Splinting for Nerve Injuries

1 Identify the components of a peripheral nerve.

2 Describe a peripheral nerve’s response to injury and repair.

3 List the operative procedures used for nerve repair.

4 List the three purposes for splinting nerve palsies.

5 Describe the nerve injury classification.

6 Identify the locations for low and high peripheral nerve lesions.

7 Explain causes of radial, ulnar, and median nerve lesions.

8 Review the sensory and motor distributions of the radial, median, and ulnar nerves.

9 Explain the functional effects of radial, ulnar, and median nerve lesions.

10 Identify the splinting approaches and rationale for radial, ulnar, and median nerve injuries.

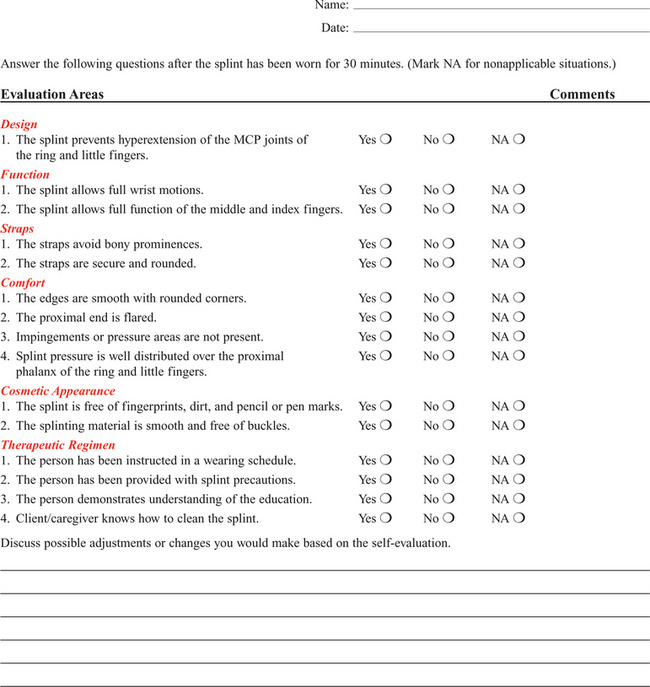

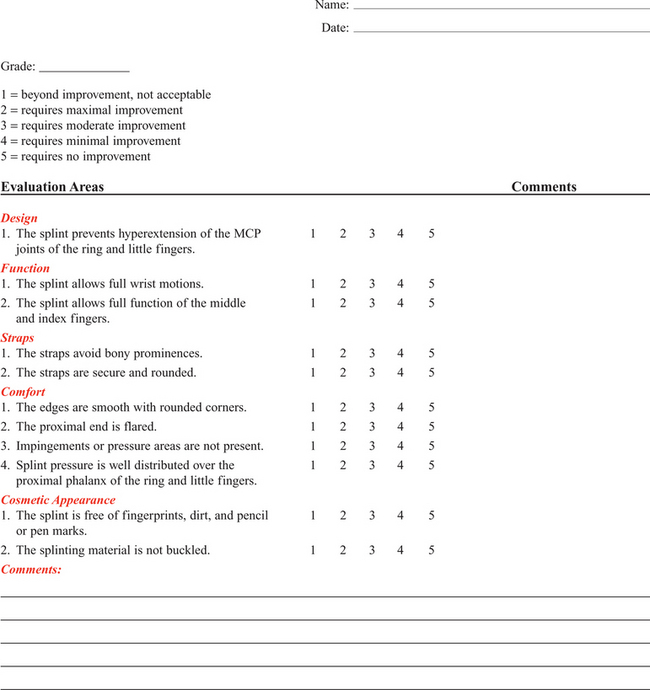

11 Use clinical judgment to evaluate a problematic splint for a nerve lesion.

12 Use clinical judgment to evaluate a fabricated hand-based ulnar nerve splint.

13 Apply documentation skills to a case study.

14 Understand the importance of evidence-based practice with provision of splints for nerve conditions.

Splint interventions for nerve lesions require that therapists have a thorough knowledge of static (immobilization) and dynamic (mobilization) splinting principles and sound critical-thinking skills. Comprehension of kinesiology, physiology, and anatomy is paramount to understanding the motor, sensory, and vasomotor implications of a nerve injury. Competence in manual muscle-testing skills is also necessary to evaluate the muscles as nerves recover from injuries [Colditz 2002]. This chapter includes information on peripheral nerve anatomy; nerve injury classifications; nerve repair; and types, effects, and treatments for radial, ulnar, and median nerve injuries.

Peripheral Nerve Anatomy

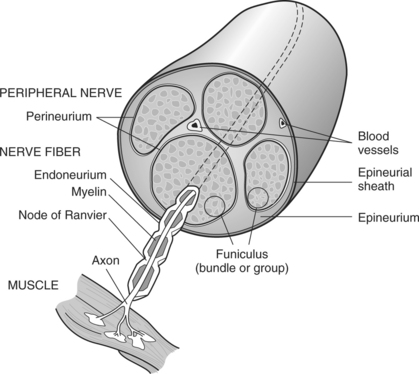

As shown inFigure 13-1, a peripheral nerve consists of the epineurium, perineurium, endoneurium, fascicles, axons, and blood vessels [Jebson and Gaul 1998]. The epineurium is made of loose collagenous connective tissue. There are external and internal types of epineurium. The external epineurium contains blood vessels. The internal epineurium protects the fascicles from pressure and allows gliding of fascicles. The amount of epineurium varies among persons, nerve types, and along each individual nerve. The perineurium surrounds fascicles, and the endoneurium surrounds the axons. A fascicle consists of a group of axons that are surrounded by endoneurium and are covered by a sheath of perineurium. An individual fascicle contains a mix of myelinated and unmyelinated fibers. The myelin sheath encapsulates the axon. Myelin is a lipoprotein, which allows for conduction of fast impulses. Each nerve contains a varied number and size of fascicles.

Nerves are at risk for injury when laceration, avulsion, stretch, crush, compression, or contusion occurs [Callahan 1984]. In addition, peripheral nerves can be attacked by viruses, bacteria, or the body’s immune system [Greene and Roberts 2005]. Often bone, tendon, ligament, vessel, and soft-tissue injuries accompany nerve injuries.

Nerve Injury Classification

Nerve injuries are categorized by the extent of damage to the axon and sheath [Skirven 1992]. Nerve compression lesions often contribute to peripheral neuropathies. When a specific portion of a peripheral nerve is compressed, the peripheral axons within the nerve sustain the greatest injury. Initial changes occur in the blood/nerve barrier followed by subperineural edema. This results in a thickening of the internal and external perineurium [Novak and Mackinnon 1998]. As the compression worsens, the motor, proprioceptive, light touch, and vibratory sensory axons become more vulnerable [Spinner 1990]. All the fibers may be paralyzed after enduring severe and prolonged compression. Seddon [1943] originally described three levels of nerve injury: (1) neurapraxia, (2) axonotmesis, and (3) neurotmesis (Figure 13-2). Later in 1968, Sunderland extended the classification to five levels, which are termed as first-through fifth-degree injuries.

Figure 13-2 The three classifications of nerve injuries are (1) neurapraxia, (2) axonotmesis, and (3) neurotmesis.

First-degree Injury

A first-degree injury involves the demylination of the nerve, which temporarily blocks conduction [Boscheinen-Morrin et al. 1987, Novak and Mackinnon, 2005]. The prognosis for persons with neurapraxia is extremely good; recovery is usually spontaneous within three months [Spinner 1990].

Second-degree Injury

When a second-degree injury occurs, the axon is severed and the sheath remains intact. Wallerian degeneration occurs when a nerve is completely severed or the axon and myelin sheath are damaged, and the endoneurial tube remains intact. The segment of axon and the motor and sensory end receptors distal to the lesion suffer ischemia and begin to degenerate 3 to 5 days after the injury [Jebson and Gaul 1998]. The intact endoneurial tube allows for potential regrowth for the proximal part of the nerve to reattach to the distal portion of the nerve. With the ideal scenario the rate of regeneration is approximately 1 inch per month. Complete recovery usually occurs if regeneration happens in a timely manner before muscle degeneration [Novak and Mackinnon 2005].

Third-degree Injury

A third-degree injury is a more severe form of a second-degree injury with the addition of the “continuity of the endoneurial tube destroyed from a disorganization of the internal structures of the nerve bundles” [Sunderland 1968, p. 132]. Recovery is more complicated with possible delayed or incomplete axonal growth [Sunderland 1968]. Because fibers are often mismatched, clients benefit from motor and sensory reeducation [Novak and Mackinnon 2005].

