Facial Pain and Neuromuscular Diseases

BELL’S PALSY (IDIOPATHIC SEVENTH NERVE PARALYSIS; IDIOPATHIC FACIAL PARALYSIS)

Bell’s palsy is a dramatic but self-limiting, unilateral facial paralysis. It represents the most common form of facial paralysis. A variety of potential triggering events are known (Box 18-1), although a trigger cannot be identified in at least one fourth of all cases. The precise cause remains unclear; however, familial occurrences have been reported, and suspected causes include reactivation of herpes simplex or zoster in the geniculate ganglion, nerve demyelination, nerve edema or ischemia, autoimmune damage to nerves, and vasospasm of vessels associated with nerves.

A similar presentation can be seen with obvious damage to the facial nerve (e.g., from facial and salivary gland tumors or from severance of the nerve caused by trauma or surgery). When the cause is known, the term Bell’s palsy is not usually used.

Bell’s palsy is diagnosed in 24 of every 100,000 persons each year, with increased frequency in the fall and winter seasons. In demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (MS), it occurs much more frequently (one in five cases), usually appearing late in the disease but occasionally being the first symptom. Rarely, other anatomic sites also will become paralyzed, usually in persons with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (see page 342), Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi infection, Lyme peripheral facial palsy, transient facial nerve palsy), or sarcoidosis.

CLINICAL FEATURES: People of all ages are susceptible to Bell’s palsy, but middle-aged people are affected most frequently. Women are affected more often (71%) than men. Childhood involvement is usually associated with a viral infection, Lyme disease, or earache.

Considerable variation exists in the severity of signs and symptoms. The palsy is characterized by an abrupt loss of muscular control on one side of the face, imparting a rigid masklike appearance and resulting in the inability to smile, to close the eye, to wink, or to raise the eyebrow (Fig. 18-1). A few patients, especially those with MS, experience prodromal pain on the affected side before the onset of paralysis. Infrequently, bilateral involvement is seen. The paralysis may take several hours to become complete, but patients frequently awaken in the morning with a full-fledged case. Rapid onset of bilateral facial weakness should alert the clinician to the possibility of such diseases as Guillain-Barre syndrome, a form of sarcoidosis known as uveoparotid fever (see Heerfordt’s syndrome, page 339), or other types of vasculitis causing multiple cranial neuropathies. If multiple cranial nerve deficits accompany the observed facial weakness, then central nervous system (CNS) infectious diseases and basilar skull tumors must be considered in the differential diagnosis. When vertigo or tinnitus is a major symptom, an occult herpes zoster ear infection should be suspected, and the diagnosis may be changed to Ramsay Hunt syndrome (see page 252).

Fig. 18-1 Bell’s palsy. Paralysis of the facial muscles on the patient’s left side. A, Patient is trying to raise the eyebrows. B, Patient is attempting to close the eyes and smile. (Courtesy of Dr. Bruce B. Brehm.)

The corner of the mouth usually droops, causing saliva to drool onto the skin. Speech becomes slurred and taste may be abnormal. Because the eyelid cannot close, conjunctival dryness or ulceration may occur.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: No universally preferred treatment exists for Bell’s palsy. Histamine and other vasodilators may shorten the duration, as will systemic corticosteroids and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Surgical decompression of the intratemporal facial nerve is used in select cases. Topical ocular antibiotics and artificial tears may be required to prevent corneal ulceration, and the eyelid may have to be taped shut.

Symptoms usually begin to regress slowly and spontaneously within 1 to 2 months of onset; more severe cases take longer, as do those in older patients. Overall, more than 82% of patients recover completely within 6 months. Residual symptoms that remain after 1 year will probably remain indefinitely. Recurrence is rare, except in Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome.

TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA (TIC DOULOUREUX; TIC)

The head and neck region is a common site for neuralgias (pain extending along the course of a nerve) (Box 18-2). Because facial neuralgias produce pain that often mimics pain of dental origin, the dental profession is frequently called on to rule out odontogenic or inflammatory causes. Trigeminal neuralgia, the most serious and the most common of the facial neuralgias, is characterized by an extremely severe electric shocklike or lancinating (i.e., sharp, jabbing) pain limited to one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve. In the majority of cases the pain is located in the maxillary (V2) or the mandibular (V3) distribution of the nerve. It is often idiopathic but is usually associated with pathosis somewhere along the course of the nerve. Occasionally, trigeminal neuralgia results from a brainstem tumor or infarction and is referred to as secondary trigeminal neuralgia.

Trigeminal neuralgia is diagnosed in 6 of every 100,000 persons each year, but it develops in 4% of per-sons with multiple sclerosis (MS). Moreover, patients with neuralgia-inducing cavitational osteonecrosis (NICO) of the jaws (see page 866), Gradenigo syndrome (suppurative otitis media, trigeminal nerve pain, abducens nerve palsy), and chronic paroxysmal hemicrania-tic syndrome may have pain so similar as to be virtually indistinguishable from trigeminal neuralgia.

Because so many of its features are consistent with a CNS disease, trigeminal neuralgia has been called “a pain syndrome with a peripheral cause but a central pathogenesis.” The seriousness of the disorder is underscored by the fact that it has one of the highest suicide rates of any disease and is regarded as one of the most painful afflictions known.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Trigeminal neuralgia characteristically affects individuals older than 40 years of age (the average age at onset is 50 years), although it may affect persons as early as puberty. Women are affected slightly more often than men, and the right side is involved more often than the left. Any branch of the trigeminal nerve may be involved, but the ophthalmic division is affected in only 5% of cases. More than one branch may be involved, and the pain is occasionally bilateral.

Specific and strict criteria must be met for an accurate diagnosis (Box 18-3). If the pain pattern does not meet these criteria, then a different diagnosis should be considered. When these criteria are partially fulfilled, alternative terms such as atypical trigeminal neuralgia, atypical facial pain, and atypical facial neuralgia are applied.

In the early stages, the pain of trigeminal neuralgia may be rather mild and is often described by the patient as a twinge, dull ache, or burning sensation. This clinical presentation may be erroneously attributed to disorders of the teeth, jaws, and paranasal sinuses and lead to escalation of treatment and a variety of therapeutic misadventures. Many documented cases of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia are preceded by this dull, continuous, aching type of jaw pain that may persist for days to years without obvious dental pathology before the onset of the characteristic paroxysmal pain in the same region of the face. This has come to be regarded in the literature as pretrigeminal neuralgia. Pretrigeminal neuralgia has been reported in approximately 18% of documented trigeminal neuralgia cases. Moreover, pretrigeminal neuralgia has shown a dramatic response to carbamazepine in controlled clinical drug trials.

There are long, asymptomatic refractory periods between painful attacks. With time, the attacks occur at more frequent intervals and the pain becomes increasingly intense. At this point, patients often state that the pain is like “a lightning bolt” or a “hot ice pick jabbed into the face.” A distinguishing feature of trigeminal neuralgia is that objective signs of sensory loss cannot be demonstrated on physical examination. The presence of objective facial sensory loss, facial weakness, or ataxia should raise the distinct possibility of a CNS tumor.

Although individual pains or pain spasms last only a few seconds, several attacks may follow each other for up to 30 minutes of rapidly repeating volleys. Patients often clutch at the face and experience spasmodic contractions of the facial muscles during attacks, a feature that long ago led to the use of the term tic douloureux (i.e., painful jerking) for this disease. Similar to other neuralgic disorders, a refractory period follows a paroxysm of pain during which time the pain cannot be elicited. This refractory period can be useful, clinically, in distinguishing neuralgic pain from a stimulus-provoked odontogenic pain source. The paroxysmal facial pain is occasionally accompanied by excess lacrimation, conjunctival injection, and intense headache. This presentation may represent the SUNCT (short-lasting, unilateral, neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing) syndrome rather than trigeminal neuralgia. Other differential considerations include but are not limited to glossopharyngeal neuralgia, Raeder’s syndrome, atypical facial pain, and cluster headache. Raeder’s syndrome is applied to pain of trigeminal distribution usually in the ophthalmic distribution in association with an ocular sympathetic deficit comprising ptosis, miosis, and an impairment of sweating limited to the medial aspect of the forehead. Because this constellation of clinical findings may have a variety of causes, the recognition of Raeder’s syndrome serves only to draw attention to the region of the disturbance and does not imply causation.

