Chapter 36 Care in the first stage of labour

Introduction

Labour and birth are an amazing integration of powerful physiological and psychological forces that bring a new human life into the world. It is difficult not to devalue labour and birth when it is analysed, dissected and examined in order to make it understood, as it works best as a coherent whole. There are key physical, emotional and social dimensions to the process of labour, in that the arrival of a baby heralds the birth or extension of a family. Throughout history, labour and birth had special meaning for every culture and their occurrence is often marked by spiritual and cultural symbols (Kitzinger 2000). In the UK today, such rituals have been marginalized by the medical environment in which most parturition takes place, with about 95% of births occurring in consultant units, 2.5% at home (Richardson & Mmata 2007) and 2.5% in free-standing midwifery-led units (Walsh 2007a). For the midwife, a holistic understanding of labour and birth requires an awareness of the physiological/psychological changes and ability to see these remarkable events as deeply social and even political. This perspective has, as a starting point, a profound respect for and trust in women’s innate ability to birth without technology or medical intervention. The chapter will attempt to describe the changes, the events and the care from these philosophical positions.

Two birth stories (Case scenarios 36.1 and 36.2) reveal the complexity of labour and birth.

![]() Case scenario 36.1

Case scenario 36.1

Emily’s birth story

Emily was a ‘no-nonsense’ sort of person. She approached the birth of her first baby in a straightforward way. ‘I’ll know what to do at the time’, she kept telling me. ‘You just tag along and I’ll ask if I need anything.’ She called me out one Sunday morning and when I arrived told me her labour had started, and although she didn’t want me to do anything, she asked me to stay for a few hours. Later, she said I could go as she had hours to go yet. She called me again early the next morning and said it was time for the baby to come. I drove over to her house, and 2 hours later her son was born into the birthing pool and there were tears all round. Emily was in tune with her body. She understood it and how the birth process would go for her far better than I did.

![]() Case scenario 36.2

Case scenario 36.2

Judy’s birth story

Judy just avoided induction of labour because she was 13 days past her due date when her waters broke. The contractions arrived 8 hours later and were huge from the start. Despite fantastic support from Ben, her partner, she felt out of control with the labour’s intensity. Her cervix was 7 cm dilated when she requested a vaginal examination 2 hours later. After an hour, her contractions became even more intense and I suspected she was approaching the pushing phase. Then suddenly, everything stopped. She dozed on and off for 4 hours, when suddenly she was bearing down and the baby was born within two contractions. Judy felt traumatized by her rollercoaster ride, which she felt swept along by.

The midwife’s description of these births shows how the experience of labour can vary for different women. The time spans were different – the first in excess of 24 hours and the second had a ‘rest phase’ of 4 hours prior to the birth. The women adapted to their experience in contrasting ways – one confident and controlled, the other feeling swamped by the power of her labour. In neither case is the midwife’s role described, but different strategies of support would have been required to care appropriately for each woman.

Other aspects are key to assisting our understanding of these births. Both babies were born at home. Both women had people in attendance whom they knew and had chosen to be there. Neither woman had any drugs, nor common birth interventions. They did it ‘naturally’. Their births were not typical of 21st-century childbirth experience in the UK. More typically, childbirth occurs in hospital with carers who have not been previously met, using routine interventions including continuous electronic fetal monitoring. One in three results in an instrumental vaginal delivery or a caesarean section (Richardson & Mmata 2007). It could be argued that normal labour and birth is under threat, with only about 47% of women in England having a drug-free normal birth (Richardson & Mmata 2007).

Being in hospital requires conforming to an environment where the woman inevitably becomes a ‘patient’ and carers assume the status of experts. Labour is expected to conform to protocols and policies designed for the ‘average’, triggering a range of interventions if deviation occurs from this ‘average’. This chapter explores normal labour and birth from the perspective of non-intervention, viewing the birth environment as crucial to physiological processes. Having a baby in hospital may be viewed as a ‘care intervention’, likely to upset a delicate balance of physical, psychological and social processes that need to work in harmony for birth to be humane and life-enhancing.

The continuum of labour

Labour has been traditionally divided into stages but this demarcation has its origins in a preoccupation with the time duration of each stage and its historical link to complications for the mother and baby. When learning about labour, practitioners are introduced to notions of time at the outset, which is consistent with a biomedical understanding of parturition that anticipates pathology in an effort to treat it as early as possible.

An alternative approach is beginning to gain exposure through the writings of midwives like Downe & McCourt (2008), where labour is a continuum from onset to completion, characterized by particular physiological and psychological behaviours at various points on that continuum. Some of these behaviours are anatomical changes, for example, changes in the cervix; some are physiological, such as release of body hormones; and some psychological, such as an alertness and focusing just prior to birth.

Individual behaviours and responses vary, and the importance of knowing and intuitively connecting with women is a key challenge for the midwife and allows care to be appropriate and tailored to individual need.

Although the demarcations of the stages of labour in the traditional biomedical model are intended to aid clarity in understanding physiology and care for the professional caregiver, they may also effectively silence the woman and discredit her version of events. For the woman, labour is a continuing physiological, psychological and emotional experience, the culmination and main focal point of the reproductive process, where artificial compartmentalization may be neither relevant nor important. The significance of labour, a biologically and socially creative life event, is reflected in the minutiae of detail women can recall about their particular labour(s). Events that are relatively common and usual from a midwife’s perspective, acquire much meaning and importance in the eyes of the woman and her family. To maximize the potential for a satisfactory outcome of labour, it is therefore essential that women’s stories and details of events are listened to and valued.

Reflective activity 36.1

Ask your mother about your birth and note the phrases she uses to describe it, the memories that have stayed with her and the overall impression of the experiences that she communicates to you. If you are not able to do this, ask another woman that you know well to talk about her birth experience.

If the midwife anticipates a normal outcome to labour and birth, and trusts the woman’s physiology will function optimally, this can impact positively on the woman’s own attitude. Women with an optimistic demeanour towards childbirth have better experiences and outcomes than those beset by anxiety and fear of what could go wrong (Green et al 1998). Midwives play a key role in empowering women as they approach childbirth.

Characteristics of labour

Normal labour naturally follows a sequential pattern that involves painful regular uterine contractions stimulating progressive effacement and dilatation of the cervix with descent of the fetus through the pelvis, culminating in the spontaneous vaginal birth of the baby, followed by the expulsion of the placenta and membranes. This traditional and orthodox biomedical definition of normal labour divides labour into three stages, and designates maximum time frames, depending on a woman’s parity, as shown in Table 36.1:

Table 36.1 Approximate time taken for each stage of labour

| Primigravidae | Multigravidae | |

|---|---|---|

| First stage | 12–14 hours | 6–10 hours |

| Second stage | 60 minutes | Up to 30 minutes |

| Third stage | 20–30 minutes, or 5–15 minutes with active management | 20–30 minutes, or 5–15 minutes with active management |

The social model is more holistic and has contrasting values to the biomedical model (Table 36.2).

Table 36.2 Medical and social model

| Medical model | V | Social model |

|---|---|---|

| Body as machine | Whole person | |

| Reductionism – powers, passages, passenger | Integrate – physiology, psychosocial, spiritual | |

| Control and subjugate | Respect and empower | |

| Expertise/objective | Relational/subjective | |

| Environment peripheral | Environment central | |

| Anticipate pathology | Anticipate normality | |

| Technology as master | Technology as servant | |

| Homogenization | Celebrate difference | |

| Evidence | Intuition | |

| Safety | Self-actualization |

The alternative values of the social model mean that the strenuous work of labour is acknowledged as fundamental. Gould (2000) acknowledged this along with the crucial role of movement. This highlights the courage and perseverance demonstrated by women as they ‘work’ during labour and the importance of an environment where movement will be facilitated.

Physiology of labour

Several physiological factors integrate as labour develops (Box 36.1), and these will be examined in turn.

Box 36.1

Summary of the physiological changes in the first stage of labour

Cervical effacement and dilatation

These occur as a result of contraction and retraction of the uterine muscle.