Fourth-degree Injury

At this level of injury “the involved segment is ultimately converted into a tangled strand of connective tissue, Schwann cells, and regenerating axons which can be enlarged to form a neuroma” [Sunderland 1968, p. 135]. The effects are more severe than a third-degree injury with increased neuronal degeneration, misdirected axons, and less axon survival [Sunderland 1968]. Surgical intervention is necessary to remove the neuroma (a tumor of nerve fibers and cells).

Fifth-degree Injury

A fifth-degree injury results in partial or complete severance of the axon and the sheath with loss of motor, sensory, and sympathetic function [Sunderland 1968]. Without the directional guidance from an intact endoneurial tube, misdirected axon growth may lead to a complicated recovery. Microsurgery is required to reestablish axon direction. Occasionally, grafting is necessary if the gap is too large for approximation of the two nerve ends [Spinner 1990].

Nerve Repair

Peripheral nerve lesions often occur to the median, radial, and ulnar nerves. The location of the lesion determines the impairment of sudomotor, vasomotor, muscular, sensory, and functional involvement [Boscheinen-Morrin et al. 1987]. Sometimes nerves can be compressed at more than one site, which is called double crush injury [Upton and McComas 1973, Rehak 2001]. Therefore, it is important to be aware of key diagnostic procedures to determine the extent of compression.

Operative Procedures for Nerve Repair

There are four procedures used to surgically repair nerves: (1) decompression, (2) repair, (3) neurolysis, and (4) grafting [Saidoff and McDonough 1997]. Nerve decompression is the most common operation performed on nerves. An example of surgical decompression is the transection of the transverse carpal ligament to decompress the median nerve (this is also known as a carpal tunnel release).

Surgical nerve repairs involve microsurgical sutures to repair the epineurium. Surgical nerve repairs are classified as primary, delayed primary, or secondary [Jebson and Gaul 1998]. A primary repair occurs within hours of the injury. A delayed primary repair occurs within 5 to 7 days after the injury. Any surgical repair performed beyond seven days is a secondary repair.

Neurolysis is a procedure performed on a nerve that has become encapsulated in dense scar tissue, which compresses the nerve to surrounding soft tissues and prevents it from gliding. When the client attempts to move in a way that would normally glide the nerve, it instead stretches, affecting circulation and chemical balance. Scars may physically interfere with the axon regeneration.

Nerve grafting is necessary when there is a large gap in a nerve and end-to-end nerve repair is not possible. An autograft donated by a cutaneous nerve, such as the sural nerve, can fill the gap. Although the outcome from a nerve graft is somewhat unreliable, occasionally it is the only option for repair.

Purposes for Splinting Nerve Injuries

The three purposes for splinting an extremity that has a nerve injury are protection, prevention, and assistance with function [Arsham 1984]. If a nerve has undergone surgical repair, the physician may initially order application of a cast or splint to place the hand, wrist, or elbow in a protective position, thus reducing the amount of tension on the repaired nerve. Avoiding tension on a repaired nerve is extremely important because results of nerve repairs are directly related to the amount of tension across the repair site [Skirven and Callahan 2002].

Prevention of contractures is important because nerve lesions result in various degrees of muscle denervation. For example, a short opponens splint prevents a contracture of the thumb web space after a median nerve injury [Fess et al. 2005]. Sometimes a client does not seek immediate medical attention after the occurrence of a nerve injury, and a resulting contracture develops and requires splint intervention. For example, if a person presents with a clawhand deformity as a result of an ulnar nerve injury the therapist may choose to fabricate a mobilizing ulnar gutter splint to remodel the soft tissues to increase passive extension of the ring and little fingers’ proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints [Callahan 1984]. Once metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and PIP stiffness have occurred treatment should focus on regaining maximum passive range of motion (PROM). After normal PROM is reestablished, splinting interventions for the muscle imbalance become an option [Fess 1986].

Often, function after a nerve injury can be enhanced by splint intervention. For example, a client may be better able to grasp and release objects after a radial nerve injury if he or she is wearing an elastic tension MCP and wrist extension splint. This splint assists the MCP joints to extend to open the hand for grasp release. Without the splint, the wrist and MCP joints are unable to extend, and difficulty with grasp and grasp release activities results.

Upper Extremity Compression Neuropathies

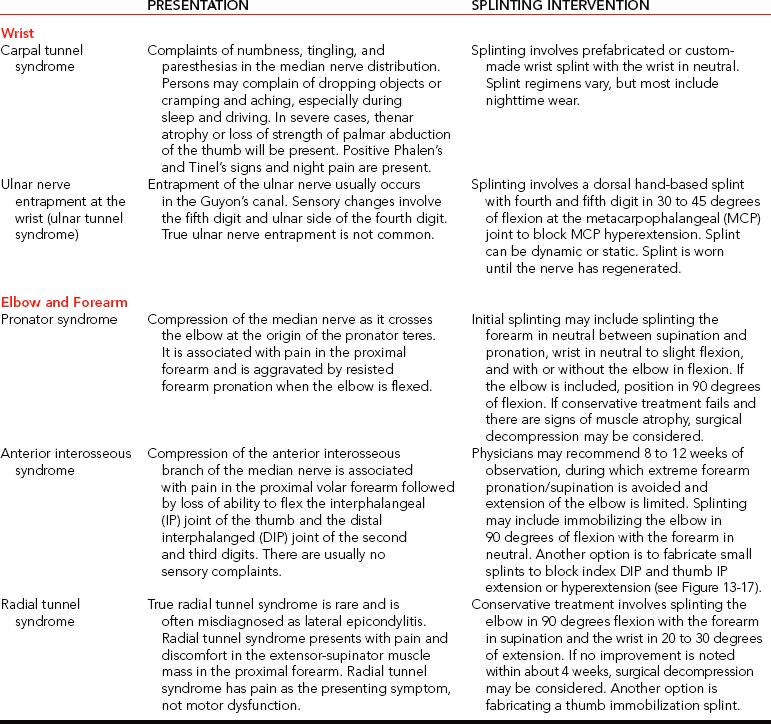

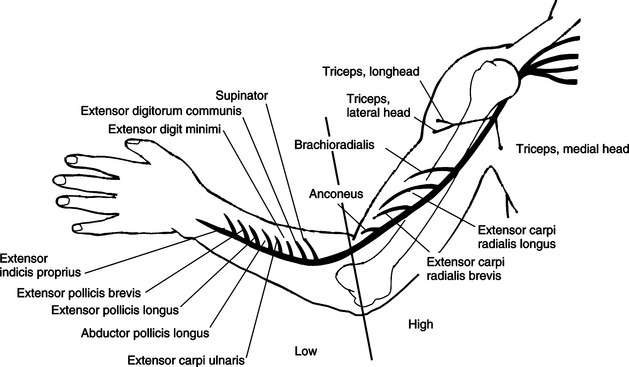

Cumulative trauma disorder (CTD) is not a medical diagnosis but an etiologic label for a range of disorders [Melhorn 1998]. The cause of CTD is not solely work activities. Social activities, activities of daily living (ADL), and leisure pursuits may also enhance the development and exacerbation of CTD [Melhorn 1998]. The first step in controlling the CTD is to understand the compressive neuropathies of the upper extremity [Vender et al. 1998].Table 13-1 outlines the nature and treatment of compressive neuropathies that can occur at the wrist, elbow, and forearm. The compressive neuropathies are discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Locations of Nerve Lesions

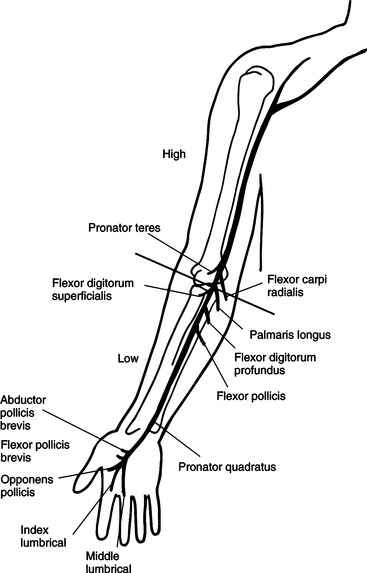

The location of a nerve lesion determines the sensory and motor result. Lesions are referred to as low or high. Low lesions occur distal to the elbow, and high lesions occur proximal to the elbow [Barr and Swan 1988]. High lesions affect more muscles and may affect a larger sensory distribution than low lesions. Therefore, knowledge of relevant anatomy is important.

