Evaluation and Pain Management

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Differentiate acute from chronic pain.

2 Explain the biopsychosocial model of pain.

3 Describe two common acute and two common chronic pain syndromes.

4 Summarize two approaches to pain evaluation.

5 Describe occupationally based approaches to pain intervention.

Pain is a primary reason for seeking healthcare. An estimated one in four adult Americans reported experiencing a daylong pain episode within the past month, with 10% stating the pain lasted at least a year.55 The number of Americans with chronic pain is greater than those with diabetes, heart disease, and cancer combined.3 Despite people’s use of pain medications, two thirds of individuals experiencing chronic pain cannot perform routine occupations.1 At least $100 billion is spent each year on direct medical expenses, lost income, and lost productivity let alone the inestimatable costs of human suffering.3 The obligation to manage pain and relieve a client’s suffering is fundamental to healthcare.19 Pain may coexist with a medical condition (e.g., arthritis) or a rehabilitative procedure (e.g., splinting); it may be the primary complaint (e.g., low back pain) or a secondary disability (e.g., chronic pain in persons with cerebral palsy). Occupational therapy practitioners may suspect that pain is impeding the client’s progress but feel unsure about how to approach evaluation and intervention. This chapter defines pain, discusses the biopsychosocial model of pain, describes common pain syndromes, outlines assessment procedures, and proposes interventions.

Definitions of Pain

Pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.53 This definition conveys that pain is a subjective experience and is multifaceted. Individual variables such as mood, attention, prior pain experiences, and familial and cultural factors are known to affect one’s experience of pain.4,50

There are many types of pain, yet most investigators agree in differentiating acute from chronic nonmalignant pain, which is critical for selecting appropriate assessment and intervention strategies. Acute pain and its associated physiologic, psychological, and behavioral responses are typically caused by tissue irritation or damage in relation to injury, disease, disability, or medical or rehabilitative procedures. It has a well-defined pain onset. Acute pain serves a biologic purpose, directing attention to injury, irritation, or disease and signaling the need for immobilization and protection of a body part.51 Fortunately, acute pain is predictable and usually responds to medication and treatment of the underlying cause of pain.34

In contrast, chronic or persistent pain may begin as acute pain or may be more insidious and endure beyond the point at which an underlying pathologic condition can be identified. Increased sympathetic nervous system activity does not continue. Chronic pain does not appear to serve a biologic purpose. It is unpredictable and not amenable to routine interventions. Chronic pain often produces significant changes in personality, lifestyle, and functional ability.34,39 As pain progresses from acute to chronic, factors other than tissue damage or irritation (e.g., personality changes) become more prominent. Our client, Cathy, is now experiencing chronic pain that is negatively impacting her occupational performance.

Biopsychosocial Model of Pain

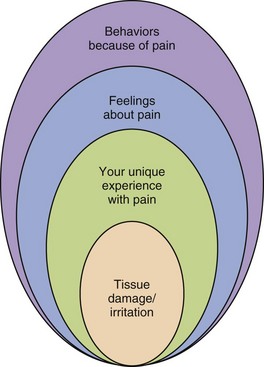

Occupational therapy has long embraced the biopsychosocial model for its emphasis on the interaction of the individual’s body, mind, and environment.54 A biopsychosocial model that conceptualizes the multilayered nature of pain is critical to accurate evaluation and effective intervention. Loeser and Fordyce45 suggested the phenomenon of pain could essentially be divided into four distinct domains: nociception, pain, suffering, and pain behavior (Figure 28-1).

FIGURE 28-1 Loeser’s model of pain. Adapted from Loeser JD: Concepts of pain. In Stanton-Hicks M. Boas R, editors: Chronic low back pain, New York, 1982 Raven, p. 146.

Nociception is the detection of tissue damage by transducers in the skin and deeper structures, and the central transmission of this information by A-delta and C fibers in the peripheral nerves. Nociception is the body’s message to do something or avoid doing something for pain relief. Pain is the perceived noxious input to the nervous system. Suffering is the negative affective response to pain. Finally, pain behavior is what an individual says or does (e.g., moaning) or does not say or do (e.g., engage in occupations), which leads others to conclude that individual is experiencing noxious stimuli. Pain behaviors are observable and are influenced by familial, cultural, and environmental consequences. This model purports that one can experience or demonstrate some domains of the model in the absence of others. In chronic nonmalignant pain, pain behaviors and suffering often exist in the absence of nociception.23,39,45,75

Our client Cathy stated that she continues to experience pain but also expressed fear that the pain would never go away. In that sense she is captive to her pain experience.

Pain Syndromes

The evaluation and treatment of pain resulting from trauma, disease, or unknown etiology are significant healthcare concerns. The following sections describe common pain syndromes, their etiology, and typical interventions

Headache Pain

Recurrent headaches are one of the most common pain problems. Migraines affect approximately 12% to 15% of the general population. Over half of the population of persons with headaches does not seek treatment because they perceive the problem as too trivial, have concerns about medication side effects, and believe no adequate treatment is available.47

Migraine headaches are characterized by recurrent pain episodes varying in frequency, duration, and intensity. Migraines may occur when the individual oversleeps, when tired, when skips meals, with overexertion, when stressed, and when recovering from stress.28 The pain is typically unilateral and pulsatile and may be accompanied by anorexia, nausea, vomiting, neurologic symptoms (e.g., sensitivity to light and sound), and mood changes (e.g., irritability).47 A strong genetic predisposition exists for migraines. Experimental evidence supports the role of serotonin in migraine. Stress, attention, the environment, and mood (e.g., anxiety) affect these headaches.

