Therapeutic Occupations and Modalities

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Recognize the organizing concepts of occupational genesis as they relate to active occupation.

2 Discuss the role of activity analysis in the selection of therapeutic activity.

3 Understand the similarities and distinctions between the therapeutic activity and therapeutic exercise.

4 Identify the role of physical agent modalities in occupational therapy practice.

5 Describe how grading activity heightens functional performance.

6 Differentiate between the various types of therapeutic exercise.

7 Describe how and why simulated and enabling activities are used in practice.

8 Describe how and why adjunctive modalities are used in occupational therapy practice.

9 Identify the requirements established by the American Occupational Therapy Association for the use of adjunctive modalities in occupational therapy practice.

10 Perform an activity analysis appropriate for physical dysfunction.

Active Occupation

Active occupations are the foundation of occupational therapy (OT) practice. Active occupations are the activities people engage in as part of their life’s roles. These include personal care; the constructional tasks that involve the use of hand and mechanical tools; technological activities that involve such tools as calculators, computers, and electronics; games of various sorts; and vocational skills. They function together in a complex process, stimulating growth and health throughout the life span.

When physical disability strikes and the ability to perform occupational roles and activities becomes impaired, the occupational therapist (OT) helps clients to regain their skills using active occupations as therapeutic tools to stimulate performance and gears intervention to enable clients to assume or resume their ability to engage in life’s occupations.

Active occupation is the primary therapeutic modality of OT, designed to stimulate function and to lead to improved function, and is relevant throughout the life span. Engagement in activity enhances performance beyond the given task. Learning to perform one activity skillfully leads to skillful performance in other activities. Therefore, active occupations are the objectives and the tools of practice. Activities are the means and the end to heightened performance. Whether related to personal care, work, or leisure, active occupations constitute an effective and substantial portion of any OT program and distinguish OT as a profession.

The needs and interests of clients guide the selection of occupations used for therapy. These needs are governed by the roles clients play in their worlds. As members of society, clients represent the societies in which they perform activities, and the activities in which they engage reflect their worlds. The clients’ needs and interests are tied to the societies in which they live. Therefore, active occupations reflect society’s values. In a society in which independence, leisure, and work all are valued, the interests of clients are variable and include self-care, hobbies, and work-related tasks.

Clients must assume their personal and social obligations to become effective members of society. To assume these responsibilities, clients must acquire the skills needed to perform their occupational roles. The roles people assume reflect their participation in occupations. For persons with disabilities, participation may require relearning skills, learning new skills, or learning to perform activities in new ways. Therefore, the OT must be prepared with a broad knowledge of activities and techniques that may then be used as tools of therapy in a client-centered approach. OTs must understand the roles and activities in which people engage in performing their life’s tasks. As a consequence, OTs must be prepared to meet the challenges that ordinarily occur as people and societies evolve and change. Currently, advances in computer technology are emerging at a rapid rate influencing all aspects of living, and therapy. Some of the tools now available to the public are Skype, Wii, iPad, and others, with new applications and adaptations entering the market daily. The OT must keep appraised of these technological changes and be prepared to incorporate them into therapy, as they are part of patients’ lives.

Just as society changes and adapts with the invention of new objects and methods, so do the activities clients use in their lives. Nowhere is this more readily observed than in an examination of the OT treatment environment. Just as the nature of activity has changed over time as societies have evolved and adapted, the scope of OT’s intervention methods and modalities has changed and broadened considerably over the years.

When the field of OT became formalized in the early 1900s, the nature of human occupation was limited to the scope of activities that had been developed up to that time. Consequently, the use of handicrafts and early industrial tasks guided activity at the outset of the profession. Although commonly described as crafts, these activities can be viewed from an anthropologic perspective, representing the times in which they were developed and in which they met people’s personal and social needs. For example, making baskets and clay pots was not a frivolous activity when they were first designed. Rather, they were vital containers used to gather foods and other items, and the knowledge of how to make them was an important skill. However, times changed, and along with these changes society developed new and different occupations, which require OTs to expand their skills to incorporate activities and techniques of the modern era.

OTs currently are qualified and competent in the use of a variety of therapeutic occupations and modalities, traditional and modern.1 Their competence is derived from entry-level to advanced graduate education, specialty certification, continuing education, and work experience. The scope of practice is broad and addresses the continuum of intervention from wellness to acute care through advanced rehabilitation. Therefore, OT offers comprehensive services and challenges the OT practitioner to keep pace with new developments in society and in practice.

Philosophic Foundations

OTs organize intervention by integrating a comprehensive knowledge of the client’s mind and body (the egocentric realm) with knowledge of the tangible world (the exocentric realm) and the social influences (the consensual realm) that contribute to function. Each of these elements and their components and interactions are reflected in the second edition of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF-2), which is committed to the use of active occupation as the basis for therapy grounded in client-centered choices.

The relationships among these three interactive forces are in constant flux in a lifelong developmental process that is stimulated by active occupation. These forces are evident in the various theories and models of practice OTs draw up for practice.

These foundational ideas stem from the work of John Dewey19 and the other American philosophers of pragmatism whose work influenced the mental hygiene movement, which in turn influenced the founders of the profession.13 Dewey’s use of the terms purposive activity and active occupation, along with his renowned concept of learning through doing, are found in his text Democracy and Education,19 published in 1916 in Chicago, a year before the establishment of the National Society for the Promotion of Occupational Therapy.

Egocentric Realm

Intensive training in the various client factors of motor, neurologic, perceptual-cognitive, and emotional skills prepares the OT with a refined knowledge of what contributes to a client’s performance in all aspects of the mind and body. Mind and body are seen as interactive and together govern performance. Our client, Fareed, has experienced a loss in motor function, as a result of a neurologic insult, which contributes to a loss in occupational performance. This change in abilities has resulted in a reactive depression, which illustrates the interaction between the various egocentric factors.

Exocentric Realm

OTs have an equally refined understanding of the material world, the context in which people live, act, and react. Textures, weights, direction, location, time, and other tangible, contextual, and objective means regulate performance in the world. A person functions within a real world filled with objects and environments that must be manipulated in one manner or another. OTs are expert in adapting the tangible and durable elements of the world to enhance function, including aspects of the electronic virtual world in that process. Returning to our client Fareed, we need to examine the exocentric realm of his world. The task demands of cooking, gardening, woodworking, and traveling require the client to control and manipulate the material world. The task demands of electronic communication and the Wii introduce the virtual world, a reality-based simulation of the material world, into this process. The neurologic insult Fareed experienced compromised his ability to control and manipulate the environmental features and objects necessary to engage in preferred activities.

Consensual Realm

OTs also bring their knowledge of the effects of society and social interactions on individual and group performance. This knowledge is used to enhance clients’ function by effectuation of the roles they play in their social worlds. Recognizing and valuing the sociocultural contexts of occupation and their implications for client performance contribute to the OT’s knowledge base and form a fundamental basis for formulation of the practice environment. Our patient Fareed relies on this social realm in his interactions with his family.

Relationships among Realms

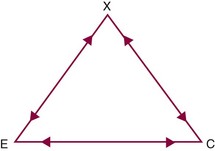

The three major aspects of OT’s knowledge base, the egocentric (mind and body), exocentric (time and space), and consensual (society) realms, are thoroughly integrated in active performance, regardless of interest, purpose, environment, or era.12,13 OTs consider the interactions among these realms to influence or heighten the possibility of the client to engage in occupations (Figure 29-1). For example, a splint (exocentric) can be used to stabilize a wrist to reduce pain (egocentric), enabling the client to prepare a meal for the family (consensual). A walker can be adapted so that a client can carry her knitting (exocentric), allowing her to prepare gifts for her grandchild (consensual) and heighten her feelings of efficacy (egocentric).

FIGURE 29-1 The egocentric (E), exocentric (X), and consensual (C) realms of the OT’s knowledge base are related. (From Breines EB: Occupational therapy from clay to computers: theory & practice, Philadelphia, 1995, FA Davis.)