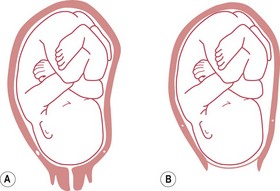

Effacement (taking up) of the cervix may start in the latter 2 or 3 weeks of pregnancy and occurs as a result of changes in the solubility of collagen present in cervical tissue. This is influenced by alterations in hormone activity, particularly oestradiol, progesterone, relaxin, prostacyclin and prostaglandins (Blackburn 2007). Braxton Hicks contractions, which become stronger in the final weeks of pregnancy, may also enhance the process. Effacement is completed in labour, the cervix becomes shorter and dilates slightly, becoming funnel shaped as the internal os opens to form part of the lower uterine segment (see Fig. 36.1).

Figure 36.1 The uterus, showing: A. cervix before effacement; and B. effacement and dilatation of the cervix and the stretched lower uterine segment.

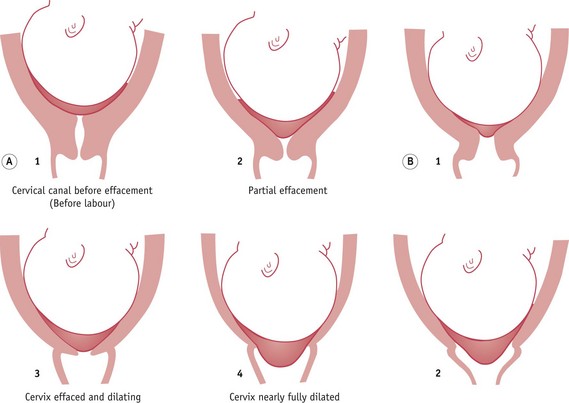

Progressive dilatation of the cervix (see Fig. 36.2) is a definitive sign of labour.

Figure 36.2 Effacement and dilatation of the cervix: A. in a primigravida; B. occurring simultaneously in a multigravida.

When the cervix is dilated sufficiently to allow the fetal head to pass through, full dilatation has been achieved. Although this is usually 10 cm, it may be more or less depending on the size of the fetal head.

In primigravidae, effacement of the cervix usually precedes dilatation; however, in multigravidae, effacement and dilatation of the cervix normally occur simultaneously (see Fig. 36.2).

Uterine contractions

Uterine contractions are responsible for achieving progressive effacement and dilatation of the cervix and for the descent and expulsion of the fetus in labour. Contractions of the uterus in labour are:

The pain may be due in part to ischaemia developing in the muscle fibres during contractions. The backache which may accompany cervical dilatation is caused by stimulation of sensory fibres which pass via the sympathetic nerves to the sacral plexus.

Coordination of contractions

Contractions start from the cornua of the uterus, passing in waves, inwards and downwards. In normal uterine action, the intensity is greatest in the upper uterine segment and lessens as the contraction passes down the uterus. This is called fundal dominance. The upper segment of the uterus contracts and retracts powerfully, whereas the lower segment contracts only slightly and dilates. Between contractions the uterus relaxes.

The coordinated uterine activity characteristic of normal labour occurs as a result of near-simultaneous contraction of all myometrial cells. During pregnancy, increasing numbers of gap junctions form between the cells of the myometrium. These low-resistance communication channels enhance electrical conduction velocity and facilitate the coordination of myometrial contraction (Blackburn 2007).

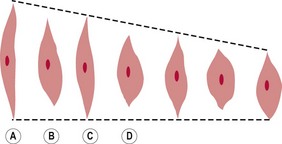

Retraction

Retraction is a state of permanent shortening of the muscle fibres and occurs with each contraction (see Fig. 36.3).

Figure 36.3 Retraction of the uterine muscle fibres: A. relaxed; B. contracted; C. relaxed but retracted; D. contracted but shorter and thicker than those in B.

The muscle fibres gradually become shorter and thicker, especially in the upper uterine segment. This exerts a pull on the less-active lower uterine segment, the maximum pull being directed towards the weakest point, the cervix, and the os uteri. Hence the cervix is gradually ‘taken up’, or effaced, and the upward pull then dilates the os uteri.

As the space within the upper uterine segment diminishes with the contraction and retraction of the muscle fibres, the fetus is forced down into the lower segment and the presenting part exerts pressure on the os uteri. This aids dilatation, and also causes a reflex release of oxytocin from the posterior pituitary gland, promoting further uterine action. A ridge gradually forms between the thick, retracted muscle fibres of the upper uterine segment and the thin, distended lower segment. This is called a retraction ring – a normal physiological occurrence in every labour.

Polarity

The rhythmical coordination (polarity) between the upper and lower segments is balanced and harmonious in normal labour. While the upper segment contracts powerfully and retracts, the lower segment contracts only slightly and dilates.

Intensity or amplitude

Contractions cause a rise in intrauterine pressure – the intensity or amplitude of contractions – which can be measured by placing a fine catheter into the uterus and attaching it to a pressure-recording apparatus. Each contraction rises rapidly to a peak and then slowly declines to the resting tone. In early labour the contractions are weak, with an amplitude of about 20 mmHg, last 20–30 seconds and occur without any particular pattern. As labour progresses, the contractions become stronger, longer and more frequent. At the end of the first stage they are strong, with an amplitude of 60 mmHg, last 45–60 seconds and occur every 2–3 minutes.

Resting tone

The uterus is never completely relaxed, and between contractions a measured resting tone is usually 4–10 mmHg. During contractions the blood flow to the placenta is curtailed; thus, oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange in the intervillous spaces is impeded. The period of relaxation between contractions when the uterus has a low resting tone is therefore vital for adequate fetal oxygenation.

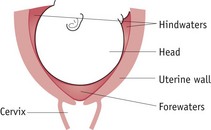

Formation of the forewaters and hindwaters (Fig. 36.4)

As the lower uterine segment stretches and cervical effacement commences, some chorion becomes detached from the decidua and both membranes form a small bag containing amniotic fluid, which protrudes into the cervix. When the fetal head descends onto the cervix, it separates the small bag of amniotic fluid in front, the forewaters, from the remainder, the hindwaters. The forewaters aid effacement of the cervix and early dilatation of the os uteri, and the hindwaters help to equalize the pressure in the uterus during uterine contractions, providing some protection to the fetus and placenta.

Rupture of the membranes

The membranes are thought to rupture as a result of increased production of prostaglandin E2 in the amnion in labour (McCoshen et al 1990) and the force of the uterine contractions, causing an increase in the fluid pressure inside the forewaters and a lessening of the support as the cervix dilates. In normal labour the membranes usually rupture during the second stage of labour.

Show

The ‘show’ is the operculum from the cervical canal passed per vaginam in labour, displaced when effacement of the cervix and dilatation of the os uteri occur. It is usually mucoid and slightly streaked with blood due to some separation of the chorion from the decidua around the cervix.

There is increasingly awareness of the relationship between oxytocin release and the level of catecholamines (see Ch. 35). Anxiety and fear stimulate the release of adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine), and inhibit oxytocin; hence the importance of birth environment and birth relationships in promoting calm and confidence in birthing women.

Care during the first stage of labour

The aims of midwifery care in labour are to achieve a safe labour and birth for mother and baby, and a pleasurable, fulfilling experience of childbirth for the mother and her partner.

Now that deaths in childbirth for women and babies in the western world are rare, women’s experience of childbirth has taken on greater significance and has become a major focus for the professionals assisting childbirth. Most early research on labour and birth did not explore women’s experiences and was based around professionals’ priorities and their interests. Recent studies have determined women’s views on various aspects of care (Lally et al 2008, Redshaw et al 2007, Rudman et al 2007) and these can be summarized under the following themes:

These themes should underpin the philosophy of care and its application, helping to define woman-centred care, as described and endorsed in maternity care policy at government level (DH 2007a, 2007b).

In order to provide woman-centred care, the midwife should:

Partnership in care

The relationship between the woman and her midwife is ideally a partnership (Pairman 2000) which should begin in pregnancy, and has been described as ‘skilled companionship’ or the ‘professional friend’ in its intimacy and reciprocity (Page 1995). The partnership ethos requires a social rather than medical model of maternity care, endorsing the involvement of the woman and her partner in decision-making, and requiring the woman to be able to voice her needs and wishes freely. The midwife should strive to build a relationship of mutual trust and create an environment in which expectations, wishes, fears and anxieties can be readily discussed. This requires good communication, which results from a two-way interaction between equals.

Emotional and psychological care

The midwife needs to have a good understanding of a woman’s feelings in labour. Attitudes and reactions to childbirth vary considerably and are influenced by differing social, cultural and religious factors. For a multigravida, previous experience of birth will also be important.