Tension-type headaches (TTH) are the most common headache disorder. Approximately 73% of adult Americans experience one or more tension headaches in a year.9 These headaches are typically of mild-to-moderate intensity. The pain is bilateral and of a pressing character and does not have associated symptoms. Precipitating headache factors include situational stress, missed meals, sleep deprivation, and noxious stimuli (e.g., heat exposure).47 TTH has been attributed to a disorder of central nervous system (CNS) modulation. Simple analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen) are standard treatment. Headache control is often achieved with lifestyle management and medication.

Low Back Pain

Low back pain (LBP) is the second most common pain complaint among the adult population. Approximately 3% to 7% of the population in western industrialized countries experience chronic LBP. Job absenteeism, loss of productive activity, and decreased participation are common consequences of LBP.73 Fear of the etiology of pain, the interventions, and social consequences of pain can be harmful to the client. The most common causes of LBP are injury (e.g., lifting) and stress, resulting in musculoskeletal and neurologic disorders (e.g., muscle spasm and sciatica). Back pain also may result from infections, degenerative diseases (e.g., osteoarthritis), rheumatoid arthritis, spinal stenosis, tumors, and congenital disorders.62 LBP tends to improve spontaneously over time.74 Numerous schools of thought govern interventions. With chronic back pain, functional restoration is key. Medication management, physical therapy (e.g., exercise, massage, traction), and self-care education are common treatment approaches. Once significant back pain has lasted for 6 months, however, the chance that the affected individual will return to work is only 50%.16 (See Chapter 41.)

Cathy’s LBP has significantly compromised her ability to engage in occupations. She has not returned to work and is at risk for never being gainfully employed. Cathy is no longer able to engage in her preferred recreational activities of dancing and bowling. Her ability to care for her personal ADLs is compromised and she had difficulties stepping in and out of the tub and even bending over to turn the water faucet handles to regulate the water temperature. She must request assistance when grocery shopping since bending and reaching produce increases her pain. Cathy even reports that getting in and out of her car is difficult and requires planning and care because of her fear of increasing the pain in her back.

Arthritis

Approximately one third of all American adults experience joint pain, swelling, or limited mobility because of arthritis.43 Osteoarthritis (OA), the most common form of arthritis, is a degenerative joint disease characterized by a progressive, dull ache and swelling, typically affecting the fingers, elbows, hips, knees, and ankles. OA may be exacerbated by movement. Degeneration of the articular cartilage leading to joint pain, reduced mobility, and swelling occur, typically affecting weight-bearing joints in persons after age 45.26,66

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects 1% to 2% of the American population with women more often affected.26 It usually has a slow insidious onset, characterized by aches, pains, swelling, and stiffness. Any joint may be involved, but usually there is a symmetrical pattern affecting the fingers, wrists, knees, ankles, and cervical spine. This systemic disease involves remissions and exacerbations of destructive inflammation of connective tissue, especially in the synovial joints.66 The Arthritis Foundation supports self-management (e.g., exercise, relaxation, problem solving strategies) of the disease.46 See Chapter 38 for more information on arthritis.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

The incidence of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) has been reported as 25.2 new cases per 100,000 annually.33 The pain experienced with CRPS is a continuous, severe, burning pain that results from trauma, postsurgical inflammation, infection, or laceration to an extremity, causing a cycle of vasospasm and vasodilatation. Pain, edema, shiny skin, coolness of the hand, and extreme sensitivity to touch occur. An individual experiencing CRPS may also have excessive sweating or dryness. The key feature of CRPS is continuous, intense pain out of proportion to the severity of the injury (if an injury has occurred), which worsens over time. Exacerbating pain factors include movement, cutaneous stimulation, and stress.40,77 OT treatment strives to normalize sensation, reduce edema, and increase mobility, strength, and endurance while decreasing guarding and restoring routine activities. Simultaneously clients often receive physical therapy, psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, recreational therapy, and vocational rehabilitation.33

Myofascial Pain Syndrome

Muscle pain is common across all age groups, but with the elderly most often affected. Myofascial pain refers to a large group of muscle disorders defined by the presence of “trigger points” (i.e., localized areas of deep muscle tenderness). Pressure on the trigger point elicits pain to a well-defined distal area. Myofascial pain is perceived as a continual dull ache often located in the head, neck, shoulder, and low back areas. The trapezius muscle is one of the most commonly affected muscles. The pain may result from sustained muscle contraction or from an acute strain caused by a sudden overload or overstretching of the muscles in the head, neck, shoulder, or lower back regions.29,65 Physical therapy, needling therapies (i.e., insertion of a solid needle for relief of muscular pain), manual therapies, and modalities are common treatment approaches.13

