Chapter 7 Appendix

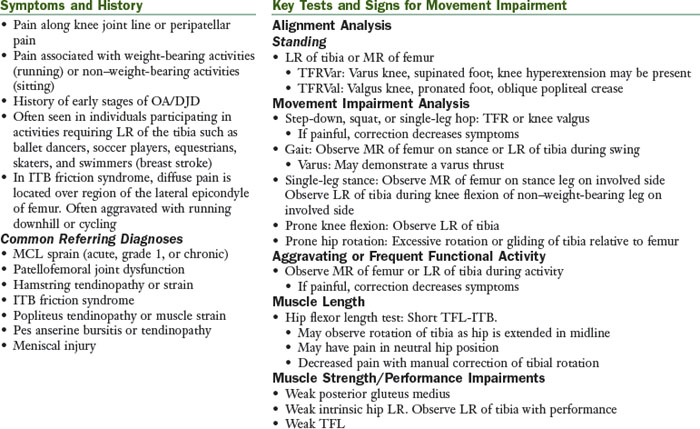

Tibiofemoral Rotation Syndrome

The principal movement impairment in tibiofemoral rotation (TFR) syndrome is knee joint pain associated with impaired rotation of the tibiofemoral joint (lateral rotation of the tibia and/or medial rotation of the femur). Correction of impairment often decreases symptoms. The subcategories of TFR syndrome are TFR with valgus (TFRVal) syndrome: Valgus knee during static/dynamic activities and TFR with varus (TFRVar) syndrome: Varus knee during static/dynamic activities.

Treatment

Emphasis of treatment is decreasing excessive rotation between the tibia on the femur.

Patient Education

The goal of patient education is correction of impaired postural habits and movements.

Home Exercise Program

Patients should be instructed that they should not feel an increase in their symptoms during the performance of their exercises. In addition to monitoring for symptoms, they should not experience a “pressure” in the knee during exercises. If either pain or pressure occurs, they should review the instructions to the exercise to be sure that they are performing it correctly and try again. If they still experience pain or pressure, they should discontinue this exercise until they return for their next visit.

SPECIAL NOTE: Knees with Malalignment or Excessive Varus or Valgus

It is thought that the quadriceps muscles provide some shock absorption to the knee; however, recent studies show that increased quadriceps activity can actually increase the progression of OA in knees with malalignment. One must consider the compression forces that the quadriceps can add to a joint before administering quadriceps strengthening activities. Quadriceps performance should be enhanced only through the proper performance of functional activities, and therapeutic exercises to hypertrophy the quadriceps should be avoided in patients with malalignment of the knees.

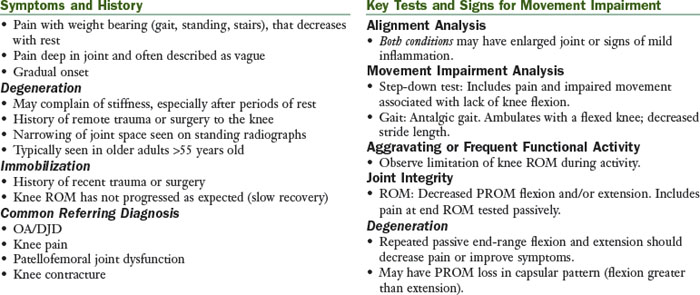

Tibiofemoral Hypomobility Syndrome

The principal movement impairment in tibiofemoral hypomobility (TFHypo) syndrome is associated with a limitation in the physiological motion of the knee. This limitation may result from degenerative changes in the joint or the effects of prolonged immobilization. In type I TFHypo syndrome, the potential for recovery of ROM is good; whereas the potential for recovery in type II TFHypo syndrome is poor.

Treatment

Type I Tibiofemoral Hypomobility Syndrome

The potential for recovery of ROM is good in patients with type I TFHypo syndrome. These individuals demonstrate a limitation in ROM; however, duration of limitation is not long. End-feel to PROM may be stiff: however, some extensibility is noted. The therapist should monitor progression of ROM over time to determine if the classification of type I is appropriate. If ROM does not improve in 3 to 4 weeks and all treatment strategies have been investigated, type II should be considered.

