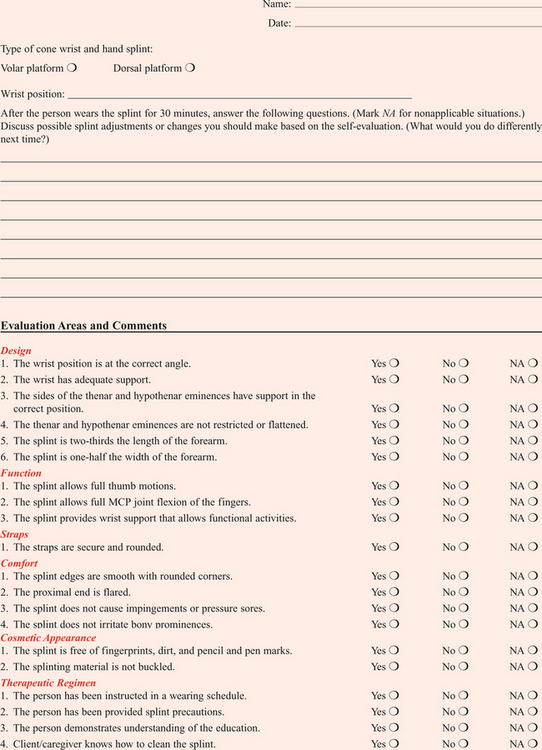

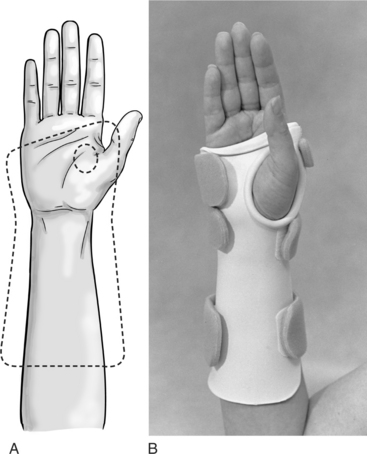

Therapists fabricate wrist immobilization splints to provide volar, dorsal, ulnar, circumferential forearm, wrist, hand, and (infrequently) radial support (see Figures 7-1 through 7-4). Therapists can also use wrist immobilization splints as bases for mobilization and static progressive splinting (see Chapter 11). Although some wrist immobilization splints are commercially available, they cannot provide the exact fit of custom-made splints. However, commercially available splints made from soft material may be more comfortable in certain situations, especially in a work or sports setting. Commercially available splints are not as restrictive and allow more functional hand use [Stern et al. 1994]. Some people with rheumatoid arthritis may also prefer the comfort of a soft wrist splint due to its ability to reduce pain and provide stability during functional activities [Nordenskiold 1990, Stern et al. 1997, Biese 2002].

This chapter primarily overviews wrist immobilization splints according to type, features, and diagnoses. The chapter also explores technical tips, trouble shooting, the use of prefabricated splints, the impact on occupations, and the application of a wrist mobilization and serial static approach.

Volar, Dorsal, Ulnar, and Circumferential Wrist Immobilization Splints

In clinical practice the therapist must decide whether to fabricate a volar, dorsal, ulnar, or circumferential wrist immobilization splint. Each has advantages and disadvantages [Colditz 2002].

Volar

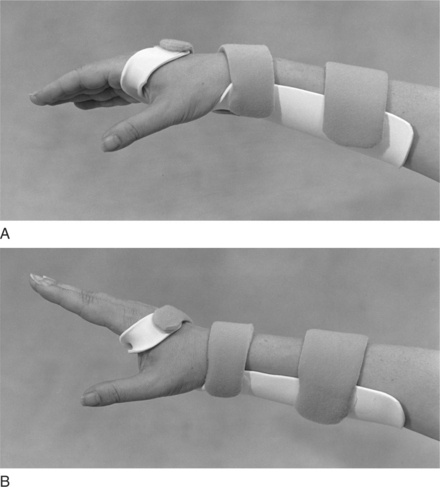

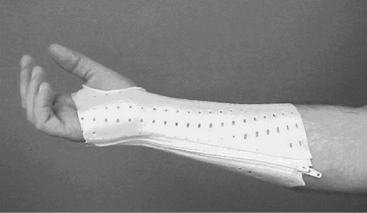

The volar wrist immobilization splint (Figure 7-1) depends on a dorsal wrist strap to hold the wrist in extension in the splint. An appropriate design furnishes adequate support for the weight of the wrist and hand. In cases in which the weight of the hand (flaccidity) must be held by the splint or in which the person is pulling against it (spasticity), the strap is not adequate to hold the wrist in the splint. However, a well-designed volar wrist splint with a properly placed wide wrist strap will support a flaccid wrist [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 6, 2006]. The volar design is best suited for circumstances that require rest or immobilization of the wrist when the person still has muscle control of the wrist [Colditz 2002].

In one study [Stern 1991], the volar wrist splint allowed the hand the best dexterity of custom-made wrist splints. A volar wrist splint’s greatest disadvantage is interference with tactile sensibility on the palmar surface of the hand and the loss of the hand’s ability to conform around objects [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 6, 2006]. In the presence of edema, one must use this design carefully because the dorsal strap can impede lymphatic and venous flow [Colditz 2002]. To address the presence of edema, a strap adaptation can be made by fabricating a continuous strap. The therapist applies self-adhesive Velcro hooks along the radial and ulnar borders of the splint, which are attached by a flexible fabric to create a soft dorsal shell.

Dorsal

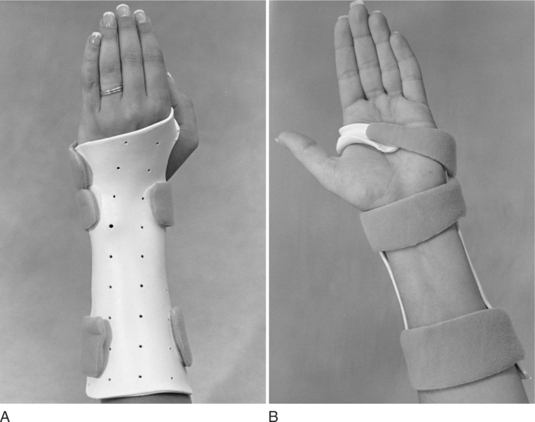

Some therapists fabricate dorsal splints with a large palmar bar that supports the entire hand. This large palmar bar tends to distribute pressure well and is necessary for the comfort and function of the splint. However, a large palmar bar does not free up the palmar surface as much for sensory input as a dorsal splint fabricated with a thinner palmar bar (Figure 7-2). Dorsal wrist splints designed with a standard strap configuration can be better tolerated by persons who have edematous hands because of the pressure distribution. Either the volar or the dorsal design may be used as a base for mobilization (dynamic) splinting. However, these designs can sometimes lead to splint migration and suboptimal splint performance.

Ulnar

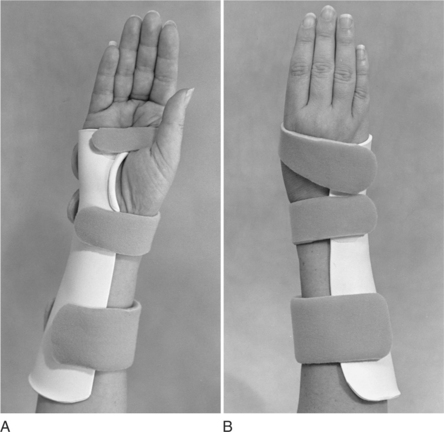

The ulnar wrist splint is easy to don and doff and can be applied if the person warrants more protection on the ulnar side of the hand, such as with sports injuries (Figure 7-3). This splint design is sometimes used for a person who has carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) or for ulnar wrist pain [LaStayo 2002]. It can also be used as a base for mobilization splinting.

Circumferential

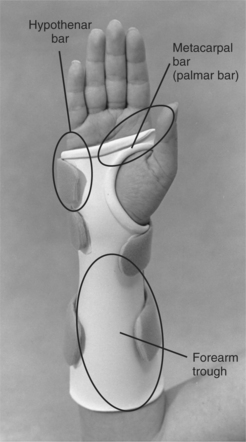

A circumferential splint is helpful in preventing migration, especially when used as a base for mobilization splints. It also provides good forearm support, controls edema, provides good pressure distribution, and avoids edge pressure [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 1999]. Some people may feel more confined in a circumferential splint. When fabricating a circumferential splint, the therapist is conscious of a possible pressure area over the distal ulna and checks that the fingers and thumb have full motion [Laseter 2002] (Figure 7-4). One among many circumferential splint options is a “zipper” splint made out of perforated thermoplastic material (Figure 7-5).

Figure 7-5 A “zipper” splint option for circumferential splinting (Sammons Preston & Rolyan). [From Bednar JM, Von Lersner-Benson C (2002). Wrist reconstruction: Salvage procedures. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Shirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 1200.]

