CHAPTER 59 Postpartum and Mammary Disorders

POSTPARTUM DISORDERS

METRITIS

Metritis is an acute postpartum bacterial infection of the uterus. It also may occur after abortion, dystocia, retention of placental or fetal tissues, obstetric procedures, or normal parturition. Bacteria that ascend from the vagina are the cause. Affected animals are febrile and have a fetid, septic uterine discharge. Dehydration, septicemia, endotoxemia, shock, or a combination of these can occur. One of the earliest signs of maternal illness is unthrifty, crying neonates that are being neglected by the dam. Metritis and mastitis are the two most common causes of fever and neonatal neglect in the postpartum bitch.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based primarily on the historical and physical findings. Diagnostic imaging should be done to evaluate the uterine contents (e.g., fetal remnants) and assess the integrity of the uterus. Bacterial culture and sensitivity testing of the uterine discharge should be performed. The overall health of the dam can be further assessed with a complete blood count (CBC) and biochemical panel if indicated. The septic nature of the discharge can be confirmed by cytologic examination. The uterine source of the exudate can be confirmed with endoscopic studies, but this is usually not necessary.

Treatment

For the sake of neonatal survival, metritis should be treated promptly and aggressively to minimize the hospital stay. Infected uterine contents can be removed surgically by ovariohysterectomy or medically with the administration of ecbolic agents. The decision to manage metritis medically or surgically is determined by the health of the bitch or queen, the integrity of the uterus, and the owner’s desire for the animal to be able to reproduce in the future. Regardless of the approach taken, intravenous (IV) fluid therapy should be aggressive to correct existing deficits, maintain tissue perfusion, and provide for the additional demands of lactation, which are substantial. The antibiotic should be chosen on the basis of the results of a culture of the uterine exudate obtained from the anterior vagina. It is assumed that the antibiotic will reach the neonates through the milk; therefore the potential for deleterious effects on the neonates should be considered (Box 59-1). When future reproductive function is not important, in cases of potential uterine rupture, and in situations in which the dam is critically ill, ovariohysterectomy should be performed.

Medical, rather than surgical, management of metritis is appropriate for animals that are in stable condition. Drugs that cause myometrial contractions, such as the prostaglandin cloprostenol, are used to promote the evacuation of infected uterine contents, as described for the treatment of pyometra in Chapter 57. The luteolytic aspects of the drugs are not needed for the treatment of postpartum metritis because the corpora lutea (CLs) are no longer present, but they may be helpful in cases of postabortion metritis in which serum progesterone may still be high. Treatment should continue until the uterus is empty, as determined by ultrasound. This usually takes several days. Aglepristone (Alizine®, Virbac), which blocks the progesterone receptor, has also been successfully used to treat metritis in bitches. The dose of aglepristone is 10 mg/kg, administered subcutaneously once daily on days 1, 2, and 8.

PUERPERAL HYPOCALCEMIA (PUERPERAL TETANY, ECLAMPSIA)

Puerperal tetany is an acute, life-threatening hypocalcemia that occurs in the postpartum period. Clinical signs are a direct result of hypocalcemia and include muscle fasciculation and tetany but not true seizures. The cause of the hypocalcemia is usually undetermined, but it could result from such problems as maternal calcium loss to the fetal skeletons and to the milk, poor absorption of dietary calcium, and parathyroid gland atrophy caused by improper diet or dietary supplements. Clinical signs of puerperal hypocalcemia typically develop during peak lactation (i.e., 1 to 3 weeks postpartum) in small bitches that are nursing large litters. The dam is otherwise healthy, and the neonates are thriving. Puerperal hypocalcemia also can occur in cats, in any breed of dog, with any size litter, and at any time during lactation. Rarely, hypocalcemia occurs during late gestation in bitches and queens and may contribute to dystocia.

Clinical Features

The clinical signs are caused by hypocalcemia and include panting, trembling, muscle fasciculation, weakness, and ataxia. These early clinical signs quickly progress (e.g., within hours) to tetany with tonic-clonic spasms and opisthotonos. Heart rate, respiratory rate, and rectal temperature are increased, especially during tetany. Clinical signs are rapidly progressive and may be fatal if the animal goes untreated.

