Chapter 13 Communication skills for the pharmacist

Introduction

Joan is a community pharmacist. At the end of the working day she thinks back to what has happened that day. She has discussed with customers their choice of over the counter (OTC) medicines, advised patients how to use their prescription medicines, conducted a medicines use review, phoned the local GP about a potential drug interaction, supervised a methadone addict, spoken briefly to the district nurse, who popped in to pick up some dressings for a patient, explained to a patient who needed to fill in a prescription exempt payment form, negotiated with her boss about a day off, interviewed a potential sales assistant, disciplined a sales assistant, exchanged pleasantries with the delivery person and had been introduced to the new chairman of the local pharmaceutical committee at lunchtime.

Ravi, a hospital pharmacist, similarly looked back at his working day. He had spent time on the wards discussing drug-related matters with junior doctors and nurses, as well as undertaking medication histories with a couple of patients and talking to a patient about their discharge medication. The latter task involved him phoning the patient’s GP and local pharmacist to arrange a continuity of medicine supply. He had helped run an induction course for pre-registration students and given a seminar at the lunchtime journal club for fellow pharmacists. Later in the day he had attended a committee meeting on developing policies for the safe use of medicines in the hospital. Representatives of other healthcare professionals and administrators in the hospital attended this meeting. He had finished off his day with a brief spell supervising the dispensary, when he had to deal with a complaint from a prescriber about an alleged aggressive phone call from pharmacy earlier in the day.

From the above descriptions of two pharmacists’ very different working days, it can be seen that while each is performing pharmaceutical tasks, all of these tasks required the use of communication skills. In fact, almost everything we do in life depends on communication. Pharmacists spend a large proportion of each working day communicating with other people – patients, doctors, other healthcare professionals, staff and others. Poor communication has the potential to cause a range of problems, from misunderstandings with healthcare professionals and others caused by incomplete/poor communication to inappropriate or incomplete advice on the use of medication causing potential harm to a patient/customer.

Thus there is a need for effective communication skills for pharmacists. But how effective is our communication? Many are able to talk at length, but do our listeners benefit from our words? Others may find talking to strangers difficult. Good communication demands effort, thought, time and a willingness to learn how to make the process effective. Some people find that good communication is difficult to achieve and an awareness of this fact is an important first step to improvement.

This chapter considers some of the elements of successful communication, looking first at the ways in which we assume things about other people and how this can influence our attitudes and then at the processes involved in communication, listening and questioning skills. A total model for an effective pharmacist–patient consultation is outlined, followed by the barriers to effective communication in pharmacy. The importance of confidentiality and the needs of special groups are considered. Finally there are some difficult situations to consider and practise.

Assumptions and expectations

It is said that you never get a second chance to make a first impression. When we meet somebody for the first time we make assumptions about that person. We often put people into categories and the assumptions lead to expectations of their behaviour, jobs and character.

This initial judgment of a person is often based purely on what we see and hear and includes appearance, dress, age, gender, race and physical disabilities. It is important that we are aware of these assumptions in order to avoid stereotyping people. For example, the impression we have of a person wearing a hooded jacket, baseball cap and jeans may be very different from that of the same person wearing a designer shirt and smart trousers. Conversely, people will make assumptions about us based on initial impressions; e.g. a pharmacist wearing a smart suit in a clean, clinical environment may inspire more confidence than a pharmacist wearing a scruffy jumper and working in a cluttered, untidy environment.

It is well documented that age and gender may affect how we communicate with people because of assumptions and expectations. We should not assume that people in wheelchairs cannot communicate effectively. Likewise, we must ensure that we direct our communication at an appropriate physical level and to the appropriate person (that is, to the patient in the wheelchair, not the person pushing it!).

Demeanour

The way in which people present themselves will lead to certain judgments being made. For example, people who stride aggressively towards someone else may make the person being approached feel defensive because the assumption may be made that they have come to make a complaint. However, people who approach hesitantly may lead to the assumption that this person needs help and advice, perhaps on a potentially embarrassing matter. Both assumptions may be wrong but will affect our behaviour and attitude in subsequent communication with this person.

Tone of speech, accents and common expressions

All of these have an impact on communication. Our response to a person speaking with a whining, complaining tone will differ from our response to someone who greets us in a friendly welcoming manner. Similarly, a cultured, ‘BBC’ English accent may invoke a different response from that to someone with a strong local accent.

