Thumb Immobilization Splints

1 Discuss important functional and anatomic considerations for splinting the thumb.

2 List appropriate thumb and wrist positions in a thumb immobilization splint.

3 Identify the three components of a thumb immobilization splint.

4 Describe the reasons for supporting the joints of the thumb.

5 Discuss the diagnostic indications for a thumb immobilization splint.

6 Discuss the process of pattern making and splint fabrication for a thumb immobilization splint.

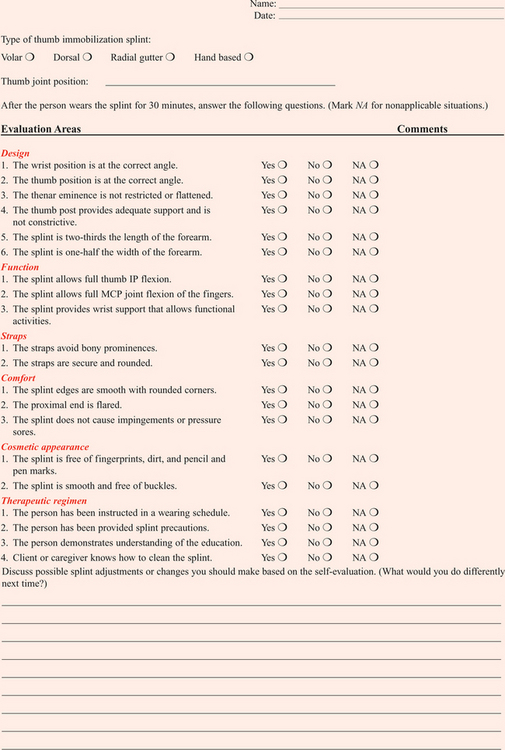

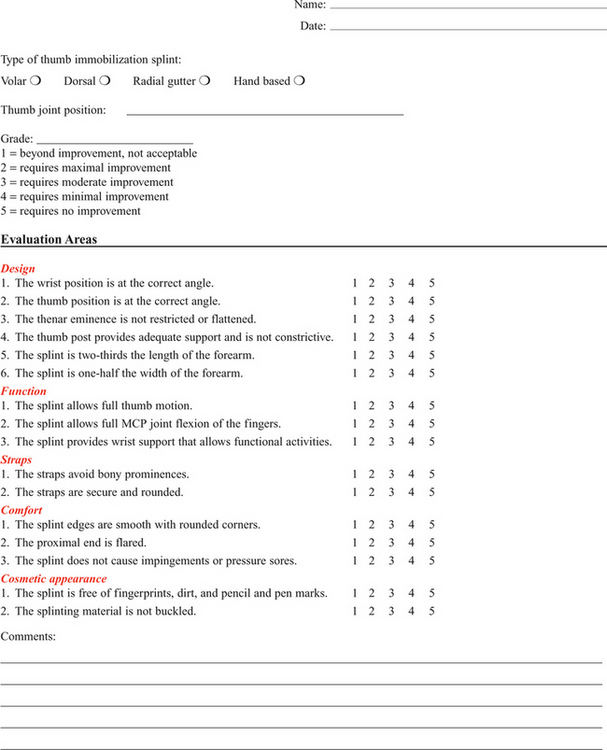

7 Describe elements of a proper fit of a thumb immobilization splint.

8 List general and specific precautions for a thumb immobilization splint.

9 Use clinical reasoning to evaluate fit problems of a thumb immobilization splint.

10 Use clinical reasoning to evaluate a fabricated thumb immobilization splint.

11 Apply knowledge about thumb immobilization splinting to a case study.

12 Understand the importance of evidenced-based practice with thumb immobilization splint provision.

13 Describe the appropriate use of prefabricated thumb splints.

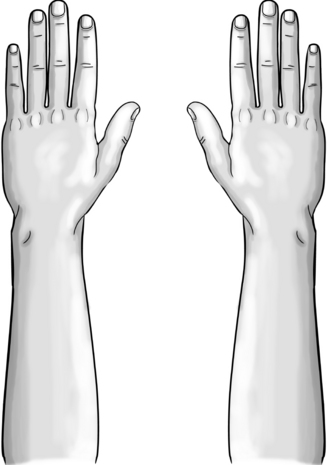

A commonly prescribed splint in clinical practice is the thumb palmar abduction immobilization splint [American Society of Hand Therapists 1992]. Other names for this splint are the thumb spica splint, the short or long opponens splint [Tenney and Lisak 1986], and the thumb gauntlet splint. The purpose of this splint is to immobilize, protect, rest, and position one or all of the thumb carpometacarpal (CMC), metacarpophalangeal (MCP), and interphalangeal (IP) joints while allowing the other digits to be free. Thumb immobilization splints can be divided into two broad categories: (1) forearm based and (2) hand based. Forearm-based thumb splints stabilize the wrist as well as the thumb. Stabilizing the wrist is beneficial for a painful wrist as the splint provides support. The hand-based immobilization splints provide stabilization for the thumb while allowing for wrist mobility.

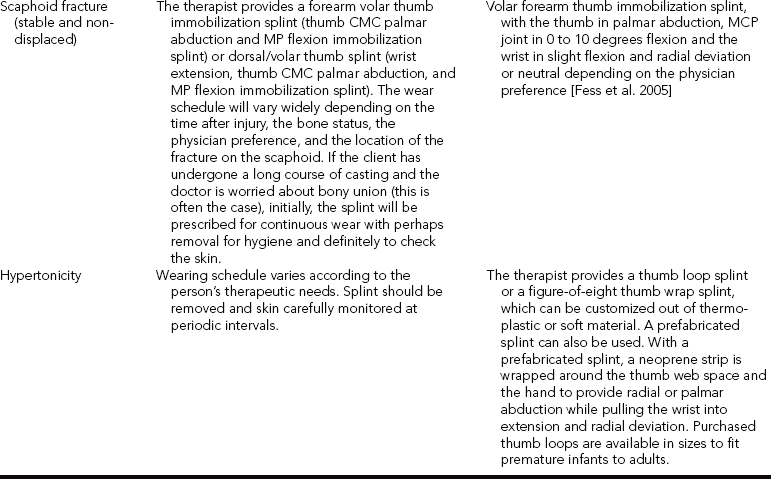

Forearm-based or hand-based thumb immobilization splints are often used to help manage different conditions that affect the thumb’s CMC, MP, or IP joints. For people who have de Quervain’s tenosynovitis a forearm-based thumb splint provides rest, support, and protection of the tendons that course along the radial side of the wrist into the thumb joints. The therapist also applies a forearm-based thumb immobilization splint to splint postoperatively for control of motion in persons with rheumatoid arthritis after a joint arthrodesis or replacement. With the resulting muscle imbalance from a median nerve injury, the therapist may apply a hand-based thumb immobilization splint to keep the thumb web space adequately open. (Refer to Chapter 13 for more information on nerve injury). In addition, the thumb immobilization splint can position the thumb before surgery [Geisser 1984]. The splint provides support and positioning after traumatic thumb injuries, such as sprains, joint dislocations, ligament injuries, and scaphoid fractures. Frequently a hand-based thumb immobilization splint is applied to persons with gamekeeper’s thumb, which involves the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb MCP joint. For hypertonicity a thumb splint sometimes called a figure-of-eight thumb wrap or thumb loop splint facilitates hand use by decreasing the palm-in-thumb posture or palmar adduction that is often associated with this condition. Therefore, because this splint is so commonly prescribed it is important that therapists become familiar with its application and fabrication.

Functional and Anatomic Considerations for Splinting the Thumb

The thumb is essential for hand functions because of its overall importance to grip, pinch, and fine manipulation. The thumb’s exceptional mobility results from the unique shape of its saddle joint, the arrangement of its ligaments, and its intrinsic musculature [Belkin and English 1996, Tubiana et al. 1996, Colditz 2002]. The thumb provides stability for grip, pinch, and mobility because it opposes the fingers for fine manipulations [Wilton 1997]. Sensory input to the tip of the thumb is important for functional grasp and pinch.

A thorough understanding of the anatomy and functional movements of the thumb is necessary before the therapist attempts to splint the thumb. The therapist must understand that the most crucial aspect of the thumb immobilization splint design is the position of the CMC joint [Wilton 1997]. Positioning of the thumb in a thumb post allows for palmar abduction and some opposition, which are critical motions for functional prehension. See Chapter 4 for a review of the anatomy and functional movements of the thumb.

