Arthritis

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Understand the distinct disease processes of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

2 Describe common similarities and differences in the symptoms of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

3 Identify joint changes and hand deformities commonly seen with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

4 Recognize medications commonly used in the treatment of arthritis and their side effects.

5 Understand the physical and psychosocial effects of arthritis and their impact on occupational functioning.

6 Identify important areas to evaluate in clients with arthritis.

7 Identify the intervention objectives of occupational therapy for clients with arthritis.

8 Design an appropriate individualized intervention plan based on diagnosis, stage of disease, limitations in functional activity, and client goals and lifestyle.

9 Identify key resources helpful to persons with arthritis and to health care providers.

10 Identify evaluation and treatment precautions related to arthritis.

Overview of Rheumatic Diseases

The term arthritis is of Greek derivation and literally means “joint inflammation.” It is used to describe many different conditions that fall under the larger umbrella of rheumatic diseases. Rheumatic diseases encompass more than 100 conditions characterized by chronic pain and progressive physical impairment of joints and soft tissues (e.g., skin, muscles, ligaments, tendons). These conditions include osteoarthritis (OA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis, scleroderma, gout, and fibromyalgia. One in every five adults in the United States has signs and symptoms of arthritis, and these have been reported to be the main reason that adults older than 65 years visit a physician.21 Arthritis is a major public health problem that costs the U.S. economy nearly $128 billion in medical care and indirect expenses annually.22 Rheumatic diseases are a leading cause of disability with significant economic, social, and psychologic impact.4 Between 2003 and 2005, approximately 46 million Americans were affected by arthritis and other rheumatic conditions, with an estimated 19 million experiencing limitations in their ability to participate in daily activities and 8 million limited in their ability to work.21,101 As the population continues to age, the prevalence of arthritis-related conditions is expected to increase to an estimated 67 million by the year 2030, with disability occurring in 25 million people.48

Occupational therapists are likely to encounter clients with rheumatic diseases in their practice settings, whether the condition is manifested as a primary or secondary type. To recognize problem areas and plan effective intervention strategies, the occupational therapist should know the unique features of each disease, its underlying pathology, and its typical clinical findings; the therapist should also be familiar with commonly prescribed medications and their adverse reactions. Given the scope and intended purpose of this book, it is neither appropriate nor possible to adequately describe every rheumatic disease. Therefore, this chapter focuses on two of the most prevalent diseases: OA and RA. Armed with an understanding of the noninflammatory and inflammatory disease processes that they represent, the therapist can apply many of the evaluation and intervention principles to other rheumatic conditions. Table 38-1 provides a quick summary of the contrasting features of OA and RA.4,5,10,29,46,54,94,96,97

TABLE 38-1

Primary Features of Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Osteoarthritis | Rheumatoid Arthritis | |

| Prevalence | Affects 27 million Americans | Affects 1.3 million Americans |

| Peak incidence | Increases with age, <50 years old more common in males and >50 years old more common in females | Ages 40-60, 3 : 1 female-to-male ratio |

| Onset | Usually develops slowly, over period of years | Usually develops suddenly, within weeks or months |

| Systemic features | None | Fever, fatigue, malaise, extra-articular manifestations |

| Disease process | Noninflammatory, characterized by cartilage destruction | Inflammatory, characterized by synovitis |

| Joint involvement | Individual | Polyarticular, symmetric |

| Joints commonly affected | Neck, spine, hips, knees, MTPs, DIPs, PIPs, thumb CMCs | Neck, jaw, hips, knees, ankles, MTPs, shoulders, elbows, wrists, PIPs, MCPs, thumb joints |

| Morning stiffness | <30 minutes | At least 1 hour, often >2 hours |

CMC, carpometacarpal, DIP, distal interphalangeal; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

Osteoarthritis

OA, also referred to as degenerative joint disease, is the most common rheumatic disease and affects approximately 27 million people in the United States.4,46,54 It ranks third among health problems in the developed world.15,52 Its prevalence strongly correlates with age. In fact, evidence of characteristic cartilage damage is almost universal in persons older than 65 years.15 Before the age of 50, men are more likely to have OA; past the age of 50, women predominate.10 In addition to age and gender, risk factors include heredity, obesity, anatomic joint abnormality, injury, and occupation leading to overuse of joints.10 It is interesting to note that because RA may cause malalignment or instability of joints, it often results in premature OA.23

OA is classified as primary or secondary. Primary OA has no known cause and may be localized (i.e., involvement of one or two joints) or generalized (i.e., diffuse involvement generally including three or more joints). Secondary OA can be related to an identifiable cause, such as trauma, anatomic abnormalities, infection, or aseptic necrosis.13,29

OA is a disease that causes the cartilage in joints to break down with resultant joint pain and stiffness. Unlike RA, which is systemic (affecting the entire body), OA limits its attack to individual joints. Also in contrast to RA, the basic process of OA is noninflammatory, although secondary inflammation caused by joint damage is quite common. Once considered simply “wear and tear” arthritis, OA is now thought to involve more than just the passive deterioration of cartilage. The agent that initiates OA is not well understood, but it is known to involve a complex dynamic process of biomechanical, biochemical, and cellular events.54 These are affected by local, systemic, genetic, environmental, and mechanical factors, which directly or indirectly influence the vulnerability of cartilage.10 It is, in essence, the “final common pathway” for a variety of conditions.15

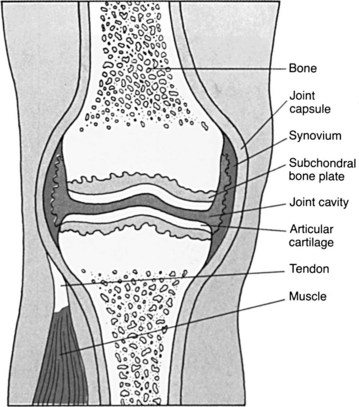

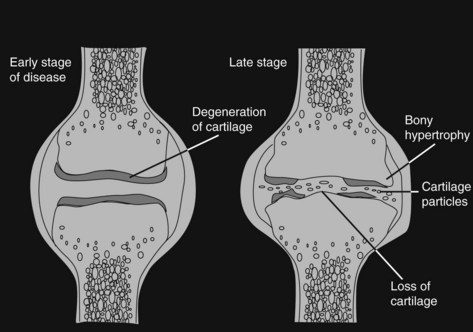

A healthy joint is lined by articular cartilage that is relatively thin, highly durable, and designed to distribute loads and limit stress on subchondral bone (Figure 38-1).15 OA destabilizes the normal balance of degradation and synthesis of articular cartilage and subchondral bone and involves all of the tissues of a diarthrodial (i.e., synovial-lined) joint.10,15 OA is basically a two-part process: deterioration of articular cartilage and reactive new bone formation.65 This breakdown of joint tissue occurs in several stages. First, the smooth cartilage softens and loses its elasticity, which makes it more susceptible to further damage. Eventually, large sections of the cartilage wear away completely and result in reduced joint space and painful bone-on-bone contact. The ends of the bone thicken, osteophytes (bony growths) are formed where ligaments and capsule attach to bone, and the joint may lose its normal shape (Figure 38-2). Fluid-filled cysts may form in the bone near the joint, and bone or cartilage particles may float loose in the joint space.4,64

FIGURE 38-1 Normal joint structures. (From Ignatavicius DD, Bayne MV: Medical-surgical nursing: a nursing process approach, Philadelphia, Pa, 1991, Saunders, p 720.)

FIGURE 38-2 Joint changes in osteoarthritis. (From ARHP Arthritis Teaching Slide Collection, American College of Rheumatology.)

Clinical Features

OA is characterized by joint pain, stiffness, tenderness, limited movement, variable degrees of local inflammation, and crepitus (an audible or palpable crunching or popping in the joint caused by the irregularity of opposing cartilage surfaces).47 It can affect both axial and peripheral joints. The most common joints are the distal interphalangeal (DIP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and first carpometacarpal (CMC) joints of the hand; the cervical and lumbar apophyseal joints; the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints of the feet; and the knee and hip joints.4,29,54 Symptoms are usually gradual and may begin as a minor ache with motion. Pain and stiffness typically occur with activity and are relieved by rest, but eventually they become present at rest and at night. Morning stiffness (lasting less than 30 minutes) and stiffness after periods of inactivity (known as gelling) may develop. With advanced disease, patients may complain of the “bony” appearance of their joint, which is a result of osteophyte formation and possibly muscle atrophy.29,54

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis of OA is initially made on the basis of the patient’s history and physical examination, with a lack of systemic symptoms ruling out inflammatory disorders such as RA. The cardinal symptoms are use-related pain and stiffness or gelling after inactivity. The clinical diagnosis is typically confirmed with radiographs of the affected joint, which will show osteophyte formation at the joint margin, asymmetric joint space narrowing, and subchondral bone sclerosis.29 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to improve diagnostic imaging; MRI is able to more sensitively detect loss of cartilage, osteophytes, and subchondral cysts. The American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for osteoarthritis of the hand are listed in Box 38-1.