Many women anticipate labour with mixed feelings of fear and excitement. Some may eagerly anticipate the birth, confident in their ability to cope, seeing birth as an emotionally fulfilling and enriching experience involving all immediate family members. They may have attended teaching sessions for natural or active childbirth and have a particular plan of action for their labour. Others may be excited at the prospect of actually seeing their baby, yet fearful of labour and anxious about their ability to cope with pain and ‘perform’ well. Some expect labour to be painful and unpleasant, controlled by obstetricians and midwives to be achieved with as little pain and active participation as possible.

The woman may be apprehensive about entering an unknown, and perhaps threatening, hospital environment and concerned about relinquishing her personal autonomy and identity. Alternatively, expectations of labour may be unrealistic, and may be unfulfilled, leading to feelings of disappointment, failure or loss. Multigravidae are often anxious about children they have left at home. The midwife can do much to alleviate these worries.

Birth partners may also have particular concerns which they feel unable to share. Reservations may be influenced by the role society attributes to gender – a man being expected to be strong and able to cope; or may be due to fear of the unknown and concern for someone who is loved. With a partnership and individual approach to care, particularly if established during the antenatal period, the midwife has a valuable opportunity to encourage the couple to voice their particular needs and anxieties, and explore and agree ways of dealing with them. Whatever the needs of the individual couple, they are usually influenced by the desire to do what is best for their baby and, if they are confident that the midwife will respect and comply with their wishes in normal circumstances, they will usually readily agree to modify expectations should problems arise.

Throughout labour there should be a free flow of information between the woman, her partner and the midwife, particularly in relation to examinations and their findings. Being fully informed and involved in decision-making helps the woman to retain a sense of autonomy and control (Healthcare Commission 2008). The midwife should be aware that not all individuals may feel sufficiently secure or freely able to express fears or anxieties during labour. Circumstances such as an unwanted pregnancy, fear or previously poor relationships with professional caregivers may engender feelings of unhappiness, hostility and resentment. The midwife needs to be particularly sensitive to non-verbal indicators of such feelings and give the necessary help and support needed by the woman.

The role of the birth supporter

Evidence from a number of studies indicates the positive effect of continuous support in labour (Hodnett et al 2008a). Although it is usual in the UK for a couple to support each other in labour, some women may choose to have a relative, friend, or labour supporter from a voluntary organization, such as the National Childbirth Trust (NCT), as labour companions. Whoever has been chosen, the midwife should explore with supporters their experiences of childbirth, their role expectations during labour and their ability to undertake the supporter role. It has been suggested that if chosen supporters have had negative childbirth experiences, these need to be addressed by the midwife if they are not to hinder the supporting relationship with the woman.

The midwife involves the birth supporter as part of the team, with a defined role, which can include massaging back, abdomen or legs, helping with breathing awareness and relaxation, and offering drinks and other means of sustenance. Such activities, during a highly anxious time, can be very valuable in helping the partner to feel usefully occupied and involved in the birthing event.

The midwife must be sensitive to the possible need for personal space and privacy and should judge when, and if, it is appropriate to leave the woman and partner alone. This is usually more acceptable in early labour but less so when labour is strong and well advanced, when to be left alone might be frightening. If the midwife must leave for a short period, she must ensure that the couple can summon help if necessary. The midwife must also be sensitive to the emotional needs of the partner and other members of staff and recognize that, particularly during a long labour, a short break may be beneficial in helping to replenish energy levels.

Advocacy

For some women, fear of the unknown, being cared for in hospital by unfamiliar people, greater pain than expected or the effect of analgesic drugs can cause feelings of vulnerability, loss of personal identity, and powerlessness. This may be magnified for women for whom English is not their first language. Vulnerable individuals can lose the ability to adequately express their needs, wishes, values and choices and adopt a passive recipient role. The midwife may need to act as advocate, in order to ensure that personal needs are met (Walsh 2007b). This includes informing, supporting and protecting women, acting as intermediary between them and obstetric and other professional colleagues, and facilitating informed choice. In order to achieve this, the midwife must be professionally confident, have a clear awareness of the woman’s needs, and be able to communicate these to other colleagues to ensure effective collaboration. Developing and trusting intuition is central to this activity. The midwife’s rapport and connectedness with the woman for whom she is caring mean that appropriate decision-making and a facilitatory birth environment is more likely (Walsh 2007a). Using these skills, the midwife is more able to empower the woman and her partner so that they feel sufficiently informed and confident to participate in decision-making during this important life experience.

Birth environment

Practitioners of normal birth and women themselves know how significant the birth environment is for the experience and outcomes of birth, including the birth setting, the relational components of care, and congruence of values about birth.

Home

Home birth has long generated an intense debate, and birth at home has become a rallying point for midwives and women who endorse childbirth’s essential normality against those who can only view its normality retrospectively. Tew (1998) first challenged the dominant 1970’s/1980’s view that the safest environment for birth was hospital. She exposed the fundamental flaw of assigning a single cause (hospitalization of birth) to a discrete effect (lowering perinatal mortality rates) without consideration of alternative explanations. This spurious logic had led to a nationwide movement of birth to hospitals over 20 years before an alternative explanation gained credibility – that the fall was due to the dramatic improvement in the general health of women in the post-war period coupled with an even more dramatic rise in living standards (Campbell & McFarlane 1994, Tew 1998).

It is now acknowledged that current evidence does not provide justification for requiring that all women give birth in hospital (Olsen & Jewell 2006) and that women should be offered an explicit choice when they become pregnant of where they want to have their baby (DH 2007a). A comprehensive literature review of home birth research, which included 26 studies from many parts of the developed world, concluded that ‘studies demonstrate remarkably consistency in the generally favourable results of maternal and neonatal outcomes, both over time and among diverse population groups’ (Fullerton & Young 2007:323). The outcomes were also favourable when viewed in comparison to various reference groups (birth-centre births, planned hospital births).

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated clear benefit in a number of associated elements of the home birth ‘package of care’, including continuity of care during labour and birth (Hodnett et al 2008) and midwife-led care (Hatem et al 2008), both of which are probably universal aspects of home birth provision.

Though official UK government policy up to the present is to offer women a choice about place of birth, the UK home birth rate remains just above 2%, compared with 25% in the early 1960s (Chamberlain et al 1997). There are anecdotal stories of women either being discouraged from choosing the home birth option or being told that staff shortages may impact on the availability of midwives.

One practical measure to reduce the bias to hospital birth may be to keep the option for home birth open until labour begins. Requiring a firm decision in early pregnancy regarding home birth may be problematic. Some women:

Birth centres or midwifery-led units

Free-standing birth centres as an option for women are especially relevant now (see Chs 32 & 34). Maternity services across the UK are merging, driven by the growth of neonatal tertiary referral centres and by rationalizing of management and clinical structures of individual hospitals that are no longer seen as cost-effective if they remain separate. These pressures are leading to stakeholders choosing to combine birth facilities on one site with neonatal services or retain present infrastructures and open midwifery-led units or birthing units (DH 2007b). The current trend appears to favour the first option, potentially resulting in further centralization of birth, in some areas up to 10,000 births per year in a single hospital, mirroring the controversial process in the 1980s, during which many small hospitals and isolated GP units closed, since lamented by midwives and user lobby groups.

Research and evaluation is needed to establish whether expansion is appropriate, as currently, service providers and clinicians are drawing from a pool of methodologically flawed papers. There are currently no RCTs and a paucity of good-quality research on free-standing birth centres or midwifery-led units. A structured review found these environments lowered childbirth interventions but methodological weaknesses in all studies made conclusions tentative (Walsh & Downe 2004), findings echoed by Stewart et al’s (2005) commissioned review. This model, endorsed by the Department of Health in England, reflects policy thinking that free-standing birth centres would be unlikely to have worse outcomes than home birth (DH 2007a).

Evaluations of integrated birth centres or alongside midwifery-led units have shown no statistical difference in perinatal mortality, suggesting encouraging results for the reduction in some labour interventions (Hodnett et al 2010). Debate continues regarding the noted non-significant trend in some of the studies of higher perinatal mortality for first-time mothers (Fahy 2005, Tracey et al 2007). This is unlikely to be resolved until contextual studies exploring the interface at transfer or impact of contrasting philosophies is examined in depth.

Reflective activity 36.2

During your course/practice, search out opportunities to see birth in environments alternative to hospital, such as in women’s homes, birth centres or in midwifery-led units.