Features of the Thumb Immobilization Splint

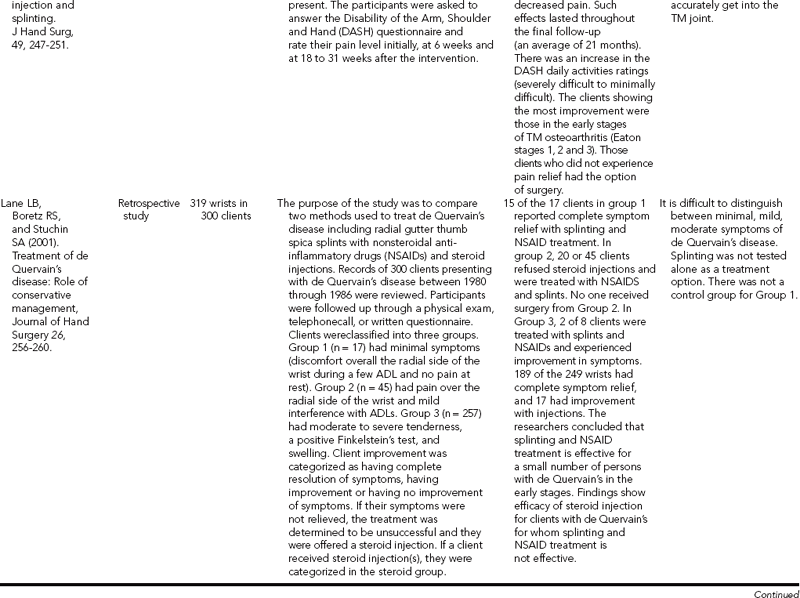

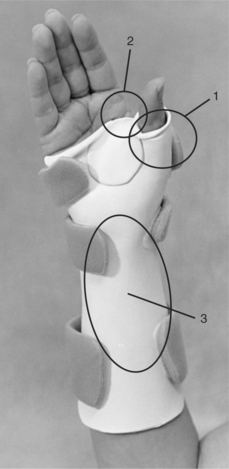

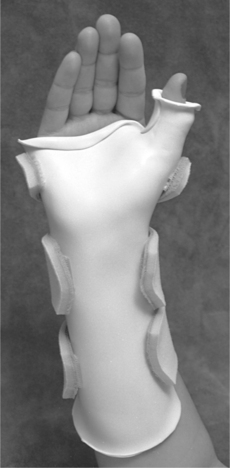

The thumb immobilization splint prevents motion of one, two, or all of the thumb joints [Fess et al. 2005]. The splint has numerous design variations. It can be a volar (Figure 8-1), dorsal (Figure 8-2), or radial gutter (Figure 8-3). The splint may be hand based or wrist based, depending on the person’s diagnosis, the anatomic structures involved, and the associated pain at the wrist. If the wrist is included, the wrist position will vary according to the diagnosis. For example, with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis the wrist is commonly positioned in 15 degrees of extension to take the pressure off the tendons.

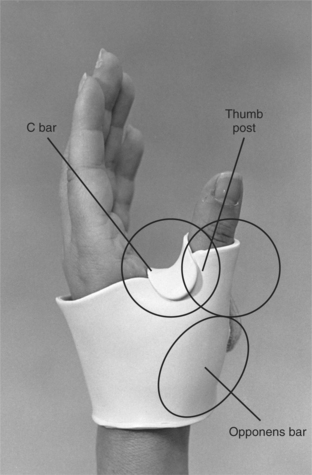

The splint components fabricated in the final product will vary according to the thumb joints that are included. The final splint product will be formed based on the therapeutic goals for the client. The therapist should have a good understanding of the purpose and the fabrication process for the various splinting components. Central to most thumb immobilization splints are the opponens bar, C bar, and thumb post (Figure 8-4) [Fess et al. 2005]. The opponens bar and C bar position the thumb, usually in some degree of palmar abduction. The thumb post, which is an extension of the C bar, immobilizes the MP only or both the MP and IP joints.

The position of the thumb in a splint varies from palmar abduction to radial abduction, depending on the person’s diagnosis. With some conditions, such as arthritis, the therapist can assist prehension by stabilizing the thumb CMC joint in palmar abduction and opposition. Certain diagnostic protocols—such as those for extensor pollicis longus (EPL) repairs, tendon transfers for thumb extension, and extensor tenolysis of the thumb—require the thumb to have an extension and a radial abducted position [Cannon et al. 1985].

The thumb immobilization splint may do one of the following: (1) stabilize only the CMC joint; (2) include the CMC and MP joints; or (3) encompass the CMC, MCP, and IP joints. The physician’s order may specify which thumb joints to immobilize in the splint. In some situations, the therapist may be responsible for determining which joints the splint should stabilize. The therapist uses diagnostic protocols and an assessment of the person’s pain to make this decision. If the therapist deems it necessary to limit thumb motion and to protect the thumb, the IP may be immobilized. Certain diagnostic protocols (such as those for thumb replantations, tendon transfers, and tendon repairs) often require the inclusion of the IP joint in the splint [Tenney and Lisak 1986]. Overall the therapist should fabricate a splint that is the most supportive and least restrictive in movement.

Diagnostic Indications

Therapists fabricate thumb immobilization splints in general and specialized hand therapy practices. Specific diagnostic conditions that require a thumb immobilization splint include, but are not limited to, the following: scaphoid fractures, stable fractures of the proximal phalanx of the first metacarpal, tendon transfers, radial or ulnar collateral ligament strains, repair of MCP joint collateral ligaments, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, median nerve injuries, MCP joint dislocations, capsular tightness of the MCP and IP joints after trauma, post-traumatic adduction contracture, extrinsic flexor or extensor muscle contracture, flexor pollicis longus (FPL) repair, uncomplicated EPL repairs, hypertonicity, and congenital adduction deformity of the thumb.

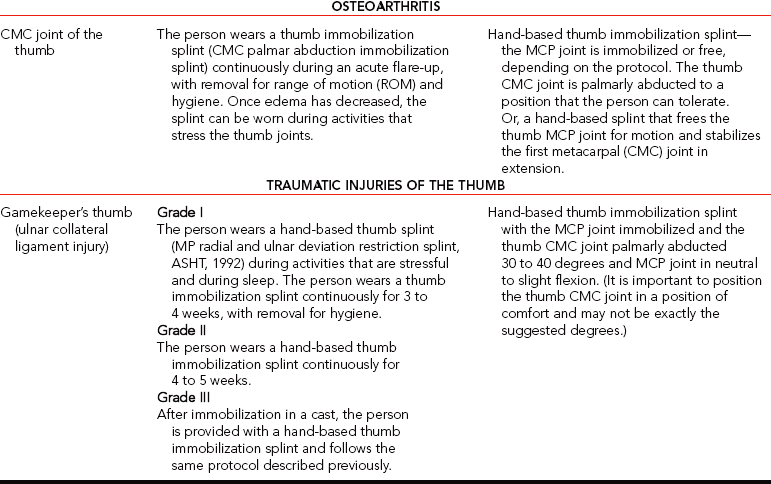

Treatment of many of these conditions may require the expertise of experienced hand therapists. In general clinical practice, therapists commonly treat persons who have de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, fractures, and ligament injuries. (Table 8-1 contains guidelines for these hand conditions.) The novice therapist should keep in mind that physicians and experienced therapists may have their own guidelines for positioning and splint-wearing schedules. The therapist should also be aware that thumb palmar abduction may be uncomfortable for some persons. Therefore, the thumb may be positioned midway between radial and palmar abduction.

Splinting for de Quervain’s Tenosynovitis

De Quervain’s tenosynovitis, which results from repetitive thumb motions and wrist ulnar deviation, is a form of tenosynovitis affecting the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and the extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) in the first dorsal compartment. Those persons whose occupations involve repetitive wrist deviation and thumb motions (such as the home construction tasks of painting, scraping, wall papering, and hammering) are prone to this condition [Idler 1997]. De Quervain’s tenosynovitis is the most commonly diagnosed wrist tendonitis in athletes [Rettig 2001], such as with golfers [McCarroll 2001]. It may be recognized by pain over the radial styloid, edema in the first dorsal compartment, and positive results from the Finkelstein’s test.

