65 Infective syndromes

Key points

• Clinically distinct infective syndromes can generally be caused by several different organisms. Sometimes the specific microbial aetiology may be apparent on clinical grounds alone (e.g. several viral exanthems). More usually a systematic and hierarchical approach is necessary.

• Whether a local or generalized (systemic) process is involved, the medical history, clinical signs (especially temperature) and non-microbiological investigations (e.g. white cell count, inflammatory markers and radiological findings) are often used to determine whether infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

• In further establishing the differential diagnosis, the time course of symptoms (acute, subacute, chronic) and potential exposure of the patient to endogenous (e.g. surgery) or exogenous (e.g. travel) sources of infection are critical factors.

• Key localized infective syndromes in which a microbiological diagnosis is commonly attempted include: sore throat; lower respiratory tract infections; intestinal infections; urinary and genital tract infections; meningitis and other central nervous system infections; eye, skin, soft tissue, bone and joint infections.

• Prominent systemic and general syndromes that may demand extensive microbiological investigation include pyrexia of unknown origin, endocarditis and septicaemia.

Throughout this book, infections have been dealt with as appropriate according to the micro-organisms involved. In this chapter, the study of infection is considered by syndromes associated with the major organs in order to emphasize the variety of microbes that may attack different body systems. The subject is presented in broad outline, and the reader should refer back to earlier chapters for a more extensive account of specific themes.

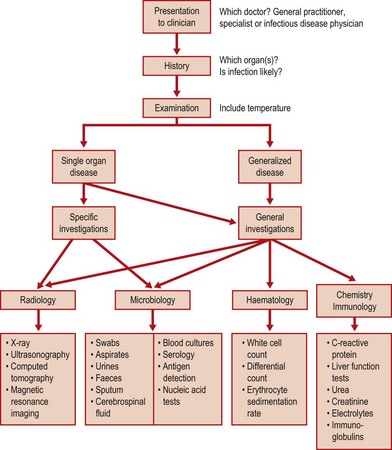

In infectious diseases, as in other branches of clinical practice, a diagnosis may be obvious and require little investigation, e.g. a case of chickenpox during an epidemic, or may be established only after laboratory and radiological examination, as with a patient with pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO). Figure 65.1 shows a flow diagram of a rational approach to diagnosis and management of a patient with infection. In practice, treatment is often started before isolating and identifying the pathogen and in many viral conditions the exact cause can only be determined during convalescence, either by serological tests or after prolonged growth in tissue culture. The availability of rapid laboratory methods and new chemotherapeutic agents has made the accurate diagnosis of infectious disease even more important.

Specific syndromes

Upper respiratory tract

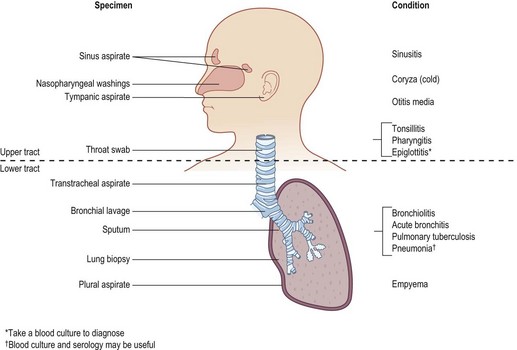

The upper respiratory tract is frequently the site of general and localized infections. Indeed, this group of ailments is amongst the most common presenting to domiciliary practice. It is the primary site of infection for most viral diseases, which are spread by sneezing, coughing or direct contact with materials contaminated by respiratory secretions. Although the majority of such symptoms are viral in origin, secondary bacterial infection may often follow, particularly in the very young and malnourished. Resident bacteria in the upper respiratory tract such as Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes and Str. pneumoniae are the most common causes. Figure 65.2 shows the anatomical sites of respiratory infection and the appropriate specimens which may be taken for microbiology.

Fig. 65.2 Microbial infections of the respiratory tract and the appropriate specimens for laboratory investigation.

Sore throat

Bacterial acute tonsillitis or pharyngitis is commonly due to Str. pyogenes (group A), and a few are caused by groups C and G. Viruses are even more common causes of sore throats, especially the milder, non-exudative forms. However, it is important to make a definitive diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis for two reasons:

1. Str. pyogenes remains sensitive to penicillin, which should be used for treatment.

2. Group A β-haemolytic streptococci, if untreated, may give rise to septic complications such as a peritonsillar abscess, or to immune complex disease (e.g. glomerulonephritis, rheumatic fever).