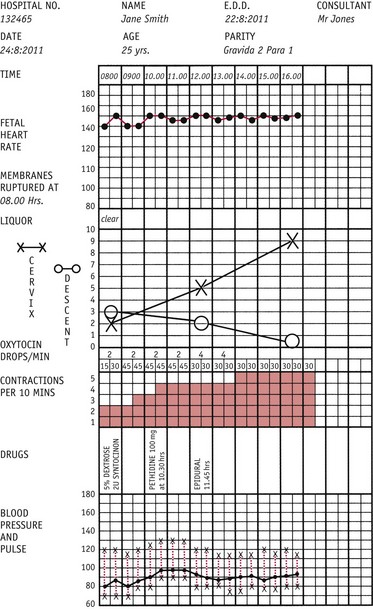

Qualitative literature on home birth and free-standing birth centres highlights two other aspects of care: how temporality is enacted and how smallness of scale impacts on the ethos and ambience of care. The regulatory effect of clock time is less evident both at home and in birth centres. Labour rhythms rather than labour progress tend to be emphasized by staff and there is usually greater flexibility with the application of the labour record, the partogram (Fig. 36.5). Part of the reason for this lies in the absence of an organizational imperative to ‘get women through the system’ (Walsh 2006a). Small numbers of women birthing mean less stress on organizational processes and a more relaxed ambience in the setting. This appears to suit women and staff well, suggesting attunement to labour physiology, inherently manifesting as biological rhythms based on hormonal pulses of activity, rather than regular clock time rhythms (Adam 1995). This increases the perception of clinical freedom, satisfaction and feeling of belonging for midwives (Walsh 2006b).

Significant research undertaken into different organizational models of midwifery care including teams, caseloads and midwifery group practices has been premised on the principle that women benefit from establishing an ongoing relationship with their carers rather than being cared for by strangers within a fragmented model. Common sense may suggest that journeying through such significant rites of passage in the experience of childbirth is best done in the company of known carers. Even without the studies, it could be argued that indigenous birth practices have much to inform maternity care in the west. For thousands of years, traditional birth attendants working with local women have harnessed the power of known birth companions in facilitating birth for the uninitiated woman. Western-style birth lost this crucial dimension when birth was hospitalized and supported by professionals who were usually unknown to labouring women. After the advent of doulas in US hospitals in the late 1970s, recognition was given to this fundamental aspect of labour care.

Doula studies examined the value of being supported throughout the entire labour and this aspect of care has now been extensively researched. A systematic review of nine RCTs (Hodnett et al 2007) concluded that continuous support during labour:

A review of eight studies of labour support provided by five different categories of persons concluded that care by known, untrained laywomen, starting in early labour, was most effective (Rosen 2004). A study echoing childbirth physiology found that oxytocin was released in women exposed to stress and this triggered ‘tending’ and ‘befriending’ behaviours rather than the classical (male) response of ‘fight and flight’. In a further mirroring of the hormonal cascade of labour, endogenous opiates, also released during the experience of stress, augment these effects (Taylor et al 2000).

The number of carers a woman has during her period of continuous support may also be relevant to outcome, as caesarean section rates appear to increase in direct line with increasing number of carers. Keeping the number of changes of labour support persons to a minimum has been recommended (Gagnon et al 2007).

Midwives have argued for decades to provide continuous support in labour so that they can genuinely be ‘with woman’. It is likely that this organizational aspect alone would increase normal birth rates substantially. Yet achieving this goal remains an objective rather than an imperative for most maternity services.

Continuity has been the subject of research and debate in midwifery for two decades. Examination of wider health literature reveals that continuity has been of interest for many other areas, summarized by Haggerty et al (2003) as being centred on:

All three contribute to a better patient experience and, arguably, better care. Midwifery care has focused more on relational continuity, possibly believing that the other two will follow, though this may not be the case. A case can be made for this focus because of the unique features of the midwife/woman relationship: its biologically determined longevity, its journey through a major rites of passage experience, and the intimate nature of its focus.

There are many organizational variants of continuity of care in midwifery services, including: named midwife, teams, caseloads, group practices. Research has suggested:

In relation to clinical outcomes and satisfaction with care, team and continuity variants generally reduce interventions, including epidural, induction of labour, episiotomy and neonatal resuscitation rates, and improve satisfaction.

Onset of labour

Physiological changes occuring in late pregnancy are described in Chapter 35 and lead to signs heralding the onset of labour. Some women will follow a particular physiological pattern, but allowance should be made for individual variations, which may be associated with differences in pain perception and response, parity, and expectations of labour. These factors must be considered by the midwife in assisting the woman to recognize when she is in labour.

Uterine contractions

Women become aware of the painless, irregular, Braxton Hicks contractions of pregnancy which increase as pregnancy advances. In labour these become regular and painful. Initially the woman may experience minimal discomfort and complain of sacral and/or lower abdominal pain, not necessarily immediately associated with labour. Such discomfort may later be noted to coincide with tightening or tension of the abdomen, occurring at regular intervals of 20–30 minutes and lasting 20–30 seconds. These uterine contractions can be paplpated by the midwife on abdominal palpation. As labour progresses, contractions become longer, stronger and more frequent, resulting in progressive effacement and dilatation of the cervix.

Show

This mucoid, often blood-stained, discharge is passed per vaginam, representing the passage of the operculum which previously occupied the cervical canal. This is indicative of a degree of cervical activity – that is, softening and stretching of tissues, causing separation of the membranes from the decidua around the opening of the internal os. The show is often the first sign that labour is imminent or has started.

Rupture of the membranes

Rupture of the membranes can occur before labour or at any time during labour (see Ch. 35). Although significant, it is not a true sign of labour unless accompanied by dilatation of the cervix. An estimated 6–19% of women at term will experience spontaneous rupture of the membranes before labour starts (Tan & Hannah 2002) and in 85% of women the membranes rupture spontaneously at a cervical dilatation of 9 cm or more (Schwarcz et al 1977). The amount of amniotic fluid lost when the membranes rupture depends largely on how effectively the fetal presentation assists in the formation of the forewaters. In the presence of a normal amount of amniotic fluid, if the head is not engaged in the pelvis and the presenting part is not well applied to the os uteri, rupture of the membranes is easily recognized by a significant loss of fluid. If the presenting part is engaged and well applied, rupture of the forewaters may result in minimal fluid loss. This is usually followed by further seepage of amniotic fluid, which may be mistaken for urinary incontinence (not uncommon in late pregnancy). Usually the woman’s history or evidence of amniotic fluid confirms the rupture of the membranes.

Contact with the midwife

Changing patterns of care reflect recent research highlighting the importance of consistent advice and continuity of care for this early phase of labour (Walsh 2007b). The woman should therefore be advised to contact the midwife when regular contractions are recognized, the membranes rupture, or if she is concerned for any reason.

Clear and written instructions, given well in advance of the expected date of birth, including relevant telephone numbers of the community or team midwives and their location, are necessary and useful for anxious partners/birth supporters.

If the woman does not know the midwife, the midwife must be aware of the sensitivity of the first meeting and the importance of the initial interaction with the woman, which forms the basis for their future relationship. Women experience a variety of conflicting emotions and it is important that at the initial meeting, the midwife makes a rapid assessment of the woman and context in order to prioritize her care.

Information should be calmly and sensitively sought, allowing sufficient time for the woman to express her feelings and identify needs. In particular, a woman’s story of how labour started should be validated, not dismissed as not fitting with what the textbooks say (Gross et al 2003). The midwife can achieve a relaxed, confident and reassuring approach, while acquiring the necessary information and enabling the woman’s verbal contribution to be valued, fostering the desired supportive partnership in care.

Prior to examining the woman, the midwife should review the woman’s notes and ensure that all required information is present. The birth plan should indicate the special needs and wishes of the woman and her partner and can assist in providing continuity of care and may provide reassurance to the woman that her particular needs and wishes are recorded for staff caring for her to see. Such plans may also be instrumental in enabling the woman to retain control of labour events and can provide the midwife with a valuable opportunity for health education in relation to birth.

Observations

General examination

The midwife assesses the woman’s appearance and demeanour, looking for features of general health and wellbeing. Observations of temperature, pulse, blood pressure and urinalysis are undertaken, providing a baseline for the labour. Recommendations regarding the frequency of recording the vital signs in labour are based on tradition rather than evidence. Commonly, the temperature and blood pressure are recorded 4-hourly with pulse hourly (NICE 2007).

