Hand Immobilization Splints

1 List diagnoses that benefit from resting hand splints (hand immobilization splints).

2 Describe the functional or mid-joint position of the wrist, thumb, and digits.

3 Describe the antideformity or intrinsic-plus position of the wrist, thumb, and digits.

4 List the purposes of a resting hand splint (hand immobilization splint).

5 Identify the components of a resting hand splint (hand immobilization splint).

6 Explain the precautions to consider when fabricating a resting hand splint (hand immobilization splint).

7 Determine a resting hand (hand immobilization) splint-wearing schedule for different diagnostic indications.

8 Describe splint-cleaning techniques that address infection control.

9 Apply knowledge about the application of the resting hand splint (hand immobilization splint) to a case study.

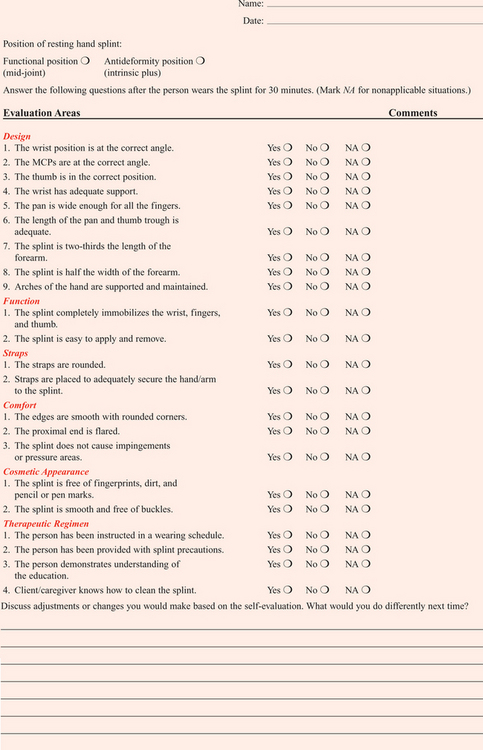

10 Use clinical judgment to evaluate a fabricated resting hand splint (hand immobilization splint).

Physicians commonly order resting hand splints, also known as hand immobilization splints [American Society of Hand Therapists 1992] or resting pan splints. A resting hand splint is a static splint that immobilizes the fingers and wrist. The thumb may or may not be immobilized by the splint. Therapists fabricate custom resting hand splints or purchase them commercially. Some of the commercially sold resting hand splints are prefabricated, premolded, and ready to wear.Table 9-1 outlines prefabricated splints for the wrist and hand. Others are sold as precut resting hand splint kits that include the precut thermoplastic material and strapping mechanism. Each of these splints has advantages and disadvantages.

Table 9-1

| THERAPEUTIC OBJECTIVE | DESCRIPTION |

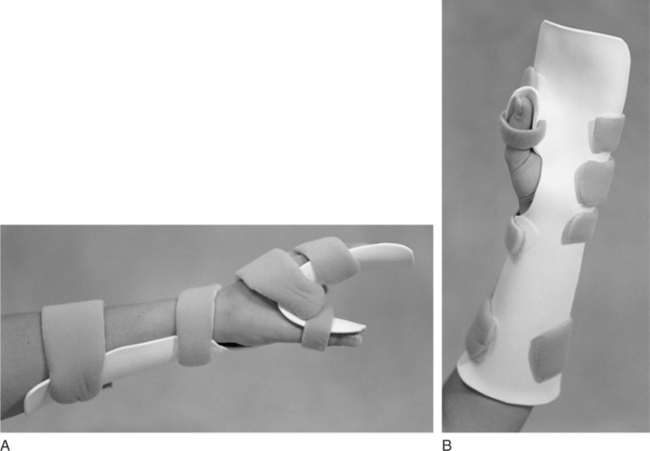

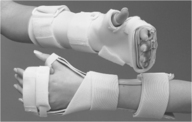

| Resting hand splints immobilize the wrist, thumb, and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints to provide rest and reduce inflammation. The proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints are free to move for functional tasks. | Similar to the resting hand splint design, splints can provide rest to the wrist, thumb, and MCP joints (Figure 9-1). Padding and strapping systems can help control deviation of wrist and MCPs. Splints are available in different sizes for the right and left hands. |

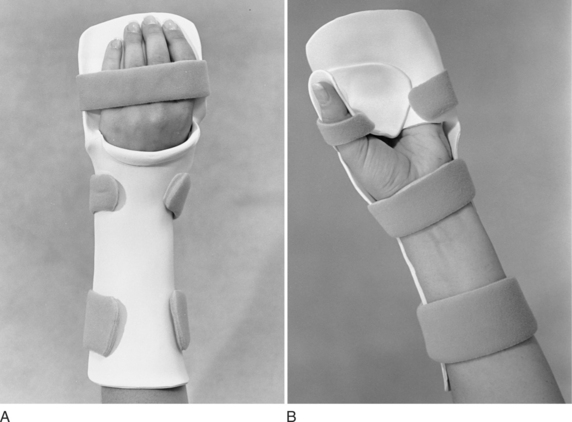

| Design to optimally position the hand in an intrinsic-plus position after a burn injury. | Burn resting hand splints typically position the wrist in 20 to 30 degrees of extension, the MCP joints in 60 to 80 degrees of flexion, the PIP and DIP joints in full extension, and the thumb midway between radial and palmar abduction (Figure 9-2). |

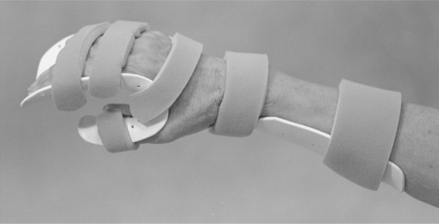

| Several splints are designed to reduce spasticity. | Ball splints implement a reflex-inhibiting posture by positioning the wrist in neutral (or slight extension) and the fingers in extension and abduction. Cone splints combine a hand cone and a forearm trough, which maintains the wrist in neutral, inhibits the long finger flexors, and maintains the web space (Figure 9-3). |

| A resting hand splint positioning the hand in a functional position is also advocated for spasticity (Figure 9-4). |

Premolded Hand Splints

Therapists can order premolded commercial splints according to hand size (i.e., small, medium, large, and extra large) for the right or left hand. An advantage of premade splints is their quick application (usually only straps require application). There is an advantage to ordering a premolded resting hand splint made from perforated material. The premolded splint has perforations only in the body of the splint. The edges are smooth because there are no perforations near the edges of the splint. However, if the perforated premolded or precut splint must be trimmed through the perforations a rough edge may result. Perforations at the edges of splints are undesirable because of the discomfort they often create.