On the other hand, since Str. pyogenes may account for only 20% of patients presenting with typical symptoms, many courses of antibiotics would be prescribed unnecessarily if all suspected cases were treated. Even in experienced hands it is difficult to predict on clinical grounds alone which cases are streptococcal. This has led to three approaches:

1. Treat all children with a penicillin, or erythromycin if allergic. Adults are treated if the throat looks very inflamed or if there is pus on the tonsils.

2. Swabs are taken for culture of streptococci and antibiotics are started as above but stopped if Str. pyogenes is not found.

3. Swabs are taken for rapid diagnosis (by antigen detection) and penicillin commenced only if the throat swab is positive.

There are pros and cons to each method. One drawback to the early use of antibiotics is that the patient may react to the drug. If ampicillin is used, there is a strong chance of a skin reaction if the sore throat is the harbinger of glandular fever. In defence of the antibiotic lobby, there is no doubt that complications of streptococcal disease are seen far less commonly where there is access to medical service and pharmacies. However, these improvements have occurred in concert with better housing and social conditions.

There was less need to make a virological diagnosis as specific therapy was limited. However, epidemiological studies of patients with throat symptoms have revealed how common and varied are the viruses in the respiratory tract. With the advent of antivirals active against specific viruses, interest has increased in using tests for influenza and RSV.

In the severely ill child with toxaemia and a membrane, diphtheria must be considered and treatment should not await laboratory confirmation. Moreover, the laboratory needs to do special tests to isolate and identify Corynebacterium diphtheriae, and communication (by telephone, if possible) between the clinician and laboratory is essential. Other corynebacteria such as C.ulcerans and Arcanobacterium haemolyticum may rarely cause ulcerated sore throats. In the sexually active, gonococcal pharyngitis should not be missed and again the laboratory needs to be told as they will use special selective media for Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Common cold (coryza)

This common complaint, characterized by a nasal discharge (acute rhinitis) that is usually watery with scanty cells, afflicts humans of all ages who congregate together. Since there are many types of rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, adenoviruses, etc., and since immunity may be short-lived, individuals in a crowded environment, such as at school and university or travelling on public transport, may suffer three or four clinical infections a year. Most of these do not seek medical help knowing that there is little to offer. This is a condition for which many ‘alternative’ remedies are tried, from garlic to peppermint and vitamin supplements.

Bacterial superinfection with pneumococci and H. influenzae can occur in the nasopharynx but is only symptomatic when the sinuses or middle ear are involved. Pharyngitis and, occasionally, tracheobronchitis may occur with a cold or develop in more susceptible individuals. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) may cause upper respiratory symptoms in children and adults, but in those contracting the virus for the first time (usually infants under 1 year of age) acute bronchiolitis is common.

Sinusitis and otitis media

Direct extension of a viral or bacterial infection from the nasopharynx into frontal and maxillary sinuses in adults and into the middle ear in children is not uncommon. Obtaining adequate material for microbiology is difficult and requires the expertise of ear, nose and throat specialists. In most cases of acute sinusitis or otitis media the microbial cause is not found. It is assumed that severe pain and discharge of pus from the nose or ear is suggestive of bacterial infection and antibiotics are usually given to cover streptococci (mainly Str. pneumoniae) and H. influenzae. In adults with recurrent or chronic sinusitis, anaerobes (peptostreptococci or bacteroides) are often found in sinus washings.

Lower respiratory tract

Epiglottitis

Although situated in the upper part of the respiratory tract, epiglottitis behaves like a serious systemic infection which requires urgent admission to hospital and treatment. The diagnosis should be made clinically in a toxic child (usually under 5 years old) with respiratory obstruction and stridor. The most useful investigation is blood culture, which invariably grows H. influenzae type b unless antibiotics have been given or the child immunized. The epiglottis, which is swollen and cherry-red in appearance, should only be examined by skilled paediatricians prepared for a respiratory arrest. A lateral radiograph shows a soft tissue swelling in the throat.

Laryngotracheobronchitis

In adults, some viral infections cause acute laryngitis with voice loss or tracheitis with a dry cough. Respiratory tract infection in children is usually generalized and presents as croup. This may lead to respiratory obstruction and, as with haemophilus epiglottitis, urgent admission to hospital is necessary. The condition may be caused by a variety of respiratory viruses, with para-influenza viruses, adenoviruses and enteroviruses the most common. RSV can also cause croup, but more commonly this virus attacks infants in the first few months of life. In the UK there are winter epidemics of acute bronchiolitis due to RSV. This clinical syndrome which starts as a cold, followed by wheezing. In older children, asthmatic attacks are often precipitated by viral respiratory infections.

