Application of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework to Physical Dysfunction

Section 1: The Occupational Therapy Process

The occupational therapy process

Clinical reasoning in the intervention process

Theories, models of practice, and frames of reference

Teamwork within the occupational therapy profession

Teamwork with other professionals

Section 2: Practice Settings for Physical Disabilities

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Identify and describe the major functions of the occupational therapy (OT) process.

2 Describe how clinical reasoning adjusts to consider various factors that may be present in the intervention context.

3 Identify how theories, models of practice, and frames of reference can inform and support OT intervention.

4 Identify appropriate delegation of responsibility among the various levels of OT practitioners.

5 Discuss ways in which OT practitioners may effectively collaborate with members of other professions involved in client care.

6 Recognize ethical dilemmas that may occur frequently in OT practice, and identify ways in which these may be addressed and managed.

7 Describe the various practice settings for OT practice in the arena of physical disabilities.

8 Discuss the type of services typically provided in these settings.

9 Identify ways in which different practice settings affect the occupational performance of persons receiving occupational therapy services.

10 Identify the environmental attributes that afford the most realistic projections of how the client will perform in the absence of the therapist.

11 Identify environmental and temporal aspects of at least three practice settings.

12 Describe ways in which the therapist can alter environmental and temporal features to obtain more accurate measures of performance.

This chapter is divided into two sections. The first section introduces the occupational therapy (OT) process, summarizing the function of evaluation, intervention, and outcomes described in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, Second Edition (OTPF-2).5 The chapter will acquaint the reader with the complexity and creativity of clinical reasoning within the context of the contemporary clinical environment. The complementary roles of different occupational therapy practitioners, as well as relationships between OT and the other professional disciplines involved in the care of the client with physical dysfunction, are described. Common ethical dilemmas are introduced and ways to analyze these are presented.

The second section describes various practice settings where occupational therapy services are provided for individuals who have physical disabilities with a discussion of typical services in each setting.

Section 1 The Occupational Therapy Process

WINIFRED SCHULTZ-KROHN, HEIDI MCHUGH PENDLETON

The Occupational Therapy Process

The OTPF-2 discusses both the domain and the process of the profession.5,83 The domain is described in Chapter 1, and the reader should be familiar with the domain prior to reading about the process of occupational therapy.

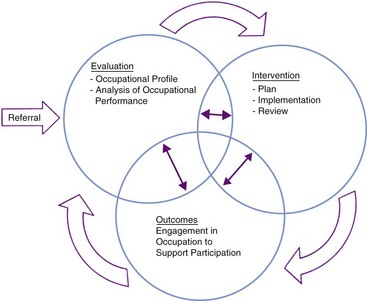

The occupational therapy process should be conceptualized as a circular process initiated by a referral (Figure 3-1). Following the referral, an evaluation is conducted to identify the client’s occupational needs. The intervention is developed based on the evaluation results. The targeted outcome of intervention is supporting the client’s “health and participation in life through engagement in occupation” (p. 648).5 The steps of evaluation, intervention, and outcome should not be viewed in a linear fashion but instead should be seen as a circular or spiraling process where the parts are mutually influential.

Referral

The physician or other legally qualified professional requests occupational therapy services for the client. The referral may be oral, but a written record is often a necessity. Guidelines for referral vary, and in some situations occupational therapy services may require a physician’s referral. The occupational therapist (OT) is responsible for responding to the referral. Although clients may seek occupational therapy services without first obtaining a referral, the occupational therapist may need a referral prior to the initiation of intervention services. State regulatory boards and licensing requirements should be reviewed prior to initiation of services to determine if a referral for service is necessary.

Screening

The OT determines whether further evaluation is warranted and if occupational therapy services would be helpful to this client. The therapist may perform a screening independently or as a member of the healthcare team. Screening procedures are generally brief and do not cover all areas of occupation. A formal screen is not always conducted with the client but, during the review of the client’s record prior to the evaluation, the OT considers the diagnosis, physical condition, referral, and information from other professionals. The therapist then synthesizes this information prior to initiating an evaluation. In some settings, the screening process flows directly into the evaluation of the client in a seamless manner.

Evaluation

Evaluation refers to “the process of obtaining and interpreting data necessary for intervention. This includes planning for and documenting the evaluation process and results.”1 Assessment refers “to specific tools or instruments that are used during the evaluation process.”1 Two parts of the evaluation process have been identified: the generation of an occupational profile and the analysis of occupational performance. The assessments chosen help in developing the occupational profile. The OT then analyzes the client’s occupational performance through synthesis of data collected using a variety of means.

The evaluation portion begins with the OT and client developing an occupational profile that reviews the client’s occupational history and describes the client’s current needs and priorities.5,12 This portion of the evaluation process includes the client’s previous roles and the contexts for occupational performance. For example, Sheena has been assigned to develop an occupational profile for a 56-year-old man who recently had a tumor removed from his right cerebral hemisphere, resulting in dense left hemiplegia. He has been married to his wife for 27 years and reports that he never cooks. On further exploration during the development of the occupational profile, the man reports that one of his most treasured occupations is being able to grill and discusses the importance of grilling over charcoal versus using a gas grill. Although Sheena may have initially ignored the need to work on cooking skills with this man, she now understands the occupational significance of grilling and, from the client’s perspective, the difference between grilling and cooking! The occupational profile allows the OT to understand the client’s occupational history, current needs, and priorities, and identifies which occupations or activities are successfully completed and those that are problematic for the client.

The occupational profile is most often initiated with an interview with the client, and significant others in the client’s life, and by a thorough review of available records.5 Interviews may be completed using a formal instrument or informal tools. Although the occupational profile is used to focus subsequent intervention, this profile is often revised throughout the course of intervention to meet a client’s needs. The purpose of the occupational profile is to answer the following questions as articulated in the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) document:5

1. Who is the client? This requires consideration of not only the individual but the significant others in the client’s life. In some settings the client may be identified as a group and not as an individual. For example, a 28-year-old woman, Nora, who sustained a traumatic brain injury resulting in memory deficits and slight difficulties with coordination, is a wife and a mother to two young children. During the evaluation process, Sheena considers not only Nora’s occupational needs but also the needs of her family and her roles as a family member.

2. Why is the client seeking service? This relates to the occupational needs identified by the individual and significant others. The needs of not only Nora but those of her husband and children should be included in answering this question.

3. What occupations and activities are successful or are problematic for the client? This would also include understanding which occupations are successfully completed by the client. Nora may have the physical ability to drive and yet has severe memory problems and difficulties remembering the route to drive her children to school and various activities.

4. How do contexts and environments influence engagement in occupations and desired outcomes? Some contexts may be supportive, whereas others present challenges or prohibit occupational performance. Nora’s parents expect her to be the primary caregiver for her children and when her husband attempts to support Nora, her parents interfere.

5. What is the client’s occupational history? This includes the level of engagement in various occupations and activities along with the value attributed to those occupations by the client. Although prior to her traumatic brain injury Nora was responsible for the majority of the housecleaning tasks, Nora did not highly value these duties. She was also responsible for meal preparation and reports that she enjoys cooking. She places a much higher value on being able to drive her children to school and various after-school activities.