Features of the Wrist Immobilization Splint

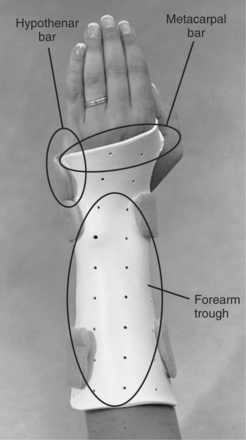

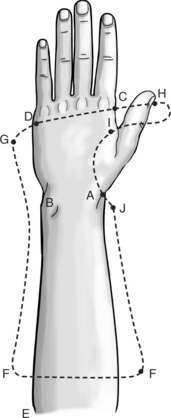

Understanding the features of a wrist immobilization splint helps therapists splint appropriately. Whether fabricating a volar, dorsal, ulnar, or circumferential wrist splint, the therapist must be aware of certain features of the various components of the wrist immobilization splint—such as a forearm trough, metacarpal bar, and hypothenar bar [Fess et al. 2005] (Figures 7-6 and 7-7). With a volar or dorsal immobilization splint the forearm trough should be two-thirds the length of the forearm and one-half the circumference of the forearm to allow for appropriate pressure distribution. It is sometimes necessary to notch the area near the distal ulna on the forearm trough to avoid a pressure point.

The hypothenar bar helps to place the hand in a neutral resting position by preventing extreme ulnar deviation. The hypothenar bar should not inhibit MCP flexion of the ring and little fingers. The metacarpal (MP) bar supports the transverse metacarpal arch. When supporting the palmar surface of the hand, the MP bar is sometimes called a palmar bar. With a volar wrist immobilization splint, the therapist positions this bar proximal to the distal palmar crease and distal and ulnar to the thenar crease to ensure full MCP flexion. On the ulnar side of the hand, it is especially important that the MP bar be positioned proximal from the distal palmar crease to allow full little finger MP flexion.

On the radial side, it is important to note the position of the MP bar below the distal palmar crease and distal to the thenar crease to allow adequate index and middle MCP flexion and thumb motions. On a dorsal wrist immobilization splint, the therapist positions this bar slightly proximal to the MCP heads on the dorsal surface of the hand when it winds around to the palmar surface. The same principles apply when positioning the MP bar on the volar surface of the hand (proximal to the distal palmar crease, and distal and ulnar to the thenar crease).

The splintmaker should also carefully consider the application of straps to the wrist splint. The therapist applies straps at the level of the MP bar, exactly at the wrist level, and at the proximal end of the splint. The straps attach to the splint with pieces of self-adhesive Velcro hook. The therapist should note that the larger the piece of self-adhesive hook Velcro, the larger the interface between it and the splint thermoplastic material. This larger interface helps ensure that it will remain in place and not peel off. With the identification of the potential for pressure or shear problems, the therapist applies padding to the splint (see Figures 7-1, 7-6, 7-14, 7-15, 7-16).

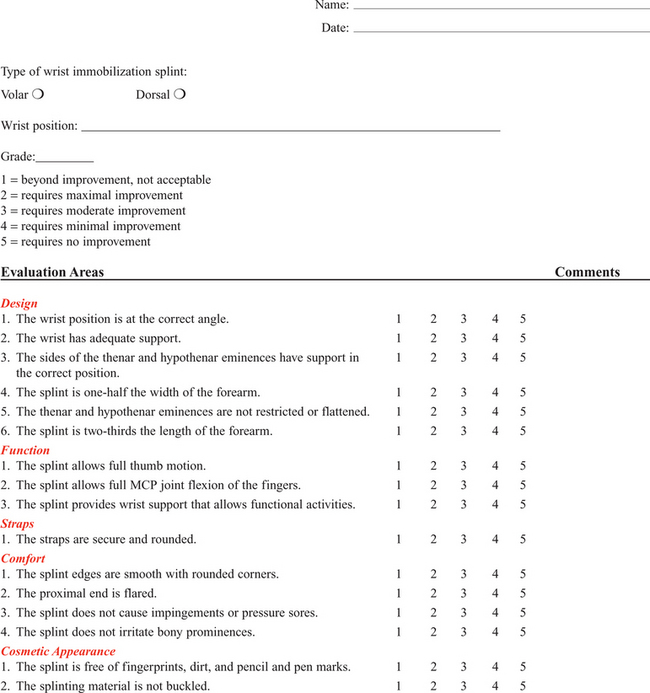

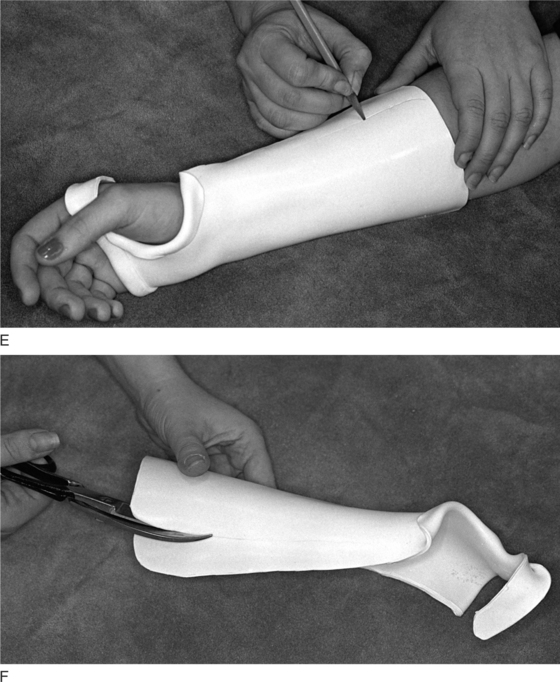

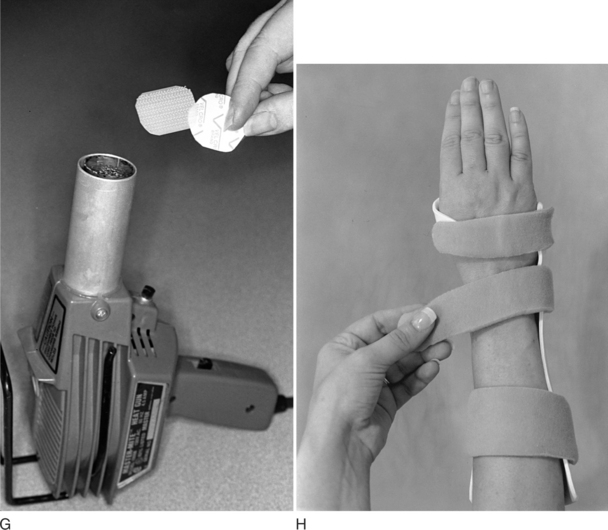

Figure 7-14 (A) Placing of the wrist immobilization pattern on the person. (B) Before forming the splint, the therapist should measure the person’s wrist with a goniometer to obtain the correct amount of extension. (C) A position for molding the wrist immobilization splint. (D) Flaring of the distal end of the splint on a flat surface. (E) Marking of the splint to make an adjustment. (F) Cutting off excess thermoplastic material to make an adjustment. (G) Heating of the Velcro tabs with a heat gun to help them adhere to the splint. (H) The therapist should place two straps on the forearm trough with one at the wrist level and one strap on the dorsal surface of the hand that connects the metacarpal bar to the hypothenar bar.

Diagnostic Indications

The clinical indications for the wrist immobilization splint vary according to the diagnosis. The therapist can apply the wrist immobilization splint for any upper extremity condition that requires the wrist to be in a static position. Application of this splint can work for a variety of goals, depending on the client’s treatment needs. These goals include decreasing wrist pain or inflammation, providing support, enhancing digital function, preventing wrist deformity, minimizing pressure on the median nerve, and minimizing tension on involved structures.

In some cases a wrist mobilization splint serial static approach is used to increase passive range of motion. Specific diagnostic conditions that may require a wrist immobilization splint can include, but are not limited to, tendonitis, distal radius or ulna fracture, wrist sprain, radial nerve palsy, carpal ganglion, stable wrist fracture, wrist arthroplasty, complex regional pain syndrome I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy), and nerve compression at the wrist.

The specific wrist positioning depends on the diagnostic protocol, physician referral, and person’s treatment goals. When the goal is functional hand use during splint wear, the therapist must avoid extreme wrist flexion or extension because either position disrupts the normal functional position of the hand. These positions can contribute to the development of CTS [Gelberman et al. 1981, Fess et al. 2005]. An exception to this rule is when the splint goal is to increase passive range of motion (PROM). In that case, an extreme position may be indicated. However, extreme positions may preclude function. The therapist must judge whether the trade-off is worth the loss of function [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 1999].

