Chapter 18 Recognizing Gastrointestinal, Hepatic, and Urinary Tract Abnormalities

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to recognize some of the most common abnormalities of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the esophagus to the rectum. We’ll also discuss selected hepatic abnormalities. Chapter 19 on ultrasound will describe some of the more common biliary and pelvic abnormalities.

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to recognize some of the most common abnormalities of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the esophagus to the rectum. We’ll also discuss selected hepatic abnormalities. Chapter 19 on ultrasound will describe some of the more common biliary and pelvic abnormalities. CT, ultrasound, and MRI have essentially replaced conventional radiography and, in some instances, barium studies for the evaluation of the GI tract and the visceral abdominal organs.

CT, ultrasound, and MRI have essentially replaced conventional radiography and, in some instances, barium studies for the evaluation of the GI tract and the visceral abdominal organs.Barium Studies of the Gastrointestinal Tract

During the performance of barium studies, fluoroscopic spot films and overhead films are usually obtained by the radiologist and radiologic technologist in several projections for whatever part of the GI tract is being studied, depending on the nature of the abnormality and the mobility of the patient.

During the performance of barium studies, fluoroscopic spot films and overhead films are usually obtained by the radiologist and radiologic technologist in several projections for whatever part of the GI tract is being studied, depending on the nature of the abnormality and the mobility of the patient. As you go through this chapter, you will probably want to refer to the two tables in this chapter, one on terminology used in describing studies of the GI tract (Table 18-1) and the other on basic principles in GI radiology (Table 18-2), both of which will prove helpful in understanding the terms and concepts used here.

As you go through this chapter, you will probably want to refer to the two tables in this chapter, one on terminology used in describing studies of the GI tract (Table 18-1) and the other on basic principles in GI radiology (Table 18-2), both of which will prove helpful in understanding the terms and concepts used here.| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fluoroscopy | Utilization by the radiologist of special x-ray-producing equipment to observe in real time the dynamic movement of the bowel and to optimally position the patient so as to obtain diagnostic images frequently referred to as “spot films”; in this chapter, the term is used in reference to utilizing x-rays to image the GI tract. |

| Barium | Barium sulphate in suspension is an inert, radiopaque material prepared in liquid form to study the intraluminal anatomy of the GI tract. |

| Single contrast/double contrast/biphasic examination | A single-contrast (also called full-column) study usually refers to a GI imaging procedure in which only barium is used as the contrast agent; double contrast (sometimes called air contrast) usually refers to a study of the GI tract using both thicker barium and air; a biphasic examination is used to study the upper gastrointestinal tract and utilizes an initial double contrast study followed by a single contrast agent to optimize the study. |

| Filling defect | A lesion, usually of soft tissue density, that protrudes into the lumen and displaces the intraluminal contrast (e.g., a polyp is a filling defect). |

| Ulcer | Refers to a persistent collection of contrast that projects outward from the contrast-filled lumen and originates either through a break in the mucosal lining (as in gastric ulcer) or in a GI mass (as in an ulcerating malignancy). |

| Diverticulum | Refers to a persistent collection of contrast that projects outward from the contrast-filled lumen of the GI tract like an ulcer; unlike an ulcer, the mucosa of a diverticulum is intact; false diverticula represent outpouchings of mucosa and submucosa through the muscularis. |

| Spot films and overhead films | Spot films usually refer to static images obtained by the radiologist who utilizes fluoroscopy to position the patient for the optimum image; overhead films is a term which refers to additional images obtained by the radiologic technologist to complement fluoroscopic spot films using an x-ray tube mounted on the ceiling of the radiographic room (thus, the term overhead). |

| Intraluminal, intramural, extrinsic | Intraluminal (sometimes shortened to luminal) lesions are generally those that arise from the mucosa, like polyps and carcinomas; intramural (sometimes shortened to mural) lesions are those that arise from the wall, in this chapter from the GI tract, such as leiomyomas and lipomas; extrinsic lesions arise outside of the GI tract, e.g., serosal metastases or endometriosis implants. |

| En face and in profile | When you look at a lesion directly “head-on,” you are seeing it en face; a lesion seen tangentially (from the side) is seen in profile; except for those that are perfect spheres, lesions will have a different shape when viewed en face and in profile. |

TABLE 18-2 COMMON PRINCIPLES FOR ALL BARIUM STUDIES

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fully distended vs. collapsed | Only loops that are fully distended by contrast can be accurately evaluated no matter what part of the GI tract is being studied; evaluating certain criteria (such as wall thickness) using collapsed loops may introduce errors of diagnosis. |

| Change and distensibility | Over time (usually measured in seconds), the walls of all of the GI luminal structures, from esophagus to rectum, change in contour, distending and ballooning outward with increasing volumes of barium and air. Change and distensibility are normal. |

| Rigid, stiff, fixed, nondistensible | If the bowel wall is infiltrated by tumor, blood, edema, or fibrous tissue, for example, the bowel may lose its ability to change and distend; this lack of distensibility is variously called rigidity, stiffening, fixed, nondistensible. This is abnormal. |

| Irregularity | Except for the normal marginal indentations caused by the folds in the stomach, small bowel, and colon, the walls of the entire GI tract appear relatively smooth and regular; diseases can produce ulceration, infiltration, and nodularity with resultant irregularity of the wall. |

| Persistence | Almost without exception, an apparent abnormality must be seen on more than one image to be considered a pathologic finding; transient changes in the GI tract caused by peristalsis, ingested food, the presence of stool, or incompletely distended loops of bowel will disappear over time, but true abnormalities will remain constant and persistent. |

Esophagus

Single- and double-contrast examinations of the esophagus are performed with the patient drinking liquid barium either by itself (single contrast) or accompanied by a gas-producing agent that provides the “air” in a double-contrast examination. Since both the single- and double-contrast techniques have their own strengths, many esophagrams are routinely performed using both techniques, called a biphasic examination.

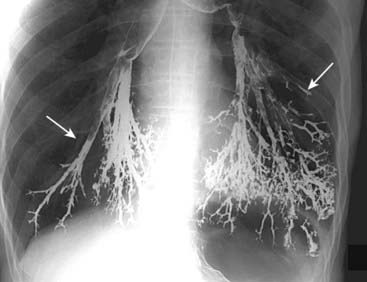

Single- and double-contrast examinations of the esophagus are performed with the patient drinking liquid barium either by itself (single contrast) or accompanied by a gas-producing agent that provides the “air” in a double-contrast examination. Since both the single- and double-contrast techniques have their own strengths, many esophagrams are routinely performed using both techniques, called a biphasic examination. Video esophagography (video swallowing function) is a study of the swallowing mechanism, usually performed with fluoroscopy and frequently captured dynamically—digitally, on videotape, or on film. This is the study of choice for diagnosing and documenting aspiration, in which ingested substances pass into the trachea below the level of the vocal cords (Fig. 18-1).

Video esophagography (video swallowing function) is a study of the swallowing mechanism, usually performed with fluoroscopy and frequently captured dynamically—digitally, on videotape, or on film. This is the study of choice for diagnosing and documenting aspiration, in which ingested substances pass into the trachea below the level of the vocal cords (Fig. 18-1). Fluoroscopic observation of the esophagus can also reveal abnormalities in esophageal motility. For example, tertiary waves are a common but nonspecific abnormality of esophageal motility, representing disordered and nonpropulsive contractions of the esophagus. They can be observed fluoroscopically and captured on spot images (Fig. 18-2).

Fluoroscopic observation of the esophagus can also reveal abnormalities in esophageal motility. For example, tertiary waves are a common but nonspecific abnormality of esophageal motility, representing disordered and nonpropulsive contractions of the esophagus. They can be observed fluoroscopically and captured on spot images (Fig. 18-2).

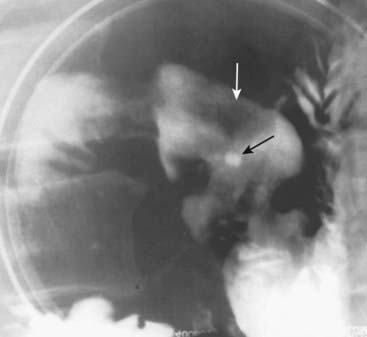

Figure 18-1 Aspiration, barium gone wild.

Frontal radiograph of the lung bases demonstrates high density material outlining the tracheobronchial tree (solid white arrows). The material is barium that was aspirated into the lung during an upper gastrointestinal series. Barium is inert and did not cause any additional symptoms that the patient wasn’t already experiencing from aspirating his own secretions. It will take some time, but most of this barium will be reabsorbed, most likely leaving only a small amount remaining.

This is a severe example of disordered and nonpropulsive waves of contraction in the esophagus called tertiary waves (solid white arrows). The term corkscrew-esophagus is sometimes applied to this appearance. Tertiary waves are a nonspecific and very common abnormality that increases in frequency with advancing age.

Esophageal Diverticula

Diverticula of the GI tract are usually produced when the mucosal and submucosal layers herniate through a defect in the muscular layer of the bowel wall. Wherever they occur in the GI tract, diverticula produce an outpouching that projects beyond the borders of the lumen.

Diverticula of the GI tract are usually produced when the mucosal and submucosal layers herniate through a defect in the muscular layer of the bowel wall. Wherever they occur in the GI tract, diverticula produce an outpouching that projects beyond the borders of the lumen.

![]() Esophageal diverticula occur in three locations: the neck, around the carina, and just above the diaphragm. In the neck, the diverticulum is posteriorly located and is called a Zenker diverticulum. Diverticula at the level of the carina may be due to extrinsic inflammatory disease like tuberculosis (traction diverticula); diverticula just above the esophagogastric junction are called epiphrenic diverticula (Fig. 18-3).

Esophageal diverticula occur in three locations: the neck, around the carina, and just above the diaphragm. In the neck, the diverticulum is posteriorly located and is called a Zenker diverticulum. Diverticula at the level of the carina may be due to extrinsic inflammatory disease like tuberculosis (traction diverticula); diverticula just above the esophagogastric junction are called epiphrenic diverticula (Fig. 18-3).