No one experiences the same situation in the same way. While people may appear to be doing similar things, they will have different feelings about them. We can only guess what people are thinking or feeling from how they look and from their behaviour. For example, we may think that people are nervous if they move restlessly or twitch, but that may not be the case. It is also useful for us to consider how aware we are of our own behaviour and appearance and what message this may give to other people.

What is communication?

Communication is more than just talking. It is generally agreed that in any communication the actual words (the talking) convey only about 10% of the message. This is called verbal communication. The other 90% is transmitted by non-verbal communication which consists of how it is said (about 40%) and body language (about 50%). Non-verbal communication is well described in Chapters 22 and 44 and so is not discussed here, but see Example 13.1.

Example 13.1

To test your awareness of communication and assumptions there is a simple exercise. To be effective, you must not read the questions which follow just yet. Spend about 5 minutes talking to a person who you do not know very well – there is no particular topic, just let the conversation flow. After this time, turn away from each other and each write down your answers to the following questions:

Now come back together and share your answers about each other – do they surprise you? If you complete this exercise without ‘cheating’ you will realize just how many assumptions we make about other people with no evidence for them – and how wrong some of them are!

The communication process

Argyle (1983) describes the message process as a sender encoding a message which is then decoded by the receiver:

Mistakes can be made by both sender and receiver. The sender may not send the message they wished to send or they may sometimes intentionally seek to deceive. At the receiving end the message may not be decoded correctly. Poor communication skills contribute to these mistakes in encoding and decoding. Messages are not normally one way and if we send a message then we generally expect a reply, and so in replying the receiver becomes the sender and the sender becomes the receiver. While the messages may be going backwards and forwards between two people, effective communication becomes a helical model. In other words, what one person says influences how the other person responds in a spiral fashion with reiteration and repetition, coming back around the spiral at a different level each time.

Pharmacists tend to see contact with patients/customers as either getting information out of, or imparting advice to them. However this ignores the vital purpose of communication, which is to initiate and enhance the relationship with their patients/customers. If this can be achieved, then pharmacists will be perceived as more ‘patient friendly’ and more supportive of patients. Indeed good communication skills will make it easier for a pharmacist to seek information and advise patients.

Listening skills

Communication is not just about saying the right words; it involves listening correctly. If we do not listen properly, then it means we are not decoding the message that is being sent to us. In other words, however good the patient is at telling the pharmacist their symptoms, if the pharmacist does not listen correctly then the patient may be given the wrong diagnosis or the wrong medicine or the wrong advice. Listening and hearing are different. Hearing is a physical ability while listening is a skill. Listening skills enable a person to make sense of and understand what another person is saying. The listening process is an active one that consists of three basic steps, namely hearing, understanding and judging. The hearing stage means listening enough to catch what the person is saying. The understanding stage takes the listener from hearing to understanding the message in his or her own way (this may not be what was intended by the speaker). The judging stage takes the understanding stage and questions whether it makes sense. Do I believe what I have heard? Is it credible? Have I really understood what I have been told or have I misinterpreted the meaning?

How to be a good listener

Listening, like other skills, takes practice. Tips for developing good listening skills are shown in Box 13.1.

Box 13.1 Tips for being a good listener

In a pharmacy, avoid listening across a barrier such as a counter or desk, or getting too close and invading a patient’s ‘intimate zone’

Questioning skills

Pharmacists need effective questioning skills to obtain information from patients/customers. Examples of situations in which questioning skills are used include:

Effective questioning skills involve the use of different types of questions, namely open and closed questions. These are explained fully in Chapter 44 and their use is discussed in the questioning of patients in the treatment of minor ailments (Ch. 22).

Effective questioning can also be used in symptom analysis, which is another approach to assessing a patient’s presenting symptoms. The mnemonic PQRST provides key questions which will help pharmacists to obtain an overview of symptoms, although additional questions can be added, for example ‘Is the patient taking any concurrent medication?’ The PQRST approach to symptom analysis is shown in Box 13.2.

Box 13.2 PQRST symptom analysis

Ask: What were you doing when the problem started? Does anything make it better/worse, such as medicine or change in position?

Ask: Can you describe the symptom? How often are you experiencing it? What does it feel/look like or sound like?