6. What are the client’s priorities and targeted outcomes? These may be identified as occupational performance, role competence, adaptation to the circumstance, health and wellness, prevention, or quality-of-life issues. For Nora, the need to safely drive and resume responsibility for fostering community participation for her children was a primary outcome. This reflects her interest in occupational performance. She was not interested in having her parents or her husband assume these roles.

After the occupational profile is developed, the OT identifies the necessary additional information to be collected, including areas to be evaluated and what assessment instruments should be used prior to the analysis of occupational performance. The OT may delegate some parts of the evaluation, such as the administration of selected assessment tools, to the occupational therapy assistant (OTA). The interpretation of data is the responsibility of the OT. This requires the OT to direct the evaluation by completing an occupational profile, interpreting the data collected from the profile, and then analyzing the client’s occupational performance prior to proceeding to assessment of client factors. The selection of additional information beyond the occupational profile should answer the following questions:

1. What additional data are needed to understand the client’s occupational needs including contextual supports and challenges?

2. What is the best (most efficient and accurate) way to collect these data?

The ability of the client to successfully plan, initiate, and complete various occupations is then evaluated. The occupations chosen are based on the occupational profile. The OT then analyzes the data to determine the client’s specific strengths and weaknesses that impact occupational performance. The impact of contextual factors on occupational performance is included in the analysis of data. This can easily be seen when a client who is dependent on a wheelchair for all mobility is faced with several stairs to enter an office building to conduct business. The client has functional mobility skills but is prohibited from participating because of an environmental factor that restricts access. The analysis includes integrating data regarding the activity demands, the client’s previous and current occupational patterns, and the client factors that support or prohibit occupational performance. Data about specific client factors may be helpful in developing an intervention plan but should be performed after the occupational profile is completed and an analysis of occupational performance has been initiated. The information generated from the profile and analysis will allow more careful selection of necessary assessment tools to collect further data. The OT also considers if the client would benefit from a referral to other professionals.

Now consider the case presentation from the beginning of the chapter. Although Sheena is able to competently perform a manual muscle test and range-of-motion assessment, these assessments would not be necessary for all clients. Sheena must first develop the client’s occupational profile as a guide to then select the most appropriate assessment instruments to complete her evaluation of the client’s occupational performance. After she has completed these steps, Sheena is able to more clearly identify what additional information is needed to plan and implement intervention services.

Intervention Planning

Working with the client, the occupational therapy practitioners (OT and OTA) develop a plan using the following approaches or strategies to enhance the client’s ability to participate in occupational performance.5,12 Although the OT is responsible for the plan, the OTA contributes to the plan and must be “knowledgeable about the evaluation results” (p. 665).3 The strategies selected should be linked to the intended outcomes of service.5 These approaches or strategies answer the question, “What type (approach/strategy) of intervention will be provided to meet the client’s goals?” Examples of each form of intervention approach or strategy are provided with selected literature to support this form of occupational therapy intervention:

1. Prevention of disability. This approach is focused on developing the performance skills and patterns that support continued occupational performance and provides intervention that anticipates potential hazards or challenges to occupational performance. Contextual issues are also addressed using this approach and environmental barriers would be similarly considered. An example of services representing a preventative approach would be instructing a client who has compromised standing balance in fall prevention techniques and asking the family to remove loose throw rugs from the home to avoid falls.24 Clark et al.21 demonstrated the beneficial effects of preventative occupational therapy services in the investigation of well, elderly adults. Adults who received preventative occupational therapy displayed far fewer health and functional problems when compared to adults who did not receive these services.

2. Health promotion. A disabling condition is not assumed, but instead occupational therapy services are provided to enhance and enrich occupational pursuits. This approach may be used to help clients who are transitioning in roles or used to foster occupational performance across contexts. An example would be using narratives to promote a healthy transition from the role of a worker to retirement.42 As workers described what they anticipated in retirement, they linked “past, present, and future” (p. 49). This process of anticipating changes and making choices was considered to be an important factor in “understanding how people adapt to life changes” (p. 49).

3. Establish or restore a skill or ability. This strategy is aimed at improving a client’s skills or abilities, thus allowing greater participation in occupations. Evidence of the effectiveness of occupational therapy services provides this form of intervention as demonstrated by several investigators. Walker et al.80 investigated the effectiveness of occupational therapy services in restoring activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) skills in clients who had sustained a cerebrovascular accident (CVA) but had not received inpatient rehabilitation services. They used a randomized controlled trial and demonstrated that clients receiving occupational therapy services had significantly better ADL and IADL performance when compared to clients who had not received these services. Rogers et al.69 also demonstrated that performance of ADLs can be significantly improved when provided with systematic training.

4. Adapt or compensate. This approach is focused on modifying the environment, the activity demands, or the client’s performance patterns to support health and participation in occupations. Instruction and use of energy conservation techniques for clients who have dyspnea (shortness of breath or difficulty breathing) as a result of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is an example of this approach.55 The use of electronic aids to daily living (EADL) is another example of how the activity can be modified to promote participation.29 When clients who had acquired brain damage were provided with training in the use of EADL, they reported a sense of mastery. Even if a client’s previous abilities cannot be restored, employing this adaptive or compensatory approach can promote participation in occupations.

5. Maintain current functional abilities. This approach recognizes that many clients are faced with degenerative disorders, and occupational therapy services should actively address the need to maintain occupational engagement.19,31 Intervention may focus on the activity demands, performance patterns, or context for occupational performance. As an example, an individual in the early stage of Parkinson’s disease is still able to complete many self-care activities but should develop the habits that will maintain these skills as motor function continues to deteriorate. Maintenance also includes clients who have a chronic, nonprogressive disorder; in this situation there is a need for maintaining physical conditioning to meet activity and environmental demands.

Through collaboration with the client and significant others, the intervention plan identifies not only the specific focus of the goal but also the explicit content of the goal. For example, Nora, who sustained a traumatic brain injury, indicated that she wanted to be able to return to driving her children to various community-based activities. Services would focus on two approaches: restoring the skills needed to engage in this occupation of driving her children to community activities and adapting the performance by avoiding community activities that necessitate driving during heavy traffic periods in the morning and late afternoon.

Specific driving skills would be improved using strategies to enhance reaction time, problem solving, and attention to potential safety risks. Because of Nora’s diminished memory and difficulties with processing complex information, the occupation of driving her children to community activities should be modified. Nora could select community activities that are close to her children’s school and home, thereby decreasing the length of time she is driving her children. Through the use of a programmable guidance system in her car, such as a global positioning system (GPS), she is able to follow the specific directions to the various community activities. If these intervention approaches are unsuccessful, the OT may explore alternatives to driving with Nora, such as bicycling or walking with her children to nearby community activities or carpooling with another parent where the other parent assumes the actual driving role and Nora contributes by providing snacks or gas money. Such alternatives could provide a safer solution and still meet the need for Nora to be involved in the occupation of driving or transporting her children to their community activities.

The OT is responsible for the plan and for any parts delegated to the OTA. The plan includes client-centered goals and methods for reaching them using the above-mentioned approaches or strategies. The values and goals of the client are primary; those of the therapist are secondary.5 Cultural, social, and environmental factors are incorporated into the plan. The plan must identify the scope and frequency of the intervention and the anticipated date of completion. The outcomes of the intervention must be written at the time the intervention plan is developed. Discharge planning is initiated during the intervention planning process. This is accomplished by developing clear outcomes and targeted time frames for the completion of goals.

