Chapter 38 Pain, labour and women’s choice of pain relief

Introduction

The 9 months of pregnancy culminates in birth, an event that many women fear because the process can be painful. Some women become anxious about their ability to cope with pain and this may impact on their perceptions of control during labour and their overall satisfaction of childbirth. The challenge for midwives is in enabling women to understand the various influences upon women’s interpretations and experiences of the discomforts that accompany birth. Midwives may assist women to be prepared and facilitate the optimum choices for pain relief to match women’s individual needs and ensure the best outcome for both mother and fetus.

An exploration of pain in labour

Pain is complex, personal, subjective, and a multifactorial phenomenon influenced by psychological, physiological and sociocultural factors. Though pain is universally experienced and acknowledged, it is not completely understood (Lowe 2002). Pain is usually associated with injury and tissue damage, thus a warning to rest and protect the area. However, in childbirth, pain is considered to be a side-effect of the process of a normal event (Simkin & Bolding 2004). Increasing pain at the end of pregnancy is often the first sign that labour has commenced (McDonald 2006).

The origins of labour pain are centred on the physiological changes which take place during labour. Pain predominates from the cervix and lower uterine segment, particularly in the first stage of labour (McDonald 2001). Effacement and dilatation of the cervix causes the stripping of membranes away from the uterine lining, hence the ‘show’ of early labour (McDonald 2006). This causes prostaglandin release. (See Chs 35 and 36.)

Prostaglandin aids the contractility of the myometrium, playing an important role in the initiation of labour (RPSGB & BMA 2008). Manipulation of the cervix during a vaginal examination directly stimulates the production of prostaglandins and increases pain. Nerve endings are stimulated, resulting in a form of inflammatory response in the tissues, which creates pain signals. This response produces histamine, serotonin and bradykinins, which stimulate the nociceptors in the cervix, setting up pain sequences. This stimulates an action potential in the nerve, setting up a chain reaction to the spinal cord and the higher centres in the brain (Tortora & Grabowski 2000, Yerby 2000).

Uterine nerve supply and nerve transmission

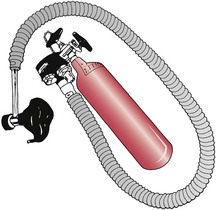

The autonomic nervous system serves the uterus with sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibres (see Ch. 35). Nerve pathways supplying the uterus and cervix arise from afferent fibres of the sympathetic ganglia. Nerve endings in the uterus and cervix pass through the cervical and uterine plexuses to the pelvic plexus, the middle hypogastric plexus, the superior hypogastric plexus and then to the lumbar sympathetic nerves to eventually join the thoracic 10, 11, 12 and lumbar 1 spinal nerves (Fig. 38.1).

(Reprinted from Pain in childbearing, Yerby M (ed), 2000, by permission of the publisher Baillière Tindall.)

The nerve supply to the perineum and lower pelvis from the second and third sacral nerve roots meets the plexuses from the uterus at the Lee–Frankenhäuser plexus at the uterovaginal junction (Stjernquist & Sjöberg 1994) (see Ch. 25). These nerves transmit pain in the second stage of labour.

Nerve transmission is along fibres that conduct sensations in different strengths and at different speeds. These fibres are either A delta, thinly myelinated fibres, or C fibres, which are unmyelinated. It is the smaller C fibres which are found in the deep viscera, such as the uterus, that give rise to the deep prolonged pain of labour when stimulated by muscular contraction and chemical substances (McDonald 2006, McGann 2007).

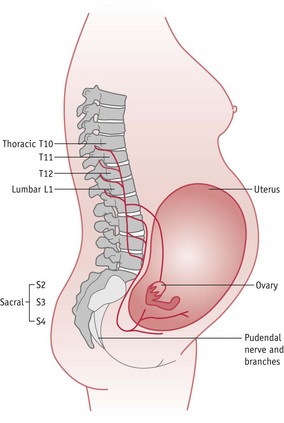

Pain sensation is transferred by action potentials (see website) along the nerve fibres to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, thence via upward tracts to the central nervous system (McCool et al 2004) (Fig. 38.2). Because of the release of bradykinins and histamines and other pain-inducing substances at tissue level, ‘substance P’ is also released. This is a neuropeptide and is released from the afferent nerves (McGann 2007) as part of the ‘signalling process’ of pain on its way to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord; it could be termed a potentiator of pain sensation.

