CHAPTER 27 Diet of the Normal Infant

CHAPTER 27 Diet of the Normal Infant

Infancy, especially the first 6 months, is a period of exceptionally rapid growth and high nutrient requirements relative to body weight (see Chapter 5). If inadequate total intake or inappropriate choice of food occurs, there is risk of rapid deterioration in growth and nutritional status, with potential for adverse consequences on neurocognitive development.

BREASTFEEDING

Human milk is the ideal and uniquely superior food for infants. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends human milk as the sole source of nutrition for the first 6 months of life, with continued intake for the first year and as long as desired thereafter. Breastfeeding offers infants, mothers, and society compelling advantages. Human milk feeding decreases the incidence or severity of diarrhea, respiratory illnesses, otitis media, bacteremia, bacterial meningitis, and necrotizing enterocolitis. Mothers who breastfeed experience a decreased risk of postpartum hemorrhage, longer period of amenorrhea, reduced risk of ovarian and premenopausal breast cancers, and, possibly a reduced risk of osteoporosis. Advantages to society include reduced health care costs because of lower incidence of illness in breastfed infants and reduced employee absenteeism for care attributable to infant illness. Human milk may reduce the incidence of food allergies and eczema. It also contains protective bacterial and viral antibodies (secretory IgA) and nonspecific immune factors, including macrophages and nucleotides, which also help limit infections.

Breastfeeding initiation rates in 2005 were at an all-time high of approximately 74%. However, the number of infants still breastfeeding by 6 months decreased to 43% and was even lower by 1 year (approximately 21%). Breastfeeding rates are lower in several subpopulations of women, especially low-income, minority, and young mothers. Many mothers face obstacles in maintaining lactation because of lack of support from health care professionals and family as well as the need to return to work. Skilled use of a breast pump may help maintain lactation in many circumstances. Primary lactation failure is rare; most women can succeed at breastfeeding if given adequate information and support, especially in the early postpartum period. Multiple excellent resources are readily available at maternity or children’s hospitals, in print, and on the Internet, with guidelines on breastfeeding initiation, positioning, and troubleshooting.

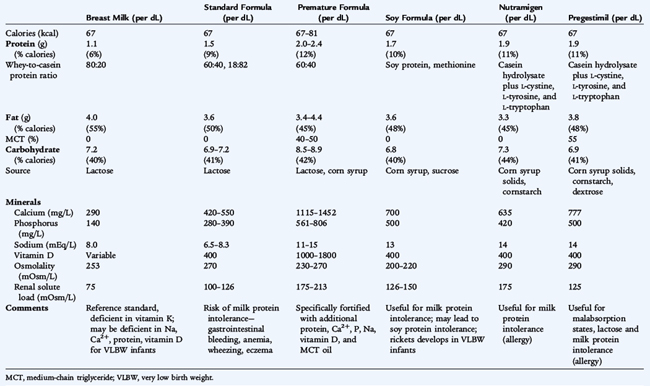

Human milk has several nutritional and non-nutritional advantages over infant formula. The nutrient composition of human milk is summarized and compared with infant formulas in Table 27-1. Outstanding characteristics include the relatively low but highly bioavailable protein content; a generous quantity of essential fatty acids; the presence of long-chain unsaturated fatty acids of the ω-3 series (docosahexaenoic acid is thought to be especially important); a relatively low sodium and solute load; and low but highly bioavailable concentrations of calcium, iron, and zinc, which provide adequate quantities of these nutrients to a normal breastfed infant for approximately 6 months. Breast milk does not need to be warmed, does not require a clean water supply, and is generally free of microorganisms.

Exclusive Breastfeeding

Colostrum, a high-protein, low-fat fluid, is produced in small amounts during the first few postpartum days. It has some nutritional value but primarily has important immunologic and maturational properties. Primiparous women often experience breast engorgement before the milk comes in around the third postpartum day; the breasts become hard and are painful, the nipples become nonprotractile, and the mother’s temperature may increase slightly. Enhancement of milk flow is the best management. If severe engorgement occurs, areolar rigidity may prevent the infant from grasping the nipple and areola. Attention to proper latch-on and hand expression of milk assists in drainage.