The generation of clear and measurable goals is a very important step in the planning process. Long-term goals or terminal behaviors must reflect a change in occupational performance. For a client to receive authentic occupational therapy services, there must be a focus on “supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupation” (p. 626).5 This may be achieved through several means, including improved occupational performance, role competence, adaptation, prevention, or quality of life. To meet this outcome, short-term goals or behavioral objectives reflect the incremental steps that must occur to reach this target. An example would be Nora returning to driving. Several short-term steps would be necessary prior to meeting this terminal behavior or long-term goal. An intervention plan may address bilateral coordination and speed of reaction prior to having Nora return to driving. Several authors have provided detailed descriptions of the critical parts of a well-written goal.43 Table 3-1 serves as a brief guide for the development of goals and objectives. (For additional details regarding goals and documentation, see Chapter 8.)

TABLE 3-1

| A. Actor | Begin the goal with a statement such as “Nora will …” Name the client as the performer of the action for the goal. |

| B. Behavior | The occupation, activity, task, or skill to be performed by the client. If this is an outcome or terminal goal, the behavior must reflect occupational performance. Short-term goals or behavioral objectives are often steps to reaching a long-term goal or outcome. A short-term goal or objective may identify a client factor or performance skill as the targeted behavior. An outcome behavior for Nora would be the ability to drive a car, whereas a short-term behavior would be to enter the car and fasten a seatbelt. |

| C. Condition | The situations for the performance of the stated behavior include social and physical environmental situations for the behavior. Examples of conditions included in a goal are the equipment used, social setting, and training necessary for the stated behavior. In the situation of Nora, driving a car with an automatic transmission is a far different condition than driving a car with a manual transmission. |

| D. Degree | The measure applied to the behavior and the criteria for how well the behavior is performed. These may include repetitions, duration, or the amount of the activity completed. A client may only be expected to complete a small portion of an activity as a short-term goal, but the long-term goal would address the targeted occupation. The amount of support provided serves as a measure of degree of behavioral performance. This would include whether the client required minimal assistance, verbal prompts, or performed the task independently. The criteria must be appropriate for the behavior. Safely driving 50% of the time is an inappropriate criterion, but using a percentage to indicate that Nora will independently fasten her seat belt 100% of the time provides an appropriate criterion for the behavior |

| E: Expected time frame | When is the goal to be met, the time period that is anticipated to meet the goal as stated. |

Adapted from Kettenbach G: Writing SOAP notes, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2004, FA Davis.

Intervention Implementation

The intervention plan is implemented by the OT practitioners. The OT may assign to the OTA specific responsibilities in delivery of the intervention plan. Nonetheless, the OT retains the responsibility to direct, monitor, and supervise the intervention and must ensure that relevant and necessary interventions are provided in an appropriate and safe manner and that documentation is accurate and complete.3 The method used to provide interventions could include therapeutic use of self, therapeutic use of occupations and activities, consultation, education, or advocacy.5 (See Chapter 1 for a more detailed description of these methods of providing intervention.) These methods answer the question, “How will intervention strategies be provided?” The intervention plan would identify which approach or strategy would be used in combination with the method of intervention. During the actual implementation of intervention services, a clinician may seamlessly shift between different methods, depending on the needs of the client.

Implementation of services should also include helping the client anticipate needs and solutions. A method developed by Schultz-Krohn74 provides a structure to this process and was labeled anticipatory problem solving. This process was developed from client-centered models such as the model of human occupation44 and the person-environment-occupation48,49 model described later in this chapter. This process was designed to empower the client to anticipate potential challenges and develop solutions prior to encountering the challenges. The key elements of the anticipatory problem-solving process are as follows:

1. The client and clinician identify the occupation or activity to be performed.

2. The specific features of the environment that are required for occupational/activity performance are identified. This includes contextual and environmental factors in addition to the necessary equipment to engage in the occupation/activity.

3. The OT and client identify potential safety risks or challenges to engagement in the occupation/activity that are located in the environment or with the objects required.

4. The OT and client develop a solution for these risks or challenges.

An example would be Nora, who would like to be able to drive her children to after-school activities. As she regains her abilities to drive, anticipatory problem-solving strategies are employed to prepare her for potential environmental challenges. The process follows these steps:

1. Nora and the OT identified the occupation of driving her children to after-school music lessons as the focus for intervention.

2. The car has an automatic transmission. The route typically used to drive her children from school to the lessons includes a busy street with four lanes, but no highway driving is required. She does need to make one left-hand turn on this street, but there is a left turn light. The travel time typically takes 10 minutes.

3. Nora reports that traveling on the one busy street can be a challenge because many drivers exceed the speed limit on this road and drive erratically. This is the quickest route to the music lessons and because she is very familiar with the route, it provides less challenge to her memory. Nora’s husband also reports that this road often has construction, presenting an additional challenge.

4. Instead of changing the route, Nora develops a solution whereby she allocates an additional 5 minutes to transport her children to lessons, allowing her to feel less pressure when drivers are exceeding the speed limit. Strategies to address the erratic drivers encountered on this road included frequent checks of her side mirrors and moving to the left lane two intersections before the left-hand turn light. An alternate route is also mapped out for Nora to use when road construction presents a challenge.

This process provides a brief illustration of how anticipatory problem-solving methods can be used during the intervention implementation. This process can be equally applied to bathing, where a client anticipates the potential hazard of a slippery surface and makes appropriate plans before bathing. The foundation of this process is to engage the client in developing solutions for everyday challenges encountered as he or she engages in occupations/activities. The client is actively involved in identifying not only the occupation/activity but also potential challenges or risks encountered and generating solutions for the identified challenges or risks.

Included in the intervention implementation process is the ongoing monitoring of the client’s response to the services provided. As services are initiated, the OT monitors the client’s progression on a continuous basis and modifies the intervention methods used as needed to support the client’s health and participation in life.

Intervention Review

The occupational therapy practitioners evaluate the intervention plan on a regular basis to determine if the client’s goals are being met.5 The OT is “responsible for determining the need for continuing, modifying, or discontinuing occupational therapy services” (p. 665), but the OTA contributes to this process.3 The review may include a reevaluation of the client’s status to determine what changes have occurred since the previous evaluation. This measurement of the outcomes of intervention is critical in showing the effectiveness of the intervention. The intervention plan may be changed, continued, or discontinued, based on the results of the reevaluation. This reevaluation also offers an opportunity to determine if the intervention provided is focused on the outcomes articulated in the plan.

Outcomes

Working in collaboration with the client, the client’s family, and the intervention team, the OT and OTA identify the intended outcome of the intervention. Although the OTPF-2 clearly states that the outcome of occupational therapy services is focused on “supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupation”5 (p. 660), this outcome can be measured in several ways. Outcomes may be written to reflect a client’s improved occupational performance; a change in the client’s response to an occupational challenge; effective role performance; habits and routines that foster health, wellness, or the prevention or lessening of further disability; and client satisfaction in the services provided. Client satisfaction can also include overall quality of life outcomes that often incorporate several of the previously mentioned outcomes.

