Viral Infections

HUMAN HERPES VIRUSES

The term herpes comes from the ancient Greek word meaning to creep or crawl. The human herpesvirus (HHV) family is officially known as Herpetoviridae, and its best-known member is herpes simplex virus (HSV), a DNA virus. Two types of HSV are known to exist: type I (HSV-1 or HHV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2 or HHV-2). Other members of the HHV family include varicella-zoster virus (VZV or HHV-3), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV or HHV-4), cytomegalovirus (CMV or HHV-5), and several more recently discovered members, HHV-6, HHV-7, and HHV-8.

Humans are the only natural reservoir for these viruses, which are endemic worldwide and share many features. All eight types cause a primary infection and remain latent within specific cell types for the life of the individual. On reactivation, these viruses are associated with recurrent infections that may be symptomatic or asymptomatic. The viruses are shed in the saliva or genital secretions, providing an avenue for infection of new hosts. Each type is known to transform cells in tissue culture, with several strongly associated with specific malignancies. Of the various types, the following sections will concentrate on the herpes simplex viruses, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus. Much less is known about herpesvirus types 6, 7, and 8.

Human herpesviruses 6 and 7 (HHV-6, HHV-7) are closely related, commonly isolated from saliva, usually transmitted by respiratory droplets, and exhibit a prevalence rate of infection close to 90% by age 5 in the United States. Both viruses are associated with a primary infection that usually is asymptomatic but can exhibit an erythematous macular eruption that may demonstrate intermixed slightly elevated papules. The cutaneous manifestation of HHV-6 creates a specific pattern, roseola (exanthema subitum), whereas HHV-7 may cause a similar roseola-like cutaneous eruption. The primary latency resides in CD4 T lymphocytes, and reactivation occurs most frequently in immunocompromised patients. Recurrences can result in widespread multiorgan infection, including encephalitis, pneumonitis, bone-marrow suppression, and hepatitis.

Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) appears to be involved in the pathogenesis of Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) (see page 557) and has been termed Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV). In patients with normal immune systems, primary infection usually is asymptomatic, with sexual contact (especially male homosexual) being the most common pattern of transmission. The virus has been found without difficulty in saliva, suggesting another possible pattern of transmission. Associated symptoms such as transient fever, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgias are rarely reported. Circulating B lymphocytes appear to be the major cell of latency. In addition to Kaposi’s sarcoma, HHV-8 also has been associated with a small variety of lymphomas and Castleman’s disease.

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS

The two herpes simplex viruses are similar structurally but different antigenically. In addition, the two exhibit epidemiologic variations.

HSV-1 is spread predominantly through infected saliva or active perioral lesions. HSV-1 is adapted best and performs more efficiently in the oral, facial, and ocular areas. The pharynx, intraoral sites, lips, eyes, and skin above the waist are involved most frequently.

HSV-2 is adapted best to the genital zones, is transmitted predominantly through sexual contact, and typically involves the genitalia and skin below the waist. Exceptions to these rules do occur, and HSV-1 can be seen in a pattern similar to that of HSV-2 and vice versa. The clinical lesions produced by both types are identical, and both produce the same changes in tissue. The viruses are so similar that antibodies directed against one cross-react against the other. Antibodies to one of the types decrease the chance of infection with the other type; if infection does occur, the manifestations often are less severe.

Clinically evident infections with HSV-1 exhibit two patterns. The initial exposure to an individual without antibodies to the virus is called the primary infection. This typically occurs at a young age, often is asymptomatic, and usually does not cause significant morbidity. At this point, the virus is taken up by the sensory nerves and transported to the associated sensory or, less frequently, the autonomic ganglia where the virus remains in a latent state. With HSV-1 infection, the most frequent site of latency is the trigeminal ganglion, but other possible sites include the nodose ganglion of the vagus nerve, dorsal root ganglia, and the brain. The virus uses the axons of the sensory neurons to travel back and forth to the peripheral skin or mucosa.

Secondary, recurrent, or recrudescent HSV-1 infection occurs with reactivation of the virus, although many patients may show only asymptomatic viral shedding in the saliva. Symptomatic recurrences are fairly common and affect the epithelium supplied by the sensory ganglion. Spread to an uninfected host can occur easily during periods of asymptomatic viral shedding or from symptomatic active lesions. When repeatedly tested, approximately one third of individuals with HSV-1 antibodies occasionally shed infectious viral particles, even without active lesions being present. In addition, the virus may spread to other sites in the same host to establish residency at the sensory ganglion of the new location. Numerous conditions such as old age, ultraviolet light, physical or emotional stress, fatigue, heat, cold, pregnancy, allergy, trauma, dental therapy, respiratory illnesses, fever, menstruation, systemic diseases, or malignancy have been associated with reactivation of the virus, but only ultraviolet light exposure has been demonstrated unequivocally to induce lesions experimentally. More than 80% of the primary infections are purported to be asymptomatic, and reactivation with asymptomatic viral shedding greatly exceeds clinically evident recurrences.

HSV does not survive long in the external environment, and almost all primary infections occur from contact with an infected person who is releasing the virus. The usual incubation period is 3 to 9 days. Because HSV-1 usually is acquired from contact with contaminated saliva or active perioral lesions, crowding and poor hygiene promote exposure. Lower socioeconomic status correlates with earlier exposure. In developing countries, more than 50% of the population is exposed by 5 years of age, 95% by 15 years of age, and almost universal exposure by 30 years of age. On the other hand, upper socioeconomic groups in developed nations exhibit less than 20% exposure at 5 years of age and only 50% to 60% in adulthood. Regardless of the socioeconomic group, prevalence tends to increase with age, and many investigators report a frequency of prior infection that approaches 90% of the population by age 60. The low childhood exposure rate in the privileged groups is followed by a second peak during the college years of life. The age of initial infection also affects the clinical presentation of the symptomatic primary infections. In symptomatic cases, individuals exposed to HSV-1 at an early age tend to exhibit gingivostomatitis; those initially exposed later in life often demonstrate pharyngotonsillitis.

As mentioned previously, antibodies to HSV-1 decrease the chance of infection with HSV-2 or lessen the severity of the clinical manifestations. The dramatic increase recently seen in HSV-2 is due partly to lack of prior exposure to HSV-1, increased sexual activity, and lack of barrier contraception. HSV-2 exposure correlates directly with sexual activity. Exposure of those younger than age 14 is close to zero, and most initial infections occur between the ages of 15 and 35. The prevalence varies from near zero in celibate adults to more than 80% in prostitutes. Because many of those infected with HSV-2 refrain from sexual activity when active lesions are present, many investigators believe that at least 70% of primary infections are contracted from individuals during asymptomatic viral shedding.

In addition to clinically evident infections, HSV has been implicated in a number of noninfectious processes. More than 15% of cases of erythema multiforme are preceded by a symptomatic recurrence of HSV 3 to 10 days earlier (see page 776), and some investigators believe that up to 60% of mucosal erythema multiforme may be triggered by HSV. In some instances, the attacks of erythema multiforme are frequent enough to warrant antiviral prophylaxis. An association with cluster headaches and a number of cranial neuropathies has been proposed, but definitive proof is lacking.

On rare occasions, asymptomatic release of HSV will coincide with attacks of aphthous ulcerations. The ulcerations are not infected with the virus. In these rare cases, the virus may be responsible for the initiation of the autoimmune destruction; conversely, the immune dysregulation that produces aphthae may have allowed the release of the virions. In support of the lack of association between HSV and aphthae in the general population of patients with aphthous ulcerations, prophylactic oral acyclovir does not decrease the recurrence rate of the aphthous ulcerations. Although the association between HSV and recurrent aphthous ulcerations is weak, it may be important in small subsets of patients (see page 331).

HSV also has been associated with oral carcinomas, but much of the evidence is circumstantial. The DNA from HSV has been extracted from the tissues of some tumors but not from others. HSV may aid carcinogenesis through the promotion of mutations, but the oncogenic role, if any, is uncertain.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis (primary herpes) is the most common pattern of symptomatic primary HSV infection, and more than 90% are the result of HSV-1. In a study of more than 4000 children with antibodies to HSV-1, Jureti found that only 12% of those infected had clinical symptoms and signs severe enough to be remembered by the affected children or their parents. Some health care practitioners suspect that the percentage of primary infections that exhibit clinical symptoms is much higher, whereas others believe the prevalence is lower. Many primary infections may manifest as pharyngitis that mimics the pattern seen in common colds. Further studies are needed to fully answer this question.

found that only 12% of those infected had clinical symptoms and signs severe enough to be remembered by the affected children or their parents. Some health care practitioners suspect that the percentage of primary infections that exhibit clinical symptoms is much higher, whereas others believe the prevalence is lower. Many primary infections may manifest as pharyngitis that mimics the pattern seen in common colds. Further studies are needed to fully answer this question.

Most cases of acute herpetic gingivostomatitis arise between the ages of 6 months and 5 years, with the peak prevalence occurring between 2 and 3 years of age. In spite of these statistics, occasional cases have been reported in patients over 60 years of age. Development before 6 months of age is rare because of protection by maternal anti-HSV antibodies. The onset is abrupt and often accompanied by anterior cervical lymphadenopathy, chills, fever (103° to 105° F), nausea, anorexia, irritability, and sore mouth lesions. The manifestations vary from mild to severely debilitating.