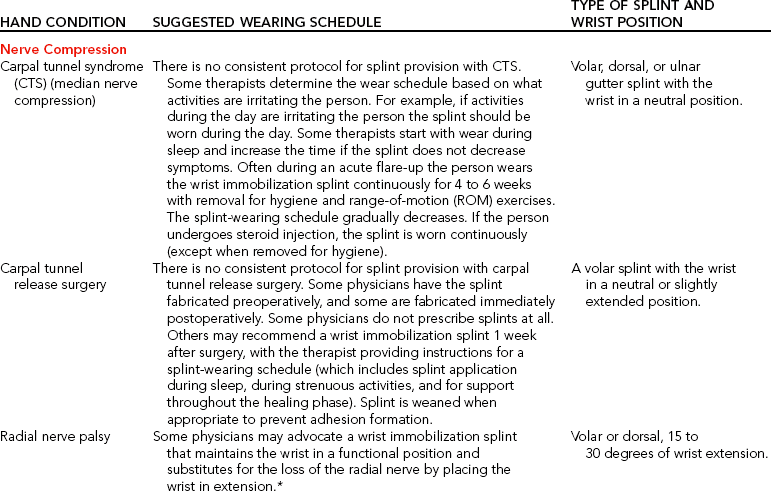

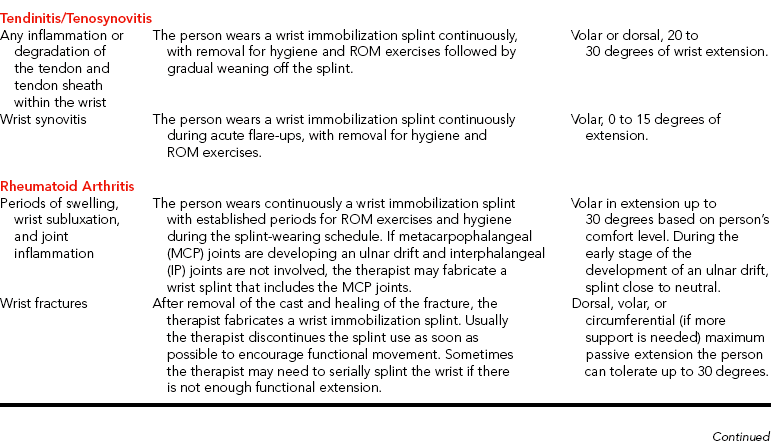

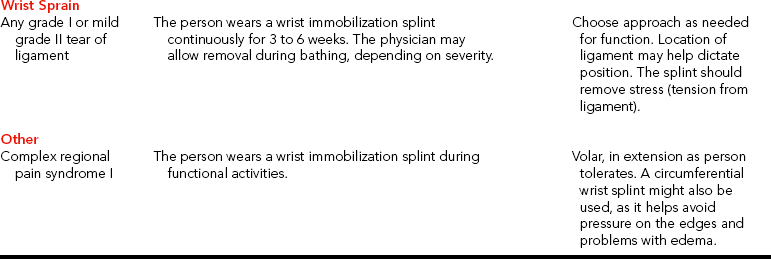

The therapist performs a thorough hand evaluation before fitting a person with a wrist immobilization splint and provides the person with a wearing schedule, instructions about splint maintenance and precautions, and an exercise program based on particular needs. Physicians and experienced therapists may have detailed guidelines for positioning and wearing schedules. Every hand is slightly different, and thus splint positioning and wearing protocols vary.Table 7-1 lists suggested wearing schedules and positioning protocols of common hand conditions that may require wrist immobilization splints.

Table 7-1

Conditions That May Require a Wrist Immobilization Splint

*The diagnosis may require additional types of splinting.

Wrist Splinting for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

For CTS, splinting the wrist as close as possible to 0 degrees (neutral) helps avoid added pressure on the median nerve [Gelberman et al. 1981, Weiss et al. 1995, Kulick 1996]. One study using sonography to determine the best wrist position for splinting CTS found that the majority of subjects benefited from a neutral position. However, a few subjects improved from splinting in either a wrist position of 15 degrees extension or 15 degrees flexion [Kuo et al. 2001]. This suggests better front-end diagnostic procedures to determine the most accurate splinting position.

One must be careful when applying prefabricated wrist immobilization splints for CTS because some splints place the wrist in a functional position of 20 to 30 degrees of extension [Weiss et al. 1995, Osterman et al. 2002]. Therefore, if it is possible to adjust the wrist angle of the splint it should be modified to a neutral position. Some of the prefabricated splints have a compartment in which a metal or thermoplastic insert is placed, and the insert allows adjustments for wrist position. However, prefabricated splints that have their angles adjusted may become looser, less rigid, and less comfortable than a custom molded splint [Walker et al. 2000].

Generally, custom splints are recommended for CTS because they provide better support, positioning [McClure 2003], and more constant allocation of pressure over the carpal tunnel than prefabricated splints—especially those that are incorrectly fitted [Hayes et al. 2002]. If a person does not tolerate a custom-made splint, the therapist may need to consider providing a prefabricated splint [personal communication, Lynn, 2003].

Another consideration with the wrist immobilization splint provision is the amount of finger flexion allowed. Recent research evidence suggests that finger flexion affects carpal tunnel pressure, especially if fingers fully flex to form a fist [Apfel et al. 2002]. That is because the lumbrical muscles may sometimes enter the carpal tunnel with finger flexion [Cobb et al. 1995, Seigel et al. 1995]. When splints are provided to clients with CTS, they should be instructed to not flex their fingers “beyond 75% of a full fist” [Apfel et al. 2002, p. 333]. Therefore, therapists should check finger position with splint provision. Osterman et al. [2002] advised therapists to fabricate a volar wrist splint with a metacarpal block to decrease finger flexion if CTS symptoms are not improving.

When fabricating a splint for a person who has CTS, the therapist considers home and occupational demands carefully, keeping in mind that the wrist contributes to the overall function of the hand [Schultz-Johnson 1996]. If a splint is worn at work, durability of the splint and the ability to wash it may be salient. Some people may benefit from the fabrication of two splints (one for work and one for home), especially if their job demands are in an unclean environment. Many computer operators tolerate a splint that supports the wrist position in the plane of flexion and extension but allows 10 to 20 degrees of radial and ulnar deviation for effective typing. Fabricating a slightly wider metacarpal bar on a custom-made wrist splint allows for a small area of mobility on the radial and ulnar sides of the hand [Sailer 1996]. Finally, the therapist simulates work and home tasks with the wrist immobilization splint on the person to check for functional fit [Sailer 1996].

Therapists also take into account splint-wearing schedules. Options that can be prescribed are nighttime wear only, wear during activities that irritate the condition, a combination of the latter two schedules, or constant wear. In one study, subjects were found to benefit most from full-time wear of the splint, but wearing compliance was an issue [Walker et al. 2000]. This study further validated improvements in clients who wore a neutral position wrist splint for six weeks. Nevertheless, it is important to consider nighttime wear of splints because some people maintain extreme wrist flexion or extension postures during sleep [Sailer 1996].

An exercise program issued with a splint may be an effective conservative treatment [Rozmaryn et al. 1998]. In one study (n =197), a conservative treatment program for CTS that combined nerve and tendon gliding exercises with wrist immobilization splinting was found to be more effective in helping people avoid surgery than splint wear alone. It is hypothesized that these exercises help improve the excursion of the median nerve and flexor tendons because the exercises may contribute to the remodeling of the adhered tenosynovium [Rozmaryn et al. 1998]. Akalin et al. [2002] (n = 28) also studied tendon and nerve gliding exercises with splinting compared to splinting alone. Ninety-three percent of the splinting and exercise group participants reported good to excellent results compared to 72% of the splint-only group participants. However, the researchers did not consider the results statistically significant. Both studies accentuate the value of early conservative intervention.

Other effective treatment measures for CTS are the modification of activities (so that the person does not make excessive wrist and forearm motions, especially wrist flexion). It is also important to avoid sustained pinch or grip activities and to use good posture whenever possible with all activities of daily living (ADL). Because CTS is generically a disease of decreased blood supply to the soft tissues. Nerves need blood supply and an environment that is cold will additionally deprive the nerve of blood. Thus, staying warm is an important part of CTS care and splints provide local warmth [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 6, 2006]. When conservative measures are ineffective, surgery is an option.

The goals of wrist splinting after carpal tunnel release surgery are to minimize pressure on the median nerve, prevent bowstringing of the flexor tendons [Cook et al. 1995], provide support during stressful activities, maintain gains from exercise [Messer and Bankers 1995; personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 1999], and rest the extremity during the immediate healing phase. Some therapists do not apply a wrist immobilization splint postoperatively because of concerns about the impact of immobilization on joint stiffness and muscle shortening [Hayes et al. 2002]. Findings from one study [Cook et al. 1995] (n=50) suggest that splinting post-surgery resulted in joint stiffness as well as delays with returning to work, recovering grip and pinch strength, and resuming ADL. These researchers concluded that if splinting is used it should be applied for one week only postoperatively to prevent tendon bowstringing and nerve entrapment.

Splinting postoperatively is recommended to prevent extreme nighttime wrist postures (flexion and extension) or to manage inflammation [Hayes et al. 2002]. Therapists instruct the person to gradually wean away from the splint (when the splint is no longer meeting the person’s therapeutic goals) in order to prevent stiffness and allow the person to return to work and ADL more quickly. Weaning is often done over the course one week, gradually decreasing the hours of splint wear [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 6, 2006].