Diagnosis

Puerperal hypocalcemia is diagnosed on the basis of the typical clinical signs in a heavily lactating female. It can be confirmed by measuring the serum concentrations of calcium, which typically are below the reference range. Because the clinical signs in postpartum bitches are so suggestive, treatment is usually initiated before, or without, laboratory confirmation. Laboratory confirmation would be necessary in a prepartum animal. Although severe hypoglycemia could cause similar clinical signs, it is a rare postpartum disorder in the bitch or queen.

Treatment

Treatment consists of the slow IV administration of a 10% solution of calcium gluconate, to effect. The total dose is usually 3 to 20 ml, depending on the size of the bitch or queen. Because calcium is cardiotoxic, the animal’s heart must be closely monitored for the development of dysrhythmias and bradycardia during treatment. Calcium administration must be stopped immediately if any cardiac abnormalities are detected. If additional calcium is still needed, it should be administered as soon as the cardiac rhythm has normalized, but the rate of administration should be much slower. The response to treatment is dramatic, and clinical signs resolve during IV calcium administration.

Puppies or kittens should then not be allowed to nurse for 12 to 24 hours. Oral calcium (gluconate, carbonate, or lactate), 1 to 3 g daily, should be administered for the duration of lactation. The dam’s diet should also be adjusted to ad libitum feeding or at least feeding three times a day. The diet should be high-quality commercial food that is labeled as nutritionally complete, balanced, and appropriate for lactation. Some veterinarians also recommend that dams be given vitamin D supplementation, but this must be done with caution because hypercalcemia can occur in response to overzealous vitamin D supplementation. Usually, a balanced diet with additional oral calcium suffices to prevent hypocalcemia. If hypocalcemia recurs, the puppies should be weaned.

Prevention

Several steps can be taken to prevent puerperal hypocalcemia in the bitch and queen. First, a high-quality, nutritionally balanced and complete diet should be fed to the bitch or queen during pregnancy and lactation. Second, oral calcium supplementation during gestation is contraindicated because it may worsen, rather than prevent, postpartum hypocalcemia. Finally, the bitch or queen should have access to food and water ad libitum during lactation. If necessary, the dam can be physically separated from the neonates for 30 to 60 minutes several times a day to encourage her to eat. Supplemental bottle-feeding of the litter with milk replacer early in lactation and with solid food after 3 to 4 weeks of age may be helpful, especially for large litters.

SUBINVOLUTION OF PLACENTAL SITES

In the bitch normal postpartum involution of the uterus occurs over 12 weeks. The placental sites and the entire endometrium slough. By the ninth week the uterine horns are uniformly contracted, and the surface sloughing is complete. Replacement of the endometrial lining continues until the twelfth postpartum week, at which time involution is complete. The sloughed material makes up the normal postpartum vulvar discharge known as lochia. Immediately after whelping, lochia contains large amounts of the placental blood heme pigment called uteroverdin. This makes the lochia dark green for the first few hours (<12 hours). Thereafter the lochia is reddish or red-brown and contains cellular debris and mucus. The volume of lochia diminishes quickly, and within a few weeks it is an intermittent (several times a day) spotting of reddish or red-brown mucoid material.

Subinvolution of placental sites (SIPS) results in persistent postpartum dripping of sangineous discharge for 12 or more weeks. SIPS is most common in primiparous bitches younger than 3 years of age, but it can occur in older multiparous animals as well. It has not been reported in cats. The cause is unknown.

Diagnosis

Affected bitches are healthy and physically normal, except for a small amount of bloody vulvar discharge. The blood loss from SIPS is not severe. If the clinician is concerned, the CBC can be evaluated, keeping in mind the normal decline in the packed cell volume (PCV) that occurs during pregnancy. Vaginal cytology (see Chapter 56) can be used to differentiate the bleeding associated with SIPS from lochia and from the discharge associated with metritis. Cytologically, evidence of hemorrhage is found. Decidua-like multinucleated giant cells may also be seen. Ultrasound can be used to assess the degree of uterine involution. The diagnosis of SIPS usually is based on the historical, physical, and cytologic findings alone. It can be confirmed by histopathologic examination of the placental sites, but this is rarely necessary. Normally involuted placental sites and SIPS can be found in the same uterus.