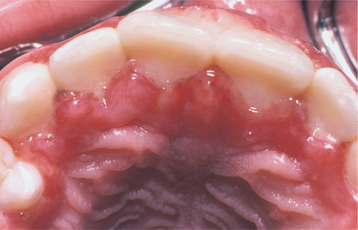

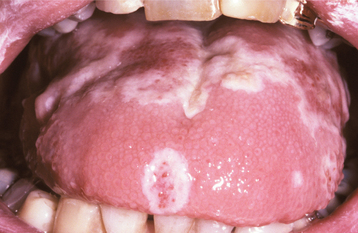

Initially the affected mucosa develops numerous pinhead vesicles, which rapidly collapse to form numerous small, red lesions. These initial lesions enlarge slightly and develop central areas of ulceration, which are covered by yellow fibrin (Fig. 7-1). Adjacent ulcerations may coalesce to form larger, shallow, irregular ulcerations (Fig. 7-2). Both the movable and attached oral mucosa can be affected, and the number of lesions is highly variable. In all cases the gingiva is enlarged, painful, and extremely erythematous (Fig. 7-3). In addition, the affected gingiva often exhibits distinctive punched-out erosions along the midfacial free gingival margins (Fig. 7-4). It is not unusual for the involvement of the labial mucosa to extend past the wet line to include the adjacent vermilion border of the lips. Satellite vesicles of the perioral skin are fairly common. Self-inoculation of the fingers, eyes, and genital areas can occur. Mild cases usually resolve within 5 to 7 days; severe cases may extend to 2 weeks. Rare complications include keratoconjunctivitis, esophagitis, pneumonitis, meningitis, and encephalitis.

Fig. 7-1 Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis. Widespread yellowish mucosal ulcerations. (Courtesy of Dr. David Johnsen.)

Fig. 7-2 Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis. Numerous coalescing, irregular, and yellowish ulcerations of the dorsal surface of the tongue.

Fig. 7-4 Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis. Painful, enlarged, and erythematous facial gingiva. Note erosions of the free gingival margin.

As mentioned previously, when the primary infection occurs in adults, some symptomatic cases exhibit pharyngotonsillitis. Sore throat, fever, malaise, and headache are the initial symptoms. Numerous small vesicles develop on the tonsils and posterior pharynx. The vesicles rapidly rupture to form numerous shallow ulcerations, which often coalesce with one another. A diffuse, gray-yellow exudate forms over the ulcers in many cases. Involvement of the oral mucosa anterior to Waldeyer’s ring occurs in less than 10% of these cases. HSV appears to be a significant cause of pharyngotonsillitis in young adults who are from the higher socioeconomic groups with previously negative test findings for HSV antibodies. Most of these infections are HSV-1, but increasing proportions are HSV-2. The clinical presentation closely resembles pharyngitis secondary to streptococci or infectious mononucleosis, making the true frequency difficult to determine.

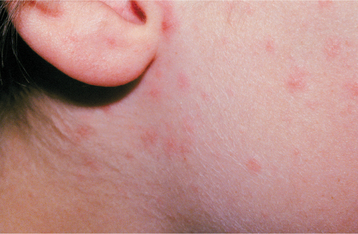

Recurrent herpes simplex infections (secondary herpes, recrudescent herpes) may occur either at the site of primary inoculation or in adjacent areas of surface epithelium supplied by the involved ganglion. The most common site of recurrence for HSV-1 is the vermilion border and adjacent skin of the lips. This is known as herpes labialis (“cold sore” or “fever blister”). Prevalence studies suggest that from 15% to 45% of the United States population have a history of herpes labialis. In some patients, ultraviolet light or trauma can trigger recurrences. Prodromal signs and symptoms (e.g., pain, burning, itching, tingling, localized warmth, erythema of the involved epithelium) arise 6 to 24 hours before the lesions develop. Multiple small, erythematous papules develop and form clusters of fluid-filled vesicles (Fig. 7-5). The vesicles rupture and crust within 2 days. Healing usually occurs within 7 to 10 days. Symptoms are most severe in the first 8 hours, and most active viral replication is complete within 48 hours. Mechanical rupture of intact vesicles and the release of the virus-filled fluid may result in the spreading of the lesions on lips previously cracked from sun exposure (Fig. 7-6). Recurrences are observed less commonly on the skin of the nose, chin, or cheek. The majority of those affected experience approximately 2 recurrences annually, but a small percentage may experience outbreaks that occur monthly or even more frequently.

Fig. 7-6 Herpes labialis. Multiple sites of recurrent herpetic infection secondary to spread of viral fluid over cracked lips.

On occasion, some lesions arise almost immediately after a known trigger and appear without any preceding prodromal symptoms. These rapidly developing recurrences tend to respond less favorably to treatment.

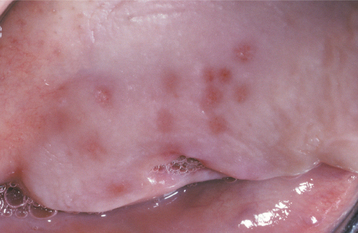

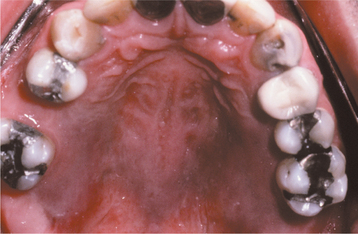

Recurrences also can affect the oral mucosa. In the immunocompetent patient, involvement is limited almost always to keratinized mucosa that is bound to bone (attached gingiva and hard palate). These sites often exhibit subtle changes, and the symptoms are less intense. The lesions begin as 1- to 3-mm vesicles that rapidly collapse to form a cluster of erythematous macules that may coalesce or slightly enlarge (Figs. 7-7 and 7-8). The damaged epithelium is lost, and a central yellowish area of ulceration develops. Healing takes place within 7 to 10 days.

Fig. 7-7 Intraoral recurrent herpetic infection. Early lesions exhibiting as multiple erythematous macules on the hard palate. Lesions appeared a few days after extraction of a tooth.

Fig. 7-8 Intraoral recurrent herpetic infection. Multiple coalescing ulcerations on the hard palate.

Less common presentations of HSV-1 do occur. Infection of the thumbs or fingers is known as herpetic whitlow (herpetic paronychia), which may occur as a result of self-inoculation in children with orofacial herpes (Fig. 7-9). Before the uniform use of gloves, medical and dental personnel could infect their digits from contact with infected patients, and they were the most likely group affected by this form of HSV-I infection. Recurrences on the digits are not unusual and may result in paresthesia and permanent scarring.

Cutaneous herpetic infections also can arise in areas of previous epithelial damage. Parents kissing areas of dermatologic injury in children represent one vector. Wrestlers and rugby players also may contaminate areas of abrasion, a lesion called herpes gladiatorum or scrumpox. On occasion, herpes simplex has been spread over the bearded region of the face into the minor injuries created by daily shaving, leading to a condition known as herpes barbae (barbae is Latin for “of the beard”). Ocular involvement may occur in children, often resulting from self-inoculation. Patients with diffuse chronic skin diseases, such as eczema, pemphigus, and Darier’s disease, may develop diffuse life-threatening HSV infection, known as eczema herpeticum (Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption). Newborns may become infected after delivery through a birth canal contaminated with HSV, usually HSV-2. Without treatment, there is greater than a 50% mortality rate.

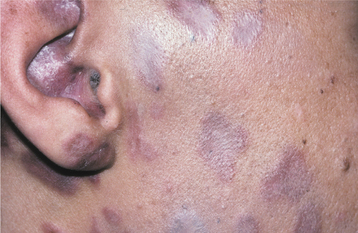

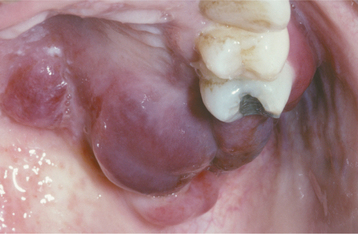

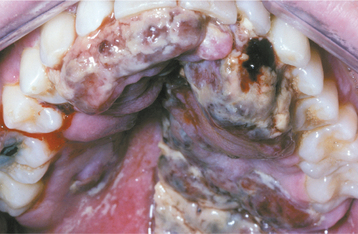

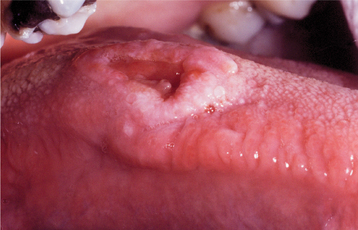

HSV recurrence in immunocompromised hosts can be significant. Without proper immune function, recurrent herpes can persist and spread until the infection is treated with antiviral drugs, until immune status returns, or until the patient dies. On the skin, the lesions continue to enlarge peripherally, with the formation of an increasing zone of superficial cutaneous erosion. Oral mucosa also can be affected and usually is present in conjunction with herpes labialis. Although most oral mucosal involvement begins on the bound mucosa, it often is not confined to these areas. The involved sites begin as areas of necrotic epithelium that are brownish and raised above the surface of the adjacent intact epithelium. Typically, these areas are much larger than the usual pinhead lesions found in immunocompetent patients. With time, the area of involvement spreads laterally. The enlarging lesion is a zone of superficial necrosis or erosion, often with a distinctive circinate, raised, yellow border (Figs. 7-10 and 7-11). This border represents the advancing margin of active viral destruction. Microscopic demonstration of HSV infection in a chronic ulceration on the movable oral mucosa is ominous, and all such patients should be evaluated thoroughly for possible immune dysfunction or underlying occult disease processes.