Another disadvantage is that the commercial splint may not exactly fit each person. With premolded splints, the therapist has little control over positioning joints into particular therapeutic angles—which may be different from the angles already incorporated into the splint’s design. The splints must be ordered for application on the right or left extremity, whereas the precut splint is universal for the right or left hand.

Precut Splint Kits

A resting hand splint kit typically contains strapping materials and precut thermoplastic material in the shape of a resting hand splint. Kits are available according to hand size (i.e., small, medium, large, and extra large). An advantage of using a kit is the time the therapist saves by elimination of pattern making and cutting of thermoplastic material. Similar to premolded splints, precuts from perforated materials contain perforations in only the body of the splint. Precuts are interchangeable for right or left extremity application. The therapist has control over joint positioning. A disadvantage is that the pattern is not customized to the person. Therefore, the precut splint may require many adjustments to obtain a proper fit.

Customized Splints

A therapist can customize a resting hand splint by making a pattern and fabricating the splint from thermoplastic material. The advantage is an exact fit for the person, which increases the splint’s support and comfort. The therapist also has control over joint positioning. A disadvantage is that customization may require more of the therapist’s time to complete the splint and may be more costly. In addition, when a resting hand splint pattern is cut out of perforated thermoplastic material it is difficult to obtain smooth edges because of the likelihood of needing to cut through the perforations (which causes a rough edge). Commercially available products such as the Rolyan Aquaplast UltraThin Edging Material can be applied over the rough edges to help create a smooth-edged reinforcement on splints fabricated from Aquaplast materials [Sammons Preston Rolyan 2005].

Therapists must make informed decisions about whether they will fabricate or purchase a splint. Many products are advertised to save time and to be effective, but few studies compare splinting materials when used by therapists with the same level of experience [Lau 1998]. Lau [1998] compared the fabrication of a resting hand splint with use of a precut splint, the QuickCast (fiberglass material) with Ezeform thermoplastic material. The study employed second-year occupational therapy students as splintmakers and first-year occupational therapy students as their clients.

The clients responded to a questionnaire addressing comfort, weight, and aesthetics. The splintmakers also responded to a questionnaire asking about measuring fit, edges, strap application, aesthetics, safety, and ease of positioning. The analysis of timed trials revealed no significant difference in time required for fabricating the precut QuickCast and the Ezeform thermoplastic material. The thermoplastic material was rated safer than the fiberglass material. Because of the small sample, these results should be cautiously interpreted—and further studies are warranted.

Purpose of the Resting Hand Splint

The resting hand splint has three purposes: to immobilize, to position in functional alignment, and to retard further deformity [Malick 1972, Ziegler 1984]. When inflammation and pain are present in the hand, the joints and surrounding structures become swollen and result in improper hand alignment. The resting hand splint may retard further deformity for some persons. The therapist may provide a splint for a person with arthritis who has early signs of ulnar drift by placing the hand in a comfor table neutral position with the joints in mid-position. Rest through immobilization reduces symptoms. Joints that are receptive to proper positioning may allow for optimal maintenance of range of motion (ROM) [Ziegler 1984].

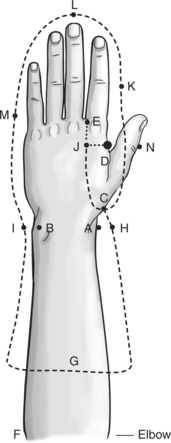

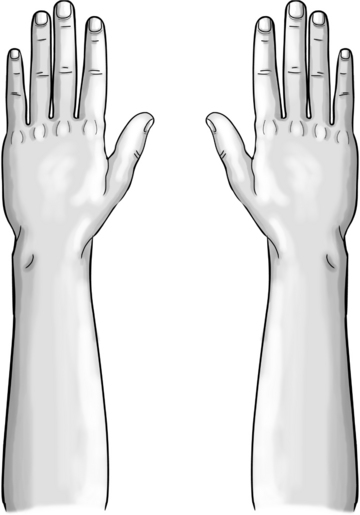

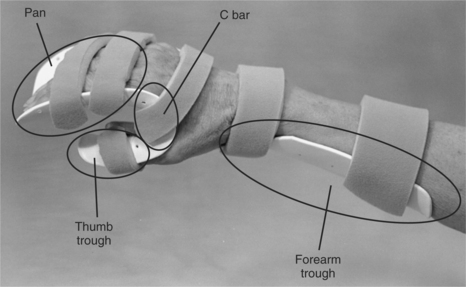

The therapist must know the splint’s components to make adjustments for a correct fit. Four main components comprise the resting hand splint: the forearm trough, the pan, the thumb trough, and the C bar (Figure 9-5) [Fess et al. 2005].

Figure 9-1 This splint is based on a resting hand splint design and is often used for individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. (Rolyan Arthritis Mitt splint; courtesy Rehabilitation Division of Smith & Nephew, Germantown, Wisconsin.)

Figure 9-2 This resting hand splint positions the hand in an antideformity position for individuals with hand burns. (Rolyan Burn splint; courtesy Rehabilitation Division of Smith & Nephew, Germantown, Wisconsin.)

Figure 9-3 This cone splint is often used to help manage tone abnormalities. (Preformed Anti-Spasticity Hand Splint; courtesy North Coast Medical, Inc., Morgan Hill, California.)

Figure 9-4 This resting hand splint is fabricated of soft materials and includes a dorsal forearm base design. (Progress Dorsal Anti-Spasticity splint; courtesy North Coast Medical, Inc., Morgan Hill, California.)

Figure 9-5 The components of a resting hand splint are the forearm trough, pan, thumb trough, and C bar.

Forearm troughs can be volarly or dorsally based. The volarly based forearm trough at the proximal portion of the splint supports the weight of the forearm. Dorsally based forearm troughs are located on the dorsum of the forearm. The therapist should apply biomechanical principles to make the trough about two-thirds the length of the forearm to distribute pressure of the hand and to allow elbow flexion when appropriate. The width should be one-half the circumference of the forearm. The proximal end of the trough should be flared or rolled to avoid a pressure area.