Ask: Can you point to where the problem is? Does it occur or spread anywhere else? Do you have any other symptoms? (These symptoms may be related to the presenting symptoms)

However, questioning skills do not apply only to pharmacist–patient/customer situations. Good questioning skills are required in staff training, implementing procedures and other management tasks, as well as dealing with other healthcare professionals and administrative staff.

On many occasions questioning skills may not be in a face-to-face situation. Often a pharmacist has to communicate by telephone with, for example, a GP, a dentist, a district nurse, nursing home staff, hospital staff or patients’ relatives. The major drawback of this type of communication is that reliance is put solely on good verbal communication skills and not on the non-verbal aspect of communication. In these circumstances, it is vital to obtain the information as quickly and efficiently as possible. At the same time, the pharmacist must remain professional, give out accurate advice and offer reassurance if necessary. For example, when a GP phones to order a prescription medicine for a patient, the pharmacist is required to ask specific questions to ensure that all information is accurate. As another example, a patient phones to ask about a prescription item that may have been incorrectly dispensed, and, using good questioning skills, the pharmacist would check the prescription information, identify the patient’s concerns and be able to take appropriate action.

A model for guiding the pharmacist–patient interview

The Calgary–Cambridge model was developed in 1996 to aid the teaching of communication training programmes for medical students. Since that time it has been adopted widely by medical schools and has been used in other related disciplines (see Ch. 46 in which its use is described for the development of a concordance model for pharmacy, involving patients in decisions about their medicines). The Calgary–Cambridge model is designed to specifically integrate communication skills with the content skills of traditional medical history and thus the approach can be used by pharmacists for their core tasks, such as drug history taking and the interviewing of patients to determine the best treatment of presenting minor ailments.

The Calgary–Cambridge model has five main stages, namely:

Concomitantly and alongside these stages, the model provides for two further ongoing stages:

Providing the structure to the interview involves: Empathy with the patient by showing an understanding and appreciation of the patient’s feelings or predicament (see later in this chapter, p. 131)

Empathy with the patient by showing an understanding and appreciation of the patient’s feelings or predicament (see later in this chapter, p. 131)Some sensitive areas can be seen in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 Types of patients’ problems and the communication difficulties which they present

| Problem type | Examples | Communication difficulties |

| Embarrassing problems | Contraception; disorders of the reproductive system; hyperhydrosis; skin conditions | Obtaining privacy in the pharmacy. Establishing a common language of understanding. Demonstrating empathy and understanding. Establishing trust and confidentiality. Not exhibiting negative non-verbal behaviour |

| Emotional/psychological | Anxiety; depression; marital problems; drug abuse and dependence; stress | Demonstrating empathy and understanding. Insufficient time for counselling. Evaluating patient’s immediate needs. Establishing the nature and amount of advice to be given. Establishing two-way listening |

| Problems of handicap | ||

| Sensory | Blindness, deafness | Making inaccurate judgments regarding personality, intellect, etc. Providing effective explanations. Listening and taking sufficient time with patient. Overcoming social barriers |

| Physical | Paralysis, congenital deformity | |

| Communicative | Speech impairment | |

| Mental | Educationally subnormal | |

| Psychological | Personality disorders | |

| Social | Introversion | |

| Terminal illness | Knowing what to say and how to say it. Establishing patient’s feelings | |

| Financial problems | Interpreting cues given off by patient. Not embarrassing the patient regarding cost of medicines | |

An awareness of non-verbal behaviour is the next step in building the relationship. The awareness relates to the interviewers themselves – are they demonstrating good eye contact and other features of positive non-verbal behaviour? Are they picking up on any cues displayed by the patient’s non-verbal behaviour? Any note taking or reading (or use of computers these days) should not interrupt or affect the dialogue.

In building the relationship it is important to involve the patient and to share thoughts with them (e.g. ‘I think we are looking for a medicine that doesn’t cause drowsiness’), to provide a rationale for questions (e.g. explain why you need to know about concurrent prescribed medicines when recommending an OTC cough medicine), and to explain and ask permission if a physical examination is necessary.

We will now consider in more detail the stages of the interview process relevant to current pharmacy practice according to the Calgary–Cambridge model in order.

