CHAPTER 122 Zoonoses

CHAPTER 122 Zoonoses

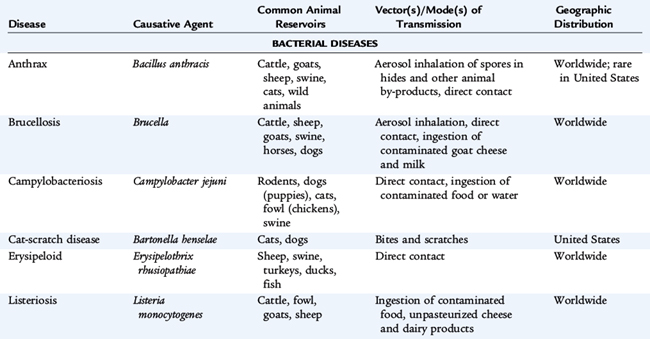

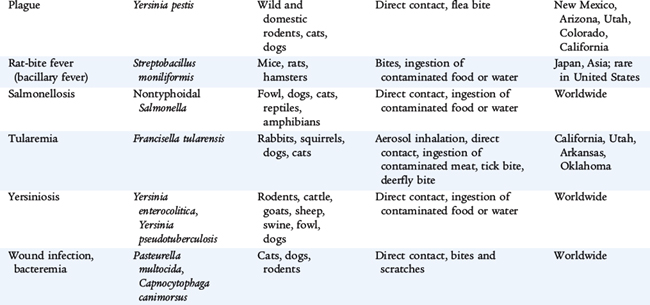

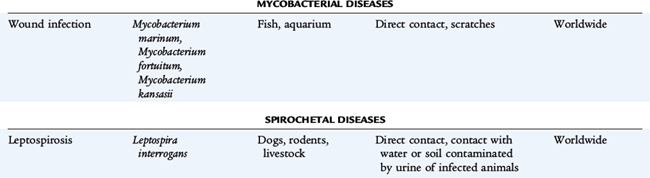

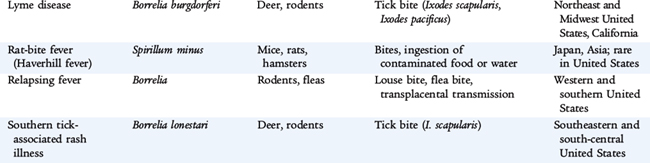

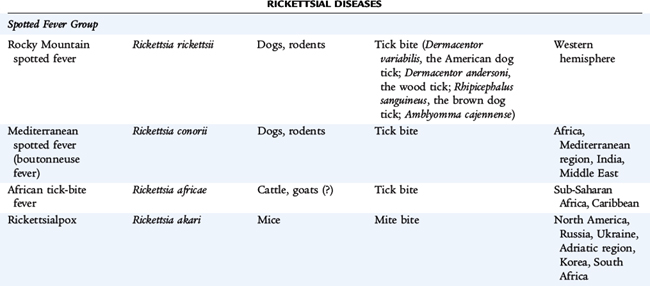

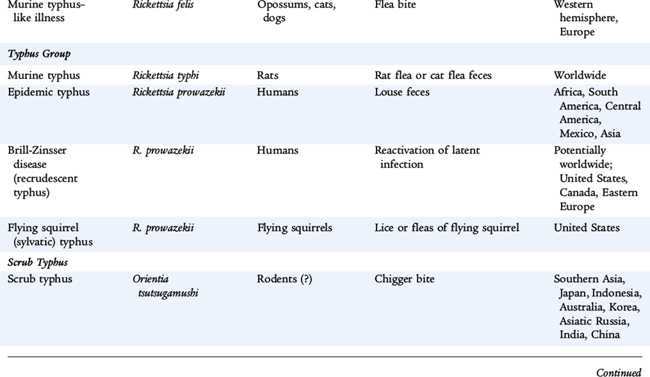

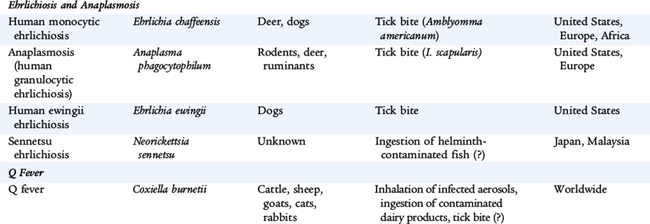

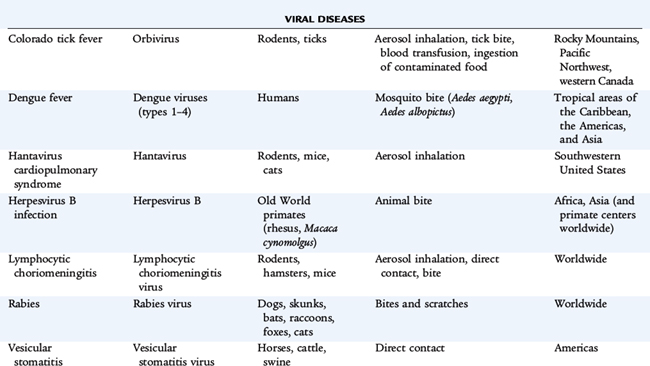

Zoonoses are infections that are transmitted in nature between vertebrate animals and humans. Many zoonotic pathogens are maintained in nature by means of an enzootic cycle, in which mammalian hosts and arthropod vectors reinfect each other. Humans frequently are only incidentally infected. Of the more than 150 different human zoonotic diseases that have been described, Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) accounts for 90% of reported vector-borne infections in the United States. Other common pathogens include Rickettsia rickettsii (Rocky Mountain spotted fever), ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia chaffeensis), West Nile virus, and anaplasmosis (Anaplasma phagocytophilum). The epidemiology of zoonoses is related to the geographic distribution of the hosts and, if vector-borne, the distribution and seasonal life cycle of the vector (Table 122-1).

Many zoonoses are spread by ticks including Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrlichiosis, tularemia, tick typhus, and babesiosis. Mosquitoes transmit the arboviral encephalitides (see Chapter 101), dengue fever, malaria, and yellow fever. Preventive measures to avoid tick-borne and mosquito-borne diseases include using insect repellants that contain DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) on skin and insect repellants that contain permethrin on clothing; avoiding tick-infested habitats (thick scrub oak, briar, poison ivy sites); avoiding excretory products of wild animals; wearing shoes or boots and not sandals; completely covering the arms and legs, with trousers tucked into shoes or socks to prevent ticks from crawling under clothing; wearing light-colored clothing to facilitate detection of crawling ticks; conducting thorough inspections of the body and of pets after returning from the outdoors; and removing ticks promptly.