Whooping cough

Pertussis may be confused with croup, and, as special specimens need to be taken, the laboratory must be informed. A pernasal swab in special transport medium is required, and Bordetella pertussis will only grow on enriched culture media in conditions of high humidity.

Acute bronchitis

Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the most common adult lower respiratory infection. It is invariably due to pneumococci, non-encapsulated haemophili, or both. Sometimes, acute bronchitis follows a viral infection. Although often examined, expectorated sputum from ambulatory patients with COPD is almost always a waste of effort.

Cystic fibrosis patients have frequent exacerbations and, in those situations, sputum examination is valuable because the causative bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, H. influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Burkholderia cepacia) may show variable antimicrobial resistance and appropriate therapy is essential.

Acute pneumonias

It is sometimes possible on clinical and radiological grounds to distinguish between lobar pneumonia (pneumococcal), bronchopneumonia (staphylococcal and klebsiellal) and ‘atypical’ pneumonias (mycoplasmal and chlamydial). This division is of importance in guiding primary treatment, but should not give the clinician a blinkered view in investigation, as some cases will invariably not follow a textbook! Expectorated sputum is often poorly collected and may not yield the pathogen. Blood cultures should always be taken from pneumonia patients but may not yield an organism, especially if antibiotics have been started. Antigen detection in urine or sputum by fluorescent antibodies, immuno-electrophoresis, latex agglutination or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a useful method for rapid diagnosis but may lack sensitivity. New amplified DNA detection methods are likely to improve diagnostic accuracy in respiratory infections. At present most cases of ‘atypical’ pneumonia are diagnosed by obtaining acute and convalescent sera, and by finding a significant titre or a rising titre of antibodies. Legionnaires’ disease may be diagnosed by culture of Legionella pneumophila from sputum or a biopsy, but this has too low a sensitivity. Urine antigen detection by ELISA or DNA amplification of respiratory secretions have become more widely available methods of diagnosis. However, as with most pneumonias treatment must often be given on clinical suspicion.

Chronic chest disease

Tuberculosis must always be considered in any patient with fever, prolonged cough and weight loss. Again, a request for examination for mycobacteria in sputum must be included on the request card. Blood tests examining for interferon produced by peripheral lymphocytes are of value in detecting latent tuberculosis but are of limited value in diagnosis of the a ctive disease.

In the immunocompromised, various opportunist pathogens may give rise to respiratory infection. Pneumocystis carinii is demonstrated by fluorescent antibody staining of bronchial lavage. Fungal infections are diagnosed by growth of the pathogen or by serology. Special investigations are required for all these situations and unless the diagnosis is considered the laboratory cannot assist the clinician.

Gastrointestinal infection

Acute diarrhoea with or without vomiting is a common complaint. Microbial causes, either by multiplication in the intestine or from the effects of preformed toxin, are the most important reasons for acute gastrointestinal upset in an otherwise healthy individual. The aetiology of inflammatory bowel disease such as ulcerative colitis has not been established, although a patient may present with symptoms similar to an infectious diarrhoea but usually the natural history and chronicity of the condition make the distinction obvious.

Although many new causes of bowel infection have been discovered in the past 25 years the majority of food-related and short-lived episodes do not yield a microbial cause. In part this is due to the wide range of viruses, bacteria and protozoa which may be sought (Table 65.1). A search for all causes involves extensive and expensive laboratory effort, and this is often considered unnecessary for a condition which is usually self-limiting and relatively harmless.

Table 65.1 Common microbial causes of infectious intestinal disease (see individual chapters for details)

| Viruses | Bacteria | Protozoa |

|---|---|---|

ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli; SRSV, small round structured viruses; VTEC, verotoxigenic E. coli.

Toxin-mediated disease of microbial origin ranges in severity from relatively trivial episodes of food poisoning caused by:

to the life-threatening systemic diseases:

• botulism caused by Cl. botulinum

• severe pseudomembranous colitis caused by Cl. difficile (often antibiotic-associated).

There are, in addition, many non-microbial causes of food poisoning, such as that due to the ingestion of certain toadstools, undercooked red kidney beans or various types of fish (ciguatera toxin, scombrotoxin); most notorious is the puffer fish which, during part of its reproductive cycle, produces a neurotoxin that is responsible for more than 100 deaths a year in Japan, where the delicacy fugu is enjoyed.