During the acute phase of this condition, conservative therapeutic management involves immobilization of the thumb and wrist for symptom control [Lee et al. 2002]. This splint is classified by the American Society of Hand Therapists (ASHT) as a wrist extension, thumb CMC palmar abduction and MP flexion immobilization splint [ASHT 1992]. It may cover the volar or dorsal forearm or the radial aspect of the forearm and hand. The therapist positions the wrist in 15 degrees of extension, neutral wrist deviation, 40 to 45 degrees of palmar abduction of the thumb CMC joint, and 5 to 10 degrees of flexion in the MCP joint [Idler 1997]. Usually the therapist allows the IP joint to be free for functional activities and includes the joint in the splint if the person is overusing the thumb or fights the splint, causing even more pain.

The splint is worn continuously, with removal for hygiene and exercise within a pain-free range [Lee et al. 2002]. A prefabricated splint is recommend after the person’s pain subsides [Lee et al. 2002] for work and sports activities [Fess et al. 2005], or if the person does not want to wear a custom splint [Biese 2002]. Post-surgical management of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis also involves splinting, usually for 7 to 10 days [Rettig 2001].

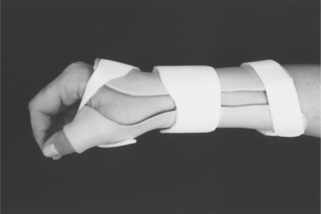

Few studies have considered the efficacy of thumb splinting for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis and results have been variable (seeTable 8-2). Lane et al. [2001] studied 300 subjects and compared splinting with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroid injections over a 2- to 4-week time period. Subjects were splinted in a custom thumb immobilization splint with the wrist in neutral and the thumb in 30 degrees between palmar and radial abduction. Subjects were placed in three groups based on symptoms (minimal, mild, moderate/severe). Those subjects who had mild symptoms responded well to splinting with NSAIDs. Limitations of this study included no control group for the mild symptom group, small numbers in the mild group, the subjective nature of classifying subjects, and no mention of a splint-wearing schedule.

Weiss et al. [1994] (n = 93) compared splinting to steroid injection or combined in treatment with steroid injections. They did not find strong benefits for thumb splinting. Witt et al. [1991] (n = 95) also studied the provision of a long thumb immobilization splint including the wrist (which was worn continuously for 3 weeks, along with steroid injection) and had a good success rate. Avci et al. [2002] focused their research on conservative treatment of 19 pregnant women with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. One group received cortisone injections and the other group received thumb splints. The group receiving cortisone injections had complete pain relief compared to partial relief from the splint-wearing group. The splint-wearing group experienced pain relief only when wearing the splint. Finally, the researchers pointed out that pregnancy-related de Quervain’s disease is self-limiting (with cessation of symptoms after breast feeding is terminated). Much more research needs to be completed to truly determine the efficacy of thumb splinting with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. It is helpful for therapists to review these studies because these also provide information about the effectiveness of physician treatments, such as steroid injections, their clients are receiving.

Splinting for Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis often affects the thumb joints, particularly the MCP and CMC joints. Splinting for rheumatoid arthritis can reduce pain, slow deformity, and stabilize the thumb joints [Ouellette 1991]. The disease includes three stages, each of which has a different splinting approach, even though the therapist may apply the same thumb immobilization splint.

The first stage involves an inflammatory process. The goal of splinting at this stage is to rest the joints and reduce inflammation. The person wears the thumb immobilization splint continuously during periods of inflammation and periodically thereafter for pain control as necessary. When the disease progresses in the second stage, the hand requires mechanical support because the joints are less stable and are painful with use. The person wears a thumb immobilization splint for support while doing daily activities and perhaps at night for pain relief. In the third stage, pain is usually not a factor, but the joints may be grossly deformed and unstable. In lieu of surgical stabilization, a thumb immobilization splint may provide support to increase function during certain activities. At this stage, splinting is rarely helpful for the person at night unless to help manage pain [personal communication, J. C. Colditz, April 1995]. Another treatment approach is to provide the person who has arthritis with a rigid and a soft splint along with education for the benefits and activity usages of each type [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, June 2006].

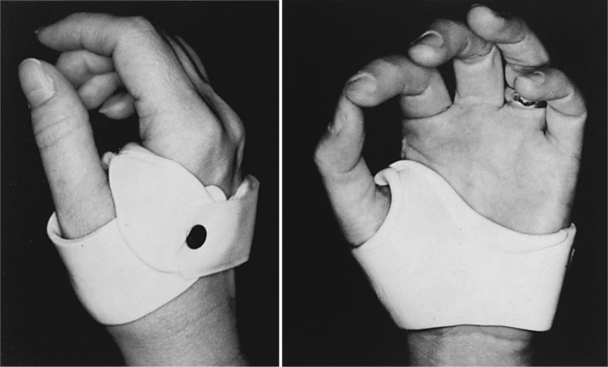

Common thumb deformities from the arthritic process are boutonnière’s deformity (type I, MP joint flexion and IP joint extension) and swan neck deformity (type 3, MP extension or hyperextension and IP flexion) [Nalebuff 1968, Colditz 2002]. During the beginning stages of boutonnière’s deformity a circumferential neoprene splint is applied to support the MCP joint with the IP joint free to move [Colditz 2002]. To address progression of MCP joint deformity, Colditz [2002] suggested a carefully fabricated thermoplastic splint to stabilize the joint to eliminate volar subluxation and to allow for CMC motion (Figure 8-5).

Figure 8-5 This splint stabilizes the MCP joint. [From Colditz JC (2002). Anatomic considerations for splinting the thumb. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Skirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 1858-1874.]

For early stages of swan neck deformity, a small custom-fitted dorsal thermoplastic splint over the MCP joint prevents MCP hyperextension [Colditz 2002]. Later dorsal and radial subluxation at the CMC joint causes CMC joint adduction, MCP hyperextension, and IP flexion [Colditz 2002]. For this deformity, Colditz [2002] suggested fabricating a hand-based thumb immobilization splint that blocks MCP hyperextension (Figure 8-6). With rheumatoid arthritis, laxity of the ulnar collateral ligament at the IP and MCP joint can also develop.Figure 8-7 shows a functional splint, which can also be used with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis for lateral instability of the thumb IP joint.

Figure 8-6 This splint, which blocks MCP hyperextension, is applied for advanced swan neck deformity. [From Colditz JC (2002). Anatomic considerations for splinting the thumb. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Skirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 1858-1874.]

Figure 8-7 This small splint can help a person with arthritis who has lateral instability of the thumb IP joint. [From Colditz JC (2002). Anatomic considerations for splinting the thumb. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Skirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 1858-1874.]

One approach to splinting a hand with arthritis is to immobilize the thumb in a forearm-based, thumb immobilization splint with the wrist in 20 to 30 degrees of extension, the CMC joint in 45 degrees of palmar abduction (if tolerated), and the MCP joint in 0 to 5 degrees of flexion [Tenney and Lisak 1986]. This splint is classified by ASHT as a wrist extension, thumb CMC palmar abduction and MP extension immobilization splint [ASHT 1992]. Resting the hand in this position is extremely beneficial during periods of inflammation, or if the thumb is unstable at the CMC joint [Marx 1992]. Incorporating the wrist in a forearm-based thumb splint is appropriate when the client’s wrist is painful or if there is also arthritis involvement.

Some persons with rheumatoid arthritis affecting the CMC joint benefit from a hand-based thumb immobilization splint (thumb CMC palmar abduction immobilization splint) [ASHT 1992], as shown inFigure 8-8 [Melvin 1989, Colditz 1990]. Positioning the thumb in enough palmar abduction for functional activities is important. With a hand-based thumb immobilization splint, if the IP joint is painful and inflamed the therapist should incorporate the IP joint into the splint. However, putting any material (especially plastic) over the thumb pad will virtually eliminate thumb and hand function. The person wears this splint constantly for a minimum of 2 to 3 weeks, with removal for hygiene and exercise. The therapist adjusts the wearing schedule according to the person’s pain and inflammation levels.

Figure 8-8 A hand-based thumb immobilization splint (thumb CMC palmar abduction immobilization splint).