Ticks are best removed using blunt forceps or tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible to pull the tick steadily outward. Squeezing, twisting, or crushing the tick should be avoided because the tick’s bloated abdomen can act like a syringe if squeezed. Transmission of infection seems to be most efficient after 30 to 36 hours of nymphal tick attachment for human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, after 36 to 48 hours for B. burgdorferi, and after 56 to 60 hours for Babesia. Prophylactic antimicrobial therapy after a tick bite or exposure is not recommended.

LYME DISEASE (Borrelia burgdorferi)

Etiology

Lyme disease is a tick-borne infection caused by the spirochete, B. burgdorferi. The vector in the eastern and midwestern United States is Ixodes scapularis, the black-legged tick that is commonly known as the deer tick. The vector on the Pacific Coast is Ixodes pacificus, the western black-legged tick. Ticks usually become infected by feeding on the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus), which is a natural reservoir for B. burgdorferi. The larvae are dormant over winter and emerge the following spring in the nymphal stage, which is the stage of the tick that is most likely to transmit the infection to humans.

Epidemiology

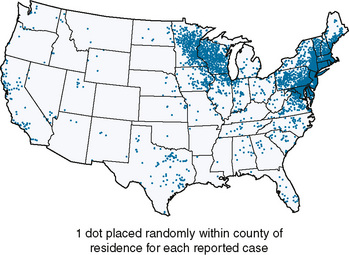

Over 20,000 cases are reported annually in the United States, with 95% of cases reported from New England and the eastern parts of the Middle Atlantic states and the upper Midwest; with a small endemic focus along the Pacific coast (Fig. 122-1). In Europe, most cases occur in Scandinavian countries and central Europe. Because exposure to ticks is more common in warm months, Lyme disease is noted predominantly in summer. The incidence is highest among children 5 to 10 years old, at almost twice the incidence among adolescents and adults.