Figure 38.2 Brain and spinal cord connections.

(Reprinted from Pain in childbearing, Yerby M (ed), 2000, by permission of the publisher Baillière Tindall.)

As the action potentials from the afferent neurons meet the spinal cord they enter by the posterior (dorsal) root and are transferred to the substantia gelatinosa at laminae (or layers) II and III of the grey matter of the spinal cord. These laminae decode various types of stimulus and transfer sensations to the higher centres of the brain via the anterior and lateral spinothalamic tracts, which cross to the opposite side of the cord before ascending, and are perceived as pain by the cerebral cortex (McCool et al 2004).

Descending tracts from the brain, returning to the spinal cord, may have a modulating effect on the nerve transmission of pain (Fig. 38.2). Naturally occurring endorphins at the spinal level act like exogenous opioids by modulating pain response (McGann 2007, Millan 2002).

As labour progresses, signs of the effect of pain on the woman become evident. Pain causes a boost in catecholamine secretion, thus increasing levels of adrenaline. The result is a rise in cardiac output, heart rate, and blood pressure, possibly causing hyperventilation that decreases cerebral and uterine blood flow by vasoconstriction, which may affect contractility of the uterus (McDonald 2006). Uterine contractions may be lessened by increased levels of adrenaline and cortisol and can cause uncoordinated uterine activity (McDonald & Noback 2003). Hyperventilation tends to alter oxygen balance, which may modify the acid–base status of the blood, causing maternal alkalosis, which may in turn cause fetal hypoxia (Lowe 2002).

Pain gate theory

Melzack & Wall (1965) described a mechanism for modulating pain at spinal cord level. Opioid-like substances, namely endorphins and enkephalins, are neurotransmitters and neuromodulators. These are found principally in the sensory pathways where pain is relayed (Melzack & Wall 1965). With greater understanding of endorphins and their opiate-type properties, it was noted that they dampened the effect of substance P. They are highly effective pain-modulating substances that play a role in pleasure, learning and memory (McGann 2007).

The ‘gate theory’ suggests a mechanism that prevents the transfer of nerve stimuli to the higher centres of the brain where they are perceived to become conscious as a feeling of pain. At the dorsal horn root in the substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord, substances may be blocked by a ‘gating’ mechanism. When the ‘gate’ is open, pain sensations reach the higher centres. When the ‘gate’ is closed, pain is blocked and does not become part of the conscious thought, and therefore pain is reduced.

Psychological aspect of pain

Whilst it may be easy to acknowledge physical pain, the pain in labour has a psychological component. This is a point to be appreciated by midwives and other health professionals. The psychological influences were recognized in the early theories of nociception (Eccleston 2001), which claimed that the manner in which individuals perceive and respond to pain involves more than peripheral input (Adams & Field 2001).

There exists an affective dimension of pain, which relates not only to the unpleasant feelings of discomfort but also to emotions that may be connected to memories or imagination (Price 2000a). Anxiety related to pain has a protective role that facilitates appropriate behaviours (Carleton & Asmundson 2009) which may be necessary to prepare for the impending birth. However, individuals with high levels of anxiety sensitivity tend to become fearful of the symptoms of pain, demonstrating states of hypervigilance (Thompson et al 2008). This fear may relate to the pain that is currently present but also to perceptions and concerns of what could occur (Carleton & Asmundson 2009). Individuals choose to avoid what they consider to be potentially pain-inducing situations as a result of this fear (Hirsh et al 2008). As such, this may result in what Hirsh et al (2008) describe as pain catastrophizing in reaction to childbirth – a predisposition to underestimate a personal ability to deal with pain, while exaggerating the threat of the pain anticipated. Catastrophizing has been shown to be positively associated with avoidance behaviour in labour (Flink et al 2009).

It should be noted that perceptions of pain will vary among women even when the stimuli are similar. Women react to their labour pains in different ways. This may result in a range of behaviour, such as distraction (Eccleston 2001) or feelings of anger and entrapment (Morley 2008). Maternity caregivers will need to be alert to women’s expectations when dealing with their individual pain. It is important to provide clear and brief communication, repeat and explain points where necessary, and make an effort to provide consistent information and guidance (Eccleston 2001).