Development and Evolution

The interaction among these three realms represents a developmental continuum. They influence one another throughout the life span in a process defined as occupational genesis.11 Interactions among physical and mental capacities, the tangible world, and the roles people play in their worlds are reflected and governed by the activities in which people engage throughout their lives.

Intensive preparation in these three realms and their interactions constitute the education and preparation of the OT practitioner and guide the therapist in developing an intervention plan. With this comprehensive foundation, OTs use various modalities to integrate these three realms, which enhances client performance and enables clients to meet life needs.

Evolving Practice

Just as society and its occupations have evolved and continue to evolve, OT practice has evolved. New media and modalities (Box 29-1) have emerged to enable clients to become skilled in functional performance. In addition to therapeutic exercise and activity and the facilitation and inhibition techniques associated with various sensorimotor approaches to treatment, therapists have added adjunctive therapies to their repertoires, all designed to enhance clients’ performance in purposeful occupation.

Although use of adjunctive therapies such as physical agent modalities is not considered to be an entry-level skill,3,5 some therapists have become increasingly skilled in the application of these therapies. These modalities traditionally were utilized by physical therapists but have long since entered the realm of OT practice. Trained OTs use them to enhance the development of the individual’s ability to perform purposeful occupation, the primary objective of OT. Their use by OTs should be limited to the role of an adjunct to or preparation for purposeful active occupation.

Purposeful Occupation and Activity

One of the first principles of OT, stated by Dunton in 1918, is that some useful end to occupation must exist for it to be effective in the treatment of mental and physical disability.50 This principle implies that occupation has a purpose, and that purposeful activity has an autonomous or inherent goal beyond the motor function required to perform the task.9 An individual engaged in purposeful activity focuses attention on the goal rather than on the processes required to reach the goal.4,6

Conversely, nonpurposeful activity has been defined as activity that has no inherent goal other than the motor function used to perform the activity.50 The person performing a nonpurposeful activity is likely to be focused on the activity process or movements rather than a functional or meaningful goal. Therapeutic exercise and enabling activities such as moving cones and stacking blocks cannot be considered purposeful activity when they have no purpose for the client. This statement does not imply that such media have no place in the continuum of intervention. However, in accord with the OTPF-2, intervention must consider the inherent occupational objectives of the client so both tools of treatment and skills to be acquired are more readily tied to purpose, meaning, and therapeutic value and constitute the occupational nature of therapy.

Purposeful activity is the cornerstone of OT and is its primary intervention modality.50,52 In a position paper on purposeful activity, the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) defined purposeful activity as “goal-directed behaviors or tasks that comprise occupations. An activity is purposeful if the individual is an active, voluntary participant and if the activity is directed toward a goal that the individual considers meaningful.”6 Although some theorists have attempted to distinguish between purposefulness and meaningfulness, others use these terms interchangeably to indicate that the investment of the performer in either purpose or meaning determines its usefulness in therapy. The uniqueness of OT lies in its emphasis on the extensive use of purposeful or meaningful activity. This emphasis gives OT the theoretic foundation for its broad application to psychosocial, physical, and developmental dysfunction, in addition to health maintenance.4

Purposeful activity has inherent and therapeutic goals. For example, sawing wood (Figure 29-2) may have the inherent goal of securing parts for construction of a bookshelf, whereby the therapeutic objectives may be to strengthen shoulder and elbow musculature. The conscious effort of the client is focused on the ultimate outcome of the project and not on the movement itself.9 The client directs and is in control of the movement; however, that control is ordinarily outside of conscious awareness as the client focuses on the goal aspects of performance. In fact, performance outside of conscious awareness distinguishes OT’s therapeutic effectiveness. To enhance skill building, performance must become automatic and decrease reliance on cognitive monitoring.13 Automatic performance serves as a subskill for more advanced performance. For example, Huss suggested that the child who must attend to sitting is unable to focus on the task performance that automatic sitting would ordinarily enable.24 Consequently, the child cannot engage in active occupations essential to growth and the development of social roles. Ayres’ emphasis on the interaction of subcortical regions of the brain as requisite to skilled performance affirms this same principle.8,9

The importance of purposeful activity is readily observed in goal-directed performance. As the client becomes absorbed in the performance of any given activity, affected parts are used more naturally and with less fatigue,49 perhaps attributable to the perception of time that derives from participation in everyday activities.32 Concentration on motion has a detrimental effect on that motion, and muscles controlled by conscious attention and focused effort fatigue rapidly. The value of goal-oriented effort in purposeful tasks is clear. It is of greater therapeutic value to focus attention on an activity of interest to the client and its inherent goal than on the muscles or motions being used to accomplish the activity,9 and that is what goal-directed OT effects.

A number of studies have shown the efficacy of purposeful activity.40 Steinbeck demonstrated that clients who do purposeful activity perform for a longer period than when they are engaging in nonpurposeful activity.50 A study of motivation for product-oriented versus non-product-oriented activity by Thibodeaux and Ludwig indicated the need to determine the client’s level of interest in the process and the product and to incorporate his or her image of the activity in treatment planning.52 Rocker and Nelson found that not being allowed to keep an activity product can elicit hostile feelings in normal subjects,46 which demonstrates the importance of tangible productivity for sustaining people’s interest. Yoder, Nelson, and Smith studied the effects of added-purpose versus rote exercise in female nursing home residents.56 The added-purpose exercise resulted in significantly more movement repetitions than did rote exercise.56 These studies suggest that goal-directed, purposeful activity increases motivation for participation in sustained activity and can therefore be assumed to heighten the willingness of clients to engage in therapeutic activity.

When an intervention plan is being developed, the inherent goals of the activity, the client’s level of interest in the activity, and the meaning of the activity and its product are important considerations in the ultimate effectiveness of the media and methods selected for intervention. Purposeful activities are used, or adapted for use, to meet one or more of the following therapeutic objectives: (1) to develop or maintain strength, endurance, work tolerance, range of motion (ROM), and coordination; (2) to practice and use voluntary, automatic movement in goal-directed tasks; (3) to provide for purposeful use of and general exercise to affected parts; (4) to explore vocational potential or train in work skills; (5) to improve sensation, perception, and cognition; (6) to improve socialization skills and enhance emotional growth and development; and (7) to increase independence in occupational role performance. Some of these objectives alone may not be considered purposeful unless they relate to function. Arts, crafts, games, sports, leisure, self-care, home management, purposive mobility, and work-related activities are considered purposeful activities and may hold occupational significance for the client.

Occupation and Health

OT was founded on the concept that human beings have an occupational nature. That is, it is natural for humans to be engaged in activity, and the process of being occupied contributes to the health and well-being of the organism.9,12,17,25 Activity is valuable for the maintenance of health in the healthy person and for the restoration of health after illness and disability. When the client engages in relevant, meaningful, and purposeful activity, change is possible and dysfunction is reversible.17 The OT acts as facilitator of the change process.16 Therefore, physical dysfunction can be ameliorated when the client participates in goal-directed (purposeful) and thus therapeutic activity.9

The value of purposeful activity lies in the client’s simultaneous mental and physical involvement. Activity provides the exercise needed to help develop the use of affected parts and also provides an opportunity to meet emotional, social, and personal gratification needs.9,49 Cynkin and Robinson pointed out that, for the attainment of optimal function and health, the human being must be consciously involved in problem-solving and creative activity, processes that are linked with the use of the hands.17

Most occupational performance involves the hands or requires the substitution of methods that simulate the use of hands. The use of a computer-driven environmental control unit operated by a sip-and-puff mechanism is an example of an activity ordinarily performed by the hands but, in this case, a substitution for hand control is made using the sip-and-puff mechanism.