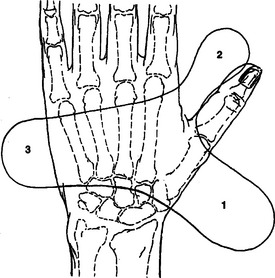

On the other hand, some therapists stabilize the thumb CMC joint alone with a short splint that is properly molded and positioned (Figures 8-9 and 8-10). This splint works effectively on people who have CMC joint subluxation resulting in adduction of the first MP joint and anyone with CMC arthritis who can tolerate wearing a rigid splint. This splint can be also used for CMC osteoarthritis, discussed in more detail later in this chapter [Colditz 2000, 2002].

Figure 8-9 A splint for rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis that stabilizes only the CMC joint. [From Colditz JC (2002). Anatomic considerations for splinting the thumb. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Skirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, pp.1858-1874.]

Figure 8-10 A pattern for a thumb cmc immobilization splint. [From Colditz JC (2000). The biomechanics of a thumb carpometacarpal immobilization splint: Design and fitting. Journal of Hand Therapy 13(3):228-235.]

Often when a physician refers a person who has rheumatoid arthritis for splinting, deformities have already developed. If the therapist attempts to place the person’s joints in the ideal position of 40 to 45 degrees of palmar abduction, excessive stress on the joints may result. The therapist should always splint a hand affected by arthritis in a position of comfort [Colditz 1984].

When fabricating a splint on a person who has rheumatoid arthritis, the therapist should be aware that the person may have fragile skin. The therapist should monitor all areas that can cause skin breakdown, including the ulnar head, Lister’s tubercle, the radial styloid along the radial border, the CMC joint of the thumb, and the scaphoid and pisiform bones on the volar surface of the wrist [Dell and Dell 1996]. Padding the splint for comfort to prevent skin irritation may be necessary.

The selected splinting material should be easily adjustable to accommodate changes in swelling and repositioning as the disease progresses. Asking persons about their swelling patterns is important because splints fabricated during the day should allow enough room for nocturnal swelling. Thermoplastic material less than  -inch thick is best for small hand splints. Splints fabricated from heavier splinting material have the potential to irritate other joints [Melvin 1989]. Therapists must carefully evaluate all hand splints for potential stress on other joints and should instruct persons to wear the splints at night, periodically during the day, and during stressful daily activities. However, therapists should always tailor any splint-wearing regimen for each person’s therapeutic needs.

-inch thick is best for small hand splints. Splints fabricated from heavier splinting material have the potential to irritate other joints [Melvin 1989]. Therapists must carefully evaluate all hand splints for potential stress on other joints and should instruct persons to wear the splints at night, periodically during the day, and during stressful daily activities. However, therapists should always tailor any splint-wearing regimen for each person’s therapeutic needs.

CMC joint osteoarthritis is a common thumb condition, especially among women over 40 [Zelouf and Posner 1995, Melvin 1989]. Pain from osteoarthritis at the base of the thumb interferes with the person’s ability to engage in normal functional activities as the CMC joint is the most critical joint of the thumb for function [Chaisson and McAlindon 1997, Neumann and Bielefeld 2003]. Precipitating factors include hypermobility, repetitive grasping, pinching, use of vibratory tools, and a family history of the condition [Winzeler and Rosenstein 1996, Melvin 1989].

Over time, the dorsal aspect of the CMC joint is stressed by repetitive pinching and the strong muscle pull of the adductor pollicis muscle and the short intrinsic thumb muscles. Altogether, these forces may cause the first CMC joint to sublux dorsally and radially. This typically results in the first metacarpal losing extension and becoming adducted. The MCP joint hyperextends to accommodate grasp [personal communication, J. C. Colditz, April 1995; Melvin 1989; personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, June 2006].

Splinting for CMC joint arthritis helps to manage pain, provides stability for intrinsic weakness of the capsular structures, and preserves the first web space. In addition, splinting helps with inflammation control, joint protection, and maintaining function [Poole and Pellegrini 2000, Neumann and Bielefeld 2003]. Static splinting is recommended for hypermobile or unstable joints but not for fixed joints [Neumann and Bielefeld 2003]. There are many options for splint design, ranging from forearm splints (with the CMC and MCP joints included) to hand-based splints (with the CMC and MCP joints included, or only the CMC joint included). With any selected design, the thumb is generally positioned in palmar abduction [Neumann and Bielefeld 2003]. Based on cadaver research, people with a hypermobile MCP joint who are positioned with the thumb in 30 degrees of flexion experience reduced pressure on the palmar part of the trapeziometacarpal joint, an area prone to deterioration [Moulton et al. 2001].

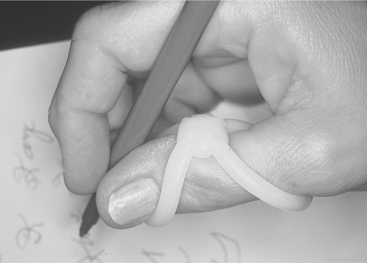

Melvin [1989] suggested fabricating a hand-based thumb immobilization splint (thumb CMC palmar abduction immobilization splint,Figure 8-8) [ASHT 1992], with the primary therapeutic goal of restricting the mobility of thumb joints to decrease pain and inflammation. The splint stabilizes the CMC and MCP joints in the maximal amount of palmar abduction that is comfortable for the person and allows for a functional pinch. Splinting both joints in a thumb post stabilizes the CMC joint in abduction so that the base of the MCP is stabilized. With the splint on, the person should continue to perform complete functional tasks, such as writing, comfortably. This thumb immobilization splint may be fabricated from a thin (1/16-inch) conforming thermoplastic material.

As discussed, another splinting option for CMC osteoarthritis designed by Colditz [2000] is a hand-based splint that allows for free motion of the thumb MCP joint and stabilizes the CMC joint to manage pain (Figures 8-9 and 8-10). The wrist is not included in the splint’s design to allow for functional wrist motions. Colditz suggested an initial full-time wear of 2 to 3 weeks with removal for hygiene. Afterward, the splint should be worn during painful functional activities [Colditz 2000].

Therapists should fabricate this splint only on hands that have “a healthy MP joint” because the MP joint may sustain additional flexion pressure due to the controlled flexion position of the CMC joint [Melvin 2002, p. 1652]. Therapists must be attentive to wear on the MP joint [Neuman and Bielefeld 2003]. Prefabricated splints can also be considered for CMC osteoarthritis. However, prefabricated splints should be used with caution because positioning the thumb in abduction within the splint can increase MP joint extension, which can worsen a possible deformity [Biese 2002].

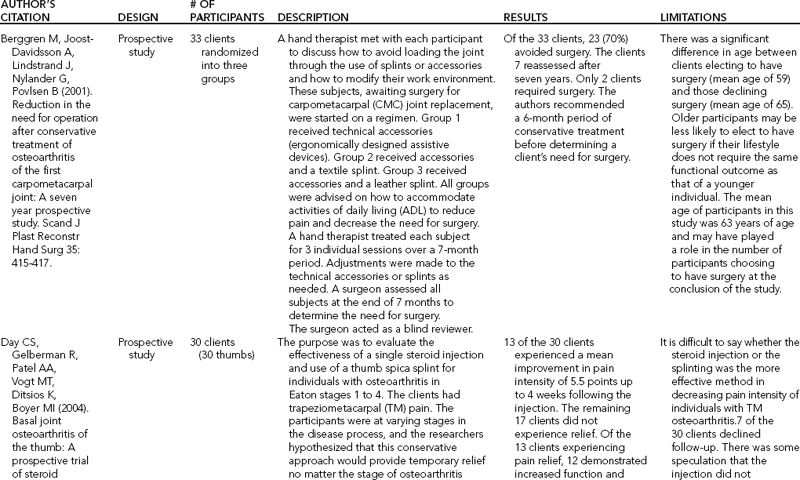

Given the variety of splinting options available, therapists critically analyze which splint to provide (forearm based or hand based) and which thumb joints to immobilize. Critical thinking considerations include presence of pain, need for stability, work, and functional demands. Researchers offer some guidance. Weiss et al. [2000] compared providing a long thumb immobilization splint with the MCP joint included to a hand-based splint with only the CMC joint included. In this 2-week study (n = 26), both splints were applied to individuals in grades 1 through 4 of CMC osteoarthritis as rated by Eaton and Littler [1973]. Both splints were found to be effective for pain control with all grades of the disease. However, the splints were only effective in reducing subluxation of the CMC joint for subjects in the earlier stages (grades 1 and 2) of the disease.