FIGURE 122-1 The geographic distribution of 28,921 confirmed cases of Lyme disease in the United States in 2008. The risk for acquiring Lyme disease varies by the distribution of Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus, the proportion of infected ticks for each species at each stage of the tick’s life cycle, and the presence of grassy or wooded locations favored by white-tailed deer.

(From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Lyme Disease—United States, 2008, available from the CDC website: www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/Lyme/ld_Incidence.htm.)

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations are divided into early and late stages. Early infection may be localized or disseminated. Early localized disease develops 7 to 14 days after a tick bite as the site forms an erythematous papule that expands to form a red, raised border, often with central clearing. The lesion, erythema migrans, harbors B. burgdorferi and may be 15 cm wide, pruritic, or painful. Systemic manifestations may include malaise, lethargy, fever, headache, arthralgias, stiff neck, myalgias, and lymphadenopathy. The skin lesions and early manifestations resolve without treatment over 2 to 4 weeks. Not all patients with Lyme disease recall a tick bite or develop erythema migrans.

Approximately 20% of patients develop early disseminated disease with multiple secondary skin lesions, aseptic meningitis, pseudotumor, papilledema, cranioneuropathies including Bell palsy, polyradiculitis, peripheral neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, or transverse myelitis. Carditis with various degrees of heart block rarely may develop during this stage. Neurologic manifestations usually resolve by 3 months, but may recur or become chronic.

Late disease begins weeks to months after infection. Arthritis is the usual manifestation and may develop in 50% to 60% of untreated patients. The male-female ratio is 7:1. The knee is involved in greater than 90% of cases, but any joint may be affected. Symptoms may resolve over 1 to 2 weeks, but often recur in other joints. If untreated, most cases resolve, but chronic erosive arthritis persists in 10% of patients as the episodes increase in duration and severity. Cardiac abnormalities occur in approximately 10% of untreated patients. Neuroborreliosis, the late manifestations of Lyme disease involving the central nervous system (CNS), is rarely reported in children.

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

Antibody tests during early, localized Lyme disease may be negative and are not useful. The diagnosis of late disease is confirmed by serologic tests specific for B. burgdorferi. The sensitivity and specificity of serologic tests for Lyme disease vary substantially. A positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or immunofluorescence assay result must be confirmed by immunoblot showing antibodies against at least either two to three (for IgM) or five (for IgG) proteins of B. burgdorferi (at least one of which is one of the more specific, low-molecular-weight, outer-surface proteins).

In late disease, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is elevated and complement may be reduced. The joint fluid shows an inflammatory response with total white blood cell (WBC) count of 25,000 to 125,000 cells/mm3, often with a polymorphonuclear predominance (see Table 118-1). The rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody are negative, but the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test may be falsely positive. With CNS involvement, the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shows a lymphocytic pleocytosis with normal glucose and slightly elevated protein.

Differential Diagnosis

A history of a tick bite and the classic rash are helpful, but are not always present. Erythema migrans of early, localized disease may be confused with nummular eczema, tinea corporis, granuloma annulare, an insect bite, or cellulitis. Southern tick-associated rash illness, which is similar to erythema migrans, has been described in southeastern and south-central states and is associated with the bite of Amblyomma americanum, the lone star tick. A spirochete that has been named Borrelia lonestari has been detected by DNA analysis, but has not yet been cultured.

During early, disseminated Lyme disease, multiple lesions may appear as erythema multiforme or urticaria. The aseptic meningitis is similar to viral meningitis, and the seventh nerve palsy is indistinguishable from herpetic or idiopathic Bell palsy. Lyme carditis is similar to viral myocarditis. Monarticular or pauciarticular arthritis of late Lyme disease may mimic suppurative arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or rheumatic fever (see Chapter 89). The differential diagnosis of neuroborreliosis includes degenerative neurologic illness, encephalitis, and depression.