Cultural aspect of pain

Midwives should acknowledge that the definition, understanding and manifestation of pain will be influenced by cultural experiences of both the woman and her caregivers. Culture affects attitudes toward pain in childbirth, how women cope with this and how they manage it (Callister et al 2003). While some individuals may accept intervention when in pain, others may demonstrate a more stoic approach and avoid help because of their socialization towards behaviour in such circumstances (Davidhizar & Giger 2004).

Various qualitative studies have shown how women from different backgrounds perceive and deal with the pain associated with childbirth. In their research, Johnson et al (2004) found that Dutch women felt that birth was a normal phenomenon that is accompanied by pain, which, though difficult, should not be feared, but used effectively. Somalian women in the study by Finnström & Söderhamn (2006) had been told that it was not acceptable to cry and wail when in pain. As an alternative, they felt that it was necessary to stay in control, tolerate the pain and involve a friend or a family member to help them cope with the event. In Jordan, Abushaikha (2007) found that women utilized spiritual methods to cope and were required to demonstrate patience and endurance towards the pain as a show of strong faith. The women in this study had to ensure that they were not overheard and were expected to labour silently.

Midwives’ own cultural experiences of pain will affect their interpretation and attention to women in labour. A study in Scotland comparing Chinese with Scottish women, indicated through one midwifery manager’s comment, that a loud coping strategy was occasionally misconstrued by health workers. They were more likely to interpret this as a sign of inability to cope and offer the women analgesia or anaesthetics. Those who remained quiet were often unnoticed (Cheung 2002).

There is a need for cultural competence when caring for women in childbirth (Brathwaite & Williams 2004). Midwives must develop their ability to interpret and understand the verbal communication of pain, and also body language, in order to address the needs of individuals from culturally diverse groups (Finnström & Söderhamn 2006). Awareness of the cultural meanings of childbirth pain, how different women cope and are expected to behave, will assist in the provision of culturally competent care (Callister et al 2003). Cultural assumptions made by midwives, as any assumptions, may prevent individualized and appropriate care.

Impact of the environment on childbirth pains

Crafter (2000) postulated that the place of birth may have a significant impact on women’s experiences of pain in labour and birth because part of a culture is expressed through its environment and organization. The Peel Report (DHSS 1970) promoted changes in the place of birth for women, who had traditionally given birth to their babies at home. Hospitalization altered women’s views of birth, leading to a more medicalized birth with greater use of drugs for pain relief, which many women now accept as a normal part of the new environment. Crafter (2000) suggests that furnishings within a room may give women subliminal messages about the presiding culture. For example, an environment simulating the home may indicate behaviour of being in a home, whilst a hospital environment may promote behaviour for that environment.

If the hospital is the place of birth, a woman may adapt to this unfamiliar environment, which may distract her from identifying and adopting her own coping mechanisms during labour. Whilst individual coping strategies assist a woman’s physiology of labour, these may be utilized only by women who feel comfortable within their surroundings, such as in the home or birth centre. Women in a more clinical environment may more readily opt for pharmacological preparations to relieve their pain.

Choices for pain relief in labour

Against this background of psychological, cultural and physical factors that influence women’s experience of pain, preparation is required for individuals to feel ready to cope with their labour and to be able to make personal choices about managing the event. There are varieties of non-pharmacological and pharmacological methods from which women may choose. With an aim to make childbirth as intervention-free as possible, many women may begin by considering non-pharmacological methods, such as some of the complementary or alternative approaches.

Preparation for pain in childbirth

The potential value of antenatal education and preparation in reducing the fear and anxiety associated with childbirth was recognized by Grantly Dick-Read (1944) and Lamaze (1958). They proposed that labour was not inherently painful. Dick-Read (1944), who appears to be the original authority in this area, endorsed the view that pain was influenced by women’s socio-culturally conditioned fear and expectation of birth. They both suggested that labour pains could be controlled by psychoprophylactic techniques, such as muscle relaxation and breathing exercises. Dick-Read (1944) also postulated that providing information and encouraging women to communicate was useful in preparing women for pain in childbirth. The main goal of antenatal classes, which adopt these techniques, is based on empowering women to identify and develop their own body resources to enhance their childbirth experience (Gagnon & Sandall 2007).

