History and Physical Examination

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 Explain the role of the veterinary technician in obtaining the patient’s medical history.

2 List questions commonly used to obtain a patient’s medical history for small and large animals.

3 List the sections of information found in a medical history for small animal patients.

4 Describe the type of information contained in each section of the patient’s medical history for small animals.

5 List the sections of information found in a medical history for large animal patients.

6 Describe the type of information contained in each section of the patient’s medical history for large animals.

7 Describe the general procedures used to obtain a physical examination in dogs and cats.

8 Describe the general procedures used to obtain a physical examination in horses and cattle.

9 Discuss the methods for performing a comprehensive evaluation of each of the body systems.

10 List and describe unique procedures used in the examination of horses and cattle.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF SMALL ANIMALS

Obtaining a complete history is the first step toward creating a diagnostic and therapeutic plan for most veterinary patients. Pertinent historical information is an important part of a complete and accurate assessment of the patient. The veterinary technician should be sure to ask questions that clarify the nature of current and previous clinical problems and that confirm the accuracy of the information. This may require asking the same question more than once and repeating responses back to the owner asking, “Do I have this correct?” Despite its importance, obtaining a thorough history is often overlooked by both veterinarians and veterinary technicians.

Obtaining a thorough history in a clear and organized manner is the foundation of a comprehensive patient’s evaluation, but it can be challenging to do. For example, there are owners from whom it is difficult to extract information because they either say too little or talk incessantly about unrelated issues. In addition, the person presenting the patient to the practice may not be the patient’s owner and may not know the answers to the questions you are asking. Finally, certain problems or disease states may require specifically tailored questions. The goal of this discussion is to present an organized approach for obtaining a complete and accurate history for each and every patient. This method serves as a foundation upon which questions, based on the owner’s knowledge and the patient’s specific complaints and preexisting diseases, can be added.

THE ROLE OF THE VETERINARY TECHNICIAN

The veterinary technician who is capable of obtaining a complete and accurate history can play a critical role in a busy veterinary practice. Obtaining information from clients is often time consuming, and veterinary technicians who can do this well free veterinarians to complete other work. The information that is obtained, however, is only useful if it is complete and accurate. Acquiring inaccurate information could be worse than obtaining no historical information at all. Faulty information might result in unnecessary diagnostic tests, treatments, and lost client trust. To optimize the likelihood that the information obtained is complete and accurate, technicians must gain the trust of the client.

Developing Rapport With the Client: When obtaining a medical history, the first step is to introduce yourself to the client and explain what you are doing so the client feels comfortable and is willing to share information with you. Always be certain to know the client’s name and the pet’s name and sex to prevent embarrassing mistakes when referring to the client or patient. In situations where the pet has been taken away from the client before obtaining the history (e.g., taken to the treatment area for cardiovascular stabilization following trauma), it is essential that you reassure the owner about the pet’s status before asking questions. If the client is worried that his pet is in danger, he will not be able to focus on you and give you the information you need. Once you have established a rapport with the client, obtaining complete and accurate information will be easier. The next challenge is to ask questions in an effective manner.

Asking the Questions: The most important aspect of taking a history is to understand and respect the pet owner. Some owners have medical training and can be spoken to using medical jargon; however, the majority of owners do not understand medical terminology, and the veterinary technician must be careful to use simple language without belittling the client. For example, if the technician is doing a follow-up examination of a diabetic cat, whose owner is checking the urine daily for glucose, it would be inappropriate to ask, “Have you noted glucosuria since your previous visit?” It would be equally inappropriate to ask, “Is the little square pad on your dipstick changing color when you dip it in Fluffy’s pee pee?” Finding words that are appropriate for the client is important so that he feels neither confused nor insulted. Technicians are safest asking “Has the urine strip been positive for sugar since your previous visit?” It is important to strike an appropriate balance and tailor your questions to the individual client to avoid losing trust.

It is also important to ask open-ended questions, rather than leading questions. An open-ended question is one that requires the client to fill in the information themselves, whereas a leading question is one that potentially guides her to an answer. For example, if you are trying to determine whether a pet is polydipsic it is best to ask the open-ended question, “Have you noticed any changes in his water intake during this illness?” rather than “Has he been drinking more water than usual?” When leading questions are asked, clients sense which response the interviewer prefers and are likely to give it; pet owners are anxious to help resolve their animal’s problems. Needless to say, asking leading questions can generate inaccurate historical information.

When questioning clients, try to avoid being judgmental of their care and management of their pet because this may make them feel uncomfortable about giving truthful answers. The questions you ask should not show your biases or personal beliefs. For example, when questioning an owner about his dog that has acute vomiting and diarrhea, it would be unhelpful to ask, “You don’t feed her table scraps, do you?” Faced with that question, an owner is likely to say, “No, of course not,” even if she really does feed her pet table scraps. It would be better to ask, “What is her normal diet?” or “Did she eat anything outside of her normal diet recently?” or “What human food does she typically eat?” Making the client feel comfortable with their decisions will improve the chances that you receive accurate information.

Documenting the Information: Historical information is useless unless it is written carefully, neatly, and accurately in a structured medical record form. All veterinary hospitals should have a standardized history form as part of the medical record, which allows efficient recording of the information presented (see Figure 5-7, A in Chapter 5). This form should also provide prompts to remind you to obtain certain pieces of information. The information should be recorded in the medical record as it is obtained to prevent any subsequent misunderstanding. In addition, it should be written legibly or typed using appropriate medical terminology, and it should be clearly organized. Keep in mind that the medical record is a legal document, and, as such, should be written with the utmost care and precision. The medical history will provide a reference for the veterinary health care team as it implements and revises its diagnostic and treatment plans for the patient.

THE INFORMATION

The following sections provide a general listing of important information that should be obtained in most medical histories. Some additions or deletions may be appropriate in specific cases. This is meant to serve as a guideline to ensure that complete and accurate historical information is obtained in an efficient manner.

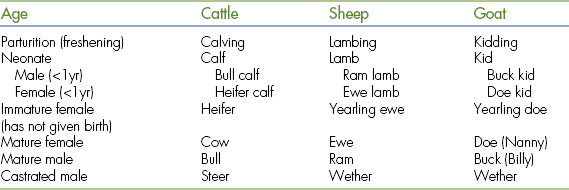

Signalment: Every patient record should contain the pet’s signalment, which includes age, breed (or dominant breed if mixed), sex, and reproductive status (spayed or neutered). It is important to confirm the signalment during the first meeting with the client because this information often provides important clues about the case. Certain diseases appear more commonly in animals of certain signalments. For example, congenital diseases are more likely to be diagnosed in very young patients than in very old patients.

General Management: The background information should begin with a discussion of how long the pet has been owned and where and when it was obtained. Any previous medical problems should be recorded. If it was obtained from a breeder, it may be useful to note whether the client still has contact with the breeder and if she knows of any diseases present in related dogs. When discussing the pet’s origins, ask if there has been any recent travel away from the pet’s normal living areas. This information is most important when there is a suspicion of a disease that is endemic to a region where the pet has visited within the past 6 months.

This is also a good time to find out where the pet is kept during the day and what its normal routine is. If it is kept indoors, is it in a crate or restricted to a certain part of the home? If it is kept outdoors, is it in a fenced yard or allowed to run free? You should always get a thorough diet history at this time. This should include the type of food eaten, the amount, and the frequency. It is also important to note if there have been any recent changes in the diet or if the animal was fed anything unusual (or if it got into something it should not have) just before the onset of illness.

Preventive Medicine: Complete information regarding vaccination history should be obtained if the pet is not a previous patient. Note which vaccines were given, when they were given, and the expiration date of the vaccine. This is the time to also ask about other preventative medications, such as heartworm and flea and tick prevention. Information regarding the consistency with which these medications are given is important as is whether they are given year round or only during warmer months. When discussing flea and tick medication, it is also a good idea to ask whether the owner has seen fleas or ticks on the pet.

Behavioral Information: Ascertain what the pet’s normal behavior is on a day-to-day basis and, more importantly, note any changes in the behavior relative to the illness. This is helpful in several ways. First, it lets you know if the pet is aggressive toward people or other animals, which may affect how you handle the animal when it comes time for a physical examination or hospitalization. Second, it allows you to determine if any behavior changes may explain the underlying illness, such as increased aggression, disorientation, unusual elimination habits, and so on.