Adequacy of milk intake can be assessed by voiding and stooling patterns of the infant. A well-hydrated infant voids six to eight times a day. Each voiding should soak, not merely moisten, a diaper, and urine should be colorless. By 5 to 7 days, loose yellow stools should be passed at least four times a day. Rate of weight gain provides the most objective indicator of adequate milk intake. Total weight loss after birth should not exceed 7%, and birth weight should be regained by 10 days. An infant may be adequately hydrated while not receiving enough milk to achieve adequate energy and nutrient intake. Telephone follow-up is valuable during the interim between discharge and the first physician visit to monitor the progress of lactation. A follow-up visit should be scheduled by 3 to 5 days of age, and again by 2 weeks of age. The mean feeding frequency during the early weeks postpartum is 8 to 12 times per day.

The characteristics of the stools of breastfed infants may alarm parents. Stools are unformed, yellow, and seedy in appearance. Parents commonly think their breastfed infant has diarrhea. Stool frequencies vary; during the first 4 to 6 weeks, breastfed infants tend to produce stool more frequently than formula-fed infants. After 6 to 8 weeks, breastfed infants may go several days without passing a stool.

In the newborn period, elevated concentrations of serum bilirubin are present more often in breastfed infants than in formula-fed infants (see Chapter 62). Feeding frequency during the first 3 days of life of breastfed infants is inversely related to the level of bilirubin; frequent feedings stimulate meconium passage and excretion of bilirubin in the stool. Infants who have insufficient milk intake and poor weight gain in the first week of life may have an increase in unconjugated bilirubin secondary to an exaggerated enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin. This is known as breastfeeding jaundice. Attention should be directed toward improved milk production and intake. The use of water supplements in breastfed infants has no effect on bilirubin levels and is not recommended. After the first week of life in a breastfed infant, prolonged elevated serum bilirubin may be due to presence of an unknown factor in milk that enhances intestinal absorption of bilirubin. This is termed breast milk jaundice, which is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be made only if an infant is otherwise thriving, with normal growth and no evidence of hemolysis, infection, biliary atresia, or metabolic disease (see Chapter 62). Breast milk jaundice usually lasts no more than 1 to 2 weeks. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vitamin D supplementation (400 IU/day starting soon after birth), and, when needed, fluoride after 6 months for breastfed infants.

Common Breastfeeding Problems

Breast tenderness, engorgement, and cracked nipples are the most common problems encountered by breastfeeding mothers. Engorgement, one of the most common causes of lactation failure, should receive prompt attention because milk supply can decrease quickly if the breasts are not adequately emptied. Applying warm or cold compresses to the breasts before nursing and hand expression or pumping of some milk can provide relief to the mother and make the areola easier to grasp by the infant. Nipple tenderness requires attention to proper latch-on and positioning of the infant. Supportive measures include nursing for shorter periods, beginning feedings on the less sore side, air drying the nipples well after nursing, and applying lanolin cream after each nursing session. Severe nipple pain and cracking usually indicate improper latch-on. Temporary pumping, which is well tolerated, may be needed. Meeting with a lactation consultant may help minimize these problems and allow the successful continuation of breastfeeding.

If a lactating woman reports fever, chills, and malaise, mastitis should be considered. Treatment includes frequent and complete emptying of the breast and antibiotics. Breastfeeding usually should not be stopped, because the mother’s mastitis commonly has no adverse effects on the breastfed infant. Untreated mastitis may also progress to a breast abscess. If an abscess is diagnosed, treatment includes incision and drainage, antibiotics, and regular emptying of the breast. Nursing from the contralateral breast can be continued with a healthy infant. If maternal comfort allows, nursing can continue on the affected side.

Maternal infection with human immunodeficiency virus is considered a contraindication for breastfeeding in developed countries. When the mother has active tuberculosis, syphilis, or varicella, restarting breastfeeding may be considered after therapy is initiated. If a woman has herpetic lesions on her breast, nursing and contact with the infant on that breast should be avoided. Women with genital herpes can breastfeed. Proper handwashing procedures should be stressed. Galactosemia in the infant also is a contraindication to breastfeeding.

Maternal Drug Use

Any drug prescribed therapeutically to newborns usually can be consumed via breast milk without ill effect. The factors that determine the effects of maternal drug therapy on the nursing infant include the route of administration, dosage, molecular weight, pH, and protein binding. Few therapeutic drugs are absolutely contraindicated; these include radioactive compounds, antimetabolites, lithium, and certain antithyroid drugs. The mother should be advised against the use of unprescribed drugs, including alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, or street drugs.

Maternal use of illicit or recreational drugs is a contraindication to breastfeeding. If a woman is unable to discontinue drug use, she should not breastfeed. Expression of milk for a feeding or two after use of a drug is not acceptable. Breastfed infants of mothers taking methadone (but no alcohol or other drugs) as part of a treatment program generally have not experienced ill effects.