Subjects in the later stages of the disease (grades 3 and 4) preferred the short splint and reported pain relief with splint wear. Subjects in grades 1 and 2 slightly preferred the long splint (56%). Neither splint increased pinch strength nor changed pain levels when completing pinch strength measurements. Activities of daily living (ADL) improved with the short splint (93%) compared to (44%) with the long splint. Subjects reported that ADL were more difficult to complete with the long splint [Weiss et al. 2000].

Swigart et al. [1999] retrospectively researched (n = 114) the application of a custom long thumb immobilization splint with CMC osteoarthritis and found it to be a beneficial conservative treatment. Overall, subjects (regardless of disease stage) benefited from splinting (with a “60% improvement rate after splinting and 59% 6 months later” [Swigart et al. 1999, p. 90]). Some subjects were not able to tolerate the long splint because it felt too confining and uncomfortable. Day et al. [2004] studied splinting and steroid injections for people with thumb osteoarthritis and found that people in the earlier stages of the disease showed good improvement with conservative measures.

Splinting for Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injury

Acute or chronic injury to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL), a condition also known as gamekeeper’s thumb or skier’s thumb, is a common injury that can occur at the MCP joint of the thumb [Landsman et al. 1995]. Gamekeeper’s thumb was the original name of the injury because gamekeepers stressed this joint when they killed birds by twisting their necks [Colditz 2002].

The UCL helps stabilize the thumb by resisting radial stresses across the MCP joint [Winzeler and Rosenstein 1996]. The UCL can be injured if the thumb is forcibly abducted or hyperextended. This can occur from falling with an outstretched hand and the thumb in abduction, as during skiing [Winzeler and Rosenstein 1996]. It can also occur in basketball, gymnastics, rugby, volleyball, hockey, and football [Fess et al. 2005].

Treatment protocols depend on the extent of ligamental tear. There are protocols that involve immediate postoperative motion, and thus duration of casting postoperatively varies widely. Injuries are classified by the physician as grade I, II, or III [Wright and Rettig 1995]. The following is one of many suggested splinting protocols for each grade of injury. This splinting protocol is accompanied by hand therapy [Wright and Rettig 1995]. Grade I injuries, or those involving microscopic tears with no loss of ligament integrity, are positioned in a hand-based thumb immobilization splint with the CMC joint of the thumb in 40 degrees of palmar abduction (or in the most comfortable amount of palmar abduction).

This splint is also called a thumb MP radial and ulnar deviation restriction splint [ASHT 1992]. The purpose of this splint is to provide rest and protection during the healing phase. The person wears the splint continuously for 2 to 3 weeks, with removal for hygiene purposes. Grade II injuries involve a partial ligament tear, but the overall integrity of the ligament remains intact. The splinting protocol is the same as for grade I injuries, except that the thumb immobilization splint is worn for a longer time period (up to 4 or 5 weeks). Grade III injuries involve a completely torn ligament and usually require surgery.

After the person is casted, the cast is replaced by a thumb immobilization splint with the same protocol as described for grade I injuries. There is some recent evidence that a complete rupture may be managed conservatively with a thumb immobilization splint [Landsman et al. 1995]. If the UCL is still in an anatomic position, a thumb immobilization splint fabricated with the thumb in neutral with respect to flexion/extension and in maximum tolerated ulnar deviation worn consistently will heal the tear. The positioning will approximate the ends of the UCL and allow it to scar together. The physician and the therapist must assess whether the person is reliable enough to follow through with the splint. If there is any doubt, the person should be casted so that ligament protection is ensured [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, 1999].

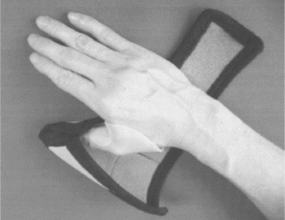

A unique “hybrid” splint was designed for athletes with a UCL injury who require splinting for protection during sports activities [Ford et al. 2004]. This splint design is a custom-made circumferential thermoplastic splint molded around the MCP joint, which is held in place by a fabricated neoprene wrap. The advantage of this splint design is that it provides MCP stability with the thermoplastic insert and allows for movement of other joints because of the neoprene stretch. In addition, this splint helps control pain and allows for activities involving grip and pinch (Figure 8-11). Therapists could either fabricate both parts of this splint or fabricate the circumferential splint and purchase a prefabricated neoprene thumb wrap. For those who return to skiing soon after a UCL injury, researchers suggest fabricating a small thermoplastic splint held in place with tape inside a ski glove [Alexy and De Carlo 1998].

Figure 8-11 A protective splint for a UCL injury that combines a custom-made circumferential thermoplastic splint molded around the MCP joint, which is held in place by a fabricated neoprene wrap. [From Ford M, McKee P, Szilagyi M (2004). A hybrid thermoplastic and neoprene thumb metacarpophalangeal joint orthosis. Journal of Hand Therapy 17(1):64-68.]

Finally, as with any therapeutic intervention, success is dependent on many factors (such as carefully following therapeutic protocols and good surgery techniques). Zeman et al. [1998] (n= 58) found that a new suture technique for grade III (complete rupture) of the UCL combined with splinting post-surgery resulted in a high success rate of return to functional activities (98%), especially those activities difficult to perform pre-surgery.

A radial collateral ligament (RCL) injury (or “golfer’s thumb”) is an injury that occurs less commonly than UCL [Campbell and Wilson 2002] and requires a hand-based thumb immobilization splint. The splint is almost the same as for a UCL injury, except that the thumb is positioned in maximal comfortable radial deviation at the MCP joint. This splint helps remove stress to the healing ligament. The golfer who has injured a thumb and wants to return to the sport may find it difficult to play in a rigid splint. Rather than wearing a rigid splint during play, the person can be weaned from the splint in the same time as required for a UCL injury. The client learns how to wrap the thumb, which will be necessary for at least a year post injury [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, 1999], or purchases a soft prefabricated splint.

Splinting for Scaphoid Fractures

Fracture of the scaphoid bone is the second most common wrist fracture [Cailliet 1994]. Similar to Colles’ fracture, scaphoid fractures usually occur because of a fall on an outstretched hand with the wrist dorsiflexed more than 90 degrees [Geissler 2001] and are a consequence of strong forces to the wrist [Cooney 2003]. Scaphoid fractures happen with impact sports, such as basketball, football, and soccer [Riester et al. 1985, Werner and Plancher 1998, Geissler 2001]. Clinically, persons who have a scaphoid fracture present with painful wrist movements and tenderness on palpation of the scaphoid in the anatomical snuffbox between the EPL and the EPB [Cailliet 1994].

Physicians cast the arm and, after the immobilization stage, the hand may be positioned in a splint. This splint may be a volar forearm-based thumb immobilization splint [Cooney 2003] with the thumb in a position for function so that it lightly contacts the index and middle finger pads (0 to 10 degrees flexion) and with the wrist in neutral [Cannon 1991, Wright and Rettig 1995, Fess et al. 2005].

Some clients (especially those in noncontact competitive sports) may benefit from a combination dorsal/volar thumb splint for added stability, protection, and pain and edema control [Fess et al. 2005] (Figure 8-12). Therapists should educate clients that proximal scaphoid fractures take longer to heal, sometimes up to months, because of a poor vascular supply [Rettig et al. 1998, Fess et al. 2005]. For people who play sports and have a healing scaphoid fracture, a soft commercial thumb immobilization splint may also be recommended as a prevention measure [Geissler 2001].