Fig. 7-10 Chronic herpetic infection. Numerous mucosal erosions, each of which is surrounded by a slightly raised, yellow-white border, in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia.

Fig. 7-11 Chronic herpetic infection. Numerous shallow herpetic erosions with raised, yellow and circinate borders on the maxillary alveolar ridge in an immunocompromised patient.

Although a yellow curvilinear border often is present in many chronic herpetic ulcerations noted in immunocompromised patients, this distinctive feature might be missing. Several authors have reported persistent oral ulcerations in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) that lack the distinctive periphery, often are nonspecific clinically, and may mimic aphthous ulcerations, necrotizing stomatitis, or ulcerative periodontal disease. Biopsy of persistent ulcerations in patients with AIDS is mandatory and may reveal any one of a number of infectious or neoplastic processes. These ulcers may reveal histopathologic evidence of herpesvirus, often combined with diagnostic features of CMV (HHV-5) coinfection (see page 255).

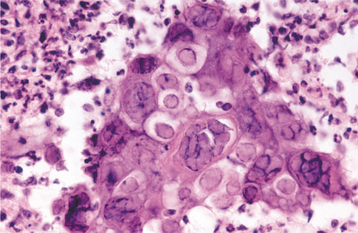

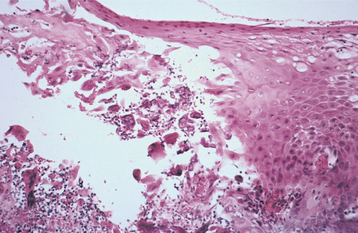

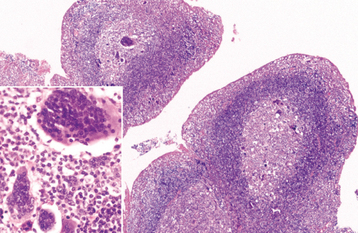

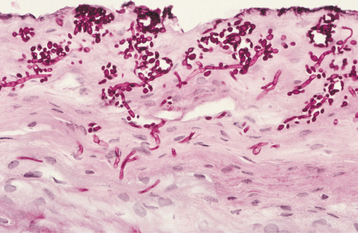

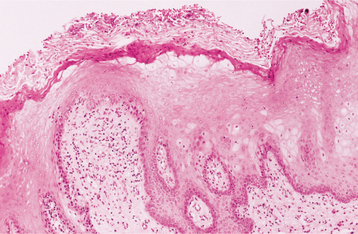

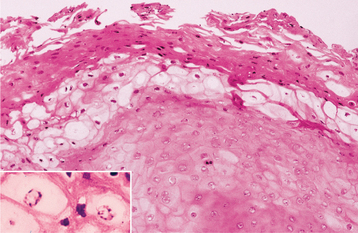

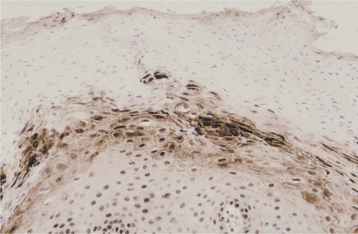

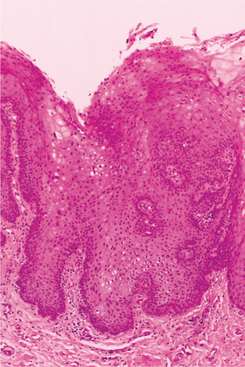

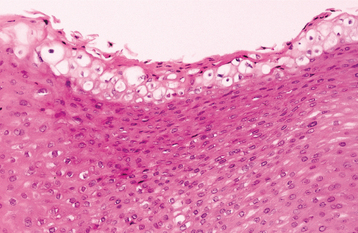

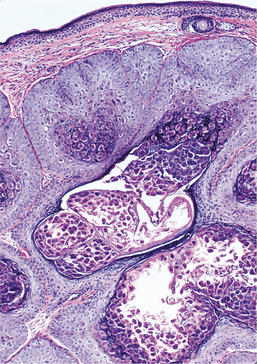

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The virus exerts its main effects on the epithelial cells. Infected epithelial cells exhibit acantholysis, nuclear clearing, and nuclear enlargement, which has been termed ballooning degeneration (Fig. 7-12). The acantholytic epithelial cells are termed Tzanck cells (not specific for herpes; refers to a free-floating epithelial cell in any intraepithelial vesicle). Nucleolar fragmentation occurs with a condensation of chromatin around the periphery of the nucleus. Multinucleated, infected epithelial cells are formed when fusion occurs between adjacent cells (see Fig. 7-12). Intercellular edema develops and leads to the formation of an intraepithelial vesicle (Fig. 7-13). Mucosal vesicles rupture rapidly; those on the skin persist and develop secondary infiltration by inflammatory cells. Once they have ruptured, the mucosal lesions demonstrate a surface fibrinopurulent membrane. Often at the edge of the ulceration or mixed within the fibrinous exudate are the scattered Tzanck or multinucleated epithelial cells.

DIAGNOSIS: With a thorough knowledge of the clinical presentations, the clinician can make a strong presumptive diagnosis of HSV infection. On occasion, HSV infections can be confused with other diseases, and laboratory confirmation is desirable. Viral isolation from tissue culture inoculated with the fluid of intact vesi-cles is the most definitive diagnostic procedure. The problem with this technique in primary infections is that up to 2 weeks can be required for a definitive result. Laboratory tests to detect HSV antigens by direct fluorescent assay or viral DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of specimens of active lesions also are available. Serologic tests for HSV antibodies are positive 4 to 8 days after the initial exposure. Confirmation of primary infection by serology requires a specimen obtained within 3 days of the presentation and a second sample approximately 4 weeks later. In such cases the initial specimen should be negative, with antibodies discovered only in the convalescent sample. These antibody titers are useful in documenting past exposure and are used primarily in epidemiologic studies.

Intact vesicles are rare intraorally. Therefore, using intraoral viral culture as the sole means of diagnostic confirmation of HSV infection is inappropriate. Research has shown that asymptomatic oral HSV shedding occurs in up to 9% of the general population. During periods of mental or physical stress, asymptomatic viral shedding rises to approximately one third of those previously exposed to the virus. In immunocompromised patients, the prevalence rises to 38%; this percentage is low and most likely would double if the investigation were restricted to those previously exposed to the virus. Therefore, culture of lesions contaminated with saliva that might contain coincidentally released HSV is meaningless unless supplemented by additional diagnostic procedures.

Two of the most commonly used diagnostic procedures are the cytologic smear and tissue biopsy, with cytologic study being the least invasive and most cost-effective. The virus produces distinctive histopathologic alterations within the infected epithelium. Only VZV produces similar changes, but these two infections usually can be differentiated on a clinical basis. Fluorescent monoclonal antibody typing can be performed on the direct smears or on infected cells obtained from tissue culture.

If diagnostic features of herpesvirus are discovered in a biopsy of a persistent ulceration in an immunocompromised patient, immunocytochemical studies for CMV also should be performed to rule out coinfection. The histopathologic features of CMV can be missed easily, resulting in patients not receiving the most appropriate therapy.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: In the past, primary herpetic gingivostomatitis was treated best symptomatically; however, if the infection is diagnosed early, antiviral medications can have a significant influence. Patients should be instructed to restrict contact with active lesions to prevent the spread to other sites and people. As mentioned previously, autoinoculation of the eyes can result in ocular involvement with the possibility of recurrence. Repeated ocular reinfection can produce permanent damage and blindness. HSV is the leading infectious cause of blindness in the United States.

When acyclovir suspension is initiated during the first 3 symptomatic days in a rinse-and-swallow technique five times daily for 5 days (children: 15 mg/kg up to the adult dose of 200 mg), significant acceleration in clinical resolution is seen. Once therapy is initiated, development of new lesions ceases. In addition, the associated eating and drinking difficulties, pain, healing time, duration of fever, and viral shedding are shortened dramatically. The use of a topical spray with 0.5% or 1.0% dyclonine hydrochloride also dramatically, but temporarily, decreases the mucosal discomfort. Compounding pharmacists also can provide tetracaine lollipops that can be used for rapid and profound numbing of the affected mucosa. Viscous lidocaine and topical benzocaine should be avoided in pediatric patients because of reports of lidocaine-induced seizures in children and an association between topical benzocaine and methemoglobinemia. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, also help alleviate the discomfort. Use of antiviral medications in capsule or tablet form is much less effective because of the increased time these formulations require to exert a significant effect.

Recurrent herpes labialis has been treated with everything from ether to voodoo; nothing has solved the problem for all patients. Of the antiherpetic medications, acyclovir ointment in polyethylene glycol was the initial formulation available for topical therapy. Acyclovir ointment has been of limited benefit for herpes labialis in immunocompetent patients, because its base is thought to prevent significant absorption. Subsequently, penciclovir cream became available in a base that allows increased absorption through the vermilion border. Use of this formulation has resulted in a statistically significant, although clinically minimal, reduction in healing time and pain (duration decreased approximately 1 day). Although the best results are obtained if use of penciclovir cream is initiated during the prodrome, late application has produced a measurable clinical benefit. Other current choices are acyclovir cream and an over-the-counter formulation of 10% n-docosanol cream. Although acyclovir cream does appear more effective than n-docosanol, both of these therapeutic choices are associated with statistically significant, but clinically minimal, reduction in healing time and pain, but at a lesser degree than that associated with penciclovir cream.