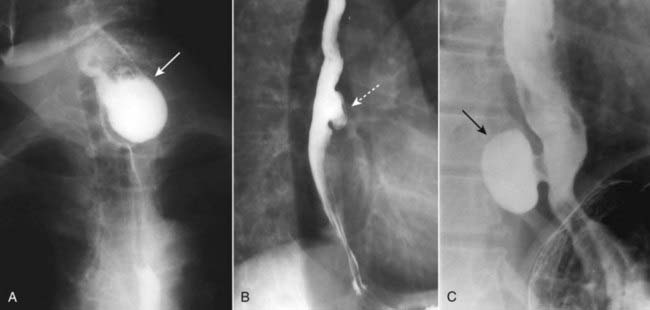

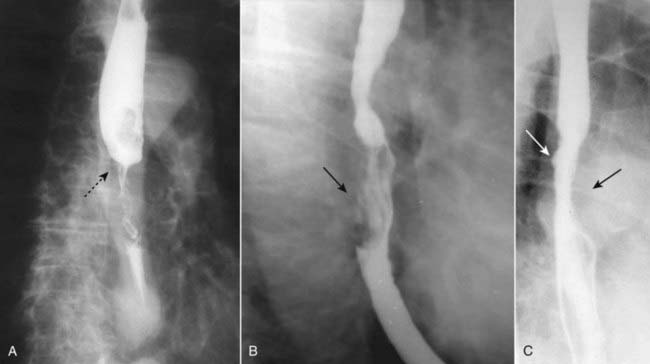

Figure 18-3 Esophageal diverticula.

Esophageal diverticula characteristically occur (A) in the neck from a localized weakness in the posterior wall of the hypopharynx (Zenker diverticulum) (solid white arrow); in the mid-esophagus (B) from extrinsic disease like TB that causes fibrosis, which pulls on the esophagus forming a traction diverticulum (dotted white arrow); or (C) just above the diaphragm in the distal esophagus (epiphrenic diverticulum) (solid black arrow). Only the traction diverticulum is a true diverticulum in that it contains all layers of the esophagus; the Zenker and epiphrenic are false or pseudodiverticula because the mucosa and submucosa herniate through a defect in the muscular layer.

Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophageal carcinoma continues to have a very poor prognosis as more than 50% of patients will have metastases upon initial presentation. The lack of an esophageal serosa and a rich supply of lymphatics aid in the extension and dissemination of esophageal carcinoma. A combination of long-term alcohol and tobacco use are associated with a higher risk of esophageal carcinoma.

Esophageal carcinoma continues to have a very poor prognosis as more than 50% of patients will have metastases upon initial presentation. The lack of an esophageal serosa and a rich supply of lymphatics aid in the extension and dissemination of esophageal carcinoma. A combination of long-term alcohol and tobacco use are associated with a higher risk of esophageal carcinoma. Esophageal malignancies are either squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas, the latter of which are increasing in prevalence. Adenocarcinomas arise in esophageal epithelium that has undergone metaplasia from squamous to columnar epithelium (Barrett esophagus), a process in which gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) plays a major role.

Esophageal malignancies are either squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas, the latter of which are increasing in prevalence. Adenocarcinomas arise in esophageal epithelium that has undergone metaplasia from squamous to columnar epithelium (Barrett esophagus), a process in which gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) plays a major role. Barium esophagrams are frequently the initial study in patients with symptoms, like dysphagia, that suggest this diagnosis.

Barium esophagrams are frequently the initial study in patients with symptoms, like dysphagia, that suggest this diagnosis. Esophageal carcinomas may appear in one or more of several forms, including an annular-constricting lesion, polypoid mass, a superficial, infiltrating lesion or ulceration, and irregularity of the wall. Most often, they present as a mixture of several of these patterns (Fig. 18-4).

Esophageal carcinomas may appear in one or more of several forms, including an annular-constricting lesion, polypoid mass, a superficial, infiltrating lesion or ulceration, and irregularity of the wall. Most often, they present as a mixture of several of these patterns (Fig. 18-4).

Figure 18-4 Esophageal carcinomas.

Three different patients are shown with different appearances of esophageal carcinoma. A, There is an annular constricting lesion of the mid-esophagus (dotted black arrow)—the tumor encircles the normal lumen and obstructs it, in this case. B, A polypoid mass that arises from the right lateral wall of the esophagus displaces the barium around it (solid black arrow). C, The wall is irregular and rigid and contains a small ulceration (solid white arrow); the aortic knob is producing a normal indentation on the opposite wall of the esophagus (solid black arrow).

Hiatal Hernia and Gastroesophageal Reflux (GERD)

Hiatal hernias are divided into the sliding type (almost all) in which the esophagogastric (EG) junction lies above the diaphragm or the paraesophageal type (1%) in which a portion of the stomach herniates through the esophageal hiatus but the EG junction remains below the diaphragm. In general, hiatal hernias increase in incidence with age.

Hiatal hernias are divided into the sliding type (almost all) in which the esophagogastric (EG) junction lies above the diaphragm or the paraesophageal type (1%) in which a portion of the stomach herniates through the esophageal hiatus but the EG junction remains below the diaphragm. In general, hiatal hernias increase in incidence with age. Most hiatal hernias are asymptomatic, but there is an association between the presence of some hiatal hernias and clinically significant gastroesophageal reflux.

Most hiatal hernias are asymptomatic, but there is an association between the presence of some hiatal hernias and clinically significant gastroesophageal reflux.

![]() The radiologic findings of hiatal hernia include a bulbous area of the distal esophagus containing oral contrast at the level of the diaphragm with failure of the esophagus to narrow on multiple images as it passes through the esophageal hiatus, extension of multiple gastric folds above the diaphragm, and sometimes visualization of a thin, circumferential filling defect in the distal esophagus called a Schatzki ring.

The radiologic findings of hiatal hernia include a bulbous area of the distal esophagus containing oral contrast at the level of the diaphragm with failure of the esophagus to narrow on multiple images as it passes through the esophageal hiatus, extension of multiple gastric folds above the diaphragm, and sometimes visualization of a thin, circumferential filling defect in the distal esophagus called a Schatzki ring.

Gastroesophageal reflux may be evident during fluoroscopy when barium is seen to move from the stomach retrograde into the esophagus, but reflux is intermittent so that it may not occur during the course of the examination. The absence of reflux during the study does not exclude reflux, and demonstration of reflux does not necessarily indicate the patient has the complications of GERD, i.e., esophagitis, stricture, and Barrett esophagus.

Gastroesophageal reflux may be evident during fluoroscopy when barium is seen to move from the stomach retrograde into the esophagus, but reflux is intermittent so that it may not occur during the course of the examination. The absence of reflux during the study does not exclude reflux, and demonstration of reflux does not necessarily indicate the patient has the complications of GERD, i.e., esophagitis, stricture, and Barrett esophagus.

Figure 18-5 Sliding hiatal hernia.

There is a bulbous collection of contrast representing the stomach herniated above the diaphragm. There are gastric folds present in the hernia, identifying it as part of the stomach (solid white arrow). Notice the esophagus does not narrow as it normally does when passing through the esophageal hiatus (dashed white arrow). Just above the hernia is a thin, weblike filling defect characteristic of a Schatzki ring (dotted white arrow). The Schatzki ring marks the level of the esophagogastric junction.

Stomach and Duodenum

Today, the lumen of the stomach is most often studied by upper endoscopy; the wall thickness and structures outside of the stomach are studied by CT examination of the abdomen with oral contrast. Nevertheless, biphasic upper gastrointestinal (UGI) examinations, which include a study of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, remain a sensitive, cost-effective, readily available, and noninvasive examination.

Today, the lumen of the stomach is most often studied by upper endoscopy; the wall thickness and structures outside of the stomach are studied by CT examination of the abdomen with oral contrast. Nevertheless, biphasic upper gastrointestinal (UGI) examinations, which include a study of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, remain a sensitive, cost-effective, readily available, and noninvasive examination.Gastric Ulcers

In the United States, the incidence of gastric ulcer disease has been declining. In adults, infection with Helicobacter pylori accounts for almost three out of four cases of gastric ulcer disease. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents account for most of the rest.

In the United States, the incidence of gastric ulcer disease has been declining. In adults, infection with Helicobacter pylori accounts for almost three out of four cases of gastric ulcer disease. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents account for most of the rest.

![]() Most ulcers occur on the lesser curvature or posterior wall in the region of the body or antrum. About 95% of all gastric ulcers are benign. The other 5% will represent ulcerations in gastric malignancies (Fig. 18-6).

Most ulcers occur on the lesser curvature or posterior wall in the region of the body or antrum. About 95% of all gastric ulcers are benign. The other 5% will represent ulcerations in gastric malignancies (Fig. 18-6).

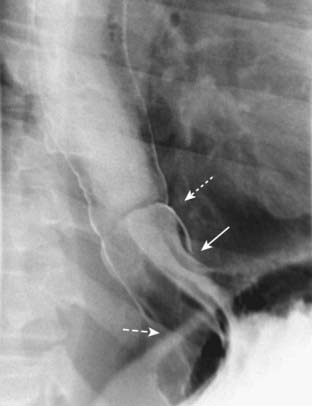

Figure 18-6 Benign lesser curvature gastric ulcer.

A, Seen in profile is a large collection of barium that protrudes beyond the expected contour of the normal body of the stomach along the lesser curvature representing a gastric ulcer (solid white arrow). This ulcer collection was present on multiple views (an important characteristic of an ulcer called persistence). The mound of edematous tissue that surrounds the ulcer (dotted white arrow) is called an ulcer collar. B, Seen en face, there are numerous gastric folds (dotted white arrow) that all radiate to the ulcer margin and a central collection (solid black arrow) representing the ulcer itself. This was a benign gastric ulcer.

Gastric Carcinoma

There has been a dramatic decline in the incidence of gastric carcinomas in the United States. The mortality, however, remains quite high as they are frequently not diagnosed until after they have spread. Most gastric carcinomas (actually, they are adenocarcinomas) occur in the distal third of the stomach along the lesser curvature.

