Chapter 9 Law and the midwife

Learning Outcomes

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

This chapter includes an introduction to the Courts and how laws are made. It explores the key legislation that affects the practice of midwifery and provision of maternity care services.

Introduction to the law: the courts and how laws are made

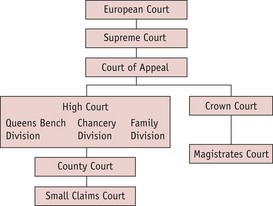

The courts (Fig. 9.1)

The main courts dealing with criminal proceedings are the Crown and Magistrates Courts. Those dealing with civil proceedings are the High Court, the County Courts and the Small Claims Courts. The Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court (which replaced the House of Lords from October 2009) will hear both criminal and civil cases. Where European laws are concerned, there can be an appeal to the European Court of Justice. In the case of issues relating to human rights (see below), appeal is to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

In addition to the court system outlined above, there are Coroners Courts and various administrative tribunals that also administer the law, for example, Employment Tribunals.

Since devolution, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales are able to enact their own statutes within specified areas.

Classification of the law

The most common distinction made is between criminal and civil law. A criminal offence is where the law (statute or common law – see below) forbids a particular activity which can then be followed by criminal proceedings against the accused. The prosecution must establish beyond reasonable doubt the guilt of the accused. In the Crown Courts, if the accused pleads not guilty, a jury will hear the case and determine guilt or innocence.

Civil proceedings take place between individuals and organizations in order that one party can obtain a remedy (for example, an injunction forbidding the other party to act in a particular way) or compensation. In civil courts, the standard of proof is ‘on the balance of probabilities’.

Some actions may give rise to both civil and criminal proceedings. Thus, touching a person without the person’s consent may be both a trespass to the person (which is a civil matter) and also constitute the criminal offence of assault or battery.

Another distinction in law is that between private and public law:

Some statutes may cover both areas: thus, the Children Act 1989 has some sections that deal with matters of a private nature; others deal with public issues, such as the role of local authorities in child protection.

Sources of the law

The law recognized in this country derives from two main sources:

Legislation

Britain is obliged as a member state of the the European Union (EU) to ensure that EU Directives and Regulations are enforced in this country, and appeals can be made to the European Court of Justice.

In the UK, when legislation is proposed, the usual practice is for a consultation paper to be issued (known as a Green Paper). Following consideration of the feedback, a White Paper is then issued setting out the Government’s intentions. The contents of this White Paper are incorporated into a Bill which is then passed through the various stages of Parliament and, when agreed by both House of Commons and House of Lords, is signed by the Queen. The Bill then becomes an Act and comes into force on a date set either in the Act itself or at a later date set out in a Statutory Instrument. The Act of Parliament may provide for the delegation to Ministers and others of powers enabling detailed rules to supplement the Statute to be enacted. These are known as Statutory Instruments or secondary legislation. They must be placed before Parliament before coming into effect.

Common law

Decisions by judges in courts create what is variously known as the common law, case law or judge-made law. The decisions of the courts create precedents which may be binding on courts below them in the court hierarchy. This is called the doctrine of precedent. Thus, decisions of the Supreme Court (replacing the House of Lords in its judicial format) are binding on those courts below it, but not itself; and decisions of the Court of Appeal are binding on itself and those courts below it.

The doctrine of precedent relies on a recognized system of reporting of judges’ decisions, which ensures certainty over what was stated and the facts of the cases. The decisions are recorded in law books such as the All England Law Reports or the Weekly Law Reports. Every case is identified by the year it was heard, the volume number and page number. For example, the case of Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee is cited as [1957] 1 WLR 582. This means that it was reported in 1957, in the first volume of the Weekly Law Reports at page 582. It is also reported in other series such as the All England Law Reports.

The main principles which are set out in a case are known as the ratio decidendi (reasons for the decision). Other parts of a judge’s speech which are not considered to be part of the ratio decidendi are known as obiter dicta (things said by the way). Only the ratio decidendi are directly binding on lower courts, but the obiter dicta are said to be ‘persuasive’ because they may influence the decision of judges in later court cases. It may be possible for judges to ‘distinguish’ the current case under consideration from previous cases and not follow them on the grounds that the facts are significantly different.

The Human Rights Act 1998

The European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (1951) provides protection for the fundamental rights and freedoms of all people. The UK is a signatory, as are many European countries which are not members of the European Union. Thus, Norway is a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights but not a member of the European Union. The Convention is enforced through the European Court of Human Rights, which meets in Strasbourg. However, following the passing of the Human Rights Act 1998, since 2 October 2000 most of the articles are directly enforceable in the UK courts in relation to public authorities or those exercising functions of a public nature. Of particular significance in healthcare are:

Other articles may also be relevant to the rights of patients and employees.

Under the Human Rights Act 1998, judges have a duty to refer back to Parliament for its consideration, legislation which they consider is incompatible with the rights set out in the European Convention. Parliament can then decide if that Act should be changed. The existence of a right to take a case for violation of rights to the courts of this country does not prevent a person taking a case to the European Court in Strasbourg. Further information including guidance and the latest cases can be obtained from the Ministry of Justice website (www.justice.gov.uk). Organizations exercising functions of a public nature are obliged to recognize and implement rights as set out in the Articles. Section 145 of the Health and Social Care Act 2008 provides for the provision of certain social care to be seen as a public function. Section 145 states that:

(1) A person (“P”) who provides accommodation, together with nursing or personal care, in a care home for an individual under arrangements made with P under the relevant statutory provisions is to be taken for the purposes of subsection (3)(b) of section 6 of the Human Rights Act 1998 (c. 42) (acts of public authorities) to be exercising a function of a public nature in so doing.

Midwives rules and the code of professional conduct

The statutory system of the regulation of nursing, midwifery and health visiting set out in the Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors Act 1979 (as amended by the 1992 Act) went through radical changes following a review of the statutory bodies (JM Consulting 1998) and the revised Health Act (1999) and Orders (2002). In April 2002, the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) was established and has revised much of the guidance originally provided by the UKCC. This includes the Midwives rules and code of practice. Codes of practice are complementary to the rules but, unlike the practice rules, do not have the force of law. Midwives are also expected to comply with the NMC Code of Professional Conduct: standards for performance, conduct and ethics (NMC 2008a) and other guidance from the NMC. Every midwife should ensure that they have copies of all the relevant NMC guidance which is available online from the Nursing and Midwifery Council (www.nmc-uk.org/). Box 9.1 indicates the purpose of the Midwives rules, which are set out under Statutory Instruments, and Box 9.2 sets out the midwife’s responsibility and sphere of practice.

