27 The Thorax of the Ruminant

The extent and dimensions of the thoracic cavity are not apparent on inspection of the live animal.

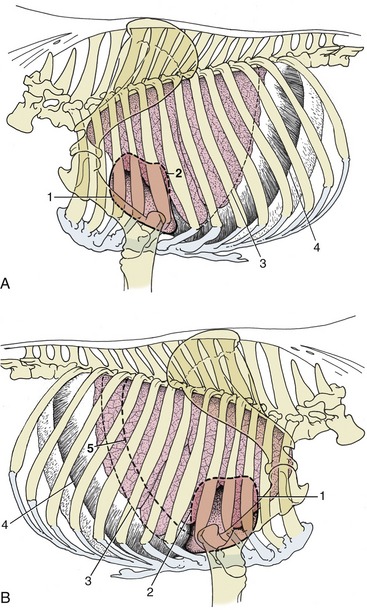

The inclusion of the upper segments of the forelimbs within the skin of the trunk reveals the narrowness of the cranial part of the thorax but fails to indicate its shallowness or how much of the space enclosed by the ribs is occupied by the abdomen (Figure 27–1). Certain features of the limb skeleton provide helpful guides to the location of deeper parts: the point of the shoulder projects a few centimeters in front of the lower part of the first rib, the caudal angle of the scapula lies over the vertebrae dorsal to the sixth rib, and the point of the elbow lies over the fifth intercostal space, just above the costochondral joints, and just a short way cranial to the vertex of the diaphragm (Figure 27–2, A-B).

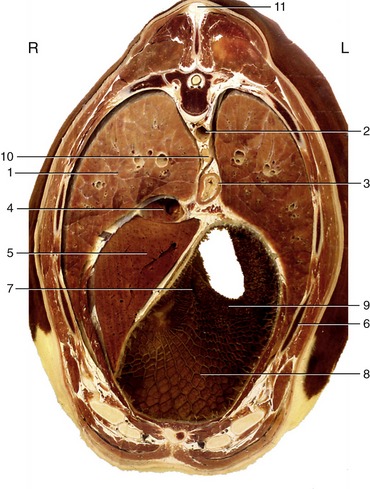

Figure 27–1 Horizontal section at the level of the shoulder and stifle joints. Note the relative volumes of the thoracic and abdominal cavities.

Figure 27–2 Left (A) and right (B) projections of the bovine heart and lungs on the thoracic wall. The basal border of the lung and the line of pleural reflection are also shown. 1, Cranial extent of heart; 2, caudal extent of heart; 3, basal border of lung; 4, line of pleural reflection; 5, caudal border of lung percussion area, shown on right side.

The thoracic wall of cattle, unlike that of sheep or goats, is mainly remarkable for the great breadth of the ribs, especially toward their lower ends, and the consequent narrowing of the intercostal spaces.

The ribs from the fifth to the thirteenth may generally be identified with ease, though possibly not palpated along their entire lengths. An increasing obliquity and a stronger bowing is revealed as the series is followed caudally, and there is an increasingly forward slope of their cartilages. The cartilages of the last five (asternal) ribs combine to form the costal arch that defines the cranial limit of the flank; those of the remaining (sternal) ribs join the sternum directly. The cranial part of the chest wall is rigid and contributes little to the respiratory movements; the wider, more caudal part makes a significantly larger contribution, but it is the activity of the diaphragm that predominates. Despite this, cattle survive diaphragmatic paralysis; however, they suffer greater distress than is usual in smaller species.

Surgical access to the thoracic cavity, though rarely indicated in cattle, is hampered by the narrowness of the intercostal spaces and may require resection of one or more ribs. The intercostal vessels follow both margins in the ventral parts of the spaces, which is a point relevant to pleurocentesis, which is best performed by puncture of the sixth or seventh space directly above the level of the costochondral joints.