There has been a dramatic decline in the incidence of gastric carcinomas in the United States. The mortality, however, remains quite high as they are frequently not diagnosed until after they have spread. Most gastric carcinomas (actually, they are adenocarcinomas) occur in the distal third of the stomach along the lesser curvature. Double-contrast UGI images and CT scans of the abdomen can demonstrate gastric carcinomas. CT is utilized for staging the extent of the tumor and degree of spread.

Double-contrast UGI images and CT scans of the abdomen can demonstrate gastric carcinomas. CT is utilized for staging the extent of the tumor and degree of spread. Gastric carcinomas may be polypoid, infiltrating (i.e., linitis plastica), or ulcerative in form (Fig. 18-7).

Gastric carcinomas may be polypoid, infiltrating (i.e., linitis plastica), or ulcerative in form (Fig. 18-7). There are other mass lesions that may resemble gastric carcinoma, including leiomyomas, a benign, wall lesion that characteristically ulcerates, and lymphoma, which may produce diffusely thickened folds or multiple masses in the stomach.

There are other mass lesions that may resemble gastric carcinoma, including leiomyomas, a benign, wall lesion that characteristically ulcerates, and lymphoma, which may produce diffusely thickened folds or multiple masses in the stomach.

Figure 18-7 Carcinomas of the stomach.

A, There is a large, polypoid filling defect in the antrum of the stomach that displaces the barium around it (solid black arrow). Contained within the mass and seen en face is an irregularly shaped collection of barium that represents an ulceration in the mass (dotted black arrow). This was an adenocarcinoma of the stomach. B, The entire body of the stomach displays a lack of distensibility, losing the normal ballooning outward that every portion of the GI tract demonstrates when filled with enough barium or air. Instead, the walls of the stomach are concave inward (solid white arrows) and rigid, a sign of malignancy. This stomach would display the same appearance on all images. This is the typical appearance for linitis plastica, caused by an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the stomach.

Duodenal Ulcer

![]() Duodenal ulcers are two to three times more common than gastric ulcers. Almost all duodenal ulcers occur in the duodenal bulb, the majority on the anterior wall of the bulb. They are overwhelmingly caused by H. pylori infection (85%-95%).

Duodenal ulcers are two to three times more common than gastric ulcers. Almost all duodenal ulcers occur in the duodenal bulb, the majority on the anterior wall of the bulb. They are overwhelmingly caused by H. pylori infection (85%-95%).

Double-contrast UGI series have a sensitivity that exceeds 90% in detecting duodenal ulcers (Fig. 18-8).

Double-contrast UGI series have a sensitivity that exceeds 90% in detecting duodenal ulcers (Fig. 18-8). Complications of duodenal ulcers, best demonstrated by CT, include obstruction, perforation (into the peritoneal cavity), penetration (such as into the pancreas), or hemorrhage (Fig. 18-9).

Complications of duodenal ulcers, best demonstrated by CT, include obstruction, perforation (into the peritoneal cavity), penetration (such as into the pancreas), or hemorrhage (Fig. 18-9).

Figure 18-8 Acute duodenal ulcer.

Contained within the duodenal bulb on its anterior wall is a collection of barium (solid black arrow), shown to be persistent on a number of other images, surrounded by a zone of edema (solid white arrow) that displaces the barium from around the ulcer. This collection is characteristic of an acute duodenal ulcer. When duodenal ulcers heal, they are likely to do so with scarring that deforms the normal triangular contour of the bulb.

Figure 18-9 Perforated duodenal ulcer.

Axial CT scan of the upper abdomen done with oral and intravenous contrast shows a leak of oral contrast from the duodenum (solid white arrow) into the peritoneal cavity (dotted white arrow). Obstruction, perforation, and hemorrhage are common complications of ulcer disease. The patient had a perforated duodenal ulcer repaired at surgery.

Small and Large Bowel

General Considerations

Opacification and distension of the bowel lumen is necessary for proper evaluation of the bowel no matter what imaging modality is used.

Opacification and distension of the bowel lumen is necessary for proper evaluation of the bowel no matter what imaging modality is used.

![]() Collapsed or unopacified loops of bowel can introduce errors of diagnosis related to our inability to first visualize and then to differentiate real from artifactual findings or to accurately characterize the abnormality even if recognized. On CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis, unopacified loops of bowel may mimic masses or adenopathy, and wall thickness is difficult to assess if the bowel is not distended.

Collapsed or unopacified loops of bowel can introduce errors of diagnosis related to our inability to first visualize and then to differentiate real from artifactual findings or to accurately characterize the abnormality even if recognized. On CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis, unopacified loops of bowel may mimic masses or adenopathy, and wall thickness is difficult to assess if the bowel is not distended.

Therefore, orally administered contrast, frequently given in temporally divided doses to allow earlier contrast to reach the colon while later contrast opacifies the stomach, is routinely utilized for most abdominal CT scans except those performed for trauma, the stone search study, and studies specifically directed towards evaluating vascular structures like the aorta.

Therefore, orally administered contrast, frequently given in temporally divided doses to allow earlier contrast to reach the colon while later contrast opacifies the stomach, is routinely utilized for most abdominal CT scans except those performed for trauma, the stone search study, and studies specifically directed towards evaluating vascular structures like the aorta.

Thickening of the bowel wall. The normal small bowel lumen does not exceed about 2.5 cm in diameter, and the wall is usually no thicker than 3 mm. The colonic wall does not exceed 3 mm with the lumen distended.

Thickening of the bowel wall. The normal small bowel lumen does not exceed about 2.5 cm in diameter, and the wall is usually no thicker than 3 mm. The colonic wall does not exceed 3 mm with the lumen distended. Submucosal edema or hemorrhage. Submucosal infiltration produces varying degrees of thumbprinting, nodular indentations into the bowel lumen representing focal areas of submucosal infiltration by edema, hemorrhage, inflammatory cells, tumor (lymphoma), or amyloid.

Submucosal edema or hemorrhage. Submucosal infiltration produces varying degrees of thumbprinting, nodular indentations into the bowel lumen representing focal areas of submucosal infiltration by edema, hemorrhage, inflammatory cells, tumor (lymphoma), or amyloid. Hazy or strandlike infiltration of the surrounding fat. Extension of inflammatory reaction outside of the bowel into the adjacent fat is a sentinel finding that heralds associated disease (Fig. 18-10).

Hazy or strandlike infiltration of the surrounding fat. Extension of inflammatory reaction outside of the bowel into the adjacent fat is a sentinel finding that heralds associated disease (Fig. 18-10). Extraluminal contrast or extraluminal air. Indicates the presence of a bowel perforation (Fig. 18-11).

Extraluminal contrast or extraluminal air. Indicates the presence of a bowel perforation (Fig. 18-11).

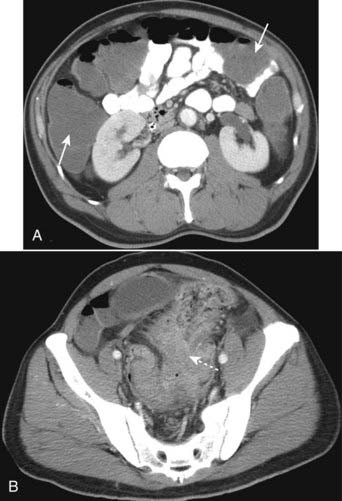

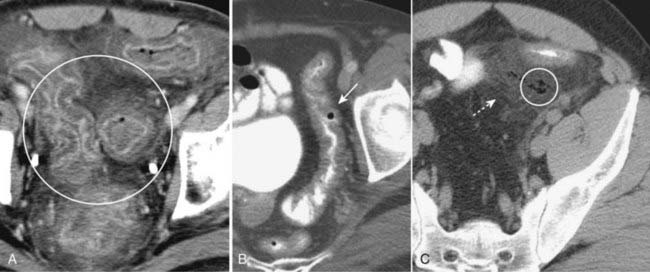

Figure 18-10 Key findings on CT of the GI tract.

Findings applicable to any part of the bowel and key to the diagnosis of bowel abnormalities on CT. A, There is thickening and enhancement of the wall of the bowel (circle). When distended, as these loops of large bowel are, the bowel wall is normally very thin. B, There is submucosal infiltration of the wall (thumbprinting) (solid white arrow). In this case of ischemic colitis, it most likely represents edema with some hemorrhage. C, Infiltration of the surrounding fat is seen (dotted white arrow), a sentinel finding that usually heralds adjacent inflammation. There is also extraluminal air (circle), a sign of bowel perforation.

Figure 18-11 Free air from bowel perforation.

With the patient lying supine for this CT scan, free intraperitoneal air (solid white arrows) rises to the highest part of the abdomen beneath the anterior abdominal wall. Most cases of free intraperitoneal air (pneumoperitoneum) are due to perforations from gastric and duodenal ulcers.

Small Bowel: Crohn Disease

Crohn disease is a chronic, relapsing, granulomatous inflammation of the small bowel and colon resulting in ulceration, obstruction and fistula formation. Crohn disease typically involves the ileum and right colon, presents with skip areas (abnormal bowel interposed between normal bowel), is prone to fistula formation, and has a propensity for recurring following surgical resection and reanastamosis in whatever loop of bowel becomes the new terminal ileum.

Crohn disease is a chronic, relapsing, granulomatous inflammation of the small bowel and colon resulting in ulceration, obstruction and fistula formation. Crohn disease typically involves the ileum and right colon, presents with skip areas (abnormal bowel interposed between normal bowel), is prone to fistula formation, and has a propensity for recurring following surgical resection and reanastamosis in whatever loop of bowel becomes the new terminal ileum. Crohn disease may be imaged either with a barium small bowel follow-through (series) or CT of the abdomen and pelvis.

Crohn disease may be imaged either with a barium small bowel follow-through (series) or CT of the abdomen and pelvis.

![]() Imaging findings in Crohn disease include narrowing, irregularity, and ulceration of the terminal ileum frequently with proximal small bowel dilatation; separation of the loops of bowel due to fatty infiltration of the mesentery surrounding the ileum, making the affected loop(s) stand apart from the surrounding loops of small bowel (proud loop); the string sign—narrowing of the terminal ileum into a near slitlike opening by spasm and fibrosis; and fistulae—especially between the ileum and colon but also to the skin, vagina, and urinary bladder (Fig. 18-12).