When a great amount of forearm support is desired, a volarly based forearm trough is the best design (Figure 9-6). When the volar surface of the forearm must be avoided because of sutures, sores, rashes, or intravenous needles, a dorsally based forearm trough design is frequently used (Figure 9-7). Dorsally based troughs can be a helpful design for applying a resting hand splint to a person with hypertonicity. The forearm trough can be used as a lever to extend the wrist in addition to extending the fingers.

The pan of the splint supports the fingers and the palm. The therapist conforms the pan to the arches of the hand, thus helping to maintain such hand functions as grasping and cupping motions. The pan should be wide enough to house the width of the index, middle, ring, and little fingers when they are in a slightly abducted position. The sides of the pan should be curved so that they measure approximately ½ inch in height. The curved sides add strength to the pan and ensure that the fingers do not slide radially or ulnarly off the sides of the pan. However, if the pan’s edges are too high the positioning strap bridges over the fingers and fails to anchor them properly.

The thumb trough supports the thumb and should extend approximately ½ inch beyond the end of the thumb. This extension allows the entire thumb to rest in the trough. The width and depth of the thumb trough should be one-half the circumference of the thumb, which typically should be in a palmarly abducted position. The therapist should attempt to position the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint in 40 to 45 degrees of palmar abduction [Tenney and Lisak 1986] and extend the thumb’s interphalangeal (IP) and metacarpal joints.

The C bar keeps the web space of the thumb positioned in palmar abduction. If the web space tightens, it inhibits cylindrical grasp and prevents the thumb from fully opposing the other digits. From the radial side of the splint, the thumb, the web space, and the digits should resemble a C (seeFigure 9-6).

Resting Hand Splint Positioning

Generally, two types of positioning are accomplished by a resting hand splint: a functional (mid-joint) position and an antideformity (intrinsic-plus) position. Diagnostic indication determines the general position used.

Functional Position

To rest the wrist and hand joints, the resting hand splint positions the hand in a functional or mid-joint position [Colditz 1995] (Figure 9-8). According to Lau [1998, p. 47], “The exact specifications of the functional position of the hand in a resting hand splint and the recommended joint positions vary.” One functional position that we suggest places the wrist in 20 to 30 degrees of extension, the thumb in 45 degrees of palmar abduction, the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints in 35 to 45 degrees of flexion, and all proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints in slight flexion.

Antideformity Position

The antideformity position is often used to place the hand in such a fashion as to maintain a tension/distraction of anatomic structures to avoid contracture and promote function. The antideformity position places the wrist in 30 to 40 degrees of extension, the thumb in 40 to 45 degrees of palmar abduction, the thumb IP joint in full extension, the MCPs at 70 to 90 degrees of flexion, and the PIPs and DIPs in full extension (Figure 9-9).

Diagnostic Indications

Several diagnostic categories may warrant the provision of a resting hand splint. Persons who require resting hand splints commonly have arthritis [Egan et al. 2001, Ouellette 1991]; postoperative Dupuytren’s contracture release [Prosser and Conolly 1996]; burn injuries to the hand, tendinitis, hemiplegic hand [Pizzi et al. 2005]; and tenosynovitis [Richard et al. 1994].

The resting hand splint maintains the hand in a functional or antideformity position, preserves a balance between extrinsic and intrinsic muscles, and provides localized rest to the tissues of the fingers, thumb, and wrist [Tenney and Lisak 1986]. Although hand immobilization splints are commonly used, a paucity of literature exists on their efficacy. Thus, it is a ripe area for future research. Therapists should consider the resting hand splint as a legitimate intervention for appropriate conditions despite the lack of evidence.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Therapists often provide resting hand splints for people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) during periods of acute inflammation and pain [Biese 2002, Ziegler 1984] and when these people do not use their hands for activities but require support and immobilization [Leonard 1990]. The biomechanical rationale for splinting acutely inflamed joints is to reduce pain by relieving stress and muscle spasms. However, it may not additionally prevent deformity [Biese 2002, Falconer 1991].

Typical joint placement for splinting a person with RA positions the wrist in 10 degrees of extension, the thumb in palmar abduction, the MCP joints in 35 to 45 degrees of flexion, and all the PIP and DIP joints in slight flexion [Melvin 1989]. For a person who has severe deformities or exacerbations from arthritis, the resting hand splint may also position the wrist at neutral or slight extension and 5 to 10 degrees of ulnar deviation [Geisser 1984, Marx 1992]. The thumb may be positioned midway between radial and palmar abduction to increase comfort. These joint angles are ideal. Therapists use clinical judgment to determine what joint angles are positions of comfort for splinting.

Note that wrist extension varies from the typical 30 degrees of extension. When the wrist is in slight extension, the carpal tunnel is open—as opposed to being narrowed, with 30 degrees of extension [Melvin 1989]. Finger spacers may be used in the pan to provide comfort and to prevent finger slippage in the splint [Melvin 1989]. Melvin [1989] cautions that finger spacers should not be used to passively correct ulnar deformity because of the risk for pressure areas. In addition, once the splint is removed there is no evidence that splint wear alters the deformity. However, it may prevent further deformity.

Acute Rheumatoid Arthritis

In persons who have RA, the use of splints for purposes of rest during pain and inflammation is controversial [Egan et al. 2001]. Periods of rest (three weeks or less) seem to be beneficial, but longer periods may cause loss of motion [Ouellette 1991]. Phillips [1995] recommended that persons with acute exacerbations wear splints full-time except for short periods of gentle ROM exercise and hygiene. Biese [2002] recommended that persons wear splints at night and part-time during the day. In addition, persons may find it beneficial to wear splints at night for several weeks after the acute inflammation subsides [Boozer 1993].

Chronic Rheumatoid Arthritis

When splinting a joint with chronic RA, the rationale is often based on biomechanical factors. According to Falconer [1991, p. 83], “Theoretically, by realigning and redistributing the damaging internal and external forces acting on the joint, the splint may help to prevent deformity __or improve joint function and functional use of the extremity.” Therapists who splint persons with chronic RA should be aware that prolonged use of a resting hand splint may also be harmful [Falconer 1991]. Studies on animals indicate that immobilization leads to decreased bone mass and strength, degeneration of cartilage, increase in joint capsule adhesions, weakness in tendon and ligament strength, and muscle atrophy [Falconer 1991].