Fibromyalgia

The prevalence of fibromyalgia ranges from 0.7% to 3.2% in the adult population. Fibromyalgia is widespread musculoskeletal pain in the muscles, ligaments, and tendons. Skeletal muscles have been implicated as the cause of fibromyalgia, but no specific abnormalities have been identified. Abnormalities of the neuroendocrine system, autoimmune dysfunction, immune regulation, cerebral blood flow difficulties, and sleep disturbances have been suggested.35 Genetic factors, physical trauma, peripheral pain syndromes, infections, hormonal changes, and emotional distress are capable of triggering fibromyalgia. Pharmacologic therapies, cardiovascular exercise, and cognitive behavior therapy have all been proven beneficial.10

Cancer Pain

Clients with cancer often have multiple pain problems that are frequently undertreated. Cancer pain varies greatly in its frequency, duration, and intensity. In the initial and intermediate stages, 40% to 50% of clients experience moderate-to-severe pain. About 60% to 90% of clients with advanced cancer have pain. Cancer pain may result from tumor progression, interventions (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation), infection, or muscle aches when clients decrease their activity.68

Disability-Related Pain

Pain is a significant problem for many persons with physical disabilities,15 including cerebral palsy,17 spinal cord injury,12 limb deficiency,32 and multiple sclerosis.30 Physiologic changes resulting from the disability and psychosocial factors (e.g., negative thoughts) are known to influence the intensity and impact of pain in many persons with chronic pain as a secondary condition to their disability.38 Data support the use of relaxation training, hypnosis, and medication management.

Evaluation

A referral for an occupational therapy (OT) evaluation is made when pain interferes with the client’s occupational performance. As a member of an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary team, the occupational therapist focuses the evaluation on the factors that contribute to the client’s pain perception and pain interference. Before the occupational therapy program is implemented as well as throughout the interventions, objective measures of occupational performance should be obtained to determine the occupational profile of the client and the value of those occupations.31 Factors that may contribute to pain perception, occupational role disruption, decreased occupational performance, and diminished quality of life should be identified. In addition to these essential measurements, pain intensity should be recognized as the “fifth vital sign” and assessed on a regular basis.2

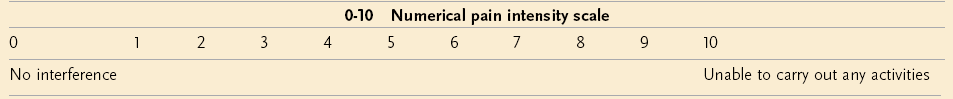

The occupational therapist performs a pain evaluation, viewing pain as a complex phenomenon involving psychological arousal, sensations of noxious stimulation, tissue damage or irritation, behavioral changes, complaints of distress, and the social environment. Self-report measures are the most common type of pain assessment because pain is considered to be a subjective experience.72 The clinical interview focuses on the client’s identification of pain onset, location(s), frequency, intensity, duration, exacerbating and relieving pain factors, past and current pain treatments, mood, and occupational performance. A Verbal Rating Scale (VRS), 0-10 Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), or Visual Analog Scale (VAS) (Box 28-1) may be used in assessing self-reports of pain intensity.57,72 These instruments have strong psychometric properties and high utility.

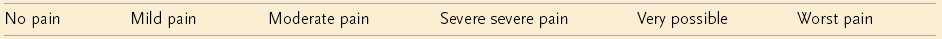

A VRS of pain intensity consist of a list of 4 to 15 verbal descriptors and a corresponding number (e.g., 0 = “no pain,” 1 = “mild pain,” 2 = “moderate pain,” 3 = “severe pain”). This is an easy-to-use scale, but might have a lengthy list of verbal descriptors, and the client may not find a descriptor on the list that matches his or her experiences.38

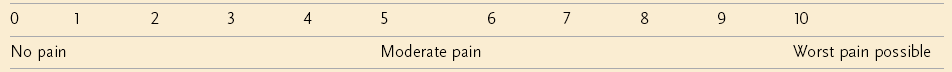

The NRS consists of a range of numbers, typically 0 (“no pain”) to 10 (“worst pain possible”) (Box 28-2). The client selects which one number is most representative of his or her pain intensity. Use of the 0 to 10 NRS is highly recommended. Pain ratings in the 1 to 4 range have minimal impact on functional performance and are labeled “mild” pain. Ratings of 5 or 6 (“moderate” pain) indicate that pain has a greater impact on functioning. Ratings of 7 to 10 or “severe” pain have the greatest impact on performance.14

The VAS consists of a horizontal or vertical line, typically 100 mm long, with each end of the line labeled with descriptors representing the range of pain intensity (e.g., “no pain” and “pain as bad as can be”). The client draws a mark on the line that represents his or her pain intensity and the distance measured from the “no pain” anchor to the mark becomes that individual’s pain score. It should be noted some individuals have difficulties with understanding and completing the measure.38

For both the NRS and VAS scales, decreases or increases between 30% and 35% appear to indicate a meaningful change in pain. Clients tend to prefer VRSs and NRSs over VASs.38 It has been recommended that both clinicians and researchers use the 11-point NRS so that comparisons between studies can be made.14

When occupational therapy services were initiated for Cathy, the therapist used an NRS to determine the existence and intensity of the pain Cathy experienced on a daily basis.