Imaging findings in Crohn disease include narrowing, irregularity, and ulceration of the terminal ileum frequently with proximal small bowel dilatation; separation of the loops of bowel due to fatty infiltration of the mesentery surrounding the ileum, making the affected loop(s) stand apart from the surrounding loops of small bowel (proud loop); the string sign—narrowing of the terminal ileum into a near slitlike opening by spasm and fibrosis; and fistulae—especially between the ileum and colon but also to the skin, vagina, and urinary bladder (Fig. 18-12).

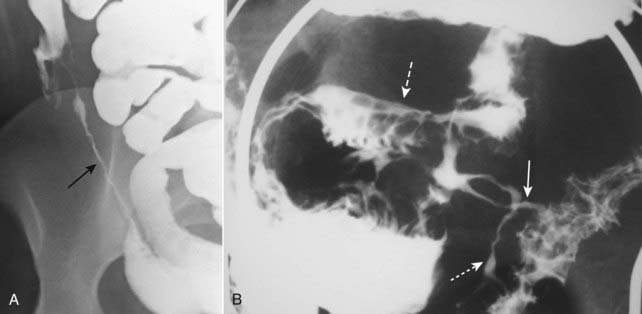

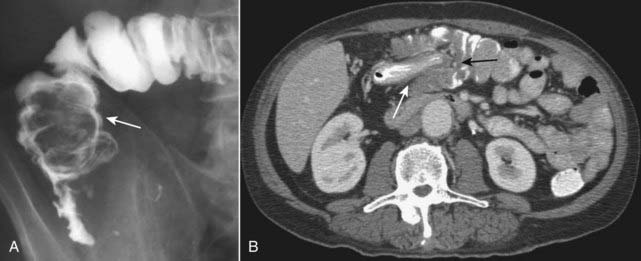

A, The terminal ileum (solid black arrow) is markedly narrowed (string sign) and stands apart from other loops of small bowel (proud loop). B, A close-up image of the right lower quadrant from a small bowel follow-through study in another patient shows multiple streaks of barium (solid and dotted white arrows) representing multiple enteric fistulae originating from an abnormal loop of small bowel (dashed white arrow) and connecting with each other and the large bowel. Fistula formation is a common complication of this disease.

Diverticulosis

Colonic diverticula, like most diverticula of the GI tract, represent herniation of the mucosa and submucosa through a defect in the muscular layer (false diverticula).

Colonic diverticula, like most diverticula of the GI tract, represent herniation of the mucosa and submucosa through a defect in the muscular layer (false diverticula).

![]() They occur more frequently with increasing age and may be due, at least in part, to increase in intraluminal pressure and weakening of the colonic wall. They are usually multiple (diverticulosis), are almost always asymptomatic (about 90% of the time) but can become inflamed or bleed. Diverticulosis is the most common cause of massive lower GI bleeding. When they bleed, the right-sided diverticula seem to bleed more than those on the left.

They occur more frequently with increasing age and may be due, at least in part, to increase in intraluminal pressure and weakening of the colonic wall. They are usually multiple (diverticulosis), are almost always asymptomatic (about 90% of the time) but can become inflamed or bleed. Diverticulosis is the most common cause of massive lower GI bleeding. When they bleed, the right-sided diverticula seem to bleed more than those on the left.

They occur most often in the sigmoid colon and are readily identified on either barium enema or CT examination as small spikes or smoothly contoured collections of air or contrast attached to the colon (Fig. 18-13).

They occur most often in the sigmoid colon and are readily identified on either barium enema or CT examination as small spikes or smoothly contoured collections of air or contrast attached to the colon (Fig. 18-13).

A, In this CT scan of the pelvis, diverticula contain air and appear as small, usually round outpouchings, especially in the region of the sigmoid colon (white oval). B, There are numerous outpouchings containing barium seen in the sigmoid colon of this air-contrast barium enema examination. Some diverticula are filled with barium (solid black arrow), while others contain air and are outlined with barium (dotted white arrow). Where a diverticulum is seen en face, it produces a circular density (solid white arrow), which can mimic the appearance of a polyp.

Diverticulitis

Diverticula can become inflamed and perforate (diverticulitis), most often secondary to mechanical irritation or obstruction. CT is the modality of choice for the diagnosis of diverticulitis since the pericolonic soft tissues can be visualized using CT, which is impossible with either barium enema or optical endoscopy.

Diverticula can become inflamed and perforate (diverticulitis), most often secondary to mechanical irritation or obstruction. CT is the modality of choice for the diagnosis of diverticulitis since the pericolonic soft tissues can be visualized using CT, which is impossible with either barium enema or optical endoscopy.

![]() CT findings of diverticulitis start with the presence of diverticula and include thickening of the adjacent colonic wall (>4 mm); pericolonic inflammation—hazy areas of increased attenuation or streaky, disorganized linear and amorphous densities in the pericolonic fat; abscess formation—multiple small bubbles of air or pockets of fluid contained within a pericolonic soft tissue, masslike density; and perforation of the colon—extraluminal air or contrast either around the site of the perforation or, less likely, free in the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 18-14).

CT findings of diverticulitis start with the presence of diverticula and include thickening of the adjacent colonic wall (>4 mm); pericolonic inflammation—hazy areas of increased attenuation or streaky, disorganized linear and amorphous densities in the pericolonic fat; abscess formation—multiple small bubbles of air or pockets of fluid contained within a pericolonic soft tissue, masslike density; and perforation of the colon—extraluminal air or contrast either around the site of the perforation or, less likely, free in the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 18-14).

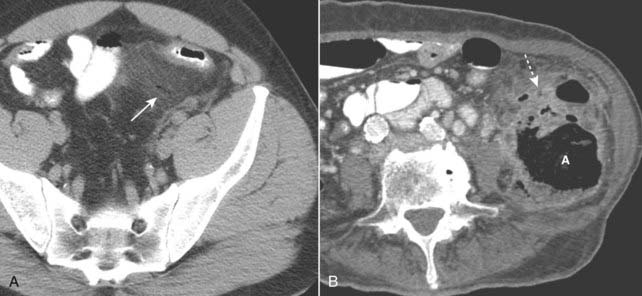

Figure 18-14 Diverticulitis, CT.

A, Infiltration of the pericolonic fat is demonstrated by a hazy increase in attenuation (solid white arrow) of the normal fat. Focal infiltration of fat is a common characteristic of inflammatory disease. B, There is a large abscess cavity (A) in the left lower quadrant in this close-up of a CT scan of the lower abdomen. There are adjacent small bubbles of gas that are not contained within the bowel and infiltration of the normal fat (dotted white arrow). These findings are secondary to a confined perforation with abscess formation from diverticulitis.

Colonic Polyps

The incidence of polyps increases with age and the incidence of malignancy increases with the size of the polyp. Patients with polyposis syndromes, in which multiple adenomatous polyps are present, have a much higher risk of developing a colonic malignancy.

The incidence of polyps increases with age and the incidence of malignancy increases with the size of the polyp. Patients with polyposis syndromes, in which multiple adenomatous polyps are present, have a much higher risk of developing a colonic malignancy.

![]() Most colonic polyps are hyperplastic polyps that have no malignant potential. Adenomatous polyps carry a low potential for malignancy that increases with the size of the polyp so that those >1.5 cm in size have about a 10% chance of being malignant. Therefore, early detection and removal of adenomatous polyps will decrease the chances of malignant transformation.

Most colonic polyps are hyperplastic polyps that have no malignant potential. Adenomatous polyps carry a low potential for malignancy that increases with the size of the polyp so that those >1.5 cm in size have about a 10% chance of being malignant. Therefore, early detection and removal of adenomatous polyps will decrease the chances of malignant transformation.

Colonic polyps can be visualized using barium enema examination, CT (virtual colonoscopy), or optical colonoscopy.

Colonic polyps can be visualized using barium enema examination, CT (virtual colonoscopy), or optical colonoscopy. Virtual colonoscopy is a technique made possible by newer, faster CT and MRI scanners and complex computer algorithms that allow for the three-dimensional reconstruction of the appearance of the inside of the bowel lumen including time-of-flight (motion) displays without the use of an endoscope. Virtual colonoscopy also allows for visualization of the other abdominal structures outside of the colon (Fig. 18-15).

Virtual colonoscopy is a technique made possible by newer, faster CT and MRI scanners and complex computer algorithms that allow for the three-dimensional reconstruction of the appearance of the inside of the bowel lumen including time-of-flight (motion) displays without the use of an endoscope. Virtual colonoscopy also allows for visualization of the other abdominal structures outside of the colon (Fig. 18-15). Polyps may be sessile (attach directly to the wall) or pedunculated (attach to the wall by a stalk) (Fig. 18-16). A polyp may contain numerous fronds that produce an irregular, wormlike surface with numerous crypts that may contain barium (villous polyp). Villous polyps tend to be larger and have more of a malignant potential than other adenomatous polyps (Fig. 18-17).

Polyps may be sessile (attach directly to the wall) or pedunculated (attach to the wall by a stalk) (Fig. 18-16). A polyp may contain numerous fronds that produce an irregular, wormlike surface with numerous crypts that may contain barium (villous polyp). Villous polyps tend to be larger and have more of a malignant potential than other adenomatous polyps (Fig. 18-17). Occasionally, a polyp may serve as a lead point for an intussusception, in which the polyp drags and prolapses one part of the bowel into the lumen of the bowel immediately ahead of it. The bowel proximal to the intussusception is usually obstructed and dilated. Intussusception may produce a characteristic coiled-spring appearance on barium enema or CT (Fig. 18-18).

Occasionally, a polyp may serve as a lead point for an intussusception, in which the polyp drags and prolapses one part of the bowel into the lumen of the bowel immediately ahead of it. The bowel proximal to the intussusception is usually obstructed and dilated. Intussusception may produce a characteristic coiled-spring appearance on barium enema or CT (Fig. 18-18).