THE PLEURA AND THE LUNGS

The lungs are very unequal in that the right one is the larger by a ratio of 3 : 2. The asymmetry affects the disposition of the pleural sacs; the most obvious consequence is the deviation of both the cranial and the caudal mediastinum far to the left. The cranial mediastinum actually attaches to the left wall of the thorax, while the caudal part meets the diaphragm in a sagittal plane that, when projected into the abdomen, bisects the reticulum, which exposes the two pleural sacs to almost equal chance of involvement when foreign bodies penetrate the thorax from that organ (p. 687). The apex of the right sac, which contains the tip of the cranial lobe of the lung, projects a few centimeters in front of the first rib, exposing it to risk of injury in penetrating wounds that are apparently confined to the base of the neck. The caudal reflection of the costal pleura onto the diaphragm is more important. It follows a cranially concave line that ascends steeply in its caudal part, tracing a course that passes through the eighth costochondral junction and the middle of the eleventh rib before reaching the twelfth rib just below the edge of the iliocostalis (see Figure 27–2). Behind this line the diaphragm is directly attached to the thoracic wall, and the abdomen may be approached without risk of injury to the pleural sac. A space in front of this line, the costodiaphragmatic recess, is never fully exploited by the lung. Its extent may be considerably exaggerated after death, when the lung is collapsed.

Apart from their asymmetry, the lungs of cattle are distinguished by their pronounced lobation and very evident lobulation.

The left lung possesses cranial and caudal lobes (see Figure 27–2), and the former is divided into two parts: one extends forward toward the apex of the pleural sac, and the other descends ventrally over the pericardium. The notch between the two extends from the third intercostal space to the fifth rib and defines the area in which the heart is in direct contact with the thoracic wall (Figure 27–3). The basal border changes position with the phase of respiration; as a compromise between the inspiratory and expiratory positions, it may be described as following an almost straight line from the sixth costochondral joint to the upper part of the eleventh rib. The thin marginal strip of lung does not provide useful clinical information, and the major area for percussion and auscultation is reduced to the surprisingly small triangle bounded by the triceps, the edge of the muscles of the back, and as hypotenuse, the line joining the point of the elbow to the upper part of the eleventh rib. A second (prescapular) area, extending a few centimeters in front of the ventral half of the cranial border of the scapula, is of minimal clinical significance.

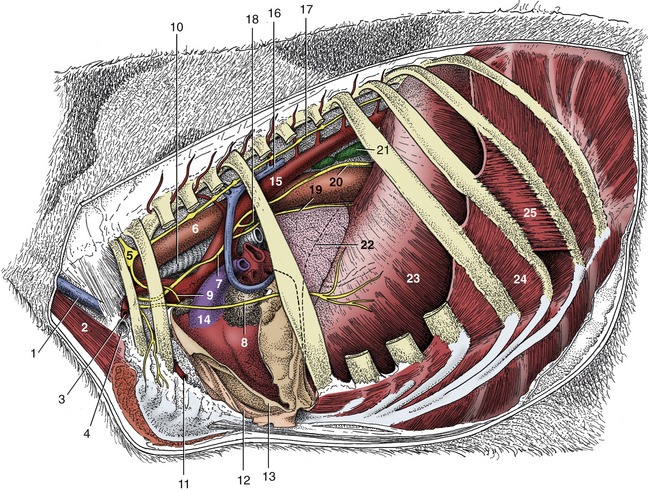

Figure 27–3 Left lateral view of the bovine thoracic cavity. The left lung and part of the mediastinal pleura have been removed. 1, External jugular vein; 2, sternocephalicus; 3, axillary artery; 4, axillary vein; 5, cervicothoracic ganglion; 6, esophagus; 7, vagus; 8, phrenic nerve; 9, one of the cardiac nerves; 10, trachea; 11, internal thoracic artery; 12, mediastinal pleura; 13, pericardium, reflected; 14, pulmonary trunk; 15, aorta; 16, left azygous vein; 17, sympathetic chain; 18, recurrent laryngeal nerve; 19, ventral vagal trunk; 20, dorsal vagal trunk; 21, caudal mediastinal lymph nodes; 22, cranial extent of diaphragm; 23, diaphragm; 24, internal intercostal muscle; 25, external intercostal muscle.

The right lung possesses four lobes—cranial, middle, caudal, and accessory (Figure 27–4). The cranial lobe is independently ventilated by a bronchus detached from the trachea shortly before the bifurcation. The cardiac notch, smaller than that on the left side, is restricted to the lower parts of the third and fourth spaces and is wholly under cover of the arm. The major area for clinical examination is a little larger on this side because it is free from the pressure exerted on the diaphragm by the rumen. Percussion toward the basal border is also more accurately performed as there is a sharp transition from the hollow lung sound to the duller note over the liver.

