Chapter 12 Recognizing Diseases of the Chest

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to recognize mediastinal masses, benign and malignant pulmonary neoplasms, pulmonary thromboembolic disease, and selected airway diseases.

A complete discussion of all of the abnormalities visible in the chest is beyond the scope of this text. We’ll begin here with mediastinal masses and work our way outward to the lungs.

A complete discussion of all of the abnormalities visible in the chest is beyond the scope of this text. We’ll begin here with mediastinal masses and work our way outward to the lungs.TABLE 12-1 CHEST ABNORMALITIES DISCUSSED ELSEWHERE IN THIS TEXT

| Topic | Appears in |

|---|---|

| Atelectasis | Chapter 5 |

| Pleural effusion | Chapter 6 |

| Pneumonia | Chapter 7 |

| Pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and pneumopericardium | Chapter 8 |

| Cardiac and thoracic aortic abnormalities | Chapter 9 |

| Chest trauma | Chapter 17 |

Mediastinal Masses

The mediastinum is an area whose lateral margins are defined by the medial borders of each lung, whose anterior margin is the sternum and anterior chest wall, and whose posterior margin is the spine, usually including the paravertebral gutters.

The mediastinum is an area whose lateral margins are defined by the medial borders of each lung, whose anterior margin is the sternum and anterior chest wall, and whose posterior margin is the spine, usually including the paravertebral gutters. The mediastinum can be arbitrarily subdivided into three compartments: the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments—and each contains its favorite set of diseases (Fig. 12-1).

The mediastinum can be arbitrarily subdivided into three compartments: the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments—and each contains its favorite set of diseases (Fig. 12-1).

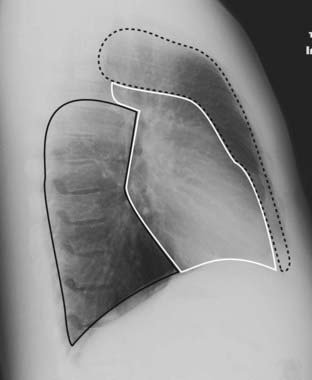

The mediastinum can be arbitrarily subdivided into three compartments: anterior, middle, and posterior, with each containing its favorite set of diseases. The anterior mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the back of the sternum to the anterior border of the heart and great vessels (dotted black outline). The middle mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the anterior border of the heart and aorta to the posterior border of the heart and origins of the great vessels (solid white outline). The posterior mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the posterior border of the heart to the anterior border of the vertebral column (solid black outline). For practical purposes, however, it is considered to extend into the paravertebral gutters.

![]() Pitfall: Since these compartments have no true anatomic boundaries, diseases from one compartment may extend into another compartment. When a mediastinal abnormality becomes extensive or a mediastinal mass becomes quite large, it is often impossible to determine which compartment was its site of origin.

Pitfall: Since these compartments have no true anatomic boundaries, diseases from one compartment may extend into another compartment. When a mediastinal abnormality becomes extensive or a mediastinal mass becomes quite large, it is often impossible to determine which compartment was its site of origin.

Differentiating a mediastinal from a parenchymal lung mass on frontal and lateral chest radiographs:

Differentiating a mediastinal from a parenchymal lung mass on frontal and lateral chest radiographs:

Anterior Mediastinum

The anterior mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the back of the sternum to the anterior border of the heart and great vessels.

The anterior mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the back of the sternum to the anterior border of the heart and great vessels. The differential diagnosis for anterior mediastinal masses most often includes:

The differential diagnosis for anterior mediastinal masses most often includes:

TABLE 12-2 ANTERIOR MEDIASTINAL MASSES (“3 Ts and an L”)

| Mass | What to Look For |

|---|---|

| Thyroid goiter | The only anterior mediastinal mass that routinely deviates the trachea |

| Lymphoma (lymphadenopathy) | Lobulated, polycyclic mass, frequently asymmetrical, that may occur in any compartment of the mediastinum |

| Thymoma | Look for a well-marginated mass that may be associated with myasthenia gravis |

| Teratoma | Well-marginated mass that may contain fat and calcium on CT scans |

Thyroid Masses

In everyday practice, enlarged substernal thyroid masses are the most frequently encountered anterior mediastinal mass. The vast majority of these masses are multinodular goiters, and the mass is called a substernal goiter or substernal thyroid or substernal thyroid goiter.

In everyday practice, enlarged substernal thyroid masses are the most frequently encountered anterior mediastinal mass. The vast majority of these masses are multinodular goiters, and the mass is called a substernal goiter or substernal thyroid or substernal thyroid goiter. On occasion, the isthmus or lower pole of either lobe of the thyroid may enlarge but project downward into the upper thorax rather than anteriorly into the neck.

On occasion, the isthmus or lower pole of either lobe of the thyroid may enlarge but project downward into the upper thorax rather than anteriorly into the neck.

Substernal goiters characteristically displace the trachea either to the left or right above the level of the aortic arch, a tendency the other anterior mediastinal masses do not typically demonstrate. Classically, substernal goiters do not extend below the top of the aortic arch (Fig. 12-2).

Substernal goiters characteristically displace the trachea either to the left or right above the level of the aortic arch, a tendency the other anterior mediastinal masses do not typically demonstrate. Classically, substernal goiters do not extend below the top of the aortic arch (Fig. 12-2).

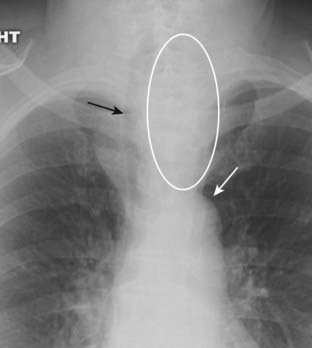

Figure 12-2 Substernal thyroid mass.

The lower pole of the thyroid may enlarge but project downward into the upper thorax (white oval) rather than anteriorly into the neck. Classically, substernal thyroid goiters produce mediastinal masses that do not extend below the top of the aortic arch (solid white arrow). Substernal goiters characteristically displace the trachea (solid black arrow) either to the left or right above the aortic knob, a tendency the other anterior mediastinal masses do not typically demonstrate. Therefore, you should think of an enlarged substernal thyroid goiter whenever you see an anterior mediastinal mass that displaces the trachea.

![]() Therefore, you should think of an enlarged substernal thyroid whenever you see an anterior mediastinal mass that displaces the trachea.

Therefore, you should think of an enlarged substernal thyroid whenever you see an anterior mediastinal mass that displaces the trachea.

Radioisotope thyroid scans are the study of choice in confirming the diagnosis of a substernal thyroid because virtually all goiters will display some uptake of the radioactive tracer that can be imaged and recorded with a special camera.

Radioisotope thyroid scans are the study of choice in confirming the diagnosis of a substernal thyroid because virtually all goiters will display some uptake of the radioactive tracer that can be imaged and recorded with a special camera. On CT scans, substernal thyroid masses are contiguous with the thyroid gland, frequently contain calcification, and avidly take up intravenous contrast but with a mottled, inhomogeneous appearance (Fig. 12-3).

On CT scans, substernal thyroid masses are contiguous with the thyroid gland, frequently contain calcification, and avidly take up intravenous contrast but with a mottled, inhomogeneous appearance (Fig. 12-3).

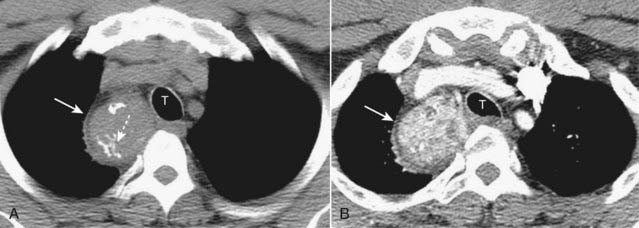

Figure 12-3 CT of a substernal thyroid goiter without and with contrast enhancement.

These are two images at the same level in a patient who was scanned both before (A) and then after intravenous contrast administration (B). A, On CT scans, substernal thyroid masses (solid white arrow) are contiguous with the thyroid gland, frequently contain calcification (dotted white arrow) and (B) avidly take up intravenous contrast but with a mottled, inhomogeneous appearance (solid white arrow). This mass is displacing the trachea (T) slightly to the left.

Lymphoma

Lymphadenopathy, whether from lymphoma, metastatic carcinoma, sarcoid, or tuberculosis, is the most common cause of a mediastinal mass overall.