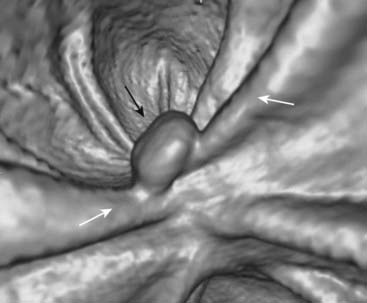

Figure 18-15 Polyp on virtual colonoscopy.

Virtual colonoscopy utilizes CT scanning of the abdomen to allow for the three-dimensional reconstruction of the appearance of the inside of the bowel lumen without the use of an endoscope. A polyp in the descending colon (solid black arrow) is seen as a distinct mass, while the normal haustral folds (solid white arrows) are ridgelike structures present throughout the large bowel.

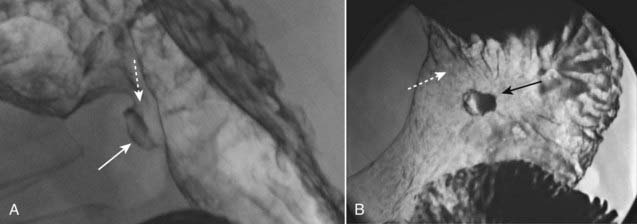

Figure 18-16 Sessile and pedunculated polyps of the colon.

Polyps can be recognized as persistent filling defects in the colon; barium is displaced by the polyp. A, There is a sessile filling defect in the pool of barium along the left lateral wall of the sigmoid colon (solid black arrow). The size of the lesion should raise concern for malignancy. B, In another patient with a filling defect in the sigmoid colon etched by barium (dotted white arrow), the polyp is seen to be attached to the wall of the colon by a stalk (solid white arrow). Polyps on a stalk are called pedunculated polyps.

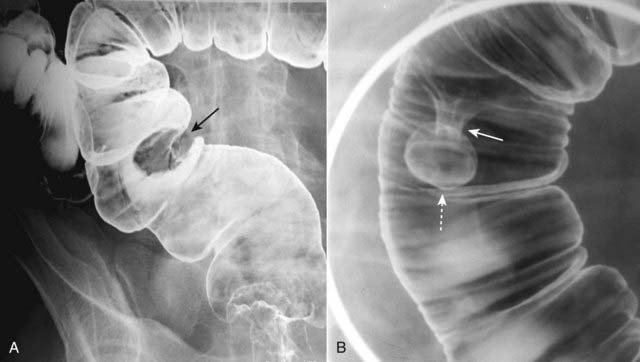

Figure 18-17 Villous tumor of cecum.

There is a large, polypoid mass in the cecum (outlined by both black and white solid arrows). Contained within the mass is an interlacing network of white lines representing barium that is trapped within the interstices of the frondlike projections from this tumor. This is a characteristic appearance for a villous adenomatous tumor.

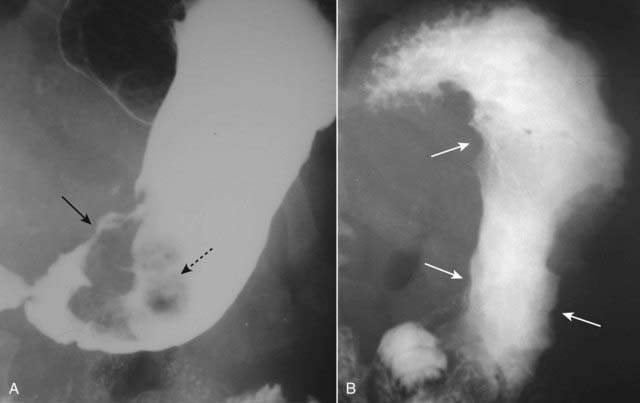

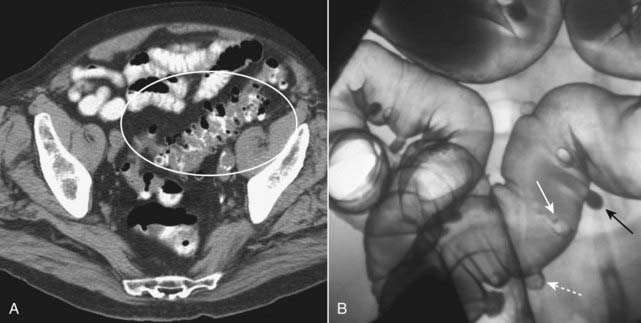

Figure 18-18 Intussusception, barium enema, and CT scan.

A, When one loop of bowel prolapses inside the loop immediately distal to it, the resultant obstruction produces a coiled-spring appearance on barium enema examination as two loops of bowel are superimposed on one another (solid white arrow). B, In another patient with an intussusception, a loop of large bowel (solid white arrow) is seen prolapsing into the loop distal to it (solid black arrow) producing a filling defect and obstructing the lumen.

Colonic Carcinoma

![]() Colon cancer is the most common cancer of the GI tract. Most colon cancers occur in the rectosigmoid region and take years to develop. Risk factors include adenomatous polyps, ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease, polyposis syndromes, family history of colonic polyps or colon cancer, and prior pelvic irradiation.

Colon cancer is the most common cancer of the GI tract. Most colon cancers occur in the rectosigmoid region and take years to develop. Risk factors include adenomatous polyps, ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease, polyposis syndromes, family history of colonic polyps or colon cancer, and prior pelvic irradiation.

The imaging findings of carcinoma of the colon include the presence of a persistent, large, polypoid filling defect; annular constriction of the colonic lumen producing an apple core lesion (Fig. 18-19); and frank or microperforation—infiltration of the pericolonic fat with streaky or hazy densities of increased attenuation with or without the presence of extraluminal air.

The imaging findings of carcinoma of the colon include the presence of a persistent, large, polypoid filling defect; annular constriction of the colonic lumen producing an apple core lesion (Fig. 18-19); and frank or microperforation—infiltration of the pericolonic fat with streaky or hazy densities of increased attenuation with or without the presence of extraluminal air. Other findings of carcinoma of the colon can include large bowel obstruction—either antegrade obstruction or retrograde obstruction demonstrated by the inability of rectally administered barium to pass the point of the colon cancer (Fig. 18-20) and metastases, especially to the liver and the lungs.

Other findings of carcinoma of the colon can include large bowel obstruction—either antegrade obstruction or retrograde obstruction demonstrated by the inability of rectally administered barium to pass the point of the colon cancer (Fig. 18-20) and metastases, especially to the liver and the lungs.

Figure 18-19 Annular constricting carcinoma of the rectum.

This is a characteristic apple-core lesion of the rectum caused by circumferential growth of a colonic carcinoma. The margins of the lesion (solid black arrows) demonstrate what is called an overhanging edge where tumor tissue projects into and overhangs the normal lumen, typical of this type of lesion. The “core” of the “apple” (solid white arrow) is composed of tumor tissue—all of the normal colonic mucosa has been replaced. Identification of such a lesion is pathognomonic for carcinoma.

Colitis

Colitis is inflammation of the large bowel. There are numerous causes of colitis, including infectious, ulcerative and granulomatous, ischemic, radiation-induced, and antibiotic-associated etiologies. Because many forms of colitis appear similar radiographically, clinical history is of paramount importance.

Colitis is inflammation of the large bowel. There are numerous causes of colitis, including infectious, ulcerative and granulomatous, ischemic, radiation-induced, and antibiotic-associated etiologies. Because many forms of colitis appear similar radiographically, clinical history is of paramount importance.

![]() CT findings of colitis include segmental thickening of the bowel wall, irregular narrowing of the bowel lumen due to edema (i.e., thumbprinting) (Fig. 18-21), and infiltration of the surrounding fat.

CT findings of colitis include segmental thickening of the bowel wall, irregular narrowing of the bowel lumen due to edema (i.e., thumbprinting) (Fig. 18-21), and infiltration of the surrounding fat.

Mesenteric ischemia produces colitis due to diminished blood flow from either occlusion of vessels (thrombus) or from slow flow, as in congestive heart failure, and may differ in appearance from some of the other colitides by its lack of bowel wall enhancement with IV contrast (see Fig. 14-12). There may also be intramural or portal venous gas present (see Fig. 15-15B).

Mesenteric ischemia produces colitis due to diminished blood flow from either occlusion of vessels (thrombus) or from slow flow, as in congestive heart failure, and may differ in appearance from some of the other colitides by its lack of bowel wall enhancement with IV contrast (see Fig. 14-12). There may also be intramural or portal venous gas present (see Fig. 15-15B).

The colon demonstrates thumbprinting (solid white arrows) and a pattern that is called the accordion sign. This patient had C. difficile colitis, formerly called pseudomembranous colitis, and now known to be caused almost exclusively by toxins produced by Clostridium difficile. It frequently follows antibiotic therapy. The diagnosis is usually made clinically by visualization of the pseudomembrane on endoscopy. The accordion sign represents contrast that is trapped between enlarged folds and indicates the presence of marked edema or inflammation, but it is not specific for C. difficile colitis.

Appendicitis

Pathophysiologically, the development of appendicitis is invariably preceded by obstruction of the appendiceal lumen. CT is now the modality of choice in diagnosing appendicitis. Appendicitis is also diagnosed using ultrasound and MRI.

Pathophysiologically, the development of appendicitis is invariably preceded by obstruction of the appendiceal lumen. CT is now the modality of choice in diagnosing appendicitis. Appendicitis is also diagnosed using ultrasound and MRI. An appendicolith is a calcified concretion found in the appendix of about 15% of all people. It will manifest, especially on CT, as a calcification in the lumen of the appendix. The combination of abdominal pain and the presence of an appendicolith is associated with appendicitis about 90% of the time and indicates a higher probability for perforation.

An appendicolith is a calcified concretion found in the appendix of about 15% of all people. It will manifest, especially on CT, as a calcification in the lumen of the appendix. The combination of abdominal pain and the presence of an appendicolith is associated with appendicitis about 90% of the time and indicates a higher probability for perforation.