Pain behaviors are often targeted in evaluation and intervention.22 Pain behaviors include guarded movement, bracing, posturing, limping, rubbing, and facial grimacing41 and are in response to pain, suffering, and distress. The University of Alabama Pain Behavior Scale is an example of a standardized rating scale that is reliable, valid, and an easy method for documenting observable behaviors.60 Analysis of the client’s pain behaviors before, during, and after intervention with and without a significant other present can provide valuable information about the role of situational and learned factors in the individual’s pain perception, as well as responses to intervention. Healthcare utilization and medication use are additional pain behaviors that are clinically relevant.70 Merskey cautioned practitioners not to provide treatment for reducing pain behaviors in lieu of attempts at alleviating the pain.52 Evaluation that focuses solely on pain behavior may lead to the inaccurate conclusion that pain behavior suggests malingering, lack of motivation, or hypochondriasis.

Occupational performance is the primary focus of the occupational therapist. The client may complete daily activity diaries as an assessment technique and outcome measure.20 With this technique, the client records hourly entries of time spent in sitting, standing, reclining, and productive activities, which may be corroborated by trained staff or significant others during treatment. Activity diaries are highly reliable and valid.22

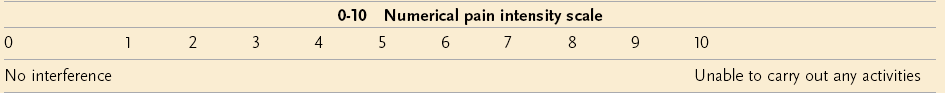

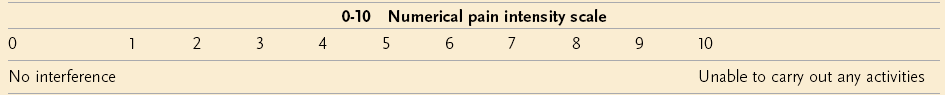

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)11 is a reliable and valid instrument that may also be used to measure pain interference. Pain interference is defined as the extent to which pain impacts daily functioning.38 Clients rate on an ordinal scale how much their pain has interfered with general activity, mood, mobility, work, interpersonal relationships, sleep, enjoyment of life, self-care, and recreation (Box 28-3). The responses are averaged to determine the Pain Interference score. This information may be helpful in determining baseline tolerance levels for specific occupations that may be addressed in treatment. The BPI can be used with persons with disability-related pain (e.g., spinal cord injury, cerebral palsy) as well as an outcome measure.38 Similarly, the Pain Disability Index (PDI) is a brief valid and reliable self-report measure of general and domain specific pain-related disability. It uses an ordinal scale to measure how disabling pain is with family/home responsibilities, recreation, social activity, occupation, sexual behavior, self-care, and life-support activity.59

Similarly, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)42 can also be used in valid and reliable pain assessment. The COPM detects changes over time in the individual’s perceptions of his or her occupational performance in the areas of self-care, productivity, and leisure, as well as the importance of being able to perform these occupations and the level of satisfaction with performance using 10-point scales. The COPM has good evidence of concurrent criterion validity and sensitivity to change. It is especially helpful in collaborative functional goal setting.61

Finally, evaluation must acknowledge that cultural disparities in pain experiences exist. Differences in pain experiences have been found between whites and African Americans. For example, African Americans report a poorer quality of life with increasing levels of pain, disability, symptoms, and emotional distress as compared to whites. Women are known to report more pain than men. It should also be noted that persons with a lower socioeconomic status tend to be sicker and overall have more chronic health problems.56 Lastly, pain frequently has been overlooked and therefore undertreated in children and the elderly.69 These differences have been attributed to numerous causes such as access to healthcare and coping skills.

Cathy had indicated that her pain and the fear associated with the pain severely limited her ability to engage in several occupations. She had not returned to work and had greatly decreased social activities. Her contact with friends was limited to infrequent telephone conversations and occasionally a friend would stop by to visit. Prior to her injury she regularly went out with friends to movies, dancing, and bowling, but all those activities had been eliminated because of the pain.

Intervention

The obligation to manage pain and relieve a client’s suffering is fundamental. A multiple or interdisciplinary team approach to chronic pain is common and includes the client as an active and educated participant. The occupational therapist typically works in collaboration with the client, a physician, a psychologist, a physical therapist, and a nurse. Occupational therapy interventions focus on increasing physical capacities, productive and satisfying performance of life tasks and roles, mastery of self and the environment through activities, and education.37 As the causes of pain are multifactorial, so are the approaches to treatment. Effective pain management addresses all the dimensions of pain. Typical pain interventions are described next.

Interventions may need to be introduced on a trial-and-error basis. The effectiveness of pain interventions can be measured and documented in a variety of ways. Clinical improvement can be measured in occupational performance (e.g., BPI), increased participation (e.g., diary), lower pain intensity (e.g., NRS), reduction in pain behaviors (e.g., University of Alabama Pain Behavior Scale), improved mood (e.g., Sickness Impact Profile),5 and decreased drug and healthcare utilization.