Although the overarching outcome of occupational therapy intervention is “supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupation” (p. 626), this goal can be achieved through several types of outcomes.5 The decision of whether the selected outcomes are successfully met is made collaboratively with the members of the intervention team including the client. The outcomes may require periodic revisions because of changes in the client’s status. When the client has reached the established goals or achieved the maximum benefit from occupational therapy services, the OT formally discontinues service and creates a discontinuation plan that documents follow-up recommendations and arrangements. Final documentation includes a record of any change in the client’s status from first evaluation through the end of services.

Figure 3-1 shows the relationship between the various parts of the intervention process. This process is not completed in a linear fashion but instead requires constant monitoring, and each section informs the other parts of the process. The outcome generated during the planning step should direct an OT to select intervention methods best suited to reach the desired client goals. During the intervention process, it may become apparent that the desired outcome is not realistic, necessitating revision of the client’s goals and outcome of services.

Clinical Reasoning in the Intervention Process

Since 1986, the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) has funded a series of investigations to examine how occupational therapists think and reason in their work with clients.35 Clinical reasoning can be defined informally as the process used by OT practitioners to understand the client’s occupational needs, make decisions about intervention services, and as a means to think about what we do. There are several forms of clinical reasoning, and authors do not consistently use the same term for specific forms of clinical reasoning. Fleming33 identified three “tracks” of clinical reasoning used by the expert clinician to organize and process data: procedural, interactive, and conditional. Yet another dimension of clinical reasoning, identified as narrative reasoning, has been discussed in the literature by Mattingly.53 The fifth form of clinical reasoning, pragmatic reasoning, describes the practical issues and contextual factors that must be addressed.57,72 This section will describe how the five basic forms of clinical reasoning, discussed in current literature, can be applied to practice.

Procedural reasoning is concerned with getting things done, with what “has to happen next.” This reasoning process is closely related to the medical form of problem solving. The emphasis is often placed on client factors and body functions and structures when this form of reasoning is employed. A connection between the problems identified and the interventions provided is sought using this form of reasoning and can be seen in critical pathways developed in some hospitals. A critical pathway is a form of a decision-making tree based on a series of yes/no questions that can direct client intervention. For example, a client who had a total hip replacement would receive intervention that follows a predicted or anticipated trajectory of recovery. Critical pathways are often developed to support best practice when there is substantial information about a client’s course of recovery from a surgical procedure or medical treatment. Procedural reasoning would be used to develop critical pathways and is driven by the client’s diagnosis and potential outcomes anticipated for individuals with this diagnosis. This form of clinical reasoning is influenced by using current evidence about the client’s condition and selected intervention.51 An OT should review literature on an ongoing basis to provide effective and appropriate intervention services.54 Using this knowledge to develop and implement intervention reflects procedural reasoning in practice.

Interactive reasoning is concerned with the interchanges between the client and therapist. The therapist uses this form of reasoning to engage with, to understand, and to motivate the client. Understanding the disability from the client’s point of view is fundamental to this type of reasoning. This form of reasoning is used during the evaluation to detect the important information provided by the client and to further explore the client’s occupational needs. During intervention, this form of reasoning is used to assess the effectiveness of the intervention selected in meeting the client’s goals. The therapeutic use of self fits well with this form of clinical reasoning as a therapist employs personal skills and attributes to engage the client in the intervention process.

Conditional reasoning is concerned with the contexts in which interventions occur, the contexts in which the client performs occupations, and the ways in which various factors might affect the outcomes and direction of therapy. Using a “what if?” or conditional approach, the therapist imagines possible scenarios for the client. The therapist engages in conditional reasoning to integrate the client’s current status with the hoped-for future. Intervention is often revised on a moment-to-moment basis to proceed to an outcome that will allow the client to participate in various contexts. Although an intervention is designed and implemented to foster occupational pursuits, conditional reasoning is not singularly focused on reaching the outcome. Conditional reasoning recognizes that the process of intervention often necessitates a reappraisal of outcomes. This reappraisal should be encouraged to help the client refine goals and outcomes.

Narrative reasoning uses story making or storytelling as a way to understand the client’s experience. The client’s explanation or description of life and the disability experience reveal themes that permeate the client’s understanding and that will affect the enactment and outcomes of therapeutic intervention. In this sense, narrative reasoning is phenomenological. Therapists also use narrative reasoning to plan the intervention session, to create a story line of what will happen for the client as a result of therapy. Here the therapist draws on both interactive and conditional reasoning using the client’s words and metaphors to project possible futures for the client. The therapeutic use of self is critical when employing this form of clinical reasoning. Providing an opportunity for the client to share the meaning of the disability experience helps with formulating plans and projecting future occupational performance. This is where the context and occupational performance intersects. A person may be able to engage in an activity with modifications, but those modifications may be unacceptable within the client’s cultural and social context. For example, an individual who, prior to a stroke, was an avid motorcyclist is now unable to control the clutch and hand controls necessary to safely drive a motorcycle and also has impaired balance. Although automatic motorcycles are now available with three wheels, this client refuses the option, considering this to be not part of the motorcycle culture.

Pragmatic reasoning extends beyond the interaction of the client and therapist. This form of reasoning integrates several variables including the demands of the intervention setting, the therapist’s competence, the client’s social and financial resources, and the client’s potential discharge environment. Pragmatic reasoning recognizes the constraints faced by the practicing therapist by forces beyond the client-therapist relationship. For example, a hospital that provides inpatient services may not have the resources for a therapist to make a home visit prior to a client being discharged. A therapist working solely through a home health agency will not have full access to clinic equipment when working in the client’s home. These challenges to providing intervention would be considered when developing an intervention plan using pragmatic reasoning.

Experienced master clinicians engage in all forms of reasoning to develop and modify their plans and actions during all phases of the occupational therapy process. Some of the questions a therapist might consider related to each form of clinical reasoning are listed in Box 3-1.

Clinical Reasoning in Context

Pressures for cost containment and reduction of unnecessary services require therapists to balance the needs of the client and the practical realities of healthcare reimbursement and documentation. Thus, on first meeting the client, the therapist will want to know the anticipated or required date of discharge, as well as the scope of services that will be reimbursed and those that are likely to be denied. Simultaneously, the therapist is formulating an occupational profile with the client, evaluating the client’s occupational performance, engaging the client in identifying outcomes and goals, and determining which interventions would best meet the desired outcomes. The OT also considers the contextual factors that will influence occupational performance. Further, the therapist is alert to requirements for documentation and the particular current procedural terminology (CPT) codes that may apply. The OT must document service accurately and effectively so that reimbursement will not be challenged and the client’s needs may be adequately addressed. (For a more detailed discussion of documentation, see Chapter 8.)

From first meeting the client, the therapist is guided by the client’s goals and preferences. Client-centered service delivery requires client (or family) involvement and collaboration at all stages of the intervention process.5 To effectively engage the client and the family demands, cultural sensitivity and an ability to communicate with people of diverse backgrounds is required.17,76,79,81 In some cultures, the idea of participating equally in decision making with a health professional may be unknown. Being asked by a therapist to make decisions may feel quite unfamiliar and uncomfortable to the client. Thus, the therapist must support the client’s ability to collaborate, adjust to the client’s point of view, and find other ways to ensure that the intervention plan, including intended outcomes, is acceptable to the client and significant others in the client’s life. Understanding the influence of culture on the client’s occupational performance and performance patterns is fundamental to the provision of services.17 The OT should pose the following questions to foster cultural competence in the provision of services:

1. What do I know about the client’s culture and beliefs about health? This represents the basic knowledge of cultural health practices and beliefs. Conclusions or judgments should not be formed about why these practices are present.