Treatment emphasis is on improving ROM, strength, and conditioning, without increasing pain and swelling. In the treatment of the knee with degeneration, consider that rotation may be contributing to the symptoms.

Patient Education

The goal of patient education is correction of impaired postural habits and movements.

Home Exercise Program

Degeneration

Patients should be instructed that they should not feel an increase in their symptoms during the performance of their exercises. In addition to monitoring for their symptoms, they should not experience a “pressure” in their knee during their exercises. If either pain or pressure occurs, they should review the instructions to the exercise to be sure that they are performing it correctly and try again. If they still experience pain or pressure, they should discontinue this exercise until they return for their next visit.

Immobilization

Patients should be instructed that they will experience some discomfort (often described as pain or pressure) with their exercises to improve ROM. Patients should be encouraged to continue with the exercises as tolerated. Pain medications should be timed so that they are at maximum level during exercises.

Knees with Degenerative Changes and Malalignment, Excessive Varus or Valgus

It is thought that the quadriceps muscles provide some shock absorption to the knee; however, recent studies show that increased quadriceps strength can actually increase the progression of OA in knees that have malalignment. One must consider the compression forces that the quadriceps can add to a joint before administering quadriceps strengthening activities. The quadriceps performance should be enhanced only through the proper performance of functional activities, and therapeutic exercises to hypertrophy the quadriceps should be avoided in patients with malalignment of the knees.

Type II Tibiofemoral Hypomobility Syndrome

The potential for recovery of ROM is poor in patients with type II TFHypo syndrome. These individuals may report a long duration of loss of ROM, either through immobilization or long-standing OA. End-feel to PROM to the joint are very stiff, with the soft tissues demonstrating very little extensibility. When in doubt, it is best to classify the individual with type I for a trial period and assess the patient’s progress appropriately. Emphasis is on educating the patient in modifications of functional activities to accommodate for loss of ROM.

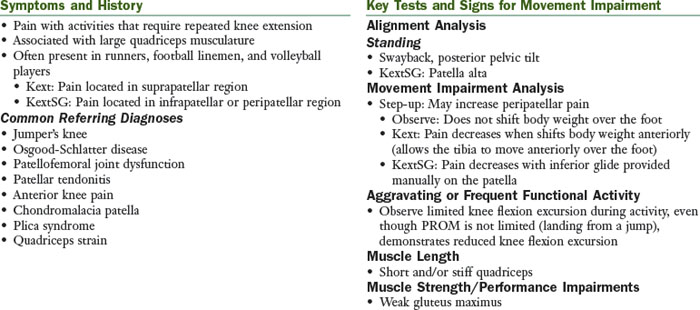

Knee Extension Syndrome and Knee Extension with Patellar Superior Glide Syndrome

The principal movement impairment in knee extension (Kext) syndrome is knee pain associated with dominance of quadriceps muscles that results in excessive pull on the patella, patellar tendon/ligament, or tibial tubercle. The Kext syndrome has a subcategory of patellar superior glide (KextSG).

Treatment

Treatment emphasis in Kext syndrome is on decreasing the activity of the quadriceps while improving the performance of the hip extensors. In KextSG syndrome, treatment emphasis is similar to Kext syndrome; however, methods to stabilize the patellar glide may need to be implemented.

Patient Education

The following treatment is appropriate for both Kext and KextSG syndromes unless otherwise noted. The goal of patient education is correction of impaired postural habits and movements.

Home Exercise Program

The patient should be instructed that they should not feel an increase in their symptoms during the performance of their exercises. If this occurs, they should review the instructions to the exercise to be sure that they are performing it correctly and try again. If they still experience pain, they should discontinue this exercise until they return for their next visit.

Knee Hyperextension Syndrome

The principal movement impairment in knee hyperextension (Khext) syndrome is knee pain associated with impaired knee extensor mechanism. Dominance of hamstrings and poor functional performance of gluteus maximus and quadriceps muscles result in hyperextension of the knee placing excessive stresses on the structures of the knee.