In addition to splint intervention, persons with RA benefit from a combination of management of inflammation, education in joint protection, muscle strengthening, ROM maintenance, and pain reduction [Falconer 1991, Philips 1995]. Persons in late stages of RA who have skeletal collapse and deformity may benefit from the support of a splint during activities and at nighttime [Biese 2002, Callinan and Mathiowetz 1996].

Compliance of persons with RA in wearing resting hand splints has been estimated at approximately 50% [Feinberg 1992]. The degree to which a person’s compliance with a splint-wearing schedule affects the disease outcome is unknown. However, research indicates that some persons with RA who wore their splints only at times of symptom exacerbation did not demonstrate negative outcomes in relation to ROM or deformities [Feinberg 1992].

Hand Burns

For persons who have hand burns, therapists do not splint in the functional position. Instead, the therapist places the hand in the intrinsic-plus or antideformity position (seeFigure 9-9). Richard et al. [1994] conducted an in-depth literature review to find a standard dorsal hand burn splint design. The literature cited 43 splints to position the dorsally burned hand joints. Twenty-six of these splints were labeled as antideformity splints and 17 were identified as having a position of function. Thus, a wide range of designs exists for splinting dorsal hand burns [Richard et al. 1994].

Positioning may vary, depending on the surface of the hand that is burned. In general, the goal of splinting in the antideformity position is to prevent deformity by keeping structures whose length allows motion from shortening. These structures are the collateral ligaments of the MCPs, the volar plates of the IPs, and the wrist capsule and ligaments. The dorsal skin of the hand will maintain its length in the antideformity position. The thumb web space is also vulnerable to remodeling in a shortened form in the presence of inflammation and in a situation in which tension of the structure is absent.

The antideformity position for a palmar or circumferential burn places the wrist in 30 to 40 degrees of extension and 0 degrees (i.e., neutral) for a dorsal hand burn. For dorsal and volar burns, the therapist should flex the MCPs into 70 to 90 degrees, fully extend the PIP joints and DIP joints, and palmarly abduct the thumb to the index and middle fingers with the thumb IP joint extended [Salisbury et al. 1990]. After a burn injury, the thumb web space is at risk for developing an adduction contracture [Torres-Gray et al. 1996]. Therefore, palmar abduction of the thumb is the position of choice for the thumb CMC joint.

These joint angles are ideal. Some persons with burns may not initially tolerate these joint positions. When tolerable, the resting hand splint for the person who has hand burns can be adjusted more closely to the ideal position. Stages of burn recovery should be considered with splinting. The phases of recovery are emergent, acute, skin grafting, and rehabilitation.

Emergent Phase

The emergent phase is the first 48 to 72 postburn hours [deLinde and Miles 1995]. During this time frame, dorsal edema occurs and encourages wrist flexion, MCP joint hyperextension, and IP joint flexion [deLinde and Miles 1995]. Static splinting is initiated during the emergent phase to support the hand and maintain the length of vulnerable structures [deLinde and Miles 1995]. Positioning to counteract the forces of edema includes placing the wrist in 15 to 20 degrees of extension, the MCP joints in 60 to 70 degrees of flexion, and the PIP and DIP joints in full extension, with the thumb positioned midway between palmar and radial abduction and with the IP joint slightly flexed [deLinde and Miles 1995].

For children with dorsal hand burns, during the emergent phase the MCP joints may not need to be flexed as far as 60 to 70 degrees. deLinde and Knothe [2002] suggested that for children under the age of three therapists may not need to splint unless it is determined that the wrist requires support. If a child is age three or older, splinting should be considered. Young children who have burned hands may not need splints because the bulky dressings applied to the burned hand may provide adequate support.

A prefabricated resting hand splint in an antideformity position can be applied if a therapist cannot immediately construct a custom-made splint [deLinde and Miles 1995]. deLinde and Miles [1995] suggested that prefabricated splints may be appropriate for superficial burns with edema for the first three to five days. For full-thickness burns with excessive edema, custom-made splints are necessary [deLinde and Miles 1995]. A splint applied in the first 72 hours after a burn may not fit the person 2 hours after application because of the significant edema that usually follows a burn injury.

The therapist should closely monitor the person to make necessary adjustments to the splint. When fabricating a custom splint for a person with excessive edema, a therapist should avoid forcing wrist and hand joints into the ideal position and risking ischemia from damaged capillaries [deLinde and Miles 1995]. With edema reduction, serial splinting may be necessary as ROM is gained to splint toward the ideal position. Serial resting hand splints for persons with burns should conform to the person, rather than conforming the person to the splints [deLinde and Miles 1995].

Persons with hand burns have bandages covering burn sites. According to Richard et al. [1994, p. 370], “As layers of bandage around the hand increase, accommodation for the increased bandage thickness must be accounted for in the splint’s design, if it is to fit correctly.” To correct for bandage thickness on a resting hand splint, the bend corresponding to MCP flexion in the pan should be formed more proximally [Richard et al. 1994].

The initial splint provision for a person with hand burns should be applied with gauze rather than straps. This reduces the risk of compromising circulation. Splints on adults should be removed for exercise, hygiene, and appropriate functional tasks. For children, splints are removed for exercise, hygiene, and play activities [deLinde and Miles 1995].

Acute Phase

The acute phase begins after the emergent phase and lasts until wound closure [deLinde and Miles 1995]. Once edema begins to decrease, serial adjustments should be made to the splint. Therefore, it is advantageous to use thermoplastic material with memory properties. During the acute phase, therapists monitor the direction of deforming forces and make adjustments in the existing splint or design an additional splint to “orient the collagen being deposited during the early stages of wound healing as well as maintain joint alignment” [deLinde and Knothe 2002, p. 1502].

Healing wounds are also monitored, and splints are evaluated for fit and for correct donning and doffing. As ROM is improved, the person can decrease wearing of the splint during the day. If the person is unwilling or uncooperative in participating in self-care and supervised activities, the splint should be worn continuously to prevent contractures. It is important for persons to wear splints at nighttime.

Skin Graft Phase

Before a skin graft, it is crucial to obtain full ROM. After the skin graft, the site needs to be immobilized for about 5 days postoperatively [deLinde and Miles 1995]. Usually an antideformity position resting hand splint is appropriate. The splint may have to be applied in the operating room to ensure immobilization of the graft.