Substitutions

When a nerve lesion occurs, “there is no opposing balancing force to the intact active muscle group” [Colditz 2002, p. 622]. If a nerve lesion remains unsplinted, the intact musculature overpowers the denervated muscles. Intact musculature takes over and produces movement normally generated by the dennervated muscles [Clarkson and Gilewich 1989]. The person learns to adapt to the imbalance [Posner 2000, Colditz 2002]. An example of a substitution or trick movement is the pinch that develops after a low-level median nerve injury. With the help of the adductor pollicis, the flexor pollicis longus pinches objects against the radial side of the index finger. A therapist may mistakenly think that motor return has occurred for the abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and first and second lumbricals. However, the pinch movement observed is actually a substitution.

Prognosis

Many factors affect the prognosis of recovery from a nerve injury. These factors include the extent of the injury, the cleanliness of the wound, the method of repair, and the client’s age [Skirven 1992, Skirven and Callahan 2002]. Other factors that alter nerve repair include the amount of tension on the repair, the person’s general health, and whether the person smokes. Correct alignment of axons and avoidance of tension on the damaged nerve improve the prognosis. A clean wound has a better prognosis than a dirty wound [Boscheinen-Morrin et al. 1987]. Sharply severed nerves recover better than frayed nerve damage resulting from a crush or gunshot wound [Frykman 1993]. Nerve microsurgery “timed appropriately according to the nature and extent of the injury is essential for a favorable outcome” [Skirven 1992, p. 324]. Age is also a factor in the speed of recovery. A child’s potential for regeneration is greater than an adult’s [Skirven 1992]. Full sensory and motor return occurs often in a child but rarely in an adult.

The rate of axonal regeneration in human beings is 1 to 3 mm per day. Because nerve regeneration is slow, the therapist conducts periodic monitoring (and splinting is often part of the treatment protocol). In addition, the therapist documents results of the evaluation and any changes to the splinting or exercise program.

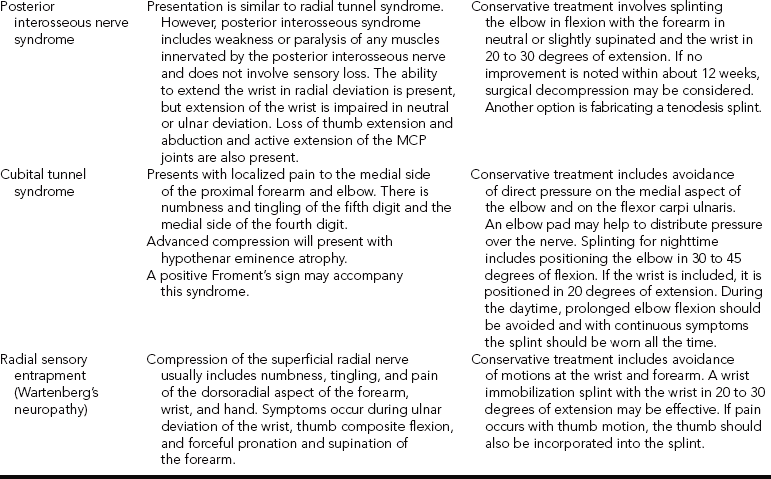

Radial Nerve Injuries

Radial nerve palsies are very common and typically occur from midhumeral fractures or compressions [Arsham 1984, Colditz 1987]. Other causes of superficial radial nerve palsies at the wrist include pressure, edema, and trauma on the nerve from crush injuries; de Quervain’s tendonitis; handcuffs; and a tight or heavy wristwatch [Eaton and Lister 1992]. The location of the radial nerve injury determines which muscles are affected (Figure 13-3).

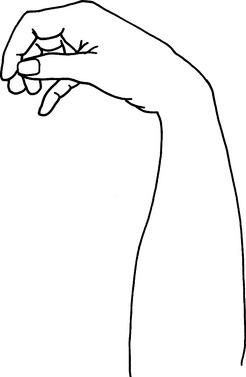

Three lesions are possible when the radial nerve is injured [Colditz 2002]. The first type of lesion involves a high injury at the level of the humerus that results in wrist drop and lack of finger MCP extension (Figure 13-4). With this type of lesion, the triceps are rarely affected unless the injury is extremely high.

The second type of lesion involves the posterior interosseous nerve. After spiraling around the humerus and crossing the elbow, the radial nerve divides into a motor and a sensory branch [Eaton and Lister 1992]. The motor branch is the posterior interosseous nerve, and the sensory branch is the superficial branch of the radial nerve. Compression usually causes this palsy, but lacerations or stab wounds can also be sources of lesions to the posterior interosseous nerve. Radial tunnel syndrome and posterior interosseous nerve compression are two distinct types of compression syndromes that can occur in the same tunnel and with the same nerve. As Gelberman et al. [1993, p. 1870] state, “It is difficult for the conscientious diagnostician to accept the reality that the same nerve compressed in the same anatomical site can result in two entirely different symptom complexes.” Compression of the radial nerve just distal to the elbow between the radial head and the supinator muscle is typically called radial tunnel syndrome [Izzi et al. 2001, Skirvern and Callahan 2002] and is linked to repetitive forearm rotation [Cohen and Garfin 1997]. With radial tunnel syndrome, complaints of pain are usually in the radial nerve distribution of the distal forearm [Hornbach and Culp 2002] and will involve sensory problems without muscle weakness [Eaton and Lister 1992, Gelberman et al. 1993].

Posterior interosseous nerve compression results in rapid motor loss [Gelberman et al. 1993], with no sensory loss [Eaton and Lister 1992, Gelberman et al. 1993, Kleinert and Mehta 1996]. It is characterized by aching on the lateral side of the elbow, difficulty with MCP finger and thumb extension, and difficulty with thumb abduction. Wrist extension is intact, but the wrist tends to radially deviate due to muscle imbalance [Kleinert and Mehta 1996].

The third type of lesion is damage to the sensory branch of the radial nerve. This type of lesion does not result in a functional loss. However, compression symptoms include numbness, tingling, burn, and pain over the dorsoradial surface of the hand [Skirven and Osterman 2002]. Compression of this superficial branch is called Wartenberg’s syndrome [Nuber et al. 1998].

Functional Involvement from Radial Nerve Lesions

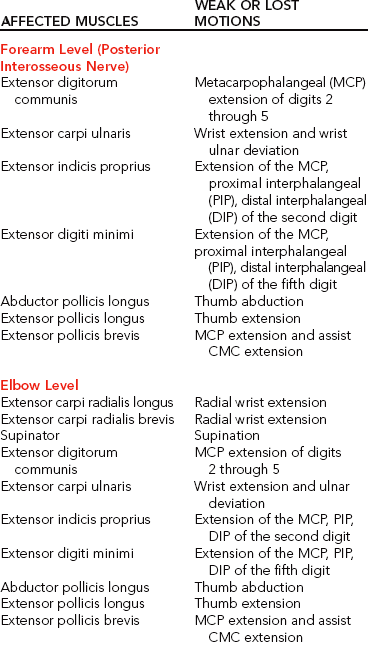

Table 13-2 outlines the muscles and motions that are affected and the lesion locations in radial nerve lesions. After crossing the elbow and dropping below the supinator, the radial nerve divides and forms the posterior interosseous nerve [Colditz 2002]. Lesions and compressions of the posterior interosseous nerve at the forearm level can affect the following muscles:

Loss of these muscles results in a loss of MCP extension of all the digits, loss of thumb radial abduction, and loss of thumb extension. With attempts at wrist extension, strong wrist radial deviation is present. With attempts at finger extension, the MCPs flex and the PIPs extend because the extensor digitorum muscle is affected. In addition to the muscles just indicated, a radial nerve injury at the elbow level can affect the following muscles:

In addition to the motions lost at the forearm level, an injury at the elbow level involves a loss of radial wrist extension, MCP joint extension, thumb extension, thumb radial abduction, and weakened forearm supination.

When a high-level lesion or compression occurs in the upper arm (i.e., axilla level), the injury can affect the triceps and brachioradialis muscles. Loss of these muscles results in lost elbow extension, weak supination, absent wrist and finger extensors, and lost thumb extension and abduction.

The functional results of an axilla-level lesion are a loss of wrist stabilization in an extended position, loss of finger and thumb extension, and loss of thumb abduction. A client with a high radial nerve lesion has poor grip and coordination because of the lack of wrist extensor opposition to the flexors [Fess 1986, Bosheinen-Morrin et al. 1987]. The resulting deformity is called wrist drop.