Initiating the session

Preparation involves the interviewer (the pharmacist) preparing him- or herself and focusing on the session. For example, in community pharmacy, a customer may request to see the pharmacist. The pharmacist will need to finish off at an appropriate point whatever task they were doing, probably take a few breaths and then focus on meeting the patient. At this moment it is important to establish initial rapport by greeting the patient, introducing yourself, the role and nature of the interview (e.g. a pharmacist conducting a drug medication history) and obtain consent, if necessary. The next step is to identify the reasons for the consultation by an opening question such as, for a patient requesting to see the pharmacist, ‘I understand that you would like to speak to me – how can I help?’ The patient’s answer must be listened to attentively and then the pharmacist needs to check and confirm the list of problems/queries/issues with the patient. During this stage the pharmacist should pick up on any verbal and non-verbal behaviour cues and help facilitate the patient’s responses. To complete this stage an agenda for the interview is negotiated (e.g. ‘so you would like me to recommend a medicine to help relieve your cough that doesn’t make you drowsy? Is that right?’).

Gathering information

An initial exploration of the patient’s problems, either disease or illness, is necessary and the patient should be encouraged to ‘tell their tale’ in their own words. Clearly the pharmacist needs to listen attentively and question appropriately using different types of question (open and closed) and suitable use of language (e.g. avoiding jargon and very technical language but not in a patronizing way). The pharmacist needs to be aware of verbal and non-verbal cues and the possible need to facilitate responses. It may be necessary to clarify what the person is saying (e.g. ‘What do you exactly mean by a stomach cold?’). Certainly it will be necessary to periodically summarize to check your own understanding of what the patient has said. This summarizing also allows the patient to correct any misinterpretation. A further exploration of the disease framework may be necessary and this may include symptoms analysis (see, for example, the PQRST symptoms analysis in Box 13.2) and more focused closed questions. The patient’s perspective is taken into account by the Calgary–Cambridge model at this stage in the interview, when a further exploration of the illness from the patient’s perspective is undertaken. This further exploration investigates the following:

The above are important and may indicate if a patient is unwilling to take, or is untrusting of, modern medicines. They may also indicate that a three times a day regimen and liquid oral medicine would be totally unsuitable for a patient and only a once a day regimen as a capsule would be appropriate. These are important issues for compliance and concordance (see Ch. 46).

Explanation and planning

This is the next stage of the interview, which has three areas, all of which are very appropriate to pharmacists (see Ch. 44):

To achieve a shared understanding: incorporating the patient’s illness framework (see Ch. 3)

To plan: shared decision making

All of the above stages, although designed for medical interviews, are very relevant to pharmacists. Patients need to be involved in decisions about any treatment with medicines, and they need to be given sufficient information on what the medicine is used for and how to take it in a way that is achievable in their lifestyle. Also patients should be offered some information on side-effects so that they can make an informed choice. Chapter 46, on Concordance, clearly expresses this approach.

Closing the session

At the end of the session it is important to summarize what has taken place and the joint decisions made. The patient should also be informed about the next stage; for example this could be seeing how the medicine works and coming back to the pharmacy if the patient feels the medicine is not working. Ensure the patient knows what to do if the problem/symptoms do not resolve (e.g. go to see the doctor), and finally, check whether the patient agrees and feels comfortable with the chosen plan or needs to discuss any other issues.

Patterns of behaviour in communication

A number of terms are used in connection with behaviour during communication:

Assertiveness is a positive way of relating to other people – a means of communicating as effectively as possible, particularly in potentially awkward situations. Assertive behaviour is useful when dealing with conflict, in negotiation, leadership and motivation, when giving and receiving feedback, in cooperative working and in meetings. Assertive communication can give the user confidence, a clearer self-image and leads to a feeling of more control over situations, especially those of conflict.

People who behave assertively usually achieve what they set out to do. This does not necessarily mean that the other person does not also achieve what they set out to do. This is in comparison to those who act aggressively, who think that they have achieved their goal, but this is usually at the cost of respect and loyalty from those around them. Submissive people rarely achieve what they want.

Part of assertiveness is recognition of personal rights and the rights of others. Box 13.3 lists examples of personal rights.

Techniques in assertive communication

Use of ‘I’ and ‘You’ statements

Using ‘I’ rather than ‘You’ in a statement places the responsibility with the asserter rather than attempting to place the responsibility on the other person. Use of ‘I’ statements can minimize negative reactions such as anger. For example, compare the following two statements which are effectively saying the same thing: ‘You appear to have been arriving rather late for work recently’ and ‘I have noticed that you have been arriving rather late for work recently’. The first statement gives an impression of accusation while the second is more observational and less threatening.