The literature regarding the effectiveness of childbirth education is inconclusive (Koehn 2002). According to Spiby et al (2003), antenatal classes have been associated with increased ability to cope, lower levels of the affective aspect of pain and less use of pharmacological pain relief in labour. However, Lothian (2003) found that only 15% of the women in her study identified childbirth education classes as their source of information about pain relief, with most women depending on their midwives or doctor for explanations. With increasing technology, women may also easily access information through other sources, including the Internet. The Cochrane review by Gagon & Sandall (2007) recognized that the benefits of antenatal education for childbirth remain ambiguous though highlighted that the main body of literature suggests that some expectant parents want antenatal classes, particularly with their first baby.

The content of antenatal classes related to pain management during labour needs to be developed. Antenatal course leaders should prepare women for their subjective experience of pain in labour (Schott 2003) by helping them to explore their own needs, attitudes and expectations of labour (Schneider 2001). Often women are not able to make choices about the management of their pain in labour because they are ignorant of their own body’s resources for coping with pain (Nolan 2000). Women will need brief information on the relevant physiology of pain (Robertson 2000) and be presented with a realistic but positive approach to pain in labour (Schott 2003).

During antenatal classes, women should be helped to explore and articulate the range of coping strategies they have used in their own previous experiences of pain, so the positive methods can be enhanced and negative strategies can be replaced with an alternative (Escott et al 2004). It is not unheard of that in labour, when in a mood of panic and acute anxiety, women claim to have forgotten how to ‘breathe’. Antenatally, if they have been encouraged to recall and develop their own pre-existing methods of tolerating pain, it may be easier for them to develop a greater sense of self-efficacy to deal with their labour pains (Escott et al 2005).

Concept of support in labour

Women need to feel supported during labour. This may take the form of informational, practical or emotional support (Hodnett et al 2007) which are all essential elements in the art of midwifery (Berg & Terstad 2006). Support in labour impacts on the sympathetic element of the autonomic nervous system, by breaking the fear–tension–pain cycle observed by Dick-Read (Mander 2000).

A correlation study in the US by Abushaikha & Sheil (2006) examined the relationship between the feeling of stress and support in labour. The findings suggested that women with greater support reported less stress compared to those who received little.

The main sources of support for some mothers are the midwife and the woman’s partner. However, these sources are reliant on the society and culture to which the woman belongs. The findings of a literature review suggested that support for women varies in different countries. This support includes untrained lay women, female relatives, nurses, monitrices (midwives who were self-employed birth attendants) and doulas (Rosen 2004).

McGrath & Kennell (2008), in a randomized controlled trial, reported that women who were supported by a doula required less analgesia compared to those in the control group. A doula is an experienced woman who supports women in childbirth to enable them to achieve a rewarding birth experience (Koumouitzes-Dovia & Carr 2006). They provide care which is continuous and addresses psychological as well as the physical processes of childbirth (Pascali-Bonaro & Kroeger 2004). In the UK, doulas may be used as a supportive friend for vulnerable women who may not have access to such support from their own family.

Koumouitzes-Dovia & Carr (2006) examined women’s perception of their doula support. They found that the emerging underlying themes highlighted that women felt doulas were a source of reassurance and encouragement who also provided support for their husbands. Berg & Terstad (2006), in a phenomenological study conducted in Sweden, supported these findings. They found that a doula acted as a mediator between partners, and the midwife provided stability, which made the woman calm and secure.

One of the main benefits of care by a doula is that of continuous support. In a Cochrane systematic review (Hodnett et al 2007), which consisted of 16 trials involving 13,391 women, it was demonstrated that women who had continuous support intrapartum, were more likely to have shorter labours and less likely to have analgesia. The benefit of this support was greater when the provider was not a member of the hospital staff.

Complementary and alternative therapies for pain relief

Complementary and alternative therapies (see Ch. 18) involve practices that are not categorized as conventional medicine (Smith et al 2006). The evidence regarding the efficacy of commonly used therapies in relieving pain is inconclusive (Huntley et al 2004), partly owing to a lack of relevant studies. The National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (NCC-WCH 2007) recommended that women who want to use acupuncture, acupressure and hypnosis should not be discouraged from engaging in these practices. However, it does not encourage a standard provision of such services. There is support for other forms of coping strategies such as music and massage but more research is required in this area (Kimber et al 2008, McNabb et al 2006, NCC-WCH 2007, Nilsson 2008). Two complementary therapies that are commonly used in midwifery practice are described below.

Hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy is increasingly being used worldwide to provide comfort for women in labour. It is well known that a warm bath is useful for relaxation and is a simple means of reducing muscular aches and pains. There is evidence to suggest that immersion in water during the first stage of labour decreases reports of pain and the use of analgesia, without any adverse effects on the duration of labour or neonatal outcome (Cluett et al 2002). The mechanism which underpins hydrotherapy in labour is unclear (Benfield 2002) but it is thought that warm water decreases the perception of pain by stimulating the larger A delta nerve fibres blocking impulses from the smaller C fibres (Teschendorf & Evans 2000) in accordance with the gate control theory.

As women relax in the water there is a decrease in anxiety and rapid reduction in the sensation of pain (Benfield 2002). Labouring in water also enables women to move and change positions to facilitate progress in labour (Stark et al 2008), making it possible for them to play a more active part in their experience of birth (da Silva et al 2009). Women in a study by Maude & Foureur (2007) suggested that they felt protected, supported and comforted while using the water. They choose to use water to reduce their fear of pain and to cope rather than remove it.

It has been postulated that the environment in which the pool/bath is situated and the interaction with the caregivers has a significant part to play on the effect water has on women in labour (Cluett et al 2002). Therefore, the ambience created by the environment of the water pool has importance. For example, there could be a difference between the effects of labouring in a bath in a hospital setting compared with in one that is situated in a specially designed birthing unit, or located in the woman’s own home.

Women relax and may become drowsy whilst in the water. The midwife must ensure the woman’s safety, particularly should she require additional analgesia, such as Entonox. Women must not be left unattended in a water pool. The temperature of the woman and the water need to be monitored hourly and the water temperature should be maintained below 37.5°C (NCC-WCH 2007). This will ensure that the woman does not become hyperthermic, as this may have adverse effects on the fetus. It remains unclear what the shape and size of the pool should be, and whether the water should be still or moving, as these aspects require further evaluation (Cluett et al 2002). However, women should have the opportunity to labour in water as a form of pain relief (NCC-WCH 2007).

Reflective activity 38.2

When you are next caring for a woman during labour, consider suggesting that she try different positions to cope with contractions. Which positions are the most effective? After the delivery, discuss the woman’s opinion of what difference this made to her perception of pain.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

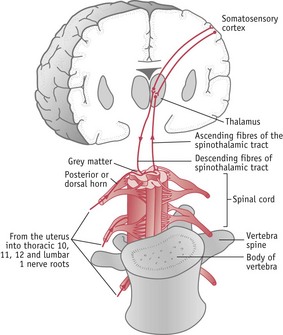

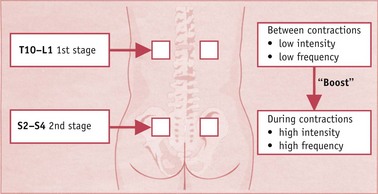

TENS is the application of pulsed electrical current through surface electrodes placed on the skin parallel to and on each side of the spine (see Fig. 38.3). TENS produces small electrical sensations and is thought to assist in the prevention of the perception of pain at spinal level, stimulating naturally occurring endorphins and blocking pain (Rodriguez 2005).

Figure 38.3 TENS electrode positioning for use during labour

(From Johnson 1997, with permission of Mark Allen Publishing Ltd.)

The advantages of TENS are that it is a non-invasive form of pain relief that may be used effectively whether the mother is mobile or in bed, with no effect on the fetus or the woman systemically. It gives the woman a feeling of control and some responsibility for managing her own relief of pain (de Ferrer 2006). When commenced early in labour, it enables the endorphins to build up naturally as labour progresses and become more effective (Price 2000b). TENS should not be used for women in established labour as it takes about 40 minutes for the maximum endorphin level to be reached (Rodriguez 2005).

Placed in the correct position, the electrodes supply a residual voltage, which can be boosted by the woman during a contraction. This provides the woman with autonomy and helps her achieve greater emotional fulfilment from the experience of childbirth. Anecdotal evidence from women suggests that only when the electrodes are taken off in labour do they realize how useful TENS has been.