![]() The key CT findings of acute appendicitis are identification of a dilated appendix (> 6 mm) which does not fill with oral contrast; periappendiceal inflammation—which is evidenced by streaky, disorganized linear high-attenuation densities in the surrounding fat (Fig. 18-22A); and increased contrast enhancement of the wall of the appendix due to inflammation.

The key CT findings of acute appendicitis are identification of a dilated appendix (> 6 mm) which does not fill with oral contrast; periappendiceal inflammation—which is evidenced by streaky, disorganized linear high-attenuation densities in the surrounding fat (Fig. 18-22A); and increased contrast enhancement of the wall of the appendix due to inflammation.

Perforation occurs in up to 30% of cases and is recognized by small quantities of periappendiceal extraluminal air or a periappendiceal abscess. Since obstruction of the appendiceal lumen is a prerequisite for appendicitis, the presence of free intraperitoneal air should point to another diagnosis (Fig. 18-22B).

Perforation occurs in up to 30% of cases and is recognized by small quantities of periappendiceal extraluminal air or a periappendiceal abscess. Since obstruction of the appendiceal lumen is a prerequisite for appendicitis, the presence of free intraperitoneal air should point to another diagnosis (Fig. 18-22B). The appendix of this book (not to be surgically removed) lists the studies of first choice for many different clinical scenarios relating to abdominal pain.

The appendix of this book (not to be surgically removed) lists the studies of first choice for many different clinical scenarios relating to abdominal pain.

Figure 18-22 Appendicitis, CT.

A, There is infiltration of the periappendiceal fat in the right lower quadrant manifest by the increased attenuation in the mesenteric fat (solid white arrow). Focal infiltration of fat is a common characteristic of inflammatory diseases and helps in their localization. B, Contained within the lumen of the appendix is a small calcification (solid black arrow) or appendicolith. There is inflammatory infiltration of the surrounding fat producing high attenuation (solid white arrow). A very small amount of air is present outside of the appendiceal lumen from a confined perforation (dotted white arrow). An appendicolith can be found in about one-fourth of the cases of acute appendicitis. The combination of an appendicolith and acute appendicitis is a strong predictor of a perforated appendix.

Pancreas

Pancreatitis

The two most common causes of pancreatitis are alcoholism and gallstones. Inflammation of pancreatic tissue leading to disruption of the ducts and spillage of pancreatic juices occurs readily because of the lack of a capsule surrounding the pancreas.

The two most common causes of pancreatitis are alcoholism and gallstones. Inflammation of pancreatic tissue leading to disruption of the ducts and spillage of pancreatic juices occurs readily because of the lack of a capsule surrounding the pancreas.

![]() Pancreatitis is a clinical diagnosis, with CT serving to document either a cause (e.g., gallstones) or complication (e.g., pseudocyst formation).

Pancreatitis is a clinical diagnosis, with CT serving to document either a cause (e.g., gallstones) or complication (e.g., pseudocyst formation).

Recognizing acute pancreatitis on CT:

Recognizing acute pancreatitis on CT:

Chronic pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis

Figure 18-23 Acute pancreatitis.

The body of the pancreas is enlarged (solid black arrow). There is infiltration of the peripancreatic fat (solid white arrows). These findings are consistent with acute pancreatitis in the proper clinical setting. This patient had a markedly elevated amylase and lipase.

Figure 18-24 Pancreatic pseudocyst.

Pseudocysts (P) of the pancreas occur when fibrous tissue encapsulates a walled-off collection of pancreatic juices released from the inflamed pancreas. Pseudocysts may have an enhancing wall (solid white arrow). The cyst is indenting a loop of adjacent bowel, in this case the posterior wall of the stomach (S). The indentation on a loop of bowel by an extrinsic mass is called a pad sign (solid black arrow).

![]() The hallmarks of the disease are multiple, amorphous calcifications that form within the dilated ducts of the atrophied gland (see Fig. 16-11).

The hallmarks of the disease are multiple, amorphous calcifications that form within the dilated ducts of the atrophied gland (see Fig. 16-11).

Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

Risk factors for pancreatic adenocarcinoma include alcoholism, cigarette smoking, chronic pancreatitis, and diabetes. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma has an exceedingly poor prognosis: most tumors are unresectable and incurable at the time of diagnosis. Most of the time (75%), the tumor is located in the head of the pancreas; about 10% occur in the body, and 5% in the tail. About half of the patients present with jaundice; most of the time, there is associated pain.

Risk factors for pancreatic adenocarcinoma include alcoholism, cigarette smoking, chronic pancreatitis, and diabetes. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma has an exceedingly poor prognosis: most tumors are unresectable and incurable at the time of diagnosis. Most of the time (75%), the tumor is located in the head of the pancreas; about 10% occur in the body, and 5% in the tail. About half of the patients present with jaundice; most of the time, there is associated pain. Ultrasound is the study of choice in the initial workup of the jaundiced patient (see Chapter 19).

Ultrasound is the study of choice in the initial workup of the jaundiced patient (see Chapter 19).

Figure 18-25 Pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

The head of the pancreas is enlarged by a mass (solid white arrow). Normally, the head of the pancreas should roughly be the same size as the width of the lumbar vertebral body visible on the same cut. Most pancreatic adenocarcinomas are located in the head (75%), and jaundice is a common presenting sign.

Hepatobiliary Abnormalities

Liver: General Considerations

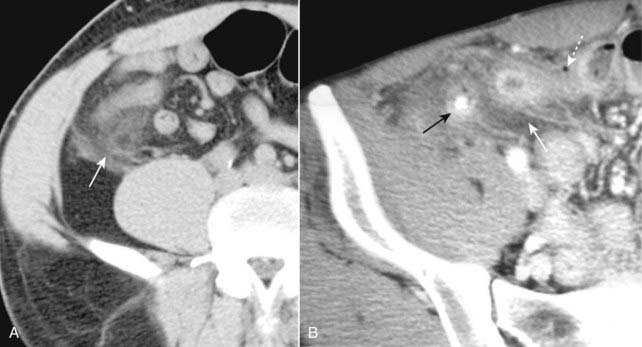

CT evaluation of liver masses is usually done with a combination of scans obtained before and after intravenous contrast injection. Postcontrast scans are obtained in two phases: one is done quickly (hepatic-arterial phase) and a second is done about a minute later (portal-venous phase), the combination helping to best define and characterize liver masses. This combination of three separate scans done without contrast and then during the arterial phase followed by the venous phase is called a triple-phase scan (Fig. 18-26).

CT evaluation of liver masses is usually done with a combination of scans obtained before and after intravenous contrast injection. Postcontrast scans are obtained in two phases: one is done quickly (hepatic-arterial phase) and a second is done about a minute later (portal-venous phase), the combination helping to best define and characterize liver masses. This combination of three separate scans done without contrast and then during the arterial phase followed by the venous phase is called a triple-phase scan (Fig. 18-26). MRI is increasingly utilized as the modality of choice in the evaluation of both focal and diffuse liver disease. MRI can often definitively characterize hepatic lesions described as indeterminate on CT scan as cysts, benign hepatic neoplasms such as hemangioma and focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastatic disease. It is particularly useful in the evaluation of small (1 cm or less) lesions compared to CT.

MRI is increasingly utilized as the modality of choice in the evaluation of both focal and diffuse liver disease. MRI can often definitively characterize hepatic lesions described as indeterminate on CT scan as cysts, benign hepatic neoplasms such as hemangioma and focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastatic disease. It is particularly useful in the evaluation of small (1 cm or less) lesions compared to CT. For routine MRI imaging of the liver, an intravenous contrast agent called gadolinium is typically administered, and multiple postgadolinium enhanced images are obtained. Gadolinium will be discussed in Chapter 20.

For routine MRI imaging of the liver, an intravenous contrast agent called gadolinium is typically administered, and multiple postgadolinium enhanced images are obtained. Gadolinium will be discussed in Chapter 20.

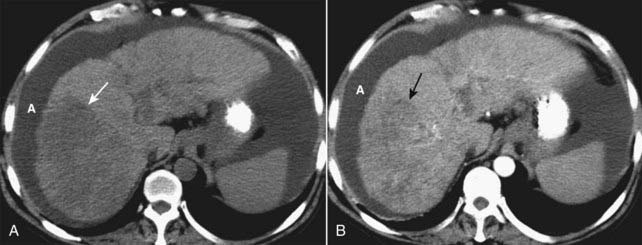

Figure 18-26 Triple-phase CT scan of the liver, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Evaluation of liver masses is usually done with a combination of scans including an unenhanced scan (A) and then two postcontrast scans: one obtained quickly (hepatic-arterial phase) (B) and a second (portal-venous phase) slightly delayed (C). The combination of three scans is called a triple-phase scan. This case shows the typical findings of a focal hepatocellular carcinoma. Most are low density (hypodense) or the same density as normal liver (isodense) without contrast (solid white arrow in A), enhance on the arterial phase with IV contrast (hyperdense) (dotted white arrow in B) and then return to hypodense or isodense on the venous phase (dashed white arrow in C).

Fatty Infiltration

![]() Fatty infiltration (also known as hepatic steatosis) of the liver is a very common abnormality in which there is fat accumulation in the hepatocytes in such diseases as alcoholism, obesity, diabetes, hepatitis, or cirrhosis. Most patients with a fatty liver are asymptomatic. The fatty infiltration may be diffuse or focal, and focal lesions may be solitary or multiple.

Fatty infiltration (also known as hepatic steatosis) of the liver is a very common abnormality in which there is fat accumulation in the hepatocytes in such diseases as alcoholism, obesity, diabetes, hepatitis, or cirrhosis. Most patients with a fatty liver are asymptomatic. The fatty infiltration may be diffuse or focal, and focal lesions may be solitary or multiple.

When diffuse, the liver is usually slightly enlarged. The blood vessels stand out prominently but are usually neither obstructed nor displaced.