Medical Management

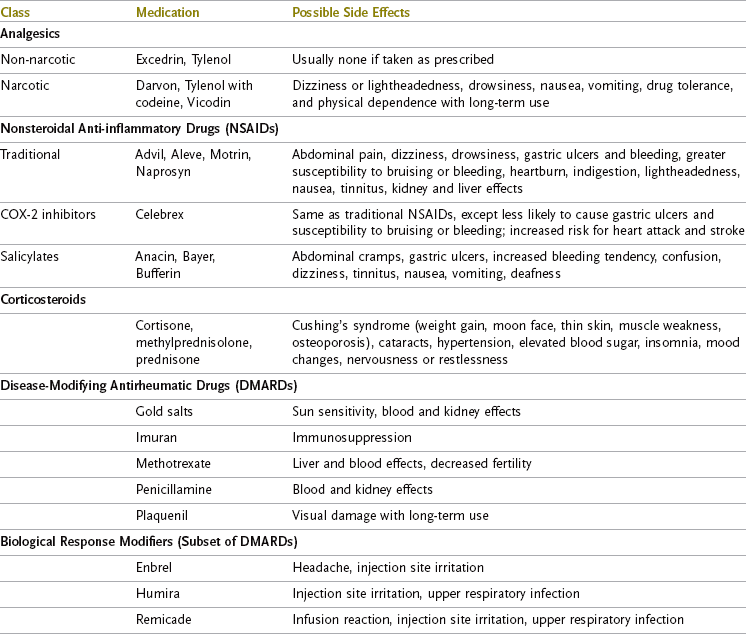

OA currently has no cure. Goals in the treatment of OA are to relieve symptoms, improve function, limit disability, and avoid drug toxicity.54,81 Pharmacologic treatment may be systemic or local. Commonly prescribed systemic medications include analgesic agents and anti-inflammatory agents (Table 38-2).3 Analgesic agents provide relief to painful joints and may be non-narcotic or narcotic for advanced and severe OA that fails to respond to other measures. Anti-inflammatory agents provide pain relief, with the added benefit of decreasing local joint inflammation. Because of the risk for gastrointestinal and renal toxicity, these drugs are typically used when analgesics are ineffective. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors fall into this category. Though proved effective in treating OA, NSAIDs must be chosen and monitored carefully to minimize potentially serious side effects. COX-2 inhibitors are thought to provide clinical benefits similar to NSAIDs but with a lower incidence of gastric problems; however, more experience by prescribing physicians and longer-term use will help better define their role. The withdrawal of two popular COX-2 inhibitor drugs from the market (Vioxx in 2004 and Bextra in 2005) because of links with an increased risk for heart attack and stroke points to the need for further study. The remaining COX-2 inhibitor (Celebrex) now carries a black box warning.3 Local pharmacologic treatment of OA includes topical agents and intra-articular corticosteroid injections, alone or as an adjunct to systemic medications. Among topical agents are aspirin and capsaicin creams, as well as the first topical NSAID approved for treating OA pain (Voltaren gel).3 Cortisone injections in a joint are often limited to fewer than three per year because of the possible risk for progressive cartilage damage.19

Use of nonpharmacologic agents, also known as nutraceuticals, is extremely common in persons with OA as alternative or complementary treatments and seems to be gaining favor in the general public.51,54,74,81 These agents include nutritional supplements such as glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfate. Although they may have some effect in improving symptoms or slowing the progression of OA, studies citing their efficacy have not yet been of optimal quality.54 However, even if their benefits have not been proved convincingly, use of nutraceuticals typically carries little risk. Even so, patients should be aware that supplements are not regulated like prescription medications. Use of complementary and alternative treatments should be discussed with one’s physician to minimize potential negative effects.51

Surgical Management

Operative intervention may be performed to slow joint deterioration, improve joint integrity, restore joint stability, or reduce pain, with the overarching goal of improving the patient’s overall function. Common surgical procedures for OA include arthroscopic joint débridement, resection or perforation of subchondral bone to stimulate the formation of cartilaginous tissue, use of grafts to replace damaged cartilage, joint fusion, and joint replacement.19,54

Rheumatoid Arthritis

RA is a chronic, systemic inflammatory condition that affects approximately 1.3 million Americans.5,46 The etiology of RA is not well understood, other than that a yet-unknown trigger causes an autoimmune inflammatory response in the joint lining of a genetically predisposed host.96,97 Onset can take place at any age, but prevalence does increase with age. The peak incidence occurs between 40 and 60 years of age, with the rate of disease two to three times higher in females.5,94,97 Its onset is commonly insidious, with symptoms developing over a period of several weeks to several months.

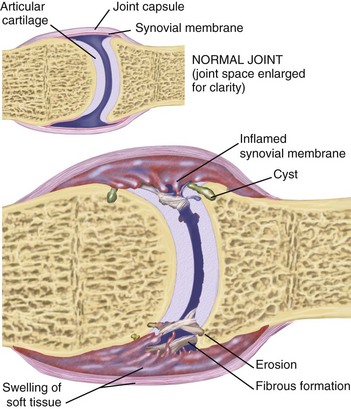

The disease manifests itself as synovitis, which is inflammation of the synovial membrane that lines the joint capsule of diarthrodial joints. The function of normal synovial tissue is to secrete a clear fluid into the joint for the purpose of lubrication.2,23 In RA, synovial cells produce matrix-degrading enzymes that destroy cartilage and bone. Joint swelling results from excessive production of synovial fluid, enlargement of the synovium, and thickening of the joint capsule. This weakens the joint capsule and distends tendons and ligaments. As the inflammatory process continues, the diseased synovial membrane forms a pannus that actively invades and destroys cartilage, bone, tendon, and ligament (Figure 38-3). Scar tissue can form between the bone ends and cause the joint to become permanently rigid and immovable.

FIGURE 38-3 Joint changes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. (From Jarvis C: Physical examination and health assessment, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.)

Articular manifestations of RA fall into two categories: (1) reversible signs and symptoms related to acute inflammatory synovitis and (2) irreversible cumulative structural damage caused by recurrent synovitis over the course of the disease. Structural damage typically begins between the first and second years of the disease and progresses as a linear function of the amount of prior synovitis.35,94 Almost 90% of joints ultimately affected by RA become involved during the first year.77,94 Progressive joint damage in the majority of patients results in significant disability within 10 to 20 years.96

The course of RA is variable from person to person. Approximately 20% of those affected have a single episode of inflammation with a long-lasting remission. The majority of people with RA experience a series of exacerbations and remissions, with periodic flare-ups of inflammation followed by complete or incomplete remissions.63 Outcomes are similarly variable. Patients’ functional abilities vary according to the course of the disease, the severity of the symptoms, and the amount of joint damage. Because RA is a systemic disease, certain extra-articular features occur in about half of patients.94,97 These features include fatigue, rheumatoid nodules, and vasculitis. Ocular, respiratory, cardiac, gastrointestinal, renal, and neurologic manifestations are also seen as secondary complications. Patients with severe forms of RA may die between 10 and 15 years earlier than expected as a result of accompanying infection, pulmonary and renal disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, and especially cardiovascular disease.70

Clinical Features

RA is characterized by symmetric polyarticular pain and swelling, prolonged morning stiffness, malaise, fatigue, and low-grade fever. Joints most commonly affected are the PIP, metacarpophalangeal (MCP), and thumb joints of the hands, as well as the wrist, elbow, ankle, MTP, and temporomandibular joints; the hips, knees, shoulders, and cervical spine are also frequently involved.94,96 Even though joint involvement is bilateral, disease progression may not be equal on both sides. For instance, a patient’s dominant hand may show more severe involvement and different joint changes or deformities than the other hand. Clinical features vary from patient to patient and also in individual patients over the course of their disease. Pain can be acute or chronic. Acute pain occurs during disease exacerbations, or flare-ups. Chronic pain results from progressive joint damage. Synovial inflammation is manifested as warm, spongy, and sometimes erythematous, or red, joints. This is seen in active phases of the disease process. Rheumatoid nodules, a cutaneous manifestation of RA, develop in 25% to 30% of persons with RA during periods of increased disease activity. These soft tissue masses are commonly found over the extensor surface of the proximal end of the ulna or at the olecranon.94,96 Morning stiffness is an almost universal feature of RA. Unlike the shorter-duration stiffness seen with OA, RA morning stiffness can last 1 or 2 hours. It frequently disappears during periods of disease remission. The duration of morning stiffness tends to correlate with the degree of synovial inflammation, and its presence and length are useful measures for monitoring the course of RA.70 Feelings of malaise, fatigue, and depression also fluctuate, with many patients experiencing worse symptoms in the afternoon. These nonspecific symptoms may precede other typical signs of RA by weeks or months.94