Rehabilitation Phase

The rehabilitation phase occurs after wound closure or graft adherence until scar maturation [deLinde and Miles 1995]. Throughout the person’s rehabilitation after a burn, splints may be donned over an extremity covered with a pressure garment. Splints may also be used in conjunction with materials that manage scar formation, including silicone gel sheeting or elastomer/elastomer putty inserts. During the rehabilitation phase, static and dynamic splinting may be needed. Plaster or synthetic material casting may also be considered [deLinde and Knothe 2002].

Dupuytren’s Disease

Dupuytren’s disease is characterized by the formation of finger flexion contracture(s) with a thickened band of palmar fascia [McFarlane 1995]. Nodules develop in the distal palmar crease, usually in line with the finger(s). Slowly the condition matures into a longitudinal cord that is readily distinguishable from a tendon [McFarlane 1995] (Figure 9-10). In addition, pain and decreased ROM are the primary symptoms that often lead to impaired functional performance [Kaye 1994]. Dupuytren’s contractures are common and often severe in persons of Northern European origin. However, this disorder is not uncommon in most ethnic groups [McFarlane 1995]. Epilepsy, diabetes mellitus, and chronic alcoholism are associated with Dupuytren’s contracture [Kaye 1994, McFarlane 1995, Swedler et al. 1995].

Figure 9-10 Dupuytren’s contractures of ring and little fingers. [From Fietti VG, Mackin EJ (1995). Open-palm technique in Dupuytren’s disease. In JM Hunter, EJ Mackin, AD Callahan (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 996.]

When a Dupuytren’s contracture is apparent, stretching or splinting joints in extension does not delay the progression of the contracture [McFarlane 1995]. Surgery is performed to correct joint contractures and to prevent recurrences of the disease. Although surgery does not cure the disease, it is often indicated in the presence of painful nodules; uncomfortable induration; and MCP, PIP, or DIP joint contractures [McFarlane and MacDermid 1995]. Surgical procedures to treat Dupuytren’s disease include fasciotomy, regional fasciectomy, and dermofasciectomy [McFarlane and MacDermid 1995, Prosser and Conolly 1996]. The surgical sites may be closed by Z-plasty or skin graft, or they may be left open to heal spontaneously. This open wound is frequently called the open palm technique. Other surgical techniques associated with a fasciectomy include a PIP or DIP joint release and amputation [Prosser and Conolly 1996].

The results of surgery may vary, depending on the affected joint [McFarlane 1995]. For example, the MCP joint has a single fascial cord that is relatively easy to release. The PIP joint has four fascial cords that are difficult to release. In addition, the soft tissue around the PIP joint may contract and pull the joint into flexion, and components of the extensor mechanism may adhere to surrounding structures. The PIP joint of the little finger is the most difficult to correct. Flexion contractures at the DIP joint are uncommon but are difficult to correct for the same reasons as the PIP joint contracture. Contractures of the web spaces may be present, limiting the motion of adjacent fingers. Web space contractures may also result in poor hygiene between the fingers.

Therapy and splinting begin immediately after surgery [McFarlane and MacDermid 1995]. Postoperative splinting may include a resting hand splint or a dorsal forearm-based static extension splint. Some therapists and physicians prefer a dorsal splint to reduce pressure over the surgical site. When a resting hand splint is used, the wrist is placed in a neutral or slightly flexed position [McFarlane and MacDermid 2002]. The MCP, PIP, and DIP joints are splinted in full extension. If the thumb is involved, it is incorporated into the splint. However, the uninvolved thumb usually does not need to be immobilized in the splint. Therefore, the splint will not have a thumb trough component (Figure 9-11). The thumb may be incorporated into the splint, particularly when the adjacent index finger has been released from a contracture.

Figure 9-11 A pattern for a resting hand splint after surgical release of Dupuytren’s contracture. Note that the thumb is not incorporated into the splint design.

Wearing schedules vary. The surgical procedure and the propensity of the person to lose ROM usually determine schedules. Persons should wear their splints until the wounds have healed, and longer if PIP joint contractures were corrected [McFarlane 1995]. Splints are removed for hygiene and exercise. Motion is initiated 1 to 2 days after surgery [McFarlane and MacDermid 1995], and the therapist focuses on regaining extension through the use of splinting and exercising. Exercise includes a tailored program of active and passive wrist, hand, and finger motions. McFarlane [1995] recommends that as long as composite finger flexion is possible when the splint is removed splint wear should continue. However, most persons eventually stop wearing their splints and accept some degree of PIP joint contracture. Removing the splint too soon without weaning the person from the splint typically results in loss of extension after surgery [McFarlane and McDermid 2002].

Therapists working with persons who undergo a Dupuytren’s release must be aware of possible complications. Complications include excessive inflammation, wound infection, abnormal scar formation, joint contractures, stiffness, pain, and complex regional pain syndrome [Prosser and Conolly 1996].

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy)

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic pain condition thought to be a result of impairment in the central or peripheral nerve systems. Outdated terms used to describe CRPS include reflex sympathetic dystrophy, causalgia, and shoulder-hand syndrome. Typical symptoms include [Koman et al. 2002] the following:

• Pain: Out of proportional intensity to the injury, burning, and skin sensitivity

• Skin color changes: Blotchy, purple, pale, or red

• Skin temperature changes: Warmer or cooler compared to contralateral side

• Skin texture changes: Thin, shiny, and sometimes excessively sweaty

There are two types of CRPS. CRPS I is usually triggered by tissue injury. The term applies to all persons with the symptoms listed previously, but with no underlying peripheral nerve injury. CRPS II is associated with the symptoms in the presence of a peripheral nerve injury.

The goal of rehabilitation for persons with CRPS is to eliminate one of the three etiologic factors: pain, diathesis, and abnormal sympathetic reflex [Lankford 1995]. This is accomplished by minimizing ROM and strength losses, managing edema, and providing pain management so that the therapist is able to maximize function and provide activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living training for independence. The physician may be able to intervene with medications and nerve blocks.

As part of a comprehensive therapy regimen for CRPS, a resting hand splint may initially provide rest to the hand, reduce pain, and relieve muscle spasm [Lankford 1995]. Splinting during the presence of CRPS should be of a low force that does not exacerbate the pain or irritate the tissues [Walsh and Muntzer 2002]. Walsh and Muntzer [2002] recommend that the resting hand splint position for the person be in 20 degrees of wrist extension, palmar abduction of the thumb, 70 degrees of MCP joint flexion, and 0 to 10 degrees of PIP joint extension. This is an ideal position, which persons with CRPS may not tolerate. Above all, therapists working with persons who have CRPS should avoid causing pain. Therefore, they should be splinted in a position of comfort. Splints other than a resting hand splint may also be appropriate for this diagnostic population. (See Chapter 7 for a discussion of wrist splinting for CRPS.)