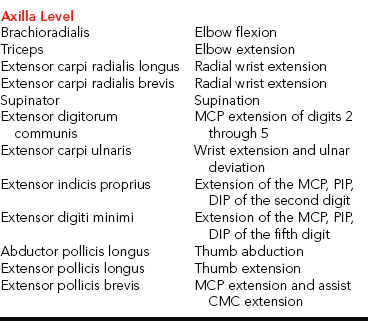

Significant loss of sensation is not present with radial nerve injuries. The superficial sensory branch of the radial nerve supplies sensation to the dorsum of the index and middle fingers and half of the ring finger to the PIP joint level.Figure 13-5 shows a representation of hand sensory distribution from the radial nerve. Laceration or contusion to the sensory branch of the radial nerve can be annoying. This often occurs in conjunction with de Quervain’s release. Sensory compromise over the dorsum of the thumb may result in hypersensitivity. Sometimes a splint or padded device can protect the area while a desensitization program is implemented [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, October 1999].

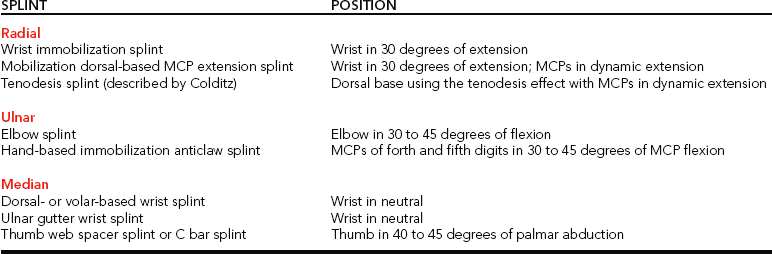

Radial Nerve Injury Splint Intervention

The client benefits from a splint intervention in addition to a therapeutic program. There are several splint options for radial nerve injuries. Splints specific for diagnoses are discussed first, followed by various design options of splints.

Splinting for Radial Tunnel Syndrome

For this condition, the elbow is positioned in approximately 90 degrees flexion, forearm in full supination, and the wrist in slight wrist extension (20 to 30 degrees) [Gelberman et al. 1993, Alba 2002]. Positioning the forearm in supination decompresses pressure on the radial nerve. The splint (Figure 13-6) is worn all the time, with removal for hygiene [Alba 2002]. Kleinert and Mehta [1996] suggest the splinting approach of fabricating a thermoplastic thumb immobilization splint (see Chapter 8).

Figure 13-6 Long-arm elbow and wrist splint for radial tunnel syndrome. [From Alba CD (2002). Therapist’s management of radial tunnel syndrome. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Shirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 696-700.]

Splinting for Posterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome

A couple of splinting options are suggested for posterior interosseous nerve syndrome. One option is to fabricate a long-arm elbow and wrist splint with the elbow in flexion, forearm in neutral or slightly supinated, and the wrist in 20 to 30 degrees of extension. Another option is to fabricate a tenodesis splint because it encourages wrist and finger function [Eaton and Lister 1992]. The tenodesis splint is discussed later in this chapter.

Splinting for Wartenberg’s Neuropathy

For Wartenberg’s neuropathy, a wrist immobilization splint is fabricated with the wrist in 20 to 30 degrees of extension. If pain occurs with thumb motion, the thumb is also incorporated into the splint. Refer to Chapter 8 on how to fabricate a thumb splint.

Wrist Immobilization Splint

The therapist can use a wrist immobilization splint to place the wrist in a functional position of 30 degrees of extension [Cannon et al. 1985]. A client can usually extend the fingers to release an object by using the intrinsic hand muscles [Boscheinen-Morrin et al. 1987]. The therapist keeps in mind the advantages, disadvantages, and patterns of volar and dorsal wrist splints (see Chapter 7). A wrist immobilizer splint may be appropriate to wear on occasions when the client desires a more inconspicuous design than a mobilization splint. A wrist immobilization splint may also be more appropriate for nighttime wear than a mobilization splint.

Wearing a mobilization splint at night may result in damage to the outrigger and injury to the client. Some persons who have heavy demands on their hands prefer the simple wrist immobilization splints to the more fragile outrigger-mobilization designs. A therapist may offer both a wrist immobilization splint and a wrist mobilization splint to the person. Alternating the splints may maximize function.

Mobilization Extension Splints

Mobilization splinting for a radial nerve injury promotes functional hand use [Borucki and Schmidt 1992]. The therapist fabricates a dorsal wrist immobilizer splint as the base for a mobilization extension splint (using elastic for the source of tension) [Arsham 1984]. The dynamic component for this splint positions the MCPs in extension. Several low-profile options exist that can be made with purchased outrigger parts (Figure 13-7). However, Colditz [2002, p. 633] remarks that “one should be cautioned against designs for dynamic wrist and finger extension, because the powerful unopposed flexors often overcome the force of the dynamic splint during finger flexion.”

Figure 13-7 Low-profile designs with pre-purchased outrigger parts. [From Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson JR (2005). Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier/Mosby.]

A mobilization MCP extension splint for radial nerve injury substitutes for the absent muscle power by assisting the MCP extensors. This splint is worn throughout the day until the impaired musculature reaches a manual muscle test (MMT) grade of fair (3) [Callahan 1984]. A client who does not show clinical improvement in three months should return to a physician for consideration of surgical intervention [Eaton and Lister 1992]. Because wrist control usually returns first, the therapist modifies the splint design and uses a hand-based mobilization splint after the forearm-based mobilization splint has been worn [Arsham 1984, Ziegler 1984]. If only one finger is lagging in extension, the therapist dynamically incorporates that finger into the splint [Ziegler 1984].

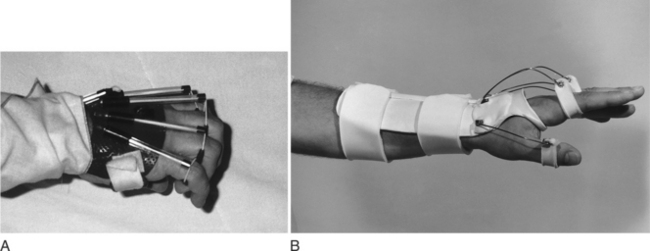

Another type of mobilization splint a therapist uses for radial nerve injuries is a mobilization splint that reestablishes the tendonesis pattern of the hand [Crochetiere et al. 1975; Colditz 1987, 2002]. The tenodesis splint includes a dorsal base splint with a low-profile outrigger that spans from the wrist to each proximal phalanx. This splint is sometimes called a dynamic tenodesis suspension splint [Hannah and Hudak 2001]. Finger loops are worn on each proximal phalanx, and a nylon cord attached from the finger loops is stretched to a point on the dorsal base. A tenodesis pattern occurs when the client flexes the wrist and the fingers extend and when the client extends the wrist and the fingers flex (Figure 13-8).

Figure 13-8 A splint for radial nerve injury. [From Colditz JC (2002). Splinting the hand with a peripheral nerve injury. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Shirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 622-634.]

The splint design using the tenodesis pattern has many advantages. First, the design allows the palmar surface of the hand to be relatively free for sensory input and normal grasp [Colditz 2002]. The wrist is not immobilized. It only moves with the natural tenodesis effect and the thumb can move independently [Colditz 1987, 2002]. In addition, the hand arches are maintained [Colditz 2002]. As wrist extension returns, the client can continue to wear the splint because it does not immobilize the wrist and it enhances the strength of the wrist extensors for functional tasks [Colditz 2002]. Therefore a hand-based splint is not required. The low-profile design also enhances the performance of functional tasks. However, the tenodesis splint design is usually not sturdy enough for people with high load demands on their hands [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, October 1999].

Ulnar Nerve Injuries

Ulnar compression syndromes are the second most common compression neuropathies in the upper extremity [Posner 2000]. An ulnar nerve lesion can occur in conjunction with a median nerve lesion [Enna 1988]. Lesions to the ulnar nerve commonly happen as a result of a fracture of the medial epicondyle of the humerus, a fracture of the olecranon process of the ulna, or a laceration or ganglia at the wrist. Most commonly, compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow takes place at the epicondylar groove, or where the ulnar nerve courses between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle [Posner 2000]. Ulnar nerve compressions at the wrist level within the Guyon’s canal are less common [Posner 2000]. Wrist-level injuries usually result from compression because of the superficial nature of ulnar nerve within the Guyon’s canal [Posner 2000] (seeTable 13-1).

McGowan [1950] developed a grading system for ulnar nerve conditions, with grade I manifesting with paresthesias and clumsiness, grade II exhibiting interosseous weakness and some muscle wasting, and grade III involving paralysis of the ulnar intrinsic muscles. Ulnar nerve injuries at the elbow are classified as acute, subacute, or chronic [Possner 2000]. Acute injuries result from trauma. Subacute develop over time and involve continual elbow compression, such as a factory worker who continuously positions his elbow on a table while doing work. Both acute and subacute injuries respond to conservative interventions, such as reducing elbow flexion during tasks and/or splinting.