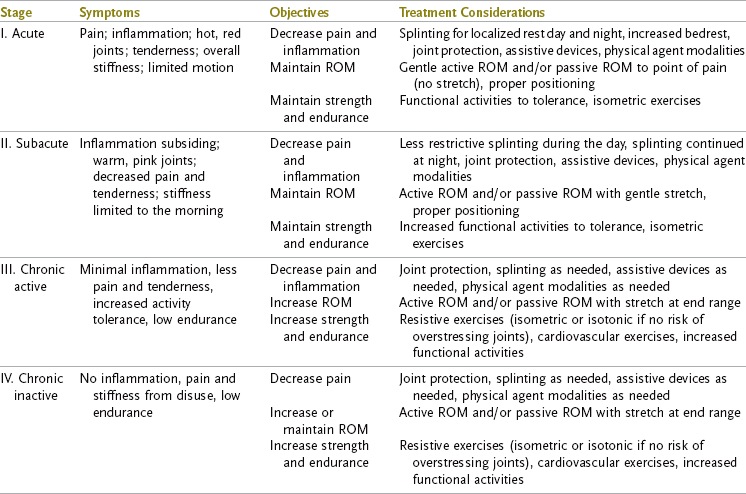

The inflammatory process has been described as having four stages: acute, subacute, chronic active, and chronic inactive.64 Stages may overlap, and patients may move back or forward through them, depending on the course of their disease. Clinical symptoms seen in the acute stage include limited movement; pain and tenderness at rest that increase with movement; overall stiffness, weakness, tingling, or numbness; and hot, red joints. In the subacute stage, the limited movement and tingling remain. A decrease in pain and tenderness indicates that the inflammation is subsiding. Stiffness is limited to the morning, and the joints appear pink and warm. The chronic active stage is characterized by less tingling, pain, and tenderness and increased tolerance of activity, although endurance remains low. No signs of inflammation are present in the chronic inactive stage. The patient’s low endurance and pain and stiffness at this stage result from disuse. Overall functioning may be decreased as a result of fear of pain, limited range of motion (ROM), muscle atrophy, and contractures.64

The characteristic joint deformities will develop as late manifestations of the disease in more than 33% of patients with RA. Deformity of the small joints of the hand will develop within the first 2 years in more than 10%.96 Wrist radial deviation, MP ulnar deviation, and swan neck and boutonnière deformities of the digits are the joint changes most often seen. Joint changes, or deformities, can result from a variety of mechanisms, including joint immobility, destruction of cartilage and bone, and alterations in muscles, tendons, and ligaments.97 Tenosynovitis (inflammation of the tendon sheath) and the presence of nodules within the flexor tendon sheaths can cause trigger finger. Patients may also exhibit symptoms of nerve compression of the median or ulnar nerves at the wrist. Tendon rupture may also be seen, usually in the extensor tendons of the fifth, fourth, and third digits. Stages of the disease based on joint deformity and radiographic changes are defined in Box 38-2.

Diagnostic Criteria

No single test leads to a definitive diagnosis of RA. Diagnosis is based on clinical evaluation of characteristic signs and symptoms, laboratory findings, and radiologic findings.70,94,96 The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification of RA require that the patient demonstrate at least four of seven criteria for a diagnosis of RA to be made (Table 38-3). A positive laboratory test is not necessary to establish a diagnosis of RA, but such tests may help confirm the clinical impression. Rheumatoid factor is an antibody found in the blood serum of approximately 85% of persons with RA, but it can also be found in other inflammatory diseases associated with synovitis. The presence of rheumatoid factor correlates with increased severity of symptoms and increased systemic manifestations. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate correlates with the degree of synovial inflammation and is useful in ruling out noninflammatory conditions such as OA and tracking the course of inflammatory activity.94,96 Radiographs may show nothing other than soft tissue swelling early in RA, but in more than half of patients, radiographic changes will develop within the first 2 years after onset of the disease.70,94,96

TABLE 38-3

American College of Rheumatology Criteria for Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Criterion | Definition |

| Morning stiffness | Morning stiffness occurs in and around the joints and lasts at least 1 hour before maximal improvement |

| Arthritis of three or more joint areas | At least three joint areas simultaneously have had soft tissue swelling or fluid (not bony overgrowth alone) observed by a physician. The 14 possible areas are right or left PIP, MCP, wrist, elbow, knee, ankle, and MTP joints. |

| Arthritis of hand joints | At least one area is swollen (as defined above) in a wrist, MCP, or PIP joint |

| Symmetric arthritis | Simultaneous involvement of the same joint areas (as defined in the second example) occurs on both sides of the body (bilateral involvement of PIPs, MCPs, or MTPs is acceptable without absolute symmetry) |

| Rheumatoid nodules | Subcutaneous nodules over bony prominences or extensor surfaces or in juxta-articular regions are observed by a physician |

| Serum rheumatoid factor | Abnormal amounts of serum rheumatoid factor are demonstrated by any method for which the result has been positive in <5% of normal control subjects |

| Radiographic changes | Radiographic changes are typical of rheumatoid arthritis on posteroanterior hand and wrist radiographs and must include erosions or unequivocal bony decalcification localized in or most marked adjacent to the involved joints (osteoarthritic changes alone do not qualify) |

For classification purposes, a client shall be said to have rheumatoid arthritis if he or she has satisfied at least four of these criteria. The first four criteria must have been present for at least 6 weeks. Patients with two clinical diagnoses are not excluded. Designation as classic, definite, or probable rheumatoid arthritis is not to be made.

MCP, metacarpophalangeal; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

From Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al: The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis, Arthritis Rheum 31:315, 1988.

Medical Management

RA currently has no known cure. The major goals in the treatment of RA include (1) reducing pain, swelling, and fatigue; (2) improving joint function and minimizing joint damage and deformity; (3) preventing disability and disease-related morbidity; and (4) maintaining physical, social, and emotional function while minimizing long-term toxicity from medications.70,96 Maintaining normal joint anatomy can be accomplished only by controlling the disease before irreversible damage occurs. Major advances in the treatment of RA have occurred over the past several years as a result of improved understanding of the pathogenetic mechanisms of the disease, development of therapies that more specifically target the pathophysiologic processes, and recognition that early initiation of aggressive drug therapies can alter the outcome and reduce the severity and disability of RA.70,96

Drug categories used for RA include NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs; see Table 38-2).3 Because the fast-acting NSAIDs can decrease joint pain and swelling but cannot alter progression of the disease, they are rarely, if ever, used alone for the treatment of RA. The anti-inflammatory effects of the large number of medications in this category are about equal. COX-2 inhibitors show no evidence of greater efficacy than other NSAIDs but are thought to pose a lower risk for serious gastrointestinal side effects.94 Corticosteroids have a long history in the medical management of RA and still remain a key element. They produce rapid and potent suppression of inflammation with improvement in joint pain and fatigue. Because of the significant adverse effects of corticosteroids, they are frequently used on a temporary basis in patients with active disease and significant functional decline while awaiting the full therapeutic effect of DMARDs. DMARDs lack a pain relief effect, but they may actually affect the course of the disease. Because of their slow-acting nature, weeks or months of drug therapy may be necessary before a clinical benefit is recognized. The potency of these drugs requires that patients be closely monitored for side effects.

Traditionally, the approach to treatment of RA began with less toxic medications such as NSAIDs and progressed to the stronger drugs needed later in the disease course. The approach is now more aggressive, with early use of DMARDs to control the disease process as soon as possible, as completely as possible, and for as long as possible.70,103 Drug therapy constantly changes, depending on the patient’s needs and response to treatment, as well as the physician’s treatment philosophy. This uncertainty can be frustrating for the patient, who may have to experiment with myriad new medications when current drugs become ineffective or side effects too severe. It is important for the occupational therapist and other team members to know the specific medications that the patient is taking and what adverse reactions may arise.