Systemic acyclovir and the two newer related medications, valacyclovir and famciclovir, appear to demonstrate similar effectiveness against HSV. However, valacyclovir and famciclovir exhibit improved bioavailability and more convenient oral dosing schedules. Of the three medications, a dosing schedule with valacyclovir, consisting of an initial 2 g taken on recognition of prodromal symptoms followed by another 2 g 12 hours later, has been most successful in minimizing the recurrences. The effects of this treatment are reduced significantly if it is not initiated during the prodrome. Although much less convenient, 400 mg of acyclovir taken five times daily for 5 days appears to produce similar results. For patients whose recurrences appear to be associated with dental procedures, a regimen of 2 g of valacyclovir taken twice on the day of the procedure and 1 g taken twice the next day may suppress or minimize any associated attack. In individuals with a known trigger that extends over a period of time (e.g., skiing, beach vacation), prophylactic short-term use of one of the antivirals (acyclovir, 400 mg twice a day [b.i.d.]; valacyclovir 1 g daily; or famciclovir 250 mg b.i.d.) has been shown to reduce the prevalence and severity of any associated recurrence.

Most cases of recurrent herpes labialis are infrequent; therefore, rarely can regular use of systemic antiviral medications be justified in immunocompetent individuals. Long-term suppression of recurrences with an antiviral medication is reserved by many for patients with more than six recurrences per year, those suffering from HSV-triggered erythema multiforme, and the immunocompromised. In recent years the emergence of acyclovir-resistant HSV has been seen with increasing frequency. Such resistance has arisen almost exclusively in immunocompromised patients receiving intermittent therapy, and the use of prophylactic therapy does not appear to be associated with emergence of resistant strains. In immunocompromised patients, the viral load tends to be high and replication is not suppressed completely by antiviral therapy, creating the environment for generating drug-resistant mutants. Although resistance is seen primarily in immunocompromised patients, cavalier use of antiviral medications for mild cases of recurrent herpes infection probably is inappropriate.

The pain associated with intraoral secondary herpes usually is not intense, and many patients do not require treatment. Some studies have shown chlorhexidine to exert antiviral effects in vivo and in vitro. In addi-tion, acyclovir appears to function synergistically with chlorhexidine. Extensive clinical trials have not been performed, but chlorhexidine alone or in combination with acyclovir suspension may be beneficial in patients who desire or require therapy of intraoral lesions.

Immunocompromised hosts with HSV infections often require intravenous (IV) antiviral medications to control the problem. Furthermore, severely immunosuppressed individuals, such as bone marrow transplant patients and those with AIDS, often need prophylactic doses of oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. On occasion, viral resistance develops, resulting in the onset of significant herpetic lesions. Any herpes lesions that do not respond to appropriate therapy within 5 to 10 days most likely are the result of resistant strains. At this point the initial antiviral therapy should be repeated at an elevated dose. If this intervention fails, IV trisodium phosphonoformate hexahydrate (foscarnet) is administered. If the infection persists, IV cidofovir is recommended. Another antiviral, adenine arabinoside (vidarabine), is reserved for patients in whom all of the previously described medications have failed. In resistant cases that have been treated successfully, it appears that only the peripheral virus mutates, because future recurrences often are once again sensitive to the first-line antivirals. Ulcerations that reveal coinfection with HSV and CMV respond well to ganciclovir, with foscarnet used in refractory cases.

Although a successful live-virus vaccine has been available for the closely related varicella virus for over 25 years, similar approaches against HSV have produced less satisfactory results. Significant research for a potential vaccine is ongoing and offers hope for the future.

VARICELLA (CHICKENPOX)

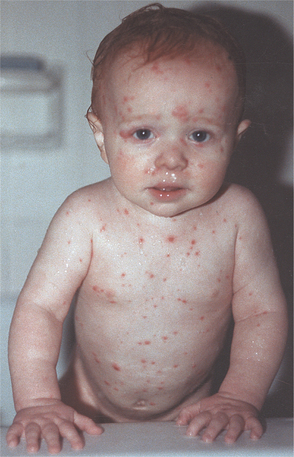

The varicella-zoster virus (VZV, HHV-3) is similar to herpes simplex virus (HSV) in many respects. Chick-enpox represents the primary infection with the VZV; latency ensues, and recurrence is possible as herpes zoster, often after many decades. The virus is presumed to be spread through air droplets or direct contact with active lesions. Most cases of chickenpox arise between the ages of 5 and 9, with greater than 90% of the U.S. population being infected by 15 years of age. In contrast to infection with HSV, most cases are symptomatic. The incubation period is 10 to 21 days, with an average of 15 days.

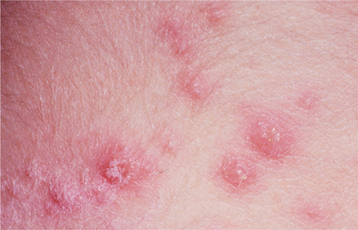

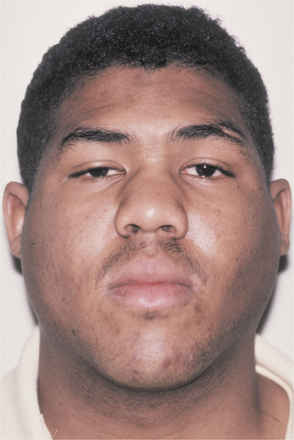

CLINICAL FEATURES: The symptomatic phase of VZV infection usually begins with malaise, pharyngitis, and rhinitis. In older children and adults, additional symptoms (e.g., headache, myalgia, nausea, anorexia, vomiting) occasionally are seen. This is followed by a characteristic, intensely pruritic exanthem. The rash begins on the face and trunk, followed by involvement of the extremities. Each lesion rapidly progresses through stages of erythema, vesicle, pustule, and hardened crust (Figs. 7-14 and 7-15). The early vesicular stage is the classic presentation. The centrally located vesicle is surrounded by a zone of erythema and has been described as “a dewdrop on a rose petal.” In contrast to herpes simplex, the lesions typically continue to erupt for 4 days; in some cases the exanthem’s arrival may extend to 7 or more days. Old crusted lesions intermixed with newly formed and intact vesicles are commonplace. Affected individuals are contagious from 2 days before the exanthem until all the lesions crust. Fever usually is present during the active phase of the exanthem. The severity of the cutaneous involvement is variable and often more severe in adults and in household members secondarily infected by the initial patient.

Fig. 7-14 Varicella. Infant with diffuse erythematous and vesicular rash. (Courtesy of Dr. Sherry Parlanti.)

Perioral and oral manifestations are fairly common and may precede the skin lesions. The vermilion border of the lips and the palate are the most common sites of involvement, followed by the buccal mucosa. Occasionally, gingival lesions resemble those noted in primary HSV infections, but distinguishing between the two is not difficult because the lesions of varicella tend to be relatively painless. The lesions begin as 3- to 4-mm, white, opaque vesicles that rupture to form 1- to 3-mm ulcerations (Fig. 7-16). The prevalence and number of the oral lesions correlate with the severity of the extraoral infection. In mild cases, oral lesions are present in about one third of affected individuals. Often only 1 or 2 oral ulcers are evident, and typically these heal within 1 to 3 days. In contrast, patients with severe infections almost always have oral ulcerations, often numbering up to 30 lesions and persisting for 5 to 10 days. In severe cases of chickenpox, old ruptured lesions will often become intermixed with fresh vesicles.

Complications can occur, with the need for hospitalization in children approximating 1 in 600 in the prevaccine era. Possible complications include Reye’s syndrome, secondary skin infections, encephalitis, cerebellar ataxia, pneumonia, gastrointestinal dis-turbances (e.g., vomiting, diarrhea, associated dehydration), and hematologic events (i.e., thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia, hemolytic anemia, sickle cell crisis).

In childhood the most frequent complications are secondary skin infections, followed by encephalitis and pneumonia. With enhanced public education and decreased use of aspirin in children, the prevalence of Reye’s syndrome is decreasing. Although associated bacterial infections had decreased after the introduction of antibiotics, an increased prevalence of significant complications related to secondary infections caused by group A, b-hemolytic streptococci was seen during the 1990s. These organisms have created life-threatening infections and areas of highly destructive necrotizing fasciitis.

The prevalence of complications in adults exceeds that noted in children. The most common and serious complication is varicella pneumonitis, which features dry cough, tachypnea, dyspnea, hemoptysis, chest pain, and cyanosis. Encephalitis and clinically significant pneumonia are diagnosed in 1 in 375 affected adults older than 20 years of age. The central nervous system (CNS) involvement typically produces ataxia but may result in headaches, drowsiness, convulsions, or coma. The risk of death is reported to be 15 times greater in adults compared with children, mostly because of an increased prevalence of encephalitis.