Lymphadenopathy, whether from lymphoma, metastatic carcinoma, sarcoid, or tuberculosis, is the most common cause of a mediastinal mass overall. Anterior mediastinal lymphadenopathy is most common in Hodgkin disease, especially the nodular sclerosing variety.

Anterior mediastinal lymphadenopathy is most common in Hodgkin disease, especially the nodular sclerosing variety. Hodgkin disease is a malignancy of the lymph nodes, more common in females, which most often presents with painless, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck.

Hodgkin disease is a malignancy of the lymph nodes, more common in females, which most often presents with painless, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck. Unlike teratomas and thymomas, which are presumed to expand outward from a single abnormal cell, lymphomatous masses are frequently composed of several contiguously enlarged lymph nodes. As such, lymphadenopathy frequently presents with a border that is lobulated or polycyclic in contour owing to the conglomeration of enlarged nodes that make up the mass.

Unlike teratomas and thymomas, which are presumed to expand outward from a single abnormal cell, lymphomatous masses are frequently composed of several contiguously enlarged lymph nodes. As such, lymphadenopathy frequently presents with a border that is lobulated or polycyclic in contour owing to the conglomeration of enlarged nodes that make up the mass.

![]() On chest radiographs, this finding may help differentiate lymphadenopathy from other mediastinal masses.

On chest radiographs, this finding may help differentiate lymphadenopathy from other mediastinal masses.

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in Hodgkin disease is usually bilateral and asymmetrical (Fig. 12-4). In addition, asymmetrical hilar adenopathy is associated with mediastinal adenopathy in many patients with Hodgkin disease.

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in Hodgkin disease is usually bilateral and asymmetrical (Fig. 12-4). In addition, asymmetrical hilar adenopathy is associated with mediastinal adenopathy in many patients with Hodgkin disease. In general, mediastinal lymph nodes that exceed 1 cm measured along their short axis on CT scans of the chest are considered to be enlarged.

In general, mediastinal lymph nodes that exceed 1 cm measured along their short axis on CT scans of the chest are considered to be enlarged. Lymphoma will produce multiple, lobulated soft-tissue masses or one large soft-tissue mass from lymph node aggregation.

Lymphoma will produce multiple, lobulated soft-tissue masses or one large soft-tissue mass from lymph node aggregation. The mass is usually homogeneous in density on CT but may be heterogeneous when it achieves a sufficient size to undergo necrosis (areas of lower attenuation, i.e., blacker) or hemorrhage (areas of higher attenuation, i.e., whiter) (Fig. 12-5).

The mass is usually homogeneous in density on CT but may be heterogeneous when it achieves a sufficient size to undergo necrosis (areas of lower attenuation, i.e., blacker) or hemorrhage (areas of higher attenuation, i.e., whiter) (Fig. 12-5). Some findings of lymphoma may mimic those of sarcoid since both produce thoracic adenopathy. Table 12-3 helps to differentiate them.

Some findings of lymphoma may mimic those of sarcoid since both produce thoracic adenopathy. Table 12-3 helps to differentiate them.

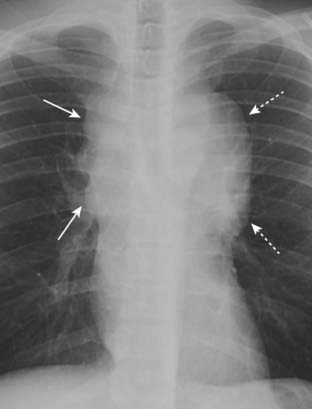

Figure 12-4 Mediastinal adenopathy from Hodgkin disease.

Lymphadenopathy frequently presents with a lobulated or polycyclic border due to the conglomeration of enlarged nodes that produce the mass (solid white arrows). This finding may help differentiate lymphadenopathy from other mediastinal masses. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in Hodgkin disease is usually bilateral (dotted white arrows) and frequently asymmetric.

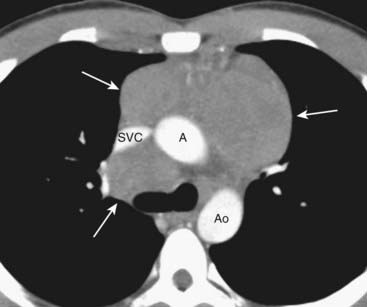

Figure 12-5 CT of anterior mediastinal adenopathy in Hodgkin disease.

On CT, lymphomas will produce multiple, lobulated soft-tissue masses or a large soft-tissue mass from lymph node aggregation (solid white arrows). The mass is usually homogeneous in density, as in this case, but may be heterogeneous when the nodes achieve a sufficient size to undergo necrosis (areas of low attenuation, i.e., blacker) or hemorrhage (areas of high attenuation, i.e., whiter). The superior vena cava (SVC) is compressed by the nodes while the ascending (A) and descending aorta (Ao) are typically less so.

TABLE 12-3 SARCOIDOSIS VS. LYMPHOMA

| Sarcoid | Lymphoma |

|---|---|

| Bilateral hilar and right paratracheal adenopathy classic combination | More often mediastinal adenopathy, associated with asymmetrical hilar enlargement |

| Bronchopulmonary nodes more peripheral | Hilar nodes more central |

| Pleural effusion in about 5% | Pleural effusion more common—in 30% |

| Anterior mediastinal adenopathy is uncommon | Anterior mediastinal adenopathy is common |

Thymic Masses

Normal thymic tissue can be visible on CT throughout life, although the gland begins to involute after age 20.

Normal thymic tissue can be visible on CT throughout life, although the gland begins to involute after age 20. Thymomas are neoplasms of thymic epithelium and lymphocytes. They occur most often in middle-aged adults, generally at an older age than those with teratomas. Most thymomas are benign.

Thymomas are neoplasms of thymic epithelium and lymphocytes. They occur most often in middle-aged adults, generally at an older age than those with teratomas. Most thymomas are benign.

![]() Thymomas are associated with myasthenia gravis about 35% of the time they are present. Conversely, about 15% of patients with clinical myasthenia gravis will be found to have a thymoma. The importance of identifying a thymoma in patients with myasthenia gravis lies in the favorable prognosis for patients with myasthenia after thymectomy.

Thymomas are associated with myasthenia gravis about 35% of the time they are present. Conversely, about 15% of patients with clinical myasthenia gravis will be found to have a thymoma. The importance of identifying a thymoma in patients with myasthenia gravis lies in the favorable prognosis for patients with myasthenia after thymectomy.

On CT scans, thymomas classically present as a smooth or lobulated mass that arises near the junction of the heart and great vessels, which, like a teratoma, may contain calcification (Fig. 12-6).

On CT scans, thymomas classically present as a smooth or lobulated mass that arises near the junction of the heart and great vessels, which, like a teratoma, may contain calcification (Fig. 12-6). Other lesions that can produce enlargement of the thymus include thymic cysts, thymic hyperplasia, thymic lymphoma, carcinoma, or lipoma.

Other lesions that can produce enlargement of the thymus include thymic cysts, thymic hyperplasia, thymic lymphoma, carcinoma, or lipoma.

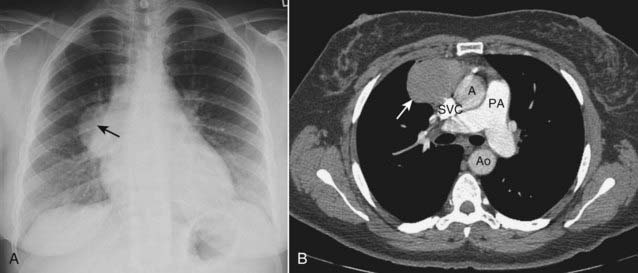

Figure 12-6 Thymoma, chest radiograph, and CT scan.

Thymomas are neoplasms of thymic epithelium and lymphocytes that occur most often in middle-aged adults, generally at an older age than those with teratomas. A, The chest radiograph shows a smoothly marginated anterior mediastinal mass (solid black arrow). B, Contrast-enhanced CT scan confirms the anterior mediastinal location and homogeneous density of the mass (solid white arrow). The patient had myasthenia gravis and improved following resection of the thymoma. (A = ascending aorta; Ao = descending aorta; PA = main pulmonary artery; SVC = superior vena cava.)