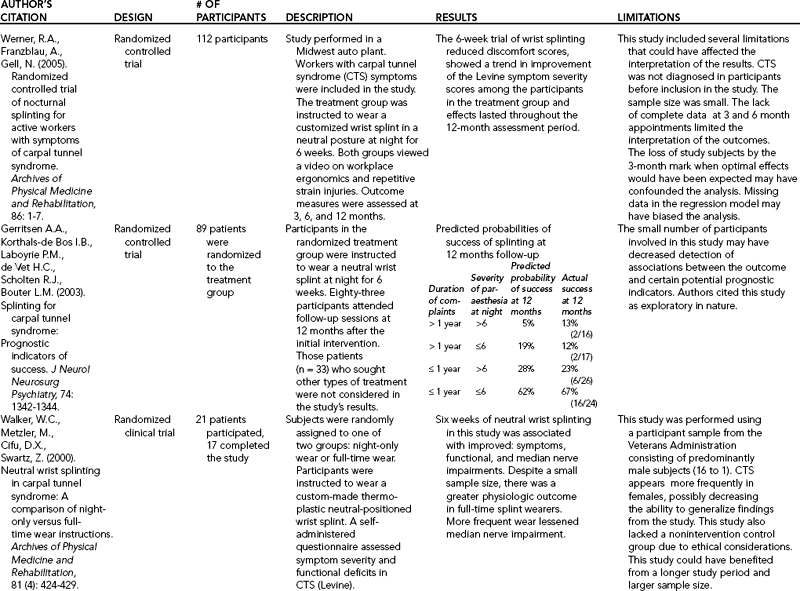

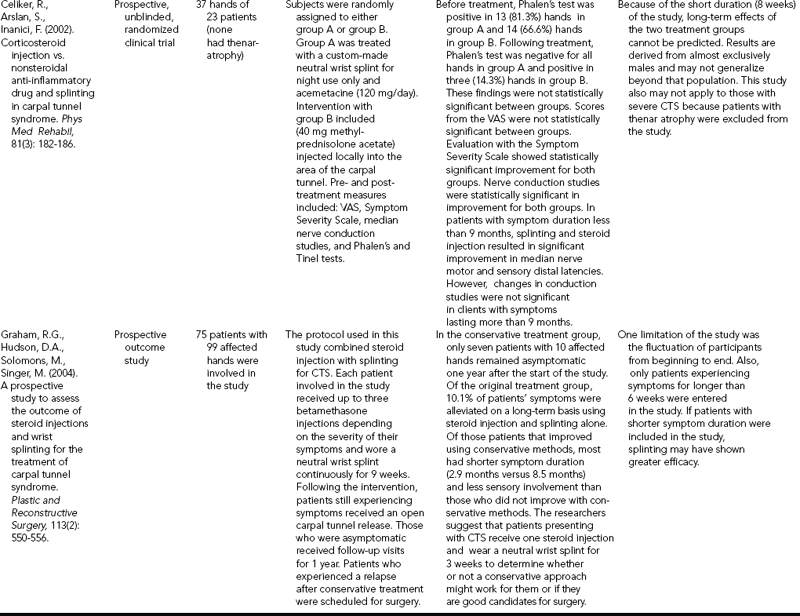

A series of recent studies were conducted to examine splinting compared to other treatments, such as surgery or steroid injections (seeTable 7-2, which outlines the research evidence). The majority of studies comparing splinting to surgery favored surgery as the most effective treatment for CTS [Gerritsen et. al 2002, Verdugo et al. 2004]. Splinting did show some promising results, but was not as strong in efficacy as surgery. For example, with the Gerrtisen et al. [2002] study (n=178) after 18 months 75% of the subjects improved with splint wear as compared to 90% of the surgery group. The researchers recommended that splinting is beneficial while waiting for surgery, or if a client does not desire surgery. When considering the results of this study, therapists should recognize that 75% improvement with splinting is a high success rate and is less risky than having surgery. Some people do not want therapy, splinting, and activity modification and therefore may best benefit from a surgical approach [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 6, 2006].

Therapists need to critically examine such studies for limitations when making an informed decision for clients. McClure [2003], in an article on evidenced-based practice, considered limitations of studies about splinting with CTS. For example, he questioned the results of the Verdugo et al. [2004] study. He queried whether the same results would have occurred with mild CTS symptoms and that the study was done with “only one small randomized trial” [McClure 2003, p. 259]. McClure [2003] also considered the limitations of the Gerritsen et al. [2002] study. He mentioned that information regarding the splint-wearing schedule, other treatments, how clients were classified, and symptom severity were missing from the study [McClure 2003].

Other researchers examined the effect of splinting and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (n=33 hands) [Celiker et al. 2002, Graham et al. 2004]. Celiker et al. [2002] (n=99 hands) found that splinting along with steroid injections for clients who had symptoms less than nine months resulted in significant improvement. In another study, steroid injections and wrist splinting for three weeks was found to be effective in clients who had symptoms of less than three months duration and no residual sensory impairments [Graham et al. 2004]. Using only splints for CTS was also studied (n=66 subjects), with significant improvement after four weeks reported [O’Connor et al. 2003]. Gerritsen et al. [2003] (n=89 subjects) reported that the shorter duration of complaints and the severity of nocturnal parasthesias were positively related to splinting success.

Therapists and physicians must be aware of current studies because these can influence treatment approaches. Therapists need to critically question how the studies were performed and be aware of limitations. As McClure [2003, p. 261] stated, “these details are important in deciding whether my patient is similar enough to those in the study to use these results with her.” Awareness of current research also points to the fact that many of these studies emphasize the importance of splinting with early intervention because splints are less beneficial with ongoing parasthesia [Burke et al. 2003].

Wrist Splinting for Radial Nerve Injuries

Radial nerve injuries most commonly occur from fractures of the humeral shaft, fractures and dislocation of the elbow, or compressions of nerve [Skirven 1992]. Other reasons for radial nerve injuries include lacerations, gunshot wounds, explosions, and amputations. The classic picture of a radial nerve injury is a wrist drop position whereby the wrist and MCP joints are unable to actively extend. If the wrist is involved, sometimes a physician may order a wrist splint to place the wrist in a more functional position. The exact wrist positioning is highly subjective, and it is up to the therapist and the client to decide on the amount of extension that maximizes function.

Commonly, 30 degrees of extension is considered a position of function because it facilitates optimum grip and pinch [Cannon 1985]. Although a wrist splint is one option that can be fabricated for this condition, there are many other options therapists should critically consider. These include the location of splinting (volar versus dorsal), type of splint (e.g., wrist immobilization, tendodesis, or a splint with static elastic tension), and whether to fabricate one or two splints. More details about these other types of splinting options for a radial nerve injury are discussed in Chapter 13.

Wrist Splinting for Tendinitis and Tenosynovitis

Tendinitis (inflammation of the tendon), tenosynovitis (inflammation of the tendon and its surrounding synovial sheath), and tendinosis (a non-inflammatory tendon condition that involves collagen degeneration and disorganization of blood flow) [Khan et al. 2000] are painful conditions that benefit from conservative management, including wrist splinting. These conditions commonly occur because of cumulative and repetitive motions in work, home, and leisure activities. Tendinosis is more chronic in nature than tendonitis or tenosynovitis and usually impacts the lateral and medial elbow and rotator cuff tendons of the upper extremity [Khan et al. 2000]. Having tendonitis and tenosynovitis can result in an overuse cycle. The overuse cycle begins with friction, microscopic tears, pain, and limitations in motion, followed by resting the involved area, avoidance of use, and development of weakness. When activities resume, the cycle repeats itself [Kasch 2002]. Tendinitis or tenosynovitis can occur in many of the muscles on the volar (flexor muscles) and dorsal (extensor muscles) surfaces of the forearm.

These conditions often lead to substitution patterns and muscle imbalance [Kasch 2002]. Resting the hand in a splint helps to take tension off the muscle-tendon unit. Splinting for tendinitis or tenosynovitis minimizes tendon excursion and thus decreases friction at the insertion of the muscles. Splinting can serve as a reminder to decrease engagement in painful activities. It is beneficial to ask clients to pay attention to those activities that are limited by a splint because they are often aggravating factors for tendonitis. Clients should become more cognizant of aggravating activities and modify them so as not to enhance the condition [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 6, 2006]. Clients should also be cautioned not to tense their muscles and thus fight against the splint when wearing it or it may aggravate the tendonitis. Rather, the muscles should be relaxed. Splints provided for tendonitis or tenosynovitis during acute flare-ups are worn continuously, with removal for hygiene and range-of-motion (ROM) exercises followed by gradual weaning.

Generally, when splinting for flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tenosynovitis it is recommended that the person’s wrist be splinted at neutral to rest the tendons [Idler 1997]. Wrist extensor tendinitis can be splinted in 20 to 30 degrees of wrist extension, as this normal resting position provides a balance between the flexors and extensors.

Wrist Splinting for Rheumatoid Arthritis

For some conditions—such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA)—therapists fabricate wrist immobilization splints in functional positions of 0 to 30 degrees of wrist extension, thus promoting synergistic wrist-extension and finger-flexion patterns. This position allows the greatest level of function with grip ADL [Palmer et al. 1985, Melvin 1989].

Wearing a wrist splint may be used to control pain during activities [Kozin and Michlovitz 2000], and doing so is especially helpful in protecting the wrist during demanding tasks [Stern et al. 1997]. For people with radiocarpal or mid carpal arthritis, a wrist splint fabricated out of thin 1/16-inch thermoplastic material is recommended [Kozin and Michlovitz 2000]. For a total wrist arthrodesis, a volar wrist splint is provided when the cast is removed (usually about week 6 to 8). This volar wrist splint is worn full-time for 8 to 12 weeks [Bednar and Von Lersner-Benson 2002].

Wrist splinting for someone with RA can be quite challenging because of the tendency for the carpal structures of the rheumatoid arthritic wrist to sublux volarly and ulnarly [Dell and Dell 1996]. In addition, there can be related digital involvement to consider, such as MCP ulnar drift. In the early stages of this ulnar drift, the wrist joint should be positioned as close to neutral with respect to radial and ulnar deviation as can be comfortably tolerated. With consistent access to the person, the therapist can progress the wrist into neutral on successive visits. This position helps eliminate the development of a zigzag deformity. The zigzag deformity develops when the carpal bones deviate ulnarly and the metacarpals deviate radially, which exacerbates the ulnar deviation of the MCP joints [Dell and Dell 1996].

