32 Respiratory emergencies

Feline Pleural Effusion

Theory refresher

Pleural effusion is a relatively common cause of severe respiratory distress in cats. A rational and considered approach to the stabilization of these cats is essential as they are typically critical and very susceptible to stress. In many cases, the pleural effusion would have been present for some time with little or no clinical manifestation; eventually a point is reached where the ability of the lungs to expand becomes so compromised that the cat is no longer able to cope. In addition, depending on the underlying cause, there may also be other pathological abnormalities compromising respiration (e.g. pulmonary oedema in congestive heart failure).

Causes

Causes of pleural effusion in cats include:

In the author’s experience, neoplasia and congestive heart failure (see Ch. 31) are the two most common causes identified in cats (see Figures 32.1-32.4).

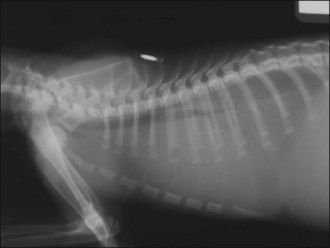

Figure 32.1 Right lateral thoracic radiograph of a cat with pleural effusion secondary to a cranial mediastinal mass.

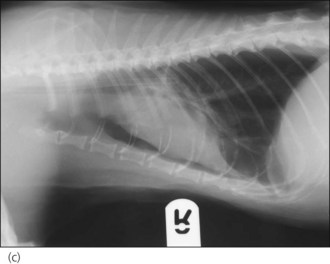

Figure 32.2 Right lateral thoracic radiograph of a cat with severe pleural effusion (diagnosis not made).

Case example 1

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 4-year-old male neutered domestic short hair cat presented with acute respiratory distress. The owner reported that the cat had a several day history of lethargy and inappetence, and that there may have been some weight loss in the preceding weeks. When the owner returned from work that evening she had found the cat to be dyspnoeic and arranged an emergency consultation. The cat had not previously been tested for feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) or feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). No other significant history was reported.

Clinical Tip

Observation

The cat was initially briefly observed in his carrier. He appeared alert and pupils were not mydriatic. Respiratory rate was increased with a moderate mixed increase in respiratory effort (including increased abdominal effort). The cat was not obviously cyanotic and was sitting in sternal recumbency with no obvious evidence of trauma.

Brief examination

It was possible to remove the top of the cat’s carrier and as he appeared relatively calm, a brief examination was performed while he remained sitting in the same position. Flow-by oxygen supplementation had been started already. Sternal cardiac auscultation revealed a subjectively normal heart rate and neither a gallop sound nor a cardiac murmur could be heard. However, the heart sounds appeared muffled. Lung sounds were very dull ventrally and this appeared bilaterally symmetrical. Femoral pulses were normal.

Oxygenation and client discussion

Following the brief examination, the cat was placed in an oxygen cage, still in his carrier with the top off, and kept under close observation. As the cat was readily compliant, morphine (0.1 mg/kg i.m.) was administered at this point in anticipation of thoracocentesis. The owner was advised that it was suspected that the cat had a pleural effusion for which the two most common causes in cats are neoplasia, especially lymphoma, and congestive heart failure; other possibilities in this case included pyothorax and an idiopathic effusion. The owner was keen to persevere with trying to stabilize the cat with a view to achieving a definitive diagnosis.

Further case management

The cat’s respiration had improved to some extent following initial oxygen therapy but there was still a marked increase in respiratory effort. Given the suspicion of pleural effusion, it was decided to perform thoracocentesis for diagnostic and potentially therapeutic purposes (see p. 291). The procedure was only performed on the right side as a large volume of pleural fluid was removed (250 ml, approximately 50 ml/kg) and the cat’s breathing improved significantly almost immediately. The cat was returned to the oxygen cage following thoracocentesis after clipping the fur over both cephalic veins and applying topical local anaesthesia (EMLA® cream 5%, AstraZeneca – see Ch. 5) to both sites. The pleural effusion was grossly milky in appearance. In-house cytology revealed that more than half of the cells present were small lymphocytes, and no bacteria were seen. It was therefore presumptively classified as a chylous effusion but samples had also been collected into additional sterile containers for submission to an external laboratory.

The cat remained comfortable in the oxygen cage and a cephalic intravenous catheter was placed later using minimal restraint and gentle handling. Blood was obtained via the catheter for an emergency database to be performed that was essentially unremarkable. As congestive heart failure remained a possibility, the cat was not started on intravenous fluid therapy at this time and the catheter was kept patent by regular flushing. Morphine (0.1 mg/kg slow i.v. q 6 hr) was continued but no other medications were indicated at this stage.