Infection during pregnancy can produce congenital or neonatal chickenpox. Involvement early in the pregnancy can result in spontaneous abortion or congenital defects. Although complications can occur in newborns, the effects of maternal varicella infection appear minimal. A multicenter prospective study of live births associated with maternal varicella infection revealed only a 1.2% prevalence of embryopathy. However, infection of the mother close to delivery can result in a severe fetal infection caused by a lack of maternal antibodies.

Infection in immunocompromised patients also can be most severe. The cutaneous involvement typically is extensive and may be associated with high fever, hepatitis, pneumonitis, pancreatitis, gastrointestinal obstruction, and encephalitis. Before effective antiviral therapy, the mortality rate in immunocompromised individuals was approximately 7%. Secondary bacterial infections often complicate the process.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The cytologic alterations are virtually identical to those described for HSV. The virus causes acantholysis, with formation of numerous free-floating Tzanck cells, which exhibit nuclear margination of chromatin and occasional multinucleation.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of chickenpox usually can be made from a history of exposure to VZV within the last 3 weeks and the presence of the typical exanthem. Confirmation can be obtained through a demonstration of viral cytopathologic effects present within the epithelial cells harvested from the vesicular fluid. These cytologic changes are identical to those found in herpes simplex, and further confirmation sometimes is desired. Viral isolation in cell culture or rapid diagnosis from fluorescein-conjugated VZV monoclonal antibodies can be performed. Finally, serum samples can be obtained during the acute stage and 14 to 28 days later. The later sample should demonstrate a significant (fourfold) increase in antibody titers to VZV.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Before the current antiviral medications became available, the treatment of varicella primarily was symptomatic. Warm baths with soap or baking soda, application of calamine lotion, and systemic diphenhydramine still are used to relieve pruritus. VZV has a lipid envelope that is destroyed rapidly by soap and other detergents. Lotions with diphenhydramine are not recommended because of reports of toxicity secondary to percutaneous absorption of the medication. Antipyretics other than aspirin should be given to reduce fever.

Use of peroral antiviral medications such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir has been shown to reduce the duration and severity of the infection if it is administered within the first 24 hours of the rash. Routine use of these antiviral medications is not recommended in immunocompetent children with uncomplicated chickenpox. Typically, such therapy is reserved for patients at risk for more severe disease, such as those over 13 years of age and individuals who contract the disease from a family member. Intravenous formulations are used in immunosuppressed patients or those exhibiting a progressive, severe infection. Treatment with one of the available antiviral medications does not alter the antibody response to VZV or reduce immunity later in life.

In patients without evidence of immunity who become exposed to VZV and are at high risk for severe disease or complications, purified varicella-zoster immune globulin can be given to modify the clinical manifestations of the infection. Individuals at risk include immunocompromised patients, pregnant women, premature infants, and neonates whose mothers do not have evidence of immunity. The U.S.-licensed manufacturer of the immune globulin marketed the material under the name VZIG but discontinued production in October 2004. At the time of this writing, the immune globulin is being made by a Canadian company and is known as VariZIG. This product has not completed full U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and is currently classified as an investigational new drug (IND). In an attempt to improve access during this critical period of transition, an expanded access protocol has been approved by a central institutional review board (IRB), with the FDA not requiring additional local IRB approval at the treatment site. VariZIG is most effective if administered within 96 hours of initial exposure. In most instances the material can be delivered from the distributor to the treatment site within 24 hours.

A live attenuated varicella vaccine has been available since 1974 and has been used extensively outside the United States, especially in Japan. In 1995 the vaccine was approved for use in the United States. Before that time, the annual incidence of infection in the United States was approximately 4 million, with an associated 11,000 hospitalizations and 100 deaths. Vaccination is recommended for children between 12 and 18 months of age, as well as for all susceptible individuals over the age of 13. Although the vaccination rates vary by state, the national coverage is approximately 85% and has led to a reduction of reported infection rates that also is around 85%.

During the first year after vaccination, the efficacy appears to be 100% but drops to 95% after 7 years. When breakthrough infections do occur, they usually are very mild. Because of continued exposure to wild virus, previously vaccinated patients have not required boosters to maintain immunity. As the prevalence of the wild virus diminishes, booster vaccines may be required to maintain lifelong immunity. Extensive follow-up of vaccinated groups is ongoing; if antibody levels wane with time, booster immunizations will be recommended. It should be remembered that the vaccine is a live virus that can be spread to individuals in close contact. Vaccine recipients who develop a rash should avoid contact with those at risk, such as immunocompromised or pregnant individuals.

The national health objectives for 2010 included a goal to obtain and maintain ≥95% vaccination coverage among first graders for hepatitis B, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliovirus, measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella. The measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine currently has achieved a 93% vaccination rate, whereas the frequency for the varicella vaccine remains below 90%. Use of a combined measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) vaccine has demonstrated comparable effectiveness and safety. This approach would provide protection via a single injection and have the potential to increase the vaccination rate for varicella more rapidly.

HERPES ZOSTER (SHINGLES)

After the initial infection with VZV (chickenpox), the virus is transported up the sensory nerves and presumably establishes latency in the dorsal spinal ganglia. Clinically evident herpes zoster occurs after reactivation of the virus, with the involvement of the distribution of the affected sensory nerve. Zoster occurs during the lifetime of 10% to 20% of individuals, and the prevalence of attacks increases with age. With the increasing average age of the population, an increased prevalence of herpes zoster is expected. Unlike herpes simplex virus (HSV), single rather than multiple recurrences are the rule. Immunosuppression, HIV-infection, treatment with cytotoxic or immunosuppressive drugs, radiation, presence of malignancies, old age, alcohol abuse, stress (emotional or physical), and dental manipulation are predisposing factors for reactivation.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The clinical features of herpes zoster can be grouped into three phases: (1) prodrome, (2) acute, and (3) chronic. During initial viral replication, active ganglionitis develops with resultant neuronal necrosis and severe neuralgia. This inflammatory reaction is responsible for the prodromal symptoms of intense pain that precedes the rash in more than 90% of the cases. As the virus travels down the nerve, the pain intensifies and has been described as burning, tingling, itching, boring, prickly, or knifelike. The pain develops in the area of epithelium innervated by the affected sensory nerve (dermatome). Typically, one dermatome is affected, but involvement of two or more can occur. The tho racic dermatomes are affected in about two thirds of cases. This prodromal pain, which may be accompanied by fever, malaise, and headache, normally is present 1 to 4 days before the development of the cutaneous or mucosal lesions. During this period (before the exanthem) the pain may masquerade as sensitive teeth, otitis media, migraine headache, myocardial infarction, or appendicitis, depending on which dermatome is affected.

Approximately 10% of affected individuals will exhibit no prodromal pain. Conversely, on occasion there may be recurrence in the absence of vesiculation of the skin or mucosa. This pattern is called zoster sine herpete (zoster without rash), and affected patients have severe pain of abrupt onset and hyperesthesia over a specific dermatome. Fever, headache, myalgia, and lymphadenopathy may or may not accompany the recurrence.

The acute phase begins as the involved skin develops clusters of vesicles set on an erythematous base (Fig. 7-17). Within 3 to 4 days, the vesicles become pustular and ulcerate, with crusts developing after 7 to 10 days. The lesions tend to follow the path of the affected nerve and terminate at the midline (Fig. 7-18). The exanthem typically resolves within 2 to 3 weeks in otherwise healthy individuals. On healing, scarring with hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation is not unusual.

Oral lesions occur with trigeminal nerve involvement and may be present on the movable or bound mucosa. The lesions often extend to the midline and frequently are present in conjunction with involvement of the skin overlying the affected quadrant. Like varicella, the individual lesions manifest as 1- to 4-mm, white, opaque vesicles that rupture to form shallow ulcerations (Fig. 7-19). Involvement of the maxilla may be associated with devitalization of the teeth in the affected area.

Fig. 7-19 Herpes zoster. Numerous white opaque vesicles on the right buccal mucosa of the same patient depicted in Fig. 7-18.

Several reports have documented significant bone necrosis with loss of teeth in areas involved with herpes zoster. Because of the close anatomic relationship between nerves and blood vessels within neurovascular bundles, inflammatory processes within nerves have the potential to extend to adjacent vessels. It is postulated that the gnathic osteonecrosis may be secondary to damage of the blood vessels supplying the alveolar ridges and teeth, leading to focal ischemic necrosis. Of the reported cases, there is almost an equal distribution between the maxilla and mandible, with both sexes affected similarly. Although the average patient age is approximately 55, a wide range has been seen from the second to late eighth decade. The average interval between the appearance of the exanthem and the osteonecrosis is 21 days, but it has been reported as late as 42 days.

Ocular involvement is not unusual and can be the source of significant morbidity, including permanent blindness. The ocular manifestations are highly variable and may arise from direct viral-mediated epithelial damage, neuropathy, immune-mediated damage, or secondary vasculopathy. If the tip of the nose is involved, this is a sign that the nasociliary branch of the fifth cranial nerve is involved, suggesting the potential for ocular infection. In these cases, referral to an ophthalmologist is mandatory.