If the MCP joints but not the interphalangeal (IP) joints are involved, the therapist may consider fabricating a wrist splint in a neutral position that extends beyond the distal palmar crease and ends proximal to the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) crease. This splint supports the MCP joints (Figure 7-8) [Philips 1995]. Another recommendation for splinting someone with a zigzag deformity is to splint the entire hand (see Chapter 9).

Figure 7-8 A splint for a zigzag deformity. [From Philips CA (1995). Therapist’s management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In JM Hunter, EJ Mackin, AD Callahan (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 1345-1350.]

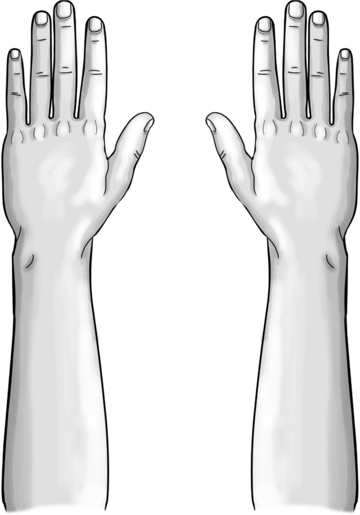

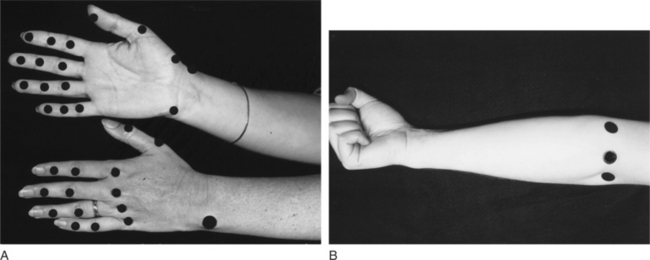

When fabricating a wrist splint for a person with RA, the therapist uses a thermoplastic material with a high degree of conformability and drapability to help prevent pressure areas. However, when additional assistance is not available the long working time that highly rubber-based thermoplastic materials provide will help the therapist create a more cosmetic and well-fitting splint [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 6, 2006]. The therapist carefully monitors for the development of pressure areas over many of the small bones of the hand and wrist, as shown inFigure 7-9 [Dell and Dell 1996]. Finally, some people with RA may prefer a prefabricated splint that is easy to apply and is perceived to be more comfortable than a fabricated splint because it is made out of softer material and has more flexibility. Further discussion later in this chapter addresses the functional implications of commercial wrist splints with RA.

Figure 7-9 Potential areas of fingers, hand, wrist, and forearm include: dorsal MCP joints, thumb webspace, ulnar styloid, radial styloid, thumb CMC joint, center of palm (especially with flexion wrist contractures), proximal edge of splint. From Fess EE, Gettle KS, Phillips CA, et al: Hand and Upper Extremity Rehabilitation: Principles and Methods, ed 3, St. Louis, 2005, Mosby.

Wrist Splinting for Fractures

The initial goal of rehabilitation after a fracture of the distal radius is to regain functional wrist extension [Laseter and Carter 1996]. To achieve this goal, splinting of the wrist in slight extension is beneficial while the person is receiving therapy. Wrist splinting post-fracture provides “protection and low load stress.” It is best to fabricate a custom splint because prefabricated splints may not fit comfortably and may block range of motion of the fingers and thumb [Laseter 2002]. Sometimes serial static splinting may be necessary to regain PROM. (See the discussion later in this chapter for more details about serial static splinting).

The therapist fabricates a well-designed custom dorsal or volar splint. Laseter [2002] recommends fabricating a dorsal wrist splint because it helps control edema and allows for functional motions of the finger joints. If the person needs more support, a circumferential wrist splint may be considered [Laster 2002]. Circumferential splinting is highly supportive and very comfortable. It tends to limit forearm rotation more than a volar or dorsal wrist splint does [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 1999]. The client should be weaned away from any splint as soon as possible [Laseter and Carter 1996, Laseter 2002]. To encourage regaining function, Weinstock [1999] recommended that the splint be part of treatment until 30 degrees to 45 degrees of active extension is obtained. For minimally displaced Colles’ fractures, one researcher suggested that when a prefabricated Futuro splint was worn continuously for two weeks (with removal for hygiene) over a 6-week period subjects regained function faster than casted subjects [Mullett et al. 2003].

Wrist Splinting for Sprains

A grade I sprain results in a substance tear with minimal fiber disruption and no obvious tear of the fibers. A mild grade II sprain results in tearing of the ligament fibers. Persons with grade I and II sprains may benefit from wearing a wrist immobilization splint. With grade I sprains, the person will likely wear the splint for 3 weeks. For grade II sprains, 6 weeks of wear may be indicated. This wrist splint helps rest the hand during the acute healing phase and removes stress from the healing ligament.

Wrist Splinting for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I (Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy)

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) describes a complex grouping of symptoms impacting an extremity and characterized by extreme pain, diffuse edema, stiffness, trophic skin changes, and discoloration [Taylor-Mullins 1992, Lankford 1995]. CRPS type I is a newer term coined by the World Health Organization to distinguish between sympathetically mediated and non-sympathetically mediated pain. CRPS type I is a sympathetically mediated pain [Mersky and Bogduk 1994, Phillips 2005]. CRPS type I refers to pain from a minor injury that lasts longer and hurts more than is anticipated. Type II refers to pain related to a nerve injury. Symptoms are similar for both types of pain [Phillips 2005].

Splinting is an important part of the rehabilitation program. The therapist applies clinical reasoning skills to determine which splint will meet the various therapeutic goals. (See the discussion on the use of resting hand splints with this condition in Chapter 11). The purposes for providing wrist immobilization splints include pain relief, muscle spasm relief, and regaining a functional resting wrist position [Lankford 1995, Saidoff and McDonough 1997, Walsh and Muntzer 2002]. Getting back to a functional resting hand position is important for normal hand motions and for the prevention of deforming forces as a result of muscle imbalance. To increase wrist extension to a more functional position, the therapist may need to provide serial wrist splints.

Wrist Joint Contracture: Serial Splinting with a Wrist Splint

When a wrist is not properly moving, as after removal of a cast for a Colles’ fracture, the therapist may consider serial wrist splinting [Reiss 1995]. With serial splinting, the therapist intermittently remolds the splint to help increase wrist extension (Figure 7-10). The splint is first applied with the wrist positioned at the maximal amount of extension the current soft-tissue length allows and the person can tolerate. The person is instructed to wear the splint for long periods of time, with periodic removal for exercise and hygiene, until the wrist is able to move beyond that amount of extension.

The splint is readjusted to position the soft tissues at their maximum length [Colditz 2002]. Positioning living tissue at maximum length causes the tissue to remodel to a longer length [Schultz-Johnson 1996]. This process is repeated until optimal wrist extension is regained. Thus, serial splinting is beneficial for PROM limitations because it provides long periods of low load stress at or near the end of the soft-tissue length [Schultz-Johnson 1996]. Serial wrist splinting is only one splinting approach that can improve wrist PROM. Other approaches include fabricating a static progressive splint and an elastic tension splint (see Chapter 11).

Fabrication of a Wrist Immobilization Splint

The initial step in the fabrication of a wrist immobilization splint (after evaluation of the person’s hand) is the drawing of a pattern. Pattern making is important in customizing a splint because every person’s hand is different in shape and size. Pattern making also saves time and minimizes waste of materials.

A common mistake of a beginning splintmaker during fabrication of a wrist immobilization pattern is drawing the forearm trough narrower than the natural curve of the forearm muscle-bulk contour. This mistake can occur with anyone but especially with a person who has a large forearm. If the forearm trough is not one-half the circumference of the forearm, the splint does not provide adequate support. In addition, the therapist must follow the natural angle of the MCP heads with the pattern.

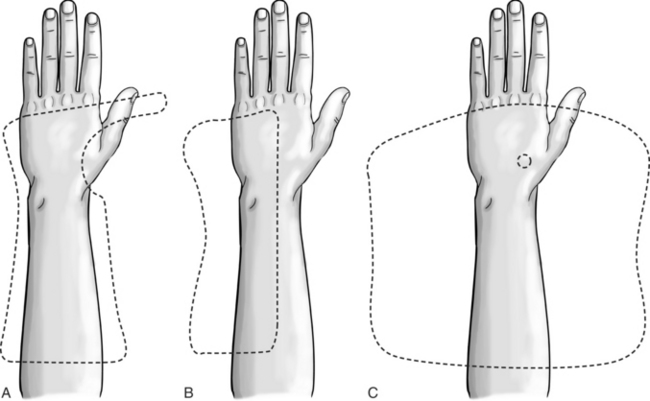

A volar wrist immobilization pattern presents another splinting option (Figure 7-11A). It is sometimes called a thumb-hole wrist splint [Stein 1991]. The therapist constructs the splint by punching a hole with a leather punch in the heated thermoplastic material and pushing the thumb through the hole. The therapist rolls the material away from the thumb and thenar eminence far enough that it does not interfere with functional thumb movement and yet allows adequate wrist support (Figure 7-11B). This thumb-hole wrist splint was found to be the most restrictive of wrist motion and slowest with dexterity performance compared with volar and dorsal wrist splints with metacarpal bars [Stein 1991, p. 47].Figure 7-12A shows a pattern for a dorsal wrist immobilization splint.Figure 7-12B shows a pattern for an ulnar wrist immobilization splint.Figure 7-12C shows a pattern for a circumferential wrist immobilization splint.