The activities that form the pattern of a person’s life, which are performed routinely and automatically, are taken for granted until some dysfunction disrupts their performance. The OT’s role is to adapt activity so that clients can resume their ability to perform life’s tasks. OT is founded on the notion that dysfunction can be modified, altered, or reversed toward function through engagement in the activities of real life. Cynkin and Robinson make several assumptions about activities,17 which are summarized as follows:

• A wide variety of activities are important to the individual. Activities fulfill many of a person’s needs and wants, and they are essential to physical and psychosocial growth and development and the attainment of mastery and competence.

• Activities are socioculturally regulated by the values and beliefs of the culture that defines acceptable behavior for groups of people in the culture. Whether a society is rigid or flexible in its interpretation of acceptable behaviors for various groups, at some point deviations in behavior or activity patterns are deemed unacceptable.

• Activity-related behavior can change from dysfunctional toward more functional. Persons can change and desire change.

• Changes in activity-related behavior take place through motor, cognitive, and social learning.17

Assessment of Occupational Role Performance

The therapist should establish the client’s occupational goals and needs. A top-down, client-centered approach is recommended. Identifying appropriate and meaningful therapeutic activities should begin with obtaining and analyzing the client’s occupational history and interests.52

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure30 and the Activity Configuration16 are two examples of occupational performance assessments. See Chapter 3 for more information about assessment of occupational performance.

Activity Analysis

Careful activity analysis is essential to the selection of appropriate treatment activities. It should yield information about various activities as intervention strategies for physical dysfunction and health maintenance. Activities should be analyzed from three perspectives: the contributions of the person or actor, the effects of the physical environment on performance, and the implications of the social environment. The therapist should recognize that these three elements are inextricable and form the context for intervention. The importance of context in intervention is widely recognized throughout the profession.2,7

A number of theorists have developed comprehensive guides to activity analysis that can serve as useful resources.12,30,53 A guide to activity analysis specifically relevant to practice in physical dysfunction can be found in Appendix 29-1 at the end of this chapter.

Principles of Activity Analysis

Activities selected for therapeutic purposes should be goal directed; have some meaning to the client to meet individual needs in relation to social roles; require the mental or physical participation of the client at the “just right” level of challenge; be designed to prevent or reverse dysfunction; develop skills to enhance performance in life roles; relate to the client’s interests; be adaptable, gradable, and age appropriate; and be selected through the knowledge and professional judgment of the OT in concert with the interests and investment of the client.22 A comprehensive activity analysis includes all aspects of performance that are potentially elicited by specific activities and reveals their potential for therapeutic application. Fareed had expressed an interest in returning to woodworking and selected a project that he could make for his youngest grandchild. This reflects client-centered activity selection. It is not merely activity for no or limited purpose, but the client has selected the activity because it has meaning for him or her.

Therapeutic Approaches

A variety of therapeutic approaches are available to OTs. Although these approaches differ in their emphasis, all are consistent with an occupational approach to intervention. Aspects of activity analysis relevant to various therapeutic approaches are listed next.

Biomechanical Approach

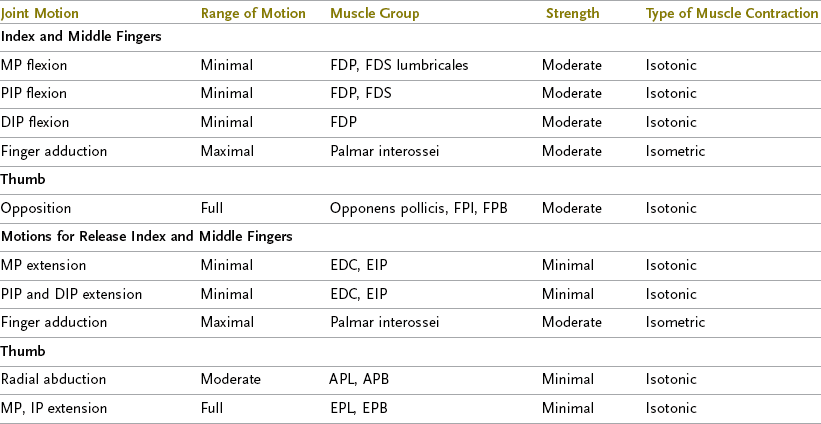

The biomechanical approach to intervention is likely to be used in the treatment of lower motor neuron and orthopedic dysfunctions. Improvements in strength, ROM, and muscle endurance are the goals of OT for such dysfunctions. Thus, the emphasis of activity analysis is on muscles, joints, and motor patterns required to perform the activity. The outcome of OT service is focused on the engagement in the specified activity, but the approach is focused on the biomechanical client factors required to complete the task. Steps of the activity must be identified and broken down into the motions required to perform each step. ROM, degree of muscle strength, and type of muscle contraction to perform each step should be identified. The activity analysis format at the end of this chapter is based on the biomechanical approach.

Sensorimotor Approach

Sensorimotor approaches to intervention are likely to be used for upper motor neuron disorders such as cerebral palsy, stroke, and head injury. Activity analysis for these dysfunctions should focus on the sensory perception of the client and the movement patterns required in the particular treatment approach. The therapist must also consider the effect of the activity on balance, posture, muscle tone, and the facilitation or inhibition of abnormal reflexes and movements. For example, if the therapist is using the proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) approach, it is important to incorporate PNF patterns in the activity or to select activities that use these patterns naturally. For the neurodevelopmental (Bobath) approach, postures and movements that inhibit abnormal reflexes, reactions, and tone are important. These and other sensorimotor approaches and their applications to activity are discussed in Chapter 31.

Analysis of the perceptual and cognitive requirements of the activity is particularly important for clients with upper motor neuron disorders because these functions are often disturbed. The therapist must select activities that meet the requirements for motor performance and can be performed with some success.

Regardless of diagnosis or therapeutic approach, activity analysis should include the contextual aspects of performance. The tangible environment and the social environment dictate occupational performance to the same extent that physical and mental capacities do, and they must be considered in developing an intervention plan.

Adapting and Grading Activity

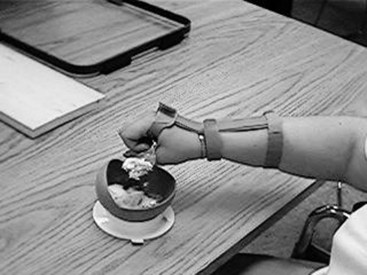

It may be necessary to adapt activities to suit the special needs of the client or the environment. An activity may have to be performed in a special way to accommodate the client’s residual abilities—for example, eating using a special splint with a utensil holder fitted to the hand (Figure 29-3). An activity may have to be adapted to the positioning of the client or to the environment—for instance, by setting up a special reading stand and providing prism glasses to enable a client to read while supine in bed. The problem-solving ability, creativity, and ingenuity of OTs in making adaptations are some of their unique skills.

The therapist should remember that for adaptations to be effective, the client must be able to use them in a comfortable position. The client must understand the need and purpose of the activity and the adaptations and be willing to perform the activity with the simple modifications. Peculiar and complicated adaptations that require frequent adjustment and modification should be avoided.43,49

Grading of Activity

Grading an activity means to pace it appropriately and modify it for the client’s maximal performance. If movement patterns or degree of resistance cannot be attained when the activity is performed in the usual manner, simple modifications may be made. The client usually accepts changes if they are not complex and do not require strained and unnatural motions. The novice is cautioned that the value of the activity may be diminished if it is designed to be performed with artificial movements or excessive resistance. Such methods discourage participation and interfere with the development of coordination.27,49 They also require that the client focus on movements rather than on the goal of the activity, which reduces satisfaction and defeats the primary purpose of purposeful activity as described earlier. The skilled OT adapts and grades activities so that the client easily accepts them and they provide the “just right” demand on performance.

Activities may be graded in many ways to suit the client’s needs and meet the intervention objectives. Activities can be graded for increasing strength, ROM, endurance and tolerance, coordination, and perceptual, cognitive, and social skills. Activities may also be graded according to diminishing capacities of clients, as are expected to occur with such progressive diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Strength

Strength may be graded by an increase or decrease in resistance. Methods include changing the plane of movement from gravity-eliminated to against-gravity, by adding weights to the equipment or to the client, using tools of increasing weights, grading the texture of the materials from soft to hard or fine to rough, or changing to another more or less resistive activity.