Chronic conditions require surgery, especially if daily living tasks are severely impacted [Posner 2000]. Clinically, a person with an ulnar nerve compression at the elbow (cubital tunnel syndrome) will complain of discomfort on the medial side of the arm and numbness and tingling in digits 4 and 5 [Hong et al. 1996]. Prolonged flexion and force from occupations or sports such as baseball and tennis are common causation factors [Fess et al. 2005].

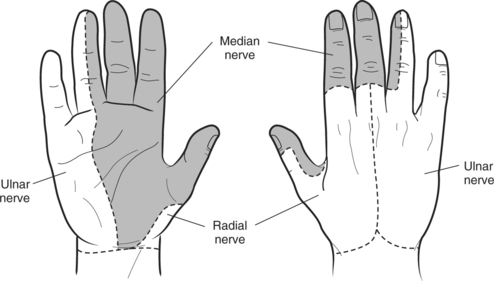

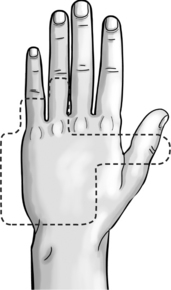

Regardless of the cause or location of an ulnar lesion, if a deformity results it is called a clawhand. Anatomically, this deformity occurs because the MCP joints of the ring and little fingers are positioned in hyperextension. The fourth and fifth digits are incapable of fully extending the PIP and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints because of the unopposed action of the extensor digistorum communis and the extensor digiti minimi (Figure 13-9). In addition, the lumbricals and the intrinsic muscles responsible for interphalangeal (IP) extension are paralyzed [Boscheinen-Morrin et al. 1987].

Functional Implications of Ulnar Nerve Injuries

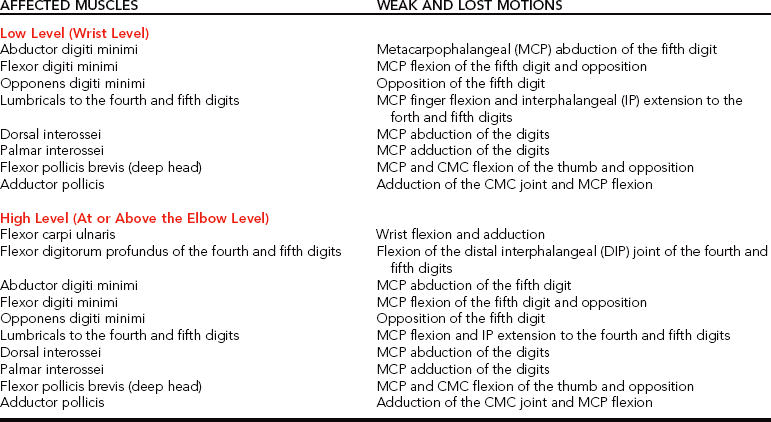

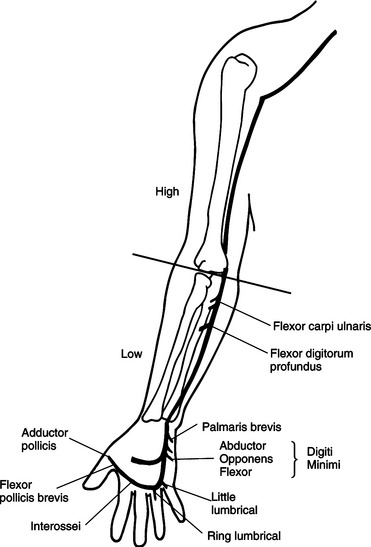

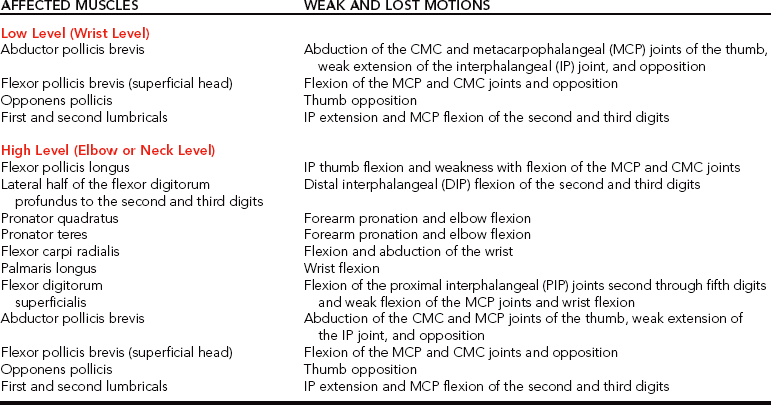

In the early stages of an ulnar nerve injury, a person may have difficulties performing ADL and may experience hand fatigue. Muscle weakness is not usually evident until the condition has progressed [Possner 2000].Table 13-3 identifies the muscles the ulnar nerve innervates in a low-level or wrist lesion and a high-level lesion that occurs at or above the elbow. If an ulnar nerve lesion occurs just distal to the elbow, the extrinsic muscles of the hand are lost because they are innervated distal to the elbow. At the wrist level, compression of the ulnar nerve in the distal part of the ulnar tunnel results in different functional effects based on the zone location of the nerve [Gross and Gelberman 1985, Possner 2000].

Generally, the functional result from a high- or low-level ulnar nerve lesion is loss of pinch and power grip strength [Fess 1986, Skirven 1992]. The client is not able to grasp an object fully because of the denervation of the finger abductors, atrophy of the hypothenar eminence, inability to oppose the little finger to the thumb, and ineffective pinch of the thumb [Boscheinen-Morrin et al. 1987, Salter 1987]. The loss of the first dorsal interosseous muscle and the abductor pollicis leads to unstable pinching of the thumb and index finger [Boscheinen-Morrin et al. 1987]. Loss of lateral finger movements and diminished sensory feedback can affect functional occupational activities such as typing on a computer [Salter 1987].

With a high lesion the loss of the flexor digitorum profundus of the ring and small fingers further compromises hand grasp [Skirven 1992]. In addition, the client presents with weakened wrist ulnar deviation.

Another characteristic of ulnar nerve injuries is a posture called Froment’s sign, which functionally results in flexion of the thumb IP joint during pinching activities [Cailliet 1994]. Froment’s sign is apparent because the adductor pollicis brevis, the deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis, and first dorsal interosseous muscle are not working. Because of these losses, performance of the fine dexterity tasks of daily living is remarkably affected.

The sensory distribution of the ulnar nerve typically innervates the little finger and the ulnar half of the ring finger on the volar and dorsal surfaces of the hand (seeFigure 13-5). Clients who have ulnar nerve compression can experience numbness, tingling, and paresthesia in this nerve distribution and equal sensory loss in high and low lesions. When splinting for ulnar nerve lesions, the therapist monitors the areas of decreased sensation for pressure sores.Figure 13-10 illustrates the muscles an ulnar nerve lesion affects.

Ulnar Nerve Injury Splint Interventions

Treatments for ulnar nerve compression or injury at the elbow and wrist levels require that the client be trained to modify activities that contribute to the development of the problem.

Splinting for Ulnar Nerve Compression at the Elbow

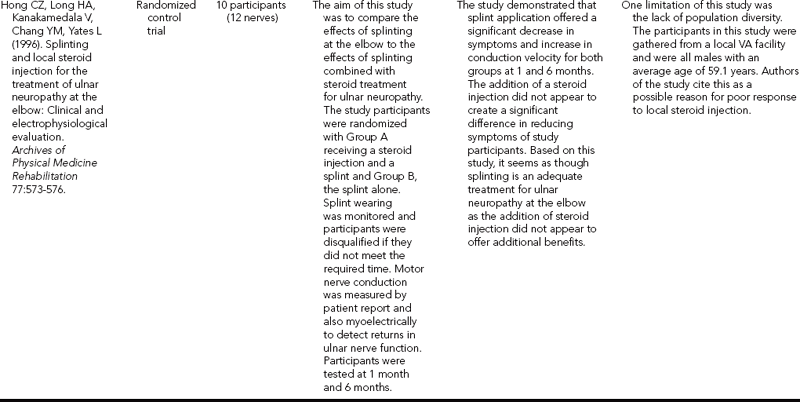

A commonly discussed treatment for compression at the cubital tunnel is an elbow splint with the elbow flexed 30 to 45 degrees [Harper 1990, Aiello 1993]. If included, the wrist is positioned in neutral to 20 degrees of extension. Including the wrist decreases the effects from flexor carpi ulnaris contraction [Posner 2000].