Bitches with SIPS rarely require treatment. Recovery is spontaneous, and subsequent fertility is not affected. Ovariohysterectomy is curative. The administration of ergonovine maleate, oxytocin, or prostaglandin will cause uterine contraction and may diminish bleeding, but there is little published evidence that this hastens recovery from SIPS. Progestin therapy has also been suggested, but its undesirable effects on the endometrium outweigh any potential benefit in this situation. If anemia is severe enough to require treatment, a diagnosis other than SIPS should be considered.

DISORDERS OF THE MAMMARY GLANDS

MASTITIS

Mastitis is a bacterial infection in one or more of the lactating mammary glands. It is a common postpartum disorder in bitches. It is rare in queens. Mastitis rarely occurs in bitches that are lactating because of false pregnancy. Whenever inflammation and/or abnormal secretions are present in nonlactating glands, mammary neoplasia should be strongly considered as the cause. The clinical signs of mastitis are variable in severity but include fever; anorexia; dehydration; and warm, firm, swollen, painful glands. Crying, unthrifty puppies may be what the owner notices first because bitches that are ill with mastitis may neglect them. In severe cases abscesses or gangrene of the glands can develop. Mastitis is the most common cause of postpartum fever. The diagnosis is made on the basis of these physical findings in a lactating female and on the septic appearance of the mammary secretions. Escherichia coli, staphylococci, and β-hemolytic streptococci are the organisms most frequently isolated.

The treatment of mastitis includes antibiotics, fluid therapy, and supportive care. It should be aggressive to ensure that the bitch can resume her maternal duties as soon as possible. Adequate water and caloric intake is crucial to ensure continued milk production. During lactation food and water needs are often double what they were during gestation. The additional fluid needs to support lactation must be taken into account when planning fluid therapy. Warm compresses applied to affected glands several times a day can reduce swelling and pain, and this should be included in the treatment of mastitis.

There are several factors to consider in the choice of antibiotics, including the susceptibility of the infecting organisms, the ability of the antibiotic to achieve high concentrations in milk, and the effects of the drug on the nursing neonate (see Box 59-1). Amoxicillin and cephalosporins can be used if the results of bacterial culture are not known because they are likely to achieve reasonable concentrations in the infected gland, they are likely to be effective against the most common organisms, and they are reasonably safe for neonates. Mammary abscesses and gangrene should be treated surgically.

It is recommended that pups continue nursing as long as the dam is willing and able to provide adequate nutrition. Monitoring the weight gain of the puppies, which should be about 10% per day, helps the clinican assess whether the puppies’ needs are being met. The pups should also be watched closely for other signs of illness. If present, supplemental feeding or hand-rearing of the puppies should be considered.

GALACTOSTASIS

Galactostasis is the accumulation and stasis of milk within the mammary gland. This results in warm, firm, swollen, painful glands. Unlike mastitis, in galactostasis the mammary secretions are not infected and the dam is not ill. Milk is simply being produced faster than it can comfortably be stored. Galactostasis usually occurs at the time of weaning and occasionally at the time of peak lactation, when production transiently exceeds the needs of the neonates. Galactostasis may also occur with false pregnancy (see Chapter 58).

Treatment is not indicated for the transient galactostasis that occasionally occurs during the first 1 to 3 weeks of lac tation. If treatment is necessary for galactostasis that occurs at weaning, it is directed toward reducing milk production and relieving discomfort. Milk production diminishes as food and water intake is restricted. Therefore reducing the caloric intake to amounts appropriate to maintain ideal body weight and normal hydration during anestrus (i.e., neither pregnant nor lactating) is helpful in treating, as well as preventing, the galactostasis that occurs at weaning. Gradual, rather than abrupt, weaning is also helpful. Because massaging or expressing the mammary glands may stimulate prolactin release and promote continued lactation, these techniques are not recommended. Warm compresses may help relieve swelling and discomfort.