Surgical Management

Because of the extensive joint damage caused by RA, surgical intervention is frequently indicated to relieve pain and improve function. Several surgical procedures may be of benefit to patients with RA. Synovectomy (excision of diseased synovium) and tenosynovectomy (removal of diseased tendon sheaths) are performed to relieve symptoms and slow the process of joint destruction, but they do not prevent progression of the disease. These procedures are most commonly performed in the wrist and hand. Tendon surgery, including relocation of displaced tendons, repair of ruptured tendons, and release of shortened tendons, may be performed to correct hand impairments. Tendon surgery occurs most frequently on the extensor tendons of the wrist and hand. Tendon transfers and peripheral nerve decompression (such as carpal tunnel release) are also performed to optimize function. Arthroplasty (joint reconstruction) and arthrodesis (joint fusion) are options when joint restoration is not possible. These procedures may be performed to relieve pain, provide stability, correct deformity, and improve function. Common sites for arthroplasty include the hip, knee, and MCP joints. Common sites for arthrodesis include the wrist, thumb MCP and interphalangeal (IP) joints, and cervical spine.19,64

Occupational Therapy Evaluation

It is important to recognize that every client with arthritis has a unique manifestation of clinical problems and functional impairment. A strong client-centered and occupation-based approach is helpful in determining each client’s specific needs. The evaluation process for clients with arthritis includes many of the same elements as for any physical disability. Special considerations related to arthritis include closer attention to pain, joint stiffness, joint changes/deformity, fatigue, and coping strategies, especially as they relate to limitations in activity. Because clients with arthritis typically experience good days and bad days, many symptoms and problems are unpredictable. Thorough systematic assessment of the client’s functional, clinical, and psychosocial status is key to prioritizing problems and planning effective intervention.

The extent of specific components of the evaluation will often be driven by the main reason for referral. Clients seen for preoperative hand assessment, postoperative hip replacement, education after diagnosis, splinting while in a flare-up, or a decline in functional status will all require the therapist to customize evaluation priorities.

Because of the chronic nature of rheumatic diseases, some clients are able to clearly state their specific needs and should be afforded the opportunity to do so. Other clients may be overwhelmed by multiple problems or a newly made diagnosis and will look to the therapist to guide the intervention process. Regardless of the client’s status, close collaboration and partnership among the client, family, therapist, and other team members is crucial in helping deliver the best treatment possible.

The occupational therapy (OT) evaluation process consists of (1) a client history; (2) occupational profile; (3) occupational performance status; (4) cognitive, psychologic, and social status; and (5) clinical status.

Client History

A thorough history should be obtained through review of the client’s report and medical record. Important details include diagnosis, dates of onset and diagnosis, secondary medical conditions, current medications and medication schedule, alternative or complementary therapies, and surgical history.85 Asking the client questions such as “What type of arthritis do you have?,” “How long have you had it?,” “What medications are you currently taking?,” and “What other things are you doing to manage your arthritis?” can provide helpful insight regarding the client’s level of understanding about his or her condition, medical treatment, and health habits. Previous experiences with OT and physical therapy should also be ascertained to build on them. The therapist must ask and actively listen to the client’s current primary complaints through questions such as “What is bothering you most about your arthritis?,” “How is your arthritis limiting your ability to do things right now?,” and “What are you hoping therapy can help you with?”

This was Nina’s first referral to OT. She was knowledgeable about her diagnosis and medications but uncertain about the potential benefits of therapy. Through her responses to key questions, Nina was able to clearly state that her pain and difficulty performing household and work activities were her main priorities.

Occupational Profile

It is helpful to begin the process of assessing occupational performance with an occupational profile. Obtained through an open-ended interview, the profile yields important details about the client’s previous and current roles, occupations, overall activity level, and ability to participate in meaningful activities. It can also provide insight into the client’s sense of self-efficacy, adjustment to disability, and themes of meaning in his or her life.55,62 An effective method to obtain a client’s occupational profile is to have the client describe how he or she spends a typical day. This typical-day assessment allows the therapist to become familiar with the client’s routines, use of time, sleep/wake habits, energy and fatigue patterns, important people and environments, activity contexts, and other details that may not otherwise come up in conversation. Because arthritis involves fluctuant symptoms, the client should be asked to describe how time is spent on a good day and a bad day so that the therapist can compare the two and understand how arthritis affects the client’s daily life and how effectively the client is able to balance activity and rest. It is helpful to ask the client to estimate the percentage of good versus bad days per week or month. It may also be advantageous to explore time spent on weekend days versus weekdays; the client may reveal other occupations, such as those involving spirituality, social participation, and leisure. This fluid dialog also serves to develop rapport, establish the client as the valued expert in his or her occupations and lifestyle, and frame the role of OT in the client’s rehabilitation.

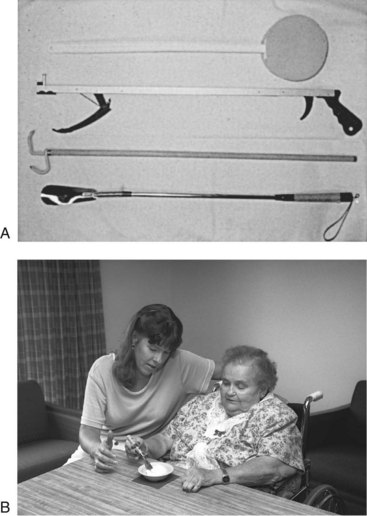

Occupational Performance Status

Once the client’s typical and preferred occupations are identified, his or her level of independence engaging in these functional activities can be assessed by interview or by observation. If observation is used, the activity should occur as close as possible to the time that it is normally performed because the client’s abilities may fluctuate at different times of the day. For instance, stiffness and pain may make dressing very difficult in the early morning, but if this task is assessed in the afternoon, the client’s status may appear much better. Ideally, the activity should also be done in the client’s own home, community, or work contexts.7 In addition to assessing the client’s level of independence during activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), school, work, sleep and rest, play, leisure, and social engagements, it is important to note any assistive devices (e.g., mobility aids or adaptive equipment) and compensatory techniques that the client may use. The activity demands of the occupation performed (e.g., tools, equipment, and skills required), as well as the specific contexts in which it is performed (e.g., the client’s living situation, others in the home, and architectural set-up relative to occupational performance), should be detailed in tandem with existing physical, environmental, or social barriers. Finally, the amount of time required to complete certain activities should be explored. A client who experiences significant morning stiffness or limited endurance often chooses to accept assistance in an activity such as dressing to save time or conserve energy to participate in a more meaningful occupation later in the day. This strategy may contribute to the client’s overall satisfaction with and participation in life, and it should be respected as such.

In RA, functional status may be classified according to the American College of Rheumatology’s revised criteria for the classification of functional status in clients with RA (Table 38-4). This system was devised for rapid, global assessment of functional status by health professionals.47 The therapist should be familiar with this system because it is often used in clinical research and can provide a general framework for defining advancing disability.43,106 Nina would be considered class III because of limitations in her work activities.

TABLE 38-4

American College of Rheumatology Classification of Global Functional Status in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Classification | Description |

| Class I | Completely able to perform usual activities of daily living (self-care,* vocational, and avocational) |

| Class II | Able to perform usual self-care and vocational activities, but limited in avocational activities |

| Class III | Able to perform usual self-care activities, but limited in vocational and avocational activities |

| Class IV | Limited in ability to perform usual self-care, vocational, and avocational activities |

*Usual self-care activities include dressing, feeding, bathing, grooming, and toileting. Avocational (recreational or leisure) and vocational (work, school, homemaking) activities are client desired and age and sex specific.

Courtesy American College of Rheumatology ©2004.

A decrease in occupational functioning in clients with arthritis may be due to pain, joint changes or instability, loss of motion, weakness, fatigue, change in the living environment, or change in social support, among other contributing circumstances. The effects of medication can also limit performance. The challenge for the therapist is not only to identify deficits in occupational performance but also to determine the factors that are causing them. Asking the client why an activity cannot be done yields the important client perspective.7 Nina was having difficulty with many occupations, including sleeping, playing actively with her grandchildren, managing her home, and performing her job to her level of satisfaction. She reported having to give up or cut back on activities because of increased pain, stiffness, and fatigue from her recent flare-up.