The elbow splint helps to prevent repetitive or prolonged elbow flexion, especially beyond 60 to 90 degrees. Prolonged elbow flexion can stress the ulnar nerve via traction [Harper 1990, Seror 1993] and can increase pressure in the cubital tunnel [MacNicol 1980]. This position commonly occurs during sleep or with computer usage [Seror 1993, Cailliet 1994]. For sporadic or mild symptoms, the elbow splint may be worn during the night for approximately 3 weeks [Blackmore 2002]. If demonstrating dysthesia, decreased sensibility, and continuous symptoms, the client may wear the elbow splint all the time [Cannon 1991, Posner 2000, Blackmore 2002].

Many therapists recommend a soft splinting approach. Several soft elbow splints allow some movement but limit flexion to less than 45 degrees. When fabricating a rigid elbow splint, the therapist chooses a thermoplastic material with the following properties: (1) rigidity so that the thermoplastic material is strong enough to support the weight of the elbow, (2) self-bonding to help with formulation of the crease at the elbow, and (3) conformability and drapability to mold the material over the bony olecranon process (see Chapter 3). When fabricating the splint, the therapist should have an assistant help stabilize the arm or use an elastic wrap bandage. A tuck in the splinting material should be close to the elbow joint, as shown inFigure 13-11. Care must be taken that strapping the thermoplastic material does not provide pressure over the medial elbow area, where the nerve crosses [Posner 2000].

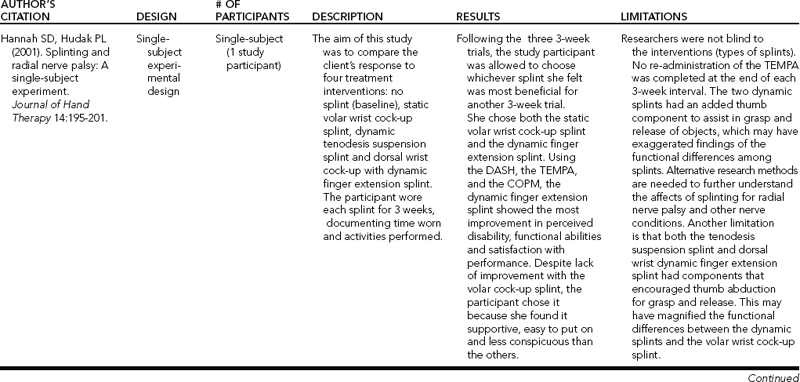

According to one study [Hong et al. 1996] (n = 10), splinting for ulnar nerve compression at the elbow was more effective than steroid injections to the site. Over 6 months, subjects experienced relief from wearing the splint during the night and during activities that were irritating the compression condition.

Hand-based Ulnar Nerve Splint Intervention

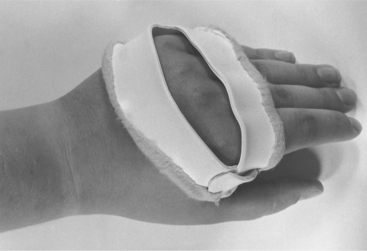

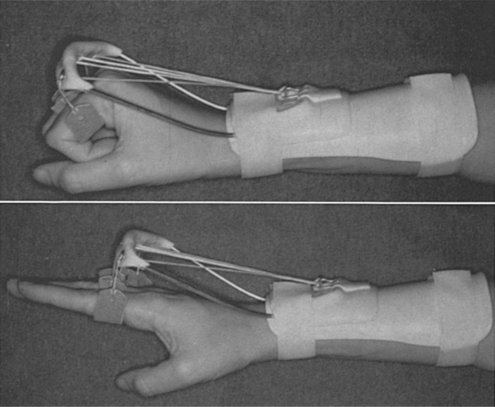

As shown inFigure 13-12, the splint for an ulnar nerve lesion involves positioning the ring and little fingers in 30 to 45 degrees of MCP flexion [Callahan 1984, Cannon et al. 1985]. This position prevents attenuation of the denervated intrinsic muscles and the MCP volar plates of the ring and little fingers [Colditz 2002]. In addition, this position corrects the clawhand posture of MCP hyperextension and PIP flexion. With the MCPs blocked in flexion, the power of the extensor digitorum communis is transferred to the IP joints and allows them to extend in the absence of the intrinsic muscles. Ultimately, this splint will help facilitate the functional grasp of the client [Skirven 1992].

The therapist splints the hand in this position with a mobilizing (dynamic) or immobilizing (static) splint. A client usually wears an immobilization splint continuously, with removal only for hygiene and exercise. Colditz [2002] suggests the fabrication of a less bulky splint to keep from impeding the palmar sensation and function of the hand. One such splint is the figure-of-eight splint design Kiyoshi Yasaki developed at the Hand Rehabilitation Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania [Callahan 1984].

Mobilization Splints for Ulnar Nerve Injuries

The therapist can use a mobilization splint design that includes finger loops attached to the ring and little fingers’ proximal phalanges (Figure 13-13). The rubber band traction pulls the two fingers into MCP flexion and is connected to a soft wrist cuff. The client wears the splint throughout the day, with removal for hygiene and exercise. Physicians usually prescribe this type of splint when there is a need for a strong force to prevent hyperextension contractures at the MCP joints. To supplement this type of splint, a positioning (immobilization) nighttime splint may be necessary. An immobilization hand-based pattern for an ulnar nerve injury (Figure 13-14) is useful for providing a strong counterforce to prevent a clawhand deformity [Callahan 1984].

Figure 13-13 A dynamic extension splint for an ulnar nerve injury. [From Colditz JC (2002). Splinting the hand with a peripheral nerve injury. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Shirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 622-634.]

Another option for splinting the ulnar nerve lesion is a spring-wire-and-foam splint, which is available commercially or can be custom made. Persons appreciate the low-profile design of the spring-wire-and-foam splint, and compliance tends to be high [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, October 1999].

Median Nerve Lesions

Traumatic median nerve lesions can result from humeral fractures, elbow dislocations, distal radius fractures, dislocations of the lunate into the carpal canal, and lacerations of the volar wrist [Skirven 1992]. The classic deformity is called an ape (or simian) hand because with denervation of the thenar eminence it appears flattened. A loss of thumb opposition occurs (Figure 13-15). The thumb is positioned in extension and adduction next to the index finger because of the unopposed action of the extensor pollicis longus and the adductor pollicis [Boscheinen-Morrin et al. 1987]. The thumb web space may contract, and the fingers may show trophic changes. In addition, a slight claw deformity of the index and middle fingers may occur because of the loss of the lumbrical innervation [Salter 1987].

Figure 13-15 The classic median nerve deformity called an ape (or simian) hand. Note the thenar muscle atrophy of the left hand.

Functional Involvement from a Median Nerve Injury

The median nerve in a low-level or wrist lesion and a high-level lesion involving the elbow or neck area innervates the muscles depicted inFigure 13-16 (Table 13-4). The impact on function from a median nerve lesion results in clumsiness with pinch and a decrease in power grip [Boscheinen-Morrin et al. 1987]. Whether a low or high injury, the sensory loss of a median nerve injury is the same. With lack of sensation in the fingers, skilled functions are difficult to perform with the hand. Power grip is affected because the thumb is no longer a stabilizing force as a result of loss of the abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis, and the opponens pollicis. Weakness in the lumbricals of the index and middle fingers further affects skilled movements of the hand [Borucki and Schmidt 1992]. The sensory areas innervated by the median nerve are used for identifying objects, temperature, and texture [Arsham 1984].

Higher lesions can weaken or impair forearm pronation, wrist flexion, thumb IP flexion, and flexion of the proximal and distal IP joints of the index and middle fingers. Compression syndromes that can occur from higher median nerve injuries are pronator syndrome and anterior interosseous syndrome. Pronator syndrome often results from strong and repetitive pronation and supination motions, with the most common compression site between the two heads of the pronator teres [Nuber et al. 1998]. Anterior interosseous syndrome is rare and is distinguished by a vague discomfort in the proximal forearm. It usually involves compression of the deep head of the pronator teres. Clinically, the person presents with an inability to make an O with the thumb and index finger [Nuber et al. 1998].

Thoracic outlet syndrome is sometimes considered an ulnar nerve injury initially or a high-level median nerve injury because it can initially resemble a median nerve compression [Messer and Bankers 1995]. Because median nerve injuries can occur throughout the extremity, it is possible that a person can be mistakenly thought to have one type of median nerve injury when he or she actually has another. Therefore, the astute therapist carefully considers the symptoms presented by the person. For example, a person may have pronator syndrome instead of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) if (1) pain is experienced with resisted pronation and passive supination activities, (2) a positive Tinel’s sign at the proximal forearm is present, (3) tenderness of the pronator muscle is evident, (4) “numbness in the thenar eminence in the distribution of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve” is present [Rehak 2001, p. 535], (5) nocturnal symptoms are absent, (6) muscle fatigue is present, (7) thenar atrophy is absent, or (8) Phalen’s test is negative [Saidoff and McDonough 1997, Nuber et al. 1998, Rehak 2001]. CTS is a likely diagnosis for persons who have complaints of night pain, symptoms with repetitive wrist movements (especially flexion), weakness in thumb opposition and abduction, a positive Phalen’s test, and a positive Tinel’s sign at the wrist [Saidoff and McDonough 1997]. If a person is referred with a diagnosis of CTS and actually has symptoms of pronator syndrome, the therapist calls the referring physician and discusses examination findings.