It may be possible on clinical grounds to distinguish between patients with dysentery, in which bloody diarrhoea and mucus are found, and those with watery diarrhoea, due to the toxic effects of the pathogen on the small intestinal mucosa, leading to accumulation of fluid in the bowel. Some conditions, such as staphylococcal food poisoning and some viral illnesses, present largely with vomiting. A specific cause is also suspected if there is a history of foreign travel, if the case forms part of an outbreak that is food- or water-associated, or if the individual has a relevant food history.

Travellers’ diarrhoea encompasses many clinical and microbial causes, but the most common organisms implicated are enterotoxigenic strains of Escherichia coli (ETEC). However, a host of microbes must be considered. Some, such as salmonellae, are found worldwide; others, such as vibrios, have a more limited distribution.

More chronic intestinal infections contracted in warmer climates usually do not present with diarrhoea but with vague abdominal symptoms. Many helminths and protozoa are found on screening faeces for other pathogens.

Urinary tract infections

The diagnosis of urinary tract infection cannot be made without bacteriological examination of the urine because many patients with the frequency–dysuria syndrome have sterile urine and, conversely, asymptomatic bacteriuria is a common condition. Infection is most commonly caused by members of the Enterobacteriaceae (Table 65.2), but there are great variations in antimicrobial susceptibility, and control of chemotherapy requires laboratory examination. Occasionally, Mycobacterium tuberculosis invades the kidney and appropriate tests must be carried out if this is suspected.

Table 65.2 Common causes of urinary tract infection (approximate %)

| Organism | Domiciliary (%) | Hospital (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 70–80 | 50 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 10 | 1–5 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 1–5 | 5–10 |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | 10–15 | 0 |

| Staph. epidermidis | 1–5 | 10–20 |

| Enterococci | 1–5 | 10–20 |

| Other coliforms | <1 | 5–10 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1–2 | 5–10 |

Infection in the urinary tract may be confined to particular anatomical sites, e.g. urethritis or renal abscess. Alternatively, the urine may become infected and, in cases of obstruction or reflux, bacteria may ascend from the bladder to give rise to kidney infections. Urethritis is really a genital infection and is most commonly due to sexually transmitted organisms such as chlamydiae or N. gonorrhoeae. Confirmation depends on obtaining, by swabbing or scraping, a sample of urethral discharge for microscopy and culture. Metastatic abscesses in the kidney and perinephric abscesses cannot usually be diagnosed by urine examination, although pyuria may be present. Specific radiological or surgical exploration is necessary, as with any localized infection.

Throughout most of their lifespan women suffer far more attacks of urinary tract infection than men. In young adult women who become sexually active, frequency and dysuria are common reasons for seeking medical attention. Only about one-half of these yield an organism in ‘significant’ numbers, usually defined as above 107 organisms per litre. The most common cause by far is E. coli (Table 65.2), some strains of which possess specific uropathogenic determinants. It has been suggested that many of the culture-negative infections are due to coliforms which are present in small numbers in urine. Infection of the urine is common and may be asymptomatic in many elderly patients.

Infections of the central nervous system

Meningitis

Meningeal irritation may occur in association with other acute infections (meningism) or with non-infective conditions such as subarachnoid haemorrhage. In the early stages of meningococcal disease, signs of meningitis may be absent, yet examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) yields N. meningitidis. Thus, CSF and blood cultures should be examined from all suspected cases. There are contra-indications to performing a lumbar puncture in any patient with raised intracranial pressure because of the danger of herniation through the foramen magnum (coning). Thus, lumbar puncture should only be carried out in hospital. In fulminating disease, especially if it is meningococcal, it is prudent to give penicillin as soon as the diagnosis is suspected and before admission. This has led to a greatly reduced yield by culture of suspected cases. Antigen and DNA detection have become increasingly important in confirming the diagnosis.

It is often possible to consider the likely pathogen on clinical and epidemiological grounds. H. influenzae type b occurs almost always in infants from 6–24 months-of-age, although use of the Hib vaccine in many countries has almost made this a disease of the past. Str. pneumoniae is seen generally in the very young and the elderly. Meningococcal meningitis is characteristically a disease of children and young adults. In the neonate, coliforms (mainly E. coli K1), Listeria monocytogenes, group B streptococci and pneumococci may be found. In infants a few months old, salmonella meningitis is an important condition in some countries with a warm climate.

If no readily cultivated organism is found, but the CSF shows an increase in cells, the syndrome of aseptic meningitis is present. Table 65.3 shows some of the causes of this condition. If the symptoms are short in duration, viruses are most likely. If the child has been unwell for more than 1 week, tuberculous meningitis must be considered. This is one of the most difficult and important microbiological diagnoses to make. Interferon assays of activated lymphocytes from peripheral blood of patients with tuberculosis have been shown to be a useful adjunct to the clinical diagnosis in such situations.