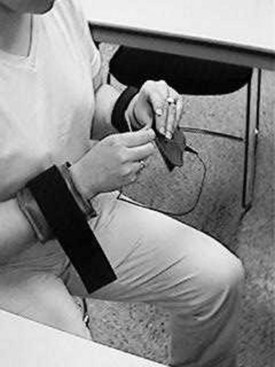

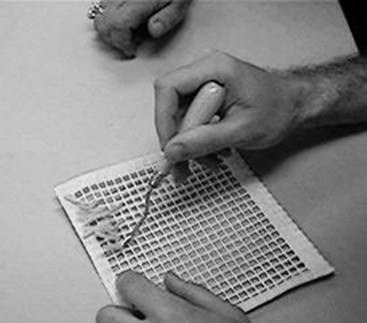

For example, a weight attached to the wrist by a strap increases resistance to arm movements during needle or leatherwork (Figure 29-4). A pulley-and-weight system can be attached to an inclined plane sanding board to increase resistance to the biceps when the sanding block is pulled downward, as the client sands a cutting board for use in one-handed cutting. Springs may be used to increase resistance on a block printing press. When grasp strength is inadequate, grasp mitts may be used to fasten the hand to a tool or equipment handle to assist grip strength and allow arm motion.

Range of Motion

Activities for increasing or maintaining joint ROM may be graded by positioning materials and equipment to demand greater reach or excursion of joints or by adapting equipment with lengthened handles to facilitate active stretching.

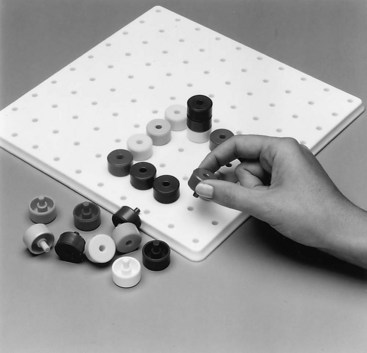

An example of a simple adaptation is positioning a weaving project in a vertical position to achieve the desired range of shoulder flexion while working. As the work progresses, the activity itself establishes increased demands on active range. Positioning objects, such as tiles used in a mosaic tile project, at increasing or decreasing distances from the client changes the range needed to reach the materials (Figure 29-5). Tool handles such as those used in woodworking may be increased in size by using a larger dowel or by padding the handle with foam rubber to accommodate limited ROM or to facilitate grasp (Figure 29-6). Reducing the amount of padding as range or grasp improves can facilitate grading.

Endurance and Tolerance

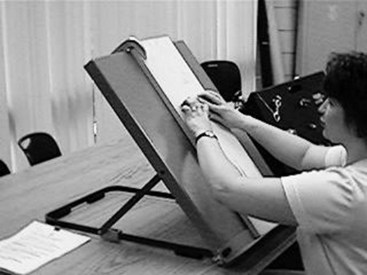

Endurance may be graded by moving from light to heavy work and increasing the duration of the work period. For example, an initial household task of folding paper napkins can be graded to sorting heavier and heavier objects, such as the task of sitting to sort kitchen utensils, and then graded to a standing position to organize tools on a pegboard or to place household items onto shelves. Standing and walking tolerance may be graded by an increase in the time spent standing to work, perhaps at first at a standup table (Figure 29-7), and an increase in the time and distance spent in activities requiring walking, perhaps including home management and workshop activities.

When conditions that are progressively degenerative, such as muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease, require grading endurance in a negative direction to accommodate a diminishing physical condition, it is advisable to change the activity to one that requires less effort rather than reducing the demands of an existing project. The latter can have a negative psychological effect if the client readily recognizes the reduction in performance capacity.

Coordination

Coordination and muscle control may be graded by decreasing the gross resistive movements and increasing the fine controlled movements required. An example is progressing from sawing wood with a crosscut saw to using a coping saw to using a jeweler’s saw. Dexterity and speed of movement may be graded by practicing at increasing speeds once movement patterns have been mastered through coordination training and neuromuscular education.

Perceptual, Cognitive, and Social Skills

In grading cognitive skills, the therapist can begin the treatment program with simple one- or two-step activities that require little judgment, decision making, or problem solving, and progress to activities with several steps that require some judgment or problem-solving processes. A client in a lunch preparation group may butter bread that has already been lined up on the work surface. This task could be graded to lining up the bread, then buttering it and placing a slice of lunchmeat on it, and, ultimately, to making sandwiches.

For grading social interaction, the intervention plan may begin with an activity that demands interaction only with the therapist. The client can progress to activities that require dyadic interaction with another client and, ultimately, to small group activities. The therapist can facilitate the client’s progression from the role of observer to that of participant and then to leader. Concomitantly, the therapist decreases his or her supervision, guidance, and assistance to facilitate more independent functioning in the client.

Selection of Activity

In the treatment of physical dysfunction, activities are usually selected for their potential to improve sensorimotor and psychosocial components to ensure that clients’ motivation to engage in activity is sustained. Activities selected for the improvement of physical performance should provide desired exercise or purposeful use of affected parts. They should enable the client to transfer the motion, strength, and coordination gained in adjunctive and enabling modalities to useful, normal daily activities. If activities are to be used for physical restoration, they should have certain characteristics:

• Activities should provide action rather than merely the position of involved joints and muscles—that is, they should allow alternate contraction and relaxation of the muscles being exercised and allow clients to course through their available ROM.

• Activities should provide repetition of motion—that is, activities should allow for a considerable number of repetitions of movement patterns sufficient to benefit the client.

• Activities should allow for one or more kinds of grading, such as for resistance, range, coordination, endurance, or complexity.22,49

The type of exercise needed must be considered when choosing an activity. Active and resistive exercises are most often used in the performance of purposeful activity.49 Requirements for passive and active-assisted exercise are harder (although not impossible) to apply to purposeful activities—for example, bilateral sanding or using a sponge with both hands to wipe a surface. Other important considerations in the selection of activity are the objects and environment required to perform the activity; safety factors; preparation and completion time; complexity, type of instruction, and supervision required; structure and controls in the activity; learning requirements; independence, decision making, and problem solving required; social interaction potential and communication skills required; and potential gratification to the person.

If an activity is selected in which the client has an interest, the client is more likely to experience sufficient satisfaction to sustain performance. The therapist’s job is to guide the client to suitable therapeutic activities at just the right level of challenge so that the client will achieve satisfaction by engaging in the activity. This satisfaction is an important characteristic of intrinsic motivation. Thus, purposeful activities meet the requirements for motor performance and can be performed with success, which provides positive personal and social feedback. When the OT evaluated Fareed, preferred activities and hobbies were explored. This allowed the OT to select from an array of activities that Fareed had identified and that could be incorporated into the intervention plan.

Simulated or Enabling Activity

The clinical environment may not be fully equipped to meet the exact occupational needs of all clients. When this is the case, it may be necessary to simulate appropriate active occupation by adaptation of the environment or activity to meet the client’s needs and retain his or her interest, called simulated or enabling activity.

OTs have developed a variety of methods to simulate active occupation. A number of these activities were devised initially from equipment and materials used in other activities. A devised activity is the simulated inclined sanding board (Figure 29-8). The sanding board was designed to incline wood while the wood was being sanded.

Therapists began using the board, without the wood, to exercise muscles of the elbow and shoulder. Without the wood, no end product results and thus no inherent purposefulness. However, incorporating wood for a project can turn this from a simulated to a meaningful activity. Our client, Fareed, had indicated that he wanted to pursue a woodworking task. Instead of having Fareed engage in rote exercise using an empty sanding board, his OT placed wood on the sanding board, which Fareed would later use to construct a bench for his grandchild.