Box 9.1

Aims of the Midwives Rules as set out in Article 42 of the NMC Order 2001

Box 9.2 Rule 6

Responsibility and sphere of practice

Supervision

Midwives are the only group of health professionals to have a statutory system of supervision. Appointed by the local supervising authority, the supervisor of midwives has clear statutory responsibilities in relation to the positive promotion of a high standard of midwifery practice, and the protection of the public. In 2006, the NMC published standards for the preparation and practice of supervisors of midwives and, in 2007, standards for supervised practice of midwives. In 2008, the NMC replaced the ENB publication on midwifery supervision with its own Modern supervision in action: a practical guide for midwives (NMC 2009).

Litigation

In 2007–08, 5470 claims of clinical negligence and 3380 claims of non-clinical negligence against NHS bodies were received by the NHS Litigation Authority (which is a Special Health Authority responsible for handling both clinical and non-clinical negligence cases on behalf of the NHS in England). There were 16,959 ‘live’ claims as at 31 March 2008 and it paid out £633,325 million in connection with clinical negligence claims. Of the 45,404 cases dealt with by the NHS Litigation Authority (NHSLA) since its creation in 1995, 9477 (21%) were for obstetrics and gynaecology, but looking at the total value of £6.5 billion, £3.3 billion was spent on obstetrics and gynaecology cases. So, 20% of the cases accounted for 50% of the expenditure, which is explained by the very high cost of obstetric claims (www.nhsla.com/home). The NHSLA estimates that its total liabilities (including claims not yet reported to it) are £21.06 billion. In an effort to reduce the costs of clinical negligence claims, the NHS Redress Act 2006 was passed to establish an alternative route for compensation to be paid without necessitating action in the civil courts. It remains to be seen whether it will become an effective alternative to legal action through the courts.

Negligence

What is negligence?

Negligence is the most common civil action, brought in situations when the claimant alleges that there has been personal injury, death, or damage or loss of property. Compensation is sought for the loss which has occurred. To succeed in the action, the claimant has to show the following elements:

Duty of care

The law recognizes that a duty of care will exist where one person can reasonably foresee that his or her actions and omissions could cause reasonably foreseeable harm to another person. A duty of care will always exist between the health professional and the patient, but it might not always be easy to identify what this includes. Where there is no pre-existing duty to a person (for example, an existing professional and patient relationship), the usual legal principle is that there is no duty to volunteer services (that is, perform a ‘good Samaritan’ act). The NMC recognized that there may be a professional duty to volunteer help in certain circumstances in the code published in 2002 (but not included in its revised code of 2008) (NMC 2008a).

In one case, the House of Lords defined the duty of care owed at common law (that is, judge-made law) as being:

You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who then in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.

Breach of duty

Determining the standard of care

In order to determine whether there has been a breach of the duty of care, it will first be necessary to establish the required standard of care. The courts have used what has become known as the ‘Bolam Test’ to determine the standard of care required by a professional. In the case from which the test took its name, the court laid down the following principle to determine the standard of care which should be followed:

The standard of care expected is ‘the standard of the ordinary skilled man exercising and professing to have that special skill’.

The Bolam Test was applied by the House of Lords in a case where negligence by an obstetrician in delivering a child by forceps was alleged:

When you get a situation which involves the use of some special skill or competence, then the test as to whether there has been negligence or not … is the standard of the ordinary skilled man exercising and professing to have that special skill. If a surgeon failed to measure up to that in any respect (clinical judgement or otherwise) he had been negligent and should be so adjudged.

In this particular case, the House of Lords found that the surgeon was not liable in negligence and held that an error of judgement may or may not be negligence. It depends upon the circumstances.

This standard of the reasonable professional man following the accepted approved standard of care can be used to apply to any professional person: architect, lawyer, accountant, as well as those working in health. The standard of care which a practitioner should have provided would be judged in this way. Expert witnesses give evidence to the court on the standard of care they would expect to have found in the circumstances before the court. These experts would be respected members of the profession of obstetrics and midwifery, possibly a head of a department or training college, and lawyers would look to the leading organizations of individual professional groups to obtain recommended names.

Reflective activity 9.2

Consider any incident of which you are aware, when harm (nearly) occurred to a woman or baby. What potential hearings could take place as a result of this harm and what would have to be shown to secure a conviction/guilt/liability?

In a civil action, the judge would decide in the light of the evidence that has been given to the court, what standard should have been followed.

The standards at the time of the alleged negligence apply; not the standards at the time of the court hearing. This is significant, since many cases take several years to come to court, in which time standards may have changed. Reference is made to literature and procedures which applied at the time of the alleged negligence to establish if a reasonable standard of care was followed.

Experts can of course differ. A case may arise where the expert giving evidence for the claimant states that the accepted approved standard of care was not followed by the defendant or its employees. In contrast, the expert evidence for the defendant might state that the defendant or its employees followed the reasonable standard of care. Where such a conflict arises, the House of Lords has laid down the following principle:

It was not sufficient to establish negligence for the plaintiff (that is, claimant) to show that there was a body of competent professional opinion that considered the decision was wrong, if there was also a body of equally competent professional opinion that supported the decision as having been reasonable in the circumstances.

The determination of the reasonable standard of care was considered by the House of Lords in the case of Bolitho v. City and Hackney Health Authority, when it was stated that:

The court had to be satisfied that the exponents of the body of opinion relied on can demonstrate that such opinion has a logical basis. In particular in cases involving, as they often do, the weighing of risks against benefits, the judge, before accepting a body of opinion as being responsible, reasonable or respectable, will need to be satisfied that, in forming their views, the experts had directed their minds to the question of comparative risks and benefits and had reached a defensible conclusion on the matter.

The use of the adjectives ‘responsible, reasonable and respectable’ (in the Bolam case) all showed that the court had to be satisfied that the exponents of the body of opinion relied upon could demonstrate that such opinion had a logical basis.

It would seldom be right for a judge to reach the conclusion that views held by a competent medical expert were unreasonable.

Rule 35 of the new civil court proceedings sets out the duties of experts and assessors. There is a duty to restrict expert evidence to that which is reasonably required to resolve the proceedings. The Rules can be accessed on the website for the Ministry of Justice (http://www.justice.gov.uk/civil/procrules_fin/index.htm).