Table 65.3 Causes of aseptic meningitis

| Viruses | Enteroviruses (echoviruses, polioviruses, coxsackieviruses) |

| Mumps (including post-immunization) | |

| Herpes (herpes simplex and varicella-zoster) | |

| Arboviruses | |

| Spiral bacteria | Syphilis (Treponema pallidum) |

| Leptospira (Leptospira canicola) | |

| Other bacteria | Partially treated with antibiotics |

| Tuberculous (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) | |

| Brain abscess | |

| Fungi | Cryptococcus neoformans |

| Protozoa | Acanthamoeba, Naegleria, Toxoplasma gondii |

| Non-infective | Lymphomas, leukaemias |

| Metastatic and primary neoplasms | |

| Collagen-vascular diseases |

In the immunocompromised, listeria meningitis may be seen in the adult and Cryptococcus neoformans in all age groups, but particularly those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Central nervous system disease in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a very complicated differential diagnosis (Table 65.4).

Table 65.4 Causes of neurological damage in HIV-infected patients

| Direct HIV infection | Subacute encephalomyelitis (AIDS-dementia complex) |

|---|---|

| Opportunist infections | |

| Viruses | Cytomegalovirus |

| Herpes simplex | |

| Varicella-zoster | |

| Papovavirus | |

| Bacteria | Treponema pallidum (syphilis) |

| Fungi | Cryptococcus neoformans |

| Protozoa | Toxoplasma gondii |

| Malignancy | |

| Primary | Brain lymphoma |

| Secondary | Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Systemic lymphoma | |

Cerebral infections

Encephalitis may extend into the meninges with signs and CSF findings of an aseptic meningitis. Many viral infections may, however, only infect the brain cortex and clinical symptoms may be vague: loss of consciousness, fits, localized paralysis. This can also occur in toxaemia, cerebral malaria, electrolyte disturbances or vascular accidents.

In western Europe, herpes simplex or varicella–zoster viruses are the most common causes of encephalitis, but in many parts of the world arboviruses such as Japanese B encephalitis virus are important (see Ch. 51).

Abscesses in the brain or subdural space may arise from haematogenous spread during bacteraemia or by direct extension, either through the cribriform plate from the nasopharynx or from sinuses or the middle ear. They may be clinically silent or present as a space-occupying lesion accompanied by fever and systemic upset. Scanning by computerized axial tomography (CAT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and early neurosurgical intervention will reduce complications and with appropriate systemic antibiotics given for a prolonged period, the success rate is nowadays good.

Skin and soft tissue infections

Human skin acts as an excellent barrier to infection. Some parasites, such as hookworm larvae and schistosome cercariae, can penetrate skin to initiate infection. This may also be true of some bacteria, notably Treponema pallidum, although in primary syphilis the spirochaete probably enters through minute abrasions which are present even in healthy skin. Primary skin infection such as impetigo is due to Staph. aureus or Str. pyogenes, or both, gaining access to abrasions, usually in children. This may occur in association with ectoparasite infestation, in particular, scabies. Dermatophyte fungi are specialized to grow well in keratinized tissue.

Skin lesions are a feature of some virus infections, such as warts, herpes simplex and molluscum contagiosum. In other virus diseases, including rubella, measles, chickenpox (and, before its eradication, smallpox), a characteristic rash follows the viraemic phase of the illness. Wound infections may be accidental or postoperative and many organisms can cause sepsis. Even after surgery many wounds are infected with the endogenous flora of the patient. Swabs, or preferably pus, obtained directly from the wound or abscess, are adequate to find the causative organisms. Anaerobic sepsis most commonly occurs following amputations or in contaminated traumatic wounds, particularly if the blood supply has been compromised or the bowel perforated. In classic gas gangrene, bubbles of gas may be felt in the wound and surrounding tissues, and the muscle and fascia have a black necrotic appearance. Less florid examples of anaerobes causing extensive cellulitis are more commonly seen in situations where deep wounds are contaminated with endogenous flora.

Genital tract infections

In the male, acute urethritis is a common condition, usually due to a sexually transmitted microbe such as N. gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis or Ureaplasma urealyticum. If untreated these organisms can cause prostatitis or epididymitis, and gonorrhoea may produce unpleasant consequences such as urethral stricture or sterility. Genital ulcers in both sexes may be due to herpes simplex virus, syphilis or chancroid (H.ducreyi).