Repeating the message

If a request for information is not being answered directly by the receiver, a useful assertive technique is to repeat the request. If this is done firmly and without aggression, the message can be repeated until a reply is obtained. However, there are situations when this technique would not be appropriate, e.g. when an answer to the request has been given, even though it may not be the desired response (as when children repeatedly ask for sweets and the parent has already said ‘No!’). Repeating this request will not be helpful and will aggravate the situation.

Clear communication

To communicate we use both verbal and non-verbal language. Both are important and it is essential that they match or we will send mixed and confusing messages. An example of a mixed message in a community pharmacy may arise when asking a patient if she understands how to take her dispensed medicine. An affirmative reply may be given verbally by the patient but non-verbal signs such as close examination of the label and a creased forehead may indicate some confusion which would need to be clarified.

Extracting the truth

Strong emotions can get in the way of clear communication. Communicators who are angry or upset may cloud the message they are trying to convey with other issues. They may exaggerate or become emotional. It is important, as the receiver, to accept this in an assertive manner. Acknowledge true criticisms but do not be distracted by side issues.

Self-talk

In a situation of conflict we can often ‘work ourselves up’ to an angry or emotional state which can then lead to unclear and unsuccessful communication. If we use self-talk (i.e. talk to yourself) and clarify the issues in a situation, considering the points of view and rights of all those involved, not just ourselves, we can often defuse the situation inside ourselves. We can then be ready to undertake clear, unconfused communication which will lead to a more successful outcome. Self-talk does not have to involve ‘giving way’ to the other person. Rather it is a way of controlling naturally felt emotions and then, instead of ‘letting fly’, expressing yourself in a manner which is more likely to produce the desired result.

There are a number of steps which you could follow to increase your assertiveness:

Empathy

Illness is often associated with different emotional aspects, like uncertainty, stress, fear and dependency. The ability to enter into the life of other people and accurately to understand both their meaning and their feelings is called empathy. It involves an accurate perception and identification of both the actual words and underlying feelings contained in what a person is saying. Pharmacists need the skill to respond in a way that communicates this understanding convincingly. Empathy is one of the cornerstones in communication skills and is an essential part of assertiveness. It is needed in information gathering, when interviewing customers and patients and when educating and counselling. Furthermore, the resolution of conflict situations requires empathic understanding. There are three elements to empathic communication.

Facilitating empathy

Being empathic requires that pharmacists are able to communicate their readiness and willingness to listen to other people and to establish a safe non-threatening atmosphere where they can express themselves. Much of this communication is non-verbal in nature, like eye contact, tone of voice and body posture. There is also a need to express respect and assurance that there is no need for embarrassment or fear of being criticized. People often speak intellectually about a problem rather than saying how they feel. Pharmacists should encourage them to describe their feelings. This does not mean that we should force people to say things they are not ready for.

Perceiving feelings and meaning

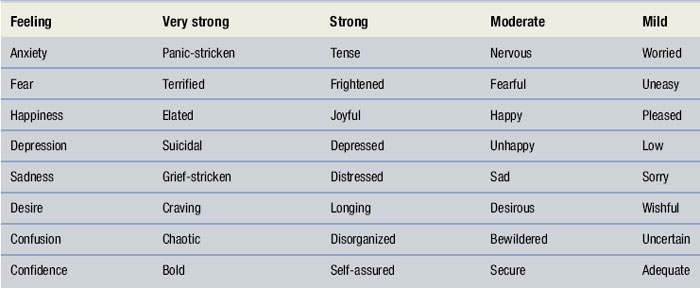

The correct identification of feelings and their meaning is important for pharmacists in their work. Patients often experience a combination of feelings, like being unfairly treated, hurt, depressed and angry. These need to be identified in order to respond properly. It is also important to pay attention to non-verbal communication and how closely it agrees with the verbal communication. Facial expressions and body movements may communicate more accurately how the person feels than is being verbally expressed initially. Some words commonly used to express different intensity of feelings are shown in Table 13.2.