AGALACTIA

Agalactia is the absence of milk production or secretion. Normal milk production and secretion are dependent on many factors, including genetics, nutrition, psychological factors, and anatomic differences. Prolactin stimulates milk production. Oxytocin stimulates milk letdown. Primary agalactia refers to a situation in which the gland is incapable of producing milk or the ducts are incapable of flow. More commonly, the gland and ducts are normal but other factors have diminished the capacity for production or inhibited milk letdown. Animals that are in poor body condition may have difficulty establishing and maintaining lactation. Caloric and water needs during lactation are as much as double those needed during gestation. To ensure that the needs of both gestation and lactation are met, a high-energy diet, appropriate for reproduction and lactation, should be fed from the time of breeding onward. Unlike multiparous animals that may have colostrum that is easily expressed during the last week of gestation, primiparous animals may not produce colostrum at this time; however, colostrum is almost always present within 24 hours of parturition.

Anxiety will inhibit milk letdown. The nursing dam and her litter should be in a quiet location, with limited visitors, especially for the first several days. If necessary, sedation may be considered. Phenothiazines may increase prolactin secretion, which would be beneficial. Oxytocin, 0.5 to 2.0 U administered subcutaneously q2h, has also been suggested to promote milk letdown. It is available for this purpose in people in the form of a nasal spray. Puppies or kittens are returned to nurse 30 minutes after oxytocin is administered. Metoclopramide stimulates prolactin secretion and has been successfully used to enhance lactation. The dose is 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg (administered orally or subcutaneously) q6-8h until lactation is adequate. The oral dose may be increased to 0.5 mg/kg q8h if needed. Treatment is usually needed for only a day or two. Meanwhile, nutritional and psychological factors must also be corrected.

GALACTORRHEA

Galactorrhea refers to lactation that is not associated with pregnancy and parturition. It is the most common clinical manifestation of false pregnancy in the bitch. Galactorrhea of false pregnancy occurs at the end of diestrus, after the withdrawal of exogenous progestins, or after oophorectomy performed during diestrus. This galactorrhea is self-limiting and usually does not require treatment. See Chapter 58 for details of the condition.

FELINE MAMMARY HYPERPLASIA AND HYPERTROPHY

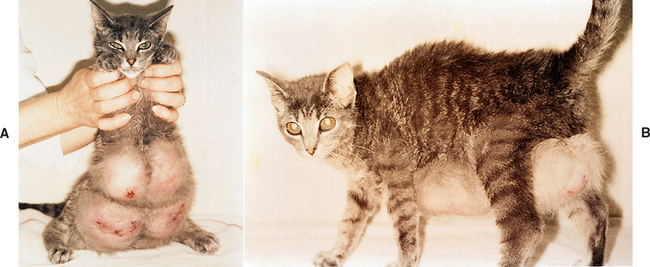

Feline mammary hyperplasia (fibroepithelial hyperplasia, fibroadenoma, fibroadenomatosis) is characterized by the rapid, abnormal growth of mammary tissue. Hyperplasia of both epithelial and mesenchymal tissues is evident microscopically. It is most common in young, cycling queens that may or may not be pregnant (Fig. 59-1). It has also been observed in neutered male and neutered female cats that are receiving exogenous progestins. There is a strong temporal relationship between the onset of mammary hyperplasia and progesterone stimulation. Feline mammary hyperplasia is a benign condition, but its abnormal growth may mimic those of mammary neoplasia. Histologic evaluation of a biopsy specimen can be done if there is any doubt.

Treatment consists of removing the source of the progesterone. Although successful pregnancy and nursing of kittens were reported in one queen with mammary hyperplasia, ovariohysterectomy is usually recommended, irrespective of the pregnancy status. The surgery is often performed through a flank incision rather than through the usual midline approach, because of the massive size of the glands. The hyperplastic tissue resolves over several weeks following oophorectomy. The prognosis is excellent. In the unlikely event that there is no response to withdrawal of progestins or ovariohysterectomy, the progesterone receptor blocker aglepristone (Alizine®, Virbac), 20 mg/kg administered subcutaneously on one day or 10 mg/kg on two consecutive days once weekly, resolves the condition in 1 to 4 weeks. The only side effect is irritation at the injection site; however, aglepristone will cause abortion if the queen is pregnant. Mastectomy may be indicated if the abnormal mammary tissue has become necrotic.