Government documents (Department of Health 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000) have placed increasing emphasis on standard setting, clinical governance and effective risk management. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE – www.nice.org.uk), the Care Quality Commission (www.cqc.org.uk – which has replaced the Healthcare Commission) and National Service Frameworks (NSF) are leading to more guidance on standards to be achieved in all departments of a hospital and in community care. They are described in more detail later in this chapter and in Chapters 3 and 7. It is anticipated that these standards will be incorporated into the Bolam Test of reasonable professional practice. Practitioners are expected to follow the results of clinical effectiveness research in their treatment and care of patients. Patients are able to use these national guidelines to argue that inadequate care has been provided in their case, as a result of which they have suffered harm.

In 2008, the four Royal Colleges – Midwives, Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Anaesthetists, and Paediatrics and Child Health – co-operated in the preparation of a single, comprehensive document setting out 30 standards for maternity care. The document is available on the website of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (http://www.rcog.org.uk/womens-health/clinical-guidance/standards-maternity-care).

Midwives who decide that, in the light of the specific circumstances of a case, a procedure or protocol or guideline is not entirely appropriate, should ensure that clear documentation is completed including all the circumstances and reasons for the inappropriateness of the guideline, so that their practice can be seen to be justifiable against the standard of the reasonable practitioner.

Communication – between professionals, departments and with patients – is crucial to a reasonable standard of care. This is particularly important where one person is designated as the key worker on behalf of the multidisciplinary team. However, the Court of Appeal has stated that the courts do not recognize a concept of team liability and it is therefore for each individual professional to ensure that his or her practice is in accordance with the approved standard of care (Wilsher v. Essex Area Health Authority, 1986). Professionals should not take instructions from another professional which they know would be contrary to the standard of care that their profession would require. Failure to follow up a cytology report led to compensation being paid to the dead patient’s husband (Taylor v. West Kent Health Authority, 1997). This is supported by the NMC Code (2008a) which states that:

Has there been a breach of the duty of care?

Once it has been established in court what the reasonable standard of care should have been, the next stage is to decide whether or not what took place was in accordance with the reasonable standard – that is, whether there has been a breach of the duty of care or not. Evidence will be given by witnesses of fact as to what actually took place. Clear comprehensive documentation will be an important element in determining the facts of what took place. In a case where it was alleged that there had been negligence by a registrar following a forceps delivery, which led to damage to the anal sphincter, the court applied the test of the reasonable standard of care at the time of the birth and found the defendant not to be liable (Starkey v. Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust, 2007).

Causation

The claimant must show not only that there was a breach of the duty of care, but that this breach of duty caused actual and reasonably foreseeable harm to the claimant. This requires:

Factual causation

There may be a breach of the duty of care and harm but no link between them. In the case of Barnett v. Chelsea Hospital Management Committee (1968), a casualty officer failed to examine patients who came to the A&E department, when they were vomiting very badly. However, the widow of one was unable to obtain compensation, since it was established on the facts that because the man was suffering from arsenic poisoning, he would have died even if reasonable care had been provided. The breach of duty by the doctor therefore did not cause the man’s death.

The onus is on the claimant to establish that there is this causative link between the breach of the duty of care and the harm which occurred. In the case of Wilsher v. Essex Area Health Authority (1988), the claimants failed to establish that excess oxygen (resulting from the placing of a catheter to monitor oxygen in the vein, rather than in the artery) had caused the retrolental fibroplasia suffered by the baby. The House of Lords ordered a new hearing on the issue of causation, because excess oxygen was only one of five factors which might have caused the blindness. The parties then agreed to a settlement.

In a case where a baby suffered brain damage, an allegation that a midwife was negligent in failing to call a registrar an hour earlier to consider a caesarean section succeeded. The court held that this failure had led to the delay in deciding a caesarean delivery was appropriate. The court also held that the registrar was also negligent in failing to recognize the change in contraction patterns (Khalid v. Barnet and Chase Farm Hospitals NHS Trust, 2007).

Reasonably foreseeable harm

The harm which might arise may not be within the reasonable contemplation of the defendant, so that even though there is a breach of duty and there is harm, the defendant is not liable. This is because a negligent act may set off a ‘chain reaction’ of consequences and the courts have decided that there should be some limit on the liability of the defendant. For example, a midwife may have delayed in referring a woman for advice from an obstetrician and thus been in breach of her duty of care to the woman, but because of underlying medical problems suffered by the woman, the harm which arose was not reasonably foreseeable by the midwife.

No intervening cause which breaks the chain of causation

It may happen that any causal link between the claimant’s breach of duty and the harm suffered by the client is interrupted by an intervening event. For example, an independent midwife contrary to the reasonable accepted practice may have arranged to take a woman in labour in her car, but as a result of a road accident for which the midwife was not responsible, the woman suffered injuries and the baby was stillborn. The road accident would be seen as an intervening event which broke the chain of causation.

Harm

The final requirement to succeed in an action for negligence is that the claimant or their representatives must establish that the claimant has suffered harm which the court recognizes as being subject to compensation. Personal injury, death, and loss or damage to property are the main areas of recognizable harm. In addition, the courts have ruled that nervous shock where an identifiable medical condition exists (now known as post-traumatic stress syndrome) can be the subject of compensation within strict limits of liability. A test of proximity to the defendant’s negligent action or omission has been set by the House of Lords.

Vicarious and personal liability

It is unlikely that employees will be sued personally, since the employer will usually be vicariously liable for their actions.

To establish the vicarious liability of the employer, the claimant must show the employee was negligent or was guilty of another wrong whilst acting in the course of employment.

Independent practitioners have to accept personal and professional liability for their actions but they may also be vicariously liable for the harm, caused during the course of employment, by anyone they employ. Each of the elements shown above must be established so employers are not liable for the acts of their independent contractors (that is, self-employed persons who are working for them on a contract for services) unless they are at fault in selecting or instructing them.

The employer may challenge whether the actions were performed in the course of employment. For example, a midwife may have undertaken training in a complementary therapy, such as acupuncture. If she used these new skills whilst at work, without the express or implied agreement of the employer, and through use of this therapy caused harm to the client, the employer might refuse to accept vicarious liability on the grounds that the employee was not acting in the course of employment. However, the House of Lords held, in a case involving abuse of pupils at a school boarding house, that the Board of Governors was vicariously liable for the acts of the warden in abusing the claimants: the Home had undertaken the care of the children and entrusted the performance of that duty to the warden and there was therefore sufficiently close connection between his employment and the acts committed by him (Lister v. Helsey Hall, 2001).