Medication

Medications are generally the treatment of choice for individuals experiencing acute pain. Occupational therapists need to observe clients for possible drug reactions. To reduce possible discomfort from rehabilitative procedures, practitioners should check that clients are adequately medicated in advance. The World Health Organization76 analgesic ladder is well established in adult pain management as a stepwise approach for choosing an analgesic. Aspirin and acetaminophen are frequently used in the treatment of mild pain (e.g., backache) because of their high level of effectiveness, low level of toxicity, and limited abuse potential. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents have been used in the treatment of arthritis and inflammation of a musculoskeletal origin. Codeine is often used for moderate-intensity pain that has not responded adequately to aspirin or acetaminophen. Morphine is the standard medication used in the relief of severe pain. The use of opioid analgesics (narcotics) in chronic nonmalignant pain has been controversial because of concerns about addiction.34

Activity Tolerance

Although a few days of rest may be indicated for acute pain, therapeutic activity is important for the treatment of any underlying impairment. Activity levels are increased on a gradual basis, with the client working to “tolerance” (i.e., gradual increase in task demands such as mobility, strength, and endurance), as opposed to “pain,” before a scheduled rest period. The client should not initiate rest at the time of the pain onset or exacerbation because this may reinforce pain behaviors.23 A gradual increase in activity also lessens the likelihood of an exacerbation of pain.23 Fordyce provided guidelines for the use of quota programs for clients with chronic pain. Regular gentle exercise (e.g., walking, swimming, water aerobics) is recommended. Modalities (e.g., heat or cold) may be applied before activity as a means of enhancing functional performance. When an individual is engaged in interesting and purposeful activity, he or she may be more relaxed, less preoccupied with pain, and more fluid in movement. Task selection based on occupational roles, interests, and abilities is a unique contribution of occupational therapy in pain management.67

The occupational therapy intervention program for Cathy considered her active lifestyle prior to the injury and began with simple activities such as accompanying a friend to a local shopping mall and walking in the complex. The occupational therapist helped Cathy plan the outing by suggesting that the walk occur during a weekday evening instead of busy weekends and that Cathy take frequent breaks during the initial walk to sit on one of the benches provided within the mall.

Body Mechanics and Posture Training

Instruction in and rehearsal of proper body mechanics and postures that will not increase the risk of low back injury or strain are essential for clients experiencing both acute and chronic LBP.48 Practice in using the body safely and to maximum performance during routine tasks in natural (i.e., home, work, or leisure) environments is particularly important.64,67 The client should be taught to avoid tasks or positions that do not allow balanced posture. For detailed guidelines on proper posture and body mechanic principles, please refer to Chapter 41. For clients in wheelchairs, the information on positioning in Chapter 11 is also important.

Energy Conservation, Pacing, and Joint Protection

Instruction in energy conservation, pacing, and joint protection may be beneficial for achieving recommended amounts of rest during task completion, recommended time spent physically active, and balance between rest and physical activity. Clients, especially those with rheumatoid arthritis, are taught to use these strategies before they experience pain and fatigue so that occupational performance can continue as long as possible without pain and fatigue.25 Cathy was able to use energy conservation strategies and pacing to return to many previous occupations such as doing her laundry using a portable table to place the laundry basket on the table when putting the clothes in her top loading washer. The table was also used when she removed the clothes from the washer before she moved them to the side-opening dryer. This example illustrates the use of energy conservation and pacing that was employed throughout Cathy’s daily life.

Splinting

Splinting of the upper extremity may be necessary if contractures or muscle imbalances occur. In CRPS, static resting splints may provide pain relief. Splint use is alternated with tasks that require joints to be taken through range of motion, since total immobilization could lead to increased pain and dysfunction. Static resting splints maintain joint alignment, reducing inflammation and pain during flare-ups of rheumatoid arthritis. Splints that support the wrist in a functional position throughout the day and night may be necessary for 4 to 6 weeks.6 People should use caution because orthoses may add to the stress on proximal joints when the wrist is confined.8

Adaptive Equipment

Clients with acute LBP may use a back support for stabilization of the lumbar area and increased abdominal pressure to improve postural alignment. This can result in decreased muscle spasm, reduced pain, and improved ability to engage in occupations.6,71 Adaptive equipment is often used to increase function and comfort in persons with arthritis.66

Relaxation

Relaxation training can be used to decrease muscle tension, which is believed to precipitate or exacerbate pain. Progressive muscle relaxation involves the systematic tensing of major musculoskeletal groups for several seconds, passive focusing of attention on how the tensed muscles feel, and release of the muscles and passive focusing on the sensations of relaxation. As the client learns to recognize muscle tension, he or she can direct attention to inducing relaxation.58

Autogenic training is another means to inducing relaxation. This approach involves the silent repetition of self-directed formulas that describe the psychophysiologic aspects of relaxation (e.g., “My arms and legs are warm”). The client passively concentrates on these phrases while assuming a comfortable body posture, with eyes closed, in a quiet setting. Relaxation training has been used successfully to modify a variety of chronic pain complaints, including headache, LBP, myofascial pain, arthritis, and cancer pain.27,58

Relaxation strategies were very helpful to Cathy and allowed her to regain a “bit of her old self.” When out shopping with friends she would often pause briefly and appear to be studying the clothing item while using the relaxation strategies rehearsed during her occupational therapy sessions. This allowed her to continue with the outing.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is the use of instrumentation to provide visual or auditory signals that indicate some change in a biologic process, such as skin temperature, as it occurs. The signals are used to increase the client’s awareness of these changes so that the changes may come under voluntary control. Biofeedback is based on the assumption that a maladaptive psychophysiologic response results in pain. Despite the questionable validity of this assumption, data do exist to support the use of biofeedback for the treatment of headache disorders, LBP, arthritis, myofascial pain, and CRPS.27 Biofeedback for pain control is typically done in conjunction with relaxation training.