The more complicated female reproductive organs are subjected to many more infections with a greater scope for sequelae. Vaginitis may present as vaginal discharge or irritation and often these symptoms are due to infections that are not always exogenously acquired. Trichomonas vaginalis is the most common sexually acquired microbe, although both N. gonorrhoeae and chlamydia may also present as discharge. Thrush due to Candida species is especially common in pregnancy and in diabetics. It is usually an endogenous condition due to disturbances in the normal commensal flora. Another cause of vaginal discharge, but usually without inflammatory cells and irritation, is associated with an alteration of local pH with proliferation of Gardnerella vaginalis and anaerobic spiral bacteria, now termed Mobiluncus species. The alkaline conditions and characteristic amines found in bacterial vaginosis allow a diagnosis to be easily made on examination of the patient. This condition, which used to be called non-specific vaginitis, is a common condition in sexually active women, although probably not a venereal disease in the usual sense.

The endocervical canal is the site of infection with N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis in the sexually mature woman. During parturition both organisms may be passed to the baby’s eyes to give rise to ophthalmia neonatorum. The cervix may also be infected with human papillomavirus (HPV), the cause of genital warts. Some types are associated with a high risk of cervical cancer (see Ch. 45).

Ascending genital infection may present as acute salpingitis with fever and pelvic pain. On vaginal examination, there is referred lower abdominal pain on moving the cervix (cervical excitation) and tenderness in the iliac fossa on abdominal palpation. Signs and symptoms in cases due to C. trachomatis are much less pronounced than those due to gonococci. Some women may develop chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) without having suffered a recognizable acute episode. PID, although most often initiated by these two common sexually transmitted pathogens, is usually a polymicrobial infection, in which endogenous commensals, particularly anaerobes, play an important role.

Eye infections

Various microbes may cause acute conjunctivitis. During birth N.gonorrhoeae and C.trachomatis may be passed to the baby’s eyes from the maternal genital tract to give rise to ophthalmia neonatorum. In the newborn, Staph. aureus is commonly found in ‘sticky eyes’, either as a primary cause of conjunctivitis or after infection with another pathogen. In older infants and children, H. influenzae and Str. pneumoniae are common. Chlamydiae give rise to trachoma, the most common cause of blindness in the world, and to a milder form of inclusion blennorrhoea in sexually active individuals.

Primary viral conjunctivitis often occurs in epidemics when certain types of adenovirus are implicated. This is usually a mild condition with few sequelae compared with the keratitis due to herpes simplex virus or in shingles when the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve is infected with varicella–zoster virus.

Corneal damage due to fungi as well as herpesviruses is seen in immunosuppressed patients, and keratitis caused by free-living amoebae (Acanthamoeba species), though rare, is becoming more common, particularly in wearers of contact lenses.

Penetrating injuries of the eye and ophthalmic surgery may introduce a wide range of bacteria and fungi into the chambers of the eye, which may give rise to hypopyon (pus in the eye). This condition requires prompt surgical drainage and instillation of appropriate antibiotics such as gentamicin. Ps. aeruginosa and Proteus species are among the more common organisms isolated.

Infections of the back of the eye (choroidoretinitis) are seen in many diverse infectious diseases (Table 65.5).

Table 65.5 Causes of choroidoretinitis

| Viruses | Cytomegalovirus, rubella |

| Bacteria | Treponema pallidum |

| Protozoa | Toxoplasma gondii |

| Helminths | Toxocara canis, Onchocerca volvulus |

Systemic and general syndromes

Pyrexia of unknown origin

PUO may be defined as a significant fever (greater than 38°C) for a few days without an obvious cause, i.e. no apparent infection of an organ or system. In the classic studies of PUO only patients with persistent fever for at least 3 weeks were included. These chronic cases are often due to non-infective causes such as malignancy (especially lymphomata) or auto-immune and connective tissue diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematosus).

In determining an infective aetiology some of the most important questions to be asked of the patient are:

1. Have you been abroad recently?

2. What is your occupation (especially, is animal contact involved)?

3. What immunizations have you had – in particular, have you had BCG?

4. Have you or your family ever had tuberculosis?

5. Are you taking or have you recently had any drugs (especially antibiotics)?

Character of fever

The individual with suspected PUO should be admitted to hospital so that measurements can be regularly made by skilled staff. Rarely, malingerers may be found out and drug reactions discovered by controlling intake. Rhythmical fevers such as the quartan fever (every 72 h) of Plasmodium malariae or undulant fever of Brucella melitensis may be rarely found and point to the aetiology. More commonly, fevers are intermittent with rises at the end of the day and falls after rigors or extensive sweating.