Treatment

Treatment emphasis in knee hyperextension syndrome is to decrease hyperextension of the knee.

Patient Education

The goal of patient education is correction of impaired postural habits and movements.

Home Exercise Program

Patients should be instructed that they should not feel an increase in their symptoms during the performance of their exercises. If this occurs, they should review the instructions to the exercise to be sure that they are performing it correctly and try again. If they still experience pain, they should discontinue this exercise until they return for their next visit.

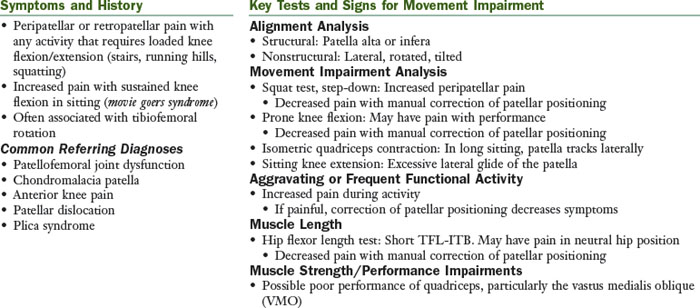

Patellar Lateral Glide Syndrome

The principal movement impairment in patellar lateral glide syndrome is knee pain as a result of an impaired patellar relationship within the trochlear groove. Often a secondary diagnosis and therefore the movement impairments of tibiofemoral rotation (TFR) or knee hyperextension (Khext) should be considered. Correction of impairment often decreases symptoms.

Treatment

Treatment emphasis in patellar lateral glide syndrome is to address the impairment of patellar tracking. If patellar lateral glide syndrome is given as a secondary diagnosis, please refer to the treatment described for the primary diagnosis (tibiofemoral rotation or knee hyperextension) in addition to the treatment described below.

Patient Education

The goal of patient education is correction of impaired postural habits and movements.

Home Exercise Program

The patient should be instructed that they should not feel an increase in their symptoms during the performance of their exercises. In addition to monitoring for their symptoms, they should not experience a “pressure” in their knee during their exercises. If either pain or pressure occurs, they should review the instructions to the exercise to be sure that they are performing it correctly and try again. If they still experience pain or pressure, they should discontinue this exercise until they return for their next visit.

Knee Impairment

Knee impairment is the classification given in the absence of a specific movement impairment diagnosis or when a diagnosis cannot not be determined because of pain, physician-imposed restrictions, or both. If possible, the physical therapist should determine the pathoanatomical structure involved, as identified by the physician; the procedure performed, if any; and the stage for rehabilitation.

Factors that affect the physical stress of tissue and/or thresholds of tissue adaptation and injury10 include the following:

Treatment for Knee Impairment

Emphasis of treatment is to restore ROM of the knee and strength of the lower extremity without adding excessive stresses to the injured tissues. Underlying movement impairments should be addressed during rehabilitation and functional activities to ensure optimal stresses to the healing tissues.

Impairments (Body Functions and Structures)

Pain

Be sure to clarify the location, quality, and intensity.

Stage 1

Surgical: Within the first 2 weeks of the postoperative period, some pain will be associated with exercises. Gradually, over the next few weeks, pain associated with the exercise should lessen. Sharp, stabbing pain should be avoided. Mild aching is expected after exercises but should be tolerable for the patient. This postexercise discomfort should decrease within 1 to 2 hours of the rehabilitation. Complaints of increasing pain, pain that is not decreasing with treatment, or burning pain are all “red flag” indicators that treatment is too aggressive or there is a disruption in the usual course of healing. Coordinating the use of analgesics with exercise sessions is important. Splinting, bracing, and/or assistive devices may be used during this period to protect the injured tissue.

Acute Injury: Despite discomfort, tests may need to be performed to rule out serious injury. Modalities and taping/bracing may be helpful to decrease pain. The patient may also require the use of an assistive device in the early phases of healing.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Pain associated with the specific tissue that was involved in the surgery should be significantly decreased by weeks 4 to 6. Precautions may be lifted during or by postoperative weeks 4 to 6. As activity level of the patient is progressed, the patient may report increased pain/discomfort with new activities such as returning to daily activities and fitness. Pain/discomfort location should be monitored closely. Muscle soreness is expected, similar to the response of muscle to overload stimulus (e.g., weight training). General muscle soreness should be allowed to resolve, usually 1 to 2 days before repeating the bout of activity. Pain described as stabbing should always be avoided.