Distraction

Distraction is often used to divert an individual’s attention and concentration away from acute mild-to-moderate intensity pain and reduce distress, especially during medical and rehabilitative procedures. Distraction may have an internal focus (e.g., daydreaming, guided imagery) or external focus (e.g., listening to music, watching television).36

Therapeutic Modalities

Physical agent modalities (PAM) may be used by occupational therapists as adjuncts to or in preparation for purposeful activities. Appropriate postprofessional education is needed to ensure that the practitioner is competent in the use of these modalities.7 Both heat and ice are useful in reducing pain and muscle spasm of musculoskeletal and neurologic pathologies. Superficial heat includes hot packs, heating pads, paraffin wax, fluidotherapy, hydrotherapy, whirlpool, and heat lamps. The application of heat increases local metabolism and circulation. Vasoconstriction occurs initially, followed by vasodilatation resulting in muscle relaxation. The use of heat is indicated in the treatment of subacute and chronic traumatic and inflammatory conditions such as muscle spasms, arthritis of the small joints of the hands and feet, tendonitis, and bursitis.7,21,44

The use of heat is contraindicated in several instances. Heat is not to be used for clients who have acute inflammatory conditions, cardiac insufficiency, malignancies, or peripheral vascular disease. Preexisting edema may be aggravated. It should not be used for clients who are insensate. Heat may cause malignancies to spread.49

Cold can improve pain control by elevating the pain threshold (i.e., the minimal level of noxious stimulation at which the client first reports pain). Local vasoconstriction occurs in direct response to cold therapy (cryotherapy). When the area is subsequently exposed to air, vasodilatation occurs. Cold applications also result in decreased local metabolism, slowing of nerve conduction velocity, diminished muscle spasm secondary to joint or skeletal pathologic conditions and spasticity, decreased edema, and lessened tissue damage. Cold can be applied via commercial packs, sprays, ice cups, or a massage stick.7,44

There are several contraindications in the use of cryotherapy. Clients who are extremely sensitive may not be able to tolerate cold. If a client has a history of frostbite in the area to be treated, another modality must be used. If a client has Raynaud’s disease, severe pain may occur in the treated area. Cryotherapy is contraindicated in the very young and elderly because their thermoregulatory responses may not function sufficiently.21

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is a noninvasive pain relief measure that uses cutaneous stimulation. A TENS unit consists of a battery-powered generator that sends a mild electrical current through electrodes placed on the skin at or near the pain site, stimulating A fibers. Some success has been demonstrated with using TENS to relieve acute and chronic painful conditions caused by disease or injury of nervous system structures or the skeleton, muscle pain of ischemic origin in the extremities, and angina pectoris.63

Relapse Management

Clients with chronic pain frequently experience a flare-up. During the flare-up the client is typically encouraged to reduce aerobic conditioning exercises (e.g., walking, stationary biking, swimming). As pain subsides, an incremental, gradual increase in activity should be implemented.24 The client should be encouraged to increase his or her use of pain-coping and self-management strategies throughout the flare-up.18

Summary

Pain is a complex phenomenon. Occupational therapists bring their understanding of anatomy, physiology, kinesiology, psychology, and function to the comprehensive evaluation and treatment of the client with pain. Interventions focus on relieving pain, improving occupational performance, and developing coping strategies. Data are needed to support the use of the OT interventions described in this chapter.

1. Contrast acute pain and chronic pain.

2. List and describe two different pain syndromes that may be present in persons referred for occupational therapy.

3. Identify the essential elements of a pain assessment.

4. Explain at least six interventions used in the treatment of pain.

5. Describe the role and define the scope of occupational therapy in the evaluation and treatment of pain.

References

1. American Pain Foundation (a). Key messages for pain care advocacy—2010. Available at www.google.com/search?hl=en8q=Key+messages+about+chronic+pain8btnG=Search&aq=f&aqi=8oq=. [Accessed March 1, 2011].

2. American Pain Foundation (b). Fifth vital sign. Available at www.painfoundation.org/learn/living/qa/fifth-vital.sign.html. [Accessed March 29, 2011].

3. American Pain Foundation (c). Pain facts & figures. Available at www.painfoundation.org/archive/newsroom/reporter-29,2001resources/pain-facts-figures.html. [Accessed March 29, 2011].

4. Baptiste, S. Chronic pain, activity and culture. Can J Occup Ther. 1988;55:179–184.

5. Bergner, M, Bobbitt, RA, Carter, WE, Gilson, BS. The Sickness Impact Profile: Development and final version of a health status measure. Medical Care. 1981;19:787–805.