2. Does the client agree with these beliefs? Although a client may affiliate with a specific cultural group, the OT must investigate to determine if the cultural beliefs of health and the client’s beliefs of health are similar.

3. How will these beliefs influence the intervention and outcomes of services provided? The OT must acknowledge and respond to the influences of cultural beliefs and practices within the intervention plan. To design a plan that conflicts with cultural beliefs would not only be counterproductive to client-centered services but would be disrespectful of the client’s belief system. If a client, in deference to the authority of the OT, follows an intervention that conflicts with cultural practices, the client may risk receiving support and affiliation with that cultural group.

4. How can the intervention plan support culturally endorsed occupations, roles, and responsibilities to promote the client’s engagement in occupation? The OT must consider the important occupations from a cultural perspective. Evening meals may include specific behaviors that possess strong cultural symbols for one client, but another client may view an evening meal as merely taking in food with no prescribed rituals.

Client-Centered Practice

Involving clients in identifying their own goals and in making decisions about their own care and intervention is highly valued by leaders in the OT profession32,63,73 and is endorsed by the AOTA in its policy and practice guidelines.7 Client-centered practice begins when the therapist first meets the client. Therapists using an occupation-based assessment tool, such as the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM),47 initiate assessment by asking clients to identify and choose goals early in the evaluation process. This process can be fostered when the therapist is aware of potential biases that could influence the development of goals.71 Regardless of disability status or perceived limitations in cognitive functioning, every client should be invited to participate in evaluation and intervention decisions. Client-centered practice is guided by the following concepts:9

• The language used reflects the client as a person first and the condition second.

• The client is offered choices and is supported in directing the occupational therapy process. This requires the occupational therapist to provide information about the client’s condition and the evidence available regarding the various types of intervention.

• Intervention is provided in a flexible and accessible manner to meet the client’s needs.

• Intervention is contextually appropriate and relevant.

• There is clear respect for differences and diversity in the occupational therapy process.

Although client-centered practice is most often conceptualized as the OT practitioner working with a person and those significant in that person’s life, the OTPF-2 describes “clients” as persons, organizations, and/or populations. When providing OT services to organizations or populations, the OT practitioner is still expected to apply the same values of client-centered practice and enlist the client, whether an organization or population, in identifying goals and selecting outcomes.

Theories, Models of Practice, and Frames of Reference

The profession of occupational therapy acknowledges the need for theories, models of practice, and frames of reference to advance the profession, demonstrate evidence-based intervention, and more clearly view occupation.44 Theories, models of practice, and frames of reference offer the clinician a means to understand and interpret information to develop an effective intervention plan. These terms require definition and understanding prior to application to practice.

Theory

This term refers to the process of understanding phenomena including articulating concepts that describe and define phenomena and the relationships between observed events across situations or settings. A theory is tested across settings for confirmation of concepts and relationships. Although a theory may be generated from one profession, it is often applied across professions when the theory is an accepted method of understanding phenomena. According to Reed,66 theory attempts to do the following:

• Define and explain relationships between concepts or ideas related to the phenomenon of interest (for example, occupational performance and occupation).

• Explain how these relationships can predict behavior or events.

• Suggest ways that the phenomenon can be changed or controlled.”

A clear example of a theory that meets these expectations and is well known is germ theory.15 Widely accepted and tested, germ theory states that microorganisms produce infections. Prior to understanding the relationship between these microorganisms and infections, physicians would perform an autopsy and then go to an adjacent room to deliver a baby without washing hands between the two events. The number and severity of infections occurring after childbirth dramatically decreased when germ theory was accepted and then functionally applied to practice (a frame of reference) through the use of proper hand-washing procedures. From an occupational therapy perspective, theories provide the profession with a means to examine occupation and occupational performance and understand the relationship between engagement in occupations and participation in context.44 The main purpose of a theory is to understand the specific phenomenon. Mary Reilly’s theory of occupational behavior was designed to explain the importance of occupation and the relationship between occupation and health.67,68 Her theory served as a foundation for several models of practice within the profession of occupational therapy.

Model of Practice

Model of practice refers the application of theory to occupational therapy practice. This process is achieved through several means such as the development of specific assessments and articulation of principles to guide intervention. Models of practice are not intervention protocols but instead serve as a means to view occupation through the lens of theory with the focus on the client’s occupational performance. Models of practice often serve as a mechanism to engage in further testing of the theory.44 Some authors refer to models of practice as conceptual models,18 whereas other authors include models of practice in the discussion of professional theories.23 In the profession of occupational therapy, several models of practice exist, but the commonality seen in each is the focus on occupation. The main purpose of a model of practice is to facilitate the analysis of the occupational profile and consider potential outcomes with selected interventions. Models should be applicable across settings and client groups instead of designed primarily for a specific diagnostic group. From a very colloquial expression, a model of practice is where the clinician “puts on the OT eyeglasses” to bring into focus the client’s needs and abilities, various contextual issues, and engagement in occupation. Three of these models of practice will be briefly described. The reader is encouraged to seek additional information from the materials used in this brief description.

Model of Human Occupation: In the model of human occupation (MOHO),44 the engagement in occupation is understood as the product of three interrelated subsystems that cannot be reduced to a linear process. These three subsystems are linked to produce occupational performance. The volitional subsystem refers to the client’s values, interests, and personal causation. A client may clearly identify values and interests to a clinician but then express a sense of incompetence to engage in a desired occupation. Volition is the client’s thoughts and feelings, including occupational choices. The habituation subsystem refers to the habits and roles that are often critical to a sense of self. Colloquial phrases such as “I don’t feel like myself” expressed by a client often speak of a distortion of habit or role experienced in life. A client, faced with a disabling condition, often experiences a severe disruption in roles and habits. The sense of self can deteriorate when roles such as driving to work, driving to go shopping, or driving friends to enjoy a picnic are eliminated because of a disabling condition. The performance capacity subsystem reflects the client’s lived experience of the body. This is not the strength or range of motion available but refers to the client’s previous experience, changes, and expectations of performance capacity. Again, using the a colloquial phrase “once you’ve ridden a bicycle, you never forget” captures a portion of this concept and requires the therapist to consider the client’s experience of successes or failures in using the body to engage in occupations.

Ecology of Human Performance: Ecology of human performance (EHP)27 was not designed to be used exclusively within the profession of occupational therapy but was intended to serve as a mechanism for understanding human performance across professions. An important concept expressed in the EHP is the interaction of the person, the task (activity demands), and the context. Occupational performance is intertwined with, and the product of, the interaction of these three variables. EHP is a client-centered model in which each person is viewed as unique and complex and includes past experiences, skills, needs, and attributes. The task is understood as the objective and observable behaviors to accomplish a goal. The context includes the person’s age, life cycle, and health status from a perspective of the cultural and societal meanings of each. Context also addresses the physical, social, and cultural factors that influence performance. EHP recognizes that these three factors influence each other and that the person and task are inextricably linked with the context. Performance is the product of the person engaged in a task within a context. A significant contribution of this model is the equal importance placed on each variable in producing occupational performance. Instead of focusing only on improving skills in the person, intervention using this model can assume several forms. Five intervention strategies are described, and a close similarity to the OTPF-2 can be seen. The five strategies include the following:28

1. Establish/restore. Although focused on improving the person’s abilities and skills, the intervention includes the context for performance.