Teratoma

Teratomas are germinal tumors that typically contain all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). Most teratomas are benign and occur earlier in life than thymomas. Usually asymptomatic and discovered serendipitously, about 30% of mediastinal teratomas are malignant and have a poor prognosis.

Teratomas are germinal tumors that typically contain all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). Most teratomas are benign and occur earlier in life than thymomas. Usually asymptomatic and discovered serendipitously, about 30% of mediastinal teratomas are malignant and have a poor prognosis. The most common variety of teratoma is cystic; it produces a well-marginated mass near the origin of the great vessels that characteristically contains fat, cartilage, and possibly bone on CT examination (Fig. 12-7).

The most common variety of teratoma is cystic; it produces a well-marginated mass near the origin of the great vessels that characteristically contains fat, cartilage, and possibly bone on CT examination (Fig. 12-7).

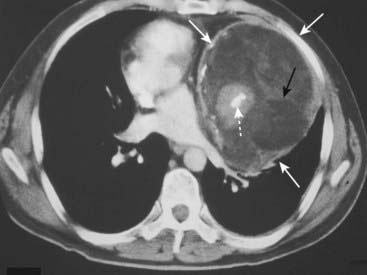

Figure 12-7 Mediastinal teratoma.

Teratomas are germinal tumors that typically contain all three germ layers. They tend to be discovered at a younger age than thymomas. The most common variety of teratoma is cystic, as in this case (solid white arrows). As shown here, they usually produce a well-marginated mass near the origin of the great vessels. On CT, they characteristically contain fat (solid black arrow), cartilage, and sometimes bone (dotted white arrow).

Middle Mediastinum

The middle mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the anterior border of the heart and aorta to the posterior border of the heart and contains the heart, the origins of the great vessels, trachea, and main bronchi along with lymph nodes (see Fig. 12-1).

The middle mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the anterior border of the heart and aorta to the posterior border of the heart and contains the heart, the origins of the great vessels, trachea, and main bronchi along with lymph nodes (see Fig. 12-1). Lymphadenopathy produces the most common mass in this compartment. While Hodgkin disease is the most likely cause of mediastinal adenopathy, other malignancies and several benign diseases can produce such findings.

Lymphadenopathy produces the most common mass in this compartment. While Hodgkin disease is the most likely cause of mediastinal adenopathy, other malignancies and several benign diseases can produce such findings.

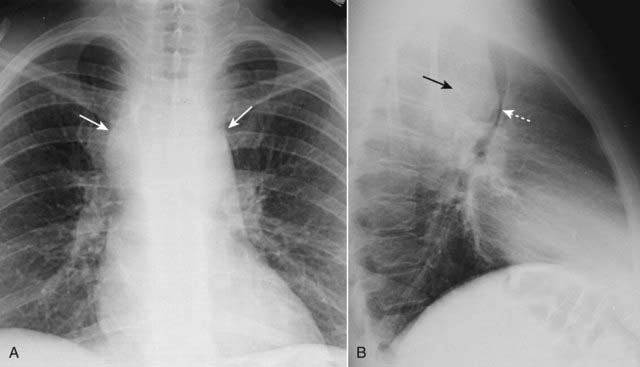

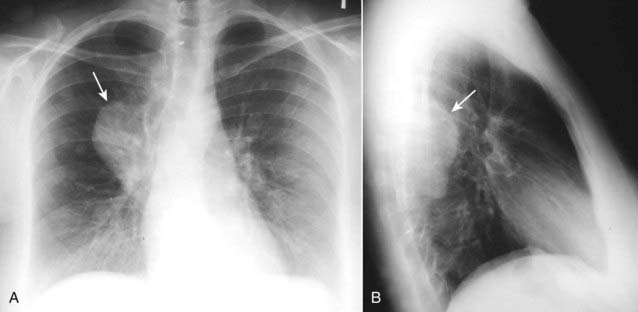

Figure 12-8 Middle mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

While lymphoma is the most likely cause of adenopathy in the middle mediastinum, other malignancies, such as small cell lung carcinoma and metastatic disease, as well as several benign diseases, can produce these findings. This patient has a mediastinal mass demonstrated on both the frontal (A) (solid white arrows) and lateral (B) views (solid black arrow). The mass is pushing the trachea forward (dotted white arrow) on the lateral view. The biopsied lymph nodes in this patient demonstrated small cell carcinoma of the lung.

Posterior Mediastinum

The posterior mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the posterior border of the heart to the anterior border of the vertebral column. For practical purposes, however, it is considered to extend to either side of the spine into the paravertebral gutters (see Fig. 12-1).

The posterior mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the posterior border of the heart to the anterior border of the vertebral column. For practical purposes, however, it is considered to extend to either side of the spine into the paravertebral gutters (see Fig. 12-1). It contains the descending aorta, esophagus, and lymph nodes and is the site of masses representing extramedullary hematopoiesis. Most importantly, it is the home of tumors of neural origin.

It contains the descending aorta, esophagus, and lymph nodes and is the site of masses representing extramedullary hematopoiesis. Most importantly, it is the home of tumors of neural origin.Neurogenic Tumors

Although neurogenic tumors produce the largest percentage of posterior mediastinal masses, none of these lesions is particularly common. Neurogenic tumors include such entities as neurofibroma, schwannoma (neurilemmoma), ganglioneuroma, and neuroblastoma.

Although neurogenic tumors produce the largest percentage of posterior mediastinal masses, none of these lesions is particularly common. Neurogenic tumors include such entities as neurofibroma, schwannoma (neurilemmoma), ganglioneuroma, and neuroblastoma. Nerve sheath tumors (Schwannoma or neurilemmoma) are the most common and are almost always benign. They usually affect persons 20-50 years of age. These slow-growing tumors may produce no symptoms until late in their course.

Nerve sheath tumors (Schwannoma or neurilemmoma) are the most common and are almost always benign. They usually affect persons 20-50 years of age. These slow-growing tumors may produce no symptoms until late in their course. Neoplasms that arise from nerve elements other than the sheath, such as ganglioneuromas and neuroblastoma, are usually malignant.

Neoplasms that arise from nerve elements other than the sheath, such as ganglioneuromas and neuroblastoma, are usually malignant. Neurogenic tumors will produce a soft tissue mass, usually sharply marginated, in the paravertebral gutter (Fig. 12-9). Both benign and malignant tumors may erode ribs (Fig. 12-10A). They may enlarge the neural foramina producing dumbbell-shaped lesions that arise from the spinal canal but project through the neural foramen into the mediastinum (Fig. 12-10B).

Neurogenic tumors will produce a soft tissue mass, usually sharply marginated, in the paravertebral gutter (Fig. 12-9). Both benign and malignant tumors may erode ribs (Fig. 12-10A). They may enlarge the neural foramina producing dumbbell-shaped lesions that arise from the spinal canal but project through the neural foramen into the mediastinum (Fig. 12-10B). Neurofibromas can occur as an isolated tumor arising from the Schwann cell of the nerve sheath or as part of a syndrome called neurofibromatosis. As part of the latter, they are a component of a neurocutaneous bone dysplasia that can cause numerous abnormalities, including subcutaneous nodules, erosion of adjacent bone (rib notching), scalloping of the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies (Fig. 12-11), absence of the sphenoid wings, pseudarthroses, and sharp-angled kyphoscoliosis at the thoracolumbar junction.

Neurofibromas can occur as an isolated tumor arising from the Schwann cell of the nerve sheath or as part of a syndrome called neurofibromatosis. As part of the latter, they are a component of a neurocutaneous bone dysplasia that can cause numerous abnormalities, including subcutaneous nodules, erosion of adjacent bone (rib notching), scalloping of the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies (Fig. 12-11), absence of the sphenoid wings, pseudarthroses, and sharp-angled kyphoscoliosis at the thoracolumbar junction.

Figure 12-9 Neurofibromatosis.

Neurofibromas can occur as an isolated tumor arising from the Schwann cell of the nerve sheath or as part of the syndrome neurofibromatosis, as in this case. There is a large, posterior mediastinal neurofibroma (solid white arrows) seen in the right, paravertebral gutter on the frontal (A) and lateral (B) views.