FORMULA FEEDING

Cow’s Milk–Based Formulas

The alternative to human milk is iron-fortified formula, which permits adequate growth of most infants and is formulated to mimic human milk. No vitamin or mineral supplements (other than possibly fluoride after 6 months) are needed with such formulas. Cow’s milk formulas (see Table 27-1; Table 27-2) are composed of reconstituted, skimmed cow’s milk or a mixture of skimmed cow’s milk and electrolyte-depleted cow’s milk whey or casein proteins. The fat used in infant formulas is a mixture of vegetable oils, commonly including soy, palm, coconut, corn, oleo, or safflower oils. The carbohydrate is generally lactose, although lactose-free cow’s milk–based formulas are available. The caloric density of formulas is 20 kcal/oz (0.67 kcal/mL), similar to that of human milk. Formula-fed infants often gain weight more rapidly than breastfed infants, especially after the first 3 to 4 months of life. Formula-fed infants are at higher risk for obesity later in childhood; this may be related to differences in feeding practices for formula-fed infants compared with breastfed infants. Cow’s milk–based infant formulas are used as substitutes for breast milk for infants whose mothers choose not to or cannot breastfeed or as supplements for breastfeeding. Nondairy milk substitutes such as rice or nut milks are inappropriate to feed to infants and can result in severe nutritional deficiencies. Human milk fortifiers, which when mixed with breast milk boost the caloric (24 kcal/oz) and nutrient content, also are available for use with premature infants when adequate growth cannot be achieved with human milk alone.

TABLE 27-2 Infant Feedings and Standard and Specialized Formulas

| Formula Category | Example Formulas | Features and Typical Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Human milk | ||

| Cow’s milk–based (with lactose) | Standard substitute for breast milk | |

| Cow’s milk–based (without lactose) | Useful for transient lactase deficiency or lactose intolerance | |

| Soy protein–based/lactose-free | ||

| Premature formula: cow’s milk (reduced lactose) | ||

| Predigested | Casein hydrolysate, useful for protein allergies and malabsorptive disorders | |

| Elemental | Free amino acids for severe protein allergy; malabsorption | |

| Premature transitional | Standard at 22 kcal/oz, intermediate in protein and micronutrients to promote growth postdischarge | |

| Fat modified | High MCT, useful for chylous effusions and for some malabsorptive disorders | |

| Prethickened | Enfamil AR | May be useful for dysphagia, mild GER |

| Carbohydrate intolerance | All monosaccharides and disaccharides removed; can titrate dextrose or fructose additives to tolerance |

GER, gastroesophageal reflux; LBW, low birth weight; MCT, medium-chain triglyceride.

Soy Formulas

Soy protein–based formulas provide a nutritionally safe alternative to cow’s milk–based formulas when intolerance occurs from immune reactions to cow’s milk proteins. However, a proportion of infants allergic to cow’s milk protein also are allergic to soy protein. The soy protein is supplemented with methionine to improve its nutritional qualities. The carbohydrates in soy formulas are glucose oligomers (smaller molecular weight corn starches) and, sometimes, sucrose. The fat mixture is similar to that used in cow’s milk formulas. Caloric density is the same as for cow’s milk formulas.

Soy protein formulas do not prevent the development of allergic disorders in later life. Clinical intolerance to soy protein or cow’s milk protein occurs with similar frequency. Soy protein formulas can be recommended for use by vegetarian families and in the management of galactosemia and primary and secondary lactose intolerance. Soy formulas should not be used indiscriminately to “treat” poorly evaluated patients with colic, formula intolerance, or more serious diseases. Soy protein–based formulas are not recommended for premature infants with birth weights less than 1800 g.

Therapeutic Formulas

The composition of specialized infant and pediatric formulas is modified to meet specific therapeutic requirements (see Table 27-2; Table 27-3). Therapeutic formulas are designed to treat digestive and absorptive insufficiency or protein hypersensitivity. Semi-elemental formulas include protein hydrolysate formulas, the major nitrogen source of which is a casein or whey hydrolysate, supplemented with selected amino acids. These formulas contain an abundance of essential fatty acids from vegetable oil. Certain brands also provide substantial amounts (25% to 50% of total fat) of medium-chain triglycerides, which are water soluble and are more easily absorbed than long-chain fatty acids; this is a useful feature for patients with malabsorption resulting from such conditions as short gut syndrome, intestinal mucosal atrophy or injury, chronic diarrhea, or cholestasis. Elemental formulas also are available that contain synthetic free amino acids and varying quantities and types of fat components. These are especially designed for patients with protein allergy or sensitivity. The carbohydrate content of these specialized formulas varies, but all are lactose free; some contain glucose oligomers and soluble starches.