Edema

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: Edema is quite common in the knee s/p surgery or injury. Edema has also been implicated in the inhibition of the quadriceps and therefore should be treated aggressively.11-13 The patient should be educated in use of edema controlling techniques:

Patients should be encouraged to keep the lower extremity elevated as much as possible particularly in the early phases (1 to 3 weeks), without keeping the knee in a flexed position. Application of ice after exercise is recommended. Other methods to control edema in the knee include electrical stimulation or compression pumps. Edema should be measured at each visit. A sudden increase in edema may indicate that the rehabilitation program is too aggressive or a possible infection.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Time until swelling is resolved is variable among patients and surgical procedures. As patients increase the time spent on their feet, in regular daily activities, or doing more weight-bearing exercises, the patient may experience a slight increase in edema. This is to be expected; however, the patient should be further encouraged to use techniques stated previously to manage the edema.

Appearance

Stage 1

Surgical: Infection should be suspected if the area around the incision or the involved joint appears to be red, hot, and swollen. The physician should be consulted immediately if infection is suspected. It is common to observe bruising after surgery. This should be monitored continuously for any changes; an increase in bruising during the rehabilitation phases may indicate infection. Changes in hair growth, perspiration, or color may indicate some disturbance to the sympathetic nervous function, especially if in combination with the complaint of excessive pain. Stitches are typically removed in 7 to 14 days.

Range of Motion

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: Refer to physician’s precautions and specific protocols for guidelines regarding progression of the exercises. The most conservative, common ROM precautions include the following:

Patellar mobilizations should begin as soon as possible after surgery. Common time frames to begin patellar mobilizations include the following:

Tibiofemoral mobilizations after ACL reconstruction, meniscal repair or debridement, collateral ligament repair:

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Precautions are typically lifted by the time the patient reaches this stage. ROM should be approaching normal. Exercises may need to be progressed using passive force. To increase knee extension, prone knee extension, patients can be instructed to hang the limb off the edge of mat with weight on ankle. Patients should be advised to build up tolerance gradually and break up prolonged hang with knee flexion. For knee flexion the patient may raise knee toward the chest and use hands to add overpressure. Patient should be instructed that a stretching discomfort is expected; however, sharp pain should be avoided.

Mobilizations to the tibiofemoral joint may be indicated in later stages of rehabilitation to improve ROM. Consult with the physician before initiating joint mobilization after surgery of the knee.

Strength

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: Strengthening with overload often begins after the initial phase of healing (4 to 6 weeks). Isometrics and active movement within precautions may be started sooner. At times less than 4 weeks, emphasis should be placed on proper movement patterns in preparation for strengthening activities. After 4 weeks, strengthening may be gradually incorporated. Progression to resistive exercise is based on the patient’s ability to perform ROM with a good movement pattern and without significant increase in pain.

Quadriceps muscles are most commonly affected with surgery or injury to the knee; however, others may be involved such as the hamstrings or gastrocnemius muscles. If the patient is having difficulty recruiting the quadriceps, the following cues are helpful:

Electrical stimulation or biofeedback may be used to improve strengthening (see the following “Medications/Modalities” section).

The patient may also have strengthening precautions per the physician. Common examples of these precautions include the following:

note: Caution should be used in single-leg raise in patients >55 years of age and patients with history of low back pain.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: At this stage, precautions are typically lifted; however, with surgical procedures, such as ACL reconstruction/injury, some restrictions on open-chain resisted extension may still be in place. Strength activities can be progressed as tolerated by the patient. Common functional activities that can be considered strengthening activities include wall slides, lunges, and step-downs/step-ups. A common compensation is to shift weight away from the involved limb. Be sure that the patient maintains the appropriate amount of weight bearing during closed-chain activities.