Fabrication of a Thumb Immobilization Splint

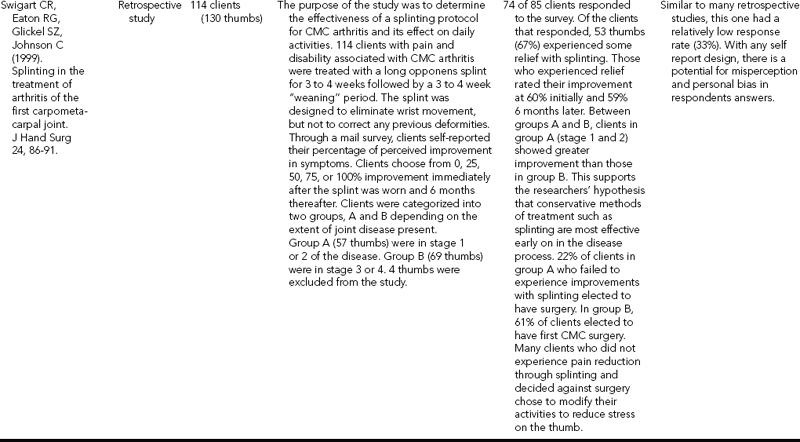

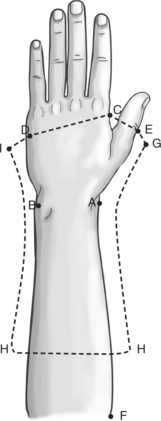

There are many approaches to fabrication of a thumb immobilization splint.Figure 8-13 shows a detailed pattern that can be used for either a volar or dorsal thumb immobilization splint. The thumb immobilization splint radial design [ASHT 1992] provides support on the radial side of the hand while stabilizing the thumb. This design allows some wrist flexion and extension but limits deviation [Melvin 1989]. The therapist usually places the thumb in a palmar abducted position so that the thumb pad can contact the index pad. The therapist leaves the IP joint free for functional movement but can adapt the splint pattern to include the IP joint if more support becomes necessary. The thumb can be placed in a position of comfort (i.e., out of the functional plane) if the client does not tolerate the thumb placed in the functional position or when the physician does not want the thumb to incur any stress.

Figure 8-14 shows a detailed radial gutter thumb immobilization pattern that excludes the IP joint. (SeeFigure 8-3 for a picture of the completed splint product.)

1. Position the forearm and hand palm down on a piece of paper. The fingers should be in a natural resting position and slightly abducted; the wrist should be neutral with respect to deviation. Draw an outline of the hand and forearm to the elbow. As you gain experience with pattern drawing, you will not need to draw the entire hand and forearm outline. The experienced therapist can estimate the placement of key points on the pattern.

2. While the person’s hand is on the paper, mark an A at the radial styloid and a B at the ulnar styloid. Mark the second and fifth metacarpal heads C and D, respectively. Mark the IP joint of the thumb E, and mark the olecranon process of the elbow F. Then remove the person’s hand from the paper pattern.

3. Place an X two-thirds the length of the forearm on each side. Place another X on each side of the pattern approximately 1 to ½inches outside and parallel to the two X markings for two-thirds the length of the forearm. Mark these two Xs H.

4. Draw an angled line connecting the second and fifth metacarpal heads (C to D). Extend this line approximately 1 to ½inches to the ulnar side of the hand and mark it I.

5. Connect C to E. Extend this line approximately ½ to 1 inch. Mark the end of the line G.

6. Draw a line from G down the radial side of the forearm, making sure the line follows the size of the forearm. To ensure that the splint is two-thirds the length of the forearm, end the line at H.

7. Begin a line from I and extend it down the ulnar side of the forearm, making certain that the line follows the increasing size of the forearm. End the line at H.

8. For the proximal edge of the splint, draw a straight line that connects both Hs.

9. Make sure the splint pattern lines are rounded at G, I, and the two Hs.

11. Place the splint pattern on the person (Figure 8-15). Make certain the splint’s edges end mid-forearm on the volar and dorsal surfaces of the person’s hand and forearm. Check that the splint is two-thirds the forearm length and one-half the forearm circumference. Check the thumb position and make any necessary adjustments (e.g., additions, deletions) on the splint pattern.

12. Carefully trace with a pencil the thumb immobilization splint pattern on a sheet of thermoplastic material.

13. Heat the thermoplastic material.

14. Cut the pattern out of the thermoplastic material.

15. Reheat the material, mold the form onto the person’s hand, and make necessary adjustments. Make sure the thumb is correctly positioned as the material hardens by having the person lightly touch the thumb tip to the pads of the index or middle fingers. Another approach is to provide light pressure over the plastic of the thumb MCP joint to align it in palmar abduction (Figures 8-16 and 8-17).

Figure 8-16 Have person lightly touch the thumb tip to the pads of the index and middle fingers to position the thumb in palmar abduction.

Figure 8-17 Although the actual movement comes from the CMC joint, provide light pressure on the thumb MCP joint to position the thumb correctly in palmar abduction.

16. Add three 2-inch straps (one at the wrist joint, one towards the proximal end of the forearm trough, and one across the dorsal aspect of the hand) connecting the hypothenar bar to the metacarpal bar.

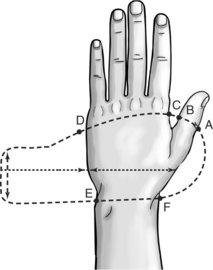

Fabrication of a Hand-Based Thumb Immobilization Splint

Hand-based thumb immobilization splints can be fabricated for people who have the following diagnoses: low median nerve injury, ulnar or radial collateral ligament injury of the MCP joint, osteoarthritis, and the potential for a first web space contracture. Each of these diagnoses may require placement of the thumb post in a different degree of abduction, based on protocols. With this splint, the IP joint is usually left free for functional movement, unless there is extreme pain in that joint. However, if the IP joint is left free (especially during rigorous activity) it too can become vulnerable to stresses. This hand-based splint design is most appropriate for stabilizing the MP joint because the position of the CMC is irrelevant. Finally, because this hand-based splint design incorporates the dorsal aspect of the palm, the therapist may need to add padding since the dorsal skin has a minimal subcutaneous layer and the boniness of the dorsal palm can cause skin breakdown.

Figure 8-18 shows a detailed hand-based thumb immobilization pattern. (SeeFigure 8-8 for a picture of the completed splint product.)

1. Position the person’s forearm and hand palm down on a piece of paper. Ensure that the client’s thumb is radially abducted. The fingers should be in a natural resting position and slightly abducted. Draw an outline of the hand, including the wrist and a couple of inches of the forearm.

2. While the person’s hand is on the paper, mark the IP joint of the thumb on both sides and label it A (radial side of thumb) and B (ulnar side of the thumb), respectively. Then mark the second and fifth metacarpal heads C and D, respectively. Mark the wrist joint on the ulnar side of the hand E, and mark F on the radial side of the wrist. Remove the hand from the pattern.

3. Draw an angled line connecting the marks of the second and fifth metacarpal heads (D to C). Then connect C to B and B to A. Curve the line around and angle it down to F. Connect F to E. Then extend the line out from E approximately equal to the length of the pattern on the hand. Go up vertically and curve the line around and connect it to D. Make sure that all edges on this pattern are rounded.

4. Cut out the pattern, check fit, and make any adjustments. Make sure the pattern allows enough room for an adequately fitting thumb post.

5. Position the person’s upper extremity with the elbow resting on the table and the forearm in a neutral position.

6. Trace the pattern onto a sheet of thermoplastic material.

7. Heat the thermoplastic material.

8. Cut the pattern out of the thermoplastic material.

9. Measure the CMC joint to make sure it is in the correct position.

10. Reheat the thermoplastic material.

11. Mold the splint onto the person’s hand. First form the thumb post around the thenar area. Make sure the thumb is correctly positioned as the material hardens. Allowances are made in the circumference of the thumb post to ensure that the client can move the thumb. This is particularly important when fabricating a splint from thermoplastic material that shrinks or has memory. Roll the volar part of the thumb post proximal to the thumb IP crease to allow adequate IP flexion. Then form the splint across the dorsal side of the hand from the thumb (radial side) to the ulnar side. Curving around the ulnar side, fit the splint material proximal to the distal palmar crease on the volar side of the hand. There will be just enough room between the thumb post and the end of the splint on the ulnar side to add a strap across the palm. Make sure the proximal end of the splint is flared.

12. After the thermoplastic material has hardened, check that the person can perform IP thumb flexion without impingement by the thumb post and that he or she can perform all wrist movements without interference by the proximal end of the splint. Make adjustments as necessary.

Technical Tips for Proper Fit

1. Before molding the splint, place the person’s elbow on a tabletop, positioned in 90 degrees of flexion and the forearm in a neutral position. Position the thumb and wrist according to diagnostic indications.

2. Monitor joint positions by measuring during and after splint fabrication. A common mistake when splinting is incorrect placement of the thumb in a midposition between palmar abduction and radial abduction when the diagnostic protocol calls for palmar abduction. The best way to position the thumb in palmar abduction for fabrication of a splint is to have the person lightly touch the thumb tip to the pad of the index or middle finger. However, there will be some persons (for example, a person who has rheumatoid arthritis) who will find the thumb post more comfortable between radial and palmar abduction.