Treatment

Early, localized disease and early, disseminated disease, including facial nerve palsy (or other cranial nerve palsy) and carditis with first-degree or second-degree heart block, is treated with doxycycline or amoxicillin for 14 to 21 days. Early disease with carditis with third-degree heart block or meningitis and late neurologic disease (other than facial nerve or other cranial nerve palsy) are treated with intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) ceftriaxone or IV penicillin G for 14 to 28 days. Arthritis is treated with doxycycline (for children >9 years of age) or amoxicillin for 28 days. If there is recurrence, treatment should be with a repeated oral regimen or with the regimen for late neurologic disease.

Complications and Prognosis

Carditis, especially conduction disturbances, and arthritis are the major complications of Lyme disease. Even untreated, most cases eventually resolve without sequelae.

Lyme disease is readily treatable and curable. The long-term prognosis is excellent for early and late disease. Early treatment may prevent progression to carditis and meningitis. Recurrences of arthritis are rare after recommended treatment. A community-based study of children with Lyme disease found no evidence of impairment 4 to 11 years later.

Prevention

Measures to minimize exposure to tick-borne diseases are the most reasonable means of preventing Lyme disease. Postexposure prophylaxis is not routinely recommended because the overall risk of acquiring Lyme disease after a tick bite is only 1% to 2% even in endemic areas, and treatment of the infection, if it develops, is highly effective. Nymphal stage ticks must feed for 36 to 48 hours, and adult ticks must feed for 48 to 72 hours before the risk of transmission of B. burgdorferi from infected ticks becomes substantial. In hyperendemic regions, prophylaxis of adults with doxycycline, 200 mg as a single dose, within 72 hours of a nymphal tick bite is effective in preventing Lyme disease.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN SPOTTED FEVER (Rickettsia rickettsii)

Etiology

The cause of Rocky Mountain spotted fever is R. rickettsii, gram-negative coccobacillary organisms that resemble bacteria but have incomplete cell walls and require an intracellular site for replication. The organism invades and proliferates within the endothelial cells of blood vessels causing vasculitis and resulting in increased vascular permeability, edema, and, eventually, decreased vascular volume, altered tissue perfusion, and widespread organ failure. Many tick species are capable of transmitting R. rickettsii. The principal ticks are the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) in the eastern United States and Canada, the wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) in the western United States and Canada, the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) in Mexico, and Amblyomma cajennense in Central and South America.

Epidemiology

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is the most common rickettsial illness in the United States, occurring primarily in the eastern coastal, southeastern, and western states. Most cases occur from May to October after outdoor activity in wooded areas, with peak incidence among children 1 to 14 years of age. Approximately 40% of infected persons are unable to recall a tick bite.

Clinical Manifestations

The incubation period of Rocky Mountain spotted fever is 2 to 14 days, with an average of 7 days. The onset is nonspecific with headache, malaise, and fever. A pale, rose-red macular or maculopapular rash appears in 90% of cases. The rash begins peripherally and spreads to involve the entire body, including palms and soles. The early rash blanches on pressure and is accentuated by warmth. It progresses over hours or days to a petechial and purpuric eruption that appears first on the feet and ankles, then the wrists and hands, and progresses centripetally to the trunk and head. Myalgias, especially of the lower extremities, and intractable headaches are common. Severe cases progress with splenomegaly, myocarditis, renal impairment, pneumonitis, and shock.

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

Thrombocytopenia (usually <100,000 cells/mm3), anemia, hyponatremia, and elevated hepatic transaminase levels are common laboratory findings. Organisms can be detected in skin biopsy specimens by fluorescent antibodies, although this test is not widely available. Serologic testing is used to confirm the diagnosis, although treatment is begun before confirmation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes meningococcemia, bacterial sepsis, toxic shock syndrome, leptospirosis, ehrlichiosis, measles, enteroviruses, infectious mononucleosis, collagen vascular diseases, Schönlein-Henoch purpura, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. The diagnosis of Rocky Mountain spotted fever should be suspected with fever and petechial rash, especially with a history of a tick bite or outdoor activities during spring and summer in endemic regions. Fever, headache, and myalgias lasting more than 1 week in patients in endemic areas indicate Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Delayed diagnosis and late treatment usually result from atypical initial symptoms and late appearance of the rash.