Household Information: The health status of the other members of the patient’s household can be important in determining the cause of the pet’s illness, especially in cases of infectious disease. Determine to what extent the pet is exposed to other animals: what species, how many, and for what duration. You should also determine whether any of those animals are ill, regardless of whether the symptoms are similar to those of the presenting patient. Remember to ask questions about illnesses among the humans in the family. This is especially important in some cases of infectious dermatologic disease, such as sarcoptic mange, and may also provide information regarding the patient’s exposure to toxins, such as medication belonging to family members.

Allergy History: Before instituting any medical therapy, it is important to note any known allergies or other adverse reactions to medications or food that the pet may have experienced. Even if these reactions have not been confirmed to be related to the exposure in question, they are important to note. Avoidance of medications to which there is even a suspicion of an allergy is sensible. At this time, also inquire about prior blood product transfusions and reactions. You should ask whether the pet has ever received a blood product transfusion. If they have, attempt to determine what product, when it was administered, if there was any adverse reaction, and if the pet’s blood type is known. This information will help guide any subsequent blood product therapy.

Reproductive History: Although the current reproductive status of the patient will be noted in the signalment as discussed earlier, it is important to ask for historical information regarding the patient’s prior reproductive history. If an animal is neutered, it is important to note at what age the procedure was performed. This information may pertain to disease prevalence. For example, mammary tumors are much more common in female dogs after they have gone through a single heat than if they are spayed before their first heat. If an animal is not neutered, you should ask if it is currently being bred and if it has previously been bred. The timing of the most recent heat cycle should be noted for all intact female dogs because pyometra occurs most commonly 2 weeks to 2 months following a heat cycle.

Past Pertinent Medical History: Identify any prior medical problems that the pet has experienced. Recurrent bouts of similar problems may represent a serious chronic disease. Some previous historical problems may be of no significance to the current presentation. Those problems can be ignored. However, if a problem sounds like it may be relevant to the current complaint, you will have the opportunity to question the owner more thoroughly about it.

Presenting Complaint: The presenting or chief complaint is the most important information to be addressed in the medical history. Every patient will have a presenting complaint, and owners are often anxious to discuss this. During emergencies, it is important to quickly obtain information regarding the presenting complaint before obtaining any background information because time is of the essence in treating life-threatening problems. The presenting complaint can be obtained simply by asking, “What brings you to the practice today?” A patient may have more than one presenting complaint. In this case it is best to record and discuss each complaint separately. Do not assume that all of the symptoms can be tied to one medical disorder.

Last Normal: A good way to get a sense of the duration of a problem is to ask the client, “When would you say your pet was last normal?” This often helps the client recall a pleasant time when the pet was acting normally, which is easier than trying to remember how long the pet has been sick. The duration of each presenting complaint varies. Constructing a chronologic timeline is helpful to finding a diagnosis.

Progression: Once you have established a problem list, determine the order in which each problem appeared and how long each one lasted. Also ascertain how each problem has progressed. In other words, are the problems better, worse, or the same? This information may be helpful when constructing a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. A problem that is rapidly worsening may warrant a more aggressive course of therapy than a problem that is stable or improving.

Systems Review: The client should be asked a series of questions that reviews each of the pet’s basic body systems. Some of these questions may have already been answered when discussing the presenting complaint, in which case they should not be repeated. However, some of the questions may provide information that would otherwise be overlooked by the owner because they are so focused on the presenting complaint. All clients should be asked about the presence of coughing, sneezing, vomiting, diarrhea, polyuria, and polydipsia. Current appetite and energy level should be addressed. Any perceived weight loss or weight gain should be noted.

Medications: Every client must be asked what medications, if any, they are currently giving their pet. This information should be as complete as possible. The goal should be to find out the following: type, dose and frequency for each medication, the duration for which it has been given, the reason it is being given, and whether it has provided benefit to the pet. In situations where all of this information is not known by the owner, you should obtain as much of the information as possible. In addition to conventional medication, you must always ask about any vitamins or dietary supplements that are given to the pet. Ask specifically about the use of topical eye and ear preparations and of medicated shampoos; some owners do not think of these as medications. Finally, be sure to review any preventative medications that are being given, such as heartworm and flea and tick products.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A thorough physical examination is often the first and most important diagnostic test performed on a patient. Because we must rely on an owner’s interpretation of their pet’s illness and because the symptoms pets show are often vague, the physical examination may be more important than the medical history in determining the source of illness. The key to a good physical examination is to carefully complete all parts of the examination every time you perform it. You should perform all aspects of the physical examination in the same order in every patient. Developing this sort of routine will prevent you from forgetting to evaluate one area because you are overly focused on another. The routine you develop may need to vary slightly from patient to patient. You will find that certain areas of the examination will be covered more carefully in some patients than in others. For example, a complete neurologic examination may be unnecessary on a patient that is seen for coughing and is ambulating normally with no historical complaints about the nervous system. Similarly, in a patient that has hind limb paralysis, you may limit your respiratory examination to a brief auscultation and spend more time performing a complete neurologic examination, including reflex testing. The key is to perform some evaluation of every system during every examination. The guidelines in the following paragraphs provide one example of the method by which a physical examination could be performed, but you can develop your own routine as you become more experienced. As long as you follow the same routine every time you perform a physical examination, you can be sure that your examination will be thorough.

DOCUMENTING THE INFORMATION

As discussed for the medical history, the physical examination must be documented appropriately. All veterinary hospitals should have a standardized physical examination form as part of the medical record (see Figure 5-7, B in Chapter 5). This form should have areas for recording body weight, temperature, pulse rate, and respiratory rate. It should also provide prompts to remind you to examine each of the body systems discussed later and specified areas to record that information. As with any part of a medical record, the recorded information should be typed or legibly written, medical terminology should be used, and the content should always remain professional. Information should be documented in as much detail as possible so that the findings can be compared with those of future physical examinations.

SURROUNDINGS

Every physical examination should begin with a subjective assessment of the patient in its surroundings. Several pieces of useful information can be obtained just with a quick visual inspection of the animal from a distance as it behaves in the waiting room, examination room, or kennel. You can determine a general sense for the animal’s mentation. Is the patient bright, alert, and responsive? Is the patient quiet but alert and responsive? These states may suggest a less emergent condition. Is the patient dull, depressed, or even unresponsive? These states could indicate more serious disease or neurologic dysfunction. In addition to the mentation, you can visually inspect the animal as it rests for increases in respiratory rate or effort. While the animal walks, quickly look for evidence of lameness, ataxia, or visual deficits. You may be able to identify any asymmetry or swelling of the patient. This is a good time to evaluate the body condition of the patient and assign a body condition score. The list of things that you can identify with a careful visual inspection is extensive. All of this information is important to determine before moving forward with the remainder of your physical examination.

TEMPERATURE, PULSE, AND RESPIRATION

The measurement of body temperature, pulse rate, and respiratory rate will be a part of every physical examination. Even if the veterinary technician will not be performing a complete physical examination, he or she will often be asked to obtain this information before the veterinarian’s examination. For the veterinarian and veterinary technician, these values provide a quick reference to a substantial amount of information regarding the status of the patient. As mentioned previously, these values should be recorded in a dedicated area on the standard physical examination form.

The body temperature is optimally measured rectally using a rectal probe thermometer. Most rectal thermometers in current use report the temperature through a digital display window (Figure 8-1). These thermometers work quickly and are safe and accurate. Still available but less commonly used are the liquid-capillary thermometers, which rely on a column of liquid (usually alcohol or mercury) to rise inside the thermometer and be compared with a scale on the thermometer for temperature determination. Always use a protective cover with the thermometer to minimize disease transmission. Lubricating the probe will make insertion much easier. When using the liquid-capillary type of thermometer, remember to shake the thermometer with the insertion tip down so that the liquid level falls from where it was left following its most recent use. Forgetting this step could result in an inaccurate measurement. Whereas a rectal temperature measurement is optimal, an axillary or aural temperature measurement may be used in cases where the rectum or nearby anatomy is swollen or painful, such as severe colitis or a perineal hernia. These methods are less accurate than a rectal measurement and should only be used when necessary.