2. Alter. Intervention is designed to alter the contextual factors to foster occupational performance; an example would be home modifications to allow wheelchair access.

3. Adapt/modify. The task or context is adapted or modified to support performance such as use of a reacher to obtain objects or using elastic shoelaces to eliminate the need to tie shoes.

4. Prevent. Intervention may address the person, the context, or the task to prevent potential problems from occurring; examples would be teaching the client back-safety techniques to prevent back injuries, removing rugs in an environment to reduce the risk of falls as a contextual prevention method, and turning down the water temperature for a client with sensory problems to reduce the risk of burns when bathing.

5. Create. Intervention addresses all three variables of the person, task, and context and is designed to develop or create opportunities for occupational performance.

Person-Environment-Occupation Model: The person-environment-occupation model (PEO)48,49 shares characteristics with EHP where occupational performance is seen at the intersection of the person, environment, and occupation. It is a client-centered approach, but equal emphasis is placed on the environment and the occupation when designing intervention. PEO defines the person as a dynamic and changing being with skills and abilities to meet roles over the course of time. The environment includes the physical, social, cultural, and institutional factors that influence occupational performance. Occupations include self-care and productive and leisure pursuits. PEO further differentiates the progression from an activity, a small portion of a task, a task that is a clear step toward an occupation, and the occupation itself, which often evolves over time. An example would be the activity of safely handling a knife. This is a small portion of the task of making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, and the task of making a sandwich is seen as a part of the occupation of meal preparation. Occupational performance is the result of the person, environment, and occupation interacting in a dynamic manner.

Frame of Reference

The purpose of a frame of reference (FOR) is to help the clinician link theory to intervention strategies and to apply clinical reasoning to the chosen intervention methods.45,56 A FOR tends to have a more narrow view of how to approach occupational performance when compared to models of practice. The intervention strategies described within various FORs are not meant to be used as a protocol but offer the practitioner a way to structure intervention and think about intervention progressions. The clinician must always engage in the various forms of clinical reasoning to question the efficacy of the intervention in meeting the client’s goals and outcomes.

A frame of reference should be well fitted to meet the client’s goals and hoped-for outcomes. The colloquial concept of “one size fits all” definitely does not apply to the use of a FOR to guide intervention. That is why there is a need for multiple FORs to meet varied client goals and outcomes. A clinician may blend intervention strategies from several FORs to effectively meet the client’s needs. As an example, a client may be able to recover precise coordination and control of both arms following a traumatic brain injury (TBI) if the OT practitioner combines a biomechanical and a sensorimotor FOR, but the client may have persistent memory deficits requiring the use strategies following a rehabilitative FOR. The following brief descriptions are not meant to be an exhaustive review of all possible FORs that can be used in occupational therapy. Examples are provided to illustrate how a FOR can be used to guide the intervention process.

Biomechanical: The understanding of kinematics and kinesiology serves as the foundation for the biomechanical FOR.75 The clinician views the limitations in occupational performance from a biomechanical perspective, analyzing the movement required to engage in the occupation. Based on principles of physics, the force, leverage, and torque required to perform a task or activity are assessed. These also serve as the basis for intervention. A client may be unable to open a jar of peanut butter or jelly because of limitations in grip strength or the available range of motion required of the hands to hold the jar. A biomechanical approach would focus intervention on addressing these basic client factors to improve occupational performance. Although intervention may take the form of exercises, splinting, or other orthopedic approaches, the outcome must reflect engagement in occupation.41

Rehabilitation: The rehabilitation FOR focuses on the client’s ability to return to the fullest physical, mental, social, vocational, and economic functioning as is possible. The emphasis is placed on the client’s abilities and using the current abilities coupled with technology or equipment to accomplish occupational performance. Compensatory intervention strategies are often employed, and examples include teaching one-handed dressing techniques to an individual who, following a CVA, no longer has functional use of one hand. The focus of intervention is often engagement in occupation through alternative means. (For additional examples of intervention strategies supported by the rehabilitation FOR, see Chapters 10, 11, and 17.) Returning to the same example of making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, instead of having the client work on strengthening the hands to finally open the jar, the clinician would suggest using a device to stabilize the jar and use a gripper to help accomplish the task with current abilities. Regardless of the technology or equipment available, the clinician must always link the intervention to the client’s occupational performance.

Sensorimotor: Several FORs are included in this grouping, such as proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) and neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT) (see Chapter 31 for additional information). These approaches share a common foundation of viewing a client who has sustained a central nervous system insult to the upper motor neurons as having poorly regulated control of the lower motor neurons. To recapture the control of the lower motor neurons, various techniques are employed to promote reorganization of the sensory and motor cortices of the brain. The specific techniques vary but the basic premise is that when the client receives systematic sensory information, his or her brain will reorganize and the return of motor function will be obtained.

Meeting the Client’s Needs

The OT relies on theories, models of practice, and FORs to interpret and integrate evaluation data to meet the client’s identified outcomes. These are used in conjunction with clinical reasoning to develop an intervention plan and critically review the successfulness of the plan. For example, the OT would use procedural reasoning to select a theory, model, or FOR that has proven successful with clients who have a similar diagnosis. Interactive reasoning is used to assess if the chosen model or FOR is meeting the client’s needs. As a therapist applies theories, models, or FORs to meet the client’s needs, a series of professional questions should be posed:

1. Does the theory, model of practice, or frame of reference help with understanding and interpreting the evaluation data while considering the client’s expressed needs?

2. Does the theory, model of practice, or frame of reference provide a good fit for the type of intervention that will meet the client’s needs?

3. What evidence is available that the theory, model of practice, or frame of reference can efficiently produce the results requested by the client?

The preceding questions should be posed throughout the intervention process as a review of the effectiveness of services provided. Although the OT is responsible for interpreting and integrating evaluation data, collaborating with the client to develop the intervention plan, and engaging in ongoing review of the effectiveness of intervention, the OTA contributes to the evaluation and intervention process.

Teamwork within the Occupational Therapy Profession

The OT profession recognizes and certifies two levels of practitioners, the OT and the OTA. The AOTA has provided many documents to guide practice and to clarify the relationship between the two levels of practitioner.3,7 The OT operates as an autonomous practitioner with the ability to provide occupational therapy services independently, whereas the OTA “must receive supervision from an occupational therapist to deliver occupational therapy services” (p. 663).3 Even though OTs are considered able to independently provide occupational therapy services, they should seek supervision and mentoring to foster professional growth. The OT who is managing a case or providing services to clients should use the following as a guide:

• Services are to be provided by personnel who have demonstrated service competency. Some states require advanced training and proficiency in specified arenas of practice. For example, an advanced certification in dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and physical agent modalities is required in the state of California for an OT to provide those services.

• In the interests of rendering the best care at the least cost, the OT may delegate tasks to OTAs and, in some specific instances, to aides or other personnel, provided these providers have the competencies to render such services. This requires the OT to establish the level of competence required and assess the ability of the OTA, aides, or other personnel to perform those duties.

• The OT retains final responsibility for all aspects of care, including documentation.