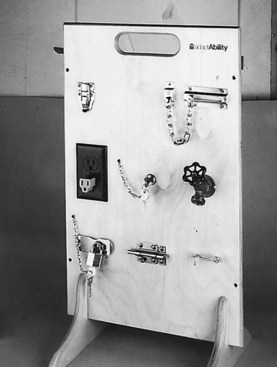

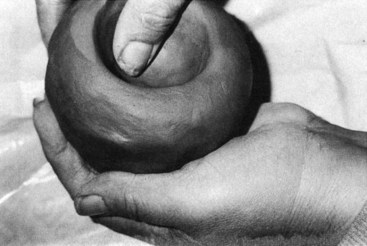

Puzzles and other perceptual and cognitive training media are used to train clients in visual perceptual functions, motor planning skills, memory, sequencing, and problem solving, among other skills (Figure 29-9). Clothing fastener boards and household hardware boards may provide practice in the manipulation of everyday objects before the client is confronted with the real task (Figure 29-10). At a higher level of technological sophistication, commercial work simulators (see Chapter 14) and computer programs are used to improve physical and cognitive client factors.

FIGURE 29-9 Puzzles and other perceptual and cognitive training media are used on the tabletop. (Courtesy North Coast Medical, Morgan Hill, California.)

FIGURE 29-10 Boards built with household fasteners are simulations used for practicing manipulation and management of common household hardware. (Reprinted with permission, S & S Worldwide, adaptAbility, 1995.)

Although many of these items are readily available in clinics, the nature and purpose of OT are best encompassed in an activity in which the client finds purpose and meaning. The therapist should take into consideration the needs and interests of the client in selecting activities, rather than relying on available objects that meet only physical needs.

Enabling activities are considered nonpurposeful and generally do not have an inherent goal, but they may engage the mental and physical participation of the client. The purposes of engaging in enabling activities are to practice specific motor patterns, to train in perceptual and cognitive skills, and to practice sensorimotor skills necessary for function in the home and community. Indeed, many enabling modalities used in OT practice facilitate perceptual, cognitive, and motor learning. Such activities may be appropriate for the skill acquisition stage of learning, when the client is getting the idea of the movement and practicing problem solving. Practice should be daily or frequent and feedback given often so that errors are decreased and skills refined to prepare for performance of real-life purposeful activity. These activities should be used judiciously, and their place in the sequence of the intervention program should be well planned. They may be used along with adjunctive modalities and purposeful activities as part of a comprehensive intervention program.

Adjunctive Modalities

Adjunctive modalities may be used as a preliminary to purposeful activity. When used by the OT, they are meant to prepare the client for occupational performance. Examples of adjunctive modalities are exercise, orthotics, sensory stimulation, and physical agent modalities.41 Therapeutic exercise and physical agent modalities are described next. Many of the principles of therapeutic exercise are readily and customarily incorporated into therapeutic activity and consequently are inherent aspects of OT practice.

Therapeutic Exercise and Activity

The field of OT always has recognized that the mind and body are inextricably united in performance. The psychological and physical effects of purposeful activity were recognized in the treatment of individuals with mental conditions, in addition to in the treatment of persons with physical dysfunction.10,13,20,25 Because it was recognized that physical benefits accrued from the performance of activity, kinesiologic considerations were applied in the selection of appropriate therapeutic activities. To apply kinesiologic considerations to purposeful activity, it was necessary to understand the principles of therapeutic exercise.

As intervention methods evolved, OTs began to use therapeutic exercise alone to prepare clients for purposeful activity and to expedite treatment in a healthcare system constrained by budget and time. The treatment of clients in acute stages of illness and disability imposed new demands and role responsibilities on OTs. Short therapy sessions in acute care settings, the extent of the client’s physical incapacities, and shortened lengths of stay in hospital and rehabilitation facilities caused OTs to expand the range of modalities used in intervention.

The use of therapeutic exercise as an isolated modality raised considerable controversy.21 It was feared that if OTs used exercise or other preparatory modalities, purpose would be forgotten. Exercise and activity tended to be seen by some as mutually exclusive; however, the principles of exercise had been applied to purposeful activity from early in the history of OT. Exercise and activity are complementary in the intervention continuum, and both may be used in a single intervention plan. However, if only pure exercise is used, the client has not received OT.21

When used by OTs, therapeutic exercise should be used to remediate sensory and motor dysfunction, augment purposeful activity, and prepare the client for performing a desired occupation.

A comprehensive understanding of the principles of exercise is basic to the application of therapeutic activity. Therapeutic exercise is defined as any body movement or muscle contraction to prevent or correct a physical impairment, improve musculoskeletal function, and maintain a state of well-being.15,28 A wide variety of exercise options are available; each should be tailored to meet the goals of the intervention plan and the specific capacities and precautions relative to the client’s physical condition.

Exercise can be used to increase ROM and flexibility, strength, coordination, endurance, and cardiovascular fitness.28 Specific exercise protocols may be used to achieve specific goals. However, exercise without activity is apt to place the exercise in the realm of deliberate rather than automatic performance, which therefore violates essential principles of OT discussed earlier. Although judicious application of therapeutic exercise may have a limited place in the therapeutic program, the OT should structure treatment so that the client is engaged in activity primarily to take advantage of the automaticity generated by purposeful goal-directed therapeutic activity.

Purposes

The general purposes of therapeutic exercise, as with therapeutic activity, are as follows:

• To develop awareness of normal movement patterns and improve voluntary, automatic movement responses

• To develop strength and endurance in patterns of movement that are acceptable and necessary and do not produce deformity

• To improve coordination, regardless of strength

• To increase the power of specific isolated muscles or muscle groups

• To aid in overcoming ROM deficits

• To increase the strength of muscles that will power hand splints, mobile arm supports, and other devices

• To increase work tolerance and physical endurance through increased strength

• To prevent or eliminate contractures developing as a result of imbalanced muscle power by strengthening the antagonistic muscles43

Indications for Use

Therapeutic exercise is most effective when providing intervention for orthopedic disorders (such as contractures and arthritis) and lower motor neuron disorders that produce weakness and flaccidity. Examples of the latter are peripheral nerve injuries and diseases, poliomyelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, infectious neuritis, and spinal cord injuries and diseases.

The candidate for therapeutic exercise must be medically able to participate in the exercise regimen, able to understand the directions and purposes, and interested and motivated to perform. The client must have available motor pathways and the potential for recovery or improvement of strength, ROM, coordination, or movement patterns, as applicable. Some sensory feedback must be available to the client—that is, sensation must be at least partially intact so that the client can perceive motion and the position of the exercised part and sense superficial and deep pain. Muscles and tendons must be intact, stable, and free to move. Joints must be able to move through an effective ROM for those types of exercise that use joint motion. The client should be relatively free of pain during motion and should be able to perform isolated, coordinated movement. If the client has any dyskinetic movement, he or she should be able to control it so that the procedure can be performed as prescribed.42 The type of exercise selected depends on muscle grade, muscle endurance, joint mobility, diagnosis and physical condition, treatment goals, position of the client, and desirable plane of movement. Each of these requirements is also applicable to the use of exercise-focused therapeutic activity and should underlie its selection as a therapeutic tool.

Contraindications

Therapeutic exercise and exercise-focused therapeutic activity are contraindicated for clients who have poor general health or inflamed joints or who have had recent surgery.42 They may not be useful where joint ROM is severely limited as the result of well-established, permanent contractures. As defined and described here, they cannot be used effectively for those who have spasticity and lack voluntary control of isolated motion or those who cannot control dyskinetic movement. The latter conditions are likely to occur in upper motor neuron disorders.