MAMMARY DUCT ECTASIA

Mammary duct ectasia is a benign, sometimes painful condition in which the mammary collecting ducts are dilated by inspissated secretions. It occurs in neutered and intact bitches of any age, but the mean age at the time of diagnosis is 6 years. The clinical signs resemble those of mammary neoplasia. The cystic nature of the condition can often be appreciated on palpation. The inspissated material is yellow or bluish in color and is sometimes visible beneath the skin. Surgical excision is curative. The mass should be submitted for histopathologic evaluation because mammary neoplasia is the other likely differential diagnosis.

MAMMARY NEOPLASIA

Etiology

Mammary neoplasms account for about half of all tumors in bitches. Although they are less prevalent in queens, mammary neoplasms are still the third most common tumor type in cats. They primarily affect older animals, with a mean age of about 10 years. Most affected animals are intact females or females that have undergone oophorectomy after 1 or 2 years of age. Mammary tumors are rare in males and in young animals of either sex.

Early ovariohysterectomy is strongly protective against the development of mammary tumors. Bitches neutered before their first estrous cycle are at no greater risk for mammary tumors than are males. After 2.5 years of age or after the second estrous cycle, ovariohysterectomy is apparently no longer protective in bitches. Cats neutered before 1 year of age also have a significantly (86%) decreased risk of developing mammary carcinoma. The progestins used to suppress estrus promote hyperplastic and neoplastic changes in the feline and canine mammary glands. Benign mammary tumors are found in more than 70% of bitches receiving long-term progestin treatment. About half of mammary tumors in bitches are benign, whereas feline mammary tumors are almost always malignant.

Clinical Features

Mammary tumors are usually discrete, firm, and nodular. They may be found anywhere along the mammary chain. The size is extremely variable, ranging from a few millimeters to many centimeters in diameter. Multiple glands are involved more than half of the time. The tumors may adhere to the overlying skin but usually are not attached to the underlying body wall. Malignant tumors are more likely than benign tumors to be attached to the body wall and covered by ulcerated skin. About 25% of feline mammary tumors are covered by ulcerated skin. Abnormal secretions can often be expressed from the nipples of affected glands. Inflammatory carcinoma of a mammary gland may have a physical appearance similar to that of mastitis. However, inflammatory carcinoma is most likely to occur in geriatric animals, and there is no association with lactation. The regional lymph nodes (axillary or inguinal) may be enlarged if metastasis has occurred. The remainder of the physical examination findings are often unremarkable. There may be evidence of tumor cachexia in animals with advanced neoplasia.

Diagnosis

Mammary neoplasia is the most likely cause of any kind of nodule in the mammary gland of an older female. Excisional biopsy is the method of choice to confirm the diagnosis. Cytologic examination of specimens obtained by fine-needle aspiration often yields equivocal results. Before excisional biopsy is performed, radiographs of the thorax should be evaluated for evidence of pulmonary metastasis. If evidence of pulmonary metastasis is found, a grave prognosis is justified, even in the absence of histologic confirmation of mammary neoplasia. Malignant mammary tumors frequently metastasize to the regional lymph nodes and to the lungs. Less commonly, hepatic metastasis occurs. Metastasis to distant sites can also occur, but this rarely happens in the absence of local lymph node or pulmonary involvement. Diagnostic imaging and careful palpation are used to evaluate the tumor burden. The animal’s overall health is assessed with a CBC, biochemical panel, and urinalysis.

Prognosis

Approximately half of the mammary tumors in bitches are benign. Some of these benign tumors show evidence of cellular atypia within the parenchyma and are considered precancerous. Precancerous changes in bitches are associated with a ninefold increase in the risk of mammary adenocarcinoma developing at a later date. Animals with nodules of normal cellular characteristics are at no greater risk than animals with no previous mammary nodules. In contrast, benign mammary tumors are rare in cats. More than 80% of feline mammary tumors are classified as adenocarcinomas.