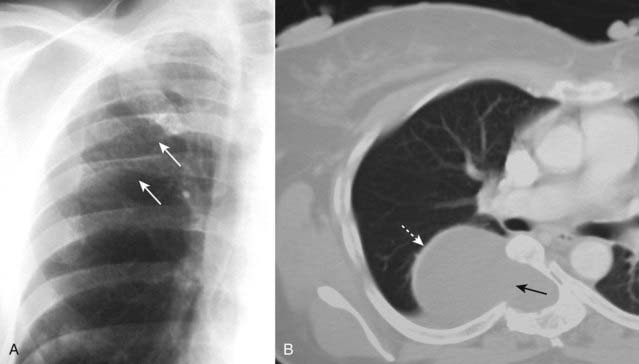

Figure 12-10 Rib-notching and a dumbbell-shaped neurofibroma.

A, Plexiform neurofibromas can produce erosions along the inferior borders of the ribs (where the intercostal nerves are located) and produce either notching or a wavy appearance called ribbon ribs (solid white arrows). B, Another patient demonstrates a large neurofibroma that is enlarging the neural foramen, eroding half of the vertebral body (solid black arrow) and producing a dumbbell-shaped lesion that arises from the spinal canal but projects through the foramen into the mediastinum (dotted white arrow).

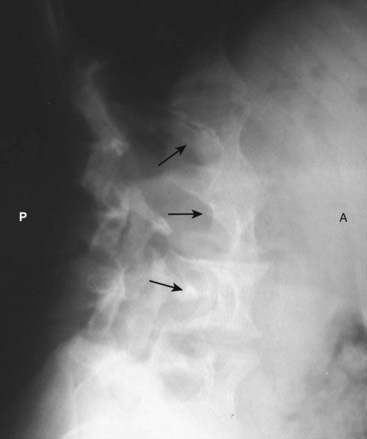

Figure 12-11 Scalloping of the vertebral bodies in neurofibromatosis.

Neurofibromatosis is a neurocutaneous disorder associated with a skeletal dysplasia. There may be numerous skeletal abnormalities associated with the disease, including scalloping of posterior vertebral bodies (solid black arrows), especially in the thoracic or lumbar spine (as shown here). This is produced by diverticula of the thecal sac caused by dysplasia of the meninges that leads to erosion of adjacent bone through the pulsations transmitted via the spinal fluid. (A is anterior and P is posterior.)

Solitary Nodule/Mass in the Lung

The difference between a nodule and a mass is size: under 3 cm, it is usually called a nodule; over 3 cm a mass.

The difference between a nodule and a mass is size: under 3 cm, it is usually called a nodule; over 3 cm a mass. Much has been written about the workup of a patient in whom a single nodular density is discovered in the lung on imaging of the thorax, i.e., the solitary pulmonary nodule. It is estimated that as many as 50% of smokers have a nodule discovered by chest CT, but fewer than 1% of the nodules < 5 mm in size show any malignant tendencies (growth or metastases) when followed for 2 years.

Much has been written about the workup of a patient in whom a single nodular density is discovered in the lung on imaging of the thorax, i.e., the solitary pulmonary nodule. It is estimated that as many as 50% of smokers have a nodule discovered by chest CT, but fewer than 1% of the nodules < 5 mm in size show any malignant tendencies (growth or metastases) when followed for 2 years. In evaluating a solitary pulmonary nodule, the critical question to be answered is whether the nodule is most likely benign or malignant.

In evaluating a solitary pulmonary nodule, the critical question to be answered is whether the nodule is most likely benign or malignant.

The answer to the question of benign versus malignant will depend on many factors, including the availability of prior imaging studies which can help greatly in establishing stability of a lesion over time.

The answer to the question of benign versus malignant will depend on many factors, including the availability of prior imaging studies which can help greatly in establishing stability of a lesion over time. In 2005, an international society of chest radiologists (Fleischner Society) approved a set of evidence-based criteria setting guidelines for the follow-up of noncalcified nodules found incidentally during chest CT (Table 12-4).

In 2005, an international society of chest radiologists (Fleischner Society) approved a set of evidence-based criteria setting guidelines for the follow-up of noncalcified nodules found incidentally during chest CT (Table 12-4).TABLE 12-4 FLEISCHNER SOCIETY CRITERIA FOR FOLLOW-UP OF INCIDENTAL, NONCALCIFIED SOLITARY PULMONARY NODULES

| Nodule Size (mm) | Low-Risk Patients* | High-Risk Patients** |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 4 | No follow-up needed | Follow-up at 12 months; if no change, no further imaging needed |

| > 4-6 | Follow-up at 12 months; if no change, no further imaging needed | Initial follow-up CT at 6-12 months and then at 18-24 months if no change |

| > 6-8 | Initial follow-up CT at 6-12 months and then at 18-24 months if no change | Initial follow-up CT at 3-6 months and then at 9-12 and 24 months if no change |

| > 8 | Follow-up CTs at around 3, 9, and 24 months; dynamic contrast-enhanced CT, PET, and/or biopsy | Same as for low-risk patients |

* Low-risk patients: Minimal or absent history of smoking and of other known risk factors (e.g., radon exposure).

** High-risk patients: History of smoking or of other known risk factors.

Signs of a Benign Versus Malignant Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

Size of the lesion. Nodules less than 4 mm rarely show malignant behavior. Masses larger than 5 cm have a 95% chance of malignancy (Fig. 12-12).

Size of the lesion. Nodules less than 4 mm rarely show malignant behavior. Masses larger than 5 cm have a 95% chance of malignancy (Fig. 12-12). Calcification. The presence of calcification is usually determined by CT. Lesions containing central, laminar, or diffuse patterns of calcification are invariably benign.

Calcification. The presence of calcification is usually determined by CT. Lesions containing central, laminar, or diffuse patterns of calcification are invariably benign. Change in size over time. This requires a previous study or sufficient confidence so that a follow-up study will provide a basis of comparison of size over time. Malignancies tend to increase in size at a rate that is not so brief as to suggest an inflammatory etiology (changes in weeks) nor so prolonged as to suggest benignity (no change over a year or more).

Change in size over time. This requires a previous study or sufficient confidence so that a follow-up study will provide a basis of comparison of size over time. Malignancies tend to increase in size at a rate that is not so brief as to suggest an inflammatory etiology (changes in weeks) nor so prolonged as to suggest benignity (no change over a year or more).

When clinical signs or symptoms are present, the chance of malignancy rises. Solitary pulmonary nodules that are surgically removed (clinical signs or symptoms and imaging findings suggested malignancy) are malignant 50% of the time in men over the age of 50.

When clinical signs or symptoms are present, the chance of malignancy rises. Solitary pulmonary nodules that are surgically removed (clinical signs or symptoms and imaging findings suggested malignancy) are malignant 50% of the time in men over the age of 50.

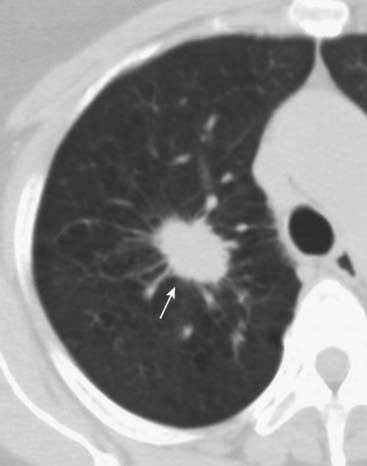

Figure 12-12 Solitary pulmonary nodule, conventional radiograph (A) and CT (B).

A 1.8 cm nodule is seen in the right upper lobe (solid and dotted white arrows) in this 53-year-old male with an episode of hemoptysis. The critical question to be answered in evaluating any solitary pulmonary nodule is whether the lesion is benign or malignant. The answer to the question will depend on many factors, including the lesion’s size and availability of prior imaging studies, which can help greatly in establishing growth of a lesion over time. A PET scan in a lesion of this size might help in indicating if the nodule is benign or not. This patient had a biopsy that revealed an adenocarcinoma of the lung.

Benign Causes of Solitary Pulmonary Nodules

Granulomas. Tuberculosis and histoplasmosis usually produce calcified nodules < 1 cm in size, although tuberculomas and histoplasmomas can reach up to 4 cm.

Granulomas. Tuberculosis and histoplasmosis usually produce calcified nodules < 1 cm in size, although tuberculomas and histoplasmomas can reach up to 4 cm.

Hamartomas. Peripherally located lung tumors of disorganized lung tissue that characteristically contain fat and calcification on CT scan. The classical calcification of a hamartoma is called popcorn calcification (Fig. 12-15).