Liability for student, unqualified assistants: supervision and delegation

Exactly the same principles apply to the delegation and supervision of tasks as to the carrying out of professional activities. Midwives delegating a task should only do so if they are reasonably sure that the person to whom the task is delegated is reasonably competent and experienced to undertake that activity safely. They must also ensure that the person undertaking that activity has a sufficient level of supervision to ensure that the delegated activity can be carried out reasonably safely. Should harm befall a client because an activity was carried out by a junior member of staff, student or assistant, it is no defence to the legal action to argue that the harm occurred because that person did not have the ability, competence or experience to carry out that task reasonably safely (Wilsher v. Essex Area Health Authority, 1986). There will be some midwifery tasks, such as attendance at a birth, which can never be delegated. Other activities may be delegated if the delegatee is assessed as competent and the requisite level of supervision is provided. The NMC has provided guidance on delegation within Midwifery (NMC 2004a) and the Code of Practice issued in 2008 states:

Defences to an action

The main defences to an action for negligence are listed below:

Dispute allegations

Many cases will be resolved entirely on what facts can be shown to exist. Thus, the effectiveness of the witnesses for both parties in establishing the facts of what did or did not occur will be the determining factor in who wins the case. Clearly, record-keeping and the witnesses in court will play a significant role in determining the facts of what took place. It might appear before the court hearing that one party has a particularly strong case but, unless the facts on which its case rests can be proved in court or are admitted by the other party, the actual outcome of the case might be that the opponent wins.

Deny that all the elements of negligence are established

The claimant must establish that all elements required to prove negligence are present, that is, duty, breach, causation and harm. If one or more of these cannot be established, then the defendant will win the case. In some situations, the claimant may be able to claim that ‘the thing speaks for itself’ (i.e. a res ipsa loquitur situation). This means that the claimant will say that there is no explanation for the damage other than a negligent act having taken place. If this claim is made, the defendant is then required to explain how what has happened could have occurred without negligence on his or her part.

Contributory negligence

If the claimant is partly to blame for the harm which has occurred, then there may still be liability on the part of the professional but the compensation payable might be reduced in proportion to the claimant’s fault. In extreme cases, if 100% contributory negligence is claimed, such a claim may be a complete defence. In determining the level of contributory negligence, the physical and mental health and the age of the claimant would be taken into account.

The Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945 enables an apportionment of responsibility for the harm that has been caused, which may result in a reduction of damages payable. The Court can reduce the damages ‘to such extent as it thinks just and equitable having regard to the claimant’s share in the responsibility for the damage’ (Section 1(1)).

One of the most frequent examples of contributory negligence being taken into account is in road traffic accidents where the injuries sustained by the claimant are greater because the claimant was not wearing a seat belt.

Exemption from liability

It is possible for people to exempt themselves from liability for harm arising from their negligence, but the effects of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 mean that this exemption only applies to loss or damage to property. A defendant cannot exclude liability from negligence which results in personal damage or death either by contract or by a notice. A midwife could not therefore agree with a woman that she would provide her with a waterbirth on the understanding that the mother would not hold the midwife (or the midwife’s employer) liable for any negligence.

Where exemption from liability for loss or damage to property is claimed by the defendant, it must be shown by the defendant that it is reasonable to rely upon the term or notice which purported to exclude liability.

Reasonableness in relation to a notice not having contractual effect means that: ‘it should be fair and reasonable to allow reliance on it, having regard to all the circumstances obtaining when the liability arose or (but for the notice) would have arisen’ (Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977: S.11 (3)).

Under Section 11(5), it is for those claiming that a contract term or notice satisfies the requirements of reasonableness, to show that it does.

The effect of this legislation is that notices which purport to exempt a department from liability for negligence are invalid if that negligence leads to personal injury or death. However, a notice which excludes liability for loss or damage to property may be valid if it is reasonable for the negligent person or organization to rely upon it.

Limitation of time

Actions for personal injury or death should normally be commenced within 3 years of the date of the event which gave rise to the harm, or 3 years from the date on which the person had the necessary knowledge of the harm and the fact that it arose from the defendant’s actions or omissions. There are, however, some major qualifications to this general principle and these are shown in Box 9.3. As can be seen, in maternity claims, as the action is brought by the baby/child, limitation is potentially 18 years or until death.

Box 9.3

Situations where the limitation of time can be extended

The limitation rules are linked to the periods for which records must be retained. The Department of Health has specified minimum retention periods – for maternity records, this is 25 years after last live birth; for other records, this is generally 8 years after treatment concluded or death. The importance of this can be demonstrated by the case of a woman who had suffered brain damage following heart surgery as a baby at the Bristol hospital, which led to the Kennedy Inquiry (Kennedy Report 2001). She was awarded a seven-figure sum in compensation more than 20 years after the surgery (Rose 2008). Seven further cases were said to be awaiting the outcome and are now likely to be pursued.

The definition of knowledge for the purposes of the limitation of time is that a person must have knowledge of the following facts:

Knowledge that any acts or omissions did or did not, as a matter of law, involve negligence, nuisance or breach of duty is irrelevant. A person is not fixed with knowledge of a fact ascertainable only with the help of expert advice so long as he has taken all reasonable steps to obtain and, where appropriate, to act on, that advice.

Voluntary assumption of risk

Volente non fit injuria is the Latin term for the defence that a person willingly undertook the risk of being harmed. It is unlikely to succeed as a defence in an action for professional negligence since professionals cannot contract out of liability where harm occurs as a result of their negligence. The defence of volenti non fit injuria would not be available to an employer as a defence against a midwife who argued that she had been exposed to HIV/AIDS as a result of negligence by her employer. The employers have a duty to take reasonable care of the health and safety of employees and it cannot be argued successfully that an employee accepts a risk of being harmed as an occupational hazard, where the employer has failed in its duty of care.

Compensation

The legal term for the amount of compensation to be paid is quantum (literally how much). The general rule governing the award of damages is that they should compensate the claimant for the loss s/he has suffered. This means that the claimant should be restored to the position s/he would have been in but for the negligent act.

There are two kinds of damages: general and special damages. Special damages refers to the actual financial losses between the negligent act and the trial (or settlement if there is no trial), for example loss of earnings, purchase of special equipment or adaptations to the home and the costs of medical and nursing care. General damages basically reflects compensation for pain and suffering from the injury and loss of amenity (reduced enjoyment of life) plus future financial losses, for example loss of earnings and future expenses.