When an obvious trigger point is present in trigem-inal neuralgia, a pain attack may be brought on by a stimulus to the area as mild as a breeze, a gentle movement, or a feather-light touch. Trigger points are found most frequently on the nasolabial fold, the vermilion border of the lip, or the midfacial and periorbital skin. Intraoral trigger points are uncommon but do occur, especially on the alveolus.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: No unique histopathologic characteristic to the nerves in trigeminal neuralgia exists, although the trigger points may show fibrosis and infiltration by small numbers of chronic inflammatory cells. Focal areas of myelin degeneration have been reported within the gasserian ganglion and along the course of the cranial nerve itself, but these also have been occasionally seen in persons without trigeminal neuralgia. MS patients with trigeminal neuralgia show unique amorphous plaques in the ganglion.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: There have been rare reports of spontaneous permanent remissions of trigeminal neuralgia. However, more often than not, this disease is characterized by a protean and protracted clinical course with regard to the frequency and severity of exacerbations. The initial treatment for trigeminal neuralgia is medical. Topical capsaicin cream (a nociceptive substance-P suppressor) over the affected skin may be effective. Almost all patients with trigeminal neuralgia respond favorably to the anticonvulsant, carbamazepine, and an unequivocal response to this medication can be used as a diagnostic test for this disease. Anticonvulsant medica-tions (phenytoin, carbamazepine, gabapentin) often are effective in pain control, probably because they decrease conductance in Na+ channels and inhibit ectopic (i.e., arising from abnormal sites) discharges. These drugs, unfortunately, often have severe side effects and may not be tolerated for long by the patient. Moreover, the pain usually returns on discontinuance of the medication. If drug treatment fails, then surgical therapy may be considered.

Various neurosurgical procedures such as microvascular decompression and radiofrequency rhizotomy also are effective in severe or refractory cases, especially in younger patients (Box 18-4). Recent reports have shown some success with gamma knife radiosurgery of the gasserian ganglion and its associated nerves.

Neurosurgical methods provide relief for years in the majority of trigeminal neuralgia patients. Repeated surgical procedures often are necessary, however, and techniques that deliberately damage neural tissues leave the patient with a sensory deficit. After surgery, up to 8% of patients develop distorted sensations of the facial skin (facial dysesthesia) or a combination of anesthesia and spontaneous pain (anesthesia dolorosa). Anesthesia dolorosa is a dreaded form of central pain that can occur after any neurosurgical procedure that causes a variable amount of sensory loss, but this complication occurs more commonly with proce-dures that totally denervate a region. Overall, long-term success from surgical procedures is 70% to 85%.

GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA (VAGOGLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA)

Neuralgia of the ninth cranial nerve, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, is similar in every way to trigeminal neuralgia (see previous topic) except in the anatomic location of the pain. In glossopharyngeal neuralgia, the pain is centered on the tonsil and the ear. The pain often radiates from the throat to the ear because of the involvement of the tympanic branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve. Some unfortunate individuals have a combination of glossopharyngeal neuralgia and trigeminal neuralgia.

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is rare, occurring only once for every 100 cases of trigeminal neuralgia. The pain also may affect sensory areas supplied by the pharyngeal and auricular branches of the vagus nerve. As with trigeminal neuralgia, the cause is unknown.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The age of onset for glossopharyngeal neuralgia varies from 15 to 85 years, but the average age is 50 years. There is no sex predilection, and only rarely is there bilateral involvement. The paroxysmal pain may be felt in the ear (tympanic plexus neuralgia), infra-auricular area, tonsil, base of the tongue, posterior man-dible, or lateral wall of the pharynx; however, the patient often has difficulty localizing the pain in the oropharynx.

The episodic pain in this unilateral neuralgia is sharp, lancinating (jabbing), and extremely intense. Attacks have an abrupt onset and a short duration (30- to 60-second bursts that may repeat for 5 to 30 minutes). The pain typically radiates upward from the oropharynx to the ipsilateral ear. Talking, chewing, swallowing, yawning, or touching a blunt instrument to the tonsil on the affected side may precipitate the pain, but a definite trigger zone is not easily identified. Because the pain is related to jaw movement, it may be difficult to differentiate it from the severe pain of temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD).

Patients frequently point to the neck immediately below the angle of the mandible as the site of greatest pain, but trigger points are not found on the external skin, except within the ear canal. Rarely, syncope, hypotension, seizures, arrhythmia, or cardiac arrest may accompany the paroxysmal pain, as may coughing or excessive salivation. As with trigeminal neuralgia, idiopathic and secondary forms of glossopharyngeal neuralgia exist. The clinician should be careful to rule out Eagle syndrome (see page 23) and other conditions before applying the glossopharyngeal neuralgia diagnosis. The literature suggests that approximately 25% of cases of glossopharyngeal neuralgia are the result of secondary causes such as neoplasms involving the skull base or aneurysms in the posterior cranial fossa.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: As in trigeminal neuralgia, glossopharyngeal neuralgia is subject to unpredictable remissions and recurrences. It is not unusual during the early stages for remissions to last 6 months or more. Painful episodes are of varying severity but generally become more severe and more frequent with time.

Approximately 80% of patients experience immediate pain relief when a topical anesthetic agent is applied to the tonsil and pharynx on the side of the pain. Because this relief lasts only 60 to 90 minutes, it is used more as a diagnostic tool and emergency measure than a long-term treatment. Repeated applications to a trigger point for 2 or 3 days may extend the pain-free episode enough to allow the patient to obtain much needed rest and nutrition. Carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, baclofen, phenytoin, and lamotrigine may relieve the neuralgic pain for a long period, but no therapy is considered to be uniformly effective or even adequate. Moreover, glossopharyngeal neuralgia is considerably less responsive than trigeminal neuralgia to treatment with anticonvulsant medications. If the patient fails drug therapy, then surgical options should be considered. The preferred neurosurgical treatments are microvascular decompression or surgical sectioning of the glossopharyngeal nerve and the upper two rootlets of the vagus nerve.

POSTHERPETIC NEURALGIA

An acute painful disorder (herpes zoster) (see page 250) and a chronic pain syndrome (postherpetic neuralgia [PHN]) are associated with the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Herpes zoster, commonly referred to as shingles, is characterized by a unilateral vesicular eruption within a dermatome. More often than not, this eruption is accompanied by severe pain. Herpes zoster usually involves the thoracic dermatomes; in 23% of cases, the rash and its associated pain follow a trigeminal distribution. The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (V1) is affected most frequently. Herpes zoster is caused by the reactivation of the latent VZV that is thought to lie dormant in the gasserian, geniculate, and dorsal root ganglia after chickenpox infection in early life. The onset of acute herpes zoster is frequently preceded by exquisite pain in the affected dermatome. Approximately 48 to 72 hours later, an erythematous maculopapular rash evolves rapidly into vesicular lesions (see discussion of herpes zoster, page 250).

When the trigeminal nerve is involved, the lesions may appear on the face, the eye, and the tongue. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is a debilitating condition that can result in blindness if aggressive antiviral therapy is not promptly instituted. The combination of a herpetic rash in the external auditory canal and a facial palsy secondary to viral invasion of the geniculate ganglion of the sensory branch of the facial nerve is known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome (see page 252). Often these patients lose their taste discrimination in the anterior two thirds of the tongue before the development of the ipsilateral facial palsy.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The most significant complication of herpes zoster is the pain that is associated with acute neuritis and PHN. PHN is defined as pain persisting for anywhere from 1 to 6 months or more after the onset of the rash. Postherpetic pain is described as a burning sensation with episodic “stabbing” pains. Light touch over the previously involved area may elicit a painful response (tac-tile allodynia) from the patient. Changes in sensation within the affected area may result in hypoesthesia or hyperesthesia.