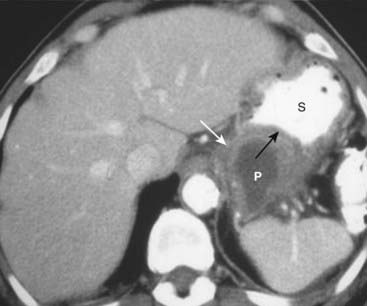

When diffuse, the liver is usually slightly enlarged. The blood vessels stand out prominently but are usually neither obstructed nor displaced. Normally, on noncontrast CT scans, the liver is always denser than or equal to the density of the spleen. With fatty infiltration of the liver, the spleen is denser than the liver without intravenous contrast (Fig. 18-27).

Normally, on noncontrast CT scans, the liver is always denser than or equal to the density of the spleen. With fatty infiltration of the liver, the spleen is denser than the liver without intravenous contrast (Fig. 18-27).

Figure 18-27 Diffuse fatty liver (hepatic steatosis).

Normally, on noncontrast CT scans, the liver is always denser than or equal to the density of the spleen. In this patient with diffuse fatty infiltration of the liver, the spleen (S) is denser than the liver (solid white arrow). Notice how the vessels stand out in the fatty liver (dotted white arrow). (K = kidneys.)

![]() Focal fatty infiltration can produce an appearance that mimics tumor, but fatty infiltration usually produces no mass effect and has the ability to appear and disappear in a matter of weeks, quite unlike tumor masses.

Focal fatty infiltration can produce an appearance that mimics tumor, but fatty infiltration usually produces no mass effect and has the ability to appear and disappear in a matter of weeks, quite unlike tumor masses.

MRI is the most accurate modality in the evaluation of a fatty liver, using a phenomenon called chemical shift imaging to detect the presence of microscopic, intracellular lipid present in such a liver. Chemical shift relates to the way that lipid and water protons behave in the magnetic field (Fig. 18-28).

MRI is the most accurate modality in the evaluation of a fatty liver, using a phenomenon called chemical shift imaging to detect the presence of microscopic, intracellular lipid present in such a liver. Chemical shift relates to the way that lipid and water protons behave in the magnetic field (Fig. 18-28).

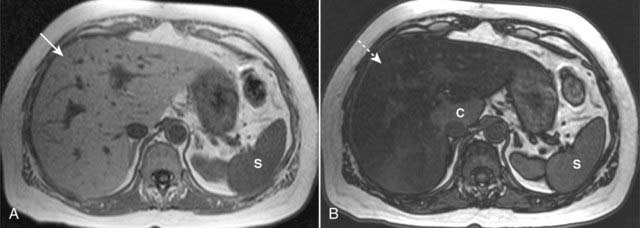

Figure 18-28 Fatty liver, MRI.

Using a phenomenon called chemical shift imaging to detect the presence of microscopic, intracellular lipid present in a fatty liver, MRI is the most accurate imaging modality in identifying a fatty liver. Chemical shift relates to the way that lipid and water protons behave in the magnetic field. A, The liver (solid white arrow) appears normal, brighter than the spleen (S). B, This is called an opposed-phase image, and it demonstrates marked signal loss (signal dropout) throughout the liver (dotted white arrow), indicating a fatty liver. Most of the liver is now darker than the spleen (S), except for the caudate lobe (C), which is normal.

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is a chronic, irreversible disease of the liver which features destruction of normal liver cells and diffuse fibrosis and appears to be the final common pathway of many abnormalities including hepatitis B and C, alcoholism, nonalcoholic fatty infiltration of the liver, and miscellaneous diseases like hemochromatosis and Wilson disease. Complications of cirrhosis include portal hypertension, ascites, renal dysfunction, hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic failure, and death.

Cirrhosis is a chronic, irreversible disease of the liver which features destruction of normal liver cells and diffuse fibrosis and appears to be the final common pathway of many abnormalities including hepatitis B and C, alcoholism, nonalcoholic fatty infiltration of the liver, and miscellaneous diseases like hemochromatosis and Wilson disease. Complications of cirrhosis include portal hypertension, ascites, renal dysfunction, hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic failure, and death.

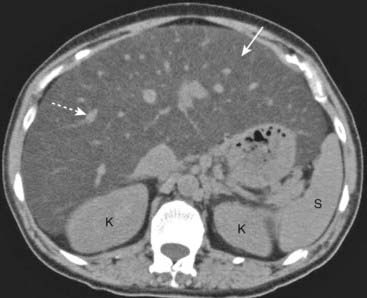

Early in the disease, the liver may demonstrate diffuse fatty infiltration. As the disease progresses, the liver contour becomes lobulated. The liver shrinks in volume with the right lobe characteristically becoming smaller while the caudate lobe and left lobe become disproportionately larger, especially in alcoholic cirrhosis (Fig. 18-29).

Early in the disease, the liver may demonstrate diffuse fatty infiltration. As the disease progresses, the liver contour becomes lobulated. The liver shrinks in volume with the right lobe characteristically becoming smaller while the caudate lobe and left lobe become disproportionately larger, especially in alcoholic cirrhosis (Fig. 18-29). There is a mottled, inhomogeneous appearance to the liver parenchyma following intravenous contrast enhancement due to a mixture of regenerating nodules, focal fatty infiltration, and fibrosis.

There is a mottled, inhomogeneous appearance to the liver parenchyma following intravenous contrast enhancement due to a mixture of regenerating nodules, focal fatty infiltration, and fibrosis. Portal hypertension may develop which can lead to dilated vessels around the stomach, splenic hilum, and esophagus representing varices.

Portal hypertension may develop which can lead to dilated vessels around the stomach, splenic hilum, and esophagus representing varices. Splenomegaly may develop.

Splenomegaly may develop.

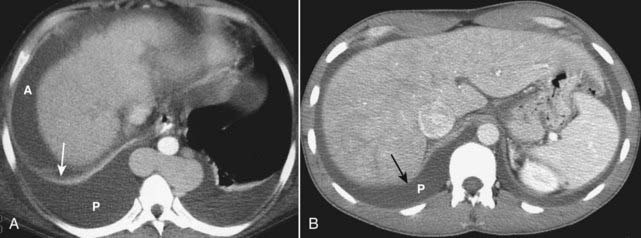

Figure 18-29 Cirrhosis with portal hypertension, CT.

Portal hypertension can lead to dilated vessels around the stomach, splenic hilum (solid white arrows), and esophagus representing varices. Splenomegaly may develop (S). There is characteristic enlargement of the caudate lobe (C) relative to the right lobe of the liver (solid black arrow), especially in alcoholic cirrhosis.

![]() Ascites may be present. Sometimes it can be difficult to differentiate between ascites and pleural effusion on CT examinations (Box 18-1, Fig. 18-30).

Ascites may be present. Sometimes it can be difficult to differentiate between ascites and pleural effusion on CT examinations (Box 18-1, Fig. 18-30).

Box 18-1 Differentiating Ascites from Pleural Effusion

Figure 18-30 Differentiating pleural effusion from ascites.

A, Patients may have a combination of ascites (A) and pleural effusions (P) for a number of reasons, cirrhosis being one of them. Ascitic fluid will appear anterior to the hemidiaphragm (solid white arrow) in the axial plane. Pleural effusion will be located posterior to the hemidiaphragm. B, Ascites will never completely encircle the liver because of the “bare area” (solid black arrow), not covered by peritoneum. Fluid posterior to the bare area must be in the pleural space (P).

Space-Occupying Lesions of the Liver

One of the primary aims of imaging studies, no matter what part of the body is being studied, is to accurately differentiate between benign and malignant processes using techniques that do not place the patient in danger or subject the patient to unnecessary pain. This is the central goal in evaluating liver masses as well.

One of the primary aims of imaging studies, no matter what part of the body is being studied, is to accurately differentiate between benign and malignant processes using techniques that do not place the patient in danger or subject the patient to unnecessary pain. This is the central goal in evaluating liver masses as well.Metastases

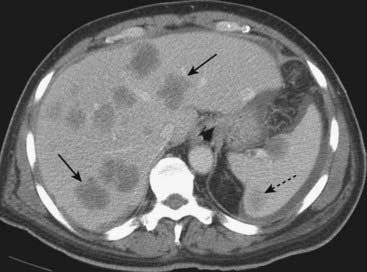

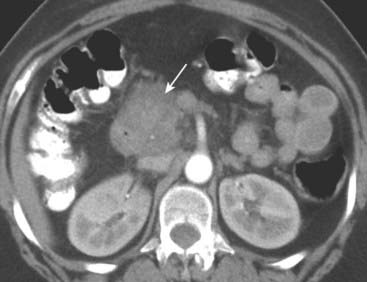

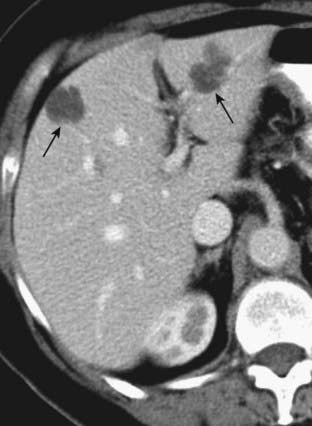

![]() Metastases are the most common malignant hepatic masses. While most are multiple, metastases also represent the most common cause of a solitary malignant mass in the liver.

Metastases are the most common malignant hepatic masses. While most are multiple, metastases also represent the most common cause of a solitary malignant mass in the liver.

Most liver metastases originate in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly the colon, and almost all reach the liver via the bloodstream. Other primary sites of metastatic spread to the liver include stomach, pancreas, esophagus, lung, melanoma, and breast.

Most liver metastases originate in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly the colon, and almost all reach the liver via the bloodstream. Other primary sites of metastatic spread to the liver include stomach, pancreas, esophagus, lung, melanoma, and breast. Recognizing liver metastases on CT and MRI:

Recognizing liver metastases on CT and MRI:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (Hepatoma)

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common primary malignancy of the liver. Virtually all arise in livers with preexisting abnormalities such as cirrhosis or hepatitis. Most are solitary, but up to one out of five can be multiple, mimicking metastases. Vascular invasion is common, particularly of the portal system.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common primary malignancy of the liver. Virtually all arise in livers with preexisting abnormalities such as cirrhosis or hepatitis. Most are solitary, but up to one out of five can be multiple, mimicking metastases. Vascular invasion is common, particularly of the portal system. Recognizing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) on CT and MRI:

Recognizing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) on CT and MRI:

Figure 18-32 Diffuse hepatocellular carcinoma of the liver, CT.