Abdominal examination

A detailed abdominal examination is carried out, between contractions, to determine the lie, presentation, position and level of engagement of the presenting part. This must be a gentle process, avoiding pain or discomfort and involving the couple as much as possible. The lie should be longitudinal. It is also important to determine the presentation and whether the presenting part is engaged, or will engage, in the pelvis. Auscultation of the fetal heart completes the abdominal examination; it should be strong and regular with a rate of between 110 and 160 beats per minute.

Vaginal examination

This procedure is one of the options to help confirm the onset of labour. However, it is invasive and often very uncomfortable for the woman and also poses a potential infection risk. Women may request it in seeking reassurance about the status of labour.

Records

When labour is established, all observations, examinations and any drug treatment are recorded on the partogram, enabling observations to be detailed on one sheet (see Fig. 36.5). The midwife’s record constitutes a legal document, and throughout labour, accurate, concise and comprehensive records must be maintained in accordance with the midwives’ rules and record-keeping guidance (NMC 2004, 2009). Notations must be made at the time of the event, or as near as possible, and authenticated with the midwife’s full, legible signature and status.

Contemporaneous records also facilitate continuity of care in the event that care has to be transferred to another member of the team.

General midwifery care in labour

Assessment of progress

Labour progression has been the focus of extensive research over the past 40 years, though generally suffers from contextual narrowness, having been exclusively carried out in large maternity hospitals. This limits the ability to premise writing on conventional evidence sources and undermines attempts to explain the rich variety of personal anecdote around individual women’s labours. Research into out-of-hospital birth settings is urgently needed to explore and explain labour patterns.

Origins of the progress paradigm

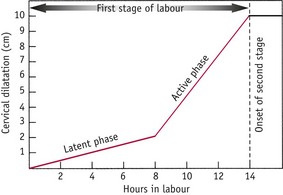

Friedman’s seminal work in measuring and recording cervical dilatation over time with a cohort of women in the mid-1950s influenced understanding of average lengths of labour for primigravid and multigravid women. The resulting sigmoid-shaped Friedman curve, representing early, middle and later phases of the first stage of labour, was incorporated into obstetric and midwifery textbooks for 50 years (Friedman 1954) (Fig. 36.6).

In the early 1970s, while working in remote area of Rhodesia, concerned about the disastrous consequences of obstructed labours, Philpott & Castle (1972) added the partogram to labour records and amplified the cervicograph to give guidance regarding slow labours, with three action lines used in the active phase of the first stage of labour:

Studd (1973) measured cohorts of women admitted to UK hospitals at differing stages of labour, plotting cervical dilatation over time, raising the possibility that British women might labour at different rates to African or North American women.

Organizational factors

This clinical imperative that long labours could indicate pathology may not have gained credence without the changes in organizational structures in how maternity care was delivered, in particular the centralizing movement of the second half of the 20th century. With more women giving birth in larger hospitals, organizational pressure increased towards processing women through delivery suites and postnatal wards. Martin (1987) railed against assembly-line childbirth in the 1980s, and Perkin’s (2004) comprehensive and considered critique of US maternity care policy, likening the Henry Ford car assembly line to the organization of maternity hospital activity, highlighted the explicit adoption of an essentially business/industrial model by maternity hospitals.

A study of childbirth at a free-standing birth centre (FSBC) in the UK (Walsh 2006a) highlighted temporal differences as being the most striking factor differentiating the FSBC from maternity hospitals. Women’s labours were not on a time line and there was no pressure to ‘free up’ rooms for new occupants. The corollary of hospitals with time restrictions on labour length is that more women can labour and birth within their space. It comes as little surprise to find that the hospitals still practising active management of labour are among the largest in Europe, with over 8000 births per year (Murphy-Lawless 1998). Midwives’ anecdotes and ethnographic research point to the pressures that exist in big units to ‘get through the work’ (Hunt & Symonds 1995).

A backlash against the clinical imperative of labour progress began to appear in the late 1990s when Albers’ research (1999) concluded that nulliparous women’s labours were longer than suggested by Friedman. In a low-risk population of women cared for by midwives in nine different centres in the USA, some active phases of labour were twice the length of Friedman’s cohort (17.5 hours v 8.5 hours for nulliparas, and 13.8 hours v 7 hours for multiparas) without any consequent morbidity. A later study found an average length of labour similar to that of Friedman but with a wider range of ‘normal’ (Cesario 2004). Primiparous women remained in the first stage for up to 26 hours, and multiparous women for 23 hours, without adverse effects. A recent RCT showed that if prescriptive action lines that limit labour length are used with primigravid women, then over 50% will require intervention, with the authors calling for a review of labour length orthodoxies (Lavender et al 2006).

One study examined patterns of cervical dilatation in 1329 nulliparous women, finding slower dilatation rates in the active phase, especially before 7 cm, where the slowest group were all below Friedman’s 1 cm/hour threshold. Conclusions suggested that current diagnostic criteria for protracted or arrested labour may be too stringent, citing important contextual differences in current practice to Friedman’s day (Zhang et al 2002). Improvement in the general health of the current generation of women compared with 50 years ago probably makes them less vulnerable to the effects of long labours.

These papers suggest more physiological variation between women than previously thought. Midwives have always known that many women do not fit the average of a 1 cm/hour dilatation rate and, more fundamentally, may not physiologically mimic the parameters of the ‘average’ cervix. Their cervix may be fully dilated at 9 or 11 cm. Given the infinite variety in women’s physical appearance and psychosocial characteristics, it seems reasonable to expect subtle differences in their birth physiology.

Better understanding of the hormones regulating labour contributes to this more complex picture of physiological variation. Odent (2001) and Buckley (2004) illustrated that the ‘hormonal cocktail’ influencing these processes is appropriately called the ‘dance of labour’, the hormones’ delicate interactions mediated by environmental and relational factors resembling the rhythm, beauty and harmony of skilled dancers.

Rhythms in early labour

The division of the first stage of labour into latent and active is clinician-based and not necessarily resonant with the lived experience of labour, especially for women with a long latent phase. Traditionally, the latent phase of labour has been understood to be of varying length, culminating in a transition to the active phase at around 4 cm dilatation of the cervix (NICE 2007). Gross et al (2003) increased understanding of the phenomenon of early labour by revealing how eclectically it presents in different women and how they vary in their self-diagnosis: 60% of woman experienced contractions as the starting point of their labours and the remainder described a variety of other symptoms. Gross suggests the direction of questioning be changed from eliciting the pattern of contractions to simply enquiring ‘How did you recognize the start of labour?’.

The midwifery diagnosis of labour in hospital is not simply a unilateral clinical judgement but a complex blend of balancing the totality of the woman’s situation with institutional constraints including workloads, guidelines, continuity concerns, justifying decisions to senior staff and risk management (Burvill 2002, Cheyne et al 2006). This can be contrasted with care at a home birth or in a FSBC, where the organizational and clinical parameters are secondary to women’s lived experience and care is driven by the latter (Walsh 2006a).

Twenty-five years ago, Flint (1986) counselled that early labour was best experienced at home with access to a midwife, and this remains the ideal for low-risk women. Maternity services have realized that the worst place may be on a delivery suite, because, as research shows, this can result in more labour interventions (Hemminki & Simukka 1986, Rahnama et al 2006).

Recent studies demonstrate the value of triage facilities or early labour assessment centres if home assessment in early labour is not an option, as this results in fewer labour interventions (Lauzon & Hodnett 2004). The value of attending an FSBC (Jackson et al 2003) and seeing a midwife rather than an obstetrician (Turnbull et al 1996) have been suggested. Individualizing care, and ongoing informational and relational continuity are all important elements of best practice for the latent phase of labour.

Rhythms in mid labour

Midwives’ understanding of the active phase of the first stage of labour has been the main focus of partogram recordings over the past 50 years. Having discussed the relaxation in timelines around this issue in recent years, the decoupling of the phenomenon of labour slowing or stopping, from the presumption that this represents pathology, can be explored. A retrospective examination of thousands of records of home birth women discovered that some had periods when the cervix stopped dilating temporarily in active labour (Davis et al 2002). This was not interpreted as pathology by birth attendants, and after variable periods of time, cervical progression began again. Apart from strong anecdotal evidence that some women experience a latent period in advanced labour, this was the first to record data on labour ‘plateaus’ (see Fig. 36.7).