OT-OTA Relationships

To work effectively with OTAs, the OT must understand the role of the practitioner trained at the technical level.3 It is common for OTs to alternately overestimate and underestimate the capabilities of OTAs. In overestimating the training and abilities of OTAs, OTs might assume that the OTA is trained to provide services identical to those of the OT but perhaps at a lesser pace and level and with a smaller caseload. In underestimating the OTA, the OT might assume that the OTA is capable of performing only concrete and repetitive tasks under the strictest supervision.

The appropriate role of the OTA is complementary to that of the OT. Employed effectively, the OTA can provide occupational therapy services under supervision that ranges from close to general. AOTA has identified critical factors to consider in the delegation of delivery of occupational therapy services.3 These factors include the severity and complexity of the client’s condition and needs, the competency of the OT practitioner, the type of intervention selected to meet the identified outcomes, and the requirements of the practice setting. Working together with several OTAs, the OT will be able to manage a larger caseload and will have the option of introducing more advanced and specialized services, as the role of the OTAs is often to provide routine services. Many variations in the use of OTAs exist across settings. Some services the supervising OT may delegate to the service-competent OTA include the following:

1. Administering selected screening instruments or assessments such as range of motion (ROM) tests, interviews and questionnaires, ADL evaluations, and other assessments that follow a defined protocol.7

2. Collaborating with the OT and client to develop portions of the intervention plan (e.g., planning for dressing training and planning for kitchen safety training).7

3. Implementing interventions supervised by the OT in the areas of ADL, work, leisure, and play. With appropriate training and supervision, the OTA can implement interventions related to other areas of occupational performance.7 As determined by the OT, an OTA can also implement interventions where competence has been demonstrated. An example would be intervention related to the client factors of strength or range of motion.

4. As assigned by the OT, assisting with the transition to the next service setting by, for example, making arrangements with or educating family members or contacting community providers to address the client needs.

5. Contributing to documentation, record keeping, resource management, quality assurance, selection and procurement of supplies and equipment, and other aspects of service management.

6. Under the supervision of the OT, educating the client, family, or community about OT services.

Occupational Therapy Aides

The OT may also extend the reach of services by employing aides.6 AOTA guidelines stipulate that the occupational therapy aide works only under direction and close supervision of an OT practitioner (OT or OTA) and provides supportive services: “Aides do not provide skilled occupational therapy services” (p. 666).3 Aides may perform only specific, selected, delegated tasks. Although the OTA may direct and supervise the aide, the OT is ultimately responsible for the actions of the aide. Tasks that might be delegated to an aide include transporting clients, setting up equipment, preparing supplies, and performing simple and routine client services for which the aide has been trained. Individual jurisdictions and healthcare regulatory bodies may restrict aides from providing client care services; reimbursement may also be denied for some services provided by aides. Where permitted, the OT may delegate routine tasks to aides to increase productivity.7

Teamwork with Other Professionals

Many healthcare workers collaborate in the care of persons with physical disabilities. Depending on the setting, the OT may work together with physical therapists (PT), speech and language pathologists (SLP), activity therapists, recreational therapists, nurses, vocational counselors, psychologists, social workers, pastoral care specialists, orthotists, prosthetists, rehabilitation engineers, vendors of durable medical equipment, and physicians from many different specialties.

Relationships among and expectations of various healthcare providers are often determined by the context of care or setting. For example, in some situations, home care services are coordinated by a nurse. In a hospital or rehabilitation setting using a medical model, the physician most often directs the client care program. Some rehabilitation facilities employ a team approach to assessment and intervention, which reduces duplication of services and increases communication and collaboration. Several individuals from different professions may together perform a single evaluation. For example, the OT may be the lead member of the team in some settings or may be the director of rehabilitation services. In a team, members adjust scheduling and expectations to collaborate with one another to promote effective client care.

Many factors affect relationships among professionals across disciplines: the intervention setting, reimbursement restrictions, licensure laws and other jurisdictional elements, and the training and experience of the individuals involved. Relationships develop over time, based on experience and interaction and sometimes on personality. Even where formal jurisdictional boundaries may appear to limit roles for OT, informal patterns often develop at variance with the prescribed rules. For example, although in some states a physician’s referral may be required to initiate OT service, the physicians may expect the OT to initiate the referral and actually perform a cursory screening before the physician becomes involved. Some physicians rely on OT staff to identify those clients who are most likely to benefit from occupational therapy service, and they generate referrals upon the recommendation of the OT.

Another example in which interdisciplinary boundaries may be at variance with actual practice is in the relationships among the rehabilitation specialists of OT, PT, and SLP. By formal definition, each discipline has a designated scope of practice, with some areas of overlap and occasional dispute. The scope of occupational therapy practice is described in the Domain of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework–25 and in the AOTA document titled “Scope of Practice.”8 Nonetheless, it is common for practitioners to share skills and caseloads across disciplines and to train each other to provide less complex aspects of each discipline’s care. Two terms used to describe this are cross training and multiskilling.

Cross training is the training of a single rehabilitation worker to provide services that would ordinarily be rendered by several different professions. Multiskilling is sometimes used synonymously with cross training but may also mean the acquisition by a single healthcare worker of many different skills. Arguments have been made for and against cross training and multiskilling.22,34,62,82 The consumer may benefit by having fewer healthcare providers and better integration of services. Involving fewer providers may reduce costs.

The disadvantages cited include the prospect of erosion of professional identity, possible risk to consumers of harm at the hands of less skilled providers, and ceding the control of individual professions to outside parties such as insurers and advocates of competing professions.

Ethics

Although the study of ethics within an OT curriculum may be addressed as a separate course or topic, clinicians encounter ethical dilemmas with surprising frequency. In an ethics survey conducted by Penny Kyler for the AOTA in 1997 and 1998,46 clinician respondents ranked the following as the five most frequently occurring ethics issues confronting them in practice:

1. Cost-containment policies that jeopardize client care

2. Inaccurate or inappropriate documentation

3. Improper or inadequate supervision

4. Provision of treatment to those not needing it

5. Colleagues violating client confidentiality46

Additional concerns were related to conflict with colleagues, lack of access to OT for some consumers, and discriminatory practice. Further, 21% of clinicians reported they faced ethical dilemmas daily, 31% weekly, and 32% at least monthly.46

The AOTA has provided several documents to assist OT practitioners in analyzing and resolving ethical questions: the “Occupational Therapy Code of Ethics and Ethics Standards,”4 the “Core Values and Attitudes of Occupational Therapy Practice,”2 the “Standards for Continuing Competence,”10 and the “Scope of Practice.”8 Whereas these documents provide a basis for resolving ethical issues, practitioners may find additional resources and support if they also approach institutional ethics committees and review boards for guidance. Kyler46 also suggests that OT practitioners act to formalize resolutions for recurring questions by engaging with peers and others to analyze and consider courses of action.

Lohman et al.50 expand the discussion of ethical practice to include the public policy arena. Instead of occupational therapy only considering ethical practice from a perspective of service delivery to an individual, they recommend the OT practitioner consider the need to influence public policy to better serve all clients.

To reiterate, OT practitioners should anticipate that they will frequently encounter ethical distress (defined as the subjective experience of discomfort originating in a conflict between ethical principles) in clinical practice. Many approaches may be useful. A plan of action for addressing ethical distress and resolving ethical dilemmas may involve the following:

Summary

The occupational therapy process begins with referral and ends with discontinuation of service. Although discrete stages can be named and described as evaluation, intervention, and outcomes, the process is more spiraling and circular than stepwise. The processes of evaluation, intervention, and outcomes influence and interact with one another. This may look confusing to the novice, but it is actually a hallmark of clinical reasoning.