Figure 27–4 Lobation and bronchial tree of the bovine lungs, schematic dorsal view. 1, Trachea; 2, tracheal bronchus; 3, right principal bronchus; 4, 4′, divided right cranial lobe; 5, middle lobe; 6, right caudal lobe; 7, 7′, divided left cranial lobe; 8, left caudal lobe; 9, cranial tracheobronchial lymph node; 10, tracheobronchial lymph nodes; 11, pulmonary lymph nodes; 12, outline of accessory lobe of right lung.

Thick connective tissue septa divide the lung substance and mark the surface where they impinge on the pulmonary pleura (see Figure 4–27). These septa, which may help to localize infection, are even more prominent in certain diseases in which they become edematous.

The capacity for respiratory exchange is limited by a relatively low total alveolar surface area and a lesser capillary density when compared with that of other species. A large part is required for basal needs, and little is held in reserve.

The lungs of the small ruminants are similar in gross form but show a lesser and usually patchy lobulation.

Although the circulation through the lungs is maintained by pulmonary and bronchial arteries, all the blood returns through a single set of veins. Two lymphatic plexuses drain the lungs. One lies directly below the pleura and drains this and the adjoining connective tissue. The other follows the peribronchial tracts and may be interrupted by the interposition of peribronchial nodes (though these are never conspicuous and cannot always be found). Both sets enter the tracheobronchial nodes placed about the origins of the principal bronchi.

THE MEDIASTINUM AND ITS CONTENTS

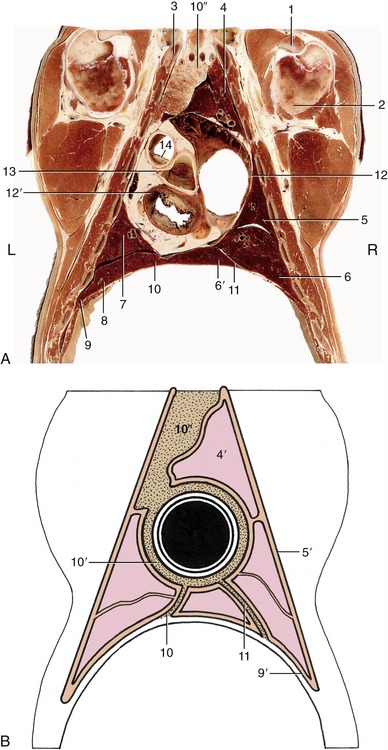

The thick dorsal part of the cranial mediastinum contains the esophagus and trachea, the vessels passing to and from the neck and forelimbs, an assembly of lymph nodes, the thoracic duct, and various nerves. In older animals the ventral part is thin, containing only the internal thoracic vessels and a vestige of the thymus. The difference in thickness is less striking in younger animals, in which the thymus has yet to regress (Figure 27–5).

Figure 27–5 Dorsal section of the bovine thorax directly ventral to the shoulder joint. A, Actual. B, Schematized to show the asymmetry of the cranial and caudal parts of the mediastinum (stippled). 1, Biceps tendon; 2, humerus; 3, first rib; 4, cranial lobe of right lung; 4′, pulmonary pleura; 5, middle lobe of right lung; 5′, costal pleura; 6, 6′, caudal and accessory lobes of right lung; 7, caudal part of cranial lobe of left lung; 8, caudal lobe of left lung; 9, diaphragm; 9′, diaphragmatic pleura; 10, 10′, 10″, caudal, middle, and cranial mediastinum, the last occupied by the thymus; 11, plica venae cavae; 12, 12′, right and left atrioventricular valves; 13, left coronary artery arising from aortic valve; 14, pulmonary valve.

The middle mediastinum is occupied by the heart (within the pericardium) ventrally; dorsally it includes the esophagus, the termination of the trachea, the aortic arch, pulmonary vessels, left azygous vein, various lymph nodes, and the vagal trunks (Figure 27–6). It is thus of very irregular thickness, being reduced in places to apposed pleural sheets. Ventral to the heart, it widens to contain the pericardiacosternal ligament.

Figure 27–6 Transverse section of the bovine thorax at the level of the fourth thoracic vertebra. Note the asymmetry of the lungs. 1, 2, Cranial lobes of right and left lungs; 3, scapula; 4, fourth thoracic vertebra; 5, third rib; 6, sternum; 7, olecranon; 8, long head of triceps; 9, pulmonary valve; 10, aortic arch; 11, right atrioventricular valve; 12, trachea; 13, esophagus.