Gaskin’s (2003) description of ‘pasmo’ indicated that physiological delays were known about in the 19th century. Accepting the individuality of the labour experience for different women, the subtlety of hormonal interactions, and the mediating effects of environment and companions, it is entirely feasible that labour could be understood as a ‘unique normality’, varying from woman to woman (Downe & McCourt 2008). Midwifery skill lies in facilitating this individual expression.

Recent research into the use of differing action lines (2 hours and 4 hours behind the 1 cm/hour line) in the active phase of labour indicates that allowing for a slower rate of cervical dilatation does not result in more caesarean sections and, importantly, women are just as satisfied with longer labours (Lavender et al 2006). A cervical dilatation rate of 0.5 cm/hour in nulliparous women is now recommended (Enkin et al 2000).

Vaginal examinations

The ubiquity of vaginal examination as a practice in labour, inextricably linked to the progress paradigm, means that the vaginal examination remains the most common procedure on labour wards. Appraisal of this common childbirth intervention is required to examine whether widespread use is justifiable. Devane’s (1996) systematic literature review failed to identify the research basis for this procedure, which reveals the power of the labour progress paradigm, effectively driving adoption of the procedure on the basis of custom and practice. The literature around sexual abuse (Robohm & Buttenheim 1996) and post-traumatic stress disorder (Menage 1996) indicates that women who have experienced these find vaginal examinations very problematic. A study by Bergstrom et al (1992), based on videotaped vaginal examinations in US labour wards, revealed the ritual that has evolved around the practice in order to legitimize such an intrusion into a person’s private space, showing the surgical construction of a practice undertaken by strangers, that would be totally unacceptable in any other circumstance except in an intimate sexual context between consenting adults. The adoption of a passive patient role and the marked power differential between the patient and the clinician were other taken-for-granted behaviours. In a UK-based study, similar conclusions were postulated (Stewart 2005).

Two important questions need asking before any vaginal examination is carried out (Warren 1999):

Finally, when examination is clinically justifiable, can the findings be accepted with confidence? The poor inter-observer reliability of the procedure (Clement 1994), illustrated by ‘guesstimate’ rather than ‘estimate’ scenarios of some clinical practice, may be assisted by practitioners ensuring that they undertake the examination systematically, and seek a ‘second opinion’ should the findings be unclear.

It is imperative that midwives approach vaginal examinations guided by negotiated and explicit consent, clear clinical justification and with sensitivity for the discomfort, embarrassment and pain that may be caused.

Indications for vaginal examination

Method

The woman is made comfortable in a semi-recumbent or lateral position with legs separated and as relaxed as possible. She can be encouraged to practice relaxation exercises. Appropriate cleansing is carried out, then the examining fingers (index and forefinger) are generously lubricated and gently inserted into the vagina.

During the examination, the midwife should note any abnormalities or deviations from normal, such as vulval varicosities, lesions (such as warts or blisters), vaginal discharge/loss, oedema and any previous scarring. She should also note the tone of the vaginal muscles and pelvic floor, and other characteristics, such as vaginal dryness or excess heat which might indicate pyrexia.

Cervix

The cervix is assessed for consistency, effacement and dilatation (as discussed previously and in Chapter 35).

Consistency

The cervix is usually soft and pliable to the examining fingers. It may feel thick and is often described as having a consistency comparable to that of the lips.

Effacement and dilatation

The cervical canal, which usually projects into the vagina, becomes shorter, until no protrusion can be felt. This shortening, often referred to as the ‘taking up’ of the cervix, results from the dilatation of the internal cervical os and the gradual opening out of the cervical canal.

During and following effacement, the cervical consistency alters and it becomes progressively thinner. Complete effacement may be present in primigravidae prior to the onset of labour and prior to dilatation. In the multiparous woman, although a degree of effacement may be present prior to labour, completion of the process occurs simultaneously with cervical dilatation as labour advances.

A soft, stretchy cervix, closely in contact with the presenting part, indicates potential for normal cervical dilatation. A tight, unyielding cervix or one loosely in contact with the presenting part is less favourable and may be associated with long labour.

Membranes

In early labour the membranes can be difficult to feel as they are usually closely applied to the head. During a contraction the increase in pressure may cause the bag of forewaters to become tense and bulge through the os uteri. The membranes may be inadvertently ruptured if pressure is applied at this time. If the head is poorly applied to the cervix, the bag of forewaters may bulge unduly early in the first stage and early rupture of membranes is likely to occur. This tends to occur with an occipitoposterior position.

Presentation

The presentation is normally the smooth, round, hard vault of the head. Sutures and fontanelles can be felt with increasing ease as the os uteri dilates, thereby enabling confirmation of the presentation and determination of the position and attitude of the head. The degree of moulding of the fetal head can also be assessed. As labour continues, particularly if the membranes are ruptured, subsequent formation of a caput succedaneum may make recognition of sutures and fontanelles difficult and sometimes impossible. Rarely, a prolapsed cord may be felt as a soft loop lying in front of or alongside the fetal head. If the fetus is still alive, the cord will be felt to pulsate.

Position

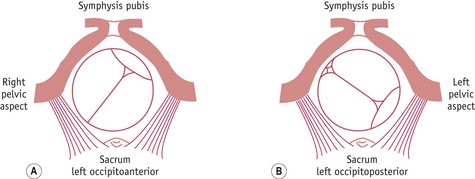

This can be determined by identification of the fontanelles and the sutures (Figs 36.8 and 36.9). An occipitoanterior position is identified by feeling the posterior fontanelle towards the anterior part of the pelvis. In an occipitoposterior position, the anterior fontanelle will be felt anteriorly. The fontanelles are identified by the number of sutures which meet (see Ch. 30). See Table 36.3 and website.

Figure 36.8 Identifying the position of the fetus. A. Left occipitoanterior: the sagittal suture is in the right oblique diameter of the pelvis. B. Left occipitoposterior: the sagittal suture is in the left oblique diameter of the pelvis.

Table 36.3 Assessing the position of the fetus

| Position of sagittal suture | Position of fontanelle | Position of fetus |

|---|---|---|

| Right oblique | Posterior fontanelle anteriorly to the left | LOA |

| Anterior fontanelle anteriorly to the left | ROP | |

| Left oblique | Posterior fontanelle anteriorly to the right | ROA |

| Anterior fontanelle anteriorly to the right | LOP | |

| Transverse diameter of the pelvis | Posterior fontanelle to the left | LOL |

| Posterior fontanelle to the right | ROL | |

| Anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis | Posterior fontanelle felt anteriorly | OA |

| Anterior fontanelle felt anteriorly | OP |

LOA, left occipitoanterior; LOL, left occipitolateral; LOP, left occipitoposterior; OA, occipitoanterior; OP, occipitoposterior; ROA, right occipitoanterior; ROP, right occipitoposterior; ROL, right occipitolateral

Occasionally, the sagittal suture is found in the transverse diameter of the pelvis between the ischial tuberosities. It is then necessary to identify one or both fontanelles to determine the position. It may also be possible to feel an ear under the symphysis pubis and this may give an indication of the position of the fetus. Prior to delivery, when the fetal head has rotated on the pelvic floor, the sagittal suture should be in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis.

A summary of how to assess the position of the fetus is given in Table 36.3.

Flexion and station

The fetal head may or may not be flexed at the onset of labour. In the presence of efficient uterine action and as a result of fetal axis pressure, the fetal head usually flexes, further facilitating a well-fitting presenting part. Unless the pelvis is particularly roomy or the fetal head small, deflexion of the head, and palpation of the posterior and anterior fontanelles, may be indicative of malposition of the fetal head, poor cervical stimulation and prolongation of labour.

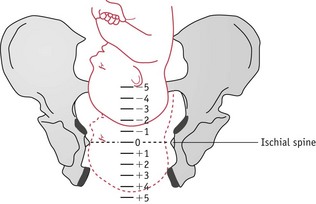

The station or level of the presenting part refers to the relationship of the presenting part to the ischial spines. The maternal ischial spines are palpable as slight protuberances covered by tissue on either side of the bony pelvis. Descent in relation to the maternal ischial spines should be progressive and is expressed in centimetres as indicated in Figure 36.10.

Figure 36.10 Stations of the head in relation to the pelvis. Descent in relation to the maternal ischial spines is expressed in centimetres.