Frequently, in persons with these syndromes surgical procedures are required to decompress the nerve [Borucki and Schmidt 1992]. On occasion, a physician may request a splint for conservative management of mild cases. For example, for a mild case of pronator tunnel syndrome the physician may prescribe an elbow splint to position the forearm in neutral between pronation and supination and the elbow in flexion (Table 13-5) [Cailliet 1994]. This elbow position takes tension off the nerve, and the forearm position prevents compression via pronator contraction or stretch.

The median nerve’s classic course and sensory distribution include the volar surface of the thumb, index, middle, and radial half of the ring fingers and the dorsal surface of the distal phalanxes of the thumb, index, middle, and radial half of the ring finger (seeFigure 13-5). Clients who have median nerve compression can experience numbness, tingling, and paresthesia in this nerve distribution. Because the area of sensory distribution is large, the therapist monitors and educates clients or caregivers about the associated risks and prevention of skin injury or breakdown.

Splinting Interventions for Median Nerve Injuries

Understanding the functional effects of the muscular loss resulting from a median nerve injury or compression syndrome is important because it influences the therapist’s splint provision. Usually, with a median nerve lesion if the therapist is able to maintain good passive mobility of the joints, extensive splinting may not be necessary and occasional night splinting may be sufficient [Fess 1986].

Splinting for Pronator Syndrome

Clients with pronator syndrome should avoid resisted pronation and passive supination [Saidoff and McDonough 1997]. Other than changing activities that contribute to pronator syndrome, the person may benefit from splinting. One splint option is to place the elbow in 90 degrees flexion, forearm neutral, and the wrist in neutral to slight flexion [Nuber et al. 1998].

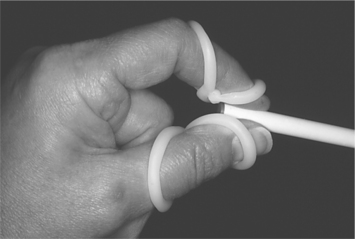

Splinting for Anterior Interosseous Nerve Compression

Other than the suggestion of avoidance of elbow extension and extreme forearm pronation and supination, a couple of splinting options are recommended. One option is to immobilize the elbow in 90 degrees flexion and the forearm in neutral. As discussed, absence of this nerve results in difficulty making an O with the thumb and index finger flexed. To compensate for this deficit, the therapist fabricates a small thermoplastic splint to block thumb IP and index distal interphalangeal (DIP) extension [Colditz 2002] (Figure 13-17).

Figure 13-17 To encourage finger tip to thumb prehension, these small splints help someone with anterior interosseus nerve palsy. [From Colditz JC (2002). Splinting the hand with a peripheral nerve injury. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Shirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 622-634.]

Splinting for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

The most common type of median nerve compression is CTS, which compresses the median nerve at the wrist. Compression at the wrist occurs because of a discrepancy in volume of the rigid carpal canal and its content, consisting of the median nerve and flexor tendons. Some conditions (such as diabetes, pregnancy, Dupuytren’s disease, and CMC arthritis) can be associated with CTS. Home, leisure, and occupational activities involving repetitive or sustained wrist flexion, extension, and ulnar deviation; forearm supination; forceful gripping; and pinching contribute to the development and exacerbation of CTS. Vibration, cold temperatures, and constriction over the wrist can also be contributing factors [Feldman et al. 1987, Wieslander et al. 1989, Barnhart et al. 1991, Schottland et al. 1991, Ostorio et al. 1994]. When manifestations are primarily sensory and occur from overuse or occupational causes, splinting of the wrist often helps reduce pain and symptoms [Borucki and Schmidt 1992].

Often, other therapeutic interventions need to accompany the splinting program. These include ergonomic adaptations for home, leisure, and work environments; education on prevention; activity modifications; a range-of-motion program with emphasis on tendon and nerve gliding exercises; and edema-control techniques [Sailer 1996]. See Chapter 7 for an overview of efficacy studies on carpal tunnel intervention.

Usually, any splint for CTS positions the wrist as close to neutral as possible. This helps maximize available carpal tunnel space, minimize median nerve compression, and provide pain relief [Kruger et al. 1991, Messer and Bankers 1995]. A wrist immobilization splint is commonly worn at night, and sometimes during home, leisure, or work activities that involve repetitive stressful wrist movements. As discussed in Chapter 7, the wearing schedule can vary but it is usually important at minimum to require nighttime wear to prevent extreme wrist postures that can occur during sleep [Sailer 1996]. The wearing schedule should be carefully monitored to prevent weakening of the muscles as a result of inactivity [Messer and Bankers 1995]. In addition, the splint may exacerbate symptoms if the person wearing it fights against it [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, October 1999].

Volar Wrist Immobilization Splint

Some clients and therapists prefer volar wrist splints, which provide adequate support to the wrist. A volar wrist splint with a gel sheet or elastomer putty insert may be beneficial to control scar formation after carpal tunnel release surgery. A disadvantage of the volar wrist splint design for CTS is that the splint may interfere with palmar sensation [Borucki and Schmidt 1992]. Positioning the wrist in the splint is important. A poorly designed wrist splint may compress the carpal tunnel area of the wrist.

Dorsal or Ulnar Gutter Wrist Immobilization Splint

Other splinting approaches for CTS include fabrication of dorsal, ulnar gutter, or circumferential wrist splints. An advantage of the dorsal wrist splint is that there is no thermoplastic material directly over the carpal tunnel, thus avoiding compression. However, a disadvantage of the dorsal wrist splint is that it may not provide as much support and distribute pressure as well as the volar wrist splint. However, some therapists fabricate the splint with a larger palmar area for more support. An ulnar gutter wrist splint may also position the wrist in neutral and is less likely to compress the carpal tunnel. A circumferential wrist splint results in a high degree of immobilization of the wrist (see Chapter 7).

Some clients may be more comfortable with soft prefabricated wrist splints. The therapist checks the splint on the person to ensure a correct fit for function [Arsham 1984].

Splinting Median Nerve Injuries with Thumb Involvement

For a client who has a median nerve injury involving the thumb, as in the later stages of CTS, the therapist addresses loss of thumb opposition for functional grasp and pinch. The therapist positions and splints the thumb in opposition and palmar abduction, which assists the thumb for tip prehension. A C bar between the thumb and the index finger helps maintain the thumb web space. The thumb web space is a common site for muscular shortening of the adductor pollicis after median nerve damage. The splint design is usually static. A static splint for a median nerve injury with thumb involvement may benefit from a hand-based thumb spica splint (see Chapter 8).

For a low-level median nerve injury, the therapist may choose to fabricate a thumb web spacer splint (Figure 13-18). The web spacer splint allows free wrist mobility [Borucki and Schmidt 1992]. If the therapist fabricates a mobilization thumb splint, a static thumb spica splint may be incorporated into the splint-wearing program for nighttime wear.

Splinting for Combined Median Ulnar Nerve Injuries

Sometimes with extensive injuries both median and ulnar nerves are involved. In that case, splinting to prevent further deformities involves splint designs that look similar to a singular nerve injury but with all digits included. The thumb may be included if it is affected (Figure 13-19).

Summary

Splinting for nerve injuries involves a comprehensive knowledge of the muscular, sensory, and functional implications. There are various splinting interventions for nerve injuries (Table 13-6). However, the therapist must note that these are general guidelines and that physicians and experienced therapists may have other specific protocols for positioning and splinting.

1. Which factors are important in the prognosis of a peripheral nerve lesion?

2. What are the deformities resulting from radial, ulnar, and median nerve lesions?

3. What are the functional results of radial, ulnar, and median nerve lesions?

4. What are the splinting options for radial nerve injuries? In which position should the therapist splint the hand?

5. What is the proper type, position, and thermoplastic material needed for fabrication of a splint for ulnar nerve compression at the elbow?

6. What is the proper splinting position for a clawhand deformity? Why is this a good position?

7. What are the advantages and disadvantages of the different approaches to wrist splinting for carpal tunnel syndrome?

8. What is the appropriate position in which to splint a hand with a median nerve lesion that includes thumb symptoms?

References

Aiello, B. Ulnar nerve compression in cubital tunnel. In: Clark GL, Shaw EF, Aiello WB, Eckhaus D, Eddington LV, eds. Hand Rehabilitation: A Practical Guide. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1993.