Figure 7-11 (A) A volar wrist immobilization pattern for a thumb-hole splint. (B) A volar wrist immobilization thumb-hole splint.

Figure 7-12 (A) A dorsal wrist immobilization pattern. (B) An ulnar wrist immobilization pattern. (C) A circumferential wrist immobilization pattern.

Beginning splintmakers may learn to fabricate splint patterns by following detailed written instructions and looking at pictures of patterns. As therapists gain experience, they can easily draw patterns without copying from pictures. (See Figures 7-1, 7-2, 7-3, and 7-4 for pictures of completed splint products.) The following instructions are for construction of a volar wrist immobilization splint (Figures 7-6 and 7-13) and are similar to instructions for a dorsal wrist immobilization splint (Figures 7-7 and 7-12A).

1. Position the person’s hand palm down on a piece of paper. The wrist should be as neutral as possible with respect to radial and ulnar deviation. The fingers should be in a natural resting position and slightly abducted. Draw an outline of the hand and forearm to the elbow.

2. While the person’s hand is still on the paper, mark an A at the radial styloid and a B at the ulnar styloid. Mark the second and fifth metacarpal heads C and D, respectively. Mark the olecranon process of the elbow E. Remove the hand from the pattern. Mark two-thirds the length of the forearm on each side with an X. Place another X on each side of the pattern about 1 to 1-½inches outside and parallel to the two previous X markings for two-thirds the length of the forearm and label each F. These markings are to accommodate for the side of the forearm trough.

3. Draw an angled line connecting the marks of the second and fifth metacarpal heads (C to D). Extend this line approximately 1 to 1-½inches from the ulnar side of the hand and mark it G. On the radial side of the hand, extend the line straight out approximately 2 inches and mark it H.

4. On the ulnar side of the splint, extend the metacarpal line from the G down the hand and forearm of the splint pattern, making sure the pattern follows the person’s forearm muscle bulk. End this line at F.

5. Measure and place an I approximately ¾inch below the mark for the head of the index finger (C). Extend a line parallel from I to the line between C and H. Curve this line to meet H. This area represents the extension of the MP bar and usually measures approximately ¾inch down from C to the outline on the other side of the MP bar. Draw a curved line that simulates the thenar crease from I to A. Extend the line past A about 1 inch and mark it J.

6. Draw a line from J down the radial side of the forearm, making sure the line follows the increasing size of the forearm. To ensure that the splint is two-thirds the length of the forearm, end the line at F.

7. For the bottom of the splint, draw a straight line connecting both F marks.

8. Make sure the pattern lines are rounded at H, G, J, and the two Fs.

10. Position the person’s upper extremity with the elbow resting on a pad (folded towel or foam wedge) on the table and the forearm in a neutral position rather than in supination or pronation, which results in a poorly fitted splint. Make sure the fingers are relaxed and the thumb is lightly touching the index finger. Place the wrist immobilization pattern on the person as shown inFigure 7-14A. Check that the wrist has adequate support, with the pattern ending just proximal to the MCP joint. On the dorsal surface of the hand, check whether the hypothenar bar on the ulnar side of the hand ends just proximal to the fifth metacarpal head. The metacarpal bar on the radial side of the hand should point to the triquetrum or distal ulna bone after it wraps through the first web space. On the volar surface of the hand, check below the thumb CMC joint to determine whether the pattern provides enough support at the wrist joint. Make sure the forearm trough is two-thirds the length and one-half the width of the forearm. Make necessary adjustments (i.e., additions or deletions) on the pattern.

11. Trace the pattern onto the sheet of thermoplastic material.

12. Heat the thermoplastic material.

13. Cut the pattern out of the thermoplastic material.

14. Measure the person’s wrist using a goniometer to determine whether the wrist has been placed in the correct position. The therapist should instruct and practice with the person maintaining the correct position (Figure 7-14B).

15. Reheat the thermoplastic material.

16. Mold the form onto the person’s hand. To fit the splint on the person, place the person’s elbow in a resting position on a pad on the table with the forearm in a neutral position. Make sure the fingers are relaxed and the thumb is lightly touching the index finger (Figure 7-14C). The advantage of this approach is that the therapist can better monitor the wrist position visually during splint formation.

17. Make sure the wrist remains correctly positioned as the thermoplastic material hardens. During the formation phase, roll the metacarpal bar just proximal to the distal palmar crease and roll the thermoplastic material toward the thenar crease. Flair the distal end of the splint on a flat surface (Figure 7-14D).

18. Make necessary adjustments on the splint (Figures 7-14E and 7-14F).

19. Cut the Velcro into approximately ½-inch oval shaped pieces for the MP bar area and 1-½-inch oval pieces for the forearm trough. Heat the adhesive with a heat gun to encourage adherence before putting them on the splint. Using a solvent on the thermoplastic material, scratch the thermoplastic material to remove some of the non-stick coating to help with adherence of the Velcro pieces (Figure 7-14G). For an adult, add two 2-inch straps on the forearm trough and one narrower strap on the dorsal surface of the hand, thus connecting the MP bar on the radial side to the hypothenar bar on the ulnar side of the hand. A child’s splint will require straps that are narrower than an adult’s. The strap placed at the wrist is located exactly at the wrist joint and not proximal to it to ensure a good fit (Figure 7-14H).

Technical Tips for a Proper Fit

• Choose a thermoplastic splinting material that has a high degree of conformability to allow a close fit and to prevent migration. Some therapists may prefer a rubber-based moderate drape thermoplastic material.

• Use caution when cutting a pattern out of thermoplastic material that stretches easily. Leave stretchable thermoplastic material flat on the table when cutting to prevent the material from stretching and the splint from losing the original shape of the pattern.

• Be sure the person’s forearm is in neutral when forming the splint. Avoid splinting the forearm in a fully supinated or pronated position.

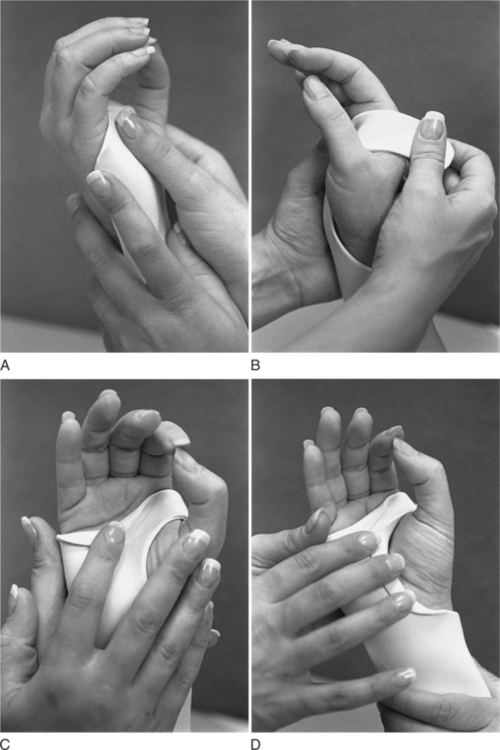

• It helps to mold the splint sequentially. For a volar wrist immobilization splint, form the hypothenar bar (Figure 7-15A), wrap the metacarpal bar around the palm to the dorsal side of the hand (Figure 7-15B), roll down the metacarpal bar (Figure 7-15C), and then form the thenar area (Figure 7-15D). See the specific comments in this section for hints about each of these areas.

• As the splint is being formed, be sure to follow the natural curves of the longitudinal, distal, and proximal arches. Having the person lightly touch the thumb to the index finger during molding will help conform the splint to the arches of the hand (Figure 7-14C). Mold the thermoplastic material to conform naturally to the center of the palm. Be careful not to flatten the transverse arch, which could cause metacarpal contractures. However, overemphasizing the transverse carpal arch can create a focal pressure point in the central palm that will be intolerable for the person.

• For a volar wrist immobilization splint, position the metacarpal bar on the volar surface just proximal to the distal palmar crease. This position allows adequate wrist support and full MCP flexion. In addition, make sure the metacarpal bar follows the natural angle of the distal transverse arch (Figure 7-15B). On the dorsal surface, position the metacarpal bar just proximal to the natural angle of the MCP heads. A correctly conformed dorsal metacarpal bar helps to hold the wrist in the correct position. If the metacarpal bar does not conform and there is a gap, the wrist will be mobile.

• Always determine whether the person has full finger flexion when wearing the splint by having him or her flex the MCP joints. If any areas of the metacarpal bar are too high, the therapist makes adjustments.

• Make sure the hand and wrist are positioned correctly by taking into consideration the position of a normal resting hand. On volar and dorsal wrist immobilization splints, the metacarpal bar (which wraps around the radial side of the hand) and the hypothenar bar (on the ulnar side) help position and hold the wrist (Figure 7-16). If adequate support is lacking on either side, the wrist may be in an incorrect position.

• A frequent fabrication mistake is to allow the wrist to deviate radially or ulnarly. This mistake can occur because of a lack of careful monitoring of the person’s wrist position as the thermoplastic material is cooling. The therapist should closely monitor the wrist position in any splint that positions the wrist in neutral, because it is easy for the wrist to move in slight flexion. A quick spot check before the thermoplastic material is completely cool can address this problem.