Hand Crush Injury

To splint a crushed hand the therapist can position the wrist in 0 to 30 degrees of extension, the MCPs in 60 to 80 degrees of flexion, the PIPs and DIPs in full extension, and the thumb in palmar abduction and extension [Colditz 1995]. Splinting a crushed hand into this position provides rest to the injured tissue and decreases pain, edema, and inflammation [Stanley and Tribuzi 1992].

Other Conditions

Resting hand splints are appropriate “for protecting tendons, joints, capsular and ligamentous structures” [Leonard 1990, p. 909]. These diagnoses usually require the expertise of experienced therapists and may warrant different splints for daytime wear and resting hand splints for nighttime use. (See Chapter 13 for splint interventions for nerve injuries.)

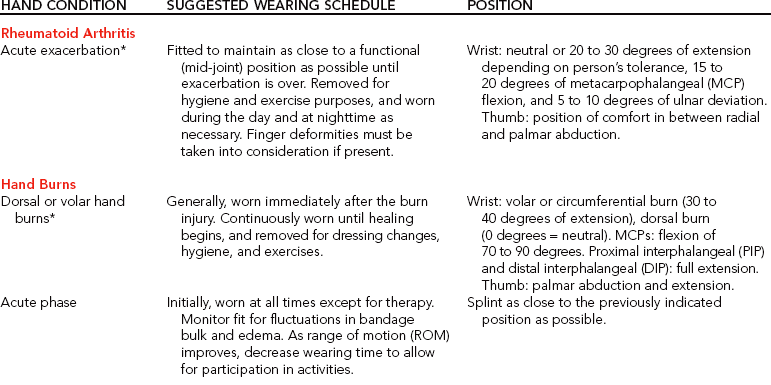

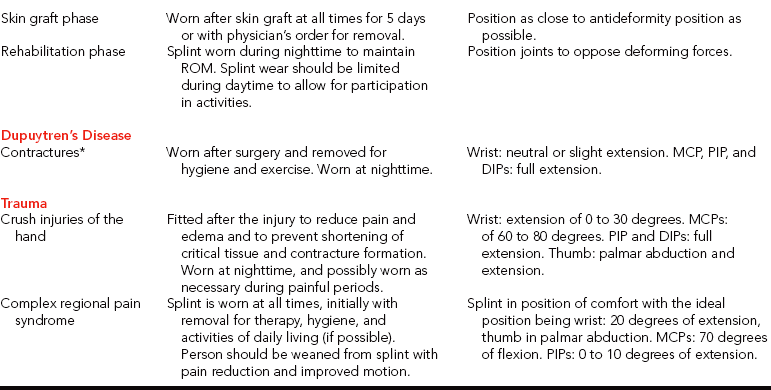

Therapists sometimes use resting hand splints to treat persons who experience a stroke and who are at risk for developing contractures because of increased tone or spasticity [Malick 1972]. (See Chapter 14 for more information on splinting an extremity that has increased tone or spasticity.)Table 9-2 lists common hand conditions that may require a resting hand splint and includes information regarding suggested hand positioning and splint-wearing schedules. Beginning therapists should remember that these are general guidelines and physicians and experienced therapists may have their own specific protocols for splint positioning and wearing.

Table 9-2

Conditions That Require a Resting Hand Splint

*Diagnosis may require additional types of splinting.

Splint-Wearing Schedule

Wearing schedules for resting hand splints vary depending on the diagnostic condition, splint purpose, and physician order (seeTable 9-2). Persons with RA often wear resting hand splints at night. A person who has RA may also wear a resting hand splint during the day for additional rest but should remove the splint at least once each day for hygiene and appropriate exercises. A person who has bilateral hand splints may choose to wear alternate splints each night.

Persons commonly wear resting hand splints during the healing stages of burns. After wounds heal, persons may wear day splints with pressure garments or elastomer molds to increase ROM and to control scarring. In addition to daytime splints, it is important for the person to wear a resting hand splint at night to maintain maximum elongation of the healing skin and provide rest and functional alignment.

After a surgical release of a Dupuytren’s contracture, the person should wear the splint continuously during both day and night—with removal for hygiene and exercise. The splint should be worn until the wounds have completely healed, and should be worn longer if there has been a PIP contracture release. As the risk of losing ROM dissipates, the person may be weaned from the splint until its use is finally discontinued.

Resting hand splints provided to persons with CRPS should initially be worn at all times, with removal for therapy, hygiene, and (if possible) ADLs. As pain reduction and motion improvement occur, the amount of time the person wears the splint is decreased.

Fabrication of a Resting Hand Splint

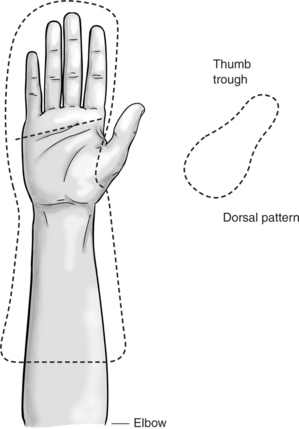

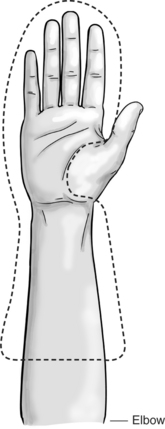

The first step in the fabrication of a resting hand splint is drawing a pattern similar to that shown inFigure 9-12. Beginning splintmakers may learn to fabricate splint patterns by following detailed written instructions and by looking at pictures of splint patterns. As beginners gain more experience, they will be able to easily draw splint patterns without having to follow detailed instructions or pictures. The following are the detailed steps for fabricating a resting hand splint.

1. Place the person’s hand flat and palm down, with the fingers slightly abducted, on a paper towel. Trace the outline of the upper extremity from one side of the elbow to the other.

2. While the person’s hand is on the piece of paper, mark the following areas: (1) the radial styloid A and the ulnar styloid B, (2) the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb C, (3) the apex of the thumb web space D, (4) the web space between the second and third digits E, and (5) the olecranon process of the elbow F.