Proprioception/Balance15

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: Activities to improve proprioception of the knee joint should be incorporated as soon as possible. Early in treatment, these activities include weight shifting, progressive increases in weight bearing on the involved lower extremity, and eventually unilateral stance. As the patient can take full weight on the involved knee, activities are progressed to use of a balance board and closed-chained activities such as wall sits, lunges, and single-leg stance.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: In this stage, precautions are typically lifted. Activities should be progressed to prepare patient to return to daily activities, fitness routines, and work or sporting activities. As the patient progresses, proprioception can be challenged by asking the patient to stand on unstable surfaces (pillows, trampoline, or BOSU ball), perturbations can be applied through having the patient catch a ball being thrown to him or her while standing on one leg. Sliding board activities have been shown to be beneficial to patients after surgery.16 See Box 7-2 for higher level neuromuscular training (Stage 3).

Cardiovascular and Muscular Endurance

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: Early in rehabilitation, if the patient does not have adequate knee ROM to complete a full revolution on a stationary bike, unilateral cycling can be performed with the uninvolved extremity. The involved extremity is supported on a stationary surface, while the patient pedals with the uninvolved extremity. Water walking and swimming are good substitutes for full weight-bearing activities. For swimming, if kicking against the resistance is contraindicated, the patient may participate in swim drills that mainly challenge the upper extremities for conditioning. Low resistance stationary cycling can begin when knee flexion ROM is approximately 110 degrees. As strength improves, resistance may be increased.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: The patient may then be progressed to activities such as water walking → walking on the treadmill → elliptical machine → Nordic ski machine → StairMaster → running when appropriate. The patient should be given specific instruction in gradual progression of these activities. See Box 7-1 for progression of running.

Patient Education

Stages 1 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Educate the patient in the structures and tissues involved and the specific medical precautions when indicated. Patients should also be taught schedule for use, and how to don and doff their brace/splint. Educate the patient in the timeline to return to activity, often driven by physician’s guidelines and educate the patient in maintaining precautions during various functional activities such as ambulation, stairs, and transfers.

Scarring

Stage 1

Surgical: Scarring, although a normal process of healing, must be managed well. Exercise, massage, compression, silicone gel sheets, and vibration are used to manage scars. The use of silicone gel is best supported by evidence in the literature. However, clinical experts also commonly use the other methods of scar management. Further research is needed to determine the efficacy of these other methods. The gradual application of stress to the scar/incision helps the scar remodel so that it allows the necessary gliding between structures. A dry incision that has been closed and reopens because of the stresses applied with scar massage indicates that the scar massage is too aggressive. Scars may be classified according to type. Linear scars that are immature are confined to the area of the incision. They may be raised and pink or reddish in the remodeling phase. As they mature they become whitish and flatten. A hypersensitive scar requires desensitization. See Chapter 5 for the examination of the hand and general treatment guidelines and Box 5-3 for more treatment suggestions on managing scar.

Changes in Status

Stages 1 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Consider carefully patient reports of increased pain or edema, decreased strength, or significant change in ROM, especially in combination. The patient should be questioned regarding precipitating events such as time of onset, or the activity. If the integrity of the surgery is in doubt, contact the physician promptly. If the patient has fever and erythema spreading from the incision, the physician should be contacted because of the possibility of an infection.

Function (Activity Limitations/Participation Restrictions)

Mobility

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: While following medical precautions, patients should be instructed in mobility, as follows:

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Instructions in mobility should be continued while following medical precautions.

All Mobility: As weight-bearing precautions are lifted, the patient should be instructed to gradually reduce the level or type of assistive device required. Progression away from the device depends on the ability of the patient to achieve a normal gait pattern. If the patient demonstrates a significant gait deviation secondary to pain or weakness, the patient should continue to use the device. This may prevent the adaptation of movement impairment and other pain problems in the future. A progression may be: walker → crutches → one crutch → cane → no assistive device.

Stairs: As the patient progresses through the healing stages and can accept more weight onto the involved leg, he or she should be instructed in normal stair ambulation.