The degree of temperature depends also on the host response as well as the pyrogens produced by microbes. Generally, the older the patient the less able they are to mount a pyrexia. Many elderly patients with septicaemia may have normal or subnormal temperatures whereas infants can have fevers of 40°C and febrile convulsions with otherwise mild respiratory viral infections.

Endocarditis

Infections of the tissue of the heart usually involve damaged valves, either after rheumatic fever or with atheroma. Another important group of patients are those who have had heart surgery, in particular prosthetic valve replacements. In addition, injecting drug users (IUDs) or patients who have had indwelling vascular devices are liable to bacteraemia and, occasionally, endocarditis may follow. The most common causative organisms are listed in Table 65.6.

Table 65.6 Some causes of infective endocarditis (approximate %)

| Organism | Non-operative (%) | IDU or surgery (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Viridans group of streptococci | 70 | 35 |

| Enterococci | 5 | 3 |

| Other streptococci (group G, F) | 10 | <1 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 10 | 25 |

| Staph. aureus | 5 | 25 |

| Gram-positive rods (diphtheroids) | <1 | 5 |

| Haemophilus spp. and other fastidious Gram-negative organismsa | <1b | <1 |

| Gram-negative bacilli (coliforms, Pseudomonas spp.) | 0 | 5 |

| Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) | <1b | 0 |

| Chlamydia psittaci | <1 | 0 |

| Fungi (Candida spp.) | <1 | 2 |

IDU, injecting drug user.

a Neisseria, Brucella, Cardiobacterium, Streptobacillus spp.

b These are rough UK figures; in some parts of the Middle East, brucellae and Q fever cause significant numbers of infective endocarditides.

Septicaemia

It is not clinically useful to distinguish between bacteraemia, organisms isolated from the bloodstream, septicaemia, which is a clinical syndrome, and endotoxaemia, which is circulating bacterial endotoxin. The spectrum of clinical disease ranges from hypotensive shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with a high mortality, to transient bacteraemia, which may occur in healthy individuals during dental manipulations.

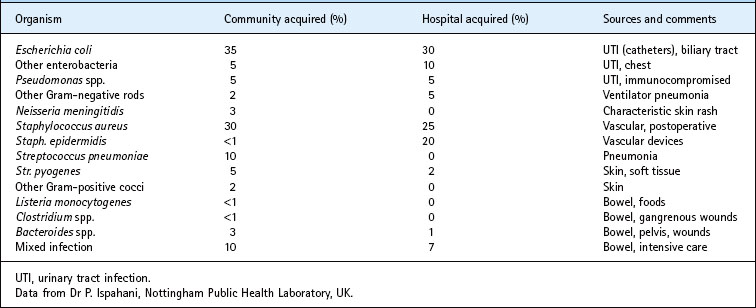

The vascular compartment is sterile and usually intact. Microbes gain entry from breakages of blood vessels adjacent to skin or mucosal surfaces or by phagocytic cells carrying organisms into capillaries or the lymphatic system. Active multiplication within the bloodstream probably only occurs terminally, but in many cases of septicaemia there are high numbers of bacteria recovered from blood cultures, which often only sample 10 mL at a time. This occurs from a heavily contaminated site such as an indwelling urinary catheter which releases bacteria into veins on movement. Septic shock may be due to Gram-negative lipids (endotoxins) or Gram-positive toxins (e.g. staphylococcal enterotoxin), which are usually proteins. The end result of both is to initiate a cascade of events involving cytokines, especially tumour necrosis factor and interleukin-2, vascular mediators and platelets, which combined lead to DIC and hypotension. This process becomes irreversible and produces failure of all major organs. Patients die from a variety of terminal events which make up the syndrome of septic shock. The main microbial causes are listed with approximate frequency in Table 65.7.

Clinical features may occasionally suggest the aetiological agent, e.g. the characteristic purpuric rash of meningococcal disease and the black lesions (ecthyma gangrenosum) seen on the skin of compromised patients with pseudomonas septicaemia, but in the majority of bacteraemias the agent can only be determined after blood culture. Sometimes, prior antibiotic therapy may render cultures negative and new methods of antigen detection or gene probes may be useful. Non-specific investigations, such as those shown in Figure 65.1, may offer some help that the cause of the illness is infective. C-reactive protein (CRP), an acute-phase protein which is often greatly elevated in the serum during bacterial infections, may be the most useful of these but, as with peripheral leucocyte counts, there are a significant number of errant results.