• If a mistake occurs with a splint material that easily stretches, be extremely careful with adjustments to avoid further compromising of wrist position. For splinting material with memory, remold the entire splint rather than spot heating the wrist area because doing the latter tends to cause the material to buckle. Sometimes adjustments can be done by heating the entire splint made from material without memory.

• After the formation of the palmar and wrist part of the splint is complete, the therapist can begin to work on other areas of the splint, such as the forearm trough. A problem that can easily be corrected just before the thermoplastic material is cooled is twisting of the forearm trough. If this problem is not corrected, the splint will end up with one edge of the forearm trough higher than the other (Figure 7-17).

• After the thermoplastic material has cooled, determine whether the person can fully oppose the thumb to all fingers. The thenar eminence should not be restricted or flattened. Wrist support should be adequate to maintain the angle of the wrist. To check whether the thenar eminence area is rolled enough, have the person move the thumb in opposition to the little finger and sustain the hold while evaluating the roll. Also observe that the thenar crease is visible, to allow for full thumb mobility. Adjustments should be made to allow complete thumb excursion. Otherwise, there is a potential for a pressure sore to develop (Figure 7-18).

• Sometimes after the thermoplastic material is cooled the therapist will note areas that are too tight in the forearm trough, which can potentially result in pressure sores. To easily correct this problem, the therapist pulls apart the sides of the forearm trough.

Trouble Shooting Wrist Immobilization Splints

A careful splintmaker must continuously think of precautions, such as checking for pressure areas. Precautions for making a wrist immobilization splint include the following.

• Be aware of and make adjustments for potential pressure points on the radial styloid, on the ulnar styloid, at the first web space, and over the dorsal aspects of the metacarpals. The thumb web space is a prime area for skin irritation because it is so tender. Some people cannot tolerate plastic in the first web space, and it must be cut back and replaced with soft strapping. Others can tolerate the plastic if it is rolled and extremely thin [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, April 1999]. Instruct the person to monitor the skin for reddened areas and to communicate immediately about any irritation that occurs.

• Try to control edema before splint provision. For persons with sustained edema, avoid using constricting wrist splints. Instead, fabricate a wider forearm trough with wide strapping material [Cannon et al. 1985]. Dorsal splints are better for edematous hands [Colditz 2002, Laseter 2002]. Carefully monitor persons who have the potential for edematous hands and make necessary splint adjustments. As discussed earlier, a “continuous strap” made out of flexible fabric is a good strapping option to help manage edema.

• For persons with little subcutaneous tissue and thin skin, carefully monitor the skin for pressure areas. Lining the splint with padding may help, but several adjustments may be necessary for a proper fit. Sometimes fabricating the splint over a thick splint liner or a QuickCast liner helps prevent skin irritation during splint fabrication.

• Make sure the splint provides adequate support for functional activities.

• Wrist immobilization splints are contraindicated for persons with active MCP synovitis and PIP synovitis [Melvin 1989]. These conditions often occur in hands with rheumatoid arthritis and may require wrist and hand splinting.

Prefabricated Splints

Prefabricated wrist splints are commonly used in the treatment of CTS and RA [Dell and Dell 1996, Stern et al. 1997, Williams 1992]. A variety of prefabricated wrist splints are available, as shown inTable 7-3.

Table 7-3

Prefabricated Wrist Splint Examples

| THERAPEUTIC OBJECTIVE | DESCRIPTION |

| Positions the wrist in neutral, extension, or slight flexion to support and rest the wrist joint during functional tasks | Circumferential wrist splints are available in a variety of sizes. Some wrist splints have a metal or thermoplastic stay, which usually can be adjusted to position the wrist in neutral, extension, or slight flexion. Options available include D-ring straps (Figure 7-19A) and wrist support with laces (Figure 7-19B). Another wrist splinting option is this lightweight splint for CTS (Figure 7-19C). Splints are available in such materials as cloth, thermoplastic, neoprene (Figure 7-19D), elastic, and polyester/cotton laminates. |

As discussed, conservative management of CTS includes positioning the wrist as close to neutral as possible to maximize the space in the carpal tunnel. The supportive metal or thermoplastic stay in most prefabricated wrist splints positions the wrist in extension. Therefore, an adjustment must be made to position the wrist in the desired neutral position. However, care must be taken when adjustments are made to ensure that the splint adequately fits and supports the hand.

Several options for prefabricated wrist splints are marketed for CTS. Options for the work environment include padding to reduce trauma from vibration, leather for added durability, and metal internal pieces that act to position the wrist. Prefabricated wrist immobilization splints are also effective for symptoms of CTS during pregnancy [Courts l995]. (SeeFigure 7-19.)

Figure 7-19 (A)This wrist splint has D-ring straps (Rolyan D-Ring Wrist Brace). (B) This wrist splint has a unique strapping system with laces (Sammons Preston Rolyan Laced Wrist Support). (C) This light weight splint can be used for carpal tunnel and other repetitive injuries (Exolite Wrist Brace). (D) This splint is made of a neoprene blend, which allows circulation to the skin (Termoskin Wrist Brace). [Courtesy of Sammons Preston Rolyan, Bolingbrook, IL.]

Splinting a person who has RA is most effective in the early stages and incorporates positioning, immobilization, and the assumed comfort of neutral warmth from a soft splint. The effects of RA can result in decreased joint stability, leading to decreased grip strength and the more obvious finger deformities [Dell and Dell 1996]. When persons with RA wear elastic wrist orthoses, they help decrease pain during ADL [Stern et al. 1996]. Prefabricated wrist splints marketed for persons with RA are designed for easy application and to decrease ulnar deviation. Some splints include correction or protection for finger joints as well as for the wrist joint.

Therapists need to determine whether or not to fabricate a custom wrist splint or to use a commercial prefabricated wrist splint. There are many factors to consider with this decision, such as the impact of the prefabricated or custom splint on hand function, pain reduction, and degrees of immobilization the splint provides [Stern et al. 1996a, 1996b; Pagnotta et al. 1998; Collier and Thomas 2002]. Research helps therapists select the best splint for their clients. Collier and Thomas [2002, p. 182] studied the degree of immobilization of a custom volar wrist splint as compared to three commercial prefabricated wrist splints. They found that the custom wrist splint allowed “significantly less palmar flexion and significantly more dorsi flexion” than the commercial splints. Thus, custom thermoplastic splints may block wrist motion better than prefabricated splints, which are more flexible.

Other studies considered the effect of commercial prefabricated splints on grip and dexterity [Stern 1996; Stern et al. 1996a, 1996b; Burtner et. al 2003], work performance [Pagnotta et al. 1998], and proximal musculature [Bulthaup et al. 1999]. SeeTable 7-2 for more details about the efficacy of these studies. Continued research needs to be done to analyze the efficacy of commercial splints, especially as newer ones are developed. Furthermore, as Stern et al. [1997] found, no single type of wrist splint will be appropriate for all clients and that satisfaction with a prefabricated splint is often associated with therapeutic benefits, comfort, and utility. Therefore, it benefits therapists to stock a variety of prefabricated splint options in the clinic [Stern et al. 1997].Box 7-1 provides some questions for therapists to contemplate when considering a prefabricated wrist splint or custom-made wrist splint.

Impact on Occupations

Supporting the wrist to allow finger and thumb motions enables people with the discussed diagnoses in this chapter to continue their life occupations. For example, a person with CTS wears a wrist splint to avoid extreme wrist positions when working and doing other occupations. A person with arthritis obtains support and pain relief from wearing a wrist splint while doing functional activities. A person with a Colles’ fracture after being serial splinted to decrease stiffness will eventually be able to better perform meaningful occupations. Wrist splints can help many people maintain or eventually improve their functional abilities.

Summary

As this chapter content reflects, appropriate wrist alignment is very important to maintaining a functional hand. A well-fitted splint can be a key element to assist with recovery from many conditions. Therefore, therapists should be aware of diagnostic indications, types, parts, and appropriate fabrication for wrist splinting. As always in clinical practice, the therapist will need to apply clinical reasoning, as each case will be different. Finally, therapists should consider the person’s occupations when providing a wrist splint.

1. What are three main indications for use of a wrist immobilization splint?

2. When fabricating a wrist splint for a person with RA, what are some of the common deformities that can influence splinting?

3. When might a therapist consider serial splinting with a wrist immobilization splint?

4. What are the goals of wrist splinting with a Colles’ fracture?

5. What is the advantage of a volar wrist immobilization splint?

6. What is a disadvantage of a dorsal wrist immobilization splint?

7. What purpose does the hypothenar bar serve on a wrist immobilization splint?

8. What are two positions the therapist can use for molding a static wrist splint, and what are the advantages of each?

9. Which precautions are unique to static wrist immobilization splints?

10. What are four questions therapists could consider when deciding on a prefabricated wrist splint versus a custom fabricated wrist splint?

References

Alakin, E, El, O, Peker, O, Senocak, O, Tamaci, S, Gulbahar, S, et al. Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome with nerve and tendon gliding exercises. The American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2002;81:108–113.

American Society of Hand Therapists. Splint Classification System. Chicago: American Society of Hand Therapists, 1992.