In some cases of negligence, liability might be accepted by the defendant but there might be disagreement between the parties over the amount of compensation; or there may be agreement over the amount of compensation but liability may be disputed. In others, both liability and quantum might be in dispute.

Current developments in civil law

Significant changes were made to the civil procedures following the Final Report by Lord Woolf (Woolf 1996) which came into force in 1996. He recommended a new system in which the courts would have an active role in case management, including control over the use of expert evidence. He recommended a fast track for cases below a certain financial limit, where experts would normally be jointly appointed by the parties and would not be required to give oral evidence in court. Cases above this limit would be allocated to a multi-track, in which the court would have wide powers to define the scope of expert evidence and prescribe the way in which experts should be used in particular cases. The civil procedures can be accessed on the Ministry of Justice website (http://www.justice.gov.uk/civil/procrules_fin/index.htm).

In spite of these reforms, there are still worries about the delays and cost of litigation and in 2003 the Department of Health published a consultation document ‘Making Amends’ (Department of Health 2003) which provided a comprehensive account of the background to the current situation. It looked at the present system of medical negligence litigation and its costs and recommended the introduction of a new scheme for obtaining compensation in clinical negligence cases. The resulting legislation in the NHS Redress Act 2006 is not as radical as proposed in the consultation paper and is still to be implemented. The extent to which the new scheme to recover compensation replaces the use of civil court proceedings remains to be seen.

Conditional fees

Legal aid is being phased out from personal injury litigation. A system of conditional fees has been introduced whereby the claimant is able to negotiate, with a solicitor, payment on a ‘no win – no fees’ basis, that is, if the claimant loses, the solicitor does not charge any fees. However, a claimant who does not succeed will have to pay the costs of the successful defendant, and this possibility is covered by taking out insurance to meet these and other costs not covered by the agreement with the solicitor. Recent statutory changes enable a successful party to claim enhanced fees agreed with lawyers under the conditional fee agreement, from the unsuccessful party. In 2008, the NHS Litigation Authority (NHSLA) reported that the annual bill for solicitors representing patients was £90.7 million, double the amount 4 years previously, because of the increase in ‘no win – no fee’ claims. The bill for NHS lawyers was £43.3 million.

The NHS litigation authority (NHSLA) and the clinical negligence scheme for trusts (CNST)

In 1995, the NHS Litigation Authority (NHSLA) was established with responsibility for the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts (CNST). This scheme requires member trusts to pay an annual amount into a central pool, from which justified claims over an agreed amount will be paid. This means that NHS trusts do not have to set aside large amounts of money ‘just in case’ they have to pay out on a major negligence claim. Instead, the risk, and costs, are spread across the NHS and the maximum amount that an NHS trust will have to spend on a single claim is capped.

Great emphasis is placed on the importance of good clinical risk management, as this should reduce the number and cost of legal claims. A system of risk management standards for trusts participating in the scheme has been developed and payments into the pool are based upon assessments of the individual organizations carried out by the CNST. In 2008, the NHSLA piloted through the CNST new clinical risk management standards for maternity. They can be found on the NHSLA website (www.nhsla.com/home). There are three levels of attainment:

The identified risk areas are: risk management strategy, emergency caesarean section, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, clinical risk assessment and postnatal information.

There is a clear financial incentive for NHS trusts to attain the higher levels of participation (as this attracts a discount on their contributions to the central fund) but this also reflects more rigorous practices and thus better care for women and their babies.

The NHSLA oversees the CNST and also administers the scheme for meeting liabilities of health service bodies to third parties for loss, damage or injury arising out of the exercise of their functions. In practice this means claims by employees for accidents at work, or by visitors for accidents taking place in NHS premises.

Consent

It is a general legal and ethical principle that valid consent must be obtained before starting treatment or physical investigation, or providing personal care, to a patient. This principle reflects the right of patients to determine what happens to their own bodies, and is a fundamental tenet of good practice. Health professionals who do not respect this principle may be liable both to legal action by the patient and to action by their professional body or even to criminal prosecution.

There are two distinct aspects of the law relating to consent to treatment. One is the actual giving of consent by the patient, which acts as a defence to an action for trespass to the person. The other is the duty on the practitioner to give information to the patient prior to the giving of consent. The absence of consent could result in the patient suing for trespass to the person. The failure to provide sufficient relevant information could result in an action for negligence. These two different legal actions will be considered separately.

Trespass to the person

There are two types of trespass to the person. An assault is when an individual perceives a threat that she may be touched without her consent. If she is actually touched without her consent, then this is known as battery. Thus, threatening behaviour but without any physical contact would be assault, while a vaginal examination carried out without the woman’s consent could be battery.

The person who has suffered the trespass can sue for compensation in the civil courts (and in criminal cases a prosecution could also be brought). In the civil cases, the victim has to prove:

The victim does not have to show that harm has occurred. This is in contrast with an action for negligence, in which the victim must show that harm has resulted from the breach of duty of care.

Reflective activity 9.3

Analyse the activities which you undertake in relation to women in your care and note the extent to which you obtain consent by word of mouth, consent in writing or consent by non-verbal communication. What changes, if any, do you consider should be made to your practice?

Defences to an action for trespass to the person

The main defence to an action for trespass to the person is that consent was given by a mentally competent person. In addition, there are two other defences in law, which are:

Consent and negligence

As part of the duty of care owed in the law of negligence the professional has a duty to inform the patient about the significant risks of substantial harm which could occur if treatment were to proceed.

If the harm has not been explained to the patient, and the harm then occurs, the patient can claim that had she known of this possibility she would not have agreed to undergo the treatment. She could then bring an action in negligence. To succeed, the patient would have to show that:

Elements of consent

For consent to treatment to be valid, it must be given voluntarily, by an appropriately informed person (the patient or, where relevant, someone with parental responsibility for a patient under the age of 18) who has capacity to consent to the intervention in question.

Voluntarily

To be valid, consent must be given voluntarily and freely, without pressure or undue influence being exerted on the patient by partners, family members or health professionals.

Informed

To give valid consent, the patient needs to understand in broad terms the nature and purpose of the procedure, together with the risks of the procedure.

The leading case is that of Sidaway where the House of Lords stated that the professional was required in law to provide information to the patient according to the Bolam Test (Sidaway v. Bethlem Royal Hospital Governors, 1985). It is advisable to advise the patient of any material or significant risks in the proposed treatment and any alternatives to it, and the risks of doing nothing. A Court of Appeal judgement (Pearce v. United Bristol Healthcare NHS Trust, 1999) stated that it will normally be the responsibility of the doctor to inform a patient of ‘a significant risk which would affect the judgement of a reasonable patient’.