Alba, CD. Therapist’s management of radial tunnel syndrome. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Shirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:696–700.

Arsham, NZ. Nerve injury. In: Ziegler EM, ed. Current Concepts in Orthotics: A Diagnosis-related Approach to Splinting. Germantown, WI: Rolyan Medical Products, 1984.

Barnhart, S, Demers, PA, Miller, M, Longstreth, WT, Rosenstock, L. Carpal tunnel syndrome among ski manufacturing workers. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environmental Health. 1991;17:46–52.

Barr, NR, Swan, D. The Hand: Principles and Techniques of Splintmaking. Boston: Butterworth Publishers, 1988.

Blackmore, SM. Therapist’s management of ulnar nerve neuropathy at the elbow. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Shirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:679–689.

Borucki, S, Schmidt, J. Peripheral neuropathies. In: Aisen ML, ed. Orthotics in Neurologic Rehabilitation. New York: Demos Publications, 1992.

Boscheinen-Morrin, J, Davey, V, Conolly, WB. Peripheral nerve injuries (including tendon transfers). In: Boscheinen-Morrin J, Davey V, Conolly WB, eds. The Hand: Fundamentals of Therapy. Boston: Butterworth Publishers, 1987.

Cailliet, R. Hand Pain and Impairment, Fourth Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1994.

Callahan, A. Nerve injuries. In: Malick MH, Kasch MC, eds. Manual on Management of Specific Hand Problems. Pittsburgh: American Rehabilitation Educational Network, 1984.

Cannon NM, ed. Diagnosis and Treatment Manual for Physicians and Therapists, Third Edition, Indianapolis: The Hand Rehabilitation Center of Indiana, 1991.

Cannon, NM, Foltz, RW, Koepfer, JM, Lauck, MF, Simpson, DM, Bromley, RS. Manual of Hand Splinting. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1985.

Chan, RKY. Splinting for peripheral nerve injury in the upper limb. Hand Surgery. 2002;7(2):251–259.

Clarkson, HM, Gilewich, GB. Musculoskeletal Assessment: Joint Range of Motion and Manual Muscle Strength. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1989.

Cohen, MS, Garfin, SR. Nerve compression syndromes: Finding the cause of upper-extremity symptoms. Consultant. 1997;37:241–254.

Colditz, JC. Splinting for radial nerve palsy. J Hand Ther. 1987;1:18–23.

Colditz, JC. Splinting the hand with a peripheral nerve injury. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Shirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:622–634.

Crochetiere, WJ, Goldstein, SA, Granger, GV, Ireland, J. The Granger Orthosis for Radial Nerve Palsy. Orthotics and Prosthetics. 1975;29(4):27–31.

Eaton, CJ, Lister, GD. Radial nerve compression. Hand Clinics. 1992;8(2):345–357.

Enna, CD. Peripheral Denervation of the Hand. New York: Alan R. Liss, 1988.

Feldman, RG, Travers, PH, Chirico-Post, J, Keyserling, WM. Risk assessment in electronic assembly workers: Carpal tunnel syndrome. Journal of Hand Surgery (Am). 1987;12(5):849–855.

Fess, EE. Rehabilitation of the patient with peripheral nerve injury. Hand Clinics. 1986;2(1):207–215.

Fess, EE, Gettle, KS, Philips, CA, Janson, JR. Hand Splinting Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby, 2005.

Frykman, GK. The quest for better recovery from peripheral nerve injury: Current status of nerve regeneration research. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1993;6(2):83–88.

Gelberman, RH, Eaton, R, Urbanisk, JR. Peripheral nerve compression. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1993;75A:1854–1878.

Greene, DP, Roberts, SL. Kinesiology Movement in the Context of Activity. St. Louis: Mosby, 1999.

Gross, MS, Gelberman, RH. The anatomy of the distal ulnar tunnel. Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research. 1985;196:238–247.

Hannah, SD, Hudak, PL. Splinting and radial nerve palsy: A single-subject experiment. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2001;14:195–201.

Harper, BD. The drop-out splint: An alternative to the conservative management of ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1990;3:199–210.

Hong, CZ, Long, HA, Kanakamedala, V, Chang, YM. Splinting and local steroid injection for the treatment of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: Clinical and electrophysiological evaluation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1996;77:573–576.

Hornbach & Culp. Radial tunnel syndrome. In Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Shirven Tm, Schneider LH, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand, Fifth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Izzi, J, Dennison, D, Noerdlinger, M, Dasilva, M, Akelman, E. Nerve injuries of the elbow, wrist, and hand in athletes. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 2001;20(1):203–217.

Jebson, PJL, Gaul, JS. Peripheral nerve injury. In: Jebson PJL, Kasdan ML, eds. Hand Secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 1998.

Kleinert, MJ, Mehta, S. Radial nerve entrapment. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 1996;27:30.

Kruger, VL, Kraft, GH, Deitz, JC, Ameis, A, Polissar, L. Carpal tunnel syndrome: Objective measures and splint use. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1991;72(7):517–520.

MacNicol, MF. Mechanics of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br). 1980;62B:53. [518].

McGowan, AJ. The results of transposition of the ulnar nerve for traumatic ulnar neuritis. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br). 1950;23B:293–301.

Melhorn, JM. Cumulative trauma disorders and repetitive strain injuries: The future. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1998;351:107–126.

Messer, RS, Bankers, RM. Evaluating and treating common upper extremity nerve compression and tendonitis syndromes… without becoming cumulatively traumatized. Nurse Practitioner Forum. 1995;6(3):152–166.

Novak, CB, Mackinnon, SE. Nerve injury in repetitive motion disorders. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1998;351:10–20.

Novak, CB, Mackinnon, SE. Evaluation of nerve injury and nerve compression in the upper quadrant. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2005;18:230–240.

Nuber, GW, Assenmacher, J, Bowen, MK. Neurovascular problems in the forearm, wrist, and hand. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 1998;17(3):585–610.

Omer, G. Nerve response to injury and repair. In Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand, Third Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1990.

Ostorio, AM, Ames, RG, Jones, J, Castorina, J, Rempel, D, Estrin, W, Thompson, D. Carpal tunnel syndrome among grocery store workers. American Journal of Internal Medicine. 1994;25:229–245.

Posner, MA. Compressive neuropathies of the ulnar nerve at the elbow and wrist. AAOS Instructional Course Lectures. 2000;49:305–317.

Rehak, DC. Pronator syndrome. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 2001;20(30):531–540.

Saidoff, DC, McDonough, AL. Critical Pathways in Therapeutic Intervention: Upper Extremities. St. Louis: Mosby, 1997.

Sailer, SM. The role of splinting and rehabilitation. Hand Clinics. 1996;12(2):223–240.

Salter, MI. Hand Injuries: A Therapeutic Approach. Edinburgh, London: Churchill Livingstone, 1987.

Schottland, JR, Kirschberg, GJ, Fillingim, R, Davis, VP, Hogg, F. Median nerve latencies in poultry processing workers: An approach to resolving the role of industrial ‘cumulative trauma’ in the development of carpal tunnel syndrome. Journal of Occupational Medicine. 1991;33:627–631.

Seddon, HJ. Three types of nerve injury Brain. A journal of neurology. 1943;66:237–288.

Seror, P. Treatment of ulnar nerve palsy at the elbow with a night splint. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br). 1993;75(2):322–327.

Skirven, T. Nerve injuries. In: Stanley BG, Tribuzi SM, eds. Concepts in Hand Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 1992:322–338.

Skirven, TM, Callahan, AD. Therapist’s management of peripheral-nerve injuries. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Shirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:599–621.

Skirven, T, Osterman, AL. Clinical examination of the wrist. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Shirven TM, Schneider LH, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1099–1116.

Spinner, M. Nerve lesions in continuity. In: Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand. Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1990:523–529.

Sunderland, S. The peripheral nerve trunk in relation to injury: A classification of nerve injury. In: Sunderland S, ed. Nerves and Nerve Injuries. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1968:127–137.

Upton, AR, McComas, AJ. The double crush in nerve entrapment syndromes. Lancet. 1973;2:359–362.

Vender, MI, Truppa, KL, Ruder, JR, Pomerance, J. Upper extremity compressive neuropathies. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: State of the Art Reviews. 1998;12(2):243–262.

Wieslander, G, Norback, D, Gothe, C, Juhlin, L. Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and exposure to vibration, repetitive wrist movements and heavy manual work: A case-referent study. British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 1989;46:43–47.

Ziegler, EM. Current Concepts in Orthotics: A Diagnosis-related Approach to Splinting. Germantown, WI: Rolyan Medical Products, 1984.