Imported infections

An important group of patients with fever are those who have recently returned from abroad. In whichever country a doctor may practice, travellers with unfamiliar disease will be encountered. Knowledge of medical geography is useful but conditions vary greatly within one country and with time. Up-to-date information is held, often on computer, by communicable disease centres and tropical disease hospitals and schools. The World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, USA, publish international notification data and maps (see Ch. 70 for websites). Undoubtedly the most important condition to diagnose is malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum, which may be rapidly fatal without appropriate treatment in the non-immune subject. The wide distribution of drug resistance in P. falciparum has led to difficulties in giving adequate prophylaxis and in treating an acute attack. Other common febrile illnesses which are imported into northern countries are typhoid and paratyphoid. These do not usually present with diarrhoea so the possibility of an enteric fever may not be considered. It is also obvious, but sometimes overlooked, that the fever may not be related to the travel history and that the cause is a microbe which could have been caught at home.

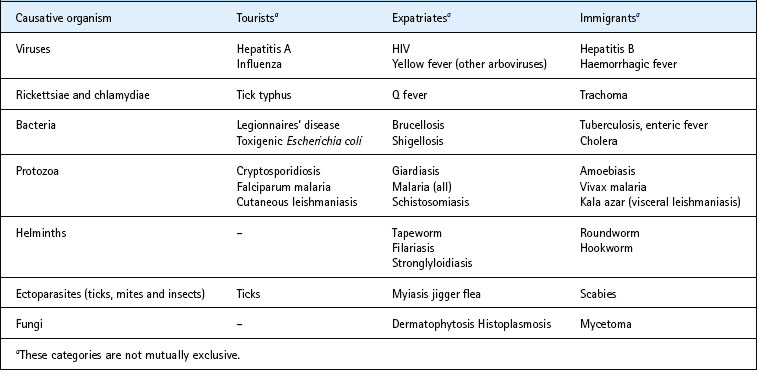

Table 65.8 lists some of the more common causes of infectious diseases imported from tropical countries into temperate regions where the diseases are not normally transmitted. There are three groups of patients which are considered separately, but the separation of diseases and microbes is not exclusive:

1. Short-term travellers or tourists who usually visit major cities or special holiday areas, stay in good accommodation and have minimal contact with the indigenous population.

2. Long-term visitors who may be engaged in lengthy overland trips or be working abroad as expatriates.

3. Immigrants who were brought up abroad and visit or have residence in the host country; also settled immigrants who pay short-term visits to their country of origin.

Individuals who travel abroad vary in their risk behaviour and their exposure to potential pathogens. Generally, advice given by travel operators, tourist offices, embassies and medical sources has greatly improved in the past few years. Companies sending out expatriate workers tend to look after their staff well. Nevertheless, many tourists (up to 50% in some studies) have episodes of travellers’ diarrhoea, which in some cases results in admission to hospital. The major groups who are missed in preventative programmes are overland travellers and immigrants returning to their homeland, often with young families who have never been exposed to the infectious risks of their parents’ home. Immigrants returning for visits to malarious areas seldom take prophylactic advice, believing themselves to be immune, but protective immunity wanes with prolonged absence.

Cryptogenic infections

Some of the commonly encountered sites of infection which may give rise to fever, and must be considered in the differential diagnosis of PUO, are listed in Table 65.9.

Table 65.9 Some common sites of infection in pyrexia of unknown origin

| Abdomen | Subphrenic abscess |

| Appendiceal abscess | |

| Ileal tuberculosis | |

| Pelvic abscess | |

| Liver and biliary tract | Intrahepatic abscess |

| Empyema of gallbladder | |

| Ascending cholangitis | |

| Cholecystitis | |

| Viral hepatitis | |

| Kidney and urinary tract | Perinephric abscess |

| Renal tuberculosis | |

| Pyelonephritis (especially children) | |

| Bones | Vertebral osteomyelitis |

| Tuberculosis | |

| Prosthetic infections | |

| Cardiovascular | Endocarditis |

| Graft infections | |

| Respiratory | Tuberculosis |

| Empyema and lung abscess | |

| Nervous system | Cryptococcal or tuberculous meningitis |

| Brain or spinal abscess |

Armstrong D, Cohen J. Infectious Diseases. Mosby, St Louis: Elsevier, 2011.

Conlon C, Snydman D. Color Atlas and Text of Infectious Diseases. Mosby, St Louis: Elsevier; 2000.

Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG. Principles and Practice of Paediatric Infectious Diseases. Saunders, Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2009.

Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, ed 6. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.

Warrell DA, Cox TM, Firth JD. Oxford Textbook of Medicine, ed 5. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.