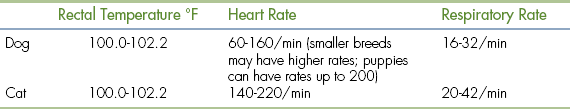

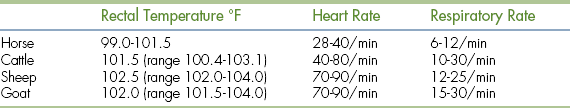

Variations from normal body temperature can be useful in determining the nature or severity of a patient’s illness. An elevated body temperature (fever or hyperthermia) usually signifies the presence of infection, inflammation, or neoplasia. However, mild elevations may be noted secondary to the stress or anxiety associated with a visit to the practice. Significant true hyperthermia may occur when heat-dissipating mechanisms cannot overcome excessive ambient temperatures (heat stroke) or secondary to certain drugs. Severe elevations (>107° F) can lead to organ dysfunction and warrant initiation of gradual cooling mechanisms. Decreased body temperature (hypothermia) is seen less commonly and usually results from impaired thermoregulation in any sick animal, especially cats. Inability to maintain body temperature is more common in patients that are young, old, or thin. Conditions that commonly result in impaired thermoregulation include chronic renal failure, hypothyroidism, and CNS disease. Severe hypothermia (<90° F) can be life threatening and requires immediate attention. Normal body temperature ranges for dogs and cats are noted in Table 8-1.

Peripheral arterial pulses should be palpated to determine pulse rate and pulse quality in every patient. Pulses are generally palpated by way of the femoral artery, which is located high on the medial thigh of the animal. Digital pressure should be applied over the femoral artery using the tips of the fingers. Some degree of pressure will be required to feel the pulse, but excessive pressure could compress the vessel making the pulse difficult to feel. The degree of pressure needed will vary from patient to patient. The pulse rate (per minute) is calculated by counting the number of pulses palpated for 15 seconds and multiplying by 4. Normal pulse rates for the dog and cat are listed in Table 8-1. It is essential to auscult the heart while palpating pulses. The heart rate and pulse rate should be identical, and there should be a pulse of approximately equal quality produced by each heartbeat. The absence of a palpable pulse (or significant change in pulse quality) with an audible heartbeat is called a pulse deficit. Pulse deficits usually indicate an abnormal heart rhythm and warrant further evaluation, such as electrocardiography.

It is also important to determine the pulse quality when palpating peripheral arterial pulses. The pressure you feel when palpating a pulse is called the pulse pressure. Pulse pressure represents the difference between the systolic and diastolic arterial pressure. The intensity of the palpated pulse will vary depending on the body condition of the animal, appearing stronger in thin animals and weaker in obese or heavily muscled animals. Pulse quality is a subjective measurement and is likely to vary from technician to technician, given the level of experience and comfort in palpating peripheral pulses. An attempt should be made to describe the intensity of the pulse using terms such as weak, moderate, or strong. In general, a weak peripheral pulse is indicative of poor perfusion and may be caused by decreased cardiac output (as in congestive heart failure or hypovolemia) or increased peripheral resistance (as in shock). Pulses may also be described as slow to rise if the peak of intensity comes late in the pulse wave. This can be seen with obstruction to cardiac output, as is seen with aortic stenosis. A pulse that feels stronger than normal may also indicate a problem. These pulses may be described as bounding, tall, or hyperkinetic. Bounding pulses may be palpated in hyperdynamic states (early septic shock, anemia) or when there is a rapid drop-off in diastolic pressure (patent ductus arteriosus). Whenever pulse quality is abnormal, an evaluation of blood pressure using direct or indirect means is warranted.

The respiratory rate and effort should be noted in all patients. An initial notation of respiratory rate and effort should be performed before any stressful manipulation of the patient because stress will commonly cause an increase in those parameters. Respiratory rates are generally done visually first and then by auscultation to actually hear lung sounds. To calculate the respiratory rate (per minute), count the number of breaths for 15 seconds and multiply by 4. Normal respiration rates for the dog and cat are listed in Table 8-1. The determination of respiratory effort is more subjective. Animals respiring with normal effort should appear comfortable and lack any abdominal effort. If abnormal effort is detected, you should attempt to determine the phase of respiration during which effort is increased. Increased inspiratory effort may indicate an upper airway problem, especially if there is an associated noise, as with laryngeal paralysis. Increased expiratory effort may indicate a small airway obstructive disease, such as asthma. However, many patients will have an increased effort throughout respiration, which is less useful in determining the source of the problem and will be discussed in more detail later in the chapter.

SYSTEMS REVIEW

Following a visual inspection of the animal in its surroundings and the notation of temperature, pulse, and respiration, a more thorough examination of individual body systems is in order. As discussed earlier, the body systems examinations should be done in the same order in every patient to prevent overlooking any aspect of the physical exam. A consistent routine will ensure thorough physical examinations. However, the degree of detail with which you examine each system will vary from patient to patient based on their presenting complaint.

Oropharyngeal System

Diseases of the oral cavity may cause loss of appetite, difficulty chewing, or halitosis. Dental disease (such as periodontal disease) is common in small animal patients. As such, a good oropharyngeal examination is an important part of the physical examination. An oral examination can be easily performed in most patients by lifting the lips with the mouth closed and by opening the mouth. However, caution should be taken during an oral examination, especially in uncooperative patients. Teeth should be examined visually for any evidence of discoloration, fracture, or excessive tartar formation. Abnormal teeth should be gently palpated to assess for pain and to determine if the tooth is loose (suggesting periodontal disease). Any missing teeth should be noted and recorded in the medical record. The gums should be examined for redness, which could indicate gingivitis, the precursor to periodontal disease. Any gingival swelling should be noted. Focal swellings could represent neoplastic masses or tooth root abscesses. More diffuse swelling can be seen with gingival hyperplasia. Gingival ulcers may be seen with renal disease, feline viral upper respiratory disease (herpesvirus, calicivirus), or ingestion of caustic substances. An examination with the mouth open will allow an inspection of the lingual surface of teeth and gums. This also allows an examination of the tongue for swelling, discoloration, or ulceration. You should always look under the tongue by pushing upward from under the jaw between the two rami of the mandible. An inspection under the tongue may reveal abnormalities, such as masses (sublingual squamous cell carcinoma [Figure 8-2]), swelling (a ranula or salivary mucocele), or foreign material (string around the base of a cat’s tongue with a linear foreign body). An open-mouth examination also allows the inspection of the roof of the oral cavity (soft and hard palate) and the back of the oral cavity (pharynx, larynx). These areas should similarly be visually inspected for any swelling or mass, discoloration, or foreign material. Some pharyngeal masses may be large enough that they can be palpated externally by feeling the area just caudal to the mandible and cranial to the tracheal cartilage. More detail regarding an oropharyngeal examination and dental disease can be found in Chapter 32.

Eyes

A good initial ocular examination can be performed without any specialized equipment and should include an examination of the eyelids and external and internal structures of the eyes. It should also include an assessment of the patient’s visual status. An examination of the eyelids should strive to identify any redness or swelling. The eyelid margins should be evaluated for evidence of masses or abnormal hairs (especially if they appear to be growing in toward the eye and causing irritation of the eye). Finally the position of the lower eyelid should be examined to see if the lower lid is rolling in toward the eye (entropion) or out away from the eye (ectropion) because both of these conditions can lead to ocular problems. Any ocular discharge should be noted and described in regard to symmetry (unilateral, bilateral) and character (serous, mucoid, purulent, hemorrhagic). Excessive tearing or squinting of the eye may indicate irritation and should be noted. A general visual inspection of the globes should be performed to determine whether they are symmetrical and whether they are enlarged and/or protruding (as can be seen with glaucoma or lesions behind the eye) or sunken. The globes can be gently pressed with the thumbs over the eyelids. They may feel extremely firm when the intraocular pressure is high (such as with glaucoma) or soft when the intraocular pressure is low (such as with uveitis). If the eyes cannot be pushed backward (retropulsed) slightly, there may be a lesion (such as a mass) behind one or both eyes.