To ensure that the patient understands the information which is given, there are considerable advantages in a leaflet being provided (checking, of course, that the patient can understand it). This would also assist if there was any dispute over the information having been given.

Capacity

The person giving consent must be mentally competent. A child of 16 or 17 has a statutory right to give consent and a child below 16 may, if ‘Gillick competent’ (or competent according to Lord Fraser’s guidelines), also give consent. This means that the child, although below 16, has sufficient understanding and intelligence to enable him or her to understand fully what is involved in a proposed intervention.

The definition of mental capacity is now set out in the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005 and is established in two stages. First, it must be determined if a person has an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain. Secondly, if so, does this impairment or disturbance cause an inability to make a specific decision? A person is unable to make a decision for himself if he is unable to:

The existence of a mental illness will not automatically mean that a person is incapable of giving a valid refusal of treatment in her or his best interests, as in the case of Re C, where a Broadmoor patient was considered to have the capacity to refuse an amputation of the leg which doctors had advised him was indicated as a life-saving measure. An injunction was ordered against any doctors carrying out an amputation on him without his consent (Re C, 1994).

Refusal to consent

The principle of the right of self-determination if the adult is mentally competent has been applied and extended by the Court of Appeal in two cases where a compulsory caesarean section had been carried out. In the first case (Re MB, 1997), the pregnant woman suffered from needle phobia and would not agree to an injection preceding the caesarean. The court held that the needle phobia rendered her mentally incapable and therefore it declared that doctors performing a caesarean, acting in her best interests, would not be acting illegally. Under the MCA there is a presumption (which can be rebutted if the evidence exists) that a person over 16 years has the requisite mental capacity to give consent.

The facts of the second case (St George’s Healthcare National Health Service Trust v. S, 1998) are as follows. S was diagnosed with pre-eclampsia and advised that she needed urgent attention, bed rest and admission to hospital for an induced delivery. Without that treatment, the health and life of both herself and the unborn child were in real danger. She fully understood the potential risks but rejected the advice. She wanted her baby to be born naturally.

She was then seen by an approved social worker and two doctors in relation to compulsory admission to hospital under the Mental Health Act 1983 Section 2 for assessment. They repeated the advice which she had been given and she refused to accept it. On the basis of the written medical recommendations of the two doctors, the approved social worker applied for her admission to hospital for assessment under Section 2 of the Mental Health Act 1983. Later that day, again against her will, she was transferred to St George’s Hospital. In view of her continuing adamant refusal to consent to treatment, an application was made ex parte on behalf of the hospital authority to Mrs Justice Hogg, who made a declaration that the caesarean section could proceed, dispensing with S’s consent to treatment. The operation was carried out and a baby girl delivered. The woman was then returned to Springfield Hospital and 2 days later her detention under Section 2 of the Mental Health Act was ended.

The woman then sought judicial review of her detention, the High Court judgement and the caesarean operation. The Court of Appeal held that the Mental Health Act 1983 could not be deployed to achieve the detention of an individual against her will merely because her thinking process was unusual, even apparently bizarre and irrational, and contrary to the view of the overwhelming majority of the community at large. A woman detained under the Act for mental disorder could not be forced into medical procedures unconnected with her mental condition unless her capacity to consent to such treatment was diminished. The Court of Appeal was not satisfied that she was lawfully detained under Section 2 of the Mental Health Act 1983 because she was not suffering from mental disorder of a nature or degree which warranted her detention in hospital for assessment. Although on the face of the documents her admission would appear to have been legal, her transfer to St George’s Hospital was unlawful and at any time she would have been justified in applying for a habeas corpus which would have led to her immediate release. The declaration made by the High Court Judge should not have been made on an ex parte basis (that is, without representation of the woman) and was unlawful.

The difference between the two cases is that in the first case the woman was held, as a result of the needle phobia, to be mentally incompetent, and therefore the caesarean section could be carried out in her best interests without her consent. However, in the second case, S was not held to be mentally incompetent and therefore the compulsory caesarean was a trespass to her person. In neither case did the court consider the rights of the fetus to influence the decision-making.

The fetus is not regarded in law as a legal personality until birth. Until then, the wishes of a mentally competent pregnant woman will prevail whatever the effect on the fetus. Since October 2007, the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 would apply where the woman was assessed as lacking the requisite mental capacity.

Mental Capacity Act 2005

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 has replaced the common law power to act out of necessity in the best interests of the patient. Where it is established that the patient lacks the capacity to give consent to treatment, treatment can proceed under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 on the basis that it is in the best interests of that individual and is given according to the reasonable standard of the profession. For example, if a woman who had delivered at home, unattended, had a postpartum haemorrhage and was admitted to hospital in a state of collapse, lacking the mental capacity to give consent, with no information available as to her preferences, it would be lawful to examine her and undertake any necessary procedures to preserve her life, including surgery and the administration of blood products, without obtaining prior consent. If time permits, the Act requires steps to be taken to determine what is in the best interests of that person and, in the absence of carers who could be consulted over what was in her best interests, the appointment of an independent mental capacity advocate where serious treatment is being considered.

Action cannot be taken in a person’s best interests, unless they lack the mental capacity to give consent. For example, if a mentally competent woman refuses blood or blood products, these cannot be given to save her life should her condition become critical. The Mental Capacity Act enables a mentally capacitated person to draw up an advance decision, under which they can refuse treatment at a future time, when they lack capacity. Where life-saving treatment is refused in advance, specific statutory provisions must be satisfied, including a written statement signed by the maker and signed by a witness, making it clear that a life-saving measure is being refused.

Forms of consent and consent forms

Consent can be given by word of mouth, in writing or can be implied, that is, the non-verbal conduct of the person may indicate that consent is being given, such as offering an arm for an injection. All these ways of giving consent are valid, but where procedures entail risk and/or where there are likely to be disputes over whether consent was given, it is advisable to obtain consent in writing, since it is then easier to establish in a court of law that consent was given.

What if someone wishes to leave hospital?

It is a principle of consent that a person who has given consent can withdraw it at any time. This means that if people wish to leave hospital contrary to their best interests, unless they lack the capacity to make a valid decision, they are free to go. Clearly, there are advantages in obtaining the patient’s signature that the self-discharge or refusal to accept treatment was contrary to clinical advice. If patients refuse to sign a form that they are taking discharge contrary to clinical advice, that refusal must be accepted. It would in such a case be advisable to ensure that there is another professional who is a witness to this and that a careful record is made by both professionals.