The pain of PHN should not be confused with “shocklike” pain of trigeminal neuralgia that can be triggered by similar stimuli. The pain is constant and described as “burning and aching.” The burning character of the pain is thought to be the result of spontaneous activity in nociceptor C fibers. The VZV damages the peripheral nerve by a combination of demyelination, wallerian degeneration, fibrosis, and sclerosis. The pain associated with PHN is thought to arise from a disturbed pattern of afferent impulses combined with the loss of some central inhibitory influence in the pain modulatory systems. The mechanism of the pain in PHN is characteristic of deafferentation pain. Pathologically, degenerative lesions are observed in the axons, the dorsal root ganglion, and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

Age appears to be the major risk factor associated with the development of PHN. Approximately 50% of patients over the age of 50 with herpes zoster report some pain in the affected dermatome after the resolution of the cutaneous presentation, and 75% of patients older than 70 years of age are afflicted. Severe pain in the acute phase of the disease (acute neuritis) combined with advanced age appears to make the patient more prone to the development of PHN. Another susceptible group consists of those patients with diseases that compromise immunity.

Clinically, scarring and pigmentary changes are observed within the affected dermatome. The pain is usually accompanied by a sensory deficit. Researchers have found lowered sensory thresholds for cold, warmth, vibration, and two-point discrimination in patients whose rash was followed by neuralgia pain. In one recent study, allodynia (i.e., pain in response to a nonnoxious stimulus) was present in 85% of patients with PHN.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: As with most diseases, the best treatment option is prevention. Many argue that the administration of antiviral medication (most notably famciclovir) or corticosteroids, either alone or in combination, early in the course of herpes zoster possibly could prevent the development of PHN. Patients with acute herpes zoster benefit from the administration of oral antivirals. Accelerated healing of the lesions and an attenuation of zoster-associated pain have both been reported in placebo-controlled clinical drug trials. Further research is necessary to determine the most predictable way of preventing PHN.

Once PHN has established itself, a variety of treatment options are available for pain management. In addition to the judicious use of analgesics, including both nonnarcotic and narcotic preparations, a wide variety of drugs ranging from gabapentin, pregabalin, and amitriptyline hydrochloride to topical agents, such as lidocaine patches, EMLA (eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine), and capsaicin (0.025%), have been reported to be beneficial in pain relief. The topical application of capsaicin, an extract of hot chili peppers, has been reported to deplete the neurotransmitter substance P from nerve terminals, thereby desensitizing them.

Tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and desiprimine have proven to be quite useful in the management of the persistent pain that characterizes PHN; however, the anticholinergic and cardiovascular side effects may limit their utility, especially in older patients. Amitriptyline has consis-tently proven to be the single most effective drug, with approximately 60% of patients reporting relief with this agent. Patients are started at a low dose (10 mg) and titrated to effect, with the majority of patients obtaining significant relief with a median dose of 75 mg daily. These medications are usually given at bedtime to prevent daytime somnolence and to improve tolerance. Patients who report a stabbing pain in addition to the burning sensation may derive additional benefit from the use of anticonvulsant medications such as carbamazepine or phenytoin. In recent studies, gabapentin and pregabalin have been shown to reduce pain associated with PHN by more than 30%, and these drugs are typically well tolerated in all patient cohorts.

Patients who fail medical therapy have a limited range of surgical treatments available to them. How-ever, the outcome of procedures (e.g., blockade of peripheral nerves, roots, or sympathetic nervous system; surgery at the level of the affected nerve [neurectomy] or dorsal root) is far from certain with regard to pain management.

ATYPICAL FACIAL PAIN (ATYPICAL FACIAL NEURALGIA; IDIOPATHIC FACIAL PAIN; ATYPICAL TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA; TRIGEMINAL NEUROPATHIC PAIN)

The International Headache Society (IHS) defines atypical facial pain as “persistent facial pain that does not have the characteristics of the cranial neuralgias classified above and is not associated with physical signs or a demonstrable organic cause.” In short, atypical facial pain is defined less in terms of what it is but rather in terms of what it is not. In other words, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, and its use by the clinician implies that all potential causes of pain have been ruled out (Box 18-5). Although not the most common facial pain, this condition is the facial disease that most often brings a patient to a pain clinic. No acceptable population studies are available.

Atypical facial pain is such a difficult diagnostic and therapeutic condition that patients travel from one health professional to another and receive many different diagnoses and treatments in a frustrated attempt to find relief. Patients are often described as being neurotic (“hysterical”) and suffering from hypochondriasis, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorder, depression, somatization disorder, or a “lack of insight.” Whether this is true or not, the strong emotional overtones of this condition make it difficult to distinguish functional (psychogenic) from organic (physiologic) pain.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Atypical facial pain affects women far more frequently than men. It usually develops during the fourth through sixth decades of life, but can occur as early as the teenage years. The pain may be localized to a small area of the face or alveolus (e.g., atypical odontalgia, “phantom” toothache) but more frequently affects most of a quadrant and may extend to the temple, neck, or occipital area. Patients have great difficulty describing the pain, but most often portray it as a continuous, deep, diffuse, gnawing ache; an intense burning sensation; a pressure; or a sharp pain. The patient may nominally describe the pain using such terms as “drawing, aching, or pulling.” It is important to differentiate the pain from that of trigeminal neuralgia (see page 861).

Bilateral involvement occasionally occurs, and patients frequently attribute the onset of the pain to trauma or a dental procedure. The mucosa of the affected quadrant appears normal but typically contains a zone of increased temperature, tenderness, or bone marrow activity (“hot spot” on technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate [MDP] bone scan). Radiographic changes are not present. In some cases initially diagnosed as atypical facial pain, significant underlying disease has ultimately been identified (e.g., nasopharyngeal carcinoma, occult lung tumors).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Occasional cases of spontaneous remission are noted, but the great majority of atypical facial pain patients will obtain little relief without therapy. Symptoms tend to become more intense gradually, and patients become irritable, fatigued, and depressed. Most patients are not benefited substantially from the drugs used for trigeminal neuralgia, although the new anticonvulsant, gabapentin, dramatically reduces the pain in one third of affected patients. Opioid analgesics (codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, morphine, and oxycodone) may be of considerable benefit, but their effectiveness characteristically diminishes over time and, of course, they are associated with the risk of abuse and addiction.

The tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, nortriptyline) are popular therapies for neuropathic pain. They appear to block reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin, transmitters released by pain-modulating systems in the spinal cord and brain stem, thereby allowing long periods of diminished neural activity. Other antidepressants (e.g., the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, paroxetine and citalopram) are generally not as effective as the tricyclic antidepressants for managing atypical facial pain, although some patients may respond to this therapy. It is important to remember, however, that antidepressant medications may be quite hazardous to frail older adults or to patients with coronary disease. When a localized area (usually alveolar) of tenderness can be found in the quadrant of pain, the application of topical capsaicin or injection with local anesthetics may be temporarily beneficial. Psychotherapy, behavior modification, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation, and sympathetic nerve blocks are helpful in a subset of patients with atypical facial pain.

The frequent failure of medical treatment for atypical facial pain may lead to surgical intervention, usually the removal of a portion of the affected trigeminal nerve branch or the injection of a caustic solution (phenol, glycerol, alcohol) into the nerve, designed to destroy a portion of the nerve. These therapies often provide relief for several weeks or months, but there is seldom a permanent cure.

NEURALGIA-INDUCING CAVITATIONAL OSTEONECROSIS (NICO; ALVEOLAR CAVITATIONAL OSTEOPATHOSIS; ISCHEMIC OSTEONECROSIS; BONE MARROW EDEMA)

One of the most controversial topics in the diagnosis and management of orofacial pain is the entity referred to as neuralgia-inducing cavitational osteonecrosis (NICO). Since this concept first appeared in the scientific literature in the late 1970s, there have been numerous attempts by science-based investigators to define the clinical and radiographic features, as well as the histopathology and neuropathology of these lesions. However, to date, there is no consensus among pain practitioners regarding this entity. The following information is presented in the context of completeness with regard to orofacial pain and to facial neuralgias in particular.

Ischemic osteonecrosis is a bone disease characterized by degeneration and death of marrow and bone from a slow or abrupt decrease in marrow blood flow. Along with its lesser variants, bone marrow edema and regional ischemic osteoporosis, it is one of the most common bone diseases in humans, but only recently has it been appreciated as a disorder of the head and neck region. Numerous local and systemic factors are associated with ischemic damage to marrow (Box 18-6), the most common being a hereditary (autosomal dominant) tendency toward blood clot formation within blood vessels. Bone is particularly susceptible to this problem, which in the jaws may be accentuated by dental infections and the vasoconstrictors in local anesthetics.