The external parts of the eye that can be evaluated include the conjunctiva, sclera, nictitating membrane, and cornea. The conjunctiva is the pink membrane that can be seen by pulling back the upper or lower eyelids and covers the outer part of the eye up to where the cornea begins. Redness of the conjunctiva (conjunctival hyperemia) is seen with many diseases of the external part of the eye, such as conjunctivitis. The sclera is the normally white part of the eye. It is an easy place to examine for the yellow discoloration seen with icterus (Figure 8-3). Redness seen in the sclera may be caused by conjunctival hyperemia (usually diffuse with small moveable blood vessels), episcleral injection (large straight blood vessels, often indicative of internal ocular disease), or subconjunctival hemorrhage (usually large, round to irregular blotches). Any eye redness should be recorded and reported to the veterinarian for further evaluation. The nictitating membrane (third eyelid) is usually not visible or only partially visible, and it rests beneath the lower eyelid on the medial aspect of the orbit. If the nictitating membranes are visible, that is abnormal and should be noted. If not, they can be briefly examined by pressing inward on the eye, causing the nictitating membrane to rise. They should be evaluated for swelling, redness, masses, or foreign material. The cornea is the transparent covering of the front of the eye, and it should be clear. It should be examined for cloudiness or other precipitates (such as pigment). Corneal ulcers are fairly common, and although fluorescein staining is usually required to recognize a corneal ulcer, deeper ulcers may be identifiable with only a visual inspection. A diseased cornea may have blood vessels growing into it (especially toward an area of ulceration to help with healing), and these should be noted.

The internal structures of the eye that can be evaluated without specialized equipment include the iris, lens, and anterior chamber. The iris is the colored part of the eye. It should be evaluated for swelling, discoloration, irregularity, or masses. The pupil is the opening of the iris. The pupils should always be evaluated for the degree of constriction or dilation and for symmetry of size. If the pupils are of differing sizes, this is referred to as anisocoria. The pupillary light response should be examined in all patients. When a light of sufficient strength is shone into one pupil, both that pupil and the opposite pupil should constrict. Anisocoria and abnormal pupillary light responses can indicate various ocular and neurologic diseases. The lens is the part of the eye responsible for focusing images onto the retina, and it is located inside the pupillary opening. In a normal patient, the lens is not visible without specialized equipment. However, increased lens opacity may be seen with nuclear sclerosis (a normal aging change seen commonly in dogs) or cataract formation. The anterior chamber is the part of the eye behind the cornea, but in front of the iris. This area should normally be clear, and there should be no difficulty in seeing the structures behind it. Cloudiness, pus, or blood may be present in the anterior chamber in association with severe ocular inflammation. Rarely, masses may be seen in the anterior chamber.

A simple evaluation of the patient’s visual ability can be made as they are walking in or around the examination room. Most blind patients will have difficulty getting around in the unfamiliar setting of the veterinary hospital, even if they have accommodated for their blindness well at home. Another way to assess a patient’s ability to see is to test their menace reflex by covering one eye (so you are testing only one eye at a time) and making a menacing gesture toward the other eye with your hand (being sure not to touch the patient or create excessive air movement that they could feel). A visual patient will close the eye in response to this gesture (assuming they are old enough to recognize that your gesture is menacing and that they have an intact facial nerve and are capable of blinking). You may also assess vision by dropping cotton balls in front of the patient from above their head and noting whether they visually follow the cotton balls as they pass by.

Ears

The examination of the ears should begin with the visualization and palpation of the pinnae. During visualization, the pinnae should be evaluated for symmetry (though in some patients asymmetry may be normal) and inspected inside and outside for swelling, redness, alopecia, crusting, or evidence of excoriation. Inside the pinnae is a common place to recognize petechiation, indicative of a primary hemostatic defect (such as thrombocytopenia) (Figure 8-4). Palpation of the pinnae will allow for recognition of focal swelling (such as with aural hematoma) or diffuse thickening (as might be seen with chronic otitis). Lifting and/or pulling back the pinnae will allow for a visual inspection of the external ear canal. The canine and feline ear canals consist of a vertical canal that opens to the external environment and runs inward parallel to the skull and a horizontal canal that is a short section between the vertical canal and eardrum, which runs more perpendicular to the skull. Only the vertical canal may be visualized without specialized equipment. This area should be evaluated for discharge, thickening and/or swelling, or masses. Aural discharge should be described in terms of amount (mild, moderate, severe) and appearance (waxy, black, hemorrhagic, purulent). The evaluation of the horizontal canal and eardrum requires the use of an otoscope.

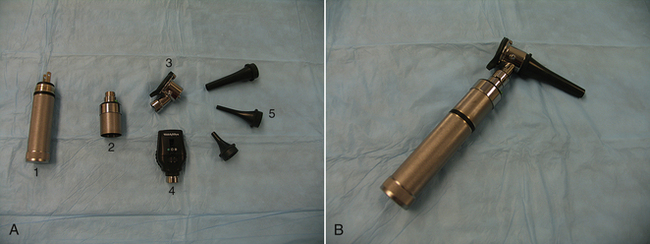

Most otoscopes found in veterinary practice will be wall mounted or portable. They typically consist of a handle, which allows the examiner to hold the instrument, and a head, through which the examiner visualizes the structures. For otoscopy, a cone is attached to the head. The cone is a gradually tapering tube, which fits nicely into the ear canal, through which the otoscope light shines to allow visualization. The majority of otoscopes can also be used as ophthalmoscopes by changing the head. Wall-mounted otoscopes usually have a base that plugs into an electrical outlet and hangs on the wall. The handle is attached to the base via a cord that supplies the power to light the otoscope. The handle is permanently attached to the base. The only assembly that is needed for use is to change the cone to match the size of the patient undergoing an examination. The cone should be large enough to allow a clear visualization of the structures inside the ear canal, but small enough so as not to cause the patient discomfort. The wall-mounted otoscopes have the advantage of always being ready for use and requiring little assembly, but they lack the flexibility of the portable units in terms of where the patient is positioned. For the wall-mounted units, the patient must be fairly close to the wall-mounted base, but for the portable units, the patient can be anywhere. The portable unit consists of a handle that contains a rechargeable battery to power the light source, a connecting piece that attaches the handle to the head, and the head (Figure 8-5). As with the wall-mounted unit, a cone must be attached to the head for an examination. The disadvantages of the portable otoscope are that the battery requires recharging and may not always be ready when needed and that the otoscope needs to be assembled before use.

FIGURE 8-5 A, Components of a portable otoscope/ophthalmoscope. 1, Handle. 2, Connecting piece. 3, Otoscope head. 4, Ophthalmoscope head. 5, Otoscope cones of varying size. B, Assembled portable otoscope.

To examine the horizontal canal and eardrum using an otoscope, the pinnae is first gently pulled upward (opposite the direction of the patient’s legs) to lessen the angle between the vertical and horizontal canals. At this point, the otoscope cone is gently passed into the vertical canal while the examiner is looking through the head. The cone is gently advanced into the horizontal canal until the eardrum is visualized or until the patient shows evidence of discomfort (Figure 8-6). During passage of the otoscope through the vertical and horizontal canals, those areas should be examined for evidence of redness, swelling, masses, discharge, excess hair, or foreign material. The eardrum should appear as a grey to white, slightly transparent, round membrane separating the inner ear from the external ear canal. Abnormalities of the eardrum that should be noted include tears or perforation of the eardrum, increased thickness (or decreased transparency), or evidence of discharge behind the eardrum. It should be noted that an otoscopic examination is technically challenging and resisted by many patients. The visualization of the eardrum may be difficult for the novice technician, and only through frequent practice will the technique of otoscopy become comfortable.

Respiratory

The initial examination of a patient’s respiratory status involves a visual determination of respiratory rate and effort as discussed previously. Patients in significant respiratory distress should be provided with supplemental oxygen and minimally stressed. The remainder of the physical examination should be brief or potentially postponed until the patient is more stable.

In a stable patient, an examination of the respiratory system should begin with the evaluation of the upper respiratory tract. The nares should be visually inspected to ensure symmetry and patency. Patency can be evaluated by holding a glass slide in front of the nares and looking for condensation to form from each nostril as the animal exhales. The nares should also be evaluated for normal opening size, especially in brachycephalic breeds of dogs, in which stenotic nares are common. Nasal discharge should be described in terms of symmetry (unilateral, bilateral), severity (mild, moderate, severe), and character (serous, mucoid, purulent, hemorrhagic). Opening the mouth and briefly visualizing the hard and soft palate at the roof of the mouth will allow a crude inspection of the nasopharynx for masses, which may appear as a bulging downward of the palate. Any clinical signs of upper airway disease noted during an examination should be recorded, such as sneezing, stertor, or stridor.