Adenocarcinoma is the most common malignant mammary tumor in bitches and queens. If the neoplastic cells are confined to the duct epithelium (carcinoma in situ), the prognosis after surgery is good. The prognosis is somewhat worse if neoplastic cells are found beyond the boundary of the duct system but not in blood or lymphatic vessels. The prognosis is worse if neoplastic cells are found in blood or lymphatic vessels. If neoplastic cells are found in the regional lymph nodes, the disease-free interval after surgery is significantly shortened. Nuclear differentiation affects the recurrence rates, even within the same stage of invasion. The recurrence rate 2 years after mastectomy in bitches with poorly differentiated (i.e., anaplastic) tumors is 90% versus rates of 68% and 24% in animals with moderately differentiated and well-differentiated tumors, respectively.

In queens mammary tumors are almost exclusively carcinomas. In bitches other malignant tumors of the mammary gland, such as inflammatory carcinoma, sarcomas, and carcinosarcomas, are occasionally found, but they are much less common than are adenocarcinomas. Inflammatory carcinoma is a fulminant malignant disease associated with a grave prognosis in bitches and queens.

Treatment

The treatment of mammary neoplasia is surgical excision of all abnormal tissue. Controversy persists as to the preferred surgical technique: nodule excision, simple mastectomy, or radical mastectomy. If nodulectomy is chosen, apparently normal surrounding tissue should always be included and submitted for histopathologic evaluation for evidence of tumor invasion. If there is evidence of extension beyond the nodule, mastectomy should be performed. There is no difference in the survival times after simple versus radical mastectomy in bitches and queens; however, the disease-free interval may be longer in cats that have undergone radical mastectomies. Excised mammary tumors should always be submitted for histopathologic examination because the tumor type determines the prognosis. The prognosis for inflammatory carcinoma is grave.

Because the surgical excision of malignant mammary tumors is not curative, the effectiveness of adjunct therapies has been investigated. There is no doubt that estrogen and progesterone play a role in mammary neoplasia. Mammary tumors express estrogen receptors or progesterone recep-tors (or both), which explains why some mammary masses appear to be hormone sensitive and others do not. The effects on survival of endogenous and exogenous hormones continues to be of interest. To fully assess the therapeutic benefits of hormonal manipulation, the clinician must know the estrogen- and progesterone-receptor status of the tumors. In many veterinary studies that has not been the case.

Ovariohysterectomy performed at the time of mastectomy has no effect on 2-year survival rates in bitches. There also appear to be no differences in survival among bitches that undergo ovariohysterectomy before mastectomy, bitches that undergo ovariohysterectomy at the time of mastectomy, and bitches that undergo mastectomy alone, although data are conflicting. Tamoxifen competitively binds estrogen receptors with a combined antagonist-agonist effect. Its antiestrogenic effects are helpful in the treatment of mammary neoplasia in women. Tamoxifen has primarily estrogenic effects in dogs. In a study of the use of tamoxifen as adjunct therapy for canine mammary neoplasia, no beneficial antitumor effects were proved but 56% of the treated dogs showed adverse estrogenic effects. Although at present there is little published evidence of beneficial effects of chemotherapy as an adjunct to the surgical treatment of mam-mary tumors in bitches and queens, clinical investigations continue.

Drobatz K, et al. Eclampsia in dogs: 31 cases (1995–1998). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;217:216.

Görlinger S, et al. Treatment of fibroadenomatous hyperplasia in cats with aglepristone. J Vet Intern Med. 2002;16:710.

Johnston SD, et al, editors. Canine and feline theriogenology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

Linde-Forsberg C, et al. Abnormalities in pregnancy, parturition and the periparturient period. In Ettinger SJ, et al, editors: Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, ed 6, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005.

Miller M, et al. Mammary duct ectasia in dogs: 51 cases (1992–1999). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;218:1303.

Moe L. Population-based incidence of mammary tumours in some dog breeds. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2001;57:439.

Overly B, et al. Association between ovariohysterectomy and feline mammary carcinoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19:560.

Pérez Alenza, et al. Inflammatory mammary carcinoma in dogs: 33 cases (1995–1999). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219:1110.

Philibert J, et al. Influence of host factors on survival in dogs with malignant mammary gland tumors. J Vet Intern Med. 2003;17:102.

Sorenmo K, et al. Effect of spaying and timing of spaying on survival of dogs with mammary carcinoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2000;14:266.

BOX 59-1

BOX 59-1