Cognitive, Psychologic, and Social Status

The effects of arthritis are not merely physical and functional. Clients with arthritis should be screened for cognitive and psychosocial deficits. Although arthritis does not directly affect cognition, pain, sleep disturbances, depression, and medication can all have profound effects on attention span, short-term memory, and problem-solving skills.64 People with a chronic illness must develop coping strategies to deal with the disability. Coping strategies are particularly crucial for persons with arthritis, who may face serious changes in physical function, life roles, and appearance because of deformity and pharmacologic side effects. Because arthritis is both unpredictable and painful, normal responses to the disability include depression, denial, need to control the environment, and dependence. Psychosocial adaptation is affected by the complex interplay of physical, psychologic, and situational factors.55,72 Approximately 20% of persons with RA are estimated to suffer from major depression.28 About half of individuals with RA or OA may experience loss of social relationships.105 Constant pain and fear of pain, changed body image, perception of self as a sick person, continuous uncertainty about the course and progression of the disease, sexual dysfunction, altered roles, and loss of income resulting from inability to work can lead to significant psychologic stress.55,72 Evidence has shown that the disability associated with RA relates to psychosocial factors almost to the same extent as to biomedical factors.32 Occupational therapists must understand the ways in which their clients manage stress in their lives because these stressors may exacerbate the disease.55 Family relationships and cultural backgrounds also affect the client’s health care behavior and response to disability.76 The therapist should be sensitive to all factors that will influence rehabilitation. Referral to other health professionals (such as psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers) should be made if needed.72

Nina reported that she had increasing difficulty concentrating on tasks because she was unable to get adequate restful sleep. She expressed frustration about her inability to keep her house in order and anxiety about losing income because she was unable to work her customary hours. She was also fearful about her health because her arthritis had been adequately controlled for the past few years and she had not experienced any flares.

Clinical Status

For clients with arthritis, the elements of inflammation, ROM, strength, hand function, stiffness, pain, sensation, joint instability and deformity, physical endurance, and functional mobility should be included through either brief screening or detailed evaluation. As with assessment of function, the time of day and anti-inflammatory or analgesic medications taken should be noted because these factors may influence the results. In addition, future re-evaluations should be performed under the same conditions.64 When the client’s functional deficits are identified first, assessment of client factors can be much more focused. Additionally, asking the client a question such as “What joints are you having the most problems with?” can help prioritize assessment needs. Given Nina’s initial findings, the detailed evaluation focused primarily on synovitis, pain, stiffness, ROM, strength, physical endurance, and functional mobility. Even though joint deformities were not immediately evident, the therapist was careful to search for signs of instability that would place Nina’s joints at risk for deformity.

The clinical evaluation may take considerable time. It should be approached in a systematic manner with the results clearly documented. The occupational therapist may need to perform assessments over several sessions, especially if the client is experiencing significant pain or fatigue. Intervention can begin immediately and does not necessarily depend on completion of the evaluation. The evaluation actually begins with a general observation of the client’s posture, willingness to move, and pain behavior during the initial interview.

The presence and location of inflammation or synovitis should be noted because these signs indicate an active disease process. Several types of swelling may be present and should be described. An effusion (excess fluid in the joint capsule) is seen as fusiform swelling that is spindle shaped and conforms to the shape of the joint. Boggy swelling is thin and full of fluid. Puffy, spongy, and soft to the touch, boggy swelling is seen in the early active stages of synovitis. Chronic synovitis feels firm because the joint fills with synovial tissue.64

Active and passive ROM can be measured. Depending on the reason for referral and the client’s complaints, the therapist may not find it necessary to obtain goniometric measurements of all joints but instead focus only on the joints of most concern. Active motion will allow the therapist to see the amount of mobility that the client has available for function, whereas passive motion will elicit the joint’s capacity to move. The client’s range of active motion may be significantly less than the range of passive motion; this is known as lag and is caused by pain, weakness, or the mechanical inefficiencies attributable to joint damage. Goniometric measurement of hand joints may be difficult in the presence of deformity. Assessment of composite (combined motion of all joints) flexion, composite extension, and thumb opposition can provide more functional information.11 Active opening and closing of the hand can be measured by the distance from the fingertips to the tabletop in maximal extension (opening) when the dorsal side of the hand is resting on the table and by the distance from the fingertips to the distal palmar crease (closing). While performing the ROM assessment, the therapist should note whether the client’s joints feel stiff or unstable. A hard end-feel in the presence of contracture indicates bony blockage.65 A firm end-feel that still has some give indicates that the joint capsule or ligaments are limiting motion.45 The presence and location of crepitus, along with the motions that cause it, should also be noted because crepitus often indicates extensive joint damage. The source of crepitation may be bony, synovial, bursal, or tendinous (see Chapters 20 through 22 for additional information).11,64

Gross strength should be assessed with more specific manual muscle testing as indicated. One important detail to understand is that strength testing in clients with arthritis differs from normal testing procedures. Resistance is applied at the end range of pain-free motion rather than at the true end of the ROM. It is not unusual for clients with arthritis to have pain in the last 30 to 40 degrees of joint motion. When resistance is applied within the pain-free range, inhibition of muscle strength by pain will be avoided. It is also important to consider joint protection principles when applying resistance and to discontinue resistance if the client experiences pain. If use of resistance is contraindicated (as may be the case in an acute or active phase of arthritis, in which resistance may be harmful to inflamed tissue and joints), functional muscle or motion testing may be substituted.64

Hand strength and function are important to test, but care must be taken to not stress painful or vulnerable joints during assessment. Grip and pinch may be measured by standard meters, but in the presence of severe weakness or hand deformity, adapted methods, such as use of a blood pressure cuff to measure force in millimeters of mercury, may be indicated.11,64 Although it is more comfortable for the client, the results of strength testing in this manner are less reliable, with no established norms. Other specific devices for measuring grip strength in hands with arthritis, including pneumatic bulb dynamometers, are commercially available. As a result of joint deformity, the client may not be able to assume the standard testing positions for lateral and palmar pinch. Because it is important to assess pinch strength relative to function, pinch should still be tested, with notation made of the client’s prehensile pattern (e.g., “4 pounds of pinch with meter placed in web space between thumb and second metacarpal”). The presence and location of muscle atrophy should be recorded because it indicates severe weakness and possible nerve compression that may require further investigation. Intrinsic atrophy can be seen as flattening of the thenar and hypothenar eminences and as hollowing between the metacarpals on the dorsal aspect of the hand.

Hand function can be assessed through standardized tests (e.g., the Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test)50 or observation of the client performing common functional tasks that involve various grasp and prehensile patterns. These tasks can include opening a medication bottle, writing, holding a glass, picking up small pins, turning a doorknob and key, cutting with a knife, and fastening buttons. In addition to noting whether the client is able to perform each task, the value of this testing lies in observation of how the client uses his or her hands and determination of which factors interfere most with activity: instability, lack of motion, deformity, pain, weakness, or something else. The therapist cannot predict function solely on the basis of the hand’s appearance. Deformities caused by arthritis often develop slowly, and many clients learn how to adapt their hand function gradually over time. It may be surprising to see significantly deformed hands performing tasks with relatively good function. The therapist should remember this when planning an intervention because it might eliminate a problem that is actually functional for the client.

Joint stiffness is a distinct feeling of excessive stiffness that eventually wears off.64 It can occur as a result of low-grade inflammation, effusion, synovial thickening, muscle shortening, or spasm.12,65 The therapist can determine the extent of joint stiffness by asking the client which joints experience stiffness, under what conditions, and for how long. Morning stiffness and gelling should be considered separately and can be measured in hours or minutes. The duration of morning stiffness is often used as an objective indicator of the degree of disease activity present. The gelling phenomenon, stiffness after prolonged periods of inactivity, is so named because fluid in the joint and surrounding tissues sets up like gelatin.65

Because pain is often the primary clinical manifestation of arthritis, it should be closely evaluated. Pain that interferes with the client’s ability to engage in occupations should be of primary concern. The presence and location of joint pain should be noted. To elicit important details, the therapist should ask questions such as “When does the pain occur?,” “What tends to make the pain worse?,” and “What seems to make the pain better?” An attempt should be made to distinguish between articular (joint) pain and periarticular (soft tissues surrounding the joint) pain. Secondary conditions such as tendonitis and bursitis are frequent causes of pain. Pain has different meanings for individuals and is often difficult to describe.86 The therapist can obtain measurements of pain intensity by asking the client to rate the pain on a numerical scale of “1” (no pain) to “10” (greatest pain) or on a visual analog scale in which the client places a mark along a 10-cm line.49 These scales can also be used to measure other subjective symptoms, including fatigue and degree of stiffness.42 Because pain related to arthritis is fluctuant, the client may be asked to rate pain at its current level, at its best, at its worst, and at various times of the day or to compare pain at rest versus pain with motion or activity. Interestingly, pain caused by acute inflammation in the early stages of RA tends to be greater than pain at the end stages, when severe deformities are present.11 The presence and location of joint tenderness should also be noted. Tenderness is assessed by applying manual compression to the medial/lateral aspects of the joint (see Chapter 28 for additional information).64

Sensation should be evaluated if the potential for peripheral nerve damage or compression caused by swelling exists. The therapist should obtain a subjective report from the client with regard to the presence of numbness or tingling. This report can be followed by screening of the touch/pressure threshold of the fingertips with monofilaments.8 If sensory impairment is noted, further assessment may be indicated. This may include provocative tests to replicate or aggravate symptoms so that areas of compression can be localized. Examples of these tests are the Phalen and Tinel tests in individuals with suspected median nerve compression at the carpal tunnel.6 When cervical spine involvement is known or suspected, dermatomal light touch, sharp-dull sensation, and proprioception should be evaluated (see Chapters 23 and 39 for additional information).