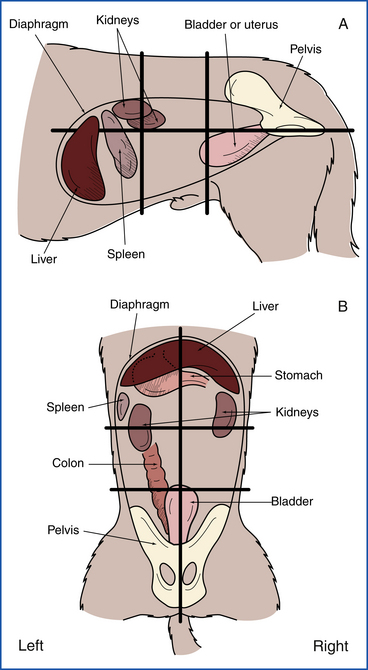

Auscultation using a stethoscope comprises the remainder of the respiratory examination. Most stethoscopes used in veterinary medicine are acoustic stethoscopes, which consist of a chest piece that contacts the patient and transmits sounds via hollow tubes to the examiner’s ears (Figure 8-7). Electronic stethoscopes are less common. A stethoscope should be used such that the earpieces are pointing toward the examiner’s nose when they are placed into the ears. The chest piece on most stethoscopes consists of two sides: a flat side called the diaphragm and a cup-shaped side called the bell. The diaphragm, which transmits high frequency sounds, is used most commonly and is appropriate for lung auscultation. The bell, which transmits low frequency sounds, is used less frequently and may enhance the ability to hear certain cardiac sounds, such as those associated with a gallop rhythm. Twisting the chest piece 180° within the tubing will change whether the bell or diaphragm is active. Some stethoscopes do not have a separate bell and diaphragm, but can function as both if the pressure with which the chest piece is applied to the patient is varied.

FIGURE 8-7 Stethoscopes. 1, Chest piece with separate bell and diaphragm 2, Chest piece with integrated bell and diaphragm.

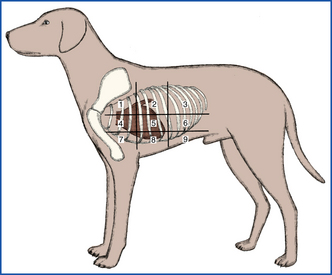

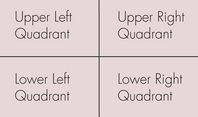

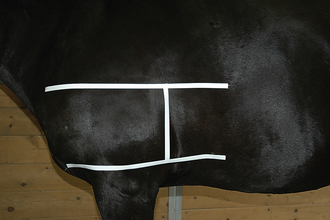

When performing respiratory auscultation, the patient should be in a quiet room. Many things can hamper your ability to effectively auscultate a patient, including ambient noise, the patient’s movement (causing hair rubbing to be heard through the ear pieces), panting, or purring. The mouth should be held gently closed in a panting dog to improve auscultation. Attempts should be made to quiet a cat’s purring, such as temporarily covering the nares, running water near the cat, or holding alcohol-soaked cotton to the nares. Once the conditions are optimal, respiratory auscultation should begin with the chest piece over the trachea. Normal tracheal airflow is turbulent, and the respiratory sounds should be loud and harsh. Abnormal sounds heard over the trachea suggest a problem in the upper airway (trachea or more cranial). For example, a high-pitched inspiratory sound may indicate partial upper airway obstruction, as can be seen with laryngeal paralysis. Although these abnormal upper airway sounds will likely be transmitted to the lungs and audible during lung auscultation, they do not indicate lung disease. The lungs should be auscultated on both sides of the patient, generally dividing the lung fields into nine quadrants on each side (Figure 8-8). Each quadrant should be auscultated through at least two to three respiratory cycles of inspiration and expiration. In a normal patient, air movement will be audible during both inspiration and expiration, but should be of minimal intensity. The intensity of normal lung sounds will vary with the body condition of the patient; the sounds are more intense in thin patients and less intense in obese or well-muscled patients. The most commonly identified abnormal lung sounds are crackles and wheezes. Inspiratory crackles usually indicate the presence of fluid within alveoli, as can be seen with pulmonary edema. Wheezes may occur during inspiration and/or expiration when air is moving through a narrowed airway, as can be seen with feline asthma. Failure to hear any air movement is also a sign of a problem. A lack of lung sounds occurring in the ventral lung fields in the standing animal usually indicates pleural effusion because the fluid tends to settle in the ventral areas. Conversely a lack of sounds in the dorsal lung fields often indicates a pneumothorax because the air will rise to the dorsal areas. Space-occupying masses and lung consolidation can also result in the absence of lung sounds. When abnormal lung sounds are auscultated (or lung sounds are absent), the technician should note whether they are occurring during inspiration or expiration and in which lung fields they were identified.

Cardiovascular System

The examination of the cardiovascular system begins with a look in the mouth. Rather than looking for specific oral pathologic conditions, we are looking at the gingival mucous membranes to gain an assessment of perfusion status. The gingival mucous membranes should be pink and moist, though some animals will have normally pigmented gingivae. Pallor of the mucous membranes usually indicates anemia or poor perfusion. Hyperemia of the mucous membranes can occur in stressed animals or can be seen in hyperdynamic states, such as the early phase of septic shock. If the mucous membranes are not moist but are dry or tacky, this is usually an early sign of dehydration. However, in a patient that is panting excessively, the mucous membranes will be dried by the air movement associated with panting, and mucous membranes will not be a good indicator of hydration status. The gingival mucous membranes are also used for measuring the capillary refill time, which serves as another indicator of perfusion. With the lip raised, the gingival surface is gently pressed with a finger to occlude blood flow until the color fades from the mucous membrane beneath the finger. The finger is removed, and the time it takes for the mucous membrane color to return to normal is measured (Figure 8-9). In a normal animal, this capillary refill time will be less than 2 seconds. Refill times longer than 2 seconds are indicative of poor perfusion, as can be seen with hypotensive states. Extremely rapid refill (<1 second) may be seen in stressed patients or in hyperdynamic states, such as the early phase of septic shock. The peripheral arterial pulse quality will also provide information regarding perfusion as discussed previously.

FIGURE 8-9 Assessing capillary refill time. A, Visualize the gingival mucous membranes by lifting the lip. B, Apply gentle pressure with the thumb onto the mucous membranes. C, Resultant area of pallor when the thumb is removed. D, Note time to return of normal mucous membrane color.

Cardiac auscultation will allow evaluation for abnormal heart rate, rhythm, and sounds. In dogs, the heart should be auscultated on each side of the chest around the level of the costochondral junction (just behind the level of the elbow when the patient is standing). By moving the chest piece around slightly, you will be able to auscultate in the vicinity of each heart valve. The pulmonic, aortic, and mitral valves can be auscultated best on the left side, whereas the tricuspid valve is auscultated best on the right side (Figure 8-10). Normal heart rates have been discussed previously. In cats, it is best to auscultate directly over the sternum initially and move the chest piece gradually up to the left side and back over to the right side. The valve positions are similar to the dog, but in cats, abnormal heart sounds are more commonly auscultated in the sternal area. The heart rhythm should be regular, meaning that each heartbeat is separated from the following one by an identical time interval. Dogs may normally have a slight variation in heart rhythm, such that the heart rate increases slightly during inspiration and decreases slightly during expiration. This is called respiratory sinus arrhythmia, and it is a sign that a dog has normal cardiac function. To best evaluate the cardiac rhythm, the pulses must be palpated during auscultation. As discussed previously, there should be a pulse of approximately equal intensity generated with each heartbeat. In a patient with an abnormal heart rhythm or with pulse deficits, electrocardiography should be performed to determine the exact nature of the abnormality.