Facial paralysis has been seen in association with herpes zoster of the face or external auditory canal. Ramsay Hunt syndrome is the combination of cutaneous lesions of the external auditory canal and involvement of the ipsilateral facial and auditory nerves. The syndrome causes facial paralysis, hearing deficits, vertigo, and a number of other auditory and vestibular symptoms. In multiple studies of patients thought to have Bell’s palsy (see page 859), evidenced of active VZV infection was detected in approximately 30% of patients by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or via demonstration of appropriate antibody titers, suggesting an underlying viral cause for many cases of “idiopathic” facial paralysis. Similar associations also have been demonstrated with HSV and EBV.

Approximately 15% of affected patients progress to the chronic phase of herpes zoster, which is characterized by pain (postherpetic neuralgia) that persists longer than 3 months after the initial presentation of the acute rash. Postherpetic neuralgia is uncommon in individuals under the age of 50 but affects at least 50% of patients older than 60 years of age. The pain is described as burning, throbbing, aching, itching, or stabbing, often with flares caused by light stroking of the area or from contact with adjacent clothing. Most of these neuralgias resolve within 1 year, with half of the patients experiencing resolution after 2 months. Rare cases may last up to 20 years, and patients have been known to commit suicide as a result of the severe, lancinating quality of the pain. Although the cause is unknown, some investigators believe chronic VZV ganglionitis is responsible. Clearance of the pain has been reported within days after initiation of long-term famciclovir, with recurrence of the pain if the medication is stopped. Additional double-blind, placebo-controlled studies will need to be performed to confirm this observation.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The active vesicles of herpes zoster are identical microscopically to those seen in the primary infection, varicella. For more information, refer to the previous portions of the chapter on the histopathologic presentation of varicella and herpes simplex.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of herpes zoster often can be made from the clinical presentation, but other procedures may be necessary in atypical cases. Viral culture can confirm the clinical impression but takes at least 24 hours. Cytologic smears demonstrate viral cytopathologic effects, as seen in varicella and HSV. In most cases the clinical presentation allows the clinician to differentiate zoster from HSV, but cases of zosteriform recurrent HSV infection, although uncommon, do exist. A rapid diagnosis can be obtained through the use of direct staining of cytologic smears with fluorescent monoclonal antibodies for VZV. This technique gives positive results in almost 80% of the cases. Molecular techniques such as dot-blot hybridization and PCR also can be used to detect VZV.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Before the development of the current antiviral medications, therapy for herpes zoster was directed toward supportive and symptomatic measures. Fever should be treated with antipyretics that do not contain aspirin. Antipruritics, such as diphenhydramine, can be administered to decrease itching. Skin lesions should be kept dry and clean to prevent secondary infection; antibiotics may be administered to treat such secondary infections.

Early therapy with appropriate antiviral medications such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir has been found to accelerate healing of the cutaneous and mucosal lesions, reduce the duration of the acute pain, and decrease the duration of postherpetic neuralgia. These medications are most effective if initiated within 72 hours after development of the first vesicle. The newer generation of antiviral drugs, famciclovir and valacyclovir, may be more successful than acyclovir in reducing the prevalence of postherpetic neuralgia.

Once the skin lesions have healed, the neuralgia may become the worst aspect of the disease and often is the most difficult to resolve successfully. This intense pain has been treated with variable results by a variety of methods, including analgesics, narcotics, tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, gabapentin, percutaneous electric nerve stimulation, biofeedback, nerve blocks, and topical anesthetics. As mentioned previously, postherpetic neuralgia may be related to chronic VZV ganglionitis and respond to long-term famciclovir. In those who do not respond to famciclovir, IV acyclovir often leads to clinical improvement.

One topical treatment, capsaicin, has had significant success, with almost 80% of patients experiencing some pain relief; however, the medication’s effect often does not occur until 2 weeks or more of therapy. Capsaicin is derived from red peppers and is not recommended for placement on mucosa or open cutaneous lesions. Capsaicin has been associated with significant burning, stinging, and redness in 40% to 70% of patients, with up to 30% discontinuing therapy because of this side effect. After use, patients must be warned to wash their hands and avoid contact with mucosal surfaces.

Corticosteroid therapy has been used in the hope it might decrease the neural inflammation and associated chronic pain. Although conflicting research has been published, studies have shown no long-term benefit when corticosteroids are added to an acyclovir regimen. In addition, an increased prevalence of side effects was noted in groups treated with corticosteroids.

A live attenuated VZV vaccine has been approved for use in adults 60 years of age or older. The vaccine, Zostavax, is 14 times more potent than Varivax, the vaccine for chickenpox. In a study of more than 38,000 adults, Zostavax markedly decreased the prevalence of herpes zoster, as well as the morbidity and frequency of postherpetic neuralgia in those who did develop the infection. In an October 2006 press release, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that the vaccine be given to all people 60 years of age and older. This recommendation is being reviewed and becomes official only when published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

INFECTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS (MONO; GLANDULAR FEVER; “KISSING DISEASE”)

Infectious mononucleosis is a symptomatic disease resulting from exposure to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV, HHV-4). The infection usually occurs by intimate contact. Intrafamilial spread is common, and once a person is exposed, EBV remains in the host for life. Children usually become infected through contaminated saliva on fingers, toys, or other objects. Adults usually contract the virus through direct salivary transfer, such as shared straws or kissing, hence, the nickname “kissing disease.” Exposure during childhood usually is asymptomatic, and most symptomatic infections arise in young adults. In developing nations, exposure usually occurs by age 3 and is universal by adolescence. In the United States, introduction to the virus often is delayed, with close to 50% of college students lacking previous exposure. These unexposed adults become infected at a rate of 10% to 15% per year while in college. Infection in adulthood is associated with a higher risk (i.e., 30% to 50%) for symptomatic disease.

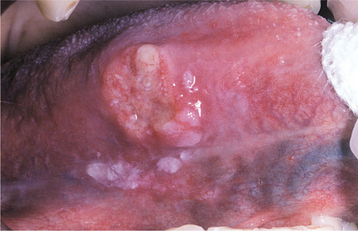

Besides infectious mononucleosis, EBV has been demonstrated in the lesions of oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) (see page 268) and has been associated with a number of lymphoproliferative disorders, a variety of lymphomas (most notably African Burkitt’s lymphoma) (see page 600), nasopharyngeal carcinoma (see page 428), some gastric carcinomas, possibly breast and hepatocellular carcinomas, salivary lymphoepithelial carcinomas, and occasional smooth muscle tumors. However, direct proof of a cause-and-effect relationship is lacking.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Most EBV infections in children are asymptomatic. In children younger than 4 years of age with symptoms, most have fever, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, hepatosplenomegaly, and rhinitis or cough. Children older than 4 years of age are affected similarly but exhibit a much lower prevalence of hepatosplenomegaly, rhinitis, and cough.

Most young adults experience fever, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, and tonsillitis. Hepatosplenomegaly and rash are seen less frequently. In adults older than 40 years of age, fever and pharyngitis are the predominant findings, with less than 30% demonstrating lymphadenopathy. Less frequent signs and symptoms in this group include hepatosplenomegaly, rash, and rhinitis or cough. Possible significant complications include splenic rupture, thrombocytopenia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, aplastic anemia, and neurologic problems with seizures. These complications are uncommon at any age but more frequently develop in children.

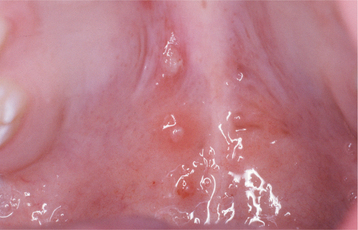

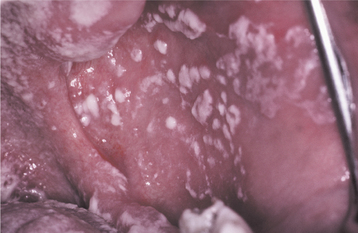

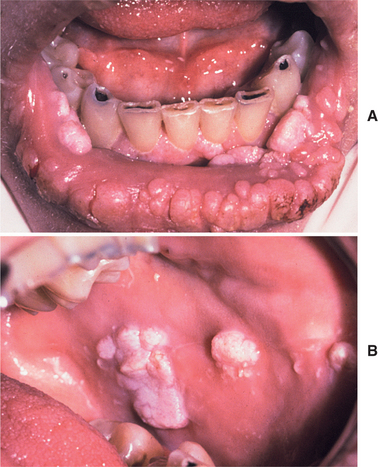

In classic infectious mononucleosis in a young adult, prodromal fatigue, malaise, and anorexia occur up to 2 weeks before the development of pyrexia. The body temperature may reach 104° F and lasts from 2 to 14 days. Prominent lymphadenopathy is noted in more than 90% of the cases and typically appears as enlarged, symmetrical, and tender nodes, frequently with involvement of the posterior and anterior cervical chains. Enlargement of parotid lymphoid tissue rarely has been reported and can be associated with facial nerve palsy. More than 80% of affected young adults have oropharyngeal tonsillar enlargement, sometimes with diffuse surface exudates and secondary tonsillar abscesses (Fig. 7-20). The lingual tonsils, which are located on the base of the tongue and extend from the circumvallate papilla to the epiglottis, can become hyperplastic and compromise the airway. Rare fatalities have been reported from respiratory difficulties secondary to the combined effects of hyperplasia of the lingual and palatine tonsils, arytenoid hypertrophy, pharyngeal edema, uvular edema, and epiglottal swelling.