3. Remove the person’s hand from the piece of paper. Draw a line across, indicating two-thirds of the length of the forearm. Then label this line G. After doing this, extend line G about 1 to 1-½ inches beyond each side of the outline of the arm. Then mark an H about 1 inch from the outline to the radial side of A. Mark an I about 1 inch from the outline to the ulnar side of B.

4. Draw a dotted vertical line from the web space of the second and third digits (E) proximally down the palm about 3 inches. Draw a dotted horizontal line from the bottom of the thumb web space (D) toward the ulnar side of the hand until the line intersects the dotted vertical line. Mark a J at the intersection of these two dotted lines. Mark an N about 1 inch from the outline to the radial side of D.

5. Draw a solid vertical line from J toward the wrist. Then curve this line so that it meets C on the pattern (seeFigure 9-12). This part of the pattern is known as the thumb trough. After reaching C, curve the line upward until it reaches halfway between N and D.

6. Mark a K about 1 inch to the radial side of the index finger’s PIP joint. Mark an L 1 inch from the top of the outline of the middle finger. Mark an M about 1 inch to the ulnar side of the little finger’s PIP joint.

7. Draw the line that ends to the side of N through K and extend the line upward and around the corner through L. From L, round the corner to connect the line with M and then pass it through I. Continue drawing the line and connect it with the end of G. Connect the radial end of G to pass through H. From H, extend the line toward C. Curve the line so that it connects to C (seeFigure 9-12).

8. Cut out the pattern. Cut the solid lines of the thumb trough also. Do not cut the dotted lines.

9. Place the pattern on the person in the appropriate joint placement. Check the length of the pan, thumb trough, and forearm trough. Assess the fit of the C bar by forming the paper towel in the thumb web space. Make necessary adjustments (e.g., additions, deletions) on the pattern.

10. With a pencil, trace the splint pattern onto the sheet of thermoplastic material.

11. Heat the thermoplastic material.

12. Cut the pattern out of the thermoplastic material and reheat. Before placing the material on the person, think about the strategy you will employ during the molding process.

13. Instruct the person to rest the elbow on the table. The arm should be vertical and the hand relaxed. Although some thermoplastic materials in the vertical position may stretch during the molding process, the vertical position allows the best control of the wrist position. Mold the plastic form onto the person’s hand and make necessary adjustments. Cold water or vapocoolant spray can be used to hasten the cooling time. However, this is not appropriate for persons with open wounds such as burns.

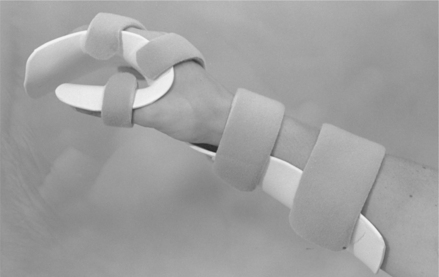

14. Add straps to the pan, the thumb trough, and the forearm trough (Figure 9-13). One pan strap is located across the PIP joints; the other is just proximal to the MCP joints. The strap across the thumb lies proximal to the IP joint. The forearm has two straps: one courses across the wrist and one is located across the proximal forearm trough. (See also Laboratory Exercise 9-1.)

Technical Tips for a Proper Fit

• For persons who have fleshier forearms, the splint pattern requires an allowance of more than 1 inch on each side. To be accurate, the therapist could measure the circumference of the person’s forearm at several locations and make the splint pattern corresponding to the location of the measurements one-half of these measurements.

• Check pattern carefully to determine fit, particularly the length of the pan, thumb trough, and forearm trough and the conformity of the C bar. Moistening the paper towel pattern allows detailed assessment of pattern fit.

• Select a thermoplastic material with strength or rigidity. Avoid materials with excessive stretch characteristics. The splint material must be strong enough to support the entire hand, wrist, and forearm. A thermoplastic material with memory can be reheated several times and is beneficial if the splint requires serial adjustments. To make a splint more lightweight, select a thermoplastic material that is perforated or is thinner than 1/8 inch when splinting to manage conditions such as RA.

• Make sure the splint supports the wrist area well. If the thumb trough is cut beyond the radial styloid, the wrist support is compromised.

• Measure the person’s joints with a goniometer to ensure a correct therapeutic position before splinting. Be cautious of splinting the wrist in too much ulnar or radial deviation.

• When applying the straps, be sure the hand and forearm are securely fit into the splint. For maximal joint control, place straps across the PIPs, thumb IP, palm, wrist, and proximal forearm. Additional straps may be necessary, particularly for persons who have hypertonicity.

• Contour the splint’s pan to the hand to preserve the hand’s arches. The pan should be wide enough to comfortably support the width of the index, middle, ring, and little fingers.

• Make sure the C bar conforms to the thumb web space (Figure 9-14). The therapist may find it helpful to stretch the edge of the C bar and then conform it to the web space. Cut any extra material from the C bar as necessary.

• Verify that the thumb trough is long enough and wide enough. Stretch or trim the thumb trough as necessary.

• For fabrication of a dorsally based resting hand splint, the pattern remains the same—with the addition of a slit cut at the level of the MCP joints in the pan portion of the splint. The slit should begin and end about 1 inch from the ulnar and radial sides of the pan, as shown inFigure 9-15. When the splint is placed on the person, the person puts the hand through the slit in such a way so that the fingers rest on top of the pan portion and the forearm trough rests on the dorsal surface of the forearm. The edges of the slit require rolling or slight flaring away from the surface of the skin to prevent pressure areas. In addition, the thumb trough is a separate piece and must be attached to the pan and wrist portion of the splint. Thus, material with bonding or self-adherence characteristics is important. (See also Laboratory Exercise 9-2.)

Precautions for a Resting Hand Splint

The therapist should take precautions when applying a splint to a person. If the diagnosis permits, the therapist should instruct the person to remove the splint for an ROM schedule to prevent stiffness and control edema.

• The therapist should monitor the person for pressure areas from the splint. With burns and other conditions resulting in open wounds, the therapist should make adjustments frequently as bandage bulk changes.

• To prevent infection, the therapist must teach the person or caregiver to clean the splint when open wounds with exudate are present. After removing the splint, the person or caregiver can clean it with warm soapy water, hydrogen peroxide, or rubbing alcohol and dry it with a clean cloth (Box 9-1). Rubbing alcohol may be the most effective for removing skin cells, perspiration, dirt, and exudate.