FIGURE 8-10 Location of heart valves as an aid in the determination of the origin of a heart murmur. A, aortic; M, mitral; P, pulmonic; T, tricuspid. (From McCurnin DM, Poffenbarger EM: Small animal physical diagnosis and clinical procedures, St Louis, 1991, WB Saunders.)

The heart sounds typically audible during auscultation in a normal patient are S1 (the first heart sound), which is created by closure of the mitral and tricuspid valves at the start of systole, and S2 (the second heart sound), which is created by closure of the aortic and pulmonic valves at the end of systole. These two short heart sounds result in the typical “lub-dub” sound of the normal heartbeat. The presence of a third heart sound is termed a gallop rhythm because the resulting heart rhythm sounds like the galloping of a horse. A gallop rhythm is not actually an abnormal rhythm in the sense of electrical activity, but is caused by an extra heart sound termed either S3 or S4. S3 is usually associated with ventricular dilation, such as with dilated cardiomyopathy, whereas S4 is usually associated with decreased ventricular compliance and hypertrophy, such as with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. S3 and S4 cannot be differentiated via auscultation. Rarely the second heart sound (S2) may be split and sound like a third heart sound. This phenomenon is uncommon.

A heart murmur is an abnormal sound caused by turbulent blood flow which typically sounds like a “swishing” noise. Identification of heart murmurs can indicate cardiac disease, though they can occur with noncardiac disease (such as with anemia) or can be normal in some young animals. Heart murmurs should be described by their intensity, when they occur in the cardiac cycle, and where they are heard loudest. The intensity of a heart murmur is typically graded on a scale from I to VI, as shown in Table 8-2. Systolic murmurs occur between S1 and S2 (i.e., during systole) or may mask those two sounds. Diastolic murmurs occur after S2 and before the next S1 (i.e., during diastole). A continuous murmur occurs throughout the cardiac cycle. The area on the chest where a murmur is loudest is termed the point of maximal intensity. For dogs, this point is usually identified in relation to the location of heart valves, as shown in Figure 8-10. For cats, this point may more easily be described in relation to the sternum (such as midsternum or left parasternum) since many feline murmurs are best auscultated in this area.

TABLE 8-2

Grading of Heart Murmurs in Small Animals

| Grade | Description |

| I | Very low intensity murmur that can only be heard in a quiet area |

| II | Murmur of soft intensity that can be heard immediately |

| III | Murmur of moderate intensity |

| IV | Loud murmur |

| V | Loud murmur with a palpable thrill on the body wall |

| VI | Loud murmur that can be heard with the stethoscope held some distance from the thoracic wall |

The final part of a thorough cardiovascular exam is evaluation of jugular veins. In a short-haired patient, the jugular veins can be visualized on either side of the trachea with the patient’s muzzle lifted dorsally in a standing or sitting position. In animals with thicker or longer coats, the hair may need to be clipped or wet down to allow an evaluation. Normal patients should have jugular pulsations that do not extend more than one third up the neck. The jugular veins drain blood into the right atrium, and their pulsations and distension give a direct indication of right atrial pressure. Distended jugular veins extending farther up the neck can be seen in any disease causing elevated central venous pressure, especially those causing increased right atrial pressure, such as a pericardial effusion or pulmonic stenosis.

Gastrointestinal System

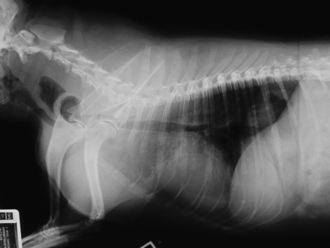

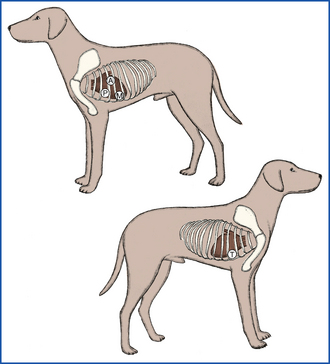

This section of the physical examination would more appropriately be called “abdominal palpation” because it actually involves the assessment of more than just the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. During abdominal palpation, other abdominal organs will be examined, including liver, spleen, kidneys, and urinary bladder. The technique of abdominal palpation can be difficult for the novice technician, but with practice, one can become quite proficient. As with the physical examination as a whole, following a consistent routine every time abdominal palpation is performed will ensure that nothing is missed. A thorough understanding of the anatomic location of the abdominal organs within the abdominal cavity is essential for effective palpation. Figure 8-11 shows the location of the abdominal organs within the abdomen. For the purposes of description, the abdomen can be divided into six sections (cranial-dorsal, cranial-ventral, middorsal, midventral, caudal-dorsal, caudal-ventral). For most dogs, the two-handed technique is the best method (Figure 8-12). For small dogs and cats, a one-handed technique (Figure 8-13) may be easier, using the general principles discussed later for the two-handed technique. With the patient in the standing position, the examiner should stand just behind the patient or stand straddling the caudal end of the patient. This will allow the placement of one hand on either side of the abdomen. The hands should be in a flat, relaxed position. Palpation should begin in one section (such as cranial-dorsal). The hands should be moved gently toward each other in a smooth, fluid motion. The hands and fingers should remain relaxed, and excessive pressure should not be exerted so the patient does not tense its abdominal muscles (as this makes delineation of organs difficult). The palpation should move slowly and methodically through all the other sections of the abdomen. The progression should be the same each time you palpate a patient. Within each section, you should be noting any pain, swelling, firmness, or fluid. These findings should be recorded as to their severity and location (which section, left or right side). Be as specific as possible in your descriptions.

FIGURE 8-11 Location of internal organs within the abdominal quadrants. A, Lateral projection. B, Dorsoventral projection.

Specific organs should be palpated in their respective regions. The liver should not be palpable in the normal animal, but if it is enlarged or contains a mass, it may be palpated in the cranial-ventral abdomen just caudal to the rib margin. The spleen is usually palpable in the cranial-ventral or midventral abdomen more on the left side. It should be gently palpated for enlargement or masses. The kidneys reside in the cranial-dorsal or middorsal abdomen and cannot be palpated in most dogs because they are encased in quite a bit of fat and are not moveable. However, they may be palpated in thin dogs or when there is renomegaly. Pain in those sections of the abdomen may represent renal pain. In cats, the kidneys are much more moveable and much more easily palpable. They are usually just caudal to the ribs in the dorsal abdomen and can be freely moved in most cats. They should be palpated for irregularities in size or shape and for evidence of pain. The urinary bladder can be easily palpated in the caudal-ventral abdomen, assuming it is not empty and that the patient is cooperative. Identification of the urinary bladder makes cystocentesis possible. The urinary bladder should also be palpated for distension or thickness. On rare occasions, bladder stones may be palpable on a physical examination. In male dogs, the prostate gland may be palpable in the caudal-dorsal abdomen, especially if it is significantly enlarged. However, the prostate is usually best examined via a rectal examination.

The GI tract can be examined during abdominal palpation to some extent. The stomach is usually not palpable if it is empty, but if there is gastric distension or a mass, it may be palpable in the cranial-dorsal abdomen (or farther caudal with severe distension). The small intestines are generally palpable as loops passing through your fingers in much of the midabdomen. It is not possible to delineate the different sections of small intestine by palpation. Small intestinal masses should be easily palpable, but other intestinal changes, such as wall thickening, are usually subtle and difficult to appreciate. The large intestine can usually be palpated in the middorsal and caudal-dorsal abdomen as it courses toward the rectum, assuming that it contains formed feces. If it is empty, it may not be as easily palpable. Good palpation may allow for identification of large intestinal masses or of constipation or obstipation. Remember that a complete GI examination includes an examination of the oral cavity, pharynx, rectum, and anus. The examination of these areas is discussed in other sections.