3. Follow the natural curves of the longitudinal, distal, and proximal arches. Position the splint area that covers the thenar eminence just proximal to the proximal palmar crease. Be especially careful to check that the index finger has full flexion because of its close proximity to the opponens bar, C bar, and thumb post.

4. When molding the thumb post, overlap the splinting material into the thumb web space (Figure 8-19). Be certain the thumb IP joint remains in extension during molding to facilitate later splint application and removal. Be extremely careful in making adjustments with a heat gun on the thumb post, or the result may be an inappropriate fit.

5. When applying thermoplastic material that shrinks during cooling and because the thumb is circumferential in shape, allowances must be made to ensure easy application and removal of the splint. There are several options to address this issue. One is to have the person make very small thumb circles as the plastic cools because this motion allows for some extra room [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, June 2006]. Another option is to gently flare the thumb post with a narrow pencil [McKee and Morgan 1998].

6. A thumb post can be fabricated with overlapping material that does not bond. This design method allows for adjustment to expand or contract the thumb post with the velcro straps that secure the post [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, June 2006].

7. For a thumb immobilization splint that allows IP mobility, make sure the distal end of the thumb post on the volar surface has been rolled to allow full IP flexion (Figure 8-20).

8. Concentrate during splint fabrication on the thenar area. Note several areas prior to hardening of the thermoplastic material. Check that the thumb post is not too loose and provides adequate support for the thumb joints. The thumb post should also provide enough room for ease of donning and doffing of the splint. Check that the distal end of the thumb post is just proximal to the MP joint and has not migrated lower. Check that the forearm trough is correctly placed in mid-forearm. Make sure that the splint does not interfere with functional hand movements.

Precautions for a Thumb Immobilization Splint

The cautious splintmaker checks for areas of skin pressure over the distal ulna, the superficial branch of the radial nerve at the radial styloid, and the volar and dorsal surfaces of the thumb MCP joint. Specific precautions for the molding of the splint include the following:

• If the thumb post extends too far distally on the volar surface of the IP joint, the result is restriction of the IP joint flexion and a likely area for skin irritation.

• Because of its close proximity to the opponens bar, C bar, and thumb post, the radial base of the first metacarpal and first web space has a potential for skin irritation.

• With a radial gutter splint, monitor the splint for a pressure area at the midline of the forearm on the volar and dorsal surfaces. Pull the sides of the forearm trough apart if it is too tight.

• Be careful to fabricate a thumb splint that is supportive and not too constrictive. Constriction results in decreased circulation and possible skin breakdown. Make allowances for edema when fabricating the thumb post.

• If using a thermoplastic material that has memory properties, be aware that the material shrinks when cooling. Therefore, the thumb post opening must remain large enough for comfortable application and removal of the splint.

Impact on Occupations

Having a workable thumb for grasp and pinch is paramount for functional activities. Research findings support the thumb’s functional importance. Swigart et al. [1999] established that people with CMC arthritis had decreased involvement in crafts and changed their athletic involvement. With gamekeeper’s thumb, lack of thenar strength and adequate pinch can impact daily functional activities such as turning a key or opening a jar [Zeman et al. 1998].

Even with the stability provided by a splint, some people may find it more difficult to perform meaningful occupations. For example, Weiss et al. [2000] found in their study (n= 25) that with some subjects, the long thumb immobilization splint inhibited function and was more than necessary to meet therapeutic goals. Therefore, the goal of splinting is to improve function. It is intended that with the benefits of splint wear and a therapeutic program the person will return to meaningful activities [Zeman et al. 1998].

Prefabricated Splints

Deciding to furnish a prefabricated thumb splint requires careful reflection. Therapists should critically consider the condition, for which the splint is being provided, materials that the splint is made out of as well as design and comfort factors. Furthermore, therapists should review the literature to determine whether a custom thumb splint is preferable over a prefabricated thumb splint to treat a condition.

Conditions

Prefabricated thumb splints are manufactured for a variety of conditions, including arthritis, thumb MP collateral ligament injuries, de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, and hypertonicity. Splint types and positions for all these conditions have been discussed in this chapter (seeTable 8-1).

Materials

Therapists should be aware of the characteristics of the wide variety of materials available for prefabricated thumb splints. Material firmness varies from soft to rigid. Soft materials are often used with thumb splinting because they can be easier to apply and provide a more comfortable fit for a client with a painful and edematous thumb IP joint than a rigid splint. A commonly used soft material with prefabricated splints is neoprene. It has the advantage of providing hugging support with flexibility for function, but it has the disadvantage of retaining moisture next to the skin. Another soft material used in prefabricated splints is leather. Splints made of leather absorb perspiration and are pliable; however, they often become odiferous and soiled. Some splints are lined with moisture wicking material or are fabricated from perforated material to address this issue.

Examples of prefabricated splints made out of rigid materials are those fabricated out of thermoplastic, vinyl, or adjustable polypropylene materials.

An awareness of the splint’s function, condition for which it is being used, and the client’s occupational demands can help the therapist critically determine the degree of material firmness to use. A prefabricated splint made out of a rigid material might be very appropriate to supply to a client for sports, heavier work activities, or for any condition that requires a higher amount of support and protection. Finally, people who are allergic to latex will require splints made from latex-free materials.

Design and Comfort

Similar to fabricated thumb splints prefabricated splints are either hand based or forearm based. The hand-based thumb immobilization designs provide support to the thumb joints through the circumferential thumb post component, thermoplastic material, or optional stays. The forearm-based immobilization designs derive some of their support from a longer lever arm. Prefabricated forearm-based splints contain many features which should be critically considered for client usage. Examples of these features are adjustable or additional straps and adjustable thumb stays to provide optimal support and fit. Some designs for both the forearm- and hand-based splints are hybrid designs. These splints usually have a softer outer layer with removable and adjustable inserts made out of thermoplastic material to customize the fit of the splint.

Another consideration is the comfort of the pre-fabricated thumb splint. Factors to think about are adjustability, temperature, bulkiness, and padding of the possible splint selection. When adjusting the splint therapists should take into account the number and location of strap and types of strapping material to obtain an appropriate fit. For example, with a long thumb splint the therapist should consider whether the wrist straps provide adequate support. With temperature the type of splinting material that is used for the prefabricated splint is taken into account as some materials are more breathable than others. Thumb splints made out of neoprene or other soft materials are usually more breathable than rigid splinting materials. A prefabricated splint made out of a breathable material might be a consideration for a person living or working in a hot environment. A person with arthritis might prefer a thumb splint that provides warmth. Padding may be an essential consideration with a person who has a tendency towards skin breakdown. Thumb immobilization splints may chafe the web space, so the therapist must monitor for fit and consider padding in that area. Some prefabricated thumb immobilization designs include added features, such as a gel pad for scar control or leather for added durability.Figures 8-2A through F outline prefabricated thumb splint options.

Summary

Thumb splinting is commonly provided in clinical practice. Applying a critical analysis approach will help with thumb splinting. It behooves therapists to be aware of the appropriate splints (whether fabricated or prefarbricated) to provide clients splints based on conditions and occupational needs.

| THERAPEUTIC OBJECTIVE | DESCRIPTION |

| Prefabricated thumb immobilization splints provide rest to inflamed, injured, and painful thumb joints. | Thumb immobilization splints are available in low-temperature thermoplastic and soft materials (leather, neoprene) to support thumb joints (Figure 8-21, A through C. Some thumb splints contain extra layers, which can add warmth (Figure 8-21D). Others can be customized for the client (Figure 8-21E). Thumb loops can be used for hypertonicity (Figure 8-21F). Pre-thumb immobilization splints are available in different sizes, hand or forearm bases, radial or palmar based, and provide radial or palmar thumb abduction. |

Figure 8-21 (A) This thermoplastic splint supports the MP and CMC joints. (B) Thumb splint is made from leather. (C) This Comfort Cool Wrist and Thumb CMC Restriction Splint is made out of perforated neoprene, which keeps the extremity cool. It has additional strapping at the wrist to allow for extra support. (D) This Rolyan Preferred 1st thumb splint can be used with a person who has arthritis as it contains extra layers to help wick moisture from the skin, retain body warmth, and provide heat. (E) This Roylan Gel Shell thumb spica splint contains a gel shell Rolyan pad that helps with scar formation and hypersensitivity. It also contains a moldable thermoplastic stay that can be adjusted along the radial side of the hand. (F) This Rolyan thumb loop is latex free and positions the thumb to decrease tone and facilitate function. (A) [ThumSaver MP; courtesy 3-Point Products, Stevensville, Maryland.] (B) [Collum CMC Thumb Brace; courtesy Adaptive Abilities, Oroville, WA.] (C) [Courtesy Sammons Preston Rolyan, Bollington, IL.] (D) [Courtesy Sammons Preston Rolyan, Bollington, IL.] (E) [Courtesy Sammons Preston Rolyan, Bollington, IL.] (F) [Courtesy Sammons Preston Rolyan, Bollington, IL.]