Work/School/Higher Level Activities

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: The patient may be off work or school in the immediate postoperative period or after acute injury. When they are cleared to return to work or school, patients should be instructed in gradual resumption of activities. Emphasis should also be placed on edema control, particularly elevation and compression.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: The patient should be prepared to return to their previous activities. Suggestions for improving proprioception and balance are provided in the preceding “Proprioception/Balance” section. In preparation to return to sports, sport-specific activities should be added. The initial phases of these activities will include straight plane activities at a slow pace and then gradually increase the level of difficulty. See Box 7-2 for more detail.

Sleeping

Stage 1 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Sleeping is often disrupted in the immediate postoperative period or after acute injury. The lower extremity should be slightly elevated (foot higher than the knee and knee higher than the hip) to minimize edema. Avoid placing pillows so that the knee is held in the flexed position throughout the night.

Support

Stage 1

Surgical: A brace may be used to protect the surgical site, depending on the procedure or type of fracture. The brace should fit comfortably. The patient should be educated in the timeline for wearing the brace. Consult with physician if the wearing time is not clear.

It is common for a patient to complain of patellofemoral pain with rehabilitation after surgery. Taping can be helpful in the postoperative period. When applying tape, consider the underlying movement impairment (e.g., tibiofemoral rotation, patellar glide).

Acute injury: Taping may help decrease symptoms in a patient with acute knee injury. When applying tape, consider the underlying movement impairment (e.g., tibiofemoral rotation, knee hyperextension).

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical: The recommendations concerning the need for bracing long term are varied. Communication among the team (patient, physician, and physical therapist) is necessary. Functional bracing is recommended if the patient wishes to return to high level sporting activities and demonstrates either of the following:

Acute Injury: For injuries to the ACL that are not repaired or reconstructed, if the patient returns to sport, functional bracing is recommended.18

Medications/Modalities

Medications

Surgical: During the acute stage, physical therapy treatments should be timed with analgesics, typically 30 minutes after administration of oral medication. If medication is given intravenously, therapy often can occur immediately after administration. Communication with nurses and physicians is critical to provide optimal pain relief for the patient.

Acute injury: The patient’s medications should be reviewed to ensure that they are taking the medications appropriately.

Aquatic Therapy

Surgical/Acute Injury: Aquatic therapy to decrease weight bearing during ambulation may be helpful in the rehabilitation of patients after fracture or surgical procedures. Often, this medium is not available but should be considered if the patient’s progress is slowed secondary to pain or difficulty maintaining weight-bearing precautions. Incisions should be healed before aquatic therapy is initiated; however, materials to cover the incision may be used to allow patients to get into the water sooner.

Thermal Modalities

Surgical/Acute Injury: Instruct the patient in proper home use of thermal modalities to decrease pain. Ice has been shown to be beneficial, particularly in the immediate postoperative phases.14

Electrical Stimulation

Stage 1/Progression

Surgical/Acute Injury: Electrical stimulation can be used for three purposes: Pain relief, edema control, and strengthening. Interferential current has been shown to be helpful in decreasing pain and edema.19-21 Sensory level transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) can assist in decreasing pain. Currently, no definitive answer exists for electrical stimulation for quadriceps strengthening. It was once believed that electrical stimulation did not provide a distinct advantage over high-intensity exercise training.22-23 However, more recent studies support the use of stimulation to improve motor recruitment and strength.23-26 Be sure to check for contraindications. Avoid areas where metal is in close approximation to the skin (e.g., wires/screws to fix patellar fracture). Electrical stimulation for quadriceps strengthening can be used in patients with total knee arthroplasty once staples have been removed.25

Biofeedback

Stage 1/Progression

Surgical/Acute Injury: Biofeedback has been shown to be an effective adjunct to exercise for strengthening the quadriceps in early postoperative phases.27

Discharge Planning

Stage 1

Surgical: Equipment, such as the following, may be needed, depending on the patient’s abilities, precautions, and home environment.

Therapy: Assess the need for physical therapy after discharge from the acute phase of recovery or from the following:

After the acute phase of recovery, the patient should be reassessed to determine whether a movement impairment diagnosis exists. Supply the patient with documentation for consistency of care. Documentation should include the following:

1 Muellner T, Weinstabl R, Schabus R, et al. The diagnosis of meniscal tears in athletes: a comparison of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging investigations. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(1):7-12.