Hamartomas. Peripherally located lung tumors of disorganized lung tissue that characteristically contain fat and calcification on CT scan. The classical calcification of a hamartoma is called popcorn calcification (Fig. 12-15). Other uncommon benign lesions that can produce solitary pulmonary nodules include rheumatoid nodules, fungal diseases such as nocardiosis, arteriovenous malformations, and granulomatous vasculitis (Wegener granulomatosis).

Other uncommon benign lesions that can produce solitary pulmonary nodules include rheumatoid nodules, fungal diseases such as nocardiosis, arteriovenous malformations, and granulomatous vasculitis (Wegener granulomatosis). Round atelectasis may mimic a solitary pulmonary nodule and is discussed in Chapter 5, Recognizing Atelectasis.

Round atelectasis may mimic a solitary pulmonary nodule and is discussed in Chapter 5, Recognizing Atelectasis.

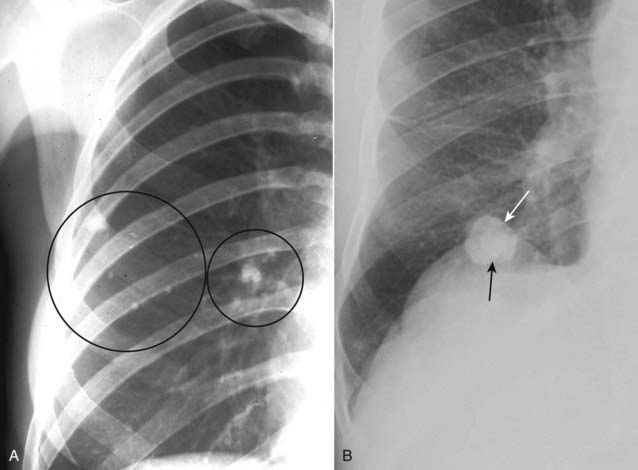

Figure 12-14 Calcified tuberculous granulomas and histoplasmoma.

When a pulmonary nodule is heavily calcified, it is almost always benign. A, Tuberculous granulomas are common sequelae of prior, usually subclinical, tuberculous infection and are usually homogeneously calcified (black circles). B, Histoplasmomas (solid white arrow) may contain a central or “target” calcification (solid black arrow) or may have a laminated calcification, which is diagnostic. CT can be used to differentiate between a calcified and a noncalcified pulmonary nodule with greater sensitivity than conventional radiographs.

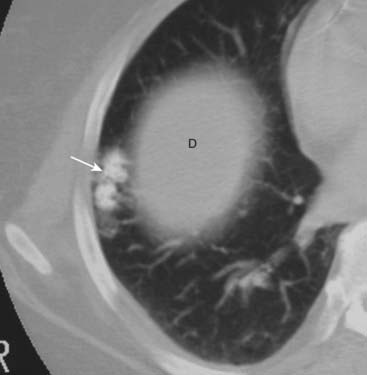

Figure 12-15 Hamartoma of the lung.

Hamartomas of the lung are peripherally located tumors of disorganized lung tissue that classically contain fat and calcification on CT scans. The classical calcification of a hamartoma is called popcorn calcification (solid white arrow). The small island of soft tissue in the middle of the right lung (D) is the uppermost part of the right hemidiaphragm.

Bronchogenic Carcinoma

In the United States, lung cancer is the most common fatal malignancy in men and the second most common in women (next to breast cancer).

In the United States, lung cancer is the most common fatal malignancy in men and the second most common in women (next to breast cancer). The number of nodules in the lung can help direct the further work-up. Primary lung cancer usually presents as a solitary nodule, while metastatic disease to the lung from another organ characteristically produces multiple nodules.

The number of nodules in the lung can help direct the further work-up. Primary lung cancer usually presents as a solitary nodule, while metastatic disease to the lung from another organ characteristically produces multiple nodules. Table 12-5 summarizes the classical manifestations and growth tendencies of the four types of bronchogenic carcinoma by cell type.

Table 12-5 summarizes the classical manifestations and growth tendencies of the four types of bronchogenic carcinoma by cell type. Recognizing bronchogenic carcinomas

Recognizing bronchogenic carcinomas

TABLE 12-5 CARCINOMA OF THE LUNG: CELL TYPES

| Cell Type | Graphic Representation | Classical Manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Primarily central in location Arise in segmental or lobar bronchi Invariably produce bronchial obstruction leading to obstructive pneumonitis or atelectasis Tend to grow rapidly |

|

| Adenocarcinoma, including bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma | Primarily peripheral in location Usually solitary except in the case of diffuse bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma, which can present as multiple nodules Slowest growing |

|

| Small cell, including oat cell carcinoma | Primarily central in location May contain neurosecretory granules that lead to an association of small cell carcinoma with paraneoplastic syndromes such as Cushing syndrome, inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone |

|

| Large cell carcinoma | Diagnosis of exclusion for lesions that are nonsmall cell and not squamous or adenocarcinoma Larger peripheral lesions Grow extremely rapidly |

Bronchogenic Carcinomas Presenting as a Nodule/Mass in the Lung

It may cavitate, more often if it is of squamous cell origin (although cavitation also occurs with adenocarcinoma), producing a relatively thick-walled cavity with a nodular and irregular inner margin (Fig. 12-16).

It may cavitate, more often if it is of squamous cell origin (although cavitation also occurs with adenocarcinoma), producing a relatively thick-walled cavity with a nodular and irregular inner margin (Fig. 12-16).

Figure 12-16 Cavitary bronchogenic carcinoma.

A large, cavitating neoplasm with a thick wall (solid white arrow) is present in the right upper lobe. The outer margin of the lesion is spiculated. The internal contour of the cavity is nodular (solid black arrows). These features point toward a cavitating malignancy. This was a squamous cell carcinoma.

Bronchogenic Carcinoma Presenting with Bronchial Obstruction

Bronchial obstruction is most often caused by a squamous cell carcinoma. Endobronchial lesions produce varying degrees of bronchial obstruction, which can lead to pneumonitis or atelectasis.

Bronchial obstruction is most often caused by a squamous cell carcinoma. Endobronchial lesions produce varying degrees of bronchial obstruction, which can lead to pneumonitis or atelectasis.Bronchogenic Carcinoma Presenting with Direct Extension or Metastatic Lesions

Rib destruction by direct extension. Pancoast tumor is the eponym for a tumor arising from the superior sulcus of the lung, frequently producing destruction of one or more of the first three ribs on the affected side (Box 12-1; Fig. 12-17).

Rib destruction by direct extension. Pancoast tumor is the eponym for a tumor arising from the superior sulcus of the lung, frequently producing destruction of one or more of the first three ribs on the affected side (Box 12-1; Fig. 12-17). Mediastinal adenopathy. May be the sole manifestation of a small cell carcinoma, the peripheral lung nodule being invisible (see Fig. 12-8).

Mediastinal adenopathy. May be the sole manifestation of a small cell carcinoma, the peripheral lung nodule being invisible (see Fig. 12-8). Other nodules in the lung. One of the manifestations of diffuse bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma may be multiple nodules throughout both lungs and, as such, may mimic metastatic disease.

Other nodules in the lung. One of the manifestations of diffuse bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma may be multiple nodules throughout both lungs and, as such, may mimic metastatic disease. Pleural effusion. Frequently, there is associated lymphangitic spread of tumor when there is a pleural effusion.

Pleural effusion. Frequently, there is associated lymphangitic spread of tumor when there is a pleural effusion.

Figure 12-17 Pancoast tumor, right upper lobe.

A large, soft tissue mass is seen in the apex of the right lung (solid white arrow). It is associated with rib destruction (solid black arrow). On the normal left side, the ribs are intact (dotted white arrow). The finding of an apical soft tissue mass with associated rib destruction is classical for a Pancoast or superior sulcus tumor.