The examiner assesses joint laxity (instability) by applying stress to individual joints in the medial/lateral and anterior/posterior directions. When testing medial/lateral stability of the MCP joints, the examiner must first place the MCP joints in flexion to tighten the collateral ligaments, which are naturally loose during MCP extension. Unstable joints should be noted. Ligamentous laxity can be described as slight (5 to 10 degrees in excess of normal), moderate (10 to 20 degrees in excess), or severe (20 or more degrees in excess).64 In the hand joints, instability with medial/lateral motion indicates laxity of the collateral ligaments, whereas excessive anterior/posterior motion is caused by laxity of the joint capsule and volar plate. Normal joint stability is highly variable, and whenever possible, it is helpful to compare it to the client’s uninvolved joints.64

Evaluation of joint deformities is done primarily by observation and palpation. The location and type of deformity should be noted. Comparison with previous evaluations, if available, allows the therapist to see how the deformities have progressed over the course of the disease. If a deformity is correctable, either actively or passively, it is considered flexible; if the deformity cannot be reduced, it is considered fixed. Patterns of deformity can be different in a client’s two hands, and a person with RA can also exhibit deformities caused by osteoarthritic joint damage.

Common hand deformities in persons with arthritis include the following:

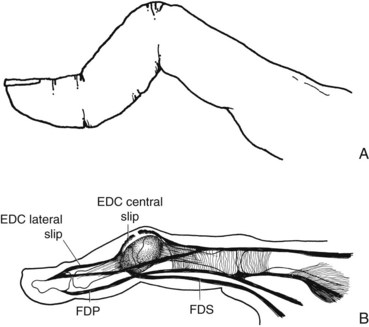

• A boutonnière deformity is characterized by flexion of the PIP joint and hyperextension of the DIP joint (Figure 38-4). This zigzag collapse represents an alteration in muscle-tendon balance. Pathology begins at the PIP joint with secondary changes in the DIP joint. It occurs when synovitis weakens, lengthens, or disrupts the dorsal capsule and central slip of the extensor mechanism and consequently causes incomplete or weak to absent extension at the PIP joint. The lateral bands of the extensor mechanism displace volarly below the axis of the PIP joint and become flexors of that joint. Increased force on the lateral bands at the DIP joint, where they insert, causes hyperextension. Function of the finger is compromised by the inability to straighten the finger and the loss of flexion at the fingertip for pinching.2,11,64

FIGURE 38-4 A, A boutonnière deformity results in distal interphalangeal hyperextension and proximal interphalangeal flexion. B, Boutonnière deformity caused by rupture or lengthening of the central slip of the extensor digitorum communis tendon.

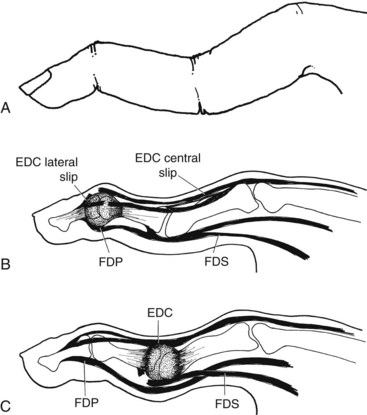

• A swan neck deformity is characterized by hyperextension of the PIP joint and flexion of the DIP joint, with possible flexion of the MCP joint (Figure 38-5). This zigzag collapse is also a result of muscle-tendon imbalance and joint laxity. It can originate from abnormalities at any finger joint. Causes of this deformity include intrinsic muscle tightness, stretching or rupture of the terminal extensor tendon at the DIP joint, and chronic synovitis that leads to stretching of the volar capsular supporting structures at the PIP joint. Here, the lateral bands of the extensor mechanism slip above the axis of the PIP joint, thereby hyperextending the PIP joint and flexing the DIP joint. Function of the finger is compromised by inability to flex the PIP joint, with loss of the ability to make a fist or hold small objects.2

FIGURE 38-5 A, A swan neck deformity results in proximal interphalangeal hyperextension and distal interphalangeal flexion. B, Swan neck deformity resulting from rupture of the lateral slips of the extensor digitorum communis tendon. C, Swan neck deformity as a result of rupture of the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon.

• A mallet finger is characterized by flexion of the DIP joint. This is caused by rupture of the terminal extensor tendon as it crosses the DIP joint. The finger loses the ability to extend the distal phalanx.

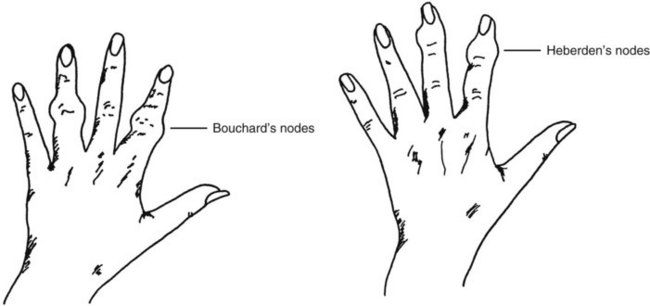

• Nodes are bony enlargements that indicate cartilage damage caused by OA. Joints affected by RA can also have degenerative joint disease, so nodes may be seen in clients with RA as well. These osteophytes are hard to the touch and are typically not painful. They are most commonly seen at the DIP joint (Heberden’s nodes) and the PIP joint (Bouchard’s nodes; Figure 38-6).11,15,64,65

FIGURE 38-6 Osteophyte formation in the proximal interphalangeal joints (Bouchard’s nodes) and the distal interphalangeal joints (Heberden’s nodes) is a common finding with osteoarthritis.

• Nodules are granulomatous and fibrous soft tissue masses that are sometimes painful. They usually occur along weight-bearing surfaces such as the ulna or at the olecranon (Figure 38-7) and can be prognostic of the severity of RA.11

FIGURE 38-7 Rheumatoid nodules present on the extensor surface of the elbow. (From Jarvis C: Physical examination and health assessment, ed 4, Philadelphia, Pa, 2004, Saunders.)

• Deviation is characterized by a change in the normal joint position. It is typically described as radial or ulnar. In RA the most common pattern of deviation is radial deviation of the wrist and ulnar deviation (commonly referred to as ulnar drift) of the MCP joints (Figure 38-8). Deviation is caused by ligament weakening or disruption. Small joints are especially vulnerable because daily activities involving gripping and pinching apply strong forces to them.2,11,64

• Subluxation is characterized by volar or dorsal displacement of joints. It is any degree of malalignment in which the articular structures are only in partial contact. In RA the most common sites of subluxation are the wrist and MCP joints.64 Volar subluxation of the wrist occurs as the carpal bones slip relative to the distal end of the radius as a result of weakening of the supporting ligaments by chronic synovitis. Because of their condyloid nature, the MCP joints have more planes of movement and are inherently less stable than the IP joints. Volar subluxation of the MCP joints occurs frequently and is often accompanied by ulnar drift and lateral displacement of the extensor tendons into the ulnar valleys between the metacarpal heads (Figure 38-9).2,11,64

FIGURE 38-9 Volar subluxation and ulnar deviation of the metacarpophalangeal joints with lateral displacement of the extensor tendons characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis. (From Alter S, Feldon T, Terrono AL: Pathomechanics of deformities in the arthritic hand and wrist. In Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, et al, editors: Rehabilitation of the hand and upper extremity, ed 5, St Louis, Mo, 2002, Mosby, p 1550.)

• Dislocation is characterized by joints whose articulating surfaces are no longer in contact. In severe cases of RA, volar dislocation of the carpals on the radius or dislocation of other joints can result from complete destruction of ligamentous integrity.11,64

• Ankylosis (fusion of the bones of a joint) is characterized by lack of joint mobility. This spontaneous joint fusion can be bony (caused by ossification within or around the joint) or fibrous (caused by growth of fibrous tissue around the joint).64

• Extensor tendon rupture is characterized by the inability to actively extend a joint in the absence of muscle weakness (Figure 38-10). The extensor digiti minimi is often the first to rupture. The extensor pollicis longus and extensor digitorum communis of the third, fourth, and fifth digits are also vulnerable.11 Tendon rupture can occur as a result of rubbing of the tendon over rough bony surfaces or tendon damage caused by direct synovial invasion or increased pressure that decreases blood supply to the tendon.