Pharmacological pain relief

Midwives should be able to give advice and explain the side-effects of pharmacological pain relief that meets the woman’s needs for control and comfort without causing any harm (Green 2008). This means midwives should keep up to date with current medications and their side-effects and follow unit policies at all times (NMC 2008). An understanding of pharmacokinetics, including the changing drug absorption, metabolism, distribution and excretion in both the woman’s body and that of her fetus and baby, is important in providing information and advice to the woman regarding choices of pain relief (see Ch. 10).

Reflective activity 38.3

When you are next on the labour ward, take an opportunity to observe the level of support a woman receives during labour and from whom.

What effect do you observe on the process of labour, and on the outcome?

Was the quality and quantity of support the same as you would observe in a home setting, or birth centre? If not, what were the key factors influencing this?

Nitrous oxide

The use of inhalation analgesia for pain relief in childbirth originated from the work of Simpson of Edinburgh in 1847, who introduced chloroform for anaesthetic purposes (Crowhurst & Plaat 2001). Nitrous oxide, known as ‘laughing gas’, has been widely used in midwifery since the 1930s. It is used in labour in a mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen as Entonox. It is supplied in small portable cylinders (Fig. 38.4) or piped directly to the delivery suite.

The two gases separate at cold temperatures, which leaves nitrous oxide at the bottom of the cylinder. Inverting the cylinder before use, warming in water or keeping at room temperature for 2 hours before use prevents the administration of 100% nitrous oxide (Anaesthesia UK 2008).

Entonox has a sedative effect in use but is not an analgesic and is self-administered by the use of a mouthpiece or mask. It is used by many women and may give them a sense of control but not total pain relief. Women should be warned about the side-effects of dry mouth or even vomiting (NCC-WCH 2007) and disorientation. The gas will only cause unconsciousness if the woman is hypoxic or if the partner is assisting in holding the apparatus. causing continuous aspiration. The effects are quite rapid, commencing 20 seconds after administration with a maximum effect at 60 seconds. It is important that deep breathing at the normal rate is encouraged. To obtain effective relief from pain at the height of the contraction, inhalation should commence immediately as the contraction begins.

Entonox is widely used in the UK and it has been suggested that respiratory depression occurs in the mother when it is combined with opioids (Yeo et al 2007). There is complete absorption through the placenta (Yentis et al 2007). The amount absorbed by the mother rapidly gains equilibrium in the fetus, but, equally so, it is rapidly cleared from the fetal system when the mother stops inhalation. Rosen’s (2002) review of randomized controlled trials regarding the efficacy and safety of Entonox suggests that it does not give total pain relief but is generally safe for both mother and fetus.

Systemic analgesia

Pethidine

The objective of using analgesic drugs in labour is to achieve an acceptable level of pain relief without compromising the health of the mother or fetus. Opioid analgesics include the morphine-like substances derived from the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) which induce ‘euphoria, analgesia and sleep’ (RPSGB & BMA 2008). Included in this group would be morphine, diamorphine, fentanyl, remifentanil and meptazinol (RPSGB & BMA 2008). Pethidine, a derivative, has been widely used in midwifery for women in labour since the 1950s and still continues to be used despite the effect opioids have on the mother and the fetus. Pethidine is a synthetic substance, shorter acting than morphine. It does give women some relaxant effect but occasionally causes nausea and vomiting. Its effect is rapid and lasts for approximately 3–4 hours but it is a less effective analgesic than morphine (RPSGB & BMA 2008). It may be given intramuscularly or as an intravenous injection or as an infusion, which may be self-administered. In practice, it is more often administered as a bolus intramuscular injection. The dose ranges from 50 to 200 mg, with no more than 400 mg in 24 hours (RPSGB & BMA 2008), and is dependent on the route of administration, the woman’s weight, degree of pain, stage of labour and the rate of progress. A survey of UK units showed that where regional analgesia was either contraindicated or impossible to perform, pethidine or diamorphine (heroin) was used as a bolus or in the form of patient-controlled analgesia (Saravanakumar et al 2007).

Physiological action on the mother

Pethidine binds to receptor proteins to diffuse through cell membranes to exert its effect within the central nervous system. Its action at the cellular level alters potassium and calcium channels, affecting ion exchange in the neuronal membrane and calming the excitability of the nerve as it reacts to the pain-producing substances. It acts on efferent nerve pathways descending from the brain at the dorsal horn, thus playing a role in the ‘gating’ of pain at the spinal column level (Rang et al 2007). It is metabolized by the liver to norpethidine (normeperidine in America) by a process termed n-demethylation, which produces a substance that has half the potency of the original and has a stimulant, convulsive effect (RPSGB & BMA 2008). To prevent the side-effect of nausea and vomiting, 73.7% of UK units use a prophylactic antiemetic with pethidine (Tuckey et al 2007).