6. Borrelli, EF, Warfield, CA. Occupational therapy for persistent pain. Hospital Practice. 1986;21(8):36K–37K.

7. Breines, EB. Therapeutic occupations and modalities. In Pendleton HM, Schultz-Krohn W, eds.: Pedretti’s occupational therapy: practice skills for physical dysfunction, ed 7, St. Louis: Mosby, 2012.

8. Bulthaup, S, Cipriani, D, Thomas, JJ. An electromyography study of wrist extension orthoses and upper-extremity function. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53(5):434–440.

9. Cailliet, R. Headache and face pain syndromes. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1992.

10. Clauw, DJ. Fibromyalgia. In: Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, eds. Bonica’s management of pain. ed. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:471–488.

11. Cleeland, CS. Research in cancer pain: what we know and what we need to know. Cancer. 1991;67:823.

12. Dijkers, M, Bryce, T, Zanca, J. Prevalence of chronic pain after traumatic spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:13–29.

13. Dommerholt, J, Shah, JP. Myofascial pain syndrome. In: Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, eds. Bonica’s management of pain. ed. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:450–471.

14. Dworkin, RH, Turk, DC, Farrar, JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113:9–19.

15. Ehde, DM, Jensen, MP, Engel, JM, et al. Chronic pain secondary to disability: a review. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:3–17.

16. Ellis, RM, Back pain. BMJ, 1995;310(6989):1220. Engel JM: Evaluation and pain management. In Pendleton HM, Schultz-Krohn W, editors: In Pedretti’s occupational therapy: practice skills for physical dysfunction, ed 6, St. Louis, 2006, Mosby Elsevier.

17. Engel, JM, Jensen, MP, Hoffman, AJ, Kartin, D. Pain in persons with cerebral palsy: extension and cross validation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1125–1128.

18. Engel, JM. Pain regulation. In: Brown C, Stoffel VC, eds. Occupational therapy in mental health: A vision for participation. Philadelphia: FA Davis Company, 2011.

19. Fishman, S. Forensic pain medicine. Pain Med. 2004;5:212–213.

20. Follick, MJ, Ahern, DK, Laser-Wolston, N. Evaluation of a daily activity diary for chronic pain patients. Pain. 1984;19(4):373–382.

21. Fond, D, Hecox, B. Superficial heat modalities. In: Hecox B, Mehreteab TA, Weisberg J, eds. Physical agents: a comprehensive text for physical therapists. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1994.

22. Fordyce, WE. Behavioral methods for chronic pain and illness. St. Louis: Mosby; 1976.

23. Fordyce, WE. Contingency management. In Bonica JJ, ed.: The management of pain, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1990.

24. Fordyce, WE. Back pain in the workplace: management of disability in nonspecific conditions. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1995.

25. Furst, GP, et al. A program for improving energy conservation behaviors in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Occup Ther. 1987;41(2):102–111.

26. Gardner, GC. Joint pain. In: Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, eds. Bonica’s management of pain. ed. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:431–450.

27. Gaupp, LA, Flinn, DE, Weddige, RL. Adjunctive treatment techniques. In Tollison CD, Satterthwaite JR, Tollison JW, eds.: Handbook of pain management, ed 2, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1994.

28. Goadsby, PJ. Headache. In: Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, eds. Bonica’s management of pain. ed. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:860–875.

29. Goldberg, DL. Controversies in fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndromes. In Arnoff GM, ed.: Evaluation and management of chronic pain, ed 3, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1998.

30. Hadjimichael, O, Kerns, RD, Rizzo, MA, et al. Persistent pain and uncomfortable sensations in persons with multiple sclerosis. Pain. 2007;127:35–41.

31. Hamdy, RC. The decade of pain control and research (Editorial). Southern Med Jo. 2001;94(8):753–754.

32. Hanley, MA, Ehde, DM, Jensen, MP, et al. Chronic pain associated with upper-limb loss. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88:742–751.

33. Harden, RN, Bruehl, SP. Complex regional pain syndrome. In: Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, eds. Bonica’s management of pain. ed. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:314–331.

34. Hawthorn, J, Redmond, K. Pain: causes and management. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 1998.

35. Hernandez-Garcia, JM. Fibromyalgia. In Warfield CA, Fausett HJ, eds.: Manual of pain management, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

36. Hoffman, HG, Patterson, DR, Carrougher, GJ. Use of virtual reality for adjunctive treatment of adult burn pain during physical therapy: a controlled study. Clin J Pain. 2000;16(3):244–250.

37. International Association for the Study of Pain, ad hoc Subcommittee for Occupational Therapy/Physical Therapy Curriculum: Pain curriculum for students in occupational therapy or physical therapy, IASP Newsletter, November/December, 1994, The Association.

38. Jensen, MP. Measurement of pain. In: Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, eds. Bonica’s management of pain. ed. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:251–270.

39. Jensen, MP, Moore, MR, Bockow, TB, et al. Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in persons with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:146–160.

40. Kasch, MC. Hand injuries. In Pedretti LW, ed.: Occupational therapy: practice skills for physical dysfunction, ed 4, St. Louis: Mosby, 1996.