Rectal Examination

A rectal examination should be performed in almost every canine patient. In cats and small dogs, a rectal examination may be prohibitively painful and should only be performed in patients with a presenting complaint that may bereferable to that area. A thorough rectal examination can be quick and provide a significant amount of useful information. The examination is typically performed using a well-lubricated, gloved index finger (though the pinkie finger can be used in smaller patients). Before examining the rectum, the perineal area and anus should be examined for redness,

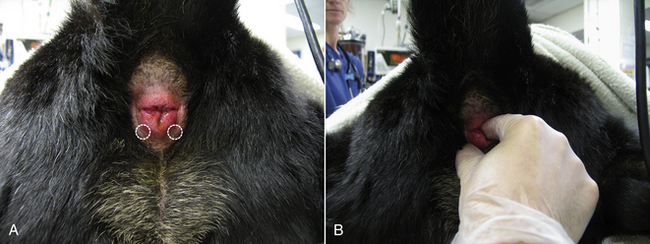

swelling, masses, discharge, or other abnormalities. The finger is passed gently through the anal sphincter with the knuckles aimed dorsally. The finger is placed in as far as is comfortable for the patient, and structures are examined moving caudally. In the male dog, the prostate gland may be palpated ventral to the rectum cranial to the pelvic brim. It should be palpable in most intact dogs and in any dog with prostatomegaly. The normal gland is bilobed with a median raphe and should be smooth, symmetrical, and nonpainful. Enlargement or pain on palpation may be indicative of prostatic infection or neoplasia. Moving caudally, the urethra can be palpated ventral to the rectum as it courses caudally from the urinary bladder. Feel carefully for any irregularities (such as stones or masses). Dorsal to the rectum, the medial iliac lymph nodes are present to either side of the midline and may be palpated if they are enlarged. The inner mucosa of the rectum should be palpated during the examination by running the finger 360 degrees around the wall at various levels. The rectal wall should be evaluated for irregularity, thickness, or masses. The character of the stool within the rectum (if present) should be noted. If possible, a sample of stool should be removed with the gloved finger and examined. Finally the anal sacs can be palpated. The anal sacs lie just behind the anal mucosa with one on either side, located at approximately 5 and 7 o’clock (Figure 8-14, A). The anal sacs can be palpated by moving the finger within the rectum laterally and caudally while gently pressing with the thumb on the outside of the anus. Normal anal sacs should be small (<1 cm) and firm but slightly fluctuant. Distended anal sacs likely contain normal anal sac fluid, but could contain a mass. The sacs must both be fully expressed to confirm whether or not there is a mass present. This should be done in any patient with a palpably distended anal sac. Each sac opens at the rectal-anal junction adjacent to the location of the sac. The anal sacs are expressed by gently applying pressure with the thumb and finger during palpation (Figure 8-14, B). The anal sac fluid can vary in appearance from whitish to dark brown and can vary in consistency from watery to fairly thick. Evidence of blood or pus may indicate anal sac infection. Thick material can result in an anal sac impaction, which can be uncomfortable to the patient and lead to scooting of the rear end. Anal sac expression can be difficult in patients with an impaction and may require sedation.

Urogenital

Much of the urinary system is evaluated during abdominal palpation and a rectal examination as discussed previously. The kidneys, urinary bladder, and proximal urethra have already been examined. The only part of the urinary system left to be evaluated is the distal urethra, which opens at the tip of the penis in the male and into the vestibule in the female. In male dogs, the penis should be gently extruded by pulling back the skin of the prepuce. Any discharge within the prepuce should be noted. The penis should be evaluated to ensure that the urethral opening is normal and appears patent. Any masses or wounds on the penis should be noted. Penile examination is not typically performed in the male cat except when the patient is sedated, such as would occur during urethral obstruction. Examination of the vagina and vestibule is not routinely performed in dogs and cats. In cases with a presenting complaint referable to the lower urinary tract, a vaginal examination may be indicated. A digital vaginal examination may be performed in the awake dog, but often sedation will be necessary. Sedation will always be required in the cat. In either case, the examiner should wear sterile gloves and use copious lubrication to prevent trauma and discomfort to the patient.

In the United States, the vast majority of dogs and cats are neutered. As such, an examination of reproductive organs is not commonly performed. In the intact male dog or cat, the testicles should be examined. The scrotum should be gently palpated to ensure that both testicles are present. Testicles should descend into the scrotum by 8 weeks of age in most patients and by 6 months in all patients. The testicles should be gently palpated to assess for any asymmetry in size, masses, heat, or pain. The penis should be extruded and examined as described earlier. In the intact female dog or cat, the reproductive organs are not as easily examined. A vaginal examination may be performed as described previously, but is not part of a routine examination. The uterus cannot be palpated during abdominal palpation unless it is enlarged, such as with pregnancy or pyometra. The ovaries cannot be palpated. It is good practice to palpate the mammary chains in all female dogs and cats, but it is especially important in sexually intact patients because they have a much higher risk of mammary cancer. Most dogs and cats will have five mammary glands on each side of the ventral abdomen. They should be gently palpated for heat, swelling, masses, or discharge. In lactating animals, milk should be expressed and examined.

Integument

A complete evaluation of the integumentary system will include an examination of the hair, skin (including footpads and nails), and subcutaneous tissues. The character of the normal hair coat can vary greatly between breeds and between individual patients, but in general, it should be thick and shiny. Abnormal hair coats may be dull or greasy. They may contain scale (flakes of shed epidermis). The coat should be visually evaluated for areas of thinning or alopecia (Figure 8-15). If alopecia is noted, it should be described in terms of location (focal versus diffuse versus patchy, unilateral versus bilateral, symmetric versus asymmetric) and degree (partial versus complete). The coat should be inspected closely in alopecic areas. The examiner should look for evidence of broken hairs, which may indicate that the alopecia is caused by scratching or barbering. The skin should also be examined in the alopecic area for evidence of excoriation or underlying disease. The hair should be gently parted in several areas to look for evidence of ectoparasites, such as fleas. In highly suspicious cases, such as extremely pruritic animals, a flea comb can be used to improve the chances of identifying live fleas or their excrement.

The extent to which the skin is directly examined will depend on the presenting complaint of the patient. A patient with no complaints referable to the skin (such as pruritus, flaking, or odor) need only have a cursory skin exam. Patients with complaints referable to the skin warrant a more thorough evaluation. In any patient lacking alopecia, the hair must be parted to allow an evaluation of the skin. The ventral caudal abdomen has a light covering of hair in many patients and is a good place to visualize the skin. Common abnormalities that can be identified on the skin include papules and pustules, which are seen commonly with a bacterial skin infection. A papule is a small pink or red elevated skin lesion smaller than 0.5 cm in diameter. A pustule is similar in size to a papule, but is a raised area containing pus, which usually has a pink or red base with a white tip. Scale and crusts are caused by any inflammatory process affecting the outer layers of skin. Both appear as flakes and contain shed epidermal cells, but crusts also contain inflammatory cells. They can be difficult to differentiate based on a visual inspection alone. Excoriations are areas of self-trauma caused by scratching in a pruritic animal. The skin is a good area to see petechiae and ecchymoses, which usually indicate a primary hemostatic defect. Erythema (redness) of the skin may be noted focally or diffusely. Nail beds and footpads should be examined, especially in patients with diseased skin, to evaluate for redness, discharge, or ulceration.

Masses are commonly found on the skin and within the subcutaneous tissues in veterinary patients. Most masses will be caused by benign neoplastic processes, though palpable masses may represent malignancy, vaccine reactions, abscesses, or swelling caused by trauma. It is important that any masses be noted in the medical record with great detail so that any changes in their size or appearance can be noted. Masses should be described based on their location, including whether they are on the surface of the skin (cutaneous) or under the skin (subcutaneous). Their exact location can be recorded in the medical record by using a body map. Such a map will allow for the precise marking of the location of the mass and is much more effective than written descriptions for comparisons with future examinations. The size and shape of the mass should be noted. The size is most precisely recorded using measuring calipers, though it can be estimated if calipers are not available. The mass should also be described as soft, fluctuant, or firm. Its adherence to underlying structures should be noted by recording whether it is moveable or fixed. Careful monitoring of cutaneous and subcutaneous masses is important in determining a diagnostic and therapeutic plan.