• For a resting hand splint for a person in an intensive care unit (ICU), supplies and tools should be kept as sterile as possible. Careful planning about supply needs before going into the unit helps prevent repetitious trips. The splintmaker may enlist the help of a second person, aide, or therapist to assist with the splinting process. The therapist working in a sterile environment should follow the facility’s protocol on universal precautions and body substance procedures. Prepackaged sterilized equipment can be used for splinting. Alternatively, any equipment that can withstand the heat from an autoclave can be used.

• Depending on facility regulations, various actions may be taken to ensure optimal wear and care of a splint. The therapist should consider hanging a wearing schedule in the person’s room. This precaution is especially helpful if others are involved in applying and removing the splint. A photograph of the person wearing the splint posted in the room or in the person’s care plan in the chart may help with correct splint application. The therapist should inform nursing staff members of the wearing schedule and care instruction.

• After splinting a person in the ICU, the therapist should follow up at least once after the splint’s application regarding the fit and the person’s tolerance of the splint. Splints on persons with burns require frequent adjustments. As the person recovers, the splint design may change several times.

• A person who has RA may benefit from a splint made from thinner thermoplastic (less than 1/8 inch). This type of splint reduces the weight over affected joints [Melvin 1982].

1. What are four common diagnostic conditions in which a therapist may provide a resting hand splint for intervention?

2. In what position should the therapist place the wrist, MCPs, and thumb for a functional resting hand splint?

3. For a resting hand splint, in what joint positions should a person with RA be placed?

4. When might a therapist choose to use a dorsally based resting hand splint rather than a volarly based splint?

5. In what position should the therapist place the wrist, MCPs, and thumb for an antideformity resting hand splint?

6. What are the three purposes for using a resting hand splint?

7. What are the four main components of a resting hand splint?

8. Which equipment must be sterile to make a resting hand splint in a burn unit?

References

American Society of Hand Therapists. Splint Classification System. Garner, NC: American Society of Hand Therapists, 1992.

Biese, J. Therapist’s evaluation and conservative management of rheumatoid arthritis in the hand and wrist. In Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fifth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Boozer, J. Splinting the arthritic hand. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1993;6(1):46.

Callinan, NJ, Mathiowetz, V. Soft versus hard resting hand splints in rheumatoid arthritis: Pain relief, preference and compliance. AJOT. 1996;50:347–353.

deLinde, LG, Knothe, B. Therapist’s management of the burned hand. In Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fifth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

deLinde, LG, Miles, WK. Remodeling of scar tissue in the burned hand. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Egan, M, Brosseau, L, Farmer, M, Ouimet, M, Rees, S, Tugwell, P, et al, Splints and orthoses for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, Art. No. CD004018 2001. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004018.

Falconer, J. Hand splinting in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1991;4(2):81–86.

Feinberg, J. Effect of the arthritis health professional on compliance with use of resting hand splints by persons with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1992;5(1):17–23.

Fess, EE, Philips, CA. Hand Splinting Principles and Methods, Second Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, 1987.

Geisser, RW. Splinting the rheumatoid arthritic hand. In: Ziegler EM, ed. Current Concepts in Orthotics: A Diagnosis-related Approach to Splinting. Germantown, WI: Rolyan Medical Products, 1984.

Kaye, R. Watching for and managing musculoskeletal problems in diabetes. The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 1994;11(9):25–37.

Koman, LA, Smith, BP, Smith, TL. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (complex regional pain syndromes- types 1 and 2). In Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fifth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Lankford, LL. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Lau, C. Comparison study of QuickCast versus a traditional thermoplastic in the fabrication of a resting hand splint. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1998;11:45–48.

Leonard, J. Joint protection for inflammatory disorders. In Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Third Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1990.

McFarlane, RM. The current status of Dupuytren’s disease. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1995;8(3):181–184.

McFarlane, RM, MacDermid, JC. Dupuytren’s disease. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

McFarlane, RM, MacDermid, JC. Dupuytren’s disease. In Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fifth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Malick, MH. Manual on Static Hand Splinting. Pittsburgh: Hamarville Rehabilitation Center, 1972.

Marx, H. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Stanley BG, Tribuzi SM, eds. Concepts in Hand Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1992.

Melvin, JL. Rheumatic Disease: Occupational Therapy and Rehabilitation, Second Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1982.

Melvin, JL. Rheumatic Disease in the Adult and Child: Occupational Therapy and Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1989.

Ouellette, EA. The rheumatoid hand: Orthotics as preventative. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1991;21:65–71.

Philips, CA. Therapist’s management of persons with rheumatoid arthritis. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Pizzi, A, Carlucci, G, Falsini, C, Verdesca, S, Grippo, A. Application of a volar static splinit in poststroke spasticity of the upper limb. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005;86:1855–1859.

Prosser, R, Conolly, WB. Complications following surgical treatment for Dupuytren’s contracture. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1996;9(4):344–348.

Richard, R, Schall, S, Staley, M, Miller, S. Hand burn splint fabrication: Correction for bandage thickness. Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation. 1994;15(4):369–371.

Richard, R, Staley, M, Daugherty, MB, Miller, SF, Warden, GD. The wide variety of designs for dorsal hand burn splints. Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation. 1994;15(3):275–280.

Salisbury, RE, Reeves, SU, Wright, P. Acute care and rehabilitation of the burned hand. In: Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy. Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1990:831–840.

Sammons Preston Rolyan (SPR). Hand Rehab Catalog. Bolingbrook, IL: Sammons Preston Rolyan, 2005.

Stanley, BG, Tribuzi, SM. Concepts in Hand Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1992.

Swedler, WI, Baak, S, Lazarevic, MB, Skosey, JL. Rheumatic changes in diabetes: Shoulder, arm, and hand. The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 1995;12(8):45–52.

Tenney, CG, Lisak, JM. Atlas of Hand Splinting. Boston: Little, Brown & Co, 1986.

Torres-Gray, D, Johnson, J, Mlakar, J. Rehabilitation of the burned hand: Questionnaire results. Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation. 1996;17(2):161–168.

Walsh, MT, Muntzer, E. Therapist’s management of complex regional pain syndrome (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). In Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fifth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Ziegler, EM. Current Concepts in Orthotics: A Diagnostic-related Approach to Splinting. Germantown, WI: Rolyan Medical Products, 1984.