Fig. 7-20 Infectious mononucleosis. Hyperplastic pharyngeal tonsils with yellowish crypt exudates. (Courtesy of Dr. George Blozis.)

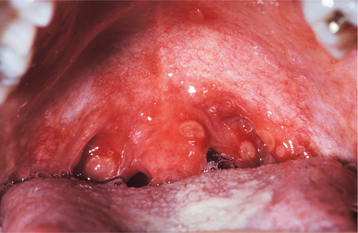

Oral lesions other than lymphoid enlargement also may be seen. Petechiae on the hard or soft palate are present in about 25% of patients (Fig. 7-21). The petechiae are transient and usually disappear within 24 to 48 hours. Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) (see page 157) also is fairly common. NUG-like pericoronitis (see page 171) and necrotizing ulcerative mucositis (see page 158) occur less frequently. Cases of NUG that are refractory to normal therapy should be evaluated to rule out the possibility of EBV.

Fig. 7-21 Infectious mononucleosis. Numerous petechiae of the soft palate. (Courtesy of Dr. George Blozis.)

A controversial symptom complex called chronic fatigue syndrome has been described, and several investigators have tried to associate EBV with this problem. Patients complain of rather nonspecific symptoms of chronic fatigue, fever, pharyngitis, myalgias, headaches, arthralgias, paresthesias, depression, and cognitive defects. These patients often demonstrate elevations in EBV antibody titers, but this finding alone is insufficient to prove a definite cause-and-effect relationship. Several studies have cast serious doubt on a relationship between EBV and the chronic fatigue syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis is suggested by the clinical presentation and should be confirmed through laboratory procedures. The white blood cell (WBC) count is increased, with the differential count showing relative lymphocytosis that can become as high as 70% to 90% during the second week. Atypical lymphocytes usually are present in the peripheral blood. The classic serologic finding in mononucleosis is the presence of Paul-Bunnell heterophil antibodies (immunoglobulins that agglutinate sheep erythrocytes). A rapid test for these antibodies is available and in-expensive. More than 90% of infected young adults have positive findings for the heterophil antibody, but infected children younger than age 4 frequently have negative results. Indirect immunofluorescent testing to detect EBV-specific antibodies should be used in those suspected of having an EBV infection but whose findings were negative on the Paul-Bunnell test. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and recombinant DNA-derived antigens also may be used in place of the indirect immunofluorescent test.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: In most cases, infectious mononucleosis resolves within 4 to 6 weeks. Non–aspirin-containing antipyretics and NSAIDs can be used to minimize the most common symptoms. Infrequent complications include splenic rupture, EBV-related hepatitis, and Bell’s palsy. Patients with significant enlargement of the spleen should avoid contact sports to prevent the rare possibility of splenic rupture. On occasion, the fatigue may become chronic. In immunocompromised patients, a polyclonal B-lymphocyte proliferation may occur and possibly lead to death.

The tonsillar involvement may, on occasion, resemble streptococcal pharyngitis or tonsillitis (see page 183). However, treatment with ampicillin and penicillin should be avoided because the use of these antibiotics in infectious mononucleosis has been associated with a higher than normal prevalence of allergic morbilliform skin rashes.

Corticosteroid use is the recommended therapy in many textbooks. Such drugs, however, should not be used indiscriminately because the person’s immune response appears to be the most important factor in fighting the infection and preventing a potentially fatal polyclonal B-lymphocyte proliferation. In addition, an increased prevalence of encephalitis and myocarditis has been noted in patients who have infectious mononucleosis and are treated with steroids. Corticosteroid use produces a shortened duration of fever and shrinkage of enlarged lymphoid tissues, but its use should be restricted to life-threatening cases (e.g., those with upper-airway obstruction because of massive lymphadenopathy, tonsillar hyperplasia, and oropharyngeal edema). If corticosteroid therapy fails to resolve the airway obstruction, acute tonsillectomy and tracheostomy may be necessary.

Although antiviral medications such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir have been used successfully for temporary resolution of oral hairy leukoplakia, these medications do not demonstrate clinically obvious benefit for patients with infectious mononucleosis. Although the medications most likely have an effect on viral replication, the main clinical manifestations appear to be secondary to the immune response to EBV-infected activated B lymphocytes and are not altered by the medical intervention.

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS

Cytomegalovirus (CMV, HHV-5) is similar to the other human herpes viruses (i.e., after the initial infection, latency is established and reactivation is possible under conditions favorable to the virus). CMV can reside latently in salivary gland cells, endothelium, macrophages, and lymphocytes. Most clinically evident disease is found in neonates or in immunosuppressed adults. In infants, the virus is contracted through the placenta, during delivery, or during breast-feeding. The next peak of transmission occurs during adolescence, predominantly from the exchange of bodily fluids as this group begins sexual activity. Transmission also has been documented from blood transfusion and organ transplantation. The prevalence of neonatal CMV infection varies from 0.5% to 2.5%. By the age of 30, almost 40% of the population is infected; by age 60, 80% to 100% are infected. Screening of healthy middle-aged adult blood donors reveals that approximately 50% have been exposed to CMV.

CLINICAL FEATURES: At any age, almost 90% of CMV infections are asymptomatic. In clinically evident neonatal infection, the infant appears ill within a few days. Typical features include hepatosplenomegaly, extramedullary cutaneous erythropoiesis, and thrombocytopenia (often with associated petechial hemorrhages). Significant encephalitis frequently leads to severe mental and motor retardation.

Although the majority of acute CMV infections are asymptomatic, less than 10% may include a nonspecific pattern of symptoms that ranges from an influenza-like presentation to lethal multiorgan involvement. In a review of 115 hospitalized immunocompetent adults with CMV infection, the most common symptoms (in order) include fever, joint and muscle pain, shivering, abdominal pain, nonproductive cough, cutane-ous eruption (maculopapular rash), and diarrhea. Associated signs include hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, adenopathy, pharyngitis, jaundice, and evidence of meningeal irritation. The authors stress that symptomatic CMV infection should not be dismissed in immunocompetent patients and should be considered in any patient with unexplained persistent fever.

In contrast to patients with infectious mononucleosis, only about one third of patients with CMV infection demonstrate pharyngitis and lymphadenopathy. Rarely, immunocompetent patients may show signs of an acute sialadenitis that diffusely involves all of the major and minor salivary glands. In such cases, xerostomia often is noted and the affected glands are painful. Involvement of the major glands usually results in clinically obvious enlargements of the parotid and submandibular glands. Unusual complications of primary CMV infection include myocarditis, pneumonitis, and septic meningitis.

Evident CMV involvement is not unusual in immunocompromised transplant patients. In some cases a temporary mild fever is the only evidence; in others, the infection becomes aggressive and is characterized by significant hepatitis, leukopenia, pneumonitis, gastroenteritis, and, more rarely, a progressive wasting syndrome.

CMV disease is common in patients with AIDS (see page 264). CMV chorioretinitis affects almost one third of patients with AIDS and tends to progress rapidly, often resulting in blindness. Bloody diarrhea from CMV colitis is fairly common but may respond to appropriate antiviral medications.

Although oral lesions from CMV infection have been documented in a number of immunosuppressive conditions, reports of oral involvement by CMV have been increasing since the advent of the AIDS epidemic. Most affected patients have chronic mucosal ulcerations, and CMV changes are found on biopsy. Occasionally, chronic oral ulcerations in immunocompromised patients will demonstrate coinfection (usually CMV combined with HSV).

Neonatal CMV infection also can produce developmental tooth defects. Examination of 118 people with a history of neonatal CMV infection revealed tooth defects in 40% of those with symptomatic infections and slightly more than 5% of those with asymptomatic infections. The teeth exhibited diffuse enamel hypoplasia, significant attrition, areas of enamel hypomaturation, and yellow coloration from the underlying dentin.

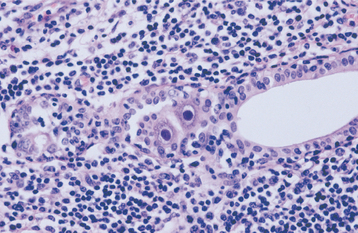

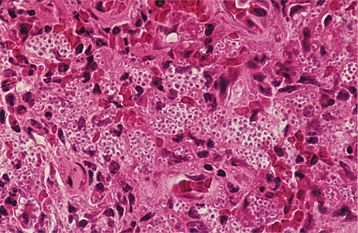

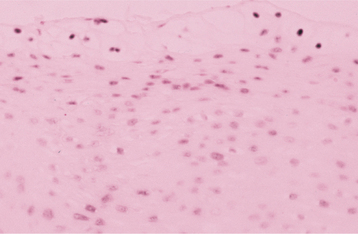

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Biopsy specimens of intraoral CMV lesions usually demonstrate changes within the vascular endothelial cells. Scattered infected cells are extremely swollen, showing both intracytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusions and prominent nucleoli. This enlarged cell has been called an “owl eye” cell. Gomori’s methenamine silver and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains demonstrate the cytoplasmic inclusions but not the intranuclear changes. Salivary ductal epithelium also may be affected and form “owl eye” cells (Fig. 7-22).