Physiological effects on the fetus

Diffusion across the placenta occurs readily, and equilibrium between maternal and fetal levels is easily achieved. This depends on the lipid solubility of the drug and its molecular weight. The lower pH levels of the fetus relative to the mother would suggest a greater transfer of the active drug (Littleford 2004). The route of administration is also important when considering fetal effects. Following an intravenous dose of pethidine, the drug has been found in the cord blood within 2 minutes; after intramuscular administration, within 30 minutes (Briggs et al 2008). Undoubtedly, pethidine passes from mother to fetus very readily, as does the metabolite norpethidine, and this is dose dependent. The fetus will also produce norpethidine and the levels in the fetal circulation may be higher than in the mother. The fetus may be more susceptible to the effects of this type of medication because of the immaturity of the blood–brain barrier and the fetal bypass of the liver, where it would normally be metabolized (Briggs et al 2008). Babies were found to be less alert, quicker to cry when disturbed, and more difficult to settle.

If the birth of the baby follows within 2–5 hours of administration, there may well be more respiratory depression in the neonate; furthermore, although this is the peak time range for neonatal effect, it may also occur if delivery occurs prior to 2 hours (Hunt 2002). Plasma half-life of pethidine in the maternal system is 3–4 hours and the substance has been found in the neonate’s saliva 48 hours after birth (Briggs et al 2008).

Antagonist to pethidine

Naloxone is an antagonist, blocking the receptors to which the pethidine binds and thus blocking the action of pethidine and its consequent depressant effect on respiration. It may be given via the intramuscular route in doses of 10 mcg/kg body weight (RSPG & BMA 2008). However, it should not be given routinely as there are no studies to recommend its use in this way (Guinsburg & Wyckoff 2006, Wyllie 2008). It is contraindicated if the mother is narcotic dependent (Littleford 2004).

The lumbar epidural

The epidural is a very effective form of pain relief. The midwife can observe the change in a woman’s whole demeanour following its use. It is, however, an invasive technique that requires an anaesthetist (Bamber 2006). The risks and the benefits must be fully discussed and understood by the woman, so that she may make an informed decision. Throughout the induction procedure, the midwife should support the woman and her partner both physically and psychologically. The fetal heart rate must be monitored and record-keeping must be maintained.

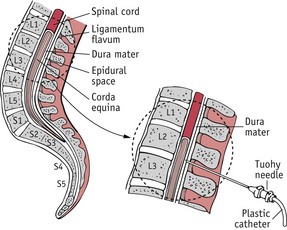

An epidural is inserted in the space between the second and third lumbar vertebrae. This is made easier by increasing the flexion of the spine. The tough ligamentum flavum has to be overcome prior to the insertion of the needle into the 1–7-mm thick potential epidural space (Fig. 38.5) between the dura mater and arachnoid mater. The epidural space contains blood vessels, nerve roots and fat and is triangular in shape (Fernando & Price 2002). At the level of the first lumbar vertebra, the spinal cord becomes a collection of nerve fibres termed the cauda equina, which, as its Latin name suggests, resembles a horse’s tail (Tortora & Grabowski 2000). Although anatomically the epidural space runs the length of the spinal column, occasionally the epidural injection is unsuccessful and it is believed that there may be folds in this membrane diverting the flow of analgesia away from the nerves (Russell & Reynolds 1997).

Figure 38.5 Epidural induction: insertion of the Tuohy needle.

(Reprinted from Pain in childbearing, Yerby M (ed), 2000, by permission of the publisher Baillière Tindall.)

Following cleansing of the skin and application of local anaesthetic a Tuohy needle is carefully inserted into the potential space. This large-bore needle with centimetre marking and a bevelled end aids with insertion and positioning of a fine catheter (MacIntyre 2007). Smaller-gauge needles are used for spinals and could prevent dural tap (Sprigge & Harper 2008) (Fig. 38.6). The catheter is left in situ; the injection of bupivacaine into this potential space will block the autonomic nerve pathways that supply the uterus. The epidural analgesia is maintained through regular top-ups by the midwife or by the woman, using bolus doses of the anaesthetic agent (Collis 2007). The current recommendation is 0.0625–0.1% bupivacaine or equivalent with 2.0 mcg/mL fentanyl (NCC-WCH 2007).