Laws regulating pregnancy, birth and children

Abortion Act 1967 as amended (Box 9.4)

The provisions set out in Box 9.4, including the requirement to have two registered medical practitioners, do not apply in an emergency when a registered medical practitioner is of the opinion, formed in good faith, that the termination is immediately necessary to save the life, or to prevent grave permanent injury to the physical or mental health, of the pregnant woman.

Box 9.4

Abortion Act 1967 Section 1(1) as amended by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990

A person shall not be guilty of an offence under the law relating to abortion when a pregnancy is terminated by a registered medical practitioner if two registered medical practitioners are of the opinion, formed in good faith:

Registration of births and stillbirths; births under 24 weeks

The law requires that every birth is registered. When there is a stillbirth, this is registerable if it occurred after 24 weeks or more of gestation. Miscarriages of less than 24 weeks do not have to be registered, but the body must be disposed of with public decency and the wishes and feelings of the parents taken into consideration. Where a live birth is followed by a death (whatever the length of gestation), there must be a registration of both the birth and the death. In other words, if the baby is born alive, even if only for a brief time, and even where the gestation is less than 24 weeks, a birth must be registered, and if the baby subsequently dies, then a death must be registered.

Human Fertilisation and Embryology Acts 1990, 1992 and 2008

These Acts provide a legal framework within which infertility treatment and embryo growth and implanting can take place. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority is responsible for licensing centres and issuing a code of practice, and has general responsibility for ensuring that the law is followed.

Criminal law and attendance at birth

A midwife could face criminal proceedings in respect of her work if she offends against the criminal laws, such as health and safety laws or road traffic Acts. If she acts with gross recklessness or negligence in her professional practice, then she could face criminal proceedings. For example, an anaesthetist was held guilty for the death of a patient in theatre where he acted with such gross recklessness as to amount to a criminal offence of manslaughter (R v. Adomako, 1995).

Section 16 of the 1997 Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors Act made it a criminal offence for a person other than a registered midwife or a registered medical practitioner (or student of either) to attend a woman in childbirth except in an emergency or undergoing professional training as doctor or midwife. This is re-enacted in Article 45 of the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001. If the midwife is obstructed by an aggressive partner during a home confinement, she would be able to call upon police powers to assist her.

Children Acts 1989 and 2004

The Children Act 1989 set up a framework for the protection and care of children and established clear principles to guide decision-making in relation to their care. This is considered in Chapter 15.

Health and safety laws

The basic health and safety duties are placed upon employers by the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. This Act has been supplemented by many statutory instruments defining more specific duties in relation to manual handling, protective clothing, and the management of health and safety in the workplace. These statutory duties are enforceable by the Health and Safety Executive in the criminal courts. In addition, they are paralleled by duties placed on the employer under the common law. As a result of an implied term in the employment contract recognized by the courts, every employer must take reasonable care of the physical and mental health and safety of the employee. Therefore, employers may be liable to pay compensation to an employee where:

Duties laid down under the manual handling regulations are also paralleled by the employer’s responsibility for ensuring that reasonable action (including that of implementing the regulations) is taken to prevent the employee being harmed through manual handling. Every employer has a responsibility to carry out a risk assessment of dangers and hazards in the workplace, including an assessment for substances hazardous to health under the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations (2002). Regulations also require any incident involving injuries to be reported (RIDDOR; HSE 1995) and further information is available from the HSE website (www.hse.org.uk/riddor). The Medical Devices Regulations (1995) require adverse incidents involving medical devices to be reported to the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (replacing the Medical Devices Agency [MDA]) in accordance with the notice revised by the MHRA in 2007 and accessible on the MHRA website (www.mhra.gov.uk). Any warnings issued by the Agency must be acted upon. Employees also have a duty to take reasonable care of their own health and safety and those around them.

Legal aspects of record-keeping

Midwives have clear responsibilities under the Midwives’ Rules to ensure that their documentation of their midwifery care is kept properly (NMC 2004b, 2008). In addition, if they leave their post, there are specified duties for the transfer of their records. Their supervisor of midwives is also entitled to inspect their records and record-keeping standards. The NMC has updated the guidance on standards in record-keeping (NMC 2009b). It is recommended that records should be kept for at least 25 years. However, where the midwife is aware that a child has been born with serious mental disabilities, it would be wise for those records to be retained until at least 3 years after that person’s death, since in the case of those under a mental disability, there is no time limit for bringing a legal action for compensation as long as they are alive.

The Data Protection Act 1998 covers both computerized and manually held records and requires those who deal with personal records to register their storage and use of those records. The duties laid down in the Act are enforced by criminal proceedings. Rights of subject access to personal health records are given by the Act subject to specified exceptions where serious harm would be caused to the physical or mental health of the applicant or another, or where a third party (not being a health professional caring for the patient) who would be identified by the disclosure has requested not to be identified.

Medicines

Midwives have statutory powers in relation to the prescribing of medication. These are set out in the Rules, and guidance is provided in the code of practice (NMC 2008a) and in the standards for medicine management first published by the NMC in 2007. The NMC has also published Guidance for continuing professional development for nurse and midwife prescribers (NMC 2009c).

Refer to Chapter 10 for specific laws and rules governing drugs and medicines.

Complaints

A new complaints system covering both health and social care was introduced in April 2009. There are two stages within the complaints procedure: local handling and independent review by the Health Service Ombudsman. However, the procedure emphasizes the importance of resolving complaints at local level if at all possible. Further details of the procedure can be obtained from the Department of Health (DH) website (www.dh.gov.uk).

Miscellaneous legal issues of relevance to the midwife

Care of property

Failure to look after another person’s property could lead to criminal prosecution, for example, theft, civil action for trespass to property, or negligence in causing harm to property. In an action for negligence, the person who has suffered the loss or damage of property must establish the same four elements that must be shown in a claim for compensation for personal injury, that is, duty, breach, causation and harm.

Where, however, property is left by a person (known as the bailor) in the care of another person (the bailee), then, should the property be lost or damaged, the burden would be on the bailee to establish how that occurred without fault on his or her part. This is the situation when a client hands over money or valuables for safekeeping in the ward safe. It should be noted that liability for loss or damage to property can be excluded if such an exclusion is reasonable (see the Unfair Contract Terms Act above).