Apfel, E, Johnson, M, Abrams, R. Comparison of range-of-motion constraints provided by prefabricated splints used in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: A pilot study. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2002;15(3):226–233.

Bednar, JM, Von Lersner-Benson, C. Wrist reconstruction: Salvage procedures. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1195–1202.

Bell-Krotoski, JA, Breger-Stanton, DE. Biomechanics and evaluation of the hand. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:240–262.

Biese, J. Therapist’s evaluation and conservative management of rheumatoid arthritis in the hand and wrist. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1569–1582.

Bulthaup, S, Cipriani, DJ, Thomas, JJ. An electromyography study of wrist extension orthoses and upper extremity function. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1999;53(5):434–444.

Burke, FD, Ellis, J, McKenna, H, Bradley, MJ. Primary care management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2003;79(934):433–437.

Burtner, PA, Anderson, JB, Marcum, ML, Poole, JL, Qualls, C, Picchiarini, MS. A comparison of static and dynamic wrist splints using electromyography in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2003;16(4):320–325.

Cannon, NM. Manual of Hand Splinting. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1985.

Celiker, R, Arslan, S, Inanici, F. Corticosteroid injection vs. nonsteriodal antiinflammatory drug and splinting in carpal tunnel syndrome. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2002;81(3):182–186.

Cobb, TK, An, KN, Cooney, WP. Effect of lumbrical muscle incursion within the carpal tunnel on carpal tunnel pressure: A cadaveric study. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1995;20A(2):186–192.

Colditz, JC. Therapist’s management of the stiff hand. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1021–1049.

Collier, SE, Thomas, JJ. Range of motion at the wrist: A comparison study of four wrist extension orthoses and the free hand. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;56(2):180–184.

Cook, AC, Szabo, RM, Birkholz, SW, King, EF. Early mobilization following carpal tunnel release: A prospective randomized study. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1995;20B:228–230.

Courts, RB. Splinting for symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome during pregnancy. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1995;8:31–34.

Dell, PC, Dell, RB. Management of rheumatoid arthritis of the wrist. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1996;9(2):157–164.

Fess, EE, Gettle, KS, Philips, CA, Janson, JR. Hand Splinting Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby, 2005.

Gelberman, RH, Hergenroeder, PT, Hargens, AR, Lundborg, GN, Akeson, WH. The carpal tunnel syndrome: A study of carpal canal pressures. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American. 1981;63(3):380–383.

Gerritsen, AA, de Vet, HC, Scholten, RJ, Bertelsmann, FW, de Krom, MC, Bouter, LM. Splinting vs surgery in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(10):1245–1251.

Gerritsen, AA, Korthals-de Bos, IB, Laboyrie, PM, de Vet, HC, Scholten, RJ, Bouter. Splinting for carpal tunnel syndrome: prognostic indicators of success. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2003;74(9):1342–1344.

Graham, RG, Hudson, DA, Solomons, M, Singer, M. A prospective study to assess the outcome of steroid injections and wrist splinting for the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;113(2):550–556.

Hayes, EP, Carney, K, Mariatis Wolf, J, Smith, J, Akelman, E. Carpal tunnel syndrome. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:643–659.

Idler, RS. Helping the patient who has wrist or hand tenosynovitis. Part 2: Managing trigger finger, de Quervain’s disease. Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 1997;14(2):62–65. [68, 74-75].

Kasch, MC. Therapist’s evaluation and treatment of upper extremity cumulative-trauma disorders. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1005–1018.

Khan, KM, Cook, JL, Taunton, JE, Bonar, F. Overuse tendinosis, not tendonitis. Part 1: A new paradigm for a difficult clinical problem. Phys Sportsmed. 2000;28(5):38–48.

Kozin, SH, Michlovitz, SL. Traumatic arthritis and osteoarthritis of the wrist. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2000;13(2):124–135.

Kulick, RG. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 1996;27(2):345–354.

Kuo, MH, Leong, CP, Cheng, YF, Chang, HW. Static wrist position associated with least median nerve compression: Sonographic evaluation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2001;80(4):256–260.

Lankford, LL. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy. In: Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy. Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995:779–815.

Laseter, GF. Therapist’s management of distal radius fractures. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1136–1155.

Laseter, GF, Carter, PR. Management of distal radius fractures. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1996;9(2):114–128.

LaStayo, P. Ulnar wrist pain and impairment: A therapist’s algorithmic approach to the triangular fibrocartilage complex. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1156–1170.

McClure, P. Evidence-based practice: An example related to the use of splinting in a patient with carpal tunnel syndrome. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2003;16(3):256–263.

Melvin, JL. Rheumatic Disease in the Adult and Child: Occupational Therapy and Rehabilitation, Third Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1989.

Mersky, H, Bogduk, N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms, Second Edition. Seattle: IASP Press, 1994.

Messer, RS, Bankers, RM. Evaluating and treating common upper extremity nerve compression and tendonitis syndromes … without becoming cumulatively traumatized. Nurse Practitioner Forum. 1995;6(3):152–166.

Nordenskiold, U. Elastic wrist orthoses: Reduction of pain and increase in grip force for women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care and Research. 1990;3(3):158–162.

O’Connor, D, Mullett, H, Doyle, M, Mofidl, A, Kutty, S, O’Sullivan, M. Minimally displaced Colles’ fractures: A prospective randomized trial of treatment with a wrist splint or a plaster cast. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2003;28B(1):50–53.

Osterman, AL, Whitman, M, Porta, LD. Nonoperative carpal tunnel syndrome treatment. Hand Clinics. 2002;18(2):279–289.

Pagnotta, A, Baron, M, Korner-Bitensky, N. The effect of a static wrist orthosis on hand function in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology. 1998;25(5):879–885.

Palmer, AK, Werner, FW, Murphy, D, Glisson, R. Functional wrist motion: A biomechanical study. Journal of Hand Surgery American. 1985;10(1):39–46.

Philips, CA. Therapist’s management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In: Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy. Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995:1345–1350.

Phillips, D. FAQ: What is the difference between CRPS Type I and CRPS Type II? Retrieved on February 10, 2005, from http://www.rsdalert.co.uk/FAQ/witdifference.htm 2005.

Reiss, B. Therapist’s management of distal radial fractures. In: Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy. Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995:337–351.

Rozmaryn, LM, Dovelle, S, Rothman, ER, Gorman, K, Olvey, KM, Bartko, JJ. Nerve and tendon gliding exercises and the conservative management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1998;11(3):171–179.

Saidoff, DC, McDonough, AL. Critical Pathways in Therapeutic Intervention: Upper Extremity. St. Louis: Mosby, 1997.

Sailer, SM. The role of splinting and rehabilitation in the treatment of carpal and cubital tunnel syndromes. Hand Clinics. 1996;12(2):223–241.

Schultz-Johnson, K. Splinting the wrist: Mobilization and protection. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1996;9(2):165–176.

Siegel, DB, Kuzma, G, Eakins, D. Anatomic investigation the role of the lumbrical muscles in carpal tunnel syndrome. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1995;20A(5):860–863.

Skirven, T. Nerve injuries. In: Stanley BG, Tribuzi SM, eds. Concepts in Hand Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 1992:323–352.

Stein, CM, Svoren, B, Davis, P, Blankenberg, B. A prospective analysis of patients with rheumatic diseases attending referral hospitals in Harare, Zimbabwe. The Journal of Rheumatology. 1991;18(12):1841–1844.

Stern, EB. Grip strength and finger dexterity across five styles of commercial wrist orthoses. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1996;50(1):32–38.

Stern, EB, Sines, B, Teague, TR. Commercial wrist extensor orthoses: Hand function, comfort, and interference across five styles. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1994;7(4):237–244.

Stern, EB, Ytterberg, SR, Krug, HE, Larson, LM, Portoghese, CP, Kratz, WN, et al. Commercial wrist extensor orthoses: A descriptive study of use and preference in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care and Research. 1997;10(1):27–35.

Stern, EB, Ytterberg, SR, Krug, HE, Mahowald, ML. Finger dexterity and hand function: Effect of three commercial wrist extensor orthoses on patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care and Research. 1996;9(3):197–205.

Stern, EB, Ytterberg, SR, Krug, HE, Mullin, GT, Mahowald, ML. Immediate and short-term effects of three commercial wrist extensor orthoses on grip strength and function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care and Research. 1996;9(1):42–50.

Taylor-Mullins, PA. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy. In: Stanley BG, Tribuzi SM, eds. Concepts in Hand Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 1992:446–471.

Verdugo, RJ, Salinas, RS, Castillo, J, Cea, JG. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome (Cochrane Review). In In The Cochrane Library, Issue 2. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2004.

Walker, WC, Metzler, M, Cifu, DX, Swartz, Z. Neutral wrist splinting in carpal tunnel syndrome: A comparison of night-only versus full-time wear instructions. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2000;81(4):424–429.

Walsh, MT, Muntzer, E. Therapist’s management of complex regional pain syndrome (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1707–1724.

Weinstock, TB. Management of fractures of the distal radius: Therapists commentary. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1999;12(2):99–102.

Weiss, ND, Gordon, L, Bloom, T, So, Y, Rempel, DM. Position of the wrist associated with the lowest carpal-tunnel pressure: Implications for splint design. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American. 1995;77(11):1695–1699.

Williams, K. Carpal tunnel syndrome captivates American industry. Advance for Directors of Rehabilitation. 1992;12:13–18.