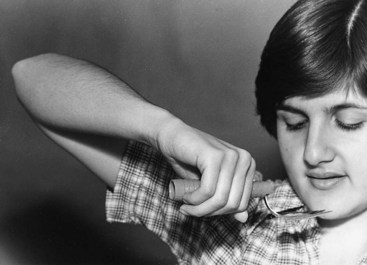

Exercise Programs

Muscle Strengthening: Active-assisted, active, and resistive isotonic exercises and isometric exercises are used to increase strength. After partial or complete denervation of muscle tissue and during inactivity or disuse, muscle strength decreases. When strength is inadequate, substitution patterns or “trick” movements are likely to develop.55 A substitution is the attempt to achieve a functional goal by using muscle groups and patterns of motion not ordinarily used. Substitution is used when muscles normally used to perform the movements or restrictions in ROM are lost or weakened because of structural dysfunction. An example is using shoulder abduction to achieve a hand-to-mouth movement if elbow flexors cannot perform against gravity (Figure 29-11). When muscle loss is permanent, some substitution patterns may be desirable as a compensatory measure to improve performance of functional activities, such as the use of tenodesis to permit grasp that will enable self-feeding. Many substitute movements are not desirable, however, and it is often the aim of therapeutic exercise to prevent or correct substitution patterns.55

A muscle must contract at or near its maximal capacity and for enough repetitions and time to increase strength. Strengthening programs generally are based on having the muscle contract against a large resistance for a few repetitions. Strengthening exercises are not effective if the contraction is insufficient.15,29 Excessive repetitions of strengthening exercises, however, may result in muscle fatigue, pain, and temporary reduction of strength. If a muscle is overworked, it becomes fatigued and is unable to contract. The type of exercise must suit the muscle grade and the client’s fatigue tolerance level. Fatigue level varies from individual to individual, and the threshold for muscle fatigue decreases in pathologic states.29 Many clients may not be sensitive to fatigue or may push themselves beyond tolerance in the belief that this approach hastens recovery. Therefore, the therapist must carefully assess the client’s muscle power and capacity for performance. The therapist must also supervise the client closely and observe for signs of fatigue. These signs may be slowed performance, distraction, perspiration, increase in rate of respiration, performance of exercise pattern through a decreased ROM, and inability to complete the prescribed number of repetitions.

Increasing Muscle Endurance: Endurance is the ability of the muscle to work for prolonged periods and resist fatigue. Although a high-load, low-repetition regimen is effective for muscle strengthening, a low-load and high-repetition exercise program is more effective for building endurance.15,18 Having determined the client’s maximum capacity for a strengthening program, the therapist can reduce the maximum resistance load and increase the number of repetitions to build endurance in specific muscles or muscle groups. The strength versus endurance training may be seen as a continuum. Resistance and the number of repetitions can be modulated so that gains in strength and endurance accrue.15

Physical Conditioning and Cardiovascular Fitness: Improving general physical endurance and cardiovascular fitness requires the use of large muscle groups in sustained, rhythmic aerobic exercise, or activity. Examples are swimming, walking, bicycling, jogging, and some games and sports. This type of activity is often used in cardiac rehabilitation programs in which the parameters of the client’s physical capacities and tolerance for exercise should be well defined and medically supervised. To improve cardiovascular fitness, exercise should be done 3 to 5 days per week at 60% to 90% of maximum heart rate or 50% to 85% of maximum oxygen uptake. Between 15 and 60 minutes of exercise or rhythmic activities using large muscle groups is desirable.15

Range of Motion and Joint Flexibility: Active and passive ROM activities are used to maintain joint motion and flexibility. Active exercise is performed solely by the individual. An outside force such as the therapist or a device can be used for performing passive ROM exercise. The continuous passive motion machine, a device that can be preset to provide continuous passive motion throughout the joint range, is an example. Application of any mechanical device requires caution and careful monitoring to prevent mishaps and possible deleterious effects.15

Stretching or forced exercise may be necessary to increase ROM. Some type of force is applied to the body part when soft tissue (muscles, tendons, and ligaments) is at or near its available length. The use of a low-resistance stretch of sustained duration is preferred to high resistance and repetitive, quick, bouncing movements. The former method is less likely to produce tissue tearing, trauma, and activation of stretch reflexes in hypertonic muscles. The use of thermal agents or neuromuscular facilitation techniques may enhance static stretching.15

Coordination and Neuromuscular Control: Coordination is the combined activity of many muscles into smooth patterns and sequences of motion. Coordination is an automatic response monitored primarily through proprioceptive sensory feedback. Kottke defined control as “the conscious activation of an individual muscle or the conscious initiation of a pre-programmed engram.”27 Control involves conscious attention to and guidance of an activity.

A preprogrammed pattern of muscular activity represented in the central nervous system (CNS) has been described as an engram. An engram is formed only if many repetitions of a specific motion or activity occur. With repetition, conscious effort of the client is decreased and the motion becomes more and more automatic. Ultimately the motion can be carried out with little conscious attention. It has been hypothesized that when an engram is excited, the same pattern of movement is produced automatically. Neuromuscular education or control training involves teaching the client to control individual muscles or motions through conscious attention. Coordination training is used to develop preprogrammed multimuscular patterns or engrams.27

Types of Muscle Contraction

Isometric or Static Contraction: During an isometric contraction, no joint motion occurs and the muscle length remains the same. The limb is set or held taut as agonist and antagonist muscles are contracted at a point in the ROM to stabilize a joint. This action may be without resistance or against some outside resistance, such as the therapist’s hand or a fixed object. An example of isometric exercise of the triceps against resistance is pressing down against a tabletop with the ulnar border of the forearm while the elbow remains at 90-degree flexion. An example of an activity that requires isometric contraction is stabilizing the arm in a locked position when carrying a shopping bag slung over the forearm.23,29

Isotonic or Concentric Contraction: During an isotonic contraction, the joint moves and the muscle shortens. This contraction may be done with or without resistance. Isotonic contractions may be performed in positions with gravity decreased or against gravity, according to the client’s muscle grade and the goal of the exercise or activity. An isotonic contraction of the biceps is used to lift a fork to the mouth for eating.23,29

Eccentric Contraction: When muscles contract eccentrically, the tension in the muscle increases or remains constant, while the muscle lengthens. This contraction may be performed with or without resistance. An example of an eccentric contraction performed without resistance is the lowering of the arm to the table when placing a napkin next to a plate. The biceps contracts eccentrically in this instance. An example of eccentric contraction against resistance is the controlled return of a pail of sand-lifted from the ground. In this example the biceps is contracting eccentrically to control the rate and coordination of the elbow extension in setting the pail on the ground.23,29

Exercise and Activity Classifications

Isotonic Resistive Exercise: Resistive exercise uses isotonic muscle contraction against a specific amount of weight to move the load through a certain ROM.15,23,29 It is also possible to use eccentric contraction against resistance. Resistive exercise is used primarily for an increase in the strength of fair plus to normal muscles but may also be helpful for producing relaxation of the antagonists to the contracting muscles. This latter purpose can be useful if increased range is desired for stretching or relaxing hypertonic antagonists.

The client performs muscle contraction against resistance and moves the part through the available ROM. The resistance applied should be the maximum against which the muscle is capable of contracting. Resistance may be applied manually or by weights, springs, elastic bands, sandbags, or special devices. The source of resistance depends on the activity, and resistance is graded progressively with an increasing amount of resistance.15,23,29 The number of possible repetitions depends on the client’s general physical endurance and the endurance of the specific muscle.

Many types of strength training programs exist; most are based on the principle that to increase strength, the muscle must contract against its maximal resistance. The number of repetitions, rest intervals, frequency of training, and speed of movement vary with the particular approach and with the client’s ability to accommodate to the exercise or activity regimen.10 One specialized type of resistive exercise is the DeLorme method of progressive resistive exercise (PRE).18,48 PRE is based on the overload principle: muscles perform more efficiently if given a warm-up period and must be taxed beyond usual daily activity to improve in performance and strength.18 During the exercise procedure, small loads are used initially and increased gradually after each set of 10 repetitions. The muscle is thus warmed up to prepare to exert its maximal power for the final 10 repetitions. The exercise procedure consists of three sets of 10 repetitions each, with resistance applied as follows: first set, 10 repetitions at 50% of maximal resistance; second set, 10 repetitions at 75% of maximal resistance; third set, 10 repetitions at maximal resistance.15,18,48 The load must be sufficient so that the client can perform 10 repetitions. As strength improves, resistance is increased so that 10 repetitions can always be performed.10 The client is instructed to inhale during the shortening contraction and exhale during the relaxation or eccentric contraction.18,48

An example of a PRE is a triceps, capable of 12 pounds maximal resistance, extending the elbow, first against 6 pounds for 10 repetitions, then against 9 pounds for 10 repetitions, and the final 10 repetitions against 12 pounds. Maximal resistance, the amount of resistance the muscle can lift through the ROM 10 times, is determined by contracting the muscle and moving the part through the full ROM against progressively increasing loads for sets of 10 repetitions, until the maximal load that can be lifted 10 times is reached.