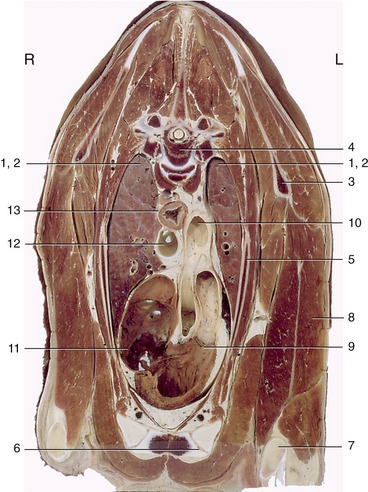

The caudal mediastinum is generally thin. The dorsal part contains the esophagus, aorta, vagus trunks, and caudal mediastinal nodes (Figure 27–7). The septum is very short and level with the base of the heart but, below this, lengthens where it deviates to the left (see Figure 27–5).

Figure 27–7 Transverse section of the bovine trunk at the level of the eighth thoracic vertebra. Note the cover to abdominal viscera provided by the ribs. 1, Caudal lobe of right lung; 2, aorta; 3, esophagus; 4, caudal vena cava; 5, liver; 6, seventh rib; 7, reticular groove; 8, reticulum; 9, ruminoreticular fold; 10, caudal mediastinal lymph node; 11, supraspinous ligament.

THE HEART

The heart is placed asymmetrically, 60% or more being to the left of the midline, and extends from the second intercostal space (or following rib) to the fifth space. It thus lies mainly under cover of the limbs in an animal standing square. The base lies in the plane of the last costochondral joint and the apex opposite the sixth cartilage, a few centimeters above the sternum; its long axis inclines somewhat caudally and to the left. Direct contact with the thoracic walls is restricted to the areas described with the lungs. The upright caudal border is related to the diaphragm and, through this, to the reticulum and liver; the sloping cranial border is related to the thymus in the young. The relations of the base include the trachea and principal bronchi, the pulmonary vessels, and lymph nodes (see Figure 27–5).

The bovine heart is constructed according to the general mammalian plan and exhibits no distinctive structural features of importance. The right atrium receives a left azygous vein, by way of the coronary sinus. It occasionally retains communication with the left atrium through an open foramen ovale; this is usually only probe patent and without significance. Two ossicles are found in the connective tissue related to the cusps of the aortic valve; they are not unique to cattle, as often supposed, but do appear to develop precociously in this species. The left coronary artery is dominant, the right one restricted to a circumflex course. It is worth mentioning that the isthmus of the aorta (the stretch between the origin of the brachiocephalic trunk and the junction with the ductus arteriosus) is greatly constricted in the newborn calf, which is an appearance that may falsely suggest the aorta arising from the right ventricle. The usual proportions are exhibited by calves that survive birth by even a few days.

The projections of the heart valves on the thoracic wall, or more accurately the puncta maxima, are obviously of much greater significance. The pulmonary and aortic valves may be regarded as being placed under the third rib and following space and the fourth rib, respectively; they are about 10 cm above the costochondral junctions, although the slope of the heart raises the aortic valve a little above and lowers the pulmonary valve a little below the suggested level. The left atrioventricular valve lies under the fourth space and fifth rib, and the right one lies under the fourth rib and space; each is at a slightly more ventral level than the associated arterial valve. It is of course only the right atrioventricular valve sound that is sought on the right side (see Figure 27–5).

Pericardiocentesis is most safety performed in the fifth intercostal space of the left side, directly dorsal to the costochondral joints.

THE ESOPHAGUS, TRACHEA, THYMUS, AND VAGUS NERVES

The esophagus and trachea enter the thorax surrounded by a loose fascia that continues the connective tissue of the neck and provides a pathway for the spread of fluids and infection that is most relevant in connection with leaking wounds of the esophagus. At this level the esophagus lies dorsolateral to the trachea on the left side but soon obtains a median position. Its relations include the cranial mediastinal lymph nodes and the vagus and sympathetic nerves when still close to the thoracic entrance, the aorta, thoracic duct, azygous vein, and the tracheobronchial and middle mediastinal nodes more caudally. In its final thoracic stretch, it has the important relations of the vagal trunks and the caudal mediastinal nodes (see p. 676).