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of CMV infection is made by considering a combination of the clinical features and by conducting other examinations. Biopsy material can demonstrate cellular changes that suggest infection. Because effective therapies exist for CMV infections in immunocompromised patients, biopsies are recommended for chronic ulcerations that are not responsive to conservative therapy. More specific verification can be made by electron microscopy, detection of viral antigens by immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), demonstration of rising viral antibody titers, or viral culture. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) serologic testing for CMV is inexpensive, demonstrates good specificity, and should be considered in any patient with an unexplained fever or signs of CMV infection.

In immunocompromised patients with chronic ulcerations, the typical “owl eye” cells may be few and difficult to discover on routine light microscopy. When biopsy is performed on a chronic oral ulceration in these patients, in situ hybridization or immunohistochemical evaluation for CMV should be performed, even in the absence of “owl eye” cells. In addition, close examination to rule out coinfection by HSV also should be performed.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Although most CMV infections resolve spontaneously, therapy often is required in the immunosuppressed patient. Ganciclovir has resolved clinical symptoms in more than 75% of treated immunocompromised patients. However, the medication must be continued to prevent a relapse if the immune dysfunction persists. In patients with oral ulcerations coinfected with CMV and HSV, intravenous (IV) ganciclovir will produce resolution in most instances. The development of resistance to ganciclovir has been reported; other effective medications include foscarnet, cidofovir, and valganciclovir. In spite of these antiviral medications, the best therapy in immunocompromised patients remains improvement of their immune status, such as that achieved with highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) therapy in many patients with AIDS (see page 280).

Immunocompetent patients with clinically evident CMV infection usually are treated symptomatically with antipyretic medications and NSAIDs. Corticosteroids or IV gammaglobulins have been used in patients with hemolytic anemia or severe thrombocytopenia. There is no consensus related to the use of antiviral agents in immunocompetent patients.

ENTEROVIRUSES

Human enterovirus infections traditionally have been classified into echoviruses, coxsackieviruses A and B, and polioviruses. Beginning in the 1960s, newly discovered enteroviruses have been assigned a numeric designation (e.g., enterovirus 71) rather than being placed into one of the traditional groups. The clinical presentations associated with these viruses are diverse and vary from a minor febrile illness to a severe and potentially fatal infection. In addition, some of these viruses have been associated with an increased prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus and dilated cardiomyopathy. The estimated annual incidence of symptomatic infections in the United States is 10 to 15 million.

Of the enteroviruses, more than 30 exist that can result in symptomatic infections associated with rashes. Few are distinctive enough clinically to allow differentiation from one another. Most are asymptomatic or subclinical. These infections may arise at any age, but most occur in infants or young children. Neonatal cases also have been reported. Only herpangina, hand-foot-and-mouth disease, and acute lymphonodular pharyngitis deserve discussion. These three clinical patterns are closely related and should not be considered as entirely separate infections. In reports of epidemics in which a large number of patients acquire the same strain of the virus, the clinical presentations often are variable and include both herpangina and hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

Herpangina usually is produced by coxsackievirus A1 to A6, A8, A10, or A22. However, it also may represent infection by coxsackievirus A7, A9, or A16; coxsackievirus B2 to 6; echovirus 9, 16, or 17; or enterovirus 71. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease usually is caused by coxsackievirus A16, but may also arise from coxsackievirus A5, A9, or A10; echovirus 11; or enterovirus 71. Acute lymphonodular pharyngitis is less recognized, and coxsackievirus A10 has been found in the few reported cases. The incubation period for these viruses is 4 to 7 days.

Most cases arise in the summer or early fall in nontropical areas, with crowding and poor hygiene aiding their spread. The fecal-oral route is considered the major path of transmission, and frequent hand washing is emphasized in an attempt to diminish spread during epidemics. During the acute phase, the virus also can be transmitted through saliva or respiratory droplets. Infection confers immunity against reinfection to that one strain. In spite of the developed immunity, people may become infected numerous times with different enterovirus types over several years while still remaining susceptible to other different strains.

CLINICAL FEATURES: In many countries, epidemics occur every 2 to 3 years and primarily affect children aged 1 to 4 years. The timing of the epidemics appears to be correlated to the accumulation of a new population of susceptible young children. In all three clinical patterns, the severity and significant complications are variable and appear associated with the particular strain that is responsible. In general, most strains produce a self-limiting disease that requires no therapy, but occasional strains can produce epidemics with an increased number of significant complications and occasional mortalities. Systemic complications include pneumonia, pulmonary edema and hemorrhage, acute flaccid paralysis, encephalitis, meningitis, and carditis. Infection with coxsackie B virus during pregnancy occasionally has been associated with fetal and neonatal death, whereas cardiac anomalies have been noted in infants who survive the initial infection.

In 1998 a massive epidemic spread over Taiwan (population 21,178,000), and it is estimated that approximately 1.5 million people developed clinical evidence of the infection. A group of sentinel physicians (8.7% of primary physicians) documented 129,106 infected patients. Of these patients, the vast majority were infected with enterovirus 71; a much lesser number were infected with one of a number of coxsackieviruses (predominantly A16). When patients infected with the same strain were examined, clinical patterns diagnostic of both herpangina and hand-foot-and-mouth disease were detected. In this epidemic, more than 75% had symptoms of hand-foot-and-mouth disease, but it is clear these two clinical patterns represent variations of the same disorder.

In the surveillance document by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the reported enterovirus infections between 1970 and 2005, 44.2% occurred in infants younger than 1 year of age, 15% in children aged 1 to 4 years, 11.6% in children aged 5 to 9 years, 11.9% in those aged 10 to 19 years, and 17.3% in patients older than 20 years. During this period, 131 deaths were reported secondary to complications such as aseptic meningitis, encephalitis, paralysis, myocarditis, and neonatal enteroviral sepsis. The most common viruses to produce herpangina or hand-foot-and-mouth disease were, in order, coxsackieviruses B5, A9, B3, B1, and A16, followed by enterovirus 71. In patients younger than the age of 20, there was a male predominance. In those older than 20, females were infected more frequently, most likely because of exposure as the primary caregivers to infected young children.

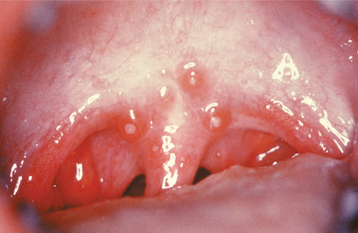

HERPANGINA: Herpangina begins with an acute onset of significant sore throat, dysphagia, and fever, occasion ally accompanied by cough, rhinorrhea, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, myalgia, and headache. Most cases, however, are mild or subclinical. A small number of oral lesions, usually two to six, develop in the posterior areas of the mouth, usually the soft palate or tonsillar pillars (Fig. 7-23). The affected areas begin as red macules, which form fragile vesicles that rapidly ulcerate. The ulcerations average 2 to 4 μm in diameter. The systemic symptoms resolve within a few days; as would be expected, the ulcerations usually take 7 to 10 days to heal.

HAND-FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE: Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is the most well-known enterovirus infection. Like herpangina, the skin rash and oral lesions typically are associated with flulike symptoms (e.g., sore throat, dysphagia, fever), occasionally accompanied by cough, rhinorrhea, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, myalgia, and headache.

The name fairly well describes the location of the lesions. Oral lesions and those on the hands almost always are present; involvement of other cutaneous sites is more variable. The oral lesions arise without prodromal symptoms and precede the development of the cutaneous lesions. Sore throat and mild fever are present. The cutaneous lesions range from a few to dozens and primarily affect the borders of the palms and soles and the ventral surfaces and sides of the fingers and toes (Fig. 7-24). Rarely other sites, especially the buttocks, external genitals, and legs, may be involved. The individual cutaneous lesions begin as erythematous macules that develop central vesicles and heal without crusting (Fig. 7-25).

Fig. 7-24 Hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Multiple vesicles of the skin of the toe. (Courtesy of Dr. Samuel J. Jasper.)

The oral lesions resemble those of herpangina but may be more numerous and are not confined to the posterior areas of the mouth. The number of lesions ranges from 1 to 30. The buccal mucosa, labial mucosa, and tongue are the most common sites to be affected, but any area of the oral mucosa may be involved (Fig. 7-26). The individual vesicular lesions rapidly ulcerate and are typically 2 to 7 μm in diameter but may be larger than 1 cm. Most of these ulcerations resolve within 1 week.

ACUTE LYMPHONODULAR PHARYNGITIS: Acute lymphonodular pharyngitis is characterized by sore throat, fever, and mild headache, which may last from 4 to 14 days. Low numbers (one to five) of yellow to dark-pink nodules develop on the soft palate or ton sillar pillars (Fig. 7-27). The nodules represent hyperplastic lymphoid aggregates and resolve within 10 days without vesiculation or ulceration. Few cases have been described, and whether this represents a distinct clinical entity is as yet unresolved. The possibility that the sore throat and palatal lymphoid hyperplasia represent features of herpangina or some other infection cannot be excluded without further documentation of additional cases.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: In patients with herpangina and hand-foot-and-mouth disease, the areas of affected epithelium exhibit intracellular and intercellular edema, which leads to extensive spongiosis and the formation of an intraepithelial vesicle. The vesicle enlarges and ruptures through the epithelial basal cell layer, with the resultant formation of a subepithelial vesicle. Epithelial necrosis and ulceration soon follow. Inclusion bodies and multinucleated epithelial cells are absent.