At the beginning of the treatment program it is often difficult for the therapist to determine the client’s maximal resistance. Reasons may be that the client may not know how to exert maximal effort, may be reluctant to exercise strenuously for fear of pain or reinjury, may be unwilling or unable to endure discomfort, and may have difficulty with the timing of exercises.

The experience of the therapist and trial and error aid in the determination of maximal resistance. The therapist should estimate the amount of resistance the client can take based on the muscle test results and add or subtract resistance (weight or tension) until the client can perform the sets of repetitions adequately.

The exercises should be performed once daily, four or five times a week, and rest periods of 2 to 4 minutes should be allowed between each set of 10 repetitions. The exercise procedure may be modified to suit individual needs. Some possibilities are 10 repetitions at 25% of maximal resistance, 10 repetitions at 50%, 10 repetitions at 75%, and 10 repetitions at maximal resistance. Another possibility is five repetitions at 50% and 10 repetitions at maximal resistance. Still another possibility is to omit the second set of exercises. Adjustments in the first two sets of exercises may be made to suit the capacity of the individual.18

Another approach is the Oxford technique, essentially a reverse of the DeLorme method. The exercise sequence begins with 100% resistance and decreases to 75%, and then to 50% on subsequent sets of 10 repetitions each.18,48 The greatest gains may be made in the early weeks of the intervention program, with smaller increases occurring at a slower pace in the subsequent weeks or months. During performance of the exercise, the therapist should be aware of joint alignment of the exercise device; proper fit and adjustment of the device; ruling out of substitute movements; and clear instruction on speed, ROM, and proper breathing.18,43

Isotonic Active Exercise: Isotonic muscle contraction is used in active exercise. Eccentric contraction may also be used. Active exercise is performed when the client moves the joint through its available ROM against no outside resistance. Active motion through the complete ROM with gravity decreased or against gravity may be used for poor to fair muscles to improve strength, with the added benefit of maintaining ROM. It may be used with higher muscle grades for the maintenance of strength and ROM when resistance is contraindicated. Active exercise is not used to increase ROM because this purpose requires added force not present in active exercise.

In active exercise, the client moves the part through the complete ROM independently. If the exercise is performed in a gravity-reduced or gravity-decreased plane, a powdered surface, skateboard may be used to reduce the resistance produced by friction on a supporting surface. A deltoid aid, or free-moving suspension sling may be used to support the extremity when moving in a gravity-decreased plane of motion. The exercise is graded by a change to resistive exercise as strength improves.23,29

Active-Assisted Exercise: Isotonic muscle contraction is used in active-assisted exercise. The client moves the joint through partial ROM, and the therapist or a mechanical device completes the range. Slings, pulleys, weights, springs, or elastic bands may be used to provide mechanical assistance.48 The goal of active-assisted exercise is to increase strength of trace, poor minus, and fair minus muscles while maintaining ROM. In the case of trace muscles, the client may contract the muscle, and the therapist completes the entire ROM. This exercise is graded by decreasing the amount of assistance until the client can perform active exercises.23,29

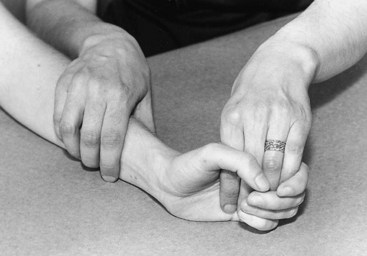

Passive Exercise: In passive exercise, no muscle contraction occurs. Therefore, passive exercise is not used to increase strength because no force is applied. The purpose of passive exercise is to maintain ROM, thereby preventing contractures, adhesions, and deformity. To achieve this goal, the person should perform exercise for at least three repetitions, twice daily.28 It is used when absent or minimal muscle strength (grades 0 to 1) precludes the active motion or when active exercise is contraindicated because of the client’s physical condition. During the exercise procedure, the joint or joints to be exercised are moved through their normal ranges manually by the therapist or client, or mechanically by an external device such as a pulley or counterbalance sling. The joint proximal to the joint being exercised should be stabilized during the exercise procedure (Figure 29-13).23

Passive Stretch: For passive stretching, the therapist moves the joint through the available ROM and holds momentarily, applying a gentle but firm force or stretch at the end of the ROM. No residual pain should occur when the stretching is discontinued. Passive stretch or forced exercise is meant to increase ROM. It is used when a loss of joint ROM occurs and stretching is not contraindicated. If muscle grades are adequate, the client can move the part actively through the available ROM and the therapist can take it a little farther, thus forcing or stretching the soft-tissue structures around the joint.

Passive stretching requires a good understanding of joint anatomy and muscle function. It should be carried out cautiously under good medical supervision and with medical approval. Muscles to be stretched should be in a relaxed state.29 The therapist should never force muscles when pain is present, unless ordered by the physician to work through pain. Gentle, firm stretching held for a few seconds is more effective and less hazardous than quick, short stretching. The body parts around the area being stretched should be stabilized, and compensatory movements should be prevented. Incorrect stretching procedures can produce muscle tearing, joint fracture, and inflammatory edema.28

Active Stretch: The purpose of active stretch is the same as for passive stretch: to increase joint ROM. In active stretching, the client uses the force of the agonist muscle to increase the length of the antagonist. This requires good to normal strength of the antagonist, good coordination, and motivation of the client. For example, forceful contraction of the triceps to stretch the biceps muscle can be performed. Because the exercise may produce discomfort, a natural tendency exists for the client to avoid the stretching component of the movement. Therefore, supervision and frequent evaluation of its effectiveness are necessary.

Isometric Exercise without Resistance: Isometric exercise uses isometric contractions of a specific muscle or muscle group. In isometric exercises, a muscle or group of muscles is actively contracted and relaxed without producing motion of the joint that it ordinarily moves. The purpose of isometric exercise without resistance is to maintain muscle strength when active motion is not possible or is contraindicated. It may be used with any muscle grade above trace. It is especially useful for clients in casts, after surgery, and with arthritis or burns.15

The client is taught to set or contract the muscles voluntarily and to hold the contraction for 5 or 6 seconds. Without offering resistance, the therapist’s fingers provide a kinesthetic image of resistance and help the client learn to set the muscle. If needed, the therapist’s fingers may be placed distal to the joint on which the muscles act. If passive motion is allowed, the therapist may move the joint to the desired point in the ROM and ask the client to hold the position.

Isometric exercise affects the cardiovascular system, which may be a contraindication for some clients. It may cause a rapid and sudden increase in blood pressure, depending on the client’s age, the intensity of contraction, and the muscle mass being contracted. Therefore, it should be used with caution.15

Isometric Exercise with Resistance: Isometric exercise with applied resistance uses isometric muscle contraction performed against some outside resistance. Its purpose is to increase muscle strength in muscles graded fair, or 3, to normal, or 5. The client sets the muscle or muscle group while resistance is applied and holds the contraction for 5 or 6 seconds. Isometric exercises should be performed for one exercise session per day, 5 days a week. In addition to manual resistance, the client may hold a weight or resist against a solid surface, depending on the muscle group being exercised. A small weight held in the hand while the wrist is stabilized at neutral requires isometric contractions of the wrist flexors and extensors.