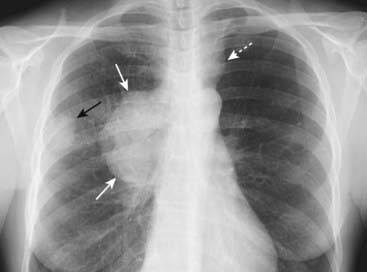

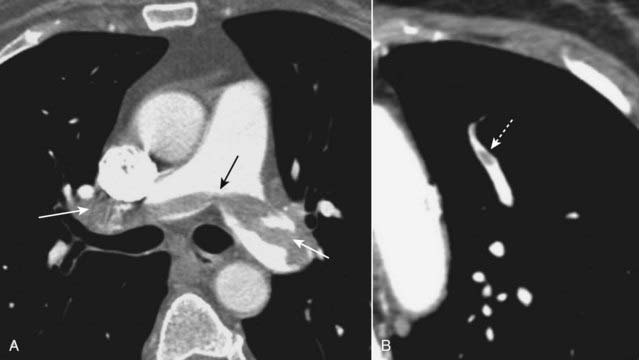

Figure 12-18 Bronchogenic carcinoma with hilar and mediastinal adenopathy.

A peripheral lung mass (solid black arrow) shows evidence of ipsilateral hilar and mediastinal adenopathy (solid white arrows) and contralateral mediastinal adenopathy (dotted white arrow). Bronchogenic carcinoma may present with metastatic lesions that can manifest in distant organs or in the thorax itself. This was an adenocarcinoma of the lung.

Metastatic Neoplasms In The Lung

Multiple Nodules

Multiple nodules in the lung are most often metastatic lesions that have traveled through the bloodstream from a distant primary (hematogenous spread). Multiple metastatic nodules are usually of slightly differing sizes indicating tumor embolization that occurred at different times.

Multiple nodules in the lung are most often metastatic lesions that have traveled through the bloodstream from a distant primary (hematogenous spread). Multiple metastatic nodules are usually of slightly differing sizes indicating tumor embolization that occurred at different times. They are frequently sharply marginated, varying in size from micronodular to “cannonball” masses (see Fig. 3-15A).

They are frequently sharply marginated, varying in size from micronodular to “cannonball” masses (see Fig. 3-15A). For all practical purposes it is impossible to determine the primary site by the appearance of the metastatic nodules, i.e., all metastatic nodules appear similar.

For all practical purposes it is impossible to determine the primary site by the appearance of the metastatic nodules, i.e., all metastatic nodules appear similar. Tissue sampling, whether by bronchoscopic or percutaneous biopsy, is the best means of determining the organ of origin of the metastatic nodule.

Tissue sampling, whether by bronchoscopic or percutaneous biopsy, is the best means of determining the organ of origin of the metastatic nodule. Table 12-6 summarizes the primary malignancies most likely to metastasize to the lung hematogenously.

Table 12-6 summarizes the primary malignancies most likely to metastasize to the lung hematogenously.TABLE 12-6 SOME COMMON PRIMARY SITES OF METASTATIC LUNG NODULES

| Males | Females |

|---|---|

| Colorectal carcinoma | Breast cancer |

| Renal cell carcinoma | Colorectal carcinoma |

| Head and neck tumors | Renal cell carcinoma |

| Testicular and bladder carcinoma | Cervical or endometrial carcinoma |

| Malignant melanoma | Malignant melanoma |

| Sarcomas | Sarcomas |

Lymphangitic Spread of Carcinoma

In lymphangitic spread of carcinoma, a tumor grows in and obstructs lymphatics in the lung, producing a pattern that is radiologically similar to pulmonary interstitial edema from heart failure including Kerley B lines, thickening of the fissures, and pleural effusions.

In lymphangitic spread of carcinoma, a tumor grows in and obstructs lymphatics in the lung, producing a pattern that is radiologically similar to pulmonary interstitial edema from heart failure including Kerley B lines, thickening of the fissures, and pleural effusions.

![]() The findings may be unilateral or may involve only one lobe, which should alert you to suspect the possibility of lymphangitic spread rather than congestive heart failure, which is usually bilateral (Fig. 12-19).

The findings may be unilateral or may involve only one lobe, which should alert you to suspect the possibility of lymphangitic spread rather than congestive heart failure, which is usually bilateral (Fig. 12-19).

The most common primary malignancies to produce lymphangitic spread to the lung are those that arise around the thorax: breast, lung, and pancreatic carcinoma.

The most common primary malignancies to produce lymphangitic spread to the lung are those that arise around the thorax: breast, lung, and pancreatic carcinoma.

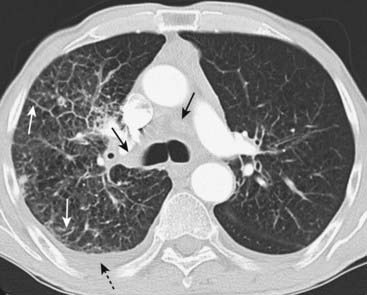

Figure 12-19 Bronchogenic carcinoma with lymphangitic spread of tumor.

In lymphangitic spread of carcinoma, a tumor grows in and obstructs lymphatics in the lung producing a pattern that is radiologically similar to pulmonary interstitial edema from heart failure. The findings may be unilateral, as in this case, which should alert you to the possibility of lymphangitic spread rather than congestive heart failure. There is extensive hilar and mediastinal adenopathy (solid black arrows) from a carcinoma of the lung. The interstitial markings are prominent in the right lung compared to the left, and there are thickened septal lines (Kerley B lines) present (solid white arrows) along with a right pleural effusion (dotted black arrow).

Pulmonary Thromboembolic Disease

Over 90% of pulmonary emboli develop from thrombi in the deep veins of the leg, especially above the level of the popliteal veins. They are usually a complication of surgery or prolonged bed rest or cancer. Because of the dual circulation of the lungs (pulmonary and bronchial), most pulmonary emboli do not result in infarction.

Over 90% of pulmonary emboli develop from thrombi in the deep veins of the leg, especially above the level of the popliteal veins. They are usually a complication of surgery or prolonged bed rest or cancer. Because of the dual circulation of the lungs (pulmonary and bronchial), most pulmonary emboli do not result in infarction. Although conventional chest radiographs are frequently abnormal in patients with pulmonary embolus (PE), they demonstrate nonspecific findings, such as subsegmental atelectasis, small pleural effusions, or elevation of the hemidiaphragm. Conventional chest radiography has a high false-negative rate in detecting PE.

Although conventional chest radiographs are frequently abnormal in patients with pulmonary embolus (PE), they demonstrate nonspecific findings, such as subsegmental atelectasis, small pleural effusions, or elevation of the hemidiaphragm. Conventional chest radiography has a high false-negative rate in detecting PE. If the chest radiograph is normal, a nuclear medicine ventilation-perfusion scan (V/Q scan) may be diagnostic. If, however, the chest radiograph is abnormal, CT is usually performed.

If the chest radiograph is normal, a nuclear medicine ventilation-perfusion scan (V/Q scan) may be diagnostic. If, however, the chest radiograph is abnormal, CT is usually performed. CT pulmonary angiography (CT-PA) is made possible by the fast data acquisition of spiral CT scanners (one breath hold) combined with thin slices and rapid bolus intravenous injection of iodinated contrast that produce maximal opacification of the pulmonary arteries with little or no motion artifact.

CT pulmonary angiography (CT-PA) is made possible by the fast data acquisition of spiral CT scanners (one breath hold) combined with thin slices and rapid bolus intravenous injection of iodinated contrast that produce maximal opacification of the pulmonary arteries with little or no motion artifact. Another benefit of CT-PA studies is the ability to acquire images of the veins of the pelvis and legs by obtaining slightly delayed images following the pulmonary arterial phase of the study. In this way, a deep venous thrombus may be detected even if the pulmonary portion of the angiogram is nondiagnostic.

Another benefit of CT-PA studies is the ability to acquire images of the veins of the pelvis and legs by obtaining slightly delayed images following the pulmonary arterial phase of the study. In this way, a deep venous thrombus may be detected even if the pulmonary portion of the angiogram is nondiagnostic. CT-PA has a sensitivity in excess of 90% and has replaced the use of V/Q scans in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or a positive chest radiograph in whom a V/Q scan is known to be less sensitive.

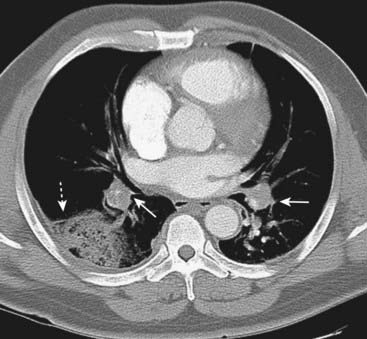

CT-PA has a sensitivity in excess of 90% and has replaced the use of V/Q scans in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or a positive chest radiograph in whom a V/Q scan is known to be less sensitive. On CT-PA, acute pulmonary emboli appear as partial- or complete-filling defects centrally located within the contrast-enhanced lumina of the pulmonary arteries (Fig. 12-21).