Treatment

Therapy for suspected Rocky Mountain spotted fever should not be postponed pending results of diagnostic tests. Doxycycline is the drug of choice, even for young children despite the theoretical risk of dental staining in children younger than 9 years of age. Fluoroquinolones also are active against R. rickettsii and may be an alternative treatment for adults.

Complications and Prognosis

In severe infections, capillary leakage results in noncardiogenic pulmonary edema (acute respiratory distress syndrome), hypotension, disseminated intravascular coagulation, circulatory collapse, and multiple organ failure including encephalitis, myocarditis, hepatitis, and renal failure.

Untreated illness may persist for 3 weeks before progressing to multisystem involvement. The mortality rate is 25% without treatment, which is reduced to 3.4% with treatment. Permanent sequelae are common after severe disease.

EHRLICHIOSIS (Ehrlichia chaffeensis) AND ANAPLASMOSIS (Anaplasma phagocytophilum)

Etiology

The term ehrlichiosis often is used to refer to all forms of infection with Ehrlichia. Human monocytic ehrlichiosis is caused by E. chaffeensis, which infects predominantly monocytic cells and is transmitted by the tick A. americanum. Human anaplasmosis, formerly named granulocytic ehrlichiosis, is caused by A. phagocytophilum and is transmitted by the tick I. scapularis. Disease caused by Ehrlichia ewingii has been identified by various names, including ehrlichiosis ewingii.

Epidemiology

Ehrlichiosis occurs commonly in the United States. Human monocytic ehrlichiosis occurs in broad areas across the southeastern, south central, and mid-Atlantic United States in a distribution that parallels that of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Anaplasmosis is the most frequently recognized ehrlichiosis and is found mostly in the northeastern and upper midwestern United States, but infections have now been identified in northern California, the mid-Atlantic states, and broadly across Europe.

Clinical Manifestations

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis, anaplasmosis, and ehrlichiosis ewingii cause similar acute febrile illness characterized by fever, malaise, headache, myalgias, anorexia, and nausea, but often without a rash. In contrast to adult patients, nearly two thirds of children with human monocytic ehrlichiosis present with a macular or maculopapular rash, although petechial lesions may occur. Symptoms usually last for 4 to 12 days.

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

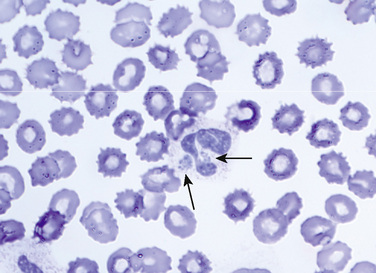

Characteristic laboratory findings include leukopenia, lymphocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and elevated hepatic transaminases. Morulae are found infrequently in circulating monocytes of persons with human monocytic ehrlichiosis, but are found in 40% of circulating neutrophils in 20% to 60% of persons with anaplasmosis (Fig. 122-2). Seroconversion or fourfold rise in antibody titer confirms the diagnosis.

FIGURE 122-2 A morula (arrowhead) containing Anaplasma phagocytophilum in a neutrophil. Ehrlichia chaffeensis and A. phagocytophilum have similar morphologies but are serologically and genetically distinct. (Wright stain, original magnification ×1200.)

(From Walker DH, Dumler JS: Ehrlichia chaffeensis (human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis), and other ehrlichieae. In Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R [eds]: Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 6th ed. Philadelphia, Churchill Livingstone, 2005; Fig. 190-2, p 2315.)

Differential Diagnosis

Ehrlichiosis is clinically similar to other arthropod-borne infections, including Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia, babesiosis, early Lyme disease, murine typhus, relapsing fever, and Colorado tick fever. The differential diagnosis also includes infectious mononucleosis, Kawasaki disease, endocarditis, viral infections, hepatitis, leptospirosis, Q fever, collagen vascular diseases, and leukemia.

Treatment

As with Rocky Mountain spotted fever, therapy for suspected ehrlichiosis should not be postponed pending results of diagnostic tests. Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are treated with tetracyclines, primarily doxycycline.