FIGURE 38-10 Extensor tendon rupture of the fourth and fifth digits resulting in loss of active extension. Tenosynovitis of the extensor tendons and volar subluxation of the wrist caused by rheumatoid arthritis are contributing factors. (From Harris ED, Budd RC, Genovese MC, et al: Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, Pa, 2005, Saunders.)

• Trigger finger is characterized by inconsistent limitation of finger flexion or extension. It is often caused by a nodule on a flexor tendon or stenosis of a tendon sheath, which impedes the tendon’s ability to glide.64 The client often experiences “catching” or “locking” of a finger into flexion and has to passively extend the finger out of the flexed position.

• Mutilans deformity is characterized by very floppy joints with redundant skin (Figure 38-11). The cause is unknown, but the result is resorption of the bone ends, which shortens the bones and renders the joints completely unstable. This is most commonly seen at the MCP and PIP joints of the hands and the radiocarpal and radioulnar joints of the wrist.64

FIGURE 38-11 Mutilans deformity. (From Klippel JH, Dieppe P, Ferri FF: Primary care rheumatology, St Louis, Mo, 1999, Mosby.)

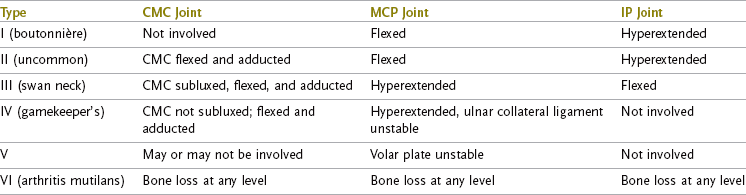

• Thumb deformities can be manifested as any of the deformities previously described. Six patterns of thumb deformity have been classified by Nalebuff (Table 38-5).95 Type I is the most common in RA, followed by type III, seen in both OA and RA.64,95 A boutonnière deformity (type I) is characterized by MCP joint flexion and IP joint hyperextension. A swan neck deformity (type III) is characterized by CMC joint subluxation, adduction, and flexion; MCP joint hyperextension; and IP joint flexion. Also common in RA and OA is an adduction contracture of the thumb CMC joint caused by subluxation of the first metacarpal, radial deviation of the MCP joint, or shortening or weakness of intrinsic muscles.65,95 Subluxation causes a characteristic squared appearance of the CMC joint (Figure 38-12). Disruption of thumb biomechanics often leads to significant loss of hand function, especially given the fact that the thumb is thought to account for as much as 60% of hand function.40

Physical endurance can be evaluated by observation during the assessment process and by client report. Pain, weakness, deconditioning, lack of sleep, and emotional stress can all lead to decreased stamina. The pattern and severity of fatigue should be noted.85 Functional mobility, including ambulation, sitting, and standing tolerance and ability to transfer, should be assessed relative to occupational performance.

Goal Setting

The goals of therapy should be determined by careful consideration of the client’s stated goals, the client’s individual needs, and the stage of the disease process. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) is a useful client-centered tool that can be used for setting goals, planning treatment, and measuring outcomes.53 It is designed to detect change in a client’s self-perception of occupational performance over time. It engages the client in defining problems in activity and helps the client more clearly understand the purpose of OT. The COPM involves a semistructured interview in which the client is asked to identify occupations that the client needs to, wants to, or is expected to perform but are not done satisfactorily. Occupational goals in the areas of self-care, productivity, and leisure (based on the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance [CMOP]) are listed, and the client is then asked to rate his or her self-perception of the importance of, current performance of, and satisfaction with performance of each occupation. Through this process of collaboration with the client, occupation-based therapy goals can be identified, priorities determined, and a treatment plan designed to facilitate optimal outcome. The rating process is repeated at time of discharge for outcome purposes. The COPM has been used with people who have arthritis in both inpatient and outpatient settings.7 COPM goals for Nina were to return to work 20 hours a week, to clean her house independently, and to be able to take her grandchildren to the park after school.

Intervention Objectives and Planning

Treatment of clients with arthritis must take into account the progressive nature of the disease.23 The overarching goal of therapy is to decrease pain, protect joints, and increase function. General objectives of OT are to (1) maintain or increase the ability to engage in meaningful occupations; (2) maintain or increase joint mobility and strength; (3) maximize physical endurance; (4) protect against or minimize the effect of deformities; (5) increase understanding of the disease and the best methods of dealing with its physical, functional, and psychosocial effects; and (6) assist with adjustment to disability.64

The intervention plan should be designed for the individual client and based on the stage of disease, the severity of symptoms, general health status, lifestyle, and mutually agreed goals. Given the limited time for therapy, prioritizing treatment is essential. The therapist should focus on addressing the most important factors by answering the following question: “What are the essential interventions necessary to enable the client to function at an optimal level?” It is important to have the client and significant others be active participants throughout therapy. Everyone involved must understand the disease process and the rationale for the intervention methods. Because therapy intervention will most likely be intermittent throughout the client’s course of disease, the client’s ability to follow through with and self-manage interventions at home will greatly influence the ultimate success of treatment.

Table 38-6 outlines some common symptoms, general objectives, and OT interventions typically appropriate for each stage of inflammatory disease; it can be used as a starting point for planning treatment.11,64 Nina was in the subacute stage of her RA flare-up. All six general objectives listed previously were important to address in her OT program.

Occupational Therapy Intervention

Treatment methods useful in the remediation of clinical or functional problems include rest, physical agent modalities (PAMs), therapeutic exercise and activity, splinting, occupational performance training, and client education. It is important to foster the client’s self-efficacy in his or her ability to follow through with treatment at home given the influences of the home contexts because building the client’s confidence will probably lead to the desired behavior. Asking the client a question such as “How certain are you that you can perform this activity at home as well as you did in the clinic?” can provide feedback on the need for further training and practice.58 The interventions chosen should reflect the individual client’s needs and choices whenever appropriate. General treatment precautions related to arthritis are listed in Box 38-3.

Sleep and Rest

Rest should be considered an active means of reducing inflammation and pain. Rest and relaxation can effectively break the vicious cycle of pain, stress, and depression by allowing the body time to heal itself. Rest can be either systemic or local. Whole-body general rest, including recuperative sleep, is necessary for health. However, individuals with arthritis are at risk for sleep problems because of pain and depression.83 During periods of active systemic inflammatory disease, at least 8 to 10 hours of sleep at night and half-hour to 1-hour morning and afternoon rest periods are recommended.9,83 The amount of systemic rest needed varies by individual, from complete bedrest to an extra nap during the day. Localized rest of joints with symptoms of RA and OA may include wearing a splint, avoiding or modifying activity, or positioning during the day or at night to prevent joint stress.23 Repetitive joint loading or motion with activity should be alternated with rest. The effectiveness of rest will be seen as an improved energy level with less joint swelling, pain, and fatigue.

Nina required both general rest for her body and localized rest for her inflamed wrists and hands. It was important to help her realize the physiologic need for rest during recovery from her flare-up. This assurance permitted her to feel less guilty about tasks left undone and enabled her to understand that taking care of herself in the short term would allow her to return to activity in the long term.

Physical Agent Modalities

PAMs may be helpful in relieving pain or in maintaining or improving ROM. Although modality use alone has not been shown to provide sustained benefits in rheumatic disease, clients do report less pain and stiffness from a clinical standpoint.9,11 The most commonly used PAMs are superficial heat and cold agents. Benefits of heat in clients with arthritis include increased blood flow, pain relief, and increased tissue elasticity, with a negative effect of increasing inflammation also possible.16,44 Benefits of cold include reduced inflammation and decreased pain threshold, with possible negative effects of increased tissue viscosity and decreased tissue elasticity causing more joint stiffness.16,44 Heat can be delivered through hot packs, paraffin, fluid therapy, hydrotherapy in a heated pool, and even a warm shower or bath; cold can be delivered through ice packs or gel packs. When selecting the proper modality, the therapist must consider the activity and stage of the disease process. Acutely inflamed joints may be exacerbated by heat, whereas ice may be more helpful in reducing pain and inflammation. In the subacute or chronic stages, heat or cold may be equally effective.16 Nina preferred the use of heat and found it helpful in loosening her joints and lessening her pain. Even though she was in the subacute phase, some inflammation was still present; therefore, her response to heat was closely monitored so that it did not worsen her inflammation. She was educated in the safe use of warm baths and microwave packs at home.