The ischemia and infarctions of osteonecrosis are typically associated with pain, often with an ill-defined neuralgic or neuropathic character. Because of this, presumed examples of this process in the jaws have been referred to as NICO. NICO is included in this chapter because of its strong association with pain, but it should be remembered that osteonecrosis is not necessarily a painful condition and our understanding of this disease is still incomplete.

Ischemic osteonecrosis most often affects the hips, maxillofacial bones, and knees. NICO has been found in 1 of every 11,000 adults, a prevalence rate similar to that of hip cases. The NICO prevalence rate for women (1 per 2000) is much higher than the rate for men (1 per 20,000).

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: NICO characteristically affects women 35 to 60 years of age but has been diagnosed in men and in teenagers. Third molar regions are affected in half of all cases, but any alveolar site may become involved, as may the walls of the sinuses and the mandibular condyle. At least one third of patients have more than one maxillofacial site of involvement, and 10% have lesions in all four alveolar quadrants.

Patients often have trouble describing and localizing their pain, which can be intermittent or constant, deep or superficial, aching or sharp, mild or extremely intense. Most often the pain is described as a deep ache or sharp bone pain. It typically begins as quite mild and vague, increasing slowly in frequency and intensity over months and years, but may also have a sudden onset, especially after a dental procedure using vasoconstrictors in the anesthetic. The pain may roam in the general anatomic area or be referred some distance from the affected bone (neck, shoulder). Many describe pressure and deep burning sensations, and local anesthesia typically relieves the pain.

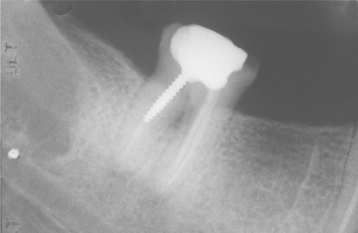

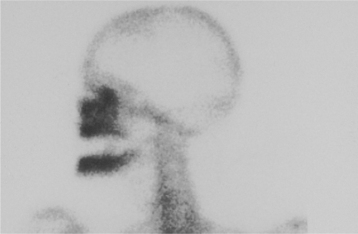

Osteonecrosis is not visualized readily on radiographs, but when visible it usually appears as an area of regional osteoporosis or ill-defined radiolucency, often with irregular vertical remnants of lamina dura representing old extraction sites (Fig. 18-2). Occasional lesions show an admixture of irregular sclerotic and radiolucent areas (ischemic osteosclerosis), or there may be a faint central sclerotic oval surrounded by a thick radiolucent circle that is, in turn, surrounded by a thick but faint sclerotic ring (bull’s-eye lesion). More than 60% of the lesions will exhibit a hot spot of increased isotope uptake with the technetium-99m MDP bone scan (Fig. 18-3).

Fig. 18-2 Neuralgia-inducing cavitational osteonecrosis (NICO). Periapical radiograph demonstrates an oval radiolucency in the third molar region and thin lamina dura remnants (residual socket) more anteriorly.

Fig. 18-3 Neuralgia-inducing cavitational osteonecrosis (NICO). Technetium-99m bone scan reveals multifocal and extensive NICO involvement (hot spots) years after extraction of the entire dentition for “atypical facial pain.” None of the sites were visualized by radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scans, or other forms of radioisotope bone scans.

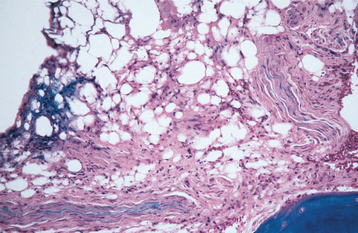

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The microscopic appearance of ischemic osteonecro-sis depends on the duration and intensity of the diminished marrow blood flow. The features of bone marrow edema include dilated marrow capillaries and sinusoids, serous ooze (plasmostasis) around blood vessels and adipocytes, wispy fibrous streaming (ischemic myelofibrosis) between fat cells, areas of dense fibrosis (intramedullary fibrous scar), and a light sprinkling of chronic inflammatory cells in regions of myelofibrosis (Fig. 18-4). Bony trabeculae usually remain viable at this stage but are inactive, thin, and often widely spaced.

Fig. 18-4 Neuralgia-inducing cavitational osteonecrosis (NICO). Photomicrograph showing ischemic myelofibrosis with a sprinkling of chronic inflammatory cells and serous ooze.

Degenerative extracellular cystic spaces (cavitations) are commonly seen and may dominate the picture, eventually coalescing to form spaces large enough to extend from cortex to cortex (Fig. 18-5). Focal areas of marrow hemorrhage (microinfarction) are frequently present and considered by some to be pathognomonic for osteonecrosis.

Fig. 18-5 Neuralgia-inducing cavitational osteonecrosis (NICO). Gross photo of section of posterior mandible showing extensive cavitation that has hollowed out most of the bone. (From Bouquot JE, McMahon RE: Neuropathic pain in maxillofacial osteonecrosis, J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 58:1003-1020, 2000.)

Bubbles of coalesced, liquefied fat (oil cysts) may be seen. However, because high-speed rotary instruments can produce similar bubbles as an artifact, it is important that only hand-curetted marrow samples be submitted for histopathologic evaluation.

Bone death, when present, is represented by focal loss of osteocytes. However, this feature can be evaluated properly only if formic acid or another very weak acid is used for slow, gentle laboratory decalcification. In addition, smudged, globular, often dark masses of calcific necrotic detritus may be seen. These represent destroyed trabeculae that have literally dissolved over time and contributed their calcium to other salts precipitated within necrotic fat. The heat of high-speed rotary instrumentation can create similar calcific debris, but this debris remains at the edges of tissue fragments.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Antibiotics may temporarily diminish the associated pain of NICO in those cases with a superimposed low-grade infection (chronic nonsuppurative osteomyelitis), but the pain typically returns when antibiotics are stopped. Usually the diseased marrow must be removed surgically by decortication and curettage. Once removed, the defect frequently heals and the intense facial pain subsides dramatically or disappears completely, although pain abatement may take several months to occur. Unfortunately, one third of patients thus treated experience no pain relief. In addition, the disease has a strong tendency to recur or to develop in additional jawbone sites. A repetition of the surgical procedure is, therefore, often necessary. Overall, the cure rate (free of pain for at least 5 years) for curettage is better than 70%.

CLUSTER HEADACHE (MIGRAINOUS NEURALGIA; SPHENOPALATINE NEURALGIA; HISTAMINIC CEPHALGIA; HORTON’S SYNDROME)

Cluster headache is an exquisitely painful affliction of the midface and upper face, particularly in and around the eye. The name is derived from the fact that the headache attacks occur in temporal groups or clusters, with extended periods of remission between attacks. Cluster headache is an uncommon disease of unknown origin and has been called “the most severe pain syndrome known to humans.” A vascular (vasodilation) cause has been suggested, possibly related to abnormal hypothalamic function, head trauma, or abnormal release of histamine from mast cells. The majority of patients suffer from sleep apnea and diminished oxygen saturation, but it is not known whether this is a cause or effect of the disease. Headache can be initiated by alcohol, cocaine, and nitroglycerin; 80% of affected persons are cigarette smokers.

This disorder is diagnosed in 10 of every 100,000 persons each year, and there is a predilection for blacks. There is also a strong familial influence: when a first-degree relative has the headache, there is a fiftyfold increase in the chance that another family member also will be affected.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Cluster headache may occur at any age, although it usually affects persons in the third and fourth decades of life and is rare before puberty. There is a strong male predilection (a 6:1 male-to-female ratio). The pain is almost always unilateral and follows the distribution of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve.

It is usually felt deep within or behind the orbit, radiating to the temporal and upper cheek regions. However, it may simulate a toothache or neuralgic jaw pain in the anterior maxillary region. Because of this, patients may be treated inappropriately for dental pain with endodontic therapy or tooth extraction, which is thought to be successful when the pain subsequently resolves. When each successive cluster returns, the next tooth is treated, sometimes resulting in multiple, repeated episodes of unnecessary dental therapy.

The pain is described as paroxysmal (i.e., abrupt onset) and intense, with a burning or lancinating quality and without a trigger zone. The attacks may last from 15 minutes to 3 hours and occur up to eight times daily (or on alternate days). The cluster periods typically last for weeks, with the intervening periods of remission usually lasting for months (sometimes years). The pain often begins at the same time in a given 24-hour period (alarm clock headache), with most attacks occurring in the middle of the night.