Figure 38.6 Epidural induction: Tuohy needle positioned in the epidural space.

(Reprinted from Pain in childbearing, Yerby M (ed), 2000, by permission of the publisher Baillière Tindall.)

Physiological effects of the epidural

The injection of bupivacaine into the epidural space bathes the nerves of the chorda equina, blocking the autonomic nerve pathways that supply the uterus, thus changing action potentials in the nerve and preventing pain. The epidural analgesic acts on the sympathetic nervous system by altering adrenaline and noradrenaline levels in the blood (May & Leighton 2007). Lederman et al (1978) suggested that by decreasing the levels of these catecholamines, uterine activity may be improved, as high levels tend to lengthen labour.

The effect on the autonomic nervous system produces vasodilatation in the peripheral circulation, causing the extremities to feel warm, a good test that the epidural is working. However, pooling of the circulation in the periphery may cause hypotension, as there is a loss of peripheral resistance in the lower limbs. This is usually controlled by increasing intravenous fluids and repositioning the woman. If there is no sign of recovery, the anaesthetist should be informed immediately to administer a bolus dose of a vasopressor, such as ephedrine. The placental bed is unable to compensate for lowered delivery of blood to the uterus, so bradycardia in the fetus may be a problem (O’Connor 2007).

As sensation is lost, normal micturition may be affected; this does have implications on bladder care in labour to prevent postnatal urinary retention (Liang 2002). Women tend to have fewer problems with micturition when low-dose epidurals are used (Wilson et al 2009).

The pelvic floor muscles are somewhat relaxed and this may have a detrimental effect on fetal head rotation and lengthen the process of birth (Odibo 2007). In addition, the second stage could be longer because women may not feel the sensation to push. If the fetal condition is satisfactory, delayed pushing seems to decrease the need for instrumental deliveries (Roberts et al 2005) and does not appear to increase the number of caesarean sections. NCC-WCH (2007) recommend delaying pushing for 1 hour after diagnosis of second stage, with delivery of the baby before the completion of 4 hours.

Other complications

Respiratory arrest

This may be caused by the accidental induction of a high nerve block or the injection of bupivacaine into a vein. The first sign will be a tingling tongue with a rapid deterioration; therefore, the midwife needs to be prepared for immediate resuscitation.

Dural tap

This occurs in 0.5–2% persons receiving regional anaesthetics; 70–80% of these will develop a postural headache. This is caused by a lowering of pressure of circulating cerebrospinal fluid, causing a stretching of brain tissue, in turn causing pain. Rest is important following the procedure, to prevent more spinal fluid leakage increasing headaches until the dura is healed. It can be treated with an autologous blood patch of 10–20 mL of the patient’s own blood injected near the site of the epidural to seal the dura. Serious complications are rare following this procedure (O’Connor 2007).

Long-term backache

During pregnancy and labour, ligaments are altered by the hormones of pregnancy, which permits some movement, increasing pelvic size to facilitate birth. Backache is a common complaint in pregnancy and following birth. A Cochrane Update (Anim Samuah et al 2005) concluded that epidurals created more instrumental deliveries but there was no statistical evidence to suggest that epidurals caused long-term backache or increased the incidence of caesarean section.

The latest Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) (Lewis 2007) states that the risk of death from regional anaesthesia is 1:100,000 parturiants.

Conclusion

Pain is a multifaceted phenomenon of pregnancy, without which women would not know they were in labour. Psychological factors affect women’s perceptions of pain in labour, and though education helps to decrease anxiety, it has not been proven by research to lessen women’s pain. Support has been shown to be valuable, whether by partner, midwife or doula, and is valued more when care is continuous from a known midwife. Women with continuous support seem to require less pain relief, but when a labour becomes long and pain increases, women tend to require systemic pain relief. Pethidine seems to be used less often in today’s delivery suites in favour of the more effective epidural analgesia, though both methods of pain relief have side-effects. Research should continue to investigate women’s needs and the production of systemic analgesia that is safe in labour for both mother and fetus. Midwives should continue to develop their skills in supporting women in labour whether with or without pain relief.