There are some medical conditions associated with rheumatic disease that contraindicate the use of thermal agents. For example, use of cold is contraindicated in clients with Raynaud’s phenomenon, a vasospastic disorder of the digits.16,44 Clients with RA often have unstable vascular reactions to heat and cold that cause greater than normal heat retention with heat agents or increased coldness and stiffness with cold exposure.44 Careful monitoring of client responses to PAMs is crucial. Client preference and ease of home application should also be considered before choosing an agent to use. Home paraffin units, microwave packs, and continuous low-level heat wraps are increasingly accessible and affordable in community stores and thus provide clients with more options.66 Safety should always be a primary concern. Clients and significant others should be carefully instructed in proper application techniques to prevent burns or other tissue damage. Before using any modality, the therapist must fully understand tissue responses and related precautions and be competent in safe delivery of the agent. This typically requires specific education beyond entry-level preparation. Therapists must also adhere to any state licensure or training requirements.

Therapeutic Exercise

The purpose of exercise in the treatment of arthritis is to keep muscles and joints functioning as normally as possible by maintaining muscle strength, preventing disuse atrophy, and maintaining or improving ROM.102 Regular physical activity can also be helpful in alleviating depression.100 It is helpful to find out what exercises the client may already be performing and whether these exercises were suggested by a professional or a well-meaning family member or friend; many self-initiated exercises can be harmful to a person with arthritis. There is no universal exercise program suitable for all clients with arthritis. Exercise programs should be designed with regard to individual client needs and tolerances. As a good rule of thumb, pain lasting greater than 1 or 2 hours after completion of exercise signals a need to modify or decrease an exercise.64,102 General guidelines for exercise in clients with arthritis are to avoid undue joint stress, avoid pain and joint swelling, and work within the client’s comfortable ROM.11,56,102 The client should be taught to perform exercises slowly, smoothly, and with proper technique. The client must also understand the rationale behind the prescribed exercises.102 Exercises to maintain ROM should be performed at least once daily, even during a flare. For RA each major joint should be taken through its full comfortable ROM. This includes the neck and possibly the jaw if symptomatic. The stiffest joints require the most attention. The type of ROM exercise selected depends on the disease activity and location of the joint. Active ROM is typically preferred, with assisted or passive ROM if pain or weakness precludes it. In cases of active synovitis, active ROM can exert more stress on a joint than gentle passive ROM, so passive ROM exercises may be safer.64 Performing shoulder exercises is often easier in a supine position, which eliminates the effects of gravity. The number of repetitions should be weighed against the potential inflammatory response. On good days, 10 repetitions may be appropriate; on bad days, 3 or 4 repetitions within a smaller arc of motion may be indicated.102 If the goal of exercise is to increase joint mobility, active or passive stretch can be incorporated. This is appropriate for the subacute or chronic phases of disease but never for the acute phase.64 Box 38-4 presents general active ROM exercises for RA.

Exercises for strengthening can be dynamic (isotonic) or static (isometric) and should be aimed toward recovery of function.26,64,100 Strengthening must be approached cautiously so that pain is not increased, deforming forces are not created, and joint stability is not compromised. Grip-strengthening exercises, even those using light putty, can impart large forces to unstable hand joints.17 Additionally, this type of dynamic exercise may aggravate joints or pose a risk for potential deformity and in general should be avoided in clients with rheumatoid hand involvement.11 Resistive exercise of any kind should never be performed during periods of acute flare or inflammation but may be used at other stages. Isometric exercises are usually the least painful for clients with RA because they eliminate joint motion and can be as effective or more effective in improving muscle strength and endurance.64 Isometric contractions are generally held for 6 to 12 seconds.26 Programs to maintain strength vary depending on the client’s overall activity level. Clients who are sedentary may require a daily program, whereas clients who are active may need to perform only specific exercises once a week.64 Gradual progression of repetitions or resistance is recommended.100

Exercises to promote general health and fitness are recommended for all adults as part of a healthy lifestyle and should be encouraged in clients with arthritis. Current evidence supports the benefits of aerobic and conditioning exercise for people with hip and knee OA, as well as aerobic and strength training in adults with stable RA.100 Stationary bicycling, walking, and low-impact aerobic dancing, once thought to cause joint damage, have been found to increase flexibility, strength, endurance, and cardiovascular fitness without aggravation of symptoms. T’ai chi has been reported to have positive effects on self-efficacy, quality of life, general health status, pain, stiffness, and physical functioning in older adults with lower extremity OA41,84 and is being used for clients with RA as well.

Whether for ROM, strengthening, or overall conditioning, the occupational therapist should work closely with the client to help ensure that any exercise program can be successfully integrated into the client’s typical daily routine with a proper balance of rest and activity. Exercises should ideally be done when the client feels most limber and has the least pain. Community land- and water-based exercise classes specifically designed for people with arthritis are available through the Arthritis Foundation. They offer the added benefits of social interaction and peer support and have been shown to be safe and effective in increasing fitness and strength and decreasing pain and difficulty in daily functioning.13,88,92

Daily upper body active ROM exercises with gentle stretch and isometric exercises for the shoulders and elbows were prescribed to improve Nina’s motion and strength. It was decided that the best time to perform these exercises was after her morning shower, when she felt less stiff and least fatigued. The therapist recommended that Nina become involved in an Arthritis Foundation exercise class, once her flare subsided, to build her endurance and cardiovascular conditioning. She was interested in joining and planned to attend classes on the days that she worked fewer hours.

Therapeutic Activity

Performance of therapeutic activities offers many benefits, both physical and psychologic. Discussing current and past hobbies or having the client complete an interest survey can help the therapist determine activities that may be most appropriate for the client. New activities may be suggested or previously enjoyed activities reintroduced. A carefully chosen and graded activity can be an effective means of encouraging ROM and strength. When selecting therapeutic activities, the therapist should apply the same principles as with exercise.64 Activities should be nonresistive, avoid patterns of deformity, and not overstress joints; instead, they should offer enough repetition of movement to help improve ROM and strength. The effect of the activity on all joints should be considered.

It is typically recommended that clients with RA not engage in activities that require use of the hand in prolonged static positions. However, sometimes the psychologic benefits of doing activities that one enjoys outweigh the risks involved, especially if the risks can be minimized. Examples of activities that are often frowned on include knitting and crocheting. These activities are truly contraindicated only if there is active MCP synovitis, a developing swan neck deformity, or thumb CMC joint involvement.64 Potential problems may be averted by having the client wear a hand or thumb splint to support the vulnerable joints while performing the activity. Additionally, educating the client to incorporate frequent rest breaks and stretching exercises for the intrinsic muscles will help limit risks (see Chapter 29 for additional information regarding therapeutic exercise and activity).27,64

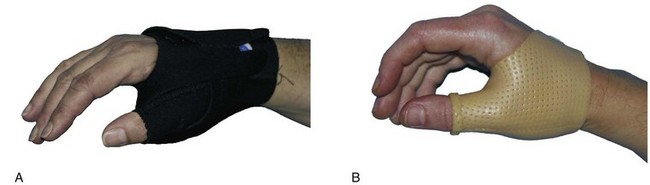

Splinting

Splinting is often an integral component of the treatment of arthritis. Splints can be used for numerous reasons, with the fundamental goal of maximizing function. It is important for the therapist to understand the pathomechanics of the disease process when prescribing an appropriate and feasible splinting plan. Inappropriate use of splints can be harmful. Indications for splinting in clients with arthritis include reducing inflammation, decreasing pain, supporting unstable joints, properly positioning joints, limiting undesired motion, and increasing ROM. Although it is generally agreed that splinting has a place in the acute phase of RA, there are few documented or well-established protocols for splinting in later stages.34 Table 38-7 summarizes the potential splinting indications on the basis of progression of the joint destruction in RA.11,64

TABLE 38-7

Splinting Indications by Classification of Progression of Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Stage | Symptoms/Radiographic Changes | Splinting Indications |

| Stage I: Early | No destructive changes; possible osteoporosis | Resting splints to decrease acute inflammation, decrease pain, protect joints |

| Stage II: Moderate | Osteoporosis with or without slight subchondral bone destruction, slight cartilage destruction, no joint deformities, limited joint mobility possible, muscle atrophy, extra-articular soft tissue lesions possible | Day splints to provide comfort Night splints to relieve pain and/or protect joints against potential deformity Splints to increase ROM |

| Stage III: Severe | Cartilage and bone destruction, joint deformity, extensive muscle atrophy, extra-articular soft tissue lesions possible | Day splints to improve function (decrease pain, provide stability, limit undesired motion, properly position joints) Night splints to provide positioning and comfort |