A chronic form occurs occasionally, with no re-missions for years at a time, and episodic forms may convert to the constant, chronic form. In addition, cluster headache is rarely accompanied by the aura so common to migraine headache. An important behavioral difference between migraine and cluster headache is that the patient is usually hyperactive during the latter and retreats to a dark, quiet room during the former.

In addition to the pain, the patient may experience autonomic alterations such as nasal stuffiness, tearing, facial flush, or congestion of conjunctival blood ves-sels. The latter sign, especially when associated with increased intraocular pressure, may indicate chronic paroxysmal hemicrania (Sjaastad syndrome), a rare syndrome with short-duration, highly recurring, nonclustered pain (see following topic).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The proper diagnosis is important to avoid sequential, unnecessary endodontic or extraction procedures. Systemic prednisone, ergotamine, lithium carbonate, indomethacin, methysergide maleate, and verapamil all provide relief in some cases. Sumatriptan (agonistic to 5-HTID receptors) and other drugs of this class shorten the symptoms in 74% of cases. However, no single drug is universally effective. Inhaling oxygen may abort impending attacks, and various neurosurgical interventions to the affected nerve have provided relief in some patients, as has the recently reported use of gamma knife radiosurgery. Overall, only 50% of patients with cluster headache benefit significantly and permanently from the available therapeutic modalities.

It is important to distinguish cluster headache from chronic paroxysmal hemicrania because the latter disease responds almost universally to indomethacin.

PAROXYSMAL HEMICRANIA

Paroxysmal hemicrania has a clinical presentation similar to cluster headache. The headaches are strictly unilateral, brief, and excruciating and have associated autonomic features. Paroxysmal hemicrania can be differentiated from cluster headache primarily by the high frequency but shorter duration of the attacks. Although the differentiation can be subtle, it is worth pursuing because paroxysmal hemicrania responds dramatically and predictably to indomethacin. Therefore, an “indomethacin challenge” can be used to rule out other trigeminal autonomic cephalgias. A predictable response to indomethacin is also observed in hemicrania continua, a type of chronic daily headache that is unilateral, moderately severe, and associated with autonomic signs similar to those of cluster headache.

CLINICAL FEATURES: In contradistinction to cluster headache, paroxysmal hemicrania is more common in women by a ratio of 2:1. The headache is for the most part strictly unilateral, and the pain is centered on the ocular, maxillary, temporal, and frontal regions. The symptoms typically last from 2 to 30 minutes, and the pain is described as a “boring” sensation that can be excruciating in terms of severity. The headache has an abrupt onset and an equally abrupt cessation. Ipsilateral cranial autonomic features such as lacrimation, conjunctival injection, and rhinorrhea also invariably occur. The patient may experience anywhere from 2 to 40 attacks daily, and the mean attack frequency is 14 per day. The headaches occur regularly throughout the 24-hour day and do not demonstrate a preponderance of nocturnal attacks as is commonly observed in cluster headache. About half of these patients desire reductions in stimuli similar to the preference demonstrated by those with migraines; the remaining 50% prefer hyperactivity during the attack similar to the response preference of individuals with cluster headache.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Indomethacin is the treatment of choice for paroxysmal hemicrania. Effective resolution of the headache is prompt, typically occurring within 1 to 2 days of initiating the effective dose. The therapeutic trial of oral indomethacin should be initiated at 25 mg three times daily for 10 days. If the response is suboptimal, then the dosage should be increased to 50 mg three times daily for an additional 10 days. If there is a suspicion that the optimal dose has not been achieved, the dosage can be increased further to 75 mg three times daily for an additional 14 days. The typical maintenance dose is between 25 mg and 100 mg daily, but higher doses can be tolerated relatively well. A “drug holiday” should be attempted at least once every 6 months because long-lasting remissions have been reported in some patients after cessation of indomethacin. Long-term treatment with indomethacin may result in the gastrointestinal side effects common to this class of drugs. These side effects can be effectively managed with antacids, histamine H2-receptor antagonists, or proton pump inhibitors. In patients who fail to demonstrate a predictable response to indomethacin, the diagnosis of paroxysmal hemicrania should be reconsidered.

MIGRAINE (MIGRAINE SYNDROME; MIGRAINE HEADACHE)

Migraine is a common, disabling, paroxysmal, unilateral headache that is experienced at least once by more than 14% of teenagers and young adults (lifetime risk: 21%). More than 400 new cases are diagnosed each year for every 100,000 persons. At least 14 different types of migraine exist; they are broadly classified into two groups: (1) migraine with aura and (2) migraine without aura.

The cause of migraine is still unclear, but it appears to be related to vasoconstriction or vasospasm of portions of the cerebral arteries, possibly in response to a chronically reduced activity of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT1). The vasoconstriction apparently leads to cerebral ischemia, which is followed by a compensating vasodilation (mediated by nitric oxide), with subsequent pain and cerebral edema. Many affected persons (migraineurs) have a family history of migraine, sometimes with a clear autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Migraine headaches are often associated with endogenous or environmental triggers. Common triggering events are listed in Table 18-1.

Table 18-1

Common Triggers for Migraine Headache

| Type of Trigger | Subtypes |

| Hormonal | Menstruation |

| Ovulation | |

| Oral contraceptives | |

| Hormonal replacement therapy | |

| Dietary | Alcohol |

| Nitrite-laden meat | |

| Monosodium glutamate | |

| Aspartame | |

| Chocolate | |

| Aged cheese | |

| Missing a meal | |

| Psychologic | Stress/poststress |

| Anxiety/worry | |

| Depression | |

| Physical/environmental | Glare |

| Flashing lights | |

| Fluorescent lights | |

| Odors | |

| Weather changes | |

| High altitude | |

| Sleep related | Lack of sleep |

| Excessive sleep | |

| Drugs | Nitroglycerine |

| Histamine | |

| Reserpine | |

| Hydralazine | |

| Ranitidine | |

| Estrogen | |

| Miscellaneous | Head trauma |

| Physical exertion | |

| Fatigue |

From Campbell JK, Sakai F: Diagnosis and differential diagnosis. In Olesen J, Tfelt-Hansen P, Welch KMA: The headaches, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2000, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Migraine affects women three times more frequently than men, and women tend to experience more severe attacks than men. The disease is most prevalent in the third through fifth decades of life, but the first symptoms often begin at puberty or shortly thereafter.

The unilateral headache lasts for 4 to 72 hours and is usually felt in the temporal, frontal, and orbital regions, as well as occasionally in the parietal, postauricular, or occipital areas. It begins as a poorly localized discomfort in the head that soon becomes a mild ache and then increases in severity over the next 30 minutes to 2 hours. At its peak, the pain has a throbbing quality, is quite severe, and is typically associated with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, photophobia, and phonophobia. Usually, the pain is so severe as to be incapacitating, and the patient must lie down in a dark, quiet room. The headache recurs frequently, although the time between attacks varies widely. Rarely, bilateral examples occur.

It is important for the dentist to remember that referred migraine pain may initially mimic a toothache, especially of the anterior maxilla. Symptoms may also mimic sinusitis or allergic rhinitis.

Many migraineurs experience an “aura” before the actual headache pain. The aura may appear as visual hallucination, “seeing sparks” (scintillation), temporary and partial blindness, partial or complete loss of light perception (scotoma), nausea, vertigo, lethargy, mental confusion, loss of the ability to express thou-ghts (aphasia), or unilateral facial paresthesia or weakness.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Nonpharmacologic approaches to the management of migraine involve the recognition and avoidance of known environmental triggers, as well as volitional modulation of the stress response (cognitive behavioral therapy). The pharmacologic treatment of migraine includes a wide variety of medications, and the two basic forms, with and without aura, respond in a similar fashion. The drugs that have shown the greatest efficacy in the treatment of migraine are members of the following three pharmacologic classes: (1) antiinflammatory agents, (2) 5-HT1 agonists, and (3) dopamine antagonists. The optimal treatment regimen for a migraine attack depends primarily on the severity of the attack and must be individualized for each patient. Severe attacks frequently are diminished by ergotamine tartrate, perhaps combined with caffeine, aspirin, acetaminophen, phenobarbital, or belladonna. The drugs known as triptans are selective 5-HT1 receptor agonists, and a variety of these medications are now available for the treatment of acute migraine attacks. Less severe but more frequent attacks are best treated prophylactically using other ergot compounds (e.g., methergine), b-adrenergic agents (e.g., propranolol, metoprolol), calcium channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine, diltiazem), or serotonin receptor agonists (e.g., methysergide, cyproheptadine). Some patients are aided by simple pressure on the ipsilateral carotid artery. The headaches tend to become less severe and less frequent over time, with or without effective therapy.