Postmortem, the esophagus is seen relaxed, providing no evidence of the prediaphragmatic sphincter that is sometimes alleged to exist. The part embraced by the diaphragm may be found constricted, although palpation of the hiatus in life does not support the view that the diaphragm exerts a firm grip.

The trachea, deep and compressed from side to side, first lies dorsal to the veins combining to form the cranial vena cava; it continues this relationship to its bifurcation above the right atrium, shortly after detaching the bronchus that serves the right cranial lobe. Its relations at different levels include the principal nerves within the thorax, the aorta and thoracic duct, and the tracheobronchial nodes.

The thymus has previously been encountered in the neck (p. 660 and Figure 25–24). The thoracic part fills the ventral part of the cranial mediastinum, extending at its apogee over the cranial surface of the pericardium and reaching the origin of the pulmonary trunk and the aortic arch. Involution is rarely complete, and some vestige, consisting mainly of fat and fibrous tissue, persists even in aged animals.

The sympathetic and phrenic nerves are unremarkable. The vagus nerves exhibit no special features before their division into dorsal and ventral branches that unite with their partners of the other side to form the trunks that follow the borders of the esophagus. A connection over the left face of the esophagus suggests a further rearrangement of fibers preparatory to entering the abdomen, which may be relevant to the inconsistent effects of nerve sections on gastric function. The connection sometimes suggests reinforcement of the ventral trunk at the expense of the dorsal one, and sometimes the reverse. The relationship to the caudal mediastinal lymph node(s) is of importance (see p. 676).

THE LYMPHATIC STRUCTURES WITHIN THE THORAX

The lymphatic drainage of the thorax is complicated and variable. Not every node is present in every animal, and some may be placed so that it is difficult to assign them to a particular group. A series of small intercostal nodes is present directly below the pleura in certain spaces, and these are supplemented by a scattering of nodes along the aorta (Figure 27–8). Both sets drain lymph from structures about the vertebral column and within the dorsal mediastinum. Most of their outflow is directed toward the cranial mediastinal nodes.

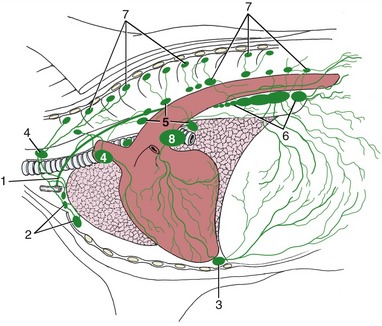

Figure 27–8 Lymph drainage of the bovine thoracic wall and mediastinum. 1, Thoracic duct; 2, cranial sternal lymph nodes; 3, caudal sternal lymph node; 4, cranial mediastinal lymph nodes; 5, middle mediastinal lymph nodes; 6, caudal mediastinal lymph nodes; 7, intercostal and thoracic aortic lymph nodes; 8, tracheobronchial node.

Caudal sternal nodes are concealed below the transverse thoracic muscle on the thoracic floor, while a larger cranial sternal node lies in front of this. These nodes drain the ventral parts of the cranial abdominal and thoracic floors and also receive lymph from overlying muscles of the forelimbs. They direct their outflow to the cranial mediastinal group.

Other important nodes occupy more central positions. A cranial mediastinal group, scattered among various structures near the entrance to the thorax, drains the adjacent part of the mediastinum as well as the dorsal and ventral groups recently mentioned. The outflow goes to the thoracic duct or to one of the tracheal ducts. Middle mediastinal nodes lying to the right of the aortic arch receive lymph from adjacent structures and from a portion of the tracheobronchial nodes. The efferent flow passes in part directly to the thoracic duct, in part to the other mediastinal groups. The tracheobronchial nodes placed directly on the trachea and principal bronchi receive lymph from the lungs and distribute this among the various mediastinal nodes.

The caudal mediastinal group comprises only one or two nodes. The larger and possibly solitary node may attain a length of 20 cm; it is flexed to fit over the diaphragm, dorsal to the hiatus, and over the terminal part of the esophagus. Pathological conditions in this node may cause it to press on the esophagus, which would impede the eructation of ruminal gas, or interfere with vagal control of gastric function.

The thoracic duct, into which most of the lymph eventually flows, inclines ventrally over the left face of the trachea to end by opening into the cranial vena cava or one of its tributaries of the left side. The duct is often duplicated for all or part of its course.