The cat remained stable overnight and it was possible to wean him off oxygen therapy. He was referred the next morning for further investigations which revealed a cranial mediastinal mass that was confirmed to be due to lymphoma. The cat was started on chemotherapy and was doing well at his most recent follow-up examination.

Feline Bronchial Disease (Asthma)

Theory refresher

Feline bronchial disease is the result of inflammation of the lower airways without an identifiable cause. A number of different terms have been used in the literature to refer to the same syndrome, including feline lower airway disease, feline allergic airway disease and feline asthma. The disease occurs most commonly in young to middle-aged cats and Siamese cats are overrepresented. Allergens or nonspecific airway irritants are likely to be involved in initiating or at least exacerbating airway inflammation. The relationship between respiratory infection and feline bronchial disease remains to be clarified.

Clinical signs are due to obstruction of the lower airways as a result of bronchial inflammation and subsequent smooth muscle constriction, oedema, mucous gland hypertrophy and excessive mucus secretion, and airway hyperactivity. In some cats, these changes are reversible, while in others chronic inflammation results in irreversible fibrosis and emphysema. Eosinophils are typically the primary inflammatory cells involved in the pathophysiology.

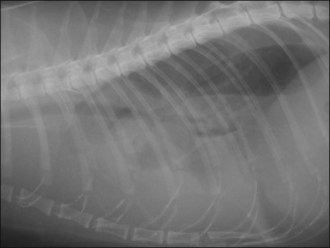

Clinical signs most commonly include coughing, and variable degrees of tachypnoea or dyspnoea. Severe obstruction of the lower airways prevents cats from exhaling completely, resulting in air trapping and hyperinflation of the lungs; this is identified radiographically as increased pulmonary radiolucency and a flattened, caudally displaced diaphragm.

Case example 2

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 6-year-old female neutered Siamese cat presented with acute onset respiratory distress. The owner reported that over the preceding 2 months the cat had been heard to cough occasionally, typically at night, but there was no other significant history. The cat was kept exclusively indoors, was fully vaccinated, and had previously been found to be negative for feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV).

Clinical Tip

Observation, brief examination

On presentation the cat was in lateral recumbency with dilated pupils, open-mouth breathing and showing paradoxical abdominal movement. This is an ominous sign and the cat was therefore immediately started on oxygen supplementation. Very brief examination was performed that revealed a mild subjective bradycardia with no gallop sound or heart murmur heard; femoral pulse quality was unremarkable. Lung sounds were diffusely harsh with some wheezes.

Assessment

The respiratory findings were most consistent with feline lower airway disease, diffuse cardiogenic pulmonary oedema or pulmonary contusions. However, the cardiovascular examination was less suggestive of congestive heart failure and crackles would most likely be expected in a cat with such severe dyspnoea. The cat was an indoor cat and there was no history or other suggestion of blunt trauma. Both the history of coughing and signalment were also supportive of lower airway disease being the most likely diagnosis.

Case management

The cat was immediately administered dexamethasone (0.25 mg/kg i.m), terbutaline (0.01 mg/kg i.m.) and furosemide (2 mg/kg i.m.). Despite the suspicion of lower airway disease, furosemide was included in the initial therapy as a single dose is unlikely to be especially harmful in the absence of hypoperfusion or significant dehydration, and could potentially be life-saving if significant pulmonary oedema was in fact present. An intravenous catheter was placed into a cephalic vein and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database to be performed which was essentially unremarkable.

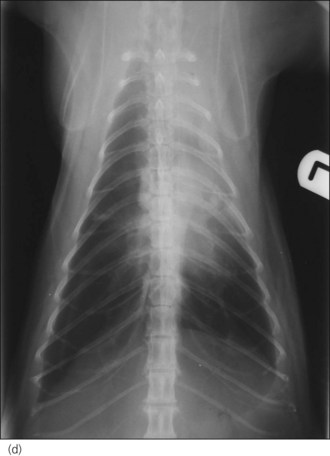

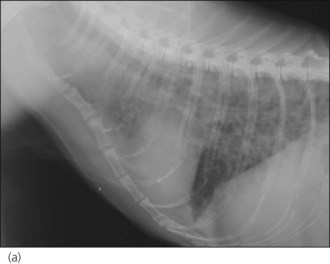

Oxygen supplementation was continued and the cat monitored closely, and she slowly began to show improvement. At the appropriate time, thoracic radiographs were taken under mild sedation (butorphanol 0.2 mg/kg i.v.) and revealed a severe diffuse bronchointerstitial lung pattern (Figure 32.5). A diagnosis of chronic bronchial disease with acute exacerbation was made.

Figure 32.5 (a) Right lateral and (b) dorsoventral thoracic radiographs of a cat showing a severe diffuse bronchointerstitial lung pattern.