There are three patterns of appearance for hepatocellular carcinoma: solitary mass (see Fig. 18-26), multiple nodules and diffuse infiltration throughout a segment, lobe (as in this case), or the entire liver. A, A typical low-attenuation lesion is seen in the right lobe of the liver on the nonenhanced scan (solid white arrow). B, The arterial phase demonstrates patchy enhancement (solid black arrow) indicating the probability of tumor necrosis in the low-attenuation areas. There is ascites present (A). The overall volume of the liver is decreased, and the contour is lobulated from underlying cirrhosis.

Cavernous Hemangiomas

![]() Cavernous hemangiomas are the most common primary liver tumor and second in frequency to metastases for localized liver masses. They are more common in women, are usually solitary and are almost always asymptomatic. They are complex structures composed of multiple, large vascular channels lined by a single layer of endothelial cells.

Cavernous hemangiomas are the most common primary liver tumor and second in frequency to metastases for localized liver masses. They are more common in women, are usually solitary and are almost always asymptomatic. They are complex structures composed of multiple, large vascular channels lined by a single layer of endothelial cells.

Recognizing cavernous hemangiomas of the liver on CT and MRI:

Recognizing cavernous hemangiomas of the liver on CT and MRI:

Figure 18-33 Cavernous hemangioma of the liver, triple-phase CT study.

(A) Cavernous hemangiomas (solid white arrow on all images) are usually hypodense lesions on unenhanced scans. They characteristically enhance from the periphery inward following injection of intravenous contrast during the arterial phase (B) and eventually become isodense. Contrast then tends to be retained within the numerous vascular spaces of the lesion so that it characteristically appears denser than the rest of the liver on delayed scans (C).

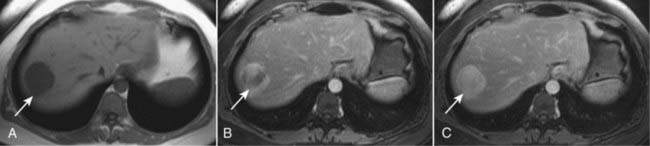

Figure 18-34 Cavernous hemangioma of the liver, MRI.

(A) This image (an axial T1-weighted image) demonstrates a well-circumscribed, slightly lobular dark mass in the right hepatic lobe (solid white arrow in all images). (B) Subsequent images following the administration of intravenous contrast (gadolinium) show peripheral-to-central enhancement, until the entire mass homogeneously enhances on a delayed 10-minute image (C). The combination of this enhancement pattern and the signal characteristics of the lesion allows an unequivocal diagnosis of hemangioma.

Hepatic Cysts

Believed to be congenital in origin, they are easily identified as sharply marginated, spherical lesions of low attenuation (fluid density) compared to the remainder of the liver, on both unenhanced and enhanced CT scans. MRI is much better than CT at characterizing cysts. They are usually solitary and are homogeneous in density (Fig. 18-35).

Believed to be congenital in origin, they are easily identified as sharply marginated, spherical lesions of low attenuation (fluid density) compared to the remainder of the liver, on both unenhanced and enhanced CT scans. MRI is much better than CT at characterizing cysts. They are usually solitary and are homogeneous in density (Fig. 18-35).

Figure 18-35 Hepatic cysts, CT.

Believed to be congenital in origin, hepatic cysts are easily identified as sharply marginated, spherical lesions of low attenuation (fluid density), compared to the remainder of the liver on both unenhanced and enhanced scans (solid black arrows). They are homogeneous in density.

Biliary System: Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

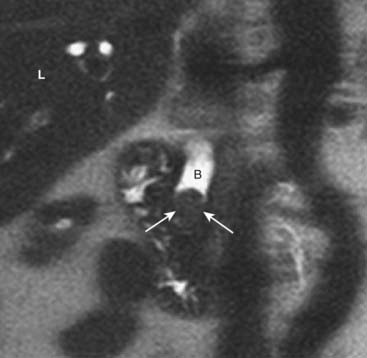

MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) is a noninvasive way to image the biliary tree without requiring injection of contrast material. MRCP utilizes MRI imaging sequences that make fluid-filled structures like the bile ducts, pancreatic ducts and gallbladder extremely bright, and everything else dark. Patients are imaged during a single-breath hold.

MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) is a noninvasive way to image the biliary tree without requiring injection of contrast material. MRCP utilizes MRI imaging sequences that make fluid-filled structures like the bile ducts, pancreatic ducts and gallbladder extremely bright, and everything else dark. Patients are imaged during a single-breath hold. MRCP is excellent at depicting biliary or ductal strictures, ductal dilatation, stones in the bile ducts (choledocholithiasis), gallstones, adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder, choledochal cysts, and pancreas divisum.

MRCP is excellent at depicting biliary or ductal strictures, ductal dilatation, stones in the bile ducts (choledocholithiasis), gallstones, adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder, choledochal cysts, and pancreas divisum. If there is a concern for malignancy (such as pancreatic adenocarcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma) as the cause of pancreaticobiliary ductal dilatation, then additional pulse sequences following the administration of gadolinium can be obtained. Contrast administration allows better detection of malignancy (Fig. 18-36).

If there is a concern for malignancy (such as pancreatic adenocarcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma) as the cause of pancreaticobiliary ductal dilatation, then additional pulse sequences following the administration of gadolinium can be obtained. Contrast administration allows better detection of malignancy (Fig. 18-36).

Figure 18-36 Choledocholithiasis and biliary ductal dilatation on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

This is a coronal close-up of the right upper quadrant utilizing MR imaging. There is a large obstructing gallstone (solid white arrows) in the distal common bile duct (B), which is dilated to 13 mm. Because of the signal characteristics of bile, an MRCP can be done without the need for the injection of contrast. (L = liver.)

Urinary Tract

Kidneys: General Considerations

The kidneys are retroperitoneal organs, encircled by varying amounts of fat and enclosed within a fibrous capsule. So long as they are functioning properly, the kidneys are the route through which intravenously injected, iodinated contrast and gadolinium-based MRI contrast agents are excreted from the body.

The kidneys are retroperitoneal organs, encircled by varying amounts of fat and enclosed within a fibrous capsule. So long as they are functioning properly, the kidneys are the route through which intravenously injected, iodinated contrast and gadolinium-based MRI contrast agents are excreted from the body.Space-Occupying Lesions

Renal Cysts

Simple renal cysts are a very common finding on CT and US scans of the abdomen occurring in more than half of the population over 55 years of age.

Simple renal cysts are a very common finding on CT and US scans of the abdomen occurring in more than half of the population over 55 years of age. Simple cysts are benign, fluid-filled structures which are frequently multiple and bilateral. On CT scans, they tend to have a sharp margin where they meet the normal renal parenchyma. They have density measurements (Hounsfield numbers) of water density (−10 to +20). They do not contrast-enhance (Fig. 18-37A).

Simple cysts are benign, fluid-filled structures which are frequently multiple and bilateral. On CT scans, they tend to have a sharp margin where they meet the normal renal parenchyma. They have density measurements (Hounsfield numbers) of water density (−10 to +20). They do not contrast-enhance (Fig. 18-37A). On ultrasound examinations, simple cysts are echo-free (anechoic) masses with strong through transmission of the ultrasound signal; they have sharp borders where they meet the renal parenchyma and round or oval shapes. Thickening of the wall or dense internal echoes raise suspicion for a malignant lesion (Fig. 18-37B).

On ultrasound examinations, simple cysts are echo-free (anechoic) masses with strong through transmission of the ultrasound signal; they have sharp borders where they meet the renal parenchyma and round or oval shapes. Thickening of the wall or dense internal echoes raise suspicion for a malignant lesion (Fig. 18-37B).

Figure 18-37 Renal cysts, CT urogram and US.

A, This is an image from a CT urogram that demonstrates a low-attenuation mass (solid white arrow) in the upper pole of the right kidney, which is homogeneous in density and sharply marginated. These findings are characteristic of a simple cyst. B, A sagittal ultrasound of the kidney (dotted white arrows) demonstrates an anechoic mass (C) with features consistent with a simple cyst of the lower pole.

Renal Cell Carcinoma (Hypernephroma)

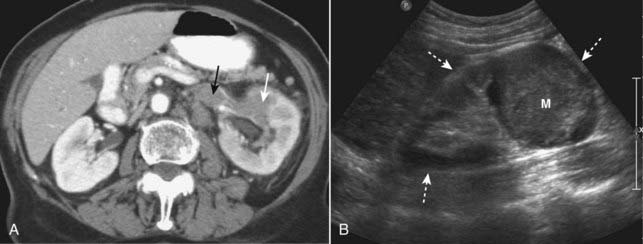

Renal cell carcinoma is the most common primary renal malignancy in adults. Solid masses in the kidneys of adults are usually renal cell carcinomas. They have a propensity for extending into the renal veins, into the inferior vena cava and producing nodules in the lung.

Renal cell carcinoma is the most common primary renal malignancy in adults. Solid masses in the kidneys of adults are usually renal cell carcinomas. They have a propensity for extending into the renal veins, into the inferior vena cava and producing nodules in the lung. A dedicated CT scan for renal cell carcinoma usually consists of images obtained before and after intravenous contrast administration.

A dedicated CT scan for renal cell carcinoma usually consists of images obtained before and after intravenous contrast administration. Ranging from completely solid to completely cystic, renal cell carcinomas are usually solid lesions which may contain low-attenuation areas of necrosis. Even though renal cell carcinomas enhance with intravenous contrast, they still tend to remain lower in density than the surrounding normal kidney.

Ranging from completely solid to completely cystic, renal cell carcinomas are usually solid lesions which may contain low-attenuation areas of necrosis. Even though renal cell carcinomas enhance with intravenous contrast, they still tend to remain lower in density than the surrounding normal kidney. Renal vein invasion occurs in up to one in three cases and may produce filling defects in the lumen of the renal veins (Fig. 18-38A).