Vaccine damage

A statutory scheme for compensation was introduced under the Vaccine Damage Payments Act 1979 to compensate those who have suffered harm as a consequence of receiving vaccines. Public health requires a high level of herd immunity to ensure that major infectious diseases are eradicated, and, therefore, a high level of vaccination in the community is required. Since it is recognized that there is a tiny risk of harm from these vaccinations, it was accepted that, as a consequence, there should be compensation for those few who suffered such harm as a result of being vaccinated. The amount available has recently been increased from £100,000 to £120,000. Any applicant must establish that he or she has been severely disabled as a result of a vaccination against the specified diseases of diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, poliomyelitis, measles, rubella, tuberculosis, smallpox, and any other disease specified by the Secretary of State for Health. The severe disability must be at least 60% (this was formerly 80%). Whether the disability has been caused by the vaccination shall be established on a balance of probabilities. There was a 6-year time limit on making claims but this is being raised to any time up to the age of 18 years. This will enable more persons disabled by vaccines to claim the payment, including those who have already been rejected, who can reapply under the new rules. An applicant under the statutory scheme is not barred from pursuing a claim in negligence, where, if successful, the level of compensation may be far higher. However, an award under the statutory scheme would be taken into account in a negligence payment and vice versa.

Congenital Disabilities (Civil Liability) Act 1976

This Act enables a child who is born disabled as a result of pre-birth negligence to obtain compensation from the person responsible for the negligent act. The mother can only be sued if she was negligent when driving a motor car (in this case the child would be suing the mother’s insurance company). A recent amendment enables those whose children have been disabled during IVF treatment to obtain compensation.

Negligent advice

There can be liability for negligence in giving advice, but the claimant would have to show that it was clear to the defendant that he or she would rely upon the advice and in so doing had suffered reasonably foreseeable loss or harm. For example, providing a reference for a student or colleague can lead to liability both to the recipient of the reference, if in reliance upon that reference the recipient has suffered harm, and also to the person who is the subject of the reference (Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v. Heller & Partners Ltd, 1963). The latter would have to show that the reference was written without reasonable care, and harm occurred to the subject of the reference as a result of potential employers relying upon the reference (Spring v. Guardian Assurance, 1994). Every care should therefore be taken to ensure that a reference is written accurately in the light of the facts available.

Statutory duties and the duty of quality

Statutory duties are placed upon the Secretary of State for Health to provide a comprehensive service to meet all reasonable needs, and these duties are in turn delegated to the NHS organizations. At regional level, there are strategic health authorities (SHAs) which set the overall strategy and monitor the performance of the NHS organizations for which they are responsible. At local level, primary care trusts (PCTs) arrange for the commissioning of health services from NHS trusts and others and provide primary care services through independent contractors such as family practitioners, pharmacists and dentists (in Wales, this is undertaken by local health boards).

Clinical governance and the duty of quality

Under Section 45 of the Health and Social Care Act 2008, the Secretary of State has the power to prepare and publish statements of standards in relation to the provision of NHS care, which must be implemented by NHS organizations and are monitored by the Care Quality Commission. Failures in fulfilling this statutory duty could result in the removal of a board or the dismissal of its chief executive and chairman.

The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) was established in April 1999 to promote clinical and cost effectiveness across the country. It investigates medicines, and other treatments, and in the light of its research makes recommendations to the Department of Health on the clinical and cost effectiveness of such treatments. In 2008 it issued guidance on induction of labour. This and other guidelines relating to midwifery services are available on the NICE website (www.nice.org.uk). Guidelines and recommendations made by NICE can be used by midwives to press for additional resources if they are aware that the standards of care and services provided in their units are lower than those nationally recommended.

The Commission for Health Improvement (CHI) was established under Sections 19 to 24 of the Health Act 1999 as a body corporate (that is, it can sue and be sued on its own account), with significant powers. It was subsequently replaced by the Commission for Health Audit and Inspection (known as the Healthcare Commission) and has since April 2009 been amalgamated with other inspection bodies, including the Commission for Social Care Inspection and the Mental Health Act Commission, into the Care Quality Commission. In 2006 the Healthcare Commission published a report on Northwick Park Hospital following the deaths of ten women in childbirth between 2002 and 2005, which is available on its website (www.cqc.org.uk). In January 2008 the Healthcare Commission reported that more than four in ten maternity units offer below average care. Only 64% of hospitals were carrying out the 11 checks on fetal growth as recommended by NICE. In July 2008, in a review on maternity services, the Healthcare Commission concluded that there were significant weaknesses in maternity and neonatal services across England with a shortage of doctors, midwives and basic medical facilities.

National Service Frameworks (NSFs)

National Service Frameworks are gradually being published in most clinical areas so that there are identifiable quality standards provided across the country. The NSFs are accessible on the DH’s specific website (http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/index.htm). The NSF for Children, Young Persons and Maternity was published in 2004. Standard 11 for maternity services sets the following:

Future changes

Since the Cumberlege Report was published in 1993 (Department of Health 1993), there have been many reports recommending the implementation of changes to secure reasonable standards within maternity services in the NHS. The Audit Commission made recommendations in 1997 (Audit Commission 1997) and Reform published a review in 2005 (Bosanquet et al 2005) showing that progress since Cumberlege had been modest. The King’s Fund published an independent inquiry into the safety of maternity services in 2008 (King’s Fund 2008), making significant recommendations for reform, which is available on its website (www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications). The Healthcare Commission published a major review in 2008 (Healthcare Commission 2008) which raised serious concerns about the standards in maternity services in England, in spite of the nine reports which the Commission had published on maternity services between 2002 and 2008. In 2007 the Department of Health published Maternity matters (Department of Health 2007) setting targets to be achieved by 2009 where all women will have choice over the type of care that they receive, together with improved access to services and continuity of care. Raising the standards of maternity services will clearly be a priority of the Care Quality Commission.

Conclusion

This chapter covers a large area of law of considerable importance to midwifery practice. It is suggested that the reader should follow up this chapter by referring to some of the recommended texts to obtain a more detailed knowledge of the law. The current emphasis on human rights, the growth of litigation, the requirement that there must be sound professional practice, all show the importance of midwives having an understanding of the laws which apply to their practice and how essential it is, as in all other areas of their competence, that they keep up to date. In addition, it is clear from the many reports of the Healthcare Commission and other organizations that maternity services are in general failing to comply with the standards set by the CNST, with the guidance published by NICE and with the recommendations of the Healthcare Commission itself. The Care Quality Commission faces a major challenge in ensuring that necessary improvements take place. Midwives are, as a consequence, likely to experience significant changes in future years.