The cat was maintained on oxygen supplementation, dexamethasone (0.25 mg/kg i.v. q 24 hr), terbutaline (0.01 mg/kg s.c. q 4 hr) and maintenance intravenous isotonic crystalloid therapy (buffered lactated Ringer’s solution at 2 ml/kg/hr). She made a slow but steady recovery and was eventually discharged on oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg p.o. q 12 hr) and inhaled bronchodilator therapy (albuterol). A plan for ongoing management, including tapering of oral prednisolone and switching to inhaled fluticasone, was agreed with the owner. The owners were questioned at length and advised extensively about possible allergens (e.g. cat litter, cigarette smoke, carpet cleaners, air fresheners) in the home and the importance of minimizing the cat’s exposure to them.

Canine Upper Respiratory Tract Obstruction

In the author’s experience, upper respiratory tract obstruction is one of the most common causes of acute respiratory distress in dogs, especially in warmer weather following exercise. The two most common disorders are laryngeal paralysis and brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome (BAOS). The initial approach to the stabilization of these dogs involves common interventions that centre on:

Occasionally dogs with chronic tracheal collapse present in an acute respiratory crisis.

Laryngeal paralysis

Theory refresher

Laryngeal paralysis is the result of dysfunction of the recurrent laryngeal nerves that supply the muscles which move the arytenoid cartilages. It may be congenital or acquired, and is almost always filateral in clinically symptomatic dogs.

In most cases acquired laryngeal paralysis is presumptively diagnosed as idiopathic; it may be that some of these cases are in fact due to an otherwise subtle generalised polyneuropathy. Acquired laryngeal paralysis may also be traumatic or iatrogenic in orgin.

There is a high incidence of megaoesophagus amongst dogs with laryngeal paralysis and these animals are also at risk of aspiration pneumonia. Thoracic radiographs are therefore indicated in all cases and can be taken while the patient is intubated if applicable. Noncardiogenic pulmonary oedema may also be identified following upper respiratory tract obstruction, typically in the caudodorsal lung field.

Case example 3

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 9-year-old male neutered chocolate Labrador retriever presented with severe respiratory distress. The dog had been out exercising a few hours prior to presentation and had developed respiratory distress that had progressed since returning home. Subsequent questioning of his owner after stabilization revealed that he had a chronic history of intermittent coughing.

Clinical Tip

Major body system examination

On presentation the dog was cyanotic, recumbent and extremely anxious. Loud inspiratory stridor was obvious and there was marked inspiratory effort. Respiratory rate was 60 breaths per minute. The dog was tachycardic (heart rate 150 beats per minute) but cardiovascular examination was otherwise unremarkable. Rectal temperature was elevated at 40.5°C and was interpreted as hyperthermia (as opposed to pyrexia; see Ch. 16).

Assessment

Initial assessment was that the dog’s most serious abnormality was upper respiratory tract dyspnoea that was most likely secondary to laryngeal paralysis.

Clinical Tip

Case management

Flow-by oxygen supplementation was commenced immediately. An intravenous catheter was placed (with collection of blood at the time of placement for an emergency database) and acepromazine (0.02 mg/kg) and butorphanol (0.3 mg/kg) administered intravenously. The dog was wetted with cool water and a fan applied, and he was then subjected to minimal stress.

The cyanosis resolved quickly and 20 minutes after sedation there had been some improvement in respiratory status. Rectal temperature had reduced to 39.5°C and cooling was therefore stopped to avoid rebound hypothermia. Oxygen supplementation was discontinued and dexamethasone (0.25 mg/kg i.v.) administered. Intravenous isotonic crystalloid fluid therapy (3 ml/kg/hr) was provided early on and repeat sedation performed as required until the dog’s respiratory status had normalized. Subsequent referral for suspected laryngeal paralysis was arranged.

Clinical Tip

Brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome (BAOS)

Brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome (BAOS) is the result of poor conformation that predisposes certain dogs to airway obstruction. Breeds affected by this condition include bulldogs, the Pekingese, pugs and the Boxer. Components of BAOS include:

Affected dogs often also have a degree of tracheal hypoplasia. Following emergency stabilization as required, surgical intervention is usually necessary to improve the dog’s clinical status long-term.

Feline Upper Respiratory Tract Obstruction

Although much less common than in dogs, occasionally cats present with severe upper respiratory tract dyspnoea. This is most commonly the result of a mass lesion (e.g. laryngeal lymphoma, nasopharyngeal polyp), although laryngeal paralysis has also been reported in cats. Although brachycephalic cats may have severe conformational abnormalities, the author has not seen one of these cats present with an associated primary acute respiratory crisis. However poor conformation will execerbate the effects of other disorders such as upper respiratory tract infection.