TEMPORAL ARTERITIS (GIANT CELL ARTERITIS; CRANIAL ARTERITIS)

Temporal arteritis is a multifocal vasculitis of cranial arteries, especially the superficial temporal artery. Its cause remains unknown, but autoimmunity to the elastic lamina of the artery has been proposed. The disease most often affects head and neck vessels, but it is considered to be a systemic problem. There may be a genetic predisposition.

The annual incidence rate of temporal arteritis in the United States is approximately 6 per 100,000 population. Incidence rises with age and has been increasing over time, perhaps because the population is aging. There is a strong predilection for whites.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Women are affected by temporal arteritis somewhat more often than men, and patients are usually older than 50 years of age at the time of diagnosis (average age, 70 years). The disease is most frequently a unilateral, throbbing headache that is gradually replaced by an intense, aching, burning temporal and facial pain. The throbbing frequently coincides with the patient’s heartbeat (systole), and the pain may be lancinating. The superficial temporal artery is exquisitely sensitive to palpation and eventually appears erythematous, swollen, tortuous, or rarely ulcerated.

Most patients complain of pain during mastication (jaw claudication) or with the wearing of hats (pressure over the artery). The pain occasionally mimics toothache or a neuralgic jaw or tongue pain. Significantly, ocular symptoms, such as loss of vision or retro-orbital pain, may be the first complaint. Prompt recognition of signs and symptoms of temporal arteritis is important because it is a preventable cause of blindness. The blindness is caused by involvement of the posterior ciliary artery supplying the optic disc, which results in ischemic papillopathy. The visual loss may be transient or permanent, unilateral or bilateral.

Fever, malaise, fatigue, nausea, anorexia, vomiting, sore throat, and earache often occur, perhaps as prodromal symptoms, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate is usually elevated. A generalized muscle aching and stiffness (polymyalgia rheumatica) frequently follow an acute attack. Because muscle and joint aches are quite common in older adults, the potential exists for missed opportunities in the diagnosis and management of temporal arteritis.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Biopsy confirms the diagnosis of temporal arteritis. Microscopic changes tend to be segmental and can be missed if the specimen is too small. At least 1 cm of the affected vessel must, therefore, be examined for proper evaluation.

The disease is characterized by chronic inflammation of the tunica intima and tunica media of the involved artery, with narrowing of the lumen from edema and proliferation of the tunica intima. Necrosis of the smooth muscle and elastic lamina is frequent. A variable number of foreign body-type multinucleated giant cells are mixed with macrophages, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Thrombosis or complete occlusion of the lumen is not unusual.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Temporal arteritis responds well to systemic and local corticosteroids; the symptoms subside within a few days. However, many cases are chronic and need treatment for years. In addition, permanent loss of vision occurs in more than 50% of untreated patients (and even in the occasional patient refractory to treatment). With some individuals, vascular involvement is so widespread throughout the body that the disease is fatal, even with aggressive corticosteroid therapy.

MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease that affects the acetylcholine receptors (AChR) of muscle fibers and results in an abnormal and progressive fatigability of skeletal muscle. Defective neuromuscular transmission occurs, probably secondary to the coating of the AChRs by circulating antibodies to those receptors. Such antibodies are not normally found in humans; hence, the measurement of serum AChR antibody levels is an important diagnostic tool for this disease. The motor end plate itself is normal, and smooth and cardiac muscles are not affected.

Many patients demonstrate either thymus hyperplasia or an actual neoplasm (thymoma) of the thymus gland. Conversely, 75% of patients with thymoma have myasthenia gravis, and 90% have circulating AChR antibodies. The infant of an affected mother may be affected for several weeks or months by maternal antibodies that traverse the placenta. Almost half of the patients with myasthenia gravis have at least one additional autoimmune disorder, especially of the thyroid gland. Each year 1 person in every 100,000 is diagnosed with myasthenia gravis.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Myasthenia gravis is more common in females (1:2 male-to-female ratio). It can begin at any age, and congenital cases have been reported. The disease appears as a subtle but progressive muscle weakness that is most frequently noticed first in the small muscles of the head and neck (Box 18-7).

Repeated muscle contractions, in particular, lead to progressively less power in the contracting muscle; hence, affected patients usually become weaker as the day progresses. The muscles of mastication may become so weak from eating a single meal that the jaws literally “hang open.” Bite force is especially weak when circulating AChR antibody titers are high. Lateral tongue forces exerted during swallowing, speech, and mastication, are reduced significantly in a number of patients.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of myasthenia gravis is based on the clinical symptoms, an elevated serum AChR antibody level, and improved strength after intravenous (IV) injection of edrophonium, a cholinesterase inhibitor. Degenerated muscle fibers are the only characteristic histopathologic feature, with fibers appearing much smaller than normal (hypotrophy, atrophy), having fewer nuclei, and showing a loss of the normal rounded cross-sectional appearance.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The prognosis for myasthenia gravis is usually good. Spontaneous remission sometimes occurs, and approximately 10% of patients never have more than weak eye muscles. Unfortunately, more severe cases often pro-gress, after months or years, to permanent muscular weakness and wasting of the neck, limbs, and trunk. Respiratory paralysis is sometimes a fatal complication.

The defective neuromuscular transmission can be reversed partially by cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., edrophonium, neostigmine), often in combination with intermittent corticosteroid therapy. For patients with evidence of thymoma or with elevated AChR antibody titers, thymectomy is recommended. Complete, permanent recovery often results from thymectomy and, to a lesser extent, from medical therapy.

MOTOR NEURON DISEASE (PROGRESSIVE MUSCULAR ATROPHY; PROGRESSIVE BULBAR PALSY; AMYOTROPHIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS)

First described by Charcot in the 1870s, motor neuron disease is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder that is characterized by progressive weakness and wasting of muscles. The basic defect is progressive degeneration and death of the motor neurons of the cranial nerves, the anterior horn of the spinal cord, and the pyramidal tract.

There are three distinct clinical syndromes with considerable overlapping of signs and symptoms:

Confusion exists over the appropriate terminology, because some authors have used ALS to include all three disease syndromes. Including all subtypes, new cases of motor neuron disease are diagnosed in 15 of every 100,000 persons each year.

Many cases appear to be genetic defects associated with mRNA processing. Progressive muscular atrophy is, for example, the most common autosomal recessive disorder (mutated SMN gene on chromosome 5q) lethal to infants; it now can be identified with a prenatal test for the involved gene. Likewise, up to 10% of cases of ALS are inherited as an autosomal dominant trait (mutated superoxide dismutase-1 gene on chromosome 21). Proposed causes for the nonhereditary cases include toxic accumulation of the neurotransmitter glutamate, trauma, and slow viruses, especially the poliovirus.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Progressive muscular atrophy occurs in childhood. Most cases occur at birth or within the first few months of life, although adult onset is rarely seen. Males and females are affected equally. There is progressive limb weakness and sensory disturbances, which result in difficulty in walking, leg pain, paresthesia, and atrophy of the feet and hands. Facial muscles are spared.

Progressive bulbar palsy typically affects children and young adults and has no gender predilection. It usually begins with a subtle but progressive difficulty in speaking or swallowing (dysphagia). Attempts to swallow food produce bouts of choking and regurgitation, with liquids frequently thrown into the nasopharynx and nasal sinuses because of palatal paralysis. Chronic hoarseness may develop. Atrophy of the facial muscles, tongue, and soft palate eventually occurs, as do weakness and spasticity of the limbs. There are no altered sensory perceptions.

ALS (commonly called Lou Gehrig disease, named after the professional baseball player who died of the disease) affects males more frequently than females and begins to manifest itself in middle age (the average age of onset is 59 years). The disease begins with difficulty in walking because of bilateral, generalized leg stiffness. Occasionally, one leg is affected more than the other, forcing the patient to drag it behind the other. Swallowing difficulty develops early in 29% of cases.