41. Keefe, FJ, Block, AR. Development of an observation method for assessing pain behavior in chronic low back pain patients. Behav Ther. 1982;13:363.

42. Law, M, Baptiste, S, Carswell, A, et al. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, ed 3. Ottawa, Canada: CAOT Publications ACE; 1998.

43. Lawrence, RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1998;41(5):778–799.

44. Lee, MHM, et al. Physical therapy and rehabilitation medicine. In Bonica JJ, ed.: The management of pain, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1990.

45. Loeser, JD, Fordyce, WE. Chronic pain. In: Carr JE, Dengerink HA, eds. Behavioral science in the practice of medicine. New York: Elsevier, 1983.

46. Lorig, K, Holman, H. Arthritis self-management studies: a twelve-year review. Health Educ Q. 1993;20(1):17–28.

47. Mauskop, A. Head pain. In: Ashburn MA, Rice LJ, eds. The management of pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1998.

48. McCauley, M. The effects of body mechanics instruction on work performance among young workers. Am J Occup Ther. 1990;44(5):402–407.

49. McLean, JP, Chimes, GP, Press, JM, et al. Basic concepts in biomechanics and musculoskeletal rehabilitation. In: Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, eds. Bonica’s management of pain. ed. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:1294–1312.

50. Melzack, R. The puzzle of pain. New York: Basic Books; 1973.

51. Melzack, R, Wall, PD. The challenge of pain. London: Penguin Books; 1988.

52. Merskey, H. Limitations of pain behavior. APS. 1992;1:101–104.

53. Merskey, H, Bogduk, N. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms, Pain, ed 2. Seattle: International Association for the Study of Pain; 1994.

54. Mosey, AC. An alternative: the biopsychosocial model. Am J Occup Ther. 1974;28:137–140.

55. National Pain Foundation (a), http://nationalpainfoundation.org/articles/147/pain-affects-millions of Americans. [Retrieved March 1, 2011].

56. National Pain Foundation (b), http://nationalpainfoundation.org/cat/925/disparities-in-pain. [Retrieved March 1, 2011].

57. Patterson, DR, Jensen, M, Engel-Knowles, J. Pain and its influence on assistive technology use. In: Scherer MJ, ed. Assistive technology: matching device and consumer for successful rehabilitation. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2002.

58. Payne, RA. Relaxation techniques: a practical handbook for the health care professional. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

59. Pollard, CA. Preliminary validity study of the Pain Disability Index. Index Percept Mot Skills. 1984;59:974.

60. Richards, JS, et al. Assessing pain behavior: the UAB Pain Behavior Scale. Pain. 1982;14:393.

61. Rochman, D, Kennedy-Spaien, E. Chronic pain management: approaches and tools for occupational therapy. OT Practice. 2007;12:9–15.

62. Rowlingson, JC, Keifer, RB. Low back pain. In: Ashburn MA, Rice LJ, eds. The management of pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1998.

63. Sjolund, BH, Eriksson, M, Loeser, JD. Transcutaneous and implanted electrical stimulation of peripheral nerves. In Bonica JJ, ed.: The management of pain, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1990.

64. Smithline, J, Dunlop, LE. Low back pain. In Pedretti LW, Early MB, eds.: Occupational therapy: practice skills for physical dysfunction, ed 5, St. Louis: Mosby, 2001.

65. Sola, AE, Bonica, JJ. Myofascial pain syndromes. In Bonica JJ, ed.: The management of pain, ed. 2, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1990.

66. Spencer, EA. Upper extremity musculoskeletal impairments. In Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, Schell BAB, eds.: Willard & Spackman’s occupational therapy, ed 10, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2003.

67. Strong, J. Chronic pain: the occupational therapist’s perspective. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996.

68. Strong, J, Bennett, S. Cancer pain. In: Strong J, Unruh AM, Wright A, Baxter GD, eds. Pain: a textbook for therapists. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

69. Szafran, SH. Physical, mental, and spiritual approaches to managing pain in older clients. OT Practice. 2011;16:CE-1–CE-8.

70. Turk, DC, Robinson, JP. Multidisciplinary assessment of patients with chronic pain. In: Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, eds. Bonica’s management of pain. ed. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:288–301.

71. Tyson, R, Strong, J. Adaptive equipment: its effectiveness for people with chronic lower back pain. Occup Ther J Res. 1990;10:111.

72. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Management of cancer pain. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research; 1994.

73. Van Tulder, MW, Jellema, P, van Poppel, MNM, et al, Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low back pain (Cochrane Review). Issue 4. The Cochrane Library. Update Software: Oxford, 2000.

74. Waddell, G. A new clinical model for the treatment of low back pain. Spine. 1987;12:632–644.

75. Wolff, M, Wittink, H, Michel, TH. Chronic pain concepts and definitions. In: Wittink H, Michel TH, eds. Chronic pain management for physical therapists. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997.

76. World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Report of a WHO expert committee. World Health Organization Technical Report Series, 804. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1990.

77. Wright, A. Neuropathic pain. In: Strong J, Unruh AM, Wright A, Baxter GD, eds. Pain: a textbook for therapists. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.