On CT-PA, acute pulmonary emboli appear as partial- or complete-filling defects centrally located within the contrast-enhanced lumina of the pulmonary arteries (Fig. 12-21). CT-PA has the additional benefit of demonstrating other diseases that may be present, such as pneumonia, even if the study is negative for PE.

CT-PA has the additional benefit of demonstrating other diseases that may be present, such as pneumonia, even if the study is negative for PE.

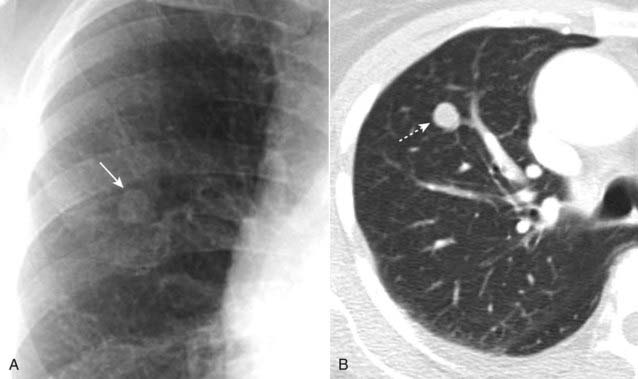

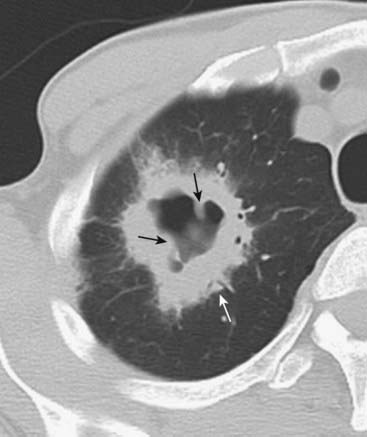

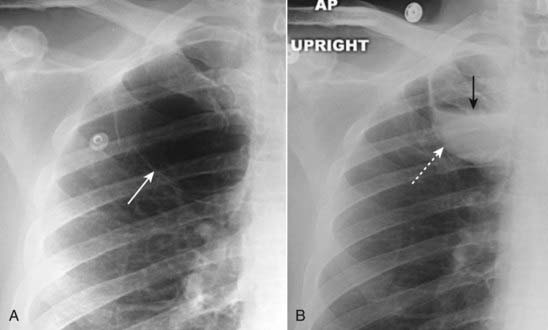

There is a wedge-shaped, peripheral air-space density present (dotted white arrow) associated with filling defects in both the left and right pulmonary arteries (solid white arrows). The wedge-shaped infarct is called a Hampton hump. Without the associated emboli present, the pleural-based airspace disease could have a differential diagnosis that includes pneumonia, lung contusion, or aspiration.

Figure 12-21 Saddle and peripheral pulmonary emboli.

Acute pulmonary emboli appear as partial or complete filling defects centrally located within the contrast-enhanced lumina of the pulmonary arteries. A, A large pulmonary embolus almost completely fills both the left and right pulmonary arteries (solid white and black arrows). This is a saddle embolus. B, A small, central filling defect is seen in a more peripheral pulmonary artery (dotted white arrow). This pulmonary artery seems to be floating disconnected in the lung because the plane of this particular image does not display its connection to the left pulmonary artery.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) is defined as a disease of airflow obstruction due to chronic bronchitis or emphysema.

Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) is defined as a disease of airflow obstruction due to chronic bronchitis or emphysema. Chronic bronchitis is defined clinically by productive cough, whereas emphysema is defined pathologically by the presence of permanent and abnormal enlargement and destruction of the air spaces distal to the terminal bronchioles.

Chronic bronchitis is defined clinically by productive cough, whereas emphysema is defined pathologically by the presence of permanent and abnormal enlargement and destruction of the air spaces distal to the terminal bronchioles. Emphysema has three pathologic patterns:

Emphysema has three pathologic patterns:

On conventional radiographs, the most reliable finding of COPD is hyperinflation, including flattening of the diaphragm, especially on the lateral exposure (Fig. 12-23). Other findings may include an increase in the retrosternal clear space, hyperlucency of the lungs with fewer than normal vascular markings visible, and prominence of the pulmonary arteries from pulmonary arterial hypertension.

On conventional radiographs, the most reliable finding of COPD is hyperinflation, including flattening of the diaphragm, especially on the lateral exposure (Fig. 12-23). Other findings may include an increase in the retrosternal clear space, hyperlucency of the lungs with fewer than normal vascular markings visible, and prominence of the pulmonary arteries from pulmonary arterial hypertension. With CT, findings of COPD may include focal areas of low density in which the cystic areas lack visible walls except where bounded by interlobular septa. CT is helpful in evaluating the extent of emphysematous disease and in planning for surgical procedures designed to remove bullae to reduce lung volume.

With CT, findings of COPD may include focal areas of low density in which the cystic areas lack visible walls except where bounded by interlobular septa. CT is helpful in evaluating the extent of emphysematous disease and in planning for surgical procedures designed to remove bullae to reduce lung volume.

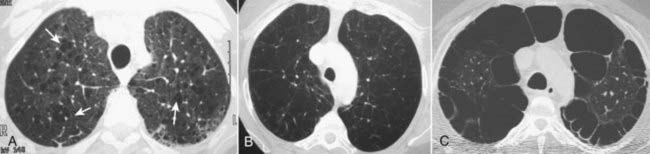

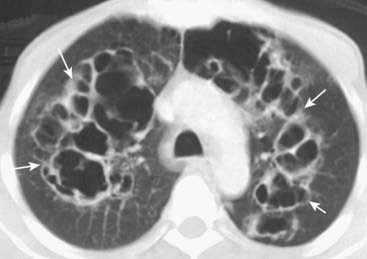

Figure 12-22 Types of emphysema.

A, Centriacinar (centrilobular) emphysema features focal destruction limited to the respiratory bronchioles and the central portions of the acinus (solid white arrows). It is associated with cigarette smoking and is most severe in the upper lobes. B, Panacinar (panlobular) emphysema involves the entire alveolus distal to the terminal bronchiole, is most severe in the lower lung zones, and generally develops in patients with homozygous alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. C, Paraseptal emphysema is the least common form, involves distal airway structures, alveolar ducts, and sacs, tends to be subpleural, and may cause pneumothorax.

On conventional radiographs, the imaging findings of COPD are hyperinflation, including flattening of the diaphragm, especially on the lateral exposure (solid white arrow in B), increase in the retrosternal clear space (dotted white arrow), hyperlucency of the lungs with fewer than normal vascular markings, and prominence of the pulmonary arteries secondary to pulmonary arterial hypertension (solid white arrows in A).

Blebs And Bullae, Cysts And Cavities

Blebs, bullae (singular: bulla), cysts, and cavities are all air-containing lesions in the lung of differing size, location, and wall composition.

Blebs, bullae (singular: bulla), cysts, and cavities are all air-containing lesions in the lung of differing size, location, and wall composition. Almost any of these lesions can contain fluid instead of, or in addition to, air.

Almost any of these lesions can contain fluid instead of, or in addition to, air.

A, Several thin-walled, but air-containing, bullae are shown in the right upper lobe (solid white arrow). B, Several weeks later, one of the bullae (dotted white arrow) contains both fluid and air (solid black arrow). Bullae normally contain air but can become partially or completely fluid-filled from infection or hemorrhage.

Bullae

Bullae measure more than 1 cm in size. They are usually associated with emphysema. They occur in the lung parenchyma and have a very thin wall (<1 mm) that is frequently only partially visible on conventional radiography but well seen on CT (Fig. 12-25).

Bullae measure more than 1 cm in size. They are usually associated with emphysema. They occur in the lung parenchyma and have a very thin wall (<1 mm) that is frequently only partially visible on conventional radiography but well seen on CT (Fig. 12-25).

They can grow to fill the entire hemithorax and compress the lung to such an extent on the affected side that it seems to disappear (vanishing lung syndrome).