TABLE 27-3 Pediatric Enteral Formulas

| Formula Category | Formula Examples | Typical Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Standard, milk protein–based | Nutritionally complete for ages 1 to 10. Can be used for tube feeds or oral supplements | |

| Food-based | Compleat Pediatric | Made with beef protein, fruits, and vegetables—contains lactose. Fortified with vitamins/minerals |

| Semi-elemental | Peptamen Jr. | Indicated for impaired gut function with peptides as protein source, high MCT content with lower total fat percentage than standard pediatric formulas |

| Elemental | Indicated for impaired gut function or protein allergy, contains free amino acids. Lower fat, with most as MCT |

MCT, medium-chain triglyceride.

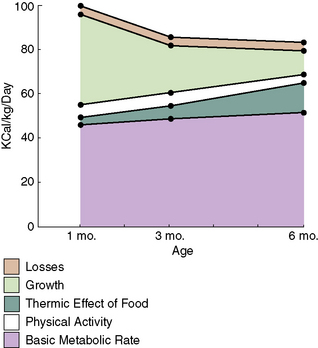

COMPLEMENTARY FOODS AND WEANING

By approximately 6 months, complementary feeding of semisolid foods is suggested. By this age, an exclusively breastfed infant requires additional sources of several nutrients, including protein, iron, and zinc. If the introduction of solid foods is delayed, nutritional deficiencies can develop, and oral sensory issues (texture and oral aversion) may occur. General signs of readiness include the ability to hold the head up and sit unassisted, bringing objects to the mouth, showing interest in foods, and the ability to track a spoon and open the mouth. Although the growth rate of the infant is decreasing, energy needs for activity increase (Fig. 27-1). A relatively high-fat and calorically dense diet (human milk or formula) is needed to deliver adequate calories. The choice of foods to meet micronutrient needs is less critical for formula-fed infants because of the nutrient fortification of formula. The exposure to different textures and the process of self-feeding are important developmental experiences for formula-fed infants.

FIGURE 27-1 Energy requirements of infants.

(From Waterlow JC: Basic concepts in the determination of nutritional requirements of normal infants. In Tsang RC, Nichols BL, editors: Nutrition during infancy. Philadelphia, 1988, Hanley & Belfus.)

Commercially prepared or homemade foods help meet the nutritional needs of the infant. Because infant foods are usually less energy dense than human milk and formula, they generally should not be used in young infants to compensate for inadequate intake from breastfeeding or formula. Oropharyngeal coordination is immature before 3 months, making feeding with solid foods difficult. Vitamin-fortified and iron-fortified dry cereals are often used as a source of calories and micronutrients (particularly iron) to supplement the diet of infants whose needs for these nutrients are not met by human milk after about 6 months of age. Cereals commonly are mixed with breast milk, formula, or water and later with fruits. To help identify possible allergies or food intolerances that may arise when new foods are added to the diet, single-grain cereals (rice, oatmeal, barley) are recommended as starting cereals. New single-ingredient foods generally can be offered approximately every week. Mixed cereal (oat, corn, wheat, and soy) provides greater variety to older infants.

Puréed fruits, vegetables, and meats are available in containers that provide an appropriate serving size for infants. By approximately 6 months, the infant’s gastrointestinal tract is mature, and the order of introducing complementary foods is not critical. Introduction of single-ingredient meats (versus combination dinners) as an early complementary food provides an excellent source of bioavailable iron and zinc, both of which are important for the older breastfed infant. Parents who prefer to make homemade infant foods using a food processor or food mill should be encouraged to practice safe food handling techniques and avoid flavor additives such as salt. If juice is given, it should be started only after 6 months of age, be given in a cup (as opposed to a bottle), and limited to 4 oz daily. An infant should never be put to sleep with a bottle or sippy cup filled with milk, formula, or juice, because this can result in infant bottle tooth decay (see Chapter 127). Foods with high allergic potential that should be avoided during infancy, especially for infants with a strong family history of food allergy, include fish, peanuts, tree nuts, dairy products, and eggs. Hot dogs, grapes, popcorn, and nuts present a risk of aspiration and airway obstruction. All foods with the potential to obstruct the young infant’s airway should be cut into sizes smaller than an infant’s main airway. In general, such foods should be avoided until 4 years of age or older. Honey (risk of infant botulism) should not be given before 1 year of age.