Lymph Nodes

In the normal patient, the peripheral lymph nodes that can be palpated are the mandibular, prescapular, and popliteal lymph nodes. Axillary and inguinal lymph nodes are typically only palpable when they are significantly enlarged. Similarly, enlarged medial iliac lymph nodes may be palpable via a rectal examination as discussed earlier. The mandibular lymph nodes are located on either side of the neck just caudal-dorsal to the ramus of the mandible and cranial-ventral to the mandibular salivary glands. They can be differentiated from the salivary gland because they tend to be more moveable, slightly firmer, and smaller (in the normal patient). The prescapular lymph nodes are located in the subcutaneous tissue just medial to the scapular-humeral joint on either side of the patient. These nodes are often encased in fat and may feel slightly softer than other normal nodes. The popliteal lymph nodes are located on the caudal aspect of each hind limb at the level of the stifle joint. The axillary lymph nodes, if palpable, will be located in the subcutaneous space on the lateral aspect of the ventral thorax under the arm. The inguinal lymph nodes are located in the most caudal part of the ventral abdomen, just medial to the thighs, on either side of the midline.

Lymph nodes should be palpated by gently isolating them between the thumb and index finger. Ideally the left and right lymph nodes are palpated simultaneously at each location to determine whether they are identical in size and shape. Normal lymph nodes are round to oval in shape, slightly moveable, and firm, but slightly compressible. Abnormal lymph nodes may be enlarged, firm, warm, or painful. The most common abnormality palpated is an enlarged lymph node. It should be noted that lymph nodes in young animals (less than 6 months of age) are normally mildly enlarged as compared with the size that they will be during adulthood. Lymph node enlargement may indicate that the node is infected, reacting to local inflammation, or neoplastic. Enlargement should be noted as focal (single node or single region) or generalized (all palpable nodes enlarged). The specific nodes that are enlarged should be noted and their size measured with calipers or estimated.

Musculoskeletal System

The examination of the musculoskeletal system will vary greatly depending on the patient’s presenting complaint. In a patient without symptoms referable to the musculoskeletal system (such as lameness, swelling, difficulty rising, or pain), the examination will be fairly cursory. Every patient should be observed as they walk around the examination room or waiting area for signs of lameness that the owner may not have perceived. In patients lacking lameness, the musculoskeletal examination should include a visual inspection of the standing animal for asymmetry of the limbs. This is followed by gentle palpation of each limb and the vertebral column over the neck and back. Initial palpation of limbs should be performed such that opposite sides are examined simultaneously (i.e., left and right forelimb, left and right hind limb). This will allow for a comparison with the opposite leg when evaluating swelling or pain.

In a patient that is seen with a complaint referable to the musculoskeletal system, such as lameness, or one in which the cursory musculoskeletal examination revealed an abnormality, a more thorough examination is indicated. This should start with observation of the animal walking or jogging on a lead for identification of lameness. Animals will put less weight on a painful limb when walking, shifting the weight to the good limb. This results in the patient putting their head down when stepping on the good limb and pulling the head up when stepping on the painful limb. Once the affected limb has been identified, the patient should be placed in lateral recumbency and each limb thoroughly examined one at a time. The soft tissues and long bones of the limb should be palpated with gradually increasing levels of pressure to identify swelling or pain. Then, starting at the toes, every joint should be put through a range of flexion and extension trying to isolate the examined joint and not move any other joints. It is important to examine all the limbs so that perceived discomfort in one limb can be compared with the opposite limb. If you identify pain in one limb and the patient does not show a similar response in the other limbs, you have likely identified a problem. The bones of the vertebral column should be palpated one at a time by pressing down on their dorsal surface on the animal’s back. The neck should be put through a full range of motion and any pain noted.

Nervous System

Similar to the musculoskeletal examination, the time allotted to the neurologic examination will vary greatly depending on the patient. The examination of every patient will include a subjective visual evaluation of mentation, visual acuity, and gait as it enters the examination room, as described in the section on observing patients in their surroundings. Most patients will have menace and pupillary light reflex testing performed as part of the eye examination. If these parameters are considered normal and the patient does not have any complaints that could be referable to the nervous system, the neurologic examination need not be any more extensive.

A patient with an abnormality noted on the cursory examination or one with a complaint that could be referable to the nervous system should have a more complete neurologic examination. Presenting complaints that could be referable to the nervous system include, but are not limited to, behavior changes, depression, lethargy, blindness, head tilt, circling, lameness, weakness, or paralysis. A complete neurologic examination includes an evaluation of mentation, gait and posture, muscle tone, cranial nerves, postural reactions, and reflexes. Mentation is assessed subjectively during visual observation of the patient and may be described as bright and alert, quiet, dull or obtunded (not interested in surroundings), stuporous (responsive only to noxious stimuli), or comatose (unresponsive to stimuli). The gait and posture are also observed. The patient should be walked or jogged on a lead and made to turn when assessing a gait. Although animals with neurologic disease can have a normal gait and posture, ataxia is a common gait abnormality in these patients. Ataxia is a term used to describe uncoordinated muscle movements when walking. When evaluating a patient’s gait, ataxia is identified when you are unable to predict where the foot will fall on the patient’s next step. Ataxia can vary in type and severity, and it is often confused with lameness by owners. Muscle tone is subjectively assessed by a visual inspection and palpation. The evaluation of muscle tone should include determination of anal sphincter tone. During a rectal examination, the anal sphincter muscles should tighten around your finger. Muscle atrophy or decreased tone may occur in denervated muscle.

A cranial nerve examination is an essential part of every complete neurologic examination. Cranial nerve reflex tests are summarized in Table 8-3. The olfactory nerve (cranial nerve I) is not routinely tested because a patient’s response to scent is difficult to evaluate. The spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI) is not evaluated. Lesions in this nerve cause atrophy of the trapezius muscle, which can be difficult to identify. As discussed in the section on the eye examination, the pupils should be evaluated for size and symmetry, and the menace and pupillary light reflex tests should be performed. These will evaluate the optic (cranial nerve II) and oculomotor nerves (cranial nerve III). The position of the eyes at rest and the doll’s eye reflex (physiologic nystagmus) will evaluate the oculomotor, trochlear (cranial nerve IV), and abducens nerves (cranial nerve VI). The doll’s eye reflex is performed by turning the patient’s muzzle and head from left to right. As the head moves in one direction, the eyes should initially move to the opposite direction and then snap back to the center. The palpebral reflex is tested by tapping the medial and lateral canthus of the eye to induce a blink. The corneal reflex is tested by holding the eyelids open and gently touching the cornea with a wet cotton swab. Gently pinching the lips with a hemostat or placing the hemostat inside either nostril should cause the patient to move away and will evaluate the sensory portion of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). Facial symmetry should be assessed because a droop to one side compared with the other can indicate a lesion of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII). The eyes should be examined for nystagmus, which can indicate a lesion in the vestibulocochlear nerve (cranial nerve VIII). The gag reflex is performed by pressing with a finger on the back of the patient’s tongue; this should elicit contraction of the pharyngeal muscles. This evaluates the glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX) and branches of the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X). A visual examination of the tongue for determination of deviation to one side or another can identify lesions of the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII).

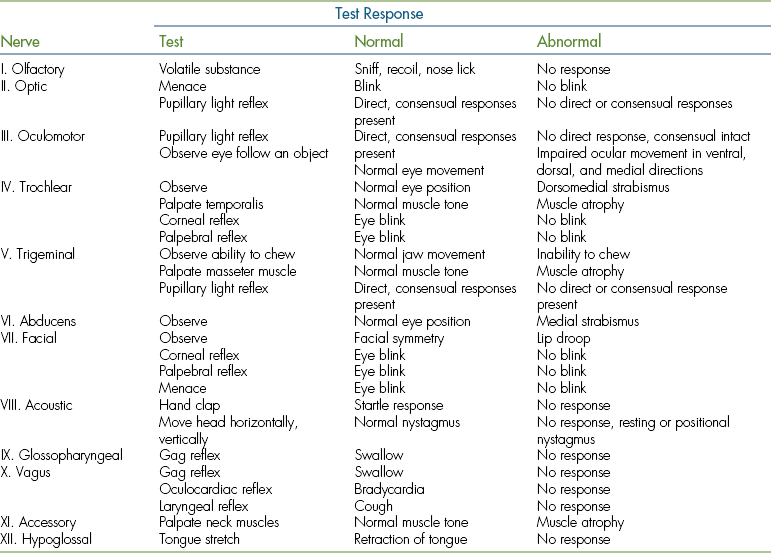

TABLE 8-3

Examination of the Cranial Nerves

From McCurnin DM, Poffenbarger EM: Small animal and physical diagnosis and clinical procedures, Philadelphia, 1991, WB Saunders.