They can grow to fill the entire hemithorax and compress the lung to such an extent on the affected side that it seems to disappear (vanishing lung syndrome).

Bullae measure more than 1 cm in size. They have a very thin wall that is often only partially visible on conventional radiography. CT demonstrates them more easily (solid white arrows). Characteristically, they contain no blood vessels but septae may appear to traverse the bulla. On conventional radiographs their presence is often inferred by a localized paucity of lung markings (see Fig. 12-24A).

Cysts

Cysts are either congenital or acquired. They can occur in either the lung parenchyma or the mediastinum. They have a thin wall that is usually thicker than that of a bulla (<3 mm).

Cysts are either congenital or acquired. They can occur in either the lung parenchyma or the mediastinum. They have a thin wall that is usually thicker than that of a bulla (<3 mm).

Figure 12-26 Cysts (pneumatocoeles) in Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP).

Cysts are visible on chest radiographs in 10% of patients with PCP and far more frequently with CT scans (up to 1 in 3 patients). Cysts may occur in the acute or in the postinfective phase of the disease. They have a predilection for the upper lobes and are commonly multiple (solid white arrows). Their etiology is unclear.

Cavities

Cavities can vary in size from a few millimeters to many centimeters. They occur in the lung parenchyma and usually result from a process that produces necrosis of the central portion of the lesion.

Cavities can vary in size from a few millimeters to many centimeters. They occur in the lung parenchyma and usually result from a process that produces necrosis of the central portion of the lesion. Cavities usually have the thickest wall of any of these four air-containing lesions with a wall thickness from 3 mm to several cm (see Fig. 12-16).

Cavities usually have the thickest wall of any of these four air-containing lesions with a wall thickness from 3 mm to several cm (see Fig. 12-16). Differentiation between three of the most frequent causes of cavities (carcinoma, pyogenic abscess, and tuberculosis) is summarized in Table 12-7 (Fig. 12-27).

Differentiation between three of the most frequent causes of cavities (carcinoma, pyogenic abscess, and tuberculosis) is summarized in Table 12-7 (Fig. 12-27).TABLE 12-7 DIFFERENTIATING THREE CAVITATING LUNG LESIONS

| Lesion | Thickness of the Cavity Wall | Inner Margin of Cavity |

|---|---|---|

| Bronchogenic carcinoma (Fig. 12-27A) | Thick* | Nodular |

| Tuberculosis (Fig. 12-27B) | Thin | Smooth |

| Lung abscess (Fig. 12-27C) | Thick | Smooth |

* Thick = more than 5 mm; thin = less than 5 mm.

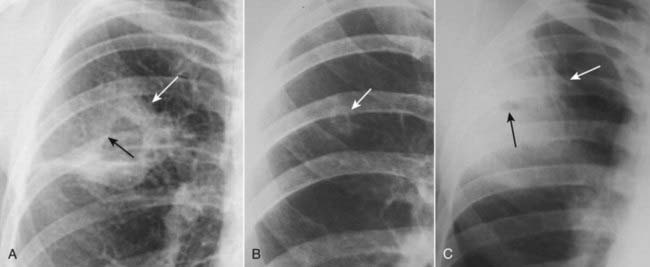

Figure 12-27 Cavitary lesions of the lung.

Three of the most common cavitary lesions of the lung can frequently be differentiated from each other by noting the thickness of the wall of the cavity and the smoothness or nodularity of its inner margin. A, Squamous cell bronchogenic carcinoma produces a cavity with a thick wall (solid white arrow) and a nodular interior margin (solid black arrow). B, Tuberculosis usually produces a relatively thin-walled, upper lobe cavity with a smooth inner margin (solid white arrow). C, A staphylococcal lung abscess demonstrates a characteristically thickened wall (solid white arrow), which in this case has a very small cavity with a smooth inner margin (solid black arrow).

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is defined as localized irreversible dilatation of part of the bronchial tree. Although it can be associated with many other diseases, it is usually caused by necrotizing bacterial infections, like those of Staphylococcus and Klebsiella, and it usually affects the lower lobes.

Bronchiectasis is defined as localized irreversible dilatation of part of the bronchial tree. Although it can be associated with many other diseases, it is usually caused by necrotizing bacterial infections, like those of Staphylococcus and Klebsiella, and it usually affects the lower lobes.

Conventional radiographs may demonstrate findings suggestive of the disease but are usually not specific.

Conventional radiographs may demonstrate findings suggestive of the disease but are usually not specific.

Figure 12-28 Bronchiectasis in cystic fibrosis.

Conventional radiographs may demonstrate parallel line opacities called tram tracks due to thickened walls of dilated bronchi (solid black arrows) and cystic lesions as large as 2 cm in diameter due to cystic bronchiectasis (solid white arrows). Bilateral upper lobe bronchiectasis in children is highly suggestive of cystic fibrosis.

CT is the study of choice in diagnosing bronchiectasis. A, The hallmark lesion is the signet-ring sign in which the bronchus with a thickened wall (solid white arrow) becomes larger than its associated pulmonary artery (dotted white arrow); this is the opposite of the normal relationship between the two. B, The bronchus may also show tram-tracking, thickened walls, and a failure to taper normally (solid white arrows).

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Diseases of the Chest on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Diseases of the Chest

The mediastinum lies in the central portion of the thorax between the two lungs and is arbitrarily divided into anterior, middle, and posterior compartments.

Masses in the anterior mediastinum include substernal thyroid goiters, lymphoma, thymoma, and teratoma.

The middle mediastinum is home primarily to lymphadenopathy from lymphoma and metastatic disease, such as from small cell carcinoma of the lung.

The posterior mediastinum is the location of neurogenic tumors, which originate either from the nerve sheath (mostly benign) or tissues other than the sheath (mostly malignant).

Incidental solitary pulmonary nodules (SPNs) less than 4 mm in size are rarely malignant; when clinical or imaging findings suggest malignancy, 50% of SPNs in men over the age of 50 are malignant. The key question is to determine whether a nodule is most likely benign or most likely malignant in any given individual.

Criteria on which an evaluation of benignity can be made include absolute size of the nodule upon discovery, presence of calcification within it, the margin of the nodule, and the change in the size of the nodule over time.

Bronchogenic carcinomas present in one of three ways: visualizing the tumor itself; recognizing the effects of bronchial obstruction such as pneumonitis and/or atelectasis; or recognizing the results of either their direct extension or metastatic spread to the chest or to distant organs.

Bronchogenic carcinomas presenting as a solitary nodule/mass in the lung are most often adenocarcinomas; bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma is a subset of adenocarcinoma that may present with multiple nodules, mimicking metastatic disease.

Bronchogenic carcinoma presenting with bronchial obstruction is most often due to squamous cell carcinoma; squamous cell carcinomas are most likely to cavitate.

Small cell carcinomas are highly aggressive, centrally located, peribronchial tumors, the majority of which have already metastasized at the time of initial presentation; they can be associated with paraneoplastic syndromes such as inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone and Cushing syndrome.

Multiple nodules in the lung are most often metastatic lesions that have traveled through the bloodstream from a distant primary (hematogenous spread); common sites of primaries for such metastases include colorectal, breast, renal cell, head and neck, bladder, uterine and cervical, soft tissue sarcomas, and melanoma.

In lymphangitic spread of carcinoma, a tumor grows in and obstructs lymphatics in the lung producing a pattern that is radiologically similar to pulmonary interstitial edema; primaries that metastasize to the lung in this fashion include breast, lung, and pancreatic cancer.

Conventional radiography has a high false negative rate in pulmonary thromboembolic disease because demonstration of “classic” findings such as Hampton hump, Westermark sign, and the knuckle sign is infrequent.

CT-pulmonary angiography (CT-PA) is now widely used for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism producing images of the pulmonary arteries with little or no motion artifact.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) consists of emphysema and chronic bronchitis; of the two, chronic bronchitis is a clinical diagnosis while emphysema is defined pathologically and has findings that can be seen on both conventional radiographs and CT scans.

Blebs, bullae, cysts, and cavities are all air-containing lesions in the lung that differ in size, location, and wall composition; bullae, cysts, and cavities are seen on CT and may also be seen on conventional radiographs.

Although bronchiectasis may be seen on conventional radiographs, CT is the study of choice demonstrating tram-tracks, cystic lesions, or tubular densities.