The physical examination in ALS reveals spastic quadriparesis, often with a remarkable increase in the tendon reflexes of all four limbs and with extensor plantar responses. Small, synchronous, subcutaneous muscle contractions (fasciculation) of the shoulders and thighs are an early symptom, with muscle atrophy eventually developing at affected sites. Central reflexes, such as those of the abdomen, are not altered until late in the disease, and there are no changes in sense perception. Dysfunction of the muscles controlled by the medulla oblongata (bulbar paralysis) appears late in the disease, predominantly as spasticity and weakness. Patients become completely disabled, often requiring respiratory support and gastrostomy.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Although each of these conditions may have temporary remissions, the course of motor neuron disease is invariably fatal. Progressive muscular atrophy and progressive bulbar palsy almost always result in death within 2 years, usually from respiratory distress caused by weak intercostal muscles.

ALS usually results in death within 5 years of diagnosis, most often from respiratory failure or cachexia, although 20% of patients survive more than 10 years without ventilator use. The antiglutamate agent, riluzole, has shown some promise in slowing the progression of ALS and improving the morbidity in patients with disease of bulbar onset, but in general there is no cure at this time. Palliative and rehabilitative strategies are used to ease suffering.

BURNING MOUTH SYNDROME (STOMATOPYROSIS; STOMATODYNIA; GLOSSOPYROSIS; GLOSSODYNIA; BURNING TONGUE SYNDROME)

Burning mouth syndrome is a common dysesthesia (i.e., distortion of a sense) typically described by the patient as a burning sensation of the oral mucosa in the absence of clinically apparent mucosal alterations. Although the tongue is most commonly affected (glossopyrosis), other mucosal surfaces may be symptomatic (stomatopyrosis). In addition to the burning sensation, some patients also experience mucosal pain that is often described as “rawness” (stomatodynia, glossodynia). Idiopathic burning and painful sensations (the “dynias”) also can affect the urogenital (vulvodynia) and intestinal mucosa. The so-called scalded mouth syndrome is an apparently unrelated immune response to certain medications, especially angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

Various local and systemic factors have been postulated to cause this condition (Box 18-8), but none have been proven. The fact that most patients are postmenopausal women has led to the common belief that estrogen or progesterone deficit is responsible, but a strong correlation between such deficits and burning tongue syndrome has not been established. Some evidence exists for an autoimmune origin. Abnormal levels of antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and rheumatoid factor (RF), for example, are found in the serum of more than 50% of patients, although these may also be found in older persons without burning mouth syndrome. The disorder has been reported to be strongly associated with depression and anxiety states, leading some authorities to consider it a psychosomatic disease. Well-controlled comparison studies, however, are lacking.

Burning tongue syndrome affects 2% to 3% of adults to some degree (14% of postmenopausal women). Asians and Native Americans have a considerably higher risk than whites or blacks, and there is increasing prevalence with advancing age, especially after 55 years of age. This disorder is one of the most common problems encountered in the clinical practice of oral and maxillofacial pathology.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Women are four to seven times more likely to have burning tongue syndrome than men. The syndrome is rare before the age of 30 years (40 years for men), and the onset in women usually occurs within 3 to 12 years after menopause.

This disorder also has a typically abrupt onset, although it may be quite gradual. The dorsum of the tongue develops a burning sensation, usually strongest in the anterior third. Occasionally, patients will describe an irritated or raw feeling. Mucosal changes are seldom visible, although some patients will show diminished numbers and size of filiform papillae, and individuals who rub the tongue against the teeth often have erythematous and edematous papillae on the tip of the tongue. If the dorsum is significantly erythematous and smooth, an underlying systemic or local infectious process, such as anemia or erythematous candidiasis, should be suspected.

Close questioning often determines that additional oral sites are affected similarly, especially the anterior hard palate and the lips. There is seldom a significant decrease in stimulated salivary output in tests, despite the frequent patient complaint of xerostomia. Salivary levels of various proteins, immunoglobulins, and phosphates may be elevated, and there may be a decreased salivary pH or buffering capacity.

One frequently described pattern is that of mild discomfort on awakening, with increasing intensity throughout the day. Other affected patients describe a waxing and waning pattern that occurs over several days or weeks. Usually the condition does not interfere with sleep. A persistently altered (salty, bitter) or diminished taste may accompany the burning sensation. Contact with hot food or liquid often intensifies the symptoms. A minority describe a constant degree of discomfort.

As with other chronic discomforts, affected pa-tients frequently demonstrate psychologic dysfunction, usually depression, anxiety, or irritability. The dysfunction often disappears, however, with resolution of the burning or painful tongue condition, and there is no correlation between duration and intensity of the burning sensation and the amount of psychologic dysfunction.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: If an underlying systemic or local cause can be identified and corrected, the lingual symptoms should disappear. Almost two thirds of patients with idiopathic disease show at least some improvement of their symptoms when they take one of the mood-altering drugs (e.g., chlordiazepoxide). Additional therapies that have been used include clonazepam, a-lipoic acid (thioctic acid, a neuroprotective drug), amitriptyline, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, analgesics, antibiotics, antifungals, vitamin B complex, and psychologic counseling. However, none of these treatments has been proven to be effective in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

The long-term prognosis for idiopathic burning tongue or mouth syndrome is variable. It is reported that one third to one half of patients experience a spontaneous or gradual remission months or years after the onset of symptoms. However, other patients may continue to experience symptoms throughout the rest of their lives. Even though the condition is chronic and may not always respond to therapy, patients should be reassured that it is benign and not a symptom of oral cancer.

DYSGEUSIA AND HYPOGEUSIA (PHANTOM TASTE; DISTORTED TASTE)

Dysgeusia is defined as a persistent abnormal taste. It is much less common than simple deficiencies in smell (hyposmia, anosmia) and taste (hypogeusia, ageusia) perception, which are found in approximately 2 million adult Americans. Dysgeusia is less tolerated than hypogeusia or hyposmia, explaining why it accounts for more than a third of patients in chemosensory centers.

Most cases of dysgeusia are produced by or associated with an underlying systemic disorder or by radiation therapy to the head and neck region (Box 18-9). Trauma, tumors, or inflammation of the peripheral nerves of the gustatory system usually produce transient hypogeusia rather than dysgeusia. In con-trast, relatively common upper respiratory tract infections produce a temporary and mild dysgeusia in almost one third of cases, although they seldom produce hypogeusia. CNS neoplasms predominantly produce dysgeusia, not hypogeusia or ageusia, and taste hallucinations are fairly common during migraine headaches, Bell’s palsy, or herpes zoster of the geniculate ganglion. Ischemia and infarction of the brainstem can lead to ageusia of only half of the tongue (hemiageusia) on the same side as the brainstem lesion.

The perception of a particular taste depends on its concentration in a liquid environment; hence, persons with severe dry mouth may suffer from both hypogeusia and dysgeusia. In addition, more than 200 drugs are known to produce taste disturbances (Table 18-2). Even without medication-induced alterations, 40% of persons with clinical depression complain of dysgeusia. The clinician should be especially diligent in assessing local, intraoral causes of dysgeusia, such as periodontal or dental abscess, oral candidiasis, and routine gingivitis or periodontitis. The latter may produce a salty taste because of the high sodium chloride content of oozing crevicular fluids.