Exercise is graded by increasing the amount of resistance or the degree of force the client holds against. A tension gauge should be used to accurately monitor the amount of resistance applied. Isometric exercises are effective for increasing strength, but isotonic exercise is the method of choice. Isometric exercise has several specific applications, as in arthritis, when joint motion may be contraindicated but muscle strength must be increased or maintained.23,43 The cardiovascular precautions stated previously are particularly important with isometric resistive exercise.

Neuromuscular Control and Coordination: Procedures for the development of neuromuscular control and neuromuscular coordination are briefly outlined in the following paragraphs. The reader is referred to original sources for a full discussion of the neurophysiologic mechanisms underlying these exercises. Neuromuscular education or control training involves teaching the client to control individual muscles or motions through conscious attention. Coordination training is used to develop preprogrammed multimuscular patterns or engrams.27

Neuromuscular Control: It may be desirable to teach control of individual muscles when they are so weak that they cannot be used normally. The purpose is to improve muscle strength and muscle coordination to new patterns. To achieve these ends, the person must learn precise control of the muscle, an essential step in the development of optimal coordination for persons with neuromuscular disease.

To participate successfully, the client must be able to learn and follow instructions, cooperate, and concentrate on the muscular retraining. Before beginning, the client should be comfortable and securely supported. The exercises should be carried out in a nondistracting environment. The client must be alert, calm, and rested. He or she should have an adequate pain-free arc of motion of the joint on which the muscle acts, in addition to good proprioception. Visual and tactile sensory feedback may be used to compensate or substitute for limited proprioception, but the coordination achieved will never be as efficient as when proprioception is intact.27

The client is first made aware of the desired motion and the muscles that produce it when the therapist uses passive motion to stimulate the proprioceptive stretch reflex. This passive movement may be repeated several times. The client’s awareness may be enhanced if the therapist also demonstrates the desired movement and if the movement is performed by the analogous unaffected part. The skin over the muscle belly and tendon insertion may be stimulated to enhance the effect of the stretch reflex. Stroking and tapping over the muscle belly may be used to facilitate muscle action.27

The therapist should explain the location and function of the muscle, its origin and insertion, line of pull, and action on the joint. The therapist should then demonstrate the motion and instruct the client to think of the pull of the muscle from insertion to origin. The skin over muscle insertion can be stroked in the direction of pull while the client concentrates on the sensation of the motion during the passive movement performed by the therapist.

The exercise sequence begins with instructions to the client to think about the motion, while the therapist carries it out passively and strokes the skin over the insertion in the direction of the motion. The client is then instructed to assist by contracting the muscle while the therapist performs passive motion and stimulates the skin as before. Next the client moves the part through ROM with assistance and cutaneous stimulation, while the therapist emphasizes contraction of the prime mover only. Finally the client carries out the movement independently, using the prime mover.

The exercises must be initiated against minimal resistance if activity is to be isolated to prime movers. If the muscle is very weak (trace to poor), the procedure may be carried out entirely in an active-assisted manner so that the muscle contracts against no resistance and can function without activating synergists. Progression from one step to the next depends on successful performance of the steps without substitutions. Each step is carried out three to five times per session for each muscle, depending on the client’s tolerance.

Coordination Training: The goal of coordination training is to develop the ability to perform multimuscular motor patterns that are faster, more precise, and stronger than those performed when control of individual muscles is used. The development of coordination depends on repetition. Initially in training, the movement must be simple and slow so that the client can be consciously aware of the activity and its components. Good coordination does not develop until repeated practice results in a well-developed activity pattern that no longer requires conscious effort and attention.

Training should take place in an environment in which the client can concentrate. The exercise is divided into components that the client can perform correctly. Kottke calls this approach desynthesis.27 The level of effort required should be kept low, by reducing speed and resistance, to prevent the spread of excitation to muscles that are not part of the desired movement pattern. Other theorists offer contrary advice, which emphasizes the integration of movements that customarily occurs during activity. The therapist’s experience and judgment are important in determining which method to use.

When the motor pattern is divided into units that the client can perform successfully, each unit is trained by practice under voluntary control, as described previously for training of control. The therapist instructs the client in the desired movement and uses sensory stimulation and passive movement. The client must observe and voluntarily modify the motion. Slow practice is imperative to make this monitoring possible. The therapist offers enough assistance to ensure precise movement while allowing the client to concentrate on the sensations produced by the movements. When the client concentrates on movement, fatigue occurs rapidly and the client should be given frequent, short rests. As the client masters the components of the pattern and performs them precisely and independently, the sequence is graded to subtasks or several components that are practiced repetitively. As the subtasks are perfected, they are linked progressively until the movement pattern can be performed.

The protocol can be graded for speed, force, or complexity, but the therapist must be aware that the increased effort put forth by the client may result in incoordinated movement. Therefore, the grading must remain within the client’s capacity to perform the precise movement pattern. The motor pattern must be performed correctly to prevent the development of faulty patterns.

If CNS impulses are generated to muscles that should not be involved in the movement pattern, incoordinated motion results. Constant repetition of an incoordinated pattern reinforces the pattern, resulting in a persistent incoordination. Factors that increase incoordination are fear, poor balance, too much resistance, pain, fatigue, strong emotions, prolonged inactivity,27 and excessively prolonged activity.

Physical Agent Modalities

The introduction of physical agent modalities (PAMs) into OT practice generated considerable controversy.51,54 The use of such modalities was initiated by OTs who specialize in hand rehabilitation, in which inclusion of physical agents in a comprehensive treatment program became expedient.45,47 After much study and discussion, the AOTA published a position paper on physical agent modalities.3,5 In this official document, physical agents were defined and their use as adjuncts to or preparation for purposeful activity was specified. “The exclusive use of physical agent modalities as a treatment method during a treatment session without application to a functional outcome is not considered occupational therapy.”5 Further, the use of PAMs is not considered entry-level practice: rather, appropriate postprofessional education is required to ensure competence of the OT practitioners using these modalities.5 The AOTA stipulated that the practitioner must have documented evidence of the theoretic background and technical skills to apply the modality and integrate it into an OT intervention plan.3,5 Generated from these notions, a number of states have required in their licensure laws that OTs have advanced training to use PAMs in treatment.

PAMs are used before or during functional activities to enhance the effects of the OT intervention program. This section introduces the reader to basic techniques and when and why they may be applied. Because OTs most commonly use modalities for treatment of hand injuries and diseases, the examples provided are focused on intervention to improve upper extremity function. The use of the techniques described is not limited to the treatment of hands, however.

Thermal Modalities

In a clinical setting, heat is used to increase motion, decrease joint stiffness, relieve muscle spasms, increase blood flow, decrease pain, and aid in the reabsorption of exudates and edema in a chronic condition.33 Collagen fibers have an elastic component and when stretched will return to their original length. Applying heat before a prolonged stretch, as in dynamic splinting, allows the permanent elongation of these fibers. The blood flow maintains a person’s core temperature at 98.6° F. To obtain maximum benefits from heat, tissue temperature must be raised to 105° to 113° F. Precautions must be taken with temperatures above this range to prevent tissue destruction.

Contraindications to the use of heat include acute inflammatory conditions of the joints or skin, sensory losses, impaired vascular structures, malignancies, and application to the very young or very old. The use of heat may substantially enhance the effects of splinting and therapeutic activities that attempt to increase range of motion and functional abilities.

Conduction: Conduction is the transfer of heat from one object to another through direct contact. Paraffin and hot packs provide heat by conduction. Paraffin is stored in a tub that maintains a temperature between 125° and 130° F. The client repeatedly dips his or her hand into the tub until a thick, insulating layer of paraffin is applied to the extremity. The hand is then wrapped in a plastic bag and towel for 10 to 20 minutes.33 This technique provides an excellent conforming characteristic, so it is ideal for use in hands and digits. Partial hand coverage is possible. The paraffin transfers its heat to the hand, and the bag and towel act as an insulator against dissipation of heat to the air.