CHAPTER 6 Disorders of Growth

CHAPTER 6 Disorders of Growth

The most common reasons for deviant measurements are technical (i.e., faulty equipment and human errors in measurement or plotting). Repeating a deviant measurement should be the first step. Separate growth charts are available for very low birth weight infants (weight <1500 g) and for children of various nationalities and those with Turner syndrome, Down syndrome, achondroplasia, and various other dysmorphology syndromes.

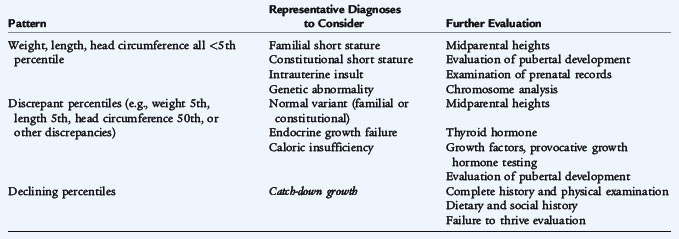

Variability in body proportions occurs from fetal to adult life. Newborns' heads are significantly larger in proportion to the rest of their body. This difference gradually disappears as the child gets older. Differences in body proportions depend on variations in the growth rates of parts of the body or organ systems. Certain growth disturbances result in characteristic changes in the proportional sizes of the trunk, extremities, and head. Patterns requiring further assessment are summarized in Table 6-1.

Evaluating a child over time often elucidates the growth pattern as normal or abnormal. This evaluation of the growth pattern should be coupled with a careful history and physical examination. Parental heights may be useful when deciding whether to observe or proceed with a further evaluation.

For a girl, midparental height is calculated as follows:

For a boy, midparental height is calculated as follows:

Midparental height determination is only a gross approximation. Actual growth depends on too many variables to make an accurate prediction for every child. The growth pattern of a child with low weight, length, and head circumference is commonly associated with familial short stature (see Chapter 173). These children are genetically normal but are smaller than most children. A child who, by age, is preadolescent or adolescent and who starts puberty later than others may have the normal variant called constitutional short stature (see Chapter 173). These children should be examined closely for abnormalities of pubertal development, although most are normal. Girls are considered normal if there is any development of secondary sexual characteristics (e.g., breast budding) on or before the 14th birthday and menarche occur by 16 years of age. Girls who do not start menstruation until 16 years of age usually are smaller than their peers at 12 and 13 years of age. Similar patterns are observed in boys who start puberty later (see Chapter 174).

In many children, growth moves to lower percentiles during their first year of life. These children often start out in high growth percentiles, but between 6 and 18 months they assume a lower percentile until they match their genetic programming, and then begin to grow along new, lower percentiles. They usually do not decrease more than two major percentiles. They have normal developmental, behavioral, and physical examination. These children with catch-down growth should be followed closely, but no further evaluation is warranted.

Children recovering from neonatal illnesses often exhibit catch-up growth. Infants who were born small for gestational age or prematurely ingest more breast milk or formula, unless there are complications that require extra calories, usually catch up in the first six months. Families should be taught to feed these infants on demand and provide as much as they want unless they are vomiting (not just spitting up [see Chapter 128]). Some of these infants may benefit from a higher caloric content formula if they are formula-fed. Many risk factors that may have led to the infant being born small or early are the same psychosocial risks that may contribute to nonorganic failure to thrive (see Chapter 21).

Growth of the nervous system is most rapid in the first 2 years, correlating with increasing physical, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive development. There is rapid change again during adolescence. Osseous maturation (bone age) is determined from radiographs on the basis of the number and size of calcified epiphyseal centers; the size, shape, density, and sharpness of outline of the ends of bones; and the distance separating the epiphyseal center from the zone of provisional calcification.