The examination is completed by applying a vulval pad, changing any soiled linen and making the woman comfortable. The fetal heart is auscultated. All findings are recorded and the midwife analyses the findings to establish a total picture on which to make an accurate assessment of the progress of labour and to forecast how the labour is likely to advance. The midwife is able to relate to the woman and her partner the progress to date, and review with them the original birth plan for any adjustments which the woman and the midwife feel are necessary.

Alternative skills for ‘sussing out’ labour

There is a dearth of any research examining alternatives to vaginal examinations for labour care, given the rich anecdotes that surround this area. Midwives have always taken into account the character of contractions, a woman’s response to them and the findings from abdominal palpation. Stuart (2000) is possibly unique in relying on abdominal palpation instead of vaginal examination to ascertain progress, and most midwives weigh the results of vaginal examination above contractions and behaviour. It is the practices that are substitutional for vaginal examinations that are the most interesting. Hobbs (1998) advocated the ‘purple line’ method – observing a line that runs from the distal margin of the anus up between the buttocks, said to indicate full dilatation when it reaches the natal cleft. Byrne & Edmonds (1990) reported that 89% of women developed the line. In a comprehensive manual of care during normal birth, Frye (2004) identified monitoring temperature change in the lower leg. As labour progresses, so a coldness on touch is noted to move from the ankle up the leg to the knee. Another marker may be the forehead of a woman. Possibly originating from traditional birth attendant practices in Peru, this involves feeling for the appearance of a ridge running from between the eyes up to the hairline as labour progresses.

Other wisdom comes from intuitive perceptions that many midwives may recognize but find hard to articulate, and even harder to write down, as illustrated by the story to be found on the website.

The transitional phase between the first and second stages has been studied by Baker & Kenner (1993), who noted the common vocalizations that mark it. These are just a few examples of anecdotes that abound in this area. It is an area ripe for observational research and for articles mapping the richness of midwives’ experience.

Finally, there is the domain of emotional nuance reading, which may impact hugely on how labour unfolds (Kennedy et al 2004). One such episode occurred in the birth centre study by Walsh (2006b), when a teenage girl arrived in early labour, very distressed. The midwife asked her mother and sister to leave the room and gently enquired as to how she was. She burst into tears and over the next 2 hours the midwife held her in an embrace on a mattress on the floor as the girl sobbed and sobbed. Then she said she was ready and went on to have a normal, rather peaceful birth. In other settings, the girl may have been offered an epidural, but this was emotional rather than pain distress. The skill of the midwife was in her intuitive emotional nuance reading of that and how to bring comfort and support.

‘Being with’, not ‘doing to’, labouring women

The quest to dismantle assembly-line birth, removing women from the intrapartum timeline and rehabilitating belief in ‘unique normality’ of labour for individual women, challenges a radical rethink of the focus and orientation to normal labour care. Hints of a different way of midwives situating themselves with women are in the writings of midwives and they speak in paradox and metaphor. Leap (2000) tells of ‘the less we do, the more we give’, and Kennedy et al (2004) of ‘doing nothing’ in their insightful study of expert US midwives. Fahy (1998) conceptualizes the work of the midwife as ‘being with’ women, not ‘doing to’ them, and Anderson (2004) quips that good labour care requires the midwife ‘to drink tea intelligently’. These writers are alluding not to a temporally regulated activity marked by task completions but to a disposition towards compassionate companionship with women that is a ‘masterly inactivity’ (RCM 2010). As a birth centre midwife offered during an interview: ‘It’s about being comfortable when there is nothing to do.’

Loss per vaginam and rupture of the membranes

The time at which the membranes rupture should be recorded, together with the appearance of the liquor. A minor amount of blood-stained loss is consistent with a show or detachment of the membranes occurring with increasing cervical dilatation. Copious mucoid blood-stained loss may herald full cervical dilatation. A greenish colour is indicative of meconium staining, sometimes associated with fetal distress. Frank bleeding per vaginam is abnormal; if this occurs, the midwife must consult with the obstetrician, who will ascertain the source – whether maternal or fetal – and determine the appropriate action. Measurement of loss and monitoring of the woman’s condition is vital.

Bladder care

The woman is encouraged to empty her bladder every 2 hours. A full bladder is uncomfortable and may delay the progress of labour by inhibiting descent of the fetal head if it is above the ischial spines. This will reflexly inhibit efficient uterine contractions and cervical dilatation. Pressure on the distended bladder by the fetal head may give rise to oedema and bruising, leading to possible difficulties in micturition in the early days of the puerperium.

Mobility and ambulation

Seven RCTs undertaken to evaluate ambulation agreed that there are no negative effects associated with mobility though there were varying conclusions as to benefit. Two studies (Flynn et al 1978, Read et al 1981) emphasized the following advantages:

MacLennan et al’s (1994) meta-analysis of their own trial with five others confirmed the finding of reduced analgesia requirements and noted that 46% of women in their study who declined entry to the trial did so because they did not want to lose the choice of ambulation. The most recent and largest trial (Bloom et al 1998) found that 99% of ambulant women would choose this mobility again. No other differences were noted compared with the recumbent group.

Movement appears to be a central characteristic of normal labour (Gould 2000). In an overview of trials of ambulation, Smith et al (1991) found that when given the choice, women changed position an average of seven to eight times in the course of their labours.

Upright posture

Positive effects of gravity and lessened risk of aortocaval compression (and therefore improved fetal acid–base outcomes) were described by Bonica (1967) and Humphrey et al (1973). Mendez-Bauer et al (1975) demonstrated stronger, efficient uterine contractions. Radiological evidence from the 1950s and 1960s showed larger anteroposterior and transverse diameters of the pelvic outlet in squatting and kneeling positions (Russell 1969). Gupta & Nikodem’s (2008) review of position in the second stage of labour seems to support these earlier findings. A Cochrane review of 21 studies, with a total of 3706 women, found that mobility and upright positions in the first stage of labour reduced the length of labour by about an hour (Lawrence et al 2009).

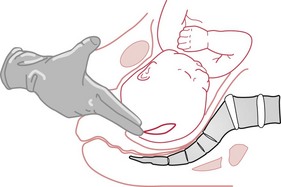

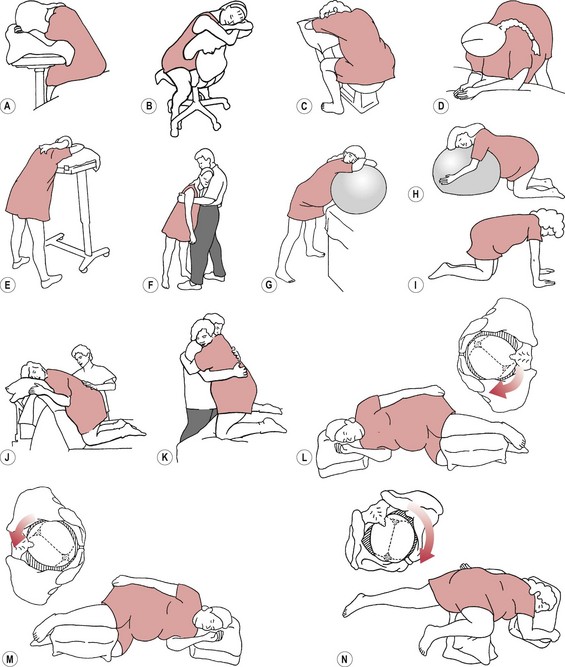

Flint (1986) discussed the idea of midwives ‘fitting around women’, emphasizing that nearly all common procedures, such as fetal monitoring and vaginal examinations, could be done without asking the woman to get on the bed. Props, such as beanbags and birth balls, can be used to facilitate positional and postural changes, and Robertson (1997) elaborates on these through Active Birth Workshops. Certainly, the mass trend towards lying down for childbirth, at least in western cultures, was never tested empirically and occurred largely to assist the birth practitioners to carry out technical interventions, such as forceps deliveries and administration of anaesthetics (Donnison 1988) (see Chapter 2). This will continue to be tacitly endorsed by midwives as long as the ‘bed birth myth’ of childbirth remains. Some independent birth centres have replaced conventional beds with sofa beds and it may be time for delivery suites across the country to follow suit. This simple, cosmetic alteration would be deeply symbolic and may have a significant impact on birth positions. Figure 36.11 illustrates a variety of positions for the first stage of labour.