1. What are the general reasons for provision of a thumb immobilization splint?

2. What are some of the clinical indications for including the IP joint of the thumb in a thumb immobilization splint?

3. What is a proper wearing schedule for a person with rheumatoid arthritis who wears a thumb immobilization splint?

4. What is the suggested position for a thumb splint for a person who has CMC joint arthritis? What joints are splinted?

5. Which type of thumb immobilization splint should a therapist fabricate for a person who has de Quervain’s tenosynovitis?

6. What is some of the research evidence for splinting for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis?

7. Which type of thumb immobilization splint should a therapist fabricate for an injury of the thumb ulnar collateral ligament?

8. What is the splint-wearing schedule for each grade of ulnar collateral ligament injury?

References

Alexy, C, De Carlo, M. Rehabilitation and use of protective devices in hand and wrist injuries. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 1998;17(3):635–655.

American Society of Hand Therapists. Splint Classification System. Garner, NC: American Society of Hand Therapists, 1992.

Avci, S, Yilmaz, C, Sayli, U. Comparision of nonsurgical treatment measures for de Quervain’s disease of pregnancy and lactation. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2002;27A(2):322–324.

Belkin, J, English, C. Hand splinting: Principles, practice, and decision making. In: Pedretti LW, ed. Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction. Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:319–343.

Biese, J. Short splints: Indications and techniques. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1846–1857.

Cailliet, R. Hand Pain and Impairment. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1994.

Campbell, PJ, Wilson, RL. Management of joint injuries and intraarticular fractures. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:396–411.

Cannon, NM. Diagnosis and Treatment Manual for Physicians and Therapists, Third Edition. Indianapolis: The Hand Rehabilitation Center of Indiana, 1991.

Cannon, NM, Foltz, RW, Koepfer, JM, Lauck, MR, Simpson, DM, Bromley, RS. Manual of Hand Splinting. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1985.

Chaisson, C, McAlindon, TS. Osteoarthritis of the hand: Clinical features and management. The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 1997;14:66–68. [71-74, 77].

Colditz, JC. Anatomic considerations for splinting the thumb. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1858–1874.

Colditz, JC. Arthritis. In: Malick MH, Kasch MC, eds. Manual on Management of Specific Hand Problems. Pittsburgh: AREN Publications; 1984:112–136.

Colditz, JC. The biomechanics of a thumb carpometacarpal immobilization splint: Design and fitting. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2000;13(3):228–235.

Cooney, WP, III. Scaphoid fractures: Current treatments and techniques. Instructional Course Lectures. 2003;52:197–208.

Day, CS, Gelberman, R, Patel, AA, Vogt, MT, Ditsios, K, Boyer, MI. Basal joint osteoarthritis of the thumb: A prospective trial of steroid injection and splinting. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2004;29A(2):247–251.

Dell, PC, Dell, RB. Management of rheumatoid arthritis of the wrist. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1996;9(2):157–164.

Eaton, RG, Littler, W. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1973;55A:1655–1666.

Fess, EE, Gettle, KS, Philips, CA, Janson, JR. Hand Splinting Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier/Mosby, 2005.

Ford, M, McKee, P, Szilagyi, M. A hybrid thermoplastic and neoprene thumb metacarpophalangeal joint orthosis. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2004;17(1):64–68.

Geisser, RW. Splinting the rheumatoid arthritic hand. In: Ziegler EM, ed. Current Concepts in Orthosis. Germantown, WI: Rolyan Medical Products; 1984:29–49.

Geissler, WB. Carpal fractures in athletes. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 2001;20(1):167–188.

Idler, RS. Helping the patient who has wrist or hand tenosynovitis. Part 2: Managing trigger finger and de Quervain’s disease. The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 1997;14:62–65. [68, 74-75].

Landsman, JC, Seitz, WH, Froimson, AI, Leb, RB, Bachner, EJ. Splint immobilization of gamekeeper’s thumb. Orthopedics. 1995;18(12):1161–1165.

Lane, LB, Boretz, RS, Stuchin, SA. Treatment of de Quervain’s disease: Role of conservative management. Journal of Hand Surgury (Br). 2001;26(3):258–260.

Lee, MP, Nasser-Sharif, S, Zelouf, DS. Surgeon’s and therapist’s management of tendonopathies in the hand and wrist. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:931–953.

Marx, H. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Stanley BG, Tribuzi SM, eds. Concepts in Hand Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 1992:395–418.

McCarroll, JR. Overuse injuries of the upper extremity in golf. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 2001;20(3):469–479.

McKee, P, Morgan, L. Orthotics and Rehabilitation: Splinting the Hand and Body. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1998.

Melvin, JL. Rheumatic Disease in the Adult and Child, Third Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1989.

Melvin, JL. Therapist’s management of osteoarthritis in the hand. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, Hunter JM, eds. Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:99. [1646-1663].

Moulton, MJ, Parentis, MA, Kelly, MJ, Jacobs, C, Naidu, SH, Pellegrini, VD, Jr. Influence of metacarpophalangeal joint position on basal joint-loading in the thumb. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2001;83-A(5):709–716.

Nalebuff, EA. Diagnosis, classification and management of rheumatoid thumb deformities. Bulletin of the Hospital for Joint Diseases. 1968;2:119–137.

Neumann, DA, Bielefeld, T. The carpometacarpal joint of the thumb: Stability, deformity, and therapeutic intervention. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2003;33(7):386–399.

Ouellette, E. The rheumatoid hand: orthotics as preventive. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1991;21(2):65–72.

Poole, JU, Pellegrini, VD, Jr. Arthritis of the thumb basal joint complex. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2000;13(2):91–107.

Rettig, AC. Wrist and hand overuse syndromes. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 2001;20(3):591–611.

Rettig, ME, Dassa, GL, Raskin, KB, Melone, CP, Jr. Wrist fractures in the athlete: Distal radius and carpal fractures. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 1998;17(3):469–489.

Riester, JN, Baker, BE, Mosher, JF, Lowe, D. A review of scaphoid fracture healing in competitive athletes. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1985;13(3):159–161.

Swigart, CR, Eaton, RG, Glickel, SZ, Johnson, C. Splinting in the treatment of arthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1999;24A(1):86–91.

Tenney, CG, Lisak, JM. Atlas of Hand Splinting. Boston/Toronto: Little, Brown & Co, 1986.

Tubiana, R, Thomine, JM, Mackin, E. Examination of the Hand and Wrist. St. Louis: Mosby, 1996.

Weiss, AP, Akelman, E, Tabatabai, M. Treatment of de Quervain’s disease. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1994;19A(4):595–598.

Weiss, S, LaStayo, P, Mills, A, Bramlet, D. Prospective analysis of splinting the first carpometacarpal joint: An objective, subjective and radiographic assessment. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2000;13(3):218–226.

Werner, SL, Plancher, KD. Biomechanics of wrist injuries in sports. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 1998;17(3):407–420.

Wilton, JC. Hand splinting: Principles of Design and Fabrication. London: W. B. Saunders, 1997.

Winzeler, S, Rosenstein, BD. Occupational injury and illness of the thumb. American Association of Occupational Health Nurses Journal. 1996;44(10):487–492.

Witt, J, Pess, G, Gelberman, RH. Treatment of de Quervain tenosynovitis: A prospective study of the results of injection of steroids and immobilization in a splint. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1991;73-A(2):219–222.

Wright, HH, Rettig, AC. Management of common sports injuries. In: Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand. Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995:1809–1838.

Zelouf, DS, Posner, MA. Hand and wrist disorders: How to manage pain and improve function. Geriatrics. 1995;50(3):22–26. [29-31].

Zeman, C, Hunter, RE, Freeman, JR, Purnell, ML, Mastrangelo, J. Acute skier’s thumb repaired with a proximal phalanx suture anchor. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1998;26(5):644–650.