Table 18-2

Examples of Pharmaceutical Agents That May Be Associated with Altered Taste

| Pharmaceutical Action | Examples |

| Anticoagulant | Phenindione |

| Antihistamine | Chlorpheniramine maleate |

| Antihypertensive or diuretic | Captopril, diazoxide, ethacrynic acid |

| Antimicrobial | Amphotericin B, ampicillin, griseofulvin, idoxuridine, lincomycin, metronidazole, streptomycin, tetracycline, tyrothricin |

| Antineoplastic or immunosuppressant | Doxorubicin, methotrexate, vincristine, azathioprine, carmustine |

| Antiparkinsonian agent | Baclofen, chlormezanone, levodopa |

| Antipsychotic or anticonvulsant | Carbamazepine, lithium, phenytoin |

| Antirheumatic | Allopurinol, colchicine, gold, levamisole, penicillamine, phenylbutazone |

| Antiseptic | Hexetidine, chlorhexidine |

| Antithyroid agent | Carbimazole, methimazole, thiouracil |

| Hypoglycemic | Glipizide, phenformin |

| Opiate | Codeine, morphine |

| Sympathomimetic | Amphetamines, phenmetrazine |

| Vasodilator | Oxyfedrine, bamifylline |

CLINICAL FEATURES: In contrast to hypogeusia, dysgeusia is discerned promptly and distressingly by affected individuals. The clinician must be certain that the patient’s alteration is, in fact, a taste disorder rather than an olfactory one, because 75% of “flavor” information (e.g., taste, aroma, texture, temperature, irritating properties) is derived from smell. Abnormal taste function should be verified through formal taste testing by using standard tastants that are representative of each of the four primary taste qualities (i.e., sweet, sour, salty, bitter) in a nonodorous solution. Additional electrical and chemical analysis of taste bud function is frequently required. Because this is outside the scope of most general practices, patients are typically referred to a taste and smell center.

Affected patients may describe their altered taste as one of the primary ones, but many describe the new taste as metallic, foul, or rancid. The latter two are more likely to be associated with aberrant odor perception (parosmia) than with dysgeusia. The altered taste may require a stimulus, such as certain foods or liquids, in which case the taste is said to be distorted. If no stimulus is required, then the dysgeusia is classified as a phantom taste.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: If an underlying disease or process is identified and treated successfully, the taste function should return to normal. For idiopathic cases there is no effective pharmacologic or surgical therapy. Dysgeusia in particular tends to affect lifestyles and interpersonal relationships significantly, perhaps leading to depression, anxiety, or nutritional deficiencies from altered eating habits. Fortunately, two thirds of dysgeusia patients experience spontaneous resolution (average duration, 10 months). Idiopathic hypogeusia is less of a problem for the patient, but tends to slowly become worse over time. Occasionally, even this will undergo spontaneous resolution.

FREY SYNDROME (AURICULOTEMPORAL SYNDROME; GUSTATORY SWEATING AND FLUSHING)

First described by Baillarger in 1853, Frey syndrome is characterized by facial flushing and sweating along the distribution of the auriculotemporal nerve. These signs occur in response to gustatory stimuli, and the syndrome results from injury to the nerve.

This nerve, in addition to supplying sensory fibers to the preauricular and temporal regions, carries parasympathetic fibers to the parotid gland and sympathetic vasomotor and sudomotor (sweat stimulating) fibers to the preauricular skin. After parotid abscess, trauma, mandibular surgery, or parotidectomy, the parasympathetic nerve fibers may be severed. In their attempt to reestablish innervation, these fibers occasionally become misdirected and regenerate along the sympathetic nerve pathways, establishing communication with the sympathetic nerve fibers of sweat glands and blood vessels of the facial skin. The most widely accepted mechanism of Frey’s syndrome is aberrant neuronal regeneration. Subsequent to these aberrant neural connections, when salivation is stimulated, local sweat glands are activated inadvertently and the patient’s cheek becomes flushed and moist.

More than 40% of patients with parotidectomies develop Frey syndrome as a complication of surgery. The condition is rare in infancy but has been seen after forceps delivery. Neonatal cases do not typically occur until the child begins to eat solid foods, at which time it is usually interpreted as an allergy. Additionally, more than one third of diabetics with neuropathy will experience gustatory sweating, especially those who also have severe kidney damage. The nerve damage in this case is presumably from chronic ischemia and immune attacks.

Related phenomena may accompany an operation or injury to the submandibular gland (chorda tympani syndrome) or the facial nerve proximal to the geniculate ganglion (gustatory lacrimation syndrome, “crocodile tears”). The chin and submental skin demonstrate sweating and flushing in the former. Chewing food in the latter syndrome produces abundant tear formation.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The presenting signs and symptoms of Frey syndrome include sweating, flushing, warmth, and occasionally pain in the preauricular and temporal regions during chewing. Within 2 months to 2 years (average, 9 months) after the nerve injury, the sweating and flushing reactions commence and become steadily more severe for several months, remaining constant thereafter. When flushing occurs, the local skin temperature may be raised as much as 2° C. This may occur without sweating, especially in females. Pain, when present, is usually mild, and hypesthesia (hypoesthesia) or hyperesthesia are common features.

To detect sweating, Minor’s starch-iodine test may be used. A 1% iodine solution is painted on the affected area of the skin. This solution is allowed to dry, and the area is then coated with a layer of starch. When the patient is given something to eat, the moisture of the sweat that is produced will mix with the iodine on the skin. This allows the iodine to react with the starch and produce a blue color (Fig. 18-6). Iodine-sublimated paper, which changes color when wet, also can be used, and thermography or surface thermometers will document the temperature changes of the skin.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Most cases are mild enough that treatment is not required. Moreover, approximately 5% of adult patients and almost all affected infants experience spontaneous resolution of the syndrome. About 5% of Frey syndrome patients with diabetically damaged kidneys will show considerable improvement or complete resolution of the facial problem after renal transplant.

Severing the auriculotemporal or glossopharyngeal nerve on the affected side inhibits or abolishes the sweating and flushing reaction of auriculotemporal syndrome, as may atropine injections, botulinum toxin injections, scopolamine creams, and the systemic use of oxybutynin chloride, an antimuscarinic agent. The risk of this syndrome is greatly diminished by positioning a temporoparietal fascia flap between the gland and the overlying skin of the cheek at the time of parotidectomy.

OSTEOARTHRITIS (DEGENERATIVE ARTHRITIS; DEGENERATIVE JOINT DISEASE)

Osteoarthritis is a common degenerative and destructive alteration of the joints that until recently was considered to be the inevitable result of simple wear and tear on aging anatomic structures. It is now known to have a strong inflammatory component as well, especially in small joints, such as the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), where there appears to be little association with the aging process. The disease represents approximately 10% of patients evaluated for TMJ pain.

Osteoarthritis is thought by some to be unavoidable; almost everyone older than 50 years of age is affected to some extent. The TMJ is less affected than the heavy weight-bearing joints, but even that joint is involved at the microscopic level in 40% of older adults and at the radiographic level in 14%. Although osteoarthritis is definitely an aging phenomenon, recent research also has identified osteoarthritis in a majority of young persons referred to a TMJ clinic for joint pain and dysfunction.

Presumably, with advancing age, there is slower and less complete replacement of chondroblasts and chondrocytes in joint cartilage. The cartilage matrix (fibrocartilage in the case of the TMJ) turns over less rapidly, forcing available fibers to work longer and become susceptible to fatigue. The matrix also holds less water, becoming desiccated and brittle, in part because underlying marrow blood flow diminishes, providing poor nutrition. With continued joint use, the surface fibers break down and portions of the hyaline or fibrocartilage are destroyed, often breaking away to expose underlying bone. The exposed bone then undergoes a dual process of degenerative destruction and proliferation.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Osteoarthritis usually involves multiple joints, typically the large weight-bearing joints. The disease is characterized by a gradually intensifying deep ache and pain, usually worse in the evening than in the morning. Some degree of morning joint stiffness and stiffness after inactivity is present in 80% of cases. The affected joint may become swollen and warm to the touch, rarely with erythema of the overlying skin. Degenerative changes occur in areas of greatest impact, and the joint may become so deformed that it limits motion. Crepitation (i.e., crackling noise during motion) is a late sign of the disease and is, therefore, associated with more pronounced damage.

These changes are seen also when the TMJ is affected, except that patients seldom experience stiffness of the TMJ. In addition, the muscles of mastication frequently exhibit tenderness because of the constant strain of “muscle guarding” (i.e., attempting to keep the painful joint immobile).

On radiography, joints affected by osteoarthritis demonstrate a narrowing or obliteration of the joint space, surface irregularities and protuberances (exostoses, osteophytes), flattening of the articular surface, osteosclerosis and osteolysis of bone beneath the cartilage, radiolucent subchondral cysts, and ossification within the synovial membrane (ossicles). More sensitive diagnostic techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) scanning arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and arthroscopy, reveal the same features but in much more detail; hence, they are able to identify earlier changes. With arthroscopy, 90% of the joints will show evidence of synovitis, usually before cartilage surface changes are visible.