Different types of clinical reasoning are simultaneously employed to make decisions about the form and type of service provided. While logically analyzing how to proceed through the steps of therapy using procedural reasoning, the therapist also considers how best to interact with the client. Further, the therapist creates scenarios of possible future situations. The expert clinician seeks to uncover how the client understands the disability and uses a narrative or story making approach to capture the client’s imagination of how therapy will benefit him or her. This process is also influenced by the pragmatic reasoning that draws attention to the demands of the current healthcare arena.

The OT profession endorses client-centered practice, engaging the client in all stages of decision making, beginning with assessment. To make this ideal, a clinical reality requires that the OT approach every client as a co-participant and assist the client in identifying and prioritizing goals and in considering and selecting intervention approaches.

The occupational therapist and occupational therapy assistant have specific responsibilities and areas of emphasis within the OT process. The OT is the manager and director of the process and delegates specific tasks and steps to the qualified OTA. Aides may also be employed to extend the reach of OT services.

Effective practice typically involves interactions with members of other professions. This requires that the OT practitioner consider the intervention setting, the scope of practice of other professions, the applicable jurisdictions and healthcare regulations, and other factors (e.g., culture, personality, and history) that affect the individual situation.

Ethical questions arise with increasing frequency in modern healthcare. The AOTA provides guidelines and other resources; practitioners are urged to consider institutional and local resources as well, and to take an active role in identifying and resolving ethical concerns.

Section 2 Practice Settings for Physical Disabilities

WINIFRED SCHULTZ-KROHN, HEIDI MCHUGH PENDLETON, with contributions from MAUREEN MICHELE MATTHEWS, MICHELLE TIPTON-BURTON

Individuals who have a physical disability receive occupational therapy services in a variety of settings. These may include acute care hospitals, acute inpatient rehabilitation, subacute rehabilitation, outpatient clinics, skilled nursing facilities, assistive living units, home health, day treatment, community care programs, and work sites. Regardless of the physical setting in which services are delivered, the OT should always focus on enhancing occupational performance to support participation across contexts. The OT practitioner needs to be mindful of the supports and constraints encountered in the various practice settings.

A practice setting refers to the environment in which OT intervention occurs, an environment that includes the physical facility or structure along with the social, economic, cultural, and political situation that surrounds it. Several factors influence the delivery of OT service within a specific practice setting including the following: (1) government regulations, (2) the economic realities of reimbursement rules, (3) the workplace pressures of critical pathways and other clinical protocols, (4) the range of services that are considered customary and reasonable, and (5) the traditions and culture that the staff have developed over time.

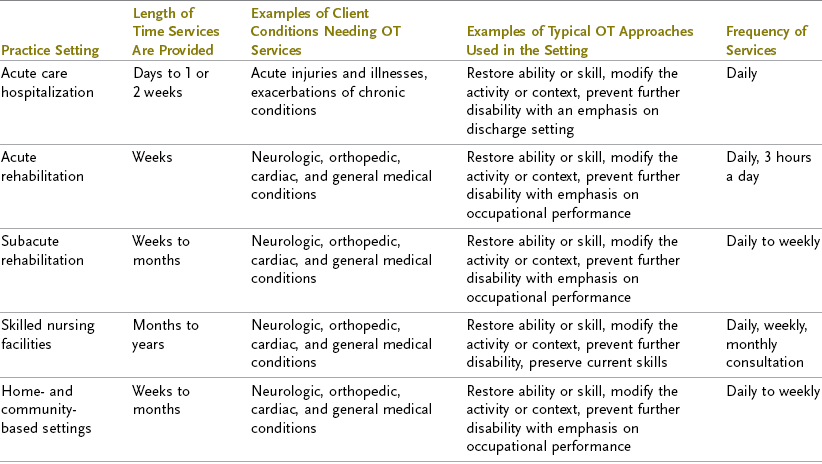

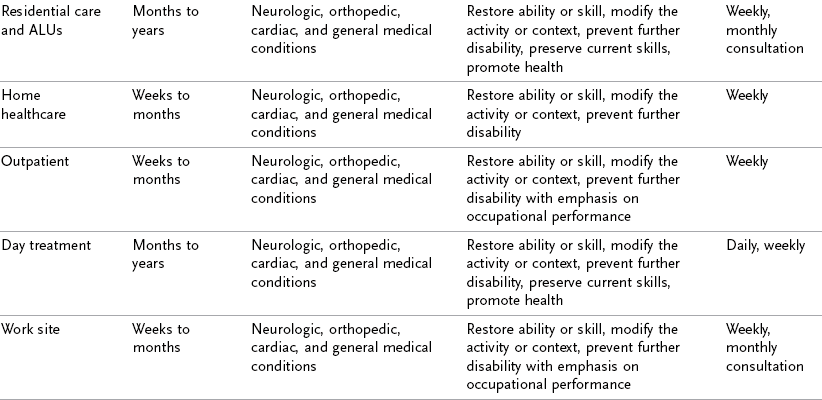

In addition, there are physical aspects such as the building itself, the temperature and humidity of the air, the colors and materials that are used, the layout of the space, and the furnishings and lighting. Practitioners must always be aware that context influences client performance in evaluation and intervention. The practice setting also influences the type of intervention available.60 Length of stay (LOS) and limitations on the numbers of visits require the OT practitioner to carefully examine intervention that can produce outcomes within the allotted time. Each practice setting has unique physical, social, and cultural circumstances that influence the individual’s ability to engage in occupations or activities. These environmental features are important to consider when projecting how the client will perform in another setting. For example, individuals who are in control in their home environment may abdicate control for even simple decisions in an acute care hospital, giving the erroneous impression of being passive and indecisive.16 The following section describes the typical practice settings in which OT services are provided for persons with physical disabilities. Table 3-2 provides a comparison of the approaches used at the various settings, the length of time services are provided, and the frequency of services. Notice that although the typical client conditions do not substantially change across settings, the approaches change to meet the client’s needs. Suggestions for modifications of the therapeutic environment and clinical approach are given.

Continuum of Healthcare

The variety of settings forms a continuum of care, albeit not always in a sequential fashion, for the client who has a physical disability. Persons with physical disabilities who are referred to occupational therapy services may enter the healthcare system at any point on the continuum and do not necessarily follow a direct progression through the various settings described here. A client in an acute hospital might be referred for bed mobility, transfers, and self-care retraining. Depending on the severity of the condition and the potential to improve, the client may be seen in a rehabilitation or day treatment program. A home health or outpatient therapist may see the same individual to address unresolved problems and modify the home environment to maximize occupational performance. Should the client return to the workforce, he or she may benefit from occupational therapy services, such as an assessment and recommendations about modifications to the work environment or job tasks (see Chapter 14). Evidence has demonstrated the effectiveness of OT services in helping individuals return to work after they have experienced a disabling condition.52 Some hospitals offer a range of healthcare services from an emergency room and acute care or intensive care unit (ICU) to inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation services. Other settings may offer only outpatient rehabilitation services.

Inpatient Settings

Settings in which the client receives nursing and other healthcare services while staying overnight are classified as inpatient settings.