When trying to identify meanings and feelings of others it is necessary to be aware of our own personal biases, prejudices, stereotyped impressions or a preoccupation with personal concerns. We have our own assumptions about how people, such as those with depression, feel and behave, or stereotyped views, e.g. that all drug addicts are the same.

Responding

The third component, responding, involves the verbal and non-verbal expression of how much we understood and that we are interested to hear more. Often, it may be tempting to just use the phrase ‘I understand how you feel’. This may generate the answer ‘No, you don’t!’ It is better to respond by restating and reflecting feelings, i.e. to restate what was said in slightly different words. Another way is to try to help people focus and clarify their own feelings on what is most important for them. You can also verbalize implied meanings or ask for further clarification.

How we communicate empathic listening is important. The most likely way to be effective is by understanding and focusing. Other helpful approaches include quizzing and probing, analysing and interpreting, advising, placating and reassuring. All of these include potential pitfalls but when used appropriately they can be effective. One technique that is rarely effective is generalizing the problem, e.g. when trying to give comfort you say that the problem is ‘not serious’ or ‘everybody has it’. Other ineffective techniques include judging people or their actions, and warning or threatening them.

Just as with all other communication skills, some people are more empathic than others, but empathy and empathic listening can be practised and improved. This requires an active willingness to learn from experience and analyse different situations and our own actions and reactions with an open mind.

Barriers to communication

In a pharmacy setting there are a number of factors which can be of benefit to, or can detract from, the quality of any communication. Common barriers which exist can be identified under four main headings:

Environment

Community pharmacies, hospital outpatient pharmacies and hospital wards are all areas where pharmacists use their communication skills in a professional capacity. None of these areas is ideal, but an awareness of the limitations of the environment goes part of the way to resolving the problems. Some examples of potential problem areas are illustrated below:

A busy pharmacy. This may create the impression that there appears to be little time to discuss personal matters with patients. The pharmacist is supervising a number of different activities at the same time and is unable to devote his full attention to an individual matter. It is important that pharmacists organize their work patterns in such a way as to minimize this impression.

Lack of privacy. Some pharmacies, both in the community and in hospital outpatient departments, have counselling rooms or areas, but many have not. Many hospital wards could be likened to a busy thoroughfare. For good communication to occur and rapport to be developed, ideally the consultation should take place in a quiet environment, free of interruptions. Lack of these facilities requires additional skills.

Noise. Noise within the working environment is an obvious barrier to good communication. People strain to hear what is said, comprehension is made more difficult and particular problems exist for the hearing impaired. The opposite may also be true, where a patient feels embarrassed having to explain a problem in a totally quiet environment where other people can ‘listen in’.

Physical barriers. Pharmacy counters and outpatient dispensing hatches are physical barriers and also may dictate the distance between pharmacist and patient. This in turn can create problems in developing effective communication. A patient in bed (or in a wheelchair) and a pharmacist standing offers a different sort of barrier which will create a sense of inferiority in the patient. Ideally faces should be at about the same level.

Patient factors

One of the main barriers to good communication in a pharmacy can be patients’ expectations. In today’s world people have busy and hectic lifestyles. In many cases they have become used to seeing a ‘good’ pharmacy as one where their prescription is dispensed quickly. They are not expecting the pharmacist to spend time with them checking their understanding of medication or other health-related matters. However, once the purpose of the communication is explained, most patients realize its importance and are quite happy to enter into a dialogue.

Physical disabilities. Dealing with patients who have sight or hearing impairment will require the pharmacist to use additional communication skills. Practical suggestions on help which can be given to patients with sight impairment can be found in the chapter on counselling (see Ch. 44). Dealing with the hearing impaired is discussed in lates this chapter.

Comprehension difficulties. Not all people come from the same educational background and care must be taken to assess a patient’s level of understanding and choose appropriate language. In some cases the lack of ability to comprehend may be because English is not the patient’s first language. Pharmacists working in areas where there is a high proportion of non-English speakers may find it useful to stock or develop their own information leaflets in appropriate languages.

Illiteracy. A significant proportion of the population, both in the UK and in other countries, is illiterate. For these patients written material is meaningless. It is not always easy to identify illiterate patients as many feel ashamed and are unlikely to admit to it, but additional verbal advice can be given and pictorial labels can be used. For example the United States Pharmacopoeia has designed a range of pictograms for this purpose.