Figure 36.11 A variety of positions for the first stage of labour. A. Sitting, leaning on a tray table. B. Straddling a chair. C. Straddling toilet, facing backwards. D. Standing, leaning on bed. E. Standing, leaning on a tray table. F. Standing, leaning forward on partner. G. Standing, leaning on ball. H. Kneeling with a ball. I. On hands and knees. J. Kneeling over bed back. K. Kneeling, partner support. L. Pure side-lying on the ‘correct’ side, with fetal back ‘toward the bed’. If the fetus is ROP, the woman lies on her right side. Gravity pulls fetal head and trunk towards ROL. M. Pure side-lying on the ‘wrong’ (left) side for an ROP fetus. Fetal back is ‘toward the ceiling’. Gravity pulls fetal occiput and trunk towards direct OP. N. Semi-prone on the ‘correct side’ – with fetal back ‘toward the ceiling’. If the fetus is ROP, the semi-prone woman lies on her left side. Gravity pulls fetal occiput and trunk towards ROL, then ROA.

(From Simkin & Ancheta [2000], with permission of Blackwell Science Ltd.)

Moving and handling

Moving and handling concerns, and worries about back injuries, may preclude some midwives from assisting women who opt for an upright birth posture. If this is a real issue for practitioners, it may also have implications for assisting at recumbent births as well, as these sometimes require awkward twisting and bending. Midwives are now usually trained in ‘good back care’ with mandatory moving and handling sessions run by hospitals. The application of these principles should not interfere with assisting women to birth in upright postures, as these postures probably also protect women’s joints and backs more than conventional bed birth.

Home birth practitioners are familiar with birth taking place in living rooms as well as bedrooms, and with the restlessness of labour, during which women move freely within the privacy of their chosen birthing space, and may choose the bed only as a prop. It is probably time to expunge the term ‘confinement’ from the vocabulary of childbirth once and for all, and ensure that the environment ‘belongs’ to the woman and her partner.

Prevention of infection

In labour, both mother and fetus are vulnerable to infection, particularly following membrane rupture. The possibility is increased when the immune response is undermined by suboptimal health – for example, anaemia, malnourishment, chronic illness – or when the woman is exhausted by a long and arduous labour. The hospital environment itself may increase the woman’s risk of infection as she is exposed to a variety of unfamiliar organisms and possible sources of infection.

The midwife must ensure, as far as possible, a safe environment for the woman and prevent infection and cross-infection. Such measures include good standards of hygiene and care, correct handwashing of the carers before and after attending the woman, frequent changing of vulval pads, and meticulous aseptic techniques when undertaking vaginal examination and other invasive procedures such as catheterization.

General measures, such as limiting the flow of traffic within the delivery area, scrupulous cleansing of communal equipment (for example, beds, baths, toilets and trolleys) and increasing staff awareness of the potential for, and prevention of, infection, must all be observed. A formal mechanism for infection control within hospitals must include maternity departments. One survey of surveillance of hospital-based obstetric and gynaecological infection showed a significant reduction in the incidence of infection when regular feedback to staff was implemented (Evaldon et al 1992).

Nutrition in labour

Controlling women’s behaviours and choices in labour has traditonally included restrictions on what they can eat and drink. This was driven by concerns about aspirating stomach contents (Mendelson’s sydrome) should general anaesthesia be required in an emergency. However, as regional anaesthesia has become common and anaesthetic techniques have improved, the incidence of aspiration has plummeted (Chang et al 2003). Apart from the medical risks, controlling what women eat and drink in normal labour is paternalistic and, arguably, an infringement of human rights. At home and birth centre births, the sensible approach of self-regulation has operated for decades. Women eat and drink when they feel hungry and thirsty, more commonly in early labour. Some women experience nausea as labour progresses and therefore forsake food, though they do usually continue to drink small amounts.

Odent (1998) and Anderson (1998) suggested that the smooth muscle structure of the uterus works much more efficiently than skeletal muscle, making comparatively small energy demands and utilizing fatty acids and ketones readily as an energy source. It is suggested that because the woman in physiological labour becomes withdrawn from higher cerebral activity, and as skeletal muscles are at rest, energy requirements are less than normal.

Tranmer et al (2005) tested the hypothesis that unrestricted eating and drinking during labour might reduce the incidence of labour dystocia. Though no effect was shown, it did highlight that when women self-regulate, many do choose to eat and drink, usually small amounts and often in the early stages of labour.

Imposed fasting in labour for all women is questionable in the light of evidence indicating that fasting in labour does not ensure an empty stomach or lower the acidity of stomach contents (Johnson et al 1989). Restrictions may lead to dehydration and ketosis, resulting in interventions, and this should be weighed against the alternative course of allowing women to eat and drink as desired (Johnson et al 1989).

Many maternity units require the administration of an acid inhibitor like ranitidine to increase the pH of the stomach contents. However, this is only appropriate in women of high risk status who might be more at risk of emergency procedures and should not be applied to women in normal labour.

Assessing the fetal condition

The midwife needs to understand the mechanisms that control fetal heart response in order to interpret the fetal response to labour. The cardioregulatory centre of the brain, situated in the medulla oblongata, is influenced by many factors. Baroreceptors situated in the arch of the aorta and carotid sinus sense alterations in blood pressure and transmit information to the cardioregulatory centre. Chemoreceptors situated in the carotid sinus and arch of the aorta will respond to changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide tensions. The cardioregulatory centre is controlled by the autonomic nervous system and, in response to varying physiological factors, either the sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous system will be stimulated. The sympathetic nervous system, via the sinoatrial node, causes an increase in heart rate, while the parasympathetic nervous system causes a rate reduction. The continuous interaction of these two systems results in minor fluctuations in the heart rate which is recognized as variability. Development of the sympathetic nervous system occurs early in fetal life, while the parasympathetic nervous response does not become pronounced until later in pregnancy. This accounts for the higher baseline rate of the fetal heart during early pregnancy and the lower rate at term.

Monitoring the fetal heart

The activity of the fetal heart may be assessed intermittently using the Pinard fetal stethoscope or a Sonicaid. This provides the midwife with sample information regarding the rate and rhythm of the fetal heart. At commencement of intermittent auscultation, it is important to distinguish the maternal pulse from the fetal heart, as the former can mimic a fetal heart and, therefore, can be falsely reassuring to the midwife. An understanding of the workings of the Sonicaid is useful, and reinforces the value of the use of the Pinard stethoscope at regular intervals even if the Sonicaid is used (Gibb & Arulkumaran 2007).

Intermittent auscultation of the fetal heart is usually undertaken every 15 minutes during the first stage of labour, though this is based on custom and practice, not research. In the second stage of labour, this increases to every 5 minutes. NICE (2007) recommends intermittent auscultation and abandonment of the ‘admission trace’ for women in normal labour.

Healthy fetal heart patterns

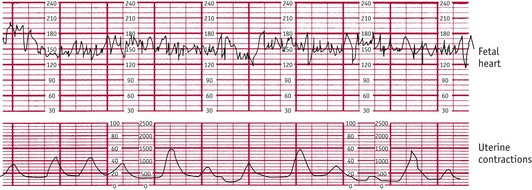

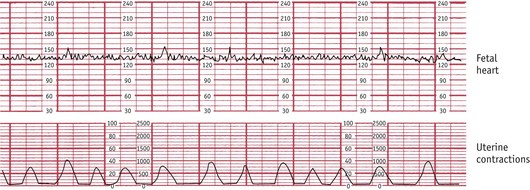

The normal fetal heart has a baseline rate of between 110 and 160 beats per minute (bpm). The baseline rate refers to the heart rate present between periods of acceleration and deceleration. Baseline variability refers to the variation in heart rate of 5–15 bpm, occuring over a time base of 10–20 seconds. Figure 36.12 demonstrates normal baseline variability. The presence of good variability is an important sign of fetal wellbeing (NICE 2007).

Figure 36.12 ECG trace showing baseline variability in fetal heart rate.

(Courtesy of Sonicaid, Abingdon, Oxon.)

Acceleration patterns of the fetal heart of 15 bpm from the baseline, as shown in Figure 36.13, are often associated with fetal activity and stimulation and are thought to be useful indicators of absence of fetal acidaemia in labour (Spencer 1993). They are not considered to be clinically significant if of short duration – that is, less than 15 seconds. When two are present within a 20-minute period, the trace is described as ‘reactive’ (Gibb 1988). This is considered to be a positive sign of fetal health, indicating good reflex responsiveness of the fetal circulation.