2 Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes. St Louis: Mosby; 2002.

3 Birmingham TB, Kramer JF, Kirkley A, et al. Knee bracing after ACL reconstruction: effects on postural control and proprioception. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(8):1253-1258.

4 Birmingham TB, Kramer JF, Kirkley A, et al. Knee bracing for medial compartment osteoarthritis: effects on proprioception and postural control. Rheumatology. 2001;40(3):285-289.

5 Wu GK, Ng GY, Mak AF. Effects of knee bracing on the sensorimotor function of subjects with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):641-645.

6 Lindenfeld TN, Hewett TE, Andriacchi TP. Joint loading with valgus bracing in patients with varus gonarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;344:290-297.

7 Draper ER, Cable JM, Sanchez-Ballester J, et al. Improvement in function after valgus bracing of the knee. An analysis of gait symmetry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(7):1001-1005.

8 Ramesh R, Von Arx O, Azzopardi T, et al. The risk of anterior cruciate ligament rupture with generalised joint laxity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(6):800-803.

9 Perry M, Morrissey M, Morrissey D, et al. Knee extensors kinetic chain training in anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13(8):638-648.

10 Mueller MJ, Maluf KS. Tissue adaptations to physical stress: a proposed “Physical Stress Theory” to guide physical therapist practice, education and research. Phys Ther. 2002;82(4):383-403.

11 Young A, Stokes M, Iles JF. Effects of joint pathology on muscle. Clin Orthop. 1987;219:21-27.

12 Delitto A, Lehman RC. Rehabilitation of the athlete with a knee injury. Clin Sports Med. 1989;8(4):805-839.

13 DeAndrade JR, Grant C, Dixon SJ. Joint distention an reflex muscle inhibition in the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965;47:313-322.

14 Lessard L, Scudds R, Amendola A, et al. The efficacy of cryotherapy following arthroscopic knee surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997;26(1):14-22.

15 Hewett TE, Paterno MV, Myer GD. Strategies for enhancing proprioception and neuromuscular control of the knee. Clin Orthop. 2002;1(402):76-94.

16 Blanpied P, Carroll R, Douglas T, et al. Effectiveness of lateral slide exercise in an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation home exercise program. Phys Ther. 2000;30(10):609-611.

17 Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A decision-making scheme for returning patients to high-level activity with nonoperative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(2):76-82.

18 Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Proposed practice guidelines for nonoperative anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation of physically active individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(4):194-203.

19 Christie AD, Willoughby GL. The effect of interferential therapy on swelling following open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures. Physiother Theory Pract. 1990;6:3-7.

20 Johnson MI, Wilson H. The analgesic effects of different swing patterns of interferential currents of cold-induced pain. Physiotherapy. 1997;83:461-467.

21 Young SL, Woodbury MG, Fryday-Field K. Efficacy of interferential current stimulation alone for pain reduction in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized placebo control clinical trial. Phys Ther. 1991;71:252.

22 Lieber RL, Silva PD, Daniel DM. Equal effectiveness of electrical and volitional strength training for quadriceps femoris muscles after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. J Orthop Res. 1996;14(1):131-138.

23 Van Swearingen J. Electrical stimulation for improving muscle performance. In Nelson RM, Hayes KW, Currier DP, editors: Clinical electrotherapy, ed 3, Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1999.

24 Delitto A, Rose SJ, Lehman RC, et al. Electrical stimulation versus voluntary exercise in strengthening the thigh musculature after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Phys Ther. 1988;68:660-663.

25 Stevens JE, Mizner RL, Snyder-Mackler L. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for quadriceps muscle strengthening after bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(1):21-29.

26 Fitzgerald GK, Piva SR, Irrgang JJ. A modified neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocol for quadriceps strength training following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction 1. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(9):492-501.

27 Krebs DE. Clinical electromyographic feedback following menisectomy. A multiple regression experimental analysis. Phys Ther. 1983;61:1017-1021.