The pharmacist

Not all pharmacists are natural, good communicators. Identifying strengths and weaknesses will assist in improving communication skills. Some of the weaknesses which can be barriers to good communication are:

If any of these characteristics is present, the reason for it should be identified and resolved, if possible.

Time

In many instances time, or the lack of it, can be a major constraint on good communication. Try developing a meaningful conversation with someone who constantly looks at his watch! Similarly, if the person who has initiated the conversation is short of time, the wrong kind of questions may be used or little opportunity for discussion will be allowed. It is always worthwhile checking what time people have available before trying to embark on any communication. That way you will make the best use of what time is available.

Not all barriers to good communication can be removed, but an awareness that they exist and taking account of them will go a long way towards diminishing their negative impact.

Confidentiality

Matters related to health and illness are highly private affairs. Therefore it is important that privacy and confidentiality are assured in the practice of pharmacy.

According to the public, lack of privacy is one of the most important issues when developing pharmacy services. The public expects pharmacists to respect and protect confidentiality and have premises that provide an environment where you can communicate privately without fear that personal matters will be disclosed. There is a need to maintain the trust of the public by communicating in such a way that no doubts about lack of privacy or confidentiality arise. This concerns the whole staff of the pharmacy, not just the pharmacists.

Physical privacy can be assured by providing facilities (not necessarily always private counselling rooms) that allow communication without somebody else overhearing a private conversation. In addition there is a need to provide psychological privacy and this has much to do with how things are perceived. It is possible, by appropriate communication, to minimize the impact of distracting factors. The techniques are often non-verbal, such as proper use of the voice (not too loud, not too low), eye contact, leaning forward and concentrating on the person and their problem.

Ethical guidelines and privacy laws set the rules about confidentiality in pharmacy. Any information relating to an individual which the pharmacist or any other staff member acquires in the course of their professional activities has to be kept confidential. When communicating with other healthcare professionals it may be difficult to draw the line between what is acceptable and what is not acceptable. Without the consent of the person, only information to prevent serious injury or damage to the health of the person can be shared. We must act in the interests of patients and other members of the public. When communicating with patients/customers it is also important to respect patients’ rights to participate in decisions about their care and to provide information in a way in which it can be understood.

Special needs

Patients with special needs must be considered carefully when adopting questioning skills. We need to be non-patronizing, avoid the use of jargon and adopt a procedure for obtaining information which is acceptable to the patient. Blind people will not be able to read any written material, unless it is in Braille. Special labels are available. They may also require some compliance aids to assist with measuring doses.

Many customers who come into pharmacies will suffer from a degree of hearing impairment. Studies have shown that one in six of the adult population in the UK has clinically significant hearing loss. By retirement age (61–70 years old), around 34% of people have significant hearing loss; this increases to 74% in people aged over 70. Considering that people in these age groups present the highest number of prescriptions, it is evident that pharmacists must implement appropriate communication skills.

Recognizing the profoundly deaf is usually simpler than recognizing those who have hearing impairment. The following guidelines may be useful for identifying these customers.

How to recognize the hearing impaired

A person with hearing difficulty is likely to do one or more of the actions listed in Box 13.4. Having recognized a customer with hearing impairment, the guidelines in Box 13.5 are helpful. Listening, and being able to demonstrate that you are listening, is very important using non-verbal responses for the deaf.

Difficult situations in pharmacy

There are times in all our lives when we have to deal with ‘difficult situations’. Good communication skills may not always produce the perfect result but can help prevent making a situation worse. Further examples of difficult situations in pharmacy can be found in Table 13.1 and Example 13.2.

Example 13.2

Read through the following scenarios and think carefully how you would react and deal with such a situation in real life. Consider how the other person would be feeling. Remember, there is no one perfect answer. Discuss the scenarios with a friend or group of friends. This will also allow you to identify the different ways people react to the same situation.

Conclusion

Good communication is not easy and needs to be practised. We all have different personalities and skills which means that we have strengths in some areas and weaknesses in others. If we can become aware of, and maximize, our strengths and work to minimize our weaknesses, we will become better communicators. Being articulate and able to explain things clearly is of great importance to a pharmacist. However, listening with understanding and empathy is of equal, and in certain situations of greater, importance. We may all hear the words being said, but are we really listening to the complete message?

This chapter has emphasized communication skills for pharmacists, particularly in the